Abstract

Manual data entry in cancer registries is both time-consuming and prone to error. Although large language models (LLMs) offer promising solutions, prior studies have frequently relied on preprocessed datasets or required complex fine-tuning, limiting their applicability in clinical settings. Here, we assessed the performance of out-of-the-box LLMs on TNM classification tasks using only prompt engineering, without data anonymization or model fine-tuning. We identified manual registry error rates of 5.5–17.0% in a real-world gynecologic cancer registry. Both a cloud-based LLM (Gemini 1.5; T- and N-stage accuracy: 0.994 and 0.993, respectively) and the top-performing local model (Qwen2.5 72B; T- and N-stage accuracy: 0.971 and 0.923, respectively) outperformed existing manual entries in extracting pathological T and N classifications. These models also achieved accuracies of 0.909 and 0.895 in clinical M classification, respectively. Our approach reflects real-world clinical workflows and offers a practical solution for enhancing data integrity in clinical registries using LLMs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Registry data play an increasingly substantial role in cancer care, with recent advancements in statistical methodologies demonstrating that database analyses yield results comparable to those of prospective trials1. Our group has conducted several registry-based studies2,3,4,5,6,7 and recognizes that developing reliable databases requires accurate information extraction and registration8. The TNM classification is among the most important data elements in cancer registries. Its stage groupings are defined for each cancer type based on prognostic relevance and are regularly updated to incorporate new evidence. For example, the cervical cancer T1b category, formerly comprising two substages (T1b1 and T1b2)9, has been reclassified into three (T1b1, T1b2, and T1b3)10. Similarly, the ovarian cancer T1c category has been subclassified into T1c1, T1c2, and T1c3 to reflect their distinct clinical implications11. Accurately registering these detailed classifications is crucial for maintaining the quality of future research; however, the process currently relies on manual data entry from unstructured records12.

Manual processes are susceptible to certain error rates13. For example, studies comparing the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database with raw medical records have reported accurate patient registration rates of 50–95%, depending on the treatment modality14, highlighting a critical challenge to registry data reliability. Similar degrees of misclassification are expected in TNM stage entry, and practical approaches for reliable and efficient registration are desired in clinical practice.

Recently, the application of large language models (LLMs) in the medical field has been remarkable, making it possible to leverage natural language processing (NLP) capabilities in transmitting medical knowledge, performing multilingual translation, and converting unstructured information into structured information. These technologies have diverse application possibilities in the medical field, including enhancing patient care, streamlining medical document creation, and improving access to scientific evidence15. They have shown promising results in medical document processing16 and may be useful in database construction from unstructured medical records, as described above.

Although several studies have explored the use of LLMs to extract registry data, their methods are difficult to implement in routine practice. Most published research relies on preprocessed or structured inputs17,18,19, whereas clinical documentation is largely unstructured12; thus, determining whether LLMs can achieve comparable accuracy when applied directly to raw reports is crucial. Furthermore, the solution should be accessible to clinicians without expertise in generative artificial intelligence (AI), ideally by deploying off-the-shelf LLMs without specialized fine-tuning.

This study initially investigated the frequency of registration errors in manually entered TNM classifications. We further examined whether LLMs could accurately extract TNM classifications from unstructured clinical text reports in their original format, using only prompt engineering without any model fine-tuning. We tested both cloud-based LLMs (such as ChatGPT and Gemini), for which we built a secure, dedicated environment to prevent patient data leakage, and local LLMs20, which were implemented in a completely isolated offline environment to ensure data confidentiality. Our solution achieved high accuracy in extracting TNM classifications, thereby establishing the foundation for real-world applications.

Results

Discrepancies between ground truth and Kyoto Registry Dataset

First, we compared the ground truth derived from the Kyoto Record with the Kyoto Registry Datasets for TNM classification to identify inaccuracies in the registry data. For pathological T (pT) classification in cervical cancer, 107 of the 129 cases (83.0%) were matched, whereas 22 cases (17.0%) showed discrepancies (Table 1). The most common error was misclassification of “T1b1” cases as “T1b2” (n = 5). Confusion within the T1b sub-classifications (T1b1, T1b2, T1b3, and T1bX) accounted for over half of the errors (n = 15), followed by discrepancies in the T1a sub-classifications (T1a1, T1a2, and T1aX) (n = 5). Notably, 15 of the 22 incorrectly registered cases matched the clinical T (cT) classification (Supplementary Fig. S1A).

For uterine corpus cancer, 327 of the 346 cases (94.5%) matched the pT classification, with 19 cases (5.5%) showing registration errors (Table 1). The most frequent error was registering T3X instead of T3a (four cases), followed by T3X instead of T3b (two cases) and T4 instead of T3a (two cases) (Supplementary Fig. S1B).

Regarding ovarian/fallopian tube/primary peritoneal cancer (collectively referred to as “ovarian cancer” hereafter), 145 of the 168 cases (86.3%) matched the pT classification, with 23 cases (13.7%) showing discrepancies (Table 1). The most common discrepancies included registrations of T1c1 instead of T1a (four cases), T1c1 instead of T1c3 (three cases), and T3c instead of T3b (three cases) (Supplementary Fig. S1C). For pathological N (pN) classification, which was only verified in ovarian cancer owing to the nature of the Kyoto Registry Dataset, 120 of the 135 cases (88.9%) were matched, with 15 cases (11.1%) showing discrepancies (Table 1). The most frequent error was registering N0 instead of NX (12 cases) (Supplementary Fig. S1D).

Discrepancies within the Kyoto Registry Dataset

Next, we examined internal inconsistencies within the Kyoto Registry Dataset to assess errors detectable using only the registry data, without medical records. For cervical cancer, we compared two related parameters that should align: registered “radiological findings of lymph node enlargement (logical N)” and registered “clinical N (cN)” classification. Of the 183 cervical cancer cases (after excluding missing data), 177 (96.7%) demonstrated consistency between these parameters, whereas six (3.3%) showed discrepancies. The discrepancies involved mismatches between radiological findings and cN classifications: lymph nodes with unknown status (logical NX) incorrectly registered as N0 (two cases), absence of enlargement (logical N0) incorrectly registered as N1 (two cases), pelvic node enlargement (logical N1) incorrectly registered as N2 (one case), and para-aortic node enlargement (logical N2) incorrectly registered as N1 (one case) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

These findings revealed two distinct types of inconsistencies in the tumor registry data: discrepancies between pathology reports (pT/pN) and their registry entries; and internal inconsistencies between related parameters (radiological findings and cN classifications) within the registry system.

