Abstract

Tropical cyclones (TCs) have intensified more rapidly in recent decades, with both the frequency and magnitude of rapid intensification (RI) events increasing. While rising sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are widely recognized as the primary driver behind the intensification trend, the contribution of TC-induced cold wakes—localized ocean surface cooling generated by storms—remains poorly quantified. Using 42 years of global data (1982–2023), we identify a robust decline in cold wake size (~7% per decade), driven mainly by enhanced upper ocean stratification. This reduction weakens the oceanic negative feedback on TC intensification and explains about 13% of the observed global trend in intensification rates. The effect extends to RI events and is particularly pronounced in the western Pacific. These findings reveal a previously underappreciated oceanic process that accelerates TC intensification and facilitates more RI events under climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The intensification of tropical cyclones (TCs), particularly during rapid intensification (RI) events—defined as an increase of intensity of at least 30 kt within a 24-hour period—presents significant challenges for forecasting and poses heightened threats to coastal regions1,2,3. Observational records reveal a concerning trend: TCs have been intensifying more rapidly over recent decades, coinciding with increased frequency of RI events, especially in coastal regions4,5,6,7. Although climate models project a slight decline in overall TC frequency due to global warming8, the risks associated with severe storms continue to escalate9,10. This underscores the urgent need to improve our understanding and forecasting capabilities regarding TC intensification11.

Although anthropogenic forcing is recognized as a major driver of recent intensification trends, our ability to understand and project these changes remains limited7. Environmental conditions are widely considered to play a central role, with factors like low vertical wind shear (VWS), high humidity, and elevated sea surface temperatures (SSTs) known to enhance TC intensification12. However, the contribution of these factors to the long-term intensification trend is less certain. While atmospheric conditions influence regional TC behavior, they do not exhibit the persistent global signals needed to account for the observed widespread intensification pattern5,13. Instead, recent research increasingly points toward changes in oceanic conditions as the primary driver of these global trends7,14,15,16.

The intensification of a TC is fundamentally governed by a balance between energy production and frictional dissipation, which is closely tied to storm intensity and structure17,18,19. While internal dynamics, such as eyewall replacement cycles20, can significantly influence this energy balance and temporarily disrupt the intensification process, how these complex internal processes might respond to global warming remains highly uncertain15.

Another critical factor is the interaction between a TC and its environment, which creates feedback mechanisms that modulate TC intensification21,22. One such mechanism is TC-induced sea surface cooling, commonly referred to as the cold wake, which arises from storm-driven vertical mixing and upwelling in the upper ocean23,24. The cooling beneath the inner-core region of TCs acts as a negative feedback21,25 by suppressing the air-sea enthalpy fluxes that fuel the storm, and is shaped by both the upper ocean structure and the storm characteristics (e.g., its intensity, size, and translation speed24,26,27,28,29). While previous studies have primarily examined the strength of this central cooling, its spatial extent and cumulative cooling—and their potential roles in modulating TC intensification—remain largely underexplored. Notably, recent observations reveal that global warming has deepened summer mixed layers30, and strengthened upper ocean stratification31,32, which tend to stabilize the upper ocean and reduce the cumulative mixing generated by TCs33,34. Therefore, this study aims to investigate whether such enhanced upper ocean stratification has reduced the cold wake’s negative feedback on TC intensification, thereby contributing to the observed increase in TC intensification.

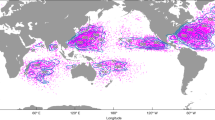

In this study, we analyze 42 years (1982–2023) of observational data across five major TC basins—the Western Pacific (WP), North Atlantic (NA), Eastern Pacific (EP), South Indian Ocean (SI), and South Pacific (SP)—to investigate long-term changes in TC-induced cold wakes. We identify cold wakes based on SST cooling relative to the pre-storm environment, utilizing threshold criteria referring to previous research35 (see Methods). Our analysis is guided by two pivotal questions: Has the oceanic negative feedback associated with cold wakes changed over recent decades? If so, to what extent has this change contributed to the trend of increasing TC intensification? To answer these questions, we first examine the long-term trends and underlying drivers of cold wake shrinkage. Then we quantify the contribution of cold wake size to the observed intensification trend, underscoring the role of oceanic feedbacks as a non-negligible factor in recent TC intensification.

Results

Long-term shrinkage of TC-induced cold wakes

To quantify changes in TC-induced cold wakes, we identified cold wakes using a −0.7°C SST cooling threshold35 for all TCs between 45°S and 45°N, excluding events within 200 km of coastlines to minimize land effects. For each of these events, we calculated key metrics including cold wake size and total SST cooling, derived using a region-of-interest (ROI) algorithm that identifies contiguous regions with cooling stronger than −0.7 °C, then converts their total area into an equivalent radius and integrates the cooling within the ROI as total cooling (see Methods for details). From 1982 to 2023, the cold wake size decreased by a remarkable 27.3 km (approximately 7%) per decade, accumulating to a total reduction of over 20% (Fig. 1a). This trend is robust to the choice of threshold, with similar declines observed using criteria of −0.5°C and −1.0°C (Fig. 1a). Correspondingly, the total SST cooling integrated within the cold wake also shows a significant downward trend (Fig. 1b). A comparison of probability distributions also confirms this statistically significant shift (p < 0.01, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; see Methods) toward smaller and weaker cold wakes in recent decades compared to earlier ones (Fig. 1c, d).

