Abstract

The Tibetan Plateau, known as Asian water tower, plays a crucial role in regional water cycles and climate. However, limited in-situ cloud observations have hindered a comprehensive understanding of cloud microphysical processes over this region. To address this, a ground-based in-situ experiment was conducted in the southern Tibetan Plateau (STP) to investigate aerosol-cloud-precipitation interactions. Utilizing extensive microphysical measurements of aerosols and clouds, this study derived in-cloud water vapor supersaturation (SS) and examined its role in aerosol activation and cloud development. Results revealed that orographic clouds over the STP exhibit notably high SS levels, with an average SS of 0.36% and cloud case mean SS ranging from 0.1% to 1.27%. Such high SS compensates for the low hygroscopicity of Aitken-mode aerosols, facilitating their activation into cloud droplets. The resulting microphysical changes include increased droplet number concentrations, broader droplet spectra, and enhanced cloud liquid water content, which could promote collision-coalescence processes and precipitation formation. Moreover, these SS-induced microphysical changes may enhance cloud albedo and influence regional radiative forcing, potentially impacting atmospheric circulation and monsoon dynamics over the Tibetan Plateau. These findings highlight the critical role of high SS in cloud formation under conditions of weak aerosol activation potential, offering new insights into orographic cloud processes in high-altitude environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water vapor supersaturation (SS) is defined as the difference between actual water vapor pressure (e) in the atmosphere and the saturated vapor pressure (es), normalized by es,

SS plays a crucial role in cloud formation and evolution. It governs aerosol activation, directly influencing the initial cloud droplet number concentration1,2, while also modulating the condensation growth of cloud droplets, thereby shaping the cloud droplet size distribution (CDSD)3,4. As such, SS is a fundamental parameter in determining cloud microphysical properties5,6,7,8, with far-reaching implications for precipitation processes9,10 and cloud radiative effects11,12, ultimately influencing the global climate system13. Despite its significance, accurately quantifying SS remains methodologically challenging, as persistent gaps in mechanistic understanding hinder the development of robust model constraints14,15.

Meteorologists have long been intrigued by SS, yet a mature and reliable measurement method remains elusive. As early as the 1950s, Howell16 estimated SS generated by adiabatic cooling during air parcel ascent through numerical calculations, revealing that SS typically exceeds 0.1%, with extreme cases surpassing 1.0%. Twomey17 further investigated the influence of aerosol concentration on SS, highlighting that under similar dynamical conditions, cleaner environments often exhibit higher SS values. Building on Howell16, Richard18 modified the SS source term by incorporating radiative cooling rates to estimate SS in four radiation fog events observed in California, reporting SS ranging from 0.02% to 0.24%, though the effect of latent heat was neglected. With the development and application of supersaturated cloud chambers, some studies have attempted to infer SS indirectly by comparing simultaneously observed cloud droplet number concentration (NC) and the cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) spectrum19,20,21, which characterizes the relationship between CCN number concentration (NCCN) and SS. However, this approach offers only a coarse estimation of the average SS over extended periods, typically exceeding half an hour, depending on the SS cycling time in the CCN counter. Moreover, it tends to exhibit considerable bias when estimating lower SS values, such as those found in shallow cumulus clouds and fog, due to inherent measurement uncertainties in cloud chambers under low-SS conditions22,23,24. Recently, Kuang et al.25 developed an advanced aerosol–cloud sampling system designed to measure fog and cloud activation processes, which holds promise for providing new insights into the evolution of SS and its fluctuations26.

Based on Köhler theory1, the wet diameter of unactivated particles is positively correlated with SS. Gerber27 developed a saturation hygrometer to estimate SS by measuring the diameter of unactivated particles, though its measurements remain highly uncertain. Additionally, the H₂O analyzer from Licor can also be used to estimate SS by measuring the attenuation of infrared radiation by moist air28, but its absolute measurement uncertainty of 1% limits its effectiveness for SS investigations. The κ-Köhler theory simplifies activation process calculations by representing the complex chemical composition of aerosols with a single hygroscopicity parameter, κ29, offering an alternative approach for indirectly estimating SS. By combining measurements of dry particle number size distribution (PNSD), κ, and CDSD, the critical dry activation diameter (Ddc) can be calculated and used to the κ-Köhler equation to derive SS. It has been widely used to estimate SS in fog, revealing that SS in fog is generally below 0.1%. For instance, in suburban Paris, median SS in fog events ranges from 0.03% to 0.11%30, while in radiation fog over the North China Plain, SS ranges from 0.01% to 0.05%31, and in tropical rainforest radiation fog, the average SS is 0.07%32. Theoretically, higher SS values can occur in clouds20,33,34, potentially exceeding 1%, which would enable submicron aerosols to activate and form clouds9,35. However, studies on in-cloud SS are still limited, resulting in a poor understanding of its distribution and underlying mechanisms in clouds. Ground-based mountain cloud experiments offer a promising method for investigating in-cloud SS.