Discrepancies within the external registry dataset

Our hypothesis that these inconsistencies were not limited to Kyoto University Hospital but could also occur at other institutions prompted the expansion of our analysis to include an external registry dataset. Similar error patterns emerged, with 3.4% (37 cases) showing discrepancies (Supplementary Fig. S3), similar to the Kyoto Registry Dataset. Detailed analysis revealed that among 337 cases marked as “logical N1: the presence of regional lymph node enlargement in radiology reports,” only two cases (0.6%) were incorrectly classified instead of the proper “cN1” classification in the registry. Of the 623 cases marked as “logical N0: No enlargement,” one case was incorrectly classified as cNX, and another was incorrectly classified as cN1 instead of cN0. Of the 33 cases marked as “logical NX: Unknown,” 27 cases were incorrectly classified as cN0 and two as cN1 instead of cNX.

Institution-specific performance varied (Supplementary Table S1); Kyoto Katsura Hospital, Kurashiki Central Hospital, and Osaka Medical Center achieved 100% consistency rates (24/24, 145/145, and 114/114, respectively). Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Kyoto Medical Center, the Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center, and Kindai University achieved consistency rates of 99.6% (250/251), 99.3% (136/137), 96.6% (85/88), and 88.0% (206/234), respectively.

These results indicate that registration errors also exist in the external registry dataset, with varying frequencies across institutions.

Impact of classification guideline revision

In Japan, multiple classification systems have been used, and their criteria have changed over time (Supplementary Table S2). To investigate whether changes in classification guidelines affected data consistency, we analyzed temporal variations in internal inconsistency rates within the Kyoto Registry Dataset. We compared the consistency between “radiological lymph node enlargement (logical N)” and “cN” registration across two periods: before (2013–2020, 97 cases) and after (2021–2022, 86 cases) the classification system revision. No discrepancies were observed between 2019 and 2020 (Supplementary Fig. S4A). However, six (7.0%) cases showed discrepancies between 2021 and 2022 (Supplementary Fig. S4B). We confirmed inconsistencies in the registry data, both within our institution and across external institutions, recognizing this as a significant challenge for quality assessment that relies on registry data. Based on these observations, we explored the potential of cloud-based and local LLMs in a secure environment to improve data accuracy.

Extraction of pT and pN classification by Gemini

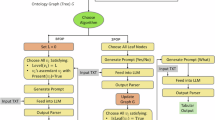

Next, we assessed TNM classification using LLMs. A schematic overview is presented in Fig. 1A–C. First, we investigated the performance of LLM-based detection in a secure network system with minimal external connections using the cloud-based LLM Gemini 1.5. For pT classification, Gemini correctly determined 945 of the 951 cases, achieving accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score of 0.994 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.988–0.998), 0.948 (95% CI: 0.798–0.999), 0.994 (95% CI: 0.795–0.998), and 0.967 (95% CI: 0.797–0.999), respectively (Fig. 2A). The system accurately identified cases with no information (not specified; N.S.) with 98.3% accuracy. Detailed class-wise performance metrics are summarized in Supplementary Table S3. Gemini achieved complete classification without errors for T2, and high performance for T1 and T3 (F1 scores of 1.000, 0.995, and 0.995, respectively). Performance for T4 was lower, likely due to the small sample size (n = 3). When stratified based on the cancer type (uterine corpus, cervical, and ovarian cancers), the model demonstrated the highest performance in uterine corpus cancer (F1 = 1.000), followed by cervical (F1 = 0.994) and ovarian (F1 = 0.796) cancers (Supplementary Table S4). Further detailed confusion matrices for pT classification based on the cancer type are provided in Fig. 3A–C.

A An overview of the pipeline is presented. More detailed workflows are illustrated in (B, C). B Three workflows are illustrated: a medical data analysis system from electronic medical records to the Google Cloud Platform analysis environment (orange frame), a local LLM system without external communication (blue frame), and human annotation. C Local LLM inference was conducted on a Linux server within a private network, without an Internet connection or external data transfer, ensuring complete data isolation. Clinical reports containing personal information were processed locally using LLMs served via vLLM on an NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada GPU. Prompts were input into the system, and structured outputs in JSON format were generated. This setup provides enhanced data security, fast and consistent inference, and allows customization for domain-specific tasks. PET-CT positron emission tomography-computed tomography, LLM large language model, JSON JavaScript Object Notation.

onfusion matrices showing Gemini’s performance in extracting pT (A) and pN (B) classifications from pathology reports of all gynecologic cancer types (cervical, uterine, and ovarian cancers, n = 951). The vertical axis represents the ground truth obtained via visual inspection, and the horizontal axis shows the Gemini extraction values. The numbers in each cell indicate the number of applicable cases (n). N.S. Not specified.

Confusion matrices of detailed pT classification performance extracted using Gemini from pathology reports of cervical (A), uterine corpus (B), and ovarian (C) cancers, including sub-classification. The vertical axis represents the ground truth obtained via visual inspection, and the horizontal axis shows the Gemini extraction results. The numbers in each cell indicate the number of applicable cases (n). N.S. Not specified.

A detailed error analysis of the six discrepant cases revealed two main categories of failure. (1) Context-based over-generation (n = 4): In these cases, the model generated a pT classification even though no such annotation was present in the [Diagnosis] section. A manual review showed that in two of these four cases, the model correctly inferred the appropriate classification from contextual evidence present in the [Findings] section, suggesting context-aware reasoning rather than true misclassification. The remaining two instances lacked sufficient contextual support, indicating over-generation or hallucination.

(2) Multi-tumor confusion (n = 2): These errors occurred in patients with synchronous malignancies (such as uterine corpus and ovarian cancers), where the model misattributed the pT classification to the incorrect tumor site, highlighting the model’s current limitations in disambiguating entity-specific information in complex multi-entity contexts.

