Abstract

Extreme rainfall and flooding, driven by a powerful atmospheric river (AR) and a persistent Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO), hit Southern California in February 2024 during the 2023–2024 El Niño, affecting over 10 million people. ARs are key contributors to extreme rainfall and flooding along the U.S. West Coast. Although the AR-MJO link has been documented, its spatio-temporal variability remains a major forecasting and risk-management challenge. Combining precipitation, stream gauge and demographic data, we quantify the physical drivers and population exposure to this extreme event. Leveraging a Lagrangian MJO precipitation tracking algorithm, we unravel the multiscale interactions responsible for the AR’s development. El Niño favored a large, long-lived MJO that interacted with the North Pacific Jet (NPJ) over more than three weeks. The MJO convective outflow modulated the NPJ by inducing negative potential vorticity advection along the tropopause. The ensuing NPJ extension and acceleration induced explosive cyclogenesis, whose AR-driven moisture transport resulted in extreme rainfall.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In early February 2024, a powerful Atmospheric River (AR) struck Southern California, unleashing record-breaking rainfall that prompted a state of emergency, widespread evacuation orders, and left behind over 130 reports of flooding and 120 mudslides in its wake, according to state officials. The AR was part of a low-pressure system that experienced unusually explosive cyclogenesis at low latitudes, causing intense rainfall and widespread wind damage along the central California coast from the Big Sur to the Santa Cruz Mountains. This powerful AR system occurred during strong El Niño conditions and was preceded by a persistent Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) precipitation event, underscoring the complex multi-scale interaction responsible for the extreme rain.

ARs are relatively narrow bands of enhanced lower-tropospheric, horizontal water vapor transport, typically located in the warm sector of extra-tropical cyclones. They play a critical role within the Earth system, accounting for the majority of horizontal water vapor transport in the extra-tropics1,2,3. ARs significantly influence the hydrological cycle in many regions, such as the western United States4,5,6,7. Their impacts are particularly critical in California, where they affect water management, snowpack variability8 and the frequency of extreme rain events9,10,11.

The MJO is characterized by a dipole of suppressed and enhanced convection, along with an associated three-dimensional circulation, which propagates eastward from the Indian Ocean12. The MJO convection and precipitation display a complex multi-scale variability, ranging from diurnal to subseasonal to interannual time scales13,14,15. The MJO convection often weakens or dissipates as it attempts to cross the Maritime Continent16,17 due to topographic barriers18, reduced heat fluxes from the ocean19,20 and land-locked convection21.

While the link between the MJO and ARs has long been established e.g., refs. 22,23,24,25,26,27, mostly based on the traditional RMM index28, the extra-tropical atmospheric response to the MJO is complex and not yet fully understood. It is in part due to the lack of information on the actual location and intensity of the MJO convection/precipitation. The RMM is based on composites of the zonal propagation of wind and OLR anomalies that cannot represent meridional precipitation distribution relative to the equator and the exact location and strength of the convective heating sources that drive the actual large-scale circulation, which is critical to the teleconnection. Not all MJOs promote ARs, and when they do, their impacts vary significantly in terms of intensity, timing, and geography. This variability represents a critical challenge for both forecasters and risk managers. In this study, we aim to bridge this gap by examining the multi-scale pathway, including El Niño, the MJO, and the North Pacific Jet (NPJ), that fueled the catastrophic February 2024 Southern California AR.

The occurrence of extreme hydrometeorological events is fundamentally tied to distinct and infrequent interactions between atmospheric and oceanic processes, which can lead to enhanced precipitation rate or duration29,30. ARs can be placed within a multi-scale chain of processes connecting climate variability, such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the Quasi Biennial Oscillation (QBO), and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) (e.g., refs. 31,32,33) to synoptic and mesoscale variability.

On subseasonal-to-seasonal time scales, the MJO34,35 provides a critical source of AR predictability (e.g., refs. 23,24,25,26). MJO-induced tropical heating and upper-level divergence invoke planetary-scale responses, particularly through Rossby waves that propagate into the extra-tropics36,37, forming the physical basis for the MJO-AR teleconnection. Robust statistical relationships link the MJO propagation with downstream AR activity and rainfall along the U.S. West Coast, in particular for Alaska, British Columbia, and the Pacific Northwest24,26,27,38. As an example, enhanced AR activity is observed over British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest ~2 weeks after the MJO is in the Indian Ocean (phase 2–3 of the RMM index). However, not only is there a distinct trade-off in AR activity between different regions along the U.S. West Coast, but these statistical relationships become less robust when considering California24,26.

In this study, we identify the interaction between the MJO convection and the NPJ as the key dynamical link in the multi-scale pathway connecting climate variability to extreme rain during the aforementioned February 2024 event. The position and strength of the NPJ can vary in response to climate variability (e.g., refs. 39,40), tropical convection36,41, extra-tropical and recurving tropical cyclones42,43,44,45. The evolution of the NPJ has profound downstream effects on atmospheric circulation over the North Pacific and North America (e.g., refs. 43,46,47,48,49). We argue that the characteristics of the MJO-NPJ interaction play a critical role in shaping the downstream atmospheric response, offering insights into the variability of the MJO-AR relationship.

To understand and quantify this multiscale pathway, we use the Large-scale Precipitation Tracking (LPT) method, a quantitative highly-informative MJO algorithm that provides critical information on the actual location, intensity and extent of the MJO convection and precipitation using satellite observations16,17. The LPT identifies MJO tracks by first applying a 3-day running mean, a 5-degree Gaussian filter and a 12 mm d−1 threshold to the rainfall. Large-scale precipitating features are considered to have time continuity if they overlap by at least 50% of their area in consecutive hourly frames. To be identified as an MJO, an LPT object must have a duration exceeding 10 days, a mean zonal propagation >0 ms−1 and a 7-day minimum eastward propagation of its centroid within 15°S–15°N. By combining the LPT with reanalysis data, we analyze how the ENSO-dominated background state influences the MJO characteristics, particularly through changes in near-equatorial sea-surface temperature (SST) as well as the atmospheric response to the MJO propagation. We isolate the dynamical connection between the upper-level MJO outflow and the NPJ, focusing on potential vorticity (PV) redistribution through negative PV advection. Finally, we examine the jet stream’s response and the subsequent downstream impacts on atmospheric circulation, which culminated in an unusually explosive low-latitude cyclogenesis event that drove the intense AR system. To better isolate the importance of the ENSO background state and the MJO characteristics, the 2024 MJO is compared to three analog cases.

