Abstract

Large-scale modes of climate variability, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, North Atlantic Oscillation, and Indian Ocean Dipole, show significant regional correlations with seasonal weather conditions, and are routinely forecast by meteorological agencies attempting to anticipate seasonal precipitation patterns. Here, we use machine learning together with more traditional approaches to quantify how much precipitation variability can be explained by large-scale modes of variability, and to understand the degree to which these modes interact non-linearly. We find that the relationship between climate modes and precipitation is predominantly non-linear. In some regions and seasons climate modes can explain up to 80% of precipitation variability. However, variability explained is below 10% for more than half of the land surface, and only 1% of the land shows values above 50%. This outcome provides a clear rationale to limit expectations of predictability from modes of variability in all but a few select regions and seasons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large-scale fluctuating patterns in oceanic and atmospheric conditions in different parts of the globe can have prominent local, regional and global impacts on climate1,2,3. Where these patterns reoccur over time, they are typically described as modes of variability (MoV)4. Prominent MoV include the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), characterised by large changes in the upper ocean temperature linked to variations in the overlying winds in the tropical central and eastern Pacific Ocean5; the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), a coupled ocean-atmosphere phenomenon occurring in the equatorial Indian Ocean6; and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), characterised by differences in atmospheric pressure between the Icelandic Low and the Azores High7.

Many studies have examined the impact that MoV have on precipitation. ENSO has been linked with shifts in precipitation patterns and extreme weather events across the globe8,9,10, including droughts and floods, with wide-ranging and sometimes severe environmental, social, and economic impacts11,12,13,14. Forecasts of ENSO one to two seasons ahead have reduced ENSO-induced losses in some regions15,16, and the practice has become routine at weather centres worldwide17,18, using a range of forecasting methods which are continuously being improved19,20,21,22. ENSO-precipitation teleconnections have been explored and documented in South America23, North America24,25, Europe26, Africa27, Antarctica28, Asia (Indonesia29, India30, East Asia31, the Arabian Peninsula32), and Australia33,34,35.

Other MoV and the interplay between them and ENSO also influence extreme weather events, with impacts varying by region and season. For example, the Atlantic sea surface temperature (SST) modulates ENSO-precipitation teleconnections to South America36, Europe37, and the United States38. The IOD mediates ENSO-precipitation teleconnection to the Asian monsoon39. Australian precipitation is impacted by the interaction of IOD, ENSO, and the Southern Annular Mode (SAM)40, as well as the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO)41.

The combined effects of MoV, and associated interactions, are important in understanding the degree of predictability of precipitation40,42,43. Although the basic dynamics of MoV and their associated teleconnections are reasonably well understood44, the complexities of their interactions and their collective impact on precipitation have only been explored in relatively simple and typically linear frameworks45. While many studies have examined the relationship between precipitation and one or more MoV, they are often regionally limited, account for only a subset of MoV, fail to capture the complex non-linear interactions between MoV, and/or examine these relationships in-sample rather than within a predictability framework35,46,47,48,49,50.

Here, we use both linear and non-linear methods to capture the concurrent relationships between a range of MoV (Supplementary Fig. S1, Tables S1 and S2) and observed precipitation anomalies across land globally. Critically, these relationships are tested with data not used to establish these relationships (out-of-sample), so that we can fairly assess MoV contributions to precipitation predictability. We identify which MoV allow for the greatest precipitation predictability in different regions. We then quantify the proportion of variability explained in precipitation anomaly across different regions and seasons that MoV can provide. By doing so, we offer a concrete basis for determining the degree of precipitation predictability that we might expect MoV to offer.

Results

Variability in precipitation explained by climate modes

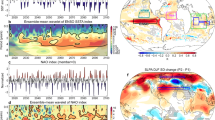

By choosing the best performing model, i.e., the set of MoV predictors and the modelling approach (linear or non-linear) that provide the best predictions of contemporaneous precipitation anomalies, we see that the total variability explained in precipitation anomaly across all seasons and years can exceed 40%, but only over 1% of the land area (Fig. 1). In the majority of the land (75% of land grid cells), it does not exceed 15%. The median variability explained across all land areas is 8.7%. If a single model were to be used for all seasons or all regions, the variability explained would decrease.

Precipitation anomalies were predicted separately for each season using the optimal model for each grid cell and combined to form a complete time series. One R² value was computed for each grid cell, and inset shows the density of R2 values across all land grid cells, along with median, 75th and 99th percentile.

Regions of high predictability from MoV include parts of the Maritime Continent, northeast and southwest Sudan, southern Ethiopia, northeast Nigeria, northern Brazil, northwest Colombia, and western Ecuador (Fig. 1). There is a notable change in predictability with latitude. Most of the more predictable regions are in the tropics, with many extratropical regions, for example across North America, northern Asia and Australia exhibiting low overall predictability.

