Abstract

Most previous studies on the climatic effects of Antarctic ozone have focused primarily on the Southern Hemisphere. This study suggests that September-October Antarctic ozone anomalies account for approximately 12% of the interannual variability in East Asian summer precipitation. The precipitation anomalies linked to the Antarctic ozone index are characterized by increased rainfall between the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers in central East China and decreased rainfall over Southeastern China. Our analysis reveals that positive Antarctic ozone anomalies during September–October are associated with a negative phase of the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) during the subsequent boreal winter. The resulting SAM-related circulation anomalies exert a significant influence on sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs) in the southwestern Indian Ocean, particularly near the Madagascar region. Owing to the ocean’s thermal inertia, these SSTAs persist into the subsequent boreal spring, altering the meridional circulation and leading to anomalous subsidence near 15°N, which in turn results in elevated skin temperature anomalies (SKTAs) over the Indochina Peninsula. Numerical experiments conducted with the Community Atmospheric Model version 5 further confirm the role of southwestern Indian Ocean SSTAs in driving this response. Land memory and positive land–atmosphere feedbacks sustain these SKTAs into boreal summer. Consequently, the SKTAs-induced heating over the Indochina Peninsula enhances the southwesterly monsoon and strengthens precipitation over central East China, as demonstrated by linear baroclinic model experiments. Furthermore, the Specified-Chemistry version of the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model is used to verify the remote influence of Antarctic ozone anomalies on East Asian summer precipitation. Our findings provide an additional predictor for summer precipitation over East Asia and deepen our understanding of the interhemispheric impacts of Antarctic ozone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Starting from the mid-1980s, the area of Antarctic stratospheric ozone depletion during boreal autumn has consistently surpassed 10 million km², posing a direct threat to the climate and environment of the Southern Hemisphere (SH)1. Antarctic ozone depletion influences SH climate primarily through its robust linkage to the positive phase of the Southern Annular Mode (SAM)2,3,4,5,6, the dominant mode of extratropical variability in the SH7,8,9,10.

Previous research has shown that SAM not only significantly impacts the climate of the SH but also exerts influence on the East Asian climate. Interannual variations in SAM modulate sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs) via dynamical and thermodynamical processes, triggering meridional circulation anomalies that ultimately influence precipitation patterns in East Asia11,12,13. Zhu and Wu (2024) highlighted that the rise in Antarctic ozone levels during September and October has an impact on the SAM-associated tripolar SSTAs in the Southern Indian Ocean, with this SSTAs pattern persisting into the boreal winter14. The interaction weakens the zonal circulation, leading to positive anomalies of winter outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) over the Southern Maritime Continent, further influencing atmospheric circulation and precipitation patterns in East Asia during boreal winter14. Although substantial progress has been made in understanding the influence of Antarctic ozone depletion on East Asian winter precipitation, what happened after the winter was overlooked. Does Antarctic ozone depletion also affect East Asian summer precipitation (EASP)?

Notably, the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM) is a critical driver of regional hydrological processes, accounting for approximately 40%–50% of the total yearly precipitation across Southern China and 60%–70% in the northern regions of China15. Variations in EASM-driven summer precipitation reshape hydrological patterns and heighten the risk of extreme weather events such as floods and droughts, with significant consequences for food security, infrastructure, and societal resilience. Therefore, achieving precise forecasting of EASP is essential.

The interannual variability of the EASP is shaped by multiple factors, with the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) being widely acknowledged as the primary factor. During El Niño developing summer, drought anomalies are observed over central North China. During the decaying phase, El Niño impacts East Asian subtropical frontal precipitation by driving intense interactions between the anomalous western Pacific anticyclone (WPAC) and the dipolar SSTAs in the Indo-Pacific warm pool16,17. When El Niño rapidly transitions to La Niña, East Asian precipitation is influenced by the re-emergence of the WPAC, which is driven by the abrupt cooling in the Eastern Pacific17. Wu et al. (2009) found that the East Asian subtropical front and EASM can be affected by spring NAO18. On the other hand, Xie et al. (2009) emphasized how the Indian Ocean SSTAs influence fluctuations in the western Pacific subtropical high (WPSH) and the EASM19. Additionally, Zha and Wu (2023) identified a key snow cover region in the southwestern Tibetan Plateau (76°–83°E, 28°–35°N), where an increase in winter snow cover significantly enhances rainfall over the Yangtze River basin in the subsequent summer20.

Despite the advances in climate models that incorporate key drivers such as ENSO, the simulation of East Asian precipitation and the associated atmospheric circulation anomalies, particularly during summer, remains challenging and exhibits notable deficiencies21,22. The difficulty in accurately representing the year-to-year variability of EASP suggests that additional factors influencing regional climate variability may be underrepresented or insufficiently understood in current models23. Previous studies have demonstrated the influence of stratospheric ozone on regional precipitation patterns. Kang et al. (2011) highlighted that the poleward shift of the mid-latitude jet stream, induced by the Antarctic ozone hole, contributes to increased precipitation in the subtropical regions of the Southern Hemisphere10. Xie et al. (2018) further revealed that anomalous Arctic Stratospheric Ozone during February–March exerts a significant impact on precipitation over the Loess Plateau and the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River in April–May24. Xia et al. (2023) reported that stratospheric ozone depletion over the southern slope of the Tibetan Plateau enhances local deep convection and precipitation25. More recently, Xie et al. (2024) suggested that the boreal summer precipitation anomalies in West Siberia between 1993 and 2010 were closely associated with elevated ozone concentrations in the upper troposphere–lower stratosphere (UTLS) during that period26.

