Abstract

In August 2022, unprecedented and long-lasting extreme heatwaves attacked the Northern Hemisphere, with simultaneous record-breaking surface air temperature (SAT) in Eastern Europe (EE), Southern China (SC), and Western North America (WNA). However, the underlying physical mechanisms of these concurrent heatwaves, and the extent to which they are driven by anthropogenic forcing versus internal variability remain unclear. Our analysis using the HadGEM3-A-N216 large ensemble attribution model reveals that anthropogenic forcing is responsible for approximately 50% of the heatwaves in EE and SC, and over 80% in WNA. Furthermore, an internally-generated circumglobal atmospheric wave train is identified as a key circulation factor facilitating these simultaneous heatwaves. Observations and numerical simulations indicate that extreme warm sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Barents Sea, along with extreme cold SST anomalies in the tropical central Pacific, are critical in the formation and maintenance of this atmospheric teleconnection wave train. Under future high-emission scenarios, the influence of the internally-generated atmospheric teleconnection on concurrent heatwaves may be enhanced, particularly in WNA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extreme climate events, such as heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and dust storms, are of great concern to policymakers and governments due to their profound impacts on socio-economic and human health1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Recent years have seen a notable increase in the frequency and severity of heatwave events in the Northern Hemisphere9,10,11,12, exacerbated by global warming, particularly those affecting multiple regions simultaneously (referred to as concurrent heatwaves)13. With the increasing interdependence of economic chains and market globalization, production failures in one location can severely impact other regions14. Consequently, extreme heatwaves occurring at the same time in multiple regions can often result in more severe impacts than isolated heatwave events15,16,17,18. For example, the simultaneous heatwaves of summer 2018 across Europe and Asia severely disrupted agricultural production, posing a threat to global food security19,20. Therefore, attributing and analyzing the mechanisms of concurrent heatwaves in the Northern Hemisphere are extremely urgent and necessary.

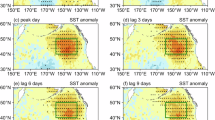

In August 2022, the Northern Hemisphere endured frequent heatwaves once again, with record-breaking extreme heatwave events occurring simultaneously in Eastern Europe (EE), Southern China (SC), and Western North America (WNA) (Fig. 1a). SC witnessed the most intense heatwave since comprehensive meteorological records began in 196121. Meanwhile, that month was recorded as the hottest August in recent decades for both EE and WNA22,23 (Fig. 1b). These observations raise a natural question: what factors led to the simultaneous occurrence of heatwaves in these three regions of the Northern Hemisphere in August 2022? Anthropogenic warming has been shown to drive recent unprecedented heatwaves and summer extremes in the Northern Hemisphere24. For instance, night-time heatwaves like the event of summer 2018 in Northeast China have become about a one-in-60-year event, down from about a one-in-500-year, due to human activities25. In addition, internal variability also plays a crucial role in regional climate change and extreme events26,27. Therefore, the next question is: what are the respective contributions of external forcing and internal variability to these concurrent heatwaves in the Northern Hemisphere?

a SAT (shading, K) and HGT500 (contours, 10 gpm interval) anomalies in August of 2022. b Time series of the area-averaged August SAT anomalies over EE, SC and WNA. The boxes in (a) denote the regions of EE, SC and WNA, and the values below boxes indicate the area-averaged SAT anomalies in these regions.

Therefore, in this study, based on observation data and 525-member simulations with and without anthropogenic forcing in the HadGEM3-A-N216 model (see Methods), we quantify the relative contributions of external forcing and internal variability to these concurrent heatwaves. Furthermore, using the“dynamical adjustment” and“circulation projection” methods (see Methods), we elucidate the key atmospheric circulation factors that led to the occurrence of these concurrent heatwaves. Additionally, we investigate how similar atmospheric circulation might influence future heatwaves under high-emission scenarios. Our research provides new scientific insights into the attribution and prediction of extreme concurrent heatwaves and offers a scientific foundation for risk assessment and policy-making in the face of ongoing global warming.

Results

Observed 2022 concurrent heatwaves

In August 2022, widespread extreme high temperature anomalies were simultaneously observed across multiple regions of the Northern Hemisphere, including EE, SC and WNA, accompanied by significant positive geopotential height anomalies at 500hPa (HGT500) (Fig. 1a). Surface air temperature (SAT) anomalies in EE exceeded those in SC and WNA, generally surpassing the 1981–2010 mean by 3 K. To assess the extremity of these heatwaves, we calculate the area-averaged August SAT anomalies over EE (45°–70°N, 30°–60°E), SC (25°–38°N, 100°–120°E) and WNA (40°–62°N, 130°–100°W) from 1960 to 2022, respectively. The 2022 anomalies in these regions are the highest recorded since at least 1960 (Fig. 1b), indicating the unprecedented severity of these heatwaves compared to historical records for the same period.

