Abstract

The ‘emergence year’ Ye is defined as the start of a future period during which precipitation consistently exceeds the maximum value of the past historical period. Emergence years of future anthropogenic changes in annual average precipitation (Pav) and annual maximum 1-day precipitation (P1d) were projected using high-resolution global atmospheric models with 20-km and 60-km grid-size for the period 1950-2099. A total of 10,000 randomized time series representing the time evolution of decadal natural variability enabled us to directly evaluate estimated frequency distributions (EDFs) on a grid point basis. Ye for both Pav and P1d generally occur earlier at high latitudes than they are elsewhere, and Ye(P1d) is generally later than Ye(Pav). Ye(P1d) covers a larger area than Ye(Pav) does and Ye(P1d) may occur earlier in the tropics and mid-latitudes than Ye(Pav). Ye occurs earlier in scenarios with higher anthropogenic emissions than in scenarios with lower emissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of anthropogenic climate change refers to a change in climate (signal, S) becoming larger than the amplitude of natural variability (noise, N). The time of emergence (ToE) is defined as the time when a signal related to anthropogenic climate change is detected above the background noise of natural climate variability1,2,3,4. The concepts of the emergence of anthropogenic climate change and ToE are applicable to both the detection of change signal in observational time series, and in future projections by climate models. The term ‘emergence’ is sometimes referred to as ‘expulsion’. Some authors prefer the latter term as it highlights the forced nature of ‘emergence’, whereas the term ‘emergence’ makes the process seem passive5.

Methods for identifying ToE can be classified into four types; (1) the ToE is determined by a threshold value of a signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio evaluated from baseline, historical, or present-day time series, and target or future time series1,2,6; (2) the ToE is estimated from the difference in probability density function (PDF) between baseline and target time periods3,7,8,9; (3) the ToE is evaluated by hypothesis testing method such as the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the Student’s t-test10,11,12; and (4) The ToE is estimated by a non-parametric approach comparing threshold values (maximum or minimum) in the baseline period with time series of the target period13,14,15.

The ToE of anthropogenic climate change in future projections has been widely explored for basic meteorological variables such as surface air temperature and precipitation2. As the natural variability of precipitation is larger than that of temperature relative to the anthropogenic signal16,17,18,19,20, the detection of precipitation response to anthropogenic forcing has large uncertainties21, with the ToE of precipitation change tending to be delayed relative to that of temperature10.

Single-model initial-condition large ensembles (SMILEs) provide an effective approach to evaluating the influence of internal variability on anthropogenic signal emergence6,22. In the case of SMILEs in multiple climate models with very high resolution (0.5° and 1.0°), the area of anthropogenic precipitation change will exceed 80% of the global area by the year 210023. Climate models with higher horizonal resolution outperform lower-resolution models in simulating precipitation24,25, and global warming projections with higher horizontal resolution may be more reliable in projecting future precipitation changes.

Here, we used high-horizontal-resolution global climate models with grid sizes of 20 km (0.1875°) and 60 km (0.5625°) for the period from the mid-20th century to the end of the 21st century to identify the ToE of anthropogenic precipitation change. We created and analyzed 10,000 randomized time series, and used them to estimate the relative frequency of ToE15.

Results

Definition of emergence year

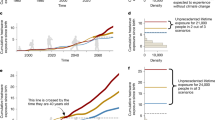

Here, we define the ‘emergence year’ Ye as being the start of a period in which precipitation consistently exceeds the maximum value obtained during the historical period in each continuous experiment from past to future15. The black line in Fig. 1a is an example of the time series of the decadal average of Pav in a historical simulation (SPD) and a future simulation (SFD85) at a grid point in the central tropical Pacific. The data point for the year 1960 represents the ten-year average for the period 1955-1964, with ‘year’ is often used to mean ‘the decade centered on the year’ in this paper. The blue horizontal line in Fig. 1a indicates the maximum value of the historical experiment attained in 1970. Precipitation after 2050, in a future experiment, continuously exceeded the maximum value of the historical experiment. The emergence year Ye is thus 2050.

