Abstract

The remote influences of springtime Third Pole (TP) snow cover (TPSC) on the Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM) and the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM) have been extensively studied. However, a clear mechanism explaining the cross-season links remains not well established. Before we confirm any remote effects, it is essential to first verify local influences. Here, we bear out the enduring local impact of the springtime TPSC according to a numerical experiment together with an observational investigation. By examining the evolution of underlying heat sources, we propose a self-sustaining mechanism elucidating the enduring local impact: considering the case of the springtime TPSC deficit, the excessive precipitation that initially responds to the enhanced surface heat and water fluxes releases extra atmospheric latent heat, which in turn drives an anomalous circulation favoring the next-coming precipitation. This finding adds credit to the cross-season influences of the springtime TPSC remotely on the ISM and the EASM. Furthermore, our work implicates that the TP may get more summer precipitation in a warmer future since there will be an inevitable decrease in springtime TPSC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Snow is a cryospheric component in the climate system playing a critical role in regulating global temperatures, water cycles, and ecosystems1,2,3. Due to high surface albedo, thermal emissivity and ground-insulating properties, and large latent heat for phase change, snow exerts stark local effect via modulating surface mass and energy balance. This becomes especially plain when coming to the Third Pole (TP) region, where the snow cover is shallow, patchy, and often short-lived, exhibiting prominent spatial heterogeneity and temporal variability4,5,6,7. Snow influences the climate not only locally but also remotely via atmospheric teleconnection. In fact, the remote effect, rather than the local impact, of the TP’s snow cover (TPSC) receives extensive and intensive focus from the research community. Back in 1884, Blanford8 first suggests a negative relationship between the Himalayan winter snow accumulation and the subsequent summer rainfall over India, of which the responsible mechanism is that the surface thermal characteristics of the high Asian mountains influence the onset of the Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM). Thanks to more observation becoming available and the emergence of numerical models, a large number of studies9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 re-examine the so-called Blanford hypothesis. In recent decades, the “downstream effect” of the anomalous TPSC on the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM) and its associated precipitation has also been widely discussed19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. In addition, studies32,33,34,35,36 even report remote responses to the TPSC forcing in atmospheric circulations or surface variables in regions other than the surrounding areas.

Despite being extensively studied37, a clear mechanism for the remote effect of the varying TPSC remains not well established. The Blanford hypothesis for the relationship between the TPSC and the ISM sometimes, but not always, receives support from the subsequent studies9,10,11,12,13,14, with some climate indices such as the prominent El Niño Southern Oscillation possibly being responsible for the contrary15,16,17,18. Likewise, the connection between the TPSC and the EASM seems to be controlled by a complex regime, which differs from region to region under the EASM influence20,27 and is also affected by the spatial patterns of the TPSC anomalies21,29,38. Moreover, this connection may be disrupted by a decadal climate shift24,31, challenging the TPSC to be a robust predictor of summer rainfall in downstream regions. It is argued that snow cover can only cause a short-term decrease in local surface temperature39,40. Indeed, considering the atmosphere’s fast mixing time scale, one should first and foremost prove the existence of the necessary memory effect that maintains the cross-season links. Soil moisture may have longer memory than atmosphere does, and has therefore been suggested to play the role bridging the springtime TPSC anomalies and the variability in summer monsoons18,41,42,43, referred to as the so-called snow-hydrology effect10,19,44. However, it could hardly be a univocal explanation considering that, as noted by ref. 19, there are contrary effects on atmospheric stability and local water cycle regarding favoring precipitation. Moreover, few studies have focused on the local cross-season impact of the TPSC. Naturally, a proper and straightforward strategy is to test the cross-season impact locally before we confirm any remote effect.

In this study, we have our eyes on the enduring local impact of the TPSC. By employing a numerical experiment as well as an analysis upon state-of-the-art data of snow and precipitation for the Third Pole region, we test if there is a relationship between the springtime TPSC and the summer precipitation over the TP. Next, we explore the possible mechanism that sustains the memory of springtime heating/cooling by the anomalous TPSC into summer. This can improve our understanding on the predictability of precipitation over the TP, which is a vital input of the Asia’s Water Tower feeding billions of people downstream. On top of that, as pronounced above, this mechanism is also essential to bridge the forcing of cold-season TPSC and the cross-season responses in remote regions.

Results

The springtime TPSC’s enduring local impact

Our numerical experiment includes two cases, one represents the “snow-rich” scenario and the other the “snow-deficient”; please refer to Supplementary Fig. S1 for the difference of days with snow cover between the two cases, and Section Methods for the details of the experiment design. The month-to-month evolution of the difference between the two snow cover scenarios for several variables (Fig. 1) is investigated to examine the effect caused by the anomalous TPSC and also its persistence. Our investigation starts from precipitation (Fig. 1a), showing that the springtime TPSC deficit results in an excessive precipitation over the TP throughout the simulation period from March to August, supporting the existence of enduring local impact of the TPSC. The precipitation excess peaks in April and maintains at the same level, if in terms of the absolute amount, in May and goes weaker in summer. Reflected in the spatial pattern, the precipitation excess predominates over almost the entire TP region during the spring season while becomes more chaotic in summer, with some broken areas occupied by precipitation loss indicating that the impact of the springtime TPSC deficit is no longer strong.

The spatial distribution of the monthly difference between the two model scenarios ("snow-deficient” − “snow-rich'') from March to August for precipitation (a), vertically integrated moisture divergence (b), geopotential at 200 hPa (c) and 500 hPa (d), and updraft helicity (e). The vertical profile of the regionally-averaged difference over the TP for vertical velocity (f) and air temperature (g). The white contour in c, d marks the TP region with elevations higher than 3000 m. For each subplot in a–e, the number given is the weighted average for the TP region.

Understanding what drives the precipitation difference is essential for uncovering the underlying mechanism for the persistence of the springtime TPSC’s local impact. Precipitation occurs as a consequence of a series of complex processes, impacted by several interconnected factors, among which atmospheric precipitable water, or more directly its convergence, is a vital one influencing precipitation by providing the necessary moisture source. Figure 1b presents the month-to-month evolution of difference in vertically integrated moisture divergence (with negative values indicating convergence). We can see the similarity in spatial pattern between the simulated difference in precipitation and that in moisture divergence, apart from the fact that the latter has a larger magnitude in June and July. The developing of the negative spatial correlation coefficients with time (from −0.4 to −0.8) reveals that moisture processes become more and more dominant in summer precipitation that responds to the springtime TPSC’s forcing (Supplementary Table S1).

