Abstract

Intensification rates of tropical cyclones (TCs) are critical in determining their lifetime maximum intensity and destructive power. However, the interdecadal variability of TC intensification rates in the Western North Pacific (WNP) remains unclear. In this study, we focused on the changes in TC intensification rates during 1980-2022 and found an abrupt increase in TC intensification rates after 2002. This change was primarily attributed to TCs undergoing rapid intensification (RI-TC). Furthermore, our investigations revealed that the RI-TC intensification rates were strongly related to the proportions of intensification rates ≥10 knots/6 h (IR-10) (r = 0.88), and the frequency of IR-10 events was highly correlated to sea surface temperature anomalies (r = 0.79), modulated by El Niño-Southern Oscillation and Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. Additionally, we found that the IR-10 occurrence frequency shows a northwestward shift during 1980–2022, and this shift was primarily driven by 500 hPa vertical velocity, followed by vertical wind shear. These findings provide crucial insights into the evolution of TC intensification rates in the WNP over the past four decades. The role of IR-10 should not be underestimated in TC development, which could serve as a crucial parameter for the TC intensity prediction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tropical cyclones (TCs), which often induce heavy precipitation, storm surge, and other severe natural disasters, have gathered increasing global attention, particularly in the context of climate change1,2. The western North Pacific (WNP) is the most active basin, generating approximately one-third of global TCs. Given the increasing population density in East and Southeast Asia and the ongoing threat of rising sea levels, accurate predictions of TC intensity have become essential.

Despite considerable efforts invested in TC intensity change prediction, the results have fallen short of expectations3,4. A key challenge in this field is accurately predicting the intensification rate, one of the most critical metrics in TC analysis and forecasting. This metric plays an important role in determining the TC lifetime maximum intensity (LMI) and destructive power5. As TC intensification rates increase, prediction errors become more substantial, particularly in cases of rapid intensification (RI, defined as an intensification rate ≥30knots/24 h6). The difficulty in prediction arises from the complex nature of TC intensification, which is influenced not only by mesoscale phenomena, such as eyewall dynamics, convective bursts, and secondary vortices, but also by synoptic-scale environmental factors and climate indices operating on interannual to interdecadal timescales. Together, these factors render accurate prediction a multifaceted challenge.

In recent years, numerous studies have extensively examined the variations in TC intensification rates and their underlying mechanisms. It is widely recognized that favorable environmental conditions—such as high sea surface temperature (SST), high mid-level relative humidity, and low vertical wind shear6,7,8,9 -along with internal dynamic processes including convective bursts10,11, can significantly enhance the TC intensification rates. In light of long-term trends, many studies have investigated changes in TC characteristics globally. Some studies suggested that the TC intensity has increased in recent years12,13,14. Notably, a decrease in TC intensification duration was reported15. Taken together, these findings suggested an increase in TC intensification rates, as TCs were reaching higher intensities over shorter durations. This inference was subsequently corroborated by some studies16,17. However, while global assessments reveal increasing TC intensification rates across most basins, the WNP exhibits a more complex trend18. As the most active TC basin in the world, the WNP merits particular attention. Previous research has noted a marked increase in intensification rates of landfalling typhoons over the WNP, attributed to locally enhanced SST19. Other studies have also identified a pronounced increasing trend in WNP TC intensification rates, though this trend is observed within specific regions of the basin19,20,21. Additionally, an upward trend in the rapid intensification TC (RI-TC) intensification rates has been reported and associated with an increase in RI magnitude22. Beyond long-term trends, some studies have also found that TC activity is modulated by natural variability, including El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)23,24,25, Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO)26,27,28, and Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO)29,30,31.

Despite numerous studies investigating the WNP TC activity, changes in TC intensification rates over the past four decades remain poorly understood. Previous studies have often been limited to specific regions and have given insufficient consideration to the effects of natural climate oscillations19,20,21. To address these knowledge gaps, we aimed to elucidate the patterns of TC intensification rate change and identify the factors controlling these changes. Specifically, we systematically examined how intensification rates ≥10 knots/6 h events contributed to changes in TC intensification rates and how natural climate oscillations modulated these events.

