Abstract

Ice core oxygen isotope (δ18O) records from low-latitude regions preserve high-resolution climate records in the past, yet the interpretation of these ice core δ18O records is still facing difficulty due to the uncertainty of ice core dating. Here we present a new established δ18O time series from Qiangtang (QT) No. 1 ice core retrieved from the central Tibetan Plateau. Due to the vague seasonal signals in the QT ice core, we investigated the spectral properties of δ18O record with depth and discussed the implications of significant spectral power peaks in the QT ice core. We employed a variational mode decomposition (VMD) analysis for the upper part of the QT ice core to decompose the δ18O depth series in order to separate the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) mode, a signal strongly preserved in the QT ice core δ18O record. With this approach, we established a time series of 335 years (1677–2011 CE) for the upper 50 m of the QT ice core. Subsequently, we examined the frequency of the new established δ18O time series and detected strong signals of the bidecadal and multidecadal modes of Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). The PDO consists of two modes with periods of approximately 25–35 years and 50–70 years, and we found that the 50–70 years periodicity has persisted since 1700 CE, succeeded by dominance of the 25–75 years periodicity after 1900 CE. Additionally, we analyzed the δ18O series of the QT ice core during the past century and determined that the increasing frequency of El Niño events is an important factor contributing to the increase in recent ice core δ18O.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oxygen isotopes (δ18O) in ice cores serve as natural proxies for past climate change and atmospheric circulation variations1,2. Ice core analyses in polar regions have yielded valuable insights into Earth’s paleoclimate history during the Glacial-interglacial timescale3,4. δ18O records in some ice cores drilled on the Tibetan Plateau (TP) have been interpreted as temperature proxies5,6. Recent studies on isotopic composition of tropical and monsoon precipitation have demonstrated that regional convective intensity, rather than the local temperature, is the dominant factor controlling precipitation δ18O influenced by both the local precipitation process and the δ18O of upstream water vapor that feeds subsequent precipitation7,8. The Asian monsoon (AM) is significantly influenced by El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) activities9, which subsequently affects the precipitation δ18O10,11.

Interannual variations in precipitation δ18O driven by ENSO can be preserved in ice core records. Simulation studies have demonstrated a close relationship between the interannual variation of δ18O in the Dasuopu ice core from the Himalayas and monsoon index, highlighting the strong influence of large-scale monsoon circulation12. Variations in δ18O and dust in ice core records are significantly correlated with large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns in the central TP13. The interannual variation of δ18O in the central TP ice core exhibits a strong inverse correlation with the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), and it is concluded that the driving factor of the interannual variation of δ18O in the central TP ice core is periodic large-scale atmospheric circulation in association with the ENSO cycle, rather than local temperature change2. Recently, this correlation has also been identified in ice cores from the Northwestern TP, confirming the large regional impact of this interaction14.

One major challenge in Tibetan ice core studies is the difficulty in precise dating, which hinders the retrieval of climate signals from this archive15. Only the Dasuopu ice core6, characterized by sufficient winter-spring precipitation that generates a distinct seasonal signal in the δ18O record, allows for accurate dating using an annual layer counting method. However, most inland ice cores lack clear δ18O seasonality16, characterized by a single monsoon season decrease in δ18O. Annual-scale dating of Tibetan ice core can be constrained by the nuclear bomb layer in the upper part of the core, a method validated by the presence of the nuclear bomb layer17. Radioactive dating methods such as 14C18, trapped noble gases (39Ar, 85Kr and 81Kr)19,20 and δ18O of the trapped air21,22 provide new solutions for ice core dating at different age range, yet the resolution is not satisfactory. The challenge of Tibetan ice core dating has evoked an argument on the reliability of ice core chronology15,23,24. Achieving annual-resolution ice core dating remains challenging, thus hampering the high temporal-resolution interpretation of these ice core records.

The strong correlation between historical δ18O signals and the SOI motivated us to further analyze their potential relationship over an extended period. We assumed that this relationship between them holds over an even longer period. Indeed, long-term correlations have been found in other δ18O archives, utilizing high-resolution dating obtained from various proxies including tree ring, stalagmite records, coral records, and giant clams25,26,27,28. High-resolution dating has enabled the retrieval of the ENSO fluctuation signal from Antarctic ice cores, even during the glacial age3. Longer periods of continuous decadal climate variability, such as the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO), have also been reconstructed in the Pacific ice core δ18O records1.

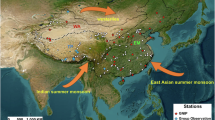

In this paper, we initially employed a new method to establish a high-resolution δ18O time series for the QT ice core (see Methods) retrieved from the central Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 1), by performing spectral analysis of the δ18O depth series from the upper 50 m (D1-D5 intervals) of this ice core and subsequently matching the ENSO frequency mode with the known ENSO interannual index. Then we built a δ18O time series for the QT ice core over the past three centuries. With the newly established high-resolution time series for this ice core, we further analyzed the frequency changes, particularly the PDO frequency and its shift within this ice core record. Furthermore, we discussed the recent increase in δ18O in this ice core, and the direct cause of this increase.

