Abstract

Tibetan Plateau (TP) is a sensitive region of climate change, with its precipitation change attracting considerable scientific attention. This study couples dynamical downscaling simulation with the storyline attribution approach to investigate the impact of regional climate change over East Asia (RCC) and TP (PCC) on the sub-daily precipitation over TP. RCC significantly reduces overall precipitation, mainly through decreased morning and stratiform precipitation, but enhances afternoon precipitation by increasing convective precipitation. Furthermore, RCC reduces the precipitation frequency and precipitation intensity, most substantially for morning stratiform precipitation. PCC exerts smaller and less statistically significant impact on precipitation than RCC. The opposing morning–afternoon effects of RCC stem from differing physical mechanisms: RCC stabilizes the atmosphere and reduces moisture in the morning, suppressing convection, while it enhances instability, moisture, and convective energy in the afternoon. Regional differences in RCC-induced precipitation changes are attributed to variations in moisture flux and atmospheric dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Tibetan Plateau (TP), renowned as the “water tower of Asia,” is the world’s highest plateau, with an average elevation exceeding 4000 m and an area of over 2.5 × 106 km2. Located in the center of Asia, its unique geographic location and complex topography exert significant thermal and dynamic effects on regional and global climate1. The TP is one of the most sensitive regions to global climate change. Its annual mean temperature increased by 0.35 °C per decade from 1961 to 2020, a rate more than twice the global warming during the same period2. This significant climate change has changed the spatio-temporal pattern of precipitation amount (PA), precipitation intensity (PI), precipitation frequency (PF), precipitation type, and extreme precipitation over TP3,4,5, which profoundly affects the regional natural disasters and rational utilization of water resources and ecological security. Therefore, understanding the characteristics and mechanisms of precipitation changes over the TP against the backdrop of climate change is of great significance for the rational development of water resources and for disaster prevention and mitigation both on the plateau and in surrounding areas.

The summer climate over TP is mainly controlled by the South Asian monsoon, the East Asian monsoon, and the mid-latitude westerlies, creating a humid climate pattern in the southeastern TP and arid climate pattern in the northwestern TP1. Local factors (e.g., surface heating, complex terrain, and lakes) trigger strong convection during summer, which intensifies local water cycle processes and influences precipitation patterns6,7. Furthermore, climate change induces atmospheric warming, moistening, and circulation changes, which in turn influence long-term variations in summer precipitation over the TP8,9,10. It also increases specific humidity and the water vapor budget, accelerates local evapotranspiration and precipitation recycling, and ultimately affects the spatial distribution of precipitation across the plateau11. Overall, precipitation changes over TP exhibit spatial heterogeneity and temporal variability, with increases in the northern TP and decreases in the southern TP in the context of climate change12. Although climate change is a global phenomenon, its manifestations and consequences are region-specific. East Asia, for instance, experiences significant regional climate change, with warming rates over the Mongolian Plateau and the TP far exceeding the global average13. However, how to separate and what is the effect of regional climate change over East Asia (RCC) and TP (PCC) on precipitation over TP remains unclear and warrant further investigation.

Precipitation in summer contributes 60–70% of the annual total over TP14. Owing to its vast and complex terrain, intense solar radiation, and heterogeneous land surface, the TP fosters mountain-valley breezes and convective activity under favorable thermal and moist conditions. Consequently, summer precipitation exhibits distinct sub-daily characteristics, with diurnal peaks typically occurring in the late afternoon or around midnight15. Moreover, the sub-daily precipitation more accurately reflects the intermittency of the precipitation16 and is more sensitive to climate change than precipitation at daily or longer scale17,18,19. Studies on sub-daily precipitation over TP showed that the amount, frequency, and duration of extreme hourly precipitation in southeastern TP increased during 2005–202020, and shorter duration and more intense precipitation are projected over the southeastern TP21. While changes in sub-daily precipitation characteristics and their relationship with climate change have been extensively studied in North America, Europe, and parts of China22,23,24, how sub-daily precipitation over the TP responds to climate change remains poorly understood. In particular, the large-scale circulation adjustment and thermal forcing of the plateau under regional climate warming may differentially affect various precipitation types at different times of the day. Therefore, how sub-daily precipitation over the TP responds to regional climate change in East Asia and the TP itself, and its associated spatial heterogeneity, remains an open question.

Understanding the trends and interactions between convective and stratiform precipitation—the two dominant precipitation types—is crucial for elucidating the mechanisms through which climate change exerts its impacts. Convective precipitation increasingly dominates extreme precipitation events as it is more sensitive to temperature increases than stratiform precipitation. Previous studies have shown that PI generally increases at a Clausius-Clapeyron (C-C) rate of 6-7% °C-1 in a warming climate, but increased latent heat release from precipitation systems can cause a shift from stratiform to convective precipitation, which may alter this relationship25. The increase in convective precipitation may lead to an increase in PI with increasing temperature that exceeds the C-C rate25,26. Over the northern TP, convective precipitation dominates during the daytime, while stratiform precipitation prevails at night27. However, how sub-daily convective and stratiform precipitation respond to regional climate change over East Asia and the TP remains unknown.

Climate models have been widely used as tools for understanding climate processes and projecting or attributing climate change. To date, the attribution of precipitation over TP has primarily relied on global climate models from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP)10,28,29, however, most CMIP models exhibit substantial wet and cold biases over TP30, resulting in considerable uncertainty into precipitation attribution and projection. Dynamical downscaling simulation with regional climate models at resolutions of 20–50 km could partly alleviate the wet and cold biases2,31. Additionally, the “storyline” approach32,33,34 is an effective approach for attributing precipitation changes to regional climate forcing and for understanding associated local-scale thermodynamic and dynamic processes. In this study, we couple the dynamical downscaling simulation with the storyline attribution approach to separate the effects of regional climate change over East Asia and TP on the sub-daily precipitation over TP and investigate the possible physical mechanisms. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly describes the model configuration, datasets, and methodology. Section 3 presents the results, and Section 4 provides a summary.

Results

Model evaluation

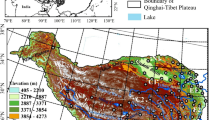

Figure 1 illustrates the spatial distribution of daily accumulated rainfall at the 83 CMA stations and from the two grid datasets (GSMaP_Gauge and CN05.1) and the control (CTL) experiment (“Methods” section). All observation datasets indicate a spatially consistent overall precipitation pattern across the TP. Precipitation gradually decreases from the southeastern TP to the northwestern TP, with heavy rainfall (exceeding 5 mm/day in summer) primarily occurring in the eastern TP and around Namtso Lake. Heavy precipitation causes an obvious positive anomaly over the TP, especially in the eastern TP, where the daily precipitation anomaly even reaches 2 mm/day (figure not shown). However, the datasets present different detailed precipitation characteristics, particularly in terms of PA around the high-precipitation area. The daily mean precipitation over the TP for CMA stations, GSMaP_Gauge, and CN05.1 is 3.53 mm day⁻¹, 2.93 mm day⁻¹, and 2.95 mm day⁻¹, respectively, indicating that different observations exhibit marked differences in PA. The ensemble mean of CTL runs reasonably captures the general daily rainfall characteristics, with spatial correlation coefficients of 0.52, 0.65, and 0.64 compared with CMA stations, GSMaP_Gauge, and CN05.1, but it overestimates precipitation over the TP with a wet bias, especially in the southeastern TP. In addition, CTL effectively captures the spatial distribution of sub-daily rainfall, and the spatial correlation coefficients of precipitation during early morning, morning, afternoon, and evening are 0.71, 0.65, 0.61, and 0.44 compared with GSMaP_Gauge data, although it overestimates the sub-daily precipitation. The precipitation wet bias in the regional simulation over TP is a commonly reported issue in many literatures35,36. This systematic bias is primarily due to incomplete physical processes and underlying surface information (i.e., complex terrain) in regional and climate models, particulary within steep mountain regions of the TP30,37.

Influence of regional climate change on the sub-daily precipitation over TP

Figure 2 shows the simulated summer mean PA for CTL, RCC, and PCC, and Fig. 3 presents the response of daily and sub-daily PA to climate change. To investigate the spatial differences in the response of sub-daily convective and stratiform precipitation to RCC and PCC, we divide the TP into three regions based on the ratio between convective precipitation and stratiform precipitation, as follows (Fig. 2a): western TP (WTP, where the ratio is mostly much greater than 1.0), eastern TP (ETP, where the ratio is generally close to 1.0) and northern TP (NTP, where the ratio is mostly below 1.0). Both daily and sub-daily PA values decrease gradually from the southeastern to the northwestern TP, with the highest amounts occurring in the ETP, followed by the WTP, and the least in the NTP (Fig. 2a–e). Afternoon precipitation contributes over 32% to the daily total precipitation, making it the highest among the four sub-daily intervals (Fig. 3a). However, the contribution from the other three sub-daily periods varies by region. In ETP, the percentage of precipitation in the evening rankes second, and it is lowest in the early morning. In the NTP, precipitation in the morning ranks second and is lowest in the evening, whereas in the WTP, evening precipitation ranks second and is lowest in the morning.

Spatial distribution of (a, f, k) daily precipitation amount (PA, units: mm day−1) and sub-daily PA (units: mm 6 h−1) during (b, g, l) morning, (c, h, m) afternoon, (d, i, n) evening and (e, j, o) early morning for CTL experiment (left), the difference between CTL and NoRCC experiment (RCC, central) and the difference between CTL and NoPCC experiment (PCC, right) in the summer of 2020. The cross-hatching in (a) marks regions where the proportion between convective precipitation and stratiform precipitation less than 1.0, and the area of the black horizontal line indicates that the proportions are between 1.0 and 1.7, as well as the dots indicate the area of proportion exceeding 1.7. The stippling in (f–o) represents the statistical significance of differences at the 90% confidence level.

a The percentage (units: %) of PA during morning (red column), afternoon (orange column), evening (light blue column), and early morning (deep blue column) for CTL, NoRCC, and NoPCC experiment over TP and three sub-regions. b–d The Matrix Heatmap for daily PA (units: mm day−1) and sub-daily PA (units: mm 6 h−1) of RCC and PCC in TP (RCC_TP and PCC_TP), NTP (RCC_NTP and PCC_NTP), ETP (RCC_ETP and PCC_ETP) and WTP (RCC_WTP and PCC_WTP) for b total precipitation, c convective precipitation and d stratiform precipitation. e, f As in c, d, but for the PA proportion (units: %) of convective precipitation (e) and stratiform precipitation (f). The values larger than 50% for CTL are marked.