Given the challenges associated with accurately predicting summer rainfall and the potential influence of ozone on precipitation, this study aims to explore the impact of Antarctic ozone anomalies in September-October on East Asian precipitation during the following summer. Understanding this connection could offer fresh perspectives on the drivers of East Asian climate variability and enhance the precision of summer rainfall forecasts. In this study, a notable relationship between Antarctic ozone from September to October and the subsequent EASP is identified. The possible mechanisms are also examined.

The paper provides observation evidence for the relationship between the September-October total column ozone (TCO) over Antarctica and the EASP. Subsequently, we elucidate the mechanisms by which Antarctic ozone anomalies influence boreal spring skin temperature anomalies (SKTAs) over the Indochina Peninsula through SSTAs of the Southern Indian Ocean. The subsequent section illustrates the physical mechanisms through which boreal spring SKTAs over the Indochina Peninsula persists into boreal summer and examines its influence on atmospheric circulation patterns across East Asia. In the final section, results from model experiments are provided to evaluate the EASP anomalies induced by Antarctic ozone anomalies.

Results

The linkage between the Antarctic ozone and the EASP

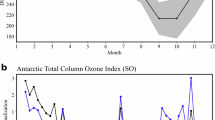

To explore how the year-to-year fluctuations in Antarctic ozone affect the climate, we adopt the approach of Zhu and Wu (2024) by defining the Antarctic Total Column Ozone Index (ATCOI). This index is calculated as the detrended average of TCO across the Antarctic region, spanning 180°W to 180°E and 60° to 90°S, during September and October (SO). In Fig. 1A, the spatial associations between EASP anomalies and the ATCOI are depicted through a regression analysis. The result reveals a north-south dipole pattern of precipitation anomalies in East Asia associated with the increasing ATCOI. Specifically, positive anomalies occur in a belt between the Yangtze River and Yellow River extending from the eastern Tibetan Plateau to Southern Japan. Meanwhile, negative precipitation anomalies extend over Southeastern China. According to Fig. 1B, the ATCOI explains approximately 12% of the variability in central-eastern China and Southern Japan and around 10% of the variability observed in Southern China. Over the eastern flank of the Tibetan Plateau, the maximum explained variance exceeds 20%. To determine if the connection between the ATCOI and EASP is impacted by ENSO or Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), the partial regression approach is conducted to separate the influences of these climate drivers during boreal summer (Fig. 1C, D). After excluding the ENSO and IOD signals, the pattern of precipitation anomalies over East Asia shows minimal alteration and retains statistical significance. This indicates that the association between ATCOI and EASP is independent of ENSO and IOD.

A Summer precipitation anomalies regressed onto ATCOI (shadings; mm/day). B The contribution of ATCOI to the variance in summer precipitation (shadings; %). C, D Same as (A) but showing partial regression after removing the impact of summer ENSO and IOD signals, respectively (shadings; mm/day). E 1000 hPa–300 hPa vertically integrated water vapor flux divergence anomalies (shadings; 10-5kg/m2s) and 1000 hPa–300 hPa vertically integrated water vapor flux anomalies (green vectors; kg/ms), F 500 hPa omega anomalies (shadings; 10-3 Pa/s), G 500 hPa geopotential height (shadings; gpm) and wind anomalies (green vectors; m/s) and (H) 850 hPa geopotential height (shadings; gpm) and wind anomalies (green vectors; m/s) during summer regressed against the SO ATCOI. The blue dashed 5880-gpm contour in (G) represents the sum of the climatological mean and the geopotential height anomalies, while the solid 5880-gpm contour indicates the climatological mean alone. Black stippling/slashes and green arrows represent significance above the 90% confidence level.

To further elucidate the observed distribution of the precipitation anomalies, Fig. 1E–H illustrate the anomalies of vertically integrated water vapor flux divergence (1000 hPa–300 hPa), omega at 500 hPa, wind and geopotential height at 500 and 800 hPa, respectively, all regressed onto the ATCOI. In Fig. 1E, the blue shadings denote areas of water vapor flux convergence anomalies, while the red shadings indicate regions of divergence anomalies. Notably, significant convergence anomalies of water vapor flux are observed over the Yangtze Huaihe River Basin, and divergence anomalies are evident over Southern China, corresponding well with the observed precipitation pattern in Fig. 1A. Figure 1F presents the regression of 500 hPa omega anomalies against ATCOI. The results reveal a dipole pattern, with positive anomalies emerging across Southern China, and negative anomalies stretching from the Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin to Southern Japan. At both 500 hPa and 850 hPa, the positive geopotential height anomaly center located over Southern China suppresses local precipitation (Fig. 1G, H), aligning well with the observed negative precipitation anomalies. Additionally, the 5880-gpm contour derived from the sum of the climatological mean and geopotential height anomalies linked to ATCOI (blue dashed line in Fig. 1G) is located to the west of the climatological 5880-gpm contour (blue solid line in Fig. 1G), indicating a westward extension of the WPSH. This finding suggests that Antarctic ozone variability may modulate the summer WPSH by promoting a westward shift in its position. Concurrently, southwesterly winds associated with the anticyclone facilitate the flow of abundant moisture to the region between Yangtze and Yellow Rivers in central East China, consequently promoting precipitation formation.

