Abstract

Data-driven deep learning (DL) models often underestimate the intensity of extreme weather and climate events due to the scarcity of extreme samples in training datasets and the smoothing effects of gradient-based optimization. While ensemble prediction methods based on initial condition (IC) perturbations in traditional numerical models have improved extreme event predictions, they often fail in DL frameworks. This is primarily due to limited error growth characteristics and the implicit regularization in DL models, which dampens the amplification of IC perturbations. To overcome this limitation, we introduce a novel IC perturbation scheme based on orthogonal conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation (O-CNOP), integrated into a DL-based ensemble prediction system. The O-CNOP-derived perturbations are obtained through an iterative selection and optimization process, beginning with candidate samples from model simulations under uniform energy constraints. Perturbations are then selected to maximize forecast error growth, guided by ensemble averaging and convergence criteria. We evaluate this method based on four major El Niño events (1982/83, 1997/98, 2015/16, and 2023/24). Results show significant improvements in DL model predictions when initialized in spring, with over a 30% reduction in prediction error for Niño3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies. This AI-enabled O-CNOP framework offers a robust and generalizable approach to ensemble predicting, potentially improving the prediction skill of DL-based weather and climate models for extreme events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the dominant driver of global interannual climate variability, exerting profound impacts on weather, ecosystems, and societies worldwide1,2,3,4. Some El Niño events reach extreme magnitudes, with sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the central–eastern equatorial Pacific exceeding 2 °C5,6. Given its far-reaching importance, extensive efforts have been made to understanding ENSO mechanisms and improving prediction skill7,8,9,10. Current dynamical and statistical prediction models can provide skillful forecasts at lead times beyond six months11,12,13. Some studies have attempted to improve the prediction of extreme El Niño events from the perspective of multi-timescale interactions14,15. However, the intrinsically high nonlinearity of extreme El Niño events remains a major obstacle to successful prediction16,17,18. At present, extending predictive skill beyond one year with traditional approaches remains a major challenge19,20,21.

Deep learning (DL) has recently emerged as a promising approach to ENSO modeling and prediction, showing advantages in capturing nonlinear dynamics and extending lead times to more than 18 months22,23,24,25. However, these advanced DL models still suffer from the spring predictability barrier (SPB) problem: when predictions are initialized in spring, their effective lead times show 5–8 month reduction relative to those initialized in autumn or winter26,27. Moreover, existing DL models often underestimate the intensity of extreme ENSO events and fail to capture transitions from moderate to extreme conditions15,28, including the rapid onset and nonlinear amplification. In particular, spring-initialized predictions substantially underestimate the intensity of extreme El Niño events. Addressing these deficiencies in extreme event prediction represents one of the most pressing challenges in current DL-based climate modeling; it is essential to develop reliable early warning systems for climate disasters prevention and mitigation29,30.

These deficiencies stem from two fundamental limitations inherent to supervised DL frameworks. First, extreme ENSO events are rare, leading to severe class imbalance in training datasets and inadequate representation of extreme dynamics in learned features. This sample bias leads to inadequate representation of extreme event characteristics in the learned feature space. Second, the batch-based gradient descent optimization process inherently suppresses extreme event signatures through statistical averaging. During back propagation, for example, model parameter updates are computed based on mean-gradients across mini-batches, which systematically weakens the distinctive learning signals from rare extreme events when they are mixed with numerous normal samples. This averaging tendency drives models toward predicting more frequent moderate states, effectively smoothing the extreme event amplitude.

Ensemble prediction offers a powerful means of addressing ENSO prediction limitations by quantifying uncertainty and improving robustness31,32. Instead of relying on a single deterministic prediction, this ensemble method generates a collection of predictions by perturbing initial conditions (ICs) or model physics to represent uncertainties in prediction process. Conclusions obtained from large single-model ensemble simulations are more robust than those from ensemble simulations with fewer members33. For example, using an information-theoretic framework and a multiscale stochastic conceptual model, Fang and Chen34 quantify the prediction uncertainty and intrinsic predictability limits of different ENSO event types. Their findings reveal that distinct ENSO events possess different predictability horizons, and that ensemble spread can provide valuable information about predictability, highlighting the importance of uncertainty quantification for understanding ENSO complexity. Traditional ensemble perturbation schemes, such as IC or parameter perturbations, are proven effective in physics-based climate models35,36,37. The success of these schemes relies on the nonlinear and chaotic nature of the climate system, where minor perturbations can amplify rapidly over time and lead to significant, unpredictable conditions, a phenomenon known as the butterfly effect38. Consequently, introducing these perturbations into dynamical models enables the generation of ensemble prediction members, with a certain degree of dispersion.

Extending ensemble prediction schemes to DL frameworks presents a major challenge, as conventional perturbation methods often prove ineffective39. On the one hand, DL models typically contain millions of parameters that lack explicit physical correspondence due to their black-box nature, making systematic parameter perturbations both ambiguous in physics and computationally prohibitive. On the other hand, DL models often exhibit a high degree of robustness for prediction compared to physics-based models. Consequently, they tend to treat small random perturbations in initial fields as noise, which are filtered out; this treatment thereby prevents the necessary error growth required to generate meaningful ensemble spread. As demonstrated by Selz and Craig39, current DL-based models fail to simulate the butterfly effect and erroneously imply unlimited weather predictability. This highlights an urgent need to develop suitable and universal ensemble perturbation methods for DL-based models, particularly to enhance their predictive capabilities for extreme events.

