Abstract

The Atlantic Niño exerts profound impacts on regional and global atmospheric circulation and climate, and on equatorial Atlantic biogeochemistry and ecosystems. However, the mode’s prediction remains a challenge which has been partly attributed to weak atmosphere-ocean coupling in the region. Here we introduce a framework that enhances the detection of the coupling between meridional migrations of atmospheric deep convection and zonal thermocline feedback. This approach reveals high predictive skill in a 196-member seasonal prediction ensemble, demonstrating robust predictability at 1–5-month forecast initialization lead times. The coupled mode is strongly correlated with land-precipitation variability across the tropics. The predictive skill largely originates in the Atlantic Ocean and is uncorrelated with El Niño Southern Oscillation in the Pacific, the leading mode of interannual climate variability globally. These skillful predictions raise hopes for enabled action in advance to avoid the most severe societal impacts in the affected countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Large-scale air-sea interactions over the tropical oceans represent a key source of seasonal climate predictability. El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in the tropical Pacific, the most prominent mode of interannual climate variability globally, exhibits useful prediction skills for several months1,2,3. The tropical Indian and Atlantic Oceans also host modes of interannual variability that involve coupled atmosphere-ocean interactions. For example, the Indian Ocean basin-wide and the Indian Ocean dipole modes4,5,6 as well as the North Tropical Atlantic, Benguela Niño, and Atlantic Niño modes, are all considered additional sources of seasonal climate predictability7,8,9,10.

The leading mode of sea-surface temperature (SST) variability in the tropical Atlantic is the Atlantic Niño, also called equatorial mode or zonal mode, which accounts for 32% of the tropical Atlantic (20°S–20°N) SST variability in satellite observations 1982–201611. The Atlantic Niño peaks during the boreal summer and exhibits zonal structures in wind stress, thermocline, and SST variability that are largely governed by dynamics similar to ENSO11,12,13,14,15. However, the coupling between the atmosphere and ocean is weaker, and the seasonal climate is less predictable in the tropical Atlantic region compared to the tropical Pacific region12,13,16.

Here we present a framework that enhances the detection of the coupling17 between the migrations of the Atlantic Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) in the meridional direction and the thermocline feedback in the zonal direction, which are key in setting the seasonality of the Atlantic Niño18,19,20. The derived coupled mode serves as the basis to investigate the simulated and predicted variability in ensembles of state-of-the-art coupled climate models21,22 and the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) seasonal prediction system. The observed patterns can be predicted five months ahead in the C3S ensemble and at all available six-month lead times in three forecast systems. The coupled mode’s statistically significant correlation with ENSO and land-precipitation variability across the tropics proves the value of our framework in informing societal preparedness.

Observations of atmospheric deep convection-ocean coupling

A strong coupling between atmospheric deep convection and oceanic variability in the equatorial Atlantic is revealed by the leading maximum covariance analysis (MCA1) mode of the observed meridional-precipitation and zonal-SST anomalies (Fig. 1). This mode which is based on linearly detrended and deseasonalized data accounts for 70% of the coupled variance from 1982–2004. The associated principal component time series (precipitation-PC1 and SST-PC1) exhibit closely related variability (r = 0.92; Fig. 1j). The maximum-precipitation variability can be linked to the ITCZ18,19,20, which exhibits a clear northward migration from the boreal spring to summer, crossing the equator in May over the western equatorial Atlantic (Fig. 1a). The thermocline slope is strongly reduced along the equator, associated with an increased upper-ocean heat content in the east as suggested by the positive sea-surface height (SSH) anomalies (Fig. 1g), a proxy for upper-ocean heat content variability23 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Consistent with the positive SSH anomalies, the largest SST anomalies are observed in the eastern basin in June (Fig. 1d). The SSH exhibits some memory, then diminishes rapidly following the peak SST variability in June and becomes negative later in the year. This points to a cyclic behavior, consistent with the recharge-discharge oscillator paradigm of equatorial upper-ocean heat content associated with ENSO-like dynamics3,24.

a–c Meridional precipitation anomalies regressed on the SST-PC1 (color-scale), the contours show the SST anomalies regressed on the precipitation-PC1; d–f Zonal-SST anomalies regressed on the precipitation-PC1 (color-scale), the contours show the precipitation anomalies regressed on the SST-PC1; g–i Zonal SSH anomalies regressed on the precipitation-PC1 (color-scale), the contours show the SSH anomalies regressed on the SST-PC1. j–l Normalized precipitation-PC1 (dashed, blue) and SST-PC1 (solid, red). Left–right columns: observations, CMIP5, and CMIP6 ensembles, respectively. In panels a–i, the stipples denote statistical significance at the 95% confidence level; the contour intervals are 0.1 K for SST, 0.3 mm/day for precipitation, and 10-2 m for the SSH anomalies.