Time series of cold wake size (a) and total cooling (b) are shown for three SST thresholds used to identify cold wakes: −0.5 °C (light blue), −0.7 °C (blue), and −1.0 °C (dark blue). All TC cases reaching 35 kt between 45°S and 45°N are calculated, with coastal effects reduced by excluding cases located within 200 km of the coastline (Methods). Solid lines represent linear trends with 95% confidence intervals shaded. All thresholds exhibit significant downward trends (p < 0.01), and the error bars denote the standard deviation for each year. The probability density distributions of cold wake size (c) and total cooling (d) at the −0.7 °C threshold for two different periods: 1982–2002 (black) and 2003–2023 (blue).

On a regional scale, assessed with 5° latitude × 10° longitude grids (Fig. 2d), this trend manifests as a widespread contraction of cold wakes across most regions. It is important to note that this structural change is not fully captured by metrics focused solely on the storm’s central cooling, typically defined within 100-200 km of the storm center. While some studies have reported a strengthening of this central cooling for intense storms (usually over category 1)26,36, our analysis of all TC cases reveals no significant long-term trend in central cooling itself (Fig. S1a). Instead, our findings show that the overall spatial extent of cold wakes has shrunk, making them more spatially confined. This result aligns with prior oceanic studies that reported a ~30% decline in cumulative sea surface cooling (1982–2016)33 and a ~20% reduction in TC-induced ocean mixing (1982–2018)34. Collectively, these lines of evidence point to a substantial and widespread weakening of TC-induced upper ocean mixing in recent decades.

a Global time series of the potential density difference between the surface and 200 m (Δρ200) averaged over 1982–2017 (Methods). Dashed lines show linear trends, with shaded regions indicating the 95% confidence interval. Error bars denote the standard deviation and the significance (p-value) is shown. b Spatial trends of Δρ200 for 5° latitude × 10° longitude grids, shown with a minimum data record of 20 years. Crosses indicate statistically significant trends (p < 0.1). c Relationship between local trends of Δρ200 and cold wake size across individual grid cells. Each point indicates a region and is colored by ocean basin. The linear fit and global correlation coefficient (r) with p-value are indicated. d Same as (b) but for the spatial trends of cold wake size.

Enhanced upper ocean stratification as the primary driver

To investigate the drivers of the shrinking cold wakes, we first examined the potential role of TC characteristics. Previous studies demonstrate that higher intensity, slower translation speed, and larger wind fields can significantly enhance surface cooling27,28,37. We used R34 (the radius of 34 kt gale force winds)37 as a proxy for wind field size due to its significant correlation with cold wake size (p < 0.01; Fig. S2, S3). Among the storm-related factors we analyzed, none showed compelling evidence for driving the cold wake reduction. TC intensity, despite exhibiting stronger extreme values over time, shows no significant trend in average intensity across all cases (Fig. S4a). TC size decreased by approximately 2 km per decade (Fig. S4b), but this trend is statistically insignificant and far too small to account for the observed cold wake contraction. Translation speed presents a more complex picture: while early studies reported a global slowdown38, recent findings suggest an overall increase39,40, largely due to the poleward migration of TC activity as storms move faster at higher latitudes. To resolve this apparent contradiction, we examined translation speeds separately for cases above and below 20° latitude, finding no consistent trends in either group (Fig. S4c, d). This indicates that local translation speeds have remained largely unchanged and cannot explain the widespread cold wake shrinkage. Collectively, changes in TC characteristics are insufficient to account for the observed long-term contraction of cold wakes.

From an oceanic perspective, recent studies have documented substantial changes in upper ocean structure, particularly enhanced stratification31,32,33 and deepened summer mixed layers30,41, both of which are known to inhibit vertical mixing. To characterize upper ocean stratification, we used a dataset of density anomaly differences between the surface and 200 m (Δρ200) from 1982-2017 (Methods)32. Our analysis revealed a pronounced, long-term increase in upper ocean stability across TC-active regions (Fig. 2a). This strengthening of stratification presents a compelling mechanistic explanation for the shrinking cold wakes31,42, as it stabilizes the water column and directly suppresses the TC-induced vertical mixing responsible for cold wake formation.

