Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is opening new frontiers in the development of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), offering unprecedented opportunities for precision therapy. This review outlines how AI empowers each stage of the ADC pipeline. In target discovery, multi-omics integration and graph-based learning prioritize tumor-selective and internalizing antigens. In antibody engineering, structure prediction, affinity optimization, and developability modeling streamline candidate selection. For linker-payload design, generative models and multi-objective optimization approaches support the rational design of conjugates that balance potency, stability, and immunogenicity. In absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) modeling, deep learning and transformer-based frameworks predict pharmacokinetics and toxicity with increasing accuracy and mechanistic clarity. In clinical development, AI facilitates patient stratification, response prediction, and trial simulation through digital twin models, adaptive dosing algorithms, and real-world data integration. These capabilities support a more personalized and efficient pathway from bench to bedside. To further realize the impact of AI in ADC development, we highlight strategic priorities including the creation of curated, multimodal datasets, interpretable model architectures, and closed-loop experimental platforms. Together, these advances will be essential for realizing the full potential of AI to support rational, scalable, and personalized ADC-based therapies in oncology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antibody-drug conjugates: emerging paradigms in targeted oncology

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) represent an innovative and strategically engineered class of therapeutics designed to deliver potent cytotoxic agents selectively to tumor cells, thereby enhancing efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity1,2. The fundamental architecture of an ADC comprises three critical components: a monoclonal antibody targeting a specific tumor-associated antigen (TAA), a highly potent cytotoxic payload, and a chemical linker that covalently couples the payload to the antibody. The antibody component ensures targeted delivery through high-affinity binding to the TAA, which is predominantly expressed on cancer cells. Upon binding, the ADC-antigen complex is typically internalized, allowing intracellular release of the payload through linker cleavage within lysosomal or tumor microenvironmental conditions. This targeted mechanism underlies the therapeutic promise of ADCs, potentially improving clinical outcomes and reducing side effects compared to traditional chemotherapy2.

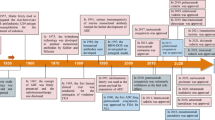

Since the first ADC, gemtuzumab ozogamicin, received FDA approval in 2000, the field has experienced a resurgence driven by technological advances in antibody engineering, linker chemistry, and cytotoxic payload design3,4. To date, more than 18 ADCs have entered clinical use, exemplified by agents such as trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) in breast, gastric, and lung cancers5,6,7, trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in HER2-positive breast cancer8, and brentuximab vedotin in Hodgkin lymphoma9. Despite these notable achievements, the development of ADCs continues to face significant scientific and practical hurdles that impede broader clinical translation and therapeutic efficacy10.

Persistent challenges in ADC development

ADCs encounter multifaceted challenges across their entire developmental continuum, spanning target selection, linker design, payload optimization, resistance management, and manufacturing complexities11. Foremost among these challenges is the identification of ideal tumor-selective targets. The scarcity of antigens uniquely expressed by tumors and heterogeneity in antigen expression, even with well-established markers such as HER2 and TROP2, can undermine efficacy and lead to resistance or toxicity due to off-target effects2. Moreover, off-target toxicity, which results from unintended antibody binding to normal tissues (on-target, off-tumor toxicity), nonspecific uptake by healthy cells, or premature payload release in systemic circulation, remains a critical barrier12.

Linker chemistry further complicates ADC development. Effective linkers must balance systemic stability to prevent premature drug release with the capacity for efficient payload liberation upon intracellular internalization13. Decisions regarding linker cleavability, hydrophilicity, and drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) require extensive empirical optimization and often yield unpredictable pharmacokinetics (PK). Similarly, the cytotoxic payloads employed typically are microtubule inhibitors or DNA-damaging agents that must exhibit potent biological activity at nanomolar concentrations14,15. Yet, their hydrophobicity can induce aggregation, trigger immune responses, or limit endosomal escape. Recently emerging payload classes, such as immunostimulatory agents or pyroptosis inducers, amplify the complexity of preclinical modeling and design16.

Drug resistance also critically limits ADC therapeutic durability17. Tumor cells can evade ADC efficacy via antigen downregulation or mutation, impaired internalization, altered intracellular trafficking, drug efflux pump upregulation, or changes in apoptosis pathways. In addition, tumor heterogeneity both within individual tumors and among different patients further complicates therapeutic response prediction and patient stratification. Manufacturing ADCs poses additional technical challenges, as achieving consistent DAR and reproducible quality across batches necessitates sophisticated characterization and stringent control strategies, making ADC production more intricate and costly compared to conventional biologics or small molecules.

