Abstract

The South Asian summer monsoon (SAM) bears significant importance for agriculture, water resources, economy, and environmental aspects of the region for nearly 2 billion people. To minimize the adverse impacts of global warming, Stratospheric Aerosol Intervention (SAI) has been proposed to lower surface temperatures by reflecting a portion of solar radiation back into space. However, the effects of SAI on SAM are still very uncertain. Our study identifies the main drivers leading to a reduction in the mean and extreme summer monsoon precipitation under SAI. These include SAI-induced lower stratospheric warming and the associated weakening of the northern hemispheric subtropical jet, changes in the upper-tropospheric wave activities, geopotential height anomalies, a reduction in the strength of the Asian Summer Monsoon Anticyclone, and, to some degree, local dust changes. As the interest in SAI research grows, our results demonstrate the urgent need to further understand SAM variability under different SAI scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The South Asian Summer Monsoon (SAM) rainfall contributes to ~80% of the total annual rainfall over the Indian region1,2. As such, any change in mean or extreme precipitation regionally can substantially impact the economy, agricultural practice, water resources, biodiversity, and the overall ecosystem3,4, especially in regions like South Asia and India in the Global South. A drying trend was observed in all-India summer monsoon rainfall from the mid to late 20th century5,6,7. However, recent research reports a revival of monsoon rainfall with an increasing trend in the early 21st century8. Human activity has warmed the world more than 1 °C since pre-industrial times, and the destructive impacts are widely felt across the globe. The climate projections studies indicate that the warming will continue and likely exceed the Paris climate target within the next few years9. Recent studies using global coupled models commonly agree that the mean and extreme Indian monsoon rainfall will increase due to global warming in the 21st century10,11,12.

The scientific community has recommended rapid emission cutbacks for the reduction of global warming; however, global efforts to date are not providing enough confidence that the ongoing warming trend can be avoided13. In that context, geoengineering (or solar climate intervention) methods are being proposed that could potentially ameliorate global warming14,15. Among the proposed methods, stratospheric aerosol intervention (referred to simply as SAI hereafter) is estimated to be more effective and potentially less expensive than other methods16,17. Sulfate aerosols have been widely studied for SAI18,19,20. The method was proposed in 197021 and brought to the forefront in 200622. It involves injecting sulfur dioxide (SO2) into the stratosphere, which then oxidizes and generates sulfate aerosols23. The enhanced stratospheric aerosol layer would scatter some incoming solar radiation and thus cool the Earth’s surface. The method is often viewed as analogous to the influence of large volcanic eruptions. However, SAI could have different impacts and risks since it would have to be applied over a longer time until atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations have declined sufficiently20. Concerns exist about the adverse effects of SAI24, further demanding the need to fully understand the benefits and drawbacks before considering it as a potential climate response option. To understand the impacts and risks of long-term SAI applications, multiple numerical simulations with comprehensive Earth System Models are required as a first step before any SAI applications can be considered25.

Past modeling studies with the Community Earth System Model (CESM) have demonstrated that under a future high-end global warming scenario, strategic SAI applications could be successful at keeping the global mean surface temperatures and their large-scale gradients at a quasi-present-day level18,26,27,28. However, model studies have found a slowing of the global hydrological cycle under concurrent SAI-induced restoration of the global mean surface temperatures29, as well as significant regional changes in surface temperature and rainfall30,31, including the Asian monsoon region. However, the magnitude and the sign of the regional responses can vary depending on the injection strategy32,33. Generally, the regional analysis showed that SAI could change dry regions to become wetter and wet regions to become dryer30. SAI could further reduce the frequency of heavy and exceptionally heavy precipitation in tropical regions and the number of consecutive dry days in arid regions34,35.

While SAI can successfully reduce some risks associated with climate change (e.g., heatwaves, the loss of sea ice in the Arctic, permafrost thaw, and reduction of Greenland Ice Sheet mass)36, the effects to SAM under SAI are much less understood. Most of the previous studies investigating SAI impacts on the Indian monsoon used idealized experiments, whereby the effect of SAI is approximated by reducing the value of the solar constant or using only a single point SO2 injection31,37,38. In addition, the driving mechanisms behind any change in SAM remain one of the least explored in the context of SAI. In this study, we investigate the impacts of SAI on SAM using a strategic SAI realization that utilizes four SO2 injection locations and a control algorithm aiming to minimize large-scale surface temperature changes and their gradients, thus effectively minimizing any impact of those on SAM. We further support the results with the assessment of the possible drivers behind the simulated SAM changes. This work is intended to help identify detailed processes that lead to changes in SAM precipitation under SAI, which may eventually lead to redesigning SAI injection strategies27,28,39,40 to minimize the side effects, including changes in regional precipitation.

