Abstract

The Southern Ocean Meridional Overturning Circulation (SO MOC) plays a critical role in redistributing heat, carbon and other tracers globally. Despite its importance, substantial inter-model diversity persists in climate model simulations. This study examines mechanisms underlying such diversity using pre-industrial control simulations from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5/6). We find that discrepancies in the upper overturning cell of SO MOC are primarily governed by model-dependent sensitivity to wind stress, rather than differences in wind stress magnitude. Latitudinal position of maximum zonal wind stress, closely linked to the Southern Annular Mode-like mean state, determines sensitivity through both Eulerian and parameterized eddy-induced circulation. For the lower overturning cell, inter-model differences are largely driven by variations in surface buoyancy fluxes—primarily meltwater—and mean ocean stratification, particularly within key Antarctic Bottom Water formation regions. A mechanistic understanding of SO MOC diversity is essential for improving simulation realism and constraining future climate projections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Southern Ocean (SO) has played a crucial role in heat and carbon uptake throughout the historical period1. Previous studies have indicated that the heat content in the SO constitutes a substantial portion of the increased heat storage in the global ocean2,3. The absorbed heat in the SO is redistributed through Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC), ultimately modifying the amount of heat stored and global patterns of heat storage4,5,6. In particular, changes in the SO MOC influence the reshaping of the global MOC pattern in a warming climate7,8. Furthermore, the heat accumulated in the ocean owing to global warming will eventually escape to specific ocean surfaces, such as the SO, as climate mitigation progresses9. In other words, the MOC, especially the SO MOC, is expected to play a crucial role in redistributing thermal energy in the ocean not only during warming periods but also when mitigation policies are implemented.

The SO MOC consists of two counter-rotating overturning cells, each driven by different formation dynamics10,11,12,13. The upper overturning cell (UC) is mainly controlled by wind stresses and buoyancy fluxes. The prevalent westerly winds over the SO induce northward Ekman transport and upwelling of the upper Circumpolar Deep Water along the isopycnals, while also influencing sea ice coverage14. The upwelled water undergoes subductions over lower latitudes, transforming into Subantarctic Mode Water (SAMW) and Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) owing to wind and buoyancy fluxes. The wind-driven Eulerian mean circulation is partially offset by oceanic eddies, which flatten the isopycnal slopes. The lower overturning cell (LC) is driven by the poleward flow of upwelled lower Circumpolar Deep Water and the formation of Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW). Surface buoyancy loss and brine rejection from sea ice formation transform upwelled warm water into dense AABW at higher latitudes. This dense water then flows northward along the abyssal layers, extending into the extra-tropics of the Northern Hemisphere.

Obtaining observations from the SO is challenging, posing an obstacle to research in this region and highlighting the importance of utilizing coupled ocean-atmosphere global climate models (CGCMs). Additionally, mesoscale eddies play a crucial role in shaping eddy-rich SO circulation. Resolving and permitting eddies in climate models requires a high-resolution grid of 0.25° or finer; however, most coupled models have resolutions lower than that15. Therefore, non-eddy-resolving climate models rely on eddy parameterization16,17,18, which constrains their ability to accurately represent eddy dynamics. Moreover, the unreliable depiction of Antarctic meltwater has a detrimental effect on the accuracy of model simulation19,20,21. These challenges highlight the need for inter-model comparisons and reducing disagreements in model performance to validate SO MOC22.

Previous studies on inter-model comparisons have shown that model biases in wind stress and surface buoyancy fluxes over the SO can lead to biases in the SO MOC23,24,25,26. Furthermore, it has been revealed that incorporating meltwater input from Antarctica increases inter-model diversity in the formation of Antarctic sea ice27, which in turn affects bottom water formation. Extensive inter-model analyses of the factors influencing the SO MOC, such as wind stress and meltwater, have been conducted; however, research specifically focusing on the SO MOC itself remains insufficient. To enhance the accuracy of the SO MOC simulation, it is essential to identify the most prominent inter-model differences. Exploring their diversity and understanding the associated mechanisms can help reduce the bias of the SO MOC, thereby enhancing the reliability of the model simulation.

In this study, we examine the dominant inter-model differences in the SO MOC by using pre-industrial control simulations to evaluate the intrinsic climate processes of each model under fixed external forcing. We find that the inter-model differences in UC intensity are more sensitive to the latitudinal position of the maximum zonal wind stress than to its magnitude, whereas LC intensity is influenced by both surface buoyancy flux and mean ocean stratification. This analysis highlights the importance of understanding model-dependent variations in the mean state as a critical step toward improving the simulation of overturning cells and their roles in the global climate system.

