Abstract

Radiomics offers a noninvasive avenue for predicting clinicopathological factors. However, thorough investigations into a robust breast cancer outcome-predicting model and its biological significance remain limited. This study develops a robust radiomic model for prognosis prediction, and further excavates its biological foundation and transferring prediction performance. We retrospectively collected preoperative dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI data from three distinct breast cancer patient cohorts. In FUSCC cohort (n = 466), Lasso was used to select features correlated with patient prognosis and multivariate Cox regression was utilized to integrate these features and build the radiomic risk model, while multiomic analysis was conducted to investigate the model’s biological implications. DUKE cohort (n = 619) and I-SPY1 cohort (n = 128) were used to test the performance of the radiomic signature in outcome prediction. A thirteen-feature radiomic signature was identified in the FUSCC cohort training set and validated in the FUSCC cohort testing set, DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort for predicting relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) (RFS: p = 0.013, p = 0.024 and p = 0.035; OS: p = 0.036, p = 0.005 and p = 0.027 in the three cohorts). Multiomic analysis uncovered metabolic dysregulation underlying the radiomic signature (ATP metabolic process: NES = 1.84, p-adjust = 0.02; cholesterol biosynthesis: NES = 1.79, p-adjust = 0.01). Regarding the therapeutic implications, the radiomic signature exhibited value when combining clinical factors for predicting the pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (DUKE cohort, AUC = 0.72; I-SPY1 cohort, AUC = 0.73). In conclusion, our study identified a breast cancer outcome-predicting radiomic signature in a multicenter radio-multiomic study, along with its correlations with multiomic features in prognostic risk assessment, laying the groundwork for future prospective clinical trials in personalized risk stratification and precision therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer and the major cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide1, imposing a significant public health burden2. In recent decades, heterogeneous subtypes of breast cancer (i.e., Luminal, HER2-enriched and triple-negative breast cancer [TNBC]) were discovered and distinct treatment strategies were administered to these patients. Luminal and HER2-enriched breast cancers were sensitive to endocrine therapy and anti-HER2 targeted therapy, respectively, while chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy might be the optimized therapy option for TNBC patients. Moreover, neoadjuvant therapy, referring to preoperative therapies for early stage or locoregional advanced breast cancer, has been playing an increasing role in treatment of breast cancer. Overall, subtyping-based therapy has led to significantly improved treatment efficacy and patient survival3. However, the complex heterogeneity of breast cancer often results in diverse prognoses and instances of relapse4. Due to the heterogeneity among breast cancer patients, there is a need for more clinically accessible and convenient methods to differentiate patient prognosis. This is essential to guide patient treatment decisions, including intensified treatment for tumors with high recurrence risk and de-escalation of treatment for tumors with low recurrence risk.

Radiomics, utilizing high-throughput quantitative imaging features, provides valuable insights into the intrinsic properties of tumors with a non-invasive method. Despite the current exceptional predictive performance of deep learning radiomics, our study prefers radiomics for its standardized and reproducible feature extraction process5. Recent studies have demonstrated the crucial role of dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI)-based radiomics in non-invasively revealing breast tumor heterogeneity and predicting clinical outcomes6,7,8,9, thereby enhancing evidence-based decision-making at the point of diagnosis. A recent study collected DCE-MRIs from early-stage breast cancer patients to develop a radiomic signature for prognosis prediction. This radiomic signature achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.73 for 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) in the internal validation set10. In addition, a study reported imaging heterogeneity phenotypes of breast cancer and its prognostic value were uncovered. Combined clinical and imaging heterogeneity phenotype model resulted in C-index of 0.73 in 10-year relapse-free survival (RFS) prediction11. However, previous radiomic studies were generally based on single-center or small-scale cohorts, which constrains their reliability in varied clinical contexts. Moreover, the limitations in the interpretability and generalizability of radiomics serve as major barriers to its full integration into clinical practice.

In terms of interpretability in radiomics, a major limitation is the complexity of explaining radiomic features. On one hand, previous studies have focused on the interpretability of the inherent mathematical properties of the features, such as grey levels and entropy12,13. On the other hand, with the advancement of multiomic analysis, the biological mechanism of radiomic features are increasingly being revealed14. For instance, previous study correlated a peritumoral radiomic feature with tumor immune suppression and metabolic dysregulation in TNBC14. Furthermore, image heterogeneity-related radiomic features were associated with malignant behaviors and tumor ferroptosis15. Although the integration of radiomics with multiomics provides detailed insights into radiomic features, the biological foundation of radiomic features in prognosis prediction remains enigmatic.

In terms of generalizability in radiomics, previous radiomic studies in clinical outcome prediction have predominantly concentrated on either prognostic prediction16 or treatment response6,17 in isolation, lacking research that simultaneously addresses both aspects. However, this may lead to an incomplete exploration of the potential clinical value of radiomic features. Inspired by transfer learning18,19, the integration of established prognostic radiomic features with clinical data to develop a predictive model for neoadjuvant therapy efficacy offers a promising avenue to comprehensively reveal the clinical value of radiomic features.

Overall, our aim is to develop a robust and interpretable DCE-MRI-based radiomic model for predicting breast cancer outcomes. Specifically, the objectives include establishing a prognostic radiomic model based on a multi-center dataset, elucidating the biological underpinnings of high and low radiomic-risk group through multiomic analyses, and further exploring its transferability in predicting responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This study will make significant contributions to the interpretability and generalizability of radiomics, paving the way for precision treatment of breast cancer.

Results

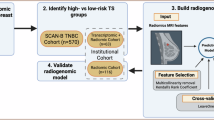

Our research is structured into three key steps. First, we developed a breast cancer prognosis prediction model based on a robust radiomic signature. Next, we delve into its biological foundation through multiomic data analysis. Finally, we transferred this signature, in conjunction with clinical factors, to predict neoadjuvant chemotherapy efficacy in breast cancer.