As the Asian water tower, the Tibetan Plateau plays a crucial role in regulating regional water resources36,37. Understanding the microphysical processes of cloud and precipitation in this region is therefore of great significance. However, relevant studies remain scarce, particularly those involving in-situ observations. To address the observational gap in high-altitude cloud regimes, we conducted the Ground In-situ Aerosol-Cloud-Precipitation Experiment on the southern Tibetan Plateau (GACPE-STP) during the South Asian summer monsoon period in 2023. Wang et al.38 found that aerosols in this region exhibit rather weak hygroscopicity (κ < 0.1), implying a low activation potential for cloud formation. Surprisingly, however, numerous cloud processes were observed during the experiment. Ground-based cloud imager recorded an average daily cloud cover of 0.7, while the fog monitor detected 145 orographic cloud cases, accumulating a total duration of 320 hours (see Fig. S1 in Supplementary Information). This suggests that the observational site may benefit from favorable cloud dynamical and moisture conditions, potentially generating higher SS that overcomes the weak cloud-forming potential of local aerosols, thereby enhancing cloud formation. A plausible explanation for the high in-cloud SS is the orographic lifting of moisture-laden air transported by the South Asian summer monsoon from the Bay of Bengal of the Indian Ocean as it ascends the Tibetan Plateau39.

During the South Asian summer monsoon, the abundant orographic clouds along the southern slope of the Tibetan Plateau serve as a natural laboratory for investigating aerosol–SS–cloud interactions in high-altitude cloud regimes. In this study, we estimate SS using two methods based on aerosol, CCN, and cloud measurements obtained from the GACPE-STP experiment, enabling us to test the hypothesis of high SS in orographic clouds over this region. Furthermore, we examine the influence of SS on aerosol activation and cloud microphysical properties, elucidating the mechanisms through which varying SS conditions modulate cloud precipitation and radiative properties. These findings provide valuable insights and observational evidence for aerosol–SS–cloud interactions over the Tibetan Plateau.

Results

In-situ observed high water vapor supersaturation in STP orographic clouds

In the GACPE-STP experiment, the simultaneous observation of weak aerosol cloud-forming potential38 and the frequent occurrence of clouds suggest the presence of high SS during cloud formation. We estimated SS indirectly using two methods. The first method draws from previous ground-based fog experiments30,31,32, where the effective SS (SSeff) is derived by applying the κ-Köhler equation to concurrently measured dry PNSD, κ, and CDSD, identifying the SS required for these aerosols to activate into the observed cloud droplets. The second method relies on measurements from a CCN counter (CCNC) and CDSD19,20,21, determining the SS (SSCCN) at which the NCCN equals NC. A detailed description of both methods and their associated uncertainties is provided in the Methods section.

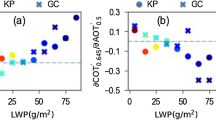

Figure 1 presents the overall characterization of SS in STP orographic clouds. During the GACPE-STP experiment, a total of 145 orographic cloud cases were observed, among which SSeff was calculated for 136 cases and SSCCN for 95 cases. Figure 1a shows the average SSeff and SSCCN for each cloud case, revealing relatively high SS in orographic clouds over this region. The mean SSeff across all clouds was 0.36%, and the mean SSCCN was 0.27%, both significantly higher than the typical SS values below 0.1% in fogs25,30,31,32,40, twice the 0.16% SS reported for marine stratocumulus clouds by Ditas et al.33, and slightly above the 0.10% to 0.50% range in marine boundary layer clouds by Gong et al.20. Moreover, SS varied notably among different cloud cases. Figure 1b shows the probability density distributions (PDFs) of SSeff and SSCCN, both exhibiting a distinct right-skewed pattern. Most SSeff and SSCCN values are concentrated between 0.1% and 0.3%, with the PDFs gradually decreasing as SSeff and SSCCN increase. The minimum and maximum mean SSeff among cloud cases were 0.10% and 1.27%, respectively, differing by more than an order of magnitude. This large variation implies substantial differences in cloud dynamical and moisture conditions during cloud formation. For instance, some parcels may have experienced cloud formation and moisture depletion before reaching the observation site, leading to lower SS upon subsequent cloud formation. Finally, SSeff and SSCCN exhibited consistent variation trends. Figure 1c further shows the relationship between mean SSeff and SSCCN, along with the corresponding linear fit, revealing a significant positive correlation (R² = 0.85), which supports the reliability of these estimates. Given SSCCN lower temporal resolution and relatively larger calculation uncertainties, SSeff is adopted for subsequent analyses.

a Mean effective supersaturation (SSeff) and supersaturation calculated from the CCN spectrum (SSCCN) for each cloud case. b Mean and standard deviation of SSeff and SSCCN, along with the probability density functions (PDFs). c Correlation between case-averaged SSeff and SSCCN, with the black line representing the linear fit.