In this paper, we propose an innovative IC perturbation scheme based on the orthogonal conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation approach40,41(O-CNOP) to search for growing-types of initial perturbations. Moreover, a series of O-CNOP-type IC perturbations in various orthogonal subspaces are obtained to construct effective DL-based ensemble prediction systems. Unlike random perturbations that tend to be suppressed as noise in models, O-CNOP-derived perturbations exhibit large-scale, physically meaningful spatial patterns that align with the model-learned representations of key climate modes42,43,44. These structured signals are recognized as dynamically relevant rather than filtered as noise, allowing for their projection onto the model’s intrinsic growth modes and amplification through integration via established feedback processes45,46. This property enables the O-CNOP perturbations to be developed effectively within DL frameworks, in contrast to random perturbations that are rapidly damped. To test effectiveness of the O-CNOP-based ensemble predictions in improving prediction performance of extreme climate events, we select four extreme El Niño events since 1980s and then conduct prediction analyses using an advanced DL model, named 3D-Geoformer24. Our results indicate that the O-CNOP-based ensemble predictions significantly enhance prediction skill for extreme El Niño events, particularly when they are initiated in the challenging boreal spring season.

Results

ENSO prediction skills of the 3D-Geoformer

The 3D-Geoformer is established based on a Transformer architecture with a spatiotemporal self-attention mechanism (detailed in Zhou and Zhang24,26) and has been widely applied in ENSO prediction and predictability studies23,47,48,49,50,51. A key advantage of the 3D-Geoformer lines in its ability to incorporate ENSO-related multivariate three-dimensional (3D) temperature fields that represent the inherent coupling relevant to ENSO dynamics. In this way, the 3D-Geoformer enables a more physically consistent representation of ENSO evolution compared to other DL models with a focus solely on one-dimensional Niño index prediction.

The 3D-Geoformer employs a rolling prediction strategy similar to that used in dynamical models. Specifically, at each prediction step, the model takes multivariate fields during 12 consecutive months as input predictors to predict the same multivariate fields in the next month. The predicted fields are subsequently fed back as input for the next prediction step. In this way, the model enables to capture ocean-atmosphere coupling by allowing for anomaly exchanges between oceanic and atmospheric components each month. The rolling prediction strategy provides a more realistic representation of ocean-atmosphere coupling processes compared to the end-to-end one-step prediction approach commonly used in DL models, which generates multi-month predictions directly from a fixed initial condition.

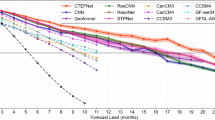

During the 1980–2024 testing period, the 3D-Geoformer demonstrates its high ENSO prediction correlation skills with lead times more than 16 months (Fig. 1a-b), which significantly outperforms traditional physics-based dynamical models. Likewise, the model exhibits high skill in predicting the winter Niño3.4 index (i.e., area-averaged SST anomalies over 5°S–5°N, 170°W–120°W) with a correlation of over 0.7 when predictions are initiated in the spring. Specifically, it shows remarkable accuracy in predicting La Niña and neutral events, but systematically underestimates the intensity of strong El Niño events (Fig. 1c).

a All-season calculated correlation (red) and RMSE (blue) as functions of prediction lead time. b Seasonal variation of correlation skill with lead time and initialization month; contours denote correlation>0.5. c Predicted vs. observed DJF-mean Niño3.4 indices for 1982–2024, with March initializations. Red, blue, and gray dots represent El Niño, La Niña, and neutral years, respectively. Red triangles mark the four strong El Niño events (1982/83, 1997/98, 2015/16, 2023/24).

Control predictions for extreme El Niño events

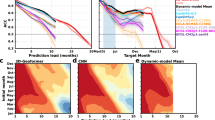

The tropical Pacific ocean-atmosphere coupling exhibits its weakest intensity during boreal spring, leading to significant challenges for climate models in capturing interaction signals during this season. Consequently, the ENSO prediction skill declines rapidly when predictions are initiated in spring, resulting in substantial underestimation of extreme ENSO event intensities. For the four strong El Niño events in 1982/83, 1997/98, 2015/16, and 2023/24, observations show that mature-phase Niño3.4 SST anomalies reach magnitudes of 2.5-3 °C (Fig. 2i-l), and subsurface temperature anomalies in the central-eastern Pacific (represented by upper 150 m averaged temperature anomalies, T150) exceed 7 °C (Fig. 2a-d). However, when predictions are initiated in March for the developing years, the 3D-Geoformer severely underestimates these events (Fig. 2e-h). For example, during the 1982/83 El Niño event, observed Niño3.4 SST anomalies reach 2.5 °C, with T150 anomalies in the eastern equatorial Pacific exceeding 5 °C in late 1982. In contrast, the 3D-Geoformer predictions yield only 0.5 °C for Niño3.4 SST anomalies, which is only 20% of the observed magnitude (Fig. 2a, e, i). The prediction errors are even more pronounced for the 1997/98 and 2015/16 El Niño events, where observed mature-phase Niño3.4 SST anomalies exceed 2.5 °C and T150 anomalies in the eastern Pacific reach over to 4 °C (Fig. 2b-c). However, the 3D-Geoformer predicted Niño3.4 SST and T150 anomalies of only 0.5 °C and 1 °C, respectively (Fig. 2f-g), corresponding to weak El Niño thresholds and mature-phase Niño3.4 errors approaching 2 °C.

a–d Observed equatorial SST anomalies (shading) and T150 anomalies (contours) from March (year 0) to May (year +1). e–h Corresponding March-initialized predictions from ECTL. i–l Niño3.4 SST anomaly evolution: observations (black), deterministic predictions (blue), and ensemble predictions with random perturbations (green).

As discussed above, 3D-Geoformer shows skillful performance in long-term ENSO prediction, yet its ability to predict extreme ENSO events remains limited. With model parameters assumed unbiased, most prediction errors can be attributed to uncertainties in ICs. To reduce the impact of IC uncertainties on prediction accuracy, we attempt to apply stochastic temperature perturbations of ±0.5 °C to the temperature predictors (record as ERandom) and examine whether these disturbances can amplify during model integration to produce effective ensemble predictions. However, as demonstrated in Fig. 2i-l, all ensemble members in ERandom yield nearly identical Niño3.4 SST anomaly trajectories to those in ECTL. This result indicates that random IC perturbations are ineffective for generating useful ensemble spread in DL models.