Results

Extreme coastal rainfall and flooding

The most intense rainfall across Southern California occurred from February 5th to 6th, with 48-hour totals exceeding 100 mm (4”) across a broad swath of the coastal region, from Santa Barbara County to the northern part of San Diego County. The region’s complex topography, coupled with the orientation of the AR, generated two distinct rainfall maxima closely aligned with the Transverse Ranges. Localized maxima of over 300 mm (11.8”) were observed northeast of Santa Barbara, north of Malibu, and in the San Bernardino National Forest, where the highest rainfall total was recorded: 464.9 mm (18.3”). In the Los Angeles metropolitan area, rainfall ranged from 50 mm (2”) near Manhattan Beach to more than 150 mm (5.9”) in the northern sectors from Westwood to Pasadena. The highest rainfall in Los Angeles County, 301.2 mm (11.85”), was measured just north of Topanga Beach. Significant rainfall (>2”) was also observed further inland, extending into the Mojave Desert and Death Valley (Fig. 1a).

a NCEP Stage IV Feb 5–6 Total accumulated rainfall; b 2-day Extreme Rain Multiplier (ERM). The Santa Barbara, Ventura, Los Angeles, Orange, and San Diego county outlines are shown in black; c USGS and LA DPW stream gauges in Los Angeles and Orange counties. Gauges that experienced extreme streamflow above their respective 99th percentile (and likely extreme flooding) are denoted by the red diamond markers; all other gauges are indicated by the white circular markers. The area that experienced ERM ≥ 2.5 is shown by the gray shaded area, along with all USGS California streams and rivers longer than 10 km. The inset in b shows a zoomed view of the Los Angeles metro census tracts used to compute the population exposure to extreme rainfall in d as a function of the ERM. The fraction of the total population exposed to a particular ERM value is shown by the color scale.

Such 48-hour rainfall accumulations are highly unusual for coastal Southern California. To quantify the extremity and impacts of this rain event, we employ the Extreme Rain Multiplier (ERM, 49), which expresses the magnitude of the accumulated precipitation relative to a locally defined heavy rain event, often represented by the median annual maximum rainfall over the chosen timescale50,51. The 2-day ERM (February 5–6) shows that the event produced significantly more rainfall than a typical heavy rain event (ERM > 1.0) along almost the entire coastal stretch from Point Arguello to Oceanside (Fig. 1b). The event was most extreme in the near-coastal portion of Los Angeles County, where ERM values exceeded 3.6.

Extreme rainfall, combined with the region’s complex topography and high population density, can lead to devastating flooding with significant societal consequences. The ERM = 2.5 contour encompasses most of the Los Angeles metropolitan area, including the headwaters of the Los Angeles, San Gabriel, and Santa Ana rivers. Consequently, more than 20 streamflow gauges in the area recorded extreme flooding conditions between February 5 and 9, with daily flows surpassing the 99th percentile of the historical record at each gauge (Fig. 1c). For six of these gauges—Rio Hondo at Garvey St., Topanga Creek, Ballona Creek, and the Los Angeles River above Arroyo Seco, Tujunga Ave, and Wardlow St.—the event ranks among the top 10 highest flows on record, with three of them ranking in the top 5. Extreme flooding was also observed at other gauges across Orange and San Diego counties.

Using the calculated ERM and 2020 census data, we assess coastal vulnerability by computing both absolute and relative population exposure to extreme rainfall in the five coastal counties: Santa Barbara, Ventura, Los Angeles, Orange, and San Diego. Each census tract is assigned an ERM value by interpolating the 2-day ERM map (Fig. 1b) onto the internal point of each census tract (examples for Los Angeles are shown in Fig. 1b). We then rank the census tracts based on their ERM values and display the cumulative population exposed (Fig. 1d). The February 2024 AR exposed over 80% of the coastal population to rainfall equal to or greater than a typical heavy rain event (ERM ≥ 1). For more than 11 million people—~60% of the population—the event was twice as extreme as a typical heavy rain event. As illustrated in Fig. 1c, these conditions created a high risk for extreme urban flooding. Nearly 20% of the population (3.1 million people) experienced an event with an ERM magnitude ≥3.0, primarily in the greater Los Angeles metro area and the Santa Monica Mountains. ERM values of this magnitude in the U.S. are comparable to those associated with some of the most intense precipitating systems, such as tropical cyclones51.

An El Niño augmented MJO

We begin by examining the dynamical pathway that led to the extreme rainfall in Southern California, starting with the role of ENSO and its influence on the MJO. The MJO event preceding the AR displayed exceptional characteristics. With a duration of more than 72 days, it represents one of the longest MJO events tracked, exceeding the 96th percentile of MJO durations in the 2000–2023 climatology (Fig. 2c). It originated over the African continent in late December 2023 and progressed eastward, crossing the Maritime Continent and extending into the western Pacific by the end of January 2024 (Fig. 2a). This MJO event had three distinctive traits: 1) an exceptional duration, 2) a large convective envelope (Figs. 2a) and 3) unusually persistent eastward propagation of extensive large-scale precipitation into the Central Pacific (Fig. 2b).

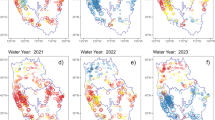

a Dec 12 – Feb 12 average daily OI-SST anomaly (shaded), MJO-LPT contours color-coded by date; b longitude-time evolution of average daily OI-SST anomaly in the 10S–10N region (shaded), MJO-LPT centroid (black), MJO-LPT longitudinal extent (gray shading); c maximum centroid longitude and cumulative area for all MJO 2000–2023 events originating west of 125°E, along with the corresponding bivariate probability density function (shaded, their respective median values are shown by the dashed lines). The c inset shows the distribution of the events’ duration. The Dec 2023–Feb 2024 event is shown by the magenta marker. The red, blue, and white markers denote the 2009–2010, 2013–2014, and 2016 MJO analogs discussed in the following section, respectively.

MJO-LPT (green contour and shading) and rainfall (blue scale), 200 mb irrotational wind (vectors), wind speed (greyscale), and negative PV advection by the irrotational wind (colored contours every 0.5 PVU/day) at 00 UTC on a Jan 5, b Jan 12, c Jan 16, d Jan 20, e Jan 24, f Jan 26, g Jan 27, h Feb 5. i Time series of 200 mb maximum negative PV advection by the irrotational wind in the 90–180°E/10–50°N box. The January climatological position and magnitude of the North Pacific Jet is shown in the inset axis of a along with the box used to compute the MJO-NPJ interaction.