Ozone impacts SKTAs over the Indochina Peninsula through the Southwest Indian Ocean SSTAs

How does September-October Antarctic ozone influence EASP nearly half a year later? Considering the ability of SSTAs to preserve atmospheric signals for prolonged durations, it is hypothesized that Antarctic ozone variability may initially induce SAM-related SSTAs, which persist and subsequently modulate EASP through prolonged ocean-atmosphere interactions.

The potential underlying physical mechanisms governing the influence of Antarctic ozone on the SAM have been extensively investigated and are generally attributed to several key processes, including the modulation of wave-driven heat fluxes in the lower troposphere2, and both radiative and dynamical forcing of the near-surface meridional temperature gradient2,27, etc. It is now well recognized that increases in Antarctic ozone are associated with the negative phase of SAM. In the present study, we identify significant negative correlations between the ATCOI and the SAM Index (SAMI) during September-October-November (SON) and December-January-February (DJF), with correlation coefficients of −0.38 and −0.34, respectively, both exceeding the 95% confidence level.

The lead–lag correlations map between the SO ATCOI and the polar ozone mixing ratio, temperature, and 10-m wind time series from July (0) to May (1) are depicted in Fig. S1. Here ‘0’ represents the coinstantaneous year and ‘1’ denotes the following year. The results elucidate the radiative forcing effect of the Antarctic ozone, wherein increasing stratospheric ozone allows more downwelling longwave radiation through the polar tropopause, resulting in the warming of the polar troposphere (Fig. S1B). Consequently, this induces a reduction in the north-south temperature gradient near 60°S and a weakening of the jet stream (Fig. S1C), corresponding to the anomalous easterly wind near 60°S. The radiative impacts of ozone anomalies exhibit a lagged response, as stratospheric temperature changes gradually modify the meridional temperature gradient and zonal wind structure in the troposphere28. This time-lagged downward coupling of ozone contributes to the variability of SAM during DJF.

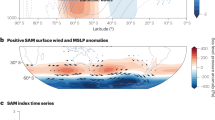

To examine the influence of ATCOI-related DJF SAM variability on SSTAs, Fig. 2B–D present the regression of SSTAs from DJF through the following boreal summer onto the inverse DJF SAMI. The results reveal a meridional tripolar SSTAs pattern over the Southern Indian Ocean, which persists from boreal winter into the following boreal spring, before gradually weakening in boreal summer. Zhu and Wu (2024) provided a detailed explanation of how SAMI during SON influences this SSTAs pattern in boreal winter, suggesting that ozone depletion drives a SAM-related SSTAs through alterations in Ekman transport, radiative fluxes, and turbulent heat fluxes during boreal autumn (Fig. 4 in Zhu and Wu, 2024)14. Specifically, anomalous warming near 60°S and cooling around 40°S are primarily driven by SAM-induced Ekman heat flux anomalies and radiative heat fluxes, while the positive SSTA to the east of Madagascar is primarily driven by wind-evaporation feedback and radiative heat fluxes. In this study, sea level pressure and 10-m wind anomalies regressed on inverse SAMI during DJF is illustrated in Fig. 2A. During the negative phase of the DJF SAM, a meridional dipole in sea level pressure (SLP) develops over the Southern Indian Ocean, with anomalous low SLP centered near 40°S and high SLP south of 60°S. In response, surface winds weaken over the high latitudes and the region around Madagascar (green vectors in Fig. 2A), as evidenced by the departure from climatological wind patterns (black vectors in Fig. 2A). This reduction in wind speed suppresses latent heat fluxes from the ocean surface, thereby enhancing local sea surface warming through the wind–evaporation–SST (WES) feedback. The SAM-induced SSTAs surrounding Madagascar persist from DJF through March-April-May (MAM), primarily due to the ocean’s thermal inertia. To quantify this signal, we define the Southwest Indian Ocean (SWIO) index as the area-averaged SSTAs within the red region bounded by 30°–10°S and 35°–70°E (red rectangle in Fig. 2) during MAM. The MAM SWIO index shows a statistically significant correlation with the inverse DJF SAMI, with correlation coefficients of 0.38, exceeding 95% confidence level.

Regression of (A) 10 m wind anomalies (green vectors; m/s) and SLP anomalies (shadings; hPa) during DJF, SSTAs during (B) DJF, (C) MAM and (D) JJA on the inverse SAMI during DJF (shadings; K). Black stippling represents significance above the 90% confidence level. SWIO index is defined based on the red rectangular region.

This prompts an inquiry: how does the boreal spring SWIO SSTAs impact the following EASP? Liu et al. (2015) indicated that the positive phase of SAM during boreal autumn significantly influences the dipole Southern Ocean SSTAs during boreal winter13. This modification in SSTAs subsequently affects the vertical motion within the meridional circulation of the SH, leading to changes in precipitation patterns across the Northern Hemisphere. To investigate the related meridional circulation with SWIO SSTAs, we examine the regression of meridional circulation onto the SWIO index, averaged over 60°–120°E (Fig. 3A). The results reveal pronounced ascending motion between 10°S and the equator, accompanied by enhanced subsidence between the equator and 25°N, with the maximum anomalous downward motion centered around 12°N. Meanwhile, SWIO index during MAM are found to be closely associated with skin temperature anomalies (SKTAs) over both the Indian subcontinent and the Indochina Peninsula (Fig. 3B), with particularly strong signals observed between 10° and 20°N. The enhanced subsidence may contribute to the development of positive SKTAs observed over both regions.

