Abstract

The natural land carbon sink (SLAND) absorbs roughly 25–30% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, thus playing a critical role in offsetting climate warming. In the Global Carbon Budget (GCB), SLAND is estimated using model simulations that isolate the carbon response of land to environmental changes (i.e. rising atmospheric CO2, nitrogen deposition, and changes in climate). However, these simulations assume fixed pre-industrial land cover, failing to represent today’s human-altered landscapes. This leads to a systematic overestimation of forest area, and thus CO2 sink strength, in regions heavily altered by human activity. We present a new process-based approach to estimate SLAND using Dynamic Global Vegetation Models. Our corrected estimate reduces SLAND by ~20% (0.6 PgC yr-1) over 2015–2024, from 3.00 ± 0.94 to 2.42 ± 0.77 PgC yr-1. We incorporate this new SLAND estimate with emissions from land-use change from bookkeeping models, to estimate a net land sink of 1.19 ± 1.04 PgC yr-1, which aligns closely with atmospheric inversion constraints. This downward revision of SLAND reduces the magnitude of the budget imbalance for 2015–2024, indicating a more consistent partitioning of the global carbon budget.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The natural land carbon (C) sink (SLAND) is a major component of the global carbon cycle, absorbing up to one third of anthropogenic CO₂ emissions1. SLAND, also known as the indirect2,3 or passive4 sink, is defined as the land carbon uptake that occurs in response to changes in environmental conditions caused indirectly by human activities, most notably rising atmospheric CO2 concentration, nitrogen (N) deposition, and changes in climate. Therefore, SLAND can be thought of as the carbon response of land to a changing environment, distinct from carbon fluxes caused by direct human land use and management (e.g. deforestation, harvest, af/reforestation). SLAND also plays a vital role in reaching net zero carbon emissions4. It is therefore essential to isolate this flux in order to quantify the natural land sink’s role in carbon budgeting and climate policy.

In the framework of the Global Carbon Budget (GCB) assessments, SLAND is quantified using process-based models, known as Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs). The GCB protocol requires DGVMs to perform a simulation using a fixed pre-industrial land cover but with all other forcings (atmospheric CO2, N deposition, and climate) evolving transiently over the historical period (1700-present)5. However, as agriculture expanded in the last centuries, historical deforestation has substantially decreased the global forest cover, and pre-industrial forest areas were thus much larger than forest areas today in most regions6.

Due to their longer carbon residence times, forests have greater carbon sink capacity than agricultural lands7. In addition to this, forest species are C3 plants, which tend to show a stronger photosynthetic response to elevated atmospheric CO2 than C4 plants such as tropical crops and grasses8. Consequently, forests are expected to take up more carbon than grasslands or croplands under rising CO₂ concentrations. As a result, the GCB global estimate of SLAND, based on simulations with preindustrial, instead of actual forest cover, is expected to be too high. Importantly, however, the fixed land-cover simulation itself remains essential: it provides the only way to isolate the natural land sink from direct land-use and land-cover change emissions. Rather than altering the simulation design, our goal is to refine the calculation of SLAND to better reflect the natural land response under contemporary land cover.”

The overestimation of SLAND from assuming a pre-industrial land cover is referred to as Replaced Sinks and Sources (RSS) (see Table 1 for definitions). It reflects the fact that much of today’s land surface has been altered by deforestation for agriculture and urbanisation, and thus large carbon sinks in cleared and converted forests have been lost. The actual carbon sink capacity of land is thus lower than it would be in a purely natural landscape. Replaced sinks/sources have been first singled out by Strassmann et al. (2008)9, quantified as part of the synergistic terms of land-use and environmental changes by several modeling studies (Gitz and Ciais, 200310; Pongratz et al., 200911; Gasser et al., 202112; Obermeier et al. 202113; Dorgeist et al., 202414), and identified as major source of uncertainty in terrestrial carbon flux estimates (Pongratz et al., 201415 and 202116). Previous studies, including refs. 12,14, have estimated this correction using semi-empirical bookkeeping models (BMs), finding that the SLAND estimated by DGVMs may be overestimated by 0.7 ± 0.6 PgC yr-1, for the period 2012–2021.

