Abstract

The cytogenetic abnormality inv(2)(p23q13) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) results in a fusion of RANBP2 with ALK. This fusion makes ALK constitutively active and acts as a driver for the proliferation of AML cell lines. Gilteritinib, a FLT3 inhibitor approved in AML, also can inhibit ALK among other receptor tyrosine kinases. A 75-year-old-woman with a history of essential thrombocythemia (ET) and a presumed germline DDX41 mutation developed ALK-fusion positive AML and despite standard therapies was transfusion-dependent and globally declining. The patient has been on gilteritinib with an ongoing response of more than one year with near normal blood counts and no evidence of AML. The fact that she was found to harbor a presumed germline DDX41 alteration may account for why she developed, and yet survived, two myeloid neoplasms (ET and AML). Additionally, this demonstrates that gilteritinib is clinically active as an ALK inhibitor, and could be considered for use in any AML patient presenting with an inv(2(p23q13)) translocation. Finally, it is an example of using a disease-agnostic, precision medicine approach to arrive at a beneficial treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia is an aggressive blood cancer with a variable prognosis, one that is heavily influenced by the genetic aberrations present within the leukemia cells. Comprehensive genetic profiling of the disease is therefore an essential component of management1. AML arising out of an antecedent myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) generally has an extremely poor prognosis2. Interestingly, the driver mutations present in the MPN are often not detectable in the blasts emerging with the transformed disease, suggesting that both the MPN and the AML arise from a common progenitor3.

The anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that has been found to be mutated (by sequence, amplification, or translocation) in a number of malignancies, including lymphoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and AML4. Additionally, the hematologic malignancy, anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is known to be ALK-positive in 60% of cases5. Fusions and point mutations that cause aberrant, constitutive activation of ALK are known to occur in AML6,7,8. The most common of these is the karyotypic abnormality inv(2)(p23q13), which results in a fusion of the Ran-binding Protein2 (RANBP2) with ALK. This genetic abnormality, while uncommon, occurs on a routine if intermittent basis in leukemia centers around the world.

There are now a number of small molecular ALK inhibitors approved for the treatment of NSCLC, including alectinib, brigatinib, ceritinib, crizotinib, and lorlatinib, which while effective, can often be associated with significant side effects, predominantly gastrointestinal toxicities9. Gilteritinib is a small molecule inhibitor of the RTK FLT3 that is approved for the treatment of relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML10. Published in vitro data indicate that gilteritinib inhibits ALK with a potency similar to the degree to which it inhibits FLT311. It has an extremely favorable safety and tolerability profile in AML patients. There have been several previous reports of the AML patients effectively being treated with the ALK inhibitor crizotinib12,13,14,15. We report here the case of a patient with AML harboring a RANBP2-ALK fusion arising out of an antecedent myeloproliferative disorder who was successfully treated with gilteritinib. Our findings confirm that a RANBP2-ALK fusion can act as a driver mutation in AML and that gilteritinib can be a clinically effective and well-tolerated ALK inhibitor and could be considered as a component of treatment for any AML patient whose disease harbors an inv(2)(p23q13) mutation.

Results

Case presentation

The patient is a woman aged 75 when she first came under our care. She had a history of primary hypertension and hypothyroidism, and in 2009 she developed a transient ischemic attack and was found to have an elevated platelet count. A bone marrow biopsy established a diagnosis of essential thrombocythemia (ET) with a JAK2 V617F mutation. She was managed initially with aspirin, and eventually with aspirin combined with hydroxyurea, and remained asymptomatic until 2023 when she developed fatigue and was found to have a white blood cell (WBC) count of 78,360/mm3. At that time, her hemoglobin was 8.9 g/dL and platelets were 82,000/mm3. The patient was admitted to our medical center and a bone marrow biopsy was performed. The marrow cellularity was 80%, with predominantly immature cells and decreased megakaryocytes. Flow cytometric analysis showed 15% blasts expressing bright CD13, CD33, CD34, CD64, and CD7 with variable expression of CD11b, CD38, HLA-DR, and negative for CD117. These blasts merged with a large population of immature, abnormal monocytes expressing partial CD56 with partial loss of HLA-DR and CD14, establishing a diagnosis of monocytic AML by WHO 2022 criteria16.

Comprehensive genetic analysis was performed on the diagnostic marrow sample. G-banding analysis of the unstimulated marrow yielded a single cell line with 20 metaphases examined. The abnormal clone (20/20 cells) had female sex chromosomes and included the loss of one copy of chromosome 7 along with a pericentric inversion of chromosome 2. The final karyotype was reported as 45, XX, inv(2)(p23q13), −7[20] and was confirmed with Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH). RNA was isolated from the marrow specimen using the QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Beverly, MA) and analyzed using a custom gene fusion panel developed at the Johns Hopkins Molecular Diagnostics laboratory (https://pathology.jhu.edu/MolecularDiagnostics/tests/cfm). Briefly, the RNA was incubated with a panel of custom probes from 102 known gene fusions found in hematologic malignancies and analyzed using NanoString nCounter technology (NanoString Technologies, Inc., Seattle, WA). Using this test, the RANBP2-ALK (Ran Binding Protein 2-anaplastic lymphoma kinase) fusion was detected, consistent with the karyotypic finding of inv(2)(p23q13) (Fig. 1)17. Finally, next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on DNA from the marrow sample using Illumina (San Diego, CA) paired end technology and revealed the presence of a DDX41 P206A mutation with a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 51.53%. The DDX41 mutation was unknown to the referring physician, and the gene was only recently added to the myeloid hotspot panel at our institution. It was presumed to be germline, although this was not confirmed by skin biopsy or assay of any non-hematologic tissue.

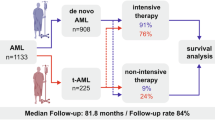

Due to her age and the poor risk nature of her leukemia (MPN transformed into AML), the patient was given an increased dosage of hydroxyurea for cytoreduction and then induced using azacytidine and venetoclax18. She tolerated this treatment well and after a single cycle her symptoms of fatigue resolved. She received two additional cycles of azacytidine and venetoclax and was red blood cell (RBC) and platelet transfusion-independent during this time. Two separate follow up bone marrow biopsies revealed persistence of the inv(2) and 7- karyotype along with the (presumed) germline DDX41 mutation in a setting of persistent abnormal monocytes, but blasts were under 1% by flow cytometry. Following her third cycle of treatment (four months after her original AML diagnosis), her disease progressed again, with rapidly rising WBC count and fatigue, and with no new mutations detected on genetic profiling. She underwent a series of prolonged hospitalizations, treated initially with gemtuzumab ozogamicin, decitabine combined with venetoclax, and finally with increasing doses of hydroxyurea, to control her WBC count. Her disease proved refractory, with persistent peripheral blood monocytosis and circulating blasts. The patient experienced neutropenic fevers, cholecystitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and increasing RBC and platelet transfusion-dependence along with worsening performance status. A referral to hospice was under discussion.

At this point, seven months after her original AML diagnosis, consideration was given to using an ALK inhibitor, given the RANBP2-ALK fusion resulting from the inv(2)(p23q13) abnormality. While there are currently five ALK inhibitors with FDA approval for the treatment of ALK-mutated NSCLC, the choice was made to seek third-party payor approval for gilteritinib. Gilteritinib is an oral small molecule kinase inhibitor FDA-approved for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML. As such, it is well tolerated by patients fitting this patient’s general clinical profile and is routinely approved by third-party payors for patients with an ICD10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision) code of C92.00 (corresponding to AML). Gilteritinib was selected among the multiple FDA-approved ALK inhibitors because of feasibility of obtaining the drug with insurance coverage and tolerability in a less fit patient. In vitro data indicated that gilteritinib inhibited ALK with similar potency as FLT3 (Fig. 2), and the patient’s insurance approved of the use of this drug. Gilteritinib was started at a dose of 120 mg/day, without concomitant hydroxyurea or any other anti-leukemic therapy.

Kinome assay, testing 468 kinases, showing the ability of gilteritinib at 100 nanomolar to inhibit the binding of various kinases (red) and of inhibiting the binding to ALK (blue). The top figure represents gilteritinib inhibition of ALK wildtype in blue (other wildtype genes in red) and the bottom figures represent gilteritinib inhibition of mutated ALK in blue, other mutations (in red), and atypical or lipid genes. The larger the circle correlates to a higher degree of inhibition. Image generated using TREEspot™ Software Tool and reprinted with permission from KINOMEscan®, a division of DiscoveRx Corporation, © DISCOVERX CORPORATION 2010. AGC, protein kinase A, protein kinase G, and protein kinase C related; CAMK, Ca2 + /calmodulin-dependent kinases; CMGC, Cdk, MAPK, GSK, Cdk-like related; CK1, casein kinase 1; STE, serine/threonine kinases; TK, tyrosine kinases; TKL, tyrosine-like kinases.