A Vertical velocity anomalies (shadings; 10-3 Pa/s) and meridional circulation anomalies (grey and purple arrows) regressed against the SWIO index, averaged over 60°–120°E. The SKTAs during (B) MAM and (C) JJA regressed against boreal spring SWIO index (shadings; K). Black stippling represents significance above the 90% confidence level. IPSKTI is defined based on the red rectangular region. Black stippling and purple arrows represent significance above the 90% confidence level.

Given that the observed air–sea coupling over the SWIO region may reflect both the atmospheric response to SST forcing and the oceanic response to atmospheric variability, we further employ the Community Atmospheric Model version 5 (CAM5) to conduct numerical experiments aimed at isolating the atmospheric response to SWIO SSTAs warming. The ‘SST_Clim’ simulation represents the control experiment, which is initialized with historical sea surface temperature (SST) conditions. To simulate the impact of SWIO SSTAs, the SWIO SSTAs associated with inverse SAMI during boreal spring are imposed onto the control experiment. This configuration is implemented as a sensitivity experiment and referred to as the ‘SST_ SWIO’ experiment. Both ‘SST_Clim’ and ‘SST_SWIO’ experiments run for 30 years. The influence of SWIO SSTAs on meridional circulation anomalies and temperature anomalies are evaluated by analyzing the last 10-year differences of the two simulations.

Figure 4A depicts the meridional circulation anomalies induced by spring SWIO SSTAs, averaged over 60°–120°E, whereas Fig. 4B shows the corresponding surface temperature anomalies during boreal spring. The simulated meridional circulation response (Fig. 4A) closely resembles the observed pattern (Fig. 3A), with good agreement in the anomalous ascending motion near the equator and pronounced subsidence between 10° and 20°N. This circulation response further contributes to the development of positive surface temperature anomalies over the Indian subcontinent and the Indochina Peninsula (Fig. 4B). Although the simulated temperature anomalies are weaker in magnitude compared to observations (Fig. 3B), the significant warming centers remain confined to 10°–20°N, consistent with the core warming regions identified in the observations. Overall, the experiments successfully capture the dominant patterns observed, confirming that SWIO SSTAs can exert a substantial influence on subsidence in the 10°-20°N region and further impact the surface temperature anomalies over the Indian subcontinent and the Indochina Peninsula.

Differences in (A) vertical velocity (shadings; 10–3 Pa/s) and meridional circulation (purple arrows) averaged over 60°–120°E and (B) surface temperature (shadings; K) between the SST_SWIO and SST_Clim experiments. Black stippling and purple arrows represent significance above the 90% confidence level.

As shown in Fig. 3B, C, the regression of SKTAs onto the SWIO index exhibits distinct patterns during boreal spring and boreal summer. Over the Indochina Peninsula, SKTAs display a persistence from boreal spring through boreal summer. In contrast, the Indian subcontinent exhibits a marked seasonal evolution in the spatial distribution of temperature anomalies. During boreal spring, significant anomalies are mainly observed in Southern India, while central and northern regions show weak or non-significant responses. This spatial pattern likely reflects the pre-monsoon state when deep convection and oceanic influence remain concentrated near lower latitudes. As the Indian monsoon develops and the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) shifts northward in June, temperature anomalies migrate toward central and northern India. However, the progression of the Indian monsoon is slower and more spatially heterogeneous due to the dynamical and thermal influence of the Tibetan Plateau to the north. The onset of sustained precipitation, enhanced cloud cover, and increased evaporative cooling introduce strong local feedbacks that substantially modify the surface thermal field. These processes result in greater temporal variability in SKTAs over India and reduce its persistence across seasons. Although the summer monsoon also arrives over the Indochina Peninsula, its climatological onset occurs earlier—around May—and rapidly progresses northward across the region east of the Bay of Bengal29. As a result, the associated increase in precipitation and cloud cover exerts only a modest impact on surface thermal conditions, allowing the SKTAs signal established in spring to persist into summer. Since our objective is to identify robust and consistent precursors of East Asian summer rainfall, the Indian subcontinent is less suitable for this purpose. We therefore focus our subsequent analysis on the Indochina Peninsula, where SKTAs signals are more persistent.

The impact of winter SKTAs on EASP

So, how do these SKTAs persist from winter into the following summer? Local positive land-atmospheric feedback mechanisms can sustain surface temperature anomalies into the subsequent season by amplifying the thermal response30,31,32. To explore whether such feedback operates during boreal spring, MAM SKTA, low cloud cover (LCC), boundary layer height (BLH), and surface sensible heat flux (ISHF) anomalies are regressed onto the MAM SWIO index (Fig. 5). In response to the strengthening of SWIO SSTAs-induced SKTAs over Indochina Peninsula (Fig. 5A), positive BLH anomalies are observed (Fig. 5C), accompanied by negative LCC anomalies (Fig. 5B) and ISHF anomalies (Fig. 5D). The reduction in LCC allows for increased shortwave radiation and enhanced surface sensible heat flux, which causes the atmospheric boundary layer to deepen, thereby further inhibiting LCC and increasing the local SKTAs. This sequence of events reinforces the SKTAs through a local positive land-atmosphere feedback mechanism.

