Abstract

Organic aerosols (OA) constitute a large portion of atmospheric aerosols. The detailed sources of OA, especially precursors and formation processes of secondary OA (SOA) in megacities remain unclear, largely due to lack of molecular composition. We characterized the molecular composition of OA using online extractive electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer in winter Shanghai. Eleven OA sources were identified using Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF), combined with gas-phase organic precursors and other auxiliary measurements. We identified a plasticizer-related OA source and a primary biomass burning OA source containing likely oxidation products of biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs). SOA from photo-oxidation and aged biomass burning contributed substantially (~48%) to OA and dominated in SOA. Possible precursors of photo-oxidation SOA included aromatics and oxygenated VOCs. The nighttime oxidation of aldehydes and ketones by NO3 radicals were important sources of SOA. Aqueous SOA derived from aged biomass burning emissions also contributed markedly to OA. Our results here highlight the previously under-appreciated sources and formation processes of OA in megacities, improving our understanding of OA sources and providing support for more accurate air pollution control strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atmospheric aerosols affect global climate both directly and indirectly and are known to have a detrimental influence on human health1. Organic aerosols (OA) account for a large portion (20–90%) of aerosols2,3, which play a significant role in climate change and human health. Understanding OA sources is key to pollution control and governance. Despite continuous research efforts, the knowledge about its chemical composition and specific sources are still incomplete partly attributed to complex composition of OA from the complex and variable sources4.

OA can be categorized as primary OA (POA) and secondary OA (SOA) from the perspective of formation processes. The main sources of POA like biomass burning, cooking and transportation have been determined by different measurement techniques in previous studies5,6,7,8,9. The chemical composition of SOA is more complex because it can be formed from various processes, including the oxidation of precursors in the gas phase, aqueous/liquid phase and on the surface of aerosol particles. The specific sources of SOA remain unclear partly due to limited information of chemical composition as highly sensitive and rapid-response measurement of OA have been proven challenging.

In order to identify the sources of OA, source apportionment techniques based on chemical composition of OA is needed. Due to low time resolution (several hours to a day), source apportionment based offline techniques usually can only provide limited information, which also suffer from uncertainties from possible changes of chemical composition during storage10,11,12,13. In the decades, OA source apportionment based on online measurement has been widely adopted. Online measurements such as the aerosol mass spectrometer (AMS)14, aerosol time-of-flight mass spectrometer (ATOFMS)15, single particle laser ablation time-of flight mass spectrometer (SPLAT)16, and particle analysis by laser mass spectrometry (PALMS)17 often have time resolution of seconds to minutes, which can better follow the processes of OA and substantially enhance the number of samples to be used in source apportionment analysis. However, these online techniques of OA often use ‘hard ionization’, which breaks molecules into fragments. Molecular information is thus lost due to the fragmentation which precludes understanding the precursors and evolution of SOA. Consequently, OA sources identified by previous studies usually include types with only information of oxygenation levels or volatility degree, such as more oxidized oxygenated OA (MO-OOA) and less oxidized oxygenated OA (LO-OOA)6,7,8,18. Such information cannot provide clear view of specific sources or formation processes of OA and thus cannot be used to make control strategy.

Recently, some online or semi-online techniques with both molecular chemical information and high time resolution have been developed (e.g., extractive electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (EESI-TOF-MS)19, thermal desorption aerosol gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (TAG) system20,21, Filter Inlet for Gases and AEROsols-chemical-ionization mass spectrometer (FIGAERO-CIMS)22, chemical analysis of aerosol online proton-transfer reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometer (CHARON-PTR-TOF-MS)23 and vaporization inlet for aerosols (VIA)24). These techniques can provide chemical composition information of OA at molecular level, which have largely promoted the source apportionment of OA. FIGAERO-CIMS and TAG usually have a time resolution of 0.5–2 h. EESI CIMS can achieve a time resolution of seconds. More importantly, without heating particles, EESI-TOF-MS achieves a minimum degree of thermal decomposition and fragmentation and thus can provide the original molecular formula information of aerosols25,26,27,28,29.

A number of studies have done source apportionment using EESI-TOF-MS. Source apportionment of EESI-TOF-MS in Zurich provides more classification of OA factors than AMS both in winter and summer and shows a good agreement with the source apportionment of AMS26,28. EESI resolves biomass burning factors based on atmospheric aging (more or less aged), moving beyond simple primary/secondary classification. And organic-nitrogen-containing factor is identified as a separate factor, which cannot be identified by AMS data26. In summer of Zurich, two daytime sources are identified, one dominated by local biogenic emissions oxidation and the other representing aged aerosol from oxidation of VOCs from both anthropogenic and biogenic sources28. A nocturnal source of organic nitrates, possibly contributed by the oxidation of monoterpenes by NO3 radicals has also been identified28. In addition, EESI factors exhibited significant diurnal pattern compared to the OOA factors derived from AMS and this was proved to be consistent with changes in the physicochemical processes affecting the chemical composition and SOA formation28. Tong et al.29 reported the importance of aqueous-phase chemical processes during haze in Beijing, which are identified by the spectral characteristics of small organic acids and diacids. The results of OA source apportionment in Delhi, India show that the relative contributions of SOA and POA to total OA are very different between daytime and nighttime27. The dominance of daytime SOA, especially aromatic SOA contributing 42.4% of OA, suggests that the toxicity and health effects of daytime anthropogenic emissions need careful attention27. EESI-TOF-MS identifies an SOA factor formed from monoterpene oxidation by NO3 radicals in complex urban environments30, which is also identified as the nighttime SOA source in summertime Zurich by Stefenelli et al.28. Overall, SOA generated from the oxidation of biogenic and anthropogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs), as well as through aqueous oxidation processes, has been characterized in previous studies26,27,28,29,30,31. Chemical composition at molecular level obtained using EESI-TOF-MS offers a comprehensive perspective on the chemical composition and detailed sources of OA.

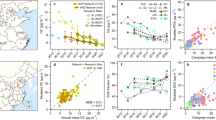

Currently, source apportionment based on online molecular composition with high time resolution is only limited to few regions, such as Zurich in Switzerland, Beijing and Nanjing in China26,28,29,30,31. The sources of OA based on composition at molecular level in China megacities, which undergo fast industrialization and have dense population are unclear. In particular, studies linking OA sources based on molecular composition with the precursors and processes of SOA in megacities are very limited. Here, we present the online measurement of OA composition at the molecular level using EESI-TOF-MS during winter 2022 in Shanghai. During winter, high aerosol concentrations are often observed in Shanghai32 and there may be specific OA sources and processes. For example, in wintertime biomass burning-related organic aerosol (OA) may contribute more significantly to total OA compared with summertime as reported by previous studies in other regions such as Zurich, Switzerland26. Moreover, key secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation pathways such as aqueous-phase chemical processes exhibit higher fraction of total OA during wintertime29. Therefore, investigating and identifying the sources and chemical composition of OA in winter in megacities are of particular significance. In this study, we separate the sources of OA using positive matrix factorization (PMF) according to the molecular composition and evolution of OA. By combining with the analysis of gas-phase organic precursors, other ancillary measurements (such as NOx, O3, NO3, meteorological parameters and so on) and backward trajectory analysis, we provide new insights into the sources of OA, particularly formation processes of SOA.

