Abstract

The sea ice variabilities in West Antarctica, crucial for both local and global climate systems, are profoundly affected by the sea surface temperature anomalies over the tropical Atlantic. Analyses based on observational data and numerical model experiments demonstrate that the two recently identified Atlantic Niño types, central and eastern Atlantic Niño (CAN and EAN), have distinct impacts on the sea ice concentration in West Antarctica. The CAN stimulates two atmospheric Rossby wave trains in the Southern Hemisphere through both direct and indirect pathways, collectively strengthening the Amundsen Sea Low. In contrast, the EAN only excites one atmospheric wave train over the South Pacific through an indirect pathway, due to its associated weaker local Hadley circulation, which fails to establish a significant Rossby wave source in the subtropical South Atlantic. Consequently, compared to the EAN, the atmospheric circulation and the associated sea ice concentration anomalies in West Antarctica during the CAN are stronger and more extensive. Therefore, distinguishing between the two Atlantic Niño types could potentially enhance the seasonal prediction capabilities for sea ice concentration in West Antarctica.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few decades, West Antarctica has experienced significant climate changes1, characterized by notably increasing surface air temperatures (SAT)2,3 and rapid ice shelf melting4,5,6, which have a profound impact on the regional sea ice conditions7,8. Moreover, the extent of Antarctic sea ice reached record lows in both 2022 and 2023, consecutively9,10,11,12. These sea ice changes not only have major implications for polar ecosystems13,14 but also play critical roles in modulating global ocean heat and salt exchanges15,16, carbon dioxide cycling17,18, the meridional overturning circulation19,20, and sea level rise4,21. Specifically, the distribution of sea ice in West Antarctica is closely linked to atmospheric circulation anomalies controlled by the Amundsen Sea Low (ASL)22,23,24,25. The ASL, a permanent low-pressure system situated between the Bellingshausen Sea and the Ross Sea26, influences sea ice distribution in West Antarctica by modulating the meridional heat advection and wind stress forcing27,28.

Due to the increasing importance of the Antarctic sea ice in recent years, there has been growing interest in the relationship between the tropics and the climate in West Antarctica29,30,31,32,33. Interannual climate variability modes, particularly the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)34,35,36, the Indian Ocean Basin Mode37, the Indian Ocean Dipole38,39,40, and the Maritime Continent anomalies41,42 can all affect the ASL, inducing poleward propagating atmospheric Rossby wave trains, and thus influencing sea ice conditions in West Antarctica. Moreover, interdecadal climate variability modes, such as the Pacific Quasi-Decadal Oscillation43, the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation44,45, and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation29,46, also significantly alter the distribution of sea ice in West Antarctica by exciting similar atmospheric Rossby wave trains.

Additionally, the Atlantic Niño, the primary interannual variability mode of the tropical Atlantic47,48,49, could also impact the high latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere through two pathways: direct and indirect pathways50. The direct pathway refers to an atmospheric Rossby wave train induced by the strengthened local meridional Hadley circulation over the South Atlantic, while the indirect pathway is an atmospheric Rossby wave train induced by the enhanced zonal Walker circulation over the South Pacific. Both of these atmospheric wave trains can affect sea ice in West Antarctica by enhancing the ASL. These effects are most pronounced in austral winter, followed by the relatively weaker effects in spring, exhibiting strong seasonal dependence51.

Moreover, a recent study has classified the Atlantic Niño into the central Atlantic Niño (CAN) and the eastern Atlantic Niño (EAN) based on the location of the associated warmest centers of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies52. This classification is established through empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis of tropical Atlantic SST anomalies, based on the differences between the derived spatial modes (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. S1 for details). The CAN is characterized by the largest positive SST anomalies in the central equatorial region, whereas the EAN exhibits its largest positive SST anomalies in the eastern basin, extending poleward along the western African coasts. Consequently, these distinctions lead to notable differences in their impacts on local and global climates. For instance, the CAN exerts a more prominent impact on subsequent ENSO development compared to the EAN, especially during the 21st century52. Additionally, the impact of the CAN on the European climate is also more pronounced than that of the EAN, primarily due to their distinct atmospheric teleconnection patterns53. Locally, the influence of CAN on South American monsoon precipitation is more significant during austral summer, whereas the impact of the EAN on West African monsoon precipitation is stronger during austral winter54.

Considering the substantial role of the Atlantic Niño in global climate dynamics55,56,57,58,59 and the different effects exerted by the two types, it is intriguing to investigate the potentially different impacts of the CAN and EAN on West Antarctic sea ice, possibly caused by their associated distinct atmospheric teleconnection patterns. The results may further improve the accuracy of seasonal sea ice predictions for West Antarctica. The main objectives of this study are: (1) to investigate the distinct impacts of the two Atlantic Niño types on sea ice variability in West Antarctica, and (2) to analyze the associated mechanisms of these distinct impacts by exploring the associated different atmospheric teleconnection patterns.

