Abstract

Cancer is a critical global health issue, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In this study, we integrated four additional cohorts to assess the performance and robustness of an AI-empowered blood-based test (named OncoSeek) for multi-cancer early detection (MCED). It included a case-control cohort of symptomatic cancer patients, a prospective blinded study, and two retrospective cohorts conducted on two distinct platforms. Combining these with previously published one training and two validation cohorts, we evaluated OncoSeek’s performance in 15,122 participants (3029 cancer patients and 12,093 non-cancer individuals) from seven centres in three countries, using four platforms and two sample types. OncoSeek showed adequate performance for MCED with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.829, 58.4% sensitivity, 92.0% specificity, and overall accuracy of 70.6% in tissue of origin (TOO) prediction for the true positives. The test could detect 14 common cancer types, accounting for 72% of global cancer deaths, with sensitivities ranging from 38.9 to 83.3%. Additionally, the symptomatic cohort exhibited a high sensitivity of 73.1% at 90.6% specificity, indicating OncoSeek’s potential for cancer early diagnosis. These findings underscore OncoSeek’s consistent performances across diverse populations, platforms, and sample types, offering affordable and accessible multi-cancer early detection, especially for LMICs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer remains a significant global public health challenge. The Global Cancer Observatory (GCO) estimates 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million deaths globally in 20221. Cancer-related deaths in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) constitute 70% of the global annual mortality2. Delays and barriers in accessing cancer care are among the contributing factors that often lead to patients presenting with advanced-stage cancer2. The median delay from symptom appearance to therapeutic care for lung cancers is 43 days in India and 141 days in Turkey3. A meta-analysis of 12 LMICs revealed an average diagnostic delay of 3.3 months in breast cancer4. Delays in definitive diagnosis and treatment can cause patient anxiety, increase costs, and reduce the potential benefits of treatment5,6. Early cancer detection is widely recognised for significantly improving cure rates, increasing 5-year survival, and reducing treatment costs7. Studies suggest that detecting cancer before it reaches stage IV could potentially decrease cancer-related deaths by at least 15% within 5 years8.

However, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) currently endorses screening for only four cancer types: biennial screening mammography for breast cancer9, cervical cytology and/or primary high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) testing for cervical cancer10, as for colorectal cancer, stool-based tests including the high-sensitivity guaiac faecal occult blood test (gFOBT), faecal immunochemical test (FIT), and stool DNA test, along with direct visualisation tests including colonoscopy, CT colonography and flexible sigmoidoscopy11. Additionally, low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) is endorsed for lung cancer screening12. However, the application of these technologies in LMICs faces limitations due to high costs, complexity, and the requirement for sophisticated infrastructure and laboratories13. Yet, effective early detection methods are still lacking for the majority of cancers. Thus, there is an urgent need for an affordable and accessible test that can detect multiple cancer types, thereby enabling more precise clinical assessments and earlier diagnoses.

The application of liquid biopsy in oncology has exploded in the past decade, particularly in cancer early detection, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment14,15. Liquid biopsy has been explored for screening of specific cancer types, including lung16, liver17, colorectal18, and lymphoma19, as well as for multiple cancer types20. In our previous study13, we developed a blood-based test for multi-cancer early detection (MCED), named OncoSeek. By integrating a panel of seven selected protein tumour markers (PTMs) with individual clinical data, and enhanced by artificial intelligence (AI), OncoSeek offers a cost-effective and accessible solution. The multi-centre study, including a training cohort and two validation cohorts, showed OncoSeek’s satisfactory performance and robustness in MCED across nine common cancer types, achieving an overall sensitivity of 51.7% at 92.9% specificity. Study participants were recruited from SeekIn and Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital (SYSMH) in China, and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHUSM) in the USA. OncoSeek was performed on two quantification platforms, Roche Cobas e411/e601 and Bio-Rad Bio-Plex 200.