Given these complexities, ADC development still relies substantially on empirical trial-and-error approaches. Consequently, high attrition rates persist in preclinical and clinical stages, prolonging timelines and constraining innovation.

The emergence of artificial intelligence: accelerating ADC innovation

AI has substantially reshaped drug discovery in recent years, particularly in small-molecule therapeutics, by accelerating predictive modeling, data-driven decision-making, and optimization across multiple stages from target identification to clinical trial design18,19,20. Advances in large language models (LLMs), graph neural networks (GNNs), and multimodal architectures have significantly improved the processing and interpretation of complex biomedical data, reduced development timelines, and enhancing candidate success rates21,22,23. Despite these advancements in other therapeutic domains, AI applications within ADC development remain relatively nascent. The inherent complexity of ADCs as multi-component entities poses unique modeling challenges, as conventional AI models trained primarily on small-molecule datasets often fail to capture ADC-specific modular architectures and conjugation effects. Furthermore, data scarcity, particularly regarding conjugation chemistries, intracellular trafficking mechanisms, and clinical pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD), limits the robustness of ADC-specific predictive models.

Nevertheless, recent studies highlight promising avenues for AI integration into ADC design. AI-driven methodologies have demonstrated potential in identifying tumor-specific antigens through multi-omics integration24, optimizing antibody structures via structure-informed machine learning25, predicting linker stability using quantum chemical models26, and evaluating toxicity risks based on patient-derived and real-world datasets (RWD)27 (Fig. 1). By systematically incorporating AI into ADC development workflows, researchers can transition from linear, empirical screening toward an iterative “design-build-test-learn (DBTL)” cycle. In this paradigm, AI supports experimental work by providing predictive guidance, enhancing efficiency, precision, and scalability. This is particularly important for the “tripartite optimization challenge”, improving the antibody, linker, and payload at the same time, even when their requirements may conflict. AI, particularly methods that handle many factors at once, helps navigate this complexity and makes it possible to design ADCs with better therapeutic performance.

This schematic outlines the integration of AI across the major stages of ADC development, from target identification to clinical translation. For each stage, it highlights the essential data inputs (e.g., multi-omics, imaging data), the representative AI models (e.g., GNNs, Transformers), and the primary outputs (e.g., prioritized targets, optimized antibody sequences) that AI facilitates, demonstrating a modern, data-driven paradigm for ADC innovation.

This review aims to comprehensively examine the current landscape of AI applications in ADC development, addressing opportunities and limitations throughout the development process, from early-stage discovery and molecular engineering to preclinical optimization, patient stratification, and clinical translation. We highlight representative studies, emerging computational tools, and platform technologies tailored specifically for ADC design. Furthermore, we critically evaluate persistent challenges, including data scarcity, interpretability, and integration complexities, and propose strategic future directions for advancing AI-guided ADC development. Ultimately, we envision a transformative paradigm where artificial intelligence meaningfully accelerates rational, data-informed innovation in ADC-based cancer therapeutics, facilitating more personalized, effective, and broadly accessible treatment strategies.

Literature search and selection strategy

This review summarizes current applications of AI in ADC development based on a structured literature search and analysis.

Search strategy

We systematically searched PubMed, Google Scholar, arXiv, and bioRxiv for articles published between January 2015 and May 2025. Search terms were combined of (“antibody-drug conjugate” OR “ADC”) with “artificial intelligence,” “AI,” “machine learning,” “deep learning,” “target identification,” “antibody engineering,” “linker,” “payload,” “pharmacokinetics,” and “clinical trial.” Reference lists of key reviews were also screened to identify additional studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Following an initial screening of titles and abstracts, full-text assessment was performed for eligibility. We included studies and reviews that described AI/ML applications in any stage of the ADC development pipeline. We excluded studies limited to small molecules or non-ADC biologics unless methods were directly transferable to ADCs, studies without sufficient methodological detail, conference abstracts without full publications, and non-peer-reviewed sources.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two authors independently reviewed eligible articles and extracted data, resolving discrepancies by discussion. Extracted information included the AI methodology, data sources, application stage in the ADC pipeline, platform or tool name, type of validation (computational, experimental, or clinical), and key findings. Results were summarized according to the ADC development workflow (Fig. 1), with emphasis on representative approaches and their validation status.