To test this hypothesis directly, we performed a regional analysis, calculating trends in both cold wake size and stratification across 5° × 10° grid cells with at least 20 years of data (Fig. 2b, d). The results reveal a remarkably consistent global pattern: upper ocean stratification has strengthened broadly, accompanied by widespread cold wake contraction. More critically, a quantitative analysis across all grid cells confirms that areas experiencing greater increases in stratification exhibit correspondingly larger reductions in cold wake size (p < 0.01; Fig. 2c). Despite persistent uncertainties in observational estimates of upper ocean properties, the consistency of this robust relationship across individual basins offers strong evidence that enhanced stratification is the primary driver of the observed cold wake size decline.

Meanwhile, central SST cooling is also modulated by upwelling associated with cyclonic wind stress divergence near the storm core, driven by the Ekman pumping effect23. Enhanced thermal stratification (increased vertical temperature gradients) can actually improve upwelling efficiency that facilitates the transport of cooler subsurface waters to the surface36. Compared to vertical mixing, upwelling is generally a slower and deeper process that tends to be confined to the storm's inner core, thus playing a greater role in slow-moving and intense TCs23,36,43. Consistent with this, we observe enhanced central cooling specifically in storms exceeding category 1 intensity and in slow-moving storms—both of which exhibit relatively smaller reductions in cold wake size (Fig. S1). This implies that cold wake size functions as an integrative metric, effectively capturing the combined effects of vertical mixing and local upwelling, thereby offering a quantitative measure of the storm’s oceanic feedback.

Cold wake size modulates TC intensification and RI probability

While warmer SSTs generally favor TC intensification, SST cooling beneath the storm core can suppress inner core convection by reducing enthalpy fluxes21. More broadly, an extensive cold wake reduces moist entropy supply over a wider area, weakening the transport of energy and momentum toward the inner core and thereby limiting further intensification. To examine this regulatory effect, we used cold wake size as a proxy for the oceanic negative feedback and assessed its relationship with TC intensity change.

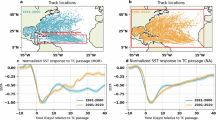

We quantified this relationship by analyzing 24-hour intensification rates for 15,477 intensifying cases with storm intensity exceeding 50 kt (Methods). This threshold is set to exclude weak cases, which typically induce a limited oceanic response and have low inertial stability, making them less sensitive to environmental changes17. Our results reveal a strong, inverse relationship between cold wake size and TC intensification. Storms with smaller cold wakes are far more likely to intensify rapidly. Specifically, TCs with cold wakes smaller than 300 km exhibit an 11.3% probability of RI—nearly 70% higher than the 6.7% probability observed for storms with extensive cold wakes exceeding 600 km (Fig. 3a). This finding aligns with previous observations linking RI to smaller, weaker cold wakes37, providing compelling evidence for an oceanic feedback pathway in RI occurrence.

a Probability of RI as a function of cold wake size, binned in 25-km intervals, with each bin containing at least 20 samples. A linear regression line with 95% confidence interval shaded is shown. b 24-hour intensification rate versus cold wake size, also binned by 25 km intervals. Error bars denote standard deviations within each bin, and a linear fit with 95% confidence interval shaded is shown. Corresponding p-values are annotated. c Spatial distribution of the sensitivity of intensification rate to cold wake size, calculated as the slope of the regression (in kt/24 h per 100 km) within each 10° × 5° (longitude × latitude) grid cell. Only grid cells containing at least 60 samples are displayed to ensure statistical robustness. Grid cells where the regression is statistically significant (p < 0.1) are marked with a cross symbol.

The sensitivity extends beyond RI probability to overall intensification rates. Our analysis demonstrates that smaller cold wakes are associated with a statistically significant increase in the 24-h intensification rate (p < 0.01; Fig. 3b), a negative relationship that remains robust across most ocean basins (Fig. 3c). Exceptions occur in regions with shallow summer mixed layers, such as the eastern Pacific (east of 110°W) and waters near Madagascar44,45, where the correlation is weaker or even reversed. In these warm-SST environments, TCs often generate broader cold wakes during intensification, potentially masking the underlying signal. Despite these regional variations, the global observational evidence clearly indicates that extensive cold wakes suppress TC intensification.

Contribution of shrinking cold wakes to recent TC intensification trends

To identify the dominant drivers of long-term intensification trends, we first assessed the relative importance of key predictors using the Lindeman-Merenda-Gold (LMG) method (Methods)46,47. Based on annual time series of intensification rates and a suite of predictors—including SST, cold wake size, VWS, TC intensity, and TC size—we find that these variables collectively explain over 70% of the interannual variance of intensification rate (R² > 0.70). Among them, oceanic factors, especially SST and cold wake size, serve as the primary contributors (Fig. S5). In contrast, VWS and other parameters exhibit no significant long-term trends and thus contribute minimally to the observed global intensification trend, consistent with previous studies5,15 and our analysis (Fig. S4, S6). While regional atmospheric conditions can influence individual TC events, their role in driving global-scale intensification trends is likely limited. Previous studies have examined the influence of vertical temperature structure and upper-level stratification on TC intensity, but their contributions to the observed long-term trends appear to be relatively minor48. Likewise, although higher mid-level relative humidity is generally associated with rapidly intensifying TCs49, long-term trends of tropical-mean relative humidity, estimated from reanalysis datasets, remain statistically insignificant15, indicating a limited role in driving the observed trend.