Results and discussion

Depth series analysis

The multitaper method (MTM)29 (see Methods) spectral results of the δ18O depth series of the QT ice core were calculated (Fig. 2). Table 1 presents the period length and sample number corresponding to the significant frequencies. In the D1 interval, the MTM spectrum manifests itself with prominent peaks at frequencies of 1.1–1.5 cycles/m, 3.4 cycles/m, and 6.5 cycles/m (Fig. 2), and the corresponding periods lengths for these three frequencies are 0.67–0.91 m, 0.29 m, and 0.15 m, respectively. The peaks of other frequencies are below the 95% confidence curve; therefore, the indicative significance of these frequencies will not be discussed in this study. Several studies have indicated a strong coherence in interannual variations between precipitation δ18O and ENSO cycles in the Asian Monsoon (AM) region10,11. Previous study found that precipitation δ18O in the AM region was particularly sensitive to ENSO by choosing four caves, and ENSO played a key role in modulating interannual precipitation δ18O in the AM region30. Moreover, power spectrum analyses of stable isotope records (δ18O and δ13C) of a Holocene stalagmite from central China show that significant periodicities probably correlated to ENSO-like cycles31, and ice core from the northern TP demonstrate that ENSO is one of a variety influencing its δ18O changes14. In the upper part of the QT ice core (above the radioactive layer), the annual variation of the QT ice core δ18O shows a significant anti-phase change with the SOI annual series, with a correlation coefficient of r = −0.632. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that the most significant frequencies of 1.1–1.5 cycles/m, correspond to the ENSO cycle, and it is referred to as the ice core ENSO mode hereafter.

a–e display δ18O anomalies of the QT ice core depth series in intervals D1-D5, while f–j depict their MTM power spectra. The color bars (red, blue, green) represent the three modes (ENSO, Biennial, Annual) in spectral power (f–j). The spectra were terminated at 8 cycles/m to satisfy the resolution. The MTM parameters are a 2-bandwidth and 3-tapers71. The thick black wiggly lines (f–j) represent the raw spectra. The pink dashed lines (f–j) indicate a 20% median smoothing of the raw spectra64. The thin black lines (f–j) represent the equivalent red noise spectrum obtained through robust median testing, and the thin red solid and dotted lines (f–j) denote the 90% and 95% confidence intervals for the red noise null hypothesis64. All spectral analyses were performed using the Acycle v2.6 program72.

Previous studies analyzing monsoon rainfall and tropical meridional winds have shown two distinct cycles on an interannual scale: the quasi-biennial oscillation (2–3 years) known as the tropospheric biennial oscillation (TBO), and the longer-term scale (4–5 years) associated with ENSO32,33. Throughout the vertical atmosphere of the AM, the quasi-biennial oscillation of various climate variables (e.g., wind speed, moisture, and water vapor temperature) is significant34, suggesting that TBO is an important controlling factor for the AM34,35. It is reasonable to assume that the ice core δ18O depth series also captured the influence of TBO signal on precipitation δ18O in the monsoon region. Additionally, the period ratio corresponding to the two frequencies (3.4 cycles/m and 1.1–1.5 cycles/m) is 2: (4–6), with the main period of ENSO being 4–6 years. We propose that the frequency of 3.4 cycles/m reflects the biennial accumulation of the ice core, termed the ice core Biennial mode. Previous dating results using the radioactive layer at the upper 10 m of the ice core showed that the average number of samples in each annual layer are mainly concentrated in the range of 4–62, roughly consistent with the peak frequency of 6.5 cycles/m or 5 samples/cycle in the D1 interval. For the peak frequency of 6.5 cycles/m, the period ratio corresponding to these three frequencies (6.5 cycles/m, 3.4 cycles/m, and 1.1–1.5 cycles/m) is 1: 2: (4–6). Therefore, the frequency of 6.5 cycles/m corresponds to the annual accumulation of the ice core, called the ice core annual mode. The same method was applied to the D2-D5intervals, allowing for the identification of annual, biennial, and ENSO modes during the ice core accumulation based on these three significant frequencies (Table 1).

Determination of IMFs representing signal

Supplementary Table 1 lists the results of intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) (see Methods) center frequency in the D1 interval based on the variational mode decomposition (VMD)36 (see Methods). The center frequency of 1.1 cycles/m exists in all the mode decompositions, indicating that the ENSO mode appears for different k values between 3 and 6. However, when k = 3, neither the biennial mode nor the annual mode can be separated, and when k = 4 and 5, the annual mode cannot be separated. Therefore, k = 3, 4, and 5 are not consistent with the frequency analyses (Table 1), and cannot be used to separate the ENSO, biennial, and annual modes in the ice core depth series. When k = 6, IMF2 (center frequency = 1.1 cycles/m) represents the ENSO mode, IMF3 (center frequency = 3.3 cycles/m) represents the biennial mode, and IMF4 (center frequency 6.2 = cycles/m) represents the annual mode, consistent with the analysis results of the D1 interval spectrum in section “Ice core drilling site and sample measurement” (Fig. 2). This indicates that the selection of k = 6 is reasonable in the VMD decomposition of the D1 interval. Other parameters of VMD are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Figure 3 presents IMFs and the corresponding spectral graph with k = 6. Results for k = 3–5 are shown in Supplementary Figs. 1–3, and there is no obvious aliasing phenomenon among the center frequencies of each IMFs with the different of k values.

In the same way, we performed the decomposition algorithm to the D2-D5 intervals and obtained their corresponding center frequencies (Table 2). When k = 6, the ENSO, biennial, and annual modes of the QT ice core δ18O depth series can be completely separated. The center frequency values of the separate mode are basically consistent with the frequency analysis results in section “Ice core drilling site and sample measurement”, particularly the ENSO mode in the ice core depth series. Supplementary Figs. 4–7 show the results of the D2-D5 intervals with k = 6, and the IMFs does not have frequency aliasing.

We compared the center frequency values of the three modes (ENSO, Biennial, annual) for the five intervals (D1-D5), and found that the center frequency values of the ENSO mode ranging from 1.1 to 1.6, the biennial mode ranging from 2.3 to 3.3, and the annual mode ranging from 5.1 to 6.5 (Table 2). The ENSO mode (IMF2) exhibits the highest correlation with the original depth series of the QT ice core δ18O record (Supplementary Table 3).