AI for target identification in ADCs

The precise identification of tumor antigens is the foundational step in ADC development, fundamentally shaping therapeutic specificity, efficacy, and safety. Unlike small-molecule drugs, ADCs rely on the selective expression and, critically, the efficient internalization of membrane-bound proteins to deliver their cytotoxic payloads to tumor cells. However, the tumor antigen landscape is inherently complex, characterized by intra-tumoral heterogeneity and expression in some normal tissues, which complicates target selection. While conventional methods like immunohistochemistry (IHC) and bulk transcriptomics are valuable, they are often limited in scale and may not fully capture the multi-parameter profile of an ideal ADC target28.

To provide a systematic overview, Table 1 categorizes the key AI methodologies discussed in this section and summarizes their specific data requirements and applications in ADC target identification. It is crucial to emphasize that these computational methods do not replace foundational experimental techniques. Rather, they serve as powerful complementary tools to integrate complex datasets, generate testable hypotheses, and accelerate the data analysis cycle, thereby guiding more efficient and targeted experimental validation.

AI-driven platforms for high-throughput target discovery

The advent of large-scale omics data has enabled systematic in silico mining for potential ADC targets, offering a high-throughput complement to labor-intensive traditional experimental screening. Early bioinformatics approaches filtered publicly available datasets to prioritize candidates. For example, Razzaghdoust et al. interrogated the Human Protein Atlas (HPA), prioritizing membrane proteins with favorable tumor-versus-normal tissue expression based on IHC data, ultimately identifying 23 candidate targets using “quasi H-score”29. Beyond computational checks, they experimentally validated the expression of two identified targets, NECTIN4 and HER2 (ERBB2), in urothelial carcinoma tissue microarrays via IHC, confirming consistency with their in silico scores. Similarly, Fang et al. developed an algorithm integrating transcriptomic, proteomic, and genomic data across 19 solid cancer types, identifying 75 candidate surface proteins suitable for ADC targeting. This work established a comprehensive in silico target atlas; the validation of the identified targets was based on rigorous bioinformatic filtering against multiple expression and safety criteria rather than direct experimental testing of novel candidates30.

Modern AI platforms enable deeper integration and more complex pattern recognition23. Lantern Pharma’s RADR® AI platform processed multi-omics and IHC data to identified 82 prioritized targets31. The validity of this in silico approach was supported by the fact that their list included 22 antigens, such as HER2 and NECTIN4, that have already been validated in preclinical or clinical settings, though the 60 novel predictions await direct experimental confirmation. Insilico Medicine’s PandaOmics platform uses GNNs and literature mining to prioritize novel targets32. Crucially, PandaOmics has been experimentally validated through multiple case studies; for example, its AI-driven predictions for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) were confirmed in a Drosophila model, while its identification of CDK20 as a target for hepatocellular carcinoma led to the successful synthesis and in vitro testing of a novel inhibitor32.

AI-powered characterization of antigen heterogeneity and function

Beyond initial identification, AI offers powerful tools to assess the functional suitability of ADC targets. Tumor heterogeneity can be dissected using AI-driven analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics data33,34. Unsupervised clustering and deep learning models can identify distinct tumor subpopulations and their unique antigen expression profiles, offering insights into spatial targeting potential and informing strategies to overcome resistance.

AI tools based on unsupervised clustering algorithms, variational autoencoders, and manifold learning techniques are increasingly being employed to dissect this heterogeneity and identify phenotypically distinct tumor subpopulations that express actionable ADC targets. For instance, deep learning models have been applied to stratify epithelial tumor cells based on the expression patterns of ADC-relevant markers such as TROP2, CD74, and B7-H3, offering critical insights into the spatial targeting potential within a tumor and helping to minimize off-tumor risks by understanding antigen distribution more precisely35,36,37. While specific AI tools for TROP2/CD74/B7-H3 stratification from spatial/scRNA-seq data were not detailed in all provided materials, the general capability of AI to perform such analyses is well-established. This ability to map the target landscape at a granular level is essential not only for predicting ADC penetration but also for modeling the bystander effect, a critical therapeutic mechanism for many ADCs that depends on the spatial interplay between antigen-positive and antigen-negative cells.