Dependent validation for 1982/83, 1997/98, and 2023/24 events

Previous studies indicate that only by superimposing growing-type IC perturbations on input predictors can achieve higher ensemble prediction skills52,53. In this study, these growing-type IC perturbations are generated using the O-CNOP method, which represent the perturbations that satisfy certain physical constraints and causes the largest prediction bias at the target time54,55. Conventional CNOP computations typically rely on adjoint models to obtain gradient information of numerical models, which requires enormous computational resources. To address this limitation, a large-sample ensemble optimization method that avoids computing model gradients has been proposed for CNOP computation56. This approach yields outcomes comparable to gradient-based methods when sufficient samples are used. Candidate perturbation samples for the subsequent O-CNOP computations are generated by randomly selecting 100 samples from the historical simulations of each of the 23 CMIP6 models (1850–2014; Supplementary Table 1) and from the Simple Ocean Data Assimilation (SODA, 1871–1979) reanalyses, resulting in a comprehensive dataset of 2400 samples. The calculation workflow is shown in Fig. 3, and additional details can be found in the Methods section.

We compute the first five O-CNOPs for three strong El Niño events in 1982/83, 1997/98, and 2023/24, resulting in a total of 15 O-CNOP-based IC perturbations. Subsequently, we add these IC perturbations to the temperature predictors in the ECTL to generate 15 ensemble prediction members, and investigate their effects on ENSO ensemble prediction skills. Since the 15 IC perturbations are derived from the 1982/83, 1997/98, and 2023/24 events, the corresponding validations are considered dependent validations. In contrast, the 2015/16 El Niño serves as an independent validation, as it was not included in the O-CNOP construction.

One key advantage of the ensemble-based O-CNOP solving method over the gradient-based approach in the DL framework is its ability to produce O-CNOPs with well-defined spatial structures. This characteristic enables clearer mechanistic interpretation of the results. In addition to this structural clarity, previous work showed that the spatial patterns of CNOPs for ENSO are largely independent of the specific event57. Our results corroborate this finding: the spatial patterns of O-CNOPs in the same order across the three El Niño events display consistent distributions (Supplementary Fig. 1), with spatial correlations among O-CNOPs calculated from different events are above 0.8 for the first three O-CNOPs (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, the ensemble mean of the perturbation fields at the same order exhibits a well-defined large-scale pattern (e.g., Fig. 4).

Specifically, the first O-CNOP (i.e., CNOP1) exhibits a basin-wide warming pattern, with large anomaly centered in the surface central-eastern equatorial Pacific, and the perturbation intensity decreases with increasing depth (Fig. 4a). This perturbation acts to significantly increase the background mean state of the upper ocean thermal condition, providing the necessary heat content preconditioning to the amplification of the initial El Niño anomaly, which allows the prediction to reach the observed extreme intensity that would be otherwise underestimated in the corresponding deterministic model. CNOP2 exhibits a La Niña-like seesaw structure characterized by negative temperature perturbations in the upper-ocean of the eastern Pacific and positive perturbations in the subsurface western Pacific (Fig. 4b). This structure resembles the optimal precursor patterns found at the end of the recharge phase before the onset of strong El Niño events58, which amplifies the subsurface warming anomaly in the western Pacific and triggers rapid El Niño intensification. These physically meaningful perturbations with coherent spatial structures are less likely to be filtered out as noise by the DL model, allowing them to effectively evolve during model integration.

The effectiveness of an ensemble prediction involves a combination of accuracy, reliability, and sharpness. Specifically, accuracy refers to the correspondence between predictions and observations; reliability means the predicted probabilities match the observed frequencies; sharpness quantifies the tightness of the prediction distribution31,59. Note that due to the absence of the butterfly effect in most deterministic DL models, conventional stochastic perturbation schemes fail to generate effective ensemble members as the perturbations do not grow realistically within the DL framework. Consequently, the O-CNOP-based ensemble prediction scheme presented here represents one of the few approaches capable of addressing this fundamental limitation.

Figure 5 illustrates the improved predictions of extreme El Niño events when employing the O-CNOP-based ensemble scheme within the 3D-Geoformer (denoted as ECNOP). In the ECTL predictions, the prediction errors of Niño3.4 SST anomalies during the El Niño mature phase reach 1.5-2 °C when predictions are initiated in March (Fig. 5a-c). In contrast, when 15 O-CNOP-based perturbations are separately added to temperature predictors in ECTL, several ensemble members yield reasonable predictions that exhibit strong correlation with observations, demonstrating skillful predictive performance in both event intensity and temporal evolution (Fig. 5a-c). Additionally, the ensemble spread of the ECNOP predictions exhibits a positively skewed distribution, indicating that most O-CNOP-driven IC perturbations are effectively amplified within the 3D-Geoformer framework, thereby producing stronger El Niño signals compared to the ECTL predictions.

Niño3.4 SST anomaly evolution during (a) 1982/83, (b) 1997/98, and (c) 2023/24 El Niño events from observations (black), deterministic ECTL predictions (thick blue lines), O-CNOP-based ensemble mean (ECNOP; thick red lines), and individual ensemble members (colored thin lines). The thin red, blue, green, yellow, and purple thin lines represent the predictions obtained by adding the CNOP1 to CNOP5 types of IC perturbations, respectively. d Mean Niño3.4 prediction errors for March-initialized predictions of the three events: black for ECTL, green for ECNOP, purple for error reduction percentage (ECNOP vs. ECTL).

Meanwhile, prediction errors in ECTL increase with lead time (Fig. 5d), and the Niño3.4 error can reach approximately 1.5 °C during the mature phase in December. In comparison, the ensemble-mean predictions in ECNOP reduce the error to around 1.0 °C, representing an improvement by about 30%. Notably, the largest improvement occurs in summer, with a 35% error reduction relative to ECTL; this period typically corresponds to the season with the lowest ENSO prediction skill throughout the year (Fig. 1b).