a The black line with open circle is an example of the time series of decadal average for annual mean precipitation Pav simulated by the MRI-AGCM3.2S model at the grid point (170.0625°W, 0.094°N). The location of the grid point is shown in X mark in the inset map. In this figure, for example, the data point for the year 1960 is regarded as the 10-year average over the period 1955-1964. The historical simulation covers the 60-year period 1955-2014. The future simulation for the emission scenario RCP8.5 covers the 85-year period 2015-2094. The blue horizontal line denotes the maximum value of 2.35 mm day−1 in the historical simulation at year 1970. The black horizontal line denotes the value of 2.84 mm day−1 at the emergence year 2050. The two green lines show the one standard deviation range of decadal natural variability Vd relative to decadal average time series (black line with open circles). The red line is one example of a randomized time series generated with the Monte Carlo method within the range of decadal variability (two green lines). b The time series of year-to-year natural variability Sy (t) (black line) and decadal variability Sd (t) (green line) of Pav, where t is time. Sy (t) is the standard deviation of year-to-year variability for ten years period. For example, Sy (t) at year 1970 is the year-to-year standard deviation from 1965 to 1974. The decadal variability was evaluated using the ratio of climatological decadal variability Vd to climatological year-to-year variability Vy based on detrended historical simulation. c Estimated frequency distribution (EFD) emergence year for 10,000 randomized time series. Vertical black solid line shows the average of emergence years av (Ye) (year 2059.5). Two black dash lines show the range of one standard deviation sd (Ye) (11.8 years) above and below the average av(Ye). Existence rate of emergence year E is 99.68% which is equal to the integral of whole EFD.

Geographical distribution of emergence year

The geographical distribution of average of emergence year av (Ye) for annual average precipitation Pav is shown in Fig. 2a (color shading) for the SFD85 simulation. Uncertainty information on future projections is indicated by horizontal hatching where standard deviation of emergence year sd (Ye) is less than 10 years and by vertical hatching where the existence rate E is larger than 90%. Smaller sd (Ye) and larger E values give smaller uncertainties. The emergence year is earlier (red color in Fig. 2a) in high latitudes of both hemisphere than in the tropics and mid-latitudes (green). In some areas of the subtropics, where dry conditions prevail under the present-climate, none of the ensemble members exhibit an emergence prior to 2100. Such areas are left blank (i. e. appear white). The emergence year av (Ye) for P1d is shown in Fig. 2b. In high latitudes, the emergence year for annual maximum 1-day precipitation P1d (green, around year 2080, Fig. 2b) which is later than that for Pav (red, around year 2030, Fig. 2a). The global average of av (Ye) for Pav (2066.7) is earlier than that of P1d (2074.4). Emergence for Pav (Fig. 2a) is missing over the Atlantic Ocean and the southern Indian Ocean, whereas that of P1x (Fig. 2b) does occur over these regions in some ensemble members. Although Ye (P1d) is generally later than Ye (Pav), the total area over which emergence occurs is actually larger for P1d than it is for Pav. The dependence of area of emergence-year existence on precipitation intensity is shown in Fig. S6. The area of emergence-year existence for intense precipitation is larger than that for moderate or average precipitation pav. Heavier precipitation yields a larger area of emergence-year existence.

a Color shading shows the geographical distribution of av(Ye) for annual precipitation Pav in the simulation SFD85. The horizontal hatching denotes that sd(Ye) is less than 10 year. The vertical hatching denotes that the existence rate of the emergence year E exceeds 90%. Regions where none of the ensemble members exhibit an emergence prior to 2100 are left blank (i. e. appear white). Value of ‘av’ above the panel shows global average. b Same as a but for the annual maximum daily precipitation P1d. c Difference of emergence year as Ye(P1d) minus Ye(Pav). Hatched regions show difference exceeding the statistical significance level of 95% based on Student’s t-test. d–f Same as a–c but for HFD85. g–i Same as a–c but for HFD60. j–l Same as a–c but for HFD45. m–o Same as a–c but for HFD26.

The difference in emergence years between Pav and P1d is shown in Fig. 2c as P1d minus Pav. As is expected from Fig. 2a, b, most of the region is characterized by the later occurrence of an emergence year for P1d (blue color). In contrast, Ye (P1d) occurs earlier than Ye (Pav) in some regions in lower latitudes and mid-latitudes (red). These findings are consistent with future projections by CMIP5 models15. In these regions, the likelihood of extreme precipitation events might increase as unprecedented conditions will likely be encountered sooner, and such conditions can be difficult to manage26.