Spatially, RCC reduces precipitation over the TP on the daily scale and in the morning and evening (Fig. 2f–i). In the afternoon, RCC increases precipitation in the northwestern part of ETP and WTP, but reduces precipitation in NTP (Fig. 2h). In the early morning, RCC reduces precipitation in WTP and the northwestern parts of ETP and NTP (Fig. 2j). Quantitative results from spatial averages show that RCC reduces precipitation over the whole TP on the daily scale and in the morning, evening, and early morning, but increases precipitation in the afternoon over the whole TP, except NTP (Fig. 3b). As a consequence, the proportion of precipitation across the four sub-daily periods also changes under RCC and PCC (Fig. 3a). Over the TP, RCC reduces the precipitation proportion in the morning by 3.57–4.07%, but increases the precipitation proportion in the afternoon by 2.76–3.25%. Changes in the evening and early morning remain minimal, staying below 1%. Similarly, precipitation proportions in NTP, ETP, and WTP decrease by 11.44–14.70%, 1.38–1.71%, and 8.79–10.15% in the morning and increase by 8.60–11.41%, 1.28–1.77%, and 4.34–6.12% in the afternoon, respectively. Changes in proportions during the evening and early morning are significantly smaller than those in the morning and afternoon. In comparison, the impact of PCC on precipitation is noticeably smaller than that of RCC and is statistically insignificant over most of the TP (Fig. 2k–o). The only significant effect is that PCC reduces precipitation over the TP in the morning (Fig. 2l), leading to overall changes in precipitation proportions by 1.15–3.72% in NTP and below 1% in TP, ETP, and WTP (Fig. 3a). The possible reason why the influence of PCC is smaller than that of RCC is RCC mainly affects large-scale circulation and moisture transport patterns from outside the TP, while PCC alters local thermodynamic conditions over the TP itself, such as surface heating.

Further, the contribution of convective precipitation and stratiform precipitation to the total PA is investigated, as shown in Fig. 3e, f. In this study, convective precipitation and stratiform precipitation are derived from the cumulus scheme and microphysics scheme, respectively. On a daily scale, convective precipitation dominates across the TP, accounting for 57.93% of the total precipitation. Quantitatively, RCC increases convective precipitation over the whole TP and NTP in the afternoon, but reduces convective precipitation in the other three sub-daily times (Fig. 3c). In ETP, RCC increases convective precipitation in the morning, afternoon, and evening, but decreases convective precipitation in the early morning. Overall, the daily precipitation convective precipitation increases over TP and ETP, but decreases in NTP and WTP. RCC reduces stratiform precipitation over the entire TP across all time periods (Fig. 4d). Accordingly, RCC generally increases the convective precipitation proportion on the daily scale and in the morning, afternoon, and evening, particularly in the morning over WTP, but reduces the stratiform precipitation proportion. In contrast, PCC has a much smaller impact on the convective and stratiform proportions than RCC. In the morning, PCC increases the convective precipitation proportion over the TP, except in the NTP, and reduces the stratiform precipitation proportion.

Spatial distribution of a, f, k precipitation frequency (PF, units: %) and sub-daily PF (units: %) during b, g, l morning, c, h, m afternoon, d, i, n evening and e, j, o early morning for CTL experiment (left), the difference between CTL and NoRCC experiment (RCC, central) and the difference between CTL and NoPCC experiment (PCC, right) in the summer of 2020. The stippling in f-o represents the statistical significance of differences at the 90% confidence level.

Figure 4 shows the spatial distribution of simulated summer mean PF for CTL, RCC, and PCC. Both the daily and four sub-daily PF values decrease gradually from the southeastern to the northwestern TP, with large PF predominantly occurring in the southeastern TP (Fig. 4a–e). PF is highest in the afternoon and lowest in the early morning over the TP. Spatially, RCC reduces daily PF over the TP, particularly in the WTP and NTP (Fig. 4f). In the morning, RCC reduces PF over the TP, except in the ETP (Fig. 4g). In the afternoon, RCC reduces PF over the TP, except in the northern ETP and central WTP (Fig. 4h). In the evening, RCC reduces PF over the TP (Fig. 4i). In the early morning, RCC reduces PF over the TP, except for a small area in the northwestern WTP (Fig. 4j). Quantitative results from spatial averages show that RCC reduces PF of total precipitation, convective precipitation, and stratiform precipitation over the whole TP, particularly in the morning—except for convective precipitation in the NTP during the afternoon (Fig. 5a–c). In contrast, the decrease in PF of stratiform precipitation is larger than that of convective precipitation. Correspondingly, except in the evening and early morning in the NTP, RCC generally increases the PF proportion of convective precipitation but reduces the PF proportion of stratiform precipitation throughout the day, particularly in the morning (Fig. 5d, e). Comparatively, PCC insignificantly reduces PF over the TP, and the impact of PCC on PF is noticeably smaller than that of RCC (Fig. 4k–o). Overall, PCC also reduces the PF of total and two types of precipitation (Fig. 5a–c) and decreases the PF proportion of stratiform precipitation, except in the afternoon and early morning over the NTP.

As in Fig.3b–f, but for the precipitation frequency (a–e) and precipitation intensity (f–j).

Figure 6 illustrates the spatial distribution of the simulated summer mean PI for CTL, RCC, and PCC. Both daily and sub-daily PI values decrease gradually from the southeastern to the northwestern TP and heavy preciptation is predominantly located in the ETP (Fig. 6a–e). Spatially, RCC reduces PI in the WTP, NTP, and northwestern ETP on the daily scale and in the morning (Fig. 6f, g). In the afternoon, RCC enhances PI in the WTP and ETP (Fig. 6h). In the early morning, RCC enhances PI over the TP, except for a small area in the northern NTP and ETP, and the impact of RCC is more pronounced than in the evening (Fig. 6i, j). Quantitatively, RCC reduces PI over the entire TP on the daily scale (except in the ETP) and in the morning, but enhances PI at other sub-daily scales across the whole TP, except for the NTP in the afternoon and evening (Fig. 5f). Over the entire TP and ETP, RCC increases the PI of convective precipitation throughout the day, except in the early morning. In the NTP, the PI of convective precipitation decreases in the morning and afternoon but increases in the evening and early morning. In the WTP, the PI of convective precipitation increases throughout the day (Fig. 5g). RCC also enhances the PI of stratiform precipitation in the afternoon (except in the WTP), evening, and early morning (except in the NTP), but reduces it in the morning (Fig. 5h). Accordingly, RCC generally increases the proportion of PI from convective precipitation on the daily scale and in the morning and afternoon (except in the NTP), particularly in the morning over the WTP (Fig. 5i). Meanwhile, RCC increases the proportion of PI from stratiform precipitation on the daily scale (Fig. 5j). PCC overall insignificantly increases PI over the TP, and its impact on PI is noticeably smaller than that of RCC (Figs. 6k–o and 5f). PCC enhances the PI of convective precipitation over the entire TP and ETP, except in the early morning. In the NTP, PCC reduces the PI of convective precipitation in the morning and evening but enhances it in the afternoon and early morning (Fig. 5g). PCC enhances the PI of stratiform precipitation, especially in the ETP (Fig. 5h), resulting in an increased proportion of PI from stratiform precipitation over the entire TP (Fig. 5j).

Spatial distribution of a, f, k daily precipitation intensity (PI, units: mm day−1) and sub-daily PI (units: mm 6 h−1) during b, g, l morning, c, h, m afternoon, d, i, n evening and e, j, o early morning for CTL experiment (left), the difference between CTL and NoRCC experiment (RCC, central) and the difference between CTL and NoPCC experiment (PCC, right) in the summer of 2020. The stippling in f-o represents the statistical significance of differences at the 90% confidence level.

Local thermal and dynamic conditions behind the opposite effects of RCC on precipitation in the morning and afternoon

Based on the previous analyses, the RCC exerts a greater influence on precipitation in the morning and afternoon than at night, and its effects during these two periods are opposite. Therefore, we focus on these two time periods to analyze the mechanisms behind the changes in precipitation and their respective spatial differences.

Figure 7 illustrates the influence of RCC on the vertical profiles of temperature, wind, water vapor, and static energy. In the morning, lower-layer temperatures decrease while upper-layer temperatures increase, resulting in a more stable atmospheric stratification (Fig. 7a). The lower-layer atmospheric moisture content reduces and westerly winds weaken, whereas upper-layer atmospheric moisture increases and westerly winds strengthen (Fig. 7b, c). Additionally, RCC leads to a decrease in moisture static energy (MSE) in the middle and lower layers (Fig. 7d) and in the outgoing longwave radiation (OLR, figure not shown), indicating a slight weakening of convective motion. All of these conditions are unfavorable for precipitation. In the afternoon, however, lower-layer temperatures increase and higher-layer temperatures decrease, leading to greater atmospheric instability (Fig. 7a). The atmospheric moisture content increases significantly (Fig. 7b), and the lower-level westerly winds strengthen (Fig. 7c). RCC also causes an increase in MSE in the middle and lower layers (Fig. 7d) and in the OLR, suggesting intensified convection. The rise in MSE is mainly due to the increase in latent heat energy (Fig. 7d), indicating substantial convective latent heat release associated with moist lifting and atmospheric instability, which can further intensify ascending motions and thus become conducive to precipitation. All of the above conditions are favorable for precipitation.

Vertical profiles of the difference in a temperature (units: K), b water vapor mixing ratio (units: g kg−1), and c zonal wind (units: m s−1) between CTL and NoRCC experiment during 0800–1400 BST (solid lines) and 1400–2000 BST (dotted lines) averaged over TP in summer 2020. d As in (a–c), but for the moisture static energy (MSE, red, units: J kg−1), dry static energy (DSE, green, units: J kg−1), and latent static energy (LSE, blue, units: J kg−1).

The mechanisms underlying regional differences in RCC-induced precipitation changes are also discussed. Figure 8 presents the moisture flux and its divergence during the morning and afternoon for the CTL experiments and RCC. In both the morning and afternoon, the moisture flux carries by westerly wind dominates in both WTP and NTP, while the moisture flux in ETP mainly comes from both westerly wind and southerly wind (Fig. 8a, b). In terms of water vapor convergence, ETP shows the strongest convergence, particularly in the southern ETP, followed by WTP and the southern areas of NTP, which is consistent with the distribution of precipitation. In the afternoon, both the overall moisture flux and its convergence are stronger than in the morning, resulting in stronger precipitation in the afternoon. Figure 8c shows that in the morning, RCC weakens the westerly moisture flux and overall causes moisture flux divergence in WTP and NTP, but enhances the southerly and easterly moisture flux in ETP, resulting in moisture flux convergence in southeastern ETP, where RCC increases the precipitation. This leads to a smaller decrease in precipitation in ETP compared to NTP and WTP (Fig. 8c). In the afternoon, RCC causes an overall enhancement of the southerly and easterly moisture flux and its convergence, particularly in ETP. However, in NTP, RCC predominantly leads to a weakening of moisture flux convergence, resulting in reduced precipitation (Fig. 8d).

Spatial distribution of vertical integral moisture flux divergence (shading, units: 10−5 kg m2 s−1) and moisture flux (vector, units: 10-2 kg m−1 s−1) from surface to 400 hPa during 0800–1400 BST (a, c) and 1400–2000 BST (b, d) for CTL experiment (a, b) and difference between CTL and NoRCC experiment (c, d).

Figure 9 illustrates the vertical cross section of water vapor mixing ratio and vertical velocity. In the morning, the column atmospheric moisture and vertical upward wind over the western TP are weaker than those over the eastern TP (Fig. 9a). In the afternoon, the column atmospheric moisture and vertical upward wind remain stronger in the eastern TP than in the western TP and are stronger than in the morning (Fig. 9b). In the morning, RCC reduces the atmospheric moisture in the western TP but increases it in the eastern TP (Fig. 9c). Additionally, RCC enhances the vertical upward wind in the eastern TP but slightly enhances the vertical downward wind in the western TP, thereby reducing precipitation in the western TP and increasing precipitation in the eastern TP. In the afternoon, RCC increases atmospheric moisture over both the eastern and western TP and enhances the vertical upward wind over the TP except in the central TP around 90°E, thereby increasing precipitation in both the western and eastern TP (Fig. 9d).

Vertical cross section of the water vapour mixing ratio (shading, units: g kg−1) and the vertical circulation vectors (zonal winds and 1000 times of vertical velocity, units: 10−3 m/s), which are latitudinal averaged over TP during 0800–1400 BST (a, c) and 1400–2000 BST (b, d) for CTL experiment (a, b) and the difference between CTL and NoRCC experiment (c, d).

Discussion

Understanding the sub-daily precipitation response to regional climate change is crucial for comprehending the mechanisms driving climate change impacts and improving water resource management and disaster prevention. The study investigates the impact of RCC and PCC on sub-daily precipitation over the TP. The key findings are summarized as follows:

(1) Various observational precipitation datasets consistently show a southeast-to-northwest precipitation gradient over the TP during summer 2020, though notable discrepancies exist in high-precipitation regions. The CTL experiment captures the general rainfall patterns but systematically overestimates precipitation, especially in the southeastern TP, likely due to model limitations in representing complex terrain and physical processes.

(2) RCC leads to an overall reduction in precipitation over the TP, mainly due to decreased precipitation in the morning and a decline in stratiform precipitation. However, RCC increases afternoon precipitation over the TP, primarily resulting from enhanced convective precipitation. Furthermore, RCC increases the proportion of convective precipitation, while reduces the proportion of stratiform precipitation, particularly in the morning. It also significantly alters the proportion of sub-daily precipitation, reducing morning precipitation by 3.57–4.07% and increasing afternoon precipitation by 2.76–3.25%.

(3) RCC reduces PF of total, convective, and stratiform precipitation over the TP across all daily and sub-daily periods, with the most substantial decreases occurring in the morning, and the reduction in PF is more pronounced for stratiform precipitation than for convective precipitation. Consequently, RCC increases the proportion of PF from convective precipitation while reduces that from stratiform precipitation. RCC also reduces daily PI (except in the ETP) and morning PI over the entire TP, attributing to the reduction in stratiform PI, but enhances PI during the afternoon, evening, and early morning across most of the TP, primarily driven by an increase in convective and stratiform PI. In comparison, PCC has a noticeably smaller and generally less statistically significant impact on precipitation over the TP relative to RCC. PCC primary reduces precipitation during the morning, attributing to the reduction in stratiform precipitation. Over the TP, PCC reduces PF but increases PI, resulting from respective reductions and enhancements in both convective and stratiform precipitation.

(4) RCC exerts opposing effects on precipitation between morning and afternoon over the TP because it suppresses convection through atmospheric stabilization and moisture reduction in the morning, while enhances atmospheric instability, moisture content, and convective energy in the afternoon. The regional differences in RCC-induced precipitation changes primarily stem from the fact that RCC weakens the westerly moisture flux over WTP and NTP in the morning, but enhances the southerly and easterly moisture fluxes and their convergence in southeastern ETP. Additionally, RCC reduces atmospheric moisture and slightly enhances downward vertical motion over the western TP, but increases atmospheric moisture and enhances upward vertical motion in the eastern TP. These processes lead to a smaller decrease in precipitation in the ETP compared to the NTP and WTP. In the afternoon, RCC strengthens the southerly and easterly moisture fluxes and their convergence, particularly in the ETP. It also increases atmospheric moisture and enhances upward vertical motion across both the eastern and western TP, thereby increasing precipitation in both regions.

Taking the 2020 summer precipitation as a recent case study, we demonstrate the complex effects of RCC and PCC on the sub-daily precipitation over TP. However, the systematic overestimation of precipitation in models, along with potential inaccuracies in the partitioning between convective and stratiform precipitation caused by cumulus parameterization schemes, may affect the representativeness of our findings. In addition, given the potential impact of internal climate variability, the use of a single season’s simulation limits the generalizability of the results. Although the specific magnitude of sub-daily precipitation changes attributable to climate change may vary across different years, the relative qualitative responses of sub-daily precipitation over TP to RCC/PCC and the underlying mechanisms, such as atmospheric stabilization and enhanced convection driven by warming, are expected to remain generally valid. Besides, we also noted that removing the post-1980 linear trend of climate change may overlook the effects of natural climate variability, such as El Niño or large-scale circulation shifts. Future work should involve coordinated, large attribution efforts with decadal-long simulations and combine higher-resolution models, particularly the convection-permitting models at kilometer scales38,39 and more comprehensive observational data to better understand the evolving characteristics of sub-daily precipitation under long-term climate change, which will provide scientific support for water resource management, disaster risk reduction, and sustainable development across the TP and surrounding regions.

Methods

Data

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the simulated summer precipitation over the TP in 2020, we employ three distinct types of precipitation observations, addressing the scarcity of station-based data and their concentration in the central and eastern regions. These datasets are:

-

1.

Daily surface rain gauge data provided by the National Meteorological Information Center (NMIC) of the China Meteorological Administration (CMA). This dataset comprises 83 stations across the TP, most of which are situated in the semi-humid and semi-arid regions of the plateau.

-

2.

CN05.1 observational data developed by the National Climate Centre of the China Meteorological Administration, with a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°. This dataset integrates a large number of observational stations to ensure reliability and employs advanced interpolation techniques to improve coverage in regions with sparse station data.

-

3.

The GSMaP_Gauge product, archived by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission, with spatial and temporal resolutions of 0.1° × 0.1° and 1 h, respectively. In the GPM era, Global Satellite Mapping of Precipitation (GSMaP) and Integrated Multi-satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) are two widely used satellite precipitation products. The GSMaP_Gauge product used in this study is a gauge-calibrated product that adjusts the GSMaP_MVK estimates using the Climate Prediction Center’s gauge-based global daily precipitation analysis. Compare to IMERG, it demonstrates higher accuracy40.

The study also utilizes the fifth generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) atmospheric reanalysis (ERA5) with spatial resolution of approximately 30 km to calculate the trend of the post-1980 regional climate change. No interpolation is performed on the data when evaluating the spatial distribution of precipitation in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the differences in precipitation distribution in various observations. For quantitative comparison, all simulated variables are bilinearly interpolated to the resolution of the target observational dataset when calculating the spatial correlation between observed and simulated precipitation.

To investigate the response of sub-daily precipitation over the TP to regional climate change across East Asia and the TP, we divide the day into four distinct diurnal phases: morning (0800–1400 BST), afternoon (1400–2000 BST), evening (2000–0200 BST), and early morning (0200–0800 BST).

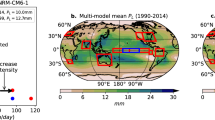

Model configuration and experimental design

This study employs a storyline framework32 and dynamical downscaling simulations with and without regional climate change using the Weather Research and Forecasting Model (WRF) to investigate the impacts of regional climate change over East Asia and TP on the sub-daily precipitation over TP. We focus on the summer precipitation in a climatologically normal year of 2020. The regional averaged summer precipitation in 2020 was 281.07 mm, exceeding the 1980–2010 climatology by only 2.96 mm, corresponding to a precipitation anomaly percentage of 1.06%. Three sets of ensemble experiments are conducted (Table 1). The control (CTL) experiments are driven by realistic initial and boundary conditions (IBCs) based on the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP/FNL) final analysis data, using a piecewise integration method that has been shown to improve the credibility of modeled climate sensitivity41,42. To evaluate the response of sub-daily precipitation over TP to regional climate change over East Asia and TP, two additional sets of ensemble simulations are performed. The first (NoRCC experiment) uses the same configuration as the CTL experiment but removes the post-1980 regional climate change trend estimated by the ERA5 reanalysis data from the IBCs across the entire simulation domain. The second (NoPCC experiment) is identical to the NoRCC experiment, except that the post-1980 climate change trend is removed only from the IBCs over the TP. The differences between the CTL and NoRCC simulations and between the CTL and NoPCC simulations are defined as the precipitation response to regional climate change over East Asia and the TP, abbreviated as RCC and PCC, respectively.

Removing the climate change trend is a commonly method for assessing climate change impacts27,28,29 within the “storyline” approach, which is common and increasingly attractive approaches when attributing the effect of climate change43. Moreover, conducting single-season or short-term simulations is an accepted practice. By removing the climate change trend, numerous studies have quantitatively attributed the influence of climate change on precipitation events in United States44, Japan45, Indian46, China34, and Mediterranean region47. We first compute the climate change trend for all variables used in IBCs of WRF model (including geopotential height, horizontal winds, air temperature, relative humidity, etc.) from the ERA5 monthly reanalysis data. The calculated trends are then interpolated onto the WRF model’s horizontal and vertical grids and removed from the IBCs prior to model integration. Figure 10 illustrates the spatial distributions of the removed linear trends in 2-m temperature and 500-hPa air temperature for the NoRCC and NoPCC experiments.

The model is configured with a horizontal grid spacing of 27 km (Fig. 1a, b) and grid cells of 280 × 220, centered at (30°N, 105°E). The unevenly spaced terrain-following vertical coordinate levels are used with 38 vertical layers up to 50 hPa. The IBCs are derived from the NCEP/FNL final analysis data with a horizontal resolution of 1° and 6-h temporal intervals. All simulations are initialized from 00 UTC 25 May and integrate continuously to 00 UTC September 1, 2020, without any form of spectral nudging. The first 7 days before June 1st are considered the spin-up period, and the period from 1 June to August 31 of 2020, is used for analysis.

To assess the uncertainties, all experiments include six ensemble members that differ in their microphysical parameterization schemes: the Thompson aerosol-aware scheme48, Purdue-Lin microphysics scheme49, WRF Single Moment 6-class (WSM6) scheme, Goddard microphysics scheme, Morrison double-moment microphysics scheme, WRF Double-Moment 6-class microphysics scheme. The other main physical parameterization schemes include the Betts-Miller-Janjic cumulus convection scheme50,51, the Community Atmosphere Model longwave radiation and shortwave radiation scheme52, the Yonsei University planetary boundary layer scheme53 and the Noah land surface model54.

