Abstract

Coastal regions are highly vulnerable to tropical cyclones (TCs), with the severity of damage often closely linked to the duration of storms over these areas. Here we show a significant increase in TC residence time along the Chinese coast, with an average rise of approximately 2.5 h per decade since the 1980s. While the overall translation speed of TCs does not show any significant trend, their travel distances within coastal zones have increased markedly, rising by about 32.9 km per decade. This trend is particularly pronounced in the southern coastal region (south of 26°N), where TC tracks exhibit a counterclockwise rotation to become more parallel to the coastline since the 1980s. A concomitant counterclockwise rotation in the steering flow near this region is also observed, which is likely driven by the northward shift of the western Pacific subtropical high. These changes in TC trajectories have also led to prolonged durations of heavy rainfall in the coastal regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

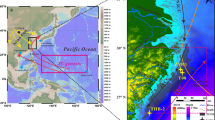

Coastal provinces in China encompass just 14% of the national territorial area1, yet they harbor over half of the total population and contribute 60% to the GDP2. These regions—characterized by low-lying terrain, high population density, and advanced economic development—are particularly vulnerable to the devastating impacts of tropical cyclones (TCs), which can trigger significant social, economic, and environmental consequences. For example, Typhoon Saola in 2023 (Fig. 1) led to the suspension of 4000 train services3, effectively halting nearly all trains in Guangdong province, China’s most economically developed region. The severity of TC-induced losses in these coastal areas is closely tied to the duration of the storms. The longer a TC lingers, the more extensive the damage is. A notable example is Typhoon In-fa in 2021 (Fig. 1), which lingered over China’s coastal areas for up to 95 h4, resulting in record-breaking precipitation and widespread devastation5,6. Given the recent trend of TCs migrating toward coastal regions7, increased attention should be paid to their duration over coastal areas.

The blue solid line on the map represents the studied Chinese coastline, extending from Fangchenggang City in the south to Dandong City in the north. This coastline is derived from GSHHG coastal data at a coarse resolution. The green shaded area outlines the coastal buffer zone along the blue solid line, with a width of 200 km. The dashed red line divides the buffer zone into southern ( ≤ 26°N) and northern ( > 26°N) regions for separate analysis. The black lines depict the tracks of two tropical cyclones (TCs), In-fa (2021) and Saola (2023), which are notable for their prolonged durations within the coastal regions.

The residence time of TCs is primarily governed by two critical factors. The first is the translation speed of TCs. Recent observational studies have suggested a global slowdown in the average translation speed of TCs since the mid-20th century8, which is expected to contribute to longer residence times. This trend is particularly pronounced along the North American coast, where reduced translation speeds have partially driven extended residence times since the mid-20th century9. However, the reliability of pre-satellite era data has been called into question, casting doubt on the robustness of the observed deceleration in TC motion10. The second factor is the travel distance of TCs. A significant turning angle in the TC track can substantially increase both the travel distance and, consequently, the residence time9. A striking example is Hurricane Harvey (2017), which exhibited a pronounced turning angle near the coast, leading to unprecedented devastation in the American coastal regions11,12.

Recent research has highlighted a slower decay of landfalling TCs due to the increase in sea-surface temperature(SST)13, potentially extending both their duration14 and travel distances15 over the entire land region. However, this slower decay attributed to enhanced moisture supply form SST increase under global warming has been challenged by the decrease in TC translation speed perpendicular to the coastline, which can also enhance moisture availability16. Moreover, the decay of landfalling TCs is not solely governed by reduced moisture supply but also by increased surface friction over land17. Consequently, slower decay can also occur if a portion of the storm remains over the smoother ocean surface for a longer period compared with the rougher land18,19.

Variations in TC movement across both coastal and inland regions of China have been widely documented. A slowdown in the motion of landfalling TCs in South China has been attributed to a deceleration of the steering flow20. However, many impactful TCs do not make landfall yet still cause significant damage (e.g., Typhoon Kong-Rey (2024)). One study reported that the slowdown of TCs near the Chinese coast led to an increase in total rainfall between 1961 and 2017 using daily precipitation data21. Nevertheless, increases in total rainfall may also result from enhanced rainfall intensity22. A major limitation of these studies is the lack of direct analysis of TC duration over coastal regions. While a slowdown in TC motion can increase duration, travel distance also plays an important role. Across mainland China, both TC duration and travel distance were reported to have increased from 1975 to 200915. However, prolonged TC duration far inland may have limited implications for the highly developed Chinese coastal regions, while TCs over adjacent coastal waters have been overlooked.

Here we show that the residence time of TCs along China’s coastal regions has increased substantially since the 1980s. While previous studies suggest a slowdown in TC motion20,21,23, our analysis finds no significant decrease in translation speed. Instead, we identify a marked increase in the coastal travel distance of TCs. Further investigation reveals that a counterclockwise rotation of the steering flow has reoriented TC tracks to move more parallel to the coastline, thereby prolonging their confinement within coastal areas. This steering flow rotation is likely driven by a northward shift of the western Pacific subtropical high. Such changes in the track characteristics have also led to substantial increases in heavy rainfall within these regions.

Results

Residence time, travel distance and translation speed

We begin by defining the Chinese coastal region (green shaded area in Fig. 1) as all locations within 200 km of the coastline (blue line in Fig.1, using GSHHG coastal data24; see Methods), hereafter referred to as the buffer zone. The range of 200 km is widely used as the threshold defining the impact range of TCs9,21,23. To quantify the residence time and travel distance of a TC, we aggregate the total duration (in hours) and distance (in kilometers) covered by each TC track within this coastal buffer zone. Annual averages are then calculated for all TCs that enter the zone within a given year. The annual average translation speed is calculated by dividing the total travel distance by the total duration hours for the year, without distinguishing between individual TCs (see Methods for details).