Results

Dominant discrepancy in the mean SO MOC

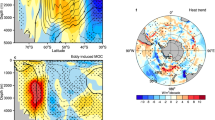

The SO MOC in the observation-based reanalysis dataset (Fig. 1a) (see Methods) shows two-cell structures, where the positive values (i.e., clockwise circulation) correspond to the UC, whereas the negative ones (counterclockwise rotation) represent the LC. The multi-model mean pattern of the SO MOC closely resembles that of the reanalysis data, as shown by the contour lines. Although the periods analyzed in these two datasets do not match, the results indicate that the climate models comprehensively capture the SO MOC. The pattern of multi-model standard deviation illustrates a deviation of up to 13 Sv (\(1{\rm{Sv}}\equiv {10}^{6}{{\rm{m}}}^{3}{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\)) from the multi-model mean, with a pronounced feature in the UC region (Fig. 1b).

a Oceanic meridional mass streamfunction in the southern extra-tropics calculated from GLORYS12V1 data (averaged from 1993 to 2016) (shading). b Multi-model standard deviation (shading) of meridional mass streamfunction; the black arrows indicate the direction of circulation. The inner and outer circles near the surface indicate the multi-model and zonally averaged maximum eastward zonal wind stress. c First EOF pattern in inter-model space (shading) explaining 54.3% of the total inter-model variance and d First PC in terms of climate models. Each model is represented by a unique marker, with its color and shape corresponding to the name of the model as shown in the bar graph. The contour lines in (a–c) show the multi-model mean streamfunction with annotated values, and the thicker line corresponds to zero streamfunction.

To identify the dominant pattern of inter-model diversity, we first apply an Empirical Orthogonal Function (EOF) analysis to the time-mean meridional mass streamfunctions (Supplementary Fig. 1) in the inter-model dimension. The first EOF mode (EOF1) accounts for 54.3% of the total variance (Fig. 1c, d). The other two leading EOF modes (Supplementary Fig. 2) explain a relatively small portion of the total inter-model variance (28.9% and 6.6% for the second and third modes, respectively); therefore, we focus mainly on the first EOF mode. Hereafter, EOF1 and the first principal component (PC1) referenced in this study refer to the first inter-model EOF and PC of SO MOC, respectively. The EOF1 pattern resembles the multi-model mean with a strong emphasis on the UC region, suggesting that prominent inter-model discrepancies are related to UC strength.

To evaluate the representativeness of EOF1 in capturing the inter-model diversity of the mean circulation, a linear regression of each circulation index (see Methods) against PC1 is computed. The intensity of UC, which shows significant inter-model variation ranging from a minimum of approximately 25 Sv to a maximum of approximately 45 Sv, is strongly positively correlated with PC1 (Fig. 2a). In addition, the latitudinal position of the UC, varying from 51°S to 46°S, is partially explained by PC1 (Fig. 2b). However, the intensity of the LC shows no significant correlation with PC1 but is instead associated with PC2 (Fig. 2c, d). In summary, the models with positive PC1 have strong and equatorward-shifted UC, whereas the negative PC1 models exhibit the opposite. Instead, LC diversity is explained by PC2.

Simple linear regression line and multi-model scatter plot of a UC intensity, b UC location, and c LC intensity onto PC1, respectively. d Same as in c but onto PC2. Each marker corresponds to a specific climate model as indicated in Fig. 1. The correlation coefficient and p-value for each regression are displayed in the upper right corner of each panel. The correlation coefficient in (a), (b), and (d) are significant at a 99% confidence level by Student’s t-test. The green circles on y-axis in all panels correspond to the value from GLORYS12V1.

Factors driving inter-model diversity of the SO MOC

To investigate the underlying mechanisms of EOF1, time-mean wind stress and sea level pressure (SLP) in multi-model ensemble fields are regressed onto PC1 at each grid point to produce spatial regression map (Fig. 3). The results show that a stronger SO MOC (i.e., positive PC1) is associated with enhanced westerly wind stress around 40°S and weakened westerly wind stress around 65°S, referring to the relative equatorward shift of the wind stress pattern. Additionally, the regressed SLP pattern is aligned with the typical negative Southern Annular Mode (SAM). SAM is a leading mode of atmospheric variability in the extratropical Southern Hemisphere and is associated with the position and strength of the polar jet28,29,30. The regressed SLP implies that positive PC1 models exhibit a negative SAM-like mean state corresponding to a northward-shifted weaker polar jet, whereas the negative PC1 models correspond to a positive SAM-like mean state corresponding to a southward-shifted stronger polar jet, explaining the inter-model differences in the UC location.

Vectors and dotted areas indicate regions where regression coefficients are statistically significant at a 95% confidence level (Students’ t-test) and the corresponding correlation coefficients exceed 0.4. Purple contour lines represent multi-model mean zonal wind stress values greater than 0.1 Nm−2.