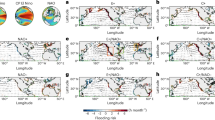

While these results imply limited utility of MoV in regions where seasonal forecasts depend heavily on them, we find that regional predictability can be considerably higher in particular seasons (Fig. 2). In every season, 1% of the land shows explained variability values above 50%. For example, Australian precipitation predictability is high during SON and reaches 60% in some areas, but is significantly lower during other seasons. A similar result is found in the Middle East. In the Maritime Continent, values exceed 80% during SON, remain high in JJA, but in many parts, shows much lower precipitation predictability in MAM. Thailand shows high precipitation predictability in MAM only. In eastern Africa, predictability peaks at 70% during SON, while parts of the Sahel are only predictable during JJA. In parts of Texas and northern Mexico, MoV explain 50% of variability in precipitation anomalies during both DJF and MAM. In northwest Russia, precipitation predictability reaches 60% during DJF. Precipitation predictability in Europe is generally low throughout the year, except in Finland, western Ukraine, and parts of Spain during DJF. In northeast Colombia, precipitation predictability is high during DJF and JJA, reaching 80%, but it falls below 20% in MAM. In northern Brazil and parts of Ecuador, climate modes explain a large proportion of variability in precipitation anomalies year-round, particularly during MAM and DJF where it exceeds 70% in some areas.

As per Fig. 1, but shown separately for each season.

Models with multiple MoV as predictors outperform those using Niño3+GMT alone. In all seasons, the 99th percentile of the explained variability increases by at least 50% when MoV predictors are included (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Additionally, The proportion of global land with predictable anomalies increases from approximately 25% using Niño3+GMT (coloured areas in Supplementary Fig. S2) to over 65% when incorporating additional MoV predictors (non-grey areas in Fig. 4). Over the remaining land area, no predictability is found (grey areas in Fig. 4). Including GMT slightly improves predictability compared to using ENSO alone, as indicated by the small increase in the magnitudes of the explained precipitation variability computed from Niño3+GMT (Supplementary Fig. S2) compared to Niño3 (Supplementary Fig. S3), while maintaining identical spatial patterns. This enhancement is likely attributed to accounting for non-stationarities during the study period when GMT is used as a predictor. Seasonal maps of optimal MoV sets are provided in Supplementary Figs. S4-S7.

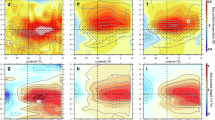

Importance of different climate modes

In many cases, seasonal differences in predictability align with changes in the strength of the teleconnection between MoV and precipitation. Supplementary Figs. S8-S11 illustrate the importance of each MoV for precipitation predictability, while in Fig. 3 we highlight four MoV/seasons with high importance scores over large regions. Together they reinforce results in many existing studies: the NAO is a key driver of precipitation predictability in Europe during DJF51,52; IOD drives the predictability of precipitation in eastern Africa during SON53,54 and enhances predictability in Australia and western Indonesia during JJA29,55,56; SAM enhances precipitation predictability in eastern Australia SON57, and ENSO provides precipitation predictability in north and southeast Australia during SON58, as well as southeast Asia during MAM59; MJO enhances predictability in parts of the maritime continent and south India during JJA60, and contributes to precipitation predictability in eastern Africa during SON, alongside IOD54,61; The Atlantic Niño enhances the predictability of precipitation in countries on the Gulf of Guinea, including Ivory Coast, Ghana, and parts of Nigeria during JJA62.

‘Very high’ implies that all 18 models including a particular MoV improve predictions compared to the baseline model using Niño3 and GMT alone, ‘High’ implies at least half of the models did this, and ‘Low’ implies less than half. White regions indicate that additional MoV do not improve predictability. Note that high predictability for a MoV in this metric need not translate to high explained variability in Figs. 1 and 2.

Here, Niño3+GMT were included in all combinations; however, locally important MoV may have more predictive power without the inclusion of ENSO, particularly for climate modes identified as highly important for each region and season (as illustrated in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. S8-S11). To explore this, we tested the predictive power of NAO alone in DJF over Europe, where NAO is known to strongly influence the climate (Fig. 3) and ENSO’s influence is weaker. We found that incorporating ENSO and GMT improves predictability in more areas than it reduces (see Supplementary Fig. S12). This indicates that even in regions where ENSO’s influence is expected to be weak, ENSO still contributes to improving predictability when combined with important regional climate modes.

Nature of relationship between climate modes and precipitation

The relationship between MoV and precipitation is complex. Depending on the season, 38% to 41% of land surface showed better predictability with the non-linear Random Forest (RF) models, 26% to 27% with the Linear Regression (LR) models, while in the remaining area (36%), no model met the minimum performance level (Fig. 4). In principle, given sufficient data, a RF model should match the skill of a LR model, where the impacts from MoV are linear, and surpass the linear model where there are non-linear interactions. At present, our sample size for training is small (40 samples per location), explaining some of the stochasticity in Fig. 4. Nevertheless, we still find that the RF model outperforms the linear model in most places suggesting that non-linear interactions are likely important in many regions.

Discussion

Our study shows that large-scale climate modes provide limited insight into precipitation predictability over all seasons. Predictability is enhanced in certain regions for particular seasons. However, for 50% of the land, less than 9% of the variability of precipitation anomalies can be explained by MoV (Fig. 1). This only rises to 10–12% when seasons are considered separately (Fig. 2), despite a select few regions and seasons reaching 80%.

