Abstract

A deep learning model using attention-based multiple instance learning (aMIL) and self-supervised learning (SSL) was developed to perform pathologic classification of neuroblastic tumors and assess MYCN-amplification status using H&E-stained whole slide images from the largest reported cohort to date. The model showed promising performance in identifying diagnostic category, grade, mitosis-karyorrhexis index (MKI), and MYCN-amplification with validation on an external test dataset, suggesting potential for AI-assisted neuroblastoma classification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is a neuroblastic tumor (NT) and the most common extracranial pediatric solid tumor, affecting nearly 800 children in the United States annually1. To select optimal treatment strategies, patients are risk-stratified according to prognostic clinical, pathologic, and molecular variables including age, stage, histopathology, and MYCN-amplification2,3. Approximately 40% of patients with neuroblastoma are classified as high-risk, which carries a 60% overall 3-year likelihood of event-free survival4. MYCN-amplification is present in 20% of NTs and, except for completely resected stage L1 tumors, typically places the patient in the high-risk category5.

The pathologic classification of NTs is a major contributor to risk stratification. The International Neuroblastoma Pathology Committee (INPC) uses combinations of four features—age, diagnostic category (neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma intermixed, ganglioneuroma, or ganglioneuroblastoma nodular), grade of differentiation, and mitosis-karyorrhexis index (MKI)—to classify tumors as favorable or unfavorable histology6. INPC classification has significant prognostic ability unto itself, as those with unfavorable histology have a four times higher likelihood of relapse compared to those with favorable histology2.

Histology from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides can also serve as a rich data source for deep learning models, which can be used to identify nuanced motifs in tumor morphology and produce precise risk stratification criteria7,8,9. Machine learning algorithms have been used to analyze NT digitized histology as early as 2009, with models that segmented cells and extracted texture features from histology images to predict tumor grade10. More recently, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been deployed on NT histology risk stratification11.

Using our open-source deep learning analysis pipeline, Slideflow (2.3.1), we developed an attention-based multiple instance learning (aMIL) model with features extracted by UNI, a pre-trained self-supervised learning (SSL) model12,13,14. In contrast to weakly-supervised methods leveraging conventional CNNs, aMIL models rely on pre-trained features to begin model training (Fig. 1). These features are obtained by passing images through a feature extractor network that has been pre-trained on either domain-specific or non-specific images. UNI is a domain-specific model that has been trained on over 100 million images from more than 100,000 diagnostic H&E-stained slides across 20 major tissue types15. For limited datasets such as those obtainable in rare diseases, using domain-specific features to train an aMIL can offer significant performance advantages over non-specific models such as ImageNet16,17.

A Number of slides in the training and test cohorts by pathologic category. B Models were pre-trained with histology-specific digital images using unsupervised domain-specific learning to extract features with UNI. C Whole slide images (WSI) were divided into tiles, passed through the fine-tuned network to generate pathology-specific feature vectors, which are divided into bags per WSI. The aMIL network assigns attention scores to vectors, and a slide-level prediction is determined based on the aggregated predictions weighted by attention scores.

In this study, we leveraged the largest reported study cohort of digitized NTs analyzed with these modern deep learning methods. We generated a training dataset of whole slide images (WSIs) from patients from the University of Chicago and the Children’s Oncology Group. These WSIs were used to develop models for predicting diagnostic category, grade, MKI, and MYCN-amplification status. Model performance was assessed on an external test dataset of WSIs from patients seen at Lurie Children’s Hospital. We aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of using a fully automated pipeline to aid in NT classification and risk stratification.

The median age of patients with digitalized NT in the training dataset (n = 172) was 2.63 years (SD = 4.37). Among patients with additional known clinical information, 84 of 138 (60%) had metastatic disease and 94 of 133 (71%) were high-risk. For diagnostic category, the dataset includes 24 ganglioneuroblastomas and 148 neuroblastomas which were confirmed by pathologists (K.D., H.S., P.P., N.C., A.H.). There were no ganglioneuroma samples available for this cohort. Of the 148 tumors with a diagnostic category of neuroblastoma, 93.2% were poorly differentiated and 25% had high MKI. Of the 125 tumors with known MYCN status, 40 were amplified (32%). The median age of the external test dataset at diagnosis (n = 25) was 3.33 years (SD = 2.90). All patients in the test dataset were high-risk and 23 of 25 (92%) had metastatic disease. All 25 tumors were classified as neuroblastoma and all were poorly differentiated. Twelve of these 23 tumors (52%) had a low/intermediate MKI. Eight of the 25 neuroblastoma tumors (32%) were MYCN-amplified.