Attribution analysis of the 2022 concurrent heatwaves

Based on the HadGEM3-A-N216 model data, which provide two sets of 525-member ensembles of simulations for 2022 with and without anthropogenic influence (see Methods), we calculate the probability density function (PDF) distributions of August 2022 temperatures for these three regions, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). Since the observed heatwave events lie at the far warm-end tail of the PDFs with only natural forcing, such extreme events like those in 2022 are unlikely to occur purely due to internal climate variability, especially in EE and SC (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the probability density functions (PDFs) of SAT anomalies shift toward warmer conditions due to human activities (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that anthropogenic forcing can significantly increase the probability of heatwave events like those in August 2022.

To further quantify the contributions of external forcing and internal variability to these concurrent heatwaves, we employ the ensemble mean method for the HadGEM3-A-N216 attribution data (see Methods). The forced SAT anomalies exhibit a pervasive warming pattern, accompanied by pronounced positive HGT500 anomalies (Fig. 2a), notably in WNA, aligning with previous studies28,29. This may be attributed to the increase in temperature, causing the inflation of the air column and the rise of the isobaric surface, resulting in a positive geopotential height anomaly in the middle and upper troposphere. The forced SAT anomalies can be further divided into components from natural and anthropogenic forcing. Natural forcing, potentially influenced by the early 2022 Tonga volcanic eruption, induces slight cooling across all regions (Fig. 2c), whereas anthropogenic forcing intensifies warming, accounting for approximately 48% of the heatwave anomalies in EE, 54% in SC, and 87% in WNA (Fig. 2e, Table 1). These results suggest that the heatwaves in WNA are more sensitive to external forcing than those in other regions.

The SAT (shading, K) and HGT500 (contours, 10 gpm interval) anomalies in August 2022 for (a) forced component, b internal component and d internal dynamical component. The SAT (shading, K) anomalies in August 2022 for (c) natural forced component, e anthropogenic forced component and f internal thermodynamical component. The boxes in (a–f) represent EE, SC and WNA, and the values below boxes indicate the area-averaged SAT anomalies in these regions.

Regarding the internal variability (Fig. 2b), the spatial distributions of HGT500 and SAT anomalies are similar to the observed data (Fig. 1a), albeit with subdued SAT anomalies in these three regions. Employing the dynamical adjustment method, the internal variability contributions are further disaggregated into dynamical and thermodynamical components (see Methods). From the distribution of the anomalous internal circulation field in August 2022 (Fig. 2d), it is evident that EE, SC, and WNA are under the control of anomalous anticyclonic circulations. Such circulation is favorable to subsidence motion, which reduces cloud cover, increases solar shortwave radiation reaching the ground, thereby elevating temperatures11,30,31. The contributions of the internal circulation to the SAT anomalies reach 2.32 K (64%) in EE, 0.98 K (40%) in SC and 1.17 K (56%) in WNA (Fig. 2d, Table 1), underscoring the critical role of internally-generated anticyclones in these concurrent heatwaves. Furthermore, the impact of internal thermodynamical processes is also significant, especially in SC32, where it contributes an additional 0.41 K (Fig. 2f). However, these processes exhibit negative contributions in both EE and WNA, contributing −0.21 K and −0.88 K, respectively, likely due to different soil moisture anomalies observed earlier in these regions (Supplementary Fig. 2). The feedback between soil moisture and SAT has been highlighted as a key thermodynamical process amplifying or weakening the heatwaves33,34,35, as dry (wet) soil not only reduces (increases) the evaporative cooling effect, but also reduces (increases) the evaporation of water vapor into the atmosphere, which suppresses (favors) cloud formation and increases (reduces) downward solar shortwave radiation2.