These results challenge a prevalent public perception that knowledge of current MoV, especially ENSO indicators, largely dictate future precipitation (rather than this being true only for specific locations and seasons). This is underlined by the inability to provide any predictability of precipitation anomalies from Niño3 alone (including GMT) for over 75% of the land (Supplementary Fig. S2). This is even in regions where strong ENSO/precipitation correlations exist in certain seasons such as eastern Africa in DJF and SON, western North America in MAM, and parts of South America in JJA (Supplementary Fig. S13). In fact, while high correlation between Niño3 and precipitation anomalies may suggest a relationship, it does not guarantee predictability. Correlation measures the linear relationship within a given dataset (in-sample), but predictability depends on how well these relationships generalise out-of-sample. Therefore, strong in-sample correlations do not necessarily translate to high out-of-sample performance and predictability. Conversely, low correlation between Niño3 and precipitation anomalies may give a false impression of weak predictability. In the case of non-linear dynamics, it is possible to build a non-linear model that achieves high predictability by capturing interactions that (linear) correlation misses. For example, in western Ukraine and southeast Algeria, correlation between Niño3 and precipitation is low, but predictability is high, achieved by a non-linear RF model that effectively captured the complex relationships over the mountainous regions in both locations. Briefly, high correlation is neither sufficient nor always necessary for achieving high predictability. Our adoption of an out-of-sample testing framework is critical to this discovery and highlights the true ability of the MoV to explain precipitation variability. These findings reinforce previous work63 that cautioned against overstating the global impact of ENSO on precipitation, estimating that the proportion of land areas with significant ENSO-related precipitation signals in any particular season is less than 30%. There are extended regions that show substantial precipitation predictability in certain seasons. In parts of the Maritime Continent, Brazil, Columbia and Ecuador, between 70% and 80% of precipitation variability can be explained during at least one season (Fig. 1). In parts of Australia in SON, the Sahel in JJA, Europe in DJF and southeast Asia in MAM, about half of precipitation anomalies variability can be explained by a combination of MoV. In regions and seasons where MoV offer no or low predictability, expectations of future precipitation should be based on other prediction methods.

Our results show that rainfall predictability is higher in the tropics than in the extratropics. This is expected, as the atmosphere and ocean are strongly coupled in the tropics, whereas the extratropical atmosphere exhibits greater internal variability. This means that atmospheric patterns in the tropics are more strongly influenced by underlying SSTs and are therefore more predictable than in the extratropics, where atmospheric conditions are more affected by weather systems and dependent on initial conditions64.

Precipitation variability explained by MoV in our analysis reflects both the predictability afforded by MoV and the impact of certain choices and assumptions made during the analysis. For example, we have chosen to examine seasonal rather than monthly precipitation anomalies. Short timescale MoV like the MJO may offer greater predictability at shorter timescales as their impact will become aliased at longer timescales. Similarly, result might well be different had we explored MoV lagged by one or more seasons. In this study, we have focused on concurrent relationships between rainfall and MoV. However, lagged responses on regional rainfall often happen during different MoV phases due to the interactions between the MoV-related anomalies and background atmospheric circulation and the indirect effects from other ocean basins44. For example, Australian rainfall is more consistently affected by the developing phase of ENSO from September to November and usually weakens during the peak of ENSO from December to February. Northeast Brazil is more strongly related to the decaying phase of ENSO from March to May due to the indirect effect of ENSO onto the tropical Atlantic. Therefore, incorporating these lagged effects between climate modes and precipitation may enhance predictability as suggested in previous studies using traditional methods65,66,67. To further improve precipitation predictability in smaller regions, a selection of lagged climate modes and lag windows could be incorporated as additional predictors and tested within this approach. Here, we opted for this targeted approach without lagged predictors, given that including numerous additional combinations at a global scale would become computationally impractical.

In our analysis, we have included Niño3 and GMT in the base models. In cases where Niño3 and GMT are poor predictors, their inclusion could diminish the predictive skill of the models (e.g., as a result of overfitting from superfluous predictors). However, as the regional analysis demonstrates, this is unlikely to be a prominent effect, and in most areas, these predictors enhance predictability (see Supplementary Fig. S12). Additionally, we have selected a set of commonly used MoV; but including further, regionally relevant modes may improve predictability.

The quantified predictability is based on an assessment of relationships between MoV and rainfall during the historical period. However, under global warming and large-scale climate influences such as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO), and Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), these relationships may undergo decadal or multi-decadal variations, which could alter predictability in the future. Consequently, the presented predictability should not be viewed as static, and future assessments of rainfall predictability should build upon current methods while incorporating these multi-decadal climate modes.

Prediction skill will also likely be sensitive to the choice of precipitation dataset, noting the large variability that exists across precipitation datasets68. To explore this, we repeated the analysis for DJF using the gauge-based Climate Research Unit gridded Time Series (CRU TS69) precipitation dataset and found that the spatial patterns of explained precipitation variability and types of relationship (linear/complex) were close to those from GPCC, with only small regional differences (Supplementary Figs. S14 and S15), and distribution statistics were very consistent. The median, 75th percentile, and 99th percentile for GPCC were R² = 12%, 20%, and 47%, and CRU TS produced comparable values at 11.9%, 20.2%, and 48.5% respectively (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S14). While this suggests robustness in our findings with these datasets, it remains uncertain how results might vary with other precipitation datasets.

