Abstract

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and Tripole (IOT) represent primary modes of interannual variability in the Indian Ocean, impacting both regional and global climate. Unlike the IOD, which is closely related to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), our findings unveil a substantial influence of the Australian Monsoon on the IOT. An anomalously strong Monsoon induces local sea surface temperature (SST) variations via the wind-evaporation-SST mechanism, triggering atmospheric circulation anomalies in the eastern Indian Ocean. These circulation changes lead to changes in oceanic heat transport, facilitating the formation of the IOT. Our analysis reveals a strengthening connection between the Australian Monsoon and the IOT in recent decades, with a projected further strengthening under global warming. This contrasts with the diminished coupling between ENSO and IOD in recent decades from observations and model projections, illustrating evolving Indian Ocean dynamics under the warming climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

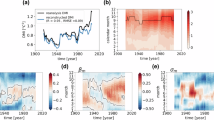

In the tropical Indian Ocean climate system, the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) mode stands out as a fundamental pattern1,2,3. Recent studies further introduce novel concepts such as “unseasonable” IOD4, IOD Modoki5,6, or Indian Ocean Tripole (IOT) modes7,8, which we henceforth collectively refer to as the IOT. The IOD and IOT are delineated by the second and third leading modes of monthly sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the tropical Indian Ocean7,9, accounting for 10.9% and 8.1% of the variance during the period 1970-2023, respectively (see Figs. 1a and 1b). According to North’s test10, the IOD and IOT modes are significantly separated (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Our investigation further reveals that the IOT mode is also captured by the rotated EOF3 (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Additionally, composited SST anomalies, when the third principal component (PC3) time series in boreal summer (July-August-September, JAS) exceeds (or falls below) one standard deviation (Supplementary Fig. 3), exhibit a pattern similar to that of EOF3 pattern (Fig. 1b). IOD and IOT modes exert substantial climate influences over both regional and adjacent areas11,12,13,14,15,16,17. For instance, the IOT events significantly influence the surface air temperature over the western Tibetan Plateau8.

a The leading EOF2 of SST anomalies in the Indian Ocean. b Same as a, but for EOF3. The percentage of variances explained by each EOF mode is shown in the top right panel of (a, b). c SON-mean stream function anomalies regressed onto PC2 during SON. d JAS-mean stream function anomalies regressed onto PC3 during JAS. Dotted areas in (c, d) represent the regression coefficients above the 95% confidence level (Student’s t test). e Lead/lag correlations between DJF Niño 3.4 index and IOD/IOT. f Lead/lag correlations between the JJA AM index and IOD/IOT. Blue and red lines denote IOD and IOT events, respectively in e and f. Brown lines indicate the 95% confidence level (Student’s t test) in (e, f).

Our understanding of the IOD and IOT modes delineates three pivotal distinctions. Firstly, they have distinctive spatial structures and temporal evolutions. The positive (negative) IOD mode is characterized by warm (cold) SST anomalies in the central to western tropical Indian Ocean and cold (warm) SST anomalies in the southeastern Indian Ocean1,2,3. In contrast, the positive (negative) IOT mode is typified by cooling (warming) in the western and southeastern tropical Indian Ocean (SEIO, 95°-110°E, 12°S-0°), and warming (cooling) in the southcentral Indian Ocean (SCIO, 65°–85°E, 15°S–5°S) (Supplementary Fig. 3)5,6,7,18. Additionally, the intensity of the cooling anomalies in the western Indian Ocean is relatively weaker than the SST anomalies in the SEIO and SCIO18. Furthermore, while the IOD peaks in boreal autumn (September-October-November, SON)19, the IOT matures in boreal summer (JAS)18 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Secondly, they unfold in different periods, with the IOD observed consistently throughout the observational periods and the IOT emerging post-mid-1970s4.

Lastly, the IOD and IOT possess disparate dynamical processes. The IOD and IOT are associated with single-cell and double-cell Walker circulation anomalies in the tropical Indian Ocean, respectively5,6. The dynamical processes of the IOD mode have been extensively studied, with some events linked to intrinsic Indian Ocean variability20,21,22,23,24, and others associated with remote forcing from El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)15,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Notably, different types of ENSO events exert varying impacts on the IOD32,33,34,35. Conversely, IOT events are generally independent of ENSO, further distinguishing them from the IOD4.