While BMs are valuable for tracking direct land-use change emissions (ELUC), in general they do not simulate the underlying processes governing vegetation dynamics, soil carbon turnover, or interactions with environmental drivers. In contrast, DGVMs explicitly resolve biogeochemical and physiological vegetation processes, allowing them to simulate how the land carbon cycle responds to changing CO2, climate, and nitrogen deposition over time. Additionally, the ensemble used in the GCB includes ~20 DGVMs, offering a broader and more diverse representation than the two global bookkeeping models that provide estimates of RSS. DGVMs thus offer a more suitable basis for correcting the SLAND bias for several reasons: they explicitly simulate the underlying processes driving carbon uptake, are more numerous in the GCB ensemble than bookkeeping models, and it is more coherent for the models used to estimate SLAND to also correct for their own bias.

A previous study used DGVMs with additional idealised simulations to estimate the land-cover induced bias in SLAND, and found a correction of comparable magnitude to BM studies (0.8 ± 0.3 PgC yr-1)13. This correction was applied to achieve greater consistency between the estimates of ELUC and the SLAND (Walker et al., 202417). Technically, the quantity estimated by that approach includes not only the RSS effect, i.e. the bias in SLAND due to historical changes in land cover, but also an additional term representing the environmental influence on ELUC. This second term accounts for the fact that emissions from land-use transitions (e.g. deforestation) can vary depending on how vegetation and soil carbon stocks have already responded to environmental changes such as elevated CO2. This component has been described in earlier simulation-based studies (e.g., Pongratz et al., 201415; Dorgeist et al., 202414) as part of the synergistic effects of land-use and environmental drivers. We use the terminology from those studies and refer to this second component as δL. The total effect (RSS + δL) is sometimes labelled as the “Loss of Additional Sink Capacity” (LASC), though definitions vary across the literature. Given this ambiguity, we avoid using LASC here and instead treat its components separately: we correct SLAND for the RSS effect, which directly relates to biases in the GCB estimated natural sink.

In this study, we introduce a new approach to correct the SLAND for the bias caused by RSS, using DGVMs. Our approach does not require any additional simulations or changes to the GCB modelling protocol. Instead, we use the subset of DGVMs that simulate separate vegetation, litter, and soil carbon pools at the plant functional type (PFT) level–where PFTs represent groups of plants with similar physiological and ecological traits (e.g. broadleaf trees, needleleaf trees, crops, grasses).

We extract PFT-level net biome production (NBP) from the standard SLAND simulation with fixed pre-industrial land cover, and combine these fluxes with time-varying PFT area fractions from a simulation that includes historical land use and land cover change (see “Methods”). This enables us to reconstruct an estimate of SLAND that reflects the response of the land to environmental drivers (CO2, climate, N deposition) under realistic land cover conditions, while excluding the direct effects of land-use change. Importantly, we cannot use the simulation with changing CO2, N deposition, climate, and land-use and land-cover change directly, since it contains both SLAND and the direct land-use change flux.

Our aim is to improve how SLAND is derived from the existing GCB simulations by reconstructing the natural sink on realistic land cover using PFT-resolved fluxes. This approach does not require changes to the simulation protocol itself, but it does motivate enhanced model outputs, particularly PFT-level carbon fluxes, that would allow more accurate and consistent SLAND estimates in future assessments. We introduce a proof-of-concept method that reconstructs SLAND using PFT-resolved fluxes and present-day land cover, thereby correcting the bias caused by RSS. This approach uses existing outputs from a subset of DGVMs and requires no additional simulations. Ideally, all DGVMs in the GCB would provide PFT-level outputs, but model development is relatively slow. We therefore also provide recommendations for implementing an interim correction across the ensemble until such outputs become standard.

Results

Global bias in the land carbon sink

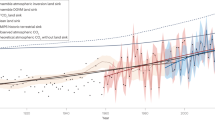

On a global scale, we estimate the mean bias in the natural land sink (i.e. the RSS term), due to the use of pre-industrial land cover, to be 0.57 ± 0.20 PgC yr-1, averaged over 2015–2024, for the subset of models (7 out of 22) used in this study (Fig. 1). There is a large range in global RSS (0.27–0.82 PgC yr-1) driven by differences in NBP rates, preindustrial land cover extent, and land-cover change implementation across models. The calculation of RSS is technically not required to calculate the new SLAND, however, it is useful to give an indication of the bias in previous GCB reports. For 2015–2024 and this subset of DGVMs, SLAND has reduced from 2.74 ± 1.00 PgC yr-1 to 2.17 ± 0.82 PgC yr-1 (21% reduction; Fig. 1b). Our estimated reduction in SLAND is similar to the 23% reduction estimated by ref. 14. RSS has increased over time (Fig. 1), in-line with expanding agriculture and forest loss18 as well as continuing environmental changes.

