Abstract

Accurately estimating particulate organic nitrate under high NOx and oxidizing conditions is critical. This study compared the NOx+ ratio, unconstrained Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF), and Multilinear Engine-2 (ME2) methods to estimate particulate organic nitrate in Shanghai across different seasons. The factors associated with organic nitrate, as identified through two receptor methods, exhibited consistent daily patterns in spring, summer, and autumn, although source contributions varied. The NOx+ ratio method reported higher organic nitrate levels than the PMF and ME2 methods, likely due to the fixed RON/RAN parameter. Seasonal RON/RAN parameters were optimized based on precursor emissions in Shanghai, achieving values of 3.13 in spring, 2.25 in summer, and 1.88 in autumn. This optimization reduced discrepancies in organic nitrate using the NOx+ ratio to 3.2–7.4%. The optimized parameters in this study support the rapid and accurate estimation of organic nitrate during different seasons in urban areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gas-phase organic nitrate, represented as RONO2, are formed through the oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) by atmospheric reactive species, such as NO3 radicals, OH radicals, and ozone (O3), in the presence of NOx in the atmosphere1. During the daytime, alkanes and alkenes react with NOx and OH radicals, and at night with NO3 radicals, to form gas-phase organic nitrate2,3,4. Partial gas-phase organic nitrate species can undergo gas-particle partitioning or further oxidation to become particle-phase species5. Particulate organic nitrate is important atmospheric constituent because of its effects on nitrogen cycling, O3 production, and organic aerosol (OA) formation6. It is worth noting that organic nitrate specifically refers to the nitrate functional group bound within organic molecules in particulate form in this study. This terminology is distinct from general references to organic nitrate compounds in the literature.

The lack of effective instruments for analyzing and quantifying organic nitrate limited understanding of their chemical properties in the past7. In recent years, particulate organic nitrate in particular has been quantified through the development and application of mass spectrometry. Aerodyne high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometry (HR-ToF-AMS) utilizes a hard ionization source to obtain high-resolution mass fragmentation, providing a favorable method for organic nitrate estimation; it has been widely applied in the study of organic nitrate. Based on previous studies, the quantification of particulate organic nitrate has been performed using nitrogen oxide positive ions (NOx+ ratio) or positive matrix factorization (PMF) on HR-AMS data1,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

In the NOx+ ratio method, the nitrate functional groups in the particulate phase are ionized as NO+ and NO2+ fragments during mass spectrometry. The NOx+(NO+/NO2+) ratio of the organic nitrate is significantly higher than that of ammonium nitrate1,21,22,23. The difference in the NO+/NO2+ ratios between ammonium nitrate and organic nitrate is used to estimate the mass of the organic nitrates. This method is advantageous because of its simplicity and convenience. Although the NOx+ ratio of the organic nitrate was assumed to be fixed, numerous studies have reported that it varies with instruments, precursor species, and oxidation pathways24,25,26. This greatly increases the difficulty in selecting NO+/NO2+ values, and their selection significantly affects the accuracy of the NOx+ ratio method. PMF is a popular technique for identifying pollution sources and understanding OA formation27,28. The PMF method can effectively distinguish particulate organic nitrate from inorganic nitrate and identify organic factors accordingly17,18,20. Compared with unconstrained PMF, inorganic nitrate can be effectively resolved with less influence from random distribution based on mass spectral profiles for inorganic nitrate as constraints using a constrained PMF, also known as a multilinear engine (ME2)12. However, the bilinear model used in the PMF method (known as the PMF principle) is vulnerable to errors when separating the organic and inorganic nitrate fragments, which can lead to uncertainties in organic nitrate quantification.

Based on AMS observation datasets, a single method was used to quantify organic nitrate concentrations in previous studies. For accuracy, a primary method was supplemented with an additional method for cross-verification12,18. However, the results obtained using these methods remain uncertain. To date, studies comparing and evaluating these three methods are scarce. In this study, three campaigns using HR-ToF-AMS were conducted during spring, summer, and autumn in Shanghai. This study aimed to compare the estimation results of the NOx ratio, unconstrained PMF, and ME2 methods for organic nitrate estimation using the same set of data. The results provide a scientific basis for the applicability of different methods to the estimation of organic nitrate and offer scientific and technical support for the study of organic nitrate variation characteristics.

Results and discussion

Organic nitrate calculation

Figure 1 shows the time resolution of nitrate (NO3–) and NO+/NO2+ ratios measured using AMS. The average measured NO+/NO2+ (Robs) during the spring, summer, and autumn observations were 2.06, 2.57, and 2.65, respectively. The average NO+/NO2+ ratios of pure ammonium nitrate (RAN) during spring, summer, and autumn are shown in Fig. 1. At lower NO3– concentrations, the measured NO+/NO2+ ratio was higher. In autumn, the NO+/NO2+ ratio was as high as 17.1. Notably, the measured NO+/NO2+ ratio at high NO3– concentrations were close to that of pure ammonium nitrate during the pollution episodes observed in spring, summer, and autumn. This may be due to the rapid formation of ammonium nitrate during pollution episodes, with most of the NO+ and NO2+ fragments derived from secondary inorganic ammonium nitrate. RON/RAN = 2.08 was used as the parameter value to semi-quantitatively calculate the mass concentration of particulate organic nitrates (Estimated NO3–,org, as shown in Fig. 2).