The high SS observed in orographic clouds over this region can be attributed to large-scale circulation patterns. As the Asian Water Tower, the Tibetan Plateau receives abundant moisture from both the westerlies and the southern monsoon39. During the GACPE-STP experiment, the South Asian summer monsoon transported moisture-laden air from the Bay of Bengal of the Indian Ocean northward to the southern slope of the plateau. As these air masses ascended the terrain, they cooled adiabatically, with strong upward motion and abundant moisture supply enhancing the SS source term41. Simultaneously, the low aerosol concentration in this region38 reduced the SS sink term. These factors contributed to the high SS observed in the STP orographic clouds. This interpretation is supported by Figure S2 in Supplementary Information, which shows the average 700 hPa three-dimensional wind field and relative humidity distribution from ERA5 reanalysis over the STP during the experiment period. Additionally, the direct measurement of updraft velocity (w) provides strong supporting evidence for the reliability of the calculated SSeff values. Figure S3 presents the correlation between the directly measured w and SSeff, as well as the correlation between the ratio of w to aerosol number concentration (w/Na) and SSeff. The w was measured at 103 m above ground level using a three-dimensional scanning Doppler wind lidar (Wind3D 10k, LEICE Inc.). The observed positive correlations between w and SSeff, and between w/Na and SSeff, further support the reliability of the SSeff estimations.

High supersaturation compensates for limited aerosol activation efficiency

The question addressed in this section is how high SS affects the activation process of weakly hygroscopic aerosols in this region. The ability of aerosol particles to activate and form cloud droplets depends not only on their inherent activation potential, such as particle size and κ, but also on the ambient SS. The relationship between these three factors can be described by the κ-Köhler equation29,

where Ddc represents the critical dry activation diameter of the aerosol, and A can be considered a function of the absolute temperature. Figure 2a shows the variation of Ddc with κ and SS, along with the observed PDFs of κ and SS. When SS is fixed, as κ decreases, Ddc increases, indicating that fewer aerosols in the given dry PNSD can activate to form cloud droplets. Conversely, when κ is fixed, Ddc decreases as SS increases, meaning more aerosols in the given dry PNSD can activate to form cloud droplets. Therefore, high SS can compensate for the increase in Ddc caused by weak κ, thus promoting aerosol activation and cloud droplet formation.

a Relationship between supersaturation (SS), aerosol hygroscopicity (κ), and the critical dry diameter for activation (Ddc). The dashed box highlights the high-probability density function (PDF) region of observed κ and SS, corresponding to the distribution range of Ddc. b PDF of Ddc and its occurrence probability across different size ranges.

The observed PDFs of κ and SS together determine the theoretical range of Ddc distribution within the dashed box in Fig. 2a. Figure 2b further presents the observed PDF of Ddc and its occurrence probability across different size ranges. The mean Ddc for aerosol activation in the STP orographic clouds is 156 nm, implying that, on average, aerosols with dry diameters larger than 156 nm can activate to form cloud droplets during STP orographic cloud formation. Notably, the probability of Ddc being smaller than 100 nm is 25%, and the probability of Ddc being smaller than 50 nm is 2%. This indicates that there is a 25% chance for aerosol particles in the Aitken mode to activate and form cloud droplets, with a 2% chance for aerosol particles smaller than 50 nm to participate in cloud droplet formation. The observation further emphasizes the importance of studying the physicochemical properties and activation behavior of Aitken mode aerosols in the STP region. Local anthropogenic emissions42 and new particle formation events43,44 may contribute to the formation of Aitken mode aerosols, which could participate in cloud and precipitation processes, thereby impacting regional weather and climate. Additionally, in the STP region, strong upward motion not only generates high SS but also induces its rapid fluctuations. The kinetic effect may enable small aerosol particles to overcome equilibrium limitations45 and contribute to cloud droplet formation. Such a non-equilibrium activation process could have a significant impact on the microphysical processes of STP orographic clouds.

Supersaturation impact on cloud microphysics

We further examined the impact of SS on cloud microphysics by categorizing SS into three distinct ranges. The first bin represents the lowest 33.3% of SS values (Low SS), the second bin corresponds to the middle 33.3%–66.6% range (Median SS), and the third bin encompasses the highest 33.3% of SS values (High SS). The mean SS for each bin is 0.14%, 0.26%, and 0.69%, with corresponding standard deviations of 0.03%, 0.06%, and 0.31%, respectively. Each bin contains 96289 CDSDs. The mean cloud microphysical properties were subsequently calculated for each SS bin and for all CDSDs, including NC, cloud droplet effective diameter (De), liquid water content (LWC), droplet spectral dispersion (ε), cloud-to-rain autoconversion rate (Pauto), and mean cloud extinction coefficient (βe). The formulas used to derive these quantities are provided in the Methods section. The calculated mean values of these properties in the orographic clouds within one hour after cloud formation during the GACPE-STP experiment are as follows: NC = 124 cm−3, De = 8.9 µm, LWC = 0.023 g m−3, ε = 0.33, Pauto = 2.56 × 10−14 g cm−3 s−1, and βe = 8.0 km−1, which correspond to the microphysical properties labeled as ALL in Fig. 3a.

a Mean values of cloud droplet number concentration (NC), effective diameter (De), liquid water content (LWC), droplet spectral dispersion (ε), cloud-to-rain autoconversion rate (Pauto), and mean cloud extinction coefficient (βe) under different supersaturation (SS) bins. b Mean cloud droplet size distribution under different SS bins. L represents the lowest 33.3% of SS (Low SS), M represents the middle 33.3–66.6% range of SS (Median SS), H represents the highest 33.3% of SS (High SS), and ALL represents all range of SS (ALL SS).