Despite various investigations, the specific atmospheric or oceanic processes leading to the IOT remain elusive. This study endeavors to illuminate the triggering mechanisms of IOT and to explore how the triggering mechanisms of both the IOD and IOT may evolve under the influence of global warming.

Results

Distinct triggering factors of IOD and IOT

Figure 1c illustrates the regression pattern of the SON-mean 850hPa stream function against the SON-mean PC2 time series. The regression coefficients reveal prominent basin-wide cyclonic circulation anomalies across both hemispheres of the Pacific Ocean (i.e., negative values of stream function in the Northern hemisphere), juxtaposed with basin-wide anticyclonic circulation anomalies in the Indian Ocean for IOD mode. As suggested by previous studies, the anomalous ascending motion in the Pacific Ocean triggered by El Niño induces descending motion in the Indian Ocean via the Walker circulation25,26,36,37. This interaction results in basin-wide anticyclonic circulation anomalies throughout the Indian Ocean (Fig. 1c), thereby contributing to the development of IOD events. Figure 1d depicts the regression patterns of the JAS-mean 850hPa stream function against PC3 during JAS. Here, we observe that during IOT, a pair of regional anticyclonic circulation anomalies appear in the eastern tropical Indian Ocean, accompanied by cyclonic circulation in the northern Australian region (Fig. 1d). Notably, no significant signals are discernible in the tropical Pacific Ocean. It is hypothesized that the formation of IOT events is intricately related to the cyclonic circulations in the northern Australian region, which may be influenced by the Australian winter monsoon. This monsoon exhibits easterly wind during the boreal summer and westerly wind in the boreal winter (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 1e presents the lead-lag correlation coefficients: Fig. 1e shows the correlations between Niño3.4 and the IOD/IOT indices, while Fig. 1f illustrates the correlation between the Australian Monsoon (AM) and the IOD/IOT indices. The maximum lead-lag correlation between the PC2 (IOD) and Niño3.4 in December-January-February (DJF) occurs when IOD leads the Niño3.4 index by approximately 3-4 months, elucidating the seasonal phase relationship and explaining the peak of IOD events during the SON season (Supplementary Fig. 1b)1,38. In contrast, the correlation coefficients between the PC3 (IOT) and Niño3.4 indices consistently remain below the 95% significance level, except for a near-significant correlation coefficient when the Niño3.4 in DJF leads the IOT index by 5-6 months. However, this significant correlation is transient, lasting only two months, and is inconsistent with the peak phase of IOT events during the JAS season (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Conversely, a significant negative correlation emerges when the AM leads the IOT index by 1-4 months, providing insight into why IOT events peak during JAS and persists in SON (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Notably, the AM exhibits overall weak correlations with IOD events.

To further elucidate the relationship between IOT events and the AM, we employ scatter plots of JAS IOT indices against JJA AM indices. Our analysis reveals a significant correlation coefficient of –0.48 between all IOT events and JJA AM, which increases to –0.67 when considering only positive and negative IOT events exceeding \(\pm\)1 standard deviation (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, 67% and 74% of the dots exceeding \(\pm\)1 standard deviation are situated in the second and fourth quadrants (Fig. 2c). Only two positive IOT events exceed two standard deviations, both are associated with negative AM indices (the red dots in Fig. 2a). For IOT events with intensities greater than \(\pm\)1 standard deviation (the blue and red bots), four of the eight positive IOT events occur alongside negative AM indices, whereas 10 out of the 11 negative IOT events correspond with positive AM indices. Notably, only three out of the eight positive IOT events and three out of eleven negative IOT events are accompanied by SST anomalies exceeding \(\pm\)0.5 °C within the Niño3.4 region (Supplementary Table 1). This finding elucidates the weak correlation between the Niño3.4 index and IOT events (Fig. 1e) while highlighting the AM as the dominant forcing factor for IOT events.