The average NO+/NO2+ of pure ammonium nitrate (RAN) is obtained from the three calibrations during the spring (a), summer (b) and autumn (c) observations, respectively, shown in red lines. The yellow circular symbol represents NO+/NO2+ ratios obtained by AMS measurements (Robs) during the spring (a), summer (b) and autumn (c) observations, respectively. The blue plus symbol represents the total mass concentrations of nitrate (NO3−) measured by AMS during three seasonal observations.

Time series of particulate organic nitrates (NO3–,org) are obtained by NOx+(NO+/NO2+) ratio, PMF, and ME2 methods in a spring, b summer, and c autumn in Shanghai. The green circles, yellow boxes, and red lines represent concentrations obtained by the NOx+(NO+/NO2+) ratio, PMF, and ME2 methods in three seasons in Shanghai.

The average mass concentration of particulate organic nitrate (NO3–,org) in spring, summer, and winter was 0.79 ± 0.45, 0.43 ± 0.37, and 0.91 ± 0.80 μg/m3, respectively, reaching up to 3.52, 4.21, and 4.99 μg/m3, respectively. NO3–,org accounted for an average of 8.0%, 3.1%, and 8.7% of OA and 20.4%, 14.5%, and 28.2% of the NO3– during the spring, summer, and autumn periods, respectively. The organic nitrate concentrations estimated by RON/RAN = 1.40 and 3.99 were used as the upper and lower concentration limits, respectively. The average concentrations of the upper limit values for organic nitrate were 1.92 ± 1.10, 1.04 ± 0.91, and 2.23 ± 1.97 μg/m3 in spring, summer, and autumn, respectively, and the lower limit values were 0.28 ± 0.16, 0.15 ± 0.13, and 0.33 ± 0.29 μg/m3, respectively.

Five factors were identified using the unconstrained PMF model, with four being organic factors: cooking OA (COA), hydrocarbon-like OA (HOA), more-oxidized oxygenated OA (MO-OOA), less-oxidized OOA (LO-OOA), and a single inorganic factor (NIA) (Fig. 3). An evaluation of the reliability and stability of the outcomes of the PMF model is presented in Section S2 of the supplementary material. The average NO3– concentration was 3.84 ± 5.70, 2.94 ± 4.88, and 3.23 ± 4.48 μg/m3 during the spring, summer, and autumn periods, respectively. The average values for particulate organic nitrate calculated based on the unconstrained PMF model (PMF_NO3–,org) were 0.32, 0.17, and 0.42 μg/m3 (Table 1), which accounted for as much as 8.3%, 5.8%, and 13.0% of NO3– in spring, summer, and autumn, respectively.

Analyzing the contribution of NOx+ fragments to various factors, 90.5%, 91.2%, and 84.5% were distributed in the NIA factor in spring, summer, and autumn, respectively, whereas the remaining comprised organic factors. Notably, the NIA factor contained 14.4%–36.1% organic fragments due to unconstrained PMF model apportion17. The presence of NOx+ fragments in all four organic factors suggests a diverse source of particulate organic nitrate in Shanghai. The HOA factor characterizes OA from motor vehicle exhaust emissions29,30. In spring and summer, particulate organic nitrate is mainly present in HOA at concentrations of 0.21 and 0.17 μg/m3, respectively, accounting for 5.4% and 5.7% of the average NO3–, respectively. The organic nitrate in MO-OOA contributed significantly to the total organic nitrate by 0.38 μg/m3, contributing 11.7% of NO3–, which was likely relative to regional transport31.

The NIA factor of the pure NOx+ fragments was used as a constraint, and the other four factors were resolved using the ME2 model, which agreed with the PMF model (Fig. 3). The average particulate organic nitrate (ME2_NO3–,org) during the spring, summer, and autumn observations were 0.31 ± 0.21, 0.34 ± 0.29, and 1.01 ± 0.90 μg/m3, respectively, with corresponding contributions of 8%, 11.6%, and 31.2%. As in the PMF results, the contribution of HOA to ME2_NO3–,org was significant among the four organic factors in spring (67.8%; 0.21 μg/m3) and summer (57.9%; 0.22 μg/m3) (Fig. 3). Secondary oxidation during autumn is an important source of particulate organic nitrate. The difference was that the contributions of NO3–,org in the LO-OOA and MO-OOA factors to the total organic nitrate mass were comparable with the highly contributing SOA factors in autumn.

During spring, NO3–,org were resolved by PMF and ME2, resulting in relatively similar factor resolutions. The estimated organic nitrate concentration was higher than that of the two source apportionments. In summer and autumn, the NO3–,org derived from ME2 was consistent with the estimated results. The total amount of PMF resolved was lower than that by the other two methods, especially in autumn (Fig. 2).

Comparison of organic nitrate sources and diurnal variations

Table 1 lists the different sources of organic nitrate resolved using ME2 and PMF. The ME2 and PMF organic nitrate sources differed significantly during summer and autumn. In PMF, most of the organic nitrate mass was attributed to HOA, while ME2 also identified HOA as the primary contributor to organic nitrate, though with varying source attributions across factors in summer. ME2-resolved organic nitrate in HOA accounted for 64.7% of the total organic nitrate on average during the summer observation period. Organic nitrate from COA, LO-OOA, and MO-OOA accounted for a comparable proportion (~12%, 11%, and 19%, respectively) for ME2 resolved in summer (Fig.3).