It is then necessary to examine the changes in atmospheric circulation, as it transports water vapor and generates flow convergence or divergence, favoring or disfavoring precipitation. Figure 1c, d gives the difference between the “snow-deficient” and “snow-rich” scenarios for geopotential at 200 hPa and 500 hPa, representing the response in atmospheric circulation for the upper and lower troposphere over the TP, respectively. It clearly shows that the springtime TPSC deficit leads to an enhanced high in the upper troposphere, accompanied by a deepened low in the lower troposphere over the TP throughout the simulation period, though the enhancement goes weaker in summer. This vertical setup favors aforementioned moisture convergence considering water vapor concentrated mainly in the lower troposphere. On the other hand, to compensate the divergence in the upper troposphere, it also introduces an upward motion of air parcels which uplifts water vapor to form cloud droplets, serving as another crucial factor for precipitation. Therefore, we next examine the response to the TPSC deficit in vertical motion. Updraft helicity reduces a three-dimensional wind field into one number, and is used as a forecast parameter to identify rotating updrafts45. Here we relate it to dynamic contribution within the lower to middle troposphere considering its importance for convection. Similarly to the case for moisture divergence, the difference between the two model scenarios in updraft helicity (Fig. 1e) shows resembling spatial pattern as that in precipitation (Fig. 1a), with the spatial correlation coefficients, compared to those between moisture divergence and precipitation, however somewhat lower in magnitude (in the range of 0.3 to 0.4), and exhibiting no clear development with time (Supplementary Table S1). Besides the spatial similarity, another observation worth to be mentioned is that the intensity of updraft helicity difference experiences an evolution opposite to moisture divergence difference while similar to geopotential difference, showing a decline in magnitude from spring to summer, suggesting that upward motion rather than moisture plays a dominant role in spring precipitation difference that responds to the springtime TPSC’s forcing.

The month-to-month evolution of the vertical profile of regional mean over the TP is also investigated for the difference in vertical velocity and in air temperature, as presented in Fig. 1f, g. The springtime TPSC deficit leads to an upward anomaly in vertical velocity throughout the pressure levels in troposphere over the TP, which persists until the end of summer, albeit with a decline trend in intensity. This is in coherence with the above finding regarding updraft helicity. Detailed in the vertical profile, the strongest anomalous upward motion occurs approximately at levels in the middle troposphere in spring while levels upper in summer. Upward motion as well as the associated geopotential setup can usually be related to the diabatic heating. Indeed, in response to the springtime TPSC deficit, an upward displacement from March to August of the levels where maximum warming occurs, which are somewhat lower to those for the difference in vertical velocity, can be observed. This indicates that the underlying heat sources associated with the TPSC’s forcing may change with time.

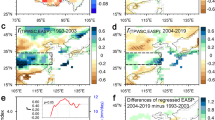

For now, it is yet unknown if the simulated enduring local impact of the springtime TPSC can be detected in the real world. Aiming for such an investigation, we select a set of observational data taking into account the quality (see Section Methods for the details). Based on a remote sensing-rooted snow dataset, we identify “snow-deficient” years and those “snow-rich” (refer to Supplementary Fig. S2 for the difference of days with snow water equivalent over 10 kg m−2 between the two groups). We do observe that the “snow-deficient” years show more precipitation in summer than the “snow-rich” years do (Fig. 2a), in general consistent with the model results, apart from the fact that the observed precipitation difference experiences a somewhat contrasting evolution and exhibits dissimilar spatial pattern compared to the model results, with the positive anomaly going apparent in summer and mainly distributed in the western TP (Figs. 2a and 1a). The simulated association between the difference in precipitation and that in moisture divergence is also clearly observed in the observational investigation (Fig. 2a, b). Further, in the “snow-deficient” years, an enhanced high for geopotential in the upper troposphere occurs in all spring-summer months other than April (Fig. 2c), with the body of the enhancement not fully geographically corresponding to the TP though. We do not see a deepened low in the lower troposphere like for the model results (Fig. 2d), but the spatial pattern of the 500-hPa geopotential anomaly shows that the TP, especially the south-western part, has relatively lower values w.r.t. surrounding areas. This, together with the stronger signal in the upper troposphere, which seems to dominate the anomalous circulation, favors the moisture convergent and in turn the precipitation. For atmospheric heating, the “snow-deficient” years show a positive anomaly in air temperature, of which the maximum occurs initially at levels close to the TP’s surface in March and goes upper where above the middle troposphere in summer (Fig. 2e), again, generally in agreement with the model results (Fig. 1f). In a word, we do have detected the enduring local impact of the springtime TPSC in the observational data, though its specifics become somewhat complicated from the simulation to the real world, which will be discussed later.

The spatial distribution of the monthly difference between the “snow-deficient” years and the “snow-rich” years from March to August for precipitation (a), vertically integrated moisture divergence (b), and geopotential at 200 hPa (c) and 500 hPa (d). e The vertical profile of the regionally-averaged difference over the TP for air temperature. The white contour in c, d marks the TP region with elevations higher than 3000 m. The two numbers given in the top-left area of each subplot in a–d are the weighted averages for the entire TP region and its western part (west to 90 °E), respectively.

The evolution of associate heat sources

As previously stated, the underlying heat sources are responsible for the enduring local impact of the TPSC. Therefore, we examine the associated heat sources and their evolution with time based on the numerical experiment, as presented in Fig. 3.

The spatial distribution of the monthly difference between the two model scenarios ("snow-deficient” − “snow-rich'') from March to August for surface sensible heat flux (HFX; a) and surface latent heat flux (LH; b). The vertical profile of the regionally-averaged difference over the TP for apparent heat source (Q1; c) and apparent moisture sink (Q2; d). For each subplot in a, b, the number given is the weighted average for the TP region.

Having the property of high albedo, snow cover reduces surface net solar radiation causing the ground surface to be cooler, thereby cooling the near-surface atmosphere through negative (downward) sensible heat flux (HFX). Inversely, the springtime TPSC deficit yields upward anomaly of surface HFX (Fig. 3a). The change in heating rate is related closely to the extent and duration of anomalous snow cover (Supplementary Fig. S1), and to the change in surface absorbed solar radiation as well (Supplementary Fig. S3a). According to our numerical experiment, the difference in surface HFX between the “snow-deficient” and “snow-rich” scenarios has its largest value over 25 W m−2 in March, which decreases to ~16 W m−2 in April and is further halved in May, becoming negligible in summer finally. Obviously, the heat source associated with the surface HFX only persists in the cold season when there is a major existence of snow cover over the TP; nevertheless, it can hardly sustain the local impact of the springtime TPSC till the summer season.