In the case of HFD85 (Fig. 2d, e), the distribution of emergence year is qualitatively similar to that of SFD85 (Fig. 2a, b). For the lower-emission scenarios of RCP60 (Fig. 2g, h), RCP45 (Fig. 2j, k), and RCP26 (Fig. 2m, n), the emergence-year distribution is qualitatively similar to that of HFD85 (Fig. 2d, e) with a later occurrence.

Zonal averages of emergence year for Pav are shown in Fig. S7a. In the case of SFD85 (black line), the emergence year occurs earlier in high latitudes and later in the subtropics, with an earlier peak over the equator. The meridional profile of emergence year for HFD85 (red) is similar to that of SFD85 (black). In the case of the lower-emission scenarios (HFD60, HFD45, and HFD26), the meridional profile of emergence year is qualitatively similar to those of SFD85 and HFD85, but with a delayed occurrence of emergence year. For P1d (Fig. S7b), the meridional profile of emergence year is qualitatively similar to that of Pav, but tends to be later. Emergence years for lower-emission scenarios tend to be delayed relative to higher-emission scenarios.

The relationship between radiative forcing (W m−2) assumed in the emission scenario and globally averaged emergence year is shown in Table 1. The larger the radiative forcing, the earlier the emergence year (Fig. S8). The emergence year of P1d (red) occurs later than that of Pav (blue). For SFD85 (arrows) and HFD85, Pav and P1d have similar emergence years.

IPCC AR6 Working Group I Atlas regions

The ToE at the grid-point scale is likely delayed due to the large natural variability relative to that at regional average scales6,27,28,29. Conversely, regional averaging reduces natural variability (noise) and enhances the anthropogenic climate-change signal. The 58 regions of the IPCC AR6 Working Group I Atlas are shown in Fig. 330.

Precipitation indices for Pav and P1d were averaged over each region in each year for the period 1950-2099, and decadal averages were calculated for the 10-year periods from 1955-1964 to 2085-2094. The estimation of natural variability and randomized sampling of decadal time series followed the same method used in grid point base. Figure 4 shows the average of emergence years av (Ye) for Pav and P1d based on 10,000 randomized time series for the 58 Atlas regions defined by Fig. 3.

Regions were classified into five types based on the relationship between the emergence years of Pav and P1d. (1) regions where Ye (Pav) is similar to Ye (P1d) in the sense that difference between Ye (Pav) and Ye (P1d) is less than 10 years, such as region 1 Greenland/Iceland; (2) regions where Ye (P1d) is later than Ye (Pav), as in region 2 North West North-America; (3) regions where Ye (P1d) is earlier than Ye (Pav) as in region 3 North East North-America; (4) regions with Ye (P1d) occurs but Ye (Pav) does not, as in region 7 North Central-America;, and (5) regions where neither Ye (Pav) nor Ye (P1d) occurs, as in region 9 Caribbean. There are no regions with Pav emergence occurs in which P1d emergence does not.

The differences Ye (P1d) - Ye (Pav) in Fig. S9 indicate that Ye (P1d) occur earlier than Ye (Pav) in 33 of all the 58 regions (red mark and red code name, 33/58 × 100 = 57%), and later in 14 regions (blue mark and blue code name, 14/58 × 100 = 24%). In the other 11 regions (black code name, 19%), there is no emergence year both for Pav and P1d.

Cumulative probability

The cumulative probability that emergence occurs by year 2050 for P1d is higher than that for Pav over most of the Atlas regions (Fig. S10). Differences of cumulative probability between Pav and P1d are illustrated in Fig. S11 where red marks and red region names means that cumulative probability of P1d is larger than that of Pav and vice versa for blue color. Cumulative probability for P1d is higher than that of Pav over 43 of the 58 regions (red mark in Fig. S11, 43/58 × 100 = 74%). The earlier appearance of intense precipitation in a future climate is highlighted more in terms of cumulative probability (Fig. S11) as compared with analysis of average emergence year av(Ye) (Fig. S9).

