Abstract

The Warm Arctic–Cold Eurasian pattern (WACE) is a pair of opposing surface air temperature anomalies over the polar region and the midlatitude Eurasian continent, which is usually associated with Arctic Sea ice melt and midlatitude extreme weather. The Southern Annular Mode (SAM) is the leading mode of atmospheric variability in the Southern Hemisphere. Here we show evidence of an inter-hemispheric connection between SAM and WACE during boreal winter. A positive SAM leads to a negative WACE (and vice versa) 30–40 days later. This lagged remote influence of SAM is transmitted via a Rossby wave that crosses the equator in the eastern Pacific and tropical Atlantic. The ensuing WACE temperature pattern is then amplified by the greenhouse effect associated with the local humidity response. SAM also leads to a convection anomaly in the equatorial Atlantic which generates a Northern Hemisphere Rossby wave that reinforces WACE. The link between SAM and WACE revealed here indicates a dynamical origin for WACE. This long-distance teleconnection, and the lagged association between SAM and WACE may be relevant for subseasonal-to-seasonal predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The “warm Arctic–cold continent” (WACC) pattern is a low frequency temperature variation observed in the Northern Hemisphere winter, with Arctic warming and continental cooling1,2,3,4,5. It can manifest in the form of a warm Arctic–cold Eurasian pattern3,6,7,8 (WACE) or a warm Arctic–cold North American pattern9,10,11,12,13 (WACNA). The WACC has been associated with Arctic Sea ice loss and extreme winter weather14. Possible mechanisms for the generation of WACC include the atmospheric response to changes in Arctic Sea ice and snow cover3,4,7,14,15,16,17,18,19, and internal atmospheric dynamics9,13,20,21,22,23.

The Southern Annular Mode (SAM), also known as the Antarctic Oscillation, is the dominant mode of atmospheric variability in the Southern Hemisphere. It has a mainly zonally symmetric or annular structure, with geopotential height anomalies of opposite signs in Antarctica and the middle latitudes24,25,26,27. The SAM is associated with a latitudinal shift of air mass and westerly wind and impacts on Southern Hemisphere weather and climate28,29,30,31,32. Influences of the SAM on Northern Hemisphere climate have also been reported. For example, the SAM was found to affect Indian summer monsoon precipitation33,34, and climate variability in East Asia35,36,37,38,39. Most of these studies suggest that such an inter-hemispheric influence is on seasonal or multi-seasonal time scales and is related to changes in sea surface temperature over the Southern Ocean. In this paper we will explore a more direct link between atmospheric dynamics in the Southern and Northern Hemispheres, specifically SAM and WACE, through wave propagation.

The meridional propagation of Rossby waves depends on the structure of the basic state zonal wind. Wave propagation occurs in midlatitude westerly flow, and the equatorial zone of easterly wind acts as a barrier to Rossby waves40. However, the zonal wind near the equator is not uniformly easterly, and cross-equator wave (CEW) propagation is possible in westerly regions during the boreal winter season41,42. Li et al.43 analyzed cross-equatorial Rossby wave propagation and its “barriers” and “windows” and found that wave propagation from Southern Hemisphere to Northern Hemisphere mostly happens in boreal winter via the eastern Pacific and equatorial Atlantic. Stationary wave modeling by Braga et al.44 shows that Rossby waves excited by the Southern Atlantic convergence zone can propagate across the equator over the Atlantic Ocean to influence North Africa and Asia.

In this study, we examine the inter-hemispheric link between SAM and WACE on an intraseasonal time scale in boreal winter. We aim to provide a novel explanation for the generation of WACE, a major surface air temperature variability pattern in the Northern Hemisphere which interacts with Arctic sea ice and midlatitude extreme weather. We present the observed lagged connection between WACE and SAM and investigate its underlying mechanism. Additionally, we discuss the role of water vapor in reinforcing this connection. The contributions of CEWs and tropical convection are analyzed and further explored through numerical experiments.

Results

Lagged connection between SAM and WACE

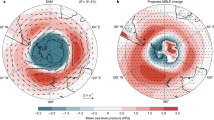

Based on the ERA5 reanalysis data for extended boreal winter (NDJFM) over the 44-year period from 1979/1980 to 2022/2023, the WACE is identified as the second EOF (EOF2) of pentad T2m anomalies over the region of 20°W–150°E, 20°–90°N, which accounts for 14.6% of the total variance (Fig. 1a). We use the corresponding PC2 as the WACE index. The WACE pattern is characterized by a meridional dipole with temperature anomalies of opposite signs over the Arctic and midlatitude Eurasia. The first EOF (EOF1) has a similar pattern to EOF2 but with action centers at higher latitudes (not shown), related to the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), and these two EOFs together tend to represent a propagating oscillation3,45. EOF3 accounts for 8.8% of the total variance, which is well separated from EOF2 according to the criterion of North et al.46. It was found in previous studies that the WACE varies on multiple time scales including intraseasonal4, interannual to decadal7,13 and long-term climate change, and is related to sea ice variations in the Barents–Kara Sea region20,21.

a The WACE pattern represented as EOF2 of T2m, shown as regressions of pentad T2m onto PC2, where the EOF is performed for the pentad T2m anomalies in NDJFM in the Northern Hemisphere middle-high-latitude region outlined by the green rectangle. b The SAM pattern represented as EOF1 of Z200, shown as regressions of monthly Z200 onto PC1, where the EOF is performed for the monthly Z200 anomalies in NDJFM in the Southern Hemisphere from 20–90°S. The magnitude corresponds to one standard deviation of the corresponding PC. The contour interval is 1 °C for (a) and 10 m for (b). Contours with negative values are dashed. The zero contour is not plotted. The percentage of variance explained by the EOF mode is indicated above each panel. c Lead-lag correlation between the WACE and the SAM indices. The horizontal axis is lag in pentads, where a negative (positive) value means that SAM leads (lags) WACE. The shading indicates the confidence interval of 2.5%–97.5% based on a bootstrapping method with 5000 resamples of each time series.

