Abstract

Microalgae emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that can profoundly impact climate by leading to new particle formation and influencing clouds. Among these VOCs, dimethyl-sulphide (DMS) is of particular interest due to its key role in atmospheric processes. Despite its importance, many detailed processes linking microalgae and sea-atmosphere interactions remain poorly understood. We investigated the response of a freshwater and saltwater microalgal species of haptophytes known to produce DMS, to air entrainment and bubble-bursting mechanisms relevant for wave-breaking over the ocean. We show that bubbling resulted in the successful aerosolisation of microalgae and concurrent emission of DMS. In contrast, only background levels of DMS were detected when bubbling ceased, suggesting a critical role of bubbles in the sea-air exchange of DMS under the studied conditions. DMS mixing ratios were not correlated with the emitted particle concentrations and decreased over time, while particle concentrations remained stable. Bubbling also significantly reduced the viability of aquatic microalgae. Approximately half of the aerosolised microalgae were viable upon emission, but were not able to grow during subsequent cultivation recovery. Thus, the potential for microalgae to disperse to new environments via aerosolization is low, while their climate impact through the release of DMS remains substantial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atmospheric aerosols have major implications for Earth’s radiative balance by interacting with solar radiation and influencing cloud formation1,2. Primary biological aerosol particles (PBAPs), defined as directly emitted airborne particles of biological nature3, include airborne microalgae, unicellular microorganisms and one of the least studied organisms in aerobiology4. Marine PBAPs also produce several organic compounds like polysaccharides that are commonly found in primary marine organic aerosol (PMOA; e.g.5,6). The aerosolisation potential of aquatic microalgae has been described to occur primarily during wave breaking mediated bubble bursting at the water surface, transferring compounds present in bulk water into the atmosphere7,8. The importance of airborne microalgae and related organic compounds for climate is still largely unknown.

PBAPs are typically large in size and are therefore expected to have short periods of residence in the atmosphere, with a negligible to non-existent impact on climate3. Remarkably, airborne microalgae have been reported in remote locations such as Antarctica and thus far away from potential sources7,9,10. This implies that on certain occasions PBAPs can have transit in the atmosphere longer than previously expected, caused by special meteorological conditions like when wind velocities are fast relative to the particles’ settling velocities and turbulence prevails11,12. It is also well known that PBAPs, including microalgae, can actively nucleate ice13,14,15 and they have been suggested to act as giant cloud condensation nuclei (CCN)3. Thus, airborne microalgae could have a more important role in climate by interacting with radiation and clouds.

Emissions of chemical compounds from aquatic microalgae have been extensively studied [e.g.15,16,17,18]. These include volatile organic compounds (VOCs), a major one being dimethyl-sulphide (DMS)19. DMS constitutes the largest source of naturally emitted sulphur to the atmosphere and due to the reduction in sulphur-based fossil fuels, natural sulphur emissions now play a key role for global sulphate aerosols20,21,22,23.

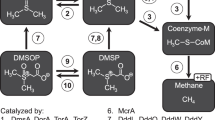

The main precursor of DMS is dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), produced mainly by aquatic microalgae in the oceans24 in different amounts25. Several studies highlight that only a small fraction of ~10% of the DMS produced in ocean water is emitted into the atmosphere26. The majority of dissolved DMS is decomposed by microbes27,28 or photolysis29,30. The close interconnection between DMS production and its loss makes it difficult to investigate the factors influencing and the dynamics governing DMS emissions from the ocean surface. These can for example depend on surface winds, sea surface temperature or downwelling irradiance31,32,33.

The sea-air exchange of DMS can occur by either direct diffusion across the main interface or by bubble-mediated transport. Earth system models [e.g.34,35,36] typically describe the DMS flux based on gas transfer parametrizations relating the sea-air flux of DMS to the concentration difference between surface ocean and atmosphere and the gas-specific transfer velocity, including the gas solubility, diffusivity and wind speed. Although such parametrizations have been very useful to evaluate global scale ocean fluxes, they omit bubbles from wave breaking and the bubble-mediated contribution to the DMS flux. In the absence of waves and bubbles, the wind-induced turbulent gas diffusivity is the dominant exchange pathway, while during wave-breaking bubble processes might become important. Gases may be encapsulated in a bubble and released by diffusion across the surface of the bubble or when the bubble bursts. At high wind speeds, accompanied by breaking waves, enhanced transfer of gases is to be expected but only limited data exists describing this process37. Bubble-mediated gas transfer is also dependent on the solubility of the gas and expected to play a more important role at high wind speeds38,39. As DMS is considered a moderately soluble gas, it is currently treated as not being greatly influenced by bubble-mediated transfer39,40,41, which is why model parametrizations currently do not include a bubble-mediated transfer velocity term.

Atmospheric DMS mixing ratios in marine [e.g.42,43,44] and freshwater (FW) environments45,46,47 range from a few ppt to ~12 ppb36,43,46,48,49,50,51. Once in the atmosphere, DMS can be oxidised for example by hydroxyl radicals to form aerosol particles consisting mainly of methane sulphonic acid (MSA) and sulphuric acid, ultimately leading to the formation of sulphate aerosols52,53,54. The complex chemical reaction pathways have been studied in several modelling setups [e.g.55,56,57,58] as well as laboratory based atmospheric simulation chamber experiments [e.g.59,60,61]. Secondary aerosols formed via the oxidation of DMS are known to be excellent CCN62,63,64,65 and their importance for aerosol-cloud interactions has also been explored in numerous modelling studies [e.g.56,66,67]. Despite the major importance of DMS and sulphate aerosols for climate is recognised, their detailed role in atmospheric chemistry and the mechanisms involved in the release of DMS remain unclear.

This study investigates the aerosolization potential and concurrent release of DMS from two microalgal species of haptophytes from FW and saltwater (SW) habitats in controlled laboratory experiments. The chosen marine species, CCMP284, was previously identified as a common representative of phytoplankton and a major producer of DMSP25. Additionally, we selected the FW Chrysochromulina (CCMP291) from the same culture collection, to explore a potential climatic role of this species from FW bodies such as lakes. The impact of different bubble bursting scenarios on the microalgae in bulk samples and their aerosolisation potential, the amount and fraction of microalgae to the total aerosolised particles and of released DMSP and DMS were studied. Furthermore, the viability of aerosolised microalgae was explored.

Results

Bulk phase: impact of bubbling on aquatic microalgae

The total number of microalgae in the water tank (abundance in bulk) ranged from ~5 to 630 million cells per 10 litres of water (Table 1), as expected in a natural bloom in both FW and SW environments (e.g.68,69, >million cells per litre).

The abundance of aquatic microalgal cells during Homogenisation, SJ and MJ treatments, was similar across treatments (Kruskal-Wallis \({{\rm{X}}}_{\,(2)}^{2}\) = 2.6719, p = 0.2629; Table S1), most probably due to a buffering effect. However, each microalgal strain (FW, SW) was impacted differently (Kruskal-Wallis \({{\rm{X}}}_{\,(1)}^{2}\) = 5.4541, p = 0.01952) with variations across experiments (Kruskal-Wallis \({{\rm{X}}}_{\,(7)}^{2}\) = 55.442, p = 1.219e-09) (see Table S2). In the further analysis, we removed experiments FW1, FW2, SW1 and SW2 for which experimental conditions were slightly different (e.g. longer treatment, unfavourable conditions for cells such as exposure to higher temperature leading to their disruption), and focused on the comparison between similar experiments, i.e. FW3, SW3, SW4 and SW5.