Results

Characteristics and Abrupt Changes in TC Intensification Rates

First, we examined the TC intensification rate time series during 1980–2022. The black line in Fig. 1a depicts the temporal evolution of the 6-hour intensification rates for all TCs in the WNP, as derived from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) dataset. It reveals a clear upward trend in intensification rates in recent years, with a statistically significant abrupt change detected in 2002 using Pettitt’s test (p < 0.01). The Lepage test corroborates this abrupt change (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, this result remains consistent across different data sources (Supplementary Fig. 2) and intensification rate calculation intervals (Supplementary Fig. 3), collectively reinforcing the robustness of our findings. The average TC intensification rates increase dramatically by approximately 21.5%, from 3.87 knots/6 h during 1980–2002 to 4.7 knots/6 h during 2003–2022. This finding is consistent with the results reported in ref. 32, with a slight discrepancy likely due to different time intervals used for calculating intensification rates. Notably, TCs undergoing RI are more likely to reach higher intensities and, consequently, tend to exhibit greater intensification rates33. Therefore, we further divided TCs into two groups: TCs that undergo RI (RI-TCs) and TCs that do not undergo RI (nonRI-TCs). The red line in Fig. 1a represents the time series of RI-TC intensification rates, while the blue line is for nonRI-TC. Upon analyzing these time series, we found that for RI-TCs, both Pettitt’s test and Lepage test detected a statistically significant abrupt change in 2003, similar to that observed for all TCs. RI-TCs exhibited a substantial 20.9% increase in average intensification rates, from 4.97 knots/6 h during 1980-2003 (hereafter P1) to 6.01 knots/6 h during 2004–2022 (hereafter P2). The temporal evolution of TC intensification rates strongly correlates with that of RI-TCs (r = 0.78, p < 0.01). Conversely, in the case of nonRI-TCs, we detected an insignificant abrupt change in 1986. This indicates that the abrupt increase in all TC intensification rates can be attributed to RI-TCs. Notably, the TC intensification rates in 2007 and 2013 are exceptionally high, potentially contributing to the elevated mean intensification rate in P2. To assess the robustness of our findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding these extreme years (Supplementary Fig. 4). While the removal of 2007 and 2013 reduced the mean intensification rate in P2, both the temporal evolution and the identified change point remained consistent with Fig. 1a. This result confirms that our conclusions are robust and not driven by individual extreme years.

a The time series of all TC intensification rates (black line), RI-TC intensification rates (red line), and nonRI-TC intensification rates (blue line). The solid (dashed) vertical lines represent the significant (insignificant) detected abrupt changes in the year, and the dashed horizontal lines represent the averages of P1 (before the abrupt year) and P2 (after the abrupt year), respectively. b Boxplots comparing RI-TC and nonRI-TC intensification rates during periods P1 and P2.

Fig. 1b illustrates the distribution of intensification rates of RI-TCs and nonRI-TCs during P1 and P2. RI-TCs show a markedly higher intensification rate in P2 compared to P1, whereas nonRI-TCs maintain similar intensification rates across both periods. This distinction provides compelling evidence that the abrupt change in overall TC intensification rates can be attributed primarily to the marked shift in RI-TC intensification patterns. These findings are further corroborated by Supplementary Fig. 5, where Monte Carlo simulations were employed to minimize the potential impact of data overlap.

The probability density function (PDF) and cumulative distribution function (CDF) of 6-hour intensity changes for TCs in the WNP are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. Approximately half of the cases exhibit no intensity change. Only 8% of cases intensify by more than 10 knots within 6 h. While cases of intensification rate ≥10 knots (hereafter IR-10) are relatively uncommon, they occur much more frequently in RI-TCs. Specifically, 100% (97.3%) of RI-TCs undergo IR-10 at least once (twice) during their lifetime. In contrast, this proportion is 36.3% (16.4%) for nonRI-TCs. These differences suggest that IR-10 is a key characteristic of RI-TCs, distinguishing them from nonRI-TCs. Furthermore, the time series of RI frequency is highly correlated with IR-10 frequency (r = 0.92, p < 0.01), reinforcing that IR-10 can serve as a reliable indicator of RI (Supplementary Fig. 7).

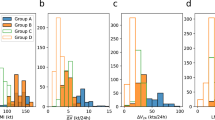

To further investigate the temporal characteristics of TC intensity changes, we divided study period into P1 (1980–2003) and P2 (2004–2022), as shown in Fig. 2a. The results reveal that P2 exhibits a higher frequency of both strong intensification events (≥10 kt/6 h, i.e., IR-10) and strong weakening events (≤ -10 kt/6 h), whereas P1 has a larger proportion of cases with little to no intensity change. This suggests that the TC intensification rate in the P2 exhibits greater variability, leading to more pronounced fluctuations in the time series (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the CDF shows a rightward shift for positive intensity changes, indicating an overall increase in the occurrence of higher intensity changes, meaning that more IR-10 events have occurred in P2. However, it is crucial to distinguish between absolute and relative changes in IR-10 events. While their proportion relative to all intensity change events increased in P2, the absolute frequency of IR-10 events did not show a statistically significant increase (Supplementary Fig. 8). This suggests that the apparent intensification trend is driven by changes in the overall distribution of intensity changes rather than an increase in the actual number of IR-10 events. Given that IR-10 plays a crucial role in the RI process, we further examined its relationship with TC intensification rates. Specifically, we analyzed how the proportion of IR-10 during the RI-TC intensification stage has changed over time. The results show a significant increase from P1 (26%) to P2 (32%), as illustrated in Fig. 2b. Notably, the time series of RI-TC intensification rates exhibits a strong correlation with the IR-10 proportion (r = 0.88, p < 0.01), suggesting that the recent increase in TC intensification rates are closely linked to the rise in the IR-10 proportion. In recent years, there has been a decline in the overall frequency of TCs over the WNP, while the frequency of RI-TCs has remained constant - a phenomenon attributed to climate regime shifts, primarily modulated by natural variability34. According to these results, we speculate that the frequency of IR-10 events may be controlled by natural climate oscillation.

a The probability density function and cumulative distribution function of 6-hour intensity changes for TCs. The blue bars and line represent the period P1 (1980–2003), while the red bars and line correspond to the period P2 (2004–2022). b The time series of RI-TC intensification rates (red line) and intensification rate ≥10 knots (IR-10) proportion (blue line). The dashed lines represent the averages of P1 and P2, respectively.