Internalization efficiency is another critical functional attribute for most ADCs, as the payload typically needs to be released intracellularly to exert its cytotoxic effect. AI models are beginning to address this. For example, high-content imaging platforms, when combined with AI-based image analysis algorithms, often involving convolutional neural networks (CNNs) (Table 1), can gain the capacity for the rapid and quantitative assessment of antibody-antigen internalization dynamics38,39,40. The reliability of this high-throughput approach has been experimentally demonstrated. For instance, one study developed an high-content analysis-based screen where AI-quantified colocalization was used to identify internalizing antibodies41. The top candidates were then converted to full-length IgGs and their efficient internalization was confirmed through functional antibody-toxin conjugate assays, which resulted in potent and specific tumor cell killing, thus validating the AI-driven screening predictions. Such AI-driven image analysis can potentially identify subtle structural motifs on the antigen or antibody, such as specific glycosylation patterns or receptor clustering domains, that might facilitate efficient clathrin-mediated endocytosis or other internalization pathways. This represents a significant enhancement to target validation workflows that traditionally relied on expression levels alone (e.g., transcriptomics). By integrating functional predictions like internalization, AI helps de-risk targets that may be highly expressed but internalize poorly, thus preventing potential ADC failure. The ability to predict or rapidly screen for internalization potential in silico or via high-throughput assays augmented by AI can thus save considerable time and resources in the early stages of ADC development.

Leveraging real-world data and literature with AI

AI is also playing an increasingly significant role in bridging the gap between molecular target characteristics and their clinical relevance by leveraging RWD and the vast corpus of biomedical literature. Natural language processing (NLP) tools, including advanced transformer-based models like BioGPT42 and PubMedBERT43, are being applied to systematically mine and extract information on antigen-disease associations, expression patterns, and potential therapeutic relevance from unstructured sources such as biomedical research papers, pathology reports, and electronic health records (EHRs). While direct applications of BioGPT/PubMedBERT for ADC target discovery from EHRs are still emerging, their proven capabilities in biomedical text mining are highly relevant. The integration of insights derived from NLP with omics-based target prioritization provides a more holistic and clinically informed understanding of a candidate tumor antigen’s biology and its translational viability. The validity of these models is established by their superior performance on biomedical NLP benchmarks. For example, BioGPT has achieved state-of-the-art results on question answering and relation extraction tasks, demonstrating its advanced capability to accurately process and “understand” complex biomedical literature, which is essential for reliable target-disease association mining42.

This approach has proven effective in uncovering or highlighting targets that, while perhaps expressed at lower frequencies, hold significant clinical relevance. Examples include B7-H4, which is emerging as a target in triple-negative breast cancer and other solid tumors44. These targets might have been underestimated by traditional screening methods due to more limited visibility in high-throughput omics datasets alone or a less historical research focus. NLP helps to aggregate disparate pieces of evidence from literature that, when combined, build a stronger case for the target investigation.

Overcoming hurdles and charting the future of AI in ADC target discovery

Despite significant progress, AI-driven ADC target discovery still faces major challenges. A key limitation is the scarcity of high-quality, ADC-specific labeled datasets, particularly for functional attributes such as internalization efficiency, subcellular trafficking, and cross-reactivity profiles. While resources like the HPA provide useful IHC data, they remain constrained by sample size and limited antibody validation across all potential targets.

Public repositories also tend to emphasize transcriptomic data, whereas ADC efficacy is more closely linked to protein-level characteristics. In addition, AI models frequently detect correlations that require extensive experimental testing to establish mechanistic relevance and confirm suitability for ADC development. Finally, defining an “ideal” ADC target remains complex: optimal candidates must combine high tumor selectivity with minimal expression in normal tissues. Because many promising targets still show low-level normal tissue expression, advanced AI models capable of balancing these competing criteria are needed to guide rational target selection.

Looking forward, AI is poised to enable highly personalized ADC target discovery. Future systems may integrate individual patient multi-omics data, including spatial and single-cell analyses, with clinical and imaging information to identify patient-specific or subpopulation-specific antigens. The development of multimodal foundation models, akin to LLMs but trained on a combination of text, imaging, and omics data, will be crucial for reasoning across these diverse data types. Incorporating physics-informed neural networks could further enhance predictions by simulating antibody-antigen interactions and estimating toxicity risks. Ultimately, AI will not only refine target identification but also accelerate the design of optimal target-payload-linker combinations, building on initial explorations to usher in a new era of precision ADC therapies.

AI in antibody engineering

The antibody component is pivotal to an ADC’s function, and AI is transforming its design from a lengthy, empirical process into a more rational and predictive endeavor45,46,47,48. AI-driven in silico modeling now accelerates nearly every aspect of antibody engineering, from initial structure prediction and affinity maturation to assessing developability and minimizing immunogenicity, as summarized in Table 2.