For pN classification, Gemini correctly determined 944 of the 951 cases. The model achieved accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score of 0.993 (95% CI: 0.987–0.998), 0.995 (95% CI: 0.992–0.999), 0.990 (95% CI: 0.981–0.997), and 0.993 (95% CI: 0.986–0.997), respectively (Fig. 2B). The system identified N.S. cases with 99.7% accuracy. Detailed class-wise performance metrics for the pN classification of Gemini are presented in Supplementary Table S5. The model achieved near-perfect performance across all classes, with F1 scores of 0.999, 0.993, 1.000, 0.988, and 0.983 for N0, N1, N2, N.S., and NX, respectively. When stratified based on the cancer type, Gemini achieved the highest F1 score in cervical cancer (F1 = 1.000), followed by uterine corpus (F1 = 0.990) and ovarian (F1 = 0.983) cancers (Supplementary Table S6). Further detailed confusion matrices for pN classification based on cancer type are provided in Fig. 4A–C. These results suggest consistently robust performance across cancer types, with slight variation possibly attributable to sample size or class complexity.

Confusion matrices of detailed pN classification performance extracted using Gemini from pathology reports of cervical (A), uterine corpus (B), and ovarian (C) cancers, including sub-classification. The vertical axis represents the ground truth obtained via visual inspection, and the horizontal axis shows the Gemini extraction results. The numbers in each cell indicate the number of applicable cases (n). N.S. Not specified.

Overall, seven classification errors were identified in the pN task, which could be grouped into the following three primary error types: (1) Contextual misclassification of NX cases as N.S. (n = 5): In all five cases, the model incorrectly labeled NX cases as N.S. Upon review, each of these cases involved an initial classification of NX based on the primary surgical specimen, followed by a subsequent diagnostic lymph node dissection, suggesting that the model failed to integrate temporal diagnostic updates, leading to under-classification. (2) Context-based over-generation (n = 1): One case involved outputting N0 despite the absence of explicit documentation in the [Diagnosis] section. However, a manual review confirmed that the N0 status was accurately inferred from the [Findings] section, indicating a context-sensitive inference rather than a hallucination, highlighting the model’s capacity for latent reasoning in the absence of direct annotation. (3) Conflicting documentation and annotation ambiguity (n = 1): A single case involved misclassification of N1 cases as N.S. due to the presence of multiple, temporally discordant diagnostic statements (for example, “Diagnosis revised N0 → N1 after a review confirmed lymph node metastasis”). The model’s failure to resolve this ambiguity reflects limitations in handling longitudinal or revision-based diagnostic narratives. These errors suggest that while the model performs well in static classification tasks, it is challenged by temporal inconsistencies, diagnostic revisions, and hierarchical inference across clinical sections.

These results demonstrate that Gemini can accurately extract pT and pN classifications from multiple pathology reports across gynecologic cancer types while correctly identifying unspecified cases with high precision.

Assessment of clinical M (cM) classification by Gemini

We evaluated Gemini’s performance on cM classification using positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) reports. Of the 648 cases, 589 were correctly classified as M0 or M1, with accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score of 0.909 (95% CI: 0.886–0.931), 0.673 (95% CI: 0.586–0.758), 0.763 (95% CI: 0.674–0.845), and 0.715 (95% CI: 0.642–0.781), respectively (Fig. 5). When stratified based on cancer type, the model demonstrated the highest performance in uterine corpus cancer (F1 = 0.727), followed by cervical (F1 = 0.714) and ovarian (F1 = 0.694) cancers (Supplementary Table S7). Further detailed confusion matrices for M classification based on the cancer type are provided in Supplementary Fig. S5A–C.

Confusion matrix of cM classification accuracy determined using Gemini from PET-CT reports of cervical, uterine, and ovarian cancers. The vertical axis represents the ground truth obtained via visual inspection, and the horizontal axis shows the Gemini determination results. The numbers in each cell indicate the number of applicable cases (n).

A detailed analysis of misclassifications in the M-stage task revealed two major error types—false positives (M1 predicted and true label M0) and false negatives (M0 predicted and true label M1)—with distinct subtype-specific patterns. (1) False Positives: Over-classification of M1 (n = 36, 6.5%). Among 36 false positives, the misclassification rate varied by cancer type: 3.2% (6/179), 4.7% (10/201), and 12% (20/135) in cervical, uterine corpus, and ovarian cancers, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S5A–C). In ovarian cancer, 15 of the 20 false positives were due to misinterpreting peritoneal dissemination as M1, despite peritoneal spread not constituting distant metastasis (M-stage) in ovarian cancer staging. Across cancer types, inflammatory nodules were another common source of false positives, misinterpreted as distant metastases in 12 cases. (2) False Negatives: Missed M1 Classifications (n = 23, 24%). Of the 97 cases that should have been classified as M1, 23 were mislabeled as M0. This error occurred at comparable rates across cancer types: cervical (28%, 8/28), uterine corpus (20%, 5/25), and ovarian (22%, 10/44) cancers (Supplementary Fig. S5A–C). The most prevalent error subtype (65%, 15/23) involved extra-regional lymph node metastases being interpreted as N-stage disease instead of M1.

These results indicate that while Gemini achieved relatively high accuracy in analyzing PET-CT reports for cM classification, its performance was somewhat lower than that for pT and pN extraction from pathology reports. Despite providing detailed instructions on the M classification judgment method through in-context learning (ICL), we found that the LLM occasionally violated them.

Assessment of TNM classifications by local LLMs

To explore the feasibility of the on-premises deployment, we evaluated several local LLMs. We conducted pT, pN, and cM classification extractions and assessments using local LLMs in an offline environment built on our in-house server (Fig. 1B), following a procedure similar to that of the Gemini evaluation. To ensure consistent conditions, we used the same datasets and prompts for the local LLMs to process pTN and cM classifications as those used for Gemini. Among the eight local LLMs tested, the Qwen2.5 model with 72B parameters demonstrated the best performance in all tasks, achieving the highest accuracy for pT, pN, and cM classifications.