In experiments FW3, SW3, SW4 and SW5, the microalgal strains responded differently to treatment (Homogenisation, SJ, MJ) in the water tank (Two-way ANOVA strain:treatment F(1,24) = 75.148, p = 4.65e-11; Table S3), showing similar abundances after SJ and MJ treatments (Tukey HSD, p > 0.05) but different abundances after the initial Homogenisation (p < 0.05) (Table S4). It appears that the FW strain was more negatively impacted by Homogenisation than its counterpart (Fig. 1). As anticipated given the different initial load of cells, discrepancies in aquatic cell abundances were observed among experiments (Two-way ANOVA strain:treatment F(2,24) = 32.835, p = 1.35e-07, Table S2). Notably, FW3, with the highest initial cell load and SW4, with a much lower initial load, exhibited similar abundances across the experiment treatments (Tukey HSD, p = 0.517), reinforcing the observation that the FW strain could be more sensitive to treatment.

Aquatic (Starter, Homogenisation, SJ, MJ) and aerosolized fraction (Impinger SJ and Impinger MJ) (n = 3 replicates per treatment) in a both investigated strains, b in the freshwater stain (FW) and c saltwater strain (SW), over all experiments. Boxplot: median, interquartile range, and standard deviation.

Interestingly, the percentage of intact aquatic cells (Neutral Red data) in FW3, SW3, SW4 and SW5, remained similar across treatments (Kruskal-Wallis \({{\rm{X}}}_{\,(2)}^{2}\) = 0.058559, p = 0.9711) with 74.5 ± 30.3% of intact cells under SJ and 78.7 ± 21.4% under MJ treatment (Table S5). In agreement with the observed fluctuations in cell abundance (Table S3, Lugol staining), the integrity of each strain (Neutral Red staining) was affected differently in the water tank under treatment (Homogenisation, SJ and MJ; Kruskal-Wallis \({{\rm{X}}}_{\,(1)}^{2}\) = 19.703, p = 9.047e-06), with a lower percentage of intact aquatic cells in the FW (34.7 ± 18.4%) compared to the SW strain (90.4 ± 6.66%; Table S6). It is noteworthy that the fluctuation between experiments for the SW strain (83.0–97.3% intact cells (SW4 < SW5 < SW3), Table S7, Kruskal-Wallis \({{\rm{X}}}_{\,(2)}^{2}\) = 14.363, p = 0.0007607), is seemingly unrelated to the initial load SW5 < SW4 < SW3 (Table 1) and possibly linked to intrinsic biological features.

Using flow cytometry (FCM), we further investigated the impact of bubbling on FW and SW strains. The number of cells detected in FW3 was low (481–1014 counts) but above the background level (12.5 ± 1.0 counts). The FW strain was characterised by a well-defined population of cells with similar characteristics as the initial culture (starter sample). Bubbling strongly affected the FW strain with the death of 87.8% of microalgal cells after Homogenisation. We suspect that bubbling induced cell disruption in the FW strain due to the decrease in the percentage of cells containing chlorophyll pigments (e.g. from 98.6 ± 0.2% cells in the initial culture to 44.3 ± 4.8% cells in the water tank after Homogenisation), the increase of damaged/dead cells (e.g. 7.9 ± 7.4% to 95.3 ± 2.6%), and the increase in debris. The percentage of damaged cells in the water tank in the successive SJ and MJ treatments was rather constant (93.0 ± 2.5%). The SW strain (experiments SW3, SW4, SW5) was characterised by a well-defined population of cells throughout the bubbling treatments. Initial bubbling (Homogenisation) led to the loss of only 24.3 ± 7.5% viable cells. During treatments (Homogenisation, SJ, MJ) the percentage of cells containing chlorophyll pigments remained elevated and rather constant (82.6 ± 2.6%), with few detected damaged organisms (2.9 ± 1.2%).

Bulk phase: dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP)

DMSP concentrations were analysed according to Bektassov et al.70 in experiments SW1 and FW1. Results are presented in Fig. S1 in the supplementary. A clear increase in DMSP was observed after Homogenisation (~4-fold in FW1) with comparable values for the SW and FW experiment. Subsequent treatments with SJ and MJ did not strongly affect DMSP concentrations, yielding similar DMSP concentrations compared to after Homogenisation. FW samples show more variability with highest values after MJ treatment.

Aerosol phase: aerosolised fraction

Aerosolised particles were measured in all experiments as illustrated in Fig. 2. The aerosol number concentrations appeared to be relatively constant throughout the course of the experiments ranging between 10 and 200 particles per cm3 in FW experiments and between 10 and 2300 particles per cm3 in SW experiments. In FW experiments, the aerosol number concentrations reflect the emissions of the ‘microalgae ensemble’ consisting in the microalgal cells and their bionts (Fig. S2), and potential fragments of both. Higher emissions were measured during bubbling with MJ compared to SJ. In SW experiments, the aerosols emitted contained the ‘microalgae ensemble’ as well as salt particles. The emissions during SJ were higher compared to those during MJ, showing an opposite trend than in FW experiments. Furthermore, in SW experiments, the overall concentration of aerosols exceeded those of the FW experiments on average by a factor of 100.

To verify whether microalgae were among the emitted particles measured with OPSS, we captured emissions using an impinger for ~1 h and examined the abundance and viability of the captured cells using microscopy and FCM. Microalgal cells from FW and SW strains were collected in both the SJ and MJ treatments, indicating that the two microalgae were successfully aerosolised from the water tank. Additionally, the loss of aquatic microalgal cells was estimated from Lugol abundances in the water tank (Fig. S3) and was marginally significant (two-way ANOVA F(1,10) = 4.007, p = 0.0732), suggesting that microalgae could be aerosolised under the SJ and MJ conditions but only in a small amount.

Impinger results analysed by microscopy found a low but none-the-less positive emission of microalgae (Table S8) and indicated that SJ and MJ treatments did not have a significant impact on the abundance of aerosolized microalgal cells in all (Kruskal-Wallis \({{\rm{X}}}_{\,(1)}^{2}\) = 0.27862, p = 0.5976) and selected experiments (Kruskal-Wallis \({{\rm{X}}}_{\,(1)}^{2}\) = 0.0081024, p = 0.9283, Table S8).

FCM found a higher emission of FW cells under MJ (172.7 ± 26.8 counts) than SJ (34.0 ± 7.0 counts). The SW strain also showed a systematically higher emission under MJ (181.8 ± 22.0 counts, i.e., recaptured abundance: 8.3 (±1.4) × 103 cells) compared to SJ (44.6 ± 13.8 counts, i.e., recaptured abundance: 5.3 (±1.4) × 103 cells).

Also, DMSP was found in the impinger samples in experiments SW1 and FW1 (see Fig. S1).

Aerosol phase: size distributions of aerosolised particles

The length, width and volume of the organisms (biovolume) were estimated by microscopy, revealing similar dimensions for both strains with a length of ~7 μm and a width between 5 and 6 μm (see Table S5).

Number size distributions for Exp.s FW3 and SW5 are illustrated in Fig. 3. Size distributions of all other experiments are presented in supplementary Figs. S4–S10. To better visualise differences in the shape of the distributions, each was normalised by its maximum concentration. In FW experiments, which were dominated by the microalgae ensemble, particles up to ~2 μm were found, with a distinct peak around 1 μm (Fig. 3a from OPSS). No differences could be observed between SJ and MJ treatments. In SW experiments, where the microalgae ensemble and salt particles were aerosolized, both size spectrometers (OPSS and WELAS) found particles from their lower detection limits up to ~4 μm (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, WELAS, with a higher size resolution, revealed a distinct peak around 0.4 μm and a high concentration of sub-0.3 μm particles. Interestingly, OPSS results indicate a peak for μm sized particles from ~1 to 2 μm, which is not visible in WELAS results. Both spectrometers found only marginal differences in size between SJ and MJ treatments, while more clear differences were observed for the concentrations. These can be ascribed to higher concentrations of particles in the lowest bins, while concentrations were comparable above appropriately 0.5 μm (see Fig. S10).