In this study, we aim to assess the robustness of OncoSeek across more cohorts, platforms, and populations. To achieve this, we integrated four additional validation cohorts, a case-control cohort of symptomatic individuals, a prospective blinded study, and two retrospective case-control cohorts conducted on two distinct platforms. These cohorts consist of the participants from diverse geographic locations, utilising various sample types and platforms for PTM analysis. Furthermore, the symptomatic patient’s cohort allows us to further explore the potential clinical value of OncoSeek in the early diagnosis of cancer.

Results

The consistency of OncoSeek across different laboratories

Considering the diverse origins of study participants and the multiple laboratories involved, variations in sample types, reagents, instruments, and operators were expected. To evaluate the consistency of the results across different centres, we conducted repetitive experiments on a randomly selected subset of samples. Five non-cancer plasma samples from SeekIn underwent the analysis of seven PTMs at SeekIn and Shenyou laboratories both using Roche Cobas e401 analysers. Furthermore, 13 cancer patients’ plasma and serum samples from the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital were assessed for the seven PTMs at SeekIn and Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital utilising Roche Cobas e411 and e601 analysers, respectively. In addition to the differences in laboratory settings and technicians, this validation incorporated two sample types, serum and plasma, performed on two different Roche instruments, Cobas e411 and e601. The results demonstrated a high degree of consistency, as evidenced by the close alignment of all PTM results to the 45-degree dashed line in Fig. 1a, b. The robust linear correlation across different laboratories is underscored by a Pearson correlation coefficient reaching 0.99 (Fig. 1a) and 1.00 (Fig. 1b), indicating the assay’s reliability for both cancer patients and non-cancer individuals.

Participants’ demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics of the study participants, including gender, age, cancer types, and stages, are detailed in Table 1. Following the consolidation of all seven cohorts, the collective group is referred to as the “ALL cohort”. Within this ALL cohort, the median age is recorded at 53 years. The gender distribution is almost equal, with 7704 (50.9%) females and 7418 (49.1%) males. The ALL cohort encompasses a variety of cancer types, 18 cases of bile duct, 311 cases of breast, 8 cases of cervix, 604 cases of colorectum, 5 cases of endometrium, 22 cases of gallbladder, 22 cases of head and neck, 314 cases of liver, 770 cases of lung, 233 cases of lymphoma, 137 cases of oesophagus,106 cases of ovary, 153 cases of pancreas, 259 cases of stomach, and additional 67 cases categorised as other types of cancer (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1).

The cancer detection performance of OncoSeek in four validation cohorts and the ALL cohort

In this study, we evaluated the effectiveness of OncoSeek in detecting cancer across four validation cohorts and the comprehensive ALL cohort. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted to assess OncoSeek’s ability to classify cancer patients from non-cancer individuals (Fig. 2). The area under the curves (AUCs) for the HNCH, FSD, BGI, and PUSH cohorts were 0.883, 0.912, 0.822, and 0.825, respectively. These results were strikingly consistent with those from the three previously reported cohorts, which had AUCs of 0.826, 0.744, and 0.819, respectively13. After combining the seven cohorts into one (the ALL cohort), the AUC was determined to be 0.829. These similar results indicate that OncoSeek maintains excellent consistency across diverse cohorts.

OncoSeek showed high sensitivity and specificity in both symptomatic and prospective blinded cohort, with HNCH and FSD sensitivities of 73.1% (95% CI: 70.0%–76.0%) and 72.2% (95% CI: 46.5%–90.3%), respectively, and specificities of 90.6% (95% CI: 87.9%–92.9%) and 93.6% (95% CI: 87.3%–97.4%), respectively. The BGI and PUSH cohorts, assessed on two distinct quantification platforms, displayed comparable sensitivities of 55.9% (95% CI: 37.9%–72.8%) and 59.7% (95% CI: 51.4%–67.7%), respectively, along with specificities of 95.0% (95% CI: 92.4%–96.8%) and 90.0% (95% CI: 89.0%–91.0%) (Table 2).

Following the integration of the seven cohorts into the ALL cohort, the study included a total of 15,122 participants, comprising 3029 cancer patients and 12,093 non-cancer individuals, from three countries, and performed on four different platforms. In this large cohort, OncoSeek showed a sensitivity of 58.4% (95% CI: 56.6%–60.1%) and a specificity of 92.0% (95% CI: 91.5%–92.5%) (Table 2). Sensitivities vary for different types of cancers, bile duct at 83.3%, gallbladder at 81.8%, endometrium at 80.0%, pancreas at 79.1%, cervix at 75.0%, ovary at 74.5%, lung at 66.1%, liver at 65.9%, head and neck at 59.1%, stomach at 57.9%, colorectum at 51.8%, oesophagus at 46.0%, lymphoma at 42.9%, and breast at 38.9% (Fig. 3a). These cancer types constitute a significant burden, representing over 60% of worldwide cancer cases and more than 72% of cancer-related mortalities1. These findings underscored OncoSeek’s potential as a reliable assay for multi-cancer early detection. Given that breast, cervical, colorectal, and lung cancers are recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for screening with established methods9,10,11,12, we evaluated OncoSeek’s efficacy in identifying ten additional cancer types (bile duct, endometrium, gallbladder, head and neck, liver, lymphoma, oesophagus, ovary, pancreas, and stomach). The assay sustained a specificity of 92% while achieving a sensitivity of 61.4%. Hence, OncoSeek may serve as a valuable adjunct for cancers lacking effective early detection methods. Additionally, sensitivity was observed to increase with advancing clinical stages. At stage I, the sensitivity was 42.8%, rising to 52.1% for stage II, 61.9% for stage III, and peaking at 79.7% for stage IV (Fig. 3b). Subsequently, we evaluated the performance of OncoSeek for nine cancer types with over 100 cancer patients each in the ALL cohort, including breast, colorectum, liver, lung, lymphoma, oesophagus, ovary, pancreas, and stomach. The sensitivities of cancer signal detection for these nine pre-specified cancers were further detailed by individual cancer type and clinical stage in Fig. 3c, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1. To further compare the consistency of sensitivity and specificity for each cancer type, we assumed a rectangular stage distribution for each cancer to calculate stage-standardised sensitivity estimates. However, due to insufficient sample sizes for each specific neoplasia in the BGI, FSD, and PUSH cohorts, and missing stage information in the SYSMH cohort, we selected only three cohorts—SeekIn, JHUSM, and HNCH—for this analysis (Supplementary Table 2). Specificities were similar across these cohorts, with values of 90.0%, 88.9%, and 90.6% for SeekIn, JHUSM, and HNCH, respectively. Moreover, the Kruskal-Wallis test indicated that there were no statistically significant differences in the stage-standardised sensitivity estimates for each cancer type among these three cohorts.

a OncoSeek sensitivity across cancer types. The graph presents sensitivity on the y-axis for various cancer types depicted on the x-axis, with a focus on individual cancer types. The types were arranged in descending order of sensitivity, and the bars represented the 95% confidence interval. The sample size for each cancer type was noted in parentheses. b OncoSeek sensitivity by clinical stage. c OncoSeek sensitivity by stage in the nine pre-specified cancers. Sensitivity was illustrated on the y-axis, and categorised by the clinical stage of cancer on the x-axis. The bars denote the 95% confidence interval, and the sample size for each stage was provided in parentheses.

Predicting affected TOO

A key feature of MCED tests is their ability to identify the tissue of origin (TOO), crucial for directing targeted diagnostic approaches. We evaluated OncoSeek’s ability to identify the TOO for nine prevalent cancers in 1663 cancer cases across the seven cohorts, where cancer signals were detected and the cancer types were confirmed. The overall accuracy of the top two most possible organ systems in the true positives was 70.6% (95% CI: 68.4%–72.7%). Ovarian cancer showed the highest accuracy at 73.4%, followed by lung cancer at 61.5%. Pancreatic and breast cancers both achieved an accuracy of 60.3%. Liver cancer accuracy was 58.5%, lymphoma 51.0%, colorectal cancer 40.9%, and upper gastrointestinal (Upper GI) cancers, combined with oesophageal and gastric, were at 16.4% (Fig. 4).