AI accelerates antibody structure prediction and affinity optimization

AI significantly accelerates antibody structure prediction and the optimization of binding affinity49. Recent breakthroughs in deep learning have yielded highly accurate structure prediction tools, including AlphaFold250,51 and RoseTTAFold52, capable of modeling complete antibody structures, particularly the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs), with high precision. These models are instrumental in designing binding interfaces and improving affinity for targets such as EGFRvIII and HER3 through conformational refinements and loop engineering. Beyond structural modeling, deep learning tools like DeepAb can predict specific CDR mutations that enhance binding affinity while preserving specificity. For instance, DeepAb-guided optimization reportedly resulted in over ten-fold improvement in the affinity of an anti-lysosome antibody53.

AI has also been instrumental in engineering bispecific antibodies, which are increasingly employed in ADC platforms. These complex molecules, designed for either dual targeting or immune cell engagement, present challenges related to chain pairing and domain stability. AI tools, such as computational design platforms and reinforcement learning (RL) frameworks, have been applied to optimize linker length and binding geometry, as demonstrated with CD3 × HER2 bispecific antibodies that exhibited significantly enhanced T cell activation in vitro54.

AI supports Fc engineering and antibody developability assessment

Furthermore, AI supports the engineering of the Fc domain and aids in assessing antibody developability. The Fc domain of therapeutic antibodies can be modified to modulate immune effector functions and extend serum half-life. AI models, trained on datasets of Fc mutations, have successfully predicted the impact of variants on binding to Fcγ receptors (FcγR) and the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). For example, the M252Y/S254T/T256E (YTE) mutation was computationally identified for enhanced FcRn interaction at acidic pH, leading to an over two-fold increase in serum half-life in non-human primates55. Similarly, Fc-silencing mutations, such as LALA (L234A/L235A) and LALAPG (L234A/L235A/P329G), known to abrogate Antibody-Dependent Cell-mediated Cytotoxicity, have been evaluated using computational approaches, including machine learning classifiers, to minimize on-target/off-tumor toxicity in ADC applications56. AI models can also predict potential off-target binding of the antibody component to unintended proteins or tissues31. By analyzing antibody sequences and structures, alongside data on known protein-protein interactions and tissue expression profiles, these models can flag antibodies with a higher risk of undesirable cross-reactivity. AI models can also be trained to predict specific toxicities commonly associated with ADCs by learning from historical preclinical and clinical data.

AI-guided workflows complement experimental design and enable scalable ADC optimization

A major challenge in engineering the antibody component of an ADC is that it cannot be optimized independently; its performance is tightly linked to the physicochemical properties of the linker and payload. A key role for AI, therefore, is in predicting post-conjugation developability attributes. This includes forecasting how payload-induced hydrophobicity may affect solubility, thermal stability, and aggregation risk. Protein language models such as ESM57 and ProtT558 have demonstrated robust capabilities in predicting folding stability and surface exposure directly from sequence data. For instance, ThermoNet59 provides estimates of thermal stability changes (ΔTm) with high accuracy, while SoluProt60 assists in identifying mutations that enhance solubility, thereby facilitating high-throughput prescreening before experimental validation. AI-driven assessments of “developability” are increasingly integrated early in the design phase. AI has been employed to generate novel antibody candidates de novo. Transformer-based models, such as BioGPT42, have successfully created PD-L1-binding antibodies, with a high percentage being expressible in mammalian cells and demonstrating nanomolar binding affinity after minimal optimization. These results underscore AI’s capacity to expand the exploration of sequence space beyond what is achievable through traditional immunization or phage display methods.

Immunogenicity remains a significant concern in ADC development, particularly when incorporating non-human or engineered sequences. AI tools have been developed to address this by predicting immunogenic potential. Site-specific Immunogenicity for Therapeutic Antibodies (SITA)61 utilizes transfer learning and 3D structural descriptors to predict B-cell immunogenicity at the residue level. SITA has demonstrated superior accuracy compared to models like SEPPA3.062, DiscoTope63, and BioPhi64, and can correctly identify potential mutation sites for humanization. This capability enables rational humanization strategies aimed at reducing the formation of anti-drug antibodies without compromising efficacy. The foundational tool, Spatial Epitope Prediction of Protein Antigens (SEPPA)65, developed earlier, introduced geometric modeling of surface patches to identify conformational B-cell epitopes. While initially designed for vaccine antigens, SEPPA’s concepts remain applicable to ADC development by predicting epitope accessibility and supporting Fab-antigen interface design. AI models trained to recognize immunogenic motifs or T-cell epitopes within protein sequences can predict an antibody’s immunogenic potential and suggest modifications to mitigate this risk, often as part of humanization or stability engineering processes. This early-stage, AI-driven de-risking can yield considerable savings in time and resources.