As the annual precipitation amounts varies with time, the annual accumulation rates vary as well37. Consequently, the center frequency of each mode changes within a certain range with ice core depth. Although the center frequency values vary among the biennial and annual modes across different depth series, they consistently maintain a ratio of approximately 2:1. This suggests that the biennial and annual modes are reliably captured in the QT ice core δ18O spectra analysis, facilitating subsequent ice core dating processes.

Dating of the QT ice core (0-50 m)

The upper part of the QT ice core is dated by comparison with an earlier shallow ice core drilled in 2011, validated by the presence of a peak in radioactive (total β activity, 3H, 137Cs) layer detected at a depth of 9.2 m2. Then, the annual layers were determined based on the weak seasonal variations of δ18O and chemical components. The dating results above the radioactive layer (about 9.2 m) are deemed reliable. However, below this depth, the dating result of this ice core is difficult to evaluate and might bear more uncertainties as the seasonal fluctuation of particle concentration and d-excess in the ice core are vague. Radioactive dating based on 39Ar in the trapped gas in this ice core, yielded a timescale that covers the past 1300a19, yet the time resolution of this new method is not satisfied for a near annual time scale dating.

We compared the ENSO, biennial, and annual modes in the D1 interval of ice core with the ENSO index (Fig. 4). As the annual accumulation rate varies with time, which will influence the ice core δ18O series with depth, we adjusted the peak (or minimum) of the ENSO index time series (Fig. 4e) to coincide with the peak (minimum) of the ENSO mode (IMF2) at depth (Fig. 4d). By aligning the ENSO index with the peak (or minimum) values of the ENSO mode (IMF2), the corresponding sample can be determined in the corresponding year, and the biennial mode (IMF3) (Fig. 4c) and annual mode (IMF4) (Fig. 4b) in the D1 interval are used as auxiliary indicators to determine the number of annual samples. Therefore, the δ18O depth series can be transferred to a δ18O time series from the ENSO time series. We utilized δ18O data at depths ranging from 6.64 m to 8.65 m from the QT ice core as an example to describe the dating method (Fig. 5). We first identified four key points (at depth of 6.88 m, 7.24 m, 7.51 m, and 8.35 m) matching with the four annual layers (1975 CE, 1972 CE, 1971 CE, and 1967 CE) by comparing the ENSO mode (IMF2) with the ENSO index (Fig. 5c). Then, we employed the Biennial mode (IMF3) and Annual mode (IMF4) to identify the samples in each of the annual layer sample, in that half of an IMF3 cycle and one complete IMF4 cycle represent one year (Fig. 5a, Table 3). As an example in Fig. 5a, half of the IMF3 signal cycle around the sample at 6.88 m depth includes four samples at 6.79 m, 6.82 m, 6.85 m, and 6.91 m depth. The five samples are assigned to the 1975 CE annual layer with averaged δ18O value of −14.17‰ (Table 3). In the similar way, the four samples at 6,64 m, 6.7 m, 6.73 m, and 6.76 m depth are assigned to the 1976 CE annual layer (Fig. 5a, Table 3), and samples at 6.94 m, 6.97 m, 7.00 m, and 7.03 m depth are assigned to the 1974 CE layer (Fig. 5a, Table 3). The amplitude of these two modes is lower than that of the ENSO mode (IMF2) (Fig. 3), and the two modes are not as prominent as the ENSO mode (IMF2) (Fig. 2). Therefore, we properly adjusted the number of annual samples to preferentially correspond to the ENSO mode (IMF2) in practice.

a The QT ice core δ18O depth series (gray line) and the dating result (red dotted). b The annual mode (IMF4). c The biennial mode (IMF3). d The ENSO mode (IMF2). e The ENSO index. To align the peak (or minimum) in the ENSO index time series with that in the ENSO mode (IMF2) with depth, and therefore the time coordinates of ENSO index are not in linear scale.

a The biennial mode (IMF3) and the annual mode (IMF4) in depth of 6.64–8.65 m, the black and red boxes represent annual layers, respectively. b Comparison of the δ18O depth series in the depth of 6.64–8.65 m, δ18O dating series and the ENSO index from 1976 CE to 1966 CE. c The matching of ENSO mode (IMF2) in the D1 interval and its corresponding ENSO index from 2011 CE to 1960 CE.

The dating method and results for the QT ice core in the D1 interval (Fig. 4) yield an age period of 52 years from 2011 CE back to 1960 CE. The average number of samples in annual layer is 6.38 (Table 4), with an annual accumulation rate of 19.14 cm of ice core depth. 3H was measured in the first 20 m of the QT ice core samples37, and the position of the 1963 CE bomb layer was found within the depth range of 8.8–9.2 m of the QT ice core, which is consistent with the dating results of 9.05–9.11 m in this study. This comparison further constrained the dating results for the upper part of this ice core. We applied this approach to date this ice core for each 10 m in the D2-D5 intervals. The dating results are presented in Supplementary Figs. 8–11. The total 50 m of the upper part of the QT ice core is dated to a period of 335 years from 2011 to 1677 CE. The lower part of the ice core was not extended further due to different in ice cutting intervals and the thinning of the annual layers toward to the bottom of the glacier, which may cause a shift of frequencies along the δ18O depth series.

Comparison with previous dating results

We conducted a comparison between our new dating results and the previous dating results37 for the upper 50 m of the ice core. The previous dating results relied on a combination method of seasonal cycle of δ18O, chemical record, and the glacier flow model. The uncertainty arises from the weak seasonal δ18O signal in this ice core, as well as the smoothing effect of the glacier flow model on any annual accumulation signal.

The comparison found that the new dating results in this study is 14 years older than the previous one37 (Table 4). Both methods yielded consistent dating results for the D1 interval, with the dating range of 2011–1960 CE, and the correlation coefficient between the new dating results and the previous dating results with ENSO index are 0.72 (p < 0.01) and 0.6 (p < 0.01), respectively. This consistency is largely attributed to the constraint provided by the bomb layer formed in 1963 CE in the previous dating.