To further elucidate the differences observed in the size distributions presented in Fig. 3a and b, additional experiments were carried out separating effects of pure MilliQ water (‘MilliQ’), pure saltwater (‘Salt’) and a combination of MilliQ water, salt and microalgae (‘Algae’). Total number concentrations and size distributions subdivided for the different stages of a SW experiment are presented in Fig. 4. Concentrations <10 # cm−3 were detected during the ‘MilliQ’ stage (Fig. 4a), while similar concentrations, number and surface size distributions were found for the ‘Salt’ and ‘Algae’ stages. In the size distributions during the ‘Salt’ and ‘Algae’ stages, two distinct peaks were visible, one at around 0.4 μm in the dN/dlogD distribution (Fig. 4b), as already found in Fig. 3b, and one at ~1.6 μm in the dS/dlogD distribution (Fig. 4c). This second peak coincides with the one observed in dN/dlogD recorded with the OPSS in Fig. 3b. No distinct signal by the microalgae ensemble is visible.

a Total number concentration; b normalised mean number size distribution (dN/dlogD) and c normalised mean surface size distribution (dS/dlogD). Results from ‘MilliQ water’ (termed ‘MilliQ’), ‘MilliQ water and salt’ (termed ‘Salt’) and ‘MilliQ water, salt and microalgae’ (termed ‘Algae’) stages are displayed.

Aerosol phase: airborne microalgae viability

The results showed that the SJ and MJ treatments did not have a significant impact on the viability of aerosolised microalgae across strains (two-way ANOVA F(1,15) = 1.967, p = 0.181; Table S9). Figure 5 shows that a similar number of intact (i.e. viable) organisms were retrieved under SJ (57.3 ± 28.4%, n = 12) compared to MJ treatment (44.6 ± 15.6%, n = 12). More specifically, SJ treatment led to 57.1 ± 31.6% and 57.8 ± 22.7% of intact organisms in SW and FW strains, respectively, while MJ treatment slightly reduced the percentage of intact organisms to 45.2 ± 17.4 and 43.0 ± 11.4, in SW and FW strains, respectively. In both SW and FW experiments, approximately half of the microalgal cells emitted and recaptured by the impinger were intact (FW: 50.4 ± 18.0%, n = 6, SW: 50.8 ± 25.0%, n = 18). Similar rates were found comparing the different experiments (two-way ANOVA F(2,15) = 1.234, p = 0.319, Table S10).

FCM showed that the number of cells collected from the impinger in FW experiments was low (26–195 counts) but above the background (12.5 ± 1.0 counts). The number of cells in the impinger during SW experiments was very low (13–325 counts), with a signal close to the background noise (11–60 counts). All FW algae under both treatments were inferred as damaged organisms by FCM (100.0 ± 0.0%). In the SW strain, however, the number of detected microalgae was too low for such estimation.

In addition, the viability of the aerosolised microalgae collected in the impinger was assessed by inoculate cultivation. None of the aerosolised inoculates in either of the two investigated strains were able to grow or show motion during the 2-month incubation period after the experimentation. The growth and movement of the organism was visible only in positive controls.

Aerosol phase: dimethyl-sulphide (DMS)

In experiments FW3 (Fig. 6) and SW5 (Fig. 7) background levels of DMS below <2 ppb were measured by PTR-ToF-MS during ‘MilliQ’ and ‘MilliQ’ and ‘Salt’ stages (including bubbling of salt), respectively. Additionally, during SW5 the DMS signal was monitored after introducing microalgae into the tank but before bubbling (‘MA NB’) showing comparable background levels. Once bubbling was started, DMS mixing ratios as well as total number concentrations promptly increased but immediately decreased when bubbling stopped (initial grey points after treatment in Figs. 6a, b and 7a, b).

In Exp. FW3, DMS mixing ratios reached ~6 ppb both during Homogenisation (Hom.) and the ~ 1 h measurement period using SJ9 (Fig. 6b). DMS mixing ratios during MJ3, reached a maximum of ~ 3 ppb. A decrease of DMS over time was observed during treatments SJ9 and MJ3, while particle number concentrations remained constant. Between treatments sweep air was continuously flushing the head-space and the tank was briefly opened to collect water samples and change the jet. Thus, the constant values recorded between treatments (constant grey points) reflect the baseline in the lab and in the head-space of the tank.

In Exp. SW5 (Fig. 7) salt was first introduced and mixed in the tank (‘Salt SJ9’) producing aerosol particles without concurrent emissions of DMS. Then, the effect of varying the pump velocity from level 1–9 (SJ1–SJ9) was explored. Both, aerosol number concentrations and DMS mixing ratios increased with increasing pump velocity. While particle concentrations quickly reached constant levels, gradual increases in DMS concentrations were observed during SJ1 and SJ3. Between SJ1 and SJ3, the pump was not stopped and no samples were taken from the tank. Highest levels of DMS of ~6 ppb were reached during SJ9 and MJ3. A decrease in the mixing ratios of DMS over time was visible during the longer measurement periods of ~1 h in treatments SJ9 and MJ3, with faster decay rates during MJ treatment. During these treatment steps, particle concentrations, however, remained constant. Results form other FW amd SW experiments are presented in Supplementary Figs. S11 and S12.

Thus, the DMS mixing ratios and their decrease during the longer measurement periods varied with microalgae strain: DMS starting values in SW-SJ9 and SW-MJ3 were comparable, in contrast the FW strain starting values of FW-SJ9 and FW-MJ3 differed by about a factor 2. In FW experiments the fastest decay was observed during SJ9, while it occurred during MJ3 in SW experiments. The initial cell abundance in the tank was substantially higher during FW3 compared to SW5. When comparing DMS emissions and cell abundances before treatment, no significant correlation was found (FW species: positive but not significant, Parametric test - Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.914, t = 2.254, df = 1, p = 0.266; SW species: positive but not significant, Non parametric tests, Kendall (τ = 0.73, T = 13, p = 0.056) and Spearman (ρ = 0.83, S = 6, p = 0.058)).

Using the temporal evolution of DMS mixing ratios measured in the head-space in combination with the flow through the system and the geometry of the tank, DMS fluxes were calculated following the approach presented in refs. 18,71. The exact calculation and results are presented in the Supplementary and in Fig. S13. Due to the restrictions of the laboratory sea spray simulation tank (i.e. using a continuous jet instead of intermittent wave-breaking, having a confined area for bubbles to move, etc.) fluxes derived from our experiments, are necessarily different from the ones obtained from the natural wave breaking in the open ocean. The fluxes in experiments FW3 and SW5 ranged from ~40 to 110 ng/m2/s and were thus generally higher compared to typical fluxes found over the ocean (i.e. typically in the range of 1–60 ng/m2/s, see e.g.71).

To verify the DMS signal, Tenax tube samples were analysed with GC-MS demonstrating the presence of DMS and also DMSO. Mass spectral confirmation are presented in the Supplementary Fig. S14.