Results

Distinct impacts on the sea ice in West Antarctica

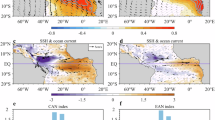

We first investigate the distinct impacts of the two Atlantic Niño types on the sea ice concentration (SIC) anomalies in West Antarctica during austral winter (June, July and August, JJA), the peak season of the Atlantic Niño. Considering the independent phenomena of the CAN and EAN as evidenced by previous research52, we performed individual regression analyses for each type. Regression patterns based on observational data reveal significant differences in both the location and intensity of the SIC anomalies in West Antarctica between the CAN and EAN (Fig. 1). Specifically, the SIC anomalies associated with the CAN show significant increases in region A (100°W-150°W, Fig. 1a), whereas those related to the EAN exhibit weaker increases in region B (80°W-100°W) and decreases in region C (160°W-180°, Fig. 1d). Notably, the CAN induces stronger and more extensive SIC anomalies in West Antarctica compared to the EAN, highlighting the distinct impacts of the two Atlantic Niño types.

a–c Regression of JJA sea ice concentration (SIC, %), surface air temperature (SAT, °C) and 850-hPa wind anomalies (m s−1) on the normalized JJA central Atlantic Niño index (CANI), respectively. d–f Same as (a–c) but for the eastern Atlantic Niño index (EANI). Stippling and black vectors represent anomalies that are statistically significant at the 90% confidence level. Regions marked A (100°W-150°W) in (a, b) denote the primary West Antarctic sea ice regions associated with the central Atlantic Niño (CAN), while regions B (160°W-180°) and regions C (80°W-100°W) in (d, e) represent key sea ice zones linked to the eastern Atlantic Niño (EAN).

As mentioned previously, the distribution of sea ice in West Antarctica is primarily associated with the atmospheric circulation controlled by the ASL22,23,31. Significant differences indeed exist in the atmospheric circulation anomalies over West Antarctica related to the two Atlantic Niño types. For instance, the regression analysis indicates that the CAN could induce low-level cyclonic (clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere) wind anomalies between the Ross Sea and the Antarctic Peninsula (Fig. 1c), indicating strengthened ASL. As a result, pronounced southerly anomalies dominate region A. In contrast, wind anomalies caused by the EAN are generally weaker than their counterpart during the CAN (Fig. 1f). Specifically, the EAN-related northerly anomalies are predominantly observed in region C, while much weaker southerly anomalies are largely confined to region B.

The atmospheric circulation anomalies could therefore lead to significant temperature changes and sea ice drift, affecting the distribution of sea ice in West Antarctica. It is shown that the cold air temperature anomalies caused by the CAN-induced southerly wind anomalies, primarily through meridional cold advection over region A (Fig. 1b, c), are conducive to sea ice formation. Meanwhile, these southerly anomalies also favor the offshore drift of the sea ice formed near the coast through wind stress forcing, thereby facilitating the continued generation of nearshore sea ice, ultimately leading to an increase in SIC anomalies. On the other hand, the changes in SIC and temperature anomalies over region B induced by the EAN are noticeably weaker due to the relatively weaker southerly anomalies (Fig. 1d–f). Meanwhile, in region C, dominant northerly anomalies drive pronounced warming and sea ice loss (Fig. 1d–f). Overall, the SIC variance contributed by the CAN accounts for ~20% of the total SIC variance over region A, with the EAN explains less than 10% of the variance over region B and region C (Supplementary Fig. S2a, b).

Previous research has shown that the CAN and EAN are closely linked to ENSO, with ENSO potentially being significantly influenced by both types during the austral winter52 (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, similar to the two Atlantic Niño types, ENSO could also significantly influence the temperature and sea ice distribution in West Antarctica during austral winter by affecting atmospheric circulation anomalies (Supplementary Fig. S3a–c). The SIC variance associated with ENSO accounts for ~20% of the total variance (Supplementary Fig. S4a), comparable to that of the CAN to the SIC variance ratio in this region (Supplementary Fig. S2a). Hence, the impact of ENSO on Antarctic sea ice may partly include signals from the Atlantic Niño. Therefore, in order to isolate the impacts of ENSO, we have linearly removed the influence of the CAN and EAN as described in Methods and found that the impact of ENSO is significantly weakened (Supplementary Fig. S3d–f). Its contribution to the SIC variance ratio is reduced to only ~10% (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Conclusively, both types of Atlantic Niño may have a significant impact on Antarctic sea ice by influencing changes in the Pacific.