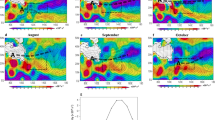

Co-variability of IR-10 and SST

Given the significant role of IR-10 events in TC intensification, further investigation into their changing causes was warranted. To this end, singular value decomposition (SVD) analysis was conducted on SST and IR-10 fields to explore the influence of natural climate oscillation on IR-10 events. Fig. 3 illustrates the distributions of the leading SVD mode, which explains 75% of the total covariance. The spatial pattern of SST anomalies (Fig. 3a) exhibits a composite pattern of the La Niña and negative IPO (-IPO) conditions, characterized by extensive negative SST anomalies in the central and eastern Pacific, contrasted with significant positive SST anomalies in the western Pacific. The time series of SST anomalies (Fig. 3b) shows a remarkably high correlation with the -Oceanic Niño Index (-ONI, r = 0.97, p < 0.01) and the -IPO index (r = 0.94, p < 0.01), suggesting that the leading SVD mode is predominantly modulated by the La Niña and -IPO. Fig. 3c depicts the response of IR-10 occurrences to SST changes. As SST varies, IR-10 events increase in the north of 20°N and west of 130°E, while decreasing in the south of 20°N and east of 130°E. That is to say, the frequency of IR-10 events increases in both nearshore areas and higher latitude regions. This finding reveals that ENSO- and IPO-modulated IR-10 frequency changes can reasonably explain the increased TC RI events35 and TC intensification rates36 in the offshore regions of the WNP and the poleward migration of TC LMI37,38, consistent with previous observations. The IR-10 time series in Fig. 3d is highly correlated with the SST anomalies time series (r = 0.79, p < 0.01), further confirming the role of ENSO and IPO in modulating IR-10 occurrence frequency.

The second SVD mode is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, accounting for 9.6% of the total covariance. The SST anomalies reveal a homogeneous warming pattern, except for cooling in coastal upwelling regions. The time series of SST anomalies exhibits a global warming trend and demonstrates a significant correlation with IR-10 events (r = 0.65, p < 0.01). As SST increases, IR-10 events become more frequent west of 150°E, except east of the Philippines. The changing climate has led to a decrease in RI events east of the Philippines39. Our findings suggest that, given the relationship between RI events and IR-10 events, the observed decrease in RI events may be linked to the decrease in IR-10 occurrences in this region. It is worth noting that the first SVD mode dominated the changes between SST and IR-10 events. Consequently, we only considered the first mode in the subsequent analysis.

Environmental Contributors and Physical Mechanisms

TC intensification rate is sensitive to various large-scale environmental conditions40, and these conditions are modulated by natural climate oscillations. Since these climate oscillations are well characterized by SST anomalies, we regressed the Dynamic Genesis Potential Index (DGPI) against the SST anomalies time series of the first SVD mode (Fig. 4a) to reveal how natural climate oscillations control TC development through modulating large-scale environmental conditions. The regression maps of DGPI closely mirror the distribution depicted in Fig. 3c, confirming that DGPI effectively captures the changes in IR-10 events. Fig. 4a reveals a distinctive strip-like distribution of DGPI anomalies. In response to SST variations, positive DGPI anomalies are observed north of 20°N and west of 130°E, while negative DGPI anomalies appear south of 20°N and east of 130°E. To quantify the relative contributions of four DGPI components, we adopted the method outlined in ref. 41 (see the “Methods” section for details). The regression maps of DGPI induced by 850 hPa absolute vorticity (Fig. 4b) show widespread negative DGPI anomalies across most of the WNP, except north of 20°N and coastal regions. This pattern indicates that changes in absolute vorticity could reduce the DGPI in these regions, thereby decreasing the frequency of IR-10 events. The spatial pattern in the regression maps of DGPI induced by vertical wind shear (Fig. 4c) resembles that of Fig. 4a, though the DGPI anomalies are relatively small. Positive DGPI anomalies, indicative of increased IR-10 event frequency, are observed in two regions: one spanning 0°-10°N, 120°-160°E, and another north of 20°N. Sandwiched between these areas is a prominent band of negative DGPI anomalies, representing the decreased likelihood of IR-10 events. Figure 4d shows pronounced positive DGPI anomalies induced by 500 hPa vertical velocity, particularly in the coastal regions. This pattern strongly suggests that the 500 hPa vertical velocity serves as the primary driver of positive DGPI anomalies, consequently fostering an increased frequency of IR-10 occurrence. The regression maps of DGPI induced by 500 hPa zonal wind gradient (Fig. 4e) exhibit a pattern similar to those generated by absolute vorticity (Fig. 4b). Figure 4f quantifies the relative contributions of each variable to DGPI changes. The 500 hPa vertical velocity emerges as the dominant factor, accounting for 93.7% of the observed changes. Vertical wind shear stands out as the secondary contributor, while both absolute vorticity and zonal wind gradient exhibit negative and comparatively minor contributions. Although prior studies have underscored the critical importance of relative humidity in TC intensification42,43, this factor is absent from the DGPI. Analysis of 600 hPa relative humidity variations with SST changes reveals a pattern (Supplementary Fig. 10) closely mirroring vertical velocity (Fig. 4d). This aligns with the finding reported in ref. 44, which demonstrated a strong correlation between 500 hPa vertical velocity and 600 hPa relative humidity.