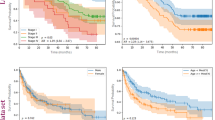

The final models demonstrated accurate performance across all outcomes in the training cohort (Fig. 2). The model demonstrated strong performance across all categories, with diagnostic category classification showing the highest accuracy. Performance for grade, MKI, and MYCN status prediction was also robust. The model exhibited the best sensitivity and specificity for identifying diagnostic categories, while MYCN status prediction showed good specificity but lower sensitivity.

A Performance metrics for the training dataset were generated with threefold cross validation (left). Locked models were subsequently tested on the full training dataset and evaluated on the external test dataset for one single run with results shown (right) with all 95% confidence intervals noted. B Explainability heatmaps generated with attention mapping. Yellow regions were highly weighted and informative to the model while dark purple regions corresponded to low weights in generating predictions. C Representative high and low attention tiles for diagnosis, MKI, and MYCN. Presented are three highest attention tiles and three lowest attention tiles for a random subset of three slides across diagnosis, MKI, and MYCN. In the high attention tiles, notable features include tumor cells associated with curvilinear vessels (yellow square), regions demonstrating differences in stromal composition and neuropil (green square), and areas of small round blue cell hyperproliferation (red square). AUROC area under the receiver operator curve, AUPRC area under the precision recall curve, MKI mitosis-karyorrhexis index.

Using an independent cohort of clinically annotated NT tumors, the models demonstrated accuracy across all analyzed outcomes (Fig. 2). On the external validation dataset, the model showed promising performance across available categories, though we could not fully validate the models of diagnostic category and grade as slides from only one class were available. Diagnostic category classification showed the highest accuracy and precision. MKI and MYCN status predictions demonstrated good accuracy, with balanced sensitivity and specificity. Grade prediction showed moderate accuracy with high precision.

Expert pathologist (P.P., N.C., A.H.) review of the model’s predictions revealed insights into the histopathological features that contribute to neuroblastoma classification (Fig. 2B). This analysis was limited by the small sample number that precluded more detailed studies such as synthetic histology-based feature interrogation18. The analysis uncovered specific cellular and stromal arrangements that appear to be particularly informative for the model’s decision-making process. A key finding was the model’s focus on complex cellular arrangements such as nodules of neuropil surrounded by small round blue cells. These structures, especially when adjacent to curvilinear blood vessels, emerged as significant predictors (Fig. 2C). This suggests that the spatial relationship between tumor cells, neuropil, and vasculature may be more important in diagnostic classification than previously recognized. The model also demonstrated sensitivity to stromal composition. It accurately distinguished between areas of cellular stroma, such as spindled Schwannian stroma interspersed with ganglion cell clusters, and the acellular neuropil typical of Schwannian stroma-poor neuroblastoma.

Interestingly, the model showed varying degrees of emphasis on different cellular morphologies within the tumor. While consistently recognizing small round blue cells, its attention to larger, wreath-like multinucleated tumor cells was less uniform, particularly for MYCN status characterization. This variability suggests that certain cellular subtypes or morphological variations might carry different weights in determining tumor characteristics or behavior. The analysis also revealed that the model’s focus was not evenly distributed across tumor areas. Instead, it prioritized regions with complex cellular arrangements, such as the interface between neuropil and small round blue cells, or areas with distinctive vascular patterns. This non-uniform attention to different histological features implies that certain microenvironmental patterns within the tumor may be more indicative of its biological behavior than others.

The model’s focus on specific cellular arrangements and stromal–parenchymal interactions suggests that these features may have greater biological significance than currently recognized in conventional pathological assessments. This approach opens avenues for further investigation into novel morphological features or subtypes within neuroblastoma tumors, potentially leading to more nuanced classification systems and improved understanding of tumor biology.