The MCA1 represents the coupling between the seasonal variability of atmospheric deep convection, for which tropical precipitation is a measure, in the meridional direction18 and equatorial SST in the zonal direction11,12,13,14,15,16,25,26 in the equatorial Atlantic. The SST-PC1 is highly correlated with the Atlantic Niño index (Atl3-SST hereafter), defined as the SST anomalies averaged over the eastern equatorial Atlantic region13 during the active months of May to August (r = 0.97). This translates to 95% of the Atlantic Niño variability that is explained by the SST-PC1. The regression of the Atl3-SST on the normalized SST-PC1 is the same as the Atl3-SST standard deviation of 0.46 K. As shown by the horizontal regression maps, the MCA1 correctly captures the characteristic coupled evolution of the SST, ocean heat content, and precipitation anomalies associated with the Atlantic Niño (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Pattern enhancement through ensemble-averaging

Next, we investigate the representation of the zonal-meridional variability in the current state-of-the-art climate models using ensembles of the Coupled Models Intercomparison Project phases 5 and 6 (CMIP5 and CMIP6). Although there are large biases in the individual models (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3), the multimodel ensembles capture some important aspects of the observed MCA1. For instance, the maximum precipitation variability at the equator leads the peak SST variability in boreal summer by one month in the ensemble averages (Fig. 1b, c, e, f). This is consistent with observations (Fig. 1a, d), and is associated with the Atlantic ITCZ crossing the equator which enhances atmosphere-ocean coupling in the region18,19,20. The ensembles also depict the observed east-west gradient in the SSH anomalies (Fig. 1h, i). Here, the CMIP6 ensemble with SSH from 41 members exhibits a more realistic pattern (with pattern correlation rp = 0.81) than the CMIP5 ensemble with only 12 members (rp = 0.72).

Nevertheless, biases are still large in both ensemble averages (Figs. S4 and S5). For instance, the ITCZ is located too far south from boreal spring to early summer, associated with warm (cold) SST biases in the eastern (western) equatorial Atlantic. The ensemble means also exhibit smaller and less cyclic SSH variability than observed (Fig. 1g–i), suggesting weaker atmosphere-ocean coupling and recharge-discharge behavior. The biases in the zonal-meridional variability may thus be related to the mean-state biases in the equatorial Atlantic27,28,29,30, which tend to keep the ITCZ too close to the equator (Fig. 1b, c) and cause a longer persistence of the SST and SSH anomalies in the models (Fig. 1e, f, h, i).

Skillful predictability of the MCA1 in C3S ensemble

We employ the zonal-meridional coupling described by MCA1 as a framework to investigate predictability of the Atlantic Niño in the 196-member C3S multi-system prediction ensemble. Here we focus on the period 1993–2014 with complete data available from all ensemble members for the 1-6 months lead-times. For the Atlantic Niño which peaks in June, a one- (six-) month lead-time implies that the forecast was initialized on 01 May (01 December).

The C3S ensemble displays strong atmosphere-ocean coupling, with high correlations between the SST-PC1 and precipitation-PC1 which appear to be independent of lead-time (r ≥ 0.90; Fig. 2o–u). The zonal-meridional patterns are qualitatively similar to the observations (Fig. 2a–n). Specifically, the peak-SST variability occurs in June and is preceded by the peak precipitation variability for all lead-time predictions.

a–g Zonal-SST anomalies regressed on the precipitation-PC1 (color-scale), the contours show precipitation anomalies regressed on the SST-PC1. h–n Meridional precipitation anomalies regressed on the SST-PC1 (color-scale), the contours show the SST anomalies regressed on the precipitation-PC1. The stipples in panels a–n denote statistical significance at the 95% confidence level and the contour intervals are 0.1 K for SST, 0.3 mm/day for precipitation. o–u Normalized precipitation-PC1 (dashed, blue) and SST-PC1 (solid, red). The correlation between the two PC1s is indicated in the top-right corner of each panel.

