Abstract

This study investigated BRCA1/2 and homologous recombination repair (HR) pathway gene variants in Chinese epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) patients. Germline and somatic variants in 21 HR-related genes were analyzed in 229 patients using a 21-gene ovarian panel and in 141 patients using a 508-gene pan-cancer panel. BRCA1, BRCA2, and HR-related gene mutation rates were 17.9%, 3.5%, and 23.1%, respectively, with TP53 as the most frequent somatic mutation (66.4%). Combined germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutation rates rose to 23.6 and 6.1%. Survival analysis (n = 200) demonstrated longer overall survival (OS) in patients carrying BRCA1/2 or HR mutations. Notably, strategies including likely pathogenic (LP) and variants of uncertain significance (VUS) showed improved OS, especially in BRCA2 and BRCA1/2 somatic carriers. These findings suggest that integrating germline, somatic, and VUS data enhances survival prediction and guides treatment decisions in Chinese EOC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) is one of the leading causes of female cancer worldwide. According to GLOBOCAN 20201, there were 313,959 new cases and 207,252 deaths globally. In China, the incidence of OC has shown a stable increase from approximately 52,100 cases in 2015 to 57,090 cases in 2022, with an alarming rise in death cases from about 22,500 in 2015 to 39,306 in 20222,3,4. OC exhibits the highest mortality rate among female cancers, with a 5-year survival rate of only 38.9%5,6,7.

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) represents the majority (approximately 60%) of OC cases8, with about 22–25% of EOC attributed to the inheritance of germline mutations in cancer predisposing genes9,10. Ovarian cancer predisposing genes include BRCA1, BRCA2, other homologous recombination repair (HR) genes11, mismatch repair (MMR) genes12, and ovarian cancer-related tumor suppressor genes such as TP5313. Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) emphasize the importance of screening high-risk populations for OC and BC (breast cancer) predisposition genes, as this provides carriers with opportunities to reduce their OC and BC risks14,15. Individuals high or moderate penetrance mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, or other HR genes should consider clinical interventions such as regular physical examinations, mammograms or MRI scans, and risk-reducing surgeries such as risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO)16. Furthermore, patients with ovarian cancer who carry mutations in BRCA1/2 or other HR-related genes can potentially benefit from platinum-based agents and PARP inhibitors based on genetic testing results17,18,19,20,21,22,23. BRCA1/2 genes have also demonstrated value in prognosis prediction, as several studies suggest that BRCA1/2 carriers may experience longer survival times24.

There is a considerable diversity of mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, and other genes observed in different populations, indicating the need for comprehensive studies worldwide20,22,25,26. While germline mutation spectrum studies have been conducted in Chinese populations, the mutation spectrum in Chinese populations differs from that of Western populations27,28,29. In contrast, there are relatively few reports on the somatic mutation spectrum30,31.

Since deleterious mutations often indicate pathogenic or likely pathogenic alterations, variants of uncertain significance, which are less harmful, have received less attention32,33. There remains a lack of systematic evaluation regarding the overall impact of all HR-related gene mutations on drug sensitivity and prognosis in EOC patients.

In this study, we present a comprehensive analysis of the germline and somatic mutation spectra in HR-related genes in Chinese ovarian cancer patients. Our primary objective is to explore the correlations between these mutations, drug sensitivity, and prognosis, thereby shedding light on potential implications for clinical management and treatment strategies.

Results

Recruitment and clinical information

A total of 229 ovarian cancer patients were recruited for this study, all of whom underwent panel sequencing of 21 genes. Among them, 141 patients also received panel sequencing of 508 cancer-related genes.

The median age of the patients was 55, ranging from 24 to 62 years. The majority of patients (194, 84.7%) had the pathological subtype of High-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), while the remaining subtypes included Clear Cell Carcinoma (CCC), Endometrioid Carcinoma (EC), Low-grade serous ovarian cancer (LGSOC), Mucinous Carcinoma (MC), SCC, mixed carcinoma, and unspecific carcinoma. Approximately 21% (48/229) of the patients were in the early stage (I or II), while 79% (181/229) were in the late stage (III or IV). It is worth noting that 42.4% (97/229) of the patients had a family history of cancer. All patients received chemotherapy, and 26 of them also received additional PARP inhibitor treatment. Patients under follow-up for a median time of 46.2 months (IQR, 37.2–54.9 months). A total 7 (3.1%) patients were lost to follow-up for PFS, and 89 (39%) patients were lost to follow-up for OS (Table 1).