A limitation inherent in the Linear Regression model is the linear relationship between some predictors (see Supplementary Fig. S16). While most cross-correlations between predictors have magnitudes less than 0.3, strong correlations exist among the various ENSO indices (Niño3, Niño4 and SOI), which are part of the same phenomenon. However, since the focus of the linear model was not on interpreting predictor weights, these correlations do not impact the analysis. Additionally, Random Forest is robust to multicollinearity, further ensuring that the results are not affected by correlated predictors.

The dominance of non-linear Random Forest models over Linear Regression models (Fig. 4) should not be surprising. There are known non-linearities in certain climate modes. For instance, ENSO exhibits a skewed distribution, where positive El Niño events tend to be stronger and last longer than negative La Niña events. Additionally, El Niño anomalies are generally located farther to the east than La Niña anomalies, resulting in asymmetrical atmospheric teleconnections and impacts49,50,70,71. Our results further underscore the significance of non-linear MoV interactions.

Broad statements suggesting it will be wetter or dryer during certain phases of climate modes hide important detail that could risk misinforming decision makers and suggest greater certainty than is supported by evidence. For instance, while the 2023-2024 El Niño event generally matched ENSO expectations around the United States in DJF72, it defied expectations on the east coast of Australia, which experienced a wet summer despite anticipated dry conditions and increased fire weather. The ability of large-scale modes of climate variability to predict precipitation anomalies is strongly dependent on location and on the time of year. Even where one or more modes of variability do provide prediction skill, the amount of variability explained in seasonal precipitation anomaly typically does not exceed 50%. Our work highlights that the communication of the influence of MoV to the general public and those who rely on them for decision making requires nuance, and setting realistic expectations about the information they provide.

Methods

This study aims to quantify the explained variability in precipitation anomalies offered by large-scale modes of climate variability (MoV) for each 1o × 1o land grid cell, excluding Antarctica, in different seasons. This involves identifying the set of MoV predictors and the modelling approach (linear or non-linear) that form the best model for predicting contemporaneous precipitation anomalies in each grid cell. The proportion of explained variability in precipitation anomalies is then quantified from this model out-of-sample.

Precipitation data

Gridded monthly precipitation data at 1 degree resolution, covering a period of 41 years from January 1982 to December 2022, are taken from the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC). This observation-based dataset interpolates quality controlled global station data73. The employed dataset combines the Full Data Product (V2022) for 1982–2020 and the Monitoring Product for the years 2021 and 2022. At each grid point, monthly anomalies of precipitation are computed by subtracting the climatological monthly cycle from each monthly total. Subsequently, 3-month seasonal precipitation anomalies are computed from the arithmetic averages of monthly anomalies during December, January, February (DJF), March, April, May (MAM), June, July, August (JJA), and September, October, November (SON). As a result, for every grid cell and season, we construct four time series of 41 seasonal precipitation anomalies.

Large-scale modes of climate variability

We examine various MoV for their value as predictors of contemporaneous precipitation anomalies. Several indices are typically used to characterise ENSO. To describe different aspects of ENSO, we use the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), which represents the zonal sea level pressure gradient between the western and central Pacific, and the SST-based indices Niño3, and Niño474, which are representative of canonical eastern Pacific ENSO events and central Pacific events, respectively. Additional MoV considered in the analysis include IOD, Atlantic Niño (A. Niño), NAO, SAM, MJO and Tropical Northern Atlantic (TNA). Although not traditionally considered a major MoV, our analysis shows that TNA improves predictability in many regions. Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table S1 show each of these MoV, including the indices used to represent these modes, regions used to calculate the various indices and associated data source. While numerous studies have examined these MoV individually or in pairs, a comprehensive analysis encompassing all of them in a single study has been less common. We note that other climate modes, such as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO), and Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), which represent interdecadal fluctuations, can influence precipitation predictability. However, given the short instrumental record for high quality rainfall, obtaining robust statistical relationships to low frequency MoV becomes problematic.

Recognising that the influence of MoV on precipitation may be non-stationary due to global warming, and that in many regions, land precipitation exhibits significant trends over the study period75 that could further contribute to this non-stationarity, we have incorporated global mean temperature (GMT) as an additional predictor to account for potential non-stationarity. We use the Berkeley Earth Combined Land and Ocean Temperature Field dataset76, which provides monthly global temperature anomalies relative to the 1951–1980 baseline.

Finally, we have calculated the seasonal averages for each of these indices, generating four seasonal time series for each index.