a shows the average decadal mean global bias in SLAND (equivalent to the Replaced Sinks and Sources, RSS) estimated from the subset of GCB DGVMs that provide PFT-level NBP (coloured lines). The black line shows the multi-model mean. b shows how correcting for the RSS bias impacts global SLAND for the same model subset. The shading indicates the 1σ spread among model estimates.

Regional bias in the land carbon sink

The RSS is a global phenomenon with all regions and continents impacted. There are major hotspots, however, including the Eastern USA, India, Southeast Asia, and South America (Fig. 2). These regions show some of the highest positive biases, consistent with extensive historical land-use change since 1700. The regional values given in the following are estimated using the RECCAP-2 regions, shown in Fig. 2.

The top map (a) shows the mean bias in SLAND (equivalent to the Replaced Sinks and Sources, RSS) averaged across the 7 DGVMs providing PFT-level NBP over the years 2015–2024. Positive values indicate that the natural land sink has previously been overestimated. The bottom map shows the local-scale correlation between RSS and change in forest cover from 1700 to 2024. Correlations are calculated with a 4.5° moving spatial window. Grid-cells with an absolute value of RSS less than 4 gC m−2 yr−1 are greyed out in (b). Ten RECCAP-2 regions are outlined in the maps (black borders).

In the eastern United States, widespread deforestation for agriculture and timber harvesting during the 18th and 19th centuries led to a major loss of forest cover (Fig. 2). Although some forest regrowth has occurred in recent decades, the land surface today bears little resemblance to pre-industrial conditions. As a result, using pre-industrial land cover in the GCB modelling protocol leads to a substantial overestimation of forested area and associated sink capacity (115 ± 42 TgC yr-1, 4.2 ± 1.5 gC m-2 yr-1, over 2015–2024 in North America for the subset of DGVMs; Supplementary Fig. 1).

In South Asia, rapid agricultural expansion, particularly over the last century, has converted large areas of forest to cropland and pasture (Fig. 2). This change is reflected in a large positive RSS in the region (54 ± 44 TgC yr-1, 11.3 ± 9.2 gC m-2 yr-1), as the GCB natural land sink simulation assumes greater forest cover than is currently present.

Southeast Asia, especially Indonesia, also shows a pronounced positive bias. This is largely due to the extensive conversion of lowland rainforest to oil palms, which are represented as agricultural areas (crop PFTs) in DGVMs, resulting in a major reduction in forest area. These changes are not captured when using the fixed pre-industrial land cover assumptions, inflating modelled carbon uptake by 90 ± 63 TgC yr-1 (12.3 ± 8.6 gC m-2 yr-1) in the last decade.

In Brazil, particularly the eastern Amazon and parts of the Cerrado, deforestation for cattle ranching and soy production has dramatically reshaped the landscape. There has been widespread forest loss since 1700, which has driven a strong sink bias (Fig. 2). In the southern part of South America, there are regions with a negative bias which correlate with forest loss. This indicates the replacement vegetation (crops and pastures) is a larger carbon sink in the models than the original vegetation would have been. For example, in the IBIS model, replacement by grasslands leads to simulated productivity exceeding that of the forest it replaces (see Supplementary Text and Supplementary Fig. 2). This pattern is likely driven by environmental change; warming and drying trends may have reduced forest productivity and increased tree mortality19, while C4 grasses and crops are better adapted to these conditions and maintain higher net carbon uptake. Overall, the net effect for South America remains a substantial overestimation of SLAND (77 ± 98 TgC yr-1, 4.1 ± 5.2 gC m-2 yr-1) in modelled outputs.