The confusion matrices illustrate the accuracy of TOO prediction. The matrices display the concordance between the actual tumour origins on the x-axis and the OncoSeek model’s predictions on the y-axis. The colour scheme reflects the proportion of samples with predicted TOO. The analysis included 1663 individuals with confirmed cancer diagnoses and predicted as having cancer at 92.0% specificity. Upper GI upper gastrointestinal, TOO tissue of origin.

Discussion

Identifying cancer at an earlier stage can facilitate more effective treatments, enhancing the quality of life for cancer patients and the survival rates for many types of cancers21. In LMICs, early cancer detection faces numerous challenges, such as limited infrastructure, limited trained personnel, high equipment purchases and maintenance costs, and inadequate training of healthcare providers22,23. The existing cancer screening and treatment services in LMICs are often fragmented. This fragmentation can create barriers for patients, particularly those lacking the necessary knowledge or financial resources to navigate the steps between screening, follow-up, diagnosis, and treatment24. As a result, patients may experience delays in cancer diagnosis, resulting in increased treatment costs and higher mortality rates25,26. Therefore, providing reliable and affordable screening tests, and increasing the utilisation of routine cancer screenings would be beneficial in LMICs23.

In this large-scale clinical study, we introduced OncoSeek, a CE-IVD marked MCED test designed to detect multiple cancer types. By integrating blood-based protein tumour marker analysis with AI algorithms, OncoSeek offers a cost-effective solution at under $25 reagent cost per test, requiring no additional equipment, infrastructure, or technical personnel13. The affordability and accessibility make it more practical for the healthcare providers in LMICs. To further validate the performance of OncoSeek, we conducted the largest MCED clinical study to date, encompassing seven independent cohorts with a total of 15,122 participants. The participants were recruited from seven different centres across three countries, China, the United States, and Brazil. Throughout the study, we utilised two different sample types, plasma and serum, to perform OncoSeek testing on four distinct immunoassay platforms, Roche, Abbott, Bio-Rad, and GBI. As a result, OncoSeek’s performance in cancer detection was well-validated, achieving a sensitivity of 58.4%, a specificity of 92.0%, and overall accuracy of 70.6% in TOO. Sensitivity for detecting fourteen common cancer types varied from 38.9 to 83.3%, including bile duct, breast, cervix, colorectum, endometrium, gallbladder, head and neck, liver, lung, lymphoma, oesophagus, ovary, pancreas, and stomach. These cancers impose a significant burden, accounting for over 60% of global cancer cases and more than 72% of cancer-related mortalities1. The robustness of OncoSeek was further evidenced by its consistent performance across the seven cohorts. The AUCs were as follows: 0.826 for SeekIn, 0.744 for SYSMH, 0.819 for JHUSM, as previously reported13; and 0.825 for HNCH, 0.822 for FSD, 0.883 for BGI, and 0.912 for PUSH, respectively. Galleri, an MCED test utilising next-generation sequencing (NGS), achieved a sensitivity of 51.5% at a specificity of 99.5%20. When adjusted to the same specificity (99.5%), OncoSeek’s sensitivity was 31.0%. Beyond performance metrics, OncoSeek offers notable advantages in cost-effectiveness and turnaround time. While Galleri is priced at $949 in the United States, OncoSeek provides a significantly more affordable alternative (<$25 reagent cost). Additionally, OncoSeek delivers results within 1.5 h, making it substantially faster than NGS-based MCED tests like Galleri, which takes days to complete. To optimise specificity while maintaining adequate sensitivity, we proposed a two-step screening strategy27. OncoSeek serves as the initial screening tool, and the individuals testing positive undergo a secondary test, SeekInCare—an MCED test integrating the seven protein tumour markers with four cfDNA-based genomic features: copy number aberration (CNA), fragment size (FS), end motifs, and oncogenic viruses, using shallow whole-genome sequencing at 3× coverage19,28. This two-step approach enhances specificity from 91.0 to 99.3% while preserving a sensitivity of 51.5%, effectively balancing sensitivity and specificity.

