Abstract

An accurate assessment of black carbon (BC) climate and health impacts requires knowledge of its mass absorption cross-section (MACBC) – a parameter linking optical and mass measurements. The mean MACBC for freshly emitted soot typically spans a narrow range of 8 ± 1 m2 g⁻1 at 550 nm1,2 but is modified by subsequent atmospheric aging. Determination of MACBC requires simultaneous measurements of aerosol light-absorption coefficient (βabs) and BC mass. Here, we compile 230 measured MACBC values from 80 atmospheric studies and explore the effects of sampling location, study duration, instrumentation, and measurement wavelength. The compiled data set shows a broad variability in MACBC values (a factor of about 200%). We conclude that this variability is attributable to a combination of the above-mentioned effects with additional instrumental uncertainties (e.g., cross-sensitivities and/or inadequate instrument calibration). The current state of knowledge does not support the use of simplistic generalizations or assumptions about MACBC in the atmosphere, motivating a recommendation to further improve and standardize measurement practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Black carbon (BC) aerosol particles are produced by incomplete combustion of carbonaceous fuels, mainly solid or liquid fossil fuels and biomass1,2. The term BC generally refers to a material produced by combustion, referred to as mature soot in combustion science3. BC has a well-defined set of physical and optical properties; such particles are: (i) strong broadband-light absorbers (thus black), (ii) refractory, (iii) insoluble, (iv) consist of aggregated spherules, and (v) consist of graphitized carbon with a high sp2/sp3 ratio4. The precise properties of the broader category of BC-containing aerosols depend greatly on the combustion conditions, where BC is often co-emitted with organic aerosol particles, and ageing in the atmosphere1. Beyond their negative impacts on human health5,6, combustion-generated aerosol particles have strong climate impacts by directly absorbing incoming solar radiation from the ultraviolet (UV) through to the infrared (IR) region. By absorbing solar radiation, BC can modify atmospheric stability and boundary-layer dynamics, influence cloud formation and lifetime, and alter regional precipitation patterns7. The particles also have indirect and semi-direct effects related to cloud radiative effects and deposition of particles on highly reflective surfaces such as snow and ice8. Accurate prediction of this radiative forcing in atmospheric models relies on knowledge of the BC mass absorption cross-section (MACBC), which quantifies the amount of light absorption per unit mass of black carbon. Conversely, MACBC is a key property for characterizing BC’s health effects, where it can be used to link optical measurements to mass concentration. Both mass and optical measurements are common, and therefore, the MACBC is a key parameter for harmonizing air-quality measurements across the globe.

Studies of health effects5,6 suggest that the metric “BC mass concentration” in ambient air is a better indicator of harmful particulate substances from combustion sources than the total undifferentiated particulate matter (PM) mass concentration. Multiple techniques have been developed to measure BC mass concentration, including “elemental carbon” based on thermo-optical analysis (EC); equivalent black carbon based on optical measurements and an assumed MAC (eBC); and refractory black carbon based on laser-induced incandescence (rBC)4. As a result, these metrics can yield BC mass concentration estimates that are not directly comparable, due to differences in measurement principles and underlying different assumptions9,10,11,12,13. However, the variability obtained when using each of these methods in ambient monitoring to obtain MACBC is poorly understood. This variability is influenced by the wide range of physico-chemical properties found in BC-containing PM in the atmosphere, and it is expected to differ across both measurement techniques and specific instrument implementations.

In this review, we will demonstrate the observed variability of atmospheric MACBC at various ambient monitoring stations, as determined through various methodologies, aiming at identifying the primary contributing factors. Owing to the well-documented artifacts associated with filter-based optical methods (elaborated in the “Methods” section), emphasis is placed on studies employing direct absorption measurement techniques, such as photo-acoustic spectroscopy, or studies that apply comprehensive corrections to the data obtained from filter-based optical methods. Additionally, we consider studies that implement volatilization of the non-absorbing coating to reduce scattering-related artifacts, albeit at the expense of losing critical information on the radiative impact of BC particles. These studies are presented as a distinct case study for thorough examination.

Results

Ambient MACBC was extracted from a total of 80 studies, representing a range of environments, spanning urban, remote (e.g., rural, arctic, high altitude), and mixed sites (e.g., suburban, urban outflow). The majority of studies (66) reported aerosol absorption coefficients from filter-based methods, while only 14 studies used a photo-acoustic instrument, and none used photothermal interferometry or an indirect technique. A typical method to define the BC mass concentration was based on standard thermal-optical analysis (TOA) or similar; however, 18 studies applied incandescence using a Single Particle Soot Photometer (SP2), and one study applied Raman spectroscopy, which was successfully compared with thermo-optical EC14. Some studies applied solvent or thermal methods to remove the black carbon coating, whereas most of the studies measured directly aged, coated, atmospheric BC. This yielded a total of 230 MACBC values. The geographic distribution of the measurements is concentrated in the northern hemisphere, with a particularly high density of sites in Europe (Fig. 1). Lack of data, especially from the BC-hotspot areas in Africa and South America, is immediately noticeable. There are also geographic discrepancies in device use, with Europe predominantly using the multi-angle absorption photometer (MAAP), North America primarily deploying photoacoustic, and Asia deploying a mix of instrumentation.

MAAP photometers were distinguished from other filter-based absorption photometers due to their difference in working principle. Highlighted countries correspond to studies wherein data were compiled from multiple locations into a single value for the MAC or aircraft-based campaigns covering a broader region. Background color scale shows the BC column mass concentration between 2022 and 2024 from a data assimilation model194.

Aerosol absorption measurements in the selected reference studies covered a broad wavelength range extending from 355 to 1047 nm, following the specifics of the applied techniques. Harmonization of these measurements to a single wavelength requires the assumption of an absorption Ångström exponent (AAE), which introduces particularly high uncertainty when other absorbing species, such as brown carbon, are present. MACBC is presented as a function of wavelength, without any AAE assumptions, in Figure 2a. MACBC and λ do not show a statistically significant linear correlation (p > 0.05), although a weak negative trend (MACBC = –0.009λ) is indicated, with R² = 0.15. Applying the AAE = 1 assumption (Fig. 2b), this negative trend diminishes (MACBC,550 = –0.004λ), where the remaining part could be indicative of the presence of other absorbing species at lower wavelengths. The observed very weak trend, however, indicates that the brown carbon impact in the overall dataset is minor (i.e., the reported MACBC at shorter wavelengths does not appear to be systematically higher). This does not imply that brown carbon or other absorbing species would not impact individual values, when in fact, some studies have reported AAE > 115,16,17,18,19. Therefore, we do not conclude that brown carbon is generally insignificant relative to BC, but rather that its relative importance must be investigated with directly comparable measurements. Of the total of 230 MAC values, 84% were reported at λ ≥ 550 nm, which are known to be less susceptible to impacts from other absorbing material.

In a, dashed lines are isolines of constant MAC for an AAE of 1. In b, MAC data are interpolated to 550 nm using AAE = 1, where isolines correspond to MAC increments of 4 m2 g−1 at 550 nm, matching (a). Such lines can also be interpreted as absorption enhancements from 0.5 to 3.0 when assuming the MAC of the core particle is 8 m2 g−1. In b, studies that reported biomass-burning dominated samples are highlighted using points with thicker borders.

Our focus here is BC, for which an AAE = 1 is generally a good approximation assuming bare soot at the Rayleigh limit with a wavelength-independent refractive index20. However, there is both experimental and theoretical evidence that the AAE of BC can vary depending on particle morphology and size21,22,23,24. For this reason, we have tested the sensitivity of MAC to AAE in the range 0.8–1.3.

Harmonization of data to a single wavelength decreases the MAC values at lower wavelengths and increases them at higher wavelengths (Fig. 3b), but the variability in measurements overwhelms any other statistically significant trends. For consistency, the MACBC values throughout the remainder of this work are corrected to a wavelength of 550 nm for an easier comparison of the various factors impacting the measurement results.

Note that panel a does not account for the differences in, e.g., urban/remote, fresh/aged, or mass reference and is therefore not a direct comparison of the techniques. The isolines correspond to MAC increments of 4 m2 g−1. The dashed lines show the reference MAC expected for pure BC, which is 8 ± 1 m² g−1 at 550 nm.