The distributions of cloud microphysical properties across different SS bins are shown in Fig. 3. As SS increases, Ddc decreases, leading to more aerosols activating into cloud droplets and resulting in an increase in NC. However, the rate of increase in mean NC is not proportional to the increase in mean SS across the bins. Compared to the first bin, the mean SS in the second bin increases by 86%, while the mean NC increases by 31%. From the second to the third bin, the mean SS increases by 165%, but the mean NC rises by just 5%. This discrepancy may arise because aerosols act as a sink for SS, and at higher SS, Na tends to be lower41,46. The mean Na for the first, second, and third bins are 1035 cm−3, 704 cm−3, and 454 cm−3, respectively. Consequently, although higher SS enhances the fraction of aerosol activation, the lower Na limits the increase in mean NC. With increasing SS, the condensation growth of cloud droplets accelerates, leading to increases in both the volume mean diameter (not shown) and De. Higher SS promotes both droplet activation and condensational growth, resulting in increases in LWC and ε. As shown in Fig. 3b, with increasing SS, the CDSD broadens toward higher number concentrations and larger droplet sizes, resulting in an upward and rightward shift of the CDSD. The CDSD broadening significantly enhances Pauto, with the mean Pauto in the third bin being 67 times that of the first bin, indicating an increased probability of cloud droplet collision and precipitation formation under higher SS conditions. It should be noted that Pauto only represents the probability of droplet collision and coalescence processes within the cloud. Due to the lack of direct precipitation measurements, it is difficult to determine whether the observed changes in microphysical properties under high SS conditions actually lead to real precipitation formation. Additionally, βe increases with SS, with the mean βe in the third bin being 2.4 times that of the first bin. Assuming constant cloud thickness, higher SS results in stronger cloud reflectivity of solar shortwave radiation, thereby enhancing the cloud cooling effect. Furthermore, the persistent and strong updrafts during the South Asian monsoon in the STP region sustain high SS conditions, theoretically favoring the formation of thicker cloud layers and even stronger shortwave radiative cooling. It is important to note that while higher SS leads to increased NC and enhanced cloud radiative cooling, this is fundamentally different from the Twomey effect47,48, as both De and LWC increase with rising SS.

In addition, we examined the impact of different binning methods on assessing the relationships between SS and cloud properties by dividing the SS range of 0–1% into 10 equal intervals (0.1% increments). Results are shown in Fig. S4 of the Supplementary Information. Overall trends are largely consistent with those in Fig. 3 based on three SS bins. However, some discrepancies are noted. For instance, De increases continuously with SS in Fig. 3, but in Fig. S4, it first increases and then slightly decreases. This may be due to enhanced aerosol activation at higher SS, resulting in smaller droplets. The differences stem from the binning approaches: equal sample sizes in Fig. 3 vs. equal SS intervals in Fig. S4, which can influence the assessment of SS and cloud property relationships.

Discussion

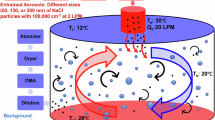

The Tibetan Plateau, often referred to as the Asian water tower, plays a crucial role in the regional water cycle and climate change. However, current studies on the cloud characteristics of the Tibetan Plateau primarily rely on satellite remote sensing, with in-situ observations remaining limited, resulting in a restricted understanding of the cloud microphysical mechanisms in this region. To address this gap, we conducted the GACPE-STP experiment on the southern slope of the Tibetan Plateau, focusing on aerosol-cloud-precipitation interactions. This study, based on extensive microphysical observations of orographic clouds obtained during the experiment, combined with aerosol and CCN measurements, estimates the distribution of water vapor supersaturation in clouds and investigates the impact of SS on aerosol activation and cloud microphysical properties. Figure 4 illustrates the formation of SS and its effects on cloud microphysics in the STP topographic clouds.

Wang et al.38 found that the aerosol activation ability in this region is weak. However, a large number of orographic clouds were observed during the GACPE-STP experiment, suggesting that the region may have favorable dynamical conditions for cloud formation and high SS. Using two indirect methods for calculating SS, the dry PNSD combined with κ and CDSD, and the NCCN(SS) combined with CDSD, both reveal relatively high SS in the orographic clouds, with the SS values obtained from both methods showing a strong positive correlation. The range of mean SS variation for the 135 cloud cases is between 0.1% and 1.27%, with the average SS of all clouds being 0.36%, which is higher than that of marine clouds20,33,34.As the air mass rises, adiabatic cooling causes a decrease in temperature, which lowers the saturated vapor pressure (es). When es drops below the actual vapor pressure (e), SS occurs. The cooling of the moist air mass lifted by the topography of the Tibetan Plateau, combined with abundant moisture from the South Asian monsoon, is the main reason for the high SS in the STP orographic clouds. Differences in water vapor content and dynamic conditions of the air mass cause variations in SS within the clouds.