Atmospheric waves induced by the two Atlantic Niño types

Results above demonstrate the distinct impacts of two Atlantic Niño types, which are primarily caused by their associated atmospheric circulation anomalies. Previous studies indicated that the Atlantic Niño could remotely impact the West Antarctica by exciting atmospheric Rossby waves originating from the tropics through precipitation changes31,51,60. Indeed, the two Atlantic Nino types are associated with different precipitation changes in the tropical Atlantic Ocean during austral winter52,53,54. The CAN is characterized by precipitation anomalies that are stronger and located further westward compared to the EAN. These different tropical precipitation anomalies may exert distinct climatic impacts on West Antarctica through varying atmospheric teleconnections.

The contrasting precipitation anomalies associated with the two Atlantic Niño types indeed lead to distinct teleconnection patterns over the Southern Hemisphere (Fig. 2). Specifically, the CAN induces alternating positive and negative geopotential height anomalies in the upper-level atmosphere across the subtropical South Atlantic, South Indian Ocean, South Pacific Ocean, and West Antarctica (Fig. 2a). In contrast, although the EAN excites a similar wave pattern over the Southern Hemisphere, the amplitudes are weaker compared to the CAN (Fig. 2b). Consequently, the geopotential height anomalies induced by the EAN over the South Indian Ocean are not significant, which might hinder eastward Rossby wave propagation (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, both types of the Atlantic Niño exhibit a strong correspondence between the spatial distribution of upper-level geopotential height anomalies and the lower-level atmospheric circulation anomalies over West Antarctica (Figs. 1a, b and 2).

a Regression of JJA 200-hPa geopotential height anomalies (GPH, shading, m) and wave activity fluxes (WAF, vector, m2 s−2) on the normalized JJA CANI. b Same as (a) but for the EANI. Black contours denote GPH anomalies that are statistically significant at 90% confidence level. The magenta (green) line represents the wave train propagation pathway generated by the direct (indirect) impact of Atlantic Niño on Antarctica.

In response to anomalous geopotential height, the atmospheric wave activity flux, which characterizes the propagation of Rossby wave energy as described in the Methods, also exhibits notable differences between the two Atlantic Niño types (Fig. 2). The CAN excites robust wave activity fluxes originating from the subtropical South Atlantic, which subsequently propagate southeastward towards the South Indian Ocean, then northeastward to southwest Australia, and finally deflect southeastward until reaching the ASL (magenta line, direct pathway, Fig. 2a). Concurrently, the CAN also induces southward propagating atmospheric wave activity fluxes from subtropical South Pacific to the ASL (green line, indirect pathway, Fig. 2a). While the wave activity flux pattern associated with the EAN over the South Pacific is similar to that of CAN, its intensity is relatively weaker (green line, indirect pathway, Fig. 2b). Generally, the CAN influences the ASL through both direct (magenta line) and indirect (green line) atmospheric wave train pathways, while the EAN impacts the ASL solely via the indirect pathway (green line). This difference of wave train pathways results in a more pronounced effect of the CAN on the atmospheric circulation over West Antarctica compared to the EAN, ultimately leading to significant disparities in their impacts on the sea ice in West Antarctica.

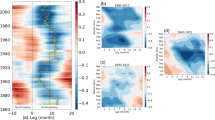

To examine the causes of the disparities in the atmospheric Rossby wave train over the Southern Hemisphere between the two types of Atlantic Niño, we analyze the Rossby wave source (RWS) generated by the two Atlantic Niño types. The RWS induced by both types are primarily located over the subtropical Southern Hemisphere (~30°S), close to the westerly jet stream (Fig. 3a, b). These RWS are primarily contributed by RWS1 (Eq. 2), which is associated with divergent wind anomalies related to the Atlantic Niño and climatological absolute vorticity (Supplementary Fig. S5). These divergent wind anomalies are additionally influenced by the atmospheric circulation anomalies related to the two Atlantic Niño types. For instance, both types enhance the Pacific Walker circulation anomalies, leading to upper-level anomalous zonal convergence over the central tropical Pacific (~130°W) (Fig. 4a, d). Then, these anomalies diverge southward over the upper-level atmosphere and exhibit anomalous meridional convergence over the subtropical South Pacific (~30˚S) (Fig. 4b, e). Meanwhile, the CAN also enhances local Hadley circulation anomalies, leading to upper-level anomalous convergence over the subtropical South Atlantic (~30°S) (Fig. 4c). In contrast, the EAN induces relatively weaker local Hadley circulation anomalies, resulting in weaker anomalous meridional convergence over the subtropical South Atlantic (~30°S) (Fig. 4f). Consequently, the divergent wind anomalies induced by the two Atlantic Niño types over the subtropical Southern Hemisphere exhibit significant differences (Supplementary Fig. S6).