The ensemble-prediction patterns of SST and precipitation are highly correlated with observations (rp > 0.70; Fig. 3), although large lag-1 autocorrelation (r1 = 0.9973) of the SST-Hovmöller patterns preclude statistical significance. The precipitation pattern exhibits less autocorrelation (r1 = 0.4934) and is statistically significant at lead-times of 1–6-months after accounting for the autocorrelation31. Further, the root mean square errors (RMSEs) of the standardized SST and precipitation patterns are generally small (<0.80), which is quite insensitive to the lead time, indicating overall skillful pattern predictions.

a, b Correlation skills and c, d Normalized RMSE for the (a, c) principal components and (b, d) seasonal patterns of the MCA1 mode. The dashed lines in panels (a, b) denote the 95% confidence level, whereas the red and blue curves are for the SST and precipitation, respectively. Initialization lead-time denotes the time interval between the forecast initialization and the target month being predicted, being the peak of the Atlantic Nino in June. The Atl3-SST autocorrelation function is calculated as the correlation between the peak phase (June) index and the previous six months from December to May.

The C3S ensemble prediction of the associated PCs is skillful at the 95% confidence level at lead times of 1–5 months. In contrast, the Atl3-SST index exhibits less correlation skill and larger RMSE, deviating from the SST-PC1 after a 2-month lead-time. This discrepancy highlights the importance of our MCA1 approach for advancing seasonal climate predictions in the equatorial Atlantic. Indeed, three prediction systems in the C3S forecast ensemble (ECMWF, EEEC, and JMA) display SST-PC1 correlation skills above the 95% confidence level at all 6-month lead times (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Predictable ENSO and tropical climate impacts

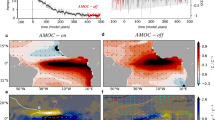

The Atlantic Niño can excite large-scale atmospheric teleconnections across the tropics, causing profound climatic impacts32,33,34,35 (Fig. 4a–h). We find that the peak phase of the MCA1 mode is accompanied by easterly wind-stress anomalies over the central and western tropical Pacific36,37. These drive oceanic anomalies that are typically amplified by the Bjerknes feedback7,32, leading to the emergence of cold (La Niña-like) SST anomalies. The observed Pacific connection, which is closely reproduced by the C3S ensemble at 1-month initialization lead-time, intensifies progressively during the subsequent seasons. Interestingly, this Atlantic-Pacific relationship is quite predictable in the C3S ensemble (Fig. 4i, j). The SST-PC1 exhibits robust correlations with the July-September and October-December Niño3.4 index at lead times of 1-5 months. The regression estimates of the July-September Niño 3.4 SST variability from the SST-PC1 are of similar magnitudes compared to the observational value of 0.42 K up to 4-month lead-time in both seasons (Fig. 4i, j). The CMIP5 and CMIP6 ensembles depict a weak connection between the MCA1 mode and regional precipitation and the equatorial Pacific SST anomalies (Supplementary Fig. S7; Table S1).

a–h Anomalies of SST (color-scale, stipples indicate statistical significance), precipitation (contour at an interval of 0.3 mm day-1), and wind stress (arrows, only significant vectors are shown) for the three-month seasons indicated on the top-left corner of each panel regressed on the SST-PC1 using observations (left panels) and the C3S ensemble at 1-month initialization lead-time (right panels). i, j SST-PC1 correlation (left axis) and regression (right axis) with Niño 3.4 index in the C3S ensemble for the indicated seasons. The dashed red and blue lines in panels (i–j) denote the observed values; the black ticks denote the statistical significance of the correlations at the 95% confidence level.

The time-lagged connection between the equatorial Atlantic and Pacific Oceans remains a contentious issue38,39. Here a 36-month lagged correlation between the observed Niño3.4 index and SST-PC1 shows a robust correlation during the in-phase and leading phase of the Atlantic Niño (Fig. 5). Overall, the observed correlations are captured by the C3S ensembles at 1–4-month initialization lead-times, which are generally more skillful (Figs. 2 and 3). The less skillful 5–6-month lead times, representing the December and January initializations, display robust Niño3.4 lead correlations. The CMIP5 and CMIP6 ensembles do not show statistically significant correlations.