Results

Mean precipitation response to SAI and climate change

Figure 1 depicts the spatial mean precipitation anomalies for the SAM regions under the future RCP8.5 and SAI scenarios. Please note that during the summer monsoon season, the precipitation is mainly liquid rain41; hence, we use the words interchangeably in the manuscript. The model rainfall is evaluated against the observation datasets (Fig. S1a, b). The control run captures the mean SAM rainfall and seasonal cycle reasonably well compared to the observation. However, a mean dry bias is observed over SAM regions similar to Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase (CMIP) 5 and 6 models42,43. This model feature is not expected to affect our conclusions when comparing simulations with and without SAI to present-day conditions. One merit of using this model is that this is one of the few models that interactively simulate the aerosols in the stratosphere and troposphere and allow us to perform geoengineering (SAI) simulations28.

SAM summer (June–July–August, JJA) mean rainfall under a global warming scenario increases significantly over the Indian subcontinent, especially in the Himalayas, northeast of the Bay of Bengal, and the west coast of India (Fig. 1a). Similar findings are reported under extreme global warming scenarios (SSP5-8.5 and RCP-8.5) using CMIP-5 and 6 models10,12. Modeling studies agree that such an increase in the summer monsoon rainfall over South Asia is primarily attributed to an increase in the moisture-holding capacity of the atmosphere under a warmer climate12,44. In contrast, in response to SAI, rainfall significantly declines over most of northern and central India compared to CTRL (Fig. 1b). More than 1.5 mm day−1 reduction in rainfall is simulated in the core central Indian region (CI hereafter) (as defined in Goswami et al., 2006) in 2070–2090, with a further extension of the rainfall reduction into the regions of the Bay of Bengal to the east of the Indian continent. Compared to CTRL, the area averaged mean JJA precipitation reduction for SAI is greater than 20% over CI (Fig. S1c). In addition, a net reduction in rainfall (~11.6%) over the Indian subcontinent (ISMR) under SAI, compared to CTRL, indicates a drought-like condition (Fig. S1d). Unlike the overall increase in precipitation over the SAM region under RCP 8.5 (~5% over CI and ~15% over ISMR compared to CTRL, Fig. S1c, d), the rainfall changes simulated under SAI do not decrease everywhere in the region. Instead, positive rainfall anomalies are found over the southern parts of India, with more rainfall increases extending northeast from India into parts of China. Notably, the mechanisms through which SAI can impact SAM and the associated precipitation patterns are relatively unknown. In the subsequent section, we investigate the possible drivers behind the rainfall anomalies.

Drivers of the SAM rainfall changes under SAI

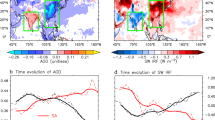

Past studies have highlighted that SAI can affect the mean climate of the stratosphere28,45,46. Sulfate aerosols located in the stratosphere are effective at reflecting and scattering incoming solar radiation and, therefore, act to cool the surface and the free troposphere, but also absorb infrared radiation47, resulting in a warming of the lower tropical stratosphere45,48,49. In the specific SAI scenario used here, 30–40 Tg-SO2/yr injections were needed to counter the RCP8.5 warming of 3–4 °C by 2070–2090 in this model. The resulting lower stratospheric warming that maximizes in the tropics reaches more than >8 °C at ~50 hPa (Fig. 2a).

JJA averaged a latitude-height temperature anomalies, b zonal wind anomalies, c 200 hPa meridional wind anomalies showing wave activities, d 200 hPa wind anomalies, e 850 hPa wind anomalies and f vertical wind anomalies averaged over 5–35° latitude (covering Indian region) between SAI and CTRL. Stippling as in Fig. 1.

The strong anomalous warming of the lower stratosphere imposed by SAI leads to tropical tropospheric circulation changes32,46,50, a weakening of the subtropical jets in both hemispheres (Fig. 2b) and a modification in the wave activity in the subtropics (Fig. 2c). Independently of SAI, previous studies have linked upper tropospheric waves to Indian and Asian monsoons41,51,52, whereby summertime planetary wave activity at ~200 hPa across Indian longitudes strongly correlates with SAM rainfall53,54,55. Here, we identify a similar connection between the 200 hPa meridional wind anomalies and rainfall changes. SAI-induced lower stratospheric heating and weakening of the northern subtropical jet modulate the mean summertime 200 hPa meridional winds (Fig. 2c), with the anomalies resembling a structure similar to the stationary Rossby wave41,53. The meridional wind response to SAI in the South Asian region basically reinforces the climatological wave pattern (Fig. S2) and results in an anomalous cyclonic circulation at 200 hPa, which consists of anomalous southward flow to the west of India and anomalous poleward flow to the east of India (Fig. 2c). The positive anomaly of the 200 hPa meridional winds is aligned with the reduction in rainfall over the central and northern parts of India.

These changes are also aligned with changes in the climatological Asian Summer Monsoon Anticyclone (ASMA) in the upper troposphere (Fig. S3a) that forms across the Asian Summer Monsoon region and is linked to the heating of the Tibetan plateau and deep convective activities over the head of the Bay of Bengal56.

Under SAI, the ASMA decelerates, which is illustrated by the anomalously cyclonic flow compared to the control simulation (Fig. 2d). We also observe an anomalous splitting of ASMA into two parts, one over India and the other over the Middle East and North Africa region (Fig. 2d). The deceleration of ASMA contributes to the reduction in the strength of the summer monsoon circulation in the lower troposphere (Fig. 2e; see Fig. S3b for the climatology) and the simulated SAI-induced drying over central and northern India.