We show the feasibility of using small datasets of H&E-stained WSIs to develop models for morphologic classification of NTs and assessment of MYCN-amplification status at diagnosis using an aMIL deep learning model. Although the model showed ability to identify MYCN-amplification, its performance on other important genomic features remains to be evaluated in future studies. While prior deep learning models for NTs relied heavily on morphological feature extraction and labeled data, our method used unlabeled data in conjunction with SSL methods to improve model performance when working with a small dataset10,11. The model achieved notable performance in identifying diagnostic category and an ability to identify MYCN-amplification. The accurate and automatic classification model will likely be refined to eventually streamline pathologist workflows as performance on rarer disease subtypes requires further validation with larger, more diverse datasets that contain robust numbers of all relevant features enabling predictions of all relevant histologic features.

The model’s ability to identify MYCN-amplification status from histology is an encouraging result, particularly given the limited data used to train the model. This suggests models could also be built to predict other relevant genomic features such as copy number variations and ploidy, though we were unable to evaluate this as the data were not available. As 50% of high-risk NTs do not harbor MYCN-amplification and typically have other findings such as 11q aberrations, a deep learning approach may also provide the ability to readily identify features that drive aggressive growth in non-MYCN-amplified high-risk tumors19. Unlike immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization where a single gene aberration is probed, deep learning models analyze the image at a global level and may be able to more readily identify morphological signatures produced by combinations of gene alterations that could further aid in stratifying NTs.

Limitations of this study arise largely from data availability. As NTs are rare, it remains difficult to collect sufficient samples to train a robust deep learning model. We acknowledge that the small dataset size may raise concerns about overfitting. To address this, our approach employs domain-specific pre-training, cross-validation, and single-shot external testing. However, we recognize that the model could further be improved with more data. Additionally, our study was limited in its ability to differentiate between the various subtypes of neuroblastoma, which is a more challenging and clinically relevant task than distinguishing neuroblastoma from ganglioneuroblastoma, and could significantly impact risk stratification. Furthermore, we were unable to develop models to identify ALK variants or for clinical prognostication due to the unavailability of the data. While these results are promising, larger multi-institutional studies are needed to fully validate the model’s performance across all NT subtypes and molecular features. Ultimately, this study seeks to aid molecular pathology diagnostics and does not constitute a pathologist replacement. The model’s predictions act as a second pair of eyes and could alert a pathologist to review specific, notable aspects of the histology.

This work provides an important step forward in automating diagnosis and precise classification of NTs with the addition of deep learning-based image analysis. Ultimately, this has the potential to increase global access to molecular and pathological classification for tumors in regions without access to experts. We also demonstrate the ability of aMIL models to perform well on small datasets; this model architecture could be extended to other rare cancers that suffer from low data availability. With further validation, this artificial intelligence-based approach establishes another data modality in the pathologist’s toolbox for NT classification.

Methods

Dataset description

H&E-stained slides from the time of initial diagnosis were obtained from the University of Chicago (n = 102), the Children’s Oncology Group (n = 70), and Lurie Children’s Hospital (n = 25). The images were reviewed by trained pathologists (H.S., P.P., N.C., A.H., K.D.) who annotated the tumor regions and defined the diagnostic category (ganglioneuroblastoma/neuroblastoma), grade (differentiating/poorly differentiating), and MKI (low/intermediate and high). MYCN status was abstracted from patient records (amplified/non-amplified). Due to the rarity of some NT subtypes, our dataset does not include all possible tumor types, which may limit the model’s generalizability. This study was approved by the University of Chicago (IRB20-0659) and Lurie Children’s Hospital Internal Review Boards (IRB 2021-4498). Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from participants or their parent or legal guardian.

Image processing

WSIs were captured using an Aperio AT2 DX WSI Scanner. To remove normal background tissue and maximize cancer-specific training, image tiles were extracted from within regions of interest that were automatically generated from a pre-trained tumor versus non-tumor model previously trained on Pan-Cancer TCGA data. ROIs were verified with expert pathologist assessment and compared to manual efforts. Image tiles from the automated ROIs were extracted from WSIs with a width of 302 μm and 299 × 299 pixels using Slideflow version 2.3.1 and the libvips backend. Grayspace filtering, Otsu’s thresholding, and Gaussian blur filtering (sigma = 3, threshold = 0.02) were used to remove background.