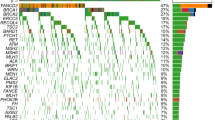

Somatic mutation landscape in 141 patients

Somatic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (Indels) were detected through panel sequencing of both the 21 genes and the 508 genes panel. Among the 141 patients who underwent Oseq-T pan-cancer panel sequencing, TP53 mutations were observed in 72% of patients, followed by BRCA1 mutations in 11% of patients, BRCA2 mutations in 6% of patients, and PIK3CA mutations in 10% of patients (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Within the PIK3CA mutations, specific mutations such as p.E542K, p.E545K, and p.H1047R were detected in 2, 2, and 3 patients, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Additionally, mutations in ARID1A (7% of patients) and NF1 (5% of patients) were also identified.

In our cohort of 229 patients, a significant proportion (23.6%, 54/229) exhibited the presence of germline pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in 21 genes, while 29.7% (68/229) carried variants of uncertain significance (VUS). Specifically, 17.9% of patients carried BRCA1 mutations, 3.5% carried BRCA2 mutations, and 23.1% carried mutations in HR-related genes (Fig. 1A, G). Among these genes, a total of 56 mutations were identified, with BRCA1 (73.2%, 41), BRCA2 (14.3%, 8), and PALB2 (3.6%, 2) being the most prevalent (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, 98.2% (55/56) of the mutations were harbored in homologous recombination repair (HR) genes, while 1.8% (1/56) occurred in STK11 (Fig. 1B). The main mutation types observed in BRCA1 and BRCA2 were both frameshift mutations (Fig. 1C).

A Distribution of pathogenicity of germline mutation carriers. B Distribution of genes with germline deleterious mutations. C Distribution of mutation types of BRCA1 and BRCA2. D Distribution of pathogenicity of somatic mutation carriers. E Distribution of genes with deleterious somatic mutations. F Distribution of mutation types of TP53 and BRCA1. G proportion of germline, somatic, and germline + somatic mutation carriers in genes, HRo refers to HR-related genes other than BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Regarding somatic mutations, 66.4% of patients carried pathogenic or likely pathogenic level mutations (Tier I and II). Among the 207 somatic mutations identified, 73.9% (153) were deleterious mutations in TP53, 6.3% (13) in BRCA1, and 3.4% (7) in BRCA2 (Fig. 1D). Additionally, 8.7% (18) of the deleterious mutations were found in other HR-related genes (Fig. 1E). The main mutation type observed in TP53 was missense mutations (Fig. 1F).

By considering both germline and somatic pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants, the carrier rates of deleterious BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations increased to 23.6% and 6.1%, respectively. Moreover, 35.4% of patients carried at least one germline/somatic deleterious variants in HR-related genes (Fig. 1G).

Ovarian cancer susceptibility gene and prognosis

To assess the clinical significance of variants of uncertain significance (VUS), we implemented two distinct classification strategies. The initial approach, referred to as “LP+” classification, involved categorizing carriers with germline pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants and somatic Tier I/II variants as having deleterious mutations, while the remaining patients were classified as non-pathogenic. The second strategy, known as “VUS+” classification, expanded upon the LP+ classification by including germline VUS and somatic Tier III variants as additional deleterious mutations. Carriers were assigned to the mutation group (Mut, means VUS+/Tier III+), while non-carriers were classified as the wildtype group (WT) (Supplementary Table 4).