The relationship between wind forcing and ocean circulation can be understood through residual-mean theory of ref. 31, which describes how wind-driven changes in isopycnal slopes affect the overturning circulation. According to this framework, the total overturning circulation \((\Psi )\) is composed of the Eulerian-mean overturning (\(\bar{\Psi }=-\tau /({\rho }_{0}f)\), where \(\tau\) is zonal wind stress, \({\rho }_{0}\) is reference density, and f is Coriolis parameter) and the eddy-induced overturning (\({\Psi }^{* }=K{S}_{\rho }\), where K is eddy diffusivity and \({S}_{\rho }\) is isopycnal slope). While mesoscale eddies act to partially compensate for wind-driven circulation changes by restoring isopycnal slopes (a process known as eddy compensation), the degree of compensation is incomplete, allowing the Eulerian-mean component to dominate the total circulation response15,32. Since this component responds directly to wind stress changes, all models consistently demonstrate a significant correlation between the annual-mean time series of UC intensity and the maximum zonal wind stress (Supplementary Fig. 3). Here, the maximum zonal wind stress refers to the highest zonal-mean wind stress value observed between 65°S and 30°S. The robust relationship in all models suggests that this fundamental mechanism operates reliably across different model configurations, although the specific sensitivity varies among models. Furthermore, when the same approach applied to the monthly-mean data, instead of annual-mean data, the results support the robustness of annual-mean sensitivity metric (Supplementary Table. 1). However, inter-model relationship between the time-mean maximum zonal wind stress and time-mean UC intensity does not persist (Fig. 4a), indicating that a model simulating stronger maximum zonal wind stress does not necessarily produce a stronger UC, and vice versa. Rather than wind stress magnitude, UC intensity correlates more strongly with each model’s sensitivity to wind stress changes. Figure 4b clearly demonstrates that the sensitivity is significantly correlated with UC intensity across models. Here, we quantify each model’s sensitivity as the linear regression coefficient between annual-mean UC intensity and maximum zonal wind stress. The latitudinal position of the maximum wind stress partly explains this relationship. Models with more equatorward wind stress exhibit higher sensitivity (Fig. 4c). This behavior is consistent with the Eulerian-mean component scaling (\(\partial \bar{\Psi }/\partial \tau \propto -1/f\)), where sensitivity to wind stress perturbations scales inversely with the Coriolis parameter—lower latitudes (smaller |f|) exhibit higher sensitivity. Our inter-model analysis confirms this theoretical expectation.

Linear regression line and multi-model scatter plot of (a) mean UC intensity onto mean maximum zonal wind stress, b mean UC intensity onto sensitivity parameter, and c sensitivity onto the latitude of maximum zonal wind stress. Each marker corresponds to a specific climate model as indicated in Fig. 1. The correlation coefficient and p-value for each regression are displayed in the upper right corner of each panel. The correlation coefficients in b, c are significant at a 99% confidence level by Student’s t-test.

While the Eulerian scaling explains the general relationship, previous studies have reported that the SO MOC response to wind forcing depends critically on how mesoscale eddies are represented in models, given their role in modulating the overturning response32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. Since mesoscale eddies are not resolved in most CMIP models, eddy activities need to be parameterized. The parameterization schemes vary across models, particularly in how the eddy diffusivity is prescribed—whether as a constant or as a spatially and temporally varying field—as well as in its magnitude22,40. These differences can affect the eddy-driven circulation and, along with variations in isopycnal slopes, may contribute to the inter-model spread in sensitivity. Although eddy diffusivity is explicitly documented for some models, the spatial or temporal variation complicates a rigorous inter-model comparison. In this context, we analyze the mean isopycnal slope to investigate its role in shaping the inter-model diversity of the eddy-induced overturning circulation. In the residual-mean framework, the eddy diffusivity K is assumed to be proportional to the isopycnal slope (\(K=k|{S}_{\rho }|\), where k is positive scaling constant), which implies a quadratic dependence of eddy-induced streamfunction on slope (\({\Psi }^{* }\propto {S}_{\rho }|{S}_{\rho }|\)). We examine this relationship across 15 models that provide eddy-induced streamfunction data and find a significant relationship with \({S}_{\rho }|{S}_{\rho }|\) (Supplementary Fig. 4a), suggesting that theoretical relationship offers a useful reference. However, since K prescriptions differ among models, this quadratic relationship cannot be universally assumed. We therefore also analyze the simpler \({\Psi }^{* }-{S}_{\rho }\) relationship, which serves as a robust diagnostic of inter-model differences without requiring assumptions about K (Supplementary Fig. 4b). While previous study emphasized diffusivity differences across models41, our results highlight that isopycnal slope is readily observable metric for understanding inter-model diversity in eddy-driven circulation, offering a complementary perspective to diffusivity-based analysis. The isopycnal slope is influenced by the latitudinal position of the maximum zonal wind stress: poleward wind maxima generate stronger surface divergence and steeper slopes, while equatorward positions produce less steep slopes (Supplementary Fig. 4c). The resulting weaker eddy-driven circulation due to flatter isopycnal slopes leads to stronger sensitivity parameters. Thus, the latitude of maximum wind stress influences both Eulerian-mean and eddy-driven components, explaining the inter-model diversity in UC intensity. In summary, negative (positive) SAM-like mean state in the positive (negative) PC1 models contributes to an equatorward (poleward) shifted UC, resulting in stronger (weaker) UC due to enhanced (reduced) 1/f scaling and reduced (enhanced) eddy compensation.