Physical mechanism of the concurrent heatwaves

To discern whether the concurrent heatwaves in EE, SC and WNA in August 2022 are coincidental, we calculate the correlation coefficients among the historical August SAT time series across the three regions. The correlation coefficients between EE and SC, SC and WNA, and EE and WNA are 0.52, 0.37, and 0.44, respectively. After detrending to remove linear trends, these coefficients adjust to 0.43, 0.27, and 0.37, respectively. All coefficients pass the 95% significance level, suggesting a significant relationship among these heatwaves. What factors contribute to the connection of heatwaves across these three regions? Atmospheric teleconnections are often regarded as a key circulation factor leading to concurrent heatwaves20,30,36,37,38,39,40. In August 2022, there appears to be a circumglobal atmospheric teleconnection wave train generated by the internal climate system in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 2d). Therefore, we hypothesize that this teleconnection wave train may be the reason for the significant linkage of heatwaves across these three regions. To verify this hypothesis, here we apply the circulation projection method to explore the possible source of this anomalous atmospheric teleconnection based on long-term observations (see Methods). We assume that the external forcing can be estimated as a linear trend, so the observed internal data are obtained by detrending all variables in the subsequent discussion. We project the internal HGT500 anomalies (0°–90°N, 0–360°) of August 2022 onto the internal HGT500 during 1960–2022 to obtain a circulation projection index (CPI) indicative of a 2022-like internal circulation pattern (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Further regression of CPI on internal HGT250 and WAF250 from 1960 to 2022 confirms the presence of a circumglobal atmospheric teleconnection in the Northern Hemisphere (Supplementary Fig. 2b). In addition, the regression of CPI on internal SAT from 1960 to 2022 reveals that increases in CPI are associated with widespread rises in SAT across these three regions (Supplementary Fig. 2c), affirming the critical role of this teleconnection in the observed heatwaves.

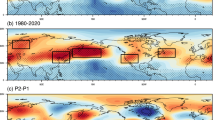

Moreover, previous studies have shown that atmospheric teleconnections are closely related to remote sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies41,42. So, what role does the anomalous SST play in the 2022-like internal circulation? Notably, significant warm SST anomalies are present in the Barents Sea, North Pacific, and North Atlantic, along with cold SST anomalies in the Central Pacific, in both July and August, accompanied by the increase of CPI (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 4a). Barents Sea SST anomalies may influence the position and strength of Ural blocking, leading to heatwaves over Russia43. Warm SST anomalies in the North Pacific are conducive to an increased temperature gradient and higher wind speeds on the northern side of the area, and a decreased temperature gradient and lower wind speeds on the southern side, facilitating the maintenance of anticyclones over the North Pacific. Mid-North Atlantic SST anomalies can trigger extreme heatwaves over SC via a teleconnection wave train44. Cold SST anomalies in the Central Pacific can significantly strengthen the Western North Pacific Subtropical High (WNPSH) via westward emanations of descending Rossby waves45. Therefore, SST anomalies in these key oceanic regions may significantly impact this circumglobal atmospheric teleconnection in August 2022. Here we define ocean indexes for the Barents Sea (BSSST), North Pacific (NPSST), North Atlantic (NASST) and Central Pacific (CPSST), respectively (see Methods). In August 2022, internal SST anomalies in the Central Pacific and North Atlantic reached historical extremes, while those in the North Pacific were the second highest on record, and those in the Barents Sea were the fifth highest in history (Supplementary Figs. 4b, 5).

a Anomalies for internal SST (shading, K) obtained by regression upon normalized circulation projection index (CPI). Anomalies for (b) internal HGT250 (shading, gpm) and WAF250, and c internal SAT (shading, K) obtained by regression upon normalized ocean index (OI). The black boxes in (a) are the regions to define the BSSST, NPSST, NASST and CPSST. The boxes in (b, c) denote the regions of EE, SC and WNA. Stippling regions indicate the significance at the 90% confidence level.

Here a comprehensive ocean index (OI) is defined to encapsulate these anomalies (see Methods), revealing a significant correlation (0.54) with CPI from 1960 to 2022, exceeding the 99% confidence level. Further regression of internal HGT250, wave activity flux at 250 hPa (WAF250), and SAT anomalies onto the standardized OI demonstrate a distinct wave train extending from EE to SC, amplifying over the North Pacific, and propagating to WNA, thus inducing anomalous anticyclone and widespread SAT warming in EE, SC, and WNA (Fig. 3b, c). Moreover, regression of internal SST anomalies against the area-averaged internal SAT anomalies over EE, SC, and WNA also shows significant SST anomalies in all key oceanic areas (Supplementary Fig. 6). To confirm the influence of SST anomalies on atmospheric teleconnection, a numerical experiment is conducted with the ECHAM5 model (see Methods). In response to the SST anomalies, an atmospheric teleconnection wave train extends from Eurasian continent to North America, leading to anticyclones over EE, SC and WNA (Supplementary Fig. 7). These results demonstrate the substantial role of SST anomalies in these key marine areas in the formation and maintenance of the circumglobal teleconnection, pivotal in the occurrence of heatwaves in EE, SC, and WNA.