These findings underscore the primary role of oceanic changes—which we decompose into SST warming and the contraction of cold wakes50—in driving the observed intensification trend. To quantify the respective contributions, we adopt a physically grounded attribution framework (Methods) inspired by optimal fingerprinting51. The observed intensification trend (\({dI}/{dt}\)) is decomposed into component contributions52, from both SST warming and the reduction in cold wake size (\({R}_{{\rm{C}}}\)), as follows:

Here, \(I\) denotes TC intensification rate (kt per 24 hours), and \({\rm{d}}I/{\rm{d}}t\) represents the decadal trend of this intensification rate. The terms \(d{\rm{SST}}/{dt}\) and \(d{R}_{C}/{dt}\) likewise denote decadal trends of SST and cold wake size. Thus, each term in Eq. (1) represents the decadal trend of the intensification rate, with the partial derivatives describing the sensitivities of the intensification rate (\(I\)) to SST and cold wake size, respectively. The residual term \(\delta\) accounts for contributions from atmospheric variability and other internal storm dynamics not explicitly captured. Thus, using Eq. 1, we can estimate the specific contribution of each factor.

Our attribution analysis reveals that oceanic changes dominate the intensification trend. Based on global multivariate regression, we estimate that a 1°C increase of SST corresponds to a 4.35 kt per 24 hours increase of intensification rate, while a 100 km reduction of cold wake size corresponds to a 0.67 kt per 24 hours increase. Over the past four decades, the global mean intensification rate has increased by approximately 1.38 kt per 24 hours per decade (Fig. 4a). This trend can be attributed to a decadal SST increase of 0.21°C and a cold wake reduction of 26.4 km, yielding estimated contributions of 66.7% from SST and 12.9% from cold wake contraction (Fig. 4b). Together, these oceanic factors explain nearly 80% of the observed intensification trend, with cold wake reduction contributing approximately 0.2 kt per 24 hours per decade.

a Annual mean 24-hour intensification rate from 1982 to 2023. The linear trend is shown with a dashed line and 95% confidence interval (shaded). Corresponding slope and p values are provided in each panel. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. b Relative contributions of SST and cold wake size to the observed trend in (a), based on the decomposition in Eq. (1) (Methods). Bar heights represent the absolute contribution (kt/24 h per decade), with percentage contributions labeled. c, d Similar to a, b but for the calculation of RI events.

We then apply this decomposition method to RI events to estimate the contributing factors to these extreme events. The intensification rate of RI has increased by approximately 1.50 kt per 24 hours per decade (Fig. 4c), higher than the average increase. The combined explanatory power of SST and cold wake size drops to approximately 70%, with SST explaining 57.4% and cold wake size reduction accounting for 13.4% (Fig. 4d). Note that the larger unexplained portion likely reflects the greater influence of internal dynamical factors—such as TC structure changes and eyewall replacement cycles—that are more prominent in extreme intensification events.

To test the robustness of our results and evaluate basin-scale influences, we applied a leave-one-basin-out approach (Methods) to quantify the contributions. This method isolates the impact of each basin by recalculating the global estimate with one basin excluded at a time, ensuring sufficient data for robust estimates. The results show that excluding the WP basin yields the lowest contribution of cold wakes (7.4%), whereas excluding the SI basin yields the highest (17.5%; Fig. S7). This indicates that shrinking cold wakes in the WP basin exerts a stronger contribution than the global average. While we acknowledge that this attribution is subject to uncertainties inherent in observational data, our results underscore that the contraction of cold wakes has made a non-negligible contribution, amplifying the TC intensification under climate change.

Discussion

Our findings reveal a robust, long-term contraction of TC-induced cold wakes over recent decades, primarily driven by enhanced upper ocean stratification that reflects a fundamental weakening of oceanic negative feedback on TC intensification. By quantifying the effect of cold wake size on TC intensification, we estimate that this reduction contributes nearly 0.2 kt per 24 hours per decade to the global intensification trend. At the global scale, this accounts for roughly 13% of the observed increase in intensification rates, highlighting the physical relevance and non-negligible role of cold wake changes. We further verified our results using the ADT-HURSAT dataset (see Methods), which provides globally consistent satellite-based estimates53. Although the long-term intensification trend and sensitivity magnitudes were found to be smaller in ADT-HURSAT, the resulting contribution of cold wake shrinkage remains robust (Fig. S8).