a Scatter plot of JAS IOT index versus JJA AM index in observations. Green, blue and red dots represent absolute IOT values of \(< 1\), 1–2 and \(> 2\) standard deviations, respectively. b Same as a, but for CESM1 preindustrial simulations. Linear fits for all points (green line), absolute IOT values\(> 1\,({blue\; line}){and}\) \(> 2\) (red line) standard deviations along with the corresponding correlation coefficient (R) and p values, are shown. c Ratios of IOT values located in the second and fourth quadrants with different thresholds in observations. The green bar indicates all values, and blue and red bars indicate absolute IOT values of \(> 1\) and \(>\)2 standard deviations, respectively. d Same as (c), but for CESM1 preindustrial simulations. The ratio is calculated based on the formula \({\boldsymbol{Ratio}}=\frac{{{\boldsymbol{Num}}}_{{\boldsymbol{Q}}{\boldsymbol{2}}}{\boldsymbol{+}}{{\boldsymbol{Num}}}_{{\boldsymbol{Q}}{\boldsymbol{4}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{Num}}}_{{\boldsymbol{total}}}}\) See text for the details of the formula.

To augment our understanding and increase the sample size, we use preindustrial simulations from the CESM1 LENS, yielding a correlation coefficient of –0.31 (above 99% significance level) between all IOT events and AM (Fig. 2b). Notably, 60% of the data points are located in the second and fourth quadrants (Fig. 2d). This correlation coefficient rises to –0.46 and –0.76 when focusing on positive and negative IOT events exceeding \(\pm\)1 (blue and red dots in Fig. 2b) and \(\pm\)2 standard deviations (red dots in Fig. 2b), respectively. Additionally, 69% of the data points with intensities surpassing \(\pm\)1 standard deviation and 91% of those exceeding \(\pm\)2 standard deviation are located in the second and fourth quadrants (Fig. 2d). These findings underscore the influence of the AM on stronger IOT events, while weaker IOT events appear to be primarily driven by Indian Ocean internal variability or other factors.

Forcing mechanism of IOT by AM

The correlation pattern of the JAS IOT index with simultaneous Indian Ocean SST and 850hPa wind anomalies is shown in Fig. 3a. The SST anomalies exhibit a tripole distribution across the Indian Ocean basin, characterized by significant cooling anomalies in the SEIO and warming anomalies in the SCIO. Conversely, SST anomalies in the western Indian Ocean appear relatively weak. Concurrent with these oceanic anomalies, an intensified Australian monsoon is observed, coinciding with significant cold SST anomalies in northern Australia (as denoted by the purple box in Fig. 3a). We conduct a correlation analysis between JJA AM and the SST/850hPa wind anomalies during JAS (Fig. 3b), revealing a correlation pattern akin to Fig. 3a. This correspondence underscores the close relationship between AM dynamics and IOT events. To isolate the specific influence of AM from the potential confounding effects of ENSO, we employ a partial correlation analysis excluding the impacts of ENSO (Fig. 3c). The resulting partial correlation pattern (Fig. 3c) closely resembles the correlation pattern in Fig. 3a, b, suggesting that the IOT variability is primarily driven by the AM rather than ENSO.

a Correlation coefficients between IOT in JAS and SST/850hPa wind anomalies in JAS. b Correlation coefficients between the AM index in JJA and SST/850hPa wind anomalies in JAS. c Same as (b), but showing partial correlation with AM index by removing variability associated with the Niño3.4 index. d Same as b, but for latent heat flux anomalies, e Same as b, but for precipitation anomalies. f Same as (b), but for SSH anomalies. Purple boxes delineate the region used to define the AM index, while green and red boxes are employed to establish the IOT index. Dotted areas indicate significance above the 95% confidence level (Student’s t test). All correlations in (b–f) are multiplied by −1.

Notably, significant latent heat flux loss anomalies are evident over northern Australia (Fig. 3d), indicative of the cooling anomalies induced by the intensified AM winds via the wind-evaporation-SST feedback mechanism39. These cooling anomalies further instigate the local negative precipitation anomalies (Fig. 3e), triggering the formation of a pair of anticyclonic circulations in the eastern Indian Ocean through a Gill-type response (Figs. 1d, 3a–c). These anticyclonic circulations generate southeasterly wind anomalies in the SEIO (Fig. 3b, red box) and northeasterly wind anomalies in the SCIO (Fig. 3b, green box). The southeasterly wind anomalies induce offshore currents, leading to upwelling and shallow thermocline in the SEIO (Fig. 3f), thereby causing the cooling in this region. Simultaneously, southeasterly wind transports cooling anomalies from northern Australia to the SEIO. Conversely, northeasterly wind anomalies in the SCIO facilitate the advection of warm climatological water near the equator to this region, promoting warming in the SCIO. Additionally, the anticyclonic circulation in the SCIO induces downwelling anomalies (Fig. 3f), further contributing to the warming observed in the SCIO (Fig. 3b).