The SAM pattern is represented by EOF1 of the monthly Z200 anomalies in NDJFM over the Southern Hemisphere (Fig. 1b), which features geopotential height anomalies of opposite signs over the Antarctic region and midlatitudes. It is mainly zonally symmetric, although a zonal wave-3 feature is evident with action centers near 90°E, 180° and 45°W. This pattern is consistent across different reanalysis datasets, pressure levels, and time scales, including daily, monthly or seasonal mean sea-level pressure or geopotential heights25,28,29,30,47. The pentad SAM index is obtained by projecting the pentad Z200 anomaly onto the SAM pattern.

Lead-lag correlations between the SAM and WACE indices are calculated to investigate the association between the two large-scale patterns in the Southern and Northern Hemispheres on the intraseasonal time scale (Fig. 1c). When SAM leads WACE by 5–9 pentads there is a negative correlation which peaks at about 7 pentads, indicating that a positive phase of SAM leads to a negative phase of WACE (and vice versa) by about 30–40 days. Although the correlation is weak (−0.12), it is statistically significant, based on a large sample size (44 years × 30 pentads = 1320), according to both the bootstrapping test (shown in Fig. 1c) and a Student’s t test (at the 0.01 level) after the number of degrees of freedom is reduced due to autocorrelation48.

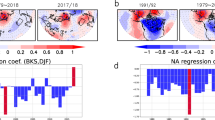

To illustrate the time evolution of the T2m anomaly in the Northern Hemisphere associated with SAM, regressions of T2m with respect to the SAM index at time lags of 1, 3, 5 and 7 pentads are shown in Fig. 2a. At lag = 1, positive surface temperature anomalies are seen over much of North America. Together with the cold anomalies near the high-latitude Chukchi–Bering Sea region, this temperature pattern resembles a negative phase of WACNA. Note that although one pentad is a short time scale for a direct inter-hemispheric effect, the WACNA pattern also presents as a mode of internal variability23, so the regression analysis will naturally pick up a preceding component of this internal variability for signals that respond directly to the SAM at later lags. Starting at about lag = 3 pentads, negative T2m anomalies develop in the Arctic east of Greenland and positive T2m anomalies emerge and develop in midlatitude Eurasia, leading to a pattern similar to a negative phase of the WACE, which intensifies and reaches its maximum magnitude at lags of 5 to 7 pentads.

a Lagged regressions of T2m in the Northern Hemisphere with respect to the SAM index when SAM leads by 1, 3, 5 and 7 pentads. b Lagged regressions of sea ice concentration in the North Atlantic–Arctic sector with respect to the SAM index. The magnitude corresponds to one standard deviation of the SAM index. The unit is °C for (a) and % for (b). Stippling indicates that the regression is significant at the 95% confidence level based on a bootstrapping resampling method.

Corresponding to the negative T2m anomalies in the Arctic region 7 pentads after a positive SAM, there is statistically significant increase of sea ice concentration over the Barents Sea and Greenland Sea region (Fig. 2b). Previous studies have explored the complex relationship between the atmospheric circulation and the Arctic sea ice, and there is an ongoing debate on whether the WACE pattern is forced by changes in sea ice3,6,7,23,49. Our result indicates that sea ice changes can be a response to the atmospheric anomaly associated with SAM variability.

Lagged regressions of Z200 with respect to the SAM index (Supplementary Fig. S1) show a wave train that starts to develop at about lag = 3, with alternating positive and negative height anomalies across the North Atlantic and Eurasian region. Negative Z200 anomalies over the Arctic coast of Europe and positive anomalies over midlatitude Eurasia intensify and reach their maximum amplitudes at lags 6 and 7, associated with the development of the WACE (Fig. 2a). Lagged regressions of geopotential height at other levels, e.g., Z500 and Z850, have a similar development in the Northern Hemisphere extratropics (not shown), indicating that this wave train is equivalent-barotropic in nature.

Analysis of temperature advection at 850 hPa shows that the WACE temperature pattern associated with the SAM largely owes its existence to the horizontal advection of mean temperature by circulation anomalies (Supplementary Fig. S2). About three pentads after a positive SAM, cold advection is observed over the Barents–Kara Sea region and there is warm advection on the midlatitude Eurasian continent. Similar results were obtained in previous studies that describe the role of temperature advection in large-scale temperature anomaly patterns23,50,51,52. The dominant term in the lower troposphere is the meridional wind perturbation advecting cold air from the north and warm air from the south.

Contribution of water vapor to WACE

According to the Clausius–Clapeyron relationship, warmer air has greater capacity to host water vapor53. Lagged regressions of total column water vapor with respect to the SAM index show that from lag = 3 pentads, statistically significant dry and wet anomalies develop in the Arctic and midlatitude Eurasia, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3). They peak at around lags 6 and 7. Dry and wet anomalies are associated with the Arctic cold and mid-latitude Eurasia warm temperatures. As for temperature, horizontal advection contributes to these water vapor anomalies. This can be seen from advection of specific humidity at 850 hPa (Supplementary Fig. S4). About three pentads after a positive SAM, negative humidity advection is seen over the Barents–Kara Sea region and there is positive advection on the midlatitude Eurasian continent.

Water vapor acts as a greenhouse gas, and humidity anomalies tend to have positive feedback to the surface temperature, especially in the high-latitude regions54,55,56. Shown in Fig. 3 is the lagged regression of surface downward longwave radiation from the atmosphere and clouds with respect to the SAM index. An anomalous dry air over the Arctic and humid air over midlatitude Eurasia occurring 5–7 pentads after a positive SAM can be seen to result in local anomalies of longwave radiation. So, surface heating is reduced over the Arctic and increased over Eurasia, further amplifying the negative phase of the WACE pattern.