Despite these advancements, AI-based antibody engineering faces notable limitations. Current structure prediction models may underperform in modeling long heavy-chain complementarity-determining region 3 (HCDR3) loops, which are frequently crucial for antigen recognition. Affinity prediction tools trained on co-crystal structures of soluble antigen-antibody complexes might not generalize effectively to membrane-bound or post-translationally modified epitopes typically found on tumor cell surfaces. Furthermore, a significant gap exists as most current models do not explicitly predict ADC-specific functions. Future AI frameworks will need to integrate predictions of not only binding affinity but also antigen internalization kinetics, lysosomal trafficking efficiency, and payload-specific endosomal escape. Interpretability remains a challenge, particularly for clinical translation and regulatory review, where mechanistic insight is essential. Looking forward, the true paradigm shift will emerge from integrating AI predictions with high-throughput experimental feedback in fully automated, closed-loop DBTL platforms. Such systems, where AI designs are rapidly synthesized and tested, with the resulting data immediately feeding back to retrain the models, will be essential to address these complex, multi-parameter challenges. Continued expansion of high-quality structural, functional, and immunogenicity datasets, along with the refinement of multimodal AI frameworks, will be key to advancing AI from a predictive aid to a core engine of ADC antibody design.

AI for linker-payload optimization in ADCs

The linker and payload form the functional core of an ADC, determining its potency, release mechanism, and safety profile. Their design, however, is not an independent task but a co-optimization challenge intrinsically linked to the antibody scaffold13,15. Key objectives include ensuring linker stability in circulation while enabling selective cleavage in the tumor, designing payloads with high potency and manageable hydrophobicity, and predicting how the final conjugate will behave as a whole. AI is uniquely suited to navigate this multi-objective landscape, offering generative models for novel chemistry discovery and predictive frameworks to balance the delicate interplay between potency, stability, and overall developability66.

Molecular generative models for payload optimization

AI-driven molecular generative models have increasingly been applied to the de novo design of novel payload structures endowed with desired physicochemical and pharmacological properties. Among these, simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES)-based language models and GNN-based generators are the most widely adopted approaches for small molecule design, and their principles are being extended to payload discovery67,68. These models are typically trained on large libraries of known chemical compounds, such as ChEMBL69 or ZINC70, enabling them to learn the underlying syntactic and chemical rules for constructing valid and potentially active molecules.

For instance, MolGPT71 and ChemBERTa72, two transformer-based models trained on SMILES sequences, have been explored for their potential to generate novel payload analogs with predictions for improved cytotoxicity, better aqueous solubility (to counteract aggregation issues), and reduced off-target liabilities. In conceptualized studies, GNN-based frameworks such as GraphAF73 and G-SchNet74 have demonstrated utility in scaffold hopping and exploring novel functional group substitutions for established payload classes like topoisomerase inhibitors and DNA alkylators, which are commonly used in ADCs. These generative capabilities allow for the in silico prioritization of payload structures that aim to maintain or enhance cytotoxic activity while offering improved metabolic profiles or a reduced risk of aggregation once conjugated to the antibody.

Beyond the generation of new payloads, the design of cleavable linkers is also increasingly being approached using AI-assisted retrosynthesis planning and structure-based property prediction. For example, RL agents, when coupled with quantum chemical descriptors or other advanced molecular feature representations, have been trained to propose peptide-based linkers (e.g., variations of Val-Cit or Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly sequences) with computationally optimized plasma stability and enzyme-specific cleavage kinetics (e.g., for cathepsin B)75,76,77,78. This demonstrates AI’s potential not only for payload novelty but also for fine-tuning the critical release mechanisms governed by the linker.

Predictive modeling of payload-antibody interactions and intracellular dynamics

Another significant area where AI has demonstrated value is in predicting the impact of the chosen payload and linker on the overall biophysical and PK properties of the fully assembled ADC. Following conjugation, the attached linker-payload can alter the antibody’s intrinsic properties, such as its solubility, propensity for aggregation, and its interaction with FcRn, which mediates antibody recycling and thus influences serum half-life. In practice, this type of predictive modeling has been applied to guide the rational selection of hydrophilic spacers (e.g., PEGylated or sulfonated linkers) to counteract the aggregation often induced by highly hydrophobic payloads like monomethyl auristatin E or pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimers13.

