Abstract

The mountainous Third Pole is a critical source of freshwater for water resource management across Asia, yet the historical and future dynamics of per-capita freshwater supply in this region remain poorly constrained by observations from a coherent, pan-regional perspective. Here, we show that by the end of the 21st century, mountain runoff in the Third Pole’s monsoon domain will increase substantially, whereas runoff in the westerlies domain will experience a non-significant decline. This finding challenges the prevailing paradigm that future runoff across the entire Third Pole will follow a unidirectional increasing trend as future precipitation. Regarding long-term freshwater availability till the end-of-21-century (1960‒2100), although mountain runoff shows a contrasting pattern with increase (decrease) at first and then decrease (increase) in the westerlies (monsoon) domain, the per-capita freshwater supply (for mountain basins and their downstream dependent regions) drops a lot in both westerlies and monsoon domains from the past (1960‒1970) to the near future (2030‒2050) due to rapid population increase. These findings provide vital information to cope with fast-growing water demands and achieve Sustainable Development Goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Tibetan Plateau and surrounding high mountains—known as the Earth’s Third Pole (TP)—play a key role in the global hydrological cycle and climate system1. As the source of major Asian rivers (e.g., Yangtze, Yellow, Brahmaputra, Indus), it acts as a critical “water tower”2, sustaining billions downstream3,4. Understanding TP runoff changes is scientifically important and vital for water management, ecosystem protection, food/energy security, and regional sustainability5,6. Over the past 50 years, the TP has seen notable climate shifts7. The westerlies (strengthened) and monsoons (weakened)—the region’s dominant atmospheric circulations—have altered local precipitation and runoff. Meanwhile, high-elevation TP warming has outpaced the global average8, causing significant changes in solid water storage, primarily glacier retreat9. Accelerated glacial melt releases more freshwater into rivers, profoundly impacting runoff.

Recent studies have marked progress on projecting the future TP runoff by using cryosphere-hydrology models or Artificial Intelligence driven by the latest global climate projections. For example, Khanal et al. show that the 15 upstream TP basins have relatively consistent climate change responses in terms of total water availability for the long-term scales10, but no regional analysis is performed in terms of climate domains; Cui et al. find non-monotonic changes in river flows for seven major TP rivers (Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Mekong, Salween, Yangtze, Yellow) at increasing warming levels11, but without counting the inland rivers at the westerlies domain (e.g., Amu Darya, Syr Darya, Tarim, Heihe, and Shule); Long et al. also project the future runoffs at the same major TP rivers, and find river basins in the monsoon domain will exhibit higher rates of runoff increase compared to those in the westerlies domain12. While numerous studies have projected future runoff in the TP10,11,12,13,14,15,16, two critical unresolved questions hinder evidence-based water resource planning and risk mitigation for downstream communities.

First, future runoff trends in major TP river basins remain debated. Some model simulations project unidirectional increases in 21st-century runoff, driven by accelerated glacial melt and warming-enhanced precipitation; others suggest runoff will peak by mid-century then decline, as glacial storage is exhausted and precipitation regimes become erratic. This discrepancy arises from variations in data sources (in-situ observations versus remote sensing), model architectures (hydrological models versus Earth system models), and climate forcing scenarios (e.g., SSP245 versus SSP585). Moreover, most studies treat TP as a homogeneous unit, overlooking hydroclimatic differences between sub-domains—such as monsoon-influenced southern basins and westerlies-dominated northern basins—leading to oversimplified projections.

Second, the current status and future trajectories of per capita freshwater supply from the TP rivers remain poorly quantified, due to very limited observation constraints (particularly the river runoffs at high mountains). As a pivotal water security metric, per capita freshwater availability integrates hydrological (runoff volume) and socioeconomic (population size) drivers. Most notably, the lack of sufficient observational constraints on mountain runoff (a previously highlighted challenge) constitutes the most consequential uncertainty in these quantifications. This limitation is compounded in future projections, which rarely account for uncertainties in runoff variability (exacerbated by sparse observations) and population growth, severely undermining assessment reliability for the TP region.

Addressing these two questions is not only essential for advancing hydrological science in high-mountain regions but also for supporting evidence-based policy-making to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 6 (clean water and sanitation) in Asia. Resolving the controversy over future runoff trends and improving the quantification of per-capita water resource dynamics will provide critical insights into the vulnerability of downstream communities to water scarcity, guiding the development of adaptive strategies for water resource management in the TP region.