For pT classification, Qwen2.5 72B correctly determined 923 of the 951 cases, achieving accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score of 0.971 (95% CI: 0.959–0.981), 0.934 (95% CI: 0.821–0.987), 0.965 (95% CI: 0.950–0.981), and 0.943 (95% CI: 0.846–0.983), respectively (Fig. 6A). Detailed class-wise performance metrics are summarized in Supplementary Table S8. Notably, the N.S. category showed a relatively low recall rate (0.918). Error analysis revealed that the primary failure mode was hallucination, with the model generating fictitious T stages for 17 of the 19 misclassified N.S. cases rather than correctly identifying them as unclassifiable. When stratified based on cancer type, Qwen2.5 72B achieved the highest F1 score in cervical cancer (F1 = 1.000), followed by uterine corpus (F1 = 0.992) and ovarian (F1 = 0.985) cancers (Supplementary Table S9). Regarding pN classification, Qwen2.5 72B correctly determined 878 of the 951 cases. The model achieved accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score of 0.923 (95% CI: 0.907–0.940), 0.860 (95% CI: 0.823–0.897), 0.924 (95% CI: 0.899–0.945), and 0.885 (95% CI: 0.852–0.914), respectively (Fig. 6B). Detailed class-wise performance metrics are summarized in Supplementary Table S10. Error analysis revealed that, similar to the pT classification, hallucinations were prominent where the model generated a fictitious N status for cases marked as N.S. When stratified based on cancer type, Qwen2.5 72B achieved the highest F1 score in ovarian cancer (F1 = 0.985), followed by uterine corpus (F1 = 0.935) and cervical (F1 = 0.906) cancers (Supplementary Table S11). For cM classification, Qwen2.5 72B correctly determined 580 of the 648 cases, achieving accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score of 0.895 (95% CI: 0.872–0.918), 0.628 (95% CI: 0.540–0.714), 0.732 (95% CI: 0.636–0.817), and 0.676 (95% CI: 0.601–0.745), respectively (Fig. 6C). Error analysis revealed both false positives and negatives, similar to those in the cM classification results of Gemini. Despite explicit instructions in the prompt, there was a notable tendency to classify peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer as M1. When stratified based on cancer type, Qwen2.5 72B achieved the highest F1 score in cervical cancer (F1 = 0.925), followed by uterine corpus (F1 = 0.919) and ovarian (F1 = 0.834) cancers (Supplementary Table S12).

Confusion matrices showing the performance of Qwen2.5 72B in extracting pT (A) and pN (B) classifications from pathology reports and determining cM (C) classification from PET-CT reports. The vertical axis represents the ground truth obtained via visual inspection, and the horizontal axis shows the Qwen2.5 72B extraction values. The numbers in each cell indicate the number of applicable cases (n). N.S. Not specified.

The results of other local LLM performance, including accuracy, processing times, and Gemini’s performance for comparison, are presented in Supplementary Table S13.

Ablation studies and ensemble methods for cM classification

To better understand the relatively low performance of cM and explore potential improvements, we conducted a detailed error analysis and a series of ablation studies using Qwen 2.5 72B.

First, we organized specific examples of common errors in cM classification for both Gemini 1.5 and Qwen 2.5 72B, along with the reasoning provided by the LLMs and the correct classifications (Supplementary Table S14). The main error categories included cases that violated specific classification rules for each cancer type, misjudgments of lymph node metastases, and misunderstandings of clinical expressions.

Based on this analysis, we implemented several strategies to improve the accuracy of cM classification. We first tested a simplified prompt (Supplementary Note S4A) that omitted the detailed instructions on how to determine metastasis from our original prompt for cM. This change led to a significant decrease in accuracy, with mean differences of 0.083 (95% CI: 0.056–0.113, p < 0.001), 0.217 (95% CI: 0.147–0.296, p < 0.001), 0.134 (95% CI: 0.028–0.235, p = 0.022), and 0.189 (95% CI: 0.111–0.263, p < 0.001) in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, respectively (Supplementary Table S15).

Next, we added specific errors identified from our analysis as few-shot prompts (Supplementary Note S4B), including the input that led to the error, the correct answer, and the correct interpretation. However, this approach did not lead to a significant improvement in accuracy. The mean differences in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score were −0.0098 (95% CI: −0.0309 to 0.0123, p = 0.424), −0.0706 (95% CI: −0.1486 to 0.0004, p = 0.054), 0.092 (95% CI: 0.0000–0.1827, p = 0.056), and 0.0081 (95% CI: −0.0628 to 0.0765, p = 0.824), respectively (Supplementary Table S16).

Subsequently, we applied self-consistency, generating five different inference paths for each case and selecting the result by majority vote. The answers from all five inference paths were identical, and this method also failed to improve classification accuracy (Supplementary Table S17).

Finally, we attempted model integration using a simple majority-vote ensemble of the Gemini 1.5, Qwen2.5 72B, and Gemma 2 27B. This ensemble achieved the same scores as Gemini 1.5 across all evaluation metrics—Accuracy (0.909), Precision (0.673), Recall (0.763), and F1 Score (0.715)—showing no improvement in performance (Supplementary Table S18).

Comparative performance of conventional prompting versus Pydantic-constrained decoding

To compare with conventional methods, we evaluated the performance of Qwen2.5 72B using two approaches as follows: prompt-based JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) structured output generation versus Pydantic-constrained decoding, examining both output variations and classification performance. Despite the prompt instructing the model to output in JSON format, the prompt-based structured output exhibited variations in JSON structure notation and included extraneous outputs such as explanations (Fig. 7A), ultimately requiring manual visual inspection to assess its performance. In contrast, Pydantic-constrained decoding with forced JSON output generation produced consistent JSON-formatted outputs exclusively, with no instances of JSON structure breakdown observed (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, the Pydantic-constrained approach demonstrated significant improvements across all metrics compared to prompt-based structured output, with mean differences of 0.0268 (95% CI: 0.0095–0.0452, p = 0.004), 0.0231 (95% CI: 0.0076–0.0409, p = 0.008), 0.0268 (95% CI: 0.0095–0.0452, p = 0.004), and 0.0271 (95% CI: 0.0095–0.0462, p = 0.006) in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, respectively (Fig. 7C–E). These results indicate that Pydantic-constrained decoding demonstrated better performance than conventional prompt-based methods, possibly due to the elimination of output verbosity and structural inconsistencies.

A Example of conventional prompt-based structured output. The output may include unnecessary explanations or inconsistent formatting, requiring manual post-processing. B Example output using Pydantic-enforced constraints, which ensures format consistency and suppresses irrelevant text. C, D Confusion matrices showing the accuracy of Qwen2.5 72B in extracting pT classification from pathology reports of gynecologic cancers (n = 951), with (C) and without (D) Pydantic-based structured decoding. The vertical axis represents the ground truth pT values obtained via manual annotation, and the horizontal axis indicates the pT values extracted using the model. Each cell shows the number of cases (n). “N.S.” denotes “Not specified.” E Summary of performance differences between the two approaches. The use of Pydantic significantly improved all metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, as evaluated using bootstrapped mean differences and 95% confidence intervals. All improvements were statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study, we identified manual data entry errors in cancer registries and demonstrated that both cloud-based and local LLMs can more accurately extract TNM information from unprocessed medical records in secure environments without any task-specific fine-tuning, highlighting the potential of LLMs to improve data quality and reduce manual workload.

