Abstract

There is debate about the use of wetlands as natural climate solutions due to their ability to act as a “double-edged sword” with respect to climate impacts by both sequestering CO2 while emitting CH4. Here, we used a process-based greenhouse gas (GHG) perturbation model to simulate wetland radiative forcing and temperature change associated with wetland state conversion over 500 years based on empirical carbon flux measurements, and CO2-equivalent (CO2-e.q.) metrics to assess the net flux of GHGs from wetlands on a comparable basis. Three CO2-e.q. metrics were used to describe the relative radiative impact of CO2 and CH4—the conventional global warming potential (GWP) that looks at pulse GHG emissions over a fixed timeframe, the sustained-flux GWP (SGWP) that looks at sustained GHG emissions over a fixed timeframe, and GWP* that explicitly accounts for changes in the radiative forcing of CH4 over time (initially more potent but then diminishing after about a decade)—against model-derived mean temperature profiles. GWP* most closely estimated the mean temperature profiles associated with net wetland GHG emissions. Using the GWP*, intact wetlands serve as net CO2-e.q. carbon sinks and deliver net cooling effects on the climate. Prioritizing the conservation of intact wetlands is a cost-effective approach with immediate climate benefits that align with the Paris Agreement and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change timeline of net-zero GHG emissions by 2050. Restoration of wetlands also has immediate climate benefits (reduced warming), but with the majority of climate benefits (cooling) occurring over longer timescales, making it an effective short and long-term natural climate solution with additional co-benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment report states that a reduction to net-zero global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050 is necessary to hold global average temperature rise to below a 2 °C increase above preindustrial levels1. To achieve net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, several countries (e.g., USA and Canada) have emphasized the potential of implementing natural climate solutions, which involves protecting, conserving, and restoring natural ecosystems to remove carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere2,3,4. The use of wetlands as natural climate solutions is gaining popularity given their ability to sequester atmospheric CO2 while simultaneously delivering multiple co-benefits beyond climate mitigation2,3,4,5.

Inland wetlands can be broadly categorized into peatlands [wetlands that are characterized by water at or near the surface and an accumulation of a thick layer of partially decomposed organic matter (>40 cm of surface organic matter)] and mineral soil wetlands [wetlands that have water at or near the surface and an accumulation of a thinner layer of non-peat accumulating organic soil (<40 cm of surface organic matter)]6,7. Mineral soil wetlands tend to accumulate less organic matter relative to peatlands due to their relatively high decomposition rates and smaller imbalances between production and decomposition6,8. Nevertheless, the waterlogged anaerobic conditions of mineral soil wetlands promote the long-term removal of CO2 by sequestering this greenhouse gas (GHG) into organic matter that accumulates in these productive systems6,9.

However, the same conditions that promote the long-term accumulation of carbon are also the conditions that result in wetlands being a considerable source of methane (CH4) globally10,11,12. CH4 is a more potent GHG, with a much higher radiative efficiency but shorter atmospheric lifetime (~12 years) as compared to CO2 (atmospheric lifetime range from 3.4 to 108 years)13,14. Therefore, despite the fact that CH4 fluxes in wetlands are typically considered orders of magnitude lower than CO2 exchanges, the cooling effect of carbon sequestration in intact wetlands can be offset by the warming effect associated with CH4 emissions15,16. Human-induced changes in mineral soil wetland states (e.g., wetland drainage and restoration) impose uncertainties in their GHG fluxes and therefore their potential to serve as natural climate solutions4,10.

To effectively use mineral soil wetlands (hereafter wetlands) in temperate North America to achieve mid-century climate targets, it is essential to understand how protecting, restoring, and draining wetlands affect CO2 and CH4 emissions. Restoring drained wetlands can inhibit soil carbon oxidation and effectively reduce CO2 emissions; however, this often comes at the cost of increased CH4 emissions10,12,17,18,19. Conversely, draining and converting wetlands to other land uses can result in a substantial release of CO2 to the atmosphere while reducing CH4 emissions18,20. Despite extensive research on how intact and restored wetlands can deliver a net cooling effect on climate at the timescale of centuries3,14,17, scientific debate continues on (1) whether the cooling effect of CO2 sequestration in intact wetlands can be offset by the warming effect of CH4 emissions, and (2) whether restored wetlands deliver short-term natural climate solutions for countries aiming to achieve mid-century net-zero emissions targets2,3,4.

To better understand the climate footprint of wetlands and their capacity as natural climate solutions for mid-century climate targets, the atmospheric lifetime of wetland GHGs (i.e., CO2 and CH4) and the relative potential of these GHGs to absorb infrared radiation in the atmosphere (i.e., radiative efficiency) need to be assessed on a comparable basis13,15,21,22,23. To facilitate this comparison, wetland GHG fluxes need to be normalized to CO2-equivalent (CO2-e.q.) measures15,24,25. The 100-year variant of the Global Warming Potential (GWP100) has been formally adopted in international climate policy (e.g., Paris Agreement) and is the standard CO2-e.q. metric for expressing emissions in the scientific literature and general media26. Despite being broadly used, GWP100 and any GWP variant have been criticized14,15,27,as they make the incorrect assumptions that wetland GHG emissions occur as a single pulse15 and that wetland carbon-based GHGs have the same climate impact mechanism over time thereby ignoring the differences in climate warming associated with long-lived climate pollutants (e.g., CO2) and short-lived climate pollutants (e.g., CH4)23,27. CO2 in the atmospheric reservoir persists for hundreds of years in the absence of active CO2 removal efforts (e.g., afforestation/reforestation and direct air capture etc.)24,28. As a result, ongoing CO2 emissions add cumulatively to the atmospheric stock, causing atmospheric temperatures to increase continuously over a span of hundreds of years23,24,27. Conversely, CH4 in the atmospheric reservoir persists for a much shorter time because of natural removal mechanisms (e.g., reaction of CH4 molecules with hydroxyl radicals)23,24,29. The shortcoming of commonly-used GWPs is that they overstate the cumulative effect of wetland CH4 emissions on total warming given that natural removal mechanisms of atmospheric CH4 are not captured, thereby resulting in misleading conclusions when assessing how wetland ecosystems may serve as natural climate solutions23,27.