The impact of 2022-like internal circulation on future concurrent heatwaves

Under high-emission scenarios, it is projected that the frequency and intensity of extreme heatwaves in the Northern Hemisphere will significantly increase46,47,48. It is natural to ask whether the role of 2022-like internal circulation in concurrent heatwaves will change in the future. To explore this, we apply the circulation projection method to historical and future Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5 scenarios of the MPI-ESM (see Methods). Initially, we obtain the internal HGT500 and SAT for each member of the MPI-ESM using the ensemble mean method (see Methods). Subsequently, similar to the observations, the circulation projection index (CPI) from 1960 to 2099 is computed by projecting the 2022 internal HGT500 anomalies (0°–90°N, 0–360°) across each ensemble member of the MPI-ESM. Finally, we regress the internal SAT anomalies against the normalized CPI for the periods 1960–2005 and 2054–2099, respectively. Although no discernible trend is observed in the 2022-like internal circulation index (CPI) within the ensemble mean (Fig. 4a), future projections show a more pronounced warming in internal SAT for EE, SC, and WNA, with the most notable increase in WNA (Fig. 4b, c), which may be related to the high sensitivity to external forcing, as previously illustrated (Fig. 2a, e). These results indicate that under high-emission scenarios, external forcing may amplify the influence of internal circulation on the occurrence of concurrent heatwaves. This is similar to a previous study that found under the influence of future climate change, similar atmospheric circulations will lead to greater warming in North America than the global average temperature increase49.

a Ensemble means of circulation projection index (CPI) for 100 MPI-ESM members from 1960 to 2099. b Ensemble means of internal SAT (shading, K) anomalies regress upon normalized CPI for 100 MPI-ESM members for the period 1960 to 2005. c as in b, but for the period 2054 to 2099. The boxes in these figures denote the regions of EE, SC and WNA. Stippling regions indicate the significance at the 90% confidence level.

Discussion

In August 2022, record-breaking extreme heatwaves simultaneously affected multiple regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Based on the ERA5 dataset and HadGEM3-A-N216 large ensemble attribution model, we find that these extreme heatwave events are significantly amplified due to anthropogenic forcing in EE (48%), SC (54%) and WNA (87%), but slightly mitigated by natural forcing in EE (−7%), SC (−10%) and WNA (−6%). Furthermore, using the dynamical adjustment method, we find that the internal circulation-induced surface air temperature (SAT) anomalies are dominant in all three regions, contributing 2.42 K, 0.99 K and 1.33 K SAT anomalies in EE, SC and WNA, respectively. The role of internal thermodynamic processes, particularly the soil moisture-SAT feedback, is also significant, affecting the intensity of the heatwaves by altering evaporative cooling and sensible heat flux. Our findings also underscore that the concurrent of these heatwaves can be attributed to a circumglobal atmospheric teleconnection wave train, facilitated by SST anomalies in the Barents Sea, North Pacific, North Atlantic, and Central Pacific. Looking forward under high-emission scenarios, external forcing is projected to amplify the role of internal circulation in exacerbating concurrent heatwaves, especially in WNA.

To understand the atmospheric conditions that may lead to concurrent heatwaves similar to those observed in 2022, we analyzed the temperature and circulation fields for the years identified as having similar patterns, specifically 1967 and 1972 (Supplementary Fig. 8). The results show that in these years, EE, SC, and WNA also experienced warm temperature anomalies along with positive geopotential height anomalies, resembling the patterns observed in 2022. Additionally, there is evidence of a circumglobal atmospheric teleconnection wave train across the Northern Hemisphere during these years, suggesting that similar circulation patterns could have contributed to the concurrent heatwaves.

In our attribution analysis, we primarily employ the HadGEM3-A-N216 large ensemble attribution model. Although the HadGEM3-A-N216 model is widely used in attribution studies of extreme climate events24,25,50,51, we acknowledge that using one model may make our conclusions rely on this model’s performance. Therefore, to enhance robustness, comparing outcomes from more attribution models is encouraged. In the analysis of quantifying the contribution of atmospheric circulation, we use the dynamical adjustment method, which avoids some limitations of prior studies. Specifically, we perform adjustments across 525 ensemble members of the HadGEM3-A-N216 model, effectively circumventing the problem of limited observational samples. Additionally, we select August monthly average data rather than consecutive daily data in a month from each member, thus mitigating the issue of samples dependence, where data from one day may be influenced by the preceding days due to the persistence of atmospheric circulation.