The average (seasonal, annual, or campaign) MACBC value when converted to a wavelength of 550 nm by assuming AAE = 1, extends from 2.6 to 26.6 m2 g−1, with an average of 10.8 ± 1.8 m2 g−1. The reported MAC values include mostly untreated samples, so that the average increases only slightly to 11.1 ± 1.9 m2 g−1 when the thermodenuded (18 in total) and solvent-treated aerosol values (5 in total) are excluded. When varying the AAE linearly between 0.8 and 1.3, the mean MAC₅₅₀ from all studies changed by +11% across the range (from −4.1% at AAE = 0.8 to +6.9% at AAE = 1.3, relative to AAE = 1.0). However, the MAC values at shorter wavelengths are likely to be more affected by contributions from other absorbing species in this spectral range. The observed high variability can be attributed to differences in measurement methods and aerosol composition, which is reflected in the variability of Eabs. The absorption enhancement factor depends on a number of aerosol properties, such as coating and core size and composition, and particle morphology (e.g., refs. 25,26,27), and therefore, the atmospheric range of Eabs is expected to be large. Furthermore, measurement uncertainties associated with the different techniques and cross-sensitivities to other light-absorbing aerosol materials, such as brown carbon, and to purely scattering aerosol, contribute to the large variability in the MACBC values surveyed here.

Explaining the high variability in atmospheric MACBC

The contributions to the spread in the results are separated into various factors that could impact the measurements and thus the MACBC values. To start, Fig. 3a considers the impact of the optical measurement approach, broadly categorized as either filter-based or photoacoustic (the only in-situ technique that has been widely deployed). Filter-based techniques yielded higher MACs, with an average of 11.6 m2 g−1 at 550 nm for the filter photometer measurements relative to 8.6 m2 g−1 for photoacoustic ones (Table 1). The latter values are in reasonable agreement with lab-based studies2, though with a significantly broader spread (±41%, k = 1).

Differences in sampling duration among the selected atmospheric studies could potentially bias the average by giving disproportionate weight to short-term studies. Figure 3b separates the data into short-term (days/weeks), medium-term (months), and long-term (year+) studies. Long-term studies have mostly been carried out using traditional filter-based instrumentation such as the MAAP and diverse aethalometer models. The measurements are restricted to a few wavelengths due to the single-wavelength nature of the MAAP and reporting of MACBC at higher wavelengths to avoid brown carbon or dust absorption. On the other hand, short-term studies allow for the use of more “experimental” equipment, where results are reported at multiple wavelengths and with greater accuracy. The short-term character of these campaigns also allowed studies to capture snapshots of certain types of aerosol mass, whereas long-term studies showed a deviation of values often between 1 ≤ Eabs ≤ 2 (except for BB-dominated measurement studies, see Fig. 3c). Despite this, the spread in the MAC across the medium- and long-term studies is very similar, primarily differing in terms of the range of MACBC values observed within a given study, which is smaller for the shorter studies.

When the BC coating was removed using a thermodenuder or a solvent, MACBC values moved closer to the reference line (Fig. 3c), with a larger shift observed for filter studies. In general, removing the coating of BC resulted in values for the MAC at the lower end of the broader set of measurements and consistent with laboratory measurements2. By contrast, cases including mostly biomass burning smoke were at the upper end of the broader set of measurements, with estimated absorption enhancement typically around 1.8 and up to a factor of 3.0 (Table 1). Note, however, that many of these measurements were made with filter photometers, with the single photoacoustic measurement being the highest of the set. As such, it is recommended that the instruments used to measure biomass burning plumes be diversified in the future. In both cases, MAC observations overlap with the broader range of ambient measurements, suggesting a mixture of the features of these different kinds of aerosols.

Uncertainties in mass measurement can additionally contribute to the observed variability in MAC. EC mass based on thermal–optical techniques is a commonly applied standard. Figure 4a and b indicate that the rBC techniques tended to result in slightly higher calculated MAC values than those obtained using EC. Assuming the same absorption, this would imply that the rBC-based metric leads to lower BC mass concentrations than the EC-based. However, there was substantial overlap in the range of MAC from the two types of mass references, and no firm conclusions on the comparability of them can be made from here, in line with observations from earlier studies11. Figure 4b also indicates that the retrieved MAC is largely independent of the temperature protocol since the variability in MAC did not reduce significantly when only one (EUSAAR) of the many protocols was selected (though the EUSAAR mean MAC, 12.1 m2 g−1, is slightly larger than the non-EUSAAR mean MAC 10.0 m2 g−1, the difference is not significant in the context of the variability). This suggests that variability in atmospheric MACEC exceeded that observed between the different protocols.

MAC data are divided based on the absorption measurement technique (a and c, left panels: photoacoustic, b and d, right panels: filter photometers. The latter includes any technique in which a filter is used, see Table 2, including Aethalometers, PSAP, CLAP, MAAP, COSMOS, and optical measurement in TOA analysis). MAC data are further grouped based on mass reference in a and b, and by aerosol type in c and d, to represent remote, urban, and mixed aerosol.

When comparing MAC in urban versus remote environments (Fig. 4c and d), aerosols at the remote measurement sites exhibited more absorption enhancement, though there was considerable overlap in the datasets. This difference was slightly more distinguishable from studies using the photoacoustic technique. It is also noted that photoacoustic techniques are mainly used in urban studies, which complicates the comparison, but also partly explains the observed lower MAC from photoacoustic (Fig. 4a) vs. filter photometer (Fig. 4b) studies. Furthermore, the large variability observed for filter-based only data can be attributed to the cross-sensitivity of these techniques to scattering aerosol species and to uncertainties introduced by different filter artifacts. This poses an issue for long-term absorption measurements by means of filter-based instrumentation that can only be improved by implementing SI-traceable calibration protocols for these kinds of instruments and by harmonizing the correction algorithms for the different measurement artifacts.

Discussion

To summarize the current state-of-the-art, we have systematically searched using keywords in free science databases, broadening our search with academic search engines and citation network tools, to find the studies that reported aerosol mass-absorption cross-section values based on separate, direct absorption and BC mass measurements. We do not claim our review to be complete, and, for example, only English-language literature has been included. We also limited our study to (1) atmospheric MAC (eliminating studies of particular BC sources or solely laboratory studies; but using these to interpret results), (2) black carbon aerosol MAC (e.g. eliminating studies of BrC), and (3) studies that reported sufficient description of the methodology, calibration and data processing such that both absorption and BC mass could be reliably estimated. The latter can be rather subjective to evaluate, but for example, we required that the studies aimed to eliminate the well-known artifacts in filter absorption photometers or charring in TOA. This led to a rejection of a significant fraction of older studies where the methods and calibration protocols were still under development. To enable spatio-temporal comparability of the MAC values, we converted the data to a single wavelength of 550 nm using the assumption AAE = 1. This choice is justified by the defining characteristics of BC but adds to the uncertainty, especially at the shorter wavelengths, where other absorbing species with clearly higher AAE values can contribute to absorption. Keeping these limitations in mind, our aim was to collect a spatially, seasonally, and methodologically representative database of atmospheric MACBC values from a total of 80 scientific papers for further investigation. The downside was that the collection of MACBC values represents a very heterogeneous dataset in terms of their temporal representation or uncertainties, which were not part of the elimination criteria.

The attempts to define a single-value MACBC that could be applied over a range of environmental conditions for practical purposes have proven to be challenging (e.g. refs. 10,28,29). This is a clear follow-up from the high variability in source-specific MACBC values, aerosol atmospheric mixing, and the spread of techniques used for BC measurements that are based on its broad definition, as previously discussed, thereby reflecting the complex nature of BC. Absorption enhancement of coated soot has been studied in the laboratory by using either a vapor condensation system30,31, ozonolysis of organics in an aerosol chamber32, or ozonolysis in a flow-through reactor33, where absorption enhancements between 1.3 and 2.1 were obtained. These values are consistent with the span of MAC values seen in ambient measurements. Similarly, models of different complexity have been used to simulate the effect of coating on absorption enhancement. The Mie core–shell model predicts higher enhancement compared to more complex aggregate models34,35,36,37,38. In general, models agree better for highly coated particles, where the maximum enhancement of 2.5 is reached38. The Chakrabarty and Heinson39 aggregate model predicts the enhancement to follow a 1/3 power-scaling law for mass ratio CPM/CBC. Yet, the degree of absorption enhancement by coating in the atmosphere is not well established34,40,41 and its global importance for the BC-aerosol radiative climate effects remains open until the methodological obstacles can be solved.