Our analysis revealed significant discrepancies, ranging from 5.5 to 17.0% for the pT classification, between expert-derived ground truth and the existing gynecologic tumor registry. Further, an examination of internal contradictions within the database showed a discrepancy of 3.3% for the cN classification, consistent with those of previous reports14,21. Most inconsistencies tended to occur within sub-classifications (such as pT1b1 of cervical cancer or pT1c1 of ovarian cancer), indicating that the complexity of the classification criteria may contribute to data entry errors. Furthermore, the increase in the discrepancy rate following a revision of clinical guidelines underscores the vulnerability of manual registration to systemic changes. Although no prior literature specifically addresses this phenomenon, this outcome is understandable, considering the increased complexity of the task. Although consistency checks have been implemented in the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) registry to prevent registration errors, our analysis revealed a 3% internal contradiction rate.

By contrast, LLMs achieved high accuracy in extracting and assessing TNM information, consistent with prior studies on classification tasks17,18, although those studies used processed short texts. Our study has several strengths. It extends previous findings by using unprocessed, unstructured reports and demonstrating comparable performance. A critical factor is the “context window”—the maximum amount of text LLMs can process at once. Current state-of-the-art models, including Gemini and Qwen, can handle tens of thousands to millions of tokens, making them suitable for our raw, lengthy source documents (Supplementary Fig. S6D–E). Thus, comparison with conventional NLP models, such as bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (up to 512 tokens)22, or earlier LLMs, including Llama 2 (up to 4000 tokens)23, was not feasible. A recent study further showed that even older LLMs (such as ChatGPT 3.5) outperform traditional NLP methods17, supporting our focus on state-of-the-art LLMs. Furthermore, the LLMs maintained accuracy not only for major classifications (such as T1 and T2), which have been the focus of previous studies24, but also for detailed subclassifications (T1a1, T1a2, T1b1, and T1b2), which directly influence treatment25.

In addition, we directly processed real-world data containing missing values, unlike prior studies that relied on anonymized public datasets, such as those from The Cancer Genome Atlas (https://cBioPortal.org) and Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care17,18,19, and excluded incomplete cases17. Our approach allowed accurate identification of “absence of information,” providing a more realistic evaluation.

Moreover, we implemented schema-enforced JSON output using Pydantic to enhance extraction quality and demonstrated that using Pydantic significantly improves accuracy over prompt-only methods by preventing output format degradation, representing an important step toward automated clinical pipelines.

Our study had two limitations. First, the primary validation was conducted in a single institution, requiring further investigation for generalizability. However, we adopted a strategy where the system outputs “not specified” when information is insufficient, which functioned accurately. We anticipate that this framework will also be robust at other institutions as well. To further strengthen external validity, we have initiated a Japanese multi-center collaborative study, focusing on reducing manual preprocessing burdens, such as anonymization, by developing secure frameworks for raw clinical data sharing and LLM-based analysis.

A second limitation is the comparatively lower accuracy of cM classification relative to pT and pN. To improve cM task performance, we evaluated some methodologies, including few-shot prompting via ICL and self-consistency, as well as ensemble methods that integrate the outputs of multiple models. However, these approaches did not improve accuracy, suggesting that a fundamental revision of the method will be necessary to interpret cM from the radiology reports, which remains a subject for future consideration.

Finally, LLM technology is advancing remarkably rapidly—one report noted that models with half the size achieved equivalent performance within a few months26. Consequently, establishing secure and efficient clinical frameworks for LLM use is becoming increasingly urgent, and institutions should carefully select cloud-based or local LLMs based on their specific needs and constraints. Simultaneously, the clinical application of LLMs demands profound consideration of ethical and societal issues, including patient consent and data privacy27. The “black box” nature of LLMs makes it challenging for patients to understand data usage28,29. Therefore, obtaining meaningful consent demands clear explanations of data usage in LLM processing and protocols for managing unexpected findings30. Moreover, strong governance frameworks are essential to prevent risks, including data breaches, reinforcing biases, or inappropriate profiling31. These frameworks should combine technical safeguards, such as encryption, with strict data-use policies and robust auditing procedures to ensure compliance. As LLM technology advances rapidly, establishing safe and effective implementation frameworks will be foundational to responsibly delivering the benefits of future AI innovations to patients.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that high-accuracy TNM classification can be achieved by applying existing cloud-based and local LLMs directly to non-preprocessed, raw medical data. This finding suggests that institutions can flexibly adopt cloud-based or local LLMs according to their resources, providing a scalable solution for real-world clinical use.

Methods

Data sources

The Institutional Review Board of Kyoto University Hospital approved this study (approval number: R4775). Informed consent was obtained through an opt-out process. The study primarily used pathology and PET-CT reports from Kyoto University Hospital’s electronic medical records (Kyoto Record Dataset), which have all been submitted to the JSOG Registry Dataset (Kyoto Registry Dataset). Furthermore, it incorporated external gynecologic tumor registry data from the JSOG (Registry Datasets).

1. Kyoto Record Dataset: This study included 951 patients (385 uterine corpus, 299 cervical, and 267 ovarian cancer cases) who began treatment at our hospital between 2016 and 2022. For each patient, raw pathology reports from the initial consultation to the completion of the initial treatment and raw PET-CT reports immediately before the initial treatment were collected from the in-house clinical data warehouse. Upon extraction of pathology reports, at least one pathology report was available for all cases, yielding 2,115 pathology reports (948, 608, and 559 for uterine corpus, cervical, and ovarian cancers, respectively). On average, 2.31 pathology reports were documented per case, with variation by cancer type: uterine corpus (2.46), cervical (2.30), and ovarian cancers (2.09) (Supplementary Fig. S6A–C). Regarding PET-CT reports, each case had a maximum of one report. After excluding 303 cases without reports, 648 PET-CT reports were extracted (236, 213, and 199 for uterine corpus, cervical, and ovarian cancers, respectively). The length of pathology reports, measured via token count using the commonly adopted TikToken tokenizer (a standard method for converting text into numerical units for LLMs)32, varied widely (mean 1941 tokens; range 98–8726), with a right-skewed distribution indicating a subset of exceptionally long documents (Supplementary Fig. S6D), as multiple raw reports were concatenated for each case. In contrast, PET reports were shorter and more consistent in length, with a mean of 589 tokens and a narrower distribution (range 231–1783) (Supplementary Fig. S6E). These differences in token length were considered when designing the input strategy for LLM processing, ensuring compatibility with the context window limitations of the model. From all extracted reports, those relevant to the study’s objective were selected. Two clinicians (K.I. and A.S.) independently conducted the selection process. The criterion for selection was “reports considered essential for diagnosing diseases subject to tumor registration.” For reports where the selections by the two clinicians differed, a consensus was reached through discussion to determine final inclusion. The reports that were finally selected were standardized into a format where each report corresponds to a single JSON object for subsequent processing. Each object contains information, including the report type, report date, and the report text.