Results and discussion

Overview of campaign and OA sources based on PMF

During the campaign, PM2.5 concentration varied greatly with an average value of 31.6 ± 21.3 µg m−3. Average temperature during the campaign was 9.0 ± 5.1 °C and average relative humidity was 60 ± 15% (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

POA sources were identified based on characteristic molecular tracers and time series. SOA sources were identified by linking detailed mass spectra to their organic precursors and processes, their time series, and concomitant measurement of meteorological parameters and particle-phase and gas-phase inorganic species. The eleven-factor solution of PMF results based on OA mass spectra was chosen. The solution includes five primary sources (factors) (Biomass Burning OA (BBOA), Cigarette Smoking OA (CSOA), Cooking OA (COA), Biomass Burning Oxidation OA (BBOOA), Plasticizer-related OA (PLOA)) and six secondary sources (NO3 SOA, Photochemical SOA1, Photochemical SOA2, Aged BBOA1, Aged BBOA2, Biomass Burning Aqueous SOA (BB aqSOA)).

BBOA

The spectrum of BBOA included two significant ions at m/z 185.043 (C6H10O5) and m/z 227.049 (C8H12O6). C6H10O5 had the largest proportion (45.7%) of the total mass spectral signal in this factor and is commonly known as levoglucosan, a typical tracer of organic aerosol from biomass burning33 (Fig. 1a). The molecule C8H12O6 (6.3% of the total signal), the second-highest signal in the mass spectrum, is most likely a derivative of syringol, a prominent compound found in wood-burning smoke34. In addition, the contributions of BBOA to the intensities of the C₆H₁₀O₅ and C₈H₁₂O₆ ions reach 70.2% and 29.3%, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). These characteristics are consistent with the factors related to biomass burning reported in previous studies26,27,30,31. The signals of other compounds in BBOA factor were much lower than those of C6H10O5 and C8H12O6. In the diurnal cycle, BBOA was enhanced during 16:00–22:00, reach a peak value at 19:00 and remained low during the day (Fig. 2). Higher nighttime concentrations may reflect biomass burning for heating/cooking and a shallower nocturnal boundary layer.

CSOA

Cigarette smoking factor was featured by three prominent ions. The most significant ions were identified as C10H14N2 (nicotine, m/z 163.121), C6H10O5 (levoglucosan, m/z 185.043) and C7H11N (m/z 130.068), which contribute 24.6%, 6.7% and 3.6%, respectively to the profile (Fig. 1a). Notably, nearly 100% of the intensity of the nicotine ion is contributed by CSOA, which confirms a strong ion specificity (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). Note that the relative sensitivity of nicotine may be significantly different from that of the other ions because it is formed by protonation, a different ionization pathway from the majority of other compounds which formed adducts with Na+26. The presence of C6H10O5 (m/z 185.043) ion shows that smoking activities are often accompanied by levoglucosan emission which comes from biomass burning of tobacco, which is consistent with previous studies showing the presence of levoglucosan from cigarette smoking emissions28. The characteristics of CSOA mass spectrum were consistent with those reported in a campaign in Zurich26,28,31. CSOA was subject to the influence of air masses from the western, southern, and eastern regions of the observation site, exhibiting elevated concentrations across varying wind speeds (Supplementary Fig. 4). This phenomenon confirms that CSOA did not originate from a highly localized pollution source but rather is impacted by regional-scale transport processes.

Cooking OA

Among the various ions in Cooking OA, most ions had a high molecular weight with a m/z 200–310. The dominant peaks were m/z 251.151 (C12H20O4), m/z 237.109 (C11H18O4), m/z 293.205 (C16H30O3), m/z 321.240 (C18H34O3), m/z 265.139 (C13H22O4), m/z 291.187 (C16H28O3), m/z 307.188 (C16H28O4), and m/z 249.151 (C13H22O3) (Fig. 1a). The average H:C (with a value of 1.605) was the highest among all OA factors and the average O:C (with a value of 0.336) was the second lowest among all OA factors, (only higher than CSOA factor with a value of 0.282) (Supplementary Table S1). The dominant ions in the mass spectrum of COA were saturated or unsaturated fatty acids, which are emitted mainly from cooking activities35 and have been recognized as tracers of cooking in previous studies26,27,30. Oleic acid (m/z 305.245 C18H34O2) is one of the most common products of cooking activities in China according to cooking habit36. C6H10O5 also contributed markedly (1.8%) in this factor. The relatively high sensitivity of C6H10O5 in EESI-TOF-MS and the emission of some cooking activities may account for this phenomenon37. The time series of oleic acid and other tracers of cooking such as C12H20O4 and C16H30O3 all had a good agreement with that of COA factor (R = 0.74, 0.77 and 0.76, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 5). Furthermore, the majority of signals from cooking-related tracers such as C12H18O3, C12H20O3, C20H36O3 and C13H22O4 are attributed to the COA factor (>40%), which reflects a high level of ion specificity (Supplementary Fig. 3). Over 95% of the intensity of C₁₂H₁₈O₃, a characteristic tracer for cooking organic aerosol is contributed by COA factor. This result indicates that COA is indeed dominated by cooking-emitted organic aerosols which is unlikely to be significantly affected by traffic emissions,which are sometimes difficult to distinguish from COA. In addition, three peaks in the diurnal cycle (at 7:00-9:00 LT, 12:00-13:00 LT and 18:00-19:00 LT, respectively) were similar with COA factors resolved from AMS-PMF analysis observed in Shanghai and COA molecular tracers measured by TAG-GC, which shows a higher peak at dinnertime (Fig. 2)38.

It is noted that some C9 and C10 molecules also contributed substantially to this factor, which was different from the COA MS profile from previous studies in Zurich26,28. The ions of m/z 223.094 (C10H16O4), m/z 209.078 (C9H14O4), m/z 225.110 (C10H18O4), m/z 211.094 (C9H16O4), m/z 195.093 (C8H12O4) contributed 7.6% to the spectrum, which are recognized as the oxidation products of monoterpene in a number of studies39,40,41. This could be explained by the following possible reasons: (1) We obtained an aged source of COA containing some oxidation products of monoterpenes, which are emitted from cooking activities. Previous studies show that monoterpenes can be emitted by cooking vegetables, which has a large potential contribution for SOA and is a key precursor of cooking aerosols based on Chinese domestic and restaurant cooking42,43. (2) These C9 and C10 molecules were the oxidation products of unsaturated aliphatic hydrocarbons which are emitted by cooking activities. (3) This was a mixing factor that contains cooking emissions and biogenic OA due to the limitations of PMF algorithm. Despite being characteristic tracers of biogenic OA, some of these C9 and C10 molecules may have similar temporal behaviors with cooking OA. Moreover, the influence of boundary layer dynamics on the diurnal patterns of all factors may lead to collinearity between individual unrelated factors to some extent27,31.

BBOOA

As shown in Fig. 1a, in this factor, some tracers of monoterpene-derived SOA were observed at m/z 209.078 (C9H14O4), m/z 195.063 (C8H12O4), m/z 211.058 (C8H12O5), m/z 223.094 (C10H16O4) etc.39,40. BBOOA showed good correlation with products of monoterpene oxidation, e.g., C9H14O5 (R = 0.69, Supplementary Fig. 6). Interestingly, BBOOA also showed moderate correlation with levoglucosan (R = 0.59) and BBOA (R = 0.52), which indicates that BBOOA had similar sources with BBOA, i.e., related to the primary biomass burning emission. This finding is also confirmed by the moderate correlation with BC and CO, with respective R of 0.56 and 0.56 (Fig. 5). In the correlation plot of BBOOA with C9H14O5 (Supplementary Fig. 6), there were different slopes, which suggests that (1) This factor contained C9H14O5 and C9H14O4 from different sources, some of which were directly emitted from biomass burning and the other may be from the oxidation of monoterpenes. The difference in diurnal pattern between BBOOA and BBOA also supports this inference. (2) The relative distribution of various compounds in OA and thus ratio of C9H14O5 to total OA produced by biomass burning may vary from fuel type and combustion mode44,45.