As shown in Fig. 2a, the residence time for the entire coastal buffer zone demonstrates a significant increase from 1980 to 2023 (p = 0.0105). Based on this linear trend, we observe that over the past 44 years, residence time has increased by 39%, rising from ~28 h in 1980 to ~39 h in 2023. Similarly, the average travel distance shows a notable increase, rising by 27% from ~533 km to ~675 km during this period (p = 0.0314, Fig. 2d). In contrast, the average translation speed displays no significant trend throughout the study period (Fig. 2g). We note that the residence time and travel distance time-series have a strong correlation of 0.72 (p < 0.01). A relatively strong, though weaker, relationship also exists between residence time and translation speed, indicated by a correlation coefficient of r = −0.52 (p < 0.01). These findings suggest that the increase in residence time is primarily associated with the increase in travel distance, rather than variations in the translation speed.

a–c Show residence time, d–f show travel distance, and g–i show translation speed. Each vertical panel corresponds to a specific region: the left panel represents the entire coastal region, the middle panel focuses on the southern region, and the right panel covers the northern region. The blue lines and dots show historical data. The orange lines show linear trends. Dashed orange lines are used in the right vertical panel because some years had no TCs entering the northern region, and this convention is similarly applied elsewhere. The values in the top-left corner of each panel indicate the rate of increase (positive value) or decrease (negative value) from 1980 to 2023. The correlation coefficients (‘r’ values) represent the relationships between residence time and travel distance, as well as between residence time and translation speed, for the corresponding regions. X axis is the year.

Given the extensive coastline of China, the dynamics such as steering flow conditions may differ between the southern and northern regions. To account for this, the coastal buffer zone is divided into southern ( ≤ 26°N) and northern ( > 26°N) segments (as indicated by the red dashed line in Fig. 1), where 26°N approximately marks the mean latitudinal position of the subtropical high ridge over the Chinese coastal region during the peak typhoon season (July to October). Supplementary Fig. 1 compares the number of TCs entering these sub-regions, showing that approximately two-thirds of TCs enter the southern coastal buffer zone, while the rest one-third reach the northern region.

Within the southern coastal buffer zone, the residence time (Fig. 2b) exhibits a more significant increase than that observed in the entire coastal buffer zone (2.8 h vs 2.5 h/decade). Over the past 44 years, the residence time in the southern region has risen sharply by 50%, rising from ~24 h to ~36 h. Despite the smaller area, the rate of increase in residence time for the southern coastal region is markedly higher than that for the entire coastal zone. The average travel distance in the southern zone also exhibits a more significant increase (Fig. 2e) although the trend is slightly lower than that for the entire coastal region ( ~ 29 km vs ~33 km km/decade), likely due to the smaller area. Over the same period, the travel distance has risen by 29%, a growth rate lower than the corresponding increase in residence time (50%). This discrepancy may be partially attributed to a modest decline in translation speed (7%, Fig. 2h). While previous study has reported a substantial reduction in the translation speed of landfalling TCs over southern China20, our findings indicate a less pronounced decrease (p = 0.3826), possibly due to the inclusion of both landfalling and non-landfalling TCs in our analysis.

In contrast, the northern region exhibits relatively weaker and statistically insignificant increments in both residence time (Fig. 2c) and travel distance (Fig. 2f). It is noteworthy that the correlation between travel distance and residence time in both sub-regions exceeds 0.8 (p < 0.01). However, an exception is observed in the northern region, where the correlation between translation speed and residence time is remarkably low (r = −0.28 and p > 0.05, Fig. 2i). The relatively low correlation is probably due to the high variance in travel distance, resulting from the diverse track patterns observed in the northern region. In this region, variations in residence time appear to be predominantly driven by changes in travel distance, which, however, exhibit a less pronounced increases (p = 0.3267) compared to the southern region.

Mechanism that controls travel distance

Several factors contribute to increased travel distances, including larger turning angles9 and slower decay of landfalling TCs14,15. To comprehensively evaluate this, we compute the annual averaged turning angles (Methods) across all three regions and found no discernible upward or downward trend over the studied period (Supplementary Fig. 2). Previous studies have suggested that SST warming could lead to a slower decay of landfalling TCs13, which might account for the increased travel distances in both the southern and northern regions. However, it does not fully explain the substantial divergence in trends between these two areas. We hypothesize that variations in the angle of incidence may have played a role in amplifying the travel distance in the southern coastal region. For example, consider two landfalling TCs—one with a track perpendicular to the coastline and another nearly parallel to it, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3. The latter, with a smaller incidence angle, would likely cover a greater travel distance and residence time within the coastal region, assuming both tracks are sufficiently long.