Patient characteristics and clinical outcomes

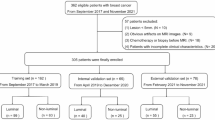

To achieve our research goal, three cohorts were collected to establish a large radiomic dataset with matched outcome, multiomic and treatment response information. The Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FUSCC) cohort included breast cancer participants treated at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center from Jan 2013 to Dec 2014. The DUKE cohort included participants from the Duke University dataset, and the I-SPY1 cohort included participants from I-SPY1 dataset. We defined three types of datasets: radiomic-outcome, radio-multiomic and radiomic-treatment datasets. Radio-multiomic and radiomic-treatment datasets were subsets of radio-outcome datasets. First, 584, 922, and 222 patients were initially enrolled into three cohorts, respectively. Second, after the exclusion criteria exhibited in Fig. 1, the remaining 466, 619, and 128 patients with both radiomic and clinical follow-up data constituted the radio-outcome datasets in FUSCC cohort, DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort, respectively. Subsequently, in radiomic-outcome dataset of FUSCC cohort, patients who did not undergo multiomics sequencing were excluded and the remaining 420 patients comprised the radio-multiomic dataset. Lastly, in radiomic-outcome dataset of DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort, patients who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy were excluded and the remaining 217 and 125 patients comprised the radiomic-treatment dataset, respectively (Fig. 1).

This study includes three cohort, FUSCC cohort, Duke cohort and I-SPY1 cohort Exclusion criteria were presented in this illustration. Samples with radiomic and clinical follow-up data were incorporated in the radiomic-outcome dataset, in which samples with multiomic data and treatment information comprised the radiomic-multiomic dataset and radiomic-treatment dataset, respectively. DCE-MRI dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 1 illustrates the explicit clinical characteristics of the study participants, including age, menopause status, histological type, pathological grade, T and N stage, receptor status, therapeutic information and outcome. The median follow-up for the FUSCC cohort was 81.1 months (range, 0.39–114.2 months); 68 recurrences and 36 deaths were recorded. The median follow-up for the DUKE cohort was 47.1 months (range, 0–112.1 months); 57 recurrences and 31 deaths were recorded. The median follow-up for the I-SPY1 cohort was 46.8 months (range, 6–84 months); 32 recurrences and 21 deaths were recorded. In summary, we have developed a large multicenter radio-multiomic dataset, which promoted further research on breast cancer outcome prediction and biological mechanisms.

Radiomic model predicts prognosis

The study overview is represented in Fig. 2. The prognostic predictive radiomic signature was developed based on the FUSCC cohort training set (n = 305) and independently validated with the FUSCC cohort testing set (n = 161), DUKE cohort (n = 619) and I-SPY1 cohort (n = 128). In the FUSCC cohort training set, we used Lasso-Cox regression to select significant radiomic features most related to patient prognosis and then those features were incorporated into a multivariable Cox proportion hazards regression to build the outcome prediction model for breast cancer patients. After the L1-penalized feature selection process, 13 features remained (Table 2). The radiomic signature was constructed using multivariate Cox regression, and the risk score was calculated as follows:

In the first phase, we extracted radiomic features from three ROIs (i.e., tumor, peri-tumor and tumor-peritumor). In the second phase, we selected candidate features to construct prognosis prediction radiomic signatures and differentiated breast cancer patients into high and low radiomic risk groups. Specifically, Lasso-Cox was applied to select significant radiomic features most related to patient prognosis and then those features were incorporated into a multivariable Cox proportion hazards regression to build the outcome prediction model for breast cancer patients. The radiomic risk score was obtained by a linear weighted sum obtained in the model training process. Patients were allocated into high- and low-risk group according to the median risk score in the training set as threshold. In the third phase, we delved into the biological characteristics of distinct radiomic risk groups. In the fourth phase, we investigated the therapy response prediction value of our radiomic risk signature based on the concept of transfer learning. ROI region of interest.

The median risk score value of 1.34 was defined as the cutoff of the high-risk (risk score at least 1.34) and low-risk groups (risk score less than 1.34). Clinical characteristics and examples of cases from the high- and low-radiomic-risk groups are shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 3. In the FUSCC cohort testing set, the C-index was 0.65 [95% confidence intervals (CIs): 0.51–0.78, standard deviation (sd) = 0.07] and the 3-year Brier score was 0.09 (Supplementary Table 2). Patients with predicted high risk exhibited worse prognosis in relapse-free survival (RFS) (log rank p = 0.013, Fig. 4A); the radiomic risk score independently correlated with prognosis after adjusting for clinical variables (Table 3). In the DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort, the C indices were 0.61 (95%CI: 0.54–0.69, sd = 0.04) and 0.67 (95%CI: 0.57–0.76, sd = 0.05), and the 3-year Brier scores were 0.08 and 0.16 (Supplementary Table 2), respectively; radiomic high-risk patients had a worse prognosis (DUKE cohort, p = 0.024; I-SPY1 cohort, p = 0.035, Fig. 4B, C). Additionally, the risk level revealed by the radiomic signature was used to distinguish distinct overall survival (OS) in the three cohorts (FUSCC cohort, p = 0.036; DUKE cohort, p = 0.005; I-SPY1 cohort, p = 0.027, Fig. 4D–F, Supplementary Table 3). In summary, we developed and validated a robust prognosis predictive radiomic model in multicenter radiomic-outcome datasets.

Patient 1 to 4 are assessed as high recurrence risk and patients 5 to 8 as low recurrence risk by our radiomic risk model. The tumors in patients with high radiomic-risk appeared irregular and “aggressive” while the tumors in patients with low radiomic-risk risk appeared regular and “inert” exhibited on DCE-MRI. The tumor contour was delineated. TNBC triple-negative breast cancer, RS risk score.

A–F Kaplan-Meier (KM) plot in internal and external validation cohort. KM plot of recurrence-free survival (RFS) in the FUSCC testing cohort A, DUKE cohort B and I-SPY1 cohort C and overall survival (OS) in the FUSCC cohort testing cohort D, DUKE cohort E and I-SPY1 cohort F. Patients are stratified according to recurrence risk level based on radiomic prediction model built in the FUSCC cohort training set.

Multiomic analysis of the biological differences according to the radiomic signature

The radiomic signature was comprised of 13 radiomic features, which are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1. Except for features t_e21_wavelet_HHL_ClusterShade (f1) and t_e20_wavelet_HHL_Mean (f2), which did not exhibit a linear correlation with the radiomic risk score, the radiomic features based on wavelet transformation of Energy and Dependence Entropy (f3, f4, f5 and f11) were positively correlated with the radiomic risk score, while other variables were negatively correlated (Supplementary Fig. 1). Considering the weighting factors in the risk score calculation, the feature p_vari_wavelet_LHH_SRLGLE (f10) had the largest weight, indicating the importance of textural features based on the variance of ShortRunLowGrayLevelEmphasis derived from wavelet transformation in the peritumoral area, which reflects the heterogeneity and blood perfusion characteristics of the peritumoral environment. Notably, peritumoral features accounted for most of the signature, indicating the essential role that peritumoral imaging plays in patient prognosis stratification (Table 2).

Furthermore, our study delves into the biological foundation of the developed radiomic signature through comprehensive multiomic analysis (Fig. 5A). We first compared the somatic mutations between the high- and low-risk groups. The gene mutations were in equilibrium across different radiomic-risk level tumors (Supplementary Fig. 2). Then, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to explore the enriched pathways in high- and low-radiomic-risk tumors and found that multiple pathways involving mitochondrial respiratory and energy metabolism were enriched in tumors from high-radiomic-risk patients, including ATP metabolic process (NES = 1.84, p-adjust = 0.02), cholesterol biosynthesis (NES = 1.79, p-adjust = 0.01) and electron transport chain (NES = 1.76, p-adjust = 0.04) (Fig. 5B). PI3K signaling (NES = 2.10, p-adjust < 0.001) and transforming growth factor pathways (NES = 1.98, p-adjust < 0.001) were upregulated in low-radiomic-risk tumors (Fig. 5C). In terms of metabolomics, the differential abundance of metabolites indicated that lipid metabolism (glycerophospholipid metabolism, DA = 0.17) and glycan biosynthesis (glycosphingolipid biosynthesis-ganglio series, DA = 0.50) were upregulated in high-radiomic-risk patients (Fig. 5D). These results indicated distinct biological characteristics of high- and low-risk tumors differentiated by radiomic signature, wherein high-risk tumors were highly proliferative and energy-consuming and low-risk tumors were lacked explicit characteristics, with classic breast cancer hallmark pathway upregulation.

A Schema of the radio-multiomic analysis. B, C Transcriptomic analysis reveals top 20 upregulated pathways in tumors from high B and low C radiomic risk group. D Differential abundance score from metabolomic analysis reveals the overall alterations in tumor metabolic pathways between high and low radiomic risk groups.

Radiomic signature as a transfer model to predict treatment response

From the above investigation, we speculated that high-radiomic-risk tumors were proliferative and potentially sensitive to chemotherapy. Thus, we questioned whether the developed radiomic risk signature could transfer to predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). In radiomic-treatment datasets from the DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort, radiomic risk score was calculated as radiomic model. Receptors statuses (i.e., ER, PR, and HER2) were determined as clinical variables associated with therapeutic response by univariate logistic regression and was established as clinical model by multivariate logistic regression. Additionally, radiomic risk score and clinical variables were integrated to build radiomic-clinical model. For pathological complete response (pCR) prediction, the radiomic model and clinical model performed moderately (radiomic model, AUC 0.59 (95%CI: 0.50–0.68); clinical model, AUC 0.68 (95% CI: 0.60–0.76), Fig. 6A). When the radiomic risk score and clinical variables were combined, the AUCs increased to 0.72 (95% CI: 0.64–0.79 permutation test p < 0.001) and 0.73 (95%CI: 0.63–0.83, permutation test p < 0.001) in the DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort, respectively (Fig. 6A). For response prediction, the AUC of a single clinical model was 0.69 (95%CI: 0.60–0.77) and the performance of the combined model exhibited an AUC of 0.74 (95%CI: 0.67–0.81, permutation test p < 0.001) (Fig. 6B). In conclusion, radiomic signature for prognosis prediction showed complementary value of clinical variables in predicting therapy response.

A, B Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. ROC curve of predictive model using radiomic risk signature, clinical features and combined signature for pCR A and response prediction B. Rad radiomic model, Clin clinical model, Rad-Clin radiomic-clinical model.

Discussion

Our study aimed to develop a robust and transferable radiomic model for predicting cancer prognosis and to explore its biological basis. By establishing a multicenter breast cancer dataset comprising 1213 participants who underwent preoperative DCE-MRI, we successfully developed and validated a robust radiomic model capable of identifying patients at high risk of recurrence (FUSCC cohort, C-index = 0.65, log-rank p = 0.013; DUKE cohort, C-index = 0.61, p = 0.024; I-SPY1 cohort, C-index = 0.67, p = 0.035). Moreover, we revealed the biological implications of the radiomic signature by analyzing matched multiomic data, while demonstrating the potential of the radiomic signature in predicting treatment response.

Our initial focus was on developing a radiomic signature for relapse-free survival (RFS). This signature, based on thirteen retained radiomic features, proved to be resilient not only in distinguishing RFS but also in predicting overall survival (OS) among diverse breast cancer patient populations from different races and medical centers. Notably, our study broke from the trend of single-center or small-scale cohort reliance in previous radiomic-outcome research11,16. The inclusion of a large multicohort breast cancer dataset significantly augmented the reliability and generalizability of our model.