This MJO occurred during a strong El Niño event that was initiated in May 2023, peaked in November 2023, and was preceded by an extreme coastal El Niño during the boreal spring52,53. MJOs during El Niño events are typically longer-lived, and travel farther eastward and at faster speeds17,54,55,56,57. The favorable El Niño background state contributed to the eastward progression of this MJO and its crossing of the maritime continent (Fig. 2a) by inducing a substantial near-equatorial SST anomaly between 170 and 135 °W (Fig. 2b). The unusual combination of size and persistence characterizing this event made this MJO stand out from the majority of its counterparts. The duration of this MJO event far exceeded that of the average MJO-LPT (~28 days, Fig. 2c). Moreover, many MJOs originating west of the Maritime Continent do not cross 130°W, even those that do typically have much smaller convective envelopes over their lifetime (cumulative area ~250 × 107 km2, Fig. 2c). The January-February 2024 MJO is one of the most extreme outliers in the 22-year IMERG-based climatology, with only two previous events exhibiting broader convective envelopes. While many MJOs can reach the Central Pacific, these events tend to be much smaller in size (Fig. 2c). We argue that the unprecedented combination of the MJO’s size and persistent eastward propagation enabled a prolonged and substantial interaction with the NPJ.

The MJO-NPJ interaction

The interaction between the MJO and the NPJ represents a key dynamical link in this multiscale pathway, and is driven by the MJO divergent outflow’s ability to rearrange upper-level PV, which in turn modulates the strength and position of the jet, and shapes the downstream atmospheric response. To quantify this mechanism, we compute the negative PV advection induced by the MJO divergent outflow in the upper troposphere, as discussed in the Methods section (Eq. 1).

As shown in Fig.3a, i, before the passage of the MJO, the jet is only minimally perturbed, possibly due to enhanced convective activity associated with the ongoing El Niño event and relatively close to its climatological state. Background levels of negative PV advection oscillate around −1 PVU day−1. In contrast, as the MJO convection propagates further east, the interaction significantly strengthens: starting on 12 January 2024, negative PV advection in the area nearly doubled as the MJO approached the Maritime Continent (Fig. 3a, b, i). At this stage, the MJO had an extensive convective envelope that spanned from 90°W to the dateline, with a prominent field of divergent outflow along its northern flank (Fig. 3b). It is worth noting that the upper-level outflow is not symmetrically distributed around the MJO convective envelope. While this reflects the variability in convection within the MJO envelope, it is also likely influenced by the interaction with the NPJ itself. In particular, the anticyclonic shear on the equatorward side of the jet significantly reduces the local inertial stability, thus creating a preferential pathway for the MJO outflow expansion. During most of the interaction, the perturbation remained around −2 PVU day−1. As a result, the NPJ extended zonally and accelerated (Fig. 3c–e). It is also important to highlight the critical role of synoptic-scale processes in the mid-latitudes in supporting the jet extension and acceleration. The NPJ evolution was, in fact, accompanied by a deep low-pressure system to its north, centered around 150°W. The circulation associated with it acted to consolidate the baroclinicity beneath the jet along the cyclone’s trailing cold front, thus promoting the persistent zonal jet extension. The MJO-induced perturbation reached its peak amplitude farther upstream (−3.1 PVU day−1) on 27 January (Fig. 3g) as the MJO completed traversing the Maritime Continent.

This enhanced MJO outflow induced a dynamic response of the NPJ, leading to a significant zonal extension and acceleration of the jet. The resulting westerly flow, greater than 90 m/s, stretched along a narrow corridor from the eastern coast of China to 140°W (Fig. 3g). This jet configuration was substantially different from the climatology, highlighting the MJO’s ability to profoundly influence extra-tropical dynamics. The interaction weakened during the last week of January (Fig. 3h) as the MJO propagated into the central and eastern Pacific. Its strongest divergent outflow was isolated south of 30°N, where it could no longer significantly perturb the NPJ (Fig. 3h), which, as a result, weakened substantially.

The exceptional longevity and scale of this MJO event enabled a prolonged interaction with the NPJ. As shown in Fig. 3i, the interaction lasted for over 3 weeks, far surpassing the duration of typical tropical cyclone-NPJ interactions for instance (e.g., 44), and providing a critical source of predictability beyond the typical range of numerical weather prediction forecasts.

The Dec 2023–Feb 2024 MJO represents one of the most extreme events in terms of size and duration (Fig. 2c). To better understand the importance of the MJO characteristics and the associated diversity in the MJO-NPJ interactions, we examine comparable and contrasting cases that serve as very informative analogs. In particular, we aim to isolate the importance of the MJO precipitation area and its eastward extent, as well as the role of the background state in terms of ENSO and its influence on the mid-latitudes circulation.

The first analog MJO (Fig. S3a) occurred in Dec 2009–Mar 2010 during a strong (average Niño 3.4 index 1.21) but short-lived El Niño58. It featured a very similar eastward extension but slightly broader convective envelope, thus allowing us to test the robustness of the mechanisms identified in the Jan 2024 case. The second MJO analog allows us to better isolate the role of ENSO variability, as it featured a very similar convective envelope and slightly more limited eastward extension as the Jan 2024 MJO but occurred during weak La Niña conditions (average Niño 3.4 index -0.26) from Nov 2013 to early Feb 2014 (S3b). Finally, an MJO analog is selected to isolate the influence of the MJO convective extent and eastward reach. Like the 2024 case, the Jan 2016 MJO occurred during strong El Niño conditions (average Niño 3.4 index 2.1) but featured near-average size, duration, and eastward propagation (Fig. 2c).

Figure 4 displays the timeseries of the MJO-NPJ interaction (as in Fig. 3i) for all four MJOs, along with the time-longitude evolution of the 200 mb zonal wind maximum over the North Pacific. The 2009–2010, 2013–2014, and 2023–2024 MJOs are characterized by persistent interactions with the NPJ spanning multiple weeks; however, the downstream response varies drastically depending on the background ENSO phase39. In the 2023–2024 and 2009–2010 MJOs, the interaction substantially strengthened around January 12 and January 6, respectively, and the following week was characterized by a substantial NPJ extension well beyond the dateline, which persisted for several days (Fig. 4a, b). Cold ENSO conditions, instead, seem to favor a strengthening of the NPJ without a substantial eastward extension. As shown in Fig. 4c, the 2013–2014 MJO did result in an intensification of the jet stream near 150°E; however, the upper-level response in the eastern North Pacific featured much weaker zonal flow, indicative of an amplified wave pattern. The third analog represents a contrasting case to the Dec 2023–Feb 2024 period in terms of MJO characteristics, with near-average duration and size. The resulting interaction with the NPJ is thus significantly more short-lived, although of similar intensity (Fig. 4d). More importantly, the downstream response of the NPJ is remarkably less coherent, with signs of more transient and weaker jet extensions into the eastern North Pacific.