We would like to note that the weak correlations between BBOOA and α-pinene/β-pinene (with correlation coefficients of −0.047 and 0.00, respectively), together with their distinct diurnal variations and low biogenic VOC emissions during winter in Shanghai, suggest that BBOOA is unlikely from gas-phase oxidation processes of biogenic VOCs (Supplementary Fig. 7). Moreover, BBOOA showed weak correlation with tracers of volatile chemical products such as D5 siloxane, dichlorobenzene, and limonene, as indicated by low correlation coefficients (R = 0.07, 0.20, and 0.11, respectively). It is collectively suggested that BBOOA is not influenced by volatile chemical products.

PLOA

A unique molecule C22H42O4 was prominent and ~54% of this ion signal can be explained by PLOA (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 3). This molecule is likely dioctyl adipate (DOA), which has been reported in previous studies as component of vehicle exhaust from diesel engines using biodiesel fuel or emissions from tire wear46,47. The episodic feature of this factor suggests that it could be dominated by some events. This factor was enhanced during 3:00–6:00 and 18:00–20:00 at night, when there are large diesel vehicles driving in the early morning due to local traffic restrictions of Shanghai and general evening rush hour traffic emissions (Fig. 2). In addition, this factor was in good agreement with the time series of C24H38O4 (bis (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, DEHP)) and C16H22O4 (dibutyl phthalate), which are both well-known phthalate esters (PAEs) (Supplementary Fig. 8)48,49,50. PLOA was evidently subject to the influence of air masses from the western regions of the observation site (Supplementary Fig. 4). The higher estimated concentration of the source at both low and high wind speeds indicates that PLOA was dominated by local emission and regional pollution transport. PLOA had also been found in Nanjing, another representative observation site in the Yangtze River Delta region in China30. However, there are some differences between the dominant compounds except for C24H38O4 of the two plasticizer-related factors in the mass spectra of this study and the study by Ge et al.30, which suggests the disparity of PLOA composition in different cities. This factor further proves that plasticizer emission has a potential significant contribution to OA in Yangtze River Delta region of China and it deserves more investigation considering its impact on human health.

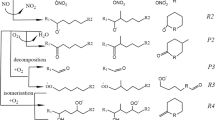

NO3 SOA

In the mass spectrum of this factor, CxHyOzN1-2 compounds were dominant. C10H17NO8 (m/z 302.08), C14H17NO4 (m/z 286.10), C10H15NO6 (m/z 268.08), C16H11NO2 (m/z 272.07) C18H33NO6 (m/z 382.22) contributed 2.0%, 1.1%, 1.1%, 1.0%, 0.9% to total MS signal in this factor, respectively. These identified ions were likely to be organic nitrates (Fig. 3a). The most specific components of NO₃ SOA are mostly organic nitrates. For the five most specific species, C₁₈H₃₃NO₆ (m/z 382.22), C₁₀H₁₇NO₈ (m/z 302.08), C₂₂H₂₁NO₃ (m/z 370.14), C₁₃H₁₅NO₄ (m/z 272.09), and C₂₂H₃₁NO₅ (m/z 412.21), their signals from the NO₃ SOA factor account for 62.2%, 53.0%, 49.45%, 45.7%, and 41.0% of their total signals, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). NO3 SOA factor exhibited a strong diurnal cycle, with a daily maximum at ~06:00 LT, minimum at ~10:00 LT (Fig. 4). It had a moderate correlation (R = 0.48) with NO3 radical during night time. It also had a high correlation with gas-phase C10H20O, C10H16O, C8H16O, C7H14O, C8H14O2 and C9H16O (R is 0.78, 0.78, 0.76, 0.72, 0.71, 0.70, respectively), which are likely saturated or unsaturated aldehydes and ketones (Supplementary Fig. 9). In addition, the averaged N:C in this factor (0.047) was the highest except for CSOA which was heavily weighted by nicotine (Supplementary Table S1). This higher N/C was similar to an OA source (NSOAEESI) observed in Zurich26. The precursors of nitrogen-containing SOA factor (NSOAEESI) in wintertime Zurich are identified as being unclear25, while NO3 SOA here was possibly attributed to the oxidation of aldehydes and ketones with NO3 radicals at nighttime.

Photochemical SOA

Two types of photochemical SOA were identified, Photochemical SOA1 and Photochemical SOA2. In the mass spectrum of Photochemical SOA1, C6-24 molecules accounted for a significant proportion, while C6-12 molecules dominated in the mass spectrum of Photochemical SOA2 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Photochemical SOA1 contained higher fractions of molecules with oxygen number of 2 and 3 than Photochemical SOA2 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Interestingly, the most specific components of Photochemical SOA1 were mostly organic nitrates such as C₁₈H₂₇NO₄ (m/z 344.18), C₂₃H₃₇NO₃ (m/z 398.27), C₁₉H₂₇NO₄ (m/z 356.18), and C₂₀H₂₇NO₃ (m/z 352.19) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The most specific components of Photochemical SOA2 were dominated by CHO compounds such as C₁₁H₁₈O₅ (m/z 253.10) and C₁₂H₁₂O₅ (m/z 259.06), 77% of the intensity of which was attributed to Photochemical SOA2 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Both factors showed an enhancement during daytime, consistent with the diurnal variation of odd oxygen (Ox = O3 + NO2) (R = 0.46, 0.49, respectively) (Fig. 5). Photochemical SOA1 was only enhanced during the daytime, and the intensity during night was lower than that of Photochemical SOA2, showing a stronger diurnal variation than Photochemical SOA2 (Fig. 4). Photochemical SOA1 had the highest DBE (with a value of 4.3) among all OA factors and it had good correlation with some gas-phase aromatics (e.g., R = 0.67 and 0.70 with the oxidation rate of toluene and cresol, respectively), suggesting that aromatics may be the major precursors (Supplementary Table S1, Fig. 5). Moreover, Photochemical SOA1 also correlated well with some oxygenated VOCs e.g., ketones (e.g., R = 0.80 with C4H8O (butyraldehyde or tetrahydrofuran)) and esters (e.g., R = 0.71 with C6H12O2 (butyl acetate)) (Supplementary Fig. 11). As these oxygenated VOCs are possibly oxidation products of VOCs or from direct emissions e.g., from volatile chemicals products (VCPs), this correlation further suggests that the precursors of Photochemical SOA1 were mainly from traffic emissions and/or VCPs. Traffic emissions and usage of VCPs have been shown to be significant sources of VOCs in urban areas51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61.

Pearson correlation coefficients between the resolved factors and inorganic species, oxidants, meteorological parameters, volatile organic compounds, their oxidation rate proxy, and particle-phase tracers. The oxidation rate proxy is defined as the product of precursor VOCs concentration and Ox (where Ox = O3 + NO2).

Photochemical SOA2 correlated best with inorganic components among all the OA factors, with R of 0.72 and 0.47 for nitrate and sulfate, respectively (Fig. 5). Aqueous SOA usually correlates with sulfate and/or nitrate, which has been reported in many studies18,29,62. Photochemical SOA2 correlated well with some oxygenated VOCs e.g., ketones (e.g., R = 0.64 with C4H8O (butyraldehyde or tetrahydrofuran)) and esters (e.g., R = 0.80 with C2H6O4 (3-hexenoic acid or alkenoate ester)). The higher O:C (0.545) of Photochemical SOA2 than that of Photochemical SOA1 (0.330, Supplementary Table S1) were consistent with that reported in the winter of Beijing which is attributed to aqueous photochemical OA formation63,64. The aqueous-phase processing and photochemical oxidation can have a joint influence on the enhancement of aqueous SOA formation, which often has a high oxidation degree63,65. Overall, Photochemical SOA1 and Photochemical SOA2 formation were attributed to photochemical oxidation and aqueous-phase processing in photochemical oxidation, respectively.