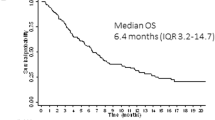

Within 3 weeks of starting gilteritinib, the patient became transfusion-independent, with resolution of fatigue and near-normalization of her peripheral blood counts over the ensuing 8 weeks (Fig. 3). 10 weeks after starting gilteritinib, her absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was 1,580/mm3, the hemoglobin was 9.6 g/dL, platelets were 234,000/mm3, and there were no circulating blasts. A bone marrow biopsy at this time revealed a 20% cellular marrow with atypical megakaryocytes, and no increase in blasts or abnormal monocytes. Her karyotype was 46XX, FISH was normal, and NGS revealed the DDX41 P206A mutation with a VAF of 49.13%, and a re-appearance of the original JAK2 V617F mutation with a VAF of 20.37%. Fourteen months after starting gilteritinib, and 21 months after the original diagnosis, the patient remains asymptomatic, with an ANC of 6.69, hemoglobin of 13.2, and platelets of 579, essentially having returned to having ET. She is on aspirin and low-dose hydroxyurea to control the platelet count and remains on gilteritinib.

The top graph shows the timeline of this patient’s hemoglobin levels (g/dL) from diagnosis to starting various therapies and ultimately starting gilteritinib and the date of her last packed red blood cell (pRBC) transfusion. The bottom graph shows a similar timeline of this patient’s platelet count (K/cu mm) from initiating various therapies and having low platelet counts to starting gilteritinib and her last platelet transfusion. The darker shaded blue represents the lab normal ranges for each respective count. Created with BioRender.com.

Discussion

This case demonstrates that mutation-activated ALK can act as a driver of AML and provides clear evidence of the clinical efficacy of gilteritinib as an ALK inhibitor. It also underscores several significant themes in the ever-evolving field of oncology therapeutics. It acknowledges the potential for ALK-fusions to be relevant in a variety of cancer types, beyond NSCLC, demonstrating their responsiveness to ALK-directed treatments19,20,21. The case also underscores the crucial role of access to vital therapies, often determined by insurance companies, especially when NCCN guidelines or FDA approvals are lacking, which can have adverse effects on patient outcomes.

The DDX41, DEAD-box helicase 41, gene encodes a protein that functions as an RNA helicase, which plays a role in RNA metabolism and regulation of gene expression. DDX41 mutations have been identified in familial and sporadic myeloid malignancies cases and represent roughly 2–4% of myelodysplastic syndromes and AML cases22,23,24. Interestingly, patients with germline DDX41 alterations, despite having an increased risk of myeloid malignancies (and our patient having both AML and ET), appear to have a survival advantage compared to those patients without a germline alteration25.

There is currently one tissue-agnostic FDA approval for a hematologic malignancy, which is pemigatinib for relapsed or refractory myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with FGFR1 rearrangement26. This approval was based on a 40 patient, phase II study that reported a >70% complete cytogenetic response rate and median duration of response that was not reached. The rarity of such genomic aberrations shows the importance of using comprehensive molecular profiling to develop genomic-directed therapies to inform treatment decisions and improve outcomes for patients. The use of ALK inhibitors is effective in patients with a different hematologic malignancy, ALK-positive ALCL, further acknowledging the utility of ALK inhibitors in hematologic malignancies27,28,29,30,31. Conducting extensive basket trials that encompass all hematologic malignancies with ALK-fusions is likely essential to validate this concept, similar to the approach taken with RET fusions and the effectiveness of RET-directed therapies32. However, the low incidence of ALK-fusions, occurring in approximately 0.2% of cancers, presents a challenge in generating sufficient data for FDA and insurance approvals.