AI has also made important contributions to modeling intracellular release kinetics, a factor that directly influences the therapeutic efficacy of an ADC by determining how quickly and efficiently the payload is liberated at the target site. Machine learning approaches, including gradient boosting and deep learning, have been applied to predict enzymatic cleavage behavior based on features such as linker amino acid composition, structural motifs, and subcellular trafficking patterns. For instance, Procleave have shown strong performance in predicting protease-specific peptide cleavage sites via combining sequence-derived features and supervised learning, demonstrating the feasibility of systematically modeling proteolytic activity for payload-linker optimization79. Similarly, ReCGBM, a LightGBM-based model, accurately predicts Dicer cleavage sites from pre-miRNA sequences by integrating relational and categorical features, offering insight into positional determinants of enzymatic processing80. Additionally, methods such as gradient boosting classifiers have utilized in predicting cleavage sites for HIV-1 protease based on peptide sequence features and hybrid molecular descriptors, achieving high accuracy and F-scores in cross-validation settings81. These advancements offer a foundation for the rational prioritization of linker-payload combinations that are most likely to undergo efficient intracellular processing in the context of tumor-selective protease activity.

Moreover, the assessment of immunogenicity risk is increasingly being integrated into AI-driven ADC design workflows. While antibody immunogenicity is a primary concern, the linker or payload components, especially if they contain non-natural amino acids introduced during site-specific conjugation or novel chemical moieties, can also elicit immune responses. Computational tools like DeepImmuno82 and NetMHCpan83, originally developed for predicting peptide binding to MHC molecules (relevant for T-cell epitopes), have been adapted to evaluate the potential immunogenicity of linker structures or payload fragments. These in silico predictions support the early-stage filtering of immunologically reactive constructs that might activate T-cell responses or reduce the overall tolerability of the ADC, thereby guiding the design towards less immunogenic alternatives.

A key frontier in this area is applying AI to model the effects of DAR heterogeneity. Traditional conjugation methods generate mixtures of species (e.g., DAR 0, 2, 4, 6, 8), whereas site-specific approaches yield more uniform products. AI could be used to predict how the PK and toxicological properties of heterogeneous mixtures differ from those of homogeneous ADCs. Such insights would provide a stronger rationale for adopting advanced, site-specific manufacturing strategies despite their greater complexity.

Multi-objective optimization using reinforcement and transfer learning

Optimizing linker-payload systems for ADCs typically involves multiple, sometimes conflicting objectives: maximizing cytotoxicity while minimizing off-target toxicity, maintaining plasma stability while ensuring rapid intracellular release, and preserving antibody developability post-conjugation. To address this, AI frameworks employing multi-objective RL and transfer learning have been proposed84.

In RL-based approaches, agent networks are trained to iteratively propose linker-payload structures that maximize a composite reward function. This function often includes weighted terms for predicted IC50, predicted serum stability, predicted aggregation score, and synthetic accessibility84. For example, A related strategy was demonstrated in DeepFMPO, which used an actor-critic RL model with bidirectional LSTM networks to optimize molecules via fragment-level substitution. Guided by a reward function targeting clogP (2.0–3.0), PSA (40–60), and MW (320–420), the model generated 93% valid molecules and 33–38% that met all target criteria, demonstrating the efficiency of RL in navigating local chemical space for multiparameter optimization85. These models allow the exploration of chemical space beyond known linker-payload chemistries, facilitating innovation in scaffold and warhead design86.

Transfer learning has also been utilized to address data scarcity in specific payload classes, such as duocarmycins or DNA minor-groove binders. By pretraining models on general cytotoxic compound datasets and fine-tuning on limited ADC-specific data, researchers have achieved improvements in payload activity prediction with fewer than 200 labeled examples26. Such strategies are particularly valuable for developing new payload types with desirable properties (e.g., bystander effect, low immunogenicity, non-cross resistance).

Emerging approaches also incorporate physics-informed neural networks to simulate drug stability under dynamic physiological conditions, including shear stress, enzymatic degradation, and endosomal acidification87. While still under development, these models aim to bridge the gap between molecular design and in vivo behavior, improving the translational relevance of AI-driven predictions.

AI methods have introduced new capabilities for rationally designing linker-payload systems in ADCs. Generative models enable the in silico creation of novel payload analogs and cleavable linkers, while predictive algorithms assess how structural modifications affect conjugate stability, intracellular release, and immunogenicity88. Multi-objective optimization frameworks using RL and transfer learning strategies further enhance the ability to balance efficacy and toxicity in a systematic manner84. As datasets of validated linker-payload constructs continue to expand, and as experimental validation pipelines become increasingly integrated with computational platforms, AI is expected to play an expanding role in optimizing ADC conjugation chemistry for both efficacy and safety.