Aged BBOA

In the spectra of both Aged BBOA factors (Fig. 3a), dominant compounds were C8H12O6 (m/z 227.052), C6H10O5 (m/z 185.043), C7H10O5 (m/z 197.042). Aged BBOA1 had the highest O:C (0.582) of all factors except for the fresh biomass burning factor (BBOA), which was heavily influenced by C6H10O5 (Supplementary Table S1). Aged BBOA1 was mainly composed of C6, C8, C9 molecules and showed a higher contribution fraction of C8HyO4 and C9HyO4 compounds, while Aged BBOA2 was mainly composed of C8, C9, C10 components (Supplementary Fig. 10). In addition, the intensity of high carbon number molecules (Cn>14) of Aged BBOA2 exhibited higher intensity than those of Aged BBOA1 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Aged BBOA1 was obviously enhanced during the day from 8:00 LT to 19:00 LT while Aged BBOA2 had a much flatter diurnal variation, with only slightly higher values from 11:00 LT to 20:00 LT (Fig. 4). Aged BBOA1 correlated weakly with most possible organic precursors (Fig. 5), suggesting that it was not from local photochemical oxidation processes in the gas-phase. The dominant compounds (C8H12O6, C6H10O5, C7H10O5) in the spectra of both factors were consistent with the more aged biomass burning OA factor derived in the winter in Zurich26 and dominant compound (C6H10O5) of aged biomass burning emissions retrieved from a smog chamber experiment66. Furthermore, aged BBOA1 contributed the vast majority (>87%) of the intensity of C₈H₆O₄ (m/z 186.037) while aged BBOA2 contributed over 49% of the intensity of C₅H₉NO₅ (m/z 189.016). C₈H₆O₄ and C₅H₉NO₅ may serve as tracers for biomass burning, given that both were allocated to factors associated with aged biomass burning in organic aerosol (OA) source apportionment analyses conducted in Switzerland26,31. This consistency validates that both Aged BBOA factors were dominated by the atmospheric aging of biomass burning aerosols. Aged BBOA2 had a higher contribution of CHON compounds (24.5% vs. 11.4%) and also a lower H:C (1.44 vs. 1.48) and higher DBE (3.78 vs. 3.38) than Aged BBOA1 (Supplementary Table S1). The higher fraction of CHON compounds in Aged BBOA2 suggests that Aged BBOA2 may undergo the aging process of biomass burning associated with NO3 radicals at night67,68. The higher DBE suggests that the precursors of Aged BBOA2 could be less aged aromatics as aromatics usually have a high DBE34,44,67,68,69.

Aged BBOA1 and Aged BBOA2 were enhanced relative to each other during different time periods of the campaign. There were significant differences in meteorological conditions during the relatively dominant periods of these two factors. Supplementary Fig. 12 shows the distribution of meteorological parameters in the periods relatively dominated by these two factors. Periods with enhanced Aged BBOA1 were featured by lower temperature (5.73 ± 3.55 °C) and higher relative humidity (67 ± 10%), while averaged temperature and relative humidity during the periods dominated by Aged BBOA2 were 9.72 ± 4.57 °C and 60 ± 15%, respectively. Wind analysis performed by Nonparametric Wind Regression (NWR) suggests that the two factors were dominated by air masses from different geographic regions (Fig. 6). Aged BBOA1 was evidently enhanced when the site was influenced by the north (N, NW and NE) wind and it was enhanced as wind speed rose (Fig. 6a). High intensity of Aged BBOA2 were observed under all wind directions and wind speeds. The intensity of Aged BBOA2 showed a slight upward trend in accordance with the rise of wind speed only in the southeast (SE) direction (Fig. 6b). The flat time trend of Aged BBOA 2 and its polar plot may reflect the influence of transport from diverse sources (Figs. 4 and 6b, d). Concentration-Weighted Trajectory (CWT) results show that Aged BBOA1 was obviously affected by the transport of the northern air mass while Aged BBOA2 was attributed to aged BBOA contributed by air mass containing aged biomass burning aerosols and mixing OA compounds from several regions especially local YRD region and the southeastern sea of the site (Fig. 6c, d).

BB aqSOA

In the mass spectrum of BB aqSOA, C9H14O4, C8H12O4, C8H12O5, C7H12O4, C8H12O6 and C7H10O4 were the primary contributors (Fig. 3a). In terms of molecular composition, molecules with carbon numbers of 7–10 and CxHyO4-6 compounds accounted for the most fractions (Supplementary Fig. 10). The most specific components of BB aqSOA were C₅H₁₁NO₆ and C₆H₁₀O₄, 60.7% and 45.8% intensity of which were contributed by BB aqSOA (Supplementary Fig. 3). The moderate correlation with BC and C6H10O5 (R = 0.51, 0.56, respectively) indicates that BB aqSOA is related to the primary source of biomass burning (Fig. 5). Moreover, some aqueous-phase products of syringol and guaiacol oxidation such as C8H12O4 (m/z 195.063), C7H12O4 (m/z 183.063), C7H10O4 (m/z 181.047)70,71 were observed and accounted for a remarkable portion (9.8%) of the mass spectrum. These compounds have also been reported in the biomass burning-related activities samples and are associated with aqueous processes70,71. Furthermore, BB aqSOA correlated strongly with these molecules (R = 0.86, 0.83 for C7H12O4, C7H10O4, respectively) throughout the entire campaign. C9 species were likely derived from monoterpenes, which have been observed in biomass burning emissions72,73. The N:C (0.036) of BB aqSOA was only lower than CSOA and NO3 SOA and the O:C (0.51) showed a high degree of oxygenation of this source (Supplementary Table S1).

The most remarkable characteristic was that BB aqSOA had the highest correlation (R = 0.74) with nitrate among all OA factors (Fig. 5). A number of previous studies have reported high correlation of aqSOA with nitrate when nitrate is the dominant inorganic component29,74,75. The high correlation with nitrate is indicative of aqueous-phase chemistry as nitrate contributed most of the aerosol liquid water content in these studies. The pattern of enhanced fraction of BB aqSOA to all OA at RH = 50–80% (Fig. 7) was consistent with the dependence of aqSOA on RH observed in previous study in Beijing63. The diurnal variations of the factor showed two peaks, with a slightly high value in the afternoon and a continuously high value from 21:00 LT at night to 7:00 LT the next day (Fig. 4). This suggests that BB aqSOA may be contributed by daytime photochemical aqueous-phase oxidation and nighttime aqueous-phase processes. Aqueous processing of BB emissions has been reported to play a significant role in the SOA formation76.

Relative contributions of different OA sources

The averaged relative contributions of all factors to total OA signals during the campaign are showed in Fig. 8. Overall, two Photochemical factors and two Aged BBOA factors emerged as the most prominent fractions, constituting 25.1% and 23% of the total OA signals, respectively. Other sources, such as Aqueous Aged BBOA (9.7%) and BBOOA (9.1%) also contributed significantly, while PLOA had the lowest proportion at 4.4% (Fig. 8b). The contribution of COA to total OA signals was 7.3%, similar to the contribution of cooking in Zurich (7–12%) and Beijing (5.5–5.7%)26,29.

a Time series of all PMF factors with their relative contributions to total OA signals. b Averaged relative contributions of all factors to total OA signals derived directly by PMF during the campaign. c Averaged relative contributions of all factors to total OA signals corrected using factor-dependent sensitivity during the campaign.