Dependence of emergence year on emission scenarios

The dependence of Pav emergence year on emission scenarios is illustrated in Fig. S12, where emergence occurring earlier for higher-emission scenarios than for lower emissions. This trend is not observed for all regions, given the non-linear response of the climate system to external forcing. Emergence years for P1d (Fig. S13) are qualitatively similar to those for Pav (Fig. S12), but the former are usually earlier. In region 20 (Mediterranean), there is no Pav emergence for any emission scenarios (Fig. S12b, top panel), whereas P1d emergence is identified for any scenarios (Fig. S13b, top panel). This implies that while moderate precipitation may not increase in the future, the frequency of intense precipitation will likely increase over the Mediterranean.

Climate regions in Japan

The horizontal resolution of the global climate model used here is sufficiently high that future climate change over a relatively small country such as Japan can be projected without dynamical downscaling using regional climate models. The Japan Meteorological Agency issues official one-month and seasonal forecasts for the seven subregions given in the top panel of Fig. 5. Climatological annual mean surface air temperature increases from north to south in the order northern Japan (NJ, NP), eastern Japan (EJ, EP), western Japan (EJ, EP) and Okinawa and Amami (OA). Climatological annual mean precipitation increases in the same order. In winter (December to February), the cold surge from the Siberian High brings heavy snowfall over regions on the Japan Sea side (NJ, EJ, WJ), while snowfall is relatively light on the Pacific Ocean side (NP, EP, WP) because mountainous terrain in the middle of the island blocks the cold surge.

Simulation is SFD85. a Black; Regional average of emergence year av (Ye) for Pav, red; av (Ye) for P1d. b Difference as Ye (P1d) minus Ye (Pav). Red symbol means that emergence year of P1d is earlier than Pav. Blue symbol means that emergence year of P1d is later than Pav. Closed circle shows difference exceeding the statistical significance level of 95%. c Cumulative probability (%) from 2020 to 2050 for Pav (black) and P1d (red). d Difference of cumulative probability as P1d minus Pav. Red symbol means that cumulative probability of emergence year of P1d is larger than Pav.

Ye(P1d) is earlier than Ye(Pav) in all regions except EJ (Fig. 5a, b). Figure 5c shows the cumulative probability that Ye(Pav) and Ye(P1d) occur by year 2050. The cumulative probability of Ye(P1d) is higher than that of Ye(Pav), although the difference is small for regions NP, EJ, and OA (Fig. 5d). The earlier occurrence of Ye(P1d) suggests an increase in the likelihood of natural disasters due to stronger heavy rainfall events. This provides a strong incentive for realizing a carbon-neutral society by 2050.

The dependence of Ye(Pav) in Japan on emission scenarios is shown in Fig. S14a. Emergence years for higher-emission scenarios do not always occur earlier than for lower-emission scenarios, possibly due to non-linearity originating from the large natural variability in small-scale regions. Ye(P1d) (Fig. S14b) generally occurs earlier than Ye(Pav) (Fig. S14a), and for higher-emission scenarios tends to occur earlier than for lower-emission scenarios, except for the EJ region.

Discussion

We investigated why emergence years tend to occur earlier in high latitudes than elsewhere. Figure S15a shows the meridional profiles of zonally averaged pav in the mid-20th century (1955-1964, 10 years; SPD) and at the end of the 21st century (2085-2094, 10 years; SFD85). Precipitation increases remarkably near the equator and decreases slightly over the subtropics (Fig. S15b), while also increasing at high latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, and at mid- and high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. S15b). The standard deviation of decadal average precipitation (decadal natural variability Vd) is larger in the tropics (Fig. S15c). Figure S15d shows the precipitation change (Fig. S15b) normalized by the ratio to decadal natural variability (Fig. S15c, Vd). The normalized precipitation change (Fig. S15d) is larger at high latitudes because of the small decadal natural variability there (Fig. S15c). The large positive peak in precipitation change near the equator (Fig. S15b) is reduced in the normalized change (Fig. S15d) because of the large decadal variability there (Fig. S15c). As a result, the meridional profile of normalized precipitation change (Fig. S15d) is similar to that of the emergence year (Fig. S15e). The normalized precipitation change and emergence year are strongly negatively correlated (spatial correlation coefficient -0.960). Note that the vertical axis for the emergence year in Fig. S15e is reversed. In contrast, spatial correlation coefficient between original precipitation change (Fig. S15b) and emergence year (Fig. S15e) is low (-0.509). The meridional profile of the emergence year is thus determined mainly by the signal (change; Fig. S15b) to noise (natural variability; Fig. S15c) ratio.