While SST cooling near the inner core is known to directly suppress TC intensification, our analysis highlights that the areal extent of TC-induced cooling (i.e., cold wake size) may serve as a more comprehensive proxy for the oceanic negative feedback. Although the magnitude of central cooling has remained stable—or even increased slightly for intense TCs—the spatial extent and total cooling have clearly declined. Even among storms with comparable central cooling magnitude, those with larger cold wake areas exhibit significantly reduced intensification rates (Fig. S9), confirming that spatial extent remains a critical component of the feedback mechanism. While we acknowledge the inherent difficulty in isolating sensitivities using only observational data, our findings highlight the critical need to assess how cold wake characteristics, such as cooling magnitude and extent, affect TC intensification. Further research utilizing idealized simulations would be valuable for disentangling these mechanisms and quantifying their distinct effects.

Furthermore, the implications extend beyond individual storms. Cold wakes persist across storm sequences, with remnant cooling potentially modulating the environment for subsequent TCs, particularly during TC-active seasons. Previous studies suggest that up to 30% of TCs may experience altered intensification due to lingering cold wakes from prior storms54. Therefore, the observed reduction of cold wake extent may not only weaken immediate oceanic feedback but also diminish the cumulative damping effect on basin-wide TC activity.

As global warming continues to alter upper ocean conditions, the weakening of oceanic negative feedback provides an additional pathway for amplifying TC risks. Cold wakes, as a key regulator of TC intensification, must be accurately represented to improve predictions of extreme TC events55. This oceanic dimension of TC behavior warrants greater attention in both climate projections and operational forecasting56, underscoring the need to advance TC-ocean process simulations.

Methods

TC observations

We use TC observations from the International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS v04r00) database57, focusing on the period of 1982–2023 (42-year), considering the reliability of the data with global satellite coverage. The intensity, location, and motion of TCs are all from IBTrACS. All TCs with maximum surface wind reaching the storm intensity (35 kt), and formed within the tropical domain (30°S–30°N) are considered. We focus on major TC basins: the Western Pacific (WP), North Atlantic (NA), Eastern Pacific (EP), South Indian Ocean (SI), and South Pacific (SP). We calculate the intensification rate for each 6-hour record in IBTrACS, and define RI events as cases where the intensification rate exceeds 30 kt within 24 hours. We further validated our findings using the ADT-HURSAT dataset (1979-2017), which applies the Advanced Dvorak Technique to globally homogenized HURSAT satellite imagery. In this study, we used the 1982-2017 period and compared the intensity characteristics derived from ADT-HURSAT with those from IBTrACS to ensure the robustness of our results.

For TC size, we choose the extent of gale force winds (34 kt, R34) because of its suitability for estimating the wind energy input into the upper ocean and potential hazards58,59. The R34 based on best-track data is used as the average of four quadrants since 200160. Besides, an ERA5 reanalysis-based global TC size dataset with a long-term record is also used (1982-2019)61. The two datasets have a high degree of consistency during their overlapping period (r~0.7, p < 0.01; see Fig. S10). Accordingly, we use the reanalysis R34 data to examine long-term trends. Although reanalysis products may contain uncertainties, they remain essential due to the absence of a comparable global long-term observational record.

Environmental data

The daily SST data, at 1/4° resolution, are obtained from the Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (OISST) based on AVHRR-only datasets62. For the selected TCs, we average over a 1°×1° domain of TC center to obtain SST value, using the record one day prior to the arrival of TCs to describe the SST conditions experienced by TCs. We only consider SST beyond 200 km from the coastline, where the distance to land is based on the IBTrACS. This can minimize land effects, because the complexity of the upper ocean structure, e.g., the presence of continental shelves, would significantly affect the cold wakes2,63. To quantify the upper ocean stratification, we use the dataset of potential density difference between the surface and 200-m depth (1982–2017)32. Anomalies of this indicator (Δρ200) from the monthly climatology are calculated to avoid seasonal bias, and are averaged annually over 5° (latitude) × 10° (longitude).

The vertical wind shear (VWS) is calculated using the wind vectors between 200 hPa and 850 hPa, derived from the fifth-generation reanalysis of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ERA5)64. We calculate VWS as the vector difference between area-averaged horizontal winds at 200 hPa and 850 hPa. The horizontal winds are computed using a filtered background wind field, averaged over both circular (0°-6°) and annular (2°-6°) regions centered on the storm, following prior studies65,66 and expressed as follows (\({\boldsymbol{V}}\) is the area-averaged horizontal wind).

Cold wake identification

To quantify TC-induced cold wake characteristics, we employ metrics such as the central cooling (ΔSST), cold wake size, and total cooling (the integrated cooling over the cold wake area). The analysis considers all TCs between 45°S and 45°N, excluding those within 200 km of coastlines to minimize land effects. For the analysis of cold wake characteristics, we adopt a widely used approach36,67,68. For each TC record, we determine the mean pre-SST as an average from 4 to 10 days before TC passage. The central cooling (ΔSST) is calculated within a 1° × 1° domain. We then define the cold wake field as the difference between the day of the minimum ΔSST (within 4 days after TC passage) and the mean pre-SST field within a 20° × 20° box centered at the TC’s position.