DGPI is calculated by (a) including all variables, and varying individual components while setting others at climatology: b 850 hPa absolute vorticity (AV; K−1), c vertical wind shear between 200 and 850 hPa (VWS; K−1), d 500 hPa vertical pressure velocity (VV; K−1), e 500 hPa zonal wind gradient (ZWG; K−1). f Relative contribution of individual components to the changes of DGPI. Black dots indicate the regression exceeds the 95% significance level.

To elucidate the mechanisms driving DGPI variable changes, the 200 and 850 hPa wind fields were regressed against the SST anomalies time series of the first SVD mode (Fig. 5). Specifically, at 850 hPa, an anticyclonic circulation is present between 10°-20°N and 120°-180°E, while a cyclonic circulation exists between 20°-30°N and 120°-180°E (Fig. 5a). These circulation patterns induce a decrease in relative vorticity in the lower-latitude region and an increase in the higher-latitude region, as illustrated in Fig. 4b. At 850 hPa, southeasterly wind anomalies (Fig. 5a), and at 200 hPa, northeasterly wind anomalies (Fig. 5b), both intensify the climatological winds between 10°-20°N and 120°-180°E. This enhancement leads to an increase in vertical wind shear in this region (Fig. 4c). Conversely, the anomalous wind weakens the climatological wind at 200 and 850 hPa in the lower-latitude and higher-latitude regions, respectively, resulting in decreased vertical wind shear in these regions, as depicted in Fig. 4c. Figure 5a also illustrates the spatial regression pattern of outgoing longwave radiation (OLR). Pronounced negative OLR anomalies are observed over the South China Sea and the region encompassing 10°-30°N, 120°-160°E. These anomalies indicate enhanced convection in these areas, aligning with the vertical velocity patterns presented in Fig. 4d. This enhancement may be attributed to large easterly anomalies at 850 hPa in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, which advect moisture into WNP. The resulting abundant moisture provided conducive conditions for convection45. Figure 5b depicts the regression map of 200 hPa divergence, a factor known to influence TC intensification6. This map exhibits a spatial pattern remarkably similar to that of the OLR regression map, albeit with opposite signs. The combination of increased convection and upper-level divergence contributes to a higher frequency of IR-10 events in the north of 20°N and west of 130°E, as shown in Fig. 3c.

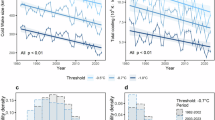

Diurnal Variation of the RI-TC Intensification Rate

As TC intensification rates increase, TCs tend to reach their LMI more rapidly. This acceleration in development suggests potential modifications to the diurnal variations of TC intensification rates. Specifically, the intensification rate of TCs, particularly those undergoing rapid intensification, typically peaks at 03-09 local solar time (LST) with the highest frequency of IR-10 events46. However, our study reveals a recent decline in these diurnal variations for RI-TCs over WNP (Fig. 6). During period P1, the frequency of IR-10 events exhibits a pronounced peak in 03-09 LST, significantly higher than in other 6-hour periods (Fig. 6a). In contrast, period P2 shows a more uniform distribution of IR-10 events throughout the day. Quantitatively, the diurnal amplitude [(Max-Min)/Mean×100%] demonstrates a substantial decrease from 18.6% in P1 to 2.02% in P2. A similar pattern emerges in the TC intensification rates (Fig. 6b), where the mean values increased from 4.8 knots/6 h in P1 to 5.9 knots/6 h in P2, accompanied by a marked reduction in diurnal amplitude from 9.39% to 2.77%. This phenomenon can be attributed to the dramatic increase in TC intensification rates coupled with a decrease in TC intensification duration, as documented in ref. 15. The compressed intensification duration has constrained the variability of intensification rates, consequently leading to a significant reduction in the amplitude of diurnal variations. Further research is warranted to determine whether similar changes in TC intensification rates and diurnal variations are manifesting in other basins.

a Frequency distribution of IR-10 events for RI-TCs. b Average intensification rates after removing the daily mean intensification rate. The sample size in a represents the total number of IR-10 events. Daily mean intensification rates are shown in b. Diurnal variation amplitudes [(Max-Min)/Mean×100%] for each metric are marked on the top of each panel.