The key observation here is the high variability in data, and the results do not support the use of simplistic generalizations or assumptions about MACBC in the atmosphere, and that reliance on any such assumptions will greatly increase the uncertainties in measurements. The weak trends that could be identified from the methodologically filtered data were related to the MAC changes with coating (urban vs. remote, thermal/solvent treated, and biomass plumes). However, the dispersion in the results is substantially larger than in the laboratory. Upward scatter can be attributed to absorption enhancement, a “lensing effect” caused by coating. However, the broader scatter in the thermally denuded (Fig. 3c) and photoacoustic, urban (Fig. 4c) measurements extends well below the bounds from the laboratory references, which cannot be explained simply by absorption enhancement. The technological (instrument type) diversity of the measurements was partly connected to their geographical distribution, with certain techniques being more commonly applied in specific regions or continents. This implied a challenge for separating the ambient variability of MACBC from a possible technological bias. Globally, the most widely applied techniques for atmospheric MACBC quantification were filter-based photometers and thermal-optical analysis, which are both prone to several artifacts.

The complex mixtures of atmospheric BC particles with diverse morphology and size can modify the artifacts in filter-based techniques, contributing to scatter in data. While the BC particle shape is fractal for freshly emitted particles with low organic content, the particles collapse and become more compact and spherically shaped during aging in the atmosphere. The morphology of the BC aggregates is described by an indicator termed the fractal dimension42 which can range from 1.5 (more fractal) to about 2.8 (more spherical), depending on various factors such as dynamics of the collisions and restructuring and condensation of organic matter in the atmosphere after emission, etc.43,44,45. The morphological changes could reduce the apparent absorption—and therefore the MAC—of the aging aerosol. Even if the aggregate collapse does not result in an appreciable change in the absorption of the particles46, and is thus an unlikely source of the typically lower values of MAC from denuded photoacoustic measurements, this collapse does reduce the amount of scattering, which could cause artifacts for filter-based measurements. In contrast, the increasing BC particle size may cause an opposite effect, leading to an increasing MAC11,47,48. Corbin et al.49 performed detailed optical modeling to demonstrate the size-dependency of MAC, connecting it to a size-dependent refractive index (or absorption function E(m)). Overall, the slightly larger scatter in MAC values observed for filter-based measurements relative to direct in situ techniques may reflect the relative magnitudes of these mixed effects (Fig. 3a). Additionally, so-called “tarballs” or “tar brown carbon” from wildfires and residual-fuel combustion can absorb light even at the long wavelengths (≈1000 nm) typically used to quantify BC50,51,52,53; this tar brown carbon can be thermally refractive and appears as EC in some measurements53. For the above reasons, the MAC of BC calculated from measurements of ambient atmospheric samples is expected to vary.

The observed spread is also at least partially attributable to uncertainties in the reference mass methods12. For instance, considering that the reproducibility in TOA doubles for atmospheric samples54 relative to the minimum expected in the laboratory55, this would expand the variability in the retrieved MAC considerably. This is generally supported by Fig. 4b, where EC results extend below the laboratory values, while the SP2 results have a lower bound consistent with uncertainties from laboratory studies.

All the studies cited here corrected for the filter-related artifacts using one of the several available algorithms. However, as suggested by the slightly higher scatter in the MACBC values from the filter-based studies, none of the correction algorithms is suitable or superior for all types of atmospheric aerosols, and thus, further work in this area is needed. Overall, our results highlight the need for harmonized measurement standards and a clear pathway for traceability in atmospheric BC mass concentration and absorption coefficient measurements, which could further refine the technological discrepancies. When quantifying EC mass concentration by means of TOA, cross-sensitivities to tarballs and water-soluble organic compounds can introduce large variability to the measurement that affects the retrieval of MACBC beyond the natural variability. This is not the case for rBC mass measurements, which, according to this study, provide rather insightful values of MACBC (considering limitations of rBC measurement) that can help to explain the natural variability of atmospheric BC particles. Following the recommendations by CEN/TR 180769, the equivalence of candidate methods should also be further defined.

Methodological uncertainties between different sites and studies could additionally be minimized by improving the reporting of the corrections and analysis protocols. Thus, for future studies, we recommend that studies also report:

-

The exact sampling and analysis protocol used for the determination of both absorption and mass concentration, with estimated uncertainties, either by measurements or calculation from indirect measurements.

-

Details on correction algorithms used to compensate for filter-based measurement artifacts such as filter-loading, multiple scattering effects, and cross-sensitivity to scattering. Ideally, raw forms of the data should also be made available alongside corrected data, which would both future-proof the data should better corrections be developed and enhance our ability to compare data.

-

Absorption coefficients and MAC at multiple wavelengths when available.

-

Additional aerosol properties, including SSA, AAE, scattering Ångström exponent (SAE), geometric mean diameter (GMD), or other available, along with the MACBC values.

Methods

Background: defining and measuring black carbon MAC

Bond et al.1 defined BC as a material that strongly absorbs visible light, with a MAC value above 5 m2 g−1 at a wavelength λ = 550 nm for freshly produced particles; is refractory, with a volatilization temperature near 4000 K; is insoluble in water; consists of aggregates of small carbon spherules of <10 to ~50 nm in diameter; and contains a high fraction of graphite-like sp2-bonded carbon atoms. The above definition of BC is recommended for use as a qualitative and descriptive term4. Measurements of BC must exploit one or more of these properties. Due to the potential for cross-sensitivities and/or the requirement of certain assumptions during data analysis, Petzold et al.4 recommend using technique-specific terms for different BC measurement methods, leading to a series of terms. This manuscript generally adopts the definitions of Petzold et al.4. The taxonomy of BC and its measurement, as discussed throughout this section, is summarized in Fig. 5. A wide range of instruments are applied to quantify the various BC-related metrics, with the main techniques used in the studies reviewed herein summarized in Table 2. Independent quantification of BC mass concentration and aerosol absorption coefficient enables quantification of the MACBC of the particles, for which the focus is on those techniques. The methods span several pairings of optical and mass measurements, each with its respective strengths and limitations.

In general, the MAC is the ratio of the particles’ absorption coefficient to some measure of their mass. An assumed MAC is typically used to compute eBC mass concentrations, with that value depending on the specifics of the instrument and analysis routine. The shaded area emphasizes the triangular pathway that connects the eBC to other mass measures.

BC optical measurements

There are two broad classes of BC optical measurements: in situ and filter-based techniques, which can be used to determine the aerosol absorption coefficient.

Aerosol light absorption coefficient (βabs) can be measured in situ, using techniques that directly or indirectly measure βabs of particles suspended in air. The existing indirect method is based on a subtraction of measured light scattering from light extinction, called the extinction-minus-scattering method (EMS). The applicability of EMS is limited in the atmosphere due to a high detection limit and a large uncertainty when the particle absorption is very small compared to their light scattering coefficient (i.e., when the single-scattering albedo [SSA] is high), resulting in the difference between two large numbers56,57. EMS can be set up by separate instruments for measuring light extinction (e.g., CAPS PMex) and scattering (integrating nephelometer) or by a combined cell for measuring light extinction and scattering (CAPS PMssa)57.

Photoacoustic spectrometer (PAS) instruments provide a more direct measure of absorption, based on the pressure fluctuations that result from periodic heating of aerosols by a modulated continuous-wave laser. Often, these pressure fluctuations are amplified in an acoustic resonator58. In contrast, photothermal interferometry (PTI) measures such pressure fluctuations even more directly, using an interferometer rather than relying on the generation of acoustic waves, and therefore does not use acoustic resonators but optical ones. In practice, PAS and PTI instruments often have additional practical differences: PAS instruments typically operate at high frequencies (kHz) compared with PTI (≈100 Hz), which affects key instrumental features such as calibration methods, instrument size and weight, and required laser power59. For example, a PAS instrument using higher laser powers may result in the vaporization of volatile coatings60. The details of these issues depend on the instrument used and have been discussed elsewhere59,61,62,63. PAS and PTI instruments may be calibrated using aerosols at any wavelength11,64, or NO2 at lower visible wavelengths61,63, or O2 in near-IR59. The lowest uncertainties in traceable calibration have been demonstrated with PTI and are around 5% (k = 1)17,19.