The magnitude corresponds to one standard deviation of the SAM index. The unit is W m−2. Stippling indicates that the regression is significant at the 95% confidence level based on a bootstrapping resampling method. Positive and negative values represent downward and upward thermal radiation, respectively.

Mechanisms

CEW propagation can be represented by the stationary wavenumber, Ks, as defined in Eq. (3) at 200 hPa based on the ERA-5 reanalysis in the extended boreal winter, shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. In the gray regions, \({Ks}\) is undefined because the basic state zonal wind becomes zero or easterly (\(\bar{U}\le 0)\), wave propagation does not occur. Areas shown in white denote a negative meridional gradient of absolute vorticity (\({\bar{\zeta }}_{\varphi }\)), so continuous wave propagation is not permitted. Stationary Rossby waves propagating towards these regions are reflected towards higher values of \({Ks}\). The general features are consistent with previous studies44,57,58. CEW propagation from the Southern Hemisphere to the Northern Hemisphere is possible in two regions: the eastern Pacific and the equatorial Atlantic. These regions are purple in Supplementary Fig. S5 and correspond to relatively small-scale stationary waves. After a wave traverses across the equator, it can take two possible paths to propagate in the Northern Hemisphere: (1) the southern path, which is eastward from the tropical North Atlantic, across North Africa to East Asia, or (2) the northern path, which is northeastwards across the North Atlantic to high-latitude Eurasia. Similar equatorial windows and paths for stationary Rossby wave propagation from the Southern Hemisphere to the Northern Hemisphere in the boreal winter have been identified in Li et al.43 using a wave ray ensemble method.

Figure 4 shows lagged regressions of 200-hPa streamfunction with respect to the SAM index. From about lag = 3 pentads, wave trains are established from the Southern Hemisphere across the equator near the eastern Pacific and Atlantic, as indicated schematically by the black arrows in the panel of lag = 3 pentads. To trace the Rossby wave propagation, wave activity flux59 at 200 hPa is diagnosed (Supplementary Fig. S6a). Consistent with Ks, wave propagation is observed along two paths. Some anomaly centers are lined up through the tropical Atlantic Ocean, the North African continent, India and towards East Asia. A similar wave propagation has already been documented by Braga et al.44 originating from the South Atlantic Convergence Zone. Additionally, there is a higher latitude branch that develops along a great circle path across the North Atlantic towards Eurasia. It has a positive 200-hPa eddy streamfunction anomaly center around Greenland, a negative center near northern Europe and a downstream positive center over midlatitude Eurasia. These anomaly centers intensify and reach peak amplitude at lags 5–7. The circulation anomaly associated with this wave train is responsible for the temperature and moisture advection that leads to a negative phase of the WACE pattern.

The magnitude corresponds to one standard deviation of the SAM index. The interval is 0.3 × 106 m2 s−1). Positive values are in solid red while negative in dashed blue. The zero contour is omitted. Shading indicates that the regression is significant at the 95% confidence level based on a bootstrapping resampling method. The black arrows in the panel of lag = 3 pentads indicate schematically Rossby wave propagation.

The 200-hPa streamfunction at lag = 1 has a positive anomaly over eastern Canada (Fig. 4), consistent with the positive surface air temperature anomalies which resembles a negative WACNA (Fig. 2). This positive streamfunction anomaly weakens quickly with time. Over the North Atlantic, a Rossby wave train starts to develop from lag = 3 with the influence from the Southern Hemisphere, which leads to a negative WACE. As observed in previous studies11,60, a negative WACE tends to follow a negative WACNA. The SAM impact as discussed here provides a possible explanation for such an intercontinental link.

Simulations have been performed with a simple dynamical model known as the Simplified General Circulation Model (SGCM), described in Methods. The model is used to diagnose the linear wave response on a fixed NDJFM basic state to an imposed vorticity perturbation. The perturbation is related to SAM variability, and it is introduced as a forcing term in the vorticity equation, collocated with one of the midlatitude SAM action centers at 45°S, 90°E (Fig. 1b). The evolution of the 200-hPa eddy streamfunction response from days 3 to 15 at a 4-day interval is shown in Fig. 5. CEW propagation from the Southern Hemisphere can be discerned in the eastern Pacific and Atlantic sectors, as indicated by the black arrows in the panel of day 15 (the wave activity flux is shown in Supplementary Fig. S6b). The southern wave train across the tropical Atlantic, North Africa and India is established in about 7 days. The northern branch of the wave propagation across the North Atlantic to northern Europe is established in about 2 weeks. The simulated CEW propagation and wave train paths are consistent with what we expect from the stationary Rossby wave number, Ks, shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. By comparing the day 15 response in Fig. 5 with lag = 3 regression in Fig. 4, the simulated wave train paths in general agree with the observations, and the positive-negative-positive centers over the North Atlantic, northwestern Europe and midlatitude eastern Europe roughly match the observed 200-hPa streamfunction anomalies that follow the positive phase of SAM. There are, however, some discrepancies in the locations of anomaly centers along the wave paths. The anomaly centers of the simulated wave trains are shifted upstream relative to the observations. For example, the simulated positive center in the North Atlantic and negative center over northwestern Europe are seen about 15° south and 15° west of those in the observations. Interestingly, atmospheric responses in the Northern Hemisphere to vorticity forcing located at other longitudes along 45°S have a very similar pattern, with the same two wave trains described above. Two examples of this are shown in Supplementary Figs. S7 and S8, which depict the response to vorticity forcing at 180° and 45°W, corresponding to the other two SAM action centers. To explore the sensitivity of the model response to the longitude of vorticity forcing, a set of linear experiments are performed with the forcing located at different longitudes along 45°S with a 10° interval. For each of these experiments, the Northern Hemisphere 200-hPa eddy streamfunction at day 15 between 5° and 85°N is projected onto the result with the forcing at 90°E (i.e., day 15 response in Fig. 5). The projection is calculated as a spatial covariance, normalized by the spatial variance of day 15 in Fig. 5. It thus represents a response amplitude for different vorticity forcing sources, relative to the amplitude of the response with the forcing at 90°E. This calculation is presented in Supplementary Fig. S9 as a function of the longitude of the forcing center. The projection is greater than 0.73 for all longitudes, indicating that the Northern Hemisphere response has a common pattern and is relatively insensitive to the longitudinal location of the 45°S vorticity forcing. This implies that vorticity forcing located anywhere in the Southern Hemisphere midlatitude zone of the SAM would induce a similar CEW propagation, with a similar influence on the Northern Hemisphere. The Southern Hemisphere vorticity forcing that corresponds to positive SAM will generate negative geopotential height anomalies in northwestern Europe, and positive anomalies in midlatitude Europe. This in turn leads to a negative phase of the WACE.