These results highlight the effectiveness for the O-CNOP-based ensemble strategy in enhancing the predictive capability of DL models, particularly under challenging spring-time conditions. From a physical perspective, O-CNOP-based IC perturbations are defined as the most dynamically sensitive perturbations that can grow nonlinearly under the model dynamics. By injecting such targeted perturbations into the initial state, the ensemble is given to a better way to search for the fast-growing directions in the model’s phase space, thereby capturing the potential amplification of small perturbations that are often associated with the onset and evolution of extreme El Niño events. This mechanism effectively compensates for the absence of internal error growth processes (such as the chaotic nature of ENSO event60) that are often underrepresented in deterministic DL models.

Independent validation for the 2015/16 El Niño prediction

To assess the generalizability of the O-CNOP-based ensemble prediction scheme, the 2015/16 El Niño event is used as an independent test case, which is excluded from the O-CNOP computational dataset. As shown in Fig. 6a, the deterministic prediction initiated in March 2015 significantly underestimates the event intensity observed. The predicted Niño3.4 SST anomaly in December 2015 reaches only 1 °C, which is approximately one-third of the observed value. In addition, the cold bias in the equatorial SST anomaly intensifies with lead times and gradually extends from the eastern equatorial Pacific to the entire region east of the dateline, with maximum errors exceeding 2 °C (Fig. 7b, d). Additionally, the subsurface temperature predictions exhibit even larger errors from observations. During the mature phase, observed T150 anomalies exceed 4 °C in the eastern equatorial Pacific (Fig. 7a), with subsurface temperature anomalies reaching over 6 °C (Fig. 8a-c). In contrast, T150 anomalies predicted in ECTL are slightly above 1 °C (Fig. 7b), with subsurface warm anomalies of only around 2 °C (Fig. 8d-f). The ECTL also fails to capture the strong subsurface warming in the central-eastern equatorial Pacific and the accompanying cooling in the western Pacific (Fig. 9a-c). These results indicate that the deterministic prediction made using the 3D-Geoformer cannot reliably reproduce the intensity and structure of this extreme El Niño event when ensemble perturbations are not considered.

a Niño3.4 SST anomaly evolution: observations (black), March-initialized ECTL prediction (thick blue lines), O-CNOP-based ensemble mean (ECNOP; thick red lines), and individual ensemble members (colored thin lines). b Niño3.4 SST prediction errors: ECTL (black), ECNOP (green), and O-CNOP optimization rate (purple).

Incorporating O-CNOP-based IC perturbations into the March-initiated prediction leads to substantial improvements in prediction performance. As shown in Fig. 6a, 12 out of 15 ensemble members predict a stronger El Niño to occur compared to ECTL, with the ensemble-mean Niño3.4 SST anomaly in winter 2015 improved by 0.5 °C. Notably, three members realistically reproduce the evolution of what is observed, with mature-phase Niño3.4 errors below 0.5 °C. Specifically, the ensemble-mean prediction in April 2015 aligns closely with observations, making the most significant improvement relative to ECTL (Fig. 6b). The prediction skill in summer shows greater enhancement than that in winter, with averaged error reductions exceeding 40%. Crucially, the degree of improvement for the independent 2015/16 case matches that for the dependent validation cases presented earlier, indicating that the O-CNOP-based ensemble approach provides consistent and robust prediction skill across distinct El Niño events without a need for case-dependent tuning.

Incorporating O-CNOP-based IC perturbations into the 3D-Geoformer initial conditions also systematically improves the prediction of three-dimensional temperature anomalies. The ECNOP predictions significantly reduce SST errors relative to ECTL in the central-eastern Pacific (Fig. 7d, e) and enhance T150 anomaly intensity during the period from March 2015 to March 2016 (Fig. 7c). Subsurface temperature predictions also show substantial improvement, with maximum anomalies reaching 5 °C, closely matching with observations (Fig. 8b, c, h, i). Furthermore, large temperature anomaly errors in ECTL distributed along the thermocline are effectively reduced from 3–4 °C to within 1–2 °C in ECNOP predictions (Fig. 9).

These results demonstrate that the O-CNOP-based IC perturbations, which represent fast-growing perturbations within the prediction period, enable the generation of physically meaningful ensemble members that capture a broad range of possible ENSO evolution pathways. The consistent prediction improvements across dependent and independent cases highlight the critical role played by dynamically informed perturbations in enhancing DL model performance for extreme El Niño. Moreover, to validate the out-of-sample performance and universality of our O-CNOP-based perturbation method, we further conduct experiments using climate model simulations that are not included in the training set (see Supplementary Figs. 3–4). These results confirm that the method is able to robustly and effectively improve the intensity prediction of extreme El Niño mature phase by over 30% in an independent modeling case.

An additional issue in realtime prediction is to identify favorable conditions that indicate a strong El Niño event is likely to occur, which help determine when to implement an O-CNOP-based ensemble prediction strategy. In fact, issuing early warnings for extreme ENSO events is a complex and highly challenging task61,62. In our study, an early-warning criterion is developed based on the standard deviation of hindcast T150 anomalies. The methodology proceeds as follows: First, a series of 12-month control predictions are made using the 3D-Geoformer, initiated in March of each year from 1980 to 2023. Then, the T150 predictions in the eastern equatorial Pacific (5°S-5°N, 140°W-80°W) are extracted for the October-November-December (OND) season. The standard deviation of the regionally averaged OND T150 anomalies across the entire hindcast period is calculated and used as the threshold criterion. For realtime applications, we compare the springtime-initialized predictions against this threshold. If the predicted OND T150 values exceed the threshold, the year is classified as likely to have a strong El Niño event. In such cases, O-CNOP-based ensemble predictions are subsequently implemented. Validation results demonstrate that this criterion method successfully identifies the strong El Niño events that occur in 1982/83, 1997/98, 2015/16 and 2023/24, but a few false alarms are also difficult to avoid (Supplementary Fig. 5). The applicability of this approach for future realtime prediction requires further assessment through continued operational implementation.