Filter-based techniques measure light transmission through a tape collecting the aerosol sample65, initially using an integrating plate, or the sphere method66,67, all methods yielding an attenuation coefficient, βatn. This attenuation coefficient can then be converted to an absorption coefficient, βabs, using a range of corrections and/or assumptions. Originally, filter-based measurements were used to determine the absorption coefficient68 alongside the eBC mass concentration, where an empirical calibration of mass was provided by a total carbon measurement of filters extracted using different solvents69,70. This was performed under the assumption that the chemically refractory carbonaceous material collected on the filter is also the light-absorbing fraction of the collected sample. The parameter relating the mass concentration to the original optical measurement was the mass attenuation cross-section, an instrument-dependent parameter, with a value of 25.4 ± 1.7 m2 g−170 at 633 nm (wavelength71), typical for the attenuation measurement using a collimated laser beam. The mass attenuation cross-section at 880 nm was determined by comparison between different types of aethalometers to be 16.6 m2 g−172. The separation of the mass attenuation cross-section into two multiplicative parameters: mass absorption cross-section (property of the collected sample) and multiple-scattering parameter (property of the instrument) is, to a degree, arbitrary (see, for example, Drinovec et al.73) until a reference measurement is used for the aerosol absorption coefficient measurement61,63.

Deriving light absorption coefficients from attenuation measurements alone requires a range of assumptions and correction methods to compensate for the artifacts associated with filter-loading effects and multiple scattering, which can be either assumed or determined by measurements73,74,75,76. The corrections need information about the aerosol optical properties (additional scattering coefficient measurement or single scattering albedo), mixing state (internally or externally mixed BC), flow rate (filter face velocity), and filter material. Condensable gaseous species, such as water vapor or semi-volatile organics, can pose considerable problems when sampled by filter-based techniques because they condense on (or volatilize from) the filter77,78. This results in measurement artifacts, which existing algorithms cannot correct. It is controversial and debated in the scientific community how much the different algorithms and artifacts in filter-based techniques affect the measured wavelength-dependence of absorption, which is described by the absorption Ångström exponent (AAE).

Absorption is sometimes reported in mass equivalent units of eBC. Petzold et al.4 comments on this, and define equivalent black carbon (eBC) as

“[refers to light-absorption measurements] derived from optical absorption methods, [when combined] with a suitable MAC for the conversion of light absorption coefficient into mass concentration.”

However, to minimize additional uncertainty, those authors recommend reporting the light absorption coefficient rather than the mass concentration. If eBC is reported, the applied MAC value, wavelength, and the procedure used to minimize contributions from other absorbing species should be clearly documented.

Conceptually, there are two steps to infer an eBC mass concentration (CeBC) from the absorption coefficient. First, an optical measurement to determine the light absorption by the particles. Second, the conversion of light absorption into particulate mass by assuming a wavelength-dependent mass absorption cross-section (MAC). Mass absorption cross-sections of pure-BC particles have been estimated as 8.0 ± 0.7 m2 g−1 (k = 1) at 550 nm2, an update to the 7.5 ± 1.2 (k = 1) m2 g−1 determined earlier by Bond and Bergstrom79. However, the MAC of atmospheric BC depends on the wavelength and the particles’ optical properties (refractive index, size, morphology, and particle-coating thickness) and may be larger than 8.0 ± 0.7 m2 g−1 by a factor of up to ~1.841,80.

BC mass measurements

In addition to the strong light absorption of the BC particles, their thermal stability, insolubility, or morphology can be used for BC mass quantification.

The BC mass can be inferred directly using thermal-optical analysis (TOA) methods, yielding the mass of elemental carbon (CEC). EC is used in a number of applications, including air quality, atmospheric measurements, and vehicle/aircraft engine exhaust. Petzold et al.4 define elemental carbon (EC) as

“carbonaceous fraction of particulate matter that is thermally stable in an inert atmosphere to high temperatures near 4000 K and can only be gasified by oxidation starting at temperatures above 340 °C. It is assumed to be inert and non-volatile under atmospheric conditions and insoluble in any solvent81. […The term] EC should be used […] for methods that are specific to the carbon content of carbonaceous matter.”

Only a short description of TOA and EC will be provided here as the technique has been reviewed in detail elsewhere11,82,83,84. Briefly, thermal methods rely on the thermal stability of BC, where EC is operationally defined as the component of the particle that does not evolve in an inert atmosphere at temperatures below 700–1000 °C4,85. By contrast, organic carbon (OC) in thermal methods is operationally defined as the carbon fraction of the sample that evolves under a heating cycle in an inert atmosphere (e.g., helium). In thermal–optical methods, an optical split point is defined as the point where the transmittance of a laser monitoring the sample returns to its original value, due to the production and subsequent gasification of the pyrolytically generated light-absorbing carbon (so-called pyrolytic carbon, assuming identical optical properties as EC, sometimes referred to as “charring”) (see review in Corbin et al.11). The charring of the sample, if not properly corrected for, would be incorrectly reported as EC present in the original sample. Thermal-optical methods have therefore been developed, in which the continuous monitoring of the optical properties (reflectance or transmittance) of the filter sample during the analysis is used to correct for charring86,87. Transmission signal can be used additionally to determine the optical attenuation, and further corrected to the absorption88,89,90. This technique is similar to the filter-based absorption photometers, and likewise suffers from the filter-based artifacts91. Several temperature protocols have been defined worldwide for TOA, which could contribute to variability in measurements. The most commonly used protocols are NIOSH and NIOSH-like, IMPROVE and IMPROVE_A, and EUSAAR_2 protocols86,87,92,93.

Thermal-optical analysis is prone to several sampling and measurement artifacts, arising from: (i) non-uniform particle deposition on the filter, (ii) adsorption of volatile organic compounds on blank filters, (iii) adsorption or loss of volatile compounds on/from the filters during sampling, (iv) catalytic oxidation interactions between OC, EC, and non-carbonaceous material (e.g. metal oxides and inorganic salts) in the sampled particles, and (vi) presence of light-absorbing organic matter (brown carbon, BrC, including tar brown carbons or “tarballs”, TBs) in the sample and the unknown properties of the pyrolyzed material that might affect the laser correction and determination of the split point11,94. The agreement between different laboratories in determining total carbon (TC) mass is usually satisfactory, but large discrepancies have been observed in the determination of the OC and EC mass in atmospheric samples85,95. More recently, Panteliadis et al.96 reported reproducibilities of 11% and 15% (for a coverage factor k = 1; 68% confidence interval) for TC and EC, respectively, from the EUSAAR2 protocol in a careful inter-laboratory comparison using urban samples. For laboratory samples of aircraft-engine exhaust, Sipkens et al.97 reported corresponding uncertainties of 6.5% and 8.5% (k = 1) using a different analytic protocol. These uncertainties may be larger when EC concentrations are low and when the interferences listed above are present. A comprehensive list of inter-laboratory comparisons and studies related to atmospheric measurements and vehicle/aviation emission control using various temperature protocols indicates reproducibility in EC for atmospheric measurements on the order of 15% (k = 1)54.

The thermal-optical measurement of EC is not calibrated by an EC-like calibration sample. The TC and OC are calibrated using an organic solution, deposited on the filters (usually sugars), which are then analyzed. The EUSAAR2 thermal protocol is used in standard EN 16909:2017.

Finally, the term refractory black carbon (rBC) is dedicated to BC measurements that rely on laser-induced incandescence (LII). Petzold et al. 4 defined refractory black carbon (rBC) as

“carbonaceous fraction of particulate matter that is insoluble and vaporizes only at temperatures near 4000 K98. […The term rBC] should be used for measurements derived from [laser-induced] incandescence methods.”

Unlike TOA, the definition of rBC indicates particles that are refractory up to when heated to the point of incandescence in a high-power laser beam. Incandescence does not require particle oxidation or even vaporization, as in TOA. Incandescence is detected as an optical signal and is proportional to the amount of rBC mass99. Refractory black carbon particles start to evaporate at temperatures exceeding about 4000 K after which the incandescence signal starts to diminish. Instruments that measure rBC include the single particle soot photometer (SP2, Droplet Measurement Technologies, USA), based on continuous-wave laser, and pulsed LII systems99,100. However, the Soot Particle Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (SP-AMS, Aerodyne Research Inc., USA), using a vaporizing laser, does not detect incandescent light101 but rather carbon ions. The SP-AMS measurand is therefore closer to EC, according to Petzold et al.4, who defined the signals measured by other mass spectrometers as such.