The SST-PC1 leads at positive lags, whereas the Niño 3.4 index leads at negative lags. The gray vertical bar denotes the Atlantic Niño year (0). Negative lag denotes the preceding year (−1), and positive lags the following year (+1). Circular ticks denote statistical significance at the 95% confidence level. Colored curves indicate predictions by C3S.

The MCA1 mode leads to anomalous precipitation across the tropics. For example, the corresponding observed SST-PC1 displays a high correlation with precipitation in three key continental regions and particularly in certain months: Northern Amazon (June), Guinea Coast (August), and Maritime Continent (August). These correlations are statistically significant at all 1-6-month lead times in the C3S forecast ensemble (Fig. 6a–c). Similar robust correlations are seen using the Atl3-SST directly rather than SST-PC1 (Fig. 6d–f), indicating an overall skillful prediction of the equatorial Atlantic–regional precipitation correlation in the C3S ensemble. Nonetheless, the magnitude of predicted anomalous precipitation is generally underestimated. This has been linked to mean-state biases and weaker response of precipitation in these regions to equatorial Atlantic SST anomalies in state-of-the-art climate models, which is particularly severe in the CMIP6 ensemble40 (Supplementary Fig. S7).

a–c SST-PC1 correlation (left axis) and regression (right axis) with regional precipitation averaged over the region and month indicated in each panel. The dashed red and blue lines denote the observed values; the black ticks denote the statistical significance of the correlations at the 95% confidence level. Panels d–f is similar to a–c but is based on the Atl3-SST index for June–July.

Discussion

The C3S ensemble’s provides skillful representation of the Atlantic Niño during the period 1994–2014, and its predictability and delayed impacts based on the MCA1 mode, offering hopes for improved societal applications across the tropics. The robust relationships between the atmosphere and ocean are largely due to internal interactions intrinsic to the Atlantic. Specifically, the Nino 3.4 index only displays robust lead correlation with the SST-PC1 at initialization lead times of 5–6 months, which is not seen in observations or at the shorter, more skillful lead times. Consistent with some previous studies12,32,36,37, the MCA1-derived Atlantic Niño is associated with tropical-scale atmospheric circulation. During the seasons following its peak phase, the MCA1-derived Atlantic Niño exhibits a robust correlation with ENSO’s negative phase in the tropical Pacific.

The Atlantic-Pacific connection is generally biased in the CMIP5 and CMIP6 ensembles, and there is no statistically significant correlation between the MCA1 mode and regional precipitation in these ensembles. This lack of teleconnection represents a major drawback in our understanding of the future impacts of the Atlantic Niño. As the present study is focused on multimodel ensemble-mean analysis, it is important to investigate the mechanisms that cause a lack of teleconnection using individual climate models in future studies.

The skillful predictions of the C3S ensemble may have partly come from the initialization process which ensures that the models’ atmospheric and oceanic states are more accurately aligned with observations. Thus, advancing societal applications of our approach demands the reduction in model errors and observational uncertainty, both of which remain key challenges in the equatorial Atlantic15,18.

Our study has focused on a relatively short time period, based on the availability of archived C3S ensembles, during which the variability in the equatorial Atlantic leads that in the equatorial Pacific. However, observations show that this relationship is non-stationary, and there are periods when the connection between the Atlantic and Pacific is reversed36. Moreover, the equatorial Atlantic experiences decadal variability41,42, which can significantly influence its interannual variability41. Thus, further research is needed to assess how these influences affect the region’s predictability and impacts highlighted in this study.

Methods

Observational datasets

We use satellite-derived observations of monthly Optimum Interpolation SST on 0.25° × 0.25° horizontal grids43 and Global Precipitation Climatology Center monthly precipitation on 2.5° × 2.5° grids44. Monthly SSH and ocean heat content dataset are taken from the Ocean Reanalysis System 5 (ORAS5) of the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts45. ORAS5 was originally constructed on horizontal 0.25° × 0.25° horizontal grids and 75 vertical levels (with level spacing increasing from 1 m in the surface layer to 200 m in the deep ocean), but the analyzed SSH has been reprocessed to 1° × 1° horizontal grids. The zonal and meridional surface wind stress is from the ERA5 reanalysis on horizontal 0.25° × 0.25° horizontal grids46.