Extratropical atmospheric variability has been observed to propagate into the tropics and influence convective activity61,62. It would be interesting to see if the CEW propagation associated with SAM can influence tropical Atlantic convective activity. If this is the case, the ensuing tropical convection anomaly may provide an additional thermal forcing that could also influence the extratropical circulation.

Lagged regression of OLR to the SAM index is shown in Supplementary Fig. S10. OLR in the tropical region is closely related to deep convection. The SAM-related Southern Hemisphere extratropical waves that propagate to the tropical Atlantic result in positive OLR anomalies that correspond to reduced convection in the equatorial Atlantic. The signal is statistically significant, especially at lags of 3 to 7 pentads. This reduced tropical convection represents anomalous diabatic cooling, and thus a thermal forcing.

We have used the SGCM to perform a further linear integration with the same simulated NDJFM basic state, but this time the perturbation forcing is a deep tropospheric cooling in the equatorial Atlantic. The Rossby wave source (RWS) as defined by Eq. (5) at 200-hPa on day 1 is shown in Supplementary Fig. S11. The first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (5), which is the generation of vorticity by the anomalous divergence, is the dominant term. The subtropical RWS that extends from the eastern North Atlantic to north Africa generates waves that propagate along the southern wave train path. In addition, two RWS centers can be seen over the western and midlatitude North Atlantic, which likely induce waves that propagate northeastwards along the northern pathway. The model 200-hPa streamfunction response is shown in Fig. 6. A wave train develops quite quickly in the Northern Hemisphere subtropics and propagates eastward along the southern path where Ks is large. From about day 7, we see a positive 200-hPa streamfunction anomaly center developing over the middle North Atlantic. It intensifies at day 11, and a negative center at day 15 near the northwestern coast of Europe. These anomalies are parts of a wave train propagating northeastwards from the subtropical western Atlantic. The action centers of this wave train are collocated and in phase with those of the CEW propagation associated with SAM (Fig. 5). The wave activity flux at day 15 is shown in Supplementary Fig. S6c. So, it appears that a contribution from an equatorial Atlantic cooling anomaly, initially induced by SAM, may reinforce the CEW circulation pattern that contributes to the WACE.

Discussions

An inter-hemispheric connection has been identified between the SAM in the Southern Hemisphere and the WACE in the Northern Hemisphere. This occurs on an intraseasonal time scale during extended boreal winter, as revealed by 44 years of the ERA-5 reanalysis data. A positive phase of the SAM precedes a negative phase of the WACE by 30–40 days. This SAM teleconnection leads to Northern Hemisphere flow anomalies and the attendant temperature advection that contribute to WACE variability. Moisture advection associated with these flow anomalies also leads to a total column water vapor distribution that reenforces the WACE through the greenhouse effect.

CEW propagation is the main mechanism for the lagged connection between WACE and SAM. Rossby waves in the Southern Hemisphere associated with the SAM variability propagate across the equator in the eastern Pacific and equatorial Atlantic, where the upper tropospheric zonal wind is westerly. In agreement with the stationary Rossby wavenumber distribution, the CEW takes two paths to influence the Northern Hemisphere. The southern path tracks eastwards through North Africa to East Asia, and the northern path tracks northeastwards across the North Atlantic to Europe. The northern path manifests as a wave train with action centers of opposite signs near the Barents–Kara Sea region and midlatitude Eurasia, coherent with the WACE pattern. A schematic diagram summarizing the connection between SAM and WACE through CEW propagation and the relay effect of tropical convection is given in Fig. 7.

A positive phase of SAM, with negative (red dashed contours) and positive (blue solid contour) geopotential height anomalies in the Southern Hemisphere polar and midlatitude regions, triggers across-equator wave (CEW) propagation in the eastern Pacific and Atlantic (black arrows). The northern branch of the wave train propagates northeastwards over the North Atlantic and high-latitude Europe, forming positive (solid circles) and negative (dashed circle) geopotential height anomalies in the upper troposphere. Such circulation anomalies lead to cold (blue colored) and warm (red colored) temperatures near the surface, corresponding to a negative WACE. The CEW suppresses deep convection in the equatorial Atlantic, which acts as an anomalous thermal forcing and induces Rossby wave sources in the extratropical North Atlantic (stippling areas). This generates a secondary wave train (red arrow) that is in phase with the original northern branch of CEW and reinforce WACE.

A set of linear experiments was conducted to study the atmospheric response to idealized Southern Hemisphere vorticity perturbation using a global dynamical atmospheric model with the NDJFM climatological flow. When the vorticity perturbation is located at 45°S, corresponding to the SAM midlatitude action center, a Rossby wave response propagates to the tropics, and crosses the equator over the eastern Pacific and equatorial Atlantic. The simulated CEW propagation appears similar to observed lagged regressions, reproducing both the southern and northern paths for wave trains in the Northern Hemisphere. The southern wave train is established in about 7 days, while the northern one develops after about 2 weeks. The northern pattern has action centers over the North Atlantic, the Arctic and Europe with a similar distribution to observed regressions.