Discussion

Large-scale ensemble predictions typically require enormous computational resources using traditional numerical models. Compared to physics-based traditional numerical models, DL models offer significant advantages in computational efficiency and predictive accuracy. Consequently, many studies propose constructing data-driven climate model simulators to perform large ensemble simulations63,64, which are able to reduce prediction uncertainty and provide much more reliable predictions of extreme event probabilities. However, recent research indicates that DL models currently used cannot inadequately represent the chaotic dynamics inherent to the climate system39,65,66. A key consequence of this limitation is that small initial perturbations, such as those related to the butterfly effect, fail to amplify realistically during model integration. Consequently, stochastic perturbations applied to initial conditions are unable to generate sufficiently diverse and meaningful ensemble members in DL-based predictions.

The insensitivity of DL models to stochastic perturbations stems primarily from two factors related to data and training strategy. First, the performance of data-driven models strongly depends on training data quality. When training datasets contain insufficient samples of extreme events, models fail to accurately learn their characteristics. Second, most DL models are trained using mini-batch gradient descent, which optimizes model parameters based on averaged gradients from each batch, thereby smoothing extreme events. While this property with DL model enhances its robustness, it also degrades the ability to predict extreme events. These limitations severely hinder the operational application of current DL models in weather and climate research in terms of ensemble prediction.

In this study, we evaluate and then enhance the capability of the DL-based 3D-Geoformer in predicting extreme ENSO events. The results from conventional use of the 3D-Geoformer indicate that the model underestimates the intensity of extreme El Niño events when predictions are initiated from boreal spring, with Niño3.4 prediction error reaching up to 2°C. We initially attempt to improve predictions by adding stochastic perturbations to temperature predictors to generate ensembles, but the results show no significant improvement. To improve El Niño predictions, we introduce an O-CNOP method to generate IC perturbations, enabling the generation of sufficiently diverse and effective ensemble members without retraining multiple DL models; these O-CNOP-based perturbations represent those that impose maximum nonlinear impact on prediction uncertainty at the target prediction time. Then, the O-CNOP-based perturbations are superimposed onto the temperature predictors to conduct ensemble predictions. Here, we provide the detailed descriptions of the computational procedures and application processes of this method, which offers three key advantages: (1) From the perspective of computing method, the O-CNOP computation employs a large-sample optimization approach that does not require model gradient information. Therefore, the computational process does not need to be redesigned for different models, demonstrating its excellent universality and transferability. Furthermore, since forward inference in DL models is significantly faster than gradient-based backward optimization processes, this method remains efficient and feasible despite a need for requiring large-sample optimization. (2) From the perspective of model interpretability, since all initial perturbation candidate samples are derived from simulated or observed fields, they possess well-defined spatial modes. This ensures that the computed O-CNOPs exhibit coherent spatial structures, facilitating our understanding of which systematic errors or initial uncertainties lead to ultimate prediction errors. (3) Regarding the practicality of the method, the O-CNOP-based IC perturbations obtained for a particular problem (e.g., extreme El Niño predictions in this application presented in this paper) often exhibit similar spatial patterns, indicating these ENSO-related IC perturbations are not dependent on individual events. These characteristics significantly enhances the practical application value of this method.

Testing on predictions for four strong El Niño events since the 1980s demonstrates that the O-CNOP-based ensemble predictions can significantly improve the predictive capability for extreme El Niño events using the 3D-Geoformer. Compared with deterministic predictions without initial perturbations, ensemble predictions can reduce springtime-initialized Niño3.4 prediction errors by more than 30%. It also systematically improves predictions of the full three-dimensional ocean temperature fields, with notably larger effects on subsurface temperature anomalies than on surface anomalies. This improvement in subsurface prediction is crucial for the long-term ENSO prediction capability in DL models.

We also note that three of the four events analyzed (1982/83, 1997/98, 2023/24) featured strong Eastern Pacific warming, whereas the independent test event (2015/16) developed as a Central Pacific event with different SST anomaly patterns67. Whether CNOP structures vary systematically across different ENSO flavors warrants further investigation. This issue could be addressed by applying CNOP methods to coupled climate models that can adequately represent both types of ENSO. Moreover, in this study, perturbations are applied only to temperature field, which may be a limitation given the stochastic nature of wind field and its crucial role as an oceanic forcing. Future work should therefore extend the CNOP methodology to incorporate synergistic perturbations in both wind and ocean temperature fields to more fully represent the physical processes of the ocean-atmosphere coupled system.

Beyond the DL model ensemble prediction method proposed in this paper, recent studies explore alternative strategies by incorporating models trained through unsupervised diffusion models68,69 or creating a set of different models by randomizing the seed in the training process24,70 to increase prediction spread and avoid deterministic predictions. However, for these pre-trained weather and climate DL models, our method provides an effective ensemble solution without requiring architectural modifications or retraining. This highlights its practicality as a general framework that can be readily applied to existing DL prediction systems.

Methods

Datasets

Multivariate anomaly fields serve as the input predictors and output predictands of the 3D-Geoformer, comprising a total of nine variables within the spatial domain spanning 20°S–20°N and 92°E–330°E. These variables include zonal and meridional components of surface wind stress anomalies, along with ocean temperature anomalies distributed across seven layers in the upper ocean (at depths of 5, 20, 40, 60, 90, 120, and 150 m). The reanalysis data used in this study are selected from the Global Ocean Data Assimilation System71 (GODAS). All multivariate anomalies are interpolated onto regular grids with a resolution of 2° in zonal direction and 0.5° (1°) in meridional direction within (out of) 5°S–5°N.

Computations of O-CNOP-based IC perturbations

To overcome the high computational cost of gradient-based CNOP computations that require adjoint models, a large-sample ensemble optimization method is proposed to compute CNOP without gradient information while achieving comparable results. The detailed calculation process is described below and in Fig. 3.