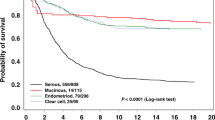

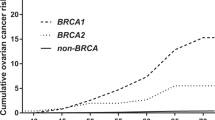

Survival analyses were conducted in 200 patients with primary epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) who had complete follow-up and covariate information. Only genes or gene sets with mutation frequencies greater than 2% were analyzed (Supplementary Table 4). Univariate analysis revealed that under the LP+ grouping strategy, patients with deleterious mutations in BRCA1/2 and HR-related genes (somatic + germline) exhibited prolonged overall survival (OS) (Fig. 2A for HR, Supplementary Fig. 3A for BRCA1/2, p-value: 0.016, 0.027), and a similar but non-significant trend was observed in progression-free survival (PFS) (Fig. 2D for HR, Supplementary Fig. 3B for BRCA1/2, p-value: 0.071, 0.16) compared to non-carriers. In the VUS+ grouping strategy, carriers of HR related genes (Fig. 2B), BRCA2 (Supplementary Fig. 3C) and BRCA1/2 (Fig. 2C) deleterious mutations (somatic + germline) demonstrated extended OS (p-value: 0.002, 0.018, and 0.006, respectively) compared to non-carriers. A similar trend was observed in PFS, although the log-rank test did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2E for HR, Supplementary Fig. 3D for BRCA2 and Fig. 2F for BRCA1/2, p-value: 0.099, 0.1, and 0.41, respectively). Notably, carriers of somatic BRCA1/2 mutations exhibited significantly longer OS than non-carriers (Supplementary Fig. 3E, p-value: 0.047). However, BRCA1 mutations did not significantly impact survival time in terms of OS or PFS under either classification strategy.

Five-year Kaplan‒Meier curve for OS and PFS in EOC patients stratified by A, D germline + somatic mutation carriers of HR genes under LP+ strategy, B, E germline + somatic mutation carriers of HR genes under VUS+ strategy, and C, F germline + somatic mutation carriers of BRCA1/2 genes under VUS+ strategy. The p values were calculated with the log-rank test. WT wild-type (including no variants, benign and likely benign variants), LP+ likely pathogenic and pathogenic variants. VUS+, LP+, and VUS variants. Tier II+, class I and II somatic variants, Tier III+, class I, II, and III somatic variants.

Subsequently, we conducted multivariate survival analysis, adjusting for age, histology, and FIGO stage. In both the LP+ and VUS+ groups, carriers of germline + somatic HR-related mutations demonstrated prolonged OS (Fig. 3A; LP+: p-value = 0.005, VUS+: p-value < 0.001) and PFS (Fig. 3B; LP+: p-value = 0.018, VUS+: p-value = 0.009). Moreover, germline + somatic BRCA1/2 carriers exhibited extended OS (Fig. 3A; LP+: p-value = 0.011, VUS+: p-value = 0.002). Notably, the hazard ratio for BRCA1/2 and HR-related mutation carriers appeared lower in the VUS+ group compared to the LP+ group, a trend that warrants confirmation in independent studies (Fig. 3). For BRCA1/2, the hazard ratio of OS was 0.46 (95% CI: 0.25–0.84) in the LP+ group and 0.41 (95% CI: 0.24–0.72) in the VUS+ group. For HR, the hazard ratio of OS was 0.46 (95% CI: 0.26–0.79) in the LP+ group and 0.43 (95% CI: 0.26–0.70) in the VUS+ group. The hazard ratio of PFS was 0.66 (95% CI: 0.47–0.93) in the LP+ group and 0.65 (95% CI: 0.47–0.90) in the VUS+ group.

Forest plot of hazard ratios for A OS and B PFS associated with LP+ (blue) and VUS+ (red) mutations across individual genes and gene sets. The Cox model was adjusted for age at diagnosis, FIGO stage, and histological subtype. Non-carriers served as the reference group. Hazard ratios are shown with 95% confidence intervals. CI confidence interval, *** p < 0.001; * 0.01 < p < 0.05; †p < 0.1.

Notably, only in the VUS+ group, carriers with germline + somatic BRCA2 or somatic BRCA1/2 mutations demonstrated a significant protective effect on OS (Fig. 3A). The hazard ratio of germline + somatic BRCA2 was 0.27 (95% CI: 0.08–0.85, p-value: 0.026), and for somatic BRCA1/2, it was 0.30 (95% CI: 0.09–0.96, p-value: 0.042). Carriers with germline + somatic ATM exhibited a protective effect on PFS, with a hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% CI: 0.030–1.00, p-value: 0.049), while CDH1 and STK11 showed a hazard effect on PFS (Fig. 3B). The hazard ratio of CDH1 was 3.53 (95% CI: 1.42–8.77, p-value: 0.007), and for STK11, it was 3.11 (95% CI: 1.17–8.22, p-value: 0.022). Additionally, it can be observed that germline + somatic mutation carriers of HR-related genes without BRCA1/2 in the VUS+ group displayed a narrower 95% CI range compared to the LP+ group in terms of overall survival (Fig. 3A; 95% CI: 0.30–1.02 vs. 0.25–1.69, p-value: 0.057 vs. 0.372) and progression-free survival (Fig. 3B; 95% CI: 0.42–0.89 vs. 0.33–1.21, p-value: 0.011 vs. 0.165).