The SS, together with particle size and κ, determines whether particle can activate into cloud droplet. High SS can overcome weak κ, promoting aerosol activation into clouds. On average, when orographic clouds form in this region, dry aerosols with diameters greater than 156 nm can activate into cloud droplets. Notably, there is a 25% chance that aerosols from the Aiken mode can participate in cloud droplet activation when orographic clouds form, and even a 2% chance that aerosols smaller than 50 nm can participate in cloud droplet activation. Therefore, in high SS environments, the aerosol activation efficiency is enhanced, which may amplify the aerosol indirect effects of the ultrafine particles from new particle formation and the anthropogenic emissions. Moreover, high SS significantly changes the cloud microphysical characteristics. Increased SS results in more and larger cloud droplets, higher LWC, and a broader CDSD, which may enhance the probability of cloud droplet collision, precipitation formation, and the cloud cooling effects. The enhanced cooling effects of the STP clouds could influence the atmospheric circulation driven by the plateau thermal effects, such as the monsoon intensity, thereby affecting water vapor transport and the distribution of precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau and surrounding regions.

To the best of our knowledge, our findings provide the first observational evidence of high SS in the topographic clouds on the southern Tibetan Plateau during the South Asian summer monsoon. The high SS promotes the activation of aerosols with weak hygroscopicity, particularly Aitken-mode aerosols, into cloud droplets, significantly altering the cloud microstructure and subsequently modulating cloud-precipitation and cloud-radiation properties. Future studies should prioritize understanding the coupled interactions between aerosols, cloud dynamics, and cloud microphysics under such high SS conditions to quantify their regional climatic implications. Specifically, the sensitivity of cloud microphysics to aerosol properties under cloud dynamical constraints, and its influence on regional aerosol indirect effects, will constitute a focus of our subsequent research within the framework of the GACPE-STP experiment. Furthermore, integrating these micro-scale mechanisms into models is essential for evaluating how changes in cloud radiative cooling and precipitation over the southern Tibetan Plateau influence Asian monsoon dynamics and hydrological extremes under warming scenarios. However, it is important to note that there may be complex feedback, where the effects of cloud precipitation and radiative forcing on the South Asian monsoon could, in turn, influence cloud properties over the Plateau and surrounding regions. Recent changes in the South Asian summer monsoon have decreased total cloud cover over the Tibetan Plateau49, and this intricate feedback mechanism warrants further investigation.

Methods

Experiment and data

The GACPE-STP experiment was conducted at Yadong County (27.42° N, 88.90° E, 3136 m a.s.l.), situated on the southern slope of the Tibetan Plateau, from August 17th to October 18th, 2023. A detailed description of the experiment can be found in Wang et al.38. Here, we focus on the observational instruments and data methods employed in this study.

The Fog Monitor (FM, model 120; DMT Inc.) was used for in-situ measurement of CDSD in orographic clouds, covering a size range from 2 to 50 µm, with a sampling frequency of 1 Hz. Prior to the experiment, the FM120 was calibrated for droplet size using standard particles. During the experiment, the FM120 was positioned at the windward slope edge of the observation site, ensuring an unobstructed view in front of the sampling inlet. The CCN Counter (CCNC, model 200; DMT Inc.) measured the NCCN under different SS conditions. Nine distinct SS levels were cycled in CCNC: 0.07%, 0.1%, 0.15%, 0.2%, 0.3%, 0.4%, 0.5%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, with each SS cycle lasting approximately 1 hour. Prior to the experiment, the SS within the cloud chamber was calibrated using ammonium sulfate, following the procedures outlined in Rose et al.50. During data processing, the correction methods from Wang et al.23 and Tao et al.24 were applied to exclude unactivated particles from the CCN measurements. The Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS, model 3938L50; TSI Inc.) was utilized to measure the dry PNSD over a size range of 18.8 to 685.4 nm, with the distribution divided into 101 bins. A full PNSD scan was conducted every two minutes. The All-sky Cloud Imager (CSI, model 50; KEYTEC Inc.) was used to capture cloud imagery in both visible light during the day and infrared during the night, providing data on cloud fraction. The measurement uncertainties should be acknowledged. The uncertainty in the dry PNSD measurements is within 10%51. Regarding the SS setting in CCNC, Gysel and Stratmann52 reported that an achievable accuracy is about 10% (relative) at SS > 0.2% and less than 0.02% (absolute) at the lower SS levels. FM sampling efficiency showed particle losses typically below 10% for droplet diameters up to 10 µm, with losses increasing progressively for larger droplets53.