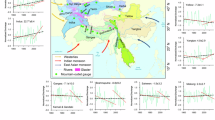

The aim of this study is to quantify the changes in the historical and future per-capita freshwater supply in the TP, and accurately depict the response patterns of river runoff in the TP’s three different climate domains to climate change. The studied TP rivers (Fig. 1) include the westerlies domain (Amu Darya, Syr Darya, Indus, Tarim, Heihe, and Shule rivers), the Indian monsoon domain (Brahmaputra, Ganges, Mekong, and Salween rivers), and the westerlies‒monsoon transition domain (Yangtze and Yellow rivers)4. Under climate change, the westerlies and monsoon systems in the TP region will exhibit significant variations; notably, in a warming world with declining anthropogenic aerosol emissions, the Indian summer monsoon rainfall is projected to intensify—a trend that differs from the observational pattern recorded over the past 40 years7,17. The westerlies dominates the northwestern arid-semiarid zones, where increased temperature may accelerate glacier melt and initially boost river runoff, but long-term glacier depletion could lead to runoff decline. In the southeastern monsoon-dominated humid zones and the middle westerlies-monsoon transition domain (semi-arid to semi-humid zones), intensified precipitation may enhance annual runoff but also elevate the flood risk. This study will deepen our understanding of water resource dynamics in the TP and provide a scientific basis for regional water security and adaptation strategies.

The TP’s westerlies domain (the headwaters of Indus, Amu Darya, Syr Darya, Tarim, Shule, and Heihe rivers; blue color); the monsoon domain (the headwaters of Ganges, Brahmaputra, Salween, and Mekong rivers; green color), and the westerlies-monsoon transition domain (the headwaters of Yellow and Yangtze rivers; yellow color). In the map, blue lines represent the major rivers, and green solid circles mark the mountain-outlet discharge gauges of these high-mountain TP rivers used in this study (see Supplementary Table 1 for details). Colored arrows in the figure indicate large-scale circulation.

Results

Consistent precipitation increase by the end of 21st century

The sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6)-based simulations, spanning multiple shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) such as SSP245 (medium emission), and SSP585 (high emission), uniformly project a notable increase in annual precipitation across all major mountainous basins of the TP by the end of the 21st century (Supplementary Fig. 1). Overall, precipitation in these TP basins shows an increasing trend from 2017 to 2100. For most basins, such as the Yellow, Yangtze, Mekong, Salween, Brahmaputra, Ganges, Tarim, Shule, and Heihe, both scenarios exhibit significant positive linear trends (p <0.05). The slopes of the linear regression equations for SSP585 are steeper than those for SSP245 in these basins, indicating a more pronounced precipitation increase under SSP585. For instance, in the Ganges basin, the slope for SSP585 (6.4 mm/yr) is much larger than that for SSP245 (1.4 mm/yr). Even in basins like the Indus and Amu Darya, where the trend under SSP245 is not significant (p >0.1), precipitation shows a significant increasing trend under SSP585 (p <0.05). Only in the Syr Darya basin does the trend under SSP585 have a p-value >0.05, but it still shows a positive trend similar to SSP245, with SSP585 having a slightly lower slope. In summary, across the 12 TP basins, precipitation is projected to increase, and the increase is more remarkable under the SSP585 scenario compared to SSP245.

This precipitation increase is primarily attributed to intensified atmospheric circulation—specifically, the enhanced transport of moisture from the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea by the South Asian Summer Monsoon (Supplementary Fig. 9c), as well as increased westerly precipitation in winter (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Such a moisture surge holds profound implications for the TP’s water balance: it not only replenishes seasonal snowpack and groundwater reserves but also potentially offsets water loss from accelerated glacier melt, which has long been a major concern for the region’s hydrological stability. For downstream ecosystems and human communities dependent on TP runoff, increased precipitation could alleviate projected water scarcity under high-emission scenarios, yet its actual impact remains contingent on how runoff responds to this precipitation change.