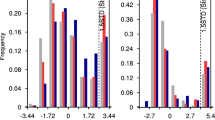

a, b Regression of JJA 200-hPa Rossby wave source (RWS, shading, s−2) and wave activity fluxes (WAF, vector, m2 s−2) on the normalized JJA CANI and EANI, respectively. Gray lines denote the zonal wind climatology (contour; m s−1) during JJA. Dotted areas denote values that are statistically significant at 90% confidence level. c Area-averaged regression coefficients of RWS on normalized CANI (blue bar, -1*s−2) and EANI (red bar, -1*s−2) during JJA. The area in the subtropical South Pacific (P-box, 20°S–45°S, 100°W–150°W) and subtropical South Atlantic (A-box, 20°S–45°S, 20°W–65°W) are denoted by the magenta boxes in (a, b).

a, d Regression of JJA atmospheric zonal circulation (tropical, averaged over 5°S–5°N) calculated from the zonal wind (vectors, m s−1) and vertical velocity (vectors and shading, −0.01*Pa s−1) on the normalized JJA CANI and EANI, respectively. b, e JJA atmospheric meridional circulation (Pacific, averaged over 100°W–150°W) calculated from the meridional wind (vectors, m s−1) and vertical velocity (vectors and shading, −0.01*Pa s−1) regressed on the normalized JJA CANI and EANI, respectively. c, f Same as (b, e) but for Atlantic (averaged over 20°W–65°W). The shading and black vectors represent anomalies that are statistically significant at the 90% confidence level.

Given the important role of the divergent wind anomalies associated with the two Atlantic Niño types in generating the RWS, we calculated the area-averaged RWS over the predominant divergent wind anomaly regions (magenta boxes in Fig. 3a, b, and Supplementary Fig. S6). As depicted in Fig. 3c, the CAN (blue bars) induces significant RWS anomalies over both the subtropical South Pacific (P-box) and the subtropical South Atlantic (A-box). Conversely, the EAN (red bars) excites strong RWS anomalies in the subtropical South Pacific but weaker anomalies in the subtropical South Atlantic. Notably, the RWS anomalies induced by both types are comparable in intensity over the subtropical South Pacific. For the subtropical South Atlantic, RWS anomalies induced by the CAN are almost twice as large as those induced by the EAN. Consequently, the EAN could only indirectly trigger one atmospheric wave train through its relatively strong influence on the Pacific, whereas the CAN could directly induce one atmospheric wave train in the Atlantic and indirectly excite another through its impact on the Pacific.

To further validate the distinct roles of the two Atlantic Niño types in inducing the atmospheric teleconnection patterns, we conducted the Community Earth System Model (CESM) experiments forced with their respective SST anomalies patterns as described in Methods. Compared to the analysis based on observational data (Fig. 2), the model outputs clearly demonstrate similar distinct atmospheric teleconnection patterns over the Southern Hemisphere induced by the two Atlantic Niño types (Fig. 5a, b). Specifically, the CAN excites atmospheric wave trains along two pathways: one from the subtropical South Atlantic to the Amundsen Seas (magenta line) and another from the subtropical South Pacific to the Amundsen Seas (green line) (Fig. 5a). In contrast, the EAN induces atmospheric wave trains only along one pathway: from the subtropical South Pacific to the Amundsen Seas (green line) (Fig. 5b). The different divergent wind changes over the subtropical South Pacific and the subtropical South Atlantic Oceans are reasonably reproduced as well (Fig. 5c, d). Consequently, the CESM results are overall consistent with the observations, providing strong support for our hypothesis: the CAN influences the ASL through direct and indirect induction of two atmospheric wave trains, whereas the EAN can only influence the ASL through indirect induction of one atmospheric wave train.

a Differences of JJA 200-hPa GPH (shading, m) and WAF (vector, m2 s−2) between the central Atlantic Niño (CAN) experiment and the control run (CTRL). b Same as (a) but for the eastern Atlantic Niño (EAN) experiment. Black contours denote GPH anomalies that are statistically significant at 90% confidence level. The magenta (green) line represents the wave train propagation pathway generated by the direct (indirect) impact of Atlantic Niño on Antarctica. c Differences of JJA precipitation (shading, mm day−1) and 200-hPa divergent wind (vector, m s−1) between the CAN experiment and the CTRL. d Same as (c) but for the EAN experiment. Stippling and black vectors represent anomalies that are statistically significant at the 90% confidence level.

Discussion

The Atlantic Niño represents the dominant mode of interannual variability in the tropical Atlantic, exerting a significant influence on sea ice conditions in West Antarctica. Considering the substantial differences in locations and intensities of SST and precipitation anomalies associated with the two Atlantic Niño types in the tropical Atlantic, this study mainly focuses on investigating the individual impact of the CAN and EAN on the sea ice in West Antarctica.