The SAM-related CEW also generates tropical convection anomalies in the equatorial Atlantic. These tropical convection anomalies act as thermal forcing which induces extratropical Rossby waves that propagate along similar southern and northern paths as the CEW. The action centers along the northern path in the North Atlantic and Eurasia coincide with those of the SAM-related CEW propagation. Waves emanating from anomalous tropical Atlantic convection thus enhance the circulation anomalies that contribute to the WACE pattern. Tropical convention thus acts as a relay between SAM and WACE. CEW activity can directly lead to WACE variability, but the influence of SAM on WACE is reinforced by the tropical convective relay.

In the dynamical simulation, the Northern Hemisphere high-latitude response to the Southern Hemisphere vorticity forcing (i.e., the northern path of the CEW) develops in about 2 weeks. This time scale is shorter than the observed delay, where the maximum WACE signal lags the SAM by about 30–40 days. There are several possible factors that can account for this difference in response time. Firstly, the SGCM is a dry model, and the numerical experiments are linear integrations, thus only linear processes are simulated. However, the atmospheric response to remote forcing can also alter synoptic-scale transient activity, and nonlinear interactions between transient eddies and the response could reinforce the response on a longer time scale23,63. Secondly, as discussed above, water vapor changes associated with SAM-related flow anomalies will feed back positively onto WACE variability. In addition, SAM variability leads to tropical Atlantic convection anomaly, with the associated thermal forcing acting as a tropical relay to enhance WACE related circulation anomalies. The observed 30–40-day lag time between WACE and SAM is likely determined by the combined contribution of the CEW propagation and these additional processes.

The model response in the Northern Hemisphere to vorticity forcing along the Southern Hemisphere middle latitude is robust and remarkably insensitive to the longitude of the forcing. The simulated CEW and wave train paths are consistent with the observations. However, along the northern wave train pathway across the North Atlantic to northern Europe, the simulated 200-hPa streamfunction anomaly centers are shifted southwestwards by about 15° latitude and longitude relative to the observations. This may be because there are processes missing from the SGCM as detailed above. Previous studies64,65 found that a Pacific-North American (PNA)-like pattern could be excited by a tropical thermal forcing at different locations in the Indian Ocean and western Pacific. Such a preferred response, which is insensitive to the forcing location, is determined by the horizontal structure of the mean flow. It appears that a similar mechanism exists for the atmospheric response to the SAM-related forcing. Given that the tropical “windows” for CEW are in fixed longitudinal ranges near the equatorial eastern Pacific and Atlantic, the wave train crossing the equator tends to be at a preferred phase no matter what longitude the forcing is located along 45°S. This is likely determined by the 2-dimensional structure of the mean flow.

This study reveals a statistically significant 30–40-day lagged association between SAM and one of the major temperature variability patterns in the Northern Hemisphere, the WACE. Our findings indicate that the SAM variability may contribute to subseasonal prediction of the WACE variability. Further work is planned to evaluate whether this inter-hemispheric teleconnection is captured in existing forecast systems.

Methods

The fifth generation of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) reanalysis66 (ERA-5) is used in this study. Variables analyzed include 2-meter air temperature (T2m), 200-hPa and 850-hPa zonal and meridional winds (u200, v200, u850 and v850), geopotential heights at 850-hPa, 500-hPa and 200-hPa (Z850, Z500 and Z200), and sea ice concentration. Streamfunction at 200-hPa is derived from u200 and v200. To analyse the contribution of water vapor to T2m variability, total column water vapor, specific humidity at 850-hPa (HU850), and surface downward long-wave radiation are utilized. To represent the tropical convection, the NOAA Interpolated Outgoing Longwave Radiation (OLR) data67, are also used. The analysis is performed with the daily averaged data for 44 extended winters from 1979/1980 to 2022/2023, where the extended winter refers to November to March (NDJFM), except for OLR for which data are available from 43 extended winters (1979/1980–2021/2022). The same procedure as described in Lin et al.23 is applied to isolate the intraseasonal variability. In short, the data are averaged over consecutive pentads (5-day periods), and each extended winter has 30 pentads starting from November 2–6 and ending at March 27–31. For leap years, the pentad of February 25 to March 1 has 6 days. A seasonal cycle is removed defined as the time mean and first two harmonics of the pentad climatology. The mean of each extended winter is then subtracted so that the resulting pentad anomaly does not include the interannual variability.

An empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis is performed on the pentad T2m anomaly over the WACE region (340°W–150°E, 20°–90°N). The data at each grid point is weighed by the square root of the cosine of the latitude before the EOF analysis to account for unequal areas in the grid. The second EOF mode (EOF2) corresponds to the WACE pattern. The normalized principal component of this mode (PC2) is used as an index to represent the WACE variability.

To identify the SAM spatial pattern, we perform an EOF analysis on monthly mean Z200 anomalies in the Southern Hemisphere (20°–90°S) for the extended boreal winter (NDJFM) after removing the monthly climatology. The SAM has a barotropic vertical structure and its identification is insensitive to the vertical level used. Here we use geopotential height at 200-hPa because Rossby waves tend to propagate near this level. The first EOF (EOF1) of Z200 represents the SAM. Then we project the pentad Z200 anomaly onto this SAM spatial pattern to obtain a time series, which is referred to as the SAM index after normalization. The SAM pattern is similar when the EOF analysis is performed on pentad mean Z200. Here we use monthly mean data to be consistent with previous studies27,47.

To analyze the link between the SAM and global circulation anomalies on the intraseasonal time scale, lead-lag regressions or correlations of the SAM index with different variables are calculated. Uncertainty is assessed using a bootstrapping resampling approach where the calculation is repeated at least 1000 times and the 2.5%–97.5% range is used to measure the confidence. To assess the sensitivity of our results to the definition of the SAM index, calculations have been repeated using the U.S. NOAA Climate Prediction Center daily Antarctic Oscillation index (https://ftp.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/cwlinks/), and the results are consistent with those presented in this paper.