In summer, the enhanced photochemical reactions due to high temperature and solar radiation, combined with motor vehicle emissions and humidity effects, result in a relatively high contribution of HOA to organic nitrate. Motor vehicle emissions can release significant amounts of nitrophenols, which can undergo further oxidation to form particle-phase organic nitrate32. The organic nitrate exists in diverse forms in the atmosphere owing to their wide range of saturated vapor pressures. During the highly oxidizing conditions in summer, a portion of particle-phase organic nitrate originates from the gas-phase oxidative production of VOCs, hydroxyl radicals (OH), and nitrogen oxides33. Subsequently, the organic nitrate undergoes additional oxidation processes and are transformed into MO-OOA. This phenomenon was observed in diurnal variations (Fig. S1). Organic nitrate contribution from HOA was high during the 6:00-7:00 morning rush hour. During certain times of the day, especially under high photochemical activity (typically 10:00-16:00), the oxidation processes intensified due to increased sunlight and temperature in summer. This leaded to more significant organic nitrate formation in LO-OOA through reaction with NOx. The high humidity conditions at night in summer promoted the formation of MO-OOA. After 16:00, there was a continued increase in the organic nitrate within MO-OOA, potentially attributable to the further oxidation of organic nitrate during the formation of MO-OOA. Meanwhile, OOA contributed up to 60% of the total OA amount according to the source apportionment for OA, and MO-OOA was highly correlated with sulfate (Fig.S6 and Fig.S9). PMF_NO3–,org showed a two-fold reduction compared to concentrations of organic nitrate resolved by ME2 during the summer season (Table 1), mainly because of the failure to distribute organic nitrate well from factors other than HOA in summer. This was verified by the spectral analysis provided in the Comparison of organic nitrate spectra section, which outlines that NIA factor resolved by the summer PMF contained some organic fragments, leading to an underestimation of organic nitrate.

During the autumn observation period, PMF-resolved organic nitrate was mainly distributed in MO-OOA, which accounted for 90% of the total organic nitrate. ME2-resolved organic nitrate was predominantly found in OOA, with a majority composition of 62% in LO-OOA and 38% in MO-OOA (Fig.3). In autumn, the influence of regional transport and biomass burning emissions, along with the enhanced formation of organic nitrate in OOA, leads to a significant reduction in the contribution of HOA. The formation of particle-phase organic nitrate in OOA followed a distinct pathway. The organic nitrate present in LO-OOA exhibited semi-volatile and low-oxidizing characteristics, suggesting a localized origin. However, the organic nitrate found in MO-OOA was more likely to be generated on a regional scale27,34. The combination of high NOx emissions and reactive VOCs in Shanghai, especially during periods of intense photochemistry, promoted the formation of organic nitrate. Unlike in other seasons, the photochemical reaction process contributed to the formation of MO-OOA in autumn, and improved the oxidation of OA. Further oxidation occurred after the generation of organic nitrates in autumn under high oxidation conditions. The higher oxidation levels contributed significantly to organic nitrate formation. Besides, regional transport can also enhance nitrate incorporation. Source apportionment of OA during the autumn observation period indicated that both LO-OOA and MO-OOA contributed equally, accounting for 28% each of the total OA35. The proportion of MO-OOA in the OA was higher in autumn than in other seasons, reflecting the possible presence of aged organic nitrate that have been transported through the region. Despite the prevalence of organic nitrate in OOA for PMF resolution in autumn, the assignment of organic nitrate to LO-OOA and MO-OOA using ME2 model provide a more accurate reflection of the chemical composition and oxidation state of organic aerosols observed in autumn.

To verify the accuracy of the resolved results, we compared the diurnal profiles of organic nitrate from various sources obtained using the two receptor models. Throughout the observation seasons, the diurnal variations in organic nitrate within HOA, COA, LO-OOA, and MO-OOA, as determined by PMF and ME2, exhibited a high level of concordance, indicating the robustness and reliability of the findings (Fig. S1).

Comparison of organic nitrate spectra

The NO+/NO2+ ratios in the NIA factors obtained from the PMF resolution during the spring, summer, and autumn observations were 1.35, 0.95, and 1.41, respectively. The NO+/NO2+ in the NIA factors was slightly higher than that of the pure substance NH4NO3 in spring (1.25) and autumn (1.20), and lower than that of the pure substance by 26.3% in summer (1.22), as shown in Fig.1. The total proportions of NO and NO2 fragments in NIA_PMF in spring, summer, and autumn were 85.6%, 63.9%, and 82.7%, respectively (Fig. 4). This implies that the PMF method can accurately derive the NIA factor from the mass spectra during spring and autumn observations. In contrast, the summer NIA factor contained a portion of organic fragments, which resulted in the underestimation of PMF_NO3–,org. During the spring, summer, and autumn observations, the NO+/NO2+ ratios in the NIA factors resolved using ME2 were 1.34, 1.19, and 1.50, respectively. Although the ME2 model constrains the NIA profile, seasonal variations in ambient atmospheric conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity, and oxidant levels) and the mixed nature of real-world aerosol sources can lead to slight seasonal variations in the NO+/NO2+ratios observed within the NIA factor. In spring, the NO+/NO2+ ratios of the NIA factors resolved using ME2 and PMF were comparable. In summer, the NO+/NO2+ ratio in the NIA_ME2 factor was comparable to that of pure NH4NO3. In autumn, the NO+/NO2+ in NIA obtained from ME2 resolution was higher than that from PMF by 6%.