Candidate sample generation and energy constraint

Firstly, we randomly select 2400 monthly temperature anomaly fields (xi, i = 1, 2, …, 2400) from CMIP6 historical simulations and SODA reanalyses as initial candidate samples. Each sample contains seven-layer ocean temperature anomalies in the tropical Pacific region (20°S-20°N, 120°E-80°W). To ensure consistent perturbation magnitude while preserving distinct spatial structure, all candidate samples are normalized under a unified energy constraint:\({x^{\prime}}_{i}^{(1)}={x}_{i}\times (E/{E}_{i})\). Here, the superscript “(1)” in \({x^{\prime} }_{i}{(1)}\) is denoted as being used to calculate CNOP1. The E represents the prescribed reference energy and Ei denotes the energy of the i-th candidate sample, which is computed as the sum of squared temperature anomalies. The reference energy E is determined assuming an averaged temperature perturbation magnitude of 0.5 °C per grid point, yielding a total perturbation energy of E = 51 × 80 × 7 × 0.52 ≈ 7000 °C2 in the tropical Pacific region (spanning 80 zonal and 51 meridional grid points, and 7 layers).

Moreover, sensitivity analysis using the 3D-Geoformer reveals that among the twelve consecutive monthly input predictors, initial anomaly at the last month (i.e., the month closest to the first-month prediction) exerts the greatest influence on ENSO prediction skill (Supplementary Fig. 6). Consequently, perturbations in subsequent analyses are applied only to the last month’s temperature predictors.

Perturbed predictions and selection

The control experiment (ECTL) and perturbed predictions can be performed as Y = F(X) and \(Y+{Y^{\prime} }_{i}\)=F(X + \({x^{\prime} }_{i}{(1)}\)), respectively; here, F(∙) denotes the 3D-Geoformer, X is the input predictors, Y is the control predictions (contains multivariate), and \({{Y}^{{\prime} }}_{i}\) represents the difference between perturbed and control prediction outputs. The effect of each perturbation sample is quantified using the root mean squared error (RMSE) of Niño3.4 SST anomalies between control and perturbed predictions.

Our objective is to find the initial perturbation \({x}^{{\prime} }\) that maximizes the objective function \(\mathop{\max }\nolimits_{{E}_{{x}^{{\prime} }}=E}J({x}^{{\prime} })=\frac{1}{T}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{t={t}_{0}}^{{t}_{0}+T}{[{N}^{{\prime} }(t)-N(t)]}^{2}\), subject to a given perturbation energy constraint \({E}_{x^{\prime} }=E\). Here, t0 is the initialization time, and T is the total prediction length. Since the predictions are initialized in March, corresponding to a lead time of 9–10 months representing the ENSO mature phase in boreal winter, T is set to 12 months to ensure that the entire ENSO mature period is covered. \(N{\prime} (t)\) and \(N(t)\) are the Niño3.4 indices calculated from the perturbed and control predictions, respectively. The objective function value \(J({x{\prime} }_{i})\) is evaluated for each candidate perturbation individually, from which the top 20 perturbations with the largest objective function values are selected as the optimal candidates for further refinement.

Iterative optimization processes

An iterative refinement procedure is employed to optimize the selected 20 perturbations over 30 cycles (step 3 in Fig. 3). At each iteration, the arithmetic mean of the current 20 perturbations is computed and its prediction RMSE is evaluated. This mean perturbation is then included as the 21st candidate. Among these 21 perturbations, the one yielding the smallest RMSE (i.e., the weakest growth) is removed, and the process repeats with the remaining 20 perturbations. This iterative selection process ensures progressive convergence toward perturbations that maximize prediction error growth. After 30 iterations, the 20 perturbation fields gradually converge to a consistent pattern. Then, the arithmetic mean of the final 20 perturbations is designated as the first O-CNOP.

Orthogonal CNOP computations

Prior to the computation of subsequent O-CNOPs, the original sample set is orthogonalized against previously computed O-CNOPs using Gram-Schmidt projection:

where \(< \cdot >\) represents inner product operation; \({\Vert \cdot \Vert }^{2}\) is the L2 norm; \({x^{\prime} }_{i}{(n)}\) represents the energy-constrained perturbation samples used for computing the n-th O-CNOP; CNOPk indicates the calculated k-th O-CNOP. The iterative optimization process is then performed on these perturbation samples by repeating the above steps to obtain additional O-CNOPs. We compute the first five O-CNOPs for three strong El Niño events in 1982/83, 1997/98, and 2023/24, resulting in a total of 15 O-CNOP-based IC perturbations. Subsequently, we add these IC perturbations to the temperature predictors in the ECTL to generate 15 ensemble prediction members, and investigate their effects on ENSO ensemble prediction skills in this study.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available online. CMIP6 products are available at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search. The GODAS reanalyses are available at https://iridl.ldeo.columbia.edu/SOURCES/.NOAA/.NCEP/.EMC/.CMB/.GODAS/.monthly/. The SODA reanalyses are available at https://soda.umd.edu/.

Code availability

The code, processed data, and model outputs can be found in https://zenodo.org/records/16986660 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16986660).

References

Cai, W. et al. Pantropical climate interactions. Science 363, eaav4236 (2019).

Liu, Y., Cai, W., Lin, X., Li, Z. & Zhang, Y. Nonlinear El Niño impacts on the global economy under climate change. Nat. Commun. 14, 5887 (2023).

Zhang, R.-H., Rothstein, L. M. & Busalacchi, A. J. Origin of upper-ocean warming and El Niño change on decadal scales in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Nature 391, 879–883 (1998).

Timmermann, A. et al. El Niño-Southern Oscillation complexity. Nature 559, 535–545 (2018).

Thirumalai, K. et al. Future increase in extreme El Niño supported by past glacial changes. Nature 634, 374–380 (2024).

Rivera Tello, G. A., Takahashi, K. & Karamperidou, C. Explained predictions of strong eastern Pacific El Niño events using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 13, 21150 (2023).

Cane, M. A. & Zebiak, S. E. A theory for El Niño and the southern oscillation. Science 228, 1085–1087 (1985).

Cane, M. A., Zebiak, S. E. & Dolan, S. C. Experimental forecasts of El Niño. Nature 321, 827–832 (1986).

Chen, D., Zebiak, S. E., Busalacchi, A. J. & Cane, M. A. An Improved Procedure for EI Niño Forecasting: Implications for Predictability. Science 269, 1699–1702 (1995).