The two Atlantic Niño types exhibit distinct impacts on West Antarctic SIC variability during austral winter (Fig. 6). Observational analysis shows that the CAN induces significant increases in SIC anomalies in region A (Fig. 1a). In contrast, the EAN causes a weak increase of SIC anomalies in region B (Fig. 1d). This disparity is closely linked to the atmospheric circulation anomalies controlled by the ASL. The cyclonic circulation anomalies associated with the CAN are stronger over West Antarctica compared to the EAN, resulting in more pronounced southerly anomalies. These southerly anomalies, by modulating the cold advection and sea ice drift, lead to a more pronounced decrease in temperature and an increase in sea ice in West Antarctica. Additionally, the northerly anomalies associated with the EAN in region C are linked to a decline in SIC (Fig. 1d).

With evidence from both observations and numerical models, we found that both types of Atlantic Niño can strengthen the ASL, and thus influence the sea ice in West Antarctica by inducing atmospheric Rossby wave trains, but with notable discrepancies. In particular, the CAN induces significant RWS anomalies in both the subtropical South Pacific and the subtropical South Atlantic, whereas the EAN induces significant RWS anomalies only in the subtropical South Pacific. This discrepancy in RWS anomalies leads to the CAN inducing two atmospheric Rossby wave trains in Southern Hemisphere through both direct and indirect pathways, collectively enhancing the ASL. The EAN can only strengthen the ASL by indirectly inducing an atmospheric Rossby wave train in the southern Pacific.

Our findings emphasize the necessity of categorizing the Atlantic Niño into CAN and EAN types, given their significant global impacts. The CAN may not only have a stronger impact on sea ice in West Antarctica than the EAN, but may also exert a greater influence on the European climate, according to a previous study53. Moreover, the CAN has a more significant effect on the tropical Pacific climate compared to the EAN as well52. Generally, these differences can be explained by the stronger positive precipitation anomalies in the western tropical Atlantic associated with the CAN compared to the EAN52,53. Although our analysis has demonstrated stronger remote impacts from the CAN compared to EAN on West Antarctic SIC variability, this typical stronger impacts of the CAN on remote regions still needs to be further investigated through additional case studies to achieve a more convincing and broadly applicable statement.

It should be noted that the impact of the two Atlantic Niño types on ENSO exhibits interdecadal variability, mainly due to the rapid weakening of the EAN in recent decades52. It is therefore particularly important to thoroughly investigate whether there is similar interdecadal variability in the impact of the two Atlantic Niño types on the sea ice in West Antarctica. Additionally, it is also worth exploring how the impacts of the two Atlantic Niño types on sea ice in West Antarctica change under future scenarios of global warming. This information will provide crucial references for future climate predictions in West Antarctica and help inform climate change related strategy-making.

Methods

Observational data set

The monthly SST data analyzed in this study are derived from the Hadley Centre Sea Surface Temperature (HadISST) dataset61, which has a horizontal resolution of 1° × 1°. The SIC, SAT, winds, geopotential, and precipitation are obtained from the fifth generation of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts atmospheric reanalysis dataset (ERA5)62. The dataset offers a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25° and a vertical resolution of 37 levels for winds and geopotential, covering the period from 1970 to 2022. The long-term linear trends in all anomaly fields have been removed to eliminate the global warming signal. In addition, all significance tests that are necessary for this study are based on the p-values of the two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Definitions of the CAN and EAN

To characterize and identify the two Atlantic Niño types, we conducted an empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis on SST anomalies within the tropical Atlantic region (40°W–20°E, 10°S–10°N) for the period from 1970 to 2022 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Following the same method used by the previous study52, the CAN was derived as (EOF1–EOF3)/\(\sqrt{2}\), and the associated index, known as CANI, can be calculated by combining the corresponding principal components (PCs) as (PC1–PC3)/\(\sqrt{2}\). Similarly, the EAN and the EANI were defined as (EOF1 + EOF3)/\(\sqrt{2}\) and (PC1 + PC3)/\(\sqrt{2}\), respectively.

Atmospheric wave activity flux and Rossby wave source

The horizontal propagation of quasi-stationary Rossby waves is characterized in this study using the atmospheric wave activity flux63. Under the quasi-geostrophic approximation, the horizontal component of the wave activity flux in the pressure coordinate system is formulated as:

where \(p\) is the normalized atmospheric pressure (pressure/1000-hPa), \(a\) denotes the radius of the Earth (6.37 × 106 m), \(\lambda\) and\(\,\varphi\) correspond to longitude and latitude, respectively. \({\overrightarrow{{U}_{c}}}=({U}_{c},\,{V}_{c})\) denotes the climatological horizontal winds, and prime indicates anomalies from climatological means. Under the quasi-geostrophic assumption, the stream function anomaly \({(\psi }^{{\prime} })\) is derived from the ratio of geopotential anomaly \(({\phi }^{{\prime} })\) to the planetary vorticity \((f)\).