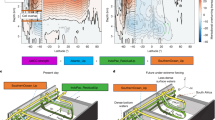

While inter-model differences in UC intensity are primarily captured by EOF1, differences in LC intensity are more strongly associated with EOF2 (Fig. 2d). It is well known that AABW, which constitutes a part of the LC, forms over the Weddell Sea, Ross Sea, and Adélie Land42, and many coupled models have simulated AABW over these regions43,44,45. The source of AABW is surface buoyancy loss, primarily driven by freshwater fluxes, due to brine rejection during sea ice formation46,47,48,49 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Given the importance of the surface buoyancy flux in AABW formation, the regression of the LC intensity on the surface buoyancy flux is calculated to assess the inter-model relationship. The results show significant regression coefficients over the deep convection regions, including the Weddell and Ross seas, suggesting that climate models with greater buoyancy flux over these areas tend to simulate weaker AABW (Fig. 5a). Further analysis of the respective contributions from surface freshwater and heat fluxes reveals that the inter-model regression pattern of the surface buoyancy flux is primarily driven by the freshwater component (Fig. 6a, b). The subsequent decomposition of the freshwater flux into meltwater from sea ice and net precipitation (precipitation minus evaporation) indicates that the meltwater plays a dominant role in shaping the regression pattern (Fig. 6c, d).

a LC intensity regressed onto surface buoyancy flux, with coefficients scaled by the standard deviation of surface buoyancy flux so that the units correspond to those of LC intensity. b LC intensity regressed onto Brunt–Väisälä frequency squared (N²) integrated vertically from 1500 to 2000m depth, with coefficients similarly scaled by the standard deviation of N². The dotted areas indicate regions where regression coefficients are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (Student’s t-test) and corresponding correlation coefficients exceed 0.4. Positive buoyancy flux corresponds to a net gain of buoyancy by the ocean.

LC intensity regressed onto (a) surface freshwater flux, b surface heat flux, and the freshwater components of c meltwater and d precipitation minus evaporation. Regression coefficients are scaled by the standard deviation of each variable. Dotted areas indicate where regression coefficients are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (Student’s t-test) and corresponding correlation coefficients exceed 0.4. Positive buoyancy flux corresponds to a net gain of buoyancy by the ocean.

Although the variation in surface buoyancy flux is a key driver of AABW changes, inter-model differences in the mean state of ocean stratification can induce distinct vertical motions, thereby contributing to the diversity of LC across models. Inter-model contrasts in surface buoyancy flux contribute to differences in the density structure and may partly explain the variability in upper-ocean stratification. However, discrepancies in deep-ocean stratification are likely attributable to model-specific configurations such as mixing parameterization (including diapycnal diffusivity) and geometry50,51. To further examine the role of oceanic stratification, the square of Brunt-Väisälä frequency (N2), or buoyancy frequency, is calculated for each model. The vertical profile of the LC intensity regressed on the area-averaged N2 over deep convection regions (Weddell and Ross Sea) indicates that weak AABW is associated with strong stratification, particularly below 1500 m depth (Supplementary Fig. 6). The regression map of LC intensity onto N2 integrated over 1500–2000 m depth also reveals a negative relationship in the marginal regions, including deep convection areas (Fig. 5b). These results suggest that model simulations of AABW formation differ across models depending on the mean states of both surface buoyancy flux and oceanic stratification.

Impact of model diversity in SO MOC

To investigate the ocean temperature associated with the inter-model diversity of the SO MOC, we regress time-mean sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies—obtained by removing the global mean within each individual model—onto UC intensity across the multi-model ensemble (Fig. 7a). UC intensity is chosen as it captures the dominant mode from inter-model EOF analysis (highly correlated with PC1, r = 0.93). A significant meridional contrast pattern of SST, such as warmer around 60°S and cooler SST at lower latitudes, is observed. The SST pattern is explained by the regression of zonally averaged ocean potential temperature, which is regressed onto UC intensity at each latitude-depth grid (Fig. 7b). In the models with strong UC, meridional cold advection intensified along the strong northward streamlines near the surface, inducing colder SST over the range of 60–40°S. Warming in the deeper layer within the same latitudinal band can be understood as the result of intense downward motion, which transports warmer surface water into the deeper ocean. Similarly, the SST over 70–60°S becomes warmer owing to the strong upwelling of Circumpolar Deep Water. Atmospheric processes may also contribute to the formation of SST patterns. For example, during a negative SAM phase, adiabatic warming occurs in the troposphere through downward vertical motion over the poleward side, whereas upward motion induces adiabatic cooling at lower latitudes. Although it is difficult to separately quantify the effects of the SO MOC and atmospheric vertical motion, both effects cannot be overlooked.

Regression coefficient maps of a global mean-removed sea surface temperature and b zonal-averaged ocean potential temperature against UC intensity. Contour lines in b indicate the overturning streamfunction of the multi-model mean. The dotted areas indicate regions where regression coefficients are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (Student’s t-test) and corresponding correlation coefficients exceed 0.4.