Furthermore, OncoSeek demonstrated a sensitivity of 61.4% for 10 cancer types, which lack established USPSTF-endorsed screening tests, including bile duct, endometrium, gallbladder, head and neck, liver, lymphoma, oesophagus, ovary, pancreas, and stomach. Certain cancers, such as bile duct29, gallbladder30, and pancreas31 are particularly challenging due to the absence of robust detection methods. Their asymptomatic nature and elusive locations often lead to late-stage diagnosis, severely limiting treatment options and contributing to poor prognoses. OncoSeek can be utilised for early detection of these cancers, offering patients more treatment options. Conversely, in the cancer types such as breast, oesophagus, and lymphoma, OncoSeek exhibits a sensitivity below 50%. Nonetheless, existing methods, including biennial mammograms, an X-ray imaging procedure of the breasts, effectively manage breast cancer detection32. Oesophageal cancer, easily accessible via endoscopy, allows for early diagnosis and potential curative treatment33. OncoSeek’s sensitivity in different cancer types are influenced by the presence of specific PTMs and the aggressiveness of the cancer. For instance, liver cancer, indicated by elevated AFP levels34, results in high sensitivity due to its unique PTMs. In contrast, cancer types like oesophageal, which lack such specific PTMs, are detected less readily. Furthermore, cancer invasiveness correlates with the amount of cancer proteins and/or DNAs released into the bloodstream20. Highly invasive cancers, like pancreatic cancer, tend to release more PTMs, thus increasing the sensitivity. Conversely, cancers like breast cancer, which is less invasive especially when it is localised, are less detectable by the blood-based tests20. Additionally, OncoSeek exhibited a sensitivity of 73.1% and a specificity of 90.6% among symptomatic individuals, which was for the higher proportion of cancer with advanced stages. This is consistent with the findings of the SYMPLIFY study using Galleri, reporting 66.3% sensitivity and 98.4% specificity in symptomatic patients35. The results suggest that OncoSeek can effectively serve as an auxiliary diagnostic tool for the individuals with cancer-related symptoms as well.

Similar to the other MCED technologies20,36,37, OncoSeek follows a sequential process – first detecting the presence of a cancer signal and then assigning its TOO. Errors can occur at each step, accumulating to affect overall performance. For example, in lung cancer, the sensitivity for detecting a cancer signal was 66.1% (509/770). Yet, only 61.5% (313/509) of these positive cases were correctly classified as originating in the lung, resulting in an overall sensitivity of 40.6% (313/770) for lung cancer. This distinction is clinically important, as the cancer type is unknown at the time of screening. The sequential nature of the current MCED assays is therefore a defining feature and a key consideration when evaluating their real-world utility. Future improvements in TOO assignment have the potential to mitigate error propagation and enhance overall clinical performance.

This study, while valuable, had several limitations. Despite including a small prospective blinded cohort, the study is predominantly a case-control design. Therefore, a larger-scale prospective study is needed to provide more robust evidence supporting the clinical application of OncoSeek. Meanwhile, the sensitivity of OncoSeek was lower at stage I (42.8%) compared to stage IV (79.7%), indicating a limitation in detecting early-stage cancers. As suggested in the published prospective studies, the sensitivity for early-stage cancers could be even lower, potentially leading to missed detection of early cancer patients38.

In summary, OncoSeek exhibited excellent consistency across seven cohorts from three countries, on four platforms, and with two types of samples. This performance indicates that OncoSeek is a robust MCED test. Coupled with its affordability and accessibility, it is well-suited for multi-cancer early detection, particularly in LMICs. Moreover, the superior performance in symptomatic patients supports that it can be used for early cancer diagnosis in the future.