The organic factors from different sources and inorganic nitrates (NIA) based on ME2 and PMF resolution are shown in a spring, b summer, and c autumn in Shanghai. The organic aerosol factors, namely the MO-OOA, LO-OOA, HOA and COA factors are resolved by PMF and ME2 models. The mass spectra obtained with the ME2 model for the different factors are identified by various colors. The different factors of PMF are in black, compared with the mass spectra of the different factors resolved by ME2.

The contribution of organic nitrate from HOA was significant in both the PMF- and ME2-resolved results during spring and summer (Fig.3). However, the similarity angles of the HOA spectra between the PMF and ME2 during the spring and summer observations were 14.3° and 16.9° (Table 2), respectively, indicating that the PMF- and ME2-based HOA spectra were similar (Fig.4). For HOA, the contribution of NO+ ions to the PMF and ME2 source spectra was prominent during the spring and summer observation periods, with 0.1% of the ion fragments (Fig.4). However, for example, the PMF-resolved HOA in summer had a NO+/NO2+ ratio of 0.066, while the ME2-resolved HOA had a NO+/NO2+ ratio of 3.88, which is comparable to that of particulate organic nitrate from the photooxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons36.

In autumn, both PMF and ME2 resolved OOA contributed prominently to the organic nitrate. The organic nitrate in MO-OOA, which was resolved using ME2 and PMF, was highly consistent. However, the similarity angle between the MO-OOA source spectra for the PMF and ME2 models was 14.5°. Comparing the NO/NO2 in the MO-OOA spectra, the NO+/NO2+ (5.0) ratio for the ME2 method was closer to the ratio of organic nitrate obtained from a laboratory simulation study24. Based on the characteristics of the source spectra obtained in spring, summer, and autumn, ME2 resolves organic nitrate better than PMF.

Parameter optimization analysis for ratio method

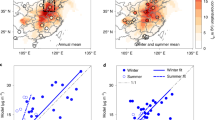

The ratio method was applied to the calculation of NO3–,org based on the empirical parameter RON, which was based on laboratory simulations of some types of particulate organic nitrate and is unrepresentative of all organic nitrate types. With changes in pollution, meteorological conditions, and other factors, the types of organic nitrate products also varied37. The single-parameter RON cannot reflect the changes in the reaction product species in all seasons5,14. Thus, the concentrations of organic nitrate calculated based on the NOx+ ratio method differed from the ME2 resolution results in different seasons. A comparison of the two estimation methods revealed that the NO3–,org values obtained differed slightly and correlated well during the summer and autumn observation periods (Fig. 5), suggesting that the empirical parameter RON ( = 2.08 RAN) is a good representation of the organic nitrate product species in summer and autumn. In contrast, in spring, although the organic nitrate estimated using the ratio method correlated better with those estimated using the ME2 method, with R2 values of 0.78, the discrepancies between the two results were large. The results of the ratio-based method were 53.2% higher than those of the ME2 method.

The correlation between organic nitrate is obtained by NOx+ ratio method as well as ME2 methods in a spring, b summer, and c autumn in Shanghai. The pink line indicates the linear fit of the organic nitrate calculated by the NOx+ ratio method using the initial parameter RON/RAN = 2.08 in the ME2 results. The purple line represents the linear fit of the organic nitrate calculated by the NOX+ ratio method after using the optimized parameters in the ME2 results. During spring, summer and autumn, the optimized parameter RON/RAN were 3.13, 2.25 and 1.88, respectively. The formulas and R2 values presented in pink and purple colors correspond to the fitting results of organic nitrates calculated by the ratio method based on the original and optimized parameters and those resolved by ME2 model, respectively.

In this study, an attempt was made to calculate the appropriate range of values of RON in Shanghai in all seasons to reflect the variations in organic nitrate product species in the particulate phase in different seasons. The results of the ME2 method were fixed to calculate a reasonable range of RON (Fig. 5). In this study, aromatic hydrocarbons were used as important precursors of particle-phase organic nitrate in Shanghai. Therefore, the RON/RAN parameters for spring, summer, and autumn were initially chosen to be 2.08. RON/RAN parameter were re-estimated from the correlation of organic nitrate between ratio method and ME2 results. In spring, the RON/RAN ratio estimated from the ME2 results averaged at 3.44. This was higher than the RON/RAN for aromatic hydrocarbons, the value of 2.08 used in our calculations. The contribution of other precursor species reactions to organic nitrate would require consideration in spring. Naturally emitted terpenes are volatile organic compounds with an aroma that are mainly secreted from forest trees, flowers, and grasses38. Although biogenic sources are not the primary contributor to urban pollution in Shanghai, they exert a quantifiable influence39,40, particularly in transitional seasons like spring when moderate temperatures and active vegetation enhance biogenic emissions. β-Pinene was selected as a representative biogenic precursor because of its reactivity and documented contribution to organic nitrate formation under specific conditions. β-pinene and NO3 radical oxidation to generate organic nitrate had a RON/RAN of 3.17–4.1725. In spring, we used β-pinene and aromatic hydrocarbons as precursors for organic nitrate mixing to capture both biogenic and anthropogenic influences. By considering the RON/RAN parameter, a scenario where urban organic nitrate formation results from both anthropogenic sources and biogenic emissions were characterized. The final RON/RAN parameter used in the calculations was the average of the parameter values (3.13) for the generation of particle-phase organic nitrate from the two precursors of β-pinene (RON/RAN = 4.17) and aromatic hydrocarbons (RON/RAN = 2.08). The estimates based on the parameter adjustments were comparable to ME2, with a deviation of only 7.4% in spring.

In summer, the ME2 results estimated the average RON/RAN ratio to be 2.28, which was higher than the original calculation value (2.08). High temperatures and strong solar radiation can lead to rapid chemical reactions of unsaturated carboxylic acids emitted from motor vehicles during the summertime41,42. Therefore, the chemical reaction of unsaturated carboxylic acids other than aromatic hydrocarbons with NO3 (RON/RAN = 2.08) was integrated in this study. The parameter RON/RAN was increased to 2.25, a value based on standards synthesized in an environmental chamber experiment. In this experiment, oleic acid particles were reacted with NO3 radicals to simulate organic nitrate formation under controlled conditions. The experiments were conducted by introducing oleic acid aerosol into a chamber with NO3 radicals. The particle-phase organic nitrate was then analyzed to establish a representative RON/RAN value of 2.25. Estimates from the adjusted ratio method in summer were consistent with ME2, with the difference decreasing to 3.3%.

In autumn, the findings from the ME2 analysis indicated that the average RON/RAN ratio was estimated to be 1.80. Biomass burning emissions from surrounding regions substantially elevated organic aerosol concentrations in Shanghai40,43. While the factor from biomass burning emissions was not resolved as a standalone factor in autumn, the MO-OOA and LO-OOA factors in our results likely encompassed aged aerosols that may derived from biomass-related VOCs. Recent studies indicate that transported wildfire plumes lead to significant oxidation of BBOA during atmospheric aging, making its mass spectra resemble LO-OOA44. In addition, biomass burning aerosols can be rapidly oxidized to form a significant proportion of LO-OOA45. Given indirect effects, we included biomass burning-related precursors in the autumn RON/RAN parameter estimation to reflect the potential influence of regional biomass burning emissions on organic nitrate formation. 3-Methylfuran is an important tracer in biomass combustion plumes and yields organic nitrate via NO3 oxidation reactions26,46,47,48. In autumn, owing to the influence of biomass burning, we considered RON/RAN ( = 1.40) for the generation of organic nitrate by combining the reaction of 3-Methylfuran and NO3 radicals. Besides, increased biomass burning and dry, warm conditions enhance isoprene concentrations, establishing it as a critical precursor of organic nitrate during the autumn season49,50. The average value of RON/RAN of 1.88, was finally adopted for the oxidation of the three precursors to generate organic nitrate in the particulate phase, when considering the combined oxidation of isoprene (2.16), 3-Methylfuran (1.40), and aromatic hydrocarbons (2.08). The adjusted parameterized ratio method estimated slightly lower values of organic nitrate than the ME2 method, with a discrepancy of 3.2%. These results imply that the NOx+ ratios for organic nitrate generation in the particulate phase were higher than those for aromatic hydrocarbons during spring and summer and lower in autumn. Therefore, the suitability of the RON/RAN values in various seasons must be considered when using the ratio method to enhance its applicability.

Atmospheric implications

The present study was conducted to compare various estimation methods and optimize organic nitrate parameters in Shanghai during the spring, summer, and autumn. The NOx+ ratio, unconstrained PMF, and ME2 methods are three widely used methods for estimating organic nitrate based on the AMS high-temporal-resolution mass spectrometry dataset. To date, a comparison of the estimations based on the three methods, as well as improvements, is still lacking. In this study, we analyzed the total mass, diurnal variation, and spectral characteristics of organic nitrate obtained using three estimation methods based on AMS seasonal observation data in Shanghai. We found that the three methods agreed differently with each other in the total quantities in spring, summer, and autumn. This implies that evaluating the applicability of methods based solely on observations during a certain season may lead to limitations in the analysis. In the future, comparisons of method evaluations should be conducted using data from more diverse regional areas of the AMS.

For the analysis of sources, diurnal variations, and spectral feature ion fragmentation ratios, the diurnal variations in organic nitrate obtained using the three methods during the same season were in good agreement, but their source assignments varied significantly. Based on the source resolution of OA and comparison of mass spectrometry characteristic ions, we verified that organic nitrate resolved by the ME2 method, which limits inorganic nitrate, was preferred to that resolved by the PMF method. Notably, RON/RAN is an important parameter for estimating organic nitrate. A single RON cannot accommodate the variations in the reaction product species in any season. In this study, based on the precursor emission characteristics of Shanghai for all seasons, we provide seasonal RON/RAN parameters to optimize the NOx+ ratio method. The organic nitrate concentrations obtained using the optimized NOx+ ratio method correlated well with the ME2 resolution results, with small deviations. This indicates that the optimized seasonal RON/RAN parameters can be used for the rapid estimation of organic nitrate concentrations in Shanghai during all seasons. In the future, more consideration should be given to different regions in the north and south, where the source difference is more pronounced, as well as to different pollution events and cleaning scenarios.

Methods

Sampling site and measurements

Observations were conducted during three field campaigns at urban sites in Shanghai in spring (18 May–4 June 2017), summer (23 August–10 September 2016), and autumn (7 September–8 October 2017). The spring and summer field campaigns were conducted in situ at the same location, the Shanghai Academy of Environmental Sciences (SAES) (31.10°N, 121.25°E), as described by Zhu et al.35. Autumn observations were conducted at the Jing’An monitoring site (JA), located in the Shanghai Jing’an District Environmental Monitoring Station (31.23°N, 121.43°E). This site is in the center of Shanghai City, surrounded mainly by schools, residential living areas, and some commercial areas, with no obvious local sources. The observation instruments were placed on a 5-story building, ~20 m above ground level. The SAES and JA sites are located in typical mixed residential-commercial districts of Shanghai, which is representative of the typical Shanghai urban area.

In this study, HR-ToF-AMS was employed to measure the compositions of non-refractory aerosols and high-resolution fragments. HR-ToF-AMS was performed according to standard protocols. The measurement and verification can be found in Zhu et al.35.

Estimation of particulate organic nitrate

Among the various chemical compositions measured by AMS, the mass concentration of nitrate was obtained from the mass spectral signal at mass-to-charge ratios m/z30 (NO+) and m/z46 (NO2+), which can be divided into inorganic (mainly in the form of ammonium nitrate) and organic (in the form of RONO2, where R denotes the organic group) nitrate. For AMS, the two measured mass spectral signals represent the total mass of nitrate.

The ratio was estimated based on the NO+/NO2+ ratio (Robs) measured using the AMS. The contribution of organic nitrate to the NO+ and NO2+ fragments was calculated by subtracting the contribution of inorganic nitrate. The specific calculations were performed as follows:

where RAN is determined by the NO+/NO2+ ratio of high-purity ammonium nitrate measured by the AMS during ionization efficiency calibration and RON is the NO+/ NO2+ ratio obtained from experimental studies on the gas-phase oxidation of particulate organic nitrate from biogenic or anthropogenic VOCs.

The RON/RAN remain stable for a given precursor5. Based on the six organic nitrate standards measured, the average RON/RAN was 2.251. Previous studies have established that the RON/RAN was 3.7–4.17 for the organic nitrate produced by the oxidation of β-pinene and NO3 radicals, and 2.16 from the photochemical oxidation of isoprene4,23,25. For anthropogenic sources of VOCs, the RON/RAN value of organic nitrate from the photochemical oxidation of aromatics (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, etc.) was close to that of organic nitrate from isoprene, with an RON/RAN of 2.0824. Aromatics are important precursors of particulate organic nitrate in Shanghai. Therefore, 2.08 was considered as the RON/RAN in this study. Furthermore, we used the RON/RAN estimation range of 1.40–3.99 obtained from the reaction of different VOC precursors in literature to estimate the concentration range of organic nitrate12,18. The boundary values in this range represent the upper and lower limits of the organic nitrate concentration estimated using the ratio method.

The PMF method based on the OA data matrix has been widely used for the source analysis of OA51,52. The addition of NO+ and NO2+ fragments to the OA mass spectrometry fragment matrix was key to the AMS_PMF method used for the source apportionment of organic nitrate. Various sources of organic nitrate and single NIA were identified using different OA factors. The calculations are shown as follows19,20:

where [OA factor] i represents the mass concentration of the OA factor i and fNO2,i and fNO, i are the proportions of NO+ and NO2+ in the mass spectrum of the OA factor i, respectively.

Notably, the relative ionization efficiencies (RIE) of the OA and NOx+ fragments were 1.4 and 1.1, respectively. The effect of RIE on the apportionment weights was considered before applying it to the PMF model. The OA matrix was divided by 1.4, and the NOx+ fragment matrix was divided by 1.1.

The NIA factors from the PMF method are linked to contributions from organic fragments17. The NIA factors set as constraints in ME2 were used to eliminate any effect of organic fragments on the NIA factor12. The initial profile of the NIA factor was required, and thus, the fraction was assumed to be NO+ + NO2+ = 1. The NO+/NO2+ for the adopted NIA factor was based on several calibrations. The Source Finder53, which utilizing the α-value approach54, was employed to conduct the ME2 analysis, as described in Zhu et al.55. The calculations for organic nitrate were the same as those for the unconstrained PMF. The parameter α, a scalar ranging from 0 to 1, encompasses both the time-series matrix and the profile matrix. In this study, the NIA factor was constrained within the profile matrix P, with the α value set at 0.5, which is consistent with other literature12. The α-value of 0.5 represents the degree to which the output profiles may deviate from the model inputs. The diagnostic plots and solution choices for PMF and ME2 can be found in Section S2 of the Supplementary Material.

Mass spectra similarity analysis

In this work, the angle θ was employed as a metric to assess the correlation between the two features of the AMS mass spectra.

The angle θ, representing the comparison between the two AMS mass spectra (MSa, MSb), was categorized into ranges of 0°–5°, 5°–10°, 10°–15°, 15°–30°, and >30°, indicating levels of consistency ranging from excellent to poor56.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. The raw datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request (lousr@usst.edu.cn).

References

Farmer, D. et al. Response of an aerosol mass spectrometer to organonitrates and organosulfates and implications for atmospheric chemistry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 6670–6675 (2010).

Ng, N. L. et al. Nitrate radicals and biogenic volatile organic compounds: oxidation, mechanisms, and organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 2103–2162 (2017).

Capouet, M. & Müller, J.-F. A group contribution method for estimating the vapour pressures of α-pinene oxidation products. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 1455–1467 (2006).

Fry, J. et al. Organic nitrate and secondary organic aerosol yield from NO 3 oxidation of β-pinene evaluated using a gas-phase kinetics/aerosol partitioning model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 1431–1449 (2009).

Fry, J. et al. Observations of gas-and aerosol-phase organic nitrates at BEACHON-RoMBAS 2011. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 8585–8605 (2013).

Perring, A., Pusede, S. & Cohen, R. C. An observational perspective on the atmospheric impacts of alkyl and multifunctional nitrates on ozone and secondary organic aerosol. Chem. Rev. 113, 5848–5870 (2013).

Singla, V., Mukherjee, S., Pandithurai, G., Dani, K. K. & Safai, P. D. Evidence of organonitrate formation at a high altitude site, Mahabaleshwar, during the pre-monsoon season. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 19, 1241–1251 (2019).

Sun, Y. et al. Factor analysis of combined organic and inorganic aerosol mass spectra from high resolution aerosol mass spectrometer measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 8537–8551 (2012).

Xu, L., Suresh, S., Guo, H., Weber, R. J. & Ng, N. L. Aerosol characterization over the southeastern United States using high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry: spatial and seasonal variation of aerosol composition and sources with a focus on organic nitrates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 7307–7336 (2015).

Lee, A. K. et al. Substantial secondary organic aerosol formation in a coniferous forest: observations of both day-and nighttime chemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 6721–6733 (2016).

Xu, W. et al. Estimation of particulate organic nitrates from thermodenuder-aerosol mass spectrometer measurements in North China Plain. Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss. 2020, 1–20 (2020).

Ge, D. et al. Characterization of particulate organic nitrates in the Yangtze River Delta, East China, using the time-of-flight aerosol chemical speciation monitor. Atmos. Environ. 272, 118927 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Chemical characterization of secondary organic aerosol at a rural site in the southeastern US: insights from simultaneous high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS) and FIGAERO chemical ionization mass spectrometer (CIMS) measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 8421–8440 (2020).

Dai, Q. et al. Seasonal differences in formation processes of oxidized organic aerosol near Houston, TX. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 9641–9661 (2019).

Kiendler‐Scharr, A. et al. Ubiquity of organic nitrates from nighttime chemistry in the European submicron aerosol. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 7735–7744 (2016).

Huang, W. et al. Exploring the inorganic and organic nitrate aerosol formation regimes at a suburban site on the North China plain. Sci. Total Environ. 768, 144538 (2021).

Yu, K., Zhu, Q., Du, K. & Huang, X.-F. Characterization of nighttime formation of particulate organic nitrates based on high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry in an urban atmosphere in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 5235–5249 (2019).

Zhu, Q. et al. Characterization of organic aerosol at a rural site in the North China plain region: sources, volatility and organonitrates. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 1115–1127 (2021).

Hao, L. et al. Atmospheric submicron aerosol composition and particulate organic nitrate formation in a boreal forestland–urban mixed region. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 13483–13495 (2014).

Xu, L. et al. Effects of anthropogenic emissions on aerosol formation from isoprene and monoterpenes in the southeastern United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 37–42 (2015).

Murphy, J., Day, D., Cleary, P., Wooldridge, P. & Cohen, R. Observations of the diurnal and seasonal trends in nitrogen oxides in the western Sierra Nevada. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 5321–5338 (2006).

Rollins, A. W. et al. Isoprene oxidation by nitrate radical: alkyl nitrate and secondary organic aerosol yields. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 6685–6703 (2009).

Bruns, E. A. et al. Comparison of FTIR and particle mass spectrometry for the measurement of particulate organic nitrates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 1056–1061 (2010).

Sato, K. et al. Mass spectrometric study of secondary organic aerosol formed from the photo-oxidation of aromatic hydrocarbons. Atmos. Environ. 44, 1080–1087 (2010).

Boyd, C. et al. Secondary organic aerosol formation from the β-pinene+ NO 3 system: effect of humidity and peroxy radical fate. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 7497–7522 (2015).

Joo, T., Rivera-Rios, J. C., Takeuchi, M., Alvarado, M. J. & Ng, N. L. Secondary organic aerosol formation from reaction of 3-methylfuran with nitrate radicals. ACS Earth Space Chem. 3, 922–934 (2019).

Jimenez, J. L. et al. Evolution of organic aerosols in the atmosphere. Science 326, 1525–1529 (2009).

Ng, N. L. et al. Organic aerosol components observed in Northern Hemispheric datasets from aerosol mass spectrometry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 4625–4641 (2010).