Discussion

Despite many studies reporting an increase in WNP TC intensity47,48,49, a consensus on TC intensification rate changes in this region remains elusive. The significant upward trends identified in some studies are limited to specific regions within the basin19,20,21. Here, we examined TC intensification rate changes over the WNP during 1980–2022, along with the factors influencing these changes. We identified an abrupt increase of 21.5% in TC intensification rates after 2002. Further investigation revealed that this change was primarily attributed to RI-TCs, which showed a 20.9% increase in intensification rates from 2003 onward. Average RI-TC intensification rates increased from 4.97 knots/6 h (1980–2003) to 6.01 knots/6 h (2004–2022), associated with changes in IR-10 events. IR-10 events are crucial for TC to attain high intensity and play an essential role in modulating TC intensification rates. Notably, TC intensification rates are highly correlated with IR-10 event proportions (Fig. 2b). Our analysis revealed that although the absolute frequency of IR-10 events slightly decreased, their relative proportion increased significantly from 26% to 32%, indicating an enhanced contribution of these events to overall TC intensification. This substantial increase in TC intensification rates is accompanied by an intriguing phenomenon: a notable weakening of the diurnal variations in TC intensification rates. Such interconnection between the interdecadal variability and diurnal variability reveals a complex scale interaction in TC development.

Given the significant role of IR-10 events in TC intensification and their potential modulation by large-scale climate patterns, we conducted SVD analysis to investigate their relationship with natural climate oscillations. We found that the frequency of IR-10 events is highly correlated to SST anomalies (r = 0.79), modulated by El Niño-Southern Oscillation and Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation. The leading mode also revealed a northwestward shift in IR-10 frequency (Fig. 3a). This spatial shift of IR-10 events provides a possible mechanism for several observed changes in TC behavior, including increased frequency of nearshore TC RI events35, enhanced nearshore TC intensification rates36, and the poleward migration of TC LMI positions37,38. Through comprehensive analysis of environmental factors, we identified 500 hPa vertical velocity as the primary factor, followed by vertical wind shear (Fig. 4f). Furthermore, the changes in lower-level circulation and subsequent moisture advection, coupled with changes in upper-level circulation, increased upper-level divergence, and enhanced convection, collectively fostered favorable conditions in this region (Fig. 5).

When interpreting long-term trends, consideration must be given to the advancement of observational systems. Recent decades have witnessed substantial improvements in TC observing systems and intensity estimation techniques50. While these technological advancements could potentially introduce uncertainties in long-term trend analyses, we addressed this concern through cross-validation using multiple best-track datasets. Analysis of the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and Hong Kong Observatory (HKO) datasets (Supplementary Fig. 2) corroborates our primary findings. Pettitt’s test revealed a statistically significant abrupt change in 2003 for all TCs across both datasets, with marked upward shifts in RI-TC intensification rates occurring in 2004 (JMA) and 2003 (HKO). Despite minor discrepancies compared to JTWC data, the overall trend and detected change points remain largely consistent across datasets, indicating that the observed trend is not driven by a single agency reporting bias.

While our multi-dataset analysis confirms the robustness of these temporal changes, the exact mechanism behind the 2003 abrupt change remains incompletely understood. Previous studies identified an abrupt change in 1998 in TC activities, attributing it to the phase transition of IPO/PDO23,27. A recent study has demonstrated that ENSO can influence the North Atlantic Oscillation with a one-year lag, implying that atmospheric teleconnections may operate on extended timescales51. In light of these findings, the abrupt change in TC intensification rates we detected in 2003 may be attributed not only to ENSO but also to IPO and their interaction, potentially explaining the temporal offset from the previously identified 1998 shift, which warrants detailed examination.

This study systematically investigates the interdecadal variability of TC intensification rates in the WNP and highlights the crucial role of IR-10 events in TC development. IR-10 can serve as a crucial parameter for the TC intensity prediction. The increased TC intensification rates and decreased TC intensification diurnal variations both significantly influence TC activity in the WNP. These findings have profound implications for our understanding and prediction of TC behavior in a changing climate.

Methods

Observation and reanalysis datasets

The TC data for the WNP from 1980 to 2022, including intensity and location information, were obtained from the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) through the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS)52,53. For cross-validation purposes, we also incorporated TC records from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and Hong Kong Observatory (HKO). We choose the period 1980–2022, as intensity measurements are considered more reliable after 1980 due to the widespread use of satellite observations. Our study focused on TCs forming from June to November (TC season), encompassing approximately 85% of the annual TCs in the WNP. This period corresponds to the climatological peak of TC activity when environmental conditions are most favorable for TC development54, and is characterized by distinctly different atmospheric patterns compared to the non-TC season55. Only TCs that attained a peak intensity exceeding 34 knots were included in this analysis. We concentrated on the initial intensification phase of TCs. For those who reached their LMI multiple times, we exclusively analyzed the intensification process from TC genesis to the first occurrence of LMI. TC intensification rates were defined as the intensity change over the subsequent 6-hour period from any given time point. We opted for this 6-h interval instead of the 24-hour interval to minimize the potential impact of overlapping intensification events when calculating intensification rates. The 6-hour interval is also particularly useful for investigating the diurnal variations in TC intensification rates. For the analysis presented in Fig. 6, the local solar time of TC intensification rates and IR-10 events was adjusted based on longitudinal position to properly represent diurnal variations.