Discussion

In this study, we examine the discrepancies in the SO MOC across CGCMs. The dominant pattern identified by the inter-model EOF analysis of the meridional mass streamfunction highlights inconsistencies in the model simulations, particularly regarding the intensity and positioning of the UC. The inter-model differences in the SO MOC are categorized into distinct groups, each characterized by different phases of the SAM-like mean state. In positive PC1 models with a negative SAM-like mean state, the northward-shifted wind stresses cause the maximum zonal wind stress to occur at lower latitudes, resulting in an equatorward-shift of UC and an increase in its sensitivity. This UC strengthening occurs through increased sensitivity to wind stress at lower latitudes, which results from both stronger Eulerian-mean responses and weaker eddy compensation. Thus, the latitudinal position of maximum zonal wind stress plays a more significant role in determining UC intensity than the wind stress magnitude. While PC1 primarily represents the inter-model diversity of UC, PC2 captures that of LC. The LC discrepancy in multi-model simulations is closely correlated with the surface buoyancy flux over the Weddell and Ross Seas which drives bottom water formation. Beyond the known role of the surface buoyancy flux, we find that differences in mean state of deep ocean stratification across models are also significantly associated with LC intensity.

While we propose that the latitudinal position of maximum zonal wind stress influences UC intensity through the eddy-induced streamfunction, this conclusion is constrained by the limited number of models available for analysis. Therefore, an investigation with a larger number of models is required to generalize our finding. Additionally, while our study focuses on the role of parameterized diffusivity and isopycnal slope in shaping mesoscale eddy effects, recent studies indicate that the sensitivity of ocean circulation to wind stress also depends on other factors, such as diapycnal mixing processes and topographic modulation of eddy-mean flow interactions52,53,54,55,56. For more comprehensive understanding of inter-model diversity in SO MOC, it would be beneficial to integrate these processes along with detailed information on model-specific eddy diffusivity. Regarding LC, inter-model differences in intensity reflect variations in surface buoyancy flux and oceanic stratification, as well as how AABW is represented. Some models simulate AABW formation more realistically by including Antarctic shelf processes44,57, whereas many still rely on open-ocean deep convection, which is less accurate in representing bottom water properties. The ref. 44 also suggested that to improve the accuracy of AABW simulations, it is necessary to adopt overflow parameterization58, which transports dense shelf water to deeper layers, and to integrate interactive ice sheet models.

This study aims to compare the mean state of the SO MOC across various coupled models. To explore the intrinsic properties without external forcing, the analysis focuses primarily on pre-industrial control simulations, which are generally assumed to have reached an equilibrium state. Interdependence among climate elements complicates causal explanations, making it challenging to determine the leading or following relationships between variables. Nevertheless, we propose the following mechanism: a higher sensitivity of the SO MOC response to wind stress forcing (i.e., positive PC1 models) promotes a stronger UC. This intensification induces a north-south dipole-like SST pattern through dynamical thermal advection. This dipole-like pattern, reducing the meridional SST gradient between two latitudinal bands, reduces westerly over high latitude. This is further supported by Supplementary Fig. 7, which shows that models with the largest meridional SST gradient at lower latitudes also exhibit equatorward-positioned maximum zonal wind stress. A significant inter-model correlation (0.49) improves to 0.65 when removing one outlier model, INM-CM5-0, indicating a clearer inter-model relationship between SST patterns and wind stress positioning. Consequently, the maximum core of the mean westerly polar jet moved north, reinforcing the UC. Previous studies have demonstrated that most climate models in control experiments exhibit biases in the wind field over the SO, characterized by weak and equatorward-shifted wind stress23,59. Even if model diversity in wind stress did not initially exist, it can be hypothesized that the feedback process, as mentioned above, ultimately resulted in model discrepancies in wind stress, which, in turn, influenced the overturning circulation. This reinforcing relationship acts as a mechanism that maintains model diversity in overturning cells. While the proposed feedback requires further validation, understanding such coupled processes is essential for improving climate model fidelity. Our results provide important insights into the correction of model bias in the SO MOC and hold the potential for developing an emergent constraint on future SO MOC projections.

Methods

Data

To obtain the reanalysis-based meridional mass streamfunction, we utilize the CMEMS global ocean eddy-resolving (1/12° horizontal resolution, 50 vertical levels) reanalysis (GLORYS12V160), which covers the period from 1993 to 2016. To examine the inconsistencies in the SO MOC across different CGCMs, we used 29 models: 19 models participating in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase6 (CMIP6)61 and 10 models from CMIP562 (Table 1). We analyze the pre-industrial control simulation to understand the mean state of the SO MOC, excluding anthropogenic forcing. The oceanic meridional mass streamfunction variables (“msftmz” or “msftyz”) are used as an indicator to assess MOC. These variables include all advective mass transport processes, including parameterized mesoscale advection. The meridional overturning circulation in depth coordinate is represented by the following formula63:

where \({v}^{\dagger }\) is the meridional mean velocity (Eulerian plus parameterized bolus component), z(s) denotes the depth of surface s for depth-coordinate streamfunctions, and the zonal integral is over longitude \({x}_{a}\) to \({x}_{b}\). To examine the eddy-induced component of the overturning circulation, we used variables “msftmzmpa” or “msftyzmpa”. The models are selected based on the availability of the mass streamfunction variables.