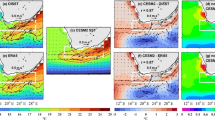

The changes in the upper atmospheric wave activities and weakening of ASMA are also reflected in the associated changes in vertical velocities (Fig. 2f). Changes in the large-scale vertical motions often indicate the surface pressure patterns. For example, anomalous sinking air motion usually corresponds to anomalous high-pressure regions41. Under the SAI scenario, an anomalous downward motion (red in Fig. 2f), indicating reduced upwelling over the longitudes of the core monsoon region, is found; this is also illustrated by the anomalous increase in geopotential height (here illustrated at 500 hPa, Fig. 3a) and sea-level pressure (Fig. 3c) over vast areas of India, Pakistan, and the Middle East. The anomalous subsidence of dry air over the subcontinent inhibits convection and rainfall over the Indian landmass. It also contributes to the anomalous warming at 850 hPa over large parts of Indian subcontinents (>1 °C over the core monsoon region, Fig. 3b) to the reduction in adiabatic cooling. Additionally, slight anomalous upward motion (blue) over the longitudes of the Southern part of the Indian subcontinent (Fig. 2f) seems to support the increasing precipitation in that region. The nature of the phase of upper atmospheric wave activities and pressure velocity anomalies seems sufficient to explain the patterns of mean monsoon rainfall52,53, as discussed in previous section.

Differences in the JJA averaged a 500 hPa geopotential, b 850 hPa temperature, and c surface pressure between SAI and CTRL. Stippling as in Fig. 1.

Other contributors to the reduction in rainfall simulated under SAI are possible. First, SAI-induced warming in the lower stratosphere (Fig. 2a) increases the static stability of the tropical troposphere30,32, potentially inhibiting convection in the core Monsoon region (Fig. 2f). A similar mechanism has been proposed to explain the role of temperature anomalies associated with the different phases of the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation on the tropical convection in observations and idealized models57,58. In accord, using the same dataset, Cheng et al. 50 showed a weakening of the Hadley Circulation in JJA (~3.5% for 2075–2095 compared to baseline), and using the scaling theory, they attributed the response to be dominated by changes (increase) in tropical static stability. Second, the substantial reductions in the low-level wind speed at 850 hPa level over the Arabian Sea (anomalous easterly winds in Fig. 2e; compared with the climatology in Fig. S3b) prevents moisture convergence (Fig. S4) to the mainland, resulting in a reduction of the mean Indian summer monsoon rainfall41,59. Further, a reduction in the JJA precipitation under SAI significantly reduces the soil evaporation during JJA months over India and attains the minimum value (−3.5% compared to the control simulation) in the month of July30. Third, an anomalous northwesterly wind over north India and an anticyclonic feature over the monsoon trough region (over the head Bay of Bengal) do not allow the continental ITCZ to move northward, hindering the monsoon strength and moisture inflow from the Bay of Bengal branch. Please note that using the same datasets, a notable southward shift of global ITCZ was reported (0.7° latitude for 2075–2097) in JJA50.

In addition, we have analyzed the land-sea temperature gradients at the surface and troposphere (following Roxy et al.)60. Although some residual changes are observed regionally, the land-sea temperature gradients at the surface (0.11 °C) and in the troposphere (−0.057 °C) are minimal and insignificant compared to the other explained processes leading to monsoon drying. This is because, in this modeling experiment, the SAI injections are designed and optimized to maintain the global mean near-surface temperatures and their inter-hemispheric and equator-to-pole gradients.

Finally, past studies have reported that a global warming hiatus scenario could further weaken the pressure gradient between Mascarene High and the northern hemisphere landmass61. Our findings show similar results under the SAI scenario (Fig. S5). Such weakening of Mascarene High intensity could have further weakened the high-level cross-equatorial winds in the western Indian Ocean and monsoon hydrology.

Clouds play a crucial role in the energy and hydrological cycles of the Earth–atmosphere system62,63. High clouds dominate the SAM region during monsoon months, whereas low clouds are more frequent64. For the SAI scenario, a significant and widespread reduction in low and high cloud cover is simulated over the Indian region. A notable reduction (>5%) in high cloud cover is found over a large part of the Indian landmass aligned to the maximum rainfall reduction (Fig. 1). A similar signature is also observed in total cloud cover (Fig. 4c). On the contrary, the low cloud anomalies possess a spatial pattern (north–south dipole) similar to precipitation anomalies.

Differences in the JJA averaged a low cloud cover, b high cloud cover, and c total cloud cover between SAI and CTRL in 2070–2090 compared to 2010–2030. Stippling as in Fig. 1.

A previous study using idealized experiments found stratocumulus cloud thinning under a sustained solar geoengineering scenario65. Reductions in optically thick tropical cloud fraction in the boundary layer and mid-troposphere66 and reductions in tropical anvil clouds are also reported under SAI67. Upper tropospheric stratification68, moisture deficit over land30 (Fig. S4), reduced convection, and the lower and mid-tropospheric anomalous high-pressure system are possible reasons behind such widespread reduction in cloud cover under the SAI scenario.