Climate modes predictors and modelling approaches

We employ 46 different combinations of predictors. Each combination incorporates GMT and Niño3, plus up to two additional climate mode predictors selected from Supplementary Table S1. Niño3 is included in each combination because ENSO is the major driver of precipitation variability globally77. We demonstrate the importance of including GMT as a predictor by showing that it improves predictability compared to using Niño3 alone (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). We use two modelling approaches: Linear Regression (LR) and non-linear, non-parametric modelling with Random Forest (RF). The non-linear modelling approach aims to capture the relationship between climate modes and precipitation, including both the direct effects of individual climate modes and the effects of their interactions on precipitation. Deep learning models, which are also very effective in handling non-linearity, are inherently data-intensive78, and so were not useful in this context where the sample size is relatively small. In total 92 model setups (two modelling approaches × 46 predictor sets) were used for the prediction of seasonal precipitation anomalies in each grid cell. We note that substituting Niño3 with Niño4 in the analysis has little effect on the results of this study, as demonstrated in analysis over Australia, where a relatively large proportion of rainfall is explained by ENSO (Supplementary Fig. S17).

Developing optimal models for seasonal precipitation anomalies prediction from climate modes

Our methodology predicts contemporaneous precipitation anomalies using an out-of-sample approach at each grid cell. To achieve this, for each land grid cell, all models are trained with data from a specific season using 40 years of observations (40 values in total) and then used to predict precipitation for the same season in a different, out-of-sample year. By repeating this for all 41 years, we systematically generate out-of-sample predictions of precipitation anomalies for the entire period. Additionally, since we are using 92 possible model setups, we predict 92 time-series of seasonal precipitation anomalies for each grid cell. These predictions are then evaluated against observed precipitation anomalies using a benchmark metric, with the aim of identifying the model that offers the best out-of-sample predictive capacity.

Performance Metric

The predicted out-of-sample time series are compared to observed precipitation anomalies using the correlation coefficient (Cor) and mean absolute error (MAE). The models are ranked separately based on Cor (RankCor) and MAE (RankMAE), and an average rank is calculated using a weighted formula (0.7 × RankCor + 0.3 × RankMAE) to determine the overall rank of the 92 models and select those that performs the best. A larger weight was given to Cor because a strong correlation was found to be more essential for achieving predictability in precipitation anomalies than a small bias. This approach led to fewer grid cells with negative R2 values, indicating areas with no predictability. However, the results were found to be relatively insensitive to this choice of weights We additionally ensure that the out-of-sample correlation is positive. If the best model does not meet this criterion, no model will be selected, implying seasonal precipitation anomalies cannot be effectively predicted from MoV alone.

Quantifying the explained variability in seasonal precipitation anomalies by climate modes

For each season and land grid cell, we use the best model to compute the proportion of explained variability (R²) in precipitation anomalies as follows:

where \({{SS}}_{{tot}}\) is the total sum of squares, which measures the total variability in the observed data relative to the mean, such that

Here, \({P}_{{obs}}\) is the observed time-series of precipitation anomalies, and \(\bar{{P}_{{obs}}}\) is its temporal mean.

SSres is the residual sum of squares, which measures the variability that is not explained by the model, where,

\({{SS}}_{{res}}=\sum {({P}_{{obs}}-{P}_{{pred}})}^{2}\) and Ppred is the predicted time-series of precipitation anomalies.

The best score that can be achieved is 1. When R2 is 0, it indicates that the model’s predictions are no better than using climatology and that the MoV predictors do not provide any information about the sign or magnitude of the precipitation anomaly. An R2 value can also be negative, suggesting that the model is less accurate than using climatology, failing to identify even the sign of the precipitation anomaly. A high positive R2 value suggests that the model can successfully predict the sign and the magnitude of the seasonal precipitation anomaly from the MoV predictors of the model.

Analysing the importance of climate modes for enhancing the predictability of precipitation anomalies

We analyse the importance of MoV for enhancing predictability for different regions and seasons. To achieve this, we first consider two reference models, RF and LR, each with Niño3 and GMT as the sole predictors. Each additional MoV appears in a total of 18 models (for example, IOD is in the nine predictor sets indexed 1, 10–17 in Supplementary Table S2 that are used for both the RF and LR models). The importance score is the proportion of these 18 models that outperform the two reference models. If the importance score for a given MoV is 1, then the MoV is deemed of ‘very high’ importance. If it scores between 0.5 and 1, then it is considered of ‘high’ importance. If it scores less than 0.5, then it is considered of ‘low’ importance.

Data availability

The Niño3 SST anomalies index is available form https://psl.noaa.gov/data/timeseries/monthly/NINO3/, the Niño4 SST anomalies index is available from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/timeseries/monthly/NINO4/, the Equatorial SOI is available from https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/data/indices/reqsoi.for, the Tropical North Atlantic Index is available from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/tna.data, the Marshall Southern Annular Mode index is available from https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/precip/CWlink/daily_ao_index/aao/aao_index.html, the North Atlantic Oscillation index is available from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/timeseries/monthly/NAO/, the Atlantic 3 index is available from https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/phod/regsatprod/atl3/sst_ts.php, the Indian Ocean Dipole index is available from https://psl.noaa.gov/gcos_wgsp/Timeseries/DMI/, the Madden-Julian Oscillation data is available from http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/mjo/graphics/rmm.74toRealtime.txt, the global mean temperature data is available from https://berkeley-earth-temperature.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/Global/Land_and_Ocean_complete.txt. The GPCC Full Data Monthly v2022 is available at https://opendata.dwd.de/climate_environment/GPCC/full_data_monthly_v2022/10/, and the GPCC Monitoring Product is available at https://opendata.dwd.de/climate_environment/GPCC/monitoring_v2022/. CRU-TS (v4) dataset is available at https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/index.htm.