The cold surface of snow cover can, meanwhile, suppress evaporation. Thus, an increase in surface latent heat flux (LH) is expected in response to the springtime TPSC deficit, as shown in Fig. 3b. The anomalous surface LH experiences an evolution somewhat differently from the anomaly in surface HFX, having strongest effect close to 17 W m−2 in later spring and continuing to function with a rate ~9 W m−2 in June. The excessive surface LH moistens the lower atmosphere, promoting the local water cycle. This is especially true for the later spring when the LH difference is manifest, as further supported by the relatively higher spatial correlation coefficient between the difference in precipitation and that in surface LH for April and May (Supplementary Table S1). Although the effect causing anomalous evaporation persists longer than the that directly heating the lower atmosphere, it fails to explain the enduring local impact of the springtime TPSC in later summer considering its small magnitudes (Fig. 3b). Moreover, the excessive surface LH means the part of energy from the surroundings absorbed for the increased evaporation, which causes cooling on the surface and the air above it. From the perspective of surface energy balance, it consumes part of absorbed solar radiation (Supplementary Fig. S3a) reducing the remaining part available for HFX (Fig. 3a). This effect, however, makes atmosphere stabler and thereby disfavors precipitation, diminishing the positive contribution through providing water vapor.

The vertical structure of the change in air temperature provides a hint for the evolution of the underlying heat sources associated with the TPSC’s forcing. Here we propose that the heat sources sustaining the local impact of the TPSC till summer are situated in the atmosphere rather than on the surface, for we see an upward displacement with time of the maximum warming levels in response to the springtime TPSC deficit in both the numerical experiment (Fig. 1g) and the observational investigation (Fig. 2e). To further verify the detailed atmospheric heat sources associated with the springtime TPSC deficit and their evolution, we investigate the apparent heat source (Q1) and the apparent moisture sink (Q2) with our model results, as presented in Fig. 3c, d.

Q1 represents the total atmospheric diabatic heating, which consists of the heating due to radiation, the release of atmospheric LH by net condensation, and vertical convergence of the eddy transport of sensible heat46. According to our numerical experiment, the springtime TPSC deficit results into negative Q1 anomaly almost across the tropospheric levels, except for a few layers in the lower atmosphere since April. The negative Q1 anomaly experiences a decline in its magnitude, having the strongest intensity at the initial status and vanishing finally in the end of summer.

The negative sign of the Q1 anomaly is somewhat counter-intuitive, since the initial surface forcing is the upward HFX anomaly (Fig. 3a) due to the excess in surface absorbed solar radiation (Supplementary Fig. S3a). We suggest that the negative Q1 anomaly is contributed by the radiative cooling due to the increase in cloud amount, which produces the excessive precipitation (Fig. 1a). The vertical structure of negative Q1 anomaly is to some extent resembling to that of vertical velocity (Fig. 1f), supporting our suggestion in view of the fact that upward motion is critical for cloud forming. In fact, we investigate the difference between the two model scenarios for various variables relating to radiation (Supplementary Fig. S3) to further verify this point. The increase in cloud amount, on one hand, decreases outgoing longwave radiation at top of atmosphere (TOA) due to the low cloud-top temperature (Supplementary Fig. S3e); on the other hand, it elevates the planetary albedo reflecting more solar radiation to the space and less input into the Earth system. It is unfortunately not able to examine the difference in outgoing solar radiation at TOA, which, not as a standard historic variable in the model, is not outputted. Nevertheless, the reduced downward shortwave radiation at surface (Supplementary Fig. S3c) corroborates the fact of less incoming solar radiation at TOA. Moreover, the degraded surface albedo leads to increased absorbed solar radiation (i.e., less reflected going to the atmosphere), of which only a part is used to heating the atmosphere through the upward HFX anomaly (Fig. 3a) with the remaining part mainly consumed as surface LH (Fig. 3b) not going back to the atmosphere. To wrap up the above results, the springtime TPSC deficit degrades the surface albedo but elevates the planetary albedo, leading to less input of shortwave radiation from both the surface and TOA (i.e., radiative cooling) and majorly explain the negative Q1 anomaly. The increased downward longwave radiation (Supplementary Fig. S3d), which can be attributed to the moistened and warming troposphere (Fig. 1h), is balanced by the rise in upward longwave radiation due to the surface warming. In consequence, it exhibits small values in net surface longwave radiation (Supplementary Fig. S3b), thereby giving limited contribution to the atmospheric radiative cooling.

The Q1 anomaly associated with the springtime TPSC deficit, with the negative sign, may explain the overall decline trend in the difference of air temperature between the “snow-deficient” and “snow-rich” scenarios (Fig. 1h). The atmospheric heat sources able to sustain the enduring local impact of the springtime TPSC deficit are however required to have positive heating rate anomaly persisting even till later summer. According to our numerical experiment, the Q2 is such one having continuing positive heating rate anomaly, mainly located in the middle troposphere, throughout the simulation period from spring to summer (Fig. 3d). Being a measure of the apparent heat sink which is due to the net condensation and vertical divergence of the eddy transport of moisture46, the Q2 is expected to closely correlated with the precipitation. We indeed see a month-to-month evolution of the Q2 anomaly (Fig. 3d) highly in line with that of precipitation (Fig. 1a).

The aforementioned simulated signals in Q1 and Q2 associated with the springtime TPSC’s forcing are also detected in our observational investigation, as shown in Fig. 4. It exhibits the difference between the “snow-deficient” years and those “snow-rich” generally negative for Q1 and positive for Q2, in agreement with the results from our numerical experiments, apart from some specific details in the vertical structure or in the evolution (e.g., being positive across the tropospheric levels in March and slightly positive in the middle troposphere from April to July for Q1). The association between Q2 and precipitation is also apparent in our observational investigation, with the positive Q2 anomaly for the “snow-deficient” years becoming stronger in summer (Fig. 4b) in correspondence to the larger excess in precipitation (Fig. 2a).

Discussion

With the results from our numerical experiments and observational investigation, we confirm the enduring local impact of the springtime TPSC and have the basic idea about the evolution of the associated underlying heat sources. Integrating all the information, we are now able to figure out the mechanism explaining the enduring local impact of the springtime TPSC, as illustrated by Fig. 5. Here, we describe the mechanism for the case of the springtime TPSC deficit; reversed anomalies are expected for the case of rich springtime TPSC.

The evolution of the intensity for surface sensible heat flux, surface water flux, and the release of atmospheric latent heat is denoted by the changing icon size from left (earlier spring) to right (later summer). For the case of rich springtime TPSC, the arrows and signs in the diagram are expected to be reversed.

In earlier spring, the TPSC deficit leads into lower surface albedo, and thereby the ground surface becomes warmer as it absorbs more solar radiation. The increase in HFX due to the warmer ground surface provides the critical initial forcing, which drives an anomalous circulation configured by a divergence and a convergence in the upper and lower troposphere, respectively, promoting upward motion and favoring cloud forming and precipitation. The surface heating effect, mainly determined by the extent and duration of anomalous TPSC, declines with time during the melting season and vanishes in summer. The warmer ground surface, meanwhile, increases evaporation (i.e., the water flux in Fig. 5), promoting local water cycle. Compared to the surface heating, the promoting effect via water flux is however, not so straightforward but moderated, as it, on the other hand, consumes part of energy from surroundings (i.e., the surface LH) causing the atmosphere stabler. The effect via both surface HFX and water flux is referred to as the snow-albedo effect10,19,44, of which, according to our numerical experiment, the later seems to be lagging behind the former continuing to function in earlier summer. The snow-albedo effect persists mainly in the cold season, though, hardly maintaining the local impact in summer. This somewhat supports the argument that snow cover can only cause a short-term direct effect39,40. Indeed, an examination detailed into the simulated day-to-day evolution (Supplementary Fig. S4) reveals the response to surface forcing in atmosphere, especially in terms of atmospheric warming, to be apparent at medium-range time scales (shorter than 2 weeks), which has been also reported by a previous study47.

Our investigation suggests that it is Q2 which sustains the local impact of the springtime TPSC till summer. The Q2, mainly contributed by the release of atmospheric latent heat, is closely related to the precipitation amount; therefore, it works as a self-sustaining mechanism: the excessive precipitation that initially responds to the snow-albedo effect (i.e., the enhanced surface heat and water fluxes) releases more atmospheric LH, which in turn drives an anomalous circulation favoring the next-coming precipitation (Fig. 5). Actually, it has been reported that almost three-fourths of the energy that drives the atmospheric wind circulation comes from the LH released by precipitation for tropical regions48,49,50,51. The summer atmospheric LH over the south-eastern TP associated with the spring surface SH has also been suggested to partly underpin the time-lagged impact on the summer rainfall anomaly in East China52. Here, we propose that this self-sustaining mechanism is responsible for the enduring local impact of the springtime TPSC, considering the following two facts: i) the upward displacement with time of the maximum warming levels in response to the springtime TPSC deficit found in both the numerical experiment (Fig. 1g) and the observational investigation (Fig. 2e), indicating that the driving energy comes from atmospheric heat sources rather than those at surface; and ii) the positive Q2 anomaly located in the middle troposphere almost throughout the period from spring to summer (Figs. 3d and 4b). By applying a linear baroclinic model (LBM)53, we examine the response in atmospheric circulation to heating near-surface and that in the middle troposphere over the TP, which are represented by steady temperature forcing with the vertical profile in a Γ shape centered at σ level of 0.90 and 0.45, respectively. The LBM simulation results (Supplementary Figs. S5 and 6) reveal that the heating at both the two different levels can lead to an similar anomalous circulation with an enhanced high in geopotential at upper troposphere and an upward anomaly in vertical motion across all the tropospheric levels also over the TP, which is to be steady at approximately Day 7. This confirms that the self-sustaining mechanism works over the TP. Nevertheless, the fate of the local impact of the springtime TPSC is to vanish in the end of summer despite the existence of self-sustaining mechanism. This is because the springtime TPSC deficit elevates the planetary albedo through increasing cloud amount, together with the degraded surface albedo, resulting in radiative cooling and a negative Q1 anomaly in total.

Owing to the low surface temperatures at high latitudes, evaporation rate over the TP is expected to be relatively small until the peak monsoon month, implying a long memory for soil moisture there. The anomalous TPSC is then assumes to be able to influence the weather in summer through snow-melt deposit into the soil, i.e., the snow-hydrology effect10,19,44. As we already stated, there is competition between the cooling effect and the contribution of moisture associated with evaporation, of which the former suppresses, whereas the latter promotes precipitation. Therefore, the sign of snow-hydrology effect may depend on which of the two opposite effects dominates. Our numerical experiment is unfortunately not able to test the snow-hydrology effect, because the difference status of TPSC between the two cases originates from the different schemes for snow albedo representation. Nevertheless, we tend to argue that the snow-hydrology effect is limited, considering not only the aforementioned competition of opposite effects via energy and water but also the fact that the removal of TPSC could be through sublimating rather than melting due to the dry environment. In addition to the snow-hydrology effect, anomalies of summertime snow cover over the western TP are suggested to be responsible for influencing the EASM26,29,54. However, its significance might be challenged considering the small variability of limited summertime snow cover over the western TP. Moreover, the regional difference in the springtime TPSC anomalies has also been suspected to determine the cross-season impact, while the current study only takes the TP as a whole. Further studies are yet needed to clarify these possible mechanisms mentioned here.

The data quality is crucial for the observational investigation influencing the validity. It has been reported that a huge overestimation of snow depth over the TP even exists recent global reanalysis products including the ERA5 (as the 5th generation of reanalysis) from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF)55, which is likely linked to delayed ablation56. Therefore, we use a state-of-the-art snow dataset, which is produced using a physics-based snowpack model and a snow radiative transfer model combined with remote sensing data (See the Section “Methods” for details), rather than the snow data directly provided by reanalysis products. The dataset covers from August 2002 to July 2022. According to our identification, each group of “snow-deficient” years and those “snow-rich” consists only 3 years, meaning that it hardly fully excludes the signature of factors other than the springtime TPSC’s forcing in the difference between the two groups that represent different status of springtime TPSC. Variabilities in westerlies, Indian monsoon, and teleconnection patterns are documented to influence the precipitation pattens and other climate agencies over the TP57,58,59,60,61,62,63. Such factors could be responsible for some mismatches between our observational investigation and numerical experiment, such as the opposite signal in precipitation anomaly over the eastern TP (Fig. 2a) and the “disruption” for impact on geopotential and atmospheric warming in April (Fig. 2c–e). In fact, we do not really expect fully matching results from the observational investigation and numerical experiment, as they do not even exactly share the same springtime TPSC’s forcing (Supplementary Figs. S1 and 2). On the contrary, we are encouraged by their general agreement, though not for every detail, in revealing the enduring local impact and associated heat sources of the springtime TPSC’s forcing.

The numerical experiment may outperform the observational investigation in controlling the influencing factor, and is thereby expected to more clearly identify underlying mechanisms. Fundamentally as a sensitivity experiment designed to isolate and examine the mechanistic link between springtime TPSC and subsequent local summer precipitation, rather than to quantify climatological statistics, our carefully controlled model setup (e.g., contrasting snow-albedo parameterizations) allow us to confidently attribute the simulated responses to the springtime TPSC’s forcing even within a single-year framework. This approach aligns with established practices in climate sensitivity studies47,52, where mechanistic clarity often takes precedence over multi-year replication. According to a recent study64, in which a 10-year simulation has been conducted, the simulated responses to change of surface albedo actually remain consistent across different years, supporting our single-year approach to be valid and sufficient. However, we fully acknowledge that an extension of the simulations to more years will potentially enhance the statistical significance of our results. Future work could indeed expand on this foundation by incorporating multi-year experiments–a direction we enthusiastically endorse.