Several CO2-e.q. metrics have been introduced that consider the effects of wetland GHG fluxes on radiative forcing over different timeframes. Neubauer and Megonigal15 developed two alternative CO2-e.q. metrics, known as the sustained-flux global warming potential (SGWP) and the sustained-flux global cooling potential (SGCP), accounting for GHG efflux and influx, respectively. SGWP and SGCP have been broadly adopted within the wetland research community and are frequently used to infer wetland climate impacts and the role of wetlands in climate mitigation strategies3,16,17,30. Recently, Allen et al.22,23 and Cain et al.27 introduced an alternative way of estimating CO2-e.q. (i.e., GWP*) by relating a change in CH4 emissions rate to a fixed quantity of CO2. GWP* has been found to reflect the impact of anthropogenic CH4 emissions more accurately on average global temperature as compared to the GWP and SGWP metrics24,27. Despite progress towards identifying a physically based CO2-e.q. approach to assessing wetland climate footprints on a comparable basis, debate continues on what is the most appropriate way for simple yet effective CO2-e.q. comparison of GHG emissions under different timeframes being considered24,27,30,31,32.

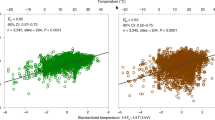

Here, we explore the potential of wetlands in temperate North America as natural climate solutions using different CO2-e.q. metrics (GWP, SGWP, GWP*). We focus on inland mineral soil wetlands, which make up most of the wetland area in temperate regions, where human settlements and associated wetland losses are greatest, and where restoration of wetlands holds great promise in terms of serving as an effective natural climate solution3,4,9. To test the various CO2-e.q. metrics for mid-century natural climate solutions targets we: (1) compiled yearly (snow-free season) GHG flux rates for inland mineral soil wetlands (Fig.1) (see Methods section for detailed description on the compiled dataset); (2) sorted these GHG flux rates into three scenarios (i.e., wetlands that remained intact, wetlands that were drained, and wetlands that were drained and then restored); and (3) used the GHG flux rates for each wetland state conversion scenario as input to a GHG perturbation model13 to simulate the changes in atmospheric concentration of wetland GHGs and the instantaneous radiative forcing, cumulative radiative forcing, and the impact on average temperature associated with changes in wetland GHG fluxes following a change in wetland state. Further, (4) we calculated the mean surface temperature switchover time (i.e., the length of time after which the warming effect due to CH4 emissions is overtaken by the cooling effect of CO2 sequestration) associated with the change in wetland state20,33. Finally, (5) we created cumulative CO2-e.q. carbon budget profiles over 500 years for each of the CO2-e.q. metrics (i.e., GWP, SGWP, GWP*), assessing the influence of the CO2-e.q. metrics on interpretation of wetlands as natural climate solutions.

a Geographic location of complied study. b Central tendency of the compiled CO2 flux data for intact wetland, drained wetland, and restored wetland [the vertical dash line distinguishes between a CO2 sink (left) vs. source (right)] and (c) compiled CH4 flux data for intact wetland, drained wetland, and restored wetland. CH4 flux data is separated into different categories (low and high) using K-means cluster analysis for intact wetland. There are no drained and restored wetlands in the high CH4 flux clusters. The median, interquartile range (IQR), and total number of observations (total n) are provided for each wetland state. Meanwhile, percentage of data falling within each K means CH4 flux category are provided.

Results

Wetland CO2 and CH4 fluxes

The CO2 fluxes ranged from −810 (±490 kg C-CO2 ha−1 yr−1) for intact wetlands, to −2420 (±1415 kg C-CO2 ha−1 yr−1) for restored wetlands, and to 4898 (±1223 kg C-CO2 ha−1 yr−1) for drained wetlands (Fig. 1). The CH4 fluxes were not normally distributed; therefore, a K-means cluster analysis was conducted on all CH4 flux data from which two clusters of CH4 fluxes were identified: low (0.02–149 kg C-CH4 ha−1 yr−1) and high (326–724 kg C-CH4 ha−1 yr−1) (Fig. 1). Low and high CH4 fluxes were observed in intact wetlands, but with a majority of the CH4 flux data (67%) falling within the low cluster (Fig. 1). Only low CH4 fluxes were observed in drained and restored wetlands.

Net cooling vs. warming effect of wetlands

We focused on the effect of wetland state conversion on radiative forcing and changes in mean surface temperature (see Methods section for detailed information on wetland state conversion scenarios). The GHG perturbation model was used to simulate the atmospheric inventories of wetland-derived CO2 and CH4 at any given time, and to estimate the pattern of radiative forcing (instantaneous and cumulative) and mean surface temperature change (K) following the conversion of wetland state (from intact to intact, intact to drained, and drained to restored). The model input was the compiled wetland GHG flux data (by low vs. high flux categories for CH4) for each wetland state. The model output was the atmospheric concentration of wetland-derived carbon-based GHGs at any given time, which was then used to calculate the instantaneous radiative forcing (Wm−2) and cumulative radiative forcing (Wm−2) of the wetland carbon-based GHG fluxes. Meanwhile, the approximate impact of instantaneous and cumulative radiative forcings on the mean surface temperature were estimated as ~1 K per 1.23 Wm−2 radiative forcing.

For each of the wetland state conversion scenarios, a 50-year pre-conversion and a 500-year post-conversion time-period was used, as a 500-year allows for successional steady states to occur in many terrestrial ecosystems, including wetland ecosystems15,21. For each conversion scenario, the baseline was what would happen if the wetland conversion did not take place. For example, for the scenario of draining of intact wetland with low or high CH4 flux, the baseline was maintaining intact wetland with low or high CH4 flux, respectively. Further, for the scenario of restoring of drained wetlands, the baseline was remaining as drained wetlands (See Methods section for details on how the comparisons to baseline scenarios were made). We simplified the modelling of the effect of wetland carbon dynamics on the climate by assuming that yearly wetland carbon sequestration rates and the GHG emission factors were constant within each wetland state.