BRCAness mutation and drug sensitivity

We assessed the response rates of patients who underwent platinum-based chemotherapy, comparing mutation carriers to non-carriers. Two patients without information on drug response were excluded from the analysis. Out of the 227 patients included, 190 showed sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy, while 37 exhibited resistance or refractory response.

Under the LP+ grouping strategy, carriers of germline pathogenic variants in HR-related genes demonstrated a significant association with drug response (p-value: 0.029). However, the somatic status of these genes alone did not show a correlation with chemotherapy response. Nevertheless, when germline and somatic pathogenic variants were combined, we observed a significant association between deleterious mutations in BRCA1/2 and HR-related genes and a better treatment response (p-values: 0.015 and 0.004, respectively) (Table 2).

In the VUS+ classification, germline carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA1/2, as well as germline + somatic carriers of BRCA1, BRCA2, and BRCA1/2 mutations, showed a significant correlation with a better treatment response (p-values: 0.044 and 0.006 for germline mutations, 0.018, 0.026, and 0.001 for germline and somatic mutations). Notably, within the VUS+ grouping, 20 carriers of BRCA1/2 VUS were sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy, while none of the VUS carriers exhibited resistance. HR-related somatic and germline + somatic carriers also exhibited a significant association with a better response (p-value: 0.044 for somatic mutation, 0.006 for germline and somatic variants). In this context, the VUS+ classification identified 42 HR-related VUS carriers who showed sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy, while introducing 8 carriers who exhibited resistance (Table 2).

We further conducted a similar analysis among patients who received treatment with the PARP inhibitor Niraparib, leading to notable observations. Within the LP+ classification, individuals harboring germline and somatic pathogenic mutations in BRCA1, and HR genes demonstrated a pronounced increase in sensitivity to Niraparib (p-values: 0.008 and 0.040, respectively). Within the VUS+ classification, a significant association between BRCA1, BRCA1/2 mutations, and drug sensitivity was observed (p-values: 0.040, 0.041) (Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

The landscape of ovarian cancer in our cohort differs from that reported in the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort. One significant reason for this discrepancy is the variation in histological types between the two cohorts. While all samples in the TCGA cohort in report were of high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), our cohort comprised various histological types, with HGSOC accounting for 84.7% of cases. Notably, non-HGSOC samples exhibited a distinct mutation landscape, particularly in the PIK3CA gene, where 67% of mutations occurred in non-HGSOC cases compared to 33% in HGSOC. Additionally, non-HGSOC samples displayed a relatively lower frequency of TP53 mutations.

The distribution of BRCA1/2 mutations varied across different clinical subgroups within our cohort (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7), which included multiple histological types of ovarian cancer. Consistent with previous studies, the prevalence of germline BRCA1/2 mutations ranged from 16.7 to 28.5%, while somatic mutations ranged from 4.1 to 8.7%20,28,29,30,31,34. Our data (20.4% germline, 7.8% somatic) falls within this range. The variation in overall mutation rates across studies can be attributed to the different histological types included in each study22,35,36, as well as discrepancies in variant interpretation among laboratories37,38. Comparing the rates of mutations in HR genes is challenging as well, as there is inconsistency in the gene lists associated with HR-related mutations.

In our study, we observed that BRCA1/2 germline + somatic mutation carriers exhibited an extended OS and HR germline + somatic mutation carriers showed prolonged OS and PFS. Combining germline and somatic mutation information demonstrated improved predictive power compared to using germline or somatic mutations alone. HR-related mutations showed similar or even superior predictive ability compared to BRCA1/2 mutations. Mutations have better protective or worse hazard effect under VUS+ grouping than LP+ grouping. However, it is important to note that the relationship between BRCA1/2 mutations and survival outcomes in ovarian cancer is complex. Studies have reported that BRCA1/2 mutation carriers exhibit longer progression-free survival (PFS)39, or improved overall survival (OS)20, or both. A meta-analysis of 23 studies indicated that BRCA1 mutations are associated with improved OS but not PFS, while BRCA2 mutations do not significantly impact OS or PFS40. Another study conducted in Korea found no difference in OS or PFS between BRCA1 mutation carriers and non-carriers, while BRCA2 mutation carriers had longer PFS33. Factors such as histological type, treatment protocols, and variant interpretation, which were not consistently reported in some studies, can significantly influence survival predictions.

A key aspect of our study is the inclusion of VUS. According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)41, VUS refers to variants with a 6–95% likelihood of being harmful. Previous studies treated VUS carriers similarly to carriers of benign variants. However, our results demonstrate that VUS in BRCA1/2 play a significant role in prognosis and the prediction of platinum-based drug sensitivity. This discrepancy can be attributed to the advancements made in the interpretation of BRCA1/2 variants in recent years. Inter-laboratory comparison studies conducted in 2016 revealed a 5% discrepancy in interpretation for all BRCA1/2 mutations38, whereas a 2020 interpretation comparison in China demonstrated an interpretation accuracy of 99.97% for leading laboratories42.

The prognostic significance of BRCA mutations in platinum-based therapy has been reported in several clinical trials20. Our data corroborates the effects of these mutations in a real-world setting. While the presence of somatic BRCA1/2 mutations alone did not reach statistical significance in predicting chemotherapy response, considering both germline and somatic mutations together demonstrated superior performance. Mutations in HR-related genes also served as predictive markers in chemotherapy. Although they have been reported as prognostic markers in PARP inhibitor treatment, we lacked sufficient carriers in our dataset for validation.

Finally, we acknowledge that p-values reported in our mutation–clinical association and survival analyses were not adjusted for multiple testing. Given the exploratory aim of the study and the limited mutation frequencies in several genes, we prioritized sensitivity to uncover potentially relevant associations. Nonetheless, this increases the possibility of false-positive results, and our findings should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

In conclusion, we observed that carriers of HR-related gene mutations exhibited longer OS and PFS compared to non-carriers. Specifically, BRCA1/2 mutation carriers showed prolonged OS compared to non-carriers. Notably, BRCA2 mutation carriers had longer OS only when variants of uncertain significance (VUS) were taken into consideration. Furthermore, the combination of germline and somatic variants of BRCA1, BRCA1/2, and other HR-related genes significantly improved the prediction ability for prognosis and drug sensitivity in chemotherapy. The presence of VUS in BRCA1/2 gene influenced both survival prediction and chemotherapy sensitivity. Importantly, considering both germline and somatic variants together enhanced the prediction ability for chemotherapy response and PARP inhibitor therapy.

Methods

Ethics approval and patient recruitment

Prior to participation, all patients provided informed consent after being fully informed about the study. The study was conducted in accordance with ethical principles and guidelines. A total of 1411 ovarian cancer patients were recruited for this study during February 24, 2017 and December 31, 2018. After excluding 1182 patients based on our criteria, a total of 229 patients were included for analysis. (Supplementary Fig. 1). These patients received standard treatment and underwent genetic testing. Clinical information, including age, pathological subtype, stage, tumor size and site, and family history, was collected for analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The Institutional Review Board of Peking Union Medical College Hospital approved this study (No. HS-1245 and No. HS-1474). The registration numbers are NCT03015376 and NCT03294343 (clinicaltrials.gov, registered on January 10, 2017 and on September 27, 2017, respectively). The data the first patient was enrolled was February 24, 2017. The Chinese Human Genetic Resources Management Office of the National Ministry of Science and Technology approved this study (Registration no.: [2017] 1901, http://www.most.gov.cn/bszn/new/rlyc/jgcx/index.htm). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Consents for publication have been obtained from all patients.