CMIP5 and CMIP6 ensembles

We constructed the CMIP “historical” ensembles by selecting those models that provided both monthly SST and monthly precipitation in their first realization in the Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum (DKRZ) archive, yielding ensembles of 46 CMIP5 and 46 CMIP6 models21,22. 41 CMIP6 models and only 12 CMIP5 models archived the SSH (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). In the “historical” simulations, fully coupled global atmosphere-ocean models were forced by the time-varying observations of atmospheric greenhouse gases and aerosols.

C3S seasonal prediction ensemble

The C3S ensemble consists of state-of-the-art operational seasonal forecasts from eight centers (Supplementary Table S4), which are available for lead times of 1-6 months. The lead times denote the time interval between the forecast initialization and the target month being predicted. As we are interested in the Atlantic Niño which peaks in June, we chose June as the target month. A lead-time of one month implies that the forecast was initialized on 01 May, whereas a 6-month lead-time forecast was initialized on 01 December. We select one version of the forecasting systems from each center, leading to an ensemble of 196 seasonal prediction members. Here our analysis focuses on the multi-system ensemble, although, in addition, the spread of the individual prediction systems is also shown (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Leading mode extraction

We perform the MCA17 to extract the leading mode of precipitation variability in the meridional direction and equatorial SST variability in the zonal direction. MCA looks for patterns in the precipitation and SST fields that explain a maximum fraction of the covariance between them. We use latitude/longitude and calendar month as the dimensions. The datasets are first deseasonalized to remove the effects of the annual cycle. Then matrices are constructed of the meridional seasonal precipitation (year, calendar month, and 5°S–15°N) at 20°W over the western edge of the Atlantic Niño region and the zonal seasonal SST (year, calendar month, and 5°E–40°W) at the equator. The linear trends are removed on a month-by-month basis. The use of single longitude and latitude is for simplicity, and the main results remain unchanged using regional averages such as 20–25°W and 3°N–3°S.

Here, the leading mode (MCA1), which in observations represents the coupling between the meridional migration of the Atlantic-ITCZ and the Atlantic Niño, is also extracted for the CMIP5, CMIP6, and C3S ensemble members. Our analysis is focused on the MCA1 mode, which explains the highest covariance, and we have not checked if any ensemble member has an Atlantic Niño pattern that is not the leading mode. We made this choice because such an ensemble member is unrealistic by our definition. Furthermore, the southern boundary of precipitation used for the MCA is 5°S. Thus, strong variability further south of this latitude is excluded in our analysis as that constitutes an unrealistic feature of the state-of-the-art coupled models (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3).

Atlantic Niño, ENSO, and regional precipitation indices

The Atlantic Niño index is defined as the SST anomalies averaged over the eastern equatorial Atlantic region13 (3°N–3°S, 0–20°W), which is strongly correlated with the SST-PC1 of the MCA1 during the May-August peak phase of the Atlantic Niño variability (r = 0.97). To represent ENSO variability, we use the Niño 3.4 index, which is defined as the SST anomalies averaged over the equatorial Pacific region (5°N−5°S, 120− 170°W). The precipitation indices are defined as the regional averaged precipitation anomalies over the Northern Amazon (0–10°N, 50–80°W), Guinea Coast (5–10°N, 20°E–15°W), and Maritime Continent (10°S–5°N, 120–160°E), where robust connections to the Atlantic Niño are found.

Analysis periods

Two analysis periods have been used due to differences in the temporal coverage of the CMIP5, CMIP6, and C3S ensembles. First, the common period of high-resolution satellite-derived observations of SST and of historical CMIP5 and CMIP6 ensembles (1982–2004) is analyzed. Then, the C3S multi-system seasonal prediction ensemble is analyzed for the period 1994–2014 which is archived by all the prediction systems. In both cases, the observational analysis covers exactly the same period to allow for a direct comparison.

Statistical methods

For comparison with observations, the CMIP and C3S ensemble members have been remapped to the grids on which the observations are provided. The long-term means and linear trends are removed from the monthly variables allowing us to focus on the interannual variability. The MCA1 and associated precipitation-PC1 and SST-PC1 are first calculated from the individual ensemble members. The patterns are shown from the regressions of the zonal and meridional fields onto these PC1s. The regression Hovmöller plots and PC1s are then averaged to determine the ensemble-means.