Cloud microphysical parameters calculating and cloud case identifying

The NC, mean droplet diameter (Dm), De, LWC, ε were calculated from the CDSD using the following equations:

where ni and Di are the number concentration and diameter of the ith bin droplet in CDSD, respectively. Furthermore, the Pauto can be calculated based on the aforementioned cloud microphysical quantities,

where k equals to 1.1 × 1010 g−2 cm3 s−1, and μ is an empirical constant set to 2, as referenced by Liu et al.54. A larger Pauto indicates a stronger cloud-to-rain autoconversion, suggesting a higher probability of droplet collision and coalescence processes leading to precipitation formation within the cloud. Additionally, the ratio of cloud optical thickness55 to cloud thickness represents the mean cloud extinction coefficient (βe), which can be expressed as,

A larger βe indicates a stronger ability of the cloud layer to reflect solar shortwave radiation per unit thickness.

A CDSD is classified as in-cloud when both NC ≥ 10 cm−3 and LWC ≥ 0.001 g m−3 are simultaneously satisfied56,57. A cloud case is defined as a period lasting more than 10 minutes, during which at least 50% of the minutes contain droplets meeting the in-cloud criteria58. A gap of at least 10 minutes is required between two cloud cases. Based on these criteria, a total of 145 orographic cloud cases were identified, encompassing over 1.15 million CDSDs with a cumulative duration of 320 hours. Among these 145 cases, 65 cases lasted longer than 1 hour, with the longest case reaching 28 hours. In this study, only data from the first hour after cloud case formation were analyzed. Prolonged cloud periods are more likely to undergo non-adiabatic processes, such as advection and sedimentation, which can alter the PNSD and CDSD and compromise the reliability of SS calculations.

Methods for calculating supersaturation

Cloud droplets form when aerosols activate under specific SS conditions. Given aerosol and cloud droplet characteristics, SS can be estimated from activation theory. As shown in Fig. 5, two methods were employed in this study to indirectly calculate SS. The first method utilizes simultaneously measured dry PNSD and CDSD, combined with the κ parameterization during the experiment provided by Wang et al.38, to derive the effective SS (SSeff). Since particle size has a greater influence on activation than chemical composition59, larger aerosols can activate into cloud droplets at a given SS, whereas smaller aerosols grow hygroscopically without activating, forming unactivated haze. Based on the κ-Köhler equation, the critical droplet activation diameter (Dc) corresponding to a dry aerosol diameter (Dd) can be determined,

By iteratively decreasing Dd from larger to smaller sizes, both dry PNSD and CDSD are integrated from Dd and Dc as the lower limits, respectively. The corresponding Dd and Dc are obtained when the two integrals become equal. Subsequently, SSeff is calculated using the inverse relationship between Dc and critical SS23,

Due to the generally high SS, Dc is smaller than the FM measurement limit of 2 µm in most cases. In these situations, Ddc is determined by integrating the dry PNSD in reverse until it equals the observed NC, and SSeff is calculated using Eq. 2. This approach neglects activated droplets smaller than 2 µm, leading to an underestimation of SSeff. Additionally, the upper limit of the dry PNSD is constrained to 685.4 nm by the SMPS measurement range, which results in an underestimation of CCN larger than this threshold and consequently leads to an overestimation of SSeff. To assess the bias, data from 10 randomly selected cloud cases (Case IDs: 15, 28, 30, 65, 76, 117, 119, 134, 140, and 142) were analyzed, with the results presented in Figure S5 of the Supplementary Information. Assuming that activated droplets smaller than 2 µm account for 10% (20%) of NC, the case-averaged SSeff would be underestimated by 3.0% to 8.5% (5.9% to 17.8%), with mean underestimation of 5.6% (11.2%) in relative. Conversely, if aerosols larger than 685.4 nm contribute 1% (2%) of the total Na, SSeff would be overestimated by 2.3% to 6.7% (4.6% to 13.4%), with mean overestimation of 4.4% (9.0%) in relative.

The second method estimates SSCCN using simultaneously observed NCCN(SS) and NC. The CCNC cloud chamber generates a controlled SS along its centerline, allowing ambient aerosols to grow in the supersaturated environment, where the concentration of activated droplets, NCCN, is measured. By cycling through different SS levels, the relationship between NCCN and SS can be obtained, typically following a power-law function17. SSCCN is calculated through linear interpolation by equating the observed NC with NCCN(SS). Given that a complete SS cycle takes about one hour, the hourly averaged NCCN(SS) is used for interpolation, introducing potential bias into SSCCN estimation. Additionally, at low SS levels, the accuracy of SS within the cloud chamber diminishes. At high SS levels, the Dc may fall below the 2 µm detection limit of the FM, and interpolation becomes infeasible when SS exceeds 0.7%. These factors affect the absolute accuracy of SSCCN but have a less impact on its relative trends. Therefore, this study uses the positive correlation between SSCCN and SSeff to validate the reliability of SSeff, while all analyses concerning absolute SS values are based on SSeff rather than SSCCN.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28675295.

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study are available from Yuan Wang (wang_yuan@lzu.edu.cn) and Jiming Li (lijiming@lzu.edu.cn) upon request.