To assess whether the SKTAs induced in boreal spring can persist into boreal summer, we next consider the role of land memory. Such memory effects—arising from processes like snow cover anomalies, soil moisture variability, and changes in surface albedo33,34,35,36—can allow boreal spring thermal anomalies to carry over into subsequent summer. To explore the contribution of land memory effect on the persistence of SKTAs from spring into summer, we compare the persistent component of SKTAs during MAM with June-July-August (JJA) SKTAs regressed against the MAM SWIO index. Following Pan (2005)37, the persistent component of SKTAs during JJA can be expressed as follows:

Here, Cov and Var refer to covariance and variance, respectively. Figure 6A presents the persistence component of SKTAs during JJA, characterized by statistically significant anomalies across large portions of the Indochina Peninsula. In comparison, Fig. 6B shows the total SKTAs during JJA regressed onto the MAM SWIO index, which exhibits broader and stronger spatial significance. To further quantify the contribution of the land memory effect to boreal summer SKTAs, we calculate the squared pattern correlation between Fig. 6A, B. This metric represents the proportion of the summer SKTAs that can be explained by persistence from boreal spring. The result suggests that approximately 25% of the SKTA over the Indochina Peninsula during summer can be attributed to land memory effects from the preceding spring. This indicates that both the land memory effect and spring local feedbacks play important roles in sustaining SKTAs into the summer season.

The broader and more pronounced SKTAs during boreal summer (Fig. 6B), compared to the persistence component shown in Fig. 6A, indicate that processes beyond land memory are contributing to the maintenance of thermal anomalies. To further investigate this, we assess whether local land–atmosphere feedbacks remain active during boreal summer and potentially reinforce SKTAs. As shown in Table S1, which summarizes the correlation coefficients among SKTI, BLH, TCC, and ISHF over the Indochina Peninsula (10°–25°N, 90°–120°E) during JJA, the inter-variable relationships remain highly significant throughout the boreal summer. These strong correlations are consistent with a continued land-atmosphere positive feedback process, whereby reduced cloud cover enhances surface heating and deepens the boundary layer, further sustaining the warm surface conditions. Overall, these results suggest that land memory and local land–atmosphere interactions work together to sustain and amplify SKTAs from boreal spring into boreal summer over the Indochina Peninsula. The findings are consistent with previous studies, which highlight the strong persistence of surface temperature anomalies over the Indochina Peninsula38,39.

So far, we have elucidated the mechanisms through which Antarctic ozone during September-October affects SKTAs over the Indochina Peninsula during summer. However, an important question remains: can these SKTAs exert a remote influence on the East Asian summer circulation?

To quantitatively assess the influence of SKTAs over the Indochina Peninsula, we define the SKTAs index over the Indochina Peninsula (IPSKTI) as the average SKTAs within the red boxed areas (10°-25°N, 90°-120°E) shown in Fig. 3. Figure S2A illustrates the regression of EASP anomalies against boreal summer IPSKTI, revealing a dipole pattern characterized by significant positive anomalies extending from the Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin to Southern Japan, alongside negative anomalies over Southern China. This pattern is consistent with the ATCOI-related precipitation anomalies (Fig. 1A). Concurrently, at 500 hPa and 850 hPa, wind anomalies reveal an anti-cyclonic circulation over the northwestern Pacific to the South China Sea, coupled with enhanced southwesterly winds over the Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin (Fig. S2B, C), which facilitate local increased precipitation anomalies.

To verify the influence of SKTAs over Indochina Peninsula on the atmospheric circulation in East Asia, we employ the linear baroclinic model (LBM) and design a numerical experiment. The location of the thermal forcing encompasses the red box in Fig. 3, centered at 100°E, 15°N, and forming an elliptical shape with radii of 10° and 5° along the latitude and longitude axes, respectively (Fig. S3A). To simulate the diabatic heating effect caused by the SKTA over the Indochina Peninsula region, an idealized heating profile is implemented, reaching a peak at 1 K day–1 around 550 hPa (Fig. S3B). The experiment is conducted using the summer climatological mean state, and the LBM is run for a duration of 30 days, with the results averaged over the final 10 days to represent the stabilized response for subsequent analysis.

Figure S3C presents the simulated response of wind anomalies at 850 hPa and omega anomalies at 500 hPa to the imposed heating over the Indochina Peninsula. The results show an anticyclonic anomaly centered over South China Sea, accompanied by southwesterly wind anomalies over the Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin, which enhances moisture transport into the region. Concurrently, negative omega anomalies at 500 hPa are simulated over the Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin, indicative of increased local precipitation, aligning well with observed result. However, compared to observations, the LBM does not simulate negative omega anomalies over Southern Japan, with the center of negative anomalies shifting northwestward. Overall, the result confirms that the diabatic heating over the Indochina Peninsula can trigger positive precipitation anomalies between Yangtze and Yellow River in central East China.

Simulated precipitation response to ozone anomalies

To assess the influence of September-October Antarctic ozone anomalies on the East Asian summer climate, the Specified-Chemistry version of the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model (SC-WACCM) is utilized to perform two experiments with varied ozone prescriptions. The ‘less_ozone’ simulation serves as the control experiment, where monthly average ozone mixing ratios from the year 2000 are prescribed. The ‘more_ozone’ simulation refers to the sensitivity experiment, where we substitute the ozone concentrations for September-October with the annual mean values across all atmospheric levels over Antarctica to model a fully restored ozone hole. Figure S4 shows the difference in the initial vertical distribution of ozone during September–October between the control and sensitivity experiments in the SC-WACCM simulations. Both the ‘less_ozone’ and ‘more_ozone’ experiments are conducted over 30 years. The climatic influence of Antarctic ozone anomalies is assessed by comparing the differences between the two experiments, averaged over the final 15 years.