A distinctive strength of our study lies in the concurrent extraction of tumor, peritumoral, and tumor-peritumoral radiomic features. We revealed that out of the thirteen radiomic features, nine originated from the peritumoral region. Studies have shown the potential of peritumoral radiomic features in predicting lymph node metastasis, treatment efficacy, and risk stratification in non-small cell lung cancer20,21,22 and that peritumoral features were associated with therapy response and prognosis in breast cancer14,23. In alignment with these findings, our study underscored the importance of texture alterations in the tumor invasive margin for predicting breast cancer patient outcomes. Recent radiomic studies have developed habitat imaging features to depict the texture characteristics of subregion images7, representing a promising advancement in decoding imaging patterns, elucidating biological mechanisms, and identifying patient outcomes at a higher resolution.

Radiomic features particularly shape, first-order, and some second-order features are generally easier to interpret than features learned by neural networks. However, higher-order features such as wavelet features could be more challenging to interpret due to their complex mathematical nature. In the present study, the features we really focused on were higher-order radiomic features that were poorly explainable in mathematical terms. We associated these features with omics data to understand their potential relevance to tumor biology. This approach adds another layer of interpretability to radiomic features by linking them to specific tumor biological behaviors, thus enhancing their interpretability from a biological perspective.

Utilizing matched multiomic data, we delved deeper into the biological foundation of the radiomic risk score across high and low risk groups24. High-radiomic-risk tumors exhibited pronounced proliferation and energy consumption, as indicated by heightened mitochondrial respiration and energy metabolism. This is consistent with findings suggesting that more aggressive tumors exhibit elevated mitochondrial activity and produce additional ATP to fuel their rapid growth and division25. Previous studies have established connections between radiomics and cancer biology, linking heterogeneity-related radiomic features to immunosuppression and metabolic dysfunction in breast cancer14, and correlating a prognosis-related radiomic features to immune, proliferation, treatment response, and cellular function pathways in glioblastoma26. We believe that this integrative approach, leveraging multimodal data, is instrumental in advancing our microscopic and macroscopic understanding of tumors, identifying therapeutic targets, and promoting precision medicine6,27.

Recent years have witnessed the advancements of multiomic data integration in tumor prognosis prediction. A work of Sohrab P. Shah’s team demonstrated the predictive power of integrating genomics, radiomics, histopathology, and clinical features for ovarian cancer prognosis28. Moreover, a recent study by our team extended this approach by combining radiomics and histopathological features with transcriptomic RNA expression, protein subtyping, metabolomics data, and clinical staging to achieve precise prognosis prediction in breast cancer29. By incorporating multiple dimensions of information, this integrated approach holds promise for more accurate tumor prognosis prediction. However, it is important to note that obtaining and integrating multimodal data poses challenges due to the complexity and diversity of data sources. Radiomics retains its non-invasive, convenient, and reproducible advantages, making it a valuable tool in future clinical practices. As we move forward, the role of radiomics remains significant in advancing personalized cancer care and prognosis assessment.

Building upon the biological characteristics of high-risk radiomic tumors, we explored the potential of our prognosis-predicting radiomic model in treatment response prediction. Inspired by the concept of transfer learning, our aim was to determine if the model’s application extended to therapy efficacy prediction. We found that while the radiomic risk score moderately predicted neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) response, its combination with molecular status (ER, PR, and HER2) improved efficacy prediction. This is in line with established factors influencing NAC response30. Notably, our results supported the notion that high-risk patients, as identified by the radiomic risk score, exhibited greater NAC benefits19. This finding correlates with prior research suggesting that highly proliferative tumor cells are more responsive to chemotherapy31,32.

Nevertheless, our study has several limitations. Its retrospective nature introduces potential bias, necessitating further prospective research to verify the performance of the prognosis-predicting signature. Additionally, while our radiomic model displayed satisfactory external validation in prognosis prediction, its overall performance has not yet reached the ideal standard, as the C-index is not high enough to meet the criteria for direct clinical application. Finally, while we explored the radiomic risk score’s application in treatment response prediction, the improvement seen in its performance based on the clinical model was not notable enough to guide clinical decisions. Future efforts should incorporate additional empirical radiomic or deep learning radiomic features to address this limitation. Deep learning and habitat imaging features offer promising avenues for enhancing prediction accuracy. Deep learning offers robust capabilities for extracting deep learning features from complex datasets and building predictive models, crucial for accurately assessing tumor characteristics and predicting disease progression and treatment response. Additionally, habitat imaging enables a more precise description and analysis of the complexity within the tumor microenvironment. This method can differentiate and quantify the diverse imaging regions within tumors, thereby enhancing the understanding of intratumoral heterogeneity and facilitating personalized treatment. Moving forward, the integration of these advanced methods has the potential to revolutionize personalized cancer therapy, enhancing both diagnostic precision and treatment outcomes.

In conclusion, our study introduced a multicenter-validated prognosis predictive signature grounded in tumoral and peritumoral radiomic features, correlating with energy metabolism in breast cancer. This radiomic signature complemented clinical features in forecasting treatment response. Our results not only advance our understanding of the interplay between radiomics and tumor biology but also streamline the prediction of patient outcomes through noninvasive methods. This holds considerable potential for meaningful translation into future clinical practices, particularly in the development of personalized medicine and precision treatment strategies.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (NCT04461990). All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants in FUSCC dataset provided written informed consent. The DUKE and I-SPY1 datasets are sourced from TCIA, which offers an open-source repository of deidentified radiology data for the cancer research community. Therefore, Institutional Review Board approval was not required for the use of these datasets.

Study population

The FUSCC cohort initially included 584 consecutive breast cancer participants treated at FUSCC from January 2013 to December 2014. Following the exclusion criteria, which included (1) incomplete DCE-MRI; (2) no visible lesions; (3) poor image quality, determined by factors such as motion and breathing artifacts that blur images, low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) that affects contrast, and errors in uniformity and alignment of imaging planes; (4) exceptional biopsy before MRI; and (5) no clinical follow-up information, a total of 466 participants with prognosis information were included in the FUSCC radiomic-outcome dataset. The quality of the images was meticulously assessed by two radiologists experienced in breast imaging, C.Y. and S.Y.S., who independently identified poor quality images based on the aforementioned factors. In cases of disagreement, a senior radiologist, Y.J.G., reviewed the images to reach a consensus. Additionally, 420 samples with multiomic data were included in the FUSCC radio-multiomic dataset.