Initiating intact wetlands with low CH4 fluxes (at year −50) resulted in a small and short net warming effect and maintaining these wetlands with low CH4 fluxes (at year 0) resulted in a net cooling effect over the 500-year timeframe (Fig. 2a, d). In contrast, initiating intact wetlands with high CH4 fluxes (at year −50) resulted in a net warming effect over the entire 500-year timeframe, with a switchover time to a net cooling effect after approximately 1000 years (instantaneous radiative forcing-derived temperature) and 2000 years (cumulative radiative forcing-derived temperature) (Fig. 3). Given that intact wetlands were on the landscape for thousands of years8,34,35, intact wetlands (including those with low and high CH4 fluxes) are currently contributing to a net cooling effect.

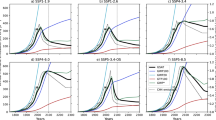

Mean temperature profile for scenarios of (a and d) intact wetland remains intact, (b and e) intact wetland to drained wetland, and (c and f) drained wetland to restored wetland. Panels a–c represent instantaneous radiative forcing derived mean temperature profile; panels d–f represent cumulative radiative forcing derived mean temperature profile. Shaded areas around lines shows Monte Carlo simulation results.

a Instantaneous radiative forcing (RF) and b cumulative radiative forcing (RF) derived mean temperature profile. The point in time on the x-axis when the y-axis value switches from positive to negative represents the time that intact mature wetlands start to deliver a net cooling effect on climate (i.e., the switchover time). Mature intact wetlands emitting low and high CH4 impose a net cooling climate impact in contemporary times (year 0) under both instantaneous and cumulative radiative forcing derived mean temperature profile. Shaded areas around lines shows Monte Carlo simulation results.

Draining intact wetlands with low CH4 fluxes resulted in an immediate net warming effect that was sustained over the 500-year timeframe (Fig. 2b, e). In contrast, draining intact wetlands with high CH4 fluxes resulted in a small and short climate benefit (i.e., smaller warming compared to remaining as an intact wetland with high CH4 fluxes (Fig. 2b, e)). However, this climate benefit switched to a climate detriment (i.e., larger warming) that was sustained over the remainder of the 500-year timeframe.

Restoring drained wetlands to restored wetlands with low CH4 fluxes resulted in an immediate climate benefit (i.e., smaller warming) (Fig. 2c, f) compared to drained wetlands, followed by a net cooling effect. There were no restored wetlands with high CH4 fluxes, and therefore these conversions were not modelled.

Carbon sinks vs. source status

A CO2-e.q. metric was used to assess wetland carbon sinks vs. source status on a comparable basis, thereby directly relating change in net cumulative CO2-e.q. GHG emissions to their temperature responses. The GWP*-derived net carbon sink vs. source status most closely aligned with the GHG perturbation model net cooling vs. warming effect (Fig. 4). Therefore, we focused on comparing the cumulative carbon sink vs. source status of conversion of wetland states (intact-to-intact, intact-to-drained, drained-to-restored) using GWP* vs. earlier GWP and SGWP CO2-e.q. metrics, but also provide the information for GWP and SGWP CO2-e.q. metrics.

Intact wetlands with (a) low and (d) high CH4 fluxes remain as intact. Converting an intact wetland with (b) low and (e) high CH4 fluxes to a drained wetland. Restoring drained wetland to restored wetland with (c) low CH4 fluxes. Inset map represent net CO2-e.q. carbon budget of intact wetland with low CH4 emissions remaining intact during the year of −50 to 100. Shaded areas around lines shows Monte Carlo simulation results.

Based on GWP*, initiating an intact wetland at year −50 with low CH4 fluxes resulted in a relatively small increase in the net CO2-e.q. carbon source for about 30 years followed by a decrease for about 10 years and then a switch to a net CO2-e.q. carbon sink effect (Fig. 4a). In contrast, initiating an intact wetland at year −50 with high CH4 fluxes resulted in a larger magnitude of net CO2-e.q. carbon source effect with an even faster increase in the net CO2-e.q. carbon source effect for the initial 20 years after wetland initiation, and maintaining an intact wetland with high CH4 fluxes (at year 0) resulted in a net CO2-e.q. carbon source effect over the 500-year timeframe (Fig. 4d). For most intact wetlands (i.e., 67% with low CH4 fluxes), intact wetlands functioned as net CO2-e.q. carbon sinks once the suddenly introduced CH4 associated with wetland establishment was neutralized by sustained CO2 uptake, while intact wetlands with high CH4 fluxes functioned as net CO2-e.q. carbon sources with a minor increase in their cumulative CO2-e.q. carbon source strength over the 500-year period. In contrast, based on GWP500 and SGWP500, intact wetlands with low CH4 fluxes functioned as net CO2-e.q. carbon sinks immediately, while intact wetlands with high CH4 fluxes functioned as net CO2-e.q. carbon sources, with their cumulative CO2-e.q. carbon source strength increasing rapidly over the 500-year period (Fig. 4a, d).

Draining intact wetlands with low CH4 fluxes resulted in a short-lived (about 5 years) reduced net CO2-e.q. carbon sink effect due to the cessation of CH4 emissions associated with wetland drainage, followed by an enhanced CO2-e.q. carbon source effect using GWP*, GWP500, and SWGP500 metrics (Fig. 4b). Based on GWP*, draining intact wetlands with high CH4 fluxes resulted in a slightly longer period of net CO2-e.q. carbon sink effect (65 years), after which drained wetlands exhibited a linear increase in CO2-e.q. carbon source effects (Fig. 4e). In contrast, based on GWP500 and SGWP500, draining intact wetlands with high CH4 fluxes resulted in a failure to capture the initial post-drainage carbon sink effect as expressed by a reduction in warming effect and thus an overestimation of the cumulative CO2-e.q. carbon source effect over the 500-year period.

Restoring drained wetlands with low CH4 fluxes resulted in a 110-year reduced net CO2-e.q. carbon source effect followed by an increasing net CO2-e.q. carbon sink effect calculated using GWP*, GWP500, and SWGP500 metrics (Fig. 4c). Restored wetlands with high CH4 fluxes were not observed.

Discussion

The goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep the rise in the Earth’s average temperature well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to actively work towards restricting the temperature increase to 1.5 °C. As stated by the most recent IPCC report1, to achieve this goal, CO2-e.q. carbon emissions need to reach net-zero (i.e., the balance of carbon sources and sinks) by 205026,27. To assess the efficacy of wetlands as natural climate solutions for achieving mid-century net-zero emissions, it is essential to have a method for calculating, reporting, and comparing CO2-e.q. carbon budgets that can establish a reliable connection between wetland carbon sink vs. source status and their corresponding warming vs. cooling effects for various wetland management scenarios. The findings of this study demonstrate that simulating the sustained CO2 and CH4 fluxes as they are emitted from or sequestered by wetlands and their atmospheric behaviour is essential for predicting their warming/cooling effect. Further, using a suitable CO2-e.q. metric that reflects the warming/cooling effect is essential for predicting carbon sink/source status of wetlands in temperate North America (Fig. 5). These findings focus on inland mineral wetlands in temperate North America; however, the GHG perturbation model and CO2-e.q. metrics can be applied to understand the climate impact and carbon role of wetlands in other geographical regions based on regional-specific wetland carbon sequestration and GHG emission factors.

a Intact wetland remains intact, b intact wetland to drained wetland and c drained wetland to restored wetland. The primary and secondary y-axis of a–c employs a consistent scale, respectively, to facilitate visual comparison. The changes in CO2-e.q. carbon budget associated with wetland state conversion match closely with the instantaneous radiative forcing derived mean temperature profile. Shaded areas around lines shows Monte Carlo simulation results.

GWP* offers a straightforward approach to calculating wetland CO2-e.q. fluxes that correspond to their warming/cooling effects (Fig. 5)24,27. The dynamic CO2-e.q. metric (GWP*) provided the most reliable indicator of warming/cooling and established a connection between warming/cooling and the cumulative CO2-e.q. carbon budgets (Fig. 5); other predefined period CO2-e.q. metrics (i.e., GWP, SGWP) obscured these effects (Table 1)23,24. Predefined period CO2-e.q. metrics directly equate wetland CH4 emissions by a single conversion factor and represent only one particular impact over a fixed timeframe (e.g., 100 and 500 years). In contrast, GWP* shares the same characteristics as the GHG perturbation model, allowing for the generation of a dynamic CO2-e.q. carbon budget over any timeframe of interest following wetland state conversion (Table 1), which is essential for the detection of climate benefit/detriment periods24,27. GWP* captures the distinct climate impacts associated with short- and long-lived climate pollutants and more accurately represents the status of net CO2-e.q. carbon source vs. sink following wetland state conversion, which is crucial to understanding the potential of wetlands in serving as effective solutions for mid-century climate targets.

Based on GWP* and the GHG perturbation model, our findings show that intact wetlands with low CH4 fluxes (67% of the intact wetlands in our database) consistently served as cumulative net CO2-e.q. carbon sinks and delivered a net cooling effect (Figs. 2a and 3a). The GHG perturbation model captured the short atmospheric lifetime of CH4 and showed that maintaining intact wetlands characterized by high CH4 fluxes delivered an initial net warming effect with a switchover time to a net cooling effect after approximately 1000 years (instantaneous) and 2000 years (cumulative) (Fig. 3). Given that most intact wetlands in North America have been on the landscape for thousands of years8,34,35, intact wetlands with high CH4 fluxes are effective net CO2-e.q. carbon sinks and deliver net cooling effects on climate in contemporary times. Thus, protecting existing intact wetlands is an effective means of promoting wetlands as natural climate solutions and helping countries to meet their climate change mitigation and adaption targets by 20502,3,4.

Restoring drained wetlands has been widely promoted as an effective means of delivering natural climate solutions4,10,17. There is evidence that suggests that early restored wetlands often exhibits a deficiency in organic matter36,37, imposing constraints on the establishment and activation of microbial communities responsible for CH4 production and, therefore, resulting in lower CH4 fluxes in early restored wetlands compared to intact wetlands. Despite this evidence, concerns have been raised that the overall climate benefit may be offset by the production and release of CH4, since wetland restoration favours environmental conditions (i.e., prolonged hydroperiod) that can promote CH4 emissions6,10,11,12,19,38. Here, with a simple model of wetland radiative forcing of climate and GWP*, we suggest that, despite the increase in CH4 emissions compared to drained wetlands, restored wetlands with low CH4 fluxes are likely to provide immediate climate benefits (i.e., reduced climate warming effect), and help countries to meet their climate target of net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 while providing net climate cooling benefits 110 years after restoration (Figs. 2c and 4c). While this study did not have restored wetlands with high CH4 fluxes, it is possible that such restored wetlands may take longer to reduce and then neutralize the warming effect caused by CH4 efflux through sustained CO2 uptake.

Taking a precautionary approach to restoring wetlands to achieve mid-century climate targets, it is crucial to adopt management interventions that minimize CH4 fluxes from restored wetlands, since effective implementation of wetlands as natural climate solutions is likely to benefit most from simultaneous efforts to reduce both CO2 and CH4 emissions20,24.

Management interventions could be designed to modify physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of restored wetlands to inhibit CH4 production and emission. First, water levels in restored wetlands could be stabilized, since fluctuating water levels have been found to promote wetland CH4 production and emission38,39. Second, loading of sulphate into restored wetlands could be minimised, since sulphate influences the dominant anaerobic metabolism pathway. Specifically, a large abundance of sulphate could suppress CH4 production by altering the dominant anaerobic metabolism pathway from methanogenesis towards pathways that yield higher energy (e.g., SO42− reduction)40,41. Third, the plant community composition of restored wetlands could be optimized, since cutting and/or grazing Typha within restored wetlands could benefit the reduction of CH4 production and emission42. Finally, riparian buffers could be established surrounding wetlands to restrict erosion and runoff induced mobilization of carbon and nutrients into restored wetlands, thereby constraining activities of CH4-producing microbes and reducing wetland CH4 emissions43,44. However, it is important to recognize the potential for synergies and tensions in the implementation of wetland CH4 mitigation strategies in restored wetlands43. For instance, removing or altering vegetation (e.g., Typha) to control CH4 emissions can lead to a rapid progression towards a less biodiverse wetland plant community composition43,44, which may have cascading effects throughout the wetland ecosystem.

Our study had several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, empirical data were sparse, making it impossible to “standardize” the data for individual wetlands (i.e., carbon sequestration and CO2 and CH4 measurements at the same wetland), using common sampling windows (e.g., year-round measurements) and common sampling techniques30. Continuous monitoring of wetland CO2 and CH4 fluxes at individual wetlands throughout the year using similar techniques are needed to reduce uncertainties in wetland radiative forcing and GHG budget analysis imposed by the available dataset30. For example, the growing flux tower networks in North America and the recently launched MethaneSAT mission satellite measurements45 hold promise for the future.

Second, there is growing evidence of variability in annual wetland GHG fluxes in the early years after wetland state conversion3,17, which suggests that using a constant emission factor to represent post conversion wetland GHG fluxes will likely impose biases in GHG budget assessments. Continuous monitoring of wetland CO2 and CH4 fluxes in wetlands that have undergone state conversions are needed to reduce uncertainties in short- and long-term GHG budgets17.

Third, there is growing evidence of the importance of water table level changes on wetland carbon fluxes19,39,46. Lowering of the water table level associated with wetland drainage exposes SOC pools above the water table to oxygen, which enhances the rate of decomposition and CO2 emission18,19. In contrast, wetland rewetting effectively inhibits CO2 production and emission, but also enhances the production and emission of CH420. Our study did not explicitly consider the effect of water level change on wetland carbon flux patterns and their climate impacts, since detailed information on water level changes was not consistently provided for the studies from which we compiled the data, making it challenging to analyse the effects comprehensively. Future research is needed to explore further the effects of changes in water table levels on GHG fluxes.

Fourth, ongoing climatic variability and climate change will impose complexities in developing a predictive understanding of GHG flux patterns of wetlands under different states. Our simulations of radiative forcing and CO2-e.q. carbon budget change following wetland state conversion did not consider concurrent wetland responses to climatic variability or climate change. Future research is needed that considers the interactive effects of climatic variability and climate change on different wetland conversion scenarios, which is crucial for more accurately assessing wetland radiative forcing and GHG budget change associated with wetland management.

Fifth, our study assumed that carbon exchange due to lateral flux of dissolved organic carbon and dissolved inorganic carbon was negligible, which could be justified for inland marshes with no surface inflow or outflow33. To extend this study to coastal and tidal marshes, the lateral import and export of carbon must be considered33,47,48.

Finally, our study focused on carbon-based wetland GHGs and did not take nitrous oxide (N2O) into consideration when assessing wetland GHG radiative forcing and changes in CO2-e.q. emission profiles associated with wetland state conversion. Although N2O fluxes are found to be negligible compared to CO2 and CH4 fluxes in inland mineral soil wetland settings17,49,50, a consideration of N2O might allow more comprehensive assessment of the potential of wetlands to serve as natural climate solutions. Integration of long-term N2O fluxes into the GHG budgets of inland mineral soil wetlands will likely increase the net climate benefit of wetland restoration given the considerable amount of N2O production and emission from drained wetlands in agricultural settings during irrigation or precipitation events17,51.

Wetland protection and restoration measures have typically focused on non-carbon benefits5,52. However, this study demonstrates that wetland protection and restoration measures can lead to substantial carbon benefits. Draining intact wetlands should be reduced if not stopped. Despite the existence of a short-term climate benefit period associated with cessation of CH4 emissions, the continued increase in CO2-e.q. carbon source strength, due to consistent CO2 emissions from drained wetlands and the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere, imposes a long-term warming effect on the climate that will persist for an indefinite period3. Most intact and restored wetlands served as natural climate solutions for mid-century net-zero emission initiatives. To achieve the initiative of net-zero carbon emission by 2050 and ultimately the Paris Agreement, it is crucial to protect intact wetlands and promptly restore drained ones, while simultaneously implementing effective interventions to control CH4 fluxes from restored wetlands.

Methods

Wetland conversion scenarios

Three wetland scenarios (Supplementary Table SI-1) were established to assess the net warming vs. cooling effect and the carbon sink vs. source status (and the switchover time from carbon source to sink) associated with wetland conversion. For scenario 1, the pre- and post-conversion wetland states were intact. We assumed wetlands were initiated at year −50 and remained intact from year 0 to 500 years. For scenario 2, the pre-conversion wetland state was intact, and the post-conversion wetland state was drained. We assumed wetlands were initiated at year −50 and remained intact for 50 years before being drained at year 0, remaining drained for the next 500 years. Scenario 1 was used as a baseline scenario to compare against the conversion of intact wetlands to drained wetlands. For instance, the baseline scenario used to compare against draining intact wetlands with high CH4 fluxes is maintaining intact wetlands with high CH4 fluxes. For scenario 3, the pre-conversion wetland state was drained, and the post-conversion wetland state was restored. We assumed drained wetlands were drained at year −50 and remained drained for 50 years before being hydrologically restored at year 0, remaining restored for the next 500 years. Scenario 2 was used as a baseline scenario to compare against the conversion of drained wetlands to restored wetlands.

The decision to set the pre-conversion period as 50 years was made based on two factors. First, our GHG perturbation model results (Supplementary Figs. SI-1 and SI-2) indicated that the time for newly initiated wetlands, newly drained wetlands, and newly restored wetlands to reach their radiative balance steady state was approximately 50 years based on CH4 (i.e., once the rate of CH4 emission and atmospheric CH4 removal are approximately balanced), while CO2 radiative effects never reach steady state given its indefinite time to equilibrate with various external reservoirs including geological scale weathering of continental rocks13,31. Second, if we considered year 0 in our wetland conversion scenarios as the present year (approximately 2020), then the 50-year pre-conversion period allowed us to start our modelling from the year of 1970. This allowed us to better align our model results to the real-world, where extensive human induced wetland state conversion in North America started around 197052.

We compiled CO2 and CH4 flux data as inputs for the model, simulated the net warming effect associated with wetland CH4 emission and cooling effect associated with wetland CO2 uptake using the GHG perturbation model for each scenario, and calculated the net carbon source/sink status of the wetland conversion using CO2-e.q. metrics for each scenario. For each wetland scenario, Monte Carlo simulations (n = 1000 iterations) of the GHG perturbation models and CO2-e.q. carbon budget calculations were used to capture the uncertainty in switchover times due to the variability in compiled wetland carbon sequestration rates and carbon-based GHG fluxes from different published and unpublished sources33.

Wetland carbon sequestration and GHG fluxes

Wetland carbon-based GHG flux data were compiled from published and unpublished (held by investigators) sources from the temperate region of North America (Fig. 1). Carbon sequestration data were estimated from eddy covariance measurements of net ecosystem exchange and from radioisotope dating of organic carbon in wetland sediments. Radioisotope measurements represent recent records (since 1963) of sediments derived from 137Cs and 210Pb dating53. Carbon based GHG fluxes (i.e., CO2 and CH4) data were estimated from eddy covariance- and chamber-based measurements (c.f. Supplementary Information 3 - Supplementary Data 1).

Our compiled wetland carbon sequestration and GHG flux data represents different types of freshwater mineral soil wetlands such as inland marsh, coastal/tidal marsh, constructed marsh, managed marsh, and swamps. However, it was not possible to assess wetland conversion induced radiative forcing and change in CO2-e.q. carbon budget for all types of freshwater mineral soil wetlands due to the lack of data for all wetland states (i.e., intact, drained, and restored wetlands). We therefore restricted wetland carbon sequestration and GHG flux data to represent inland marshes only.

Compiled CO2 data for the various inland marsh states were normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test, p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. SI-3). However, the compiled CH4 flux data for different inland marsh states exhibited a large range of variability and were not normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test, p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. SI-3) but became normally distributed on a logarithmic scale (Supplementary Fig. SI-4). A K-means cluster analysis was conducted to establish two CH4 flux ranges (low and high), and the CH4 flux data from different wetland states were binned into low and high CH4 fluxes (Fig.1).

Net cooling vs. warming effect of wetlands

The GHG perturbation model simulates the atmospheric inventories of wetland carbon based GHGs and estimates CO2 and CH4 induced radiative forcing by considering the following three factors13.

First, the radiative efficiencies and atmospheric residence times of CO2 and CH4. The radiative efficiency of CO2 is 1.75 ×10−15 Wm−2 per kg CO2 and the radiative efficiency of CH4 is 1.28 ×10−13 Wm−2 per kg CH426. CH4 is a short-lived climate pollutant and has the atmospheric lifetime of 12 years, while there is no single lifetime can be defined for CO2 (i.e., lifetimes range from 3.4 to 108 years)13,14.

Second, the oxidation of CH4 to CO2. The oxidation of CH4 in the atmosphere involves reaction with the hydroxyl free radical (OH), producing CO2 and H2O as the primary products29.

Third, the atmospheric CO2 feedback among various non-atmospheric reservoirs. Atmospheric CO2 equilibrates with three non-atmospheric reservoirs (i.e., external biological, hydrological, and geological reservoirs) over a variety of timescales, resulting in an exchange of CO2 between the atmosphere and the non-atmospheric reservoirs. For instance, atmospheric CO2 will have short-term exchange with the surface ocean, and long-term (geological scales) exchange with continental rocks. Therefore, atmospheric CO2 fixed by wetlands essentially comes proportionally from each non-atmospheric reservoir.

The atmospheric inventory of CH4 at any given time (t) therefore depends on the rate of wetland CH4 fluxes and the loss rate of antecedent atmospheric CH4 due to oxidation to CO2. Meanwhile, wetland-derived atmospheric CO2 inventory at any given time (t) depends on the rate of wetland CO2 fluxes, and the gain rate of CO2 due to the oxidation of CH4 emitted from the wetland. Further, from a mathematical perspective, the interaction of atmospheric CO2 with non-atmospheric reservoirs is modelled by considering the atmosphere as comprising four independent reservoirs of CO2, each with its own reservoir fraction and a first-order CO2 decay determined by the atmospheric perturbation lifetime15,54. Wetland-derived atmospheric CH4 and CO2 inventories at any given time (t) are therefore estimated using the following mathematical equations:

where MCH4-C is the mass of atmospheric CH4 (g C m−2), FCH4-C is the emission factor (g C m−2 y−1), dt is the time step (0.2 y), and \(\tau {CH}4\) is the atmospheric perturbation lifetime of CH4 (12.4 years).

where \({F}_{{CO}2-c}\) is the CO2 flux factor (g C m−2 y−1), with CO2 fluxes having a negative sign representing carbon sequestration, dt is the time step (0.2 y), \(\tau {CO}2{\_i}\) is the atmospheric perturbation lifetime for each of the four CO2 pools (ranging from 4.3 to 394 years and one pool staying permanently in the atmosphere), and \({f}_{i}\) is the relative fractional size of pool i (ranging from 0.217 to 0.282)54. \({M}_{{CH}4-{ox}}\) is the \([{M}_{{CH}4-C\left(t-1\right)}* {(1-e}^{(-{dt}/\tau {CH}4)})]\) term from Eq. (1), accounting for CH4 oxidation to CO215,55.

The atmospheric inventory of the wetland carbon-based GHG fluxes derived from the GHG perturbation model were subsequently converted into instantaneous radiative forcing of the wetland carbon-based GHG fluxes by multiplying the appropriate radiative efficiency value (i.e., 1.75 ×10−15 Wm−2 per kg CO2 and 1.28 ×10−13 Wm−2 per kg CH4)26. The radiative efficiencies for CH4 were then multiplied by a factor of 1.65 to account for the indirect effects of CH4 on the global radiation balance (e.g., the impact of CH4 on the concentrations of ozone in the troposphere and water vapour in the stratosphere)26. The cumulative radiative forcing of the wetland carbon-based GHG fluxes was calculated by summing up the instantaneous radiative forcing values over the model period. Meanwhile, the impact of radiative forcing on the mean surface temperature was estimated to be 1 K for every 1.23 Wm−2 of radiative forcing20,56.

Wetland carbon sinks vs. source status

GWP is defined as the time-integrated change in radiative forcing due to a pulse emission of a given climate pollutant relative to a pulse emission of the same quantity of CO226.

SGWP is defined as the time-integrated change in radiative forcing due to the sustained emission of a given climate pollutant relative to a sustained emission of the same quantity of CO215. SGWP is like GWP, as both are calculated based on cumulative radiative forcing of each gas, but SGWP is considered superior to the GWP as it explicitly considers the sustained behaviour of wetland carbon-based GHG fluxes by treating wetland GHG emissions as persistent rather than pulse (one-time) events15. The emission of a given climate pollutant (e.g., CH4) was converted into a CO2-e.q. by multiplying the appropriate GWP or SGWP conversion factor (i.e., GWP500 = 11; SGWP500 = 14) for the specific time horizon using the following equation:

where ECO2−eq is the CO2-e.q. emission, EGHG is the emission rate of the GHG (i.e., CH4), GWPH or SGWPH is the time specific conversion factor, and H is the selected time horizon for GWP indices (e.g., 20, 100, 500 years).

GWP* is defined based on the differences in the atmospheric behaviour between CO2 and CH4. Essentially, it considers a greater impact of new CH4 emissions on temperature and recognizes that this impact diminishes after a specific period (i.e., 12 years) by treating (equalizing) sustained emissions of CH4 as one-off release of a fixed amount of CO2, since they both lead to a relatively stable increase in radiative forcing and mean surface temperature24,27.

Accordingly, GWP* establishes means of CO2 equivalence by relating a change in the rate of CH4 emissions to a fixed quantity of CO2. The wetland CO2-e.q. CH4 budget was therefore calculated by accounting for changes in wetland CH4 emission rate (ΔCH4) instead of the magnitude of CH422,23. Cain et al.27 advanced Allen et al.’s22,23 work by accounting for the delayed temperature response associated with thermal equilibration to past increases in CH4 emissions using the following equation:

where ECO2−w.e. is CO2-e.q. emission derived from the GWP*, SLCP refers to short-lived climate pollutants, ΔESLCP is the change in wetland CH4 emission rate over the time interval Δt (years), ESLCP is the current CH4 emission rate, and r and s are the weighting factors assigned to the climate impacts of the change in CH4 emission rate and the current wetland CH4 emissions, respectively (r + s = 1).

The parameters in Eq. (4) (i.e., Δt, r, s) were estimated from published literature. We adopted the same r (=0.75), s (=0.25), and Δt (=20 years) values used by Cain et al.27. With these suggested parameters, the GWP* equation can be further simplified to:

where ESLCP(t) is the current CH4 emission rate, and ESLCP (t − 20) is the rate of CH4 emissions 20 years ago.

Data availability

The compiled wetland carbon sequestration and GHG flux data is available in the Supplementary Document – Supplementary Data 1

Code availability

The codes to produce the analyses presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

IPCC. 2023: Sections. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [eds, Core Writing Team, Lee, H. & Romero, J.]. pp. 35–115 (IPCC, 2023).

Griscom, B. W. et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, 11645–11650 (2017).

Drever, C. R. et al. Natural climate solutions for Canada. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd6034 (2021).

Creed, I. F., et al. Can restoration of freshwater mineral soil wetlands deliver nature-based climate solutions to agricultural landscapes? Fron. Ecol. Evol. 10, 622 (2022).

Thorslund, J. et al. Wetlands as large-scale nature-based solutions: Status and challenges for research, engineering and management. Ecol. Eng. 108, 489–497 (2017).

Bridgham, S. D., Megonigal, J. P., Keller, J. K., Bliss, N. B. & Trettin, C. The carbon balance of North American wetlands. Wetlands 26, 889–916 (2006).

Ausseil, A. G., Jamali, H., Clarkson, B. R. & Golubiewski, N. E. Soil carbon stocks in wetlands of New Zealand and impact of land conversion since European settlement. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 23, 947–961 (2015).

Loder, A. L. & Finkelstein, S. A. Carbon accumulation in freshwater marsh soils: A synthesis for temperate North America. Wetlands 40, 1173–1187 (2020).

Nahlik, A. M. & Fennessy, M. Carbon storage in US wetlands. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–9 (2016).

Li, T. et al. Methane emissions from wetlands in China and their climate feedbacks in the 21st century. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 12024–12035 (2022).

Bao, T., Jia, G. & Xu, X. Weakening greenhouse gas sink of pristine wetlands under warming. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 462–469 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Recent intensification of wetland methane feedback. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 430–433 (2023).

Frolking, S., Roulet, N. & Fuglestvedt, J. How northern peatlands influence the Earth's radiative budget: Sustained methane emission versus sustained carbon sequestration. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 111, G01008 (2006).

Neubauer, S. C. On the challenges of modeling the net radiative forcing of wetlands: reconsidering Mitsch et al. 2013. Landsc. Ecol. 29, 571–577 (2014).

Neubauer, S. C. & Megonigal, J. P. Moving beyond global warming potentials to quantify the climatic role of ecosystems. Ecosystems 18, 1000–1013 (2015).

Kroeger, K. D., Crooks, S., Moseman-Valtierra, S. & Tang, J. Restoring tides to reduce methane emissions in impounded wetlands: A new and potent Blue Carbon climate change intervention. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–12 (2017).

Hemes, K. S. et al. Assessing the carbon and climate benefit of restoring degraded agricultural peat soils to managed wetlands. Agric. For. Meteorol. 268, 202–214 (2019).

Huang, Y. et al. Tradeoff of CO2 and CH4 emissions from global peatlands under water-table drawdown. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 618–622 (2021).

Zou, J. et al. Rewetting global wetlands effectively reduces major greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Geosci. 15, 627–632 (2022).

Günther, A. et al. Prompt rewetting of drained peatlands reduces climate warming despite methane emissions. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–5 (2020).

Whiting, G. J. & Chanton, J. P. Greenhouse carbon balance of wetlands: methane emission versus carbon sequestration. Tellus B 53, 521–528 (2001).

Allen, M. R. et al. New use of global warming potentials to compare cumulative and short-lived climate pollutants. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 773–776 (2016).

Allen, M. R. et al. A solution to the misrepresentations of CO2-equivalent emissions of short-lived climate pollutants under ambitious mitigation. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 1–8 (2018).

Lynch, J., Cain, M., Pierrehumbert, R. & Allen, M. Demonstrating GWP*: a means of reporting warming-equivalent emissions that captures the contrasting impacts of short-and long-lived climate pollutants. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 044023 (2020).

Neubauer, S. C. Global warming potential is not an ecosystem property. Ecosystems 24, 2079–2089 (2021).

Myhre, G., et al. Anthropogenic and natural radiative forcing. In Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (eds, Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P. M.) 659–740 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Cain, M. et al. Improved calculation of warming-equivalent emissions for short-lived climate pollutants. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2, 1–7 (2019).

Chiquier, S., Fajardy, M. & Mac Dowell, N. CO2 removal and 1.5° C: what, when, where, and how. Energy Adv. 1, 524–561 (2022).

Dean, J. F. et al. Methane feedbacks to the global climate system in a warmer world. Rev. Geophys. 56, 207–250 (2018).

Bansal, S. et al. Practical guide to measuring wetland carbon pools and fluxes. Wetlands 43, 105 (2023).

Taillardat, P., Thompson, B. S., Garneau, M., Trottier, K. & Friess, D. A. Climate change mitigation potential of wetlands and the cost-effectiveness of their restoration. Interface Focus 10, 20190129 (2020).

Schuster, L., Taillardat, P., Macreadie, P. I. & Malerba, M. E. Freshwater wetland restoration and conservation are long-term natural climate solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 922, 171218 (2024).

Arias‐Ortiz, A. et al. Tidal and nontidal marsh restoration: A trade‐off between carbon sequestration, methane emissions, and soil accretion. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 126, e2021JG006573 (2021).

Eisenlohr, W. S. Jr Measuring evapotranspiration from vegetation-filled prairie potholes in North Dakota. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 3, 59–65 (1967).

Yansa, C. H. Holocone paleovegetation and paleohydrology of a prairie pothole in southern Saskatchewan, Canada. J. Paleolimnol. 19, 429–441 (1998).

Wang, G. et al. Does the element composition of soils of restored wetlands resemble natural wetlands? Geoderma 351, 174–179 (2019).

Gao, J. et al. Disentangling responses of the subsurface microbiome to wetland status and implications for indicating ecosystem functions. Microorganisms 9, 211 (2021).

Holgerson, M. A. & Raymond, P. A. Large contribution to inland water CO2 and CH4 emissions from very small ponds. Nat. Geosci. 9, 222–226 (2016).

Evans, C. D. et al. Overriding water table control on managed peatland greenhouse gas emissions. Nature 593, 548–552 (2021).

Poffenbarger, H. J., Needelman, B. A. & Megonigal, J. P. Salinity influence on methane emissions from tidal marshes. Wetlands 31, 831–842 (2011).

Soued, C. et al. Salinity causes widespread restriction of methane emissions from small inland waters. Nat. Commun. 15, 717 (2024).

Bansal, S. et al. Typha (cattail) invasion in North American wetlands: biology, regional problems, impacts, ecosystem services, and management. Wetlands 39, 645–684 (2019).

Hambäck, P. A. et al. Tradeoffs and synergies in wetland multifunctionality: A scaling issue. Sci. Total Environ. 862, 160746 (2023).

Zamberletti, P., Zaffaroni, M., Accatino, F., Creed, I. F. & De Michele, C. Connectivity among wetlands matters for vulnerable amphibian populations in wetlandscapes. Ecol. Model. 384, 119–127 (2018).

Chan Miller, C. et al. Methane retrieval from MethaneAIR using the CO2 proxy approach: a demonstrationfor the upcoming MethaneSAT mission. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 17, 5429–5454 (2024).

Webster, K. L., Creed, I. F., Malakoff, T. & Delaney, K. Potential vulnerability of deep carbon deposits of forested swamps to drought. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 78, 1097–1107 (2014).

Chu, H. et al. Climatic variability, hydrologic anomaly, and methane emission can turn productive freshwater marshes into net carbon sources. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 1165–1181 (2015).

Krauss, K. W. et al. Component greenhouse gas fluxes and radiative balance from two deltaic marshes in Louisiana: Pairing chamber techniques and eddy covariance. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 121, 1503–1521 (2016).

McNicol, G. et al. Effects of seasonality, transport pathway, and spatial structure on greenhouse gas fluxes in a restored wetland. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 2768–2782 (2017).

Kandel, T. P., Lærke, P. E., Hoffmann, C. C. & Elsgaard, L. Complete annual CO2, CH4, and N2O balance of a temperate riparian wetland 12 years after rewetting. Ecol. Eng. 127, 527–535 (2019).

Firestone, M. K. & Davidson, E. A. Microbiological basis of NO and N2O production and consumption in soil. In Exchange of trace gases between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere: report of the Dahlem workshop on exchange of trace gases between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere, 47, 7–21 (Wiley, 1989).

Fluet-Chouinard, E. et al. Extensive global wetland loss over the past three centuries. Nature 614, 281–286 (2023).

Appleby, P.G. 210Pb dating: Thirty-five years on. J. Paleolimn. 49, 697–702 (2013).

Joos, F. et al. Carbon dioxide and climate impulse response functions for the computation of greenhouse gas metrics: a multi-model analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2793–2825 (2013).

Neubauer, S. C. & Megonigal, J. P. Correction to: Moving Beyond Global Warming Potentials to Quantify the Climatic Role of Ecosystems. Ecosystems 22, 1931–1932 (2019).

Stocker, T. F. et al. in Climate Change 2013 (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 33–118 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the associated editor and two reviewers (Pierre Taillardat and an anonymous reviewer) for their thoughtful feedback which improved the manuscript. This work was funded by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (05265-2019), an NSERC Strategic Partnership Grant (STPGP 506809), and an Environment and Climate Change (ECCC) Climate Action and Awareness Fund (CAAF) Grant (EDF-CA-2021i023) to I.F.C. Additional funding includes a Global Water Futures PhD Excellence Scholarship awarded to S.M. We thank David Aldred for assistance with figures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. conceptualized and designed the study, performed the analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. I.F.C. compiled the data, contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study and manuscript preparation, and provided funding. P.B. assisted in the conceptualization and design of the study and manuscript preparation. All authors jointly revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, S., Creed, I.F. & Badiou, P. New perspectives on temperate inland wetlands as natural climate solutions under different CO2-equivalent metrics. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 222 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00778-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00778-z