Beyond conventional cytotoxic agents, AI frameworks show strong potential for guiding the design of next-generation payloads. For example, AI could accelerate the development of immunostimulatory payloads, such as STING agonizts, by optimizing immune activation while preserving favorable drug-like properties. Likewise, generative models could be applied to create novel linker-payload combinations for emerging modalities like PROTAC-ADCs or radioactive drug conjugates, where optimization must account not only for potency but also for factors such as protein degradation kinetics or radionuclide stability.

AI in ADMET modeling for ADCs

Predicting the ADMET properties of ADCs is uniquely challenging due to their modular structure and complex in vivo behavior. AI is beginning to overcome these hurdles with deep learning architectures and multimodal data integration. These advanced models are improving the accuracy of PK predictions, offering new ways to forecast organ-specific toxicities, and enhancing mechanistic interpretability.

Deep learning for in vivo disposition modeling

Deep learning models are increasingly applied to predict PK parameters such as clearance (CL), volume of distribution (Vd), and tissue accumulation profiles, even for complex biotherapeutics like monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and ADCs89,90,91,92,93,94,95. For ADCs, these models must account for their modular structure, integrating diverse features such as antibody isotype (e.g., IgG1 vs. IgG4), Fc receptor binding affinities (which impact CL and immune effector functions), linker chemistry (cleavable vs. non-cleavable, hydrophilic vs. hydrophobic), and physicochemical properties of the payload (e.g., molecular weight, charge, and hydrophobicity index).

Recent studies have demonstrated that combining minimal physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (mPBPK) modeling with machine learning enables high-throughput exploration of antibody-target combinations. For example, Patidar et al. proposed a framework integrating mPBPK models with decision tree algorithms to predict target occupancy and optimize antibody design based on variables such as isoelectric point, surface charge, and binding affinity89. Additionally, PopPK-based neural network models trained on large datasets (e.g., >300 constructs) incorporating DAR, isoelectric point, and hydrophobicity indices have shown strong predictive performance for CL and Vd90. Although specific R² values for ADCs were not directly reported, methodologies similar to those described by Haraya et al. suggest that prediction of PK profiles using mechanistic and statistical modeling is feasible for both mAbs and ADCs90. Moreover, Irie et al. reported that hybrid frameworks combining Bayesian estimation from population PK with machine learning corrections (e.g., XGBoost) significantly improve predictions for biologics like infliximab in pediatric cohorts91. These models achieved lower RMSE and bias compared to standard PopPK methods, suggesting their value in capturing inter-individual variability by incorporating multimodal clinical features. These advances highlight the promise of AI-driven PopPK frameworks in ADC development. When trained on sufficient preclinical or clinical datasets, such models can outperform classical regression techniques and provide interpretable predictions of in vivo disposition, ultimately informing dose optimization and safety assessment.

To further capture the intricate structural complexity of ADCs, GNNs can be employed, particularly for modeling payload disposition. GNNs can encode molecular substructures of the linker and payload, as well as the specific conjugation sites on the antibody, as graph-based representations. Complementary to GNNs, CNNs, when trained on 3D imaging data (e.g., PET/CT scans from preclinical biodistribution studies), have also been used to predict organ-specific uptake of ADCs96 (Fig. 2). A notable example is the study by de Vries et al., who developed a 3D U-Net-style CNN model for denoising low-count PET scans obtained using radiolabeled antibodies, including [89Zr]-rituximab. Their CNN significantly improved tumor detectability, signal-to-noise ratio, and clinical acceptability over classical methods such as Gaussian smoothing and bilateral filtering. This approach supports translational applications by enabling the forecasting of human tissue distribution patterns from preclinical datasets, potentially identifying sites of off-target accumulation early in development.

A Graph Neural Network (GNN) for Molecular-Level Pharmacokinetic (PK) Prediction of ADCs. The ADC molecule, comprising a monoclonal antibody, a linker, and a cytotoxic payload, is initially represented as a graph where atoms are nodes and chemical bonds are edges. This graph is then processed by a GNN core architecture, utilizing message-passing mechanisms among nodes (e.g., from neighboring nodes ①-④ to a central Target Node) to learn complex molecular features. The GNN subsequently outputs predicted key PK parameters, such as clearance (CL), volume of distribution (Vd), and tissue accumulation profiles, thereby facilitating in silico ADC design optimization. B 3D U-Net Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for Preclinical Biodistribution Imaging. Low-count 3D PET/CT images, representing raw biodistