Abstract

Tumor genomic profiling is often limited to one or two timepoints due to the invasiveness of tissue biopsies, but longitudinal profiling may provide deeper clinical insights. Using ctDNA data from IMpower150 study, we examined genetic changes in metastatic non-squamous NSCLC post-first-line immunotherapy. Mutations were most frequently detected in TP53, KRAS, SPTA1, FAT3, and LRP1B at baseline and during treatment. Mutation levels rose prior to radiographic progression in most progressing patients, with specific mutations (SPTA1, STK11, KEAP1, SMARCA4, TBX3, CDH2, and MLL3) significantly enriched in those with progression or nondurable response. However, ctDNA’s role in detecting hyperprogression and pseudoprogression remains uncertain. STK11, SMARCA4, KRAS, SLT2, and KEAP1 mutations showed the strongest correlation with poorer overall survival, while SMARCA4, STK11, SPTA1, TBX3, and KEAP1 mutations correlated with shorter progression-free survival. Overall, longitudinal liquid biopsy profiling provided valuable insights into lung cancer biology post-immunotherapy, potentially guiding personalized therapies and future drug development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) comprises a diverse spectrum of malignancies with different subtypes1. Despite advances in therapeutic approaches, a substantial proportion of NSCLC cases experience disease progression2,3, highlighting the need for more effective interventions. Also, the clinical and biological heterogeneity of NSCLC poses a barrier to achieving improved outcomes with novel therapies4. To overcome these challenges, there is a pressing need for clinically applicable tools, and precision medicine applications utilizing next generation sequencing, for enhancing the stratification of NSCLC patients and refining treatment strategies5,6,7.

Clinical sequencing of cancer genomes predominantly relies on tissue samples collected at a single snapshot time point (usually for diagnostic purposes before initiating treatment)8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 although biopsy samples are occasionally collected at the time of disease progression17. The advent of liquid biopsies, particularly circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), introduces a non-invasive method for detecting molecular changes associated with tumors18. Research has shown the feasibility of ctDNA profiling as a diagnostic tool, particularly valuable in guiding treatment decisions for targeted therapies19,20,21. Recent progress has expanded the range of potential applications for ctDNA, including predicting clinical outcomes, detecting minimal residual disease, and treatment monitoring, etc22,23,24,25,26,27.

The non-invasive nature of ctDNA sampling also allows for the collection of multiple samples over time for a patient, facilitating a true longitudinal study of the evolution of molecular alterations. Research have been conducted to evaluate genetic characteristics and therapeutic significance of newly identified circulating tumor DNA alterations in NSCLC following targeted therapies16,28,29. These studies uncovered that serial liquid biopsies offer real-time insights into tumor genetics and heterogeneity in NSCLC.

For NSCLC, although extensive research in ctDNA has been performed, the existing literature has predominantly centered on its diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive roles30,31,32,33. The longitudinal evolution of tumor genetic characteristics in NSCLC following immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment remains underexplored.

Hence, we conducted a comprehensive, longitudinal genomic profiling using ctDNA data from the large IMpower150 phase 3 clinical trial to characterize the changes of genetic characteristics in ctDNA over time in 1 L NSCLC patients following the treatment of chemoimmunotherapy. Molecular progression was characterized by various radiographic progression types, including hyperprogression, progressive disease, nondurable response, and pseudoprogression. Additionally, we hypothesize that temporal changes in peripheral ctDNA (e.g., the rise of ctDNA burden from nadir) across different mutations reflect the tumor size change following treatment and can potentially predict PFS and OS. Therefore, the clinical significance of genetic progression was explored (e.g., their associations with survival outcomes).