To investigate this, we examine trends in the incidence angle (Methods) of TCs entering the coastal regions. The incidence angle for the entire coastal buffer zone shows a weak decrease from 1980 to 2023 (p = 0.1096, Fig. 3a). In the southern region, the incidence angle shows a significant decrease during this period (p = 0.0152, Fig.3b). A reduction in the incidence angle suggests that the TC tracks are becoming more parallel to the coastline. In contrast, the incidence angle in the northern region shows a weak increase trend (p = 0.2704, Fig. 3c). To ascertain that this result is not due to the resolution of the coastline, two additional resolutions (intermediate and high) of GSHHG coastal line data are also employed. The results indicate a significant decrease in incidence angle in the southern region and a slight increase in the northern region (Supplementary Fig. 4), both of which are consistent across different resolutions and closely align with those derived from the coarse-resolution dataset.

a–c Variations in the sine of the incidence angle across three distinct regions. The calculation method is detailed in the Methods section. d Averaged steering flow during the peak typhoon season (July to October) for the first-half (1980–2001) and second-half (2002–2023) periods, using ERA5 data. Arrows represent the vector of averaged steering flow, while colors indicate the directional difference between the first and second half periods. Positive values (red) denote counterclockwise rotation. Asterisks mark rotation anomalies significant at the 90% confidence level, calculated based on the time series of rotation between the year-averaged steering flow and the time-averaged steering flow over the study period (1980–2023). The dashed black line outlines the southern coastal region. e Averaged landfall direction along the southern coastline. Solid and dashed lines in the lower-right corner represent the averaged landfall direction and steering flow, respectively. The blue solid line denotes a fitted coastline.

It is noteworthy that the correlation between travel distance and incidence angle within the entire coastal buffer zone is relatively weak (r = −0.28, p < 0.1). However, in the southern region, this correlation is more pronounced (r = −0.55, p < 0.01), suggesting a significant increase in travel distance for TCs with tracks that are more likely parallel to the coastline of South China. In contrast, the northern region has a weaker correlation (r = −0.49, p < 0.01). The modest increase in travel distance observed in the northern region (Fig. 2f) contrasts with the slight rise in incidence angle, potentially due to the slower decay of TCs.

To investigate the factors driving the decreasing incidence angle in the southern coastal region, we examine the distribution of steering flow during the peak typhoon season across two distinct periods (Fig. 3d): the first half from 1980 to 2001 (black arrows) and the second half from 2002 to 2023 (green arrows). Steering flow is defined as the deep-layer mean winds between 300 and 850 hPa25,26,27. By calculating the directed rotation angle between the two vectors (Methods), we identify a pronounced counterclockwise rotation in the steering flow near the southern coastline during the later period compared to the earlier period (illustrated by the color shading in Fig. 3d).

We further examine the average steering flow within the southern coastal region (outlined by the dashed black line in Fig. 3d). A counterclockwise rotation of ~ 22.9 degrees occurs during the second-half period compared with the first half (as illustrated by the dashed lines in the lower right corner of Fig. 3e). Consequently, around 70% of landfalling TCs along southern coastline exhibit a counterclockwise rotation in the second-half period (Fig. 3e). The average shift in landfalling angles along the southern coastline was approximately 17.5 degrees between the two periods (represented by the green and black solid lines in the lower right corner of Fig. 3e). This shift is comparable to the counterclockwise rotation of the steering flow ( ~ 22.9 degrees), supporting our hypothesis that changes in the steering flow have caused TC tracks to become more parallel to the coastline. After fitting a straight line (solid blue line in the lower right corner of Fig. 3e) to the coastline, it becomes evident that TCs in the second-half period (solid green line in the lower right corner of Fig. 3e) align more closely with the coastline compared with the first-half period (solid black line in the lower right corner of Fig. 3e), resembling the track of Typhoon Saola in 2023 (track shown in Fig. 1a). To ensure the robustness of this track rotation, we calculate the annual averaged movement direction for all TC tracks in the southern coastal region, and the results confirm a persistent counterclockwise shift, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 5. It is noteworthy that TCs tend to deviate approximately 13 degrees to the left of the steering flow (as indicated by the dashed and solid lines in the lower right corner of Fig. 3e) due to beta drift25,28.

The steering flow is primarily governed by the position of the western Pacific subtropical high (WPSH). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, the ridge of the WPSH (see Methods) during the second-half period demonstrates a northward shift compared to the first-half period. Given the anticyclonic circulation pattern of the WPSH, this northward movement inherently induces a counterclockwise rotation on its western side and a clockwise rotation on its eastern side (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Our analysis reveals a robust northward migration of the WPSH (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Methods) during the peak typhoon season, which likely drives the observed counterclockwise rotation in the steering flow over the southern coastal region. However, since the rotational effect caused by the WPSH movement is more pronounced near its ridge axis (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7a), the steering flow and the incidence angle of TCs show no significant changes in the northern coastal region, which is located farther from the WPSH ridge. The northward shift of the WPSH aligns with the recently documented and widely discussed expansion of the tropics, a phenomenon linked to a combination of natural and anthropogenic factors29,30,31,32,33.

A slower decay of landfalling TCs can also contribute to increased travel distances. The decay ratio (Methods) is closely linked to oceanic moisture supply, which is influenced not only by SST13 but also by the incidence angle16,34. A smaller incidence angle reduces the coastline-perpendicular translation speed, allowing TCs to extract more moisture from the ocean upon landfall. At the same time, slower coastline-perpendicular translation speed prolongs the duration of a portion of the storm remained over the smoother ocean.

Our analysis reveals a significant decrease in coastline-perpendicular translation speed (Methods) in the southern region (Supplementary Fig. 9a), primarily driven by a relatively weaker reduction in translation speed (Fig. 2h) and a notable decline in incidence angle (Fig. 3b). As a result, the decay ratio (Methods) in this region exhibits a significant decrease (Supplementary Fig. 9c, e), leading to longer overland travel distances as shown in Fig. 2e.

In contrast, the northern region shows a weaker increase in coastline-perpendicular translation speed (Supplementary Fig. 9b), influenced by a modest rise in both incidence angle (Fig. 3b). Despite this increase, the decay ratio in the north also experiences a slight decline (Supplementary Fig. 9d, f). The relatively modest decrease in the decay ratio in the northern coastal region may explain the limited increase in travel distance, as shown in Fig. 2f.