Inter-model Empirical Orthogonal Functions

Empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis is applied to assess systematic differences in the model simulations64. We initially average the time dimension of the oceanic meridional mass streamfunction within the range of the SO MOC (75–30°S) and compute the deviation of each model from the multi-model mean. The variable, constructed with 29 models, is then applied to the EOF analysis, which identifies independent spatial patterns in the inter-model deviation. Each EOF mode is a linear combination of model deviations, and captures the dominant inter-model structural differences, rather than individual model circulation structures or temporal variability. This approach systematically identifies which aspects of circulation representation contribute most to inter-model differences.

Definition of circulation index

To estimate the relevant circulation characteristics, we define several indices that provide information on circulation intensity and location. In this study, the index for UC intensity is defined as the maximum streamfunction in the top 500 m between 65°S and 30°S. The 500 m is chosen to reflect the strongest signals in the upper ocean associated with wind-driven mechanisms. The latitude of the maximum streamfunction is then used as an index of the UC location, serving as an indicator of its meridional position. This latitude index is particularly useful for comparing spatial variations in UC across different models. The meridional streamfunction due to parameterized mesoscale eddies is used to understand the role of eddy compensation, based on data from 15 models that provide this variable. To approximate the eddy-driven circulation theoretically, isopycnal slope (\({S}_{\rho }\)) is defined as the ratio of the meridional to vertical gradient of the time- and zonal-mean buoyancy field (\({S}_{\rho }=-{\bar{b}}_{y}/{\bar{b}}_{z},\) where \(\bar{b}\) is a mean buoyancy). The slope is spatially averaged over the region corresponding to wind-driven UC (upper 500 m and 65–30°S) to obtain the mean isopycnal slope. The LC intensity is examined in the context of the AABW formation. Thus, it is defined as the absolute value of the minimum streamfunction in the 0–4500 m depth range south of 55°S rather than the abyssal circulation extending into the northern hemisphere. To avoid issues arising from different resolutions across models, the horizontal grids are interpolated to the same resolution for all models.

Computation of surface buoyancy flux

The surface buoyancy flux (B; m2 ∙ s−3) is calculated as the sum of heat flux (\({{\rm{B}}}_{{\rm{h}}}\)) and freshwater flux (\({{\rm{B}}}_{{\rm{f}}}\)) components. The haline buoyancy flux is given by:

where g is gravitational acceleration, \({{\rm{\rho }}}_{0}\) is the reference seawater density, β is haline contraction coefficient, \({{\rm{S}}}_{0}\) is sea surface salinity, and QF(kg∙m−2 ∙ s−1) is net freshwater flux. Net freshwater flux contains the effects of net precipitation (precipitation minus evaporation), liquid water runoff, sea ice formation/melting and icebergs (if included in CMIP model)63. The thermal buoyancy flux is given by:

where α is the thermal expansion coefficient, QH(W ∙ m−2) is net surface heat flux, and cp is the specific heat of seawater.

Computation of oceanic Brunt-Väisälä frequency

The square of Brunt-Väisälä frequency (N2) is calculated using TEOS-10 software toolbox65 based on the equation below:

where S, T, P and ρ denote absolute salinity, conservative temperature, pressure, and potential density, respectively; g, α, and β are as previously defined.

Data Availability

All data are publicly available from the following repositories: GLORYS12V1 from https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00021 and CMIP 5/6 from https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/.

References

Frölicher, T. L. et al. Dominance of the Southern Ocean in Anthropogenic Carbon and Heat Uptake in CMIP5 Models. J. Clim. 28, 862–886 (2015).

Durack, P. J., Gleckler, P. J., Landerer, F. W. & Taylor, K. E. Quantifying underestimates of long-term upper-ocean warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 999–1005 (2014).

Roemmich, D. et al. Unabated planetary warming and its ocean structure since 2006. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 240–245 (2015).

Winton, M., Griffies, S. M., Samuels, B. L., Sarmiento, J. L. & Frölicher, T. L. Connecting Changing Ocean Circulation with Changing Climate. J. Clim. 26, 2268–2278 (2013).

Liu, W., Lu, J., Xie, S.-P. & Fedorov, A. Southern Ocean Heat Uptake, Redistribution, and Storage in a Warming Climate: The Role of Meridional Overturning Circulation. J. Clim. 31, 4727–4743 (2018).

Li, Q., Luo, Y., Lu, J. & Liu, F. The Role of Ocean Circulation in Southern Ocean Heat Uptake, Transport, and Storage Response to Quadrupled CO2. J. Clim. 35, 7165–7182 (2022).

Lee, S.-K. et al. Human-induced changes in the global meridional overturning circulation are emerging from the Southern Ocean. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 69 (2023).

Baker, J. A. et al. Continued Atlantic overturning circulation even under climate extremes. Nature 638, 987–994 (2025).

Oh, J.-H. et al. Emergent climate change patterns originating from deep ocean warming in climate mitigation scenarios. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 260–266 (2024).

Marshall, J. & Speer, K. Closure of the meridional overturning circulation through Southern Ocean upwelling. Nat. Geosci. 5, 171–180 (2012).

Cai, W. et al. Southern Ocean warming and its climatic impacts. Sci. Bull. 68, 946–960 (2023).