Methods

Study and patient population

Following the acquisition of ethical clearance from site-specific committees in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, a retrospective analysis was performed on anonymized data from 466 participants who underwent repeated ctDNA testing in the IMpower150 trial (NCT02366143). The IMpower150 trial is a landmark phase III study that evaluates the combination of atezolizumab (a PD-L1 inhibitor), with bevacizumab (an anti-VEGF drug), and chemotherapy (carboplatin and paclitaxel) in treating 1 L metastatic NSCLC. Participants were chemotherapy-naive individuals with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1. Required criteria for enrollment also included having tumor tissue amenable to biomarker testing, eligibility for bevacizumab, and any level of PD-L1 expression. Patients with EGFR or ALK mutations needed to have experienced disease progression after at least one targeted therapy. Participants were randomly divided into three groups in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive either ACP (atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin, paclitaxel), BCP (bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin, paclitaxel), or ABCP (atezolizumab plus BCP) for eight 3-week cycles. The primary goals were to determine if this combination therapy could extend progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients compared to those receiving only bevacizumab and chemotherapy. Details of the study design are described elsewhere34,35.

ctDNA sample collection, sequencing, and analysis

ctDNA sample collection and sequencing are detailed elsewhere30. Briefly, baseline and on-treatment ctDNA samples were collected for the NSCLC patients using a custom 330 kb assay targeting mutations in 311 genes. After excluding patients without detectable ctDNA (zero mutations detected) at baseline, the dataset included 393, 376, 326, 314, and 226 ctDNA evaluable patients on the baseline, C2D1 (Week 3), C3D1 (Week 6), C4D1 (Week 9) and C8D1 (Week 21), respectively. Details of ctDNA sample collection, processing, and development of the ctDNA assay were described elsewhere30,36,37. Briefly, baseline and on-treatment plasma samples were analyzed separately. The baseline plasma samples underwent retrospective analysis using a previously established assay method36. Subsequent on-treatment samples were then assessed with a custom 330 kb assay targeting mutations in 311 genes37. To construct the assay’s hybrid capture panel, alterations detected in baseline samples were combined and refined, excluding known germline variants, CHIP genes (TET2, DNMT3A, CBL, PPM1D, CHEK2, JAK2, ASXL1, SF3B1), noncoding variants, and repetitive regions with <100× coverage. At least 20 ng of extracted cfDNA was required for sequencing a sample.

Radiographic tumor assessment and types of progression

Patients were monitored with radiographic tumor evaluations using CT scans to identify disease progression, as defined by RECIST v1.1 criteria38, or until no further clinical benefit was observed. For those who persisted with atezolizumab treatment beyond the initial progression, assessments continued. These imaging studies were conducted at the initial screening and subsequently at six-week intervals starting from the first day of the first cycle for up to 48 weeks. Subsequently, imaging was performed every nine weeks thereafter.

The tumor was evaluated based on standard response categories: complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). A durable response is defined as those who achieved response at Cycle 3 Day 1 (C3D1; Week 3) and maintained the response status at every time point throughout C8D1 (the last available time point for response assessment in the dataset), whereas nondurable response is defined as initially tumor response to therapy (PR or CR), but progression (PD) on subsequent imaging scans.

Progressive disease is defined as an increase of more than 20% in the size of target lesions from the previous imaging scan (PD), without evidence of tumor response before or after. Hyperprogressive disease is defined as disease progression at the first evaluation (C3D1) with a change in lesion size exceeding 50%39. Pseudoprogression is characterized by the initial appearance of disease progression on imaging scans, followed by subsequent tumor response during later assessments40.

Molecular progression

Molecular progression is defined as a greater than 20% increase in ctDNA levels measured as tumor molecules per milliliter of plasma (TMPMP) compared to the lowest level (nadir) recorded in previous measurements. The TMPMP for each variant was quantified as (number of mutant copies/DNA input for sequencing (ng)) × (cfDNA concentration (ng/mL plasma))41.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test or χ2 test was used to examine differences in the frequency of molecular progression of gene mutations across various response/progression categories. The relationships between OS/PFS and molecular progression for mutations in 311 genes were evaluated at the C8D1 landmark (the final ctDNA assessment time point) using Cox proportional hazards models implemented in the “survival” package42. Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival curves were generated and plotted for individual gene mutations, stratified by the presence or absence of molecular progression. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.3.