Divergent runoff responses in different climate domains

The projected future river runoffs show diverging trends in the three different climate domains of the TP during 2017‒2100 (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 10). Under both a moderate warming scenario (SSP245) and a high warming scenario (SSP585), results suggest significant (p <0.05) increasing trends of mountain runoffs in the monsoon domain and westerlies‒monsoon transition domain (Supplementary Fig. 10b, c), but no significant runoff trend in the westerlies domain (Supplementary Fig. 10a). This largely-unchanged future runoff trends in the westerlies domain, can be attributed to a counteracting effect between the deceasing mountain runoff trends in the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers (in Central Asia), and the increasing runoff trends in the other four westerlies-dominated rivers (Indus, Tarim, Heihe and Shule; Supplementary Fig. 4). In the basin-scale, the projected future mountain runoffs for all the studied TP rivers show consistent increases under both SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios except for the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers that will have opposite changes (Supplementary Fig. 3), although future precipitation is projected to increase at most studied basins (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In the TP region, the future runoff trends can be well explained by the changes in precipitation minus evapotranspiration (P − ET; Fig. 2d) and glacier melting (represented by the excess discharge of glaciers; Datasets and Methods). For the mountain basins in both the monsoon domain and westerlies‒monsoon transition domain (where rainfall runoff dominates the total runoff), the rapid increase of future P − ET (Fig. 2d) has completely offset the future glacier meltwater decline (Supplementary Fig. 12e, f), leading to a rapid increase in future runoff (Fig. 2a). For the mountain basins in the westerlies domain where glacier melt is a more important contributor, the significant increase in future precipitation (Fig. 2b) has been mostly offset by the significant increase in future ET (Fig. 2c), leading to an insignificant trend in future P − ET (Fig. 2d); while relatively stable glacial meltwater before 2100 (Supplementary Fig. 12d) has finally led to largely-unchanged future mountain runoff in the westerlies domain (Fig. 2a). Within the westerlies domain, projected runoff declines in the Amu Darya and Syr Darya Rivers (Supplementary Figs. 3–4; consistent with Su et al.18 that are CMIP5-driven physical model results) are jointly driven by concurrent increases in precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 1) and evapotranspiration (Supplementary Fig. 6), coupled with a marked reduction in glacial meltwater (Supplementary Fig. 8). In contrast, future runoff of the other four westerlies-dominated rivers (Indus, Tarim, Heihe, Shule) is expected to show a predominantly significant increasing trend—except for the Tarim River under SSP245 (Supplementary Figs. 3–4). This discrepancy arises primarily because precipitation growth rates for these four rivers are substantially higher than those of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya (except for the Indus River under SSP245; Supplementary Fig. 1), while sustained, substantial glacial melt in the Indus and Tarim Rivers (Supplementary Figs. 7–8; consistent with Hassan et al.19 and Latif et al.20) further amplifies the overall runoff increase for the four westerlies-dominated catchments.

FutureΔS (change in terrestrial water storage, including glacier mass balance, soil moisture, and groundwater) will significantly increase in the mountain basins of the monsoon domain and the westerlies-monsoon transition domain under SSP585 (Fig. 2e), which is consistent with the combined effects of remarkable precipitation increase (43.9 ± 2.8 mm/10a and 17.9 ± 1.7 mm/10a for the TP’s monsoon and transition domains respectively; Fig. 2b) and generally declining glacier mass loss rates (Supplementary Fig. 12b, c).

Long-term runoff changes from 1960 to 2100

Regarding the annual runoff amount in the TP from past to future (1960‒2100), we also find divergent changes among the three climate domains (Fig. 3). The mountain runoff in the westerlies domain firstly rises from the past (234 ± 25 mm for 1960‒1970) to the present (266 ± 13 mm for 2006‒2015), then falls in the near future (2030‒2050) for both SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios. Differently, the mountain runoff in the monsoon domain firstly falls about 6.5% from the past (450 ± 27 mm) to the present, then consistently rises to a very high level in the far future (621 ± 15 mm for SSP245 and 684 ± 24 mm for SSP585). Among the three climate domains in the TP, only the westerlies‒monsoon transition domain illustrates a consistent increase in the mountain runoff from the past (129 ± 24 mm) to the far future (172 ± 17 mm for SSP245 and 175 ± 11 mm for SSP585).

History and future dynamics of per-capita freshwater supply

Considering the population dynamics in the mountain-outlet basins and their downstream dependent regions (that are hydrologically connected with upper mountains; see Fig. 4d; Methods)21,22,23, we quantify the annual per-capita water supply (APWS) from the TP’s different climate domains (Fig. 4). Results show that in all the three climate domains, the APWS illustrates an anti-parabolic shape, which is generally opposite to the long-term population changes from the past (1960‒1970) to the far future (2080‒2100). Here we find that the APWS uniformly decreases from the past (1960‒1970) to the present (2006‒2015), which is −53%, −58%, and −29% across all the TP’s three climate domains due to the consistent and rapid population increase in these regions during the past half century (1960s‒2010s). However, in the future, the population is not projected to continuously increase across all the TP’s climate domains. For example, unlike the westerlies and the monsoon domains, the westerlies-monsoon transition domain (Yellow and Yangtze basins) will have a population decline from the present to the near future under both SSP245 and SSP585. Considering the total river runoff changes from the present to the near future at different climate domains (increase for the monsoon domain and the transition domain, but decline for the westerlies domain; Fig. 3), the APWS shows slight increases for the monsoon domain and the transition domain but a decline for the westerlies domain. In particular, with the highest growth rates in population, the arid westerlies domain where the downstream regions are densely populated and heavily irrigated and thereby highly dependent on mountain runoffs, has a sharp decline of APWS from above 2400 m3 per person yr−1 to below the chronic water scarcity level (1000 m3 per person yr−1) from the past (1960‒1970) to the near future (2030‒2050) under both SSP245 and SSP585 (Fig. 4a). The monsoon domain is projected to have similar problem, since the APWS from the mountains will drop from above 1000 m3 per person yr−1 in the past (1960–1970) to approaching 500 m3 per person yr−1 in the near future (Fig. 4b).

(a−c) show the population and annual per-capita water supply for the mountain basins in each climate domain and their dependent downstream. Here, d shows the mountain-outlet basins (dark color) and their downstream dependent regions (plains that are hydrologically connected with upper mountains; light color; see Methods) for the major rivers originating in the TP.

Discussion

Here, we show that contrary to what one might expect, the future runoff changes in the TP have not shown a uniform increase as precipitation. In the monsoon-dominated river basins (Brahmaputra, Ganges, Mekong, and Salween), the total river runoff is projected to increase significantly. The increasing precipitation will provide more water sources by 2100, although there are also other factors, such as increasing evapotranspiration loss and declining glacier meltwater; the overall effect is a significant increase in future river runoff in the monsoon domain. In the westerlies-dominated river basins (Amu Darya, Syr Darya, Indus, Tarim, Heihe, and Shule), the total runoff will not increase significantly following the future precipitation increase. This is not surprising given the continuous decrease in glacier meltwater (which is an important source of water in this area), while the increased precipitation projected for the future (much lower increasing rates than that in the monsoon domain) will be largely offset by the increased evapotranspiration loss.

This finding challenges the viewpoints of existing studies. Many previous studies had projected that future runoff in the TP region would consistently and significantly increase across all rivers due to the projected increase in precipitation. However, this new research emphasizes that the future runoff changes are much more complex. The continuous decrease in glacier meltwater, which is an important water source in the region, cannot be ignored. As glaciers continue to retreat, their contribution to runoff will gradually decrease, offsetting part of the impact of increased precipitation. Meanwhile, the enhanced evapotranspiration should be well accounted for in the projection of future river runoff.

For long-term freshwater dynamics between 1960 and 2100, mountain runoff in the TP exhibits contrasting temporal patterns: it first increases then decreases in the westerlies domain, and first decreases then increases in the monsoon domain. Crucially, however, per-capita water supply—encompassing both mountain basins and their downstream dependent regions—declines sharply in both domains between the historical period (1960–1970) and the near future (2030–2050). This decline is directly driven by a nearly threefold population growth, overriding the divergent runoff trends across sub-domains.

These complex shifts in high-mountain runoff and per-capita freshwater availability carry broad, cascading implications, starting with water resource management. Traditional supply models for the region are founded on the assumption of consistent runoff increases, but our findings indicate these models now require urgent re-evaluation—especially for downstream regions dependent on TP mountain freshwater, including central Asia’s westerlies-dominated basins (e.g., Tarim, Syr Darya, Amu Darya) and monsoon-influenced downstream areas. With rapid population growth and cropland expansion projected by 2030–2050, irrigation water demand will surge as a critical pressure point: in the monsoon domain, substantial runoff increases may partially alleviate strain but will be offset by expanded agricultural water needs, while the westerlies domain’s non-significant runoff decline, paired with similar demographic and cropland pressures, will amplify irrigation vulnerability in arid downstream areas. To address these challenges, regions must transition to more flexible, adaptive integrated water management strategies, including scaled-up water conservation, expanded storage infrastructure, targeted revisions to agricultural and industrial water-use patterns, promotion of water-saving irrigation technologies, and optimized cropping/land-use strategies aligned with runoff dynamics. Beyond water management and irrigation security, altered runoff regimes will also profoundly disrupt regional ecosystems: many riparian ecosystems in the TP have co-evolved with historical runoff patterns, and significant future shifts in water availability risk destabilizing this balance, threatening specialized flora and fauna—for instance, wetland ecosystems reliant on stable supplies may contract or vanish, triggering localized biodiversity loss. Collectively, these measures are imperative to reconcile rising water demands (including irrigation), safeguard ecological integrity, and advance Sustainable Development Goals in the TP and its downstream regions.

These TP-specific hydrological changes further hold relevance for global climate change research. As a region with uniquely sensitive climatic and hydrological systems, unraveling the interactions between climate warming, glacial melt, and river runoff here provides key insights into broader global climate-hydrological feedback mechanisms. Building on this, future work should prioritize three core goals: clarifying the TP’s complex hydrological processes (snow hydrology, glacial mass balance, permafrost degradation and their interactions with vegetation and runoff dynamics) constrained by large-scale satellite observations (e.g., MODIS cloud-free snow and Randolph Glacier Inventory 6.0 combined product24), improving the accuracy of runoff projections, and delivering actionable scientific support for sustainable development—both within the TP and in its downstream areas. To achieve these goals, we should not only understand the background large-scale climate regimes (the westerlies and the Indian summer monsoon), but also investigate the regulatory effects of interannual-to-decadal ocean-atmosphere coupled oscillations (e.g., El Niño–Southern Oscillation and Indian Ocean Dipole20,25) on the westerlies and Indian summer monsoon precipitation over the TP, thereby improving our understanding of the occurrence patterns of regional freshwater variability and extreme hydrological events (e.g., droughts and floods).

Methods

Historical mountain-outlet runoff

For the 12 studied TP rivers, both in-situ observations (10 rivers) and cryosphere‒hydrology model simulations (2 rivers with large anthropogenic impacts) were used to study the long-term (1960‒2016) changes in mountain-outlet (where rivers leave the mountains and enter the plains) runoff for the westerlies domain (Tarim, Shule, Heihe, Amu Darya, Syr Darya, and Indus rivers), Indian monsoon domain (Brahmaputra, Ganges, Mekong, and Salween rivers), and westerlies‒monsoon transition domain (Yangtze and Yellow rivers) of the TP during the period 1960‒2016, as summarized below.

We obtained records of annual mountain-outlet runoff (see Supplementary Table 1 for discharge gauges) during 1960‒2016 for the major rivers of the TP to allow for a coherent, regional perspective of heterogeneous runoff changes across the region. All the discharge observations that we used in this study have been strictly quality-controlled by the corresponding water resources authorities. Annual runoff observations of the Yellow, Yangtze, Tarim (counting three major tributaries of the Yarkant, Hotan, and Akesu), Heihe, and Shule rivers were available from the Ministry of Water Resources in China (MWRC). These records can be accessed from the hard copy of the Chinese Hydrological Data Yearbook, that can be found in the National Library of China. The annual runoff records of the upper Brahmaputra (in China) were also obtained from MWRC, while the records of the upper Ganges (available from two major tributaries, the Karnali and Gandaki, during 1963‒2015) were obtained from the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology in Nepal (DHM; http://dhm.gov.np). The records for the upper Indus were obtained from the Pakistan Water & Power Development Authority (WAPDA; https://www.wapda.gov.pk) and were available for 1962‒2016. The mountain-outlet runoffs for both the Mekong and the Salween rivers were derived with a linear statistical method using the monthly CMA (China Meteorological Administration) precipitation and monthly discharge data at adjacent up- and downstream gauges from MWRC (Jiayuqiao and Daojieba gauges for the Salween, and Changdu and Jiuzhou gauges for the Mekong), and assuming the same runoff coefficients (i.e., runoff divided by area-averaged precipitation) at nearby gauges in the same river. This is because, at these two narrow and steep rivers, the correlation coefficients between up- and downstream monthly runoff records were very high (r > 0.96). Here, the mountain-outlet gauges at the Salween and Mekong rivers are selected at an altitude of about 2500 m, so that the upper basins may include most of the mountain area.

For the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers in central Asia, which have marked anthropogenic impacts, the time series of natural runoffs at mountain outlets cannot be obtained by direct in-situ observations. Natural runoffs for these two rivers are carefully reconstructed by using the well-verified cryospheric‒hydrological modeling against upstream gauge observations (VIC-glacier model, designed to capture glacier-hydrology processes; Huang et al. for Sys Darya26; Hou et al. for Amu Darya27). Further, the glacier change simulations in these cryosphere-hydrology modeling have been constrained with the Randolph Glacier Inventory (RGI) data of the 1970s and 2000s28. The volume-area scaling approach was used to update the calculated glacier area and volume in the model every year.

Glacier mass changes in the 21st century

The future glacier mass balance dataset in the TP is obtained from Rounce et al.29, which provides the reasonable projections of glacier mass change for 22 General Circulation Models (GCMs) and four Representative Concentration Pathways till the end of the 21st century (2000‒2100). Rounce et al. use a new dataset of geodetic mass balance observations of almost all glaciers in the TP region to calibrate the Python Glacier Evolution Model (PyGEM) using Bayesian inference29. The new dataset enables the model to capture spatial variations in mass balance, and the Bayesian inference enables the uncertainty associated with the model parameters to be quantified. Validation with historical mass balance observations shows the model performs well and the uncertainty is well captured.