Time series of MJO-NPJ interaction (left panels, as described in Fig. 3i) and time-longitude evolution of the 200 mb zonal wind (right panels) maximum over the North Pacific basin (20°N–50°N) for the 2023–2024 MJO event (a) and its three analogs b 2009–2010, c 2013–2014, and d 2016. The black dashed line denotes the dateline, while the gray dashed line denotes the longitude of Los Angeles.

The differences in downstream response also have dramatic implications for the occurrence of heavy rainfall along the U.S. West Coast (Fig. S4). The El Niño analog features substantial rainfall accumulations in the 2 weeks following the MJO-NPJ interaction, with a distribution that resembles that of the 2023–2024 case, although with much heavier rainfall over Northern and Central California (>500 mm), which produced high-impact hazards across a wide stretch of coastal California. Conversely, the La Niña analog is associated with extremely dry conditions over most of the western United States. The lack of a persistent NPJ zonal extension following the 2016 MJO is also directly reflected in a much different rainfall distribution across California, with very limited rainfall along the coastal region despite the favorable ENSO conditions.

Examining the NPJ evolution and the downstream response across the analog cases provides fundamental insights into the multi-scale nature of the interaction. The extreme rain event that hit Southern California in early 2024 required a constructive interference of processes on multiple scales, which individually do not seem to account for the sequence of events. An active MJO propagating in favorable El Niño conditions alone does not seem to suffice, as the 2016 analog did not result in a persistent NPJ acceleration and extension (Fig. 4d) nor enhanced precipitation over Southern California (Fig. S4). Similarly, unfavorable extra-tropical dynamics, during La Niña, can hamper the response to a strong MJO-NPJ interaction. Despite a prolonged and intense interaction with the MJO, the NPJ in the 2013–2014 analog did not accelerate and extend completely across the eastern North Pacific, as a stationary ridge located offshore the U.S. west coast limited the jet extension. A consistent jet response and subsequent downstream impacts (e.g., 2024 and the 2009–2010 analog) only emerge when processes constructively interfere: a large and long-lived MJO provides a prolonged forcing to the NPJ, resulting in its acceleration and extension. The jet response in turn favors intense extra-tropical cyclogenesis, which can reinforce and maintain the jet extension, focusing rainfall over a limited portion of the U.S. west coast.

Explosive cyclogenesis and AR

The final step in this multiscale pathway involved explosive low-latitude extra-tropical cyclogenesis, coupled with the direct transport of tropical moisture toward Southern California via an AR.

As a result of its interaction with the MJO, the NPJ accelerated and extended zonally across the North Pacific basin (Fig. 5a). The subsequent breakdown of this zonal jet resulted in the formation of a distinct jet streak around 30°N in early February (Fig. 5b), which played a crucial role in promoting extra-tropical cyclogenesis through quasi-geostrophic forcing. On 3 February 2024, incipient cyclogenesis occurred in the right-entrance region of the jet streak, where synoptic-scale ascent triggered widespread precipitation in association with an AR. A narrow filament of enhanced total precipitable water (TPW) connected the region of cyclogenesis to the tropical moisture reservoir (Fig. 5c). Along this filament, enhanced integrated vapor transport (IVT) indicated the presence of an AR transporting moisture toward the coast (vectors in Fig. 5c, d). While this study primarily focuses on the dynamical role of the MJO and its interaction with the NPJ, Fig. S1 shows that the eastward propagation of the MJO was accompanied by a corresponding moisture anomaly that increased the moisture availability and likely enhanced its poleward transport by the AR.

Over the next 24 hours, the cyclone rapidly deepened as it approached the central California coast (Fig. 5d). Given the central pressure drop of 22.7 mb in 24 hours, the cyclone qualifies as a “bomb cyclone”59. During this phase, significant rainfall affected much of Southern California. The AR progressed eastward, maintaining a direct connection to the tropical moisture reservoir and directing substantial amounts of water vapor toward the coastal region (Fig. 5d). This prolonged moisture transport resulted in widespread rainfall extremes (Fig. 1).

It is worth noting that the MJO-induced jet acceleration is not only relevant for the Southern California AR. A deep extra-tropical cyclone can be seen in the left-exit region of the jet, where quasi-geostrophic forcing also favors intensification (Fig. 5a). The cyclone was associated with a well-defined AR directed towards the Pacific Northwest and the Northern California coast. As discussed in the previous section, this intense extratropical cyclone likely played an important role in reinforcing the extension of the NPJ. Its circulation consolidated the baroclinicity beneath the NPJ along the cyclone’s trailing cold front, thus maintaining its eastward propagation. These dynamics highlight the ability of the MJO to trigger clusters of extreme hydrometeorological events across a wide geographical region.

Discussion

The influence of the MJO on the extra-tropical atmospheric circulation has long been recognized (e.g., refs. 24,26,36,37,38), and is considered one of the primary sources of predictability for ARs over the western U.S. on subseasonal-to-seasonal timescales (e.g., refs. 22,23,24,25,26,27). However, not all MJOs lead to enhanced AR activity27, and when they do, the impact varies across regions in terms of intensity, timing, and duration. The spatio-temporal variability of this MJO-AR connection has profound regional and socio-economic implications, but remains poorly understood.

In this study, we investigate the February 2024 Southern California flooding event to identify a novel dynamical pathway in which the interaction between the MJO large-scale convection/precipitation and the NPJ played a critical role in shaping the downstream atmospheric response and subsequent AR-fueled extreme precipitation. The multiscale pathway can be summarized as follows (Fig. 6a) El Niño conditions favored an unusually large and long-lived MJO-LPT capable of propagating into the west-central Pacific; b) the MJO’s large-scale convective heating and outflow enabled a strong and prolonged interaction with the NPJ; and c) The MJO-NPJ interaction, combined not only with a favorable ENSO background state but also with conducive extra-tropical circulation, resulted in significant zonal jet extension and acceleration, which facilitated explosive low-latitude cyclogenesis farther downstream and the associated AR system.

IMERG MJO-LPT position (green contour and shading), ERA5 200 mb wind speed (greyscale), 200 mb irrotational wind (black vectors), rain rate (blue scale), TPW (purple shading where >25 mm), IVT vectors (indigo, where AR criteria are met), and monthly OI-SST anomaly between 15°N–15°S (red scale) at 00 UTC 18 Jan 2024.

This pathway relies on the MJO’s ability to rearrange the upper-level PV field by advecting low-PV air poleward, which induces significant changes in the strength and position of the NPJ. This process is directly comparable to the influence of recurving or transitioning tropical cyclones (e.g., refs. 42,43,46,47). Substantial differences exist, however, in the manner in which MJO interacts with the NPJ, compared to TCs. Due to its size and propagation speed, the MJO perturbation to the jet can persist for several weeks (Fig. 3e), while the synoptic-scale nature of TCs, combined with their typical W/NW propagation in the area, usually limits their influence on the jet and the downstream response to a few days44,45. Moreover, the large scale of the MJO convective envelope, combined with the even broader extent of its upper-level outflow, can result in patterns of interactions substantially bigger than what is typically observed with TCs, and that can initiate even when the MJO and the NPJ are substantially far apart. The jet stream plays a key role in influencing the lifecycle of ARs37. In response to the formation of a distinct jet streak, a deep low-latitude cyclone developed and was accompanied by a powerful AR system that produced extreme precipitation across much of the coastal region.

The characteristics of the MJO-NPJ interaction—such as intensity and duration— may not only help explain the diversity of the MJO-AR relationship, but are also influenced by the background climate state. The prevailing El Niño conditions very likely facilitated the MJO’s extended propagation into the west-central Pacific17,52,55,56,57 while also sustaining an unusually large convective envelope. While El Niño events are typically associated with negative SST and moisture anomalies over the Maritime Continent that can slow or impede the MJO from propagating, the December 2023-February 2024 MJO was unlikely altered by ENSO in that regard. SSTs around the MC remained near or above 28 °C, well above the thresholds typically associated with deep tropical convection60,61,62. It is possible that the observed increase in SST observed globally and in particular across the Indian Ocean and Maritime Continent has contributed to partially offsetting any negative ENSO influence. The anomalous combination of size and eastward propagation enabled a prolonged interaction with the NPJ, whose position is typically shifted equatorward during El Niño events39, and thus more receptive to interactions with an MJO and more prone to a substantial acceleration and zonal extension, which are typically required to bring enhanced rainfall to central and southern California.

Understanding the variability within the MJO-AR teleconnection is crucial for improving the predictability of high-impact weather events over the western U.S., particularly within the context of a changing climate. Not only is the MJO-NPJ jet connection likely to systematically change in response to anthropogenic warming63, but also the AR precipitation rate is projected to increase64, and the precipitation scaling might even exceed the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship regionally across the Tropics and subtropics, especially in the Northern Hemisphere65. As shown in Fig. 4, the MJO-NPJ interaction is linked to multiple ARs impacting a wide geographical area, highlighting the possibility of this mechanism being responsible for clusters of extreme hydrometeorological events. The extreme rainfall event in early February 2024 produced record-breaking accumulations across densely populated coastal regions, exposing 11 million people (60% of the population) to rainfall twice as intense as a typical heavy rain event. The peak intensity occurred in the greater Los Angeles metro area, where ~3 million people experienced an event more than three times as strong as a typical heavy rain. Such an extreme event is rare in Southern California, and its magnitude and extent are comparable only to tropical cyclone landfalls in the southeastern U.S.50,51. Events of this scale typically place significant stress on the hydro-geological system, as evidenced by the widespread flooding, mudslides, and debris flows reported in the aftermath.

Methods

MJO tracking

To track the spatio-temporal evolution of the MJO, we use the LPT algorithm16,17, which provides detailed information on the position, extent, and intensity of the MJO convective envelope from gridded precipitation data (e.g., refs. 21,66,67). Following the methodology outlined by Kerns and Chen16,17, LPT is applied to hourly, 0.1-degree resolution IMERG rainfall data68 as follows: 1) a 72-hour running sum is applied, 2) Gaussian filtering with a 5-degree radius is used to remove synoptic-scale features, 3) contiguous areas exceeding a threshold (12 mm/day) are retained, 4) overlapping areas across consecutive timesteps (>50% of the area or at least 4000 grid points) are connected to form a 3-dimensional (latitude, longitude, time) physical object, and 5) objects meeting specific criteria (minimum size of 2500 grid points (300,000 km2 near the equator), duration exceeding 10 days, and eastward zonal propagation speed >0 ms−1 within 15°S-15°N for at least 7 days) are identified as MJO events.

The LPT is primarily sensitive to the accumulated rainfall threshold16. To ensure the robustness of the results, we replicate the tracking using five different levels (refs. 10,11,12,13,15 mm day−1). As shown in Figure. S2, the position and spatial extent throughout the MJO lifecycle only show minor sensitivity, ensuring robustness to the conclusions of our study.

Meteorological and oceanographic data

Hourly atmospheric data (200-hPa wind and PV, sea-level pressure, TPW, integrated water vapor transport, and rain rate) used in this analysis are obtained from the ERA5 reanalysis69. Oceanographic data, including sea surface temperature, are sourced from the daily Optimum Interpolation-Sea Surface Temperature (OI-SST) analysis70.

MJO-NPJ interaction

The interaction (I) between the MJO and NPJ is quantified by the negative advection of PV by the irrotational wind (Eq. 1). This method, commonly used to diagnose the influence of recurving tropical cyclones (TCs) (e.g., refs. 44,45,47,71), describes how upper-tropospheric outflow rearranges the PV distribution subsequently affecting the location, amplitude, and waviness of the jet stream. To isolate the MJO-related portion of the outflow and remove other spatio-temporal variability, we adopt a framework similar to that used by refs. 16,17 for MJO tracking using gridded rainfall data. The interaction is calculated as follows:

-

1.

The 200-hPa wind field is decomposed into its non-divergent and irrotational components.

-

2.

A 3-day running mean and a 5-degree Gaussian filter are applied to the irrotational wind component (\({V}_{\chi })\) to retain only the MJO-related outflow.

-

3.

A 5-degree Gaussian filter is applied to the 200-hPa PV field to remove synoptic (and smaller) scale features.

-

4.

The interaction is computed as the maximum negative PV advection in the region

AR detection

The location of ARs within the ERA5 reanalysis is identified using the Atmospheric River Life Cycle Detection (ARLID, 71) algorithm. ARLID is a novel AR identification method that provides global space-time tracking of ARs. It applies a blob-detection technique to the IVT and TPW fields separately before combining them into AR objects. Subsequently, the AR objects are tracked in time through their lifecycle based on the overlap between consecutive hourly AR objects. TPW blobs are defined based on the exceedance threshold (10 mm) relative to the local environment TPW. IVT blobs instead are identified by first applying an edge-detection method (i.e., 2-D Laplace of Gaussian filter) to the IVT field and then by retaining only areas of filtered IVT < -7 kgm−1 s−1 deg−2. Prior to the identification of TPW and IVT blobs, a Laplace of Gaussian filter combined with an erosion-dilation method is applied to identify the deep tropical moisture reservoir, and AR objects are not allowed to be entirely within the moisture reservoir. In Figs. 4 and 5, we display the IVT vectors where AR conditions are met and the TPW field (when greater than 25 mm) to highlight the direction of the moisture transport and the connection to the tropical moisture reservoir. A detailed comparison of the performance of ARLiD compared to other commonly used AR detection methods is provided by ref. 72. The AR frequency of occurrence as detected by ARLiD is in line with that of other methods, in particular TempestLR73, with which it shares methodological commonalities.

Rainfall and extreme rain multiplier

The gridded precipitation estimates used to analyze the Southern California extreme rain event are derived from the NCEP Stage IV dataset74. Stage IV is a multi-sensor, bias-adjusted product that combines radar-based rainfall estimates with rain gauge measurements and undergoes both manual and automated quality control. The data from all 12 River Forecast Centers are mosaicked onto a 4 km grid. The product is available at hourly, 6-hourly, and daily intervals, and has been used to study various high-impact rainfall processes, from tropical cyclones (e.g., refs. 51,75,76) to mesoscale convective systems77. To quantify the intensity of the rain event relative to local climatology, we employ the Extreme Rain Multiplier (ERM)50, which normalizes the total accumulated rainfall by a locally defined typical heavy rain event. Following refs. 50,51, we define a typical heavy rain event as the 2-year event (i.e., the median annual maximum n-day rainfall, where n is an integer) computed over the 2002–2023 period. For this study, we compute the 2-day ERM using the NCEP Stage IV gridded daily precipitation estimates.

Streamflow data and statistics

Streamflow data for this study are obtained from 89 gauges that had valid measurements during the period from February 4–9, 2024. Of these, 33 gauges are operated by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and 56 by the Los Angeles Department of Public Works (LA DPW). USGS data is recorded at 15-minute intervals, while LA DPW data is available at daily intervals for older records and at 15-minute intervals for more recent ones. To maximize the number of valid time series, all data are converted to a daily frequency by averaging the 15-minute intervals over calendar days. To improve the robustness of the statistical analysis, all gauges with records shorter than 20 years are excluded, resulting in a final sample of 71 gauges. Extreme flooding conditions are defined as instances where the daily streamflow during the 5-day period from February 5–9 exceeds the 99th percentile of all non-zero measurements for each gauge.

Data availability

All data used in this study are presented in the main text and are publicly accessible. IMERG precipitation data can be accessed at https://gpm.nasa.gov/data/imerg. Hourly ERA5 data can be downloaded from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels. NCEP Stage IV data can be retrieved from https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/d507005/dataaccess/. OISST daily SST is available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.oisst.v2.highres.html. CENSUS tract shapefiles and demographic data can be downloaded from https://www2.census.gov/geo/tiger/TIGER2023/TRACT/tl_2023_06_tract.zip. USGS streamflow data can be found at https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis/sw, while LA DPW streamflow data be requested by contacting the custodian of hydrologic records, as indicated at https://dpw.lacounty.gov/wrd/runoff/index.cfm. The ARLID code and associated datasets can be accessed at https://github.com/uwincm/arlid. The LPT code is publicly available at https://github.com/brandonwkerns/lpt-python-public, with the corresponding tracking files available at https://orca.atmos.washington.edu/data/lpt/index.html.

References

Zhu, Y. & Newell, R. E. A proposed algorithm for moisture fluxes from atmospheric rivers. Mon. Wea. Rev. 126, 725–735 (1998).

Ralph, F. M., Neiman, P. J., Kiladis, G. N., Weickmann, K. & Reynolds, D. W. A multiscale observational case study of a pacific atmospheric river exhibiting tropical–extratropical connections and a mesoscale frontal wave. Mon. Wea. Rev. 139, 1169–1189 (2011).

Newman, M., Kiladis, G. N., Weickmann, K. M., Ralph, F. M. & Sardeshmukh, P. D. Relative contributions of synoptic and low-frequency eddies to time-mean atmospheric moisture transport, including the role of atmospheric rivers. J. Clim. 25, 7341–7361 (2012).

Neiman, P. J., Ralph, F. M., Wick, G. A., Lundquist, J. D. & Dettinger, M. D. Meteorological characteristics and overland precipitation impacts of atmospheric rivers affecting the west coast of north america based on eight years of SSM/I satellite observations. J. Hydrometeor. 9, 22–47 (2008).

Warner, M. D., Mass, C. F. & Salathé, E. P. Wintertime extreme precipitation events along the Pacific Northwest coast: climatology and synoptic evolution. Mon. Wea. Rev. 140, 2021–2043 (2012).

Vallejo-Bernal, S. M. et al. The role of atmospheric rivers in the distribution of heavy precipitation events over North America. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 27, 2645–2660 (2023).

Stagge, J. H., Torbenson, M. C. A., Sung, K., Phillips, B. & Kingston, D. G. Orographic amplification of El Niño teleconnections on winter precipitation across the intermountain west of North America. Nat. Water 1, 1016–1026 (2023).

Guan, B., Waliser, D. E., Molotch, N. P., Fetzer, E. J. & Neiman, P. J. Does the Madden-Julian oscillation influence wintertime atmospheric rivers and snowpack in the Sierra Nevada?. Mon. Wea. Rev. 140, 325–342 (2012).

Dettinger, M. Climate change, atmospheric rivers, and floods in California – a multimodel analysis of storm frequency and magnitude changes. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 47, 514–523 (2011).

Young, A. M., Skelly, K. T. & Cordeira, J. M. High-impact hydrologic events and atmospheric rivers in California: an investigation using the NCEI storm events database. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 3393–3401 (2017).

Corringham, T. W., Ralph, F. M., Gershunov, A., Cayan, D. R. & Talbot, C. A. Atmospheric rivers drive flood damages in the western United States. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax4631 (2019).

Zhang, C. Madden-Julian Oscillation. Rev. Geophys. 43, (2003).