Results

Evolution of genomic landscape in 1 L NSCLC following immunotherapy

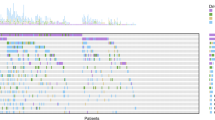

The median number of variants detected per baseline sample was 4. At baseline, the top 10 frequently observed gene mutations were TP53, KRAS, SPTA1, FAT3, LRP1B, STK11, KEAP1, EGFR, SMARCA4, and PRPRD (Fig. 1A). The order of frequencies within the top 10 mutations remained largely consistent at both C2D1 and C3D1. However, GRIN2A and PIK3CG mutations emerged as part of the top 10 gene mutations at C8D1. TP53 mutations consistently remained the most frequently observed genetic alteration throughout the treatment course. While the frequency of TP53 mutations showed a slight decrease from 54% at baseline to 31% at C4D1, it slightly rebounded to 34% at C8D1 (Fig. 1B). At C8D1, the prevalence of EGFR alterations increased, while frequencies of KRAS, KEAP1, and STK11 mutations continued to decrease during the treatment.

A Oncoprints of the top 10 most prevalent mutations in ctDNA at Baseline, C2D1, C3D1, C4D1, and C8D1. B Longitudinal change in frequencies of top mutations over time. C Longitudinal change in ctDNA levels (log-transformed tumor molecules per milliliter of plasma (Log(TMPMP))) over time for top gene mutations.

Various evolution patterns were observed for the TMPMP levels of different gene mutations (Fig. 1C). The average levels of TP53, KRAS, SPTA1, FAT3, KEAP1, SMARCA4, and EPHA5 alterations decreased during the first 3 cycles (9 weeks), but rebounded at C8D1 (Week 21). The levels of STK11 and LRP1B mutations decreased and appeared to be maintained. The levels of EGFR mutations substantially decreased during the first 6 weeks but quickly rebounded afterward. On the other hand, PRPRD mutations showed a decrease during the first 3 weeks after treatment but steadily increased afterward.

Compare mutation levels prior to the first progression

We evaluated the temporal change in levels of different gene mutations prior to the first radiographic progression following treatment for patients with progressive disease (Supplementary Fig. 1) or nondurable response (Supplementary Fig. 2). It is interesting to note that following immunotherapy, ctDNA levels were generally reduced compared to baseline. However, the rise of ctDNA from on-treatment nadir was observed in most patients with progressive disease (68%; Supplementary Fig. 1) or nondurable response (78%; Supplementary Fig. 2) prior to the initial radiographic progression.

Dissect the molecular progression in radiographic progression

In this study, we defined molecular progression as a ≥20% increase in mutation levels over the nadir observed in earlier time points. The molecular progression of TP53 mutations is the most prevalent, followed by SPTA1, FAT3, LRP1B, and KRAS mutations (Fig. 2A). Additionally, progression of STK11, KEAP1, GNAS, SMARCA4 and EGFR mutations exceeds 5%. Notably, there’s no statistically significant difference in molecular progression across different treatment arms. In the comparison of durable response with progressive disease or nondurable response, mutations in TP53, FAT3, KRAS, GNAS, and BRAF exhibit similar molecular progression rates (Fig. 2B). Conversely, progression of SPTA1, KEAP1, STK11, SMARCA4, TBX3, CDH2, and MLL3 mutations are significantly enriched in progressive disease or nondurable response (P < 0.05). While lacking statistical significance, the progression of mutations in EGFR, EPHA5, PTPRD, GRIN2A, ERBB4, SLIT2, and EPHA6 is at least doubled in frequency among patients with progressive disease or nondurable response compared to patients with durable response.