Future climate projections

The future corrected and downscaled precipitation and air temperature datasets (with 0.5° spatial resolution) are from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project 3b (ISIMIP3b)30,31, including the outputs from five GCMs (including GFDL-ESM4, IPSL-CM6A-LR, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, MRI-ESM2-0, and UKESM1-0-LL) in Phase 6 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) under two shared socio-economic pathway scenarios (SSP) (the high-emission scenario of SSP585 and the moderate emission scenario of SSP245). Furthermore, we employ the delta method (calculating differences for air temperature and ratios for precipitation32) to further correct the future climate data (precipitation and air temperature) from individual GCM of ISIMIP3b based on the ERA5-Land historical (2001–2015) reference data33. For all the future climate analyses and model projections in this study, we use these corrected ISIMIP3b precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 1) and air temperatures.

Mountain basins & Hydrologically-dependent downstream area

In this study, at first, we select the mountain-outlet stations for all the 12 studied rivers in the TP, with the criteria of covering most of the mountain runoff in each basin, which are either at existing mountain discharge gauges or at a river cross-section around an altitude of 2500 m. Once the mountain-outlet stations are defined, the mountain-outlet basins can be delineated for the 12 TP rivers following Lehner et al.34.

For each mountain-outlet basin in the TP, we also define the downstream area (Fig. 4d) that directly depends on the mountain-outlet basin using the river sub-basin delineation34. The dependent downstream area is smaller than the total downstream area because not every downstream sub-basin is hydrologically connected to the mountain-outlet basin. We start at the mountain-outlet basin and iteratively select each connected downstream sub-basin until the estuary, or the lowest sub-basin in case of an endorheic system, is reached2.

Normalized discharge

Due to the runoff data policy of riparian countries, the monthly time-series runoffs are normalized (Supplementary Fig. 2) by using the following equation.

Where, \({Q}_{{orig}}\) and \({Q}_{{n\_mon}}\) are the original and normalized monthly runoffs, respectively; \({Q}_{\max }\) and \({Q}_{\min }\) are the maximum and minimum values of the monthly runoff time-series, respectively.

Excess discharge of glaciers

The excess discharge is zero for glaciers with balanced or positive mass budget35. The annual excess discharge of glaciers can be calculated as the sum of the absolute values of the monthly negative mass changes of glaciers.

Linear trend estimation

The linear trend was estimated using the least-squares method, and its statistical significance was tested using the Student’s t-test. When the significant values are greater than or equal to the 95% confidence level (p <0.05), the estimated trend is significant. Further, “p <0.01” indicates a very significant trend; “p <0.001” indicates an extremely significant trend, while “p >0.05” indicates no significant trend.

Deep learning model: long short-term memory

In recent years, deep learning has been widely applied to ungauged or poorly gauged mountain regions to simulate glacier mass change36, ET37, and river runoff38, showing extremely high efficiency and unprecedented accuracy.

The long short-term memory (LSTM) is a specific deep learning model that addresses the issue of long-term dependency modeling in sequential data39. The LSTM uses specialized memory units and gate mechanisms to more effectively capture and store long-term dependency information in time series data, making it highly proficient in various sequence modeling tasks. Comparing to other types of recurrent neural networks, the LSTM avoids exploding and/or vanishing gradients, which makes it capable of learning long-term dependencies between input and output features38. It is quite suitable for modeling mountain river basin processes like glacier and snow accumulation/melting that have longer time-scales, comparing to input-driven processes like instant surface runoff.

Compared with traditional process-based physical methods, the LSTM is more flexible to simulate runoff, ET, and glacier mass change in areas with insufficient observed data, such as the TP.

Evaluation criterion for LSTM simulation

The Nash–Sutcliffe model efficiency coefficient (NSE)40, the percent bias (Pbias), or the root mean squared error (RMSE) are used to evaluate the LSTM’s performance in simulating the monthly runoff, ET, or glacier mass change (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 5).

Where the NSE is defined as below.

Where \({Q}_{{oi}}\) is observation/reference, \({Q}_{{si}}\) is simulation, n is the total number of time-series for comparison, and \(\bar{{Q}_{o}}\) is the mean value of the observations over the simulation period. The higher the NSE is, the better the model performs. A perfect fit should have an NSE value equal to one.

The Pbias is defined as below.

Training of LSTM for accurate runoff simulation

To improve the future runoff projections, we have performed a rigorous training and validation, as well as testing of the LSTM model during 2001–2016 (2001–2012 for training and validation; and 2013–2015 for testing) against the reference monthly runoff, in each of the 12 TP basins (Supplementary Fig. 2). During the training and validation as well as testing period, the LSTM model input data includes both the monthly changes in climate (the ERA5-Land precipitation and air temperature) and glacier mass balance at each basin29.