2. Kyoto Registry Dataset: This dataset comprises the institutional data, which had all been registered manually every year in the JSOG Gynecologic Tumor Registry between 2016 and 2022. While covering identical patient populations as the Record Dataset, this represents the structured registry format rather than raw clinical documentation.

3. External Registry Dataset: This dataset included 1,097 cervical cancer cases registered in the JSOG Gynecologic Tumor Registry from seven designated cancer care hospitals between 2014 and 2019. The seven hospitals are Kyoto Katsura Hospital (31 cases), National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center (137 cases), National Hospital Organization Osaka Medical Center (170 cases), Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital (258 cases), Ohara Memorial Kurashiki Central Medical Organization Kurashiki Central Hospital (159 cases), Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center (108 cases), and Kindai University Hospital (234 cases).

Handling of raw clinical data

To completely replicate a real-world clinical workflow, this study directly used raw, unstructured text data extracted from electronic health records. Notably, the data were used in their original format without any preprocessing, cleaning, or anonymization, preserving the complexity of clinical documentation. For data management, multiple pathology reports for a single case were consolidated into a single JSON dataset. As there was at most one PET-CT report per patient, each was stored individually in a separate JSON file. A representative example of a dataset for a fictionalized case is presented in Supplementary Note S1.

Generation of ground truth using the Kyoto Record Dataset

The ground truths for pT, pN, and cM classifications were generated using the JSON-formatted Kyoto Record Dataset. For pT and pN classifications, pathology reports were utilized. The pathology reports in the Kyoto Record Dataset comprise two sections as follows: [Diagnosis] and [Findings]. The [Diagnosis] section contains pT and pN classifications, while the [Findings] section provides detailed textual descriptions of diagnostic criteria, including tumor size and lymph node metastasis status. During data extraction, pT and pN classifications recorded in the [Diagnosis] section were considered authoritative, with the final diagnosis being adopted in cases where multiple pathology reports showed different classifications. For pT and pN classification, we utilized the [Diagnosis] section of the pathology reports, assigning the “Not specified” label where T and N classifications were absent. For cM classification, a comprehensive assessment of the entire PET-CT report content was conducted to determine the cM0 or cM1 status. The PET-CT reports in the Kyoto Record Dataset are structured with [Diagnosis] and [Findings] sections. The [Diagnosis] section contains a summary of findings, while the [Findings] section provides detailed textual descriptions of information discernible from imaging. In contrast to pathology reports, radiology reports do not explicitly state cM classification; therefore, a comprehensive assessment of the entire report content was conducted to determine either cM0 or cM1 status.

Regarding data validation, two gynecologists (K.I. and A.S.) conducted independent evaluations. In cases where the evaluators’ assessments differed, final determinations were reached through consensus discussions, with a third party (R.M.) providing input.

Assessment of discrepancies between ground truth and Kyoto Registry Dataset

The consistency between the ground truth derived from the Kyoto Record and Kyoto Registry Datasets was evaluated. While the Kyoto Registry Dataset contains various elements, including clinical background, histological types, and prognosis, this analysis specifically focused on the consistency of pT and pN classifications between the ground truth derived from raw clinical documentation and the manually registered registry data. Cases labeled as “Not specified” during ground truth creation—those lacking explicit pT or pN documentation in reports—were excluded from the analysis to ensure valid comparisons.

The consistency assessment for pT classification was conducted across all three cancer types (cervical, uterine corpus, and ovarian cancer), as pT classification data were available in the Kyoto Registry Dataset for all three cancers. Regarding pN classification, the evaluation was limited to ovarian cancer cases for two reasons. First, in the Kyoto Registry Dataset, the pN classification entry was not mandatory for cervical and uterine corpus cancers, resulting in minimal data entry. Second, lymph node metastasis data were subclassified into multiple categories (pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes, among others), making direct comparison with pathology report pN classifications impractical. However, as pN classification was mandatory and consistently recorded for ovarian cancer cases, the consistency assessment for pN classification was conducted exclusively for ovarian cancer.

The final analysis included 643 paired comparisons between ground truth and the Kyoto Registry Dataset: 129 cases for T classification in cervical cancer; 346 cases for T classification in uterine corpus cancer; and for ovarian cancer, 168 and 129 cases for T and N classifications, respectively.

Assessment of internal discrepancies in tumor registry data

We analyzed evident errors within the Kyoto Registry and External Registry Datasets, focusing specifically on the consistency of lymph node-related parameters in cervical cancer cases. In these registry datasets, cervical cancer registration requires the input of two related parameters as follows: “presence of lymph node enlargement in radiology reports” and “cN classification.” These entries effectively represent the same clinical information in two different locations.

Our study evaluated the discrepancy rate between the “presence of regional lymph node enlargement in radiology reports” and “cN classification.” This analysis encompassed both the Kyoto Registry and External Registry Datasets. Japanese cervical cancer registration protocols are updated in accordance with the Union for International Cancer Control and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics revisions (Supplementary Table S2)33. The 2020 guideline revision reclassified para-aortic lymph node metastasis as N2, introducing greater complexity to the N classification system. Consequently, for the Kyoto Registry Dataset, we also analyzed changes in discrepancy rates before and after this guideline revision.

After excluding cases with missing registration items, we analyzed 183 and 993 cases from the Kyoto Registry Dataset (61% of the total 299 cervical cancer cases) and the External Registry Dataset (90% of the total 1097 cervical cancer cases), respectively. The methodology for comparing registration items differed between the pre-2020 and post-2021 periods due to guideline changes. Before 2020, regional lymph node enlargement was recorded using a three-tier system: unknown status, absence of enlargement, or presence of enlargement. The cN classification during this period used NX to indicate insufficient examination for assessment, N0 for the absence of regional lymph metastasis, and N1 for the presence of regional lymph metastasis. Under these criteria, radiological findings of lymph node enlargement should directly correspond to cN classifications: unknown status corresponded to NX, the absence of regional lymph enlargement indicated N0, and the presence of regional lymph enlargement indicated N1.