Additionally, the agent employed in this case was not an FDA-approved ALK inhibitor. Gilteritinib has shown preclinically to be a potent ALK inhibitor11,33,34. Interestingly, there is additional evidence that gilteritinib may also be active against lorlatinib-resistant ALK alterations35. The reason gilteritinib was used in this case instead of one of the FDA-approved ALK inhibitors was because of the ease of approval from the patient’s insurance company, since gilteritinib has an indication in AML.

This case raises questions about the “right to try” for cancer patients and underscores the importance of compassionate use programs provided by pharmaceutical companies, which can be instrumental in cases like this36. Given the rarity of ALK-fusions in hematologic malignancies, there may never be clinical trials or FDA approvals available except for a tumor-agnostic approach, as seen with other oncogenic aberrations such as BRAF V600E, NTRK, RET, among others37. The approval and insurance coverage process remains challenging for rare cancer types with uncommon targetable genetic alterations, often leaving these patients with suboptimal options within the healthcare system.

Nevertheless, the extensive genomic and transcriptomic profiling of patients with AML using comprehensive panels can offer valuable insights into novel therapeutic options and can identify point mutation in ALK, as demonstrated in this case. The patient in question continues to experience clinical benefits, maintaining a complete morphologic response fourteen months after initiating treatment, underscoring the importance of precision medicine and routine molecular profiling to address disparities apparent in all types of cancer37.

Methods

Case summary

A 75-year-old-woman with a history of ET and a presumed germline DDX41 mutation developed RANBP2-ALK fusion positive AML and despite standard therapies was transfusion-dependent and globally declining. The patient was treated with gilteritinib to specifically target the ALK alteration. Her blood counts returned to near-normal levels, her transfusion independence resolved, and a follow up bone marrow biopsy showed no evidence of AML. The patient continues to take gilteritinib with an ongoing response of more than one year. The patient provided written informed consent for the publication of this study and to the use of her data. The patient also provided written consent to participate in the study and it was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

Dohner, H. et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 140, 1345–1377 (2022).

Tefferi, A. et al. Blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasm: Mayo-AGIMM study of 410 patients from two separate cohorts. Leukemia 32, 1200–1210 (2018).

Theocharides, A. et al. Leukemic blasts in transformed JAK2-V617F-positive myeloproliferative disorders are frequently negative for the JAK2-V617F mutation. Blood 110, 375–379 (2007).

Ross, J. S. et al. ALK fusions in a wide variety of tumor types respond to anti-ALK targeted therapy. Oncologist 22, 1444–1450 (2017).

Kaseb H., Mukkamalla S. K. R., Rajasurya V. Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Shiva Kumar Mukkamalla declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Venkat Rajasurya declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies (2024).

Wlodarska, I. et al. The cryptic inv(2)(p23q35) defines a new molecular genetic subtype of ALK-positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood 92, 2688–2695 (1998).

Maesako, Y. et al. inv(2)(p23q13)/RAN-binding protein 2 (RANBP2)-ALK fusion gene in myeloid leukemia that developed in an elderly woman. Int. J. Hematol. 99, 202–207 (2014).

Maxson, J. E. et al. Therapeutically targetable ALK mutations in leukemia. Cancer Res. 75, 2146–2150 (2015).

Kassem, L. et al. Safety issues with the ALK inhibitors in the treatment of NSCLC: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 134, 56–64 (2019).

Perl, A. E. et al. Gilteritinib or chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1728–1740 (2019).

Lee, L. Y. et al. Preclinical studies of gilteritinib, a next-generation FLT3 inhibitor. Blood 129, 257–260 (2017).

Maesako, Y. et al. Reduction of leukemia cell burden and restoration of normal hematopoiesis at 3 months of crizotinib treatment in RAN-binding protein 2 (RANBP2)-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 28, 1935–1937 (2014).

Takeoka, K., Okumura, A., Maesako, Y., Akasaka, T. & Ohno, H. Crizotinib resistance in acute myeloid leukemia with inv(2)(p23q13)/RAN binding protein 2 (RANBP2) anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion and monosomy 7. Cancer Genet. 208, 85–90 (2015).

Hayashi, A. et al. Crizotinib treatment for refractory pediatric acute myeloid leukemia with RAN-binding protein 2-anaplastic lymphoma kinase fusion gene. Blood Cancer J. 6, e456 (2016).