Whether emergence year defined as the time of emergence of anthropogenic climate change is reversible or not depends on the selection of target future period14. W examined how emergence year changes if target period is extended. Because simulation by the MRI-AGCM3.2 requires huge computer resources, we cannot extend the time integration of SFD85, HPD85. Instead, we utilized CMIP6 historical experiment (1855-2014, 160 years) and future experiment (2015-2294, 280 years) by the Meteorological Research Institute-Earth System Model version 2.0 (MRI-ESM2.0)31. We investigated how the emergence year of Pav found for the target period of 2015-2094 change if the target year is extended to 2294. We used the single original simulation and randomized time series representing natural variability is not introduced. The change of emergence year due to the extension of target period can be classified into 5 categories on a grid point base (Table S5). (1) Emergence year does not change. (2) Emergence year delays. (3) Emergence year disappears. (4) Emergence year newly appears. (5) Emergence year still does not occur. Figure S16a shows the emergence year of decadal average of Pav by MRI-ESM2.0 for the target period of 2020-2090 assuming the emission scenario Shared Socio-economic Pathways (SSP)5-8.5 which is approximately equivalent to RCP8.5. In Fig. S16b for the period 2020-2290, emergence year newly appears over many region in the tropics and mid latitudes (red). Figure S16c shows the distribution of emergence year change categories (Table S5). Emergence year does not change in most of regions (Category 1; gray). Emergence year newly appears in many regions (4; red). However, emergence year delays (2; blue) and disappears (3; green) in some regions. Figure S17 shows the area fraction of each categories. Therefore, emergence year is found to be depend on the end of target period in this case.

Methods

MRI-AGCM3.2 models

We applied the Meteorological Research Institute – Atmospheric General Circulation Model version 3.2 (MRI-AGCM3.2S) with a grid size of 20 km, ‘20-km model’, with 60 vertical levels up to a top at 0.01 hPa (about 80 km in altitude)32. The 20-km model requires huge computer resources, and large ensemble simulations are not practicable. Therefore, we also used a version with a grid spacing of 60 km (MRI-AGCM3.2H, the ‘60-km model’), which has the same vertical levels and top height as the 20-km model. The calculation speed of the 60-km model is five times larger than that of the 20-km model. We have previously published a series of articles on future precipitation changes based on the 20-km and 60-km models (Table S1).

Experimental design

Our experimental design33 followed the protocol of the High Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP)34, which is a part of the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6)35. We used a total of two models with different horizontal resolution (20 km, 60-km) for historical and future experiment. The experimental design is summarized in Table 2, where the first character in a simulation name indicates the horizontal resolution of model (S; 20-km, H; 60-km); the second character ‘P’ denotes a present-day or historical simulation, and ‘F’ denotes a future simulation; and the third character ‘D’ is the identification code for HighResMIP.

In the historical experiment, called the ‘HighResMIP Tier 1 highresSST-present34, atmospheric models were forced with observed sea surface temperature (SST) and sea ice concentration (SIC) for 65 years period from 1950 to 2014. Historical experiments were undertaken with the 20-km (simulation SPD) and 60-km (HPD) models.

The future climate simulations followed the protocol of ‘HighResMIP Tier 3 highresSST-future experiments’34, again using both the 20-km (SFD85) and 60-km (HFD85) models for 36 years period from 2015 to 2050, assuming the emission scenario of Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP)s 8.536. Future SST and SIC levels were derived from Multi-Model Ensembles (MMEs) of the CMIP6 Atmosphere-Ocean General Circulation Model (AOGCM)s34. Although the designated target period for the HighResMIP Tier 3 highresSST-future experiments was 36 years (2015-2050), we extended the time integration to year 2099 so that future simulations covered 85 years from 2015 to 2099.

To evaluate the dependence of future climate changes on emission scenarios, we conducted additional historical simulations (1950-2014) from three different initial atmospheric conditions (HPD01, HPD02, HPD03). The simulation were extended to 2099 and forced with three different emission scenarios of RCP6.0 (applied to HFD60), RCP4.5 (HFD45) and RCP2.6 (HFD26).

Given that all the historical experiments (1950-2014, 65 years) were extended to future periods (2015-2099, 85 years), our experiments can be regarded as 150-year continuous experiments conducted using high-horizontal-resolution climate models.