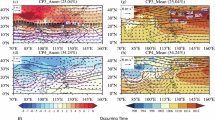

The model-derived impacts of Antarctic ozone variability during boreal summer over East Asia are illustrated in Fig. 7. In Fig. 7A, significant positive precipitation anomalies are induced between the Yangtze and Yellow River in central East China by positive Antarctic ozone anomalies during September-October, aligning well with the observational findings shown in Fig. 1A. Figure 7B depicts the omega anomalies at 500 hPa over East Asia during summer induced by Antarctic ozone anomalies. The analysis reveals negative omega anomalies over the Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin region, indicative of local enhanced precipitation, which is consistent with the results from the observation data and LBM result. Figure 7C, D, and E illustrate the geopotential height and wind anomalies at different atmospheric levels. At 200 hPa, high-pressure anomalies extend from Eastern China to Southern Japan (Fig. 7C). Meanwhile, at 500 hPa and 850 hPa, positive geopotential height anomalies emerge over Southern China, accompanied by an anticyclonic circulation pattern that facilitates the advection of moisture into the Yangtze-Huaihe River Basin (Fig. 7D, E), contributing to the observed increase in precipitation. Overall, the results derived from SC-WACCM demonstrate that the increase of Antarctic ozone during September-October can intensify the precipitation anomalies over East Asia during boreal summer.

Differences in JJA (A) precipitation (shadings; mm/day), (B) 500 hPa omega (shadings; Pa/s), along with geopotential height (shading; gpm) and wind (vectors; m/s) at (C) 200 hPa, (D) 500 hPa, and (E) 850 hPa derived from two numerical experiments. Black stippling and red arrows represent significance above the 90% confidence level.

Discussion

The primary physical mechanisms elucidated in this study involve both ocean–atmosphere and land–atmosphere bridging processes, as illustrated in Fig. S5. First, the increase in Antarctic ozone during September–October contributes to a negative phase of the SAM in the subsequent boreal winter. This negative SAM phase influences the development of a tripolar SSTAs pattern in the Southern Indian Ocean. The warm pole of this tripolar structure, located over the southwestern Indian Ocean, persists from boreal winter into the following spring due to ocean thermal inertia. Subsequently, the SWIO SSTAs warming triggers an anomalous meridional circulation, characterized by enhanced ascending motion near the equator and pronounced subsidence between 10° and 20°N. The resulting subsidence induces positive SKTAs over the Indochina Peninsula, which persist into boreal summer, sustained by a combination of land surface memory and positive land–atmosphere feedback processes. These persistent SKTAs further lead to atmospheric circulation anomalies over Southeastern China. An associated anticyclonic circulation develops, strengthening moisture transport into the region between the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers in central East China and resulting in positive precipitation anomalies.

While this study elucidates one physical mechanism through which Antarctic ozone variability in September–October modulates East Asian summer precipitation, it is important to acknowledge that other pathways may also play a role. For instance, we find that Antarctic ozone anomalies during September–October are also associated with a Pacific SST pattern resembling the Pacific Meridional Mode (PMM), which persists from boreal winter into spring. This suggests the potential for alternative teleconnection mechanisms that warrant further investigation in future studies. On the other hand, while this study researches on the interannual variability of Antarctic ozone over the period 1979–2023, the ozone index also exhibits a pronounced shift in its long-term trend around the early 2000s. This raises the possibility that the interannual relationship between Antarctic ozone and East Asian summer precipitation may be modulated by changes in the background climate state. Future research could investigate how this interdecadal variability modulates the interannual relationship between Antarctic ozone and East Asian summer precipitation.

The most frequent precipitation in East Asia happens in the boreal summer season, profoundly affecting agricultural production and the management of water resources. However, accurate forecasting of EASP remains a considerable challenge to date. In addition to predictors such as ENSO and NAO, our findings indicate that Antarctic ozone during September-October may act as an extra factor in forecasting the following summer rainfall in East Asia. Nevertheless, constructing a forecasting system that integrates Antarctic ozone information to refine summer precipitation predictions for East Asia remains a substantial challenge. As Antarctic ozone levels gradually recover, understanding their potential influence on the EASP becomes increasingly critical for advancing climate predictions. These unresolved issues remain to be explored in future research.

Methods

Reanalysis datasets

The data utilized in this study consist of: (1) monthly TCO, sea level pressure, omega, skin temperature, specific humidity, divergence, geopotential height, vertical and horizontal wind components, TCC, ISHF, BLH gridded with 0.25° × 0.25° grid, provided by the ECMWF Reanalysis v5 (ERA5) reanalysis from 1979 to 202340; (2) monthly global 2.5° × 2.5° precipitation data taken from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project; (3) SST data available from monthly global 2° × 2° Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature (ERSST) version 5 from 1979 to 202341; (4) the SAM index is defined following Marshall (2003) 42.

Statistical analysis

Statistical methods, including correlation analysis and linear regression, are used to analyze the data. To ensure robustness and reliability of the conclusion, a two-tailed Student’s t-test is applied to determine statistical significance. The seasons referred to in this paper are all boreal seasons.

Experimental design

To evaluate the influence of SWIO SSTAs on atmospheric circulation and vertical motion, numerical experiments are conducted with CAM5. As the atmospheric module of the Community Earth System Model (CESM), CAM5 operates in conjunction with the Community Land Model (CLM). In this study, the model is configured with a 1° × 1° horizontal resolution and 17 vertical layers. By prescribing SST forcing, this model allows for precise control over initial SST conditions, facilitating the analysis of corresponding climate responses43.