Dust feedback

Dust particles warm the atmosphere while reducing sunlight reaching the surface, leading to atmospheric warming and surface cooling69. The Middle East and North Africa region is the major summertime dust source in South Asia59,70. Observational studies indicate that dust-induced warming (clear sky) is highest over the Arabian Sea compared to many dust-laden regions across the globe71. Based on modeling estimates, local dust-induced radiative forcing could be as large as ~36 W m−2 over the Arabian Sea during the summer monsoon59. Such a large radiative forcing over the Arabian Sea has been found to trigger large-scale convergence over the North Africa/Arabian Peninsula region and act as feedback to strengthen the northward component of the summer monsoon westerly winds over the Arabian Sea59. Consequently, this enhances moisture convergence and precipitation over the Indian region70,72.

We find a substantial reduction in the dust burden under the SAI scenario. Such negative changes in dust have previously been reported from these simulations under both the SAI and RCP scenarios (slightly larger for the SAI scenario), and are due to the weakening of the dust hotspot emissions from the sources of the Middle East, along with changes in soil water, precipitation patterns, and leaf area index73.

In agreement with the previous analysis, we find the most substantial negative changes in regions that are climatologically high in dust (Fig. 5). Such a substantial reduction in dust load over the Arabian sea and adjacent regions might further contribute to the simulated rainfall reduction in the monsoon region under SAI. In addition, an increase in the dust burden is found over regions of the Indo-Gangetic plain, which could be the result of the anomalous SAI-induced monsoon drying over the mainland and a reduction in the strength of wet removal processes, a dominant feature during the monsoon season. Such change in dust over the North Indian regions may have further implications on radiative balance and regional climate change.

The climatological dust burden from CTRL simulation is overlayed as contours. Stippling as in Fig. 1.

Impact of SAI on extreme precipitation

The annual global economic losses from floods have surpassed $30 billion over the previous decade, with a significant portion of these costs attributed to high rainfall events in Asia (International Disaster Data Base, http://www.emdat.be). In addition, the floods attributed to extreme events in India contribute to 10% of the global economic loss. India witnessed 268 reported cases of flooding between 1950 and 2015, impacting around 825 million individuals. These floods displaced 17 million people and caused the loss of 69,000 lives (International Disaster Data Base).

Despite declining trends in mean rainfall (10–20% over the central Indian region), widespread heavy rain events in central India have increased from 1950 to 201574,75. Such a rise in extreme rainfall events over India is linked to the moisture contribution from the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal67. We have investigated the total rainfall in different percentile bands for the control, the future RCP85, and future SAI conditions (Fig. 6) over Central India.

Under the high GHG emission RCP8.5 scenarios, the precipitation is increasing in all the bins. On the other hand, a notable reduction in extreme precipitation (90–99th percentile) is simulated under the SAI scenario compared to the present day (CTRL). In support of our results, past studies using multi-model geoengineering experiments highlight a substantial reduction of the wettest 5-day index (Rx5day), representing an extreme aspect of geoengineering simulations34,76. Such reduction in extreme precipitation is attributed to increased atmospheric stability and, thereby, suppression of atmospheric convection77 in accordance with a general reduction of mean precipitation under SAI29. Hence, this SAI scenario may help reduce precipitation extremes causing devastating floods; however, it may also reduce water availability due to the concurrent reductions in the mean rainfall. It is essential to note that rainfall extremes can have more immediate economic and social effects than mean rainfall changes. Hence, such extremes should be explored more extensively by using impact models78 and planned geoengineering experiments79.

Discussion

The continuing global warming trend due to climate change will likely lead to more irregular precipitation patterns with an increasing risk of both flooding and drought. Using a three-member ensemble from Geoengineering Large Ensemble (GLENS) simulations, our study investigates the effects of stratospheric aerosol intervention (SAI) on the South Asian summer monsoon (SAM). Unlike many of the past SAI studies, which mainly focused on the response to SAI, we have investigated the possible mechanisms behind the rainfall changes in the SAM region, summarized as follows:

-

1.

A reduction in both mean and extreme SAM precipitation was simulated for the SAI scenario compared to both a near present-day period and the same future period with RCP8.5 in the absence of SAI.

-

2.

The use of sulfate aerosols for SAI results in a heating of the lower tropical stratosphere and wave-induced weakening of the northern hemispheric subtropical jet stream.

-

3.

We observe a strong relationship between the SAI-induced phase of wave activities, geopotential height anomalies, the strength of the Asian Monsoon Anticyclone, lower atmospheric pressure gradients, and wind circulations. These changes play a decisive role in lowering summertime rainfall over the core monsoon region.

-

4.

The weakening of the strength of the Asian summer monsoon Anticyclone with SAI dampens the convective activities in the core monsoon region. The positive anomalous pressure in the lower troposphere is further associated with reduction in convection and cloud cover. In addition, the heating in the lower tropical stratosphere acts to increase the tropospheric static stability, which may further reduce tropical convection.

-

5.