The thickness of annual layers in the ice core gradually decreases with increasing depth. The largest discrepancy between the two dating results occurs in the D2-D3 intervals, with totally 25 years less in the previous dating results37. The previous dating results showed a reversed sequence in the numbers of the dated years in each of the 10 years interval, with D1 (52 years), D2 (46 years), and D3 (50 years), followed by a sharp increase of dated age of 81 years in the D4 interval (Table 4). The comparison also revealed an anomalous increase in the percentage of number of annual layers in the D3-D5 intervals in the previous dating results, and even a negative trend from the D1 to D2 interval. In the new dating results, a consistent correlation was found between the dating δ18O time series and the ENSO index throughout the depth with correlation coefficients ranging 0.43 to 0.72, whereas the correlation was poor in the old dating results, ranging from 0.01 to 0.6 (Table 4).

Frequency shift of PDO over the past century in the δ18O record

We calculated the spatial correlation coefficients between the annual δ18O time series and annual SST throughout the Indo-Pacific region over the past century. The results reveal a significant PDO (IPO) pattern in the North Pacific Ocean (Pacific Ocean) (Fig. 6). The IPO38 and the PDO39,40 are closely related modes of Pacific decadal climate change41, and PDO serves as the North Pacific node of the all-Pacific IPO38. δ18O records from four ice cores surrounding the Pacific, including Dasuopu ice core from Himalayas, indicate a robust and temporally stationary IPO signal for the last 550 years1. Additionally, a significant positive correlation between the ion concentration and PDO was found in the QT ice core, and the phase change of PDO might affects the intensity of the Indian monsoon intensity and subsequently alter ion concentration of this ice core42. The QT ice core isotope record is mainly influenced by the Indian monsoon. However, there are earlier literatures showed that the ice core records from further north, such as the Tanggula ice core13 and the Malan ice core43, may bear increasing influence from the westerlies. The central TP is located in a transition zone44, where westerlies and the Indian monsoon interact, leading to a potential uncertainty regarding the driving factors of ice core isotope record. While this study emphasizes the PDO signal variability recorded by the QT ice core, while other possible factors, except for the Pacific atmospheric circulation are not discussed in this study.

The PDO comprises two modes with approximate bidecadal (20–30 years) and multidecadal (50–70 years) periods39. We linearly superimposed the 25–35 years series and 50–70 years periodicity series from the QT ice core δ18O time series to reconstruct the PDO reconstruction in 1677–2011 CE (Fig. 7a). The correlation coefficients between the PDO reconstruction series and the 9-year running average of the PDO index are 0.57 (n = 112, p < 0.01) for the period 1900–2011 CE (Fig. 7c), and the PDO reconstruction in this study shows good coherence with the other reconstructions in periodic fluctuation (Fig. 7a).

a Comparison of PDO reconstruction (1677–2011 CE) from the QT ice core with two observed indices (PDO index39 and IPO index73) and three PDO reconstructions (LMR Online54, LMR v2.174 and D’Arrigo 200148). Data are shown as 21-year running means. b Wavelet analysis of the PDO reconstruction (1677–2011 CE) from the QT ice core. Black lines represent 95% significance; c Comparison of PDO reconstructions in this study with the observed PDO index (1900–2011 CE). Data are shown as 9-year running means.

Wavelet analysis of the PDO construction indicates a clear shift in the frequency of PDO periodicity. During the multidecadal variability of the QT ice core δ18O record, the 50–70 years periodicity dominants during the period from 1700 CE to 1900 CE, while the 25–35 years periodicity becomes more active after the 1900s (Fig. 7b). The shift in periodicity is believed to be related to global warming, leading to strengthened ocean stratification, accelerated Rossby waves, and consequently, a shortened Pacific multidecadal variability periodicity45. Previous study reported that global warming will shorten the PDO periodicity and adjust it to a higher frequency46.

Previous reconstructions of IPO/PDO have shown the prevailing and persistent nature of the 50–70 years periodicity since 1700 CE47,48,49. This is consistent with our findings from ice core record that, the 50–70 years periodicity has persisted since the 1700 CE (Fig. 7b) and the 25–35 years periodicity is dominated since 1900 CE (Fig. 7b). The intensity of these two frequencies varies over time. Previous study reconstructed the PDO index using northeastern Pacific tree-ring series since 1700 CE, revealing reduced multidecadal variability after 1850 CE48. However, diverse50, and even contradictory47 results were also found in other paleoclimate archives.

Previous results on δ18O in this ice core indicate that large-scale atmospheric circulation controls the interannual isotopic signal through the ENSO cycle2. PDO modulates the effects of ENSO on the Indian monsoon, with El Niño (La Niña) event under warm/positive (cold/negative) PDO phase weakening (strengthening) the monsoon to a greater extent than when ENSO and PDO are out of phase51. PDO modulates the burst frequency and amplitude of ENSO by changing its frequency and phase52, with ENSO significantly influencing convection in the Indo-Pacific region, a dominant control of tropical and monsoon precipitation δ18O compositions7. Therefore, the PDO signal frequency shift is also recorded in the QT ice core, providing strong evidence for using the TP ice core δ18O to reconstruct Pacific climate variability over the past hundreds or even thousands of years.