Hu, W. et al. Seasonal variations in high time-resolved chemical compositions, sources, and evolution of atmospheric submicron aerosols in the megacity Beijing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 9979–10000 (2017).

Huang, R.-J. et al. High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China. Nature 514, 218–222 (2014).

Aiken, A. C. et al. Mexico City aerosol analysis during MILAGRO using high resolution aerosol mass spectrometry at the urban supersite (T0)–Part 1: Fine particle composition and organic source apportionment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 6633–6653 (2009).

Tremp, J., Mattrel, P., Fingler, S. & Giger, W. Phenols and nitrophenols as tropospheric pollutants: emissions from automobile exhausts and phase transfer in the atmosphere. Water Air Soil Pollut. 68, 113–123 (1993).

Teng, A. et al. Hydroxy nitrate production in the OH-initiated oxidation of alkenes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 4297–4316 (2015).

Sun, Y. L. et al. Long-term real-time measurements of aerosol particle composition in Beijing, China: seasonal variations, meteorological effects, and source analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 10149–10165 (2015).

Zhu, W. et al. Seasonal variation of aerosol compositions in Shanghai, China: insights from particle aerosol mass spectrometer observations. Sci. total Environ. 771, 144948–144948 (2021).

Rollins, A. et al. Elemental analysis of aerosol organic nitrates with electron ionization high-resolution mass spectrometry. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 3, 301–310 (2010).

Kota, S. H. et al. Estimation of VOC emission factors from flux measurements using a receptor model and footprint analysis. Atmos. Environ. 82, 24–35 (2014).

De Carvalho, C. C. & da Fonseca, M. M. R. Biotransformation of terpenes. Biotechnol. Adv. 24, 134–142 (2006).

Wang, H. et al. A long-term estimation of biogenic volatile organic compound (BVOC) emission in China from 2001-2016: the roles of land cover change and climate variability. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 4825–4848 (2021).

Ma, J. et al. Impacts of land cover changes on biogenic emission and its contribution to ozone and secondary organic aerosol in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 4311–4325 (2023).

Zheng, M., Fang, M., Wang, F. & To, K. Characterization of the solvent extractable organic compounds in PM2. 5 aerosols in Hong Kong. Atmos. Environ. 34, 2691–2702 (2000).

Hou, X., Zhuang, G., Sun, Y. & An, Z. Characteristics and sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and fatty acids in PM2. 5 aerosols in dust season in China. Atmos. Environ. 40, 3251–3262 (2006).

Han, D. et al. Non-polar organic compounds in autumn and winter aerosols in a typical city of eastern China: size distribution and impact of gas-particle partitioning on PM2.5 source apportionment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 9375–9391 (2018).

Zhou, S. et al. Regional influence of wildfires on aerosol chemistry in the western US and insights into atmospheric aging of biomass burning organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 1–27 (2017).

Sun, Y. et al. Aerosol characterization over the North China plain: haze life cycle and biomass burning impacts in summer. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 2508–2521 (2016).

Mohr, C. et al. Contribution of nitrated phenols to wood burning brown carbon light absorption in Detling, United Kingdom during winter time. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 6316–6324 (2013).

Wang, X. et al. Emissions of fine particulate nitrated phenols from the burning of five common types of biomass. Environ. Pollut. 230, 405–412 (2017).

Li, M. et al. Nitrated phenols and the phenolic precursors in the atmosphere in urban Jinan, China. Sci. total Environ. 714, 136760 (2020).

Zhang, Y. & Wang, Y. Climate-driven ground-level ozone extreme in the fall over the Southeast United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10025–10030 (2016).

Ding, X. et al. Spatial and seasonal variations of isoprene secondary organic aerosol in China: Significant impact of biomass burning during winter. Sci. Rep. 6, 20411 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. Deconvolution and quantification of hydrocarbon-like and oxygenated organic aerosols based on aerosol mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 4938–4952 (2005).

Ulbrich, I. M., Canagaratna, M. R., Zhang, Q., Worsnop, D. R. & Jimenez, J. L. Interpretation of organic components from positive matrix factorization of aerosol mass spectrometric data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 2891–2918 (2009).

Canonaco, F., Crippa, M., Slowik, J. G., Baltensperger, U. & Prevot, A. S. H. SoFi, an IGOR-based interface for the efficient use of the generalized multilinear engine (ME-2) for the source apportionment: ME-2 application to aerosol mass spectrometer data. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 6, 3649–3661 (2013).

Paatero, P. The multilinear engine - a table-driven, least squares program for solving multilinear problems, including the n-way parallel factor analysis model. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 8, 854–888, (1999).

Zhu, Q. et al. Improved source apportionment of organic aerosols in complex urban air pollution using the multilinear engine (ME-2). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 11, 1049–1060 (2018).

Kaltsonoudis, C. et al. Characterization of fresh and aged organic aerosol emissions from meat charbroiling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 7143–7155 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.42207118).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z.: Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. J.S.: Investigation, Data curation. S.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision. Q.W.: Investigation, Data curation. Jun Chen: Data curation. S.L.: Project administration, Writing—review and editing. M.H.: Project administration, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, W., Shi, J., Guo, S. et al. Comparative analysis of methods for seasonal particulate organic nitrate estimation in urban areas. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 21 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00904-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-00904-5