The DUKE cohort comprised 922 breast cancer participants from the Duke University dataset, obtained from the Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA). Similar exclusion criteria were applied, 619 participants with prognosis information remained and were included in the DUKE radiomic-outcome dataset. Furthermore, 217 participants who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy were included in the DUKE radiomic-treatment dataset.

The I-SPY1 cohort included 222 breast cancer participants from the I-SPY1 dataset, also sourced from the Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA). Following similar exclusion criteria, 128 participants with prognosis information were included in the I-SPY1 radiomic-outcome dataset. Additionally, 125 participants receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy constituted the I-SPY1 radiomic-treatment dataset (Fig. 1).

Neither treatment information in FUSCC cohort nor multiomic data in DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort were recorded.

Clinical outcomes

For prognosis prediction, the primary endpoint was relapse-free survival (RFS), defined as the time from diagnosis to the first recurrence, a diagnosis of contralateral breast cancer or death from any cause. The secondary endpoint was overall survival (OS), defined as the time from the time from diagnosis to death from any cause. In the FUSCC cohort, follow-up was completed on June 30, 2021, and the median length of follow-up was 81.1 months. Patients without events were censored at the time of the last follow-up. Detailed follow-up information of the DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort have been previously reported33,34.

For treatment response prediction, the primary endpoint was pathological complete response (pCR), and the secondary endpoint was response to treatment. In the DUKE cohort dataset, complete and near-complete responses were defined as responses, while others were defined as nonresponses. In the I-SPY1 cohort dataset, RCB classes 0 and 1 were defined as responses, and RCB classes 2 and 3 were defined as nonresponses33,34.

Study design

A four-step study was conducted as illustrated in Fig. 2. In the first step, tumor ROI were delineated; peritumoral area was obtained by expanding the tumor outward with a 5-mm width and subtracting the tumor area. Besides, tumor and peritumoral regions were integrated as whole tumor region. Radiomic features were extracted from these three sets of ROIs. In the second step, a thirteen-feature radiomic signature for prognosis prediction was identified in the training set of the FUSCC cohort radiomic-outcome dataset (containing 305 participants who underwent surgery from Jan 2013 to Apr 2014) by Lasso and Cox regression. The prognostic power of the risk score from the radiomic signature was tested in the testing set of the FUSCC cohort radiomic-outcome dataset (containing 161 participants who underwent surgery from May 2014 to Dec 2014), the DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort radiomic-outcome datasets (Fig. 4). In the third step, the biological foundation of prognostic radiomic signature was explored through the multiomic data analysis performed in the FUSCC cohort radiomic-multiomic dataset (Fig. 5). In the last step, the radiomic risk score generated in Step 1 was transferred to DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort radiomic-treatment datasets as radiomic model to predict neoadjuvant chemotherapy response. In addition, clinical and combined clinic-radiomic model was built to predict treatment response as well (Fig. 6).

DCE-MRI protocols

For the FUSCC cohort, all patients underwent preoperative breast DCE-MRI examination with 1.5 T special breast magnetic resonance and coils for breast. The imaging was performed using a T1-weighted sequence. The contrast medium Gd-DTPA (0.1 mmol/kg, flow rate 2.0 ml/s) was injected 90 s after plain scan. Postcontrast images were obtained at 90, 180 and 360 seconds after injection. The slice thickness was 3 mm, repetition time was 5.1 ms, echo time was 1.7 ms, field of view was 260 mm, and the flip angle was 15°.

For the DUKE cohort, DCE-MRI protocols were described elsewhere34. In brief, the imaging was performed using 1.5 T or 3 T breast DCE-MRI. The slice thickness ranged from 1.04 to 2.5 mm, repetition time ranged from 3.54 to 7.39 ms, echo time ranged from 1.25 to 2.76 ms, field of view ranged from 250 to 480 mm, and the flip angle ranged from 7 to 12°.

For the I-SPY1 cohort, DCE-MRI protocols were described elsewhere33. In brief, the imaging was performed using 1.5 T breast DCE-MRI with time msec/echo time msec, ≤20/4.5; flip angle, ≤45°; field of view, 16–18 cm; minimum matrix, 256 × 192; 64 sections; section thickness, ≤2.5 mm.

During image data preprocessing, all other phases were co-registered into the first postcontrast phase of DCE-MRI through non-linear registration using the symmetric normalization algorithm35, which was performed using the ANTs toolbox (version 2.3.5), to eliminate the spatial mismatches caused by motion artifacts. Nonparametric nonuniformity normalization algorithm was applied for bias field correction36. Moreover, z-score normalization in image domain was performed.

Data preprocessing

For data from the FUSCC cohort, DUKE cohort, and I-SPY1 cohort, DCE-MRIs were performed with various imaging protocols. In order to handle the inconsistency of the temporal point of the postcontrast phases, we defined pre-contrast, early postcontrast and late postcontrast phase based on the time point of the scan and the tumor to background (fat) relative enhancement ratio (\({TFRE\; ratio}\))15. Specifically, we first calculated the ratio of the mean voxel intensity of the tumor region to the fat region for each phase of DCE (\({TF\; ratio}\)):

N represents the total number of phases of the DCE sequence, where \(i=1\) represents the pre-contrast phase, \(i=2\ldots N\) represents each postcontrast phase. Then the \({TFRE\; ratio}\) is obtained by comparing the \({TF\; ratio}\) of each enhancement phase with the \({TF\; ratio}\) of the pre-contrast phase:

The TFRE ratio tended to increase and then decrease after contrast injection, we designate the phase with the largest \({TFRE\; ratio}\) as the early postcontrast phase, and designate the post peak phase with a lower \({TFRE\; ratio}\) and no more than 10% higher than the following phase as the late postcontrast phase (If there are too few phases and the above conditions are not met, directly select the last phase as the late postcontrast phase)37.