In this study, numerical experiments with the LBM are performed to explore the impact of diabatic heating anomalies over the IIP on atmospheric patterns across East Asia. The LBM provides valuable insights into complex feedback processes by simplifying the nonlinear dynamics of the atmosphere44,45. Additionally, the LBM has been widely employed in published studies to examine how the atmosphere responds linearly to variations in diabatic heating46,47,48. We apply the dry version LBM, which has a T42 horizontal resolution and 20 vertical sigma levels.

To validate the influence of the Antarctic ozone variability during September-October on EASP, this study employs the SC-WACCM model. The model has a grid spacing of 1.9° in longitude and 2° in latitude and includes 66 vertical layers, reaching up to 5.96 × 10−6 hPa. It is integrated with ocean, land, and sea ice components, enabling a more holistic and interactive simulation of the global climate system. Furthermore, the model is configured to run with prescribed ozone mixing ratios14,49,50, providing precise control over the initial ozone conditions. Given its established use in prior research on the effect of ozone depletion across various regions, SC-WACCM is suitable for achieving the aim of this study.

Data availability

The ERA5 dataset can be accessed via the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) at https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5. Monthly precipitation data are sourced from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.gpcp.html. Monthly SST data can be retrieved from https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html. NCEP-NCAR data are provided by NOAA and can be found at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.olrcdr.interp.html. The experiment data used in this study can be accessed by contacting the first author. Figures in this paper are created with Python 3.7.9, and the corresponding source codes are available from the first author upon request.

Code availability

All figures in this study were generated using Python 3.7.9, and the corresponding source code is available from the first author upon request.

References

Zepp, R., Callaghan, T. & Erickson, D. Effects of enhanced solar ultraviolet radiation on biogeochemical cycles. J. Photoch. Photobio. B 46, 69–82 (1998).

Thompson, D. et al. Signatures of the Antarctic ozone hole in Southern Hemisphere surface climate change. Nat. Geosci. 4, 741–749 (2011).

Previdi, M. & Polvani, L. Climate system response to stratospheric ozone depletion and recovery. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 140, 2401–2419 (2014).

Bandoro, J., Solomon, S., Donohoe, A., Thompson, D. W. & Santer, B. D. Influences of the Antarctic ozone hole on Southern Hemispheric summer climate change. J. Clim. 27, 6245–6264 (2014).

Son, S., Purich, A., Hendon, H., Kim, B. & Polvani, L. Improved seasonal forecast using ozone hole variability? Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 6231–6235 (2013).

Fogt, R., Perlwitz, J., Pawson, S. & Olsen, M. Intraü annual relationships between polar ozone and the SAM. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L04707 (2009).

Rogers, J. & Loon, H. Spatial variability of sea level pressure and 500 mb height anomalies over the Southern Hemisphere. Monthly Weather Rev. 110, 1375–1392 (1982).

Cai, W. & Watterson, I. Modes of interannual variability of the Southern Hemisphere circulation simulated by the CSIRO climate model. J. Clim. 15, 1159–1174 (2002).

Yuan, X. & Yonekura, E. Decadal variability in the Southern Hemisphere. J. Geophys. Res. 116, D19115 (2011).

Kang, S., Polvani, L., Fyfe, J. & Sigmond, M. Impact of polar ozone depletion on subtropical precipitation. Science 332, 951–954 (2011).

Zheng, F., Li, J., Wang, L., Xie, F. & Li, X. Cross-seasonal influence of the December-February Southern Hemisphere annular mode on March-May meridional circulation and precipitation. J. Clim. 2817, 6859–6881 (2015).

Wu, Z., Li, J., Wang, B. & Liu, X. Can the Southern Hemisphere annular mode affect China winter monsoon? J. Geophys. Res. 114, D11107 (2009).

Liu, T., Li, J. & Zheng, F. Influence of the boreal autumn southern annular mode on winter precipitation over land in the Northern Hemisphere. J. Clim. 28, 8825–8839 (2015).

Zhu, L. & Wu, Z. Climatic Influence of the Antarctic Ozone hole on the East Asian winter precipitation. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 184 (2024).

Lei, Y., Hoskins, B. & Slingo, J. Exploring the interplay between natural decadal variability and anthropogenic climate change in summer rainfall over China. Part I: observational evidence. J. Clim. 24, 4584–4599 (2011).

Wang, B., Wu, R. & Fu, X. Pacific-East Asia teleconnection: How does ENSO affect East Asian climate? J. Clim. 13, 1517–1536 (2000).

Wang, B., Li, J. & He, Q. Variable and robust East Asian monsoon rainfall response to El Nino over the past 60 years (1957-2016). Adv. Atmos. Sci. 34, 1235–1248 (2017).

Wu, Z., Wang, B., Li, J. & Jin, F. An empirical seasonal prediction model of the East Asian summer monsoon using ENSO and NAO. J. Geophys. Res. 114, D18 (2009).

Xie, S. et al. Indian Ocean Capacitor Effect on Indo-Western Pacific Climate during the Summer following El Nino. J. Clim. 22, 730–747 (2009).

Zha, P. & Wu, Z. Contribution of the Tibetan Plateau Snow Cover to the Record-breaking Rainfall Over the Yangtze River Valley in June 2020. Atmos.-Ocean 61, 122–134 (2023).

Chen, H., Zhou, T., Neale, R., Wu, X. & Zhang, G. Performance of the New NCAR CAM3.5 in East Asian Summer Monsoon Simulations: Sensitivity to Modifications of the Convection Scheme. J. Clim. 23, 3657–3675 (2010).