Discussion

Our study shows the successful aerosolisation of two haptophyte strains of microalgae originating from FW and SW environments with concurrent measurements of DMSP in the water and DMS in the air during bubble bursting processes.

Both the abundance and viability of aquatic microalgal cells was strongly negatively affected by bubble bursting simulations (treatments), where the abundance and percentage of alive microalgae was particularly drastically reduced in the FW strain. The type of treatment, i.e. SJ vs. MJ, impacting on the water surface, did not have a significant effect on the total abundance and viability of aquatic microalgae. Both, SJ and MJ treatments utilised continuous water impingement to entrain air into the bulk water, which is further dispersed in a plume of bubbles that burst at the water surface. While SJ employs a single, centred water jet creating a concentrated spray pattern, MJ distributes a comparable amount of water more evenly across the tank, applying less pressure at each impaction point. The velocity of the water impacting the surface during the main SJ and MJ settings was chosen to be comparable in this study (MJ3: 8.7 L/min vs. SJ9: 6.3 L/min). The results point to the fact that for aquatic microalgae viability it is not the specific type of jet that plays the most important role but the general turbulence and mixing induced by the plunging jets. This turbulence might cause more collisions between cells and cells and the tank, more stress leading to higher cell fragility and potentially affect diverse metabolic responses finally contributing to increased cell mortality.

Continuous measurements of total emitted aerosol concentrations highlighted large differences for FW and SW strains, with concentrations 100 times higher during the latter. This can be explained by the emission of salt particles in SW experiments (see Fig. 7a) that were not present in FW experiments, while both FW and SW experiments contained microalgae, bionts and potentially fragments of both (‘microalgae ensemble’). In contrast, microscopy analysis of aerosolized microalgal cells pointed towards higher abundances for the FW strain (impinger results). Aerosolised total number concentrations were also affected by the type of treatment chosen to produce bubbles. This was also previously found comparing emitted number concentrations using a plunging jet or a diffuser72. The results of aerosol spectrometers showed that SJ produced more aerosol particles from a SW environment, while MJ led to higher concentrations from a FW environment. These findings are in line with previous laboratory results using other microalgal strains15 and salts73. Airborne microalgal cells measured by microscopy (impinger results) showed no significant dependence on treatment, while FCM, on the other hand, found higher emissions during MJ in both FW and SW strains.

Size distribution measurements of airborne FW and SW microalgae ensemble revealed slightly larger particles for the SW strain and no distinct differences between treatments (SJ vs. MJ). In general, particles up to ~4 μm in diameter were found, which is slightly smaller compared to the measured cell size dimensions of the chosen microalgae of ~5–7 μm in water. This difference could be due to the higher pressure microalgae are exposed to in air which could lead to cell shrinkage/deformation74,75,76. Another reason could be due to a wrong choice of the index of refraction (IR) used to assess the diameters of aerosol particles in the spectrometers. Recalculation of the actual particle diameters is cumbersome, as the aerosolised fraction is a combination of different compounds, having different optical properties, and thus different IR. Both OPSS and WELAS used an IR of 1.59 (IR of polystyrene latex spheres) to relate the scattered light intensity to the particle diameter. However, aerosolised particles in this study are not expected to have such a high IR. Inorganic salt particles typically have an IR of 1.5477 with a pure scattering signal. Microalgae have been found to have a complex IR of ~1.35 ± 0.00378,79, bacteria of 1.38–1.54 ± 0.000157–0.01280,81 and bioaerosols in general between 1.25 and 1.70 ±0–0.482. These values are representative of a wavelength spectrum between ~0.35–0.65 μm, comparable to the light source used in WELAS83. Thus, the actual diameters of the aerosolised particles in this study, as seen in Figs. 3 and 4, are probably underestimated.

The aerosol size distributions further elucidate that it was not possible to differentiate between the microalgae ensemble and other emitted compounds (e.g. salts), as size distributions of ‘pure salt’ and ‘salt and algae’ experiments were indistinguishable (Fig. 4). We further investigated potential effects of varying pump flow rates on the emitted size distributions: additional experiments with salts (Exp. SiSS) were conducted at pump settings SJ1, SJ3 and SJ9 to compare to Exp. SW5. Number concentrations increased with increasing pump velocity both for ‘pure salt’ and ‘salt and algae’ experiments (Fig. S15). The shape of the number and surface size distributions was quite distinct between the different pump settings but comparable between the ‘pure salt’ and ‘salt and algae’ experiments (Fig. S16 and S17). Previous field measurements at the Baltic Sea found a large fraction of bioaerosols in the size range above 0.8 μm84; these results were based on size distributions and simultaneous fluorescence measurements. However, the salinity in the Baltic campaign was much lower compared to our SW experiments (~7 g/kg vs. 350 g/kg in our study). Thus, an interference from large salt particles above 0.8 μm, as found in our study, may have been less significant. Nonetheless, our results underscore the importance of combining aerosol spectrometers with a second specialised technique to quantify bioaerosol emissions.

Additionally, the viability of aerosolised microalgal cells was investigated, showing that more than half of the organisms were intact (viable) upon emission, both in FW and SW strains, but none could be revived in recovery assessment. Thus, their long-range transport might occur during for example convective conditions but colonisation is expected to be limited. This result could also point to an important impact by factors such as light intensity and time of revival during cultivation76. Further experiments are needed to assess such effects. During their transit in the atmosphere, they might serve as ice nucleating particles or CCN. Ice nucleation active (INA) compounds, including certain proteins and polysaccharides, have formerly been associated with several airborne and aquatic microalgae14. Such INA molecules could still trigger ice formation even if the airborne microalgae are dead [e.g.85]. To confirm IN activity, further investigation would be necessary (beyond the scope of the present paper). However, due to their confirmed aerosolization ability, both investigated haptophyte strains might affect the formation and properties of ice and liquid clouds.

A concurrent release of the microalgae ensemble and DMS were measured during bubbling, while background levels of aerosols and DMS were recorded when bubbling was stopped, highlighting the importance of bubbles in the air-sea exchange of volatile compounds in this study. DMS emissions from lakes have typically been found to be considerably lower than those from over the ocean45,46,47, while our laboratory results delineate comparable DMS emissions for FW and SW experiments. A potential explanation could be that while the processes of DMS release are comparable, the conditions encountered in real FW and SW environments vary, thus leading to different atmospheric results? Besides, the diversity in microalgae producing DMS is typically higher in the ocean compared to FW environments. Another interesting observation of our study is related to the decay of DMS throughout the course of the experiment: The decay during FW experiments appears to occur faster than during SW experiments. In particular, during FW-SJ9 DMS decreased linearly with a slope of -0.067 ppb/min, while during SW-SJ9 DMS decreased linearly with a slope of -0.012 ppb/min. In MJ treatments, the decreases appeared even more different between FW and SW experiments, with a linear decrease (slope of -0.025 ppb/min) in FW-MJ3 and an exponential decrease (slope of -0.014 ppb/min) in SW-MJ3. In addition, our study indicates that DMS decay rates are independent of the total number of particles emitted, i.e. while DMS decays over time, the emitted aerosol concentration remained constant in both FW and SW experiments. Our results also highlight that a larger fraction of emitted particles is not correlated with a higher DMS mixing ratio.