ROI segmentation and inter- and intra-observer reproducibility

Tumor regions of interest (ROIs) were delineated semiautomatically on the peak enhanced phase of DCE-MRI by 3D Slicer software (version 4.8.1)38. To ensure reproducibility, we tested the concordance of segmentations by conducting repeatability experiments for tumor outlining and feature extraction and obtained ideal intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC[1,k]), which can prove the stability of the results and the repeatability of the experiments to a certain extent. Specifically, 60 randomly selected samples were used to assess the intra- and inter-observer agreement of ROI segmentation. ROIs were delineated by two radiologists at FUSCC (C.Y. and S.Y.S with 9 and 4 years of experience in breast MRI; both were blinded to histopathology results). Additionally, one radiologist (C.Y.) repeated the tumor masking twice with an interval of at least a month and extracted shape-based (mesh volume, sphericity, surface area, surface area to volume ratio, elongation, maximum 3D diameter, minor axis length) and first order (voxel, entropy, kurtosis, skewness, maximum, minimum) radiomic features following the same process. In the concordance analysis, there was good consistency between two observers and between two delineations by one observer (intra-observer ICC > 0.9 and inter-observer ICC > 0.8). On this premise, whole ROI segmentation was completed by the more experienced radiologist in each layer of the MRI scan13.

Apart from the tumor area, the peritumoral area was obtained by expanding the tumor outward with a 5-mm width and subtracting the tumor area. Expanding operations were implemented automatically based on dilating algorithms, with a sphere morphological structuring element (radius = 5 mm). In addition, tumor and peritumoral regions were integrated as another region. In total, three sets of ROIs, including the tumor, peritumor and tumor-peritumor regions, were used in the radiomic feature extraction14.

Radiomic feature extraction

Before feature extraction, the image is uniformly resampled to a voxel size of 1 × 1 × 1 \({{mm}}^{3}\) using B-spline interpolation. The radiomic features of DCE-MRI images, including spatial domain features and sequential features, were extracted using the PyRadiomics package V3.039 (Supplementary Table 1), implemented in Python (version 3.6) and in-house pipelines. Spatial domain features include first-order features, textural features and wavelet features. First-order features describe the distribution of voxel intensities, and textural features were obtained based on five textural matrices to describe the radiological pattern of the ROI, including gray level co-occurrence matrix [GLCM, directions: 13 angles in 3D (26-connectivity), distance: 1 voxel], gray level dependence matrix (GLDM, cutoff value: 0, distance: 1 voxel), gray level run length matrix (GLRLM, directions: 13 angles in 3D), gray level size zone matrix (GLSZM, directions: 13 angles in 3D), neighboring gray tone difference matrix (NGTDM, neighborhood size: 3 × 3 × 3, distance: 1 voxel). The GLCM, GLSZM and GLRLM features were calculated separately for each angle, after which the average of these values was obtained. The definition and calculating formulas of first order, GLCM, GLDM, GLRLM GLSZM and NGTDM features were described in detail in https://pyradiomics.readthedocs.io/en/latest/features.html. Wavelet features were extracted for first order features and texture features after applying wavelet filtering to the original images, yielding 8 decompositions per level (LLL, LLH, LHL, HLL, LHH, HLH, HHL, HHH). Spatial domain features were calculated from each phase of MRI scan individually. Sequential features were calculated to consider time dimension information14, which primarily comprised two parts: (a) the feature enhancement rates among different phases on the timeline and (b) kinetic features includes the mean, variance, kurtosis and skewness of the time-varying curve constructed based on feature values in four phases, for each first order, textural and wavelet feature. Sequential features and corresponding calculation formulae were described in detail below, if they were not prespecified in Pyradiomics package.

Sequential features

Sequential features comprise two principal components: Feature enhancement ratios and kinetic features. Sequential features were extracted in our study to capture the dynamic behavior of the tumor’s radiomic profile across different phases of DCE-MRI. The phases are denoted as \({{dyn}}_{i}\), where \(i\) indexes each phase. Here \({{dyn}}_{0}\), \({{dyn}}_{1}\) and \({{dyn}}_{2}\) represent the pre-contrast phase, the early enhancement phase and the delayed enhanced phase, respectively. Each radiomic feature extracted from these phases is referred to as \({{DYN}}_{i}\), where \({{DYN}}_{i}\) specifically denotes the feature values calculated for the \(i\) phase.

Feature enhancement ratios are the rate of change of features between each two phases during contrast enhancement, which is defined as:

here \({{DYN}}_{i}\) represents the feature value of the phase \({{dyn}}_{{\rm{i}}}\), and \({{DYN}}_{{\rm{j}}}\) represents the feature value of the phase \({{dyn}}_{{\rm{j}}}\). \({Enh}\left({{dyn}}_{1},{{dyn}}_{0}\right)\), \({Enh}\left({{dyn}}_{2},{{dyn}}_{0}\right)\), \({Enh}\left({{dyn}}_{2},{{dyn}}_{1}\right)\) were calculated in this study.

Kinetic features indicate the mean, variance, skewness of the enhancement time-varying curves that represent the changes in features after the contrast agent was injected over time.

-

1.

Mean

$${mean}\Big({DYN}=[{{DYN}}_{1}\cdots {{DYN}}_{N}]\Big)=\frac{1}{N}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N}{{DYN}}_{i}$$(5) -

2.

Variance

$${variance}\Big({DYN}=[{DYN}_{1}\ldots {{DYN}}_{N}]\Big)=\frac{1}{N-1}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N}({{DYN}}_{i}-\overline{{DYN}})^{2}$$(6) -

3.

Skewness

As described in the ROI delineation, feature extraction was performed in the tumoral, peritumoral and tumor-peritumoral regions. Z-Score was used for data normalization. The batch effect of radiomic features was reduced via image normalization described in data preprocessing and feature normalization illustrated above.