To further elucidate the underlying dynamical processes driving IOT events, we conducted a mixed-layer heat budget analysis for the IOT events during JAS. Figure 4 illustrates the difference in composited heat budget terms between positive and negative IOT events, averaged over SEIO and SCIO regions. The analysis identifies the mean current effect and thermocline feedback as dominant contributors to the SST tendency in the SEIO, whereas meridional advective effects and Ekman pumping feedback prevail in the SCIO. Correlation analysis between the AM and the heat budget terms over SEIO and SCIO corroborates these findings (Supplementary Fig. 5), confirming that the observed heat budget dynamics are largely induced by AM variability. The net heat flux plays negligible or negative effects on SST tendencies (Fig. 4), with the formation of IOT events primarily driven by oceanic heat transport. These results collectively underscore the influence of AM on the IOT events, shedding light on the mechanisms driving Indian Ocean interannual variability.

Increasing influences of AM on IOT under global warming

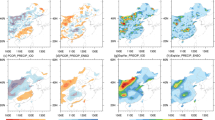

The relationship between IOD and ENSO has undergone decadal changes in recent years, with correlation coefficients exhibiting a decreasing trend in magnitude since the late 1970s16,40,41, consistent with the findings depicted in Fig. 5a. The sliding correlation on a 21-year moving window between the IOD during SON and Niño3.4 index during boreal winter (DJF) (Fig. 5a, depicted by the green line) has continuously declined during 1980-2012, with the correlation coefficients reducing to 0.4 in 2010. Previous studies have proposed that the connection of ENSO-IOD is modulated by the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation41,42. Additionally, other research suggests that the weakening ENSO-IOD relationship may be linked to the earlier onset of the Indian summer monsoon and a decrease in La Niña intensity. Conversely, the 21-year correlation between the IOT and AM exhibits a discernible intensifying trend since the mid-1990s (Fig. 5a, depicted by the purple line), with negative correlation coefficients dropping below –0.65 in 2010. It is hypothesized that the warming climate heightened the influence of the AM on IOT, as warmer climatological SST facilitated the triggering of the Gill-type response43.

a 21-year sliding correlation between the IOD/IOT and Niño3.4/AM in observation (green line shows the correlation between IOD and ENSO, and purple line shows the correlation between IOT and AM). b Correlation coefficients between IOD and Niño3.4 in CMIP6 models. c Same as (b), but for the correlation coefficients between IOT and AM in CMIP6 models. Blue asterisks indicate correlation coefficients significant above the 95% confidence level (Student’s t test) in (b, c). Horizontal lines in MME indicate interquartile ranges between the 25th and 75th percentiles in b and c.

To test this hypothesis, we employ 30 historical runs and SSP585 warming scenarios from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) to examine changes in the linkage between IOD/IOT and ENSO/AM, respectively. Among the 30 models, 20 of them indicate an intensification in the correlation coefficients between IOT and AM in SSP585 scenarios compared to historical runs, consistent with the multi-model mean (Fig. 5c). These results further corroborate observations, suggesting that global warming enhances the influence of AM on IOT. In contrast, results from 19 models demonstrate a weakening correlation between IOD and ENSO in SSP585 scenarios compared to historical runs (Fig. 5b).

To further investigate the factors contributing to the differences in simulating the relationship between AM and IOT events, we categorize the 30 CMIP6 models into two groups: one demonstrating an intensified association between AM and IOT events, and the other not exhibiting such intensification. In the group with an intensified AM-IOT link, the difference in climatological JJA SST between the SSP585 and historical simulation runs ranges from 1.5 °C to 2.25 °C in the north of Australia and southeastern Indian Ocean regions (Supplementary Fig. 6a). In contrast, for the group without such intensification, the difference remains below 1 °C to 2 °C (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Notably, the largest differences in climatological SST between these two groups occur in the southeastern Indian Ocean and north of Australia (Supplementary Fig. 6c). This suggests that higher climatological SSTs in the north of Australia and eastern Indian Ocean support the initiation of IOT events by AM, potentially due to the warmer SST being conducive to triggering the Gill response43.

Discussions

The findings presented in this paper suggest that the triggering mechanisms of IOT events are fundamentally distinct from those of IOD events. While it is well known that the IOD can be forced by ENSO, the IOT shows a weak correlation with ENSO and is primarily influenced by the AM. Anomalously stronger (or weak) winter AM conditions induce local cooling (or warming) through the WES feedback mechanism, initiating a pair of anticyclonic (cyclonic) circulations in the east of the Indian Ocean via the Gill-type response. These circulation patterns result in southeasterly (northwesterly) winds in the SEIO, transporting negative (positive) SST anomalies from the northern Australian region into the SEIO via the mean current effects, thereby inducing cooling (or warming) in this region. Additionally, the northerly (or southerly) wind anomalies associated with AM drive the advection of the climatological warm (cold) SST into the SCIO via the meridional advective effect. The complex interactions between the atmosphere and ocean, including air-sea coupling and dynamical processes, play crucial roles in the formation of positive (or negative) IOT events.

In recent decades, a notable trend has emerged, indicating a strengthening relationship between the AM and IOT. Projections from CMIP6 suggest that this linkage will intensify further in response to ongoing climate warming. This intensification can be attributed to the increased SST to trigger a robust Gill resonse. Conversely, there has been a diminishing association between IOD and ENSO in both recent observations and projected future warming scenarios. Given the evolving nature of these relationships, AM emerges as a more reliable predictor of Indian Ocean interannual variability compared to ENSO. Consequently, increased attention to monitoring and understanding the variability of the AM is imperative. Such efforts hold substantial promise for advancing the prediction of Indian Ocean interannual variations and the subsequent climate impacts associated with these changes. The underlying causes of the declining relationship between the IOD and ENSO remain unsolved and require further investigation in the near future.

Methods

Data

This study investigates the mechanisms triggering IOT events and their associated changes under global warming. The datasets utilized include monthly SST, SSH, 850hPa wind, precipitation, latent heat flux, ocean currents, ocean temperature and net heat flux. The monthly SST reanalysis data is from the Hadley Centre Sea Ice and SST dataset (HadISST), with a horizontal resolution of 1.0° × 1.0°44, covering the period from 1970 to 2023. Monthly 850hPa wind, SLP, and latent heat flux datasets are derived from the National Centers for Environmental Prediction/National Center for Atmospheric Research Reanalysis45 at a horizontal resolution of 2.5° × 2.5°, spanning from 1970 to 2023. Precipitation data are obtained from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) v2.3 with a resolution of 2.5° × 2.5°46, focusing on 1979 to 2023. Monthly SSH, meridional, zonal, vertical currents, net heat flux, and ocean temperature are acquired from the German contribution of the Estimating the Circulation and Climate of the Ocean project with a resolution of 1.0° × 1.0°47, spanning from 1970 to 2018 in this study. All these reanalysis data have been deducted from the seasonal cycles and detrend before analysis.

To expand our analytical scope, we use a 2200-yr preindustrial simulation produced by the Community Earth System Model, version 1 (CESM1)48, focusing on model years 400–2200. Additionally, we examine 30 CMIP6 models, encompassing historical and high emission scenarios (SSP5-8.5) for the period 1950-2014 and 2015-2099, respectively. Thirty CMIP6 models are selected in the study: ACCESS-CM2, BCC-CSM2-MR, CanESM5, CAS-ESM2-0, CESM2-WACCM, CIESM, CMCC-CM2-SR5, CMCC-ESM2, CNRM-CM6-1, CNRM-ESM2-1, E3SM-1-1, FGOALS-f3-L, FGOALS-g3, FIO-ESM-2-0, GFDL-CM4, GFDL-ESM4, GISS-E2-1-G, GISS-E2-1-H, HadGEM3-GC31-LL, INM-CM4-8, INM-CM5-0, MCM-UA-1-0, MIROC6, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, MRI-ESM2-0, NESM3, NorESM2-LM, TaiESM1, UKESM1-0-LL.

Indices

The dipole mode index (DMI) for IOD events is defined as the SST anomaly difference between the tropical western Indian Ocean (50°E–70°E, 10°S–10°N) and the tropical southeastern Indian Ocean (90°E–110°E, 10°S–0)1. The IOT index delineates the SST anomaly differences between two designated areas: the SCIO (65°–85°E, 15°S–5°S) and the SEIO (95°–110°E, 12°S–0°)18. ENSO events are commonly discerned through the Niño3.4 index, which averages SST anomalies over 170°–120°W, 5°S–5°N. The AM index is defined as the 850hPa zonal wind anomalies averaged over 5°S − 15°S and 110°–130°49

To quantify the role of AM in influencing the occurrence percentage of IOT events, we usee the following formula:

Here, \({{Num}}_{Q2}\) represent the numbers of positive IOT events associated with a negative AM index, occurring in the second quadrant. \({{Num}}_{Q4}\) represents the number of negative IOT events associated with a positive AM index, occurring in the fourth quadrant. \({{Num}}_{{total}}\) represents all IOT events that with different thresholds in the observations and CESM1 preindustrial simulations. \(Ratio\) denotes the percentage of IOT events that fall within the second and fourth quadrants out of all IOT events.

EOF, REOF, correlation, sliding correlation, partial correlation, regression, composite analysis, and mixed layer heat budget analysis are performed in this study

We conduct empirical orthogonal function (EOF) and rotated EOF analyses to the monthly SST anomalies over the Indian Ocean domain (40°E–120°E, 20°S– 20°N). To exclude ENSO impacts and achieve the “pure” relationship between the IOT and AM, we applied a partial correlation analysis.

where A, B, and C represent the three variables: IOT index, AM index, and the Niño3.4 index, respectively. R denotes the correlation coefficient, and \({R}_{{AB},C}\) for partial correlation coefficient between the variable A (IOT index) and B (AM index), after the influence of C (Niño3.4) is removed from B.

Significance tests

The statistical significance of the correlations and regressions was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t test.

Mixed layer heat budget analysis is based on the following equation50,51

Here, \(T\), \(u\), \(v\), \(w\) present SST, zonal, meridional and vertical current velocities respectively. \(Q\) denotes the net heat flux into the ocean, and \(\varepsilon\) represents the residual term contributed by the subgrid-scale processes. \(H\) signifies the mixed layer depth defined as the depth where the temperature deviates by 0.5°C from the surface temperature52. \(\rho =1022.4{kg}/{m}^{3}\) is the density of seawater, and \({C}_{p}=3940J/{kg}/^{\circ} {\rm{C}}\) is the heat capacity of seawater. Overbar and prime indicate the climatological mean and anomalies, respectively.

On the right-hand side of the equation, besides the net heat flux (\(Q\)) and residual (\(R\)), the remaining terms could be categorized into six feedback processes: zonal advective feedback (ZA), the meridional advective effect (VA), the Ekman pumping feedback (EK), mean current effect (MA), the thermocline feedback (TH) and nonlinear dynamical heating (NDH).

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in the current study are publicly available and can be downloaded from the corresponding websites. The HadISSTv1.1 data is obtained from the Met Office Hadley Center archives at http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/ hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html. NCEP/NCAR reanalysis data for monthly zonal and meridional wind at 850hPa and heat flux dataset are available at http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/. The SSH, ocean temperature, current and net heat flux used in the heat budget analysis from GECCO3 are available from http://icdc.cen.uni-hamburg.de/projekte/easy-init/easy-init-ocean.html. GPCP version 2.3 are downloaded from https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/ data.gpcp.html. The 2200-year CESM1 simulation is available via the Earth System Grid at https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/projects/community-projects/LENS/data-sets.html. CMIP6 model outputs are publicly available at https://esgf‐node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Saji, N. H., Goswami, B. N., Vinayachandran, P. N. & Yamagata, T. A dipole mode in the tropical Indian Ocean. Nature 401, 360–363 (1999).

Behera, S. K., Krishnan, R. & Yamagata, T. Unusual ocean-atmosphere conditions in the tropical Indian Ocean during 1994. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 3001–3004 (1999).

Webster, PeterJ., Moore, AndrewM., Loschnigg, JohannesP. & Leben, RobertR. Coupled ocean-atmosphere dynamics in the Indian Ocean during 1997-98. Nature 401, 356–360 (1999).

Du, Y., Cai, W. & Wu, Y. A new type of the indian ocean dipole since the mid-1970s. J. Clim. 26, 959–972 (2013).

Endo, S. & Tozuka, T. Two flavors of the Indian Ocean Dipole. Clim. Dyn. 46, 3371–3385 (2016).

Tozuka, T., Endo, S. & Yamagata, T. Anomalous Walker circulations associated with two flavors of the Indian Ocean Dipole. Geopys. Res. Lett. 43, 5378–5384 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Indian Ocean tripole mode and its associated atmospheric and oceanic processes. Clim. Dyn. 55, 1367–1383 (2020).

Zhu, M. et al. Physical connection between the tropical Indian Ocean tripole and western Tibetan Plateau surface air temperature during boreal summer. Clim. Dyn. 62, 9703–9718 (2024).

Pillai, P. A. Recent changes in the prominent modes of Indian Ocean dipole in response to the tropical Pacific Ocean SST patterns. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 138, 941–951 (2019).

North, G. R., Bell, T. L. & Cahalan, R. F. Sampling errors in the estimation of empirical orthogonal functions. Mon. Weather Rev. 110, 699–706 (1982).

Zhang, L. & Han, W. Indian Ocean Dipole leads to Atlantic Niño. Nat. Commun. 12, 5952 (2021).

Ashok, K., Guan, Z. & Yamagata, T. Impact of the Indian Ocean dipole on the relationship between the Indian monsoon rainfall and ENSO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 4499–4502 (2001).

Manatsa, D., Chingombe, W. & Matarira, C. H. The impact of the positive Indian Ocean dipole on Zimbabwe droughts Tropical climate is understood to be dominated by. Int. J. Climatol. 2029, 2011–2029 (2008).

Kurniadi, A., Weller, E., Min, S. K. & Seong, M. G. Independent ENSO and IOD impacts on rainfall extremes over Indonesia. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 3640–3656 (2021).

Xiao, H. M., Lo, M. H. & Yu, J. Y. The increased frequency of combined El Niño and positive IOD events since 1965s and its impacts on maritime continent hydroclimates. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–10 (2022).

Li, Z., Cai, W. & Lin, X. Dynamics of changing impacts of tropical Indo-Pacific variability on Indian and Australian rainfall. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–7 (2016).

Ashok, K., Guan, Z. & Yamagata, T. Influence of the Indian Ocean Dipole on the Australian winter rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 3–6 (2003).

Zhang, G. et al. Attributing interdecadal variations of southern tropical Indian Ocean dipole mode to rhythms of Bjerknes feedback intensity. Clim. Dyn. 62, 3841–3857 (2024).

Feng, L. et al. On the second-year warming in late 2019 over the tropical Pacific and its attribution to an Indian Ocean dipole event. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 2153–2166 (2021).

Ashok, K., Guan, Z. & Yamagata, T. A look at the relationship between the ENSO and the Indian Ocean Dipole. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 81, 41–56 (2003).

Prasad, T. G. & McClean, J. L. Mechanisms for anomalous warming in the western Indian Ocean during dipole mode events. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 109, 1–18 (2004).

Fischer, A. S., Terray, P., Guilyardi, E., Gualdi, S. & Delecluse, P. Two independent triggers for the Indian Ocean dipole/zonal mode in a coupled GCM. J. Clim. 18, 3428–3449 (2005).

Lu, B. & Ren, H. L. What caused the extreme Indian Ocean dipole event in 2019? Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, 1–8 (2020).

Lau, N. C. & Nath, M. J. Coupled GCM simulation of atmosphere-ocean variability associated with zonally asymmetric SST changes in the tropical Indian Ocean. J. Clim. 17, 245–265 (2004).

Ueda, H. & Matsumoto, J. A possible triggering process of east-west asymmetric anomalies over the Indian Ocean in relation to 1997/98 El Niño. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 78, 803–818 (2000).

Baquero-Bernal, A., Latif, M. & Legutke, S. On dipolelike variability of sea surface temperature in the tropical Indian Ocean. J. Clim. 15, 1358–1368 (2002).

Yu, J.-Y., Mechoso, C. R., McWilliams, J. C. & Arakawa, A. Impacts of the Indian Ocean on ENSO. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 85, 1992–1995 (2004).

Krishnamurthy, V. & Kirtman, B. P. Variability of the Indian Ocean: Relation to monsoon and ENSO. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 129, 1623–1646 (2003).