Reproducibility of precipitation

The ability of the MRI-AGCM3.2 model to reproduce precipitation was compared with that of other Atmospheric General Circulation Models (AGCMs) for annual average precipitation (Pav), annual maximum 5-day precipitation (P5d) and annual maximum 1-day precipitation (P1d). First, we applied 36 global atmospheric models (Table S2) that participated in CMIP6 Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (AMIP) experiments35. Second, we applied 23 higher-horizontal- resolution global atmospheric models (Table S3) registered for the HighResMIP Tier 1 highresSST-present experiment (an AMIP-type experiment)34. The target period of the simulation was 20 years from 1995 to 2014. We verified the model performance in simulating precipitation over the whole globe against the Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) Version 3.2 Daily Precipitation Data Set (GPCPDAY, Table S4)37, which contains daily global observational data with the highest-horizontal-resolution (0.5°, 56 km at the equator). The MRI-AGCM3.2S (20 km) model has the highest horizontal resolution of all 59 models (Fig. S1 and Tables S2, S3).

In terms of root mean square error (RMSE) for the global distribution of precipitation (Fig. S2), the RMSEs of MRI-AGCM3.2S (SPD, red lines) and MRI-AGCM3.2H (HPD, purple) are less than or equal to those of CMIP6 (black) and HighResMIP (blue) models. The MRI-AGCM3.2 models have similar advantage in terms of bias (Fig. S3) and spatial correlation coefficient (Fig. S4). We found that the performance of MRI-AGCM3.2 models equals or exceeds that of other models in simulating monthly precipitation over East Asia and the seasonal march of rainy season over Japan25. The advantage of the MRI-AGCM3.2 model is partly due to its higher horizontal resolution compared with physical processes implemented25.

Natural variability of models

The natural variability of AOGCMs is usually evaluated in a piControl experiment in which the model is integrated with preindustrial natural forcing for hundreds of years1,3,6,15. However, piControl experiments are not applicable to AGCMs with no ocean part. Therefore, we evaluated the natural variability of MRI-AGCM3.2 simulations using historical experiments through the following steps.

-

(1)

In historical experiments (SPD, HPD), apply linear regression analysis to annual time series of Pav and P1x for the 65-year period 1950-2014 at each grid point.

-

(2)

Using linear trend obtained in step 1, make a detrended annual time series of Pav and P1x for the 65-year period 1950-2014 at each grid point.

-

(3)

Check whether the detrended annual time series are independent in time. In the case of SPD for Pav, the area fraction of grid points with a one-year lag autocorrelation exceeding the 95% statistical confidence level is only 1.96% of the global area. Statistical significance was evaluated by Fisher’s z-transformation where correlation coefficient is converted to variable obeying the Gaussian distribution38,39.

-

(4)

Construct a synthetic time series of 500 years by the block bootstrap method with sample replacement40,41. Although time series are almost independent in time as confirmed by step 3, to conserve time and spatial structure we select two years for block length42.

-

(5)

From a synthetic time series of 500 years created by step 4, construct 50 decadal (10 years) periods. Calculate year-to-year standard deviations in each 10-year period, then average the 50 standard deviations to obtain the model climatological year-to-year natural variability Vy. Calculate the standard deviation for 50 samples of decadal average to obtain the climatological natural decadal natural variability of the model Vd.

The geographical distributions of Vy and Vd, and their ratio Vd / Vy are shown in Fig. S5 in the case of SPD for Pav. Considering one-year lag autocorrelation is almost zero everywhere as confirmed by step 3, for white noise

where vard means variance of decadal natural variability and vary means that of year-to-year natural variability. Therefore, using Eq. (1),

In fact, the ratio Vd / Vy. is generally about 0.3 with some local differences (Fig. S5c).

Time evolution of natural variability

The time evolution of natural variability in model output was evaluated as follows. The standard deviation of year-to-year variability Sy (t) for each decade (10-year period) is shown in Fig. 1b (black line), where t is time, with Sy (t) increasing towards the end of the 21st century. The standard deviation of decadal variability Sd (t) for each decade (green line in Fig. 1b) was estimated by Vd / Vy × Sy (t). In this case, ratio Vd / Vy is 0.312 at this grid point, and Sd (t) also increases towards the end of the 21st century.