Rainfall analysis

The increase in TC residence time may extend durations of intense rainfall in coastal areas. In this study, TC-induced rainfall is defined as precipitation occurring within a 200 km radius of the TC center (Methods), with intense rainfall identified by a threshold of 5 mm/h. Using MERRA-2 rainfall data from 1980, we observe that the average duration of TC-induced intense rainfall within the entire coastal buffer zone shows a significant upward trend (p = 0.0029, Fig. 4a). Over the past 44 years, this linear trend reveals a striking 56% increase, raising the duration of TC-induced intense rainfall from 23.4 h to 36.6 h. Notably, the southern region exhibits an even more pronounced upward trend (p = 0.001), with an 79% increase (Fig. 4b). In contrast, the northern region shows a milder increase in TC-induced intense rainfall duration, which lacks statistical significance (p = 0.2234, Fig. 4c).

a–c show the variation in intense rainfall duration, and d–f show the variation in TC-induced precipitation. Each vertical panel corresponds to a specific region: the left panel represents the entire coastal region, the middle panel represents the southern region, and the right panel represents the northern region.

It is noteworthy that increased rainfall intensity also tends to prolong durations of intense rainfall, especially when higher thresholds are used to define intense rainfall. Across all three regions, the average TC-induced precipitation shows significant increases, all statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (Fig. 4d–f), primarily driven by heightened rainfall intensity under global warming. Thus, the increase in TC-induced intense rainfall duration in the northern region becomes more pronounced as the threshold for defining intense rainfall is raised to 10 mm/h (p = 0.12, Supplementary Fig. 10a) and 20 mm/h (p = 0.07, Supplementary Fig. 10b).

Discussion

This study identifies a significant increase in TC residence time along the Chinese coastline. A similar increase has also been reported along the U.S. East Coast9. However, the methods used to calculate residence time and the mechanisms underlying the observed changes differ considerably between the two studies. In the previous U.S. study, residence time was computed based on a 200-km-radius circle centered at a single coastal point, with the average residence time evaluated across all such points along the East Coast. The increase in residence time there was attributed to slower translation speeds and a greater turning angle. While increases in turning angle can extend TC travel distance, no significant turning angle changes have been observed in the Chinese coastal region. Instead, we find that TC tracks have become more parallel to the coastline. Many TCs that move parallel to the coastline without exhibiting large turning angles cannot be identified as having long average residence times using previous methods (e.g., Hurricane Dorian (2019)). These TCs may not extend residence time over any single city, yet they expose multiple coastal cities to the same storm, placing greater strain on shared emergency resources. This is particularly critical in China, where neighboring coastal cities often collaborate during TC events. Our method captures such hazardous TCs with high residence times over the coastal region.

Similar to the U.S., a previous study has also reported a significant slowdown of landfalling TCs in South China20. However, in this study, the slowdown in the southern coastal region appears weak. Two key differences explain this discrepancy. First, prior study considered only landfalling TCs (those crossing the Chinese coastline) with a lifetime maximum wind speed exceeding 17.2 m/s. About one-third of TCs that entered the 200-km coastal buffer zone did not make landfall and were excluded from the previous study, but are included in this analysis. Second, the horizontal range for evaluating translation speed differs. In the previous study, significant slowdowns were found far inland (minimum distance from coastline >200 km) and near eastern Taiwan Island. In contrast, about half of the coastal ocean area in that study actually showed increasing translation speed (e.g., mouth of the Pearl River Estuary).

Earlier work also found that TC residence time and travel distance over the entire Chinese mainland increased significantly between 1975 and 200915, likely due to slower decay rates and higher landfall intensity. However, these factors may not fully explain the increasing residence time and travel distance in the coastal region, especially given the absence of a robust increase in the northern part. Calculating TC residence time and travel distance only over land may be inadequate, as many TCs with relatively short land durations can still produce devastating coastal impacts. For instance, Typhoon Saola (2023) returned to the ocean shortly after landfall (Fig. 1), spending only ~18 h over land but approximately 60 h over adjacent coastal waters, while causing substantial rainfall and damage to coastal provinces35. Considering the decrease in incidence angle, TCs are more likely to return to the ocean or make multiple landfalls.

We also divide the southern coastal region into land and ocean segments. The incidence angles for the land and ocean portions are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. Results indicate a decreasing trend in both portions, but only the trend in the ocean part is statistically significant (p < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 11a), while that over land is not (p = 0.23, Supplementary Fig. 11b). We find that the number of TC centers over land is only 39% of that over the ocean (not shown).The oceanic trend closely resembles that of the overall coastal region (Fig. 3b), suggesting that the overall incidence angle decline is primarily driven by oceanic tracks. Despite the robust steering flow rotation occurring over land (Fig. 3e), its influence can extend to nearby oceanic regions due to the typical horizontal extent of TCs, which is approximately 500–1000 km.To determine whether the increasing residence time and travel distance trends in Fig. 2 are driven by land or ocean components, we perform separate analyses (Supplementary Fig. 12). The results show significant increases in the ocean portion, while changes in the land portion are not statistically significant. This suggests that the coastal trends are indeed largely due to the ocean portion. Some TCs, such as Typhoon Saola (2023), re-enter the ocean shortly after their initial landfall, significantly reducing their duration and travel distance over land. In the south coastal region, many TCs crossing the Leizhou Peninsula, briefly traversing land before returning to ocean. In such cases, the ocean segment dominates the TC duration.