The 2020 revision introduced more detailed categorization. Lymph node enlargement assessment was separated into two distinct evaluations: one for pelvic lymph nodes and another for para-aortic lymph nodes. Each category maintained the same three-tier assessment system (unknown status, absence, or presence). The cN classification system was expanded to include the following: NX for insufficient examination, N0 for no metastasis, N1 for pelvic node metastasis only, N21 for para-aortic node metastasis only, and N22 for metastasis in both locations. This new system established more complex correspondence rules to radiological findings: unknown status in both locations corresponded to NX, absence in both locations meant N0, pelvic enlargement alone corresponded to N1, para-aortic enlargement alone indicated N21, and enlargement in both locations signified N22.

Secure LLM system and model settings

We implemented two distinct secure LLM environments (Fig. 1). The first was a cloud-based environment on Google Cloud Platform at Kyoto University Hospital using Gemini 1.534 with stringent security measures, implementing strict access controls and data leak prevention within the university network infrastructure. This platform provides guaranteed protection against the use of input information for model training. The entire workflow—including extracting patient information from electronic medical records, data formatting, and LLM processing—is integrated within this secure platform. While closed models similar to Gemini offer superior performance, they have notable limitations as follows: their specifications are subject to frequent changes, and they provide limited flexibility for incorporating additional training data. To address these challenges, we developed real-world workflows for TNM staging assessment from unstructured textual data using open-source LLMs. This local environment is designed to operate without external communication requirements with various open-source models, including Llama 3.1 (8B and 70B), 3.2 (3B), and 3.3 (70B) by Meta35; Gemma 2 (27B) by Google36; and Qwen2.5 (32B and 72B)37 and QwQ (32B) (https://huggingface.co/Qwen/QwQ-32B), a reasoning-enhanced model by Alibaba. Complete information for setting up the local LLM environment and detailed descriptions of the cloud and local models used in this study are provided in Supplementary Note S2.

Non-adoption of fine-tuning

The workflow of LLM processing is shown in Supplementary Fig. S7. No additional fine-tuning of the LLM was performed in this study to maximize the ICL capabilities of recent large-scale foundation models and validate the effectiveness of an approach that accomplishes tasks solely through prompt engineering. Considering the cost of creating high-quality training data in the medical field and the computational cost associated with fine-tuning large models, we aimed to explore a more cost-effective and implementable method.

Task design through prompt engineering

We adopted prompt engineering as the central methodology. The primary goal of identifying the TNM classification elements was categorized into two subtasks with increasing complexity. For a fair comparison, the same prompts were used for both cloud-based and local LLMs. Task 1: T and N Classification Extraction: For the foundational task of extracting T and N categories from pathology reports, we designed a structured prompt emphasizing procedural accuracy and stable, machine-readable outputs. This task is considered equivalent to Named Entity Recognition. Task 2: M Classification Determination: This task is more challenging, as it requires comprehensive reasoning about the presence of distant metastasis based on the entire context of radiology reports. Therefore, building upon the structured approach of Task 1, we developed an enhanced prompt that additionally incorporates knowledge injection and a guided reasoning process, designed to steer the model’s complex judgment in a clinically valid direction. This task is considered equivalent to Text Classification.

Complete prompts and a detailed explanation of our prompt engineering strategy, including the rationale, structure, and key components of each prompt, are provided in Supplementary Note S3.

Ablation and ensemble strategies for cM classification

To address the lower performance in cM classification, we conducted several ablation studies.

Eliminating ICL prompt: To test the utility of ICL for the cM determination task, we omitted detailed metastasis identification instructions from our original prompt to assess whether performance would decline (Supplementary Note S4A).

Few-Shot Prompting: We enhanced the baseline zero-shot cM prompt using few-shot prompting38,39, referencing common errors identified from our error analysis (Supplementary Table S14). These examples, which paired excerpts of input text with their correct cM classification and reasoning, were designed to guide the model to avoid common pitfalls. The complete prompt can be found in Supplementary Note S4B.

Self-Consistency: We incorporated the approach from Wang et al.40 to ensure diversity. Following the original paper, we changed the temperature setting from 0 to 0.6 to increase the diversity of the model’s outputs. Subsequently, we implemented a self-consistency approach by generating five different reasoning paths for each PET-CT report. The prompt used was the few-shot version from Supplementary Note S4B. The final classification was determined based on a majority vote among the five outputs.

Model Ensembling: Recently, an increasing number of studies have attempted to improve performance by combining multiple models41. We tested a simple majority-vote ensemble by combining the predictions from three models with different architectures that had demonstrated high accuracy—Gemini 1.5, Qwen2.5 72B, and Gemma 2 27B—for cM classification. The final prediction for each case was determined when at least two of the three models agreed.

Evaluation metrics

We defined correct answers as exact matches between the LLM outputs and ground truth data. For example, if the correct stage was “T1a” and the LLM output was “The stage is T1a,” it was considered incorrect. LLM model performance was quantitatively evaluated using the following standard metrics:

Accuracy: measures the proportion of correct predictions among all predictions:

Precision: quantifies the proportion of true positive predictions among all positive predictions:

Recall: represents the proportion of actual positive cases correctly identified:

F1 score: provides a harmonic mean of precision and recall:

where TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. For the calculation of 95% CIs and statistical hypothesis testing, a non-parametric bootstrapping method was employed. Overall, 1000 bootstrap resamples were drawn from the test set. For each resample, the difference in each performance metric was calculated. Next, the 95% CI was determined from the resulting empirical distribution of 1000 performance differences. This CI was subsequently used for hypothesis testing; a statistically significant difference was concluded if the 95% CI did not include zero. P values were also derived from the bootstrap distribution. All analyses were performed using Python (version 3.12).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they contain personal information, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, with appropriately anonymized and de-identified data provided after necessary ethical and institutional approvals.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is available on GitHub: https://github.com/iishiken/structured-clinical-data-extraction.

References

Wang, S. V. et al. Emulation of randomized clinical trials with nonrandomized database analyses: results of 32 clinical trials. JAMA 329, 1376–1385 (2023).

Inayama, Y. et al. Changes in physical activity across cancer diagnosis and treatment based on smartphone step count data linked to a Japanese claims database: retrospective cohort study. JMIR Cancer 11, e58093 (2025).