The Rossby wave source (RWS) was used here to investigate the impact of the two Atlantic Niño types on the generation of atmospheric Rossby waves64. The RWS equation is expressed as follows:

where \(f\) and \(\zeta\) represent planetary vorticity and relative vorticity, respectively. \({V}_{\chi }\) is the divergent component of the horizontal winds and \({\nabla }_{H}\) is the horizontal gradient. The overbar indicates climatological mean and prime represents anomalies. The first term (RWS1) on the right-hand side of Eq. (2) represents the component related to divergent winds anomalies and climatological absolute vorticity, while the second term (RWS2) is the component related to climatological divergent winds and relative vorticity anomalies.

Removal of the CAN and EAN signal

This study used a binary linear regression approach to isolate the impacts of CAN and EAN on the environmental fields, including the SIC, SAT and winds. Taking SIC as an example, the residual SIC (RSIC) is obtained by subtracting the effects of both Atlantic Niño types from the SIC anomalies. The expression is as follows:

where \(a\) is the regression constant, \({b}\) and \({c}\) represent the linear regression coefficient of the SIC anomalies regressed on the CANI and EANI, respectively.

Numerical experiments

To investigate and further validate the observed atmospheric teleconnection patterns associated with the two Atlantic Niño types over the Southern Hemisphere during austral winter, we designed a series of numerical experiments using the Community Earth System Model, version 1 (CESM1), from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR)65. The atmospheric component of CESM1 is the Community Atmosphere Model, version 4.0, with a horizontal resolution of approximately 2.5° × 1.9° and 26 vertical levels. The ocean component of the coupled system is the Parallel Ocean Program, version 2, which has a horizontal resolution of approximately 1° × 1° and 60 vertical levels with a maximum depth at 5375 m.

The experimental design comprises three sets of model runs: a control experiment and two sensitivity experiments. In the control run, the SST in the tropical Atlantic region is prescribed to the annual cycle of model climatology, whereas other regions are allowed to evolve freely under integration. For the two sensitivity runs, composite monthly SST anomalies for the CAN and EAN during a full calendar year were respectively superimposed within the tropical Atlantic region. The CAN (EAN) years are defined as when the JJA mean CANI (EANI) exceeded (fell below) one standard deviation over the analysis period. In all three experiments, a buffer zone spanning 5° was instituted at both the northern and southern peripheries of the tropical Atlantic region. Prior to applying any SST forcing, all three experiments underwent a 200-year spin-up integration to ensure a full model coupling. Subsequently, the SST forcing was applied, and the integration continued for an additional 30 years. The averaged results from the final 25 years of each experiment were then used for the formal analysis.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available. The observational monthly SST data set from HadISST are obtained from https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/data/download.html. The fifth generation of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts atmospheric reanalysis datasets (ERA5) reanalysis data set are available from ECMWF at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.6860a573. The scripts for data analysis and numerical model results used in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Dalaiden, Q., Schurer, A. P., Kirchmeier‐Young, M. C., Goosse, H. & Hegerl, G. C. West Antarctic Surface Climate Changes Since the Mid‐20th Century Driven by Anthropogenic Forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099543 (2022).

Ding, Q., Steig, E. J., Battisti, D. S. & Küttel, M. Winter warming in West Antarctica caused by central tropical Pacific warming. Nat. Geosci. 4, 398–403 (2011).

Bromwich, D. H. et al. Central West Antarctica among the most rapidly warming regions on Earth. Nat. Geosci. 6, 139–145 (2013).

Team, I. Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017. Nature 558, 219–222 (2018).

Andreasen, J. R., Hogg, A. E. & Selley, H. L. Change in Antarctic ice shelf area from 2009 to 2019. Cryosphere 17, 2059–2072 (2023).

Flexas, M. M., Thompson, A. F., Schodlok, M. P., Zhang, H. & Speer, K. Antarctic Peninsula warming triggers enhanced basal melt rates throughout West Antarctica. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj9134 (2022).

Jones, J. M. et al. Assessing recent trends in high-latitude Southern Hemisphere surface climate. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 917–926 (2016).

Meehl, G. A. et al. Sustained ocean changes contributed to sudden Antarctic sea ice retreat in late 2016. Nat. Commun. 10, 14 (2019).

Raphael, M. N. & Handcock, M. S. A new record minimum for Antarctic sea ice. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 215–216 (2022).

Turner, J. et al. Record Low Antarctic Sea Ice Cover in February 2022. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098904 (2022).

Liu, J., Zhu, Z. & Chen, D. Lowest Antarctic Sea Ice Record Broken for the Second Year in a Row. Ocean-Land-Atmos. Res. 2, 0007 (2023).