For the 12 TP basins, the monthly reference runoff data are mostly ground-based observations except for the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers that are reconstructed by well-verified cryosphere-hydrology models (see Datasets). Results show that the LSTM model can well reproduce the intra- and inter-annual runoff changes, not only in the training-validation period but also in the testing period, with the NSE greater than 0.7 and the Pbias less than 10% at most of the 12 studied basins.

Future runoff projection

With the verified LSTM models for runoff simulations, the projections of future runoff trends have been performed at individual TP basins, by considering both the future changes in climate (the corrected ISIMIP3b precipitation and air temperature; see Datasets) and glacier mass balance at a monthly time scale29. Based on the above results at individual basins (Supplementary Fig. 3), we calculate the future runoff projections in the mountain basins at the TP’s different climate domains (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Training of LSTM for accurate ET simulation

To understand the driving forces behind the future runoff changes, we also project the future ET trends with the LSTM model. We have done a rigorous training and validation (during 2001–2012), as well as testing (during 2013–2015) of the LSTM model for ET simulations in each of the 12 TP basins (Supplementary Fig. 5), against the ERA5-Land monthly ET. During 2001–2015, the LSTM model input data includes the monthly ERA5-Land precipitation and air temperature at each basin. Results show that the LSTM model can reproduce the intra- and inter-annual ET changes very well, in both the training-validation and testing periods, with the NSE greater than 0.95 and the Pbias less than 5% at most of the 12 TP basins.

Future ET projection

With the verified LSTM models for ET simulations, the projections of future ET trends are performed at individual mountain basins by considering both the future changes in precipitation and air temperature at a monthly time scale (the corrected ISIMIP3b precipitation and air temperature; see Datasets). Based on the above results at individual basins (Supplementary Fig. 6), we calculate the future ET projections in the mountain basins at the TP’s different climate domains (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Data availability

The glacier datasets are available at https://www.glims.org/RGI. The ISIMIP3b data are available at https://data.isimip.org/. The historical and future population data are available at https://doi.org/10.7927/q7z9-9r69. Runoff observations are available from the hard copy of Chinese Hydrological Data Yearbook (that can be found National Library of China), Department of Hydrology and Meteorology in Nepal (DHM; http://dhm.gov.np), Pakistan Water & Power Development Authority (WAPDA; https://www.wapda.gov.pk), the Scientific-Information Center of the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination in Central Asia (http://isepei.org/organization/sic-icwc), as well as the Global Runoff Data Center (https://grdc.bafg.de).

References

Yao, T. et al. Recent Third Pole’s rapid warming accompanies cryospheric melt and water cycle intensification and interactions between monsoon and environment: multidisciplinary approach with observations, modeling, and analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 423–444 (2019).

Immerzeel, W. W. et al. Importance and vulnerability of the world’s water towers. Nature 577, 364–369 (2020).

Pritchard, H. D. Asia’s shrinking glaciers protect large populations from drought stress. Nature 569, 649–654 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. TP-River: monitoring and quantifying total river runoff from the third pole. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 102, E948–E965 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. Permafrost thawing puts the frozen carbon at risk over the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz3513 (2020).

Li, D. et al. Exceptional increases in fluvial sediment fluxes in a warmer and wetter High Mountain Asia. Science 374, 599–603 (2021).

Yao, T. et al. The imbalance of the Asian water tower. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 618–632 (2022).

Pepin, N. et al. Elevation-dependent warming in mountain regions of the world. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 424–430 (2015).

Bhattacharya, A. et al. High Mountain Asian glacier response to climate revealed by multi-temporal satellite observations since the 1960s. Nat. Commun. 12, 4133 (2021).

Khanal, S. et al. Variable 21st century climate change response for rivers in high mountain Asia at seasonal to decadal time scales. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR029266 (2021).

Cui, T. et al. Non-monotonic changes in Asian Water Towers’ streamflow at increasing warming levels. Nat. Commun. 14, 1176 (2023).

Long, J. et al. Hydrological projections in the third pole using artificial intelligence and an observation-constrained cryosphere-hydrology model. Earth’s. Future 12, e2023EF004222 (2024).

Lutz, A. F., Immerzeel, W. W., Shrestha, A. B. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Consistent increase in High Asia’s runoff due to increasing glacier melt and precipitation. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 587–592 (2014).

Su, F. et al. Hydrological response to future climate changes for the major upstream river basins in the Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Planet. Change 136, 82–95 (2016).

Zhao, Q. et al. Projecting climate change impacts on hydrological processes on the Tibetan Plateau with model calibration against the glacier inventory data and observed streamflow. J. Hydrol. 573, 60–81 (2019).

Qi, W. et al. Divergent and changing importance of glaciers and snow as natural water reservoirs in the eastern and southern Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2021JD035888 (2022).