During SW experiments, a clear relation between water pump velocity (i.e. SJ1 vs. SJ9), emitted aerosol concentration as well as DMS mixing ratios was found. In SW experiments, an increase in emitted particle concentration with increasing pump velocity was observed, as found earlier73. However, previous experiments for a different type of FW microalgae performed with the same laboratory setup in Tesson et al.15, highlighted an opposing trend. The gas transfer between the ocean and the atmosphere is expected to increase with increasing wind velocity39. Soluble and moderately soluble compounds such as DMS are believed to have a negligible bubble-mediated gas transfer, while waterside gas transfer dominates39,40. Previous studies have found that at elevated wind speeds above ~10 m/s a non-linear transfer of DMS with wind speed occurs, leading to a flattening of DMS transfer rates39,86. This is ascribed to wind-wave interactions, mesoscale processes and the amphiphilic nature of DMS. The settings in the laboratory experiments in this study cannot directly be related to wind speed scenarios in the ambient environment; a higher pump setting reflects though stronger entrainment of air into the liquid. The clear increase in DMS mixing ratios with increasing pump velocity points to a very fast sea-air exchange response of DMS during our experiments.

Finally, results indicate that dispersal of the studied microalgae strains over geographic scales is not probable, while their potential impact on climate is driven by their release of DMS with implications for new particle formation in the atmosphere and influence on cloud formation. More studies are needed to unravel the effects of other DMS producing microalgae and mixtures of co-occurring types of organisms capable of emitting DMS to investigate potential cumulative effects.

Methods

Microalgal strains

Two haptophyte strains were investigated: the FW species Chrysochromulina parva (CCMP291, BIGELOW culture collection) was cultivated in Modified Wright’s Cryptophyte medium87. The SW species Chrysotila dentata was cultivated in L1+Si medium with a salinity of 3.5%88. This strain was ordered as CCMP284 (BIGELOW culture collection) but genetic analyses demonstrated that the strain belongs to Chrysotila dentata. The 18S ribosomal DNA gene of the two strains was amplified as described in Tesson et al.89. Sequences were aligned against GenBank nucleotide library using Blastn function. Alignment of the 18S sequences of the FW strain (467 bp; PV799978) belong to Chrysochromulina parva (99.79% identity with AM491019.2) and of the SW strain (436 bp; PV799979) to Chrysotila dentata, also called Pleurochrysis dentata (100% identity with KJ756811). In the article, the two haptophyte strains are mentioned by their habitat characteristics, i.e., FW and SW strains. Strains were grown in a controlled climate room at 15 °C, 25–30 μmol photons m−2 s−1, 12 h light: 12 h dark.

Cultures were non-axenic indicating that associated prokaryotes were present in the culture. Prokaryotes were present attached to the microalgal cells or free-living in the culture medium. Visualisation of microalgal bionts was performed by epifluorescence microscopy as described in Tesson et al.15 (Fig. S2).

Experimental procedure

The experimental setup was comparable to the one described in Tesson et al.15. A stainless-steel sea spray generation tank was used to investigate the aerosolization potential of microalgae by simulating processes occurring during wave breaking90. A schematic illustrating the measurement setup is presented in Fig. S18. For SW experiments, an aqueous solution containing synthetic sea salt with the composition: 55% Cl−, 31% Na+, 8% \({{\rm{S}}{\rm{O}}}_{4}^{2-}\), 4% Mg2+, 1%K+, 1%Ca2+, <1% other (Sigma Aldrich S9883; mass fractions) was mixed with MilliQ water (EMD Millipore, 18.2 MΩ ⋅ cm at 25 °C resistivity, 2 ppb TOC) to reach a salinity of 3.5% (35 psu), as is most common in the ocean91. The salinity during the experiments was measured using a portable refractometer (Bie and Berntsen A.S., Denmark) to be 3% (measured during experiment SW5). For FW experiments, pure MilliQ water was used. The tank finally contained 10 L of solution and ~5 L of head-space. pH was monitored during experiments by using Dosatest® pH test strips (pH0-14, REF 85410.601, VWR, Germany). The tank was either operated with a single plunging jet (SJ; nozzle diameter 4 mm) or by multiple jets (MJ; eight 2 mm nozzles). The MJ design is configured to have a 12° angle with respect to the vertical axis. The water flow rates were dependent on the pump setting and specific jet: SJ with pump setting 1 (SJ1) amounted to 2.44 L/min, SJ3 to 4.5 L/min and SJ9 to 6.3 L/min; MJ with pump setting 3 (MJ3) to 8.7 L/min. Particularly SJ9 and MJ3 were chosen as they reached highest particle number concentrations. Detailed information about the tank can be found in Butcher73. Before treatments a Homogenisation step was included using SJ9 for 10 min to provide a homogenised suspension of salt or FW and microalgae ensemble.

Clean sweep air (5 L/min in Exp. SW1, SW2, SW3, FW1, FW2, FW3 and 10 L/min in Exp. SW4, SW5, SiSS) was pushed through the head-space, providing slightly more air than needed by the connected instruments. Techniques to monitor aerosolised particles and emitted gases were directly connected to the head-space. Potential wall and bottom effects were not considered.

Aerosol particle instrumentation

The aerosolised fraction was continuously monitored with an optical particle size spectrometer (OPSS 3330; TSI) and a white-light aerosol spectrometer (WELAS 2300; Palas). The OPSS utilised a flow of 1 L/min to monitor particles with diameters between 0.3 μm to 10 μm optical diameters in 16 bins, while the WELAS had a flow rate of 5 L/min and was set to measure particles from 0.25 μm to 10 μm optical diameters in 59 bins. As the OPSS was available during all experiments, total aerosol concentrations are only provided from OPSS. Total number concentrations in Exp. SW4 and SW5 were multiplied by a factor of 2, due to the dilution by the increased sweep air in these experiments compared to the other experiments. Dry aerosol properties were measured by placing a silica gel diffusion dryer in front of OPSS and WELAS. The diameters of the OPSS and WELAS measurements shown in Figs. 3 and 4 represent sizes of particles with a scattering potential comparable to that of polystyrene latex spheres (PSL) with an IR of 1.59.

Aerosolised organisms were also collected in an impinger (NS 29/32 25 × 250 mm, Assistant, Duran) for a duration of ~1 h with a flow rate of 2 L/min and 50 mL of culture medium (as described in ref. 92).

Gas-phase instrumentation

Continuous emissions of VOCs were monitored in the mass to charge ratio range of 21–200 with a Proton Transfer Reaction Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer (PTR-ToF-MS 4000, Ionicon Analytik). An E/N ratio of 132 Td was used with a drift tube voltage of 900 V, a drift tube pressure of 3.4 mbar and a drift tube temperature of 77 °C. A flow rate of 0.2 L/min was used. Data were analysed with PTR-MS Viewer 3.2.12 (Ionicon). DMS mixing ratios in Exp. SW4 and SW5 were multiplied by a factor of 2, due to the dilution by the increased sweep air in these experiments compared to the other experiments (10 L/min vs. 5 L/min sweep air).

For VOC compound validation, Tenax tube samples were collected by active sampling onto stainless steel thermal desorption tubes (Tenax GR/Anasorb GCB1, SKC) with a flow rate of 0.2 L/min for on average 10 min per tube. The collected samples were analysed by thermal desorption (TD-100, Markes) followed by gas chromatography (GC, 6890 N Network GC System, Agilent Technologies) with mass spectrometry (MS, 5973 Network Mass Selective Detector, Agilent Technologies). The gas chromatograph was equipped with a HP-INNOWAX 19091N-133 column (30 m × 0.250 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent Technologies). The GC oven was programmed to 40 °C (held for 4 min) then ramped to 250 °C (held for 4 min) at a heating rate of 10 °C per min. Thermal desorption was performed at 200 °C for 10 min onto the −10 °C cold trap which was subsequently heated to 320 °C at maximum heating rate for 3 min. Compound identification and verification were performed using the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology, EI-MS mainlib) MS library and comparison with authentic DMS (99%, Sigma Aldrich) and DMSO (99.9%, Sigma Aldrich) standards analysed using the above method.

Dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) measurements

Samples of bulk water as well as impinger were analysed by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry. To preserve DMSP in the water sample, it was spiked with 50 μL of 85% orthophosphoric acid. 5.00 mL of sample was loaded into a 20 mL crimp top vial and spiked with 500 μL of 10 M NaOH to perform laboratory breakdown of DMSP to DMS93.

All analyses were performed on a GC-MS 7890B/5977A (Agilent, USA) equipped with a cooled CIS4 and MPS2 autosampler system (Gerstel, Germany). Separation of analytes was conducted using a capillary 30 m × 0.25 mm HP-5ms column (Agilent Technologies, USA) with a 0.25 μm film thickness at a constant helium (99.9999% purity, Denmark) flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The oven was programmed from 30 °C (held for 3 min) to 35 °C (held for 3 min) at a heating rate of 5 °C min−1, then ramped to 280 °C (held for 3 min) with a heating rate of 30 °C min−1. The total GC run time was 18.17 min.

Commercially available sorbent tubes filled with Carbopack B were employed for trapping volatile compounds from the head-space. The DHS method was configured with the following parameters: incubation temperature 30 °C, trapping gas volume 250 mL, trapping gas flow rate 100 mL min−1, sample temperature 30 °C, sorption tube temperature 30 °C. The transfer line heater was set to 120 °C for the remainder of the sample preparation process. Prior to analysis, the sorbent tube was dried using 300 mL of purge gas at a flow rate of 100 mL min-1 and a tube temperature of 40 °C to remove residual moisture. The developed DHS method enables the detection of trace levels of DMSP, with the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) determined to be 0.0075 μg L−1 and 0.025 μg L−1, respectively. The detailed procedure is explained in Bektassov et al.70.

Microalgal abundance and viability

Total number of microalgae from bulk water and impinger were assessed from a volume of 1 mL of sample collected in triplicate both in the initial culture and during the experiment phases (after water Homogenisation and after each SJ and MJ treatment), and fixed in a 4% concentration of neutral Lugol.

Alive fraction of the microalgae in the bulk water and in the impinger was assessed, in triplicate, on 1 mL sample fixed with 200 μL of 1:100 Neutral red solution (0.1% w/v 40 μL/mL;94). The vital dye penetrates and stains living organisms. All samples were stored at 4 °C in the dark for at least 3 h before assessment. Abundance assessment was performed using a 1 mL Sedgewick rafter chamber and an inverted light microscope (Axiovert 135 M, Zeiss)15. Dilution factors were applied on dense samples.

A volume of 200 μL of sample in Exp. FW3, SW3, SW4 and SW5 was collected in triplicate and analysed by FCM as described in Tesson et al.15 to investigate the total number of cells, the percentage of dead cells, the organismal pigmentation and the variation in organismal size during the different settings. Propidium iodide (1 mg/1 mL, Sigma) was used to stain damaged and dead organisms. The pigment profile of the two microalgal strains was based on dot-plot of forward scatter signal versus auto-fluorescence for chlorophylls (0.675 μm, blue filter) and phycobilin proteins, i.e. allophycocyanin (0.675 μm, red filter) and phycoerythrin (0.572 μm, blue filter). As expected in Haptophytes, positive signals were registered only for chlorophylls95.

Revival capacity of aerosolised microalgae was assessed via cultivation (recovery experiment)15. A volume of 250–500 μL of well-mixed liquid phase from the impinger after each setting was collected in 23 up to 46 replicates and incubated in a 48-well culture plate (Sarstedt and Cellstart® Greiner Bioone) at 15 °C under conditions favouring growth (see above). A positive control composed of 500 μL of the initial culture and a negative control of medium were added to each plate. Culture growth in the controls and the inoculates was checked under the microscope every 2 weeks and up to 2 months.

Data availability

Most of the data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files and all raw and analyzed data are avaiable at the Zenodo repository https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18078207.

References

Forster, P. et al. The earth’s energy budget, climate feedbacks, and climate sensitivity. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, vol. 2021, 923-1054 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2021).

Bellouin, N. et al. Bounding global aerosol radiative forcing of climate change. Rev. Geophys. 58, e2019RG000660 (2020).

Despres, V. R. et al. Primary biological aerosol particles in the atmosphere: a review. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 64, 15598 (2012).

Wiśniewska, K., Lewandowska, A. & Śliwińska Wilczewska, S. The importance of cyanobacteria and microalgae present in aerosols to human health and the environment—review study. Environ. Int. 131, 104964 (2019).

Orellana, M. V. et al. Marine microgels as a source of cloud condensation nuclei in the high arctic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 13612–13617 (2011).

Šantl-Temkiv, T., Amato, P., Casamayor, E. O., Lee, P. K. H. & Pointing, S. B. Microbial ecology of the atmosphere. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 46, fuac009 (2022).

Tesson, S. V. M., Skjøth, C. A., Šantl-Temkiv, T. & Löndahl, J. Airborne microalgae: insights, opportunities, and challenges. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 1978–1991 (2016).

Marks, R., Górecka, E., McCartney, K. & Borkowski, W. Rising bubbles as mechanism for scavenging and aerosolization of diatoms. J. Aerosol Sci. 128, 79–88 (2019).

Broady, P. A. Diversity, distribution and dispersal of antarctic terrestrial algae. Biodivers. Conserv. 5, 1307–1335 (1996).

Kristiansen, J. 16. dispersal of freshwater algae—a review. Hydrobiologia 336, 151–157 (1996).

Hirst, J. M., Stedman, O. J. & Hogg, W. H. Long-distance spore transport: methods of measurement, vertical spore profiles and the detection of immigrant spores. Microbiology 48, 329–355 (1967).

Hirst, J. M., Stedman, O. J. & Hurst, G. W. Long-distance spore transport: vertical sections of spore clouds over the sea. Microbiology 48, 357–377 (1967).

Hoose, C. & Möhler, O. Heterogeneous ice nucleation on atmospheric aerosols: a review of results from laboratory experiments. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 9817–9854 (2012).

Tesson, S. V. M. & Šantl Temkiv, T. Ice nucleation activity and aeolian dispersal success in airborne and aquatic microalgae. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2681 (2018).

Tesson, S. V. M., Barbato, M. & Rosati, B. Aerosolization flux, bio-products, and dispersal capacities in the freshwater microalga Limnomonas gaiensis (Chlorophyceae). Commun. Biol. 6, 809 (2023).

Kameyama, S. et al. Application of ptr-ms to an incubation experiment of the marine diatom thalassiosira pseudonana. Geochem. J. 45, 355–363 (2011).

Achyuthan, K. E., Harper, J. C., Manginell, R. P. & Moorman, M. W. Volatile metabolites emission by in vivo microalgae-an overlooked opportunity? Metabolites 7, 39 (2017).

Rocco, M. et al. Oceanic phytoplankton are a potentially important source of benzenoids to the remote marine atmosphere. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 175 (2021).

Alcolombri, U. et al. Identification of the algal dimethyl sulfide-releasing enzyme: a missing link in the marine sulfur cycle. Science 348, 1466–1469 (2015).

Andreae, M. O. & Crutzen, P. J. Atmospheric aerosols: biogeochemical sources and role in atmospheric chemistry. Science 276, 1052–1058 (1997).