SP2 uses a continuous high-power intra-cavity laser to achieve LII102,103,104. The particles are detected by four different detectors that are digitized synchronously. The traces these particles leave in the detectors as the particles traverse the laser beam are saved for further analysis. Detection of rBC-containing particles is performed using two different photo detectors that are sensitive to the incandescent light emitted by the particles over a “broadband” wavelength range of 350–800 nm and a “narrow-band” wavelength range of 630–800 nm102. The broadband detector is typically used to determine the rBC mass in the particle, whereas the narrowband detector is, to a lesser extent, used to determine the incandescence temperature of the particle by comparing the broadband and narrowband signals (e.g., ref. 102). The SP2 can detect single particles containing about 0.2 fg (50% counting efficiency) of rBC or more105. At about 0.8 fg, the counting efficiency is close to 100%105. The lower detection limit can be improved by increasing the laser power98.

The accuracy with which the SP2 can determine the rBC mass in particles depends largely on how accurately the instrument can be calibrated, which further depends on the calibration material used105,106,107. The calibration particles used should ideally result in the same instrument response as the aerosol particles the SP2 is going to measure post-calibration, which in most cases is ambient rBC-containing aerosols108. Ambient rBC has been shown to have an almost linear rBC mass to incandescence peak height relationship to particle mass107. Therefore, the most straightforward and preferable method for the SP2-rBC calibration is to select particles according to their mass and relate those particle masses to the incandescence signals recorded by the SP2107,108. The most accurate way to carry out an rBC mass calibration of the SP2 is by using a centrifugal particle mass analyzer (CPMA) coupled with an aerosol electrometer, improving the accuracy of the mass concentration measurement and enabling traceability109. However, not all SP2 users have access to aerosol instruments that enable select calibration aerosols according to their mass. A more often used method is to size-select calibration aerosols for the SP2 according to their electrical mobility using a differential mobility analyzer (DMA). The density of both Aquadag and Fullerene soot varies with the selected electrical mobility diameter, which needs to be taken into account when using this calibration method110. Fullerene soot has been shown to have characteristics that most closely resemble those of ambient urban rBC111. The SP2 is more sensitive to Aquadag than to ambient soot, which needs to be considered in the analysis108,111. When Aquadag is used as a calibration standard, the 8.9 fg (equivalent to 300 nm mobility diameter) incandescence signal needs to be divided by a factor of 0.75 to achieve a fullerene-calibration-equivalent result, which is also constant enough between different SP2 instruments108.

In addition to uncertainties associated with calibration materials, limitations are also due to technical constraints on particle size detection and the mass loss correction methods used. To address the mass loss of rBC outside the lower and upper detection limits of the SP2, two common correction methods are used: fitting and extrapolation, which utilize a lognormal function102,112. The extrapolation method adjusts SP2 rBC measurements by extending the measured size distribution beyond the detection limits, allowing for the calculation of the rBC mass. This approach corrects the measured mass to predict the actual amount of rBC. However, the fitting method performs under the assumption that the true rBC mass size distribution in the submicron range follows a lognormal distribution. Using this assumption, the corrected rBC mass is derived by integrating the mass of a lognormal distribution fitted to the measured rBC size distribution, including adjustments for contributions outside the detection limits. The accuracy of counting efficiency is crucial for precise rBC measurement. Additionally, rBC measurements are influenced by the BC particle shape and particle beam width.

As indicated, the BC mass measured by SP-AMS has characteristics of both CrBC and CEC. The SP-AMS utilizes two independent evaporators to analyze pure organic particles and BC containing particles101. In the laser vaporizer mode, the SP-AMS detects BC particles by activating the laser evaporator, which also causes some organic particles to evaporate. However, this mode does not detect BC-organic mixed particles. The primary source of uncertainty in SP-AMS measurements is the collection efficiency, which is influenced by the divergence of non-spherical particles, as well as the coating composition, geometric shape, and phase distribution113,114,115,116.

BC mass can also be determined by first removing the non-BC mass, either using a thermal denuder (removing non-volatile components) or examining the insoluble fraction. A suitable mass reference method, such as the CPMA-Electrometer Reference Standard (CERMS), the tapered-element oscillating microbalance (TEOM) or the quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) can then be applied to determine the mass of non-volatile PM (\({C}_{{\rm{nvPM}}}\)11,117. Of course, such approaches are only valid for combustion sources that emit negligible mass fractions of refractory compounds such as ash and dust, and are invalid for atmospheric samples containing refractory non-soot materials. Additionally, BC mass can be estimated by Raman spectroscopy or by electron microscopy, which yields information on BC morphology (see, e.g., Petzold et al.4).

Overall, the broad qualitative definition of BC justifies the application of various techniques; however, noting that these results often differ from one another (see the subsection “Data analysis and interpretation”). A summary of the main techniques utilized in the studies reviewed herein is provided in Table 2.

Literature review

Our aim was to study the variability of ambient black carbon (BC) aerosol mass absorption cross-section (MAC). Consequently, we excluded source-specific studies and laboratory-only investigations, though such studies provide some context to the measurements (e.g., indicating that fresh black carbon has a MAC around 8 m2 g−12). Our review was limited to studies that reported both light absorption and one of the measures of BC mass reviewed above. We excluded studies that focused on light-absorbing OC (i.e., BrC) or were severely affected by dust.

We began with a systematic search in all databases listed by the Web of Science, using keywords such as BC, MAC, ambient, atmospheric, measurement, absorption enhancement, review, and mass absorption. This search yielded a large number of publications. From these, we selected the most relevant ones based on subjective evaluations, such as studies reporting extensive or long-term atmospheric MAC measurements, as well as earlier published review articles as a starting point. References cited in these selected peer-reviewed publications were then compiled for further reading.

To expand our article database, we utilized Litmaps (2024), a citation network search tool, and broadened our keyword search using academic search engine tools such as Google Scholar. From an initial pool of approximately 150 prominent studies, we narrowed the scope to those providing sufficient descriptions of methodology, calibration, and data processing, ensuring that both light absorption and BC mass could be reliably estimated. While this evaluation was somewhat subjective, we limited our selection to studies that addressed the well-known method-based artifacts, such as those affecting filter absorption photometers or charring in thermal-optical analysis (TOA). This approach excluded a significant fraction of older studies where methods and calibration protocols were still under development. Our goal was to compile a spatially, seasonally, and methodologically representative database of MAC values for atmospheric BC-containing particles. In total, we extracted 230 MACBC values from 80 studies10,14,15,16,17,18,19,28,29,56,88,89,112,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184, representing a wide range of environments, including urban areas, regional backgrounds, rural locations, and high-altitude sites (Data S1).

Data analysis and interpretation

Depending on the mass measurement technique used to quantify CBC, MAC can be expressed on terms of refractive black carbon (rBC) or elemental carbon (EC):

or

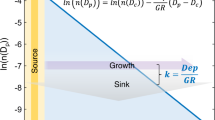

where \({\beta }_{\text{abs}}(\lambda )\text{}\) is implicitly interpreted as the light absorption by rBC (Eq. (1)) or light absorption by EC (Eq. (2)). For purely BC-containing aerosol, often obtained by thermodenuding combustion aerosols, the non-volatile particulate mass concentration, CnvPM, could also be used to quantify the BC mass (Fig. 5). While the concentrations CnvPM, CrBC and CEC may all differ due to instrument calibration or sample physical properties10,11,12. βabs depends not only on the CBC (i.e., CrBC or CEC) but also on the non-BC mass; therefore, the MACBC (i.e., MACrBC or MACEC or MACPM) value is not constant for an atmospheric aerosol with different coatings on identical BC cores. The enhancement of core BC particle mass-absorption cross-section by coating is described by the enhancement factor (Eabs), defined as

The above expressions represent the measurement of MAC from measurements of absorption and mass. When measurements of absorption are reported as equivalent mass (eBC) based on an assumed MAC, then CeBC is defined by rearranging Eqs. (1) and (2):

From the perspective of Eq. (4), the MACeBC is defined as the value that provides the most accurate estimation of BC mass from BC absorption measurements. This MACeBC will vary with particle physico-chemical properties, in particular, their chemical composition and coating thickness. If MACeBC varies only due to coating effects, then MACeBC = Eabs × MACBC,core, and will vary over time (as coatings on a particular particle may vary over time). If other effects, such as instrument artifacts, calibration, or non-BC absorption, play a role, then this equation becomes inaccurate or at least difficult to interpret, as all differences in absorption between the core and the measured particle are hidden in the determination of Eabs.