In the southern region, the correlation between travel distance and incidence angle is 0.55, indicating that other factors also influence travel distance. Beyond slower decay rates, TCs migrating toward the coast, as reported in a previous study7, may also contribute to increased coastal travel distance. Additionally, the location where TCs enter the coastal zone affects the travel distance within this region.

There are deviations in rotation angles between the steering flow and TCs. As discussed above, a TC is a rotating column of air with a horizontal extent of approximately 500–1000 km and a vertical depth of 10–16 km. Prior studies often calculated the steering flow within a radial band of 5–7° latitude ( ~ 550–770 km) from the TC center20,28. Therefore, differences in the horizontal averaging range can lead to variations in estimated steering flow rotation. Vertically, this study defines the steering flow as the deep-layer mean wind between 300 and 850 hPa. In contrast, other studies often use lower-tropospheric averages21,36 (e.g., 600–850 hPa), particularly those focusing on weaker TCs. These differences in vertical layer selection introduce further uncertainty. Moreover, land surface friction37 and island topography38 can influence TC turning. Long-term changes in land surface roughness or shifts in TC track locations toward higher or lower roughness may also contribute to systematic changes in TC motion direction over time.

The observed rotation in large-scale steering flow may be linked to the global-scale expansion of the tropics, and we anticipate that similar patterns could emerge in other ocean basins in future research. Furthermore, changes in TC rotation near the coast can affect not only rainfall distribution but also other hazards such as storm surges, saltwater intrusion, and disruptions to transportation systems, including railways. These impacts warrant further investigation in future studies.

Methods

Study area data

The Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution Geography Database (GSHHG) is utilized to extract the Chinese coastline at three resolutions: crude, intermediate, and high. The southernmost point of the studied coastline is Fangchenggang City (108.1°E, 21.5°N), while the northernmost point is Dandong City (124.4°E, 39.9°N). For estuarine coastal sections extending more than 200 km inland (e.g., the Changjiang Estuary), we truncate the coastline where the river width narrows below 50 km. The coastal region is defined as a polygon encompassing all points within 200 km of the coastline, commonly referred to as the buffer zone. This buffer zone is computed using the MATLAB function bufferm with a specified width of 200 km.

TC track dataset and management process

Our analysis is based on the CMA/STI best-track dataset covering the period from 1980 to 2023. This dataset provides an annual post-season analysis of TC data, incorporating multiple sources such as satellite imagery, station observations, ship weather reports, and coastal radar observations to minimize uncertainties and enhance accuracy27,39,40. Only 6-hour track increments that penetrate the coastal buffer zone are considered in all subsequent calculations. If only a portion of a 6-hour track increment enters the coastal buffer zone, the external section is excluded (note that in such cases, the effective time duration of the track used for calculations will be less than 6 h).We restrict our analysis to TCs with sustained wind speeds exceeding 10.8 m/s, as stronger TCs are linked to greater precision in determining the center location. If a 6-hour track increment has one observation point with a maximum wind speed below 10.8 m/s and another exceeding 10.8 m/s, the endpoint with the lower wind speed is adjusted toward the other along the great-circle path on the spherical surface, assuming a linear variation in wind speed (Note that the time duration of such adjusted tracks will also be less than 6 h).To maintain consistency in the dataset, we used a 6-hour resolution for the best-track data, excluding 3-hour interval observations for landfalling TCs after 2017 and retaining only those recorded at 0, 6, 12, and 18 UTC.

Translation speed calculation

There are two methods to calculate translation speed. The first, more common approach, involves calculating the speed of each TC in a given year and then averaging these values to obtain the annual mean translation speed (note that the speed of a TC is derived from its track and duration within the coastal region). However, this method does not account for the relative contribution of each TC, as longer-duration TCs may contribute more significantly to the annual mean translation speed. In contrast, the second method divides the total travel distance by the total duration for all TCs in a given year to determine the annual mean translation speed. This approach assigns different “weights” to TCs based on their durations, ensuring that the translation speed aligns more accurately with the durations. For example, if there are two TCs in a year, and one moves very slowly with an abnormally long duration, then the average duration of the two TCs will also be long. The translation speed calculated using the second method will be slower than that from the first method, reflecting the slower average translation speed that corresponds to the longer average duration.

Turning angle calculation

The calculation of turning angle follows previous study9. It is defined as the angle between one 6-hour track increment and the next. Specifically, we compute the dot product between successive 6-hour vectors, divide it by the product of the magnitudes (modes) of the two vectors, and then convert the result into angles using the arccosine function.

TC incidence angle and coastline-perpendicular translation speed

The incidence angle is defined as the angle of intersection between the 6-hour track increment and the curved coastline. Calculating this angle is challenging due to the coastline’s curvature. To address this, we first compute the minimum distances (mindis1 and mindis2) between the coastline and the two endpoints of the 6-hour track increment. When both endpoints lie on the same side of the coastline (either both on land or both over the ocean), the sine of the incidence angle is calculated as the absolute difference between mindis1 and mindis2, divided by the length of the 6-hour track increment. If one endpoint is on land and the other is over the ocean, the sine of the incidence angle is derived from the sum of mindis1 and mindis2, divided by the length of the 6-hour track increment.

A smaller sine value indicates that the TC’s track is more parallel to the coastline. A sine value of 0 signifies that the TC’s track is entirely parallel to the coastline, while a sine value of 1 indicates that the track is perpendicular to the coastline. The coastline-perpendicular translation speed is calculated as the product of the TC’s translation speed and the sine of the incidence angle.