A two-tailed Student’s t-test is applied to assess the statistical significance of regressions and correlations. The time series and Hovmöller patterns were first tested for autocorrelation, and the degrees of freedom were adjusted in determining the reference statistical significance31 using observational datasets. The statistical significance is marked at the 95% confidence level. The statistical significance stipples in observations are plotted over the ensembles for comparison.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed are from publicly available sources as follows: ERA5, ORAS5 and C3S ensembles (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets), SST (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.oisst.v2.highres.html), precipitation (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.gpcp.html). The CMIP5 and CMIP6 are publicly available via the Earth System Grid Federation (https://esgf-data.dkrz.de/projects/cmip6-dkrz).

References

Jin, E. K. et al. Current status of ENSO prediction skill in coupled ocean–atmosphere models. Clim. Dyn. 31, 647–664 (2008).

Barnston, A. G., Tippett, M. K., Ranganathan, M. & L’Heureux, M. L. Deterministic skill of ENSO predictions from the North American Multimodel Ensemble. Clim. Dyn. 53, 7215–7234 (2019).

Zhao, S. et al. Explainable El Niño predictability from climate mode interactions. Nature 630, 891–898 (2024).

Wu, Y. & Tang, Y. Seasonal predictability of the tropical Indian Ocean SST in the North American multimodel ensemble. Clim. Dyn. 53, 3361–3372 (2019).

Zhao, S. et al. Improved predictability of the Indian Ocean dipole using a stochastic dynamical model compared to the North American Multimodel Ensemble Forecast. Wea. Forecast. 35, 379–399 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. Forecasting the Indian Ocean Dipole with deep learning techniques. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094407 (2021).

Cai, W. et al. Pantropical climate interactions. Science 363, eaav4236 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Monthly to seasonal prediction of tropical Atlantic sea surface temperature with statistical models constructed from observations and data from the Kiel Climate Model. Clim. Dyn. 54, 1829–1850 (2020).

Li, X., Tan, W., Hu, Z.-Z. & Johnson, N. C. Evolution and prediction of two extremely strong Atlantic Niños in 2019–2021: Impact of Benguela warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104215 (2023).

Wang, R., Chen, L., Li, T. & Luo, J.-J. Atlantic Niño/Niña Prediction Skills in NMME Models. Atmosphere 12, 803 (2021).

Lübbecke, J. F. et al. Equatorial Atlantic variability—Modes, mechanisms, and global teleconnections. WIREs Clim. Change 9, e527 (2018).

Keenlyside, N. S. & Latif, M. Understanding equatorial Atlantic interannual variability. J. Clim. 20, 131–142 (2007).

Zebiak, S. E. Air-sea interaction in the equatorial Atlantic region. J. Clim. 6, 1567–1586 (1993).

Carton, J. A., Cao, X., Giese, B. S. & Da Silva, A. M. Decadal and interannual SST variability in the tropical Atlantic ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 26, 1165–1175 (1996).

Foltz, G. R. et al. The tropical Atlantic observing system. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 206 (2019).

Lübbecke, J. F. & McPhaden, M. J. A comparative stability analysis of Atlantic and Pacific Niño Modes. J. Clim. 26, 5965–5980 (2013).

Bretherton, C. S., Smith, C. & Wallace, J. M. An intercomparison of methods for finding coupled patterns in climate data. J. Clim. 5, 541–560 (1992).

Nnamchi, H. C., Latif, M., Keenlyside, N. S., Kjellsson, J. & Richter, I. Diabatic heating governs the seasonality of the Atlantic Niño. Nat. Commun. 12, 376 (2021).

Richter, I. et al. Phase locking of equatorial Atlantic variability through the seasonal migration of the ITCZ. Clim. Dyn. 48, 3615–3629 (2017).

Pottapinjara, V., Girishkumar, M. S., Murtugudde, R., Ashok, K. & Ravichandran, M. On the relation between the Boreal Spring position of the Atlantic intertropical convergence zone and Atlantic zonal mode. J. Clim. 32, 4767–4781 (2019).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Fasullo, J. T. & Gent, P. R. On the relationship between regional ocean heat content and sea surface height. J. Clim. 30, 9195–9211 (2017).