Zhang, R.-H., Zebiak, S. E., Kleeman, R. & Keenlyside, N. A new intermediate coupled model for El Niño simulation and prediction. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, GL018010 (2003).

Barnston, A. G., Tippett, M. K., L’Heureux, M. L., Li, S. & DeWitt, D. G. Skill of Real-Time Seasonal ENSO Model Predictions during 2002-11: Is Our Capability Increasing?. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 631–651 (2012).

Zhu, J., Wang, W., Kumar, A., Liu, Y. & DeWitt, D. Assessment of a New Global Ocean Reanalysis in ENSO Predictions With NOAA UFS. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL106640 (2024).

Ehsan, M. A., L’Heureux, M. L., Tippett, M. K., Robertson, A. W. & Turmelle, J. Real-time ENSO forecast skill evaluated over the last two decades, with focus on the onset of ENSO events. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 301 (2024).

Ji, C., Mu, M., Fang, X. & Tao, L. Improving the Forecasting of El Niño Amplitude Based on an Ensemble Forecast Strategy for Westerly Wind Bursts. J. Clim. 36, 8675–8694 (2023).

Ji, C. et al. Toward skillful forecasting of super El Niño events using a diffusion-based westerly wind burst parameterization. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 273 (2025).

Timmermann, A., Jin, F.-F. & Abshagen, J. A Nonlinear Theory for El Niño Bursting. J. Atmos. Sci. 60, 152–165 (2003).

Geng, L. & Jin, F.-F. Insights into ENSO Diversity from an Intermediate Coupled Model. Part II: Role of Nonlinear Dynamics and Stochastic Forcing. J. Clim. 36, 7527–7547 (2023).

Fang, X., Dijkstra, H., Wieners, C. & Guardamagna, F. A nonlinear full-field conceptual model for ENSO diversity. J. Clim. 37, 3759–3774 (2024).

Tippett, M. K., L’Heureux, M. L., Becker, E. J. & Kumar, A. Excessive Momentum and False Alarms in Late-Spring ENSO Forecasts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087008 (2020).

Jin, Y. S., Liu, Z. Y. & Duan, W. S. The Different Relationships between the ENSO Spring Persistence Barrier and Predictability Barrier. J. Clim. 35, 6207–6218 (2022).

Zhang, R.-H., Gao, C. & Feng, L. Recent ENSO evolution and its real-time prediction challenges. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, nwac052 (2022).

Ham, Y. G., Kim, J. H. & Luo, J. J. Deep learning for multi-year ENSO forecasts. Nature 573, 568–572 (2019).

Zhang, R.-H., Zhou, L., Gao, C. & Tao, L. A transformer-based coupled ocean-atmosphere model for ENSO studies. Sci. Bull. 69, 2323–2327 (2024).

Zhou, L. & Zhang, R.-H. A self-attention-based neural network for three-dimensional multivariate modeling and its skillful ENSO predictions. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf2827 (2023).

Qin, B. et al. The first kind of predictability problem of El Niño predictions in a multivariate coupled data-driven model. Quart. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 150, 5452–5471 (2024).

Mu, B., Cui, Y., Yuan, S. & Qin, B. Incorporating heat budget dynamics in a Transformer-based deep learning model for skillful ENSO prediction. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 208 (2024).

Sun, M., Chen, L., Li, T. & Luo, J.-J. CNN-based ENSO forecasts with a focus on SSTA zonal pattern and physical interpretation. Geophys Res Lett. 50, e2023GL105175 (2023).

Camps-Valls, G. et al. Artificial intelligence for modeling and understanding extreme weather and climate events. Nat. Commun. 16, 1919 (2025).

Li, Y., Zhang, Y. & Zheng, H. Evaluation of the Pangu model in forecasting rapid intensification of tropical cyclones. Atmos. Oceanic Sci. Lett. 100721 (2025).

Duan, S., Zhang, J., Bonfils, C. & Pallotta, G. Testing NeuralGCM’s capability to simulate future heatwaves based on the 2021 Pacific Northwest heatwave event. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 251 (2025).

Demaeyer, J., Penny, S. G. & Vannitsem, S. Identifying Efficient Ensemble Perturbations for Initializing Subseasonal-To-Seasonal Prediction. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 14, e2021MS002828 (2022).

Feng, J., Toth, Z., Zhang, J. & Peña, M. Ensemble forecasting: A foray of dynamics into the realm of statistics. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 150, 2537–2560 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. An ensemble-based coupled reanalysis of the climate from 1860 to the present (CoRea1860+). Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 1−38 (2025).

Fang, X. & Chen, N. Quantifying the Predictability of ENSO Complexity Using a Statistically Accurate Multiscale Stochastic Model and Information Theory. J. Clim. 36, 2681–2702 (2023).

Yeager, S. G. et al. The Seasonal-to-Multiyear Large Ensemble (SMYLE) prediction system using the Community Earth System Model version 2. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 6451–6493 (2022).

Schevenhoven, F. et al. Supermodeling: Improving Predictions with an Ensemble of Interacting Models. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 104, E1670–E1686 (2023).

Larson, S. M. & Kirtman, B. P. Linking preconditioning to extreme ENSO events and reduced ensemble spread. Clim. Dyn. 52, 7417–7433 (2017).

Lorenz, E. N. Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 20, 130–141 (1963).

Selz, T. & Craig, G. C. Can Artificial Intelligence-Based Weather Prediction Models Simulate the Butterfly Effect? Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105747 (2023).

Duan, W. & Huo, Z. An Approach to Generating Mutually Independent Initial Perturbations for Ensemble Forecasts: Orthogonal Conditional Nonlinear Optimal Perturbations. J. Atmos. Sci. 73, 997–1014 (2016).

Mu, M. & Duan, W. A new approach to studying ENSO predictability: Conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation. Chin. Sci. Bull. 48, 1045–1047 (2003).