In addition to TC data, this study employed several other datasets. Monthly SST data were obtained from the Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature (ERSST) V5 dataset, provided by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), with a spatial resolution of 2° × 2°56. Monthly OLR data were also sourced from the NOAA reanalysis57, with a spatial resolution of 2.5° × 2.5°. Monthly atmospheric data at various pressure levels were obtained from the ERA-5 reanalysis dataset, produced by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, featuring a higher spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°58. The analysis encompassed the following atmospheric parameters: zonal wind components (u) at 200, 500, and 850 hPa; meridional wind components (v) at 200 and 850 hPa; vertical velocity at 500 hPa; and relative vorticity at 850 hPa. Additionally, two climatic indices were employed in the study: the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI), representing the ENSO, and the Tripole Index, characterizing the IPO59.

Statistical methods

Potential abrupt change points in the TC intensification rates time series were identified using two non-parametric statistical approaches: the Pettitt test60 and the Lepage test61. Both test methodologies are particularly effective for detecting abrupt change points, as they operate independently of data distributional assumptions. Monte Carlo simulation was used to minimize the effects of data overlap. Regression analysis was employed to diagnose the response of the Dynamic Genesis Potential Index and its individual components to SST variations. The statistical significance of the correlation coefficients was assessed using Student’s t-test.

To investigate the climate variability of TC intensification rates in the WNP, we employed SVD analysis, a widely used statistical technique in geosciences. SVD effectively extracted distinct coupled modes of co-variability from two fields62. In this study, we applied SVD to analyze the relationship between TC IR-10 and SST fields. The IR-10 field was constructed by aggregating IR-10 events into a 2° × 2° spatial grid, organized by their monthly occurrence, to match the resolution of the SST field. To enhance spatial continuity, a nine-point smoothing method was applied to the IR-10 field.

Dynamic Genesis Potential Index

The Genesis Potential Index63 has been widely recognized as a useful diagnostic tool for investigating the impacts of large-scale environmental conditions on TC development. However, Wang et al.64 found that the DGPI, proposed by Wang and Murakami44, significantly improved the skills in depicting the variability of TC activity in the WNP. The DGPI is calculated as:

where \({V}_{s}\) is the vertical wind shear between 850 and 200 hPa (\({{ms}}^{-1}\)), \(\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}\) is the meridional gradient of zonal wind at 500 hPa (\({s}^{-1}\)), \(\omega\) is the vertical pressure velocity at 500 hPa (\({{Pas}}^{-1}\)), and \(\eta\) is the absolute vorticity at 850 hPa (\({s}^{-1}\)).

To quantify the relative contributions of four DGPI components, we adopted the method outlined in ref. 41. Following logarithmic transformation and decomposition, Eq. 1 can be reduced to the following expression:

where

The overbar denotes the 43-year mean value, representing the climatological state. Detailed derivation procedures are elaborated in ref. 41. Based on the above mathematical framework, the relative contribution of each component can be quantitatively assessed by treating one DGPI component as a variable while prescribing the others at their climatological states.

Data Availability

All datasets utilized in this study are publicly accessible. The TC data are from the IBTrACS v04r01 at https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/international-best-track-archive. NOAA ERSST-V5 data are downloaded at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html. NOAA OLR data are at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.olrcdr.interp.html. ERA5 data are from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels-monthly-means?tab=overview. Oceanic Niño Index can be downloaded at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/oni.data. Tripole Index is from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/timeseries/IPOTPI/tpi.timeseries.ersstv5.data.

Code availability

The code used for analysis and plot in this study is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Mendelsohn, R., Emanuel, K., Chonabayashi, S. & Bakkensen, L. The impact of climate change on global tropical cyclone damage. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 205–209 (2012).

Peduzzi, P. et al. Global trends in tropical cyclone risk. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 289–294 (2012).

DeMaria, M., Sampson, C. R., Knaff, J. A. & Musgrave, K. D. Is tropical cyclone intensity guidance improving?. Bull. Am. Meteorological. Soc. 95, 387–398 (2014).

Emanuel, K. Will global warming make hurricane forecasting more difficult? Bull. Am. Meteorological. Soc. 98, 495–501 (2017).

Mei, W., Xie, S.-P., Primeau, F., McWilliams, J. C. & Pasquero, C. Northwestern Pacific typhoon intensity controlled by changes in ocean temperatures. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500014 (2015).

Kaplan, J. & DeMaria, M. Large-Scale Characteristics of Rapidly Intensifying Tropical Cyclones in the North Atlantic Basin. Wea. Forecast. 18, 1093–1108 (2003).