Multiomic data generation

The generation of omics data, including gene mutation, copy number variation, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics and pathomics has been detailed reported in our previous study, the Chinese Breast Cancer Genome Atlas (CBCGA) project29. Matched genomic, transcriptomic and metabolomic data were included in our present radiomic analysis.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and single-sample GSEA

GSEA was performed in GSEA software (v4.3.2) and pathways were defined by the gene set file Human_GOBP_AllPathways_no_GO_iea_January_01_2022_symbol.gmt that is maintained and updated regularly by the Bader laboratory (http://download.baderlab.org/EM_Genesets/)40,41. GeneSet size was limited to range between 15 and 500, and 1000 permutations were carried out. The top results of the pathway analysis were visualized.

Differential abundance (DA) score

We compared abundance of polar metabolites and lipids in predicted high- and low- risk groups. Metabolites were considered to have significant differences between high- and low-radiomic risk groups if |log2FC | > 0.3 and p < 0.05, where metabolites with log2FC > 0.3 was increased and log2FC < -0.3 was decreased. The DA score was then calculated as follows42:

Thus, the DA score ranges from -1 to 1. A score of -1 indicates that all metabolites in a pathway decreased, while a score of 1 indicates that all metabolites increased in abundance. The components of the metabolic pathways used in the integrative analysis were annotated using the KEGG database.

Models for treatment response prediction

The performance of the radiomic signature in treatment response prediction was assessed in the DUKE cohort and I-SPY1 cohort treatment datasets, in which 217 and 125 patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, respectively. Information on treatment response is publicly available at TCIA (https://www.cancerimagingarchive.net/). In the radiomic-treatment datasets, the radiomic risk score and the clinical factors were utilized as independent inputs into a Logistic regression. Pathological complete response (pCR) and response to therapy were binary outcome variables (pCR as 1 and non-pCR as 0; or response as 1 and non-response as 0). Eighty-four patients with clinical and treatment information who were excluded from the radiomic dataset in the DUKE cohort were used for clinical variable selection and model training. Univariate logistic regression was utilized to assess the correlation between clinical factors and outcome variable pCR. Among clinical factors (age, menopause status, clinical T stage, clinical N stage, clinical M stage, ER status, PR status and HER2 status), molecular statuses (ER, PR and HER2) were correlated with pCR and ultimately designated as candidate clinical variables and were combined by multivariate logistic regression to generate clinical model.

Statistical analysis

The radiomic signature was identified by a two-step process including feature selection and model development. The crucial features for outcome prediction were selected using Lasso Cox regression with the alpha parameter set at 1, reflecting pure LASSO regularization. The optimal lambda value for regularization was determined via the ‘glmnet’ function in R, chosen based on performance metrics observed during 5-fold cross validation. Subsequently, a prognosis-predicting model was built using multivariate Cox regression in the FUSCC cohort radiomic-outcome training set.

Survival analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazard regression and Kaplan‒Meier method. Harrell’s C-index and Brier score were calculated to assess the performance of the prognosis prediction model. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and standard deviation of C-index were assessed by 1000 bootstrapping. The threshold of the risk score differentiating predicted high- and low-risk samples was the median risk score in the FUSCC cohort training set. A log-rank test was conducted to compare the distinct outcomes of predicted high- and low-risk patients. A multivariate Cox regression was used to assess whether the radiomic risk score was independently correlated with prognosis when adjusting for clinical variables. In the treatment datasets, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated to evaluate the predictive performance of the response prediction model. Permutation test was performed to test whether the given model was significantly better than chance.

For feature explanation, hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs were calculated using univariate Cox regression to assess the prognostic value of each radiomic feature. The Spearman coefficient was calculated to assess the correlation between radiomic features and the predicted risk score. Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare the gene mutation frequency of predicted high- and low-risk patients. In general, p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant unless otherwise specified. P-adjust values were calculated considering the false discovery rate (FDR) through the Benjamini–Hochberg method for multiple comparisons in GSEA and other applicable analyses. GSEA was performed with GSEA software (version 4.3.2). Other statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.1.1).

Data availability

Original images of DUKE and ISPY-1 breast MRI are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.7937/TCIA.e3sv-re93 and https://doi.org/10.7937/K9/TCIA.2016.HdHpgJLK. Radiomics data from the FUSCC breast cancer MRI cohort have been deposited in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10219733). Multiomic data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive database under accession code PRJCA017539.

Code availability

The code for this study is open-source and publicly available on our GitHub repository (https://github.com/2023XuZhang9/MRAPBCOUIC_Radiomics).

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 17–48 (2023).

Waks, A. G. & Winer, E. P. Breast cancer treatment: a review. JAMA 321, 288 (2019).

Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490, 61–70 (2012).

Jiang, X. et al. An MRI deep learning model predicts outcome in rectal cancer. Radiology 307, e222223 (2023).

Bera, K., Braman, N., Gupta, A., Velcheti, V. & Madabhushi, A. Predicting cancer outcomes with radiomics and artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 132–146 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Intratumoral spatial heterogeneity at perfusion MR imaging predicts recurrence-free survival in locally advanced breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Radiology 288, 26–35 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. Radiological tumor classification across imaging modality and histology. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 787–798 (2021).

Mann, R. M., Cho, N. & Moy, L. Breast MRI: state of the art. Radiology 292, 520–536 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. Development and validation of a preoperative magnetic resonance imaging radiomics-based signature to predict axillary lymph node metastasis and disease-free survival in patients with early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2028086 (2020).

Chitalia, R. D. et al. Imaging phenotypes of breast cancer heterogeneity in preoperative breast dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic Resonance Imaging (DCE-MRI) scans predict 10-year recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 862–869 (2020).

Bitencourt, A. G. V. et al. MRI-based machine learning radiomics can predict HER2 expression level and pathologic response after neoadjuvant therapy in HER2 overexpressing breast cancer. EBioMedicine 61, 103042 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Radiomics of multiparametric MRI for pretreatment prediction of pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: a multicenter study. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 3538–3547 (2019).