Methods

Study design and quantification of PTMs

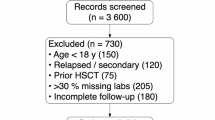

This study has incorporated four additional validation cohorts on top of three cohorts from the previous study13. Initially, we included a cohort of symptomatic patients, aiming to assess the efficacy of OncoSeek in early cancer diagnosis. Symptomatic patients are outpatients who exhibit cancer-related symptoms such as abdominal pain, radiographic detection of masses or nodules, and other indicators that need to be evaluated for cancer diagnosis. We enroled 1424 participants comprised of 869 symptomatic patients and 555 non-cancer individuals from the Henan Cancer Hospital (HNCH) between January 2023 and August 2023. Serum samples were collected to quantify the levels of seven selected PTMs including AFP, CA125, CA15-3, CA19-9, CA72-4, CEA, and CYFRA21-1 using the Roche Cobas e601/e602 analyser (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany)13. Subsequently, we expanded our study by including a prospective-blinded validation cohort of 128 participants from First Saúde, Brazil (FSD), which included 110 non-cancer individuals and 18 cancer patients. Among the cancer patients, some were diagnosed before blood sampling, while others were diagnosed afterward. All this information was blinded to us. The plasma samples of these individuals were collected and the seven PTMS were detected similarly using the Roche Cobas e601 analyser13. This study received approval from the Medical Ethics committee of Henan Cancer Hospital (2023-KY-0153). All participants provided written informed consent upon enrolment. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Further, to assess OncoSeek’s platform feasibility, we included two cohorts using two distinct platforms. One cohort included 450 participants (34 cancer patients and 416 non-cancer individuals) from BGI Clinical Laboratories (BGI), with PTMs assessed using plasma samples by an ELISA analyzer (BGI-GBI Biotech, Beijing, China), as detailed by Ji X et al.39. The other cohort, from Peking University Shenzhen Hospital (PUSH) between January 2017 and June 2018, included 3738 participants (149 cancer patients and 3589 non-cancer individuals). Peripheral blood samples were collected using serum collection tube (Improve Medical, Guangzhou, China). Serum was separated from the blood samples via centrifugation at 1300 × g for 10 min, conducted at room temperature (approximately 20 °C to 25 °C) within 4–6 h after collection. 1 ml serum was used to quantify the levels of six PTMs on the Abbott I2000 platform (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, USA) using the commercially available reagent kits following the manufacturer’s instructions. The six PTMs included AFP, CA125, CA15-3, CA19-9, CEA, and CYFRA21-1. CA72-4 was excluded due to its unavailability on the Abbott I2000 platform.

OncoSeek algorithmic analysis

As reported in our previous study13, we integrated the levels of PTMs into the OncoSeek algorithm to calculate the probability of cancer (POC). We selected the POC value associated with a 90.0% specificity in our training cohort as the threshold for cancer signal detection13. A POC exceeding this threshold was indicative of detected cancer signals; conversely, a POC below the threshold suggested the absence of such signals. For cohorts with missing CA72-4 data, we use the average value of the healthy group from the training cohort, which was 4.38, instead of the missing values. Next, we utilised a Random Forest (RF) algorithm to predict the tissue of origin (TOO) for patients with a true positive diagnosis. The RF algorithm prioritised organs based on their prediction probabilities, with the top two being identified as potential sites of tumour origin13.

Statistical analysis

We performed all statistical analyses utilising R software, version 4.1.2, a widely recognised platform for statistical computing (https://www.r-project.org). The performance of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was assessed to differentiate between cancer patients and non-cancer individuals, employing the pROC package, version 1.18.0. The metrics of sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values were ascertained through the epiR package, version 2.0.40 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/epiR/index.html), which is dedicated to epidemiological analysis. Additionally, the DeLong test was implemented to statistically compare the areas under the ROC curves (AUCs), providing a measure of prediction accuracy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the National GeneBank Data Center in China (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn) with accession number PRJCA017145.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is available at https://github.com/seekincancer/OncoSeek_2.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263, https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Brand, N. R., Qu, L. G., Chao, A. & Ilbawi, A. M. Delays and barriers to cancer care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Oncologist 24, e1371–e1380, https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0057 (2019).