The mechanism proposed in this study, as illustrated by Fig. 5, elucidates the enduring local impact of the springtime TPSC, which adds credit to the cross-season influence on the ISM, EASM, and even atmospheric circulations over other regions remotely. Future studies taking one step further (e.g., using a global climate model) are however, necessary to confirm the cross-season remote effect of the TPSC. Furthermore, the mechanism proposed also implicate that the TP may get more summer precipitation in a warmer future since there will be an inevitable decrease in springtime snow cover.

Methods

Design of the numerical experiment

The numerical model used here is the Advanced Weather Research and Forecasting Model (WRF-ARW, version 4.0) developed by the National Center for Atmosphere Research (NCAR)65. Featuring state-of-the-art numeric and comprehensive physical parameterizations, the WRF-ARW is suitable for simulating across a variety of horizontal and vertical scales, and has been successfully applied in our previous studies focusing on the TP region for mechanistic clarity66,67,68. Aiming a better model physics representation for the TP, we employ a special version of the WRF-ARW with Noah-MP69 as the land surface model, to which a series of improvements have been introduced. Specifically, a turbulent orographic form drag scheme is applied to account for the dynamic effect of unresolved sub-grid topographic variance70,71; a new soil texture dataset72 plus stony surface identification from remote sensing73 and a parameterization for the soil organic content are set up to accurately represent soil thermal and hydraulic processes; and, a new thermal roughness parameterization for bare ground74,75 is used targeting a better simulation of surface turbulent heat flux.

Most importantly, to specify the two scenarios of “snow-rich” and “snow-deficient” for the springtime TPSC, we do not choose to modify the initial snow but apply different options regarding the representation of snow albedo and snow cover fraction to yield opposite snow status on surface, by which we can smoothly avoid violating physical balance in the forcing data. One option is the default for the WRF-ARW: the CLASS scheme76 plus original parameterization of snow cover fraction. The other is a newly developed one77: a snow albedo scheme taking into account snow ageing and contamination of ground albedo for shallow snow7 plus a revision of snow cover fraction parameterization considering the orographic effect78. In a general sense, the new option tends to pull down the overestimated snow albedo for the TP region where the terrain is complex and the snow cover is observed to be shallow, patchy, and often short-lived4,5,6. Thus, model cases with the default option and the new one stand for the scenarios of “snow-rich” and “snow-deficient”, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). The differences between the two cases’ simulation results thereby indicate responses to the anomalous TPSC.

The two model cases share all the other model configuration. Physics options include the Dudhia scheme79 and RRTM80 for shortwave and longwave radiation transfer, respectively, the new Thompson microphysics81, the University of Washington moist turbulence parameterization for boundary layer82 together with representation for shallow convection83, and the Grell-Freitas improved cumulus scheme84. The model domain is specified at 500 (west–east) ×300 (south–east) grids with 0.09°spacing, and is centered at 36°N and 85°E. There are 38 levels in vertical direction. The simulation is run from 1st January to 31st August 2018, with days before 1st March treated as the “spin-up” time. The ERA5 reanalysis from the ECMWF85 provides the initial and hourly lateral boundary condition for the model.

Data for the observational investigation

In addition to the numerical experiment which isolates and examines the cross-season impact of the springtime TPSC’s forcing, composite analysis using observational data reveals real-world behaviors and is necessary to be incorporated here. As argued by ref. 4, the controversy on the Blanford hypothesis is mainly due to the lack of snow data of high quality over the TP. It has been reported that the current global reanalysis products including the ERA5 fail to provide valid snow depth55,56, which are thereby beyond our consideration. A state-of-the-art dataset of multiple snow parameters for the Tibetan Plateau86, which has a spatial resolution of 3 km and covers from August 2002 to July 2022, is used to appropriately identify “snow-rich” years and those “snow-deficient”. The dataset is produced from snow ensembles simulated by a physical-based snowpack model named SNTHERM87 coupled with a microwave emission model of layered snowpack88. The snow simulation is driven by multi-sourced meteorological forcing and constrained by a NASA’s Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer-based daily fractional snow cover product for the Asia Water Tower region89. Among the various snow parameters available in the dataset, we use water equivalent. To identify the “snow-rich” years and those “snow-deficient”, we calculate the regional average over the TP for days in March with snow water equivalent over 10 kg m−2, and then find those years with value outside one standard deviation from the multiyear mean.

The precipitation data used for the observational investigation are from the dataset for the TP region called TPHiPr90, which has a resolution of 1/30° and covers the period from 1979 to present. The TPHiPr is produced by merging the numerical simulation-based ERA5_CNN91 with gauge observations from more than 9000 rain gauges. The validation demonstrates that the TPHiPr outperforms those widely-used precipitation datasets including the ERA5 reanalysis.

The monthly data for vertically integrated moisture divergence, geopotential, air temperature, specific humidity, horizontal velocity, and vertical p-velocity from the ERA5 are used in this study, considering the fact that these variables benefit largely, in the aspect of reliability, from the data assimilation utilized in producing the reanalysis85.

Validation of the numerical simulations

A simple validation of the simulations has been especially carried out for monthly precipitation and snow water equivalent, by comparing with the TPHiPr and the aforementioned remote sensing-based snow dataset, respectively, as presented in Supplementary Fig. S7. It shows that the model reasonably reproduces the spatial pattern and temporal evolution of the observed precipitation and snow, though the “wet bias” that commonly exists in current climate models for the TP region66,92 can be still seen, indicating that the WRF-ARW model is a valid tool for the numerical experiment.

Calculation of updraft helicity

Updraft helicity (UH) reduces a three-dimensional wind field into one number and is considered a useful forecast parameter to identify rotating updrafts45. In this study, we relate it to the dynamic contribution for the springtime TPSC’s impact on local precipitation. Specifically, UH is calculated using the following formula

where w is the vertical velocity, and ζ the vertical component of the relative vorticity. Here, z0 and zt are set to 2 and 5 km AGL, respectively.

Calculation of Q 1 and Q 2

The apparent heat source Q1 and the apparent moisture sink Q246 are calculated from

and

where θ is the potential temperature, q the mixing ratio of water vapor, V the horizontal velocity, ω the vertical p-velocity, p the pressure, and ∇ the isobaric gradient operator. In Eq. (2), κ = R/Cp, R and Cp are, respectively, the gas constant and the specific heat at constant pressure of dry air, p0 = 1000 hPa; in Eq. (3), L is the latent heat of condensation.