Mechanism controlling δ18O variations over the past century

The δ18O levels in the QT ice core have notably increased over the past century (Fig. 8a). To address the issue, we utilized the Niño 3.4 SST reconstruction, along with paleo-proxy data assimilations and other proxy indicators, for further discussion. These data include the Paleo Hydrodynamics Data Assimilation product (PHYDA)53 (Fig. 8b) and the Last Millennium Reanalysis Online(LMR Online)54 (Fig. 8c). Additionally, we also compared the Niño 3.4 index reconstructions of Emile-Geay 201355 (Fig. 8d) and Mann 200956 (Fig. 8e), and we found that the increasing trend observed over the past few decades is consistent in the proxy index reconstructions of Niño 3.4 SST (Fig. 8). We calculated 21-year running correlations between the δ18O time series and reconstructions series (Supplementary Fig. 12). The strongest running correlations are observed after 1950 CE, and significant relationships between the ice core δ18O time series and PHYDA and LMR Online are evident across all reconstructions (Supplementary Fig. 12), with correlation coefficients of 0.65 (p < 0.01, 1950–2000 CE) and 0.6 (p < 0.0.1, 1950–2000 CE). This indicates that the ice core δ18O time series and reconstructions of the Niño 3.4 SST all have a good coherent increasing trend in the past century.

To diagnose the reason behind the rise in QT ice core δ18O level over the past century, we analyzed the frequency of El Niño and La Niña events per 30 years from 1900 CE to 2011 CE. A thirty-year period is considered the minimum timeframe to represent the average climate state, and calculating the frequency of El Niño and La Niña events within each thirty-year period effectively captures the climate state in ENSO-affected regions57. As there is no universal standard for reporting the distinction of El Niño and La Niña year, the year in which El Niño and La Niña events began is considered as an El Niño or La Niña year. El Niño and La Niña events data are from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/lnlist). The period of 1900–2011 CE includes 26 El Niño years and 18 La Niña years. The number of El Niño events per 30 years has increased significantly since 1900 CE, whereas the number of La Niña events has declined (Fig. 9). The difference between the frequency of El Niño and La Niña events per 30 years exhibits an increasing trend (Fig. 9). In El Niño years, the Walker circulation and convection weaken in the eastern Pacific Ocean10, resulting in reduced precipitation and less depleted vapor δ18O11,30. While in the La Niña years, stronger deep convection appears in the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea lowers precipitation δ18O values11,58. The results10 demonstrated that precipitation δ18O and the QT ice core δ18O values show robust ENSO signals across the AM region, largely in response to a significant influence of ENSO on convection in the Indo-Pacific region. Therefore, the increasing frequency of El Niño events is a primary factor for the increasing trend in the QT ice core δ18O record since 1900 CE.

Methods

Ice core drilling site and sample measurement

The QT No. 1 glacier, situated in the central of TP, extends about 2 km in length and 1 km in width, with altitudes ranging from 5500 m to 6050 m above sea level (asl) (Fig. 1). The summit thickness of the glacier is 109 m, while its maximum thickness is approximately 132 m. The area undergoes persistent westerly winds in winter and the Indian monsoon in summer59. Meteorological data from an automatic weather station (2012–2016 CE) atop the glacier indicate an average annual temperature of −10.7 °C and an annual precipitation of 486 mm, predominantly falling from May to October60.

In May 2014, two ice cores, Core 1 measuring 109 m and Core 2 measuring 110 m, were retrieved to bedrock at the saddle of the QT No. 1 glacier (33.3° N, 88.69° E, 5890 m asl) (Fig. 1). Samples from the upper 60 m of Core 1 were cut at 3 cm intervals, whereas those from 60 m to the bottom were cut at 2 cm intervals. In this study, we utilized δ18O data from the top 50 m of Core 1. δ18O and δ2H values in these ice core samples were determined using Picarro L2130-i at the key Laboratory of Tibetan Environment Changes and Land Surface Processes, Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The analysis results were presented as deviations in thousandths relative to the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW-2), with accuracies of δ18O ± 0.15‰ and δ2H ± 0.4‰. Additionally, the outer 1 cm of each sample was collected for total β activity and 137Cs analysis to identify the radioactive layer from 1963 CE. The radioactive survey revealed that the deposit depth in 1963 CE ranged from 8.8 m to 9.2 m2.

Climate data

This study uses monthly Sea Surface Temperature (SST) anomalies in the Niño 3.4 region (5°N-5°S, 120°-170°W) to represent the phase and strength of ENSO. These anomalies are sourced from the Met Office Hadley Center’s Sea Ice and SST dataset HadISST1 (https://psl.noaa.gov/gcos_wgsp/Timeseries/Nino34/), covering the period of 1870-2021 CE. To eliminate the warming trend in the Niño 3.4 region, a centered 30-year base period is adopted, with updates made every 5 years, following the methodology61. The annual mean of the Niño 3.4 SST anomalies (1870–2011 CE) is employed as an interannual index of ENSO observations in this study.

The variation in reconstructed ENSO records is influenced by the choice of proxy records, particularly when relying on a single paleoclimate index. To address this issue, previous study conducted a systematic reanalysis and evaluation of twenty-one ENSO series from the past millennium62. In a separate study, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to perform an integrated reconstruction of ENSO using ten existing reconstructed sequences, with time ranging from 1650 CE to 1977 CE63. The reconstructed sequence63 was compared to the measured data, and the anomaly correlation coefficient and mean squared skill score were 0.82, 0.6 (1870–1977 CE), respectively62. This particular reconstruction sequence demonstrated the highest level of accuracy among all known reconstruction sequences. Therefore, in this study, the reconstructed sequence63 is selected as an indicator of the ENSO index for the period of 1650-1869 CE.

Multitaper method

We employed the multitaper method (MTM)29 in conjunction with the robust red noise test64 to analyze the spectral properties of the δ18O depth series of the QT ice core. MTM is a multi-window analysis and signal reconstruction method that can provide a more accurate estimation of Power Spectral Density (PSD) and subsequently calculate the estimated power spectrum value. This method has been used to determine the frequency in Vostok ice core δ18O record in Antarctic65,66, and to evaluate the Dansgaard-Oeschger (DO) climate oscillations during the last glacial period using δ18O records from three polar ice cores and a midlatitude deep-sea core in the North Atlantic Ocean67. MTM employed a set of K orthogonal tapers to obtain K independent estimates of the PSD, which are designed to minimize the spectral leakage outside a scaled bandwidth NW (W represents frequency bandwidth) due to the finiteness (N) of the data. Ordering the Slepian sequences according to their corresponding eigenvalues in decreasing order, the first K ≤ 2NW-1 eigensequences exhibit eigenvalues close to 168. Here, we opted for a conservative set of NW = 2 and K = 3 tapers for the analysis.