Bennetts, L. G. et al. Closing the Loops on Southern Ocean Dynamics: From the Circumpolar Current to Ice Shelves and From Bottom Mixing to Surface Waves. Rev. Geophys. 62, e2022RG000781 (2024).

Song, H., Choi, Y., Doddridge, E. W. & Marshall, J. The Responses of Antarctic Sea Ice and Overturning Cells to Meridional Wind Forcing. J. Clim. 38, 701–716 (2025).

Purich, A., Cai, W., England, M. H. & Cowan, T. Evidence for link between modelled trends in Antarctic sea ice and underestimated westerly wind changes. Nat. Commun. 7, 10409 (2016).

Gent, P. R. Effects of Southern Hemisphere Wind Changes on the Meridional Overturning Circulation in Ocean Models. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 8, 79–94 (2016).

Redi, M. H. Oceanic Isopycnal Mixing by Coordinate Rotation. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 12, 1154–1158 (1982).

Gent, P. R. & Mcwilliams, J. C. Isopycnal Mixing in Ocean Circulation Models. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 20, 150–155 (1990).

Gent, P. R., Willebrand, J., McDougall, T. J. & McWilliams, J. C. Parameterizing Eddy-Induced Tracer Transports in Ocean Circulation Models. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 25, 463–474 (1995).

Pauling, A. G., Bitz, C. M., Smith, I. J. & Langhorne, P. J. The Response of the Southern Ocean and Antarctic Sea Ice to Freshwater from Ice Shelves in an Earth System Model. J. Clim. 29, 1655–1672 (2016).

Siahaan, A. et al. The Antarctic contribution to 21st-century sea-level rise predicted by the UK Earth System Model with an interactive ice sheet. Cryosphere 16, 4053–4086 (2022).

Purich, A. & England, M. H. Projected Impacts of Antarctic Meltwater Anomalies over the Twenty-First Century. J. Clim. 36, 2703–2719 (2023).

Beadling, R. L. et al. Representation of Southern Ocean Properties across Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Generations: CMIP3 to CMIP6. J. Clim. 33, 6555–6581 (2020).

Russell, J. L., Stouffer, R. J. & Dixon, K. W. Intercomparison of the Southern Ocean Circulations in IPCC Coupled Model Control Simulations. J. Clim. 19, 4560–4575 (2006).

Beadling, R. L., Russell, J. L., Stouffer, R. J., Goodman, P. J. & Mazloff, M. Assessing the Quality of Southern Ocean Circulation in CMIP5 AOGCM and Earth System Model Simulations. J. Clim. 32, 5915–5940 (2019).

Lin, X., Zhai, X., Wang, Z. & Munday, D. R. Southern Ocean Wind Stress in CMIP5 Models: Role of Wind Fluctuations. J. Clim. 33, 1209–1226 (2020).

Downes, S. M. & Hogg, A. McC. Southern Ocean Circulation and Eddy Compensation in CMIP5 Models. J. Clim. 26, 7198–7220 (2013).

Bronselaer, B. et al. Change in future climate due to Antarctic meltwater. Nature 564, 53–58 (2018).

Ferreira, D., Marshall, J., Bitz, C. M., Solomon, S. & Plumb, A. Antarctic Ocean and Sea Ice Response to Ozone Depletion: A Two-Time-Scale Problem. J. Clim. 28, 1206–1226 (2015).

Fogt, R. L. & Marshall, G. J. The Southern Annular Mode: Variability, trends, and climate impacts across the Southern Hemisphere. WIREs Clim. Change 11, e652 (2020).

Williams, R. S. et al. Future Antarctic Climate: Storylines of Midlatitude Jet Strengthening and Shift Emergent from CMIP6. J. Clim. 37, 2157–2178 (2024).

Marshall, J. & Radko, T. Residual-Mean Solutions for the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and Its Associated Overturning Circulation. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 33, 2341–2354 (2003).

Zhai, X. & Munday, D. R. Sensitivity of Southern Ocean overturning to wind stress changes: Role of surface restoring time scales. Ocean Model. 84, 12–25 (2014).

Hallberg, R. & Gnanadesikan, A. The Role of Eddies in Determining the Structure and Response of the Wind-Driven Southern Hemisphere Overturning: Results from the Modeling Eddies in the Southern Ocean (MESO) Project. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 36, 2232–2252 (2006).

Viebahn, J. & Eden, C. Towards the impact of eddies on the response of the Southern Ocean to climate change. Ocean Model. 34, 150–165 (2010).

Lauderdale, J. M., Garabato, A. C. N., Oliver, K. I. C., Follows, M. J. & Williams, R. G. Wind-driven changes in Southern Ocean residual circulation, ocean carbon reservoirs and atmospheric CO2. Clim. Dyn. 41, 2145–2164 (2013).

Abernathey, R., Marshall, J. & Ferreira, D. The Dependence of Southern Ocean Meridional Overturning on Wind Stress. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 41, 2261–2278 (2011).