A Proportions of molecular progression for gene mutations in different treatment arms. B Comparison of molecular progression proportions between patients with durable response and progressive or nondurable response. C Comparison of molecular progression proportions between patients with progressive disease and nondurable response. D The trajectories of tumor molecules per milliliter of plasma of mutations of some progressive and nondurable response patients. The dotted line represents the time before the first PD, and the solid line represents the time after the first PD.

Compared to the nondurable response, the progression of mutations in KEAP1, LRP1B, STK11, KRAS, GNAS, RBM10, and WT1 appears to be more pronounced in patients with progressive disease (Fig. 2C). In contrast, progression of EGFR, MLL3, EPHA6, ERBB2, GABRA6, and NOTCH3 mutations appear more common in nondurable response than in progressive disease. Figure 2D shows several examples of the evolution of genomic profiles in patients with progressive disease and nondurable responses.

Molecular kinetics in potential radiographical hyperprogressors and pseudoprogressors

Observations of potential hyperprogressive disease (HPD) were noted in three patients, where the sum of target lesions’ major diameters increased by ≥50% between baseline and the initial radiologic evaluation at Week 6 (C3D1) (Fig. 3A). All three patients had short OS, ranging from approximately 4 months to 7 months. However, molecular progression in ctDNA levels was only observed in HPD#1, while the ctDNA levels appeared to decrease in the other two HPD patients (Fig. 3A).

A Dynamics of the sum of long diameter of tumors in HPD at baseline and week 6 and dynamics of the median of TMPMP in the HPD patients. B Changes in individual mutations for the HPD patients at baseline and week 3. C The trajectories of individual mutations and ctDNA concentrations according to the median of TMPMP in the pseudoprogression patient.

Notably, for HPD#1, the progression of STK11, KRAS, and SMARCA4 mutations exceeded >400% from baseline. HPD#2 showed only mutations in TP53 and CTNNA1 detection, with levels of both genes decreasing from baseline despite radiographic progression. Similarly, HPD#3 displayed a decrease in ctDNA concentrations for all detectable mutations (Fig. 3B).

Among the ctDNA evaluable NSCLC patients, only one potential pseudoprogression was observed (Fig. 3C). Radiographic progression occurred at the initial tumor assessment at Week 6, maintaining at the subsequent assessment at Week 12. However, tumor response was achieved by Week 18 and sustained through Week 24. Unfortunately, ctDNA was undetectable in this patient, and the dynamic of ctDNA concentrations over time is unavailable. Exploratory analysis showed that the 73 patients with undetectable ctDNA exhibited similar disease control rates (SD + PR + CR), but improved OS compared to those with detectable ctDNA (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Association between molecular progression and survival outcomes

Progression of mutations in KRAS, PDGGRA, HSD3B1, U2AF1, and GRM3 are specifically associated with OS but not PFS, indicating they may offer prognostic information for survival rather than disease progression (Fig. 4A). Conversely, progression of mutations in TP53, CDH2, SMO, ERBB2, CDKN2A, PIK3C2B, EPHB1, and EZH2 are linked with PFS but not OS, suggesting they may provide insights into disease progression rather than overall survival. Progression of several mutations, including SPTA1, KEAP1, STK11, EGFR, SMARCA4, TBX3, SLIT2, and EP300, are associated with both PFS and OS.

A All significant genes (P < 0.05) with mutations present in at least 3 patients. B Kaplan–Meier (KM) plots for OS for the top 5 significant genes (P < 0.05) with mutations present in at least 5 patients. The genes in the KM plots are ordered by their P-values, from lowest to highest. C KM plots for PFS for the top 5 significant genes (P < 0.05) with mutations present in at least 5 patients. D Forest plot of the OS hazard ratios (HR) for the top 10 significant genes (P < 0.05) with mutations present in at least 5 patients. The genes in the forest plot are ordered by their estimated HR, from highest to lowest. E Forest plot of the PFS HR for top 10 significant genes (P < 0.05) with mutations present in at least 5 patients.