Classifier training

Extracted tiles were converted into feature vectors using UNI15. Bags of 256 randomly selected features were chosen amongst the total feature set and aMIL models were trained on these feature bags in Slideflow with the FastAI API and Pytorch. The aMIL model parameters were: weight decay of 1e−5, bag size of 256, batch size of 32, and training for 10 epochs. aMIL models were evaluated with threefold cross-validation stratified by outcome such that each fold had a balance of class 1 and class 2 outcomes and by calculating the average AUROC, AUPRC, sensitivity, specificity, and F-1 score. Patients were excluded from a given model if the measure of interest was unknown.

All hyperparameters were selected on the training set and held constant for the test set. A standard prediction threshold of 0.5 for calculations of metrics to avoid biasing the study in the setting of relatively limited sample size. Performance metrics, including accuracy, AUROC, AUPRC, sensitivity, specificity, and F-1 score, were calculated for both the training and external test datasets. For each metric, 95% confidence intervals were computed using a bootstrapping approach with 1000 iterations. This method involves resampling the data with replacement, recalculating each metric, and determining the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrapped distribution. This approach provides robust estimates of uncertainty around each performance metric, accounting for the variability in the underlying data.

Model validation

All hyperparameters were determined from 3-fold cross validation within the training cohort. The final, locked aMIL model was trained across the entire training cohort and was evaluated on the entire unseen external test dataset. Samples were evaluated in one run without any hyperparameter tuning on test data to ensure no validation leakage. Model performance was assessed as above. Due to the limited availability of certain tumor subtypes in our external validation set, some performance metrics could not be calculated for all categories.

Pathologist explainability assessment

Explainability heatmaps were generated using attention mapping techniques applied to the model’s predictions. Expert pathologists (P.P., N.C., A.H.) independently reviewed these heatmaps to assess the regions and features that the model identified as important for outcome prediction. The pathologists examined the heatmaps alongside the original H&E-stained images, focusing on cellular morphologies, stromal composition, vascular patterns, and overall tissue architecture. They evaluated the correlation between areas of high attention in the heatmaps and known histopathological features associated with neuroblastoma classification and prognosis. This process aimed to provide insight into the model’s decision-making process and to validate whether the model was identifying clinically relevant histological features.

Data availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of the datasets, but all requests will be promptly evaluated based on institutional and departmental policies to determine whether the data requested are subject to intellectual property or patient privacy obligations. The University of Chicago, Children’s Oncology Group, and Lurie Children’s Hospital datasets can only be shared for non-commercial academic purposes and will require a data user agreement.

Code availability

This code relies extensively on the open-source software package Slideflow, version 2.3.1, which is available at https://github.com/slideflow/slideflow. The code used for this experiment can be found at https://github.com/siddhir/NB_histology.

References

Campbell, K. et al. A comprehensive analysis of neuroblastoma incidence, survival, and racial and ethnic disparities from 2001 to 2019. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 71, e30732 (2024).

Irwin, M. S. et al. Revised neuroblastoma risk classification system: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 3229–3241 (2021).

Sokol, E. et al. Age, diagnostic category, tumor grade, and mitosis-karyorrhexis index are independently prognostic in neuroblastoma: an INRG project. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 1906–1918 (2020).

Pinto, N. R. et al. Advances in risk classification and treatment strategies for neuroblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 3008–3017 (2015).

Thompson, D. et al. Identification of patient subgroups with markedly disparate rates of MYCN amplification in neuroblastoma: a report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group project. Cancer 122, 935–945 (2016).

Shimada, H. et al. The international neuroblastoma pathology classification (the Shimada system). Cancer 86, 364–372 (1999).

Qaiser, T. et al. Usability of deep learning and H&E images predict disease outcome-emerging tool to optimize clinical trials. npj Precis. Oncol. 6, 1–12 (2022).

Hu, J. et al. Prediction of clinicopathological features, multi-omics events and prognosis based on digital pathology and deep learning in HR+/HER2− breast cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 15, https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-23-445 (2023).

Liang, J. et al. Deep learning supported discovery of biomarkers for clinical prognosis of liver cancer. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 408–420 (2023).

Kong, J. et al. Computer-aided evaluation of neuroblastoma on whole-slide histology images: classifying grade of neuroblastic differentiation. Pattern Recognit. 42, 1080–1092 (2009).