Purich, A. & Doddridge, E. W. Record low Antarctic sea ice coverage indicates a new sea ice state. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 314 (2023).

Fretwell, P. T., Boutet, A. & Ratcliffe, N. Record low 2022 Antarctic sea ice led to catastrophic breeding failure of emperor penguins. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 273 (2023).

Schofield, O. et al. Antarctic pelagic ecosystems on a warming planet. Trends Ecol. Evol. 39, 1141–1153 (2024).

Haumann, F. A., Gruber, N., Munnich, M., Frenger, I. & Kern, S. Sea-ice transport driving Southern Ocean salinity and its recent trends. Nature 537, 89–92 (2016).

Si, Y., Stewart, A. L. & Eisenman, I. Heat transport across the Antarctic Slope Frontcontrolled by cross-slope salinity gradients. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd7049 (2023).

Wadham, J. L. et al. Ice sheets matter for the global carbon cycle. Nat. Commun. 10, 3567 (2019).

Sigman, D. M., Hain, M. P. & Haug, G. H. The polar ocean and glacial cycles in atmospheric CO2 concentration. Nature 466, 47–55 (2010).

Marshall, J. & Speer, K. Closure of the meridional overturning circulation through Southern Ocean upwelling. Nat. Geosci. 5, 171–180 (2012).

Li, Q., England, M. H., Hogg, A. M., Rintoul, S. R. & Morrison, A. K. Abyssal ocean overturning slowdown and warming driven by Antarctic meltwater. Nature 615, 841–847 (2023).

Mengel, M., Feldmann, J. & Levermann, A. Linear sea-level response to abrupt ocean warming of major West Antarctic ice basin. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 71–74 (2016).

Turner, J., Hosking, J. S., Marshall, G. J., Phillips, T. & Bracegirdle, T. J. Antarctic sea ice increase consistent with intrinsic variability of the Amundsen Sea Low. Clim. Dyn. 46, 2391–2402 (2016).

Holland, M. M., Landrum, L., Raphael, M. N. & Kwok, R. The Regional, Seasonal, and Lagged Influence of the Amundsen Sea Low on Antarctic Sea Ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 11,227–211,234 (2018).

Raphael, M. N., Holland, M. M., Landrum, L. & Hobbs, W. R. Links between the Amundsen Sea Low and sea ice in the Ross Sea: seasonal and interannual relationships. Clim. Dyn. 52, 2333–2349 (2019).

Raphael, M. N. et al. The Amundsen Sea Low: Variability, Change, and Impact on Antarctic Climate. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 97, 111–121 (2016).

Turner, J., Phillips, T., Hosking, J. S., Marshall, G. J. & Orr, A. The Amundsen Sea low. Int. J. Climatol. 33, 1818–1829 (2013).

McGregor, J., Renwick, J. A. & Clem, K. R. Large-Scale Forcing of the Amundsen Sea Low and Its Influence on Sea Ice and West Antarctic Temperature. J. Clim. 30, 8405–8424 (2017).

Hobbs, W. R. et al. A review of recent changes in Southern Ocean sea ice, their drivers and forcings. Glob. Planet. Change 143, 228–250 (2016).

Li, X., Holland, D. M., Gerber, E. P. & Yoo, C. Impacts of the north and tropical Atlantic Ocean on the Antarctic Peninsula and sea ice. Nature 505, 538–542 (2014).

Li, X., Holland, D. M., Gerber, E. P. & Yoo, C. Rossby Waves Mediate Impacts of Tropical Oceans on West Antarctic Atmospheric Circulation in Austral Winter. J. Clim. 28, 8151–8164 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Tropical teleconnection impacts on Antarctic climate changes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 680–698 (2021).

Zhang, P. & Duan, A. Connection between the Tropical Pacific and Indian Ocean and Temperature Anomaly across West Antarctic. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 49 (2023).

Clem, K. R. et al. Record warming at the South Pole during the past three decades. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 762–770 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. The Impacts of Combined SAM and ENSO on Seasonal Antarctic Sea Ice Changes. J. Clim. 36, 3553–3569 (2023).

Welhouse, L. J., Lazzara, M. A., Keller, L. M., Tripoli, G. J. & Hitchman, M. H. Composite Analysis of the Effects of ENSO Events on Antarctica. J. Clim. 29, 1797–1808 (2016).

Dou, J. & Zhang, R. Weakened relationship between ENSO and Antarctic sea ice in recent decades. Clim. Dyn. 60, 1313–1327 (2023).

Yu, L., Zhong, S., Vihma, T., Sui, C. & Sun, B. The Impact of the Indian Ocean Basin Mode on Antarctic Sea Ice Concentration in Interannual Time Scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL097745 (2022).

Zhang, L., Ren, X., Cai, W., Li, X. & Wu, L. Weakened western Indian Ocean dominance on Antarctic sea ice variability in a changing climate. Nat. Commun. 15, 3261 (2024).