The depth-age relationship is nonlinear due to variable ice thinning with depth, and the ice core sampling methods may attenuate the high-frequency signal to the lower part of the ice core. Therefore, we solely examine the upper 50 m of the ice core in this paper to mitigate these potential influences. We divide the 50 m of the QT ice core δ18O depth series into five sections (D1-D5 intervals), each spanning 10 m in depth. Then we conduct a separate analysis of the δ18O depth series for each of these five sections in Section “Ice core drilling site and sample measurement”.

Variational mode decomposition

The variational mode decomposition (VMD)36, a signal decomposition method based on the variational decibels Bayesian theory, which can decompose and process non-stationary signals. In this study, VMD is employed to decompose the δ18O depth series of the QT ice core and extract the significant signals.

The VMD algorithm differs from empirical mode decomposition (EMD) in its treatment of intrinsic mode functions (IMFs)69. In VMD, the IMFs are redefined as elementary amplitude/frequency modulated (AM/FM) components, with the aim of decomposing the original input signal into several IMFs36. This redefinition can be summarized as follows:

Here, uk\((t)\) represents the mode component with center frequencies and limited bandwidths; The variable \(t\) denotes the time corresponding to uk(t); \({A}_{k}(t)\) denotes the instantaneous amplitude of \({u}_{k}(t)\); \({\phi }_{k}(t)\) represents the phase of \({u}_{k}(t)\).

The variational problem36 is solved to minimize the total estimated bandwidths of each mode, as expressed by:

Here, input signal f (t) is decomposed into k finite IMF modes, represented as \(\{{u}_{k}\}:=\{{u}_{1},{{u}}_{2},\ldots ,{{u}}_{k}\}\), and \(\{{\omega }_{k}\}:=\{{\omega }_{1},{\omega }_{2},\ldots ,{\omega }_{k}\}\) denotes the center frequency of each mode. \(\delta (t)\) presents the mean pulse function; \(t\) denotes the time of the series; \({\partial }_{t}\) denotes the first partial derivative of the universal function with respect to time \(t\); * is the convolution operation;

The minimization problem in Eq. (2) can be using a sequence of iterative suboptimization and Eq. (2) is transformed into:

Here, \(\lambda\) represents the Lagrangian multiple used to render the question unconstrained. The penalty coefficient \(\alpha\) determines the bandwidth of IMFs. A larger value of α will decrease the bandwidth of IMFs, resulting in loss of some of the decomposed signal. Conversely, a smaller value of α will increases the bandwidth of IMFs, where excessive bandwidth can cause modal aliasing.

The aim of getting the decomposed IMFs, that is to solve the optimized question in Eq. (3), can used the alternate direction method of multipliers (ADMM) is used to update \({u}_{k}^{n+1}\), \({\omega }_{k}^{n+1}\) and \({\lambda }^{n+1}\) to settle the saddle point36, which can write as follows:

where the\(\hat{f}(\omega )\), \({\hat{u}}_{k}(\omega )\) and \(\hat{\lambda \,}(\omega )\) denote the Fourier transform of \(f(t)\), \({u}_{k}(t)\) and \(\lambda (t)\) respectively. \(n\) denotes the iterations.

Repeat Eq. (4) through Eq. (6) until the update conditions are met with:

where \(\varepsilon\) is the discriminatory.

Finally, the original signal \(f(t)\) is decomposed into \(k\) modes as follows:

In the VMD process, selecting a small value of k may filter out important information from the original signal, thereby affecting the accuracy of subsequent predictions. Conversely, if the selected k value is too large, the center frequencies of adjacent IMFs may be too close, leading to duplicate IMFs or increased noise. Therefore, it is necessary to observe the distribution of center frequencies of IMFs under different quantities and then select the appropriate k value70.

Data availability

The ice core δ18O measurement and dating data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The source codes for the variational mode decomposition in the present study are standard and publicly available in the MATLAB.

References

Porter, S. E., Mosley-Thompson, E., Thompson, L. G. & Wilson, A. B. Reconstructing an Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation index from a Pacific basin–wide collection of ice core records. J. Clim. 34, 3839–3852 (2021).

Shao, L. et al. Driver of the interannual variations of isotope in ice core from the middle of Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Res. 188, 48–54 (2017).

Jones, T. R. et al. Southern Hemisphere climate variability forced by Northern Hemisphere ice-sheet topography. Nature 554, 351–355 (2018).

Seierstad, I. K. et al. Consistently dated records from the Greenland GRIP, GISP2 and NGRIP ice cores for the past 104 ka reveal regional millennial-scale δ18O gradients with possible Heinrich event imprint. Quat. Sci. Rev. 106, 29–46 (2014).

Pang, H. et al. Temperature trends in the Northwestern Tibetan Plateau constrained by ice core water isotopes over the past 7,000 years. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 125, e2020JD032560 (2020).

Thompson, L. G. et al. A high-resolution millennial record of the South Asian monsoon from Himalayan ice cores. Science 289, 1916–1919 (2000).

Cai, Z., Tian, L. & Bowen, G. J. Influence of recent climate shifts on the relationship between ENSO and Asian monsoon precipitation oxygen isotope ratios. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 124, 7825–7835 (2019).

Kurita, N. Water isotopic variability in response to mesoscale convective system over the tropical ocean. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 118, 10,376–310,390 (2013).