Assuming that all OA factors have the same sensitivity in EESI-TOF-MS, the fraction in total OA signals would be equivalent to the fraction in total OA mass. Nevertheless, different OA factors may have different sensitivity factors. For example, Tong et al.77 reported that primary BB and CSOA have higher sensitivity than other OA factors. Therefore, the signals of all factors in this study were corrected according to the factor-dependent sensitivity provided in Tong et al.77, which is described in details in Supplementary Note 1. The corrected contributions to OA signals after correction are shown in Fig. 8c. More details of the correction are in the Supplementary Note 1. The corrected contributions to OA signals are expected to be proportional to the fractions in OA mass with the uncertainty of the method. After correction, the general pattern of different OA did not change significantly (Fig. 8c). The fraction of POA slightly decreased (from 35.6% to 31.6%) while the fraction of SOA slightly increased (64.4% to 68.4%) (Fig. 8c). Photochemical SOA factors and Aged BBOA factors remained the most prominent fractions, constituting 30.5% and 17.8% of the total OA. Although the fractions of BBOA and CSOA decreased while the fractions of Photochemical SOA1, NO3 SOA, and COA increased (Fig. 8c).

Three episodes (E1–E3) with high pollution were observed during the entire campaign. BBOA, BBOOA, PM2.5 and OC were enhanced significantly during these three episodes (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Fig. 13a). The contribution of POA to total OA signals also increased in accordance with the increase of total OA concentration during these three episodes (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Fig. 1b). Back-trajectories and cluster by HYSPLIT model during these pollution periods showed the different geographic sources of aerosols (Supplementary Fig. 14). The air mass from South Jiangsu and Northeast of China contributed 87.5% and 12.5%, respectively from Feb. 14th 12:00-Feb. 15th 12:00 (E1). During Feb. 28th 18:00-Mar. 2nd 6:00 (E2), aerosols were transported mainly from three source regions. The airmass of YRD contributed 62% while the Northeast of China contributed 28%. In addition, 10.34% aerosol were from sea on the way through Jiangsu. The airmass from North Zhejiang were the main source of aerosol during Mar. 4th 8:00-Mar. 5th 8:00 (E3). Overall, the BB-related OA in Shanghai during the three pollution episodes were largely influenced by airmass transported from Northern China and other regions in YRD.

Implications

In this study, molecular composition of OA was characterized using online EESI-TOF-MS in Shanghai in 2022 winter, to investigate the sources and formation of OA. More than 1500 organic species were detected. Eleven sources are sorted using PMF analysis of the time series of these species. Combining the gas-phase organic composition, characteristic molecular tracers, oxidants and other auxiliary measurements, the sources of OA were identified, including five POA factors and six SOA factors.

POA factors contained biomass burning OA (BBOA), cigarette-smoking OA (CSOA), cooking-related OA (COA), oxidized OA from biomass burning (BBOOA), and plasticizer-related OA (PLOA). CSOA and COA were featured with a high contribution of nicotine and long-chain fatty acids, respectively. BBOOA can be oxidation products directly emitted from biomass burning from biogenic vapors such as monoterpenes. PLOA showed a number of typical phthalate esters (PAEs). CSOA and PLOA may have significant implications on human heath due to potential toxicity in megacities characterized by dense populations and highly active industrial and daily-life activities. Within these POA sources, COA contributed a major fraction while PLOA, CSOA and BBOOA were under-appreciated OA sources in previous studies.

SOA factors contained one nighttime NO3 oxidation SOA (NO3 SOA), two SOA sources related to photochemical oxidation (Photochemical SOAs), two aged biomass burning OA (Aged BBOAs) and one aqueous SOA (BB aqSOA). We found that the oxidation of aldehydes and ketones by nocturnal NO₃ radicals was a potentially important source of OA. The photochemical oxidation of aromatics and oxygenated VOCs was identified as a critical contributor to OA, indicating that anthropogenic emissions serve as significant precursors. The aqueous SOA was found to be derived from aged biomass burning and contributed markedly to the total OA, highlighting the significance of aqueous processes in aerosols during winter in the YRD region. Within SOA, two Photochemical SOA sources and two Aged BBOA sources contribute majority of SOA signals and 48% of total OA signals. This study provided some new insight into the SOA sources and formation processes, such as the significant roles of the reaction of aldehydes and ketones with NO3 radicals, of the photo-oxidation of aromatics and oxygenated VOCs and of the aqueous processing of biomass burning emission in SOA formation. The detailed mechanisms of these SOA formation identified in this study such as NO3 SOA and Aqueous Aged BBOA still necessitate further laboratory investigation.

Using EESI-TOF-MS, temporal evolution of a large number of molecules can be traced and then integrated with PMF to precisely resolve the sources of OA. Such continuous, online molecular composition enable identification of hitherto unrecognized or underappreciated sources of OA in megacities compared with offline techniques or online analytical techniques without molecular information. It also enables identification of its gas-phase or particle-phase precursors, and understanding potential chemical mechanisms of SOA formation in the complex atmosphere. Such information regarding sources is crucial for formulating effective air quality strategies, as it allows policy makers to prioritize interventions targeting the main sources of air pollution. Nevertheless, this technique has limitations. On one hand, the relatively low detection sensitivity of EESI towards hydrocarbons may result in an underestimation in the quantification of primary traffic emissions. On the other hand, due to the differences in sensitivity of different OA factors, the relative contributions of various OA sources in this study may be subject to uncertainties. Consequently, further quantifying the relative response factors of various of OA factors out of EESI-TOF-MS by combining with AMS will improve the accuracy of OA source apportionment.

Methods

Measurement campaign

The campaign was conducted from Feb. 10th to Mar. 12th, 2022 at the observatory on the roof of a 7-story building in Fudan University Jiangwan Campus (31.34°N, 121.51°E), at an altitude of ~27 m above the ground. This observatory is located in an urban area in northeastern Shanghai, China and is a representative observatory for urban atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Instrumentation

A EESI-TOF-MS sampled through a stainless-steel tube through a PM2.5 impactor. The details of the EESI-TOF-MS have been described in previous studies19,78. In brief, EESI-TOF-MS consists of an EESI inlet coupled to a high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometer with atmospheric pressure interface (APi-TOF, Tofwerk, Thun, Switzerland)19. For particle measurements, the instrument automatically alternates between two modes: aerosol sampling and particle-filter (AQ, Parker) sampling (as background) and signal difference between two modes corresponds to the signal of particles. The atmospheric air flow passes through a charcoal denuder in a stainless-steel tube before particles are extracted by charged droplets. The denuder removes volatile organics and sticky gases, reducing the instrument’s background and detection limits. After the denuder, particles in laminar flow collide with electrospray droplets from working solution (100 ppm NaI in a 1:1 water (MilliQ): acetonitrile (UHPLC-MS grade, Sigma-Aldrich) mixture) and components in particles are extracted. The heater capillary vaporizes these mixed droplets in ~1 ms. Ions from charged-droplet Coulomb explosion enter the APi-TOF for analysis, as detailed before19,79.

EESI-TOF-MS does not rely on thermal desorption or hard ionization, and does not separate the collection from analysis stage, which minimize fragmentation or decomposition of analytes, enabling on-line, near-molecular (i.e., molecular formula) OA measurements. The performance of EESI-TOF-MS has been tested and evaluated in previous studies, including laboratory measurements, ground-based measurements, and measurements aboard research aircraft31,78,80,81.

EESI-TOF-MS was calibrated using levoglucosan aerosols (Supplementary Note 2). A constant output atomizer (Model 3076, TSI, USA) was used to generate a certain concentration of levoglucosan particles, which were dried using a Nafion drier (MD-700, Perma Pure, USA). Levoglucosan aerosols were simultaneously measured by the EESI-TOF-MS and a scanning mobility particle size analyzer (SMPS, Model 3936, TSI, USA), aerosol condensation particle counter (CPC, model 3789, TSI, USA), which provided the mass concentration of levoglucosan aerosols.