Code availability

The computer codes have been implemented in the open-source software RStudio using R. Code is flexible and ubiquitous with many publicly available examples. The main packages used to perform the analysis are: ‘Terra’ for handling the global gridded precipitation data, ‘dplyr’ for dataframe manipulations, ‘ggplot2’ and ‘rasterVis’ for data visualisation, ‘Ranger to carry out the Random Forest analysis.

References

Karoly, D. J. Southern hemisphere circulation features associated with El Niño-Southern Oscillation events. J. Clim. 2, 1239–1252 (1989).

Alexander, M. A. et al. The atmospheric bridge: The influence of ENSO teleconnections on air–sea interaction over the global oceans. J. Clim. 15, 2205–2231 (2002).

Wallace, J. M. & Gutzler, D. S. Teleconnections in the geopotential height field during the Northern Hemisphere winter. Mon. Weather Rev. 109, 784–812 (1981).

De Viron, O., Dickey, J. O. & Ghil, M. Global modes of climate variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1832–1837 (2013).

Bjerknes, J. Atmospheric teleconnections from the equatorial Pacific. Mon. Weather Rev. 97, 163–172 (1969).

Saji, N., Goswami, B., Vinayachandran, P. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the Tropical Ocean. Nature 401, 360–363 (1999).

Barnston, A. G. & Livezey, R. E. Classification, seasonality and persistence of low-frequency atmospheric circulation patterns. Mon. Weather Rev. 115, 1083–1126 (1987).

Lyon, B. & Barnston, A. G. ENSO and the spatial extent of interannual precipitation extremes in tropical land areas. J. Clim. 18, 5095–5109 (2005).

Vicente‐Serrano, S. M. et al. A multiscalar global evaluation of the impact of ENSO on droughts. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, (2011).

Chiew, F. H. S. & McMahon, T. A. Global ENSO-streamflow teleconnection, streamflow forecasting and interannual variability. Hydrol. Sci. J. 47, 505–522 (2002).

Liu, Y., Cai, W., Lin, X., Li, Z. & Zhang, Y. Nonlinear El Niño impacts on the global economy under climate change. Nat. Commun. 14, 5887 (2023).

McGregor, G. R. & Ebi, K. El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Health: An Overview for Climate and Health Researchers. Atmosphere 9 (2018).

Heino, M. et al. Two-thirds of global cropland area impacted by climate oscillations. Nat. Commun. 9, 1257 (2018).

Rampal, N. et al. Seasonal forecasting of mussel aquaculture meat yield in the Pelorus Sound. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1195921 (2023).

Solow, A. R. et al. The value of improved ENSO prediction to US agriculture. Clim. Change 39, 47–60 (1998).

Letson, D. et al. Value of perfect ENSO phase predictions for agriculture: evaluating the impact of land tenure and decision objectives. Clim. Change 97, 145–170 (2009).

Chen, D. & Cane, M. A. El Niño prediction and predictability. J. Comput. Phys. 227, 3625–3640 (2008).

Kirtman, B. P. et al. Current status of ENSO forecast skill: A report to the CLIVAR Working Group on Seasonal to Interannual Prediction. (2001).

Wang, G.-G., Cheng, H., Zhang, Y. & Yu, H. ENSO analysis and prediction using deep learning: A review. Neurocomputing 520, 216–229 (2023).

O’Kane, T. J. et al. Enhanced ENSO prediction via augmentation of multimodel ensembles with initial thermocline perturbations. J. Clim. 33, 2281–2293 (2020).

Gibson, P. B. et al. Training machine learning models on climate model output yields skillful interpretable seasonal precipitation forecasts. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 159 (2021).

Colfescu, I., Christensen, H. & Gagne, D. J. A machine learning‐based approach to quantify ENSO sources of predictability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL105194 (2024).

Cai, W. et al. Climate impacts of the El Niño–southern oscillation on South America. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 215–231 (2020).

Ropelewski, C. F. & Halpert, M. S. North American precipitation and temperature patterns associated with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Mon. Weather Rev. 114, 2352–2362 (1986).

Deser, C., Simpson, I. R., McKinnon, K. A. & Phillips, A. S. The Northern Hemisphere extratropical atmospheric circulation response to ENSO: How well do we know it and how do we evaluate models accordingly? J. Clim. 30, 5059–5082 (2017).

Brönnimann, S. Impact of El Niño–southern oscillation on European climate. Rev. Geophys. 45, (2007).

Nicholson, S. E. & Kim, J. The relationship of the El Niño–Southern oscillation to African rainfall. Int. J. Climatol. A J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 17, 117–135 (1997).

Turner, J. The el nino–southern oscillation and antarctica. Int. J. Climatol. A J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 24, 1–31 (2004).

Hendon, H. H. Indonesian rainfall variability: Impacts of ENSO and local air–sea interaction. J. Clim. 16, 1775–1790 (2003).

Hrudya, P. H., Varikoden, H. & Vishnu, R. A review on the Indian summer monsoon rainfall, variability and its association with ENSO and IOD. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 133, 1–14 (2021).