Cai, W., Sullivan, A. & Cowan, T. Interactions of ENSO, the IOD, and the SAM in CMIP3 models. J. Clim. 24, 1688–1704 (2011).

Sang, Y. F., Singh, V. P. & Xu, K. Evolution of IOD-ENSO relationship at multiple time scales. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 136, 1303–1309 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Diverse impacts of Indian Ocean Dipole on El Niño-Southern Oscillation. J. Clim. 32, 1–46 (2021).

Wang, X. & Wang, C. Different impacts of various El Niño events on the Indian Ocean Dipole. Clim. Dyn. 42, 991–1005 (2014).

Fan, L., Liu, Q., Wang, C. & Guo, F. Indian Ocean Dipole modes associated with different types of ENSO development. J. Clim. 30, 2233–2249 (2017).

Liu, L. et al. Why was the Indian Ocean Dipole weak in the context of the extreme El Niño in 2015? J. Clim. 30, 4755–4761 (2017).

Chen, M., Yu, J. Y., Wang, X. & Jiang, W. The changing impact mechanisms of a diverse El Niño on the Western Pacific Subtropical High. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 953–962 (2019).

Krishnamurthy, V. & Goswami, B. N. Indian monsoon-ENSO relationship on interdecadal timescale. J. Clim. 13, 579–595 (2000).

Annamalai, H., Liu, P. & Xie, S. P. Southwest Indian Ocean SST variability: Its local effect and remote influence on Asian monsoons. J. Clim. 18, 4150–4167 (2005).

Cai, W. et al. Projected response of the Indian Ocean Dipole to greenhouse warming. Nat. Geosci. 6, 999–1007 (2013).

Xie, S.-P. & Philander, S. G. H. A coupled ocean-atmosphere model of relevance to the ITCZ in the eastern Pacific. Tellus, Ser. A 46A, 340–350 (1994).

Ham, Y. G., Choi, J. Y. & Kug, J. S. The weakening of the ENSO–Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) coupling strength in recent decades. Clim. Dyn. 49, 249–261 (2017).

Xue, J., Luo, J. J., Zhang, W. & Yamagata, T. ENSO-IOD inter-basin connection is controlled by the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, 1–11 (2022).

Lin, Y. F. & Yu, J. Y. The role of the Indian Ocean in controlling the formation of multiyear El Niños through subtropical ENSO dynamics. J. Clim. 37, 385–401 (2024).

Fang, S. W. & Yu, J. Y. A control of ENSO transition complexity by tropical Pacific mean SSTs through tropical-subtropical interaction. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, 1–9 (2020).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108 (2003).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis Project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 437–471 (1996).

Al, A. E. T. The version-2 Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) monthly precipitation analysis (1979-present). J. Hydrometeorol. 4, 1147–1167 (2003).

Köhl, A. Evaluation of the GECCO2 ocean synthesis: transports of volume, heat and freshwater in the Atlantic. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 141, 166–181 (2015).

Kay, J. E. et al. The Community Earth System Model (CESM) large ensemble project: a community resource for studying climate change in the presence of internal climate variability. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 1333–1349 (2015).

Kajikawa, Y., Wang, B. & Yang, J. A multi-time scale Australian monsoon index. Int. J. Climatol. 30, 1114–1120 (2010).

Jin, F., An, S., Timmermann, A. & Zhao, J. Strong El Niño events and nonlinear dynamical heating. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1–4 (2003).

Zhu, J. & Kumar, A. Influence of surface nudging on climatological mean and ENSO feedbacks in a coupled model. Clim. Dyn. 50, 571–586 (2018).

Sprintall, J. & Tomczak, M. Evidence of the Barrier Layer in the Surface Layer of the Tropics. J. Geophys. Res. 97, 7305–7316 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 41925024 and 42330404), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFF0805300). M. Chen was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42006030 and 42275035), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515012145), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou China (2024A04J3880), development fund of South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (SCSIO202203) and the China Scholarship Council. L. Zhang was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42376021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Chen conceived the research, conducted all the analyses, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. M. Collins, J.-Y. Yu, and X. Wang contributed to interpreting the results, discussing findings and revising the manuscript. L. Zhang and C.-Y. Tam revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, M., Collins, M., Yu, JY. et al. Emerging influence of the Australian Monsoon on Indian Ocean interannual variability in a warming climate. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 319 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00879-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00879-9