Data availability

The data used in the manuscript are publicly available for GSMaP_Gauge (ftp://hokusai.eorc.jaxa.jp), CN05.1 (https://ccrc.iap.ac.cn/resource/detail?id=228) and ERA5 (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6). In compliance with data policies in China, the precipitation datasets for CMA_station employed in this study are not publicly available online. For detailed information regarding data access, researchers and interested parties are encouraged to contact either the China Meteorological Data Service Center (http://data.cma.cn/en) or the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) (http://www.cma.gov.cn/en2014/aboutcma/contactus/). The WRF simulation datasets generated during this study are too large to be conveniently hosted in a public repository but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

All figures are produced using Python v3.12 and NCAR Command Language. All codes are also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kuang, X. & Jiao, J. J. Review on climate change on the Tibetan Plateau during the last half century. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 3979–4007 (2016).

Gao, Y., Xu, J. & Chen, D. Evaluation of WRF mesoscale climate simulations over the Tibetan plateau during 1979–2011. J. Clim. 28, 2823–2841 (2015).

Cao, L. & Pan, S. Changes in precipitation extremes over the “Three-River Headwaters” region, hinterland of the Tibetan Plateau, during 1960–2012. Quat. Int. 321, 105–115 (2014).

You, Q., Fraedrich, K., Ren, G., Ye, B., Meng, X. & Kang, S. Inconsistencies of precipitation in the eastern and central Tibetan Plateau between surface adjusted data and reanalysis. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 109, 485–496 (2012).

You, Q., Kang, S., Aguilar, E. & Yan, Y. Changes in daily climate extremes in the eastern and central Tibetan Plateau during 1961–2005.J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D07101 (2008).

Wang, Y., Yang, K., Huang, W., Qiu, T. & Wang, B. Dominant contribution of South Asia monsoon to external moisture for extreme precipitation events in northern Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 15, 735 (2023).

Yang, K. et al. Recent climate changes over the Tibetan Plateau and their impacts on energy and water cycle: a review. Glob. Planet. Change 112, 79–91 (2014).

Ding, Z., Zhai, P. & Wu, R. Recent change in summer rainfall over the Tibetan Plateau: Roles of anthropogenic forcing and internal variability. Clim. Dyn. 61, 1887–1902 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Anthropogenic forcing and Pacific internal variability-determined decadal increase in summer precipitation over the Asian water tower. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 38 (2023).

Zhao, D., Zhang, L. & Zhou, T. Detectable anthropogenic forcing on the long-term changes of summer precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 59, 1939–1952 (2022).

Cheng, T., Chen, D., Wang, B., Qiu, T. & Lu, M. Human-induced warming accelerates local evapotranspiration and precipitation recycling over the Tibetan Plateau. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 388 (2024).

Kukulies, J., Chen, D. & Wang, M. Temporal and spatial variations of convection and precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau based on recent satellite observations. Part I: Cloud climatology derived from CloudSat and CALIPSO. Int. J. Climatol. 39, 5396–5412 (2019).

Zuo, Z. & Xiao, D. Linking global to regional climate change. J. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 17, 705–712 (2021).

Wang, X., Pang, G. & Yang, M. Precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau during recent decades: a review based on observations and simulations. Int. J. Climatol. 38, 1116–1131 (2018).

Yu, R. & Li, J. Regional characteristics of diurnal peak phases of precipitation over contiguous China. J. Meteorol. Res. 74, 18–30 (2016).

Trenberth, K. E., Zhang, Y. & Gehne, M. Intermittency in precipitation: Duration, frequency, intensity, and amounts using hourly data. J. Hydrometeor. 18, 1393–1412 (2017).

Ali, H. & Mishra, V. Increase in subdaily precipitation extremes in India under 1.5 and 2.0 °C warming worlds. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 6972–6982 (2018).

Barbero, R., Westra, S., Lenderink, G. & Fowler, H. Temperature-extreme precipitation scaling: a two-way causality?. Int. J. Climatol. 38, e1274–e1279 (2018).

Chinita, M. J., Richardson, M., Teixeira, J. & Miranda, P. M. A. Global mean frequency increases of daily and sub-daily heavy precipitation in ERA5. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 074035 (2021).

Li, R. & Yao, X. Characteristics of summer hourly extreme rainfall events in the region of southeastern Xizang plateau-western Sichuan basin. Plateau Meteorol. 43, 1113–1124 (2024).

Ma, M., Tang, J., Ou, T. & Chen, D. Subdaily extreme precipitation and its linkage to global warming over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2023JD039062 (2023).

Prein, A. F., Rasmussen, R. M., Ikeda, K., Liu, C., Clark, M. P. & Holland, G. J. The future intensification of hourly precipitation extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 48–52 (2017).

Chan, S. C., Kendon, E. J., Fowler, H. J., Blenkinsop, S. & Roberts, N. M. Projected increases in summer and winter UK sub-daily precipitation extremes from high-resolution regional climate models. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 084019 (2014).

Tang, J. et al. Projection of hourly extreme precipitation using the WRF model over eastern China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 128, e2022JD036448 (2023).

Berg, P., Moseley, C. & Haerter, J. O. Strong increase in convective precipitation in response to higher temperatures. Nat. Geosci. 6, 181–185 (2013).

Park, I.-H. & Min, S.-K. Role of convective precipitation in the relationship between subdaily extreme precipitation and temperature. J. Clim. 30, 9527–9537 (2017).

Guo, J. et al. Diurnal variation and the influential factors of precipitation from surface and satellite measurements in Tibet. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 2940–2956 (2014).