A substantial reduction in dust is found over the Arabian Sea. Since local changes in dust can be a significant contributor to the SAM rainfall variability under both present-day and future climate change, such regional dust change might play an additional role in amplifying the SAI effects on SAM hydrology.

The different processes described above may contribute to some extent in driving the SAI-induced changes in the location and magnitude of SAM and its rainfall80. More detailed investigations using additional model experiments are needed to understand and quantify the relative roles of different mechanisms, in particular under different SAI scenarios81 and strategies32. In addition, our results are based on only one climate model, so more work is needed to apply a similar analysis to other models82,83, identifying inter-model differences and potential reasons behind them.

It is worth mentioning that the results reported here do not advocate for any deployment of stratospheric aerosol geoengineering but rather attempt to improve our understanding of its consequences on the regional climate system like SAM. Before considering SAI as a feasible approach working alongside strong greenhouse gas emission reductions to mitigate global warming, it is essential to thoroughly investigate its impact on the Earth system and its consequences for both natural and human systems. Furthermore, we highlight the importance of a future comprehensive analysis considering the broader implications of SAI not just over the Indian and South Asian Monsoon region but across the entire Asia, including China. Our focus on India and the South Asian context provides a critical foundation for understanding the localized effects of SAI and minimizing our existing knowledge gaps particular to this region and should serve as motivation for expanding the assessments to other regions facing similar geopolitical and climatic challenges. As such, our work constitutes a crucial first step to understanding SAM variability under different SAI applications, which would be essential for sustainable development and disaster preparedness in South Asia.

Methods

To investigate the response of SAM rainfall to SAI, we use the output from the Geoengineering Large Ensemble Project (GLENS)28. These model experiments were performed using the Community Earth System Model version 1 (CESM1) with the Whole Atmosphere Community Model (WACCM) as its atmospheric component84. This configuration reproduces the observed changes in aerosol optical depth and surface climatic features in response to the Mt. Pinatubo volcanic eruption in 1991, as well as represents the various atmospheric features like the QBO, ozone, and atmospheric water vapor concentration reasonably well compared to observations84. A horizontal resolution of 0.9° latitude by 1.25° longitude, along with 70 vertical levels up to 140 km, was used for this model simulation. The Modal Aerosol Module (MAM3) scheme85 was employed to interactively simulate the aerosols in the stratosphere and troposphere. WACCM is fully coupled with the Community Land Model, version 4.5 (CLM4.5), as well as interactive ocean and sea–ice models. More details about the model configuration, simulation details, and parametrization process can be found in past literatures28,86.

GLENS28 consists of a 20-member ensemble of the CMIP5 RCP 8.5 scenario over the period 2010–2030 as the control period (CTRL hereafter). Three CTRL simulations continue till 2097 and serve as the baseline future RCP8.5 scenario without SAI (RCP 8.5 hereafter). The SAI scenario (SAI thereafter) is also a 20-member ensemble; it spans 2020–2097 and aims to counter the warming of RCP8.5. In particular, using a feedback control algorithm, SAI simulations inject SO2 into the lower stratosphere (~5 km above tropopause) at four latitudes (15°N/S and 30°N/S), maintaining the global mean surface temperature and the interhemispheric and Equator-to-pole temperature gradients close to the CTRL levels18,28. However, some regional temperature changes could be expected, which is likely due to feedback from residual changes in clouds and rainfall28.

To maintain consistency in the calculation when contrasting simulations with and without SAI, we only use the first three members of each ensemble. We analyze the period 2070–2090 for both RCP and SAI and compare them against the quasi-present-day CTRL (i.e., 2010–2030). Table 1 summarizes the model simulations analyzed. We used JJA hereafter for all the analyses. The rationale for choosing JJA months is that it captures the peak intensity of the South Asian monsoon when rainfall significantly impacts agriculture and water resources. Analyzing this period allows for a clearer understanding of the impact of any forcing on monsoon dynamics and variability. We use JJA in this paper as it is standard for boreal summer. Many earlier studies41,87,88 used JJA months to investigate the SAM response to aerosol forcing. Researchers also found that the observed correlation between the JJA and June–July–August–September (JJAS) rainfall is exceptionally high (>0.95)53, and therefore, our results are likely to be insensitive to the exclusion of September in the analysis.

Data availability

All simulations were performed on the Cheyenne high-performance computing platform (https://doi.org/10.5065/D6RX99H) and are available on the Earth System Grid. More details can be found at https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/community-projects/glens.

Code availability

All the code used in this paper can be obtained at a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Saha, K. R., Mooley, D. A. & Saha, S. The Indian monsoon and its economic impact. GeoJournal 3, 171–178 (1979).

Lobell, D. B., Schlenker, W. & Costa-Roberts, J. Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science 333, 616–620 (2011).

S, G. & S, G. The Indian monsoon, GDP and agriculture. Econ. Polit. Wkly 41, 4887–4895 (2006).

Feng, X., Porporato, A. & Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Changes in rainfall seasonality in the tropics. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 811–815 (2013).

Ramesh, K. V. & Goswami, P. Assessing reliability of regional climate projections: the case of Indian monsoon. Sci. Rep. 4, 4071 (2014).

Saha, A., Ghosh, S., Sahana, A. S. & Rao, E. P. Failure of CMIP5 climate models in simulating post-1950 decreasing trend of Indian monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 7323–7330 (2014).

Salzmann, M. & Cherian, R. On the enhancement of the Indian summer monsoon drying by Pacific multidecadal variability during the latter half of the twentieth century. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 9103–9118 (2015).

Jin, Q. & Wang, C. A revival of Indian summer monsoon rainfall since 2002. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 587–594 (2017).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Water Cycle Changes. Clim. Chang. 2021—Phys. Sci. Basis https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.010 (2023).

Menon, A., Levermann, A., Schewe, J., Lehmann, J. & Frieler, K. Consistent increase in Indian monsoon rainfall and its variability across CMIP-5 models. Earth Syst. Dyn. 4, 287–300 (2013).

Varghese, S. J., Surendran, S., Rajendran, K. & Kitoh, A. Future projections of Indian Summer Monsoon under multiple RCPs using a high resolution global climate model multiforcing ensemble simulations: factors contributing to future ISMR changes due to global warming. Clim. Dyn. 54, 1315–1328 (2020).

Katzenberger, A., Schewe, J., Pongratz, J. & Levermann, A. Robust increase of Indian monsoon rainfall and its variability under future warming in CMIP6 models. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 367–386 (2021).

Parson, E. A. & Reynolds, J. L. Solar geoengineering: Scenarios of future governance challenges. Futures 133, 102806 (2021).

Caldeira, K., Bala, G. & Cao, L. The science of geoengineering. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 41, 231–256 (2013).

Ricke, K., Wan, J. S., Saenger, M. & Lutsko, N. J. Hydrological consequences of solar geoengineering. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 51, 447–470 (2023).

Smith, W. & Wagner, G. Stratospheric aerosol injection tactics and costs in the first 15 years of deployment. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 124001 (2018).

Harding, A. R., Belaia, M. & Keith, D. W. The value of information about solar geoengineering and the two-sided cost of bias. Clim. Policy 23, 355–365 (2023).

Kravitz, B. et al. First simulations of designing stratospheric sulfate aerosol geoengineering to meet multiple simultaneous climate objectives. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 12,616–12,634 (2017).

Visioni, D. et al. Seasonal injection strategies for stratospheric aerosol geoengineering. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 7790–7799 (2019).

Tilmes, S. et al. Reaching 1.5 and 2.0°C global surface temperature targets using stratospheric aerosol geoengineering. Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 579–601 (2020).

Budyko, M. & Landsberg, H. Climatic Changes. (1977).

Crutzen, P. J. Albedo enhancement by stratospheric sulfur injections: a contribution to resolve a policy dilemma? Clim. Chang. 77, 211–220 (2006).

Rasch, P. J., Crutzen, P. J. & Coleman, D. B. Exploring the geoengineering of climate using stratospheric sulfate aerosols: the role of particle size. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, 1–6 (2008).

Robock, A. Benefits and risks of stratospheric solar radiation management for climate intervention (Geoengineering). Bridge 50, 59–67 (2020).

Visioni, D. et al. Opinion: The scientific and community-building roles of the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP)-past, present, and future. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 5149–5176 (2023).

MacMartin, D. G., Kravitz, B., Keith, D. W. & Jarvis, A. Dynamics of the coupled human-climate system resulting from closed-loop control of solar geoengineering. Clim. Dyn. 43, 243–258 (2014).

Kravitz, B., MacMartin, D. G., Wang, H. & Rasch, P. J. Geoengineering as a design problem. Earth Syst. Dyn. 7, 469–497 (2016).

Tilmes, S. et al. CESM1(WACCM) Stratospheric Aerosol Geoengineering Large Ensemble (GLENS) Project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 2361–2371 (2018).

Tilmes, S. et al. The hydrological impact of geoengineering in the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 11-036 (2013).

Simpson, I. R. et al. The regional hydroclimate response to stratospheric sulfate geoengineering and the role of stratospheric heating. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 12587–12616 (2019).

Roose, S., Bala, G., Krishnamohan, K. S., Cao, L. & Caldeira, K. Quantification of tropical monsoon precipitation changes in terms of interhemispheric differences in stratospheric sulfate aerosol optical depth. Clim. Dyn. 61, 4243–4258 (2023).

Bednarz, E. M. et al. Injection strategy—a driver of atmospheric circulation and ozone response to stratospheric aerosol geoengineering. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 13665–13684 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Macmartin, D. G., Visioni, D., Bednarz, E. M. & Kravitz, B. Hemispherically symmetric strategies for stratospheric aerosol injection. Earth Syst. Dyn. 15, 191–213 (2024).

Ji, D. et al. Extreme temperature and precipitation response to solar dimming and stratospheric aerosol geoengineering. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 10133–10156 (2018).

Tye, M. R. et al. Indices of extremes: geographic patterns of change in extremes and associated vegetation impacts under climate intervention. Earth Syst. Dyn. 13, 1233–1257 (2022).