In contrast, parts of Europe show a negative land sink bias, where modelled uptake is lower than expected. This occurs in areas where forest cover has increased since 1700 due to agricultural abandonment and reforestation, particularly in parts of central and eastern Europe. In these cases, the use of fixed pre-industrial land cover underestimates today’s actual forest extent, resulting in an underestimation of carbon uptake. Overall, Europe has a small positive RSS (9 ± 13 TgC yr-1, 1.2 ± 1.8 gC m-2 yr-1).

The spatial pattern of the RSS shown in Fig. 2 closely resembles the estimate presented by Dorgeist et al. (2024; their Fig. 3c), with similar hotspots in the eastern USA, India, Southeast Asia, and South America. This similarity is expected given that both our approach and that of Dorgeist et al. use the LUH2 dataset to represent historical land-use change. Further, Dorgeist et al. use the GCB ensemble of DGVMs to estimate changes in carbon densities over time, causing another dependency between the two results.

a Relationship between the original SLAND (x-axis) and the estimated Replaced Sinks and Sources (RSS; y-axis) across seven DGVMs with plant functional type (PFT)-level output, shown as decadal means (1960s until 2015–2024). Each point represents a model-decade combination, coloured by decade and with symbols distinguishing models. The dashed black line shows the fixed-effect slope from a linear mixed-effects regression (RSS ~ SLAND with decade as a random effect), with 95% prediction intervals (dotted black lines). The fitted slope (0.19 ± 0.01 PgC yr−1 per PgC yr−1) is highly statistically significant (p < 0.001), and random effects for decade were negligible. b Model-by-model estimates of corrected SLAND for the full GCB ensemble. Grey bars show models that directly calculate the new SLAND using PFT-level outputs. Blue bars show models without PFT-level outputs, for which RSS was estimated using the regression in (a). Dashed outlines depict the original (uncorrected) SLAND values for each model prior to scaling. Ensemble mean values for original and corrected SLAND are shown on the right (orange bars).

Although the larger spatial patterns of RSS are relatively consistent across models, discrepancies do exist in magnitudes and grid-cell scale dynamics (Supplementary Fig. 3). This variation reflects differences in how DGVMs implement initial land and forest cover, land-use transitions, and vegetation responses to environmental change (See Supplementary text: Variation in modelled RSS).

Recommendations for the global carbon budget

Incorporating the RSS correction into the Global Carbon Budget requires a pragmatic approach that balances methodological rigor with the practical constraints of model outputs. Ideally, all DGVMs would provide PFT-level carbon fluxes, enabling a direct calculation of SLAND on transient land cover for each model. However, this will likely take many years to achieve, and a more immediate strategy is needed to provide improved estimates of SLAND in upcoming GCB assessments.

One simple option is to take the mean RSS estimated from the seven models with PFT-level output (0.57 PgC yr-1, for 2015–2024) and subtract this from the ensemble mean SLAND reported in the GCB. However, since the magnitude of RSS varies by model, a model-specific correction would be preferable. A percentage reduction approach could be used, with the seven PFT-enabled models suggesting a mean SLAND reduction of 21 ± 3% for 2015–2024. This has the advantage of scaling the correction to the magnitude of each model’s SLAND, but becomes unstable for models with a small or near-zero land sink (e.g. IBIS in the 1970s; Fig. 3a).

A more robust approach is to exploit the strong linear relationship between RSS and SLAND across models and decades (Fig. 3a). We fitted a linear mixed-effects model of RSS against SLAND with decade as a random effect. The fixed effect slope is 0.19 ± 0.01 (t = 15.3, p < 0.001), explaining ~83% of the variance in RSS (R2 = 0.83). The variance component for decade was estimated as zero, and adding random slopes for decade did not improve model fit (χ2(2) = 0, p = 1), indicating that the relationship is stable across time. These results justify applying a single regression across the entire ensemble and simulation period. Using the fitted regression, we propagated uncertainty with 95% prediction intervals to generate corrected SLAND values for all GCB models without PFT-level output (Fig. 3b, blue bars). Using this method, we estimate a mean RSS of 0.58 PgC yr-1 for the full GCB2025 ensemble, similar to the subset mean, and obtain a corrected global SLAND of 2.42 ± 0.77 PgC yr-1, compared to the original 3.0 ± 0.94 PgC yr-1 (Fig. 3b, orange bars). This correction represents a systematic downward adjustment of ~20%, and provides a consistent, transparent, and operationally feasible method for future GCB updates.