To determine the size of cold wakes, we utilize an ROI (Region of Interest) image processing algorithm35. This algorithm employs a threshold value of −0.7°C to mask the cold wake region (dark blue line in Fig. S11), which is used to identify the ROIs. Note that additional thresholds, such as −0.5°C and −1.0 °C, are also tested for comparative purposes. In addition, we exclude ROIs with centroid locations far from the center at a distance of 8°, as they are deemed less relevant to the TC cold wake (gray line in Fig. S11a). The regions within the ROI boundary (\({S}_{{\rm{ROI}}}\)) are obtained by summing all the grids, and the equivalent cold wake size (\({R}_{{\rm{CW}}}\)) is then calculated based on the total area of ROIs.

To quantify the total cooling of TC-induced cold wake, we calculate the change in SST within the specified region of interest (\({S}_{{\rm{ROI}}}\)) and integrate it over the area (\({S}_{{\rm{ROI}}}\)). The total cooling can represent the potential energy input into the upper ocean69.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test is employed to determine significant differences between distributions or deviations from a reference distribution. This statistical method is applied in Fig. 1c, d, where results indicate a significant shift (all p < 0.01) in the distribution across two periods.

We used the LMG (Lindeman-Merenda-Gold) method to quantify the relative importance of multiple predictors in explaining interannual variations in TC intensification rates46,47. This approach decomposes the total model R2 by averaging over all possible orderings of regressors, providing an unbiased estimate of each variable’s contribution while accounting for multicollinearity. Annual means of SST, cold wake size, VWS, TC intensity, and TC size were included as predictors in a multiple linear regression framework (Fig. S5).

To quantify cold wake size and its relationship with intensification rates, we focus on the intensification phase of TCs reaching at least 50 kt, defined as periods with a 24-hour intensification rate ≥ 0 kt. Including zero-intensification cases (15,477 in total) enlarges the sample and yields more robust estimates, while their exclusion does not affect the main conclusions. Specifically, each term in Eq. 1 is calculated accordingly. We assess the dependence of intensification rate on SST and cold wake size using a multivariate linear regression model, focusing on samples with SST above 26.5°C to reduce the influence of low-SST outliers. To assess long-term trends, we calculate annual means of the relevant metrics and apply linear regression using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method. A multivariate regression model is then used to estimate the sensitivities of TC intensification to both SST and cold wake size. This enables us to quantify the individual contribution of each factor as follows.

To evaluate the robustness and basin-specific influence on global estimates, we performed a leave-one-basin-out sensitivity analysis70,71. For each basin, we excluded its dataset, recomputed the global metric using the remaining basins, and compared the result to the full-dataset estimate (Fig. S7). We note that retaining only one basin at a time would greatly reduce the sample size and amplify regional variability, making it unsuitable for assessing global-scale influences. It could also overemphasize region-specific factors such as VWS, which are beyond the scope of this study.

Data availability

The datasets in this study are all available as follows. IBTrACS dataset (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/ibtracs), ADT-HURSAT dataset (obtained from Kossin et al.53), Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature data (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/optimum-interpolation-sst), environmental variables from the ERA5 reanalysis dataset (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu), an upper ocean density stratification dataset (https://zenodo.org/records/3466123). The cold wake size dataset is in the Supplementary Information.

Code availability

The codes associated with the results of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bhatia, K. T. et al. Recent increases in tropical cyclone intensification rates. Nat. Commun. 10, 635 (2019).

Zhang, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, W. & Xu, J. Coastal Ocean Response and Its Feedback to Typhoon Hato (2017) Over the South China Sea: A Numerical Study. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 124, 13731–13749 (2019).

Balaguru, K. et al. A global increase in nearshore tropical cyclone intensification. Earth’s Future 12, e2023EF004230 (2024).

Lok, C. C. F., Chan, J. C. L. & Toumi, R. Tropical cyclones near landfall can induce their own intensification through feedbacks on radiative forcing. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 184 (2021).

Song, J., Duan, Y. & Klotzbach, P. J. Increasing trend in rapid intensification magnitude of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 084043 (2020).

Liu, K. S. & Chan, J. C. L. Growing threat of rapidly-intensifying tropical cyclones in East Asia. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 39, 222–234 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Recent increases in tropical cyclone rapid intensification events in global offshore regions. Nat. Commun. 14, 5167 (2023).

Zhao, H. et al. Decreasing global tropical cyclone frequency in CMIP6 historical simulations. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl2142 (2024).

Emanuel, K. Response of global tropical cyclone activity to increasing CO2: results from downscaling CMIP6 models. J. Clim. 34, 57–70 (2021).

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change Assessment: Part I: detection and attribution. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 1987–2007 (2019).

Emanuel, K. Will global warming make hurricane forecasting more difficult?Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, 495–501 (2017).

Kaplan, J. & DeMaria, M. Large-scale characteristics of rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic Basin. Weather Forecast. 18, 1093–1108 (2003).

Xu, J. et al. Increasing tropical cyclone intensity in the western North Pacific partly driven by warming Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 15, 310 (2024).