In practice, when converting the absorption measurements to CeBC, a constant value of MACeBC is often assumed out of necessity4,28,185. Finally, we note that this discussion has focused on mass absorption cross-section and not mass attenuation cross-section, the filter photometer optical-measurement-to-mass calibration factor. These are closely related (but the relationship is complicated, see e.g. Yus-Díez et al.184), and care should be taken to use the correct terminology186.

Zanatta et al.29 estimated the systematic uncertainties in the corrected measurements of the Aethalometers, PSAP, and MAAP to be ±35%, ±25%, and ±15% (k = 1), respectively. Additional errors occur if components other than BC, such as dust or BrC, contribute to absorption, especially at high SSA184. However, due to the lack of measurement standards in many BC metrics, the combined relative uncertainties are often estimated by comparing different instruments, techniques, or similar metrics. These comparisons have shown large discrepancies; for example, Kalbermatter et al.33 found a significant overestimation in the absorption measured by filter-based instruments compared to direct techniques, which was dependent on the amount of coating on BC. Pileci et al.12 compared co-located rBC and EC mass measurements at several European sites and found a substantial systematic bias when comparing the ratio rBC to EC between individual campaigns. They estimated a variability in the mass ratio of roughly ±50% between the campaigns, even though the same TOA protocol (EUSAAR2) and SP2 calibration procedure were used. The difference in particle diameter range measured by the two techniques was one likely cause of this uncertainty. Additionally, differences in BC sources are a plausible explanation for the variable results from the different BC mass metrics, but the underlying causes have remained unclear due to complex cross-correlations and potential biases. Lately, Yus-Díez et al.61 reported a 47% overestimation in the absorption coefficient by the MAAP relative to the PTAAM-2λ at an urban background location in Granada, Spain.

Inter-comparisons performed with laboratory-generated BC particles with more uniform properties and a well-controlled size range have led to better correlations53,105. Slowik et al.13 compared mass measurements of flame-generated coated and uncoated BC particles using an aerosol mass spectrometer-scanning mobility particle sizer (AMS-SMPS), and a single particle soot photometer (SP2), as well as what they called “optically absorbing mass” measured by a multi-angle absorption photometer (MAAP), and a photoacoustic spectrometer (PAS). While a 20% difference between the MAAP and photoacoustic method was found, they concluded that organic coatings on BC changed these instruments’ response non-linearly, depending on the particle morphology, coating thickness, and coating refractive index. A good agreement between BC mass measured by AMS-SMPS and SP2 was obtained only for uncoated particles (±15%). Similarly, Ohata et al.187 estimated the COSMOS uncertainty as ±15% by comparing the measured \({C}_{{\rm{eBC}},{\rm{nvPM}}}\) with the \({C}_{{\rm{rBC}}}\) measured by an SP2. Cross et al. 188 measured 318 different runs of coated and uncoated variable BC particles and compared the BC particle mass measured by CPMA, AMS-SMPS, and LII methods. They found a good agreement between CPMA and AMS-SMPS measurements. Additionally, they found that particle morphology and coating conditions do not affect rBC mass measurement by LII. Corbin et al.11 made a closure between the CPMA Electrometer Reference Mass Standard (CERMS) and TOA methods, showing good agreement between the two techniques measuring CnvPM and CEC once adjusting for the measured 7–10 mass% oxygen content of BC.

From the above, we can expect that the lack of BC measurement standards, the wide range of devices available to perform measurements, and the distinct BC mass metrics all contribute to the uncertainties in the spatial variability of ambient MACBC in this study.

Data availability

This study utilizes previously published data from peer-reviewed literature. Data are harmonized and published along with the manuscript text in a supplement, Data S1, which includes all references to the original data sources.

References

Bond, T. C. et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 5380–5552 (2013).

Liu, F. et al. Review of recent literature on the light absorption properties of black carbon: refractive index, mass absorption cross section, and absorption function. Aerosol Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2019.1676878 (2020).

Michelsen, H. et al. A review of terminology used to describe soot formation and evolution under combustion and pyrolytic conditions. ACS Nano https://doi.org/10.1021/ACSNANO.0C06226 (2020).

Petzold, A. et al. Recommendations for reporting ‘black carbon’ measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 8365–8379 (2013).

Janssen, N. A. et al. Health Effects of Black Carbon (World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2012).

Janssen, N. A. H. et al. Black carbon as an additional indicator of the adverse health effects of airborne particles compared with PM10 and PM2.5. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 1691–1699 (2011).

Ramanathan, V. & Carmichael, G. Global and regional climate changes due to black carbon. Nat. Geosci. 1, 221–227 (2008).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2023).

CEN/TR 18076. CEN/TR 18076: 2024 Ambient Air-Equivalence of Automatic Measurements of Elemental Carbon (EC) and Organic Carbon (OC) in PM (European Committee for Standardization Technical Report, 2024).

Ciupek, K., Quincey, P., Green, D., Butterfield, D. M. & Fuller, G. Challenges and policy implications of long-term changes in mass absorption cross-section derived from equivalent black carbon and elemental carbon measurements in London and south-east England in 2014-2019. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EM00200G (2021).

Corbin, J. C. et al. Closure between particulate matter concentrations measured ex situ by thermal-optical analysis and in situ by the CPMA–electrometer reference mass system. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 54, 1293–1309 (2020).

Pileci, R. E. et al. Comparison of co-located refractory black carbon (rBC) and elemental carbon (EC) mass concentration measurements during field campaigns at several European sites. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 1379–1403 (2021).

Slowik, J. G. et al. An inter-comparison of instruments measuring black carbon content of soot particles. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 41, 295–314 (2007).

Nordmann, S. et al. Measurements of the mass absorption cross section of atmospheric soot particles using Raman spectroscopy. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 12,075–12,085 (2013).

Chow, J. C. et al. Aerosol light absorption, black carbon, and elemental carbon at the Fresno Supersite, California. Atmos. Res. 93, 874–887 (2009).

Flowers, B. A. et al. Optical-chemical-microphysical relationships and closure studies for mixed carbonaceous aerosols observed at Jeju Island; 3-laser photoacoustic spectrometer, particle sizing, and filter analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 10387–10398 (2010).

Healy, R. M. et al. Light-absorbing properties of ambient black carbon and brown carbon from fossil fuel and biomass burning sources. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 6619–6633 (2015).

Linke, C. et al. A novel single-cavity three-wavelength photoacoustic spectrometer for atmospheric aerosol research. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 9, 5331–5346 (2016).

Yang, M., Howell, S. G., Zhuang, J. & Huebert, B. J. Attribution of aerosol light absorption to black carbon, brown carbon, and dust in China—interpretations of atmospheric measurements during EAST-AIRE. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 2035–2050 (2009).

Moosmüller, H. & Arnott, W. P. Particle optics in the Rayleigh regime. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1995 59, 1028–1031 (2009).

Helin, A. et al. Variation of absorption Ångström exponent in aerosols from different emission sources. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD034094 (2021).

Romshoo, B. et al. Optical properties of coated black carbon aggregates: numerical simulations, radiative forcing estimates, and size-resolved parameterization scheme. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 12989–13010 (2021).

Liu, C., Chung, C. E., Yin, Y. & Schnaiter, M. The absorption Ångström exponent of black carbon: from numerical aspects. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 6259–6273 (2018).

Kirchstetter, T. W., Novakov, T. & Hobbs, P. V. Evidence that the spectral dependence of light absorption by aerosols is affected by organic carbon. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D21208 (2004).

Kong, Y. et al. A review of quantification methods for light absorption enhancement of black carbon aerosol. Sci. Total Environ. 924, 171539 (2024).

Sipkens, T. A. & Corbin, J. C. Effective density and packing of compacted soot aggregates. Carbon 226, 119197 (2024).

Zanatta, M. et al. Effects of mixing state on optical and radiative properties of black carbon in the European Arctic. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 14037–14057 (2018).

Savadkoohi, M. et al. Recommendations for reporting equivalent black carbon (eBC) mass concentrations based on long-term pan-European in-situ observations. Environ. Int. 185, 108553 (2024).

Zanatta, M. et al. A European aerosol phenomenology-5: climatology of black carbon optical properties at 9 regional background sites across Europe. Atmos. Environ. 145, 346–364 (2016).