Net land sink and closing the budget

While SLAND cannot be directly observed, it can be indirectly evaluated by comparing bottom-up DGVM estimates with top-down atmospheric constraints. Following the approach of the GCB to estimate the net land sink1, the DGVM SLAND estimates can be combined with independent estimates of ELUC (Net sink = SLAND − ELUC). The GCB2025 reports an average ELUC of 1.37 ± 0.70 PgC yr-1 for the period 2015–2024, based on three bookkeeping models. Combining ELUC with our updated SLAND value, we estimate a net land carbon flux of 1.05 ± 1.04 PgC yr-1 (SLAND - ELUC = 2.42 ± 0.77–1.37 ± 0.70). This is substantially lower than the standard GCB net land sink of 1.63 ± 1.17 PgC yr-1 (Fig. 4).

Bars show the net land carbon sink (indirect and direct human drivers combined) averaged over the years 2015–2024. Bottom-up estimates using the standard GCB approach from GCB2025 and our new approach are shown in green. The dashed outline depicts RSS. Individual top-down estimates based on atmospheric measurements of CO2 (Inversions), fossil CO2 emissions (O2/N2), and ocean sink estimates (Residual) are shown as coloured points, with the grey bar showing the mean across the four estimates.

Importantly, our revised estimate of the net land carbon flux aligns more closely with independent atmospheric benchmarks. Atmospheric inversion models, which infer net surface fluxes from atmospheric CO₂ concentrations, indicate a net land sink of 1.33 ± 0.32 PgC yr-1 over the same period1. Atmospheric O2/N2 measurements, which provide an alternative constraint on land-ocean partitioning of carbon, suggest an even lower sink of 0.83 ± 0.80 PgC yr-11. Additional support for our correction comes from the residual budget estimate, which infers the net land sink by subtracting the observed atmospheric CO2 growth rate (GATM) and ocean carbon uptake (SOCEAN) from fossil fuel emissions (EFOS). This method gives an estimated net land sink of 1.23 ± 0.63 PgC yr-1 (EFOS − GATM − SOCEAN = 9.80 ± 0.49–5.57 ± 0.02– 3.00 ± 0.40 PgC yr-1). Taken together, these comparisons suggest that addressing the land cover bias in SLAND leads to improved consistency between bottom-up and top-down estimates of the net land sink.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that the Global Carbon Budget has systematically overestimated SLAND by approximately 0.6 PgC yr-1 over the past decade due to the methodology used. The overestimation arises from the use of fixed pre-industrial land cover in DGVM simulations employed to estimate SLAND, which assumes extensive forest cover that no longer reflects today’s fragmented and heavily modified landscapes. While previous studies have highlighted this issue using bookkeeping methods12,14, our approach provides a process-based correction using PFT-level outputs from Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs). Using DGVMs enables a more realistic representation of vegetation dynamics and carbon turnover, while remaining compatible with the standard GCB modelling framework. The approach outlined here is not a “quick-fix” or “patch”, but a more accurate method of estimating SLAND, true to the definition of the natural carbon cycle response to changes in atmospheric conditions on transient land cover.

Our estimate of RSS, 0.6 PgC yr-1, is in good agreement with the 0.7 [0.3–1.3] PgC yr-1 reported by Dorgeist et al. (2024)14, based on the BLUE bookkeeping model. In their study, BLUE used DGVM outputs to estimate changing carbon densities over time, so one may expect similar results. However, small discrepancies in RSS are not surprising given differences in model inputs, land-use transition rules, carbon densities of vegetation and soil, or differing product decay rates. Overall, correcting for the RSS bias brings the net land carbon sink into closer agreement with independent top-down estimates, including those based on atmospheric inversions, O2/N2 measurements, and residual budget methods (Fig. 3). These comparisons offer an important indirect benchmark for the credibility of the revised SLAND estimates.

Our revised estimate for the net land carbon sink helps to reduce the mismatch between top-down and bottom-up assessments. When incorporated into the GCB framework, this correction alters the Budget Imbalance (BIM), which is defined as the sum of all sources (EFOS and ELUC) and sinks (GATM, SLAND, and SOCEAN) in the carbon budget. The BIM serves as a measure of our understanding of the global carbon cycle. The standard GCB BIM has a substantial negative BIM in the last decade (−0.4 PgC yr-1 in 2015–2024) which implies an overestimation of sinks, an underestimation of sources, or both (Supplementary Fig. 4). This pattern is consistent with the “weak land carbon sink” hypothesis20, which argues that standard budget approaches may overstate the strength of the terrestrial sink. If we update the BIM by incorporating the SLAND correction described above, the imbalance is reduced to 0.2 PgC yr-1, bringing the budget closer to closure and improving consistency with top-down constraints.

Our approach still depends on the land-cover datasets used in the S3 simulation, including reconstructions of both pre-industrial and historical land-use patterns. These inputs, together with model-specific translation of land-use classes into PFT distributions, introduce uncertainty into the reconstructed SLAND. For recent decades, however, the method benefits from the fact that present-day land cover is far better constrained by satellite observations than land cover in 1700, reducing reliance on purely reconstructed historical states. The accuracy of the method, therefore, depends on two factors developed further below: the quality and consistency of modern land-cover datasets, and the availability of PFT-resolved NBP across DGVMs. Improvements in either area will directly strengthen the robustness of the corrected SLAND estimate.

Some uncertainty arises because DGVMs differ in how they map satellite-derived land cover into model-specific PFTs. For example, estimates of present-day forest cover are not always consistent across models, reflecting differences in the data sources and mapping schemes used by modelling teams. Even so, this uncertainty is smaller and more transparent than that in the traditional GCB protocol, which assumes 1700 land cover with unrealistically high forest fractions, relying on unobserved conditions in 1700. One avenue for improvement is the standardisation of PFT maps across DGVMs, ensuring that all models use harmonised, observation-based inputs for modern land cover. As satellite products continue to improve (e.g. ESA CCI Land Cover, Mapbiomas), such harmonisation would reduce inter-model spread and further strengthen the reliability of the PFT-NBP approach used to correct SLAND. We therefore recommend that all DGVMs should provide PFT-level output in future GCB assessments as a more accurate calculation of SLAND.

A key limitation is that only a subset of models currently provides the PFT-resolved outputs required for this correction. Many DGVMs do not yet track soil and litter carbon pools by PFT, preventing model-specific adjustment without substantial re-coding. Nonetheless, the correction is urgently needed for near-term GCB updates; we cannot wait for all models to be re-coded before addressing the large and systematic SLAND bias. To bridge this gap, we use the relationship between RSS and SLAND to extend the correction to models without PFT-level NBP. We therefore applied regression-based extrapolation (Fig. 3) to extend the correction across the full ensemble, while explicitly propagating uncertainty using prediction intervals and across-model spread.

In parallel, an additional optional simulation with transient land-use change but constant atmospheric CO2, climate, and nitrogen deposition could provide DGVMs with a direct estimate of SLAND + δL on historical land cover. Although this quantity is broader than the SLAND-only correction developed here, such a simulation would help quantify the environmental influence on land-use emissions and support improved attribution of ELUC and δL within the wider GCB framework. In the long term, the most consistent solution will be for all DGVMs to provide PFT-resolved NBP, enabling model-specific corrections. While this approach reduces a known structural bias in SLAND, it should be viewed as a conceptually consistent improvement rather than a definitive accuracy correction, as remaining differences among models largely reflect structural and land-cover uncertainties.

The variability in RSS is primarily controlled by underlying NBP rates. Models with higher forest NBP will generally have higher RSS. Land cover implementation is also important, both in the representation of the pre-industrial state (Supplementary Table 1) and in the magnitude and type of land-cover change. These factors explain why models with similar global SLAND values may show different RSS estimates.

These findings have important implications for how we understand the terrestrial carbon sink. SLAND represents the land response to indirect anthropogenic forcings, particularly elevated atmospheric CO2, N deposition, and climate change, on the existing land cover. By correcting for the unrealistic assumption of pre-industrial vegetation distribution, we obtain a more accurate estimate of SLAND. This improves the consistency of the Global Carbon Budget and strengthens its role as a benchmark for understanding carbon-climate feedbacks. A more realistic SLAND also enhances confidence in comparisons with top-down constraints. Ultimately, improving the representation of SLAND is not only a matter of accounting, it is essential for understanding how natural ecosystems respond to human-induced environmental change. It is also crucial to climate policy, including the evaluation of nature-based solutions and the design of effective mitigation pathways.