Vinas, F., Ben Hassen, I., Jabot, L., Monnet, I. & Chouaid, C. Delays for diagnosis and treatment of lung cancers: a systematic review. Clin. Respir. J. 10, 267–271, https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.12217 (2016).

Jassem, J. et al. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: a multinational analysis. Eur. J. Public Health 24, 761–767, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt131 (2014).

Anggondowati, T., Ganti, A. K. & Islam, K. M. M. Impact of time-to-treatment on overall survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients-an analysis of the national cancer database. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 9, 1202–1211, https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-19-675 (2020).

Neal, R. D. et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br. J. Cancer 112, S92–S107, https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.48 (2015).

Hung, M.-C., Liu, M.-T., Cheng, Y.-M. & Wang, J.-D. Estimation of savings of life-years and cost from early detection of cervical cancer: a follow-up study using nationwide databases for the period 2002-2009. BMC Cancer 14, 505. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-505, (2014).

Clarke, C. A. et al. Projected reductions in absolute cancer-related deaths from diagnosing cancers before metastasis, 2006-2015. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 29, 895–902, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1366 (2020).

Nicholson, W. K. et al. Screening for breast cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 331, 1918–1930, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.5534 (2024).

Curry, S. J. et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 320, 674–686, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.10897 (2018).

Davidson, K. W. et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 325, 1965–1977, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.6238 (2021).

Mitchell, E. P. U. S. Preventive services task force final recommendation statement, evidence summary, and modeling studies on screening for lung cancer. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 113, 239–240, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2021.05.012 (2021).

Luan, Y. et al. A panel of seven protein tumour markers for effective and affordable multi-cancer early detection by artificial intelligence: a large-scale and multicentre case-control study. EClinicalMedicine 61, 102041, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102041 (2023).

Alix-Panabières, C. & Pantel, K. Liquid biopsy: from discovery to clinical application. Cancer Discov. 11, 858–873, https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1311 (2021).

Nikanjam, M., Kato, S. & Kurzrock, R. Liquid biopsy: current technology and clinical applications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15, 131, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01351-y (2022).

Bruhm, D. C. et al. Single-molecule genome-wide mutation profiles of cell-free DNA for non-invasive detection of cancer. Nat. Genet. 55, 1301–1310, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01446-3 (2023).

Meng, Z. et al. Noninvasive detection of hepatocellular carcinoma with circulating tumor DNA features and α-fetoprotein. J. Mol. Diagn. 23, 1174–1184, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2021.06.003 (2021).

Chung, D. C. et al. A cell-free DNA blood-based test for colorectal cancer screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 390, 973–983, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2304714 (2024).

Chang, Y. et al. Non-invasive detection of lymphoma with circulating tumor DNA features and protein tumor markers. Front. Oncol. 14, 1341997, https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1341997 (2024).

Klein, E. A. et al. Clinical validation of a targeted methylation-based multi-cancer early detection test using an independent validation set. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1167–1177, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.05.806 (2021).

Connal, S. et al. Liquid biopsies: the future of cancer early detection. J. Transl. Med. 21, 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-03960-8 (2023).

Adedimeji, A. et al. Challenges and opportunities associated with cervical cancer screening programs in a low income, high HIV prevalence context. BMC Women’s Health 21, 74, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01211-w (2021).

Islami, F., Torre, L. A., Drope, J. M., Ward, E. M. & Jemal, A. Global cancer in women: cancer control priorities. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 26, 458–470, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0871 (2017).

Akinyemiju, T. et al. A socio-ecological framework for cancer prevention in low and middle-income Countries. Front. Public Health 10, 884678, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.884678 (2022).

Pramesh, C. S. et al. Priorities for cancer research in low- and middle-income countries: a global perspective. Nat. Med. 28, 649–657, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01738-x (2022).