Xie, S.-P. et al. Decadal shift in El Niño influences on Indo–Western Pacific and East Asian climate in the 1970s. J. Clim. 23, 3352–3368 (2010).

Cai, Z., Tian, L. & Bowen, G. J. ENSO variability reflected in precipitation oxygen isotopes across the Asian Summer Monsoon region. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 475, 25–33 (2017).

Gao, J., He, Y., Masson-Delmotte, V. & Yao, T. ENSO effects on annual variations of summer precipitation stable isotopes in Lhasa, Southern Tibetan Plateau. J. Clim. 31, 1173–1182 (2018).

Vuille, M., Werner, M., Bradley, R. S. & Keimig, F. Stable isotopes in precipitation in the Asian monsoon region. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D23108 (2005).

Joswiak, D. R., Yao, T., Wu, G., Tian, L. & Xu, B. Ice-core evidence of westerly and monsoon moisture contributions in the central Tibetan Plateau. J. Glaciol. 59, 56–66 (2013).

Yang, X., Yao, T., Deji, Zhao, H. & Xu, B. Possible ENSO influences on the Northwestern Tibetan Plateau revealed by annually resolved ice core records. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 123, 3857–3870 (2018).

Hou, S. On the chronology of Tibetan ice cores. Sci. Bull. 67, 2139–2141 (2022).

Joswiak, D. R., Yao, T., Wu, G., Xu, B. & Zheng, W. A 70-yr record of oxygen-18 variability in an ice core from the Tanggula Mountains, central Tibetan Plateau. Clim 6, 219–227 (2010).

Kehrwald, N. M. et al. Mass loss on Himalayan glacier endangers water resources. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L22503 (2008).

Hou, S. et al. Age ranges of the Tibetan ice cores with emphasis on the Chongce ice cores, western Kunlun Mountains. Cryosphere 12, 2341–2348 (2018).

Ritterbusch, F. et al. A Tibetan ice core covering the past 1,300 years radiometrically dated with 39Ar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2200835119 (2022).

Tian, L. et al. 81Kr dating at the Guliya ice cap, Tibetan Plateau. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6636–6643 (2019).

Hu, H. et al. δ18O of O2 in a Tibetan ice core constrains its chronology to the Holocene. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098368 (2022).

Thompson, L. G. et al. Use of δ18Oatm in dating a Tibetan ice core record of Holocene/Late Glacial climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2205545119 (2022).

Hou, S. et al. Apparent discrepancy of Tibetan ice core δ18O records may be attributed to misinterpretation of chronology. Cryosphere 13, 1743–1752 (2019).

Hou, S. et al. Brief communication: new evidence further constraining Tibetan ice core chronologies to the Holocene. Cryosphere 15, 2109–2114 (2021).

Driscoll, R. et al. ENSO reconstructions over the past 60 ka using giant clams (Tridacna sp.) from Papua New Guinea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6819–6825 (2014).

Grothe, P. R. et al. Enhanced El Niño–Southern oscillation variability in recent decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, e2019GL083906 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Recent enhancement of central Pacific El Nino variability relative to last eight centuries. Nat. Commun. 8, 15386 (2017).

Sun, Z., Yang, Y., Zhao, J., Tian, N. & Feng, X. Potential ENSO effects on the oxygen isotope composition of modern speleothems: Observations from Jiguan Cave, central China. J. Hydrol. 566, 164–174 (2018).

Thomson, D. J. Spectrum estimation and harmonic analysis. Proc. IEEE 70, 1055–1096 (1982).

Yang, H., Johnson, K. R., Griffiths, M. L. & Yoshimura, K. Interannual controls on oxygen isotope variability in Asian monsoon precipitation and implications for paleoclimate reconstructions. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 121, 8410–8428 (2016).

Zhao, K. et al. Contribution of ENSO variability to the East Asian summer monsoon in the late Holocene. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 449, 510–519 (2016).

Li, T. & Zhang, Y. Processes that determine the quasi-biennial and lower-frequency variability of the South Asian monsoon. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 80, 1149–1163 (2002).

Zhao, N. et al. A 23.7-year long daily growth rate record of a modern giant clam shell from South China Sea and its potential in high-resolution paleoclimate reconstruction. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 583, 110682 (2021).

Li, C., Pan, J. & Que, Z. Variation of the East Asian monsoon and the tropospheric biennial oscillation. Chin. Sci. Bull. 56, 70–75 (2011).

Konda, G. et al. Tropospheric biennial oscillation and South Asian summer monsoon rainfall in a coupled model. J. Earth. Syst. Sci. 127, 1–13 (2018).

Dragomiretskiy, K. & Zosso, D. Variational mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 62, 531–544 (2014).

Shao, L. et al. Dating of an alpine ice core from the interior of the Tibetan Plateau. Quat. Int. 544, 88–95 (2020).

Folland, C. K. Relative influences of the interdecadal Pacific oscillation and ENSO on the South Pacific convergence zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 1643 (2002).

Mantua, N. J., Hare, S. R., Zhang, Y., Wallace, J. M. & Francis, R. C. A Pacific interdecadal climate oscillation with impacts on salmon production. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 78, 1069–1080 (1997).

Newman, M. et al. The Pacific decadal oscillation, revisited. J. Clim. 29, 4399–4427 (2016).

Parker, D. et al. Decadal to multidecadal variability and the climate change background. J. Geophys. Res. 112, D18115 (2007).

Wang, C., Tian, L., Shao, L. & Li, Y. Glaciochemical records for the past century from the Qiangtang Glacier No.1 ice core on the central Tibetan Plateau: Likely proxies for climate and atmospheric circulations. Atmos. Environ. 197, 66–76 (2019).

Wang, N. et al. Influence of variations in NAO and SO on air temperature over the northern Tibetan Plateau as recorded by δ18O in the Malan ice core. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 2167 (2003).