Munday, D. R. & Zhai, X. The impact of atmospheric storminess on the sensitivity of Southern Ocean circulation to wind stress changes. Ocean Model. 115, 14–26 (2017).

Meredith, M. P., Naveira Garabato, A. C., Hogg, A., McC & Farneti, R. Sensitivity of the Overturning Circulation in the Southern Ocean to Decadal Changes in Wind Forcing. J. Clim. 25, 99–110 (2012).

Downes, S. M., Spence, P. & Hogg, A. M. Understanding variability of the Southern Ocean overturning circulation in CORE-II models. Ocean Model. 123, 98–109 (2018).

Meijers, A. J. S. The Southern Ocean in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 372, 20130296 (2014).

Kuhlbrodt, T., Smith, R. S., Wang, Z. & Gregory, J. M. The influence of eddy parameterizations on the transport of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current in coupled climate models. Ocean Model. 52–53, 1–8 (2012).

Meredith, M. P. Replenishing the abyss. Nat. Geosci. 6, 166–167 (2013).

De Lavergne, C., Palter, J. B., Galbraith, E. D., Bernardello, R. & Marinov, I. Cessation of deep convection in the open Southern Ocean under anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 278–282 (2014).

Heuzé, C. Antarctic Bottom Water and North Atlantic Deep Water in CMIP6 models. Ocean Sci. 17, 59–90 (2021).

Moon, J.-Y. et al. Antarctic meltwater spread pattern and its duration modulate abyssal circulation. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 586 (2025).

Snow, K., Hogg, A. M.cC., Sloyan, B. M. & Downes, S. M. Sensitivity of Antarctic Bottom Water to Changes in Surface Buoyancy Fluxes. J. Clim. 29, 313–330 (2016).

Pellichero, V., Sallée, J.-B., Chapman, C. C. & Downes, S. M. The southern ocean meridional overturning in the sea-ice sector is driven by freshwater fluxes. Nat. Commun. 9, 1789 (2018).

Zhou, S. et al. Slowdown of Antarctic Bottom Water export driven by climatic wind and sea-ice changes. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 701–709 (2023).

Abernathey, R. P. et al. Water-mass transformation by sea ice in the upper branch of the Southern Ocean overturning. Nat. Geosci. 9, 596–601 (2016).

Vallis, G. K. Large-Scale Circulation and Production of Stratification: Effects of Wind, Geometry, and Diffusion. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 30, 933–954 (2000).

Stewart, A. L., Ferrari, R. & Thompson, A. F. On the Importance of Surface Forcing in Conceptual Models of the Deep Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 44, 891–899 (2014).

Abernathey, R. & Cessi, P. Topographic Enhancement of Eddy Efficiency in Baroclinic Equilibration. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 44, 2107–2126 (2014).

Mackay, N. et al. Diapycnal Mixing in the Southern Ocean Diagnosed Using the DIMES Tracer and Realistic Velocity Fields. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 123, 2615–2634 (2018).

Kong, H. & Jansen, M. F. The Impact of Topography and Eddy Parameterization on the Simulated Southern Ocean Circulation Response to Changes in Surface Wind Stress. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 51, 825–843 (2021).

Cai, Y., Chen, D., Mazloff, M. R., Lian, T. & Liu, X. Topographic Modulation of the Wind Stress Impact on Eddy Activity in the Southern Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, (2022).

Yang, L., Nikurashin, M., Hogg, A. McC. & Sloyan, B. M. Lee Waves Break Eddy Saturation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50 (2023).

Heuzé, C., Heywood, K. J., Stevens, D. P. & Ridley, J. K. Southern Ocean bottom water characteristics in CMIP5 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1409–1414 (2013).

Snow, K. et al. Sensitivity of abyssal water masses to overflow parameterisations. Ocean Model. 89, 84–103 (2015).

Sen Gupta, A. et al. Projected Changes to the Southern Hemisphere Ocean and Sea Ice in the IPCC AR4 Climate Models. J. Clim. 22, 3047–3078 (2009).

European Union-Copernicus Marine Service. Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis. Mercator Ocean International https://doi.org/10.48670/MOI-00021 (2018).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An Overview of CMIP5 and the Experiment Design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

Griffies, S. M. et al. OMIP contribution to CMIP6: experimental and diagnosticprotocol for the physical component of the Ocean Model Intercomparison Project. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3231–3296 (2016).

Ham, Y.-G. & Kug, J.-S. Improvement of ENSO Simulation Based on Intermodel Diversity. J. Clim. 28, 998–1015 (2015).

McDougall, T. J. & Barker, P. M. Getting Started with TEOS-10 and the Gibbs Seawater (GSW) Oceanographic Toolbox. (Trevor J McDougall, Battery Point, Tas., 2011).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00208000), and by Yonsei Signature Research Cluster Program of 2025 (2025-22-0242). S.I.A. was supported by the Yonsei Fellowship, funded by Lee Youn Jae.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.E.P. and S.I.A. wrote the main manuscript text and S.E.P. prepared all figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, SE., An, SI., Song, H. et al. Inter-model diversity and Its Drivers in Southern Ocean Meridional Overturning Circulation. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01258-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01258-8