Shah, S. C., Kayamba, V., Peek, R. M. & Heimburger, D. Cancer control in low- and middle-income countries: is it time to consider screening?. J. Glob. Oncol. 5, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.18.00200 (2019).

Geng, S., Li, S., Wu, W., Chang, Y. & Mao, M. A cost-effective two-step approach for multi-cancer early detection in high-risk populations. Cancer Res. Commun. 5, 150–156, https://doi.org/10.1158/2767-9764.Crc-24-0508 (2025).

Cai, J. et al. Genome-wide mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosines in circulating cell-free DNA as a non-invasive approach for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 68, 2195–2205, https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318882 (2019).

Banales, J. M. et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 557–588, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-0310-z (2020).

Roa, J. C. et al. Gallbladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 8, 69, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-022-00398-y (2022).

Wood, L. D., Canto, M. I., Jaffee, E. M. & Simeone, D. M. Pancreatic cancer: pathogenesis, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 163, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.056 (2022).

Siu, A. L. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern Med. 164, 279–296, https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-2886 (2016).

di Pietro, M., Canto, M. I. & Fitzgerald, R. C. Endoscopic management of early adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: screening, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology 154, 421–436, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.041 (2018).

Gervain, J. Symptoms of hepatocellular carcinoma. Laboratory tests used for its diagnosis and screening]. Orv. Hetil. 151, 1415–1417, https://doi.org/10.1556/OH.2010.28945 (2010).

Nicholson, B. D. et al. Multi-cancer early detection test in symptomatic patients referred for cancer investigation in England and Wales (SYMPLIFY): a large-scale, observational cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 24, 733–743, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00277-2 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Clinical validation of a noninvasive multi-omics method for multicancer early detection in retrospective and prospective cohorts. J. Mol. Diagn. 27, 657–670, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2025.04.001 (2025).

Cohen, J. D. et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science 359, 926–930, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar3247 (2018).

Schrag, D. et al. Blood-based tests for multicancer early detection (PATHFINDER): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 402, 1251–1260, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01700-2 (2023).

Ji, X. et al. Identifying occult maternal malignancies from 1.93 million pregnant women undergoing noninvasive prenatal screening tests. Genet Med. 21, 2293–2302, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0510-5 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was partially funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.82202637), the Henan Province Young and Middle-aged Health Science and Technology Innovation Outstanding Youth Talent Training Program (Grant JQRC2024003), and the Health Commission provincial and ministerial co-construction Key project of Henan province (Grant SBGJ202402029). The funder collected participant samples and clinical information in this study. We thank all individuals who participated in this study. We are grateful to BGI Genomics for the clinical data and PTMs quantification data of the BGI cohort. We also thank Dr. Jun Zhou for helpful comments on the manuscript and Ms. Anthea Bull for language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. and S.L. designed the study; Y.S., Y.X., P.X., R.Z., R.B., L.J. and Q.X. collected participant samples and clinical information; S.L. and W.W. designed bioinformatics pipelines and analysed results with the help of M.M.; G.Z. and D.Z. performed the experiments; Y.C. wrote the manuscript, with critical review from M.M. and S.L.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.C. is a full-time employee of Shenyou Bio, a wholly owned subsidiary of SeekIn Inc., and holds stock options in SeekIn Inc. P.X. is a full-time employee of Shenyou Bio, a wholly owned subsidiary of SeekIn Inc. S.L. is a full-time employee of and holds stock options in SeekIn Inc. W.W. is a full-time employee of and holds stock options in SeekIn Inc. G.Z. is a full-time employee of and holds stock options in SeekIn Inc. D.Z. is a full-time employee of Shenyou Bio, a wholly owned subsidiary of SeekIn Inc, and holds stock options in SeekIn Inc. R.B. is a full-time employee of First Saúde. M.M. is a full-time employee of and holds stock options in SeekIn Inc. All other authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, Y., Xia, Y., Chang, Y. et al. A large-scale, multi-centre validation study of an AI-empowered blood-based test for multi-cancer early detection. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 321 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01105-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01105-2