References

Köhler, H. The nucleus in and the growth of hygroscopic droplets. Trans. Faraday Soc. 32, 1152–1161 (1936).

Wang, Y. et al. Aerosol activation characteristics and prediction at the central European ACTRIS research station of Melpitz, Germany. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 15943–15962 (2022).

Maxwell, J. C. & Sir, N. The Scientific Papers of James Clerk Maxwell, II (ed. Niven, W. D.) 636-640 (Cambridge University Press, UK, 1890).

Raatikainen, T. et al. A coupled observation – modeling approach for studying activation kinetics from measurements of CCN activity. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 4227–4243 (2012).

Chen, J. et al. New understanding and quantification of the regime dependence of aerosol-cloud interaction for studying aerosol indirect effect. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 1780–1787 (2016).

Chandrakar, K. K. et al. Influence of Turbulent Fluctuations on Cloud Droplet Size Dispersion and Aerosol Indirect Effects. J. Atmos. Sci. 75, 3191–3209 (2018).

Shaw, R. A. et al. Cloud– Aerosol–Turbulence Interactions: Science Priorities and Concepts for a Large-Scale Laboratory Facility. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 101, E1026–E1035 (2020).

Grabowski, W. W. & Morrison, H. Supersaturation, buoyancy, and deep convection dynamics. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 13997–14018 (2021).

Fan, J. et al. Substantial convection and precipitation enhancements by ultrafine aerosol particles. Science 359, 411–418 (2018).

Zhao, C. et al. Observational evidence and mechanisms of aerosol effects on precipitation. Sci. Bull. 69, 1569–1580 (2024).

Morrison, H. & Grabowski, W. W. Modeling supersaturation and subgrid-scale mixing with two-moment bulk warm microphysics. J. Atmos. Sci. 65, 792–812 (2008).

Santos Gutiérrez, M. & Furtado, K. Steady-state supersaturation distributions for clouds under turbulent forcing. J. Atmos. Sci. 81, 209–224 (2024).

Bellouin, N. et al. Bounding global aerosol radiative forcing of climate change. Rev. Geophys. 58, e2019RG000660 (2020).

Yang, F. et al. A new approach to estimate supersaturation fluctuations in stratocumulus cloud using ground-based remote sensing measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 12, 5817–5828 (2019).

Shaw, R. A. et al. Scientific directions for cloud chamber research: instrumentation, modeling, new chambers, and emerging chamber concepts. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 106, E770–E781 (2025).

Howell, W. The growth of cloud drops in uniformly cooled air. J. Atmos. Sci. 6, 134–149 (1949).

Twomey, S. The nuclei of natural cloud formation part II: The supersaturation in natural clouds and the variation of cloud droplet concentration. Geofis puraAppl 43, 243–249 (1959).

Richard, D. H. Low. Microphysical and meteorological measurements of fog supersaturation. Tellus 27, 507–513 (1975).

Hudson, J. G. & Svensson, G. Cloud microphysical relationships in California marine stratus. J. Appl. Meteorol. (1988-2005) 34, 2655–2666 (1995).

Gong, X. et al. Maximum supersaturation in the marine boundary layer clouds over the North Atlantic. AGU Adv. 4, e2022AV000855 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Sensitivity of cloud microphysics to aerosol is highly associated with cloud water content: Implications for indirect radiative forcing. Atmos. Res. 309, 107552 (2024).

Roberts, G. C. & Nenes, A. A continuous-flow streamwise thermal-gradient CCN chamber for atmospheric measurements. Aerosol Sci. Tech. 39, 206–221 (2005).

Wang, Y. et al. A new method for distinguishing unactivated particles in cloud condensation nuclei measurements: Implications for aerosol indirect effect evaluation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 14185–14194 (2019).

Tao, J. et al. Kinetic limitations affect cloud condensation nuclei activity measurements under low supersaturation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL101603 (2023).

Kuang, Y. et al. Divergent impacts of biomass burning and fossil fuel combustion aerosols on fog-cloud microphysics and chemistry: novel insights from advanced aerosol-fog sampling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107147 (2024).

Kuang, Y. et al. Theoretical framework for measuring cloud effective supersaturation fluctuations with an advanced optical system. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 25, 1163–1174 (2025).

Gerber, H. E. A saturation hygrometer for the measurement of relative humidity between 95 and 105%. J. APPL METEOROL CLIM 19, 1196–1208 (1980).

Korolev, A. & Isaac, G. A. Relative humidity in liquid, mixed–phase, and ice clouds. J. Atmos. Sci. 63, 2865–2880 (2006).

Petters, M. D. & Kreidenweis, S. M. A single parameter representation of hygroscopic growth and cloud condensation nuclei activity. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 1961–1971 (2007).

Mazoyer, M. et al. Experimental study of the aerosol impact on fog microphysics. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 4323–4344 (2019).

Shen, C. et al. Method to estimate water vapor supersaturation in the ambient activation process using aerosol and droplet measurement data. J. Geophys Res-Atmos 123, 10606–10619 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Observational study of the physical and chemical characteristics of the winter radiation fog in the tropical rainforest in Xishuangbanna, China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 64, 1982–1995 (2021).

Ditas, F. et al. Aerosols-cloud microphysics-thermodynamics-turbulence: evaluating supersaturation in a marine stratocumulus cloud. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 2459–2468 (2012).

Dedrick, J. L. et al. Competition response of cloud supersaturation explains diminished Twomey effect for smoky aerosol in the tropical Atlantic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 122, e2412247122 (2025).

Svensmark, H., Enghoff, M. B., Svensmark, J., Thaler, I. & Shaviv, N. J. Supersaturation and critical size of cloud condensation nuclei in marine stratus clouds. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL108140 (2024).

Kang, S. et al. Review of climate and cryospheric change in the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 1–8 (2010).

Liu, Y. et al. Aerosol-cloud interactions over the Tibetan Plateau: an overview. Earth-Sci. Rev. 234, 104216 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. In-situ observations reveal weak hygroscopicity in the Southern Tibetan Plateau: implications for aerosol activation and indirect effects. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 77 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Aerosol forcing regulating recent decadal change of summer water vapor budget over the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 15, 2233 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. Characterization of fog microphysics and their relationships with visibility at a mountain site in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 25, 3253–3267 (2025).

Rogers, R. R. & Yau, M. K. A Short Course in Cloud Physics (3rd Edition). (Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann, UK, 1996).

Zhang, X. et al. Characterization of aerosol properties from the burning emissions of typical residential fuels on the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 14296–14305 (2022).

Lai, S. et al. New particle formation induced by anthropogenic–biogenic interactions on the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 2535–2553 (2024).

Tang, L. et al. High frequency of new particle formation events driven by summer monsoon in the central Tibetan Plateau, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 4343–4359 (2023).

Nenes, A. et al. Kinetic limitations on cloud droplet formation and impact on cloud albedo. Tellus B 53, 133–149 (2001).

Lathem, T. L. & Nenes, A. Water vapor depletion in the DMT continuous-flow CCN chamber: effects on supersaturation and droplet growth. Aerosol Sci. Tech. 45, 604–615 (2011).

Twomey, S. Pollution and the planetary albedo. Atmos. Environ. 8, 1251–1256 (1974).

Twomey, S. The influence of pollution on the shortwave Albedo of cloud. J. Atmos. Sci. 34, 1149–1152 (1977).

Wu, Y. et al. Cloud properties and dynamics over the Tibetan Plateau–A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 248, 104633 (2023).

Rose, D. et al. Calibration and measurement uncertainties of a continuous-flow cloud condensation nuclei counter (DMT-CCNC): CCN activation of ammonium sulfate and sodium chloride aerosol particles in theory and experiment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 1153–1179 (2008).

Wiedensohler, A. et al. Mobility particle size spectrometers: Calibration procedures and measurement uncertainties. Aerosol Sci. Tech. 52, 146–164 (2018).

Gysel, M. & Stratmann, F. WP3 – NA3: In-situ chemical, physical and optical properties of aerosols, Deliverable D3.11: Standardized protocol for CCN measurements. Tech. Rep. http://www.actris.net/Publications/ACTRISQualityStandards/tabid/11271/language/en-GB/Default.aspx (2013) (last access: 20 May 2025).

Spiegel, J. K. et al. Evaluating the capabilities and uncertainties of droplet measurements for the fog droplet spectrometer (FM-100). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 5, 2237–2260 (2012).

Liu, Y. et al. Parameterization of the autoconversion process. Part II: Generalization of Sundqvist-Type parameterizations. J. Atmos. Sci. 63, 1103–1109 (2006).

Stephens, G. L. Radiation profiles in extended water clouds. II: Parameterization schemes. J. Atmos. Sci. 35, 2123–2132 (1978).

Deng, Z. et al. Statistical analysis of microphysical properties and the parameterization of effective radius of warm clouds in Beijing area. Atmos. Res. 93, 888–896 (2009).

Lu, C. et al. Reconciling contrasting relationships between relative dispersion and volume-mean radius of cloud droplet size distribution. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD031868 (2020).

Zhang, P. et al. Improved parameterization of cloud droplet spectral dispersion expected to reduce uncertainty in evaluating aerosol indirect effects. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL111643 (2025).

Dusek, U. et al. Size matters more than chemistry for cloud-nucleating ability of aerosol particles. Science 312, 1375–1378 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Innovative Research Group Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 42421001, the Regional Innovation and Development Joint Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. U24A20604, the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (STEP) under Grant No. 2019QZKK0602, the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 42205072, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under Grant lzujbky-2024-jdzx07 and lzujbky-2024-jdzx04.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W., J.L., and J.H. designed the study and received the funding. Y.W. & F.F. analyzed the data and led the writing. Y.W. & J.S. conducted the field campaigns. All authors contributed to discussion, review, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Fang, F., Li, J. et al. High effective supersaturation offsets low aerosol hygroscopicity to promote orographic cloud formation over the southern Tibetan Plateau. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 231 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01119-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01119-4