In the section of future influence, due to the effectiveness of the MPI-ESM model in simulating Northern Hemisphere climate change52,53, we present the results using this model. We also utilize the MRICO6 large ensemble model54, but this model exhibits poor performance in historical simulations and fails to reproduce these concurrent heatwaves. In the future, we should attempt to compare results from more large ensemble models.

Finally, it should be noted that external forcing not only significantly amplifies concurrent heatwaves in the Northern Hemisphere directly, but also may intensify these events in the future by affecting the internal circulation and accelerating the drying of soil moisture55. Therefore, without significant mitigation of emissions, the Northern Hemisphere may suffer more extreme and frequent concurrent heatwaves.

Methods

Observations

Monthly mean zonal and meridional winds (U, V), geopotential height (HGT), and surface air temperature (SAT) are obtained from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ERA5)56 with a horizontal resolution of 1.0° × 1.0°. Soil moisture data at 0–28 cm with a 1.0° × 1.0° global grid is obtained from the ERA5-Land dataset57. The sea surface temperature (SST) data at a 2.0° × 2.0° global grid is taken from the NOAA Extended Reconstructed SST (ERSST), version 5 dataset58. For all datasets, anomalies of all variables were calculated based on the climatological mean of 1981–2010.

Model simulations

The outputs of the HadGEM3-A-N216 atmosphere model with a horizontal resolution of 0.56° × 0.83° are used in this study59, which include four groups of experiments. The first two groups consist of 15-member ensembles of simulations from 1960 to 2013: one set (Historical) is driven by observed sea surface temperatures (SST) and sea ice concentrations (SIC) from the HadISST dataset along with historical anthropogenic atmospheric forcing. The other set (HistoricalNat) is driven by SST and SIC with the anthropogenic influence removed and preindustrial atmospheric forcing fields applied. The latter two groups are 525-member ensembles of simulations for 2022: one (HistoricalExt) is driven under the same conditions as “Historical” but specific to 2022, and the other (HistoricalNatExt) is driven under the same conditions as “HistoricalNat” but also specific to 2022, representing a counterfactual scenario without anthropogenic influence.

To assess the contribution of future atmospheric circulation to concurrent heatwaves, the outputs of historical and representative concentration pathway (RCP) 8.5 simulations in 100-member ensemble simulations with Max Planck-Institute Earth System Model (MPI-ESM) are also employed in this study60. Each ensemble member in MPI-ESM is subjected to the same radiative forcing (historical for 1850–2005 and RCP 8.5 emissions scenario for 2006–2099) but starts from slightly different initial conditions.

For better comparison, all the model data are linearly interpolated to the same resolution as observations, and the climatology of the model data is calculated by the ensemble mean of the historical simulation.

We also employ the atmospheric general circulation model ECHAM, version 5 (ECHAM5) to verify the influence of internal SST anomalies on the atmospheric circulation. The ECHAM5 model is developed by the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Meteorology61. The resolution of the ECHAM5 model is spectral triangular 63 (T63) and 19 vertical levels in a sigma pressure coordinate system. A 30-member ensemble experiment is forced by the observed SST anomalies over the Barents Sea, North Pacific, North Atlantic and Central Pacific imposed on the climatological SST. The imposed SST anomalies in this experiment are amplified by a factor of two to enhance the atmospheric response at mid- and high latitudes. Each ensemble member starts from different atmospheric initial conditions to account for internal variability, and the magnitude of the disturbance posed on the ensemble members helps to explore the robustness of the atmospheric response. The results presented are the averages of these 30 ensemble members, which helps to minimize the influence of random internal variability.

Ensemble mean method

Large model ensemble mean is an effective approach to separate the roles of internal variability and external forcing28,29,62. In this study, we average the HadGEM3-A-N216 model’s 525 HistoricalExt members’ anomalies to derive the forced components, and the internal components are obtained by subtracting the forced components from the observations and individual ensembles. The natural forced components are derived from the average of 525 HistoricalNatExt members’ anomalies. Then, the anthropogenic forced induced anomalies are obtained by removing the natural forced components from the forced components. Similarly, the internal components of the 100 members in the MPI-ESM in historical and future scenario are obtained by subtracting the mean of the 100 members from individual ensembles.