Treatment and pathological evaluation

Patients were diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) through core needle biopsy, laparoscopic biopsy, or debulking surgeries. Debulking surgeries, consisting of primary or interval surgeries combined with platinum-based chemotherapy, were performed following established guidelines15. Sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy was determined based on the following criteria: sensitive or resistant, indicating recurrence beyond or within 6 months after the completion of standard chemotherapy, respectively; refractory, indicating recurrence within 4 weeks after the completion of standard chemotherapy or disease progression during the chemotherapy duration. Follow-up was conducted until March 1, 2022, with recurrence and/or progression defined as the appearance of new lesions confirmed by imaging evaluation or histology, or increased tumor markers as identified by physicians. Mortality information was obtained from case reports and/or death certificates.

A centralized pathological evaluation was conducted by two independent pathologists to ensure consistency in the assessment of histological subtypes and modification of International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages. The analysis of drug sensitivity and survival outcomes specifically focused on high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) and clear cell/endometrioid subtypes, as different histological types are characterized by distinct mutational spectra43,44,45.

Sample preparation and sequencing

DNA extraction from ovarian cancer tissue and blood samples of patients was performed using the Qiagen DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany)46,47,48,49. The DNA quantity and integrity were assessed using the Qubit Fluorometer (Life Technologies). Qualified DNA samples were subjected to capture-based targeted sequencing using the QseqT ovarian cancer panel (21 genes) or the OseqT pan-cancer panel (508 genes), followed by library construction for the BGISEQ-500 platform. Each sample generated sequencing data with an average sequencing depth of over 500x and target region coverage exceeding 99%.

Variants calling and data interpretation

The sequencing reads were filtered using SOAPnuke 1.5 and aligned to the hg19 reference genome using BWA 0.7.12. Germline and somatic variants were called using GATK 3.4 following the GATK best practice. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) were called using GATK Unified Genotyper, while indels were called using GATK Haplotype. All variants were filtered based on: quality depth >100×; mapping quality (MQ) > 5; no significant strand bias (Fisher’s exact test, p > 0.05); and read position >7 bp from fragment ends.

Variant classification

Variants were annotated using ANNOVAR. The focus of variant interpretation was on 21 genes, including 11 homologous recombination repair (HR) related genes (ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CHEK2, MRE11A, NBN, PALB2, RAD50, and RAD51C), 5 mismatch repair related genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS1, and PMS2), and 5 ovarian cancer related genes (CDH1, MUTYH, PTEN, STK11, and TP53). Germline variants were classified into five categories according to the recommendations of the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG): pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), variants of uncertain significance (VUS), likely benign (LB), and benign (B). Somatic variants were classified into four categories following the guidelines of the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP): tier I (variants with strong clinical significance), tier II (variants with potential clinical significance), tier III (variants of unknown clinical significance), and tier IV (variants deemed benign or likely benign). To ensure consistency between germline and somatic variants, tier I, tier II, and tier III were considered equivalent to P, LP, and VUS, respectively, while tier IV corresponded to B and LB. Variants classified as P or LP were confirmed using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) or Sanger sequencing. The interpretation of certain variants was updated in 2022 based on updated literature evidence. Variant details are included in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.5.1, with the use of the following packages: “rstatix” for univariate statistical testing, “survival” for Cox regression and Kaplan–Meier estimations, and “survminer” for survival curve visualization and log-rank testing. The significance of the association between mutation prevalence and clinical characteristics was assessed using an appropriate method (Chi-square test or Fisher exact test) based on the number of cases.

Time-to-event endpoints included overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). OS was defined as the time from initiation of first-line treatment to death from any cause. PFS was defined as the time from treatment initiation to documented recurrence or progression. Patients without an event were right-censored at the last follow-up or administratively at 60 months, whichever occurred first. Follow-up time was calculated from treatment initiation to censoring or event.

Survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariable Cox proportional-hazards models were applied to assess the association of genetic mutations with OS and PFS. The explanatory variables included: (1) mutation status (germline/somatic BRCA1, BRCA2, BRCA1/2 combined, HR-related genes, non-HR-related genes), (2) age at diagnosis (continuous), (3) histological subtype (serous vs non-serous), and (4) FIGO stage (I–II vs. III–IV). These covariates were selected based on their established prognostic relevance in epithelial ovarian cancer and the availability of complete data in our cohort. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed and met for all variables included in the final models. Given the limited number of mutation-positive cases in certain FIGO and histological strata, interaction terms (e.g., mutation × FIGO stage) were not included avoid model overfitting and instability; only main-effect estimates are reported.