Randomized time series

Massive synthetic time series were created by randomized sampling using the Monte Carlo method. Two green lines in Fig. 1a show the range of decadal natural variability estimated by one standard deviation of Sd (green line in Fig. 2b) relative to the original time series (black line in Fig. 1a). An example of randomized time series sampled within the range of decadal natural variability is shown by red line in Fig. 1a. A total of 10,000 randomized time series were generated for all simulations at each grid point with respect to precipitation indices of Pav and P1d. Emergence years were determined for all time series.

Estimated frequency distribution

Figure 1c shows the estimated frequency distribution (EDF) of emergence years evaluated from 10,000 randomized time series at a grid point in the central tropical Pacific. While the emergence year of the original time series (black line in Fig. 1a) is 2050, emergence years of the randomized time series are distributed around the average value av (Ye) of 2059.5 with a standard deviation sd (Ye) of 11.8 years. An emergence year does not always exist for all randomized time series. The existence rate E is defined as the percentage of sample time series that Ye occur. In the case shown in Fig. 1c, Ye occurs in 9968 samples, thus the existence rate E is 9968/10,000 × 100 = 99.68%.

Data availability

The MRI-AGCM3.2 and MRI-ESM2.0 data are available at the website of the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF); https://esgf.llnl.gov/. The CMIP6 AMIP and HighResMIP data are available at the website for the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) supplied by the Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison (PCMDI); https://pcmdi.llnl.gov/CMIP6/. Definitions of the IPCC AR6 Atlas regions by the locations of vertexes in longitude and latitude are given by 'IPCC-WGI-reference-regions-v4_coordinates.csv' available at https://github.com/IPCC-WG1/Atlas/tree/425d4e4f642b8a01580f0ede7cabc706f3e02f5b/reference-regions/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

Code availability

The codes to reproduce the analyses presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Hawkins, E. & Sutton, R. Time of emergence of climate signals. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L01702 (2012).

Chen, D. et al. Section 1.4.2.2 The emergence of the climate change signal. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 194–195 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Ranasinghe, R. et al. Section 12.5.2 Emergence of climatic impact-drivers across time and scenarios. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 1853–1861 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) Annex VII Glossary (page 2251), FAQ 1.2, Figure 1 (page 247). In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Power, S. Expulsion from history. Nature 511, 38–39 (2014).

Doblas-Reyes, F. J. et al. Section 10.4.3.2 Emergence of the anthropogenic signal at regional scale. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. P. et al.) 1425–1427 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Mahlstein, I., Hegerl, G. & Solomon, S. Emerging local warming signals in observational data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L21711 (2012).

Chadwick, C., Gironás, J., Vicuña, S. & Meza, F. Estimating the local time of emergence of climatic variables using an unbiased mapping of GCMs: an application in semiarid and Mediterranean Chile. J. Hydrometeorol. 20, 1635–1647 (2019).

Pohl, E., Grenier, C., Vrac, M. & Kageyama, M. Emerging climate signals in the Lena River catchment: a non-parametric statistical approach. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 2817–2839 (2020).

King, A. D. et al. The timing of anthropogenic emergence in simulated climate extremes. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 094015 (2015).

Mahlstein, I., Knutti, R., Solomon, S. & Portmann, R. W. Early onset of significant local warming in low latitude countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 6, 034009 (2011).

Samset, B. H., Fuglestvedt, J. S. & Lund, M. T. Delayed emergence of a global temperature response after emission mitigation. Nat. Commun. 11, 3261 (2020).

Mora, C. et al. The projected timing of climate departure from recent variability. Nature 502, 183–187 (2013).

Hawkins, E. et al. Uncertainties in the timing of unprecedented climates. Nature 511, E3–E5 (2014).

Kusunoki, S., Ose, T. & Hosaka, M. Emergence of unprecedented climate change in projected future precipitation. Sci. Rep. 10, 4802 (2020).

Monerie, P.-A., Sanchez-Gomez, E. & Boé, J. On the range of future Sahel precipitation projections and the selection of a sub-sample of CMIP5 models for impact studies. Clim. Dyn. 48, 2751–2770 (2017).

Dai, A. & Bloecker, C. E. Impacts of internal variability on temperature and precipitation trends in large ensemble simulations by two climate models. Clim. Dyn. 52, 289–306 (2019).