Zhao, H., Duan, X., Raga, G. B. & Klotzbach, P. J. Changes in characteristics of rapidly intensifying Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclones related to climate regime shifts. J. Clim. 31, 8163–8179 (2018).

Bhatia, K. et al. A potential explanation for the global increase in tropical cyclone rapid intensification. Nat. Commun. 13, 6626 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Recent increase in rapid intensification events of tropical cyclones along China coast. Clim. Dyn. 62, 331–344 (2023).

Wang, Y., Li, Y., Xu, J., Tan, Z.-M. & Lin, Y. The intensity-dependence of tropical cyclone intensification rate in a simplified energetically based dynamical system model. J. Atmos. Sci. 78, 2033–2045 (2021).

Guo, X. & Tan, Z. M. Tropical cyclone intensification and fullness: the role of storm size configuration. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098449 (2022).

Wang, Y. & Wu, C. C. Current understanding of tropical cyclone structure and intensity changes ? a review. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 87, 257–278 (2004).

Sitkowski, M., Kossin, J. P. & Rozoff, C. M. Intensity and structure changes during Hurricane Eyewall Replacement Cycles. Mon. Weather Rev. 139, 3829–3847 (2011).

Schade, L. R. & Emanuel, K. A. The ocean’s effect on the intensity of tropical cyclones: results from a simple coupled Atmosphere–Ocean Model. J. Atmos. Sci. 56, 642–651 (1999).

Cione, J. J. & Uhlhorn, E. W. Sea surface temperature variability in hurricanes: implications with respect to intensity change. Mon. Weather Rev. 131, 1783–1796 (2003).

Price, J. F. Upper ocean response to a hurricane. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 11, 153–175 (1981).

Mei, W. & Pasquero, C. Spatial and temporal characterization of sea surface temperature response to tropical cyclones*. J. Clim. 26, 3745–3765 (2013).

Emanuel, K. A. Thermodynamic control of hurricane intensity. Nature 401, 665–669 (1999).

Wang, S. & Toumi, R. Recent tropical cyclone changes inferred from ocean surface temperature cold wakes. Sci. Rep. 11, 22269 (2021).

Mei, W., Pasquero, C. & Primeau, F. The effect of translation speed upon the intensity of tropical cyclones over the tropical ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L07801 (2012).

Huang, P., Lin, I. I., Chou, C. & Huang, R. H. Change in ocean subsurface environment to suppress tropical cyclone intensification under global warming. Nat. Commun. 6, 7188 (2015).

Pun, I.-F., Lin, I. I., Lien, C.-C. & Wu, C.-C. Influence of the Size of Supertyphoon Megi (2010) on SST Cooling. Mon. Weather Rev. 146, 661–677 (2018).

Sallée, J.-B. et al. Summertime increases in upper-ocean stratification and mixed-layer depth. Nature 591, 592–598 (2021).

Li, G. et al. Increasing ocean stratification over the past half-century. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 1116–1123 (2020).

Yamaguchi, R. & Suga, T. Trend and variability in global upper-ocean stratification since the 1960s. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 124, 8933–8948 (2019).

Zhang, X., Xu, F., Zhang, J. & Lin, Y. Decrease of annually accumulated tropical cyclone-induced sea surface cooling and diapycnal mixing in recent decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099290 (2022).

Shi, R. et al. Decreasing trend of tropical cyclone-induced ocean warming in recent decades. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 064013 (2023).

Zhang, J., Lin, Y., Chavas, D. R. & Mei, W. Tropical cyclone cold wake size and its applications to power dissipation and ocean heat uptake estimates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 10177–10185 (2019).

Ma, Z. et al. Strengthening cold wakes lead to decreasing trend of tropical cyclone rainfall rates relative to background environmental rainfall rates. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 131 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Storm size modulates tropical cyclone intensification through an oceanic pathway in global oceans. J. Clim. 38, 891–908 (2025).

Kossin, J. P. A global slowdown of tropical-cyclone translation speed. Nature 558, 104–107 (2018).

Yamaguchi, M., Chan, J. C. L., Moon, I.-J., Yoshida, K. & Mizuta, R. Global warming changes tropical cyclone translation speed. Nat. Commun. 11, 47 (2020).

Kim, S.-H., Moon, I.-J. & Chu, P.-S. An increase in global trends of tropical cyclone translation speed since 1982 and its physical causes. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094084 (2020).

Wu, L., Feng, X. & Wu, L. Trends in the ocean mixed-layer depth in the western North Pacific tropical cyclone basin. Int. J. Climatol. 44, 2011–2020 (2024).

Dac Da, N., Foltz, G. R., Balaguru, K. & Fernald, E. Stronger Tropical Cyclone–Induced Ocean Cooling in Near-Coastal Regions Compared to the Open Ocean. J. Clim. 36, 6447–6463 (2023).

Da, N. D., Foltz, G. R. & Balaguru, K. Observed global increases in tropical cyclone-induced ocean cooling and primary production. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL092574 (2021).