Shekar, M. et al. ALK fusion in an adolescent with acute myeloid leukemia: A case report and review of the literature. Biomedicines 11, 1842 (2023).

Khoury, J. D. et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 36, 1703–1719 (2022).

Ma, Z. et al. Fusion of ALK to the Ran-binding protein 2 (RANBP2) gene in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 37, 98–105 (2003).

DiNardo, C. D. et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 617–629 (2020).

Pal, S. K. et al. Responses to alectinib in ALK-rearranged papillary renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 74, 124–128 (2018).

Bagchi, A. et al. Lorlatinib in a child with ALK-fusion-positive high-grade glioma. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 761–763 (2021).

Adashek, J. J., Sapkota, S., de Castro Luna, R. & Seiwert, T. Y. Complete response to alectinib in ALK-fusion metastatic salivary ductal carcinoma. NPJ Precis Oncol. 7, 36 (2023).

Kim, K., Ong, F. & Sasaki, K. Current understanding of DDX41 mutations in myeloid neoplasms. Cancers (Basel) 15, 344 (2023).

Polprasert, C. et al. Inherited and somatic defects in DDX41 in myeloid neoplasms. Cancer Cell 27, 658–670 (2015).

Makishima, H. et al. Germ line DDX41 mutations define a unique subtype of myeloid neoplasms. Blood 141, 534–549 (2023).

Duployez, N. et al. Prognostic impact of DDX41 germline mutations in intensively treated acute myeloid leukemia patients: an ALFA-FILO study. Blood 140, 756–768 (2022).

Patel, T. H. et al. FDA approval summary: Pemigatinib for previously treated, unresectable locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR2 fusion or other rearrangement. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 838–842 (2023).

Brugieres, L. et al. Efficacy and safety of crizotinib in ALK-positive systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in children, adolescents, and adult patients: results of the French AcSe-crizotinib trial. Eur. J. Cancer 191, 112984 (2023).

Veleanu, L., Lamant, L. & Sibon, D. Therapeutic strategy project for adult AA. Brigatinib in ALK-positive ALCL after failure of brentuximab vedotin. N. Engl. J. Med. 390, 2129–2130 (2024).

Fukano, R. et al. Alectinib for relapsed or refractory anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma: An open-label phase II trial. Cancer Sci. 111, 4540–4547 (2020).

Wirk, B., Malysz, J., Choi, E. & Songdej, N. Lorlatinib induces rapid and durable response in refractory anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive large B-cell lymphoma. JCO Precis Oncol. 7, e2200536 (2023).

Fischer, M. et al. Ceritinib in paediatric patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive malignancies: An open-label, multicentre, phase 1, dose-escalation and dose-expansion study. Lancet Oncol. 22, 1764–1776 (2021).

Adashek, J. J. et al. Hallmarks of RET and co-occuring genomic alterations in RET-aberrant cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 20, 1769–1776 (2021).

Kuravi, S. et al. Preclinical evaluation of gilteritinib on NPM1-ALK-driven anaplastic large cell lymphoma cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 19, 913–920 (2021).

Ando, C. et al. Efficacy of gilteritinib in comparison with alectinib for the treatment of ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 114, 4343–4354 (2023).

Mizuta, H. et al. Gilteritinib overcomes lorlatinib resistance in ALK-rearranged cancer. Nat. Commun. 12, 1261 (2021).

Cohen-Kurzrock, B. A., Cohen, P. R. & Kurzrock, R. Health policy: The right to try is embodied in the right to die. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 13, 399–400 (2016).

Tateo, V. et al. Agnostic approvals in oncology: Getting the right drug to the right patient with the right genomics. Pharm. (Basel) 16, 614 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors drafted the manuscript. J.J.A. and M.J.L. created the figures. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.J.A. serves on the advisory board of CureMatch Inc. and serves as a consultant for datma. M.B. has no relevant competing interests to disclose. M.J.L. declares Astellas (Laboratory Service Agreement) and Astellas, Daiichi-Sankyo, Abbvie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Jazz, Schroedinger, Syndax, Takeda (Consultant/Advisor/clinical trial funding).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adashek, J.J., Brodsky, M. & Levis, M.J. Complete morphologic response to gilteritinib in ALK-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia. npj Precis. Onc. 8, 197 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00701-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00701-y