For the WRF-ARW simulations, Q1 and Q2 are calculated at the daily interval. The monthly mean for Q1 and Q2, as presented in Fig. 3c, d, is then derived from the daily values. For the observational investigation, Q1 and Q2 presented in Fig. 4 are directly calculated from the monthly data provided by the ERA5 reanalysis. In order to take account for the eddy transport of sensible heat and moisture, theoretically, the short temporal interval is required for calculating the two diagnoses. At the monthly scale, however, the two approaches (mean from the daily derivation and the derivation directly from monthly data) show almost identical results according to our test on the model output, consoling the direct comparison between Fig. 3c, d and Fig. 4.

Spatial correlation

In Supplementary Table S1, the Pearson correlation coefficient is used to quantify the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables along corresponding grid points, i.e., the spatial correlation. The statistically significance test for the the spatial correlation is based on the two-sided Student’s t-test.

Examination of steady response with LBM

The numerical package for LBM53 is built up in order to examine a linear dynamics in the atmosphere. The results from a LBM simulation would be much easily interpreted, considering that the dynamical framework is simplified in the LBM compared to fully non-linear climate models. Here, we use it to examine the steady response in atmosphere to different heat sources over the TP. We conduct two experiments, among which one has the steady temperature forcing over the TP specified with a vertical profile in a Γ shape centered at σ level of 0.90 and the other 0.45, where a maximum of 2 K warming located. The former forcing represents the heating near-surface, while the latter in the middle troposphere. Horizontally, the temperature forcing has an elliptic shape centered at 33°N 90°E with zonal and meridional radius of 35°and 15°, respectively. The LBM simulation is conducted for 30 days at horizontal resolution of T21 and 20 vertical levels, with the basic state being summer climatology.

Data availability

The dataset of multiple snow parameters for the Tibetan Plateau is available at https://doi.org/10.11888/Cryos.tpdc.301588. The TPHiPr dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.11888/Atmos.tpdc.272763. The ERA5 reanalysis can be assessed via Climate Data Store (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets; registration required).

Code availability

Data processing techniques are available on request from C.L. (linchanggui@nssc.ac.cn).

References

Barnett, T. P., Dümenil, L., Schlese, U. & Roeckner, E. The effect of Eurasian snow cover on global climate. Science 239, 504–507 (1988).

Cohen, J. Snow cover and climate. Weather 49, 150–156 (1994).

Henderson, G. R., Peings, Y., Furtado, J. C. & Kushner, P. J. Snow–atmosphere coupling in the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 954–963 (2018).

Qin, D., Liu, S. & Li, P. Snow cover distribution, variability, and response to climate change in western China. J. Clim. 19, 1820–1833 (2006).

Ueno, K., Tanaka, K., Tsutsui, H. & Li, M. Snow cover conditions in the Tibetan Plateau observed during the winter of 2003/2004. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 39, 152–164 (2007).

Che, T., Li, X., Jin, R., Armstrong, R. & Zhang, T. Snow depth derived from passive microwave remote-sensing data in China. Ann. Glaciol. 49, 145–154 (2008).

Wang, W. et al. Characterizing surface albedo of shallow fresh snow and its importance for snow ablation on the interior of the Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrometeorol. 21, 815–827 (2020).

Blanford, H. F. On the connexion of the Himalaya snowfall with dry winds and seasons of drought in India. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 37, 3–22 (1884).

Walker, G. R. Correlations in seasonal variations of weather II. Mem. Indian Meteorol. Dep. 21, 22–45 (1910).

Hahn, D. G. & Shukla, J. An apparent relationship between Eurasian snow cover and Indian monsoon rainfall. J. Atmos. Sci. 33, 2461–2462 (1976).

Dey, B. & Kumar, O. S. R. U. B. Himalayan winter snow cover area and summer monsoon rainfall over India. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 88, 5471–5474 (1983).

Zwiers, F. W. Simulation of the Asian Summer Monsoon with the CCC GCM-1. J. Clim. 6, 469–486 (1993).

Kripalani, R. H., Kulkarni, A. & Sabade, S. S. Western Himalayan snow cover and Indian monsoon rainfall: A re-examination with INSAT and NCEP/NCAR data. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 74, 1–18 (2003).

Robock, A., Mu, M., Vinnikov, K. & Robinson, D. Land surface conditions over Eurasia and Indian summer monsoon rainfall. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4131 (2003).

Fasullo, J. A stratified diagnosis of the Indian Monsoon-Eurasian snow cover relationship. J. Clim. 17, 1110–1122 (2004).

Zhao, H. & Moore, G. W. K. On the relationship between Tibetan snow cover, the Tibetan plateau monsoon and the Indian summer monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L14204 (2004).

Senan, R. et al. Impact of springtime Himalayan–Tibetan Plateau snowpack on the onset of the Indian summer monsoon in coupled seasonal forecasts. Clim. Dyn. 47, 2709–2725 (2016).

Halder, S. & Dirmeyer, P. A. Relation of Eurasian snow cover and Indian summer monsoon rainfall: Importance of the delayed hydrological effect. J. Clim. 30, 1273–1289 (2017).

Yasunari, T., Kitoh, A. & Tokioka, T. Local and remote responses to excessive snow mass over Eurasia appearing in the northern spring and summer climate. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 69, 473–487 (1991).

Qian, Y. F., Zheng, Y. Q., Zhang, Y. & Miao, M. Q. Responses of China’s summer monsoon climate to snow anomaly over the Tibetan Plateau. Int. J. Climatol. 23, 593–613 (2003).

Wu, T.-W. & Qian, Z.-A. The relation between the Tibetan winter snow and the Asian summer monsoon and rainfall: An observational investigation. J. Clim. 16, 2038–2051 (2003).

Zhang, Y., Li, T. & Wang, B. Decadal change of the spring snow depth over the Tibetan Plateau: the associated circulation and influence on the East Asian Summer Monsoon. J. Clim. 17, 2780–2793 (2004).

Xu, X. et al. "Downstream effect” of winter snow cover over the eastern Tibetan Plateau on climate anomalies in East Asia. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 90C, 113–130 (2012).

Si, D. & Ding, Y. Decadal change in the correlation pattern between the Tibetan Plateau winter snow and the East Asian Summer Precipitation during 1979–2011. J. Clim. 26, 7622–7634 (2013).