Fudeyasu, H., Ito, K. & Miyamoto, Y. Characteristics of tropical cyclone rapid intensification over the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 31, 8917–8930 (2018).

Hendricks, E. A., Peng, M. S., Fu, B. & Li, T. Quantifying environmental control on tropical cyclone intensity change. Mon. Wea. Rev. 138, 3243–3271 (2010).

Shu, S., Ming, J. & Chi, P. Large-scale characteristics and probability of rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones in the Western North Pacific Basin. Wea. Forecasting 27, (2012).

Jiang, H. The relationship between tropical cyclone intensity change and the strength of inner-core convection. Mon. Wea. Rev. 140, 1164–1176 (2012).

Nolan, D. S., Moon, Y. & Stern, D. P. Tropical Cyclone Intensification from Asymmetric Convection: Energetics and Efficiency. J. Atmos. Sci. 64, 3377–3405 (2007).

Elsner, J. B., Kossin, J. P. & Jagger, T. H. The increasing intensity of the strongest tropical cyclones. Nature 455, 92–95 (2008).

Kossin, J. P., Knapp, K. R., Olander, T. L. & Velden, C. S. Global increase in major tropical cyclone exceedance probability over the past four decades. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 11975–11980 (2020).

Wang, G., Wu, L., Mei, W. & Xie, S.-P. Ocean currents show global intensification of weak tropical cyclones. Nature 611, 496–500 (2022).

Wang, S., Rashid, T., Throp, H. & Toumi, R. A shortening of the life cycle of major tropical cyclones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088589 (2020).

Bhatia, K. et al. A potential explanation for the global increase in tropical cyclone rapid intensification. Nat. Commun. 13, 6626 (2022).

Bhatia, K. T. et al. Recent increases in tropical cyclone intensification rates. Nat. Commun. 10, 635 (2019).

Kishtawal, C. M., Jaiswal, N., Singh, R. & Niyogi, D. Tropical cyclone intensification trends during satellite era (1986-2010): TROPICAL CYCLONE INTENSIFICATIONS. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L10810 (2012).

Mei, W. & Xie, S.-P. Intensification of landfalling typhoons over the northwest Pacific since the late 1970s. Nat. Geosci. 9, 753–757 (2016).

Song, K., Zhan, R. & Wang, Y. Unveiling the Dominant Factors Controlling the Long‐Term Changes in Northwest Pacific Tropical Cyclone Intensification Rates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL108344 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Recent increase in rapid intensification events of tropical cyclones along China coast. Clim. Dyn. 62, 331–344 (2024).

Song, J., Duan, Y. & Klotzbach, P. J. Increasing trend in rapid intensification magnitude of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 084043 (2020).

Hu, C., Zhang, C., Yang, S., Chen, D. & He, S. Perspective on the northwestward shift of autumn tropical cyclogenesis locations over the western North Pacific from shifting ENSO. Clim. Dyn. 51, 2455–2465 (2018).

Guo, Y. & Tan, Z. Influence of Different ENSO Types on Tropical Cyclone Rapid Intensification Over the Western North Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD033059 (2021).

Zhao, H. & Wang, C. On the relationship between ENSO and tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific during the boreal summer. Clim. Dyn. 52, 275–288 (2019).

Hong, C.-C., Wu, Y.-K. & Li, T. Influence of climate regime shift on the interdecadal change in tropical cyclone activity over the Pacific Basin during the middle to late 1990s. Clim. Dyn. 47, 2587–2600 (2016).

Zhao, J., Zhan, R., Wang, Y. & Xu, H. Contribution of the interdecadal pacific oscillation to the recent abrupt decrease in tropical cyclone genesis frequency over the Western North Pacific since 1998. J. Clim. 31, 8211–8224 (2018).

Zhao, J., Zhan, R., Wang, Y., Xie, S.-P. & Wu, Q. Untangling impacts of global warming and Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation on long-term variability of North Pacific tropical cyclone track density. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba6813 (2020).

Wang, X. & Liu, H. PDO modulation of ENSO effect on tropical cyclone rapid intensification in the western North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 46, 15–28 (2016).

Wang, C., Fu, M., Wang, B., Wu, L. & Luo, J. Pacific Decadal Oscillation Modulates the Relationship Between Pacific Meridional Mode and Tropical Cyclone Genesis in the Western North Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101710 (2023).

Wang, H. & Wang, C. What caused the increase of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific during the period of 2011–2020? Clim. Dyn. 60, 165–177 (2023).

Huang, J., Ma, Z., Zhao, H., Fei, J. & Chen, L. Increase in western North Pacific tropical cyclone intensification rates and their northwestward shifts. Atmos. Res. 301, 107292 (2024).

Lee, C.-Y., Tippett, M. K., Sobel, A. H. & Camargo, S. J. Rapid intensification and the bimodal distribution of tropical cyclone intensity. Nat. Commun. 7, 10625 (2016).

Zhao, H., Duan, X., Raga, G. B. & Klotzbach, P. J. Changes in Characteristics of Rapidly Intensifying Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclones Related to Climate Regime Shifts. J. Clim. 31, 8163–8179 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Recent increases in tropical cyclone rapid intensification events in global offshore regions. Nat. Commun. 14, 5167 (2023).