Following previous studies23,51, to understand how the circulation anomalies lead to the WACE temperature anomaly, horizontal temperature (T) advection in the lower troposphere at 850-hPa is calculated as:

where \({u}^{{\prime} }\) and \({v}^{{\prime} }\) denote the anomalous zonal and meridional wind components derived from the lagged regression with respect to the SAM index, and \(\bar{T}\) the extended winter climatological mean temperature. \({T}_{{{\rm{adv}}}}\) is the advection of mean temperature by circulation anomalies. The advection of anomalous temperature by the mean flow is relatively weak and thus omitted. Similarly, horizontal moisture (specific humidity q) advection at 850-hPa is estimated as:

where \(\bar{q}\) is the extended winter climatological mean specific humidity.

To analyze Rossby wave propagation, the stationary wavenumber, Ks, is calculated over the global domain at 200 hPa, following Hoskins and Ambrizzi42, as:

where \({\bar{\zeta }}_{\varphi }\) is the meridional gradient of the time mean absolute vorticity, a the earth’s radius, and \(\bar{U}\) the extended winter climatological mean zonal wind.

To describe the propagation characteristics of a Rossby wave train, we estimate the horizontal component of wave activity flux at 200 hPa as defined by Takaya and Nakamura59, which is written as:

where the subscripts denote partial derivatives. \(\bar{{\bf{U}}}=\left(\bar{U},\bar{V}\right)\) is the basic-state wind vector, and \({\psi }^{* }\) the intraseasonal perturbation streamfunction. The W vector is typically parallel to the local group velocity of stationary Rossby waves.

To elucidate the wave propagation mechanism of the SAM-WACE connection, we use a dynamical model of the atmosphere known as the SGCM, described in several previous studies65,68,69,70. Briefly, this model is based on the primitive equation global spectral model of Hoskins and Simmons71, which consists of equations of vorticity, divergence, surface pressure and temperature. It has a scale-selective dissipation, and a level-dependent linear damping has been added for temperature and momentum. The model has a horizontal resolution of T31 and 10 vertical levels. In this study, the SGCM is used as a linear perturbation model about a time-independent basic state as described, for example, in Hall and Derome63 and Lin et al.62. We choose to use a basic state derived from a long integration of the SGCM itself, run in “simple GCM” mode. Essentially an empirically derived forcing can be used to replace processes that are not represented by the model’s dynamics and when forced in this way the model produces an acceptable time-dependent nonlinear solution much like a full GCM (for details see Hall72 and for other examples65,68,73 of this use of the SGCM). For the linear wave propagation study presented here, the basic state is derived from a long perpetual extended winter (NDJFM) integration (7200 days) of the simple GCM, which is in fact very similar to the observed NDJFM mean.

To explore the atmospheric response to SAM variability, 36 linear experiments are conducted with isolated vorticity perturbation sources placed along 45°S at a 10° longitudinal interval, corresponding to the positive phase of the SAM. The perturbation forcing is added to the vorticity equation at the beginning of integration and is kept in place for 10 days. It has an elliptical structure in the horizontal, with a semi-major axis of 28 degrees of longitude and a semi-minor axis of 8 degrees of latitude. The forcing is defined with a magnitude proportional to the squared cosine of the distance from the center, and a vertical profile of \(\pi \left(1-\sigma \right)\sin (\pi \left(1-\sigma \right))\), which peaks at \(\sigma\) = 0.35 with a vertically averaged vorticity forcing rate of 2.5 × 10−6 s−1 day−1. To investigate the atmospheric response to a thermal forcing corresponding to a reduced convection in the tropical Atlantic, an additional linear experiment is performed. This time, a negative thermal forcing (cooling) is added to the temperature equation and persists throughout the integration. This thermal forcing has the same spatial structure as the vorticity forcing described above, centered at the equator and 30°W, with a vertically averaged heating rate of −1.25 °C day−1. The linear model is integrated for 30 days starting from an initial condition that has no atmospheric perturbation.

To help understand the development of atmospheric extratropical response to a tropical thermal forcing perturbation, Rossby wave source (RWS) is calculated which is defined by Sardeshmukh and Hoskins70 as:

where \(\zeta\) is the absolute vorticity, and \({{\bf{v}}}_{\chi }\) divergent velocity, respectively. The overbar denotes the basic flow and the prime the perturbation. When plotting RWS, a spectral filter is applied to smooth the Rossby wave source fields, as described in Sardeshmukh and Hoskins74, which takes the form of \({e}^{-K{[n\left(n+1\right)]}^{2}}\) with \(K\) chosen so that the highest wavenumber spectral coefficients are multiplied by 0.1.

Data availability

All observational and reanalysis data applied in this study have been obtained from sources that are publicly available. The ERA5 reanalysis data are downloaded from the Climate Data Store of the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu. The OLR data are downloaded from the NOAA PSL, Boulder, Colorado, USA, from their website at https://psl.noaa.gov. The U.S. NOAA Climate Prediction Center daily Antarctic Oscillation index is downloaded from https://ftp.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/cwlinks/. The model output data in this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Overland, J. E., Wood, K. R. & Wang, M. Warm Arctic–Cold continents: climate impacts of the newly open Arctic sea. Polar Res. 30, 15787 (2011).

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014).

Mori, M., Watanabe, M., Shiogama, H., Inoue, J. & Kimoto, M. Robust Arctic sea-ice influence on the frequent Eurasian cold winters in past decades. Nat. Geosci. 7, 869–873 (2014).

Kug, J. S. et al. Two distinct influences of Arctic warming on cold winters over North America and East Asia. Nat. Geosci. 8, 759–762 (2015).

Sun, L. T., Perlwitz, J. & Hoerling, M. What caused the recent “warm Arctic, cold continents” trend pattern in winter temperatures? Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 5345–5352 (2016).

Mori, M., Kosaka, Y., Watanabe, M., Nakamura, H. & Kimoto, M. A reconciled estimate of the influence of Arctic sea-ice loss on recent Eurasian cooling. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 123–129 (2019).