Huo, Z. & Duan, W. The application of the orthogonal conditional nonlinear optimal perturbations method to typhoon track ensemble forecasts. Sci. China.: Earth Sci. 62, 376–388 (2019).

Huo, Z., Duan, W. & Zhou, F. Ensemble forecasts of tropical cyclone track with orthogonal conditional nonlinear optimal perturbations. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 36, 231–247 (2019).

Duan, W., Ma, J. & Vannitsem, S. An Ensemble Forecasting Method for Dealing with the Combined Effects of the Initial and Model Errors and a Potential Deep Learning Implementation. Mon. Weather Rev. 150, 2959–2976 (2022).

Zhang, H., Duan, W. & Zhang, Y. Using the orthogonal conditional nonlinear optimal perturbations approach to address the uncertainties of tropical cyclone track forecasts generated by the WRF model. Weather Forecast. 38, 1907–1933 (2023).

Zhou, L. & Zhang, R.-H. The 3D-Geoformer for ENSO studies: a Transformer-based model with integrated gradient methods for enhanced explainability. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 43, 1688–1708 (2025).

Gao, C., Zhou, L. & Zhang, R.-H. A Transformer-Based Deep Learning Model for Successful Predictions of the 2021 Second-Year La Niña Condition. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104034 (2023).

Zhang, R.-H., Zhou, L., Gao, C. & Tao, L. Real-time predictions of the 2023-2024 climate conditions in the tropical Pacific using a purely data-driven Transformer model. Sci. China: Earth Sci. 67, 3709–3726 (2024).

Zhou, L. & Zhang, R.-H. ENSO-Related Precursor Pathways of Interannual Thermal Anomalies Identified Using a Transformer-Based Deep Learning Model in the Tropical Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL107347 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Combined dynamical-deep learning ENSO forecasts. Nat. Commun. 16, 3845 (2025).

Meng, Z. & Hakim, G. J. Reconstructing the tropical Pacific upper ocean using online data assimilation with a deep learning model. J. Adv. Modeling Earth Syst. 16, e2024MS004422 (2024).

Toth, Z. & Kalnay, E. Ensemble forecasting at NMC: The generation of perturbations. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 74, 2317–2330 (1993).

Duan, W., Yang, L., Xu, Z. & Chen, J. Conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation: Applications to ensemble forecasting of high-impact weather systems. In: Numerical Weather Prediction: East Asian Perspectives. Springer (2023).

Mu, M. & Jiang, Z. A new approach to the generation of initial perturbations for ensemble prediction: Conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation. Chin. Sci. Bull. 53, 2062–2068 (2008).

Pu, J., Mu, M., Feng, J., Zhong, X. & Li, H. A fast physics-based perturbation generator of machine learning weather model for efficient ensemble forecasts of tropical cyclone track. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 128 (2025).

Duan, W. & Hu, J. The initial errors that induce a significant “spring predictability barrier” for El Niño events and their implications for target observation: results from an earth system model. Clim. Dyn. 46, 3599–3615 (2015).

Duan, W. & Mu, M. Predictability of El Niño-southern oscillation events. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science) (2018).

Tao, L. et al. Impacts of Initial Zonal Current Errors on the Predictions of Two Types of El Niño Events. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 128, e2023JC019833 (2023).

Mlakar, P., Merse, J. & Faganeli Pucer, J. Ensemble weather forecast post-processing with a flexible probabilistic neural network approach. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 150, 4156–4177 (2024).

Tziperman, E., Stone, L., Cane, M. A. & Jarosh, H. El Niño chaos: Overlapping of resonances between the seasonal cycle and the Pacific ocean-atmosphere oscillator. Science 264, 72–74 (1994).

Ludescher, J. et al. Improved El Niño forecasting by cooperativity detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 11742–11745 (2013).

Ludescher, J. et al. Very early warning of next El Niño. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 2064–2066 (2014).

Eyring, V. et al. Pushing the frontiers in climate modelling and analysis with machine learning. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 916–928 (2024).

Anderson, G. J. & Lucas, D. D. Machine Learning Predictions of a Multiresolution Climate Model Ensemble. Geophys Res Lett. 45, 4273–4280 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Fischer, E., Zscheischler, J. & Engelke, S. Numerical models outperform AI weather forecasts of record-breaking extremes. arXiv:250815724 (2025).

Charlton-Perez, A. J. et al. Do AI models produce better weather forecasts than physics-based models? A quantitative evaluation case study of Storm Ciarán. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, (2024).

Takahashi, K., Montecinos, A., Goubanova, K. & Dewitte, B. ENSO regimes: Reinterpreting the canonical and Modoki El Niño. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L10704 (2011).

Pan, B. et al. Improving Seasonal Forecast Using Probabilistic Deep Learning. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 14, e2021MS002766 (2022).

Li, L., Carver, R., Lopez-Gomez, I., Sha, F. & Anderson, J. Generative emulation of weather forecast ensembles with diffusion models. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk4489 (2024).

Weyn, J. A., Durran, D. R., Caruana, R. & Cresswell-Clay, N. Sub-Seasonal Forecasting With a Large Ensemble of Deep-Learning Weather Prediction Models. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 13, e2021MS002502 (2021).

Behringer, D. & Xue, Y. Evaluation of the global ocean data assimilation system at NCEP: The Pacific Ocean. In: Eighth Symp. on Integrated Observing and Assimilation Systems for Atmosphere, Oceans, and Land Surface) (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42030410), Laoshan Laboratory (No. LSKJ202202402), National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2024YFC2815702) and Jiangsu Innovation Research Group (No. JSSCTD 202346). Zhou is additionally supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42506019), Basic Research Program of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20250752), China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (No. BX20240169) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2141062400101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., Z.R.-H. and T.J.L. designed the research. Z.L. performed the analysis and plotted figures. Z.L. and Z.R.-H. drafted the manuscript. All the authors contributed to physical interpretation and manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Zhang, RH. & Tao, L. AI-Enabled conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation enhances ensemble prediction of extreme El Niño events. npj Clim Atmos Sci 9, 30 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01303-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01303-6