Methods

DGVMs and land carbon sink bias correction

The Global Carbon Budget (GCB) estimates the natural land carbon sink (SLAND) using outputs from Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs). Specifically, SLAND is derived from simulation ‘S2’, which includes time-varying atmospheric CO₂ concentration, nitrogen deposition, and climate, but assumes fixed pre-industrial land cover and land management (year 1700 cropland and pasture extent from HYDE/LUH218,21). A separate simulation, ‘S3’, includes the same environmental drivers but also incorporates transient land cover change and land management from HYDE/LUH2 to account for human land-use activities.

In this study, we use output from the 7 (out of a total of 22) DGVMs from the GCB2025 ensemble that provided net biome production (NBP), which is the net land-atmosphere exchange of CO2, on a plant functional type (PFT) basis. These models, CABLE-POP, CLASSIC, GDSTEM, IBIS, iMAPLE, JSBACH, and LPX-Bern, simulate not only biomass but also litter and soil carbon pools for each PFT separately. This feature allows us to combine the simulated PFT-level NBP from the S2 simulation with the transient land cover changes from S3, enabling estimation of a corrected SLAND on realistic land cover. The VISIT model also simulates NBP per PFT but was excluded from the analysis because it shows unrealistically low historical forest area loss in key regions (North America, South America, and Africa; Supplementary Fig. 5) and globally (Supplementary Fig. 6). VISIT maintains excessively high present-day forest cover due to too little deforestation, leading to an anomalously low RSS (0.25 PgC yr−1 over 2015–2024) and a corrected SLAND similar to the uncorrected estimate.

In detail, we calculate the corrected SLAND from the S2 simulation by weighting the PFT-level NBP of each grid cell by the fractional cover of each PFT in the S3 simulation in each year, producing a gridcell-mean NBP that reflects the response of the land biosphere to rising CO₂, nitrogen deposition, and climate variability, while accounting for the changes in PFT distribution induced by historical land-use changes. This corrected SLAND excludes the direct effects of land-use change (which are attributed to ELUC) and thus corresponds to the ideal definition of SLAND that we believe should be used in the GCB. One technical issue is that some PFTs, mainly C3 and C4 crops and pastures are absent from large parts of the globe in the S2 simulation (as cropland expansion was much lower in 1700 than today), and hence cropland NBP cannot directly be estimated. To address this we use the NBP from the C3 and C4 grass PFTs, which are much more widespread, as an estimate of crop/pasture NBP.

To estimate the RSS bias in original SLAND estimates, we calculate, for each model, the difference between the original GCB SLAND estimate and the new, corrected SLAND. Global and regional (based on RECCAP2 defined regions22) bias values are obtained by summing gridcell fluxes globally or regionally. Uncertainty is assessed as the standard deviation across the seven DGVMs.

Mixed-effects regression analysis

We estimate global RSS values for models that do not provide PFT-level output using the SLAND-RSS relationship derived from the DGVM subset. We use the period 1960–2024, as before this period RSS values are near zero. We fitted two linear mixed-effects models to assess the relationship between global RSS and SLAND across models and decades, using decade as a potential random effect. To test whether allowing the slope of the RSS-SLAND relationship to vary by decade improved the model fit, we compared two nested models: (i) a random-intercept model (RSS ~ S2 + (1|Decade)) and (ii) a random-intercept and random-slope model (RSS ~ S2 + (S2|Decade)).

Model comparison was performed with a likelihood ratio test (LRT), which calculates a χ² statistic from the difference in log-likelihoods between the two models, with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of parameters. A statistically significant result would indicate that the more complex model (with random slopes) explains additional variance. In our case, the χ²(2) = 0, p = 1, meaning that the additional slope parameters did not improve fit and that decadal differences in the RSS-SLAND relationship are negligible.

For the DGVMs without PFT data, we calculated the new SLAND (original SLAND - predicted RSS) using the fixed-effects regression. Uncertainty for these corrected values was derived from the 95% prediction interval of the regression. The overall ensemble mean uncertainty was then estimated by combining within-model uncertainty (propagated from the regression prediction intervals) with between-model uncertainty (1σ across models), added in quadrature to give a total ensemble spread.