Directed rotation angle calculation

The rotation angle is determined based on the directed rotation angle between two vectors in the 2D plane. For example, given two vectors \({W}_{1}({u}_{1},{v}_{1})\) and \({W}_{2}({u}_{2},{v}_{2})\), which may represent the steering flows at a location during the first and second half periods, respectively, the rotation angle is calculated as: θ = atan 2(W1 × W2,W1⋅W2), where \({atan}2\) is the two-argument arctangent function, \({W}_{1}\times {W}_{2}\) is the cross product of the vectors, given by \({u}_{1}{v}_{2}-{v}_{1}{u}_{2}\), and W1⋅ \({W}_{2}\) is the dot product. A positive angle indicates a counterclockwise rotation from \({W}_{1}\) to \({W}_{2}\), meaning the steering flow in the second-half period rotates counterclockwise relative to the first-half period.

Decay parameters

This study uses two decay parameters to quantify the inland weakening of TCs. The first decay parameter,\(\tau\), is based on exponential decay model commonly used in the previous studies13,16. The TC intensity \(V\) is assumed to follow an exponential decay given by \(V\left(t\right)=V(0){e}^{-t/\tau }\),where \(t\) is the time since landfall. The landfall wind speed \(V(0)\) is estimated based on a linear interpolation between the last ocean data point before landfall and the first inland data point. A similar method is used to estimate the maximum wind speeds at 6, 12, and 18 h after landfall for TCs that have at least four inland data points. A regression analysis is then performed using the first four TC intensity values at 6-hour intervals after landfall. A larger \(\tau\) indicates a slower inland decay, and vice versa. The second decay parameter, \(K\), is derived from a quadratic formulation of turbulent drag17, yielding the solution 1/\(V\left(t\right)=1/V\left(0\right)+{Kt}\). Three different \(K\) values are obtained from the four post-landfall wind speeds at 6-hour intervals. The average of the positive \(K\) values is then calculated, as only decaying storms are considered (not including re-intensifying cases). A smaller \(K\) indicates a slower inland decay, and vice versa. Note that TCs with landfall intensity ≥10.8 m/s are considered here to increase the sample size for calculating the two decay parameters.

Movement of WPSH

The 500-hPa geopotential height is commonly used to represent the WPSH41,42,43,44,45. In this study, we characterize the domain of the WPSH using the 5880 gpm contour at 500 hPa, following previous research44,45,46. Using the ERA5 data, the averaged 5880 gpm over the two studied periods are shown in the Supplementary Fig. 6. The meridional position of the WPSH is quantified by the location of the ridge line44,47, defined as the maximum geopotential height within a closed 5880 gpm contour over the area north of 10°N and between 100°E–180°E. Results show that the ridge line shifts northward in the second period compared to the first (Supplementary Fig. 6).

As the WPSH is an anticyclonic system, to the south (north) of its ridge, prevailing easterly (westerly) winds dominate, while in the western (eastern) sector of the WPSH, southerly (northerly) winds prevail. When the ridge shifts northward, the prevailing westerly winds transition to easterly winds (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Consequently, in the western sector (dominated by southerly winds) of the WPSH, the steering flow undergoes a counterclockwise rotation, whereas in the eastern sector (dominated by northerly winds), a clockwise rotation occurs (Supplementary Fig. 7a). As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6, a white belt between 160°E and 170°E demarcates the boundary where counterclockwise rotation dominates to its left and clockwise rotation prevails to its right. This belt approximately represents the central latitude of the WPSH, separating the poleward flow on its western side from the equatorward flow on its eastern side.

To precisely determine the zonal position of the WPSH, we define a centerline line (north-south direction) that satisfy both \(v=0\) (or minimum \({|v|}\)) and \(\frac{\partial v}{\partial x} < 0\) conditions within the main body of the WPSH (a closed 5880 gpm contour over the area north of 10°N, 100°–180°E; v is the meridional component of the steering flow). As shown by the vertical dashed lines in Supplementary Fig. 6, the WPSH shifts eastward during the second-half period compared to the first-half period. Similarly, the eastward movement of the WPSH induces a counterclockwise rotation on the northern side of its ridge and a clockwise rotation on the southern side (Supplementary Fig. 7b). This mechanism accounts for the observed clockwise rotation of steering flows near the Philippines and the southern part of the South China Sea (Supplementary Fig. 6). In summary, the northward and eastward movement of the WPSH drives a counterclockwise rotation of the steering flow in its second (northwest) quadrant and a clockwise rotation in its fourth (southeast) quadrant, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6.

To determine the robust northward and eastward movement of the WPSH, we calculate the interannual variation in its position (using the 5865 gpm contour if the 5880 gpm contour is absent in a given year). Supplementary Fig. 8a shows the interannual variation in the averaged latitudes of the ridge line, indicating a northward shift, though this trend is not statistically significant (p = 0.3163). This lack of significance arises from the general shape of the WPSH, which extends from northeast to southwest (Supplementary Fig. 6). If the area of the 5880 gpm contour expands, the averaged latitudes of the ridge line may decrease due to the southwestward expansion of the WPSH. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8b, the longitudes of the western boundary exhibit a significant westward shift (p = 0.0004). This westward movement of the western boundary is driven by global warming and does not reflect the true zonal displacement of the WPSH43,48. Instead, we use the longitude of the centerline to represent zonal movement. Since the centerline can be irregular (e.g., the brown vertical line in Supplementary Fig. 6) in some years, we identify the meridian (with a 0.5° increment) that maximizes the sum of the area where \(v\ge 0\) to its west and \(v < 0\) to its east within the WPSH main body to define the centerline. In contrast to the westward movement of the western boundary (Supplementary Fig. 8b), the centerline of the WPSH shows a significant eastward shift (p = 0.0188, Supplementary Fig. 8d). The latitudes of the intersection points between the ridge line and the centerline exhibit significant increases, eliminating the influence of the broader rise in geopotential height at the pressure level under global warming. In conclusion, the northeastward movement of the WPSH is robust.