The top 5 gene mutations whose molecular progression demonstrated the strongest correlation with OS, based on the smallest p-values, include STK11, SMARCA4, KRAS, SLT2, and KEAP1 (Fig. 4B). For PFS, the top 5 gene mutations with the strongest association are SMARCA4, STK11, SPTA1, TBX3, and KEAP1(Fig. 4C). Among significant mutations for OS, progression of STK11 demonstrates the highest hazard ratio (log(HR) = 0.98; 95% CI = 0.56–1.4), followed by SLT2, SMARCA4, TBX3, and PDGFRA (Fig. 4D). For PFS, the progression of SMARCA4 mutations present the highest log(HR) (1.15; 95% CI = 0.62–1.68), followed by TBX3, SLT2, STK11, and SMO (Fig. 4E).

Supplementary Table 1 shows the associations between molecular progression and survival outcomes of all the studied variants.

Discussion

Immunotherapy has revolutionized lung cancer treatment, with breakthroughs like immune checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and atezolizumab, etc.) showing remarkable efficacy, particularly in PD-L1 positive patients43,44. Despite the notable progress, precision medicine in lung cancer faces ongoing challenges stemming in part from the complex evolution of tumor biological processes under the selective pressure of immunotherapy that cannot be easily captured through traditional, single-time-point snapshot tumor biopsies45. Liquid biopsies offer the ability not only to monitor tumor burden but also the molecular characteristics of cancer cells following immunotherapy, holding promise in addressing the current shortcomings associated with conventional tissue biopsies19,46,47. Therefore, we performed an in-depth analysis of sequential liquid biopsies taken from 1 L lung cancer patients in the extensive Phase 3 Impower150 to accurately capture the real-time shifts in the genetic landscape during ICI treatment and the distribution of alterations influenced by immunotherapies.

In line with tissue-based genomic profiling48, mutations in TP53 and KRAS emerge as the most frequently detected in NSCLC using liquid biopsies. This finding is also corroborated by recent ctDNA studies49. Additionally, mutations in EGFR, STK11, KEAP1, and SMARCA4 are commonly identified both in tissue and liquid biopsy analyses for NSCLC49. However, it’s worth noting that while genes SPTA1, FAT3, and LRP1B are frequently detected via ctDNA in our analysis, they are not typically identified as top mutated genes in tissue biopsies48. Moreover, mutations in TP53, KRAS, SPTA1, FAT3, and LRP1B genes are also common during ICI treatment in the Impower150 study while the prevalence of PIK3CG and EGFR rebounded on C8D1 after an initial decline.

Molecular progression (i.e., a ≥20% rise in TMPMP level over the nadir) of mutations in tumor suppressor genes such as STK11 and KEAP1, chromatin-modifying gene SMARCA4, and TBX3 are significantly enriched in NSCLC patients with progressive disease or nondurable response. In addition, compared to the nondurable response, the progression of STK11 mutations is more pronounced in progressive disease. Prior research indicates that mutations in STK11, KEAP1, and SMARCA4 can drive both primary resistance and acquired resistance to ICI in lung cancer17,50,51. Our analysis provides additional evidence to support these findings and further suggests that pathways associated with TBX3 may represent another mechanism of resistance to ICI. Directing therapeutic interventions towards these pathways may offer a complementary approach to restoring ICI sensitivity,52,53,54,55. Additionally, our analysis showed heterogeneous mutation dynamics within individual patients, with some mutation levels decreasing and others increasing, indicating possible clonal selection (Fig. 2D). Even mutations with similar trends differed in their rates of change post-immunotherapy, highlighting ctDNA dynamic variability following treatment.