During the campaign, VOCs were measured using a Vocus proton transfer reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PTR-TOF-MS, Tofwerk AG, Switzerland, and Aerodyne Research, USA). The pressure in the FIMR of the Vocus PTR-TOF-MS was set to 2 mbar, and the Vocus front voltage and back voltage were set to 600 V and 15 V, respectively, which ensured a good sensitivity and low fragmentation of ions. Details of the instrument has been reported previously82. A gas chromatograph electronic-ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (GC (Aerodyne Research, Inc., USA), EI-TOF-MS (Tofwerk AG., Switzerland)) and Vocus PTR-TOF instruments were combined to obtain high temporal resolution information and structural information of VOCs in the atmosphere. This system has been reported in previous studies83. During the first 30 minutes of each sampling period, the Vocus PTR-TOF directly measured ambient samples and the GC extracted a 500 s ambient sample flow at a flow rate of 155 sccm for storage. In the next 30 min, GC separated the helium gas containing VOCs into the Vocus PTR-TOF for measurement. Organic carbon and elemental carbon (OC, EC) mass concentrations were measured hourly by a semi-continuous OC/EC analyzer (RT-4 model, Sunset Laboratory Inc., USA). In thermal-optical analysis, the optical component corrects for light-absorbing carbon generated during the thermal decomposition of OC. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health/Thermo Optical Transmission (NIOSH/TOT) method was used in this campaign. More detailed information about the OC/EC analyzer can be found in previous studies84,85,86,87. NO3 radicals were measured using differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS) systems equipped with LED (LED-DOAS)88. Based on the signal-to-noise ratio at a given optical path length and integration time, the detection limit (2σ) is ~7 pptv for NO389.

Other on-site long-term measurements includes environmental meteorological data, such as temperature, relative humidity (RH), solar radiation, wind speed and wind direction. Trace gases including ozone, nitrogen oxide, carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide were measured by corresponding gas analyzer (Model 49i, 42i, 48i and 43i, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Positive matrix factorization

Source apportionment was performed on the EESI-TOF-MS data using PMF Evaluation Tool (PET) in Igor Pro (Version 9, WaveMetrics, Inc., Portland, Oregon) to evaluate PMF outputs and related statistics90. A large number of studies have successfully applied PMF to environmental and synthetic data sets to explore the sources of particulate matter and organic aerosols91.

PMF represents the input data matrix as a linear combination of characteristic factor profiles and their time-dependent contributions, which can be expressed in matrix notation as

The measured X is an m × n matrix, representing m measurements of n species. G and F are m × p and p × n matrices, respectively, where p is the number of factors contained in a given model solution and is selected by combing the mathematical criteria and physical implications90.

EESI-TOF-MS collected data at 1-min resolution, alternating between ambient sampling (8 min) and background modes (7 min). The measurement uncertainty matrix σdiff was calculated by Eq. (2), consistent with previous studies26,27,29,30.

Signals of species from high resolution peak fitting were used as input data of PMF, which were further screened by the following principles and ~850 ions were chosen to input for PMF.

-

a.

The ratio of the difference between the sample signal and the background signal (particle-filter mode) to the background signal was higher than 0.1.

-

b.

The ions with a SNR lower than 0.2 were removed, while ions with a SNR between 0.2 and 2 were down weighted by a factor of 290.

When running PMF, the number of factors was varied for 1–20 according to previous known OA sources in megacities26,28,29,30,90. The rotation was set to −0.4–0.4 according to references8,90. As a result, a series of solutions with different number of factors and rotation were obtained. Eleven factor-solution was finally chosen (Supplementary Note 3). The results and explanations of the 9–12-factor PMF solutions are provided in Supplementary Fig. 16. Five hundred bootstrap runs were performed for 11-factor solution, yielding 441 accepted bootstrap runs, showing the results were robust. The resolved factors from PMF were correlated with collocated measured physicochemical variables and specific tracers to further verify each factor’s identity. Pearson correlation coefficients were interpreted as follows: 0.2–0.4 indicates weak correlation, 0.4–0.6 indicates moderate correlation and 0.6–1.0 indicates strong correlation. Five POA factors and six SOA factors were identified after analyzing various peaks in each mass spectra, the time series and diurnal variations of each factor.

Backward trajectory cluster and wind analysis

The Hybrid single-particle Lagrangian integrated trajectory (HYSPLIT) model developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States was used to analyze the airflow trajectory in Shanghai during several pollution periods. The sampling site was used as the starting receiver point for backward trajectory simulation with a height of 30 m. The height of 30 m above ground level (AGL) was used as the starting point in the backward trajectories because it corresponds to the height of the sampling inlet of the observation site and we aim to analyze the sources of aerosols at ground. Similar height has been widely used in studies tracking the source of atmospheric trace components92. Furthermore, a mismatch between the starting height and the sampling height can introduce systematic errors in source apportionment93. The meteorological data is based on the Global Data Assimilation System (GDAS) data provided by the National Center for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) of the United States. The assimilated data derived from GDAS1 integrates multi-source observations (e.g., satellite, ground-based) via a global data assimilation system to generate standardized meteorological fields. GDAS1 features a global 1° × 1° spatial resolution and 6-hourly analysis data (UTC 00, 06, 12, 18), with weekly data packages. Key variables include 3D wind fields (UGRD, VGRD), temperature (TMP), humidity (SPFH), and pressure (MSLP), covering 0–50 km vertically. Raw GRIB-format data were processed using wgrib2 or xarray for variable extraction and temporal interpolation to match trajectory start times. The data, quality-controlled via NCEP’s 3DVAR assimilation, is widely applied in atmospheric transport and aerosol source apportionment studies. The 48-h backward trajectory calculation is conducted hourly every day and clustering analysis is performed based on the length and directions of all simulated backward trajectories. Concentration-Weighted Trajectory (CWT) couples factor concentrations with back trajectories and use residence time information to geographically identify air parcels that may be responsible forhigh concentrations observed at the receptor site94. Wind analysis was performed in ZeFir v4.094 by Non-parametric Wind Regression (NWR95) to achieve a comprehensive geographical origin analysis (Supplementary Note 4).

Data availability

The data used in this study are available: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17104989.

References

Lelieveld, J., Evans, J. S., Fnais, M., Giannadaki, D. & Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 525, 367 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. Ubiquity and dominance of oxygenated species in organic aerosols in anthropogenically-influenced Northern Hemisphere midlatitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L13801 (2007).

Kanakidou, M. et al. Organic aerosol and global climate modelling: a review. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 5, 1053–1123 (2005).

Shrivastava, M. et al. Recent advances in understanding secondary organic aerosol: implications for global climate forcing. Rev. Geophys.55, 509–559 (2017).

Wu, X. et al. Molecular composition and source apportionment of fine organic aerosols in Northeast China. Atmos. Environ. 239, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117722 (2020).

Crippa, M. et al. Identification of marine and continental aerosol sources in Paris using high resolution aerosol mass spectrometry. J. Geophys. Res.118, 1950–1963 (2013).

Sun, Y. et al. Investigation of the sources and evolution processes of severe haze pollution in Beijing in January 2013. J. Geophys. Res.119, 4380–4398 (2014).

Zhang, Q. et al. Understanding atmospheric organic aerosols via factor analysis of aerosol mass spectrometry: a review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 401, 3045–3067 (2011).

Zhou, W. et al. A review of aerosol chemistry in Asia: insights from aerosol mass spectrometer measurements. Environ. Sci.22, 1616–1653 (2020).

Timkovsky, J. et al. Comparison of advanced offline and in situ techniques of organic aerosol composition measurement during the CalNex campaign. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 5177–5187 (2015).

Turpin, B. J., Huntzicker, J. J. & Hering, S. V. Investigation of organic aerosol sampling artifacts in the Los-Angeles basin. Atmos. Environ. 28, 3061–3071 (1994).