Fiedler, P. C. & Talley, L. D. Hydrography of the eastern tropical Pacific: A review. Prog. Oceanogr. 69, 143–180 (2006).

Han, G. et al. SST Anomalies in the Mozambique channel using remote sensing and numerical modeling data. Remote Sens. 11, 1112 (2019).

Lindeman, R. H. (eds Peter Francis Merenda & Ruth Z. Gold) (Scott, Foresman, Glenview, Ill.:, 1980).

Song, K., Zhan, R., Wang, Y. & Xu, J. Quantifying drivers of long-term changes in tropical cyclone intensification rates over the North Atlantic using the EBDS model. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 074060 (2025).

Done, J. M., Lackmann, G. M. & Prein, A. F. The response of tropical cyclone intensity to changes in environmental temperature. Weather Clim. Dyn. 3, 693–711 (2022).

Wu, L. et al. Relationship of environmental relative humidity with North Atlantic tropical cyclone intensity and intensification rate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L20809 (2012).

Schade, L. R. Tropical Cyclone Intensity and Sea Surface Temperature. J. Atmos. Sci. 57, 3122–3130 (2000).

Zhang, X. et al. Detection of human influence on twentieth-century precipitation trends. Nature 448, 461–465 (2007).

Stansfield, A. M. & Reed, K. A. Tropical cyclone precipitation response to surface warming in aquaplanet simulations with uniform thermal forcing. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 126, e2021JD035197 (2021).

Kossin, J. P., Knapp, K. R., Olander, T. L. & Velden, C. S. Global increase in major tropical cyclone exceedance probability over the past four decades. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 11975–11980 (2020).

Balaguru, K., Taraphdar, S., Leung, L. R., Foltz, G. R. & Knaff, J. A. Cyclone-cyclone interactions through the ocean pathway. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6855–6862 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Limited sea surface temperature cooling due to the barrier layer promoting super Typhoon Mangkhut (2018). Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 2156–2172 (2024).

Wadler, J. B. et al. A review of recent research progress on the effect of external influences on tropical cyclone intensity change. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 12, 200–215 (2023).

Knapp, K. R., Kruk, M. C., Levinson, D. H., Diamond, H. J. & Neumann, C. J. The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 91, 363–376 (2010).

Knaff, J. A., Slocum, C. J., Musgrave, K. D., Sampson, C. R. & Strahl, B. R. Using routinely available information to estimate tropical cyclone wind structure. Mon. Weather Rev. 144, 1233–1247 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Effect of storm size on sea surface cooling and tropical cyclone intensification in the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 36, 7277–7296 (2023).

Knaff, J. A. & Sampson, C. R. After a Decade Are Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Gale Force Wind Radii Forecasts Now Skillful?Weather Forecast. 30, 702–709 (2015).

Zhang, K. & Chan, K. T. F. An ERA5 global climatology of tropical cyclone size asymmetry. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 950–963 (2022).

Huang, B. et al. Improvements of the Daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (DOISST) Version 2.1. J. Clim. 34, 2923–2939 (2021).

Pun, I.-F. et al. Rapid Intensification of Typhoon Hato (2017) over Shallow Water. Sustainability 11, 3709 (2019).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Kurihara, Y., Bender, M. A. & Ross, R. J. An Initialization Scheme of Hurricane Models by Vortex Specification. Mon. Weather Rev. 121, 2030–2045 (1993).

Wang, Y., Rao, Y., Tan, Z.-M. & Schönemann, D. A statistical analysis of the effects of vertical wind shear on tropical cyclone intensity change over the Western North Pacific. Mon. Weather Rev. 143, 3434–3453 (2015).

Jourdain, N. C. et al. Observation-based estimates of surface cooling inhibition by heavy rainfall under tropical cyclones. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 43, 205–221 (2013).

McBride, J. L. & Dare, R. A. Sea surface temperature response to tropical cyclones. Mon. Weather Rev. 139, 3798–3808 (2011).

Emanuel, K. Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years. Nature 436, 686–688 (2005).

Raghavan Sathyan, A., Funk, C., Aenis, T., Winker, P. & Breuer, L. Sensitivity analysis of a climate vulnerability index - a case study from Indian watershed development programmes. Clim. Change Respons. 5, 1 (2018).

Chen, Z. et al. Emergent constrained projections of mean and extreme warming in China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102124 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42130603). We also acknowledge the IBTrACS, ADT-HURSAT and OISST teams, and the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) of the ECMWF for providing the ERA5 reanalysis data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and Y.L. conceived the idea, designed the methodology, and carried out the investigation. Y.Z. was responsible for visualization. Y.L. supervised the study. Y.Z. prepared the original draft, and Y.Z., K.S., and Y.L. contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Shan, K. & Lin, Y. Shrinking cold wakes accelerate tropical cyclone intensification in recent decades. npj Clim Atmos Sci 9, 25 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01300-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01300-9