Jiang, J. et al. Precipitation regime changes in High Mountain Asia driven by cleaner air. Nature 623, 544–549 (2023).

Su, F. et al. Contrasting fate of Western Third Pole’s water resources under 21st century climate change. Earth’s. Future 10, e2022EF002776 (2022).

Hassan, M. et al. Projected climate regime over Pakistan and its implications for hydrology in the Hunza River Basin using CMIP6 GCMs. Clim. Dyn. 63, 285 (2025).

Latif, Y. & Palus, M. Causal information flow and information transfer delay from ENSO and IOD to precipitation variability in the Upper Indus Basin, Pakistan. EGU Gen. Assem. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu24-12884 (2024).

CIESIN (Center for International Earth Science Information Network, C. U. Global Population Count Grid Time Series Estimates https://doi.org/10.7927/H4CC0XNV (2017).

Gao, J. Downscaling Global Spatial Population Projections from 1/8-Degree to 1-km Grid Cells. 1105 (National Center for Atmospheric Research, 2017).

Jones, B., B. C. O'Neill & Gao, J. Global 1-km downscaled population base year and projection grids based on the shared socioeconomic pathways, revision 01. NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC) https://doi.org/10.7927/Q7Z9-9R69 (2020).

Muhammad, S. & Thapa, A. Daily Terra–Aqua MODIS cloud-free snow and Randolph Glacier Inventory 6.0 combined product (M*D10A1GL06) for high-mountain Asia between 2002 and 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 767–776 (2021).

Latif, Y., Fan, K., Wang, G. & Paluš, M. Cross-scale causal information flow from the El Niño–Southern Oscillation to precipitation in eastern China. Earth Syst. Dynam. 15, 1509–1526 (2024).

Huang, J., Su, F., Yao, T. & Sun, H. Runoff regime, change, and attribution in the upper Syr Darya and Amu Darya, Central Asia. J. Hydrometeorol. 23, 1563–1585 (2022).

Hou, M. et al. Streamflow composition and the contradicting impacts of anthropogenic activities and climatic change on streamflow in the Amu Darya Basin, Central Asia. J. Hydrometeorol. 24, 185–201 (2023).

Consortium, R. Randolph glacier inventory—a dataset of global glacier outlines, version 6 https://doi.org/10.7265/4m1f-gd79 (2017).

Rounce, D. R., Hock, R. & Shean, D. E. Glacier Mass Change in high mountain Asia through 2100 using the open-source Python glacier evolution model (PyGEM). Front. Earth Sci. 7:331 https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2019.00331 (2020).

Warszawski, L. et al. The inter-sectoral impact model intercomparison project (ISI–MIP): project framework. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3228–3232 (2014).

Lange, S. & Büchner, M. ISIMIP3b bias-adjusted atmospheric climate input data (v1. 1). ISIMIP Repos. https://doi.org/10.48364/ISIMIP.842396.1 (2021).

Hay, L. E., Wilby, R. L. & Leavesley, G. H. A comparison of delta change and downscaled gcm scenarios for three mountainous basins in the United States. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 36, 387–397 (2000).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Lehner, B., Verdin, K. & Jarvis, A. New global hydrography derived from spaceborne elevation data. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 89, 93–94 (2008).

Brun, F., Berthier, E., Wagnon, P., Kääb, A. & Treichler, D. A spatially resolved estimate of High Mountain Asia glacier mass balances from 2000 to 2016. Nat. Geosci. 10, 668–673 (2017).

Bolibar, J. et al. Deep learning applied to glacier evolution modelling. Cryosphere 14, 565–584 (2020).

Wang, X., Gao, B. & Wang, X.-S. Investigating the ability of deep learning on actual evapotranspiration estimation in the scarcely observed region. J. Hydrol. 607, 127506 (2022).

Kratzert, F. et al. Toward improved predictions in ungauged basins: exploiting the power of machine learning. Water Resour. Res. 55, 11344–11354 (2019).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Nash, J. E. & Sutcliffe, J. V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—a discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 10, 282–290 (1970).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (2024QZKK0400), the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFF0808602), and Tsinghua University (100008001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W. designed the study and drafted the manuscript. L.W. and J.L. performed the data analysis. D.C., N.L., X.L., and T.Y. reviewed and contributed to the final form of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author L.W. is Associate Editor and D.C. is Editorial Board Member of npj Climate and Atmospheric Science. Both L.W. and D.C. were not involved in the journal’s review of, or decisions related to, this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Long, J., Chen, D. et al. Divergent mountain runoff dynamics but declining per capita freshwater availability across the Third Pole by mid-21st century. npj Clim Atmos Sci 9, 40 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01313-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01313-4