Ham, Y. et al. The Origin of Systematic Forecast Errors of Extreme 2020 East Asian Summer Monsoon Rainfall in GloSea5. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094179 (2021).

He, C. & Zhou, T. Responses of the Western North Pacific Subtropical High to Global Warming under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 Scenarios Projected by 33 CMIP5 Models: The Dominance of Tropical Indian Ocean-Tropical Western Pacific SST Gradient. J. Clim. 28, 365–380 (2014).

Xie, F. et al. An advanced impact of Arctic stratospheric ozone changes on spring precipitation in China. Clim. Dyn. 51, 4029–4041 (2018).

Xia, Y. et al. Stratospheric ozone loss enhances summer precipitation over the southern slope of the Tibetan Plateau. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103742 (2023).

Xie, F. et al. The upper tropospheric-lower stratospheric ozone drives summer precipitation and wildfire changes in West Siberia. Sci. Bull. 70, 255–262 (2025).

Thompson, D. W. J., Grise, K. M. & Forster, P. M. On the Role of Radiative Processes in Stratosphere–Troposphere Coupling. J. Clim. 22, 4154–4161 (2009).

Marshall, G. J. et al. Historical SAM Variability. Part II: Twentieth-Century Variability and Trends from Reconstructions, Observations, and the IPCC AR4 Models*. J. Clim. 22, 5346–5365 (2009).

Wang, B. & LinHo, X. Rainy season of the Asian–Pacific summer monsoon. J. Clim. 15, 386–398 (2002).

Wu, Z., Zhang, P., Chen, H. & Li, Y. Can the Tibetan Plateau snow cover influence the interannual variations of Eurasian heat wave frequency? Clim. Dyn. 46, 3405–3417 (2015).

Alexander, L. Extreme heat rooted in dry soils. Nat. Geosci. 4, 12–13 (2011).

Hirschi, M. et al. Petr, Observational evidence for soil-moisture impact on hot extremes in southeastern Europe. Nat. Geosci. 4, 17–21 (2011).

Higgins, R. & Shi, W. Dominant factors responsible for interannual variability of the summer monsoon in the southwestern United States. J. Clim. 13, 759–775 (2000).

Entin, J. et al. Temporal and spatial scales of observed soil moisture variations in the extratropics. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 11865–11877 (2000).

Lo, F. & Clark, M. Relationships between spring snow mass and summer precipitation in the southwestern United States associated with the North American monsoon system. J. Clim. 15, 1378–1385 (2002).

Robock, A., Mu, M., Vinnikov, K. & Robinson, D. Land surface conditions over Eurasia and Indian summer monsoon rainfall. J. Geophys. Res. 108, D44131 (2003).

Pan, L. Observed positive feedback between the NAO and the North Atlantic SSTA tripole. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L06707 (2005).

Gao, C., Li, G. & Xu, B. Weakening influence of spring soil moisture over the Indo-China Peninsula on the following summer mei-yu front and precipitation extremes over the Yangtze River basin. J. Clim. 33, 10055–10072 (2020).

Dong, X. et al. Local and non‐local atmospheric effects of abnormal soil moisture over Indochina during May and June. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 148, 2903–2926 (2022).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) (2023).

Huang, B. et al. Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, version 5 (ERSST v5): upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Clim. 30, 8179–8205 (2017).

Marshall, G. Trends in the Southern Annular Mode from observations and reanalyses. J. Clim. 16, 4134–4143 (2003).

Neale, R. et al. Description of the NCAR community atmosphere model (CAM 5.0). NCAR Tech. Note 1, 1–12 (2010).

Watanabe, M. & Kimoto, M. Atmosphere-ocean thermal coupling in the North Atlantic: a positive feedback. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 126, 3343–3369 (2000).

Tseng, K., Maloney, E. & Barnes, E. The consistency of MJO teleconnection patterns: an explanation using linear Rossby wave theory. J. Clim. 32, 531–548 (2019).

Cao, C. & Wu, Z. Modulation of the Tibetan Plateau snow cover on the interannual variations of the MJO-Related winter surface air temperature anomalies over East Asia. Clim. Dyn. 59, 3427–3437 (2022).

Zhou, T. & Wu, Z. Asian-Australian monsoon as a mediator on North American surface air temperature anomalies. Atmos. Res. 305, 107427 (2024).

Zhu, J. & Wu, Z. Indian Summer Monsoon’s Role in Shaping Variability in Arctic Sea Ice. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 264 (2024).

Zhu, L. & Wu, Z. To what extent can the ozone valley over the Tibetan Plateau influence the East Asian summer precipitation? npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 177 (2023).

Chiodo, G. & Polvani, L. The response of the ozone layer to quadrupled CO2 concentrations: implications for climate. J. Clim. 32, 7629–7642 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Data were made available through support from NSFC Major Research Plan on West-Pacific Earth System Multispheric Interactions (grant No. 92358302). This research was jointly supported by: The Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2023YFF0805100); The Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) program (Grant No. 2019QZKK0102); The University of Sydney–Fudan University Ignition Grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. designed this research under the guidance of supervisors Z.W. and B.W.; L.Z. made the data analysis and graphics. L.Z. prepared the initial draft, and all authors actively participated in providing feedback and engaging in discussions regarding the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, L., Wu, Z. & Wang, B. Role of Antarctic ozone in shaping East Asian summer precipitation variability. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 234 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01116-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01116-7