For mutational grouping, germline and somatic variants were analyzed independently to allow for overlapping categorization when both mutation types were present.

Data availability

All data of this study have been contained in the supplementary files.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Xia, C. et al. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin. Med. J. 135, 584–590 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 115–132 (2016).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65, 5–29 (2015).

Zeng, H. et al. Cancer survival in China, 2003-2005: a population-based study. Int. J. Cancer 136, 1921–1930 (2015).

Farmer, H. et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434, 917–921 (2005).

Bryant, H. E. et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 434, 913–917 (2005).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Ovarian cancers: evolving paradigms in research and care. (National Academies Press, 2016).

Walsh, T. et al. Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 18032–18037 (2011).

Jervis, S. et al. Ovarian cancer familial relative risks by tumour subtypes and by known ovarian cancer genetic susceptibility variants. J. Med. Genet. 51, 108–113 (2014).

Venkitaraman, A. R. A growing network of cancer-susceptibility genes. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1917–1919 (2003).

Lynch, H. T. et al. Hereditary ovarian carcinoma: heterogeneity, molecular genetics, pathology, and management. Mol. Oncol. 3, 97–137 (2009).

Walsh, T. et al. Spectrum of mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, and TP53 in families at high risk of breast cancer. JAMA 295, 1379–1388 (2006).

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian and Pancreatic. Version 1.2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf (2019).

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Ovarian Cancer. Including fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer. Version 1.2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf (2020).

Finch, A. et al. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. JAMA 296, 185–192 (2006).

Dougherty, B. A. et al. Biological and clinical evidence for somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 as predictive markers for olaparib response in high-grade serous ovarian cancers in the maintenance setting. Oncotarget 8, 43653–43661 (2017).

Yang, D. et al. Association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with survival, chemotherapy sensitivity, and gene mutator phenotype in patients with ovarian cancer. JAMA 306, 1557–1565 (2011).

Bolton, K. L. et al. Association between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and survival in women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. JAMA 307, 382–390 (2012).

Pennington, K. P. et al. Germline and somatic mutations in homologous recombination genes predict platinum response and survival in ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 764–775 (2014).

Coleman, R. L. et al. Veliparib with first-line chemotherapy and as maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 2403–2415 (2019).

Enomoto, T. et al. The first Japanese nationwide multicenter study of BRCA mutation testing in ovarian cancer: CHARacterizing the cross-sectionaL approach to Ovarian cancer geneTic TEsting of BRCA (CHARLOTTE). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 29, 1043–1049 (2019).

Gonzalez-Martin, A. et al. Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 2391–2402 (2019).

Yao, Q. et al. Mutation landscape of homologous recombination repair genes in epithelial ovarian cancer in china and its relationship with clinicopathlological characteristics. Front. Oncol. 12, 709645 (2022).

Norquist, B. M. et al. Inherited mutations in women with ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2, 482–490 (2016).

Yost, S. et al. Insights into BRCA cancer predisposition from integrated germline and somatic analyses in 7632 cancers. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 3, pkz028 (2019).

Li, A. et al. BRCA germline mutations in an unselected nationwide cohort of Chinese patients with ovarian cancer and healthy controls. Gynecol. Oncol. 151, 145–152 (2018).

Shi, T. et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in ovarian cancer patients from China: ethnic-related mutations in BRCA1 associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 140, 2051–2059 (2017).

Wu, X. et al. The first nationwide multicenter prevalence study of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Chinese ovarian cancer patients. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 27, 1650–1657 (2017).

You, Y. et al. Germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations in 172 Chinese women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Front. Oncol. 10, 295 (2020).

Chao, A. et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of BRCA1/2 germline and somatic mutations in Taiwanese patients with ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 7, 85529–85541 (2016).

Eoh, K. J. et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes of BRCA1/2 pathologic mutation, variants of unknown significance, or wild type epithelial ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Res. Treat. 49, 408–415 (2017).

Seo, J. H. et al. Prevalence and oncologic outcomes of BRCA1/2 mutation and variant of unknown significance in epithelial ovarian carcinoma patients in Korea. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 62, 411–419 (2019).