Yao, T. et al. A review of climatic controls on δ18O in precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau: Observations and simulations. Rev. Geophys. 51, 525–548 (2013).

Saenko, O. A. Influence of global warming on baroclinic Rossby radius in the Ocean: a model intercomparison. J. Clim. 19, 1354–1360 (2006).

Fang, C., Wu, L. & Zhang, X. The impact of global warming on the Pacific decadal oscillation and the possible mechanism. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 31, 118–130 (2013).

Biondi, F., Gershunov, A. & Cayan, D. R. North Pacific decadal climate variability since 1661. J. Clim. 14, 5–10 (2001).

D’Arrigo, R., Villalba, R. & Wiles, G. Tree-ring estimates of Pacific decadal climate variability. Clim. Dyn. 18, 219–224 (2001).

Shen, C., Wang, W.-C., Gong, W. & Hao, Z. A Pacific decadal oscillation record since 1470 AD reconstructed from proxy data of summer rainfall over Eastern China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L03702 (2006).

Mantua, N. J. & Hare, S. R. The Pacific decadal oscillation. J. Oceanogr. 58, 35–44 (2002).

Wang, S., Huang, J., He, Y. & Guan, Y. Combined effects of the pacific decadal oscillation and El Niño-Southern Oscillation on global land dry–wet changes. Sci. Rep. 4, 6651 (2014).

Lin, R., Zheng, F. & Dong, X. ENSO frequency asymmetry and the Pacific decadal oscillation in observations and 19 CMIP5 models. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 35, 495–506 (2018).

Steiger, N. J., Smerdon, J. E., Cook, E. R. & Cook, B. I. A reconstruction of global hydroclimate and dynamical variables over the Common Era. Sci. Data 5, 180086 (2018).

Perkins, W. A. & Hakim, G. J. Coupled atmosphere–Ocean reconstruction of the last millennium using online data assimilation. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA003959 (2021).

Emile-Geay, J., Cobb, K. M., Mann, M. E. & Wittenberg, A. T. Estimating central equatorial Pacific SST variability over the past Millennium. Part II: reconstructions and implications. J. Clim. 26, 2329–2352 (2013).

Mann, M. E. et al. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval climate anomaly. Science 326, 1256–1260 (2009).

Power, S. B. & Smith, I. N. Weakening of the Walker circulation and apparent dominance of El Niño both reach record levels, but has ENSO really changed? Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L18702 (2007).

Cai, Z. & Tian, L. Processes governing water vapor isotope composition in the Indo-Pacific region: convection and water vapor transport. J. Clim. 29, 8535–8546 (2016).

Tian, L., Masson-Delmotte, V., Stievenard, M., Yao, T. & Jouzel, J. Tibetan Plateau summer monsoon northward extent revealed by measurements of water stable isotopes. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 28081–28088 (2001).

Li, S., Yao, T., Yang, W., Yu, W. & Zhu, M. Glacier energy and mass balance in the inland Tibetan Plateau: seasonal and interannual variability in relation to atmospheric changes. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 123, 6390–6409 (2018).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4407 (2003).

Xue, H., Shi, F., LIU, W., Wang, J. & Yang, B. Reanalysis of the ENSO reconstructions over the past millennium. Quat. Sci. 41, 474–485 (2021).

McGregor, S., Timmermann, A. & Timm, O. A unified proxy for ENSO and PDO variability since 1650. Clim. Past 6, 1–17 (2010).

Mann, M. E. & Lees, J. M. Robust estimation of background noise and signal detection in climatic time series. Clim. Change 33, 409–445 (1996).

Delmotte, M. et al. Atmospheric methane during the last four glacial‐interglacial cycles: Rapid changes and their link with Antarctic temperature. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D12104 (2004).

Yiou, P., Vimeux, F. & Jouzel, J. Ice‐age variability from the Vostok deuterium and deuterium excess records. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 31875–31884 (2001).

Hinnov, L. A., Schulz, M. & Yiou, P. Interhemispheric space–time attributes of the Dansgaard–Oeschger oscillations between 100 and 0ka. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 1213–1228 (2002).

Slepian, D. Prolate spheroidal wave functions, Fourier analysis, and uncertainty V: The discrete case. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 57, 1371–1430 (1978).

Huang, N. E. et al. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A-Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 454, 903–995 (1998).

Shen, Y., Zheng, W., Yin, W., Xu, A. & Zhu, H. Feature extraction algorithm using a correlation coefficient combined with the VMD and its application to the GPS and GRACE. IEEE Access 9, 17507–17519 (2021).

Yiou, P., Baert, E. & Loutre, M. F. Spectral analysis of climate data. Surv. Geophys. 17, 619–663 (1996).

Li, M., Hinnov, L. & Kump, L. Acycle: time-series analysis software for paleoclimate research and education. Comput. GeoSci. 127, 12–22 (2019).

Henley, B. J. et al. A Tripole Index for the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 45, 3077–3090 (2015).

Tardif, R. et al. Last Millennium Reanalysis with an expanded proxy database and seasonal proxy modeling. Clim. Past 15, 1251–1273 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Science (XDB40000000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42371144, 42271143), and the Science and Technology Department of Yunnan Province (202201BF070001-021). We would like to thank colleagues for drilling, cutting, and measuring the ice core samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L., L.T., and Z.C. designed the project; S.L. and L.T. wrote the paper together; S.L., L.T., Z.C., D.W., and L.S. reviewed the paper; L.T. and L.S. measured the ice core data; S.L., S.W., F.L., and P.L. analyzed data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Tian, L., Cai, Z. et al. A reconstructed PDO history from an ice core isotope record on the central Tibetan Plateau. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 270 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00814-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00814-y

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced tropical cyclone precipitation variability is linked to Pacific Decadal Oscillation since the 1940s

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)