Jiang, J. et al. Precipitation regime changes in High Mountain Asia driven by cleaner air. Nature 623, 544–549 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Zhou, T., Zhang, W. & Li, J. Change in precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau projected by weighted CMIP6 models. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 39, 1133–1150 (2022).

Zhu, Y. & Yang, S. Evaluation of CMIP6 for historical temperature and precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau and its comparison with CMIP5. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 11, 239–251 (2020).

Niu, X. R. et al. The performance of CORDEX-EA-II simulations in simulating seasonal temperature and elevation-dependent warming over the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Dyn. 57, 1135–1153 (2021).

Shepherd, T. G. et al. Storylines: an alternative approach to representing uncertainty in physical aspects of climate change. Clim. Change 151, 555–571 (2018).

Meredith, E. P., Semenov, V. A., Maraun, D., Park, W. & Chernokulsky, A. V. Crucial role of Black Sea warming in amplifying the 2012 Krymsk precipitation extreme. Nat. Geosci. 8, 615–619 (2015).

Ma, Y., Hu, Z., Meng, X., Liu, F. & Dong, W. 2022: Was the record-breaking meiyu of 2020 enhanced by regional climate change?. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 103, S76–S82 (2022).

He, M., Zhang, S., Yang, X. & Yin, S. Numerical simulation of a typical convective precipitation and its cloud microphysical process in the Yushu area, based on the WRF model. Atmosphere 13, 1311 (2022).

Prein, A. F. et al. Towards ensemble-based kilometer-scale climate simulations over the Third Pole region. Clim. Dyn. 60, 4055–4081 (2023).

Zhang, Y. & Li, J. Impact of moisture divergence on systematic errors in precipitation around the Tibetan Plateau in a general circulation model. Clim. Dyn. 47, 2923–2934 (2016).

Li, P., Furtado, K., Zhou, T., Chen, H. & Li, J. Convection-permitting modelling improves simulated precipitation over the central and eastern Tibetan Plateau. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 147, 341–362 (2021).

Zou, L. & Zhou, T. Convection-permitting simulations of current and future climates over the Tibetan plateau. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 1901–1916 (2024).

Ning, S. W. et al. Error analysis and evaluation of the latest GSMap and IMERG precipitation products over Eastern China. Adv. Meteorol. 2017, 1803492 (2017).

Gan, R., Yang, Y. & Ma, Y. Modelling the impacts of the Pacific Ocean sea surface temperature anomalies on a drought event in southwestern China with a piecewise-integration method. Int. J. Climatol. 39, 799–813 (2019).

Li, Y., Liu, F., Wang, X., Dong, W. & Dai, T. A piecewise integration approach for model error-induced biases of greenhouse gas contribution to global warming. Clim. Dyn. 58, 3175–3186 (2022).

Swain, D. L., Singh, D., Touma, D. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Attributing extreme events to climate change: a new frontier in a warming world. One Earth 2, 522–527 (2020).

Wang, Simon, S.-Y., Zhao, L., Yoon, J. H., Klotzbach, P. & Gillies, R. R. 2018. Quantitative attribution of climate effects on Hurricane Harvey’s extreme rainfall in Texas. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 054014 (2018).

Kawase, H. et al. The heavy rain event of July 2018 in Japan enhanced by historical warming. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, S109–S114 (2020).

Cho, C. et al. Anthropogenic footprint of climate change in the June 2013 northern India flood. Clim. Dyn. 46, 797–805 (2016).

Meredith, E. P., Maraun, D., Semenov, V. A. & Park, W. Evidence for added value of convection-permitting models for studying changes in extreme precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 12500–12513 (2015).

Thompson, G. & Eidhammer, T. A study of aerosol impacts on clouds and precipitation development in a large winter cyclone. J. Atmos. Sci. 71, 3636–3658 (2014).

Lin, Y.-L., Farley, R. D. & Orville, H. D. Bulk parameterization of the snow field in a cloud model. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 22, 1065–1092 (1983).

Betts, A. K. A new convective adjustment scheme. Part I: observational and theoretical basis. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 112, 667–691 (1986).

Janjic, Z. I. The step-mountain Eta coordinate model: further developments of the convection, viscous sublayer, and turbulence closure schemes. Mon. Wea. Rev. 122, 927–945 (1994).

Collins, W. D. et al. Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM 3.0). NCAR Technical Note NCAR/TN-464+STR (National Center for Atmospheric Research, 2004).

Hong, S. Y., Noh, Y. & Dudhia, J. A new vertical diffusion package with an explicit treatment of entrainment processes. Mon. Wea. Rev. 134, 2318–2341 (2006).

Schaake, J. C., Koren, V. I., Duan, Q.-Y., Mitchell, K. & Chen, F. Simple water balance model for estimating runoff at different spatial and temporal scales. J. Geophys. Res. 101, 7461–7475 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42325502, 42130610 and 42275097), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFF1306204), the CAS “Light of West China” Program, the program of the Key Laboratory of Cryospheric Science and Frozen Soil Engineering, CAS (No. CSFSE-ZQ-2405) and Nature Science Foundation of Gansu province (24JRRA080). The authors would like to acknowledge the public data websites for providing the datasets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M. contributed to the conceptualization and methodology. Y.M. and X.H. performed the statistical analysis, visualization, and writing the original draft. X.H., Y.M., X.M., and D.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. X.M., Y.M., and D.M. performed the funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Y., Hu, X., Meng, X. et al. Response and mechanisms of sub-daily precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau to regional climate change. npj Clim Atmos Sci 9, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01275-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01275-7