Bu, H. et al. BRCA mutation frequency and clinical features of ovarian cancer patients: A report from a Chinese study group. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 45, 2267–2274 (2019).

Witjes, V. M. et al. Probability of detecting germline BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants in histological subtypes of ovarian carcinoma. A meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 164, 221–230 (2022).

Sugino, K. et al. Germline and somatic mutations of homologous recombination-associated genes in Japanese ovarian cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 9, 17808 (2019).

Eggington, J. M. et al. A comprehensive laboratory-based program for classification of variants of uncertain significance in hereditary cancer genes. Clin. Genet. 86, 229–237 (2014).

Amendola, L. M. et al. Performance of ACMG-AMP variant-interpretation guidelines among nine laboratories in the clinical sequencing exploratory research consortium. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 1067–1076 (2016).

Kim, S. I. et al. Effect of BRCA mutational status on survival outcome in advanced-stage high-grade serous ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 12, 40 (2019).

Huang, Y. W. Association of BRCA1/2 mutations with ovarian cancer prognosis: an updated meta-analysis. Medicine 97, e9380 (2018).

Nykamp, K. et al. Sherloc: a comprehensive refinement of the ACMG-AMP variant classification criteria. Genet. Med. 19, 1105–1117 (2017).

Shao, K. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of BRCA1/2 variant interpretation ability among laboratories in China. J. Med. Genet. 59, 230–236 (2022).

Berger, A. C. et al. A comprehensive pan-cancer molecular study of gynecologic and breast cancers. Cancer Cell 33, 690–705 e9 (2018).

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474, 609–615 (2011).

Ding, L. et al. Perspective on oncogenic processes at the end of the beginning of cancer genomics. Cell 173, 305–320.e10 (2018).

Li, W., Li, L. & Wu, M. A family pedigree of malignancies associated with BRCA1 pathogenic variants: a reflection of the state of art in China. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 17, 26 (2019).

Li, L., Qiu, L. & Wu, M. A survey of willingness about genetic counseling and tests in patients of epithelial ovarian cancer. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 97, 3412–3415 (2017).

Lee, Y. et al. Advances in the recognition of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: applications to cancer screening and the pathogenesis of ovarian cancer. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 13, 1–7 (2006).

Cheng, A. et al. Pathological findings following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 46, 139–147 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Independent Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Complex, Severe and Rare Diseases in Peking Union Medical College Hospital (2025-I-ZD-001 and 2025-O-ZD-003), by the Key Research Project of Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. Z220013), by the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (No. 2024-I2M-C&T-B-029), by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-B-083, 2022-PUMCH-C-010, 2022-PUMCH-C-022 and 2022-PUMCH-D-003), by the National Key Clinical Specialty Construction Project (No. U114000), and by Peking Union Medical College Hospital Talent Cultivation Program (Category D) (No. UHB12577). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We thank Ms. Yingqi Wang, Ms. Meng Liu, Ms. Shujiao Mu, Ms. Lvzhi Ren, Ms. Yilu Liu, Ms. Rui Wang and Dr. Ke Ma, Dr. Changbin Zhu and Dr Di Shao from BGI Genomics. Their diligent and generous help enabled the smooth progression of this project. Last and most important, we always devote our thanks to our patients and friends.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L., K.S., and M.W. conceived of the original idea for the study, interpreted results, carried out the statistical analysis, edited the paper and was overall guarantor. L.L. and J.Z. obtained ethical approval, contributed to the preparation of the data set, interpreted results and contributed to drafts of the paper. N.S., B.S., D.Z., L.L., Y.G., K.W., Q.L., C.L., H.C., B.C., L.W., K.S., and J.L. contributed to the study design, interpretation of results and commented on drafts of the paper. Specially, J.L. and M.W. from Peking Union Medical College Hospital, N.S. and Y.G. from Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute, D.Z. and Q.L. from Shandong Cancer Hospital and Institute, and Y.L. and Q.L. Peking University devoted their leadership and professional clinical care in this study. Y.Y. and H.W. conducted the pathological evaluation and reviewed the original materials. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Zhang, J., Song, N. et al. Multigene germline and somatic testing for epithelial ovarian cancer in China. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 281 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01074-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01074-6