Zhu, Y., Liu, H., Ding, Y., Zhang, F. & Li, W. Interdecadal variation of spring snow depth over the Tibetan Plateau and its influence on summer rainfall over East China in the recent 30 years. Int. J. Climatol. 35, 3654–3660 (2015).

Xiao, Z. & Duan, A. Impacts of Tibetan Plateau snow cover on the interannual variability of the East Asian Summer Monsoon. J. Clim. 29, 8495–8514 (2016).

Wang, C., Yang, K., Li, Y., Wu, D. & Bo, Y. Impacts of spatiotemporal anomalies of Tibetan Plateau snow cover on summer precipitation in Eastern China. J. Clim. 30, 885–903 (2017).

Zhang, R., Zhang, R. & Zuo, Z. Impact of Eurasian spring snow decrement on East Asian summer precipitation. J. Clim. 30, 3421–3437 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Influence of western Tibetan Plateau summer snow cover on East Asian summer rainfall. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 2371–2386 (2018).

Jia, X., Zhang, C., Wu, R. & Qian, Q. Influence of Tibetan Plateau autumn snow cover on interannual variations in spring precipitation over southern China. Clim. Dyn. 56, 767–782 (2021).

Zhang, C., Guo, Y. & Wen, Z. Interdecadal change in the effect of Tibetan Plateau snow cover on spring precipitation over eastern China around the early 1990s. Clim. Dyn. 58, 2807–2824 (2022).

Lin, H. & Wu, Z. Contribution of the autumn Tibetan Plateau snow cover to seasonal prediction of North American winter temperature. J. Clim. 24, 2801–2813 (2011).

Liu, S. et al. Modeled northern hemisphere autumn and winter climate responses to realistic Tibetan Plateau and Mongolia snow anomalies. J. Clim. 30, 9435–9454 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Near-global atmospheric responses to observed springtime Tibetan Plateau snow anomalies. J. Clim. 33, 1691–1706 (2020).

Wang, Z., Wu, R., Duan, A. & Qu, X. Influence of eastern Tibetan Plateau spring snow cover on North American air temperature and its interdecadal change. J. Clim. 33, 5123–5139 (2020).

Zhang, C., Duan, A., Jia, X., Wang, Z. & Pan, Z. A dynamic link between spring Arctic sea ice and the Tibetan Plateau snow increment indicator. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 191 (2023).

You, Q. et al. Review of snow cover variation over the Tibetan Plateau and its influence on the broad climate system. Earth-Sci. Rev. 201, 103043 (2020).

Wang, Z., Wu, R., Zhao, P., Yao, S.-L. & Jia, X. Formation of snow cover anomalies over the Tibetan Plateau in cold seasons. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 4873–4890 (2019).

Cohen, J. & Rind, D. The effect of snow cover on the climate. J. Clim. 4, 689–706 (1991).

Ueda, H., Shinoda, M. & Kamahori, H. Spring northward retreat of Eurasian snow cover relevant to seasonal and interannual variations of atmospheric circulation. Int. J. Climatol. 23, 615–629 (2003).

Wang, Z., Yang, K., Zhang, F., Zhang, J. & Sun, X. Impacts of Tibetan Plateau spring snowmelt on spring and summer precipitation in Northwest China. Atmosphere 14, 466 (2023).

Takahashi, H. G., Sugimoto, S. & Sato, T. Impact of spring land-surface conditions over the Tibetan Plateau on the early summer Asian monsoon using an AGCM large ensemble. Clim. Dyn. 62, 3477–3503 (2024).

Sang, Y., Ren, H. & Li, M. Delayed impacts of spring soil moisture in the Tibetan Plateau on early-summer air temperature in the northern East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2025GL116361 (2025).

Yeh, T.-C., Wetherald, R. T. & Manabe, S. A model study of the short-term climatic and hydrologic effects of sudden snow-cover removal. Monthly Weather Rev. 111, 1013–1024 (1983).

Kain, J. S. et al. Some practical considerations regarding horizontal resolution in the first generation of operational convection-allowing NWP. Weather Forecast. 23, 931–952 (2008).

Yanai, M., Esbensen, S. & Chu, J.-H. Determination of bulk properties of tropical cloud clusters from large-scale heat and moisture budgets. J. Atmos. Sci. 30, 611–627 (1973).

Li, W. et al. Influence of Tibetan Plateau snow cover on East Asian atmospheric circulation at medium-range time scales. Nat. Commun. 9, 4243 (2018).

Kummerow, C. et al. The status of the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) after two years in orbit. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 39, 1965–1982 (2000).

Tao, W.-K. et al. Retrieval of latent heating from TRMM measurements. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 87, 1555–1572 (2006).

Tao, W.-K. & Li, X. The relationship between latent heating, vertical velocity, and precipitation processes: The impact of aerosols on precipitation in organized deep convective systems. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 6299–6320 (2016).

Mathew, S. S. & Kumar, K. K. On the role of precipitation latent heating in modulating the strength and width of the Hadley circulation. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 136, 661–673 (2019).

Wang, Z., Duan, A. & Wu, G. Time-lagged impact of spring sensible heat over the Tibetan Plateau on the summer rainfall anomaly in East China: case studies using the WRF model. Clim. Dyn. 42, 2885–2898 (2013).

Watanabe, M. & Kimoto, M. Atmosphere-ocean thermal coupling in the North Atlantic: a positive feedback. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 126, 3343–3369 (2000).

Liu, G., Wu, R.-G. & Zhang, Y.-Z. Persistence of snow cover anomalies over the Tibetan Plateau and the implications for forecasting summer precipitation over the Meiyu-Baiu region. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 7, 115–119 (2014).

Orsolini, Y. et al. Evaluation of snow depth and snow cover over the Tibetan Plateau in global reanalyses using in situ and satellite remote sensing observations. Cryosphere 13, 2221–2239 (2019).

Lei, Y., Pan, J., Xiong, C., Jiang, L. & Shi, J. Snow depth and snow cover over the Tibetan Plateau observed from space in against ERA5: matters of scale. Clim. Dyn. 60, 1523–1541 (2022).

Shaman, J. & Tziperman, E. The effect of ENSO on Tibetan Plateau snow depth: A stationary wave teleconnection mechanism and implications for the South Asian monsoons. J. Clim. 18, 2067–2079 (2005).

Bothe, O., Fraedrich, K. & Zhu, X. Tibetan Plateau summer precipitation: covariability with circulation indices. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 108, 293–300 (2011).

Cuo, L. et al. Climate change on the northern Tibetan Plateau during 1957–2009: Spatial patterns and possible mechanisms. J. Clim. 26, 85–109 (2013).

Gao, J., He, Y., Masson-Delmotte, V. & Yao, T. ENSO effects on annual variations of summer precipitation stable isotopes in Lhasa, southern Tibetan Plateau. J. Clim. 31, 1173–1182 (2018).