TC-induced intense rainfall duration and rainfall intensity

Rainfall data are obtained from the surface flux diagnostics of the MERRA-2 dataset at a 1-hour temporal resolution. To match this resolution, TC center positions are linearly interpolated at hourly intervals, assuming a linear change in wind speed between observation times. Only TC center points located within the coastal region and associated with sustained wind speeds exceeding 10.8 m/s are included in the analysis. TCs with a total duration of less than 1 hour in the (southern/northern) coastal region are excluded. For each hourly TC center point, we identify all rainfall grid points within a 200 km radius. If the maximum rainfall intensity among these grid points exceeds the predefined intense rainfall threshold (5 mm/h), the duration of TC-induced intense rainfall is incremented by 1 hour. The rainfall intensity associated with the TC center point is defined as the arithmetic mean of all rainfall grid points within the 200 km radius.

Statistical information

Linear trends are estimated using linear regression in MATLAB. The statistical significance of the regression slopes is assessed using a two-tailed t-test. Correlation analyses are performed using the Pearson correlation method, with significance similarly evaluated using a two-tailed t-test.

Data availability

TC best-track data is taken from the CMA/STI (https://tcdata.typhoon.org.cn/zjljsjj.html). Environmental factors are taken from ERA5 reanalysis (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels-monthly-means?tab=download). The GSHHG data were originally obtained from University of Hawai’i and NOAA(https://www.soest.hawaii.edu/pwessel/gshhg/), and a copy is also available via the GMT GitHub repository(https://github.com/GenericMappingTools/gshhg-gmt).Rainfall data is taken from MERRA-2(https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/reanalysis/merra-2/).

Code availability

All figures and results were generated by the authors using MATLAB. The buffer zone was calculated using the MATLAB function bufferm (https://ww2.mathworks.cn/help/map/ref/bufferm.html), which requires the Mapping Toolbox. The travel distance of tropical cyclones (TCs) was computed using the MATLAB function lldistkm(https://ww2.mathworks.cn/matlabcentral/fileexchange/38812-latlon-distance#version_history_tab).All other custom codes are available upon request from the first author (L.L., email: lilj@typhoon.org.cn).

References

List of Chinese Provinces by Area and Population. 2024. https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/list-of-chinese-provinces/.

Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in China in 2022, by province or region. 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1093666/china-per-capita-gross-domestic-product-gdp-by-province/.

Zheng C. Super Typhoon Saola bears down on HK, Guangdong. 2024. https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202309/01/WS64f133e6a310d2dce4bb34a9.html.

Xu B., Ye Z. & Gu W. W. Analysis damage mechanism of Shuangjiantu seawall based on marine hydrographic data monitored during the typhoon of “In-fa”. International Conference on Environmental Remote Sensing and Big Data (ERSBD); 2021 Oct 29-31; Wuhan, PEOPLES R CHINA: Spie-Int Soc Optical Engineering; 2021.

Huang, X., Chan, J. C. L., Zhan, R., Yu, Z. & Wan, R. Record-breaking rainfall accumulations in eastern China produced by Typhoon In-fa (2021). Atmosph. Sci. Lett. 24, e1153 (2023).

Yang, S. N., Chen, B. Y., Zhang, F. H. & Hu, Y. Characteristics and causes of extremely persistent heavy rainfall of tropical cyclone In-Fa (2021). Atmosphere 13, 22 (2022).

Wang, S. & Toumi, R. Recent migration of tropical cyclones toward coasts. Science 371, 514 (2021).

Kossin, J. P. A global slowdown of tropical-cyclone translation speed. Nature 558, 104 (2018).

Hall, T. M. & Kossin, J. P. Hurricane stalling along the North American coast and implications for rainfall. Npj Clim. Atmosph. Sci. 2, 17 (2019).

Moon, I. J., Kim, S. H. & Chan, J. C. L. Climate change and tropical cyclone trend. Nature 570, E3–E5 (2019).

Emanuel, K. Assessing the present and future probability of Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 12681–12684 (2017).

Van Oldenborgh, G. J. et al. Attribution of extreme rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, August 2017. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 124009 (2017).

Li, L. & Chakraborty, P. Slower decay of landfalling hurricanes in a warming world. Nature 587, 230 (2020).

Chavas, D. & Chen, J. Hurricanes last longer on land in a warming world. Nature 587, 200–201 (2020).

Chen, X., Wu, L. & Zhang, J. Increasing duration of tropical cyclones over China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L02708 (2011).

Chan, K. T. F., Zhang, K. L., Wu, Y. & Chan, J. C. L. Landfalling hurricane track modes and decay. Nature 606, E7–E11 (2022).

Phillipson, L. M. & Toumi, R. A physical interpretation of recent tropical cyclone post-landfall decay. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094105 (2021).

DeMaria, M., Knaff, J. A. & Kaplan, J. On the decay of tropical cyclone winds crossing narrow landmasses. J. Appl Meteorol. Climatol. 45, 491–499 (2006).

Rogers, R. F. & Davis, R. E. The effect of coastline curvature on the weakening of atlantic tropical cyclones. Int. J. Climatol. 13, 287–299 (1993).