Subramanian, R., Khlystov, A. Y., Cabada, J. C. & Robinson, A. L. Positive and negative artifacts in particulate organic carbon measurements with denuded and undenuded sampler configurations. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 38, 27–48 (2004).

Kristensen, K., Bilde, M., Aalto, P. P., Petäjä, T. & Glasius, M. Denuder/filter sampling of organic acids and organosulfates at urban and boreal forest sites: gas/particle distribution and possible sampling artifacts. Atmos. Environ. 130, 36–53 (2016).

Canagaratna, M. R. et al. Chemical and microphysical characterization of ambient aerosols with the aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 26, 185–222 (2007).

Gard, E. et al. Real-time analysis of individual atmospheric aerosol particles: design and performance of a portable ATOFMS. Anal. Chem. 69, 4083–4091 (1997).

Zelenyuk, A. & Imre, D. Single particle laser ablation time-of-flight mass spectrometer: an introduction to SPLAT. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 39, 554–568 (2005).

Murphy, D. M. et al. Single-particle mass spectrometry of tropospheric aerosol particles. J. Geophys. Res. 111, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jd007340 (2006).

Zhang, Y. et al. Chemical composition, sources and evolution processes of aerosol at an urban site in Yangtze River Delta, China during wintertime. Atmos. Environ. 123, 339–349 (2015).

Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D. et al. An extractive electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (EESI-TOF) for online measurement of atmospheric aerosol particles. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 12, 4867–4886 (2019).

Zhu, S. H. et al. Tracer-based characterization of source variations of PM2.5 and organic carbon in Shanghai influenced by the COVID-19 lockdown. Faraday Discuss. 226, 112–137 (2021).

Wang, Q. Q. et al. Hourly measurements of organic molecular markers in Urban Shanghai, China: primary organic aerosol source identification and observation of cooking aerosol aging. ACS Earth Space Chem. 4, 1670–1685 (2020).

Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D. et al. A novel method for online analysis of gas and particle composition: description and evaluation of a Filter Inlet for Gases and AEROsols (FIGAERO). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 7, 983–1001 (2014).

Eichler, P., Müller, M., D’Anna, B. & Wisthaler, A. A novel inlet system for online chemical analysis of semi-volatile submicron particulate matter. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 1353–1360 (2015).

Zhao, J. et al. Characterization of the Vaporization Inlet for Aerosols (VIA) for online measurements of particulate highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 17, 1527–1543 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. The characterization of ambient levoglucosan in Beijing during summertime: dynamic variation and source contributions under strong cooking influences. J. Environ. Sci. 155, 205–220 (2025).

Qi, L. et al. Organic aerosol source apportionment in Zurich using an extractive electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (EESI-TOF-MS) – Part 2: Biomass burning influences in winter. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 8037–8062 (2019).

Kumar, V. et al. Highly time-resolved chemical speciation and source apportionment of organic aerosol components in Delhi, India, using extractive electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 7739–7761 (2022).

Stefenelli, G. et al. Organic aerosol source apportionment in Zurich using an extractive electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (EESI-TOF-MS) – part 1: biogenic influences and day–night chemistry in summer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 14825–14848 (2019).

Tong, Y. et al. Quantification of solid fuel combustion and aqueous chemistry contributions to secondary organic aerosol during wintertime haze events in Beijing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 9859–9886 (2021).

Ge, D. et al. New insights into the sources of atmospheric organic aerosols in East China: a comparison of online molecule-level and bulk measurements. J. Geophys. Res. 129 https://doi.org/10.1029/2024jd040768 (2024).

Qi, L. et al. A 1-year characterization of organic aerosol composition and sources using an extractive electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (EESI-TOF). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 7875–7893 (2020).

Zhu, S. -h Chemical characteristics and source apportionment of organic aerosols in urban Shanghai during cold season based on high time-resolution measurements of organic molecular markers. Huanjing Kexue 44, 3760–3770 (2023).

Simoneit, B. R. T. Biomass burning — a review of organic tracers for smoke from incomplete combustion. Appl. Geochem. 17, 129–162 (2002).

Yee, L. D. et al. Secondary organic aerosol formation from biomass burning intermediates: phenol and methoxyphenols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 8019–8043 (2013).

Brown, W. L. et al. Real-time organic aerosol chemical speciation in the indoor environment using extractive electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Indoor Air 31, 141–155 (2020).

He, L.-Y. et al. Measurement of emissions of fine particulate organic matter from Chinese cooking. Atmos. Environ. 38, 6557–6564 (2004).

Abeliotis, K. & Pakula, C. Reducing health impacts of biomass burning for cooking—the need for cookstove performance testing. Energy Effic.6, 585–594 (2013).

Huang, D. D. et al. Comparative assessment of cooking emission contributions to urban organic aerosol using online molecular tracers and aerosol mass spectrometry measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 14526–14535 (2021).

Yu, J. et al. Observation of gaseous and particulate products of monoterpene oxidation in forest atmospheres. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 1145–1148 (1999).

Liu, J. et al. Monoterpene photooxidation in a continuous-flow chamber: SOA yields and impacts of oxidants, NOx, and VOC precursors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 12066–12076 (2022).

Mutzel, A., Rodigast, M., Iinuma, Y., Böge, O. & Herrmann, H. Monoterpene SOA – contribution of first-generation oxidation products to formation and chemical composition. Atmos. Environ. 130, 136–144 (2016).

Song, K. et al. Impact of cooking style and oil on semi-volatile and intermediate volatility organic compound emissions from Chinese domestic cooking. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 9827–9841 (2022).

Huang, X. et al. Characteristics and health risk assessment of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in restaurants in Shanghai. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 490–499 (2019).

Li, L. et al. Effects of photochemical aging on the molecular composition of organic aerosols derived from agricultural biomass burning in whole combustion process. Sci. Total Environ. 946 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174152 (2024).

Unger, N., Shindell, D. T., Koch, D. M. & Streets, D. G. Air pollution radiative forcing from specific emissions sectors at 2030. J. Geophys. Res. 113 https://doi.org/10.1029/2007jd008683 (2008).

Tan, P. -q Soluble organic fraction and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in particulate matter emissions from diesel engine with biodiesel fuel. J. Mech. Eng. 48, 115 (2012).

Rosso, B. et al. Quantification and characterization of additives, plasticizers, and small microplastics (5–100 μm) in highway stormwater runoff. J. Environ. Manag. 324 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116348 (2022).

Lunderberg, D. M. et al. Characterizing airborne phthalate concentrations and dynamics in a normally occupied residence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 7337–7346 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Dynamic variations of phthalate esters in PM2.5 during a pollution episode. Sci. Total Environ. 810 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152269 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. PM2.5 bound phthalates in four metropolitan cities of China: concentration, seasonal pattern and health risk via inhalation. Sci. Total Environ. 696 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133982 (2019).

Sasidharan, S. et al. Secondary organic aerosol formation from volatile chemical product emissions: model parameters and contributions to anthropogenic aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 11891–11902 (2023).

Shah, R. U. et al. Urban oxidation flow reactor measurements reveal significant secondary organic aerosol contributions from volatile emissions of emerging importance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 714–725 (2019).

Humes, M. B. et al. Limited secondary organic aerosol production from acyclic oxygenated volatile chemical products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 4806–4815 (2022).

Song, K. et al. Investigation of partition coefficients and fingerprints of atmospheric gas- and particle-phase intermediate volatility and semi-volatile organic compounds using pixel-based approaches. J. Chromatography A 1665 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2022.462808 (2022).

Liao, K. et al. Secondary organic aerosol formation of fleet vehicle emissions in China: potential seasonality of spatial distributions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 7276–7286 (2021).