Bates, T., Lamb, B., Guenther, A., Dignon, J. & Stoiber, R. Sulfur emissions to the atmosphere from natural sourees. J. Atmos. Chem. 14, 315–337 (1992).

Simó, R. Production of atmospheric sulfur by oceanic plankton: biogeochemical, ecological and evolutionary links. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 287–294 (2001).

Perraud, V. et al. The future of airborne sulfur-containing particles in the absence of fossil fuel sulfur dioxide emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 13514–13519 (2015).

Andreae, M. O. Ocean-atmosphere interactions in the global biogeochemical sulfur cycle. Mar. Chem. 30, 1–29 (1990).

Keller, M. D. Dimethyl sulfide production and marine phytoplankton: the importance of species composition and cell size. Biol. Oceanogr. 6, 375–382 (1989).

Deng, X., Chen, J., Hansson, L.-A., Zhao, X. & Xie, P. Eco-chemical mechanisms govern phytoplankton emissions of dimethylsulfide in global surface waters. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa140 (2020).

Kiene, R. P. & Bates, T. S. Biological removal of dimethyl sulphide from sea water. Nature 345, 702–705 (1990).

Lomans, B., Van der Drift, C., Pol, A. & Op den Camp, H. Microbial cycling of volatile organic sulfur compounds. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 575–588 (2002).

Brimblecombe, P. & Shooter, D. Photo-oxidation of dimethylsulphide in aqueous solution. Mar. Chem. 19, 343–353 (1986).

Bouillon, R.-C. & Miller, W. L. Photodegradation of dimethyl sulfide (DMS) in natural waters: Laboratory assessment of the nitrate-photolysis-induced DMS oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 9471–9477 (2005).

Vallina, S. M. & Simó, R. Strong relationship between DMs and the solar radiation dose over the global surface ocean. Science 315, 506–508 (2007).

Carslaw, K. S. et al. A review of natural aerosol interactions and feedbacks within the Earth system. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 1701–1737 (2010).

Quinn, P. K. & Bates, T. S. The case against climate regulation via oceanic phytoplankton sulphur emissions. Nature 480, 51–56 (2011).

Bock, J. et al. Evaluation of ocean dimethylsulfide concentration and emission in CMIP6 models. Biogeosciences 18, 3823–3860 (2021).

Bhatti, Y. A. et al. The sensitivity of southern ocean atmospheric dimethyl sulfide (DMS) to modeled oceanic DMS concentrations and emissions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 15181–15196 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Atmospheric dimethyl sulfide and its significant influence on the sea-to-air flux calculation over the southern ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 186, 102392 (2020).

Woolf, D. et al. Modelling of bubble-mediated gas transfer: fundamental principles and a laboratory test. J. Mar. Syst. 66, 71–91 (2007).

Zavarsky, A. et al. The influence of air-sea fluxes on atmospheric aerosols during the summer monsoon over the tropical Indian Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 418–426 (2018).

Zavarsky, A., Goddijn-Murphy, L., Steinhoff, T. & Marandino, C. A. Bubble-mediated gas transfer and gas transfer suppression of DMS and CO2. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 6624–6647 (2018).

Bell, T. G. et al. Estimation of bubble-mediated air–sea gas exchange from concurrent DMS and CO2 transfer velocities at intermediate–high wind speeds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 9019–9033 (2017).

Deike, L. et al. A universal wind-wave-bubble formulation for air-sea gas exchange and its impact on oxygen fluxes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 122, e2419319122 (2025).

Wang, W.-L. et al. Global ocean dimethyl sulfide climatology estimated from observations and an artificial neural network. Biogeosciences 17, 5335–5354 (2020).

Novak, G. A., Kilgour, D. B., Jernigan, C. M., Vermeuel, M. P. & Bertram, T. H. Oceanic emissions of dimethyl sulfide and methanethiol and their contribution to sulfur dioxide production in the marine atmosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 6309–6325 (2022).

Kurosaki, Y., Matoba, S., Iizuka, Y., Fujita, K. & Shimada, R. Increased oceanic dimethyl sulfide emissions in areas of sea ice retreat inferred from a Greenland ice core. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 327 (2022).

Ginzburg, B. et al. DMS formation by dimethylsulfoniopropionate route in freshwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32, 2130–2136 (1998).

Sharma, S., Barrie, L. A., Hastie, D. R. & Kelly, C. Dimethyl sulfide emissions to the atmosphere from lakes of the Canadian Boreal Region. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 104, 11585–11592 (1999).

Steinke, M., Hodapp, B., Subhan, R., Bell, T. G. & Martin-Creuzburg, D. Flux of the biogenic volatiles isoprene and dimethyl sulfide from an oligotrophic lake. Sci. Rep. 8, 630 (2018).

Bechard, M. J. & Rayburn, W. R. Volatile organic sulfides from freshwater algae. J. Phycol. 15, 379–383 (1979).

Marandino, C. A., De Bruyn, W. J., Miller, S. D. & Saltzman, E. S. DMS air/sea flux and gas transfer coefficients from the north Atlantic summertime coccolithophore bloom. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, 23 (2008).

Owen, K. et al. Natural dimethyl sulfide gradients would lead marine predators to higher prey biomass. Commun. Biol. 4, 149 (2021).

Yan, S.-B. et al. High-resolution distribution and emission of dimethyl sulfide and its relationship with pCO2 in the northwest Pacific Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1074474 (2023).

Charlson, R. J., Lovelock, J. E., Andreae, M. O. & Warren, S. G. Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate. Nature 326, 655–661 (1987).

Barnes, I., Hjorth, J. & Mihalopoulos, N. Dimethyl sulfide and dimethyl sulfoxide and their oxidation in the atmosphere. Chem. Rev. 106, 940–975 (2006).

Sipilä, M. et al. The role of sulfuric acid in atmospheric nucleation. Science 327, 1243–1246 (2010).

Chen, Q., Sherwen, T., Evans, M. & Alexander, B. DMS oxidation and sulfur aerosol formation in the marine troposphere: a focus on reactive halogen and multiphase chemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 13617–13637 (2018).

Wollesen de Jonge, R. et al. Secondary aerosol formation from dimethyl sulfide—improved mechanistic understanding based on smog chamber experiments and modelling. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 9955–9976 (2021).

Fung, K. M. et al. Exploring dimethyl sulfide (DMS) oxidation and implications for global aerosol radiative forcing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 1549–1573 (2022).

Cala, B. A. et al. Development, intercomparison, and evaluation of an improved mechanism for the oxidation of dimethyl sulfide in the UKCA model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 14735–14760 (2023).

Rosati, B. et al. New particle formation and growth from dimethyl sulfide oxidation by hydroxyl radicals. ACS Earth Space Chem. 5, 801–811 (2021).

Shen, J. et al. High gas-phase methanesulfonic acid production in the oh-initiated oxidation of dimethyl sulfide at low temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 13931–13944 (2022).

Goss, M. B. & Kroll, J. H. Chamber studies of oh + dimethyl sulfoxide and dimethyl disulfide: insights into the dimethyl sulfide oxidation mechanism. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 1299–1314 (2024).

Boucher, O. & Lohmann, U. The sulfate-ccn-cloud albedo effect. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 47, 281–300 (1995).

Hudson, J. G. & Da, X. Volatility and size of cloud condensation nuclei. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 101, 4435–4442 (1996).

Park, K.-T. et al. Dimethyl sulfide-induced increase in cloud condensation nuclei in the Arctic atmosphere. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 35, e2021GB006969 (2021).