Crespo-Miguel, R., Polo, I., Mechoso, C. R., Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. & Cao-García, F. J. ENSO coupling to the equatorial Atlantic: Analysis with an extended improved recharge oscillator model. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 1001743 (2023).

Okumura, Y. & Xie, S. Some overlooked features of tropical Atlantic climate leading to a New Niño-like phenomenon. J. Clim. 19, 5859–5874 (2006).

Vallès-Casanova, I., Lee, S.-K., Foltz, G. R. & Pelegrí, J. L. On the spatiotemporal diversity of Atlantic Niño and associated rainfall variability over West Africa and South America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087108 (2020).

Davey, M. et al. STOIC: a study of coupled model climatology and variability in tropical ocean regions. Clim. Dyn. 18, 403–420 (2002).

Richter, I. & Xie, S.-P. On the origin of equatorial Atlantic biases in coupled general circulation models. Clim. Dyn. 31, 587–598 (2008).

Richter, I. Climate model biases in the eastern tropical oceans: causes, impacts and ways forward. WIREs Clim. Change 6, 345–358 (2015).

Zuidema, P. et al. Challenges and prospects for reducing coupled climate model SST biases in the Eastern Tropical Atlantic and Pacific Oceans: The U.S. CLIVAR Eastern Tropical Oceans Synthesis Working Group. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 97, 2305–2328 (2016).

Bretherton, C. S., Widmann, M., Dymnikov, V. P., Wallace, J. M. & Bladé, I. The effective number of spatial degrees of freedom of a time-varying field. J. Clim. 12, 1990–2009 (1999).

Liu, S., Chang, P., Wan, X., Yeager, S. G. & Richter, I. Role of the maritime continent in the remote influence of Atlantic Niño on the Pacific. Nat. Commun. 14, 3327 (2023).

Chikamoto, Y., Johnson, Z. F., Wang, S.-Y., McPhaden, M. J. & Mochizuki, T. El Niño–Southern Oscillation evolution modulated by Atlantic forcing. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125, e2020JC016318 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Emergence of the central Atlantic Niño. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi5507 (2023).

Kucharski, F. et al. A Gill–Matsuno-type mechanism explains the tropical Atlantic influence on African and Indian monsoon rainfall. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 135, 569–579 (2009).

Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. et al. Are Atlantic Niños enhancing Pacific ENSO events in recent decades?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L20705 (2009).

Ding, H., Keenlyside, N. S. & Latif, M. Impact of the Equatorial Atlantic on the El Niño Southern Oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 38, 1965–1972 (2012).

Jiang, F. et al. Resolving the tropical Pacific/Atlantic interaction conundrum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103777 (2023).

Richter, I. et al. Comment on “Resolving the tropical Pacific/Atlantic interaction conundrum” by Feng Jiang et al. (2023). Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL111563 (2024).

Nworgu, U. C. et al. Divergent future change in South Atlantic Ocean Dipole impacts on regional rainfall in CMIP6 models. Environ. Res. Clim. 3, 035002 (2024).

Martín-Rey, M. et al. Is there evidence of changes in tropical Atlantic variability modes under AMO phases in the observational record?. J. Clim. 31, 515–536 (2018).

Nnamchi, H. C. et al. A satellite era warming hole in the equatorial Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125, e2019JC015834 (2020).

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the Daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (DOISST) Version 2.1. J. Clim. 34, 2923–2939 (2021).

Huffman, G. J. et al. The New Version 3.2 Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Monthly and Daily Precipitation Products. J. Clim. 36, 7635–7655 (2023).

Zuo, H., Balmaseda, M. A., Tietsche, S., Mogensen, K. & Mayer, M. The ECMWF operational ensemble reanalysis–analysis system for ocean and sea ice: a description of the system and assessment. Ocean Sci. 15, 779–808 (2019).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) grant 456490637. The. CMIP5 and CMIP6 outputs were accessed from the Levante supercomputer at the DKRZ and. analyzed on the HLRN machine under shk00018 project resources.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.C.N. designed the concept, performed the analysis, and wrote the initial draft. M.L. contributed to interpretation of the results and improvement of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nnamchi, H.C., Latif, M. Predictable equatorial Atlantic variability from atmospheric convection-ocean coupling. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 149 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01041-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01041-9

This article is cited by

-

Atlantic Niño increases early-season tropical cyclone landfall risk in Korea and Japan

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)