Cohen, J., Furtado, J. C., Barlow, M., Alexeev, V. & Cherry, J. Arctic warming, increasing snow cover and widespread boreal winter cooling. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 014007 (2012).

Sorokina, S. A., Li, C., Wettstein, J. J. & Kvamstø, N. G. Observed atmospheric coupling between Barents Sea ice and the warm-Arctic cold-Siberian anomaly pattern. J. Clim. 29, 495–511 (2016).

Blackport, R., Screen, J. A., van der Wiel, K. & Bintanja, R. Minimal influence of reduced Arctic sea ice on coincident cold winters in mid-latitudes. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 697–704 (2019).

Lin, H. Subseasonal variability of North American wintertime surface air temperature. Clim. Dyn. 45, 1137–1155 (2015).

Lin, H. Predicting the dominant patterns of subseasonal variability of wintertime surface air temperature in extratropical Northern Hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 4381–4389 (2018).

Guan, W., Jiang, X., Ren, X., Chen, G. & Ding, Q. Role of atmospheric variability in driving the “warm-Arctic, cold continent” pattern over the North America sector and sea ice variability over the Chukchi-Bering Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088599 (2020).

Yu, B. & Lin, H. Interannual variability of the warm Arctic–cold North American pattern. J. Clim. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0831.1 (2022).

Cohen, J., Jones, J., Furtado, J. C. & Tziperman, E. Warm Arctic, cold continents: a common pattern related to Arctic sea ice melt, snow advance, and extreme winter weather. Oceanography 26, 150–160 (2013).

Park, H. L. et al. Dominant wintertime surface air temperature modes in the Northern Hemisphere extratropic. Clim. Dyn. 56, 687–698 (2021).

Deser, C., Tomas, R. A. & Peng, S. The transient atmospheric circulation response to North Atlantic SST and sea ice anomalies. J. Clim. 20, 4751–4767 (2007).

Honda, M., Inoue, J. & Yamane, S. Influence of low Arctic sea-ice minima on anomalously cold Eurasian winters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L08707 (2009).

Overland, J. E. & Wang, M. Large-scale atmospheric circulation changes are associated with the recent loss of Arctic sea ice. Tellus 62A, 1–9 (2010).

Francis, J. A. & Vavrus, S. J. Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid-latitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L06801 (2012).

Sigmond, M. & Fyfe, J. C. Tropical Pacific impacts on cooling North American winters. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 970–974 (2016).

Guan, W. et al. The leading intraseasonal variability mode of wintertime surface air temperature over the North American Sector. J. Clim. 33, 9287–9306 (2020).

Jin, C. H., Wang, B., Yang, Y. M. & Liu, J. “Warm Arctic–cold Siberia” as an internal mode instigated by North Atlantic warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, L086248 (2020).

Lin, H., Yu, B. & Hall, N. M. J. Origin of the warm Arctic–cold North American pattern on the intraseasonal time scale. J. Atmos. Sci. 79, 2571–2583 (2022).

Rogers, J. C. & van Loon, H. Spatial variability of sea-level pressure and 500 mb height anomalies over the Southern-Hemisphere. Mon. Weather Rev. 110, 1375–1392 (1982).

Gong, D. & Wang, S. Definition of the Antarctic oscillation index. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 439–532 (1999).

Limpasuvan, V. & Hartmann, D. Eddies and the annular modes of climate variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 3133–3136 (1999).

Thompson, D. W. & Wallace, J. M. Annular modes in the extratropical circulation. Part I: month-to-month variability. J. Clim. 13, 1000–1016 (2000).

Baldwin, M. P. Annular modes in global daily surface pressure. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 4115–4118 (2001).

Kidson, J. W. Principal modes of Southern Hemisphere low-frequency variability obtained from NCEP–NCAR reanalyses. J. Clim. 12, 2808–2830 (1999).

Hendon, H. H., Thompson, D. W. & Wheeler, M. C. Australian rainfall and surface temperature variations associated with the Southern Hemisphere annular mode. J. Clim. 20, 2452–2467 (2007).

Mbigi, D. & Xiao, Z. The Southern Annular Mode: its influence on interannual variability of rainfall in North Australia. Clim. Dyn. 62, 4455–4468 (2024).

Meneghini, B., Simmonds, I. & Smith, I. N. Association between Australian rainfall and the Southern Annular Mode. Int. J. Climatol. 27, 109–121 (2007).

Prabhu, A., Kripalani, R. H., Preethi, B. & Pandithurai, G. Potential role of the February–March southern annular mode on the Indian summer monsoon rainfall: a new perspective. Clim. Dyn. 47, 1161–1179 (2016).

Huang, P.-W., Lin, Y.-F. & Wu, C.-R. Impact of the Southern Annular Mode on extreme changes in Indian rainfall during the early 1990s. Sci. Rep. 11, 2798 (2021).

Nan, S., Li, J., Yuan, X. & Zhao, P. Boreal spring Southern Hemisphere annual mode, Indian Ocean SST and East Asian summer monsoon. J. Geophys. Res. 114, D02103 (2009).

Nan, S. & Li, J. The relationship between the summer precipitation in the Yangtze River valley and the boreal spring Southern Hemisphere annular mode. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL018381 (2003).

Xue, F., Wang, H. & He, J. Interannual variability of Mascarene high and Australian high and their influences on summer rainfall over East Asia. Chin. Sci. Bull. 48, 492–497 (2003).

Wu, Z. W., Dou, J. & Lin, H. Potential influence of the November–December Southern Hemisphere annular mode on the East Asian winter precipitation: a new mechanism. Clim. Dyn. 44, 1215–1226 (2015).

Zheng, F., Li, J. P., Wang, L., Xie, F. & Li, X. Cross-seasonal influence of the December–February Southern Hemisphere annular mode on March–May meridional circulation and precipitation. J. Clim. 28, 6859–6881 (2015).