Ohsuga, T. et al. Association of preconception premenstrual disorders with perinatal depression: an analysis of the perinatal clinical database of a single Japanese institution. Biopsychosoc. Med. 18, 24 (2024).

Fukuda, M. et al. Real-world application of comprehensive genomic profiling for gynecological malignancies: a multicenter observational study. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 1967–1976 (2024).

Inayama, Y. et al. Real-world practice of estrogen and progestogen prescriptions in menopausal women in Japan: a descriptive study using a Japanese claims database. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 49, 2952–2961 (2023).

Inayama, Y. et al. Hormone replacement therapy and cancer risks in perimenopausal women: a retrospective cohort study using a Japanese claims database. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 49, 1805–1814 (2023).

Inayama, Y. et al. Real-world practice of estrogen therapy after surgery for endometrial cancer: a descriptive study using a Japanese claims database. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 445–453 (2023).

Brierley, J., Gospodarowicz, M. & O’Sullivan, B. The principles of cancer staging. Ecancermedicalscience 10, ed61 (2016).

Pecorelli, S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 105, 103–104 (2009).

Bhatla, N., Aoki, D., Sharma, D. N. & Sankaranarayanan, R. Cancer of the cervix uteri. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 143(Suppl 2), 22–36 (2018).

Berek, J. S., Renz, M., Kehoe, S., Kumar, L. & Friedlander, M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 155(Suppl 1), 61–85 (2021).

Kong, H.-J. Managing unstructured big data in healthcare system. Healthc. Inform. Res. 25, 1–2 (2019).

Rollison, D. E. et al. Current and emerging informatics initiatives impactful to cancer registries. J. Regist. Manag. 49, 153–160 (2022).

Kraus, R. D., Hamilton, A. S., Carlos, M. & Ballas, L. K. Using hospital medical record data to assess the accuracy of the SEER Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program for initial treatment of prostate cancer: a small pilot study. Cancer Causes Control 29, 815–821 (2018).

Clusmann, J. et al. The future landscape of large language models in medicine. Commun. Med. 3, 141 (2023).

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29, 1930–1940 (2023).

Huang, J. et al. A critical assessment of using ChatGPT for extracting structured data from clinical notes. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 106 (2024).

Truhn, D. et al. Extracting structured information from unstructured histopathology reports using generative pre-trained transformer 4 (GPT-4). J. Pathol. 262, 310–319 (2024).

Wiest, I. C. et al. Privacy-preserving large language models for structured medical information retrieval. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 257 (2024).

Jonnagaddala, J. & Wong, Z. S.-Y. Privacy preserving strategies for electronic health records in the era of large language models. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 34 (2025).

Palis, B. E. et al. The National Cancer Database conforms to the standardized framework for registry and data quality. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 31, 5546–5559 (2024).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1810.04805 (2018).

Touvron, H. et al. Llama 2: open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.09288 (2023).

Kefeli, J., Berkowitz, J., Acitores Cortina, J. M., Tsang, K. K. & Tatonetti, N. P. Generalizable and automated classification of TNM stage from pathology reports with external validation. Nat. Commun. 15, 8916 (2024).

Abu-Rustum, N. R. et al. NCCN guidelines® insights: cervical cancer, version 1. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 21, 1224–1233 (2023).

Xiao, C. et al. Densing law of LLMs. arXiv [cs.AI] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.04315 (2024).

Ong, J. C. L. et al. Ethical and regulatory challenges of large language models in medicine. Lancet Digit. Health 6, e428–e432 (2024).

Amann, J. et al. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 20, 310 (2020).

Comeau, D. S., Bitterman, D. S. & Celi, L. A. Preventing unrestricted and unmonitored AI experimentation in healthcare through transparency and accountability. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 42 (2025).

Blackman, J. & Veerapen, R. On the practical, ethical, and legal necessity of clinical Artificial Intelligence explainability: an examination of key arguments. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 25, 111 (2025).

Wang, C. et al. Ethical considerations of using ChatGPT in health care. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e48009 (2023).

Tiktoken: Tiktoken Is a Fast BPE Tokeniser for Use with OpenAI’s Models. (Github).

Hamada, K. et al. Re-evaluating prognostic factors for cervical cancer with lymph node metastasis: a Japanese multicenter cohort study based on FIGO 2018. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 584–592 (2025).

Gemini Team et al. Gemini 1.5: unlocking multimodal understanding across millions of tokens of context. arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.05530 (2024).

Touvron, H. et al. LLaMA: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.13971 (2023).

Gemma Team et al. Gemma: open models based on Gemini research and technology. arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.08295 (2024).

Bai, J. et al. Qwen Technical Report. arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.16609 (2023).

Brown, T. B. et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.14165 (2020).

Min, S. et al. Rethinking the role of demonstrations: what makes in-context learning work? arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2202.12837 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.11171 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Harnessing multiple large language models: a survey on LLM ensemble. arXiv [cs.CL] https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.18036 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Large Language Model Advanced Training & Challenging Hub (LLMATCH), supported by the Matsuo Laboratory LLM Community, for their valuable technical advice. We also thank Editage (http://www.editage.com) for English language editing and manuscript review. We also thank Dr. Rikiya Yamashita for his insightful comments and suggestions. Funding: T.K. received a research grant from Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd in 2022 for a project titled “Sharing Medication History using Prescription Records among Multiple Stakeholders,” which is unrelated to the current study. The funder had no role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of this manuscript. All other authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Note: Kohei Hamada is referred to as KH1, Koki Hasebe as KH2, Ryusuke Murakami as RMu, Rin Mizuno as RMi, Koji Yamanoi as KYo and Ken Yamaguchi as KYa. KI and RMu conceptualized and designed the study. KI, RMu, KYo and KH1 wrote and revised the manuscript. KI, RMu and AS performed the data analysis. TM, RMi, and MT assisted with experimental procedures and data collection. KH2 provided specialized expertise for specific analytical methodologies. KYa and JH supervised the clinical aspects of the research and provided critical feedback. KS, KK, GY and TK provided technical support and computational resources and significantly contributed to the critical direction of the research. KI and RMu wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. MM supervised the entire project and provided administrative support and final approval of the manuscript. RMu was responsible for project administration and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishida, K., Murakami, R., Yamanoi, K. et al. Real-world application of large language models for automated TNM staging using unstructured gynecologic oncology reports. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 366 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01157-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01157-4