Bueno, P. A. et al. Photoacoustic measurements of amplification of the absorption cross section for coated soot aerosols. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 45, 1217–1230 (2011).

Shiraiwa, M., Kondo, Y., Iwamoto, T. & Kita, K. Amplification of light absorption of black carbon by organic coating. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 44, 46–54 (2010).

Schnaiter, M. et al. Absorption amplification of black carbon internally mixed with secondary organic aerosol. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 110, D19204 (2005).

Kalbermatter, D. M. et al. Comparing black-carbon- and aerosol-absorption-measuring instruments—a new system using lab-generated soot coated with controlled amounts of secondary organic matter. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 15, 561–572 (2022).

Liu, C., Li, J., Yin, Y., Zhu, B. & Feng, Q. Optical properties of black carbon aggregates with non-absorptive coating. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 187, 443–452 (2017).

Romshoo, B. et al. Importance of size representation and morphology in modelling optical properties of black carbon: comparison between laboratory measurements and model simulations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 15, 6965–6989 (2022).

Romshoo, B. et al. Improving the predictions of black carbon (BC) optical properties at various aging stages using a machine-learning-based approach. EGUsphere 1–34 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2023-2400 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Improved representation of black carbon mixing structures suggests stronger direct radiative heating. One Earth 8, 101311 (2025).

Wu, C., Wu, D. & Yu, J. Z. Quantifying black carbon light absorption enhancement with a novel statistical approach. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 289–309 (2018).

Chakrabarty, R. K. & Heinson, W. R. Scaling Laws for light absorption enhancement due to nonrefractory coating of atmospheric black carbon aerosol. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 218701 (2018).

Cappa, C. et al. Radiative absorption enhancements due to the mixing state of atmospheric black carbon. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.1223447 (2012).

Fierce, L. et al. Radiative absorption enhancements by black carbon controlled by particle-to-particle heterogeneity in composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 5196–5203 (2020).

Köylü, ÜÖ, Faeth, G. M., Farias, T. L. & Carvalho, M. G. Fractal and projected structure properties of soot aggregates. Combust. Flame 100, 621–633 (1995).

Ghazi, R. & Olfert, J. S. Coating mass dependence of soot aggregate restructuring due to coatings of oleic acid and dioctyl sebacate. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 47, 192–200 (2013).

Gwaze, P. et al. Comparison of three methods of fractal analysis applied to soot aggregates from wood combustion. J. Aerosol Sci. 37, 820–838 (2006).

Wentzel, M., Gorzawski, H., Naumann, K.-H., Saathoff, H. & Weinbruch, S. Transmission electron microscopical and aerosol dynamical characterization of soot aerosols. J. Aerosol Sci. 34, 1347–1370 (2003).

Radney, J. G. et al. Dependence of soot optical properties on particle morphology: measurements and model comparisons. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 3169–3176 (2014).

Dastanpour, R., Momenimovahed, A., Thomson, K., Olfert, J. & Rogak, S. Variation of the optical properties of soot as a function of particle mass. Carbon 124, 201–211 (2017).

Khalizov, A. F., Xue, H., Wang, L., Zheng, J. & Zhang, R. Enhanced light absorption and scattering by carbon soot aerosol internally mixed with sulfuric acid. J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 1066–1074 (2009).

Corbin, J. C. et al. Size-dependent mass absorption cross-section of soot particles from various sources. Carbon 192, 438–451 (2022).

Alexander, D. T. L., Crozier, P. A. & Anderson, J. R. Brown carbon spheres in East Asian outflow and their optical properties. Science 321, 833–836 (2008).

Chakrabarty, R. K. et al. Shortwave absorption by wildfire smoke dominated by dark brown carbon. Nat. Geosci. 16, 683–688 (2023).

Cheng, Z. et al. Enhanced light absorption for solid-state brown carbon from wildfires due to organic and water coatings. Nat. Commun. 15, 10326 (2024).

Corbin, J. C. et al. Infrared-absorbing carbonaceous tar can dominate light absorption by marine-engine exhaust. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2, 1–10 (2019).

Vasilatou, K. et al. Aerosol physical characterization: a review on the current state of aerosol documentary standards and calibration strategies. J. Aerosol Sci. 183, 106483 (2025).

Sipkens, T. A. et al. Quantifying the uncertainties in thermal-optical analysis of carbonaceous aircraft engine emissions: an interlaboratory study. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 17, 4291–4302 (2024).

Asmi, E. et al. Absorption instruments inter-comparison campaign at the Arctic Pallas station. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 5397–5413 (2021).

Modini, R. L. et al. Detailed characterization of the CAPS single-scattering albedo monitor (CAPS PMssa) as a field-deployable instrument for measuring aerosol light absorption with the extinction-minus-scattering method. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 819–851 (2021).

Arnott, W. P., Hamasha, K., Moosmüller, H., Sheridan, P. J. & Ogren, J. A. Towards aerosol light-absorption measurements with a 7-wavelength aethalometer: evaluation with a photoacoustic instrument and 3-wavelength nephelometer. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 39, 17–29 (2005).

Corbin, J. C., Moallemi, A., Poitras, D., Sipkens, T. A. & Norooz Oliaee, J. Self-calibrating aerosol absorption measurements using co-located TDLAS and tunable-wavelength photothermal interferometry. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 59, 877–891 (2025).

Langridge, J. M., Richardson, M. S., Lack, D. A., Brock, C. A. & Murphy, D. M. Limitations of the photoacoustic technique for aerosol absorption measurement at high relative humidity. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 47, 1163–1173 (2013).

Yus-Díez, J. et al. Characterization of filter photometer artefacts in soot and dust measurements—laboratory and ambient experiments using a traceably-calibrated aerosol absorption reference. EGUsphere 1–26 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2024-3995 (2025).

Sedlacek, A. J. III Real-time detection of ambient aerosols using photothermal interferometry: folded Jamin interferometer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 77, 064903 (2006).

Drinovec, L. et al. A dual-wavelength photothermal aerosol absorption monitor: design, calibration and performance. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 15, 3805–3825 (2022).

Nakayama, T. et al. Characterization of a three wavelength photoacoustic soot spectrometer (PASS-3) and a photoacoustic extinctiometer (PAX). J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser II 93, 285–308 (2015).

Rosen, H., Hansen, A. D. A., Gundel, L. & Novakov, T. Identification of the optically absorbing component in urban aerosols. Appl. Opt. 17, 3859–3861 (1978).

Fischer, K. Mass absorption coefficient of natural aerosol particles in the 0.4–2.4 μm wavelength interval. Contrib. Atmos. Phys. Beitr. Z. Phys. Atmos. 46, 223–234 (1973).

Lin, C.-I., Baker, M. & Charlson, R. J. Absorption coefficient of atmospheric aerosol: a method for measurement. Appl. Opt. 12, 1356 (1973).

Hansen, A. D. A., Rosen, H. & Novakov, T. Real-time measurement of the absorption coefficient of aerosol particles. Appl. Opt. 21, 3060–3062 (1982).

Gundel et al. Determination of black carbon by thermal analysis. Annu. Rep. 1980 5-26–5–28 (1981).

Gundel, L. A., Dod, R. L., Rosen, H. & Novakov, T. The relationship between optical attenuation and black carbon concentration for ambient and source particles. Sci. Total Environ. 36, 197–202 (1984).

Gundel L. A. Oral communication (2015).

Hansen, A. D. A. The Aethalometer Manual, 208 pg. (2005).

Drinovec, L. et al. The ‘dual-spot’ Aethalometer: an improved measurement of aerosol black carbon with real-time loading compensation. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 1965–1979 (2015).

Collaud Coen, M. et al. Minimizing light absorption measurement artifacts of the Aethalometer: evaluation of five correction algorithms. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 3, 457–474 (2010).

Presser, C., Conny, J. M. & Nazarian, A. Filter material effects on particle absorption optical properties. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 48, 515–529 (2014).

Weingartner, E. et al. Absorption of light by soot particles: determination of the absorption coefficient by means of aethalometers. J. Aerosol Sci. 34, 1445–1463 (2003).

Cappa, C. D., Lack, D. A., Burkholder, J. B. & Ravishankara, A. R. Bias in filter-based aerosol light absorption measurements due to organic aerosol loading: evidence from laboratory measurements. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 42, 1022–1032 (2008).

Lack, D. A. et al. Bias in filter-based aerosol light absorption measurements due to organic aerosol loading: evidence from ambient measurements. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 42, 1033–1041 (2008).