Gheisari, S., Catchpoole, D. R., Charlton, A. & Kennedy, P. J. Convolutional deep belief network with feature encoding for classification of neuroblastoma histological images. J. Pathol. Inform. 9, 17 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Transformer-based unsupervised contrastive learning for histopathological image classification. Med. Image Anal. 81, 102559 (2022).

Ilse, M., Tomczak, J. & Welling, M. Attention-based deep multiple instance learning. Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, vol 80, pp. 2127–2136 (2018).

Dolezal, J. M. et al. Slideflow: deep learning for digital histopathology with real-time whole-slide visualization. BMC Bioinform. 25, 134 (2024).

Chen, R. J. et al. Towards a general-purpose foundation model for computational pathology. Nat. Med. 30, 850–862 (2024).

Deng, J. et al. ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 248–255 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848 (2009).

Filiot, A. et al. Scaling self-supervised learning for histopathology with masked image modeling. Published online September 14, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.21.23292757

Dolezal, J. M. et al. Deep learning generates synthetic cancer histology for explainability and education. npj Precis. Oncol. 7, 1–13 (2023).

Luttikhuis, M. E. et al. Neuroblastomas with chromosome 11q loss and single copy MYCN comprise a biologically distinct group of tumours with adverse prognosis. Br. J. Cancer 85, 531–537 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Early Scientific Training Program to Prepare for Research Excellence Post-Graduation (BEST-PREP; S.R.), University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine Summer Research Program (S.R.). Also supported by the National Institutes of Health P30CA014599 which provided funding for the analysis and supports the Human Tissue Research Core at the University of Chicago. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Children’s Oncology Group, the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers U10CA180886, U24CA196173, and U10CA180899. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health. We would like to thank Dr. Lynn Yee for facilitating the inter-institutional exchange of H&E-stained slides.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Siddhi Ramesh (S.R.): conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and writing—reviewing and editing. Emma Chancellor Dyer (E.C.D.): writing–original draft, visualization, software. Monica Pomaville (M.P.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Kristina Doytcheva (K.D.): writing—histology review, reviewing and editing. James Dolezal (J.D.): writing—reviewing and editing. Sara Kochanny (S.K.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Rachel Terhaar (R.T.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Casey J Mehrhoff (C.J.M.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Kritika Patel (K.P.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Jacob Brewer (J.B.): writing—formal analysis, reviewing and editing. Benjamin Kusswurm (B.K.): writing—formal analysis, reviewing and editing. Hiroyuki Shimada (H.S.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Arlene Naranjo (A.N.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Peter Pytel (P.P.): writing—histology review, reviewing and editing. Nicole A CIpriani (N.C.): writing—histology review, reviewing and editing. Aliya N Husain (A.H.): writing—histology review, reviewing and editing. Elizabeth A Sokol (E.A.S.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Susan L Cohn (S.L.C.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Rani E George (R.E.G.): writing—data curation, reviewing and editing. Alexander T Pearson (A.T.P.): writing—methodology, reviewing and editing. Mark A Applebaum (M.A.A.): writing—conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, Writing—reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.R. is the Chief Scientific Officer of Slideflow Labs. J.D. is the Chief Executive Officer of Slideflow Labs. B.K. is a current employee of YouTube. J.B. is an employee of Milliman. S.L.C. reports consulting fees from US WorldMeds. A.T.P. reports consulting fees from Prelude Biotherapeutics, LLC, Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Elvar Therapeutics, Abbvie, and Privo, and contracted research with Kura Oncology, Abbvie, and EMD Serono. A.T.P. is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Slideflow Labs. All other authors report no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramesh, S., Dyer, E., Pomaville, M. et al. Artificial intelligence-based morphologic classification and molecular characterization of neuroblastic tumors from digital histopathology. npj Precis. Onc. 8, 255 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00745-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00745-0

This article is cited by

-

Similarity-guided swarm of models: enhancing semi-supervised learning in computational pathology

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Multiscale tumor characterization in histopathology via self-distilled transformers and topology-aware visual encoding

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Accurate prediction of disease-free and overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer using patient-level multimodal weakly supervised learning

npj Precision Oncology (2025)