Lee, W. R. et al. High-latitude stratospheric aerosol injection to preserve the Arctic. Earth’s Fut. 11, e2022EF003052 (2023).

Robock, A., Oman, L. & Stenchikov, G. L. Regional climate responses to geoengineering with tropical and Arctic SO2 injections. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, 1–15 (2008).

Bala, G. & Gupta, A. Solar geoengineering research in India. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 23–28 (2019).

MacMartin, D. G., Keith, D. W., Kravitz, B. & Caldeira, K. Management of trade-offs in geoengineering through optimal choice of non-uniform radiative forcing. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 365–368 (2013).

Tilmes, S. et al. Sensitivity of aerosol distribution and climate response to stratospheric SO2 injection locations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 12-591 (2017).

Asutosh, A., Vinoj, V., Wang, H., Landu, K. & Yoon, J. H. Response of Indian summer monsoon rainfall to remote carbonaceous aerosols at short time scales: teleconnections and feedbacks. Environ. Res. 214, 113898 (2022).

Li, B. & Murtugudde, R. CMIP6 models underestimate rainfall trend on south asian monsoon edge tied to Middle East Warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109703 (2024).

Hagos, S., Leung, L. R., Ashfaq, M. & Balaguru, K. South Asian monsoon precipitation in CMIP5: a link between inter-model spread and the representations of tropical convection. Clim. Dyn. 52, 1049–1061 (2019).

Trenberth, K. E., Stepaniak, D. P. & Caron, J. M. The global monsoon as seen through the divergent atmospheric circulation. J. Clim. 13, 3969–3993 (2000).

Ferraro, A. J., Highwood, E. J. & Charlton-Perez, A. J. Stratospheric heating by potential geoengineering aerosols. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L24706 (2011).

Richter, J. H. et al. Stratospheric response in the first geoengineering simulation meeting multiple surface climate objectives. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 5762–5782 (2018).

Stenchikov, G. L. et al. Radiative forcing from the 1991 Mount Pinatubo volcanic eruption. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 103, 13837–13857 (1998).

Robock, A. Volcanic eruptions and climate. Rev. Geophys. 38, 191–219 (2000).

Ammann, C. M., Washington, W. M., Meehl, G. A., Buja, L. & Teng, H. Climate engineering through artificial enhancement of natural forcings: magnitudes and implied consequences. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, 22109 (2010).

Cheng, W. et al. Changes in Hadley circulation and intertropical convergence zone under strategic stratospheric aerosol geoengineering. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 32 (2022).

Joseph, P. V. & Srinivasan, J. Rossby waves in May and the Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Tellus Ser. A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 51, 854–864 (1999).

Chakraborty, A., Nanjundiah, R. S. & Srinivasan, J. Local and remote impacts of direct aerosol forcing on Asian monsoon. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 2108–2121 (2014).

Jain, S. & Scaife, A. A. How extreme could the near term evolution of the Indian Summer Monsoon rainfall be? Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 034009 (2022).

Hu, Z. Z., Wu, R., Kinter, J. L. & Yang, S. Connection of summer rainfall variations in South and East Asia: role of El Niño-southern oscillation. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1279–1289 (2005).

Ding, Q. & Wang, B. Intraseasonal teleconnection between the summer Eurasian wave train and the Indian Monsoon. J. Clim. 20, 3751–3767 (2007).

Kumar, A. H. & Ratnam, M. V. Variability in the UTLS chemical composition during different modes of the Asian Summer Monsoon Anti-cyclone. Atmos. Res. 260, 105700 (2021).

Garfinkel, C. I. & Hartmann, D. L. The influence of the quasi-biennial oscillation on the troposphere in winter in a hierarchy of models. Part I: simplified Dry GCMs. J. Atmos. Sci. 68, 1273–1289 (2011).

Kodera, K., Nasuno, T., Son, S. W., Eguchi, N. & Harada, Y. Influence of the stratospheric QBO on seasonal migration of the convective center across the maritime continent. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn 101, 445–459 (2023).

Vinoj, V. et al. Short-term modulation of Indian summer monsoon rainfall by West Asian dust. Nat. Geosci. 7, 308–313 (2014).

Roxy, M. K. et al. Drying of Indian subcontinent by rapid Indian Ocean warming and a weakening land-sea thermal gradient. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–10 (2015).

Vidya, P. J., Ravichandran, M., Subeesh, M. P., Chatterjee, S. & Nuncio, M. Global warming hiatus contributed weakening of the Mascarene High in the Southern Indian Ocean. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–9 (2020).

Hartmann, D. L. & Larson, K. An important constraint on tropical cloud–climate feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 12-1 (2002).

Li, P. et al. The diurnal cycle of East Asian summer monsoon precipitation simulated by the Met Office Unified Model at convection-permitting scales. Clim. Dyn. 55, 131–151 (2020).

Tang, X. & Chen, B. Cloud types associated with the Asian summer monsoons as determined from MODIS/TERRA measurements and a comparison with surface observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, 7 (2006).