Additionally, leveraging ctDNA kinetics has been proposed as an effective strategy for identifying HPD from pseudoprogression56. In melanoma patients treated with ICIs, ctDNA kinetics could accurately differentiate between pseudoprogression and HPD57. In our study, limitations in data availability prevent us from elucidating the precise role of ctDNA measurements in distinguishing hyperprogression and pseudoprogression. We observed heterogeneous molecular kinetic patterns in the three NSCLC patients exhibiting potential hyperprogressive disease. Furthermore, ctDNA was undetectable in the sole patient with potential pseudoprogression. Consistent with previous reports31, on-treatment ctDNA clearance at the patient level appears to be associated with higher radiographic response rates across different time points (Supplementary Table 2). The sample-level median TMPMP seemed to decrease from C3D1 to C5D1 but increased at later time points (e.g. C9D1) (Supplementary Table 2).

Our analysis further reveals that molecular progression of mutations in STK11, SMARCA4, KRAS, SLT2, and KEAP1 exhibits the strongest correlation with worsening OS, while the progression of SMARCA4, STK11, SPTA1, TBX3, and KEAP1gene mutations had the strongest association with less favorable PFS. These findings are consistent with the observed enrichment of mutations in STK11, SMARCA4, and KEAP1 genes in progressive disease and nondurable response. It is interesting to note that the progression of TP53 mutation is neither enriched in progressive disease and nondurable response nor has a strong association with overall survival in 1 L NSCLC. We also evaluated the association between molecular progression, measured by overall ctDNA (median TMPMP), and clinical outcomes. The overall molecular progression was marginally associated with PFS (HR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.03–1.57, P = 0.03) and OS (HR 1.30, 95% CI: 1.03–1.64, P = 0.03). The association between time to molecular progression and both PFS and OS was weak as well, with Kendall’s tau of 0.09 (P = 0.03) and 0.12 (P = 0.002), respectively. Compared to some mutations, these weaker but significant associations with the overall ctDNA progression suggest heterogeneous predictive values across different mutations.

We compared baseline mutation rates with molecular progression rates across different mutations and found that they generally differ, with progression rates typically lower than baseline mutation rates (Supplementary Fig. 4). This suggests that each provides distinct information. Further analysis of the association between baseline mutation rates and PFS/OS showed minimal overlap in the associated mutations with molecular progression rates. Of the 29 mutations significantly associated with OS and 58 with PFS, baseline mutation rates were significantly associated with OS for only 6 genes (20%) and with PFS for 10 genes (17%) (data not shown). These findings suggest that baseline and molecular progression rates offer distinct prognostic insights.

Altogether, our longitudinal genomic profiling through liquid biopsies suggests heterogeneous ctDNA dynamics across different mutations both within and between patients following chemoimmunotherapy. Evaluating molecular progression rates for different mutations and their associations with clinical outcomes provides valuable clinical insights into the evolving genomic landscape of NSCLC over time. Our findings may carry significant translational implications, shedding light on the mechanisms of treatment resistance to chemoimmunotherapy in NSCLC. This information can guide the development of novel therapies and advance our understanding of lung cancer biology following chemoimmunotherapy.

Data availability

All clinical and ctDNA data are available and can be retrieved from the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA accession EGAS00001006703). To retrieve the dataset, access can be requested through the data request platform (https://vivli.org/) and upon completion of a data use agreement.

References

Herbst, R. S., Morgensztern, D. & Boshoff, C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 553, 446–454 (2018).

Cortellini, A. et al. A reflection on the actual place of osimertinib in the treatment algorithm of EGFR-positive non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Thorac. Dis. 12, 6107–6111 (2020).

Freeman, A. T. et al. Treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer after progression on nivolumab or pembrolizumab. Curr. Oncol. 27, 76–82 (2020).

Wang, M. N., Herbst, R. S. & Boshoff, C. Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 27, 1345–1356 (2021).

Dagogo-Jack, I. & Lennerz, J. K. Personalized diagnostic workflows: the next wave of precision medicine in NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 15, 888–890 (2020).

Krebs, M. G. et al. Practical considerations for the use of circulating tumor DNA in the treatment of patients with cancer: a narrative review. JAMA Oncol. 8, 1830–1839 (2022).

Abbosh, C. et al. Implementing circulating tumor DNA as a prognostic biomarker in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Trends Cancer 10, 643–654 (2024).

Zehir, A. et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med. 23, 703–713 (2017).

Hoadley, K. A. et al. Cell-of-origin patterns dominate the molecular classification of 10,000 tumors from 33 types of cancer. Cell 173, 291–304 (2018).

Yaeger, R. et al. Clinical sequencing defines the genomic landscape of metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell 33, 125–136 (2018).

Campbell, P. J. et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature 578, 82–93 (2020).

Parikh, A. R. et al. Liquid versus tissue biopsy for detecting acquired resistance and tumor heterogeneity in gastrointestinal cancers. Nat. Med. 25, 1415–1421 (2019).

Jamal-Hanjani, M. et al. Tracking the evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 2109–2121 (2017).

Anagnostou, V. et al. Multimodal genomic features predict outcome of immune checkpoint blockade in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Cancer 1, 99–111 (2020).

Anagnostou, V. et al. Evolution of neoantigen landscape during immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 7, 264–276 (2017).

Chmielecki, J. et al. Candidate mechanisms of acquired resistance to first-line osimertinib in EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 14, 1070 (2023).

Ricciuti, B. et al. Genomic and immunophenotypic landscape of acquired resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade in non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 1311–1321 (2024).

Rossi, G. & Ignatiadis, M. Promises and pitfalls of using liquid biopsy for precision medicine. Cancer Res. 79, 2798–2804 (2019).

Heitzer, E. et al. Current and future perspectives of liquid biopsies in genomics-driven oncology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 71–88 (2019).

FDA draft guidance for industry: use of circulating tumor DNA for early stage solid tumor drug development. https://www.fda.gov/media/158072/download (2022).

Vellanki, P. J. et al. Regulatory implications of ctDNA in immuno-oncology for solid tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 11, e005344 (2023).

Vu, P. et al. Total number of alterations in liquid biopsies is an independent predictor of survival in patients with advanced cancers. JCO Precis. Oncol. 4, 192–201 (2020).

Parikh, A. R. et al. Serial ctDNA monitoring to predict response to systemic therapy in metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 1877–1885 (2020).

Parikh, A. R. et al. Minimal residual disease detection using a plasma-only circulating tumor DNA assay in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 5586–5594 (2021).

Cohen, J. D. et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science 359, 926–930 (2018).

Phallen, J. et al. Direct detection of early-stage cancers using circulating tumor DNA. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaan2415 (2017).

Hsiehchen, D. et al. Clinical and biological determinants of circulating tumor DNA detection and prognostication using a next-generation sequencing panel assay. Cancer Biol. Ther. 22, 455–464 (2021).

Chmielecki, J. et al. Analysis of acquired resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in patients with EGFR-mutated advanced non-small cell lung cancer from the AURA3 trial. Nat. Commun. 14, 1071 (2023).

Awad, M. M. et al. Acquired resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2382–2393 (2021).

Assaf, Z. J. F. et al. A longitudinal circulating tumor DNA-based model associated with survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 29, 859–868 (2023).

Anagnostou, V. et al. ctDNA response after pembrolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer: phase 2 adaptive trial results. Nat. Med. 29, 2559–2569 (2023).

Vega, D. M. et al. Changes in circulating tumor DNA reflect clinical benefit across multiple studies of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. JCO Precis. Oncol. 6, e2100372 (2022).

Sivapalan, L. et al. Liquid biopsy approaches to capture tumor evolution and clinical outcomes during cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 11, e005924 (2023).

Socinski, M. A. et al. IMpower150 final overall survival analyses for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy in first-line metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 1909–1924 (2021).

Socinski, M. A. et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 2288–2301 (2018).

Gandara, D. R. et al. Blood-based tumor mutational burden as a predictor of clinical benefit in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with atezolizumab. Nat. Med. 24, 1441–1448 (2018).

Clark, T. A. et al. Analytical validation of a hybrid capture-based next-generation sequencing clinical assay for genomic profiling of cell-free circulating tumor DNA. J. Mol. Diagn. 20, 686–702 (2018).

Litière, S. et al. RECIST-learning from the past to build the future. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 187–192 (2017).

Ferrara, R. et al. Hyperprogressive disease in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors or with single-agent chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 4, 1543–1552 (2018).

Adashek, J. J. et al. Hyperprogression and immune checkpoint inhibitors: hype or progress? Oncologist 25, 94–98 (2020).

Bos, M. K. et al. Comparison of variant allele frequency and number of mutant molecules as units of measurement for circulating tumor DNA. Mol. Oncol. 15, 57–66 (2020).

Survival analysis. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/survival.pdf (2023).

Del Paggio, J. C. IMMUNOTHERAPY cancer immunotherapy and the value of cure. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15, 268–270 (2018).

Pardoll, D. M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 252–264 (2012).

Hsiehchen, D. et al. Genetic features and therapeutic relevance of emergent circulating tumor DNA alterations in refractory non-colorectal gastrointestinal cancers. Nat. Commun. 13, 7477 (2022).

Siravegna, G. et al. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 531–548 (2017).

Ignatiadis, M., Sledge, G. W. & Jeffrey, S. S. Liquid biopsy enters the clinic - implementation issues and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 297–312 (2021).

Collisson, E. A. et al. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 511, 543–550 (2014).

Thompson, J. C. et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor DNA by next-generation gene sequencing as a biomarker of response and survival in patients with advanced NSCLC receiving pembrolizumab-based therapy. JCO Precis. Oncol. 5, 510–524 (2021).

Ricciuti, B. et al. Diminished efficacy of programmed death-(ligand)1 inhibition inSTK11- and KEAP1-mutant lung adenocarcinoma is affected by KRAS mutation status. J. Thorac. Oncol. 17, 399–410 (2022).

Alessi, J. V. et al. SMARCA4 and other SWItch/sucrose nonfermentable family genomic alterations in NSCLC: clinicopathologic characteristics and outcomes to immune checkpoint inhibition. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16, 1176–1187 (2021).

Xue, Y. B. et al. SMARCA4 loss is synthetic lethal with CDK4/6 inhibition in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 10, 557 (2019).

Papillon, J. P. N. et al. Discovery of orally active inhibitors of Brahma Homolog (BRM)/SMARCA2 ATPase activity for the treatment of Brahma related gene 1 (BRG1)/SMARCA4-mutant cancers. J. Med. Chem. 61, 10155–10172 (2018).

Koppula, P. et al. KEAP1 deficiency drives glucose dependency and sensitizes lung cancer cells and tumors to GLUT inhibition. Iscience 24, 102649 (2021).

Kitajima, S. et al. MPS1 inhibition primes immunogenicity of KRAS-LKB1 mutant lung cancer. Cancer Cell 40, 1128–1144 (2022).

Cabel, L. et al. Clinical potential of circulating tumour DNA in patients receiving anticancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15, 639–650 (2018).

Lee, J. H. et al. Association between circulating tumor DNA and pseudoprogression in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 antibodies. JAMA Oncol. 4, 717–721 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (No. 2008085MA09 and 2022AH050703), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11671375).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S.X., Y.Y., and M.Y. contributed to the design of the research. M.Y., X.S.X., and Y.Y. contributed to data acquisition. H.D., M.Y., and X.S.X. contributed to data analysis. X.S.X., H.D., Y.Y., and M.Y. contributed to data interpretation. X.S.X., H.D., M.Y., and Y.Y. wrote the manuscript; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

X.S.X. is an employee of Genmab, Inc. Genmab did not provide funding for this study. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, H., Yuan, M., Yang, Y. et al. Longitudinal genomic profiling using liquid biopsies in metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC following first line immunotherapy. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 5 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00797-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00797-2

This article is cited by

-

Insights into pet-based radiogenomics in oncology: an updated systematic review

European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (2025)