Wang, B., Wu, R. & Fu, X. Pacific–East Asian teleconnection: how does ENSO affect East Asian climate? J. Clim. 13, 1517–1536 (2000).

Abid, M. A., Almazroui, M., Kucharski, F., O’Brien, E. & Yousef, A. E. ENSO relationship to summer rainfall variability and its potential predictability over Arabian Peninsula region. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 20171 (2018).

McBride, J. L. & Nicholls, N. Seasonal relationships between Australian rainfall and the Southern Oscillation. Mon. Weather Rev. 111, 1998–2004 (1983).

Santoso, A. et al. ENSO extremes and diversity: Dynamics, teleconnections, and impacts. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 1969–1972 (2015).

Tozer, C. R. et al. Impacts of ENSO on Australian rainfall: what not to expect. J. South. Hemisph. Earth Syst. Sci. 73, 77–81 (2023).

Nobre, P. & Shukla, J. Variations of sea surface temperature, wind stress, and rainfall over the tropical Atlantic and South America. J. Clim. 9, 2464–2479 (1996).

Herceg‐Bulić, I., Mezzina, B., Kucharski, F., Ruggieri, P. & King, M. P. Wintertime ENSO influence on late spring European climate: the stratospheric response and the role of North Atlantic SST. Int. J. Climatol. 37, 87–108 (2017).

Enfield, D. B. Relationships of inter‐American rainfall to tropical Atlantic and Pacific SST variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 23, 3305–3308 (1996).

Kumar, K. K., Rajagopalan, B., Hoerling, M., Bates, G. & Cane, M. Unraveling the mystery of Indian monsoon failure during El Niño. Sci. (80-.) 314, 115–119 (2006).

Holgate, C. et al. The impact of interacting climate modes on east Australian precipitation moisture sources. J. Clim. 35, 3147–3159 (2022).

Cowan, T., Wheeler, M. C. & Marshall, A. G. The combined influence of the Madden–Julian oscillation and El Niño–Southern Oscillation on Australian rainfall. J. Clim. 36, 313–334 (2023).

Yoon, J.-H. & Zeng, N. An Atlantic influence on Amazon rainfall. Clim. Dyn. 34, 249–264 (2010).

Mao, Y. et al. Phase coherence between surrounding oceans enhances precipitation shortages in Northeast Brazil. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097647 (2022).

Taschetto, A. S. et al. ENSO atmospheric teleconnections. in El Niño southern oscillation in a changing climate 309–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119548164.ch14 (Wiley Online Library, 2020).

Dong, Z. et al. A skilful seasonal prediction for wintertime rainfall in southern Thailand. Int. J. Clim. 42, 10048–10061 (2022).

Jung, J. & Kim, H. S. Predicting temperature and precipitation during the flood season based on teleconnection. Geosci. Lett. 9, 4 (2022).

Barnston, A. G. & Smith, T. M. Specification and prediction of global surface temperature and precipitation from global SST using CCA. J. Clim. 9, 2660–2697 (1996).

Garcia-Villada, L. P., Donat, M. G., Angélil, O. & Taschetto, A. S. Temperature and precipitation responses to El Niño-Southern Oscillation in a hierarchy of datasets with different levels of observational constraints. Clim. Dyn. 55, 2351–2376 (2020).

Frauen, C., Dommenget, D., Tyrrell, N., Rezny, M. & Wales, S. Analysis of the nonlinearity of El Niño–Southern Oscillation teleconnections. J. Clim. 27, 6225–6244 (2014).

Chung, C. T. Y. & Power, S. B. The non-linear impact of El Niño, La Niña and the Southern Oscillation on seasonal and regional Australian precipitation. J. South. Hemisph. Earth Syst. Sci. 67, 25–45 (2017).

Trigo, R. M., Osborn, T. J. & Corte-Real, J. M. The North Atlantic Oscillation influence on Europe: climate impacts and associated physical mechanisms. Clim. Res. 20, 9–17 (2002).

Hurrell, J. W. Influence of variations in extratropical wintertime teleconnections on Northern Hemisphere temperature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 23, 665–668 (1996).

Behera, S. K. et al. Paramount impact of the Indian Ocean dipole on the East African short rains: A CGCM study. J. Clim. 18, 4514–4530 (2005).

Palmer, P. I. et al. Drivers and impacts of Eastern African rainfall variability. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 254–270 (2023).

Kurniadi, A., Weller, E., Min, S.-K. & Seong, M.-G. Independent ENSO and IOD impacts on rainfall extremes over Indonesia. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 3640–3656 (2021).

Aldrian, E. & Dwi Susanto, R. Identification of three dominant rainfall regions within Indonesia and their relationship to sea surface temperature. Int. J. Climatol. A J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 23, 1435–1452 (2003).

Hendon, H. H., Lim, E.-P. & Nguyen, H. Seasonal variations of subtropical precipitation associated with the southern annular mode. J. Clim. 27, 3446–3460 (2014).

Power, S., Haylock, M., Colman, R. & Wang, X. The predictability of interdecadal changes in ENSO activity and ENSO teleconnections. J. Clim. 19, 4755–4771 (2006).