Balaguru, K. et al. A Global Increase in Nearshore Tropical Cyclone Intensification. Earth’s Future 12, e2023EF004230 (2024).

Song, J. & Klotzbach, P. J. What Has Controlled the Poleward Migration of Annual Averaged Location of Tropical Cyclone Lifetime Maximum Intensity Over the Western North Pacific Since 1961? Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1148–1156 (2018).

Kossin, J. P., Emanuel, K. A. & Vecchi, G. A. The poleward migration of the location of tropical cyclone maximum intensity. Nature 509, 349–352 (2014).

Hong, J. & Wu, Q. Modulation of global sea surface temperature on tropical cyclone rapid intensification frequency. Environ. Res. Commun. 3, 041001 (2021).

Emanuel, K., DesAutels, C., Holloway, C. & Korty, R. Environmental control of tropical cyclone intensity. J. Atmos. Sci. 61, 843–858 (2004).

Li, Z., Yu, W., Li, T., Murty, V. S. N. & Tangang, F. Bimodal character of cyclone climatology in the Bay of Bengal modulated by monsoon seasonal cycle. J. Clim. 26, 1033–1046 (2013).

Camargo, S. J., Wheeler, M. C. & Sobel, A. H. Diagnosis of the MJO modulation of tropical cyclogenesis using an empirical index. J. Atmos. Sci. 66, 3061–3074 (2009).

Wu, L. et al. Relationship of environmental relative humidity with North Atlantic tropical cyclone intensity and intensification rate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, 2012GL053546 (2012).

Wang, B. & Murakami, H. Dynamic genesis potential index for diagnosing present-day and future global tropical cyclone genesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 114008 (2020).

Emanuel, K. & Zhang, F. The role of inner-core moisture in tropical cyclone predictability and practical forecast skill. J. Atmos. Sci. 74, 2315–2324 (2017).

Wu, Q., Hong, J. & Ruan, Z. Diurnal variations in tropical cyclone intensification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090397 (2020).

Elsner, J. B. Continued increases in the intensity of strong tropical cyclones. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 101, E1301–E1303 (2020).

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change Assessment: Part I: Detection and Attribution. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 100, 1987–2007 (2019).

Song, J., Klotzbach, P. J. & Duan, Y. Increasing lifetime maximum intensity of rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 034002 (2021).

Qian, C. et al. Tropical cyclone monitoring and analysis techniques: a review. J. Meteorol. Res. 38, 351–367 (2024).

Scaife, A. A. et al. ENSO affects the North Atlantic Oscillation 1 year later. Science 386, 82–86 (2024).

Knapp, K. R., Diamond, H. J., Kossin, J. P., Kruk, M. C. & Schreck, C. J. I. International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) Project, Version 4. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information https://doi.org/10.25921/82TY-9E16 (2018).

Knapp, K. R., Kruk, M. C., Levinson, D. H., Diamond, H. J. & Neumann, C. J. The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying Tropical Cyclone Data. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 91, 363–376 (2010).

Li, R. C. Y. & Zhou, W. Revisiting the intraseasonal, interannual and interdecadal variability of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 11, 198–208 (2018).

Gilford, D. M., Solomon, S. & Emanuel, K. A. On the seasonal cycles of tropical cyclone potential intensity. J. Clim. 30, 6085–6096 (2017).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, version 5 (ERSSTv5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 27 (2017).

Liebmann, B. & Smith, C. A. Description of a complete (Interpolated) outgoing longwave radiation dataset. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 1275–1277 (1996).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Henley, B. J. et al. A tripole index for the interdecadal pacific oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 45, 3077–3090 (2015).

Pettitt, A. N. A non-parametric approach to the change-point problem. Appl. Stat. 28, 126 (1979).

Lepage, Y. A combination of Wilcoxon’s and Ansari-Bradley’s statistics. Biometrika 58, 213–217 (1971).

Bretherton, C. S., Smith, C. & Wallace, J. M. An intercomparison of methods for finding coupled patterns in climate data. J. Clim. 5, 541–560 (1992).

Emanuel, K. & Nolan, D. S. Tropical cyclone activity and the global climate system. In 26th Conf. on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology 240–241 (AMS, 2004).

Wang, C. et al. Opposite skills of ENGPI and DGPI in depicting decadal variability of tropical cyclone genesis over the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 36, 8713–8721 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by Field Testing Consultation Services for Deep Water Hydrodynamic Monitoring Systems and Research Fund of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 330000210130313013006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—original draft. C.L.: Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition. F.L.: Funding Acquisition, Writing—review & editing. W.J.: Writing—review & editing. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Liang, C., Lin, F. et al. Interdecadal variability of tropical cyclone intensification rates in the Western North Pacific. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 123 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01001-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01001-3

This article is cited by

-

Western North Pacific Tropical cyclones act to suppress its adjacent Hadley circulation

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)