Hoskins, B. J. & Karoly, D. J. The steady linear response of a spherical atmosphere to thermal and orographic forcing. J. Atmos. Sci. 38, 1179–1196 (1981).

Webster, P. J. & Holton, J. R. Cross-equatorial response to middle-latitude forcing in a zonally varying basic state. J. Atmos. Sci. 39, 722–733 (1982).

Hoskins, B. J. & Ambrizzi, T. Rossby wave propagation on a realistic longitudinally varying flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 50, 1661–1671 (1993).

Li, Y., Feng, J., Li, J. & Hu, A. Equatorial windows and barriers for stationary Rossby wave propagation. J. Clim. 32, 6117–6135 (2019).

Braga, H. A., Ambrizzi, T. & Hall, N. M. J. South Atlantic convergence zone as Rossby wave source. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 155, 4231–4247 (2024).

Yang, S. & Li, T. Intraseasonal variability of air temperature over the mid-high latitude Eurasia in boreal winter. Clim. Dyn. 47, 2155–2175 (2016).

North, G. R., Bell, T. L., Cahalan, R. F. & Moeng, F. J. Sampling errors in the estimation of empirical orthogonal functions. Mon. Weather Rev. 110, 699–706 (1982).

Mo, K. C. Relationship between low-frequency variability in the Southern Hemisphere and sea surface temperature anomalies. J. Clim. 13, 3599–3610 (2000).

Bretherton, C. S., Widmann, M., Dymnikov, V. P., Wallace, J. M. & Bladé, I. The effective number of spatial degrees of freedom of a time-varying field. J. Clim. 12, 1990–2009 (1999).

Mousavizadeh, M. et al. Causality in the winter interaction between extratropical storm tracks, atmospheric circulation, and Arctic sea ice loss. J. Geophys. Res. 130, e2024JD042128 (2025).

Clark, J. P. & Lee, S. The role of the tropically excited Arctic warming mechanism on the warm Arctic cold continent surface air temperature trend pattern. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 8490–8499 (2019).

Yu, B. & Lin, H. Modification of the wintertime Pacific-North American pattern related North American climate anomalies by the Asian-Bering-North American teleconnection. Clim. Dyn. 53, 313–328 (2019).

Park, M. & Lee, S. The role of planetary-scale eddies on the recent isentropic slope trend during boreal winter. J. Atmos. Sci. 78, 2879–2894 (2021).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Lee, S. et al. Revisiting the cause of the 1989-2009 Arctic surface warming using the surface energy budget: downward infrared radiation dominates the surface fluxes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 10,654–10,661 (2017).

Luo, B., Luo, D., Wu, L., Zhong, L. & Simmonds, I. Atmospheric circulation patterns which promote winter Arctic sea ice decline. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 054017 (2017).

Sato, K. & Simmonds, I. Antarctic skin temperature warming related to enhanced downward longwave radiation associated with increased atmospheric advection of moisture and temperature. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 064059 (2021).

Henderson, S. A., Maloney, E. D. & Son, S.-W. Madden-Julian Oscillation Pacific teleconnections: the impact of the basic state and MJO representation in general circulation models. J. Clim. 30, 4567–4587 (2017).

Soulard, N., Lin, H., Derome, J. & Yu, B. Tropical forcing of the circumglobal teleconnection pattern in boreal winter. Clim. Dyn. 57, 865–877 (2021).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 608–627 (2001).

Shen, X., Wang, L., Scaife, A. A. & Hardiman, S. C. Intraseasonal linkages of winter surface air temperature between Eurasia and North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL113301 (2025).

Liebmann, B. & Hartmann, D. L. An observational study of tropical-midlatitude interaction on intraseasonal time scales during winter. J. Atmos. Sci. 41, 3333–3350 (1984).

Kiladis, G. N. & Weickmann, K. M. Circulation anomalies associated with tropical convection during northern winter. Mon. Weather Rev. 120, 1900–1923 (1992).

Lau, N.-C. Variability of the observed midlatitude storm tracks in relation to low-frequency changes in the circulation pattern. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 2718–2743 (1988).

Simmons, A. J., Wallace, J. M. & Branstator, G. W. Barotropic wave propagation and instability, and atmospheric teleconnection patterns. J. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1363–1392 (1983).

Lin, H., Brunet, G. & Mo, R. Impact of the Madden-Julian Oscillation on wintertime precipitation in Canada. Mon. Weather Rev. 138, 3822–3839 (2010).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Liebmann, B. & Smith, C. A. Description of a complete (interpolated) outgoing longwave radiation dataset. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 77, 1275–1277 (1996).

Lin, H., Brunet, G. & Derome, J. Intraseasonal variability in a dry atmospheric model. J. Atmos. Sci. 64, 2422–2441 (2007).

Hall, N. M. J. & Derome, J. Transience, nonlinearity and eddy feed-back in the remote response to El Nino. J. Atmos. Sci. 57, 3992–4007 (2000).

Sardeshmukh, P. D. & Hoskins, B. J. The generation of global rotational flow by steady idealized tropical divergence. J. Atmos. Sci. 45, 1228–1251 (1988).

Hoskins, B. J. & Simmons, A. J. A multi-layer spectral model and the semi-implicit method. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 101, 637–655 (1975).

Hall, N. M. J. A simple GCM based on dry dynamics and constant forcing. J. Atmos. Sci. 57, 1557–1572 (2000).

Hall, N. M. J., Derome, J. & Lin, H. The extratropical signal generated by a midlatitude SST anomaly Part I: sensitivity at equilibrium. J. Clim. 14, 2035–2052 (2001).

Sardeshmukh, P. D. & Hoskins, B. J. Spatial smoothing on the sphere. Mon. Weather Rev. 112, 2524–2529 (1984).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. carried out the analysis. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, H., Yu, B. & Hall, N.M.J. Link of the Warm Arctic Cold Eurasian pattern to the Southern Annular Mode variability. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 225 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01102-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01102-z