Data availability

All DGVM data is freely available to download from: https://globalcarbonbudgetdata.org/closed-access-requests.html. The SLAND and RSS estimates are available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17515195 Global Carbon Budget data is available from: https://globalcarbonbudget.org.

References

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global carbon budget 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 17, 965–1039 (2025).

Houghton, R. A. Counting Terrestrial Sources and Sinks of Carbon. Clim. Change 48, 525–534 (2001).

Houghton, R. A., Davidson, E. A. & Woodwell, G. M. Missing sinks, feedbacks, and understanding the role of terrestrial ecosystems in the global carbon balance. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 12, 25–34 (1998).

Allen, M. R. et al. Geological Net Zero and the need for disaggregated accounting for carbon sinks. Nature 638, 343–350 (2025).

Sitch, S. et al. Trends and drivers of terrestrial sources and sinks of carbon dioxide: an overview of the TRENDY project. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 38, e2024GB008102 (2024).

Pongratz, J., Reick, C., Raddatz, T. & Claussen, M. A reconstruction of global agricultural areas and land cover for the last millennium. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 22, (2008).

Pan, Y. et al. The enduring world forest carbon sink. Nature 631, 563–569 (2024).

Chen, C., Riley, W. J., Prentice, I. C. & Keenan, T. F. CO2 fertilization of terrestrial photosynthesis inferred from site to global scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2115627119 (2022).

Strassmann, K. M., Joos, F. & Fischer, G. Simulating effects of land use changes on carbon fluxes: past contributions to atmospheric CO2 increases and future commitments due to losses of terrestrial sink capacity. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 60, 583 (2008).

Gitz, V. & Ciais, P. Amplifying effects of land-use change on future atmospheric CO2 levels: amplifying land-use effects on atmospheric CO2 levels. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 17, (2003).

Pongratz, J., Reick, C. H., Raddatz, T. & Claussen, M. Effects of anthropogenic land cover change on the carbon cycle of the last millennium. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 23, (2009).

Gasser, T. et al. Historical CO2 emissions from land use and land cover change and their uncertainty. Biogeosciences 17, 4075–4101 (2020).

Obermeier, W. A. et al. Modelled land use and land cover change emissions – a spatio-temporal comparison of different approaches. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 635–670 (2021).

Dorgeist, L., Schwingshackl, C., Bultan, S. & Pongratz, J. A consistent budgeting of terrestrial carbon fluxes. Nat. Commun. 15, 7426 (2024).

Pongratz, J., Reick, C. H., Houghton, R. A. & House, J. I. Terminology as a key uncertainty in net land use and land cover change carbon flux estimates. Earth Syst. Dyn. 5, 177–195 (2014).

Pongratz, J. et al. Land use effects on climate: Current state, recent progress, and emerging topics. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 7, 99–120 (2021).

Walker, A. P. et al. Harmonizing direct and indirect anthropogenic land carbon fluxes indicates a substantial missing sink in the global carbon budget since the early 20th century. Plants People Planet https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10619. (2024).

Chini, L. et al. Land-use harmonization datasets for annual global carbon budgets. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4175–4189 (2021).

McDowell, N. et al. Drivers and mechanisms of tree mortality in moist tropical forests. N. Phytol. 219, 851–869 (2018).

Randerson, J. T. et al. The weak land carbon sink hypothesis. Sci. Adv. 11, eadr5489 (2025).

Klein Goldewijk, K., Dekker, S. C. & van Zanden, J. L. Per-capita estimations of long-term historical land use and the consequences for global change research. J. Land Use Sci. 12, 313–337 (2017).

Ciais, P. et al. Definitions and methods to estimate regional land carbon fluxes for the second phase of the REgional Carbon Cycle Assessment and Processes Project (RECCAP-2). Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 1289–1316 (2022).

Acknowledgements

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission. No funding was granted for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O.S. and J.P. designed the study with input from P.F., S.S., C.S., T.G., and P.C. V.A., E.K., J.K., E.M., T.N., Q.S., W.Y., X.U., and S.Z. provided the DGVM data. MOS wrote the first draft and all authors contributed to the writing of the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Sullivan, M., Friedlingstein, P., Sitch, S. et al. An improved approach to estimate the natural land carbon sink. npj Clim Atmos Sci 9, 29 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01302-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01302-7