Bond, T. & Bergstrom, R. Light Absorption by Carbonaceous Particles: An Investigative Review https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820500421521 (2006).

Liu, D. et al. Black-carbon absorption enhancement in the atmosphere determined by particle mixing state. Nat. Geosci. https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2901 (2017).

Ogren, J. A. & Charlson, R. J. Elemental carbon in the atmosphere: cycle and lifetime. Tellus B 35B, 241–254 (1983).

Lack, D. A., Moosmüller, H., McMeeking, G. R., Chakrabarty, R. K. & Baumgardner, D. Characterizing elemental, equivalent black, and refractory black carbon aerosol particles: a review of techniques, their limitations and uncertainties. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 406, 99–122 (2014).

Massabò, D. & Prati, P. An overview of optical and thermal methods for the characterization of carbonaceous aerosol. Riv. Nuovo Cimento 44, 145–192 (2021).

Watson, J. G., Chow, J. C. & Chen, L.-W. A. Summary of organic and elemental carbon/black carbon analysis methods and intercomparisons. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 5, 65–102 (2005).

Schmid, H. et al. Results of the “carbon conference” international aerosol carbon round robin test stage I. Atmos. Environ. 35, 2111–2121 (2001).

Birch, M. E. & Cary, R. A. Elemental carbon-based method for monitoring occupational exposures to particulate diesel exhaust. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 25, 221–241 (1996).

Chow, J. C. et al. The dri thermal/optical reflectance carbon analysis system: description, evaluation and applications in U.S. Air quality studies. Atmos. Environ. Part Gen. Top. 27, 1185–1201 (1993).

Cheng, Y. et al. Mass absorption efficiency of elemental carbon and water-soluble organic carbon in Beijing, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 11497–11510 (2011).

Ram, K. & Sarin, M. M. Absorption coefficient and site-specific mass absorption efficiency of elemental carbon in aerosols over urban, rural, and high-altitude sites in India. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 8233–8239 (2009).

Sciare, J. et al. Characterization of carbonaceous aerosols during the MINOS campaign in Crete, July–August 2001: a multi-analytical approach. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 3, 1743–1757 (2003).

Cheng, Y. & He, K.-B. Measurement of carbonaceous aerosol with different sampling configurations and frequencies. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 2639–2648 (2015).

Cavalli, F., Viana, M., Yttri, K. E., Genberg, J. & Putaud, J.-P. Toward a standardised thermal-optical protocol for measuring atmospheric organic and elemental carbon: the EUSAAR protocol. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 3, 79–89 (2010).

Karanasiou, A. et al. Thermal-optical analysis for the measurement of elemental carbon (EC) and organic carbon (OC) in ambient air a literature review. Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss. 8, 9649–9712 (2015).

Contini, D., Vecchi, R. & Viana, M. Carbonaceous aerosols in the atmosphere. Atmosphere 9, 181 (2018).

Birch, M. E. Analysis of carbonaceous aerosols: interlaboratory comparison. Analyst 123, 851–857 (1998).

Panteliadis, P. et al. ECOC comparison exercise with identical thermal protocols after temperature offset correction—instrument diagnostics by in-depth evaluation of operational parameters. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 779–792 (2015).

Sipkens, T. A. et al. Interlaboratory comparison of particle filtration efficiency testing equipment. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 22, 259–273 (2025).

Schwarz, J. et al. Global-scale black carbon profiles observed in the remote atmosphere and compared to models. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL044372 (2010).

Michelsen, H. A., Schulz, C., Smallwood, G. J. & Will, S. Laser-induced incandescence: particulate diagnostics for combustion, atmospheric, and industrial applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 51, 2–48 (2015).

Snelling, D. R., Smallwood, G. J., Liu, F., Gülder, ÖL. & Bachalo, W. D. A calibration-independent laser-induced incandescence technique for soot measurement by detecting absolute light intensity. Appl. Opt. 44, 6773–6785 (2005).

Onasch, T. B. et al. Soot particle aerosol mass spectrometer: development, validation, and initial application. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 46, 804–817 (2012).

Schwarz, J. P. et al. Single-particle measurements of midlatitude black carbon and light-scattering aerosols from the boundary layer to the lower stratosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 111, D16207 (2006).

Stephens, M., Turner, N. & Sandberg, J. Particle identification by laser-induced incandescence in a solid-state laser cavity. Appl. Opt. 42, 3726–3736 (2003).

Kondo, Y. et al. Consistency and traceability of black carbon measurements made by laser-induced incandescence, thermal-optical transmittance, and filter-based photo-absorption techniques. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 45, 295–312 (2011).

Laborde, M. et al. Single Particle Soot Photometer intercomparison at the AIDA chamber. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 5, 3077–3097 (2012).

Gysel, M., Laborde, M., Olfert, J. S., Subramanian, R. & Gröhn, A. J. Effective density of Aquadag and fullerene soot black carbon reference materials used for SP2 calibration. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 4, 2851–2858 (2011).

Moteki, N. & Kondo, Y. Dependence of laser-induced incandescence on physical properties of black carbon aerosols: measurements and theoretical interpretation. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 44, 663–675 (2010).

Laborde, M. et al. Sensitivity of the Single Particle Soot Photometer to different black carbon types. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 5, 1031–1043 (2012).

Dickau, M. et al. Demonstration of the CPMA-Electrometer System for calibrating black carbon particulate mass instruments. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 49, 152–158 (2015).

Gysel, M. et al. Technical Note: the single particle soot photometer fails to reliably detect PALAS soot nanoparticles. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 5, 3099–3107 (2012).

Baumgardner, D. et al. Soot reference materials for instrument calibration and intercomparisons: a workshop summary with recommendations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 5, 1869–1887 (2012).

Laborde, M. et al. Black carbon physical properties and mixing state in the European megacity Paris. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 5831–5856 (2013).

Collier, S. et al. Influence of emissions and aqueous processing on particles containing black carbon in a polluted urban environment: insights from a soot particle-aerosol mass spectrometer. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 6648–6666 (2018).

Matthew, B. M., Middlebrook, A. M. & Onasch, T. B. Collection efficiencies in an aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer as a function of particle phase for laboratory generated aerosols. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 42, 884–898 (2008).

Tasoglou, A., Subramanian, R. & Pandis, S. N. An inter-comparison of black-carbon-related instruments in a laboratory study of biomass burning aerosol. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 52, 1320–1331 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Highly time-resolved urban aerosol characteristics during springtime in Yangtze River Delta, China: insights from soot particle aerosol mass spectrometry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 9109–9127 (2016).

Shukla, K. & Aggarwal, S. G. Particulate matter measurement techniques. In Handbook of Metrology and Applications (eds Aswal, D. K., Yadav, S., Takatsuji, T., Rachakonda, P. & Kumar, H.) 1749–177 7 (Springer Nature, Singapore, 2023).

Petzold, A. & Schönlinner, M. Multi-angle absorption photometry—a new method for the measurement of aerosol light absorption and atmospheric black carbon. J. Aerosol Sci. 35, 421–441 (2004).

Kondo, Y. et al. Stabilization of the mass absorption cross section of black carbon for filter-based absorption photometry by the use of a heated inlet. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 43, 741–756 (2009).

Miyazaki, Y. et al. Performance of a newly designed Continuous Soot Monitoring System (COSMOS). J. Environ. Monit. JEM 10, 1195–1201 (2008).

Ammerlaan, B. A. J. Technical note: Aerosol light absorption measurements with a carbon analyser—calibration and precision estimates. Atmos. Environ. (2017).

Andreae, M. O. et al. Optical properties and chemical composition of the atmospheric aerosol in urban Guangzhou, China. Atmos. Environ. (2008).

Backman, J. et al. Impacts of volatilisation on light scattering and filter-based absorption measurements: a case study. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 3, 1205–1216 (2010).

Barrett, T. E. & Sheesley, R. J. Urban impacts on regional carbonaceous aerosols: case study in central Texas. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 64, 917–926 (2014).

Budhavant, K. et al. Changing optical properties of black carbon and brown carbon aerosols during long-range transport from the Indo-Gangetic Plain to the equatorial Indian Ocean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 11911–11925 (2024).

Cappa, C. D. et al. Light absorption by ambient black and brown carbon and its dependence on black carbon coating state for two California, USA, Cities in Winter and Summer. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 1550–1577 (2019).