Schneider, T., Kaul, C. M. & Pressel, K. G. Solar geoengineering may not prevent strong warming from direct effects of CO2 on stratocumulus cloud cover. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 30179–30185 (2020).

Russotto, R. D. & Ackerman, T. P. Changes in clouds and thermodynamics under solar geoengineering and implications for required solar reduction. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 18, 11905–11925 (2018).

Boucher, O., Kleinschmitt, C. & Myhre, G. Quasi-additivity of the radiative effects of marine cloud brightening and stratospheric sulfate aerosol injection. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 158–11,165 (2017).

Saint-Lu, M., Bony, S. & Dufresne, J. L. Clear-sky control of anvils in response to increased CO2 or surface warming or volcanic eruptions. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 1–8 (2022).

Lau, W. K. M. The aerosol-monsoon climate system of Asia: a new paradigm. J. Meteorol. Res. 30, 1–11 (2016).

Jin, Q., Wei, J., Yang, Z. L., Pu, B. & Huang, J. Consistent response of Indian summer monsoon to Middle East dust in observations and simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 9897–9915 (2015).

Zhu, A., Ramanathan, V., Li, F. & Kim, D. Dust plumes over the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic oceans: Climatology and radiative impact. J. Geophys. Res. 112, 16208 (2007).

Das, S., Dey, S., Dash, S. K., Giuliani, G. & Solmon, F. Dust aerosol feedback on the Indian summer monsoon: Sensitivity to absorption property. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 9642–9652 (2015).

Mousavi, S. V. et al. Future dust concentration over the Middle East and North Africa region under global warming and stratospheric aerosol intervention scenarios. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 10677–10695 (2023).

Roxy, M. K. et al. A threefold rise in widespread extreme rain events over central India. Nat. Commun. 2017 81 8, 1–11 (2017).

Goswami, B. N., Venugopal, V., Sengupta, D., Madhusoodanan, M. S. & Xavier, P. K. Increasing trend of extreme rain events over India in a warming environment. Science 314, 1442–1445 (2006).

L, C. C. A multi-model examination of climate extremes in an idealized geoengineering experiment. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 3900–3923 (2014). & others.

Bala, G., Duffy, P. B. & Taylor, K. E. Impact of geoengineering schemes on the global hydrological cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7664–7669 (2008).

Emanuel, K. A. Downscaling CMIP5 climate models shows increased tropical cyclone activity over the 21st century. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 12219–12224 (2013).

Kravitz, B. et al. The Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (GeoMIP6): simulation design and preliminary results. Geosci. Model Dev. 8, 3379–3392 (2015).

Ramanathan, V. et al. Atmospheric brown clouds: Impacts on South Asian climate and hydrological cycle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 5326–5333 (2005).

MacMartin, D. G. et al. Scenarios for modeling solar radiation modification. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2202230119 (2022).

Visioni, D. et al. Identifying the sources of uncertainty in climate model simulations of solar radiation modification with the G6sulfur and G6solar Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project (GeoMIP) simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 10039–10063 (2021).

Henry, M. et al. Comparison of UKESM1 and CESM2 simulations using the same multi-target stratospheric aerosol injection strategy. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 13369–13385 (2023).

Mills, M. J. et al. Radiative and chemical response to interactive stratospheric sulfate aerosols in fully coupled CESM1(WACCM). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 13-061 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. Toward a minimal representation of aerosols in climate models: description and evaluation in the Community Atmosphere Model CAM5. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 709–739 (2012).

Danabasoglu, G. et al. The CCSM4 ocean component. J. Clim. 25, 1361–1389 (2012).

Asutosh, A., Vinoj, V., Landu, K. & Wang, H. Fast response of global monsoon area and precipitation to regional carbonaceous aerosols. Atmos. Res. 304, 107354 (2024).

Fadnavis, S. et al. Tropospheric warming over the northern Indian Ocean caused by South Asian anthropogenic aerosols: possible impact on the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 7179–7191 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank NOAA Climate Program Office Earth’s Radiation Budget Awards 820 Number 03-01-07-001 and NA22OAR4310477. E.M.B. also acknowledges support from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) cooperative agreement NA22OAR4320151 and the Earth’s Radiative Budget (ERB) initiative. The CESM project is supported primarily by the National Science Foundation. This material is based upon work supported by the National Center for Atmospheric Research, which is a major facility sponsored by the NSF under Cooperative Agreement No. 1852977. Computing and data storage resources, including the Cheyenne supercomputer (https://doi.org/10.5065/D6RX99HX), were provided by the Computational and Information Systems Laboratory (CISL) at NCAR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: A.A. and S.T. designed the research; A.A. and S.T. performed the data analysis. A.A., S.T., E.B., and S.F. performed research and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Asutosh, A., Tilmes, S., Bednarz, E.M. et al. South Asian Summer Monsoon under stratospheric aerosol intervention. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 3 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00875-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00875-z

This article is cited by

-

Nonlinear responses of the South Asian High to the Asian tropopause aerosol layer in summer

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Divergent impacts of climate interventions on China’s north-south water divide

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Engineering and logistical concerns add practical limitations to stratospheric aerosol injection strategies

Scientific Reports (2025)