Nuncio, M. & Yuan, X. The Influence of the Indian Ocean Dipole on Antarctic Sea Ice. J. Clim. 28, 2682–2690 (2015).

Kim, J. et al. Remote Influences of ENSO and IOD on the Interannual Variability of the West Antarctic Sea Ice. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2022JD038313 (2023).

Chen, J., Hu, X., Yang, S., Lin, S. & Li, Z. Influence of Convective Heating Over the Maritime Continent on the West Antarctic Climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL097322 (2022).

Yang, S., Chen, D. & Deng, K. Global Effects of Climate Change in the South China Sea and Its Surrounding Areas. Ocean Land Atmos. Res. 3, 0038 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Decadal oscillation provides skillful multiyear predictions of Antarctic sea ice. Nat. Commun. 14, 8286 (2023).

Clem, K. R. & Fogt, R. L. South Pacific circulation changes and their connection to the tropics and regional Antarctic warming in austral spring, 1979–2012. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 2773–2792 (2015).

Meehl, G. A., Arblaster, J. M., Bitz, C. M., Chung, C. T. Y. & Teng, H. Antarctic sea-ice expansion between 2000 and 2014 driven by tropical Pacific decadal climate variability. Nat. Geosci. 9, 590–595 (2016).

Li, X., Gerber, E. P., Holland, D. M. & Yoo, C. A Rossby Wave Bridge from the Tropical Atlantic to West Antarctica. J. Clim. 28, 2256–2273 (2015).

Lübbecke, J. F. Tropical Atlantic warm events. Nat. Geosci. 6, 22–23 (2013).

Lübbecke, J. F. et al. Equatorial Atlantic variability—Modes, mechanisms, and global teleconnections. Wires Clim. Change 9, e527 (2018).

Zebiak, S. E. Air–sea interaction in the equatorial Atlantic region. J. Clim. 6, 1567–1586 (1993).

Simpkins, G. R., Peings, Y. & Magnusdottir, G. Pacific Influences on Tropical Atlantic Teleconnections to the Southern Hemisphere High Latitudes. J. Clim. 29, 6425–6444 (2016).

Yu, L., Zhong, S., Vihma, T., Sui, C. & Sun, B. The seasonal Antarctic sea ice concentration anomalies related to the Atlantic Niño index. Environ. Res. Clim. 2, 041004 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Emergence of the Central Atlantic Niño. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi5507 (2023).

Chen, B., Zhang, L. & Wang, C. Distinct Impacts of the Central and Eastern Atlantic Niño on the European Climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107012 (2024).

Xing, W., Wang, C., Zhang, L., Chen, B. & Liu, H. Influences of Central and Eastern Atlantic Niño on the West African and South American summer monsoons. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 214 (2024).

Wang, C. Three-ocean interactions and climate variability: a review and perspective. Clim. Dyn. 53, 5119–5136 (2019).

Cai, W. J. et al. Pantropical climate interactions. Science 363, eaav4236 (2019).

Wang, C., Kucharski, F., Barimalala, R. & Bracco, A. Teleconnections of the tropical Atlantic to the tropical Indian and Pacific Oceans: A review of recent findings. Meteorol. Z. 18, 445–454 (2009).

Fan, H., Wang, C., Yang, S. & Zhang, G. Coupling is key for the tropical Indian and Atlantic oceans to boost super El Niño. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp2281 (2024).

Wang, J.-Z. & Wang, C. Joint Boost to Super El Niño from the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. J. Clim. 34, 4937–4954 (2021).

Simpkins, G. R., McGregor, S., Taschetto, A. S., Ciasto, L. M. & England, M. H. Tropical Connections to Climatic Change in the Extratropical Southern Hemisphere: The Role of Atlantic SST Trends. J. Clim. 27, 4923–4936 (2014).

Rayner, N. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4407 (2003).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 608–627 (2001).

Sardeshmukh, P. D. & Hoskins, B. J. The generation of global rotational flow by steady idealized tropical divergence. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 1228–1251 (1988).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The community earth system model: a framework for collaborative research. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (W2441014 and 42192564), and the Development Fund of South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (SCSIO202208). We express our sincere gratitude to Yuwei Hu for the valuable assistance provided in improving this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.C. designed the study and drafted the initial manuscript in collaboration with C.W. and L.Z. B.C. conducted the analysis and prepared the figures. H.F. performed the numerical model experiments. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and the revision of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, B., Wang, C., Zhang, L. et al. Distinct Impacts of the Central and Eastern Atlantic Niño on West Antarctic Sea Ice. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 142 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01040-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01040-w

This article is cited by

-

Indian summer monsoon rainfall drives Antarctic climate and sea ice variability through atmospheric teleconnections

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)