Liu, Y., Chen, H. & Hu, X. The unstable relationship between the precipitation dipole pattern in the Tibetan Plateau and summer NAO. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2025GL116361 (2021).

Yao, T. et al. The imbalance of the Asian water tower. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 618–632 (2022).

Roy, S. & Singh, C. The changing pattern of global teleconnection and the seasonal precipitation in the High Mountain Asia region. Clim. Dyn. 62, 7665–7685 (2024).

Ma, X. et al. Optimization of key land surface albedo parameter reduces wet bias of climate modeling for the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. China Earth Sci. 68, 2653–2662 (2025).

Skamarock, W. C. et al. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF version 4. Technical Report (National Center for Atmospheric Research, 2019).

Lin, C., Chen, D., Yang, K. & Ou, T. Impact of model resolution on simulating the water vapor transport through the central Himalayas: implication for models’ wet bias over the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 51, 3195–3207 (2018).

Lin, C. et al. Summer afternoon precipitation associated with wind convergence near the Himalayan glacier fronts. Atmos. Res. 259, 105658 (2021).

Salerno, F. et al. Local cooling and drying induced by Himalayan glaciers under global warming. Nat. Geosci. 16, 1120–1127 (2023).

Niu, G.-Y. et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 1. Model description and evaluation with local-scale measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D12109 (2011).

Beljaars, A., Brown, A. & Wood, N. A new parametrization of turbulent orographic form drag. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 130, 1327–1347 (2004).

Zhou, X., Yang, K. & Wang, Y. Implementation of a turbulent orographic form drag scheme in WRF and its application to the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 50, 2443–2455 (2018).

Dai, Y. et al. A global high-resolution data set of soil hydraulic and thermal properties for land surface modeling. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 2996–3023 (2019).

Yue, S. et al. Representation of stony surface-atmosphere interactions in WRF reduces cold and wet biases for the southern Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2021JD035291 (2021).

Yang, K. et al. Turbulent flux transfer over bare-soil surfaces: Characteristics and parameterization. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 47, 276–290 (2008).

Zhou, X. et al. The influence of bare ground thermal roughness length parameterization on the simulation of near-surface air and skin temperatures over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2022JD037245 (2022).

Verseghy, D. L. Class–a Canadian land surface scheme for GCMS. I. Soil model. Int. J. Climatol. 11, 111–133 (1991).

Zhou, X. et al. Reducing the cold bias of the WRF model over the Tibetan Plateau by implementing a snow coverage-topography relationship and a fresh snow albedo scheme. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 15, e2023MS003626 (2023).

Miao, X. et al. Accounting for topographic effects on snow cover fraction and surface albedo simulations over the Tibetan Plateau in winter. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 14, e2022MS003035 (2022).

Dudhia, J. Numerical study of convection observed during the winter monsoon experiment using a mesoscale two-dimensional model. J. Atmos. Sci. 46, 3077–3107 (1989).

Mlawer, E. J., Taubman, S. J., Brown, P. D., Iacono, M. J. & Clough, S. A. Radiative transfer for inhomogeneous atmospheres: RRTM, a validated correlated-k model for the longwave. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 102, 16663–16682 (1997).

Thompson, G., Field, P. R., Rasmussen, R. M. & Hall, W. D. Explicit forecasts of winter precipitation using an improved bulk microphysics scheme. Part II: Implementation of a new snow parameterization. Monthly Weather Rev. 136, 5095–5115 (2008).

Bretherton, C. S. & Park, S. A new moist turbulence parameterization in the Community Atmosphere Model. J. Clim. 22, 3422–3448 (2009).

Park, S. & Bretherton, C. S. The University of Washington shallow convection and moist turbulence schemes and their impact on climate simulations with the Community Atmosphere Model. J. Clim. 22, 3449–3469 (2009).

Grell, G. A. & Freitas, S. R. A scale and aerosol aware stochastic convective parameterization for weather and air quality modeling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 5233–5250 (2014).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Pan, J., Xiong, C., Jiang, L., Yang, J. & Shi, J. A physically-based method to estimate high-resolution snow water equivalent by integrating passive microwave and optical remote sensing observations within nested grids. In Proc. IGARSS 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 1665–1670 (IEEE, Athens, Greece, 2024).

Jordan, R. E. A One-dimensional Temperature Model for a Snow Cover: Technical Documentation for SNTHERM.89. Technical Report, Open Polar https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:126628105 (1991).

Wiesmann, A. & Mätzler, C. Microwave emission model of layered snowpacks. Remote Sens. Environ. 70, 307–316 (1999).

Pan, F. et al. MODIS daily cloud-gap-filled fractional snow cover dataset of the Asian Water Tower region (2000–2022). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 2501–2523 (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. TPHiPr: a long-term (1979–2020) high-accuracy precipitation dataset (1/30°, daily) for the Third Pole region based on high-resolution atmospheric modeling and dense observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 621–638 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. A downscaling approach for constructing high-resolution precipitation dataset over the Tibetan Plateau from ERA5 reanalysis. Atmos. Res. 256, 105574 (2021).

Gao, Y., Xu, J. & Chen, D. Evaluation of WRF mesoscale climate simulations over the Tibetan Plateau during 1979–2011. J. Clim. 28, 2823–2841 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work is mainly supported by Chinese Academy of Sciences - Pioneering Initiative Talents Program (Grant Number: E3RC2DQ31S). Contribution from Author X.C. is supported by Key Laboratory of South China Sea Meteorological Disaster Prevention and Mitigation of Hainan Province (Grant Number: SCSF202401) and the Open Grants of the State Key Laboratory of Severe Weather (Grant Number: 2024LASW-B02). The simulation for the numerical experiment was performed on the CASEarth Cloud platform (https://portal.casearth.cn/) of the Computer Network Information Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The work is a contribution to LS4P-II | GEWEX (https://www.gewex.org/ls4p-ii/), and also to CORDEX-FPS-CPTP (http://rcg.gvc.gu.se/cordex_fps_cptp/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L. and K.Y. conceived the idea of the research. J.S. provided the general framework. C.L. conducted the numerical experiments and the analysis, and drafted the article. D.C. and Y.X. provided insightful discussion and suggestions. S.Y. assisted in the LBM simulation. X.Z. provided important updates on the WRF-ARW model. Y.L. discussed the results solidifying the proposed mechanism. J.P. provided snow data and assured their quality. X.C. contributed to improving the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.C. is affiliated with this journal as Editorial Board Member. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, C., Yang, K., Chen, D. et al. Enduring local impact of springtime snow cover over the Third Pole. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 384 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01264-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01264-w