Zhu, S. et al. Evolution and chemical characteristics of organic aerosols during wintertime PM2.5 episodes in Shanghai, China: insights gained from online measurements of organic molecular markers. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 7551–7568 (2023).

He, X. et al. Hourly measurements of organic molecular markers in urban Shanghai, China: Observation of enhanced formation of secondary organic aerosol during particulate matter episodic periods. Atmos. Environ. 240 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117807 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Intermediate volatility organic compound emissions from on-road diesel vehicles: chemical composition, emission factors, and estimated secondary organic aerosol production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 11516–11526 (2015).

Coggon, M. M. et al. Volatile chemical product emissions enhance ozone and modulate urban chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2026653118 (2021).

Gkatzelis, G. I. et al. Observations confirm that volatile chemical products are a major source of petrochemical emissions in U.S. Cities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 4332–4343 (2021).

McDonald, B. C. et al. Volatile chemical products emerging as largest petrochemical source of urban organic emissions. Science 359, 760–764 (2018).

Sun, Y. L. et al. Aerosol composition, sources and processes during wintertime in Beijing, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 4577–4592 (2013).

Xiao, Y. et al. Insights into aqueous-phase and photochemical formation of secondary organic aerosol in the winter of Beijing. Atmos. Environ. 259 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2021.118535 (2021).

Kuang, Y. et al. Photochemical aqueous-phase reactions induce rapid daytime formation of oxygenated organic aerosol on the North China Plain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 3849–3860 (2020).

Xu, W. et al. Effects of aqueous-phase and photochemical processing on secondary organic aerosol formation and evolution in Beijing, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 762–770 (2017).

Bertrand, A. et al. Evolution of the chemical fingerprint of biomass burning organic aerosol during aging. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 7607–7624 (2018).

Yazdani, A. et al. Chemical evolution of primary and secondary biomass burning aerosols during daytime and nighttime. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 7461–7477 (2023).

Kodros, J. K. et al. Rapid dark aging of biomass burning as an overlooked source of oxidized organic aerosol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 33028–33033 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Formation of condensable organic vapors from anthropogenic and biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) is strongly perturbed by NOx in eastern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 14789–14814 (2021).

Cook, R. D. et al. Biogenic, urban, and wildfire influences on the molecular composition of dissolved organic compounds in cloud water. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 15167–15180 (2017).

Brege, M. et al. Molecular insights on aging and aqueous-phase processing from ambient biomass burning emissions-influenced Po Valley fog and aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 13197–13214 (2018).

Andreae, M. O. & Merlet, P. Emission of trace gases and aerosols from biomass burning. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 15, 955–966 (2001).

Wang, H. et al. Anthropogenic monoterpenes aggravating ozone pollution. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, nwac103 (2022).

Duan, J. et al. Measurement report: Large contribution of biomass burning and aqueous-phase processes to the wintertime secondary organic aerosol formation in Xi’an, Northwest China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 10139–10153 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Aqueous production of secondary organic aerosol from fossil-fuel emissions in winter Beijing haze. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2022179118 (2021).

Gilardoni, S. et al. Direct observation of aqueous secondary organic aerosol from biomass-burning emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10013–10018 (2016).

Tong, Y. et al. Quantification of primary and secondary organic aerosol sources by combined factor analysis of extractive electrospray ionisation and aerosol mass spectrometer measurements (EESI-TOF and AMS). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 15, 7265–7291 (2022).

Luo, H. et al. Effect of relative humidity on the molecular composition of secondary organic aerosols from α-pinene ozonolysis. Environ. Sci. Atmos.4, 519–530 (2024).

Junninen, H. et al. A high-resolution mass spectrometer to measure atmospheric ion composition. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 3, 1039–1053 (2010).

Wu, C. et al. Photolytically induced changes in composition and volatility of biogenic secondary organic aerosol from nitrate radical oxidation during night-to-day transition. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 14907–14925 (2021).

Tumminello, P. R. et al. Evolution of sea spray aerosol particle phase state across a phytoplankton bloom. ACS Earth Space Chem. 5, 2995–3007 (2021).

Jensen, A. R., Koss, A. R., Hales, R. B. & de Gouw, J. A. Measurements of volatile organic compounds in ambient air by gas-chromatography and real-time Vocus PTR-TOF-MS: calibrations, instrument background corrections, and introducing a PTR Data Toolkit. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 16, 5261–5285 (2023).

Claflin, M. S. et al. An in situ gas chromatograph with automatic detector switching between PTR- and EI-TOF-MS: isomer-resolved measurements of indoor air. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 133–152 (2021).

Yan, P., Huan, N., Zhang, Y. & Zhou, H. Size resolved aerosol OC,EC at a regional background station in the suburb of Beijing. J. Appl. Meteorolgical Sci. 23, 285–293 (2012).

Birch, M. E. & Cary, R. A. Elemental carbon-based method for monitoring occupational exposures to particulate diesel exhaust. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 25, 221–241 (1996).

Chang, Y. et al. Assessment of carbonaceous aerosols in Shanghai, China – Part 1: long-term evolution, seasonal variations, and meteorological effects. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 9945–9964 (2017).

Chang, Y. et al. First long-term and near real-time measurement of trace elements in China’s urban atmosphere: temporal variability, source apportionment and precipitation effect. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 11793–11812 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Observation of NO3 radicals over Shanghai, China. Atmos. Environ. 70, 401–409 (2013).

Zhu, J. et al. Changes in NO3 radical and its nocturnal chemistry in Shanghai From 2014 to 2021 revealed by long-term observation and a stacking model: impact of China’s clean air action plan. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127 https://doi.org/10.1029/2022jd037438 (2022).

Ulbrich, I. M., Canagaratna, M. R., Zhang, Q., Worsnop, D. R. & Jimenez, J. L. Interpretation of organic components from Positive Matrix Factorization of aerosol mass spectrometric data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 2891–2918 (2009).

Hopke, P. K., Dai, Q., Li, L. & Feng, Y. Global review of recent source apportionments for airborne particulate matter. Sci. Total Environ. 740 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140091 (2020).

Wang, S., Cohen, J. B., Lin, C. & Deng, W. Constraining the relationships between aerosol height, aerosol optical depth and total column trace gas measurements using remote sensing and models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 15401–15426 (2020).

Cohen, M. D. et al. NOAA’s HYSPLIT atmospheric transport and dispersion modeling system. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 96, 2059–2077 (2015).

Petit, J. E., Favez, O., Albinet, A. & Canonaco, F. A user-friendly tool for comprehensive evaluation of the geographical origins of atmospheric pollution: Wind and trajectory analyses. Environ. Model. Softw. 88, 183–187 (2017).

Henry, R., Norris, G. A., Vedantham, R. & Turner, J. R. Source region identification using kernel smoothing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 4090–4097 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Shanghai Pilot Program for Basic Research-Fudan University 21TQ1400100 (22TQ010) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42575109). We thank Douglas Worsnop for helpful discussion on PMF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z. conceptualized the idea and planned the study. S.X., Z.W., H.L., Y.Z. and S.W. conducted the data collection. S.X. analyzed the campaign data with the help of C.N. on some coding. S.X. and Z.W. performed the fitting of mass spectra. S.X. interpreted the data and conducted PMF model. Z.S. provided suggestions for backward trajectory analysis. S.X. and D.Z wrote and edited the manuscript and the Supplementary Information with the input from all authors. S.X., H.L., Z.W., H.S., Y.Z., C.N., Z.S., L.W., S.W., J.C. and D.Z. discussed the results and commented on the manuscript and Supplementary Information.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, S., Luo, H., Wang, Z. et al. Online molecular insights into sources and formation of organic aerosol in Shanghai. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 358 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01230-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01230-6