Dynamical adjustment method

The dynamical adjustment method is an effective technique to quantify the role of atmospheric circulation on long-term temperature trends52,63,64,65 and extreme events49,66. In this study, the main purpose of this method is to further separate the roles of internal circulation and internal thermodynamic in these concurrent heatwaves, and HGT500 is used to represent atmospheric circulation change. Here, we briefly summarize our algorithm. First, we need to obtain the internal HGT500 and SAT data. The external forcing signal for 2022 is derived by averaging the 525 ensemble members, and the internal data of the 525 ensembles are obtained by subtracting the external forcing from the original 525 ensembles. Then, we reconstruct internal dynamical SAT using the same weighting coefficients of the internal dynamical HGT500 field (0°–90°N, 0°–360°), which is derived from randomly selecting 300 internal HGT500 analogues from the 525 internal HGT500 ensembles to fit the internal HGT500 field. This random selection and reconstruction process is repeated 100 times to prevent overfitting. Finally, the internal thermodynamically induced SAT anomalies are obtained by removing the internal dynamical components from the internal SAT anomalies.

Circulation projection method

In this study, to explore the mechanism of atmospheric circulation anomalies associated with these concurrent heatwaves, we employ a circulation projection method to represent the similarity of atmospheric circulation between the extreme year and other years25,51. We regress the atmospheric circulation variable in each year onto that in the extreme year to obtain a circulation projection index consisting of the regression coefficients. This method allows us to analyze the temporal evolution of these variables throughout history and avoid some random signals.

Definition of ocean indexes

We also define a comprehensive ocean index (OI) to represent the ocean signal in this study (1), where BSSST, NPSST, NASST and CPSST are defined as the area-averaged SST anomalies over the Barents Sea (70°–80°N, 20°–47°E), North Pacific (35°–52°N, 158°E–178°W), North Atlantic (37°–49°N, 60°W–28°W), and Central Pacific (5°S–5°N, 165°E–172°W), respectively. The correlation coefficients between the BSSST, NPSST, NASST, CPSST and the circulation projection index (CPI) are denoted as r1, r2, r3, and r4, respectively.

Data availability

ERA5 reanalysis datasets are available from the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts [https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets]. ERSSTv5 data are from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html]. The MPI-ESM large ensemble simulations are available from the Multi-Model Large Ensemble Archive [https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/projects/community-projects/MMLEA]. The data of numerical experiment are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The data in this study are analyzed in Python (https://www.python.org/). All relevant codes used in this work are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Hu, Z. et al. Attribution of the March 2021 exceptional dust storm in North China. Bull. Am. Meteorolog. Soc. 104, E749–E755 (2023).

Ma, Y. et al. Different Characteristics and Drivers of the Extraordinary Pakistan Rainfall in July and August 2022. Remote Sensing 15, 2311 (2023).

Mora, C. et al. Global risk of deadly heat. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 501-+ (2017).

Ma, Y., Hu, Z., Meng, X., Liu, F. & Dong, W. Was the record-breaking mei-yu of 2020 enhanced by regional climate change. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 103, S76–S82 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Projecting heat-related excess mortality under climate change scenarios in China. Nat. Commun. 12, 1039 (2021).

Ma, Y. et al. Anthropogenic climate change enhances the July 2021 super-heavy rainfall event in Central China. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 104, E736–E741 (2023).

Hu, Z. et al. Was the Extended Rainy Winter 2018/19 over the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River Driven by Anthropogenic Forcing? Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 102, S67–S73 (2021).

Thompson, V. et al. The most at-risk regions in the world for high-impact heatwaves. Nature Communications 14, (2023).

Ma, Y. et al. The 2022 record-breaking high temperature in China: Sub-seasonal stepwise enhanced characteristics, possible causes and its predictability. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 14, 651–659 (2023).

Ma, Q. et al. Possible influences of spring Barents Sea ice shrinking on Chinese heat wave events. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 6101–6113 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Increased impact of heat domes on 2021-like heat extremes in North America under global warming. Nat. Commun. 14, 1690–1690 (2023).

IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., et al. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 3–32, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.001.

Rogers, C. D. W., Kornhuber, K., Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E., Loikith, P. C. & Singh, D. Sixfold Increase in Historical Northern Hemisphere Concurrent Large Heatwaves Driven by Warming and Changing Atmospheric Circulations. J. Clim. 35, 1063–1078 (2022).

Levermann, A. Make supply chains climate-smart. Nature 506, 27–29 (2014).

Zscheischler, J. et al. Future climate risk from compound events. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 469–477 (2018).