Chen, S. S., Houze, R. A. Jr. & Mapes, B. E. Multiscale variability of deep convection in relation to large-scale circulation in TOGA COARE. J. Atmos. Sci. 53, 1380–1409 (1996).

Chen, S. S. & Houze, R. A. Diurnal variation and life‐cycle of deep convective systems over the tropical pacific warm pool. Abstr. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 123, 357–388 (1997).

Chen, S. S. & Houze, R. A. Jr. 1997: Interannual variability of deep convection over the tropical warm pool. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 25783–25795 (1997).

Kerns, B. W. & Chen, S. S. Large-scale precipitation tracking and the MJO over the Maritime continent and Indo-Pacific warm pool. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 8755–8776 (2016).

Kerns, B. W. & Chen, S. S. A 20-year climatology of Madden-Julian oscillation convection: large-scale precipitation tracking from TRMM-GPM rainfall. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2019JD032142 (2020).

Wu, C. & Hsu, H. Topographic influence on the MJO in the Maritime Continent. J. Clim. 22, 5433–5448 (2009).

Sobel, A. H., Maloney, E. D., Bellon, G. & Frierson, D. M. Surface fluxes and tropical intraseasonal variability: a reassessment. J. Adv. Mod. Earth Sys. 2, 2 (2010).

Birch, C. E. et al. Scale interactions between the MJO and the western Maritime continent. J. Clim. 29, 2471–2492 (2016).

Savarin, A. & Chen, S. S. Land-locked convection as a barrier to MJO propagation across the Maritime Continent. J. Adv. Mod. Earth Syst. 15, e2022MS003503 (2023).

Payne, A. E. & Magnusdottir, G. Dynamics of landfalling atmospheric rivers over the north pacific in 30 years of MERRA reanalysis. J. Clim. 27, 7133–7150 (2014).

Baggett, C. F., Barnes, E. A., Maloney, E. D. & Mundhnek, B. D. Advancing atmospheric river forecasts into subseasonal-to-seasonal time scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 7528–7536 (2017).

Mundhenk, B. D., Barnes, E. A. & Maloney, E. D. Skillful empirical subseasonal prediction of landfalling atmospheric river activity using the Madden–Julian oscillation and quasi-biennial oscillation. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 20177 (2018).

Zhou, Y., Kim, H. & Waliser, D. E. Atmospheric river lifecycle responses to the Madden-Julian oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090983 (2021).

Toride, K. & Hakim, G. J. Influence of low-frequency PNA variability on MJO teleconnections to North American atmospheric river activity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094078 (2021).

Toride, K. & Hakim, G. J. What distinguishes MJO events associated with atmospheric rivers?. J. Clim. 35, 6135–6149 (2022).

Wheeler, M. C. & Hendon, H. H. An all-season real-time multivariate MJO index: development of an index for onitoring and prediction. Mon. Wea. Rev. 132, 1917–1932 (2004).

Barlow, M. et al. North American extreme precipitation events and related large-scale meteorological patterns: a review of statistical methods, dynamics, modeling, and trends. Clim. Dyn. 53, 6835–6875 (2019).

Prein, A. F., Mooney, P. A. & Done, J. M. The multi-scale interactions of atmospheric phenomenon in mean and extreme precipitation. Earth’s. Future 11, e2023EF003534 (2023).

Kim, S. & Chiang, J. C. H. Atmospheric river lifecycle characteristics shaped by synoptic conditions at genesis. Int. J. Clim. 42, 521–538 (2022).

Guirguis, K. et al. Four atmospheric circulation regimes over the North Pacific and their relationship to California precipitation on daily to seasonal timescales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087609 (2020).

Xiong, Y. & Ren, X. Influences of atmospheric rivers on north pacific winter precipitation: climatology and dependence on ENSO condition. J. Clim. 34, 277–292 (2021).

Madden, R. A. & Julian, P. R. Detection of a 40–50 day oscillation in the zonal wind in the tropical pacific. J. Atmos. Sci. 28, 702–708 (1971).

Madden, R. A. & Julian, P. R. Description of global-scale circulation cells in the tropics with a 40–50 day period. J. Atmos. Sci. 29, 1109–1123 (1972).

Hoskins, B. J. & Karoly, D. J. The steady linear response of a spherical atmosphere to thermal and orographic forcing. J. Atmos. Sci. 38, 1 (1981).

Moore, R. W., Martius, O. & Spengler, T. The modulation of the subtropical and extratropical atmosphere in the Pacific basin in response to the Madden–Julian oscillation. Mon. Wea. Rev. 138, 2761–2779 (2010).

Baxter, S., Weaver, S., Gottschalck, J. & Xue, Y. Pentad Evolution of wintertime impacts of the Madden–Julian oscillation over the contiguous United States. J. Clim. 27, 7356–7367 (2014).

Moon, J. Y., Wang, B. & Ha, K. J. ENSO regulation of MJO teleconnection. Clim. Dyn. 37, 1133–1149 (2011).

Tseng, K., Maloney, E. & Barnes, E. A. The consistency of MJO teleconnection patterns on interannual timescales. J. Clim. 33, 3471–3486 (2020).

Madden, R. A. & Julian, P. R. Observations of the 40–50 day tropical oscillation—a review. Mon. Wea. Rev. 122, 814–837 (1994).

Bosart, L. F., Moore, B. J., Cordeira, J. M. & Archambault, H. M. Interactions of north Pacific tropical, midlatitude, and polar disturbances resulting in linked extreme weather events over North America in October 2007. Mon. Wea. Rev. 145, 1245–1273 (2017).

Torn, R. D. & Hakim, G. J. Comparison of wave packets associated with extratropical transition and winter cyclones. Mon. Wea. Rev. 143, 1782–1803 (2015).

Archambault, H. M., Bosart, L. F., Keyser, D. & Cordeira, J. M. A climatological analysis of the extratropical flow response to recurving western north pacific tropical cyclones. Mon. Wea. Rev. 141, 2325–2346 (2013).

Archambault, H. M., Keyser, D., Bosart, L. F., Davis, C. A. & Cordeira, J. M. A. Composite perspective of the extratropical flow response to recurving western North Pacific tropical cyclones. Mon. Wea. Rev. 143, 1122–1141 (2015).

Grams, C. M., Jones, S. C., Davis, C. A., Harr, P. A. & Weissmann, M. The impact of typhoon Jangmi (2008) on the midlatitude flow. Part I: upper-level ridge building and modification of the jet. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 139, 2148–2164 (2013).