Wu, K., Wang, C., Wu, L., Zhao, H. & Cao, J. Slowdown in landfalling tropical cyclone motion in south China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100428 (2022).

Lai, Y. C. et al. Greater flood risks in response to slowdown of tropical cyclones over the coast of China. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 14751–14755 (2020).

Guzman, O. & Jiang, H. Global increase in tropical cyclone rain rate. Nat. Commun. 12, 5344 (2021).

Zhang, L. J., Cheng, T. F., Lu, M. Q., Xiong, R. & Gan, J. P. Tropical cyclone stalling shifts northward and brings increasing flood risks to East Asian Coast. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, 10 (2023).

Wessel, P. & Smith, W. H. F. A global, self-consistent, hierarchical, high-resolution shoreline database. J. Geophys. Res.-Solid Earth 101, 8741–8743 (1996).

Chan, J. C. L. & Gray, W. M. Tropical cyclone movement and surrounding flow relationships. Monthly Weather Rev. 110, 1354–1374 (1982).

Klotzbach, P. J. et al. The science of william M. Gray: his contributions to the knowledge of tropical meteorology and tropical cyclones. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 98, 2311–2336 (2017).

Liu, L., Wang, Y., Zhan, R., Xu, J. & Duan, Y. Increasing destructive potential of landfalling tropical cyclones over China. J. Clim. 33, 3731–3743 (2020).

Chan, J. C. L. The physics of tropical cyclone motion. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 37, 99–128 (2005).

Lucas, C., Timbal, B. & Nguyen, H. The expanding tropics: a critical assessment of the observational and modeling studies. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.-Clim. Chang 5, 89–112 (2014).

Zhang, G., Murakami, H., Knutson, T. R., Mizuta, R. & Yoshida, K. Tropical cyclone motion in a changing climate. Sci. Adv. 6, 7 (2020).

Zhou, S. J. et al. Robust changes in global subtropical circulation under greenhouse warming. Nat. Commun. 15, 9 (2024).

Allen, R. J., Sherwood, S. C., Norris, J. R. & Zender, C. S. Recent Northern Hemisphere tropical expansion primarily driven by black carbon and tropospheric ozone. Nature 485, 350–U393 (2012).

Seidel, D. J., Fu, Q., Randel, W. J. & Reichler, T. J. Widening of the tropical belt in a changing climate. Nat. Geosci. 1, 21–24 (2008).

Chan, K. T. F., Chan, J. C. L., Zhang, K. L. & Wu, Y. Uncertainties in tropical cyclone landfall decay. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 8 (2022).

Liang, Y. et al. Fault Analysis of Guangdong Power Grid in China During 2023 Super Typhoon Saola. In 2024 9th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE). 1763-1767 (2024).

Holland, G. J. Tropical cyclone motion - a comparison of theory and observation. J. Atmos. Sci. 41, 68–75 (1984).

Au-Yeung, A. Y. M. & Chan, J. C. L. The Effect of a River Delta and Coastal Roughness Variation on a Landfalling Tropical Cyclone. J. Geophys. Res. 115, D19121 (2010).

Huang, Y.-H., Wu, C.-C. & Wang, Y. The influence of island topography on typhoon track deflection. Monthly Weather Rev. 139, 1708–1727 (2011).

Ying, M. et al. An overview of the China meteorological administration tropical cyclone database. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 31, 287–301 (2014).

Lu, X. et al. Western North Pacific tropical cyclone database created by the china meteorological administration. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 690–699 (2021).

Zhou, T. et al. Why the Western pacific subtropical high has Extended Westward since the Late 1970s. J. Clim. 22, 2199–2215 (2009).

Huang, Y. Y. & Li, X. The interdecadal variation of the Western Pacific subtropical high as measured by 500 hPa Eddy Geopotential Height. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 8, 371–375 (2015).

Wu, L. & Wang, C. Has the Western Pacific subtropical high extended westward since the Late 1970s?. J. Clim. 28, 5406–5413 (2015).

Liu, Y., Li, W., Ai, W. & Li, Q. Reconstruction and application of the monthly western pacific subtropical high indices. J. Appl. Meteorolgical Sci. 23, 414–423 (2012).

Lin, I.-I. & Chan, J. C. L. Recent decrease in typhoon destructive potential and global warming implications. Nat. Commun. 6, 7182 (2015).

Wang, Y., Hu, H., Ren, X., Yang, X.-Q. & Mao, K. Significant northward jump of the western Pacific subtropical high: The interannual variability and mechanisms. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2022JD037742 (2023).

Liu, Y., Li, W., Zuo, J. & Hu, Z.-Z. Simulation and Projection of the Western Pacific Subtropical High in CMIP5 Models. J. Meteorological Res. 28, 327–340 (2014).

Huang, Y. Y., Wang, H. J., Fan, K. & Gao, Y. Q. The western Pacific subtropical high after the 1970s: westward or eastward shift?. Clim. Dyn. 44, 2035–2047 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42306042), the National Natural Science Foundation Basic Science Center Program(42288101), the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province(2020B1111020001), and the Key Innovation Team of Tropical Meteorology, China Meteorological Administration (CMA2023ZD08).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L. conceived the idea, processed the data, generated the displays, and wrote the initial manuscript. L.L. and G.W. designed the study. J.C.L.C. co-wrote the manuscript. L.L., J.C.L.C., G.W. and Y.Z. discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Chan, J.C.L., Wang, G. et al. Increasing tropical cyclone residence time along the Chinese coastline driven by track rotation. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 306 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01178-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01178-7

This article is cited by

-

Changes in Track Characteristics of Tropical Cyclones Near Landfall: A Review

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2026)