Raymond, C. et al. Understanding and managing connected extreme events. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 611–621 (2020).

Tigchelaar, M., Battisti, D. S., Naylor, R. L. & Ray, D. K. Future warming increases probability of globally synchronized maize production shocks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 6644–6649 (2018).

Ganguly, A. R. et al. Higher trends but larger uncertainty and geographic variability in 21st century temperature and heat waves. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15555–15559 (2009).

Vogel, M. M., Zscheischler, J., Wartenburger, R., Dee, D. & Seneviratne, S. I. Concurrent 2018 Hot Extremes Across Northern Hemisphere Due to Human-Induced Climate Change. Earths Future 7, 692–703 (2019).

Kornhuber, K. et al. Extreme weather events in early summer 2018 connected by a recurrent hemispheric wave-7 pattern. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 054002 (2019).

Mallapaty, S. China’s extreme weather challenges scientists trying to study it. Nature 609, 888–888 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Understanding and Attribution of Extreme Heat and Drought Events in 2022: Current Situation and Future Challenges. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1941–1951 (2023).

Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), 2022: European State of the Climate. Copernicus: Climate Change Service. [Available online at https://climate.copernicus.eu/ESOTC].

Ren, L. et al. Anthropogenic influences on the persistent night-time heat wave in summer 2018 over northeast China. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 101, S83–S87 (2020).

Gong, H. et al. Attribution of the August 2022 Extreme Heatwave in Southern China. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 105, E193–E199 (2024).

Ma, S. & Zhu, C. Extreme cold wave over east Asia in January 2016: a possible response to the larger internal atmospheric variability induced by arctic warming. J. Clim. 32, 1203–1216 (2019).

Deser, C., Phillips, A. S., Alexander, M. A. & Smoliak, B. V. Projecting North American Climate over the Next 50 Years: Uncertainty due to Internal Variability*. J. Clim. 27, 2271–2296 (2014).

Deser, C., Terray, L. & Phillips, A. S. Forced and internal components of winter air temperature trends over north America during the past 50 years: mechanisms and implications. J. Clim. 29, 2237–2258 (2016).

Gong, H. N., Wang, L., Chen, W. & Wu, R. G. Attribution of the East Asian winter temperature trends during 1979–2018: role of external forcing and internal variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10874–10881 (2019).

Xiao, H., Xu, P. & Wang, L. The unprecedented 2023 North China heatwaves and their S2S predictability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107642 (2024).

Horton, D. E. et al. Contribution of changes in atmospheric circulation patterns to extreme temperature trends. Nature 522, 465-+ (2015).

Jiang, J., Liu, Y., Mao, J. & Wu, G. Extreme heatwave over Eastern China in summer 2022: the role of three oceans and local soil moisture feedback. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 044025 (2023).

Fischer, E. M., Seneviratne, S. I., Vidale, P. L., Luethi, D. & Schaer, C. Soil moisture - Atmosphere interactions during the 2003 European summer heat wave. J. Clim. 20, 5081–5099 (2007).

Vogel, M. M. et al. Regional amplification of projected changes in extreme temperatures strongly controlled by soil moisture-temperature feedbacks. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 1511–1519 (2017).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Impact of soil moisture-climate feedbacks on CMIP5 projections: First results from the GLACE-CMIP5 experiment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5212–5217 (2013).

Coumou, D., Petoukhov, V., Rahmstorf, S., Petri, S. & Schellnhuber, H. J. Quasi-resonant circulation regimes and hemispheric synchronization of extreme weather in boreal summer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 12331–12336 (2014).

Hong, X. W., Lu, R. Y. & Li, S. L. Amplified summer warming in Europe-West Asia and Northeast Asia after the mid-1990s. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 094007 (2017).

Kornhuber, K. et al. Amplified Rossby waves enhance risk of concurrent heatwaves in major breadbasket regions. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 48 (2020).

Roethlisberger, M., Frossard, L., Bosart, L. F., Keyser, D. & Martius, O. Recurrent synoptic-scale rossby wave patterns and their effect on the persistence of cold and hot spells. J. Clim. 32, 3207–3226 (2019).

Xu, P. et al. Amplified waveguide teleconnections along the polar front jet favor summer temperature extremes over Northern Eurasia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093735 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Contribution of atmospheric circulations changes to the variations of summertime lower tropospheric ozone over East Asia during recent decades. Atmosph. Res. 292, 106852 (2023).