Grams, C. M. & Archambault, H. M. The key role of diabatic outflow in amplifying the midlatitude flow: a representative case study of weather systems surrounding western north Pacific extratropical transition. Mon. Wea. Rev. 144, 3847–3869 (2016).

Winters, A. C., Keyser, D. & Bosart, L. F. The development of the North Pacific jet phase diagram as an objective tool to monitor the state and forecast skill of the upper tropospheric flow pattern. Weather Forecast. 34, 199–219 (2019).

Winters, A. C. Subseasonal prediction of the state and evolution of the North Pacific jet stream. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2021JD035094 (2021).

Bosma, C. D. et al. Extreme rainfall multiplier: an Intuitive metric for tropical cyclone hazards. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 101, 215–220 (2020).

Mazza, E. & Chen, S. S. Tropical cyclone rainfall climatology, extremes, and flooding potential from remote sensing and reanalysis datasets over the continental United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 24, 1549–1562 (2023).

Peng, Q., Xie, S.-P., Passalacqua, G. A., Miyamoto, A. & Deser, C. The 2023 extreme coastal El Niño: atmospheric and air-sea coupling mechanisms. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk8646 (2024).

Tan, W. et al. On the divergent evolution of ENSO after the coastal El Niños in 2017 and 2023. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL108198 (2023).

Wang, B., Chen, G. & Liu, F. Diversity of the Madden-Julian oscillation. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax0220 (2019).

Fink, A. & Speth, P. Some potential forcing mechanisms of the year-to-year variability of the tropical convection and its intraseasonal (25–70 day) variability. Int. J. Climatol. 17, 1513–1534 (1997).

Hendon, H. H., Zhang, C. & Glick, J. D. Interannual Variation of the Madden–Julian Oscillation during Austral summer. J. Clim. 12, 2538–2550 (1999).

Kessler, W. S. EOF representations of the Madden–Julian oscillation and its connection with ENSO. J. Clim. 14, 3055–3061 (2001).

Kim, W., Yeh, S.-W., Kim, J.-H., Kug, J.-S. & Kwon, M. The unique 2009–2010 El Niño event: A fast phase transition of warm pool El Niño to La Niña. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L15809 (2011).

Sanders, F. & Gyakum, J. R. Synoptic-dynamic climatology of the “Bomb. Mon. Weather Rev. 108, 1589–1606 (1980).

Waliser, D. E. & Graham, N. E. Convective cloud systems and warm-pool sea surface temperatures: coupled interactions and self-regulation. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 12881–12893 (1993).

Zhang, C. Large-scale variability of atmospheric deep convection in relation to sea surface temperature in the tropics. J. Clim. 6, 1898–1913 (1993).

Evans, J. L. & Webster, C. C. A variable sea surface temperature threshold for tropical convection. Austr. Meteor. Ocean. J. 64, S1–S8 (2014).

Zhou, W., Yang, D., Xie, S.-P. & Ma, J. Amplified Madden–Julian oscillation impacts in the Pacific–North America region. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 654–660 (2020).

Zhao, M. A study of AR-, TS-, and MCS-associated precipitation and extreme precipitation in present and warmer climates. J. Clim. 35, 479–497 (2022).

Martinez-Villalobos, C. & Neelin, J. D. Regionally high risk increase for precipitation extreme events under global warming. Sci. Rep. 13, 5579 (2023).

Savarin, A. & Chen, S. S. Pathways to better prediction of the MJO: 1. effects of model resolution and moist physics on atmospheric boundary layer and precipitation. J. Adv. Mod. Earth Syst. 14, e2021MS002928 (2022).

Savarin, A. & Chen, S. S. Pathways to better prediction of the MJO: 2. impacts of atmosphere-ocean coupling on the upper ocean and MJO propagation. J. Adv. Mod. Earth Sys. 14, e2021MS002929 (2022).

Huffman, G. et al. Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG), version 4.4. NASA’s Precipitation Processing Center (2014).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the daily optimum interpolation sea surface temperature (DOISST) Version 2.1. J. Clim. 34, 2923–2939 (2020).

Pohorsky, R., Röthlisberger, M., Grams, C. M., Riboldi, J. & Martius, O. The climatological impact of recurving north Atlantic tropical cyclones on downstream extreme precipitation events. Mon. Wea. Rev. 147, 1513–1532 (2019).

Kerns, B. W. & Chen, S. S. Global atmospheric river lifecycle detection using integrated water vapor and vapor transport, Nat. Sci. Data., accepted (2025).

Shearer, E. J. et al. Examination of global midlatitude atmospheric river lifecycles using an object-oriented methodology. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2020JD033425 (2020).

Lin, Y. & Mitchell, K. E. The NCEP Stage II/IV hourly precipitation analyses: development and applications. 19th Conf. Hydrol. 1, 2 (2005).

Xi, D., Lin, N. & Smith, J. Evaluation of a physics-based tropical cyclone rainfall model for risk assessment. J. Hydorometeor. 21, 2197–2218 (2020).

Kerns, B. W. & Chen, S. S. Inland flooding and rainfall from hurricane irene and tropical storm lee (2011): coupled atmosphere–wave–ocean model simulations and remote sensing and in-situ observations with a machine learning tool. Weather Forecast. 38, 677–697 (2023).

Haberlies, A. M. & Ashley, W. S. A radar-based climatology of mesoscale convective systems in the United States. J. Clim. 32, 1591–1606 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Los Angeles County Department of Public Works (LA DPW) for providing quality-controlled stream gauge data for LA County. E.M. and S.S.C. acknowledge support from the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration Climate Variability and Predictability (NOAA CVP) program research grant (NA23OAR4310127) and the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (NOAA PMEL). S.S.C and B.W.K. acknowledge support from the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration Climate Program Office (NOAA CPO) research grant (NA21OAR4310263), the Department of Energy Regional and Global Model Analysis (DOE RGMA) and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (UWPO783373). A.C.W. acknowledges support by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under Award Number DE-SC-0024002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research was conceptualized by E.M., S.S.C., B.W.K., and A.C.W. E.M., B.W.K. and S.S.C. developed the methodology. The investigation and visualization were conducted by E.M. S.S.C., B.W.K., and A.C.W. provided guidance and supervision. The original manuscript was drafted by E.M. and revised and edited by E.M., S.S.C., B.W.K., and A.C.W.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mazza, E., Chen, S.S., Kerns, B.W. et al. Multiscale drivers of extreme southern California flooding: ENSO, MJO, North Pacific jet, and atmospheric rivers. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 376 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01242-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01242-2