Jiang, L. et al. Radiogenomic analysis reveals tumor heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 3, 100694 (2022).

Su, G.-H. et al. Radiogenomic-based multiomic analysis reveals imaging intratumor heterogeneity phenotypes and therapeutic targets. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf0837 (2023).

Park, H. et al. Radiomics signature on magnetic resonance imaging: association with disease-free survival in patients with invasive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 4705–4714 (2018).

Bi, W. L. et al. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J. Clin. 69, 127–157 (2019).

Cheplygina, V., De Bruijne, M. & Pluim, J. P. W. Not-so-supervised: a survey of semi-supervised, multi-instance, and transfer learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 54, 280–296 (2019).

Fan, M. et al. Radiogenomic signatures of oncotype DX recurrence score enable prediction of survival in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: a multicohort study. Radiology 302, 516–524 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Radiomics for survival risk stratification of clinical and pathologic stage IA pure-solid non-small cell lung cancer. Radiology 302, 425–434 (2022).

Vaidya, P. et al. CT derived radiomic score for predicting the added benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery in Stage I, II resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: a retrospective multi-cohort study for outcome prediction. Lancet Digit Health 2, e116–e128 (2020).

Khorrami, M. et al. Changes in CT radiomic features associated with lymphocyte distribution predict overall survival and response to immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 8, 108–119 (2020).

Braman, N. et al. Association of peritumoral radiomics with tumor biology and pathologic response to preoperative targeted therapy for HER2 (ERBB2)-positive breast cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e192561 (2019).

Pinker, K., Chin, J., Melsaether, A. N., Morris, E. A. & Moy, L. Precision medicine and radiogenomics in breast cancer: new approaches toward diagnosis and treatment. Radiology 287, 732–747 (2018).

Finley, L. W. S. What is cancer metabolism? Cell 186, 1670–1688 (2023).

Sun, Q. et al. Biologic pathways underlying prognostic radiomics phenotypes from paired MRI and RNA sequencing in glioblastoma. Radiology 301, 654–663 (2021).

Wu, J., Mayer, A. T. & Li, R. Integrated imaging and molecular analysis to decipher tumor microenvironment in the era of immunotherapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 84, 310–328 (2022).

Boehm, K. M. et al. Multimodal data integration using machine learning improves risk stratification of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Cancer 3, 723–733 (2022).

Jiang, Y.-Z. et al. Integrated multiomic profiling of breast cancer in the Chinese population reveals patient stratification and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Nat. Cancer https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-024-00725-0 (2024).

Loibl, S., Poortmans, P., Morrow, M., Denkert, C. & Curigliano, G. Breast cancer. Lancet 397, 1750–1769 (2021).

Callari, M. et al. Subtype-specific metagene-based prediction of outcome after neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 337–345 (2016).

Sammut, S.-J. et al. Multi-omic machine learning predictor of breast cancer therapy response. Nature 601, 623–629 (2022).

Hylton, N. M. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: functional tumor volume by MR imaging predicts recurrence-free survival-results from the ACRIN 6657/CALGB 150007 I-SPY 1 TRIAL. Radiology 279, 44–55 (2016).

Saha, A. et al. A machine learning approach to radiogenomics of breast cancer: a study of 922 subjects and 529 DCE-MRI features. Br. J. Cancer 119, 508–516 (2018).

Avants, B. B., Epstein, C. L., Grossman, M. & Gee, J. C. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med. Image Anal. 12, 26–41 (2008).

Sled, J. G., Zijdenbos, A. P. & Evans, A. C. A nonparametric method for automatic correction of intensity nonuniformity in MRI data. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 17, 87–97 (1998).

Mercado, C. L. BI-RADS update. Radio. Clin. North Am. 52, 481–487 (2014).

Fedorov, A. et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 30, 1323–1341 (2012).

van Griethuysen, J. J. M. et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 77, e104–e107 (2017).

Nassiri, F. et al. A clinically applicable integrative molecular classification of meningiomas. Nature 597, 119–125 (2021).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Hakimi, A. A. et al. An integrated metabolic Atlas of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 29, 104–116 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82271957, 82071878 and 82373167) and Shanghai Medical Innovation Research Project (22Y11912700).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y., G.-H.S., X.Z., and Y.X. contributed equally to this study. C.Y.: Methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. G.-H.S.: Methodology, software, investigation, writing – original draft. X.Z.: Data curation, investigation, writing—original draft. Y.X.: Investigation, writing—review & editing. R.-C.Z.: Form analysis, software. S.-Y.S.: Data curation. J.-Y.Z.: Data curation. L.-Y.L.: Data curation. Z.-Z.W.: Writing—review & editing. H.W.: Writing—review & editing. Y.C.: Writing—review & editing. W.-J.P.: Writing—review & editing, supervision. Y.-Z.J.: Conceptualization, supervision. Z.-M.S.: Conceptualization, resources, supervision. Y.-J.G.: Conceptualization, resources, supervision, project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, C., Su, GH., Zhang, X. et al. Multicenter radio-multiomic analysis for predicting breast cancer outcome and unravelling imaging-biological connection. npj Precis. Onc. 8, 193 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00666-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00666-y

This article is cited by

-

Deciphering the biological underpinnings behind prognostic MRI-based imaging signatures in breast cancer: a systematic review

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)

-

CT-based radiomics model for noninvasive prediction of progression-free survival in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma: a multicenter study incorporating preoperative and postoperative clinical factors

BMC Medical Imaging (2025)

-

Preoperative DBT-based radiomics for predicting axillary lymph node metastasis in breast cancer: a multi-center study

BMC Medical Imaging (2025)

-

Spatial-temporal radiogenomics in predicting neoadjuvant chemotherapy efficacy for breast cancer: a comprehensive review

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)

-

A 20-feature radiomic signature of triple-negative breast cancer identifies patients at high risk of death

npj Breast Cancer (2025)