Iwao, K. & Takahashi, M. Interannual change in summertime precipitation over northeast Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, 16 (2006).

Wang, H. & Luo, D. Summer Russian heat waves and their links to Greenland’s ice melt and sea surface temperature anomalies over the North Atlantic and the Barents-Kara Seas. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 114048 (2020).

Sun, J. Q. Record-breaking SST over mid-North Atlantic and extreme high temperature over the Jianghuai-Jiangnan region of China in 2013. Chin. Sci. Bull. 59, 3465–3470 (2014).

Xiang, B., Wang, B., Yu, W. & Xu, S. How can anomalous western North Pacific Subtropical High intensify in late summer? Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 2349–2354 (2013).

Dong, Z., Wang, L., Xu, P., Cao, J. & Yang, R. Heatwaves similar to the unprecedented one in summer 2021 over western North America are projected to become more frequent in a warmer world. Earths Future 11, e2022EF03437 (2023).

Qian, C. et al. Rapid attribution of the record-breaking heatwave event in North China in June 2023 and future risks. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 014028 (2024).

Bartusek, S., Kornhuber, K. & Ting, M. 2021 North American heatwave amplified by climate change-driven nonlinear interactions. Nat. Clim Change. 12, 1143–1150 (2022).

Terray, L. A storyline approach to the June 2021 northwestern North American heatwave. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101640 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Attribution of april 2020 exceptional cold spell over Northeast China. Bull. Am. Meteorolog. Soc. 103, S61–S67 (2022).

Ma, K., Gong, H. & Wang, L. Attribution of the concurrent extreme heatwaves in Northern Europe and Northeast Asia in July 2018. Atmosph. Res. 107506 (2024).

Gong, H., Wang, L., Chen, W. & Wu, R. Evolution of the East Asian winter land temperature trends during 1961–2018: role of internal variability and external forcing. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 024015 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. South Asian summer monsoon projections constrained by the interdecadal Pacific oscillation. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay6546 (2020).

Shiogama, H. et al. MIROC6 Large Ensemble (MIROC6-LE): experimental design and initial analyses. Earth Syst. Dyn. Discuss. 2023, 1–28 (2023).

Qiao, L. et al. Soil moisture-atmosphere coupling accelerates global warming. Nat. Commun. 14, 4908 (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Munoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Huang, B. Y. et al. Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): Upgrades, Validations, and Intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Ciavarella, A. et al. Upgrade of the HadGEM3-A based attribution system to high resolution and a new validation framework for probabilistic event attribution. Weather Clim. Extremes 20, 9–32 (2018).

Maher, N. et al. The Max Planck Institute grand ensemble: enabling the exploration of climate system variability. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2050–2069 (2019).

Roeckner, E. et al. Sensitivity of simulated climate to horizontal and vertical resolution in the ECHAM5 atmosphere model. J. Clim. 19, 3771–3791 (2006).

Deser, C. et al. Insights from Earth system model initial-condition large ensembles and future prospects. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 277-+ (2020).

Wallace, J. M., Fu, Q., Smoliak, B. V., Lin, P. & Johanson, C. M. Simulated versus observed patterns of warming over the extratropical Northern Hemisphere continents during the cold season. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14337–14342 (2012).

Saffioti, C., Fischer, E. M., Scherrer, S. C. & Knutti, R. Reconciling observed and modeled temperature and precipitation trends over Europe by adjusting for circulation variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 8189–8198 (2016).

Smoliak, B. V., Wallace, J. M., Lin, P. & Fu, Q. Dynamical adjustment of the northern Hemisphere surface air temperature field: methodology and application to observations. J. Clim. 28, 1613–1629 (2015).

Terray, L. A dynamical adjustment perspective on extreme event attribution. Weather Clim. Dynam. 2, 971–989 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41925020, 42075033, and 42275023). We thank Dr. F. C. Lott for providing the data of HadGEM3-A-N216 attribution simulations. We thank the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for providing the ERA5-related and ERSSTv5 data, respectively. We also thank the US CLIVAR Working Group on Large Ensembles for collecting and making available the multi-model large ensemble archive.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W. designed the study. K.M. performed the data analysis. K.M., H.G. and L.W. provided the interpretation and wrote the manuscript. B.L. conducted the numerical experiments Y.L. and H.R prepared the data. W.C. helped improve the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to writing the manuscript

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, K., Gong, H., Wang, L. et al. Anthropogenic forcing intensified internally driven concurrent heatwaves in August 2022 across the Northern Hemisphere. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 290 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00828-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00828-6