Singh, R. & AchutaRao, K. Quantifying uncertainty in twenty first century climate change over India. Clim. Dyn. 52, 3905–3928 (2019).

von Trentini, F., Leduc, M. & Ludwig, R. Assessing natural variability in RCM signals: comparison of a multi model EURO-CORDEX ensemble with a 50-member single model large ensemble. Clim. Dyn. 53, 1963–1979 (2019).

Koenigk, T. et al. On the contribution of internal climate variability to European future climate trends. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 72, 1–17 (2020).

Sarojini, B. B., Stott, P. A. & Black, E. Detection and attribution of human influence on regional precipitation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 669–675 (2016).

Lee, J.-Y. et al. Chapter 4 Future global climate: scenario-based projections and near-term information. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 553–672 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Zhang, H. & Delworth, T. L. Robustness of anthropogenically forced decadal precipitation changes projected for the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 9, 1150 (2018).

Randall, D. A. et al. Chapter 8 Climate models and their evaluation. In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Solomon, S. et al.) 589–662 (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Kusunoki, S., Nakaegawa, T. & Mizuta, R. Evaluation of precipitation simulated by the atmospheric global model MRI-AGCM3.2. J. Meteor. Soc. Jpn. 102, 285–308 (2024).

Power, S. B. & Delage, F. P. D. Setting and smashing extreme temperature records over the coming century. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 529–534 (2019).

Fischer, E. M., Beyerle, U. & Knutti, R. Robust spatially aggregated projections of climate extremes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 1033–1038 (2013).

Maraun, D. When will trends in European mean and heavy daily precipitation emerge?. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 014004 (2013).

Gutiérrez, J. M. et al. Atlas. Cross-Chapter Box Atlas.1, Figur 2 (page 1950) In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Gutiérrez, J. M. et al. Atlas.1.3.3 spatial scales and reference regions. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 1936–1938 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Yukimoto, S. et al. The Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model version 2.0, MRI-ESM2.0: description and basic evaluation of the physical component. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 97, 931–965 (2019).

Mizuta, R. et al. Climate simulations using MRI-AGCM3.2 with 20-km grid. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 90A, 233–258 (2012).

Mizuta, R. et al. Extreme precipitation in 150-year continuous simulations by 20-km and 60-km atmospheric general circulation models with dynamical downscaling over Japan by a 20-km regional climate model. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 100, 523–532 (2022).

Haarsma, R. J. et al. High Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP v1.0) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 4185–4208 (2016).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Collins, M. et al. Section 12.3 Projected changes in forcing agents, including emissions and concentrations. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 1044–1054 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Huffman, G. J., Behrangi, A., Bolvin, D. T. & Nelkin, E. J. GPCP Version 3.2 Daily Precipitation Data Set, last updated January 21, 2022. GES DISC, Greenbelt, MD. https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/GPCPDAY_3.2/summary (2022).

Storch, H. V. & Zwiers, F. W. Section 8.2.3 Making inferences about correlations. in Statistical Analysis in Climate Research, 148–149 (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Wilks, D. S. Section 5.4.2 Field significance given spatial correlation. in Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences 2nd edn, 172–175 (Academic Press, 2006).

Storch, H. V. & Zwiers, F. W. Section 5.5.3 Moving blocks bootstrap. in Statistical Analysis in Climate Research, 94 (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Wilks, D. S. Section 5.3.4 The bootstrap. in Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences 2nd edn, 166–170 (Academic Press, 2006).

McKinnon, K. A. & Deser, C. Internal variability and regional climate trends in an observational large ensemble. J. Clim. 31, 6783–6802 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the advanced studies of climate change projection (SENTAN) Grant Number JPMXD0722680734 funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. We acknowledge the international modeling groups participated to CMIP6, the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) which distributes data, and the Working Group on Coupled Modeling (WGCM) Infrastructure Panel which is coordinating and encouraging the development of the infrastructure needed to archive and deliver dataset.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. conceived the idea, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. R.M. executed the numerical experiments. M.H. reviewed and scrutinized the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kusunoki, S., Mizuta, R. & Hosaka, M. Emergence of anthropogenic precipitation changes in a future warmer climate. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 253 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01128-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01128-3