Ashok, K., Guan, Z., Saji, N. H. & Yamagata, T. Individual and combined influences of ENSO and the Indian Ocean dipole on the Indian summer monsoon. J. Clim. 17, 3141–3155 (2004).

Donald, A. et al. Near‐global impact of the Madden‐Julian Oscillation on rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, (2006).

Pohl, B. & Camberlin, P. Influence of the Madden–Julian oscillation on East African rainfall: II. March–May season extremes and interannual variability. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. A J. Atmos. Sci. Appl. Meteorol. Phys. Oceanogr. 132, 2541–2558 (2006).

Nicholson, S. E. & Dezfuli, A. K. The relationship of rainfall variability in western equatorial Africa to the tropical oceans and atmospheric circulation. Part I: The boreal spring. J. Clim. 26, 45–65 (2013).

Mason, S. J. & Goddard, L. Probabilistic precipitation anomalies associated with EN SO. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 82, 619–638 (2001).

Shukla, J. Predictability in the midst of chaos: A scientific basis for climate forecasting. Sci. (80-.) 282, 728–731 (1998).

Kawamura, R., Suppiah, R., Collier, M. A. & Gordon, H. B. Lagged relationships between ENSO and the Asian Summer Monsoon in the CSIRO coupled model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, (2004).

Xu, Z. X., Takeuchi, K. & Ishidaira, H. Correlation between El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and precipitation in South‐east Asia and the Pacific region. Hydrol. Process. 18, 107–123 (2004).

Hamadalnel, M. & Abdalla, I. Lagged and Timely Effect of ENSO on Summer Monsoon Precipitation over Sudan across 1991–2020. J. Fac. Sci. Technol. 83–92 (2021).

Alexander, L. V. et al. Intercomparison of annual precipitation indices and extremes over global land areas from in situ, space-based and reanalysis products. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 55002 (2020).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. data 7, 109 (2020).

Hoerling, M. P., Kumar, A. & Zhong, M. El Niño, La Niña, and the nonlinearity of their teleconnections. J. Clim. 10, 1769–1786 (1997).

Dommenget, D., Bayr, T. & Frauen, C. Analysis of the non-linearity in the pattern and time evolution of El Niño southern oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2825–2847 (2013).

L’Heureux, M. L. et al. How Well Do Seasonal Climate Anomalies Match Expected El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Impacts? Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-23-0252.1 (2024).

Schneider, U. et al. GPCC full data reanalysis version 7.0: monthly land-surface precipitation from rain gauges built on GTS based and historic data. Research data archive at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, Computational and Information Systems Laboratory. (2016).

Reynolds, R. W., Rayner, N. A., Smith, T. M., Stokes, D. C. & Wang, W. An improved in situ and satellite SST analysis for climate. J. Clim. 15, 1609–1625 (2002).

Hobeichi, S. et al. Reconciling historical changes in the hydrological cycle over land. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 1–9 (2022).

Rohde, R. A. & Hausfather, Z. The Berkeley Earth land/ocean temperature record. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 3469–3479 (2020).

McPhaden, M. J., Zebiak, S. E. & Glantz, M. H. ENSO as an integrating concept in earth science. Sci. (80-.) 314, 1740–1745 (2006).

Hobeichi, S., Abramowitz, G., Evans, J. P. & Ukkola, A. Toward a robust, impact‐based, predictive drought metric. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR031829 (2022).

Acknowledgements

All the authors acknowledge the support of the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes (CE170100023). S.H., A.S.T., and L.V.A. acknowledge the support of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the Weather of the 21st Century (CE230100012). Additionally, A.S.T. acknowledges support from ARC Grant (FT160100495) and thanks the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program, and L.V.A. is supported by ARC Grant (FT210100459). N.R. received funding from the New Zealand MBIE Endeavour Smart Ideas Fund (C01X2202). The work was undertaken using resources from the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI), which is supported by the Australian government. We thank The Global Precipitation Climatology Centre, NOAA, Berkeley Earth, Climatic Research Unit (University of East Anglia) and NCAS, and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology for making their data publicly available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The ideas for this study originated in discussions with G.A., A.S.G., A.S.T., and D.R. S.H. and G.A. designed the study with advice from A.S.T., A.S.G., and L.V.A. S.H. performed the analysis with input from A.S.G., G.A., and A.S.T. S.H., G.A., A.S.G., and A.S.T. interpreted and discussed the results with input from D.R., N.R., L.V.A. and A.J.P. S.H. and G.A. wrote the paper with help from A.S.G. and A.S.T. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hobeichi, S., Abramowitz, G., Sen Gupta, A. et al. How well do climate modes explain precipitation variability?. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 295 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00853-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00853-5

This article is cited by

-

Spatial connections between the timing of hydroclimatic extremes

Nature Water (2025)

-

Hydro-climatic stress and ecosystem vulnerability in a highland lake: the case of Dayet Aoua (1935–2022), Middle Atlas, Morocco

Modeling Earth Systems and Environment (2025)

-

Physical mechanisms of meteorological drought development, intensification and termination: an Australian review

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Climate impacts of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation on Australia

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2025)