Rosati, B. et al. Hygroscopicity and CCN potential of DMS-derived aerosol particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 13449–13466 (2022).

Hoffmann, E. H. et al. An advanced modeling study on the impacts and atmospheric implications of multiphase dimethyl sulfide chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 11776–11781 (2016).

Revell, L. E. et al. The sensitivity of Southern Ocean aerosols and cloud microphysics to sea spray and sulfate aerosol production in the HadGEM3-GA7. 1 chemistry–climate model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 15447–15466 (2019).

Nicholls, K. H. 13 - haptophyte algae. In Freshwater Algae of North America, Aquatic Ecology (eds Wehr, J. D. & Sheath, R. G.) 511–521 (Academic Press, Burlington, 2003).

Dahl, E., Bagøien, E., Edvardsen, B. & Stenseth, N. C. The dynamics of Chrysochromulina species in the Skagerrak in relation to environmental conditions. J. Sea Res. 54, 15–24 (2005).

Bektassov, M. et al. Dynamic headspace gas chromatography—mass spectrometry method for determination of dimethyl sulfide and indirect quantification of dimethylsulfoniopropionate in environmental water samples. Adv. Sample Prep. (2025).

Rocco, M. et al. Relating dimethyl sulphide and methanethiol fluxes to surface biota in the south-west pacific using shipboard air-sea interface tanks. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 130, e2024JD041072 (2025).

Christiansen, S., Salter, M. E., Gorokhova, E., Nguyen, Q. T. & Bilde, M. Sea spray aerosol formation: Laboratory results on the role of air entrainment, water temperature, and phytoplankton biomass. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 13107–13116 (2019).

Butcher, A. C. Sea Spray Aerosols: Results from Laboratory Experiments. Phd thesis, University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Science, Department of Chemistry (2013).

Potts, M. Desiccation tolerance of prokaryotes. Microbiol. Rev. 58, 755–805 (1994).

Alsved, M. et al. Effect of aerosolization and drying on the viability of Pseudomonas syringae cells. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2018 (2018).

Chiu, C.-S. et al. Mechanisms protect airborne green microalgae during long distance dispersal. Sci. Rep. 10, 13984 (2020).

Zieger, P. et al. Revising the hygroscopicity of inorganic sea salt particles. Nat. Commun. 8, 15883 (2017).

Lee, E., Heng, R.-L. & Pilon, L. Spectral optical properties of selected photosynthetic microalgae producing biofuels. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 114, 122–135 (2013).

Qi, H., He, Z.-Z., Zhao, F.-Z. & Ruan, L.-M. Determination of the spectral complex refractive indices of microalgae cells by light reflectance-transmittance measurement. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 41, 4941–4956 (2016).

Arakawa, E., Tuminello, P., Khare, B. & Milham, M. Optical properties of erwinia herbicola bacteria at 0.190–2.50 μm. Biopolym. Orig. Res. Biomol. 72, 391–398 (2003).

Hart, S. J., Terray, A. V., Kuhn, K. L., Arnold, J. & Leski, T. A. Optical chromatography for biological separations. In Optical Trapping and Optical Micromanipulation Vol. 5514, 35–47 (SPIE, 2004).

Hu, Y. et al. Significant broadband extinction abilities of bioaerosols. Sci. China Mater. 62, 1033–1045 (2019).

Rosati, B. et al. The white-light humidified optical particle spectrometer (whops)—a novel airborne system to characterize aerosol hygroscopicity. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 921–939 (2015).

Freitas, G. P. et al. Emission of primary bioaerosol particles from Baltic seawater. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 2, 1170–1182 (2022).

Hartmann, S. et al. Immersion freezing of ice nucleation active protein complexes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 5751–5766 (2013).

Vlahos, P. & Monahan, E. C. A generalized model for the air-sea transfer of dimethyl sulfide at high wind speeds. Geophys. Res. Lett 36, 21 (2009).

Guillard, R. R. L. & Lorenzen, C. J. Yellow-green algae with chlorophyllide c1,2. J. Phycol. 8, 10–14 (1972).

Guillard, R. R. L. & Hargraves, P. E. Stichochrysis immobilis is a diatom, not a chrysophyte. Phycologia 32, 234–236 (1993).

Tesson, S. V. M. & Sildever, S. The ph tolerance range of the airborne species Tetracystis vinatzeri (Chlorophyceae, Chlamydomonadales). Eur. J. Phycol. 0, 1–11 (2023).

King, S. M. et al. Investigating primary marine aerosol properties: CCN activity of sea salt and mixed inorganic-organic particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 10405–10412 (2012).

Lewis, E. & Schwartz, S. Sea Salt Aerosol Production: Mechanisms, Methods, Measurements and Models (American Geophysical Union, 2004).

Grinshpun, S. A. et al. Effect of impaction, bounce and reaerosolization on the collection efficiency of impingers. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 26, 326–342 (1997).

van Rijssel, M. & Gieskes, W. W. Temperature, light, and the dimethylsulfoniopropionate (dmsp) content of emiliania huxleyi (prymnesiophyceae). J. Sea Res. 48, 17–27 (2002).

Zetsche, E.-M. & Meysman, F. J. R. Dead or alive? Viability assessment of micro- and mesoplankton. J. Plankton Res. 34, 493–509 (2012).

Eikrem, W. et al. Haptophyta. In Handbook of the Protists (ed Archibald, J.M. et al.) (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sirje Sildever for technical support. The authors are grateful to the Aarhus University, Biology Department, Microbiology and Aquatic Biology units for access to environmental climate chamber and laboratory facilities. Flow cytometry was performed at the FACS Core Facility, Aarhus University, Denmark. The authors also thank Anders Feilberg for the constructive discussions and access to the PTR-ToF-MS. The authors thank Nassiba Baimatova and Dina Orazbayeva for constructive discussions on the optimisation of the DHS-GS-MS method. B.R., J.T.S. and Z.T. were funded by a research grant from Villum Fonden (42128). S.T. was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska Curie grant agreement no. 754513 and The Aarhus University Research Foundation Villum Fonden (23175), and the Independent Research Fund Denmark (9145-00001B). B.R. and M.B. were funded by Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF19OC0056963) and M.B. and M.G. acknowledge the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF172) through the Center of Excellence for Chemistry of Clouds. M.Be. was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Higher Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (No.AP25796583 (2025-2027), AP26197327 (2025-2027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.R. and S.V.M.T. conceived and designed the study. B.R. and S.V.M.T. performed the experiments assisted by J.T.S. and K.V.K. B.R. analysed OPSS and WELAS as well as PTR-ToF-MS data. S.V.M.T. analysed microalgae data from the impinger and bulk water. M.Be. and Z.T. performed the DMSP measurements and analyses supervised by M.G., M.Ba. the bionts analysis and K.V.K. the Tenax tube analysis. M.Bi. and M.G. contributed to interpreting the results. B.R. and S.V.M.T. wrote the original draft manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. All authors read and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Genetic sequences are available on GenBank (PV799978-PV799979, URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/). The authors declare a potential competing interest with the culture collection Bigelow - National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota. We ordered the microalgal culture CCMP284, but received another microalgal species (taxonomy confirmed by genetic analyses). We notified the culture collection and repeatedly contact them, but did not received any clarifications. In the study, we refer to the investigated CCMP284 microalgae using its here-determined genetic name (Chrysotila dentata).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosati, B., Skønager, J.T., Bektassov, M. et al. Aerosolisation of microalgae: unveiling dimethyl-sulfide emissions during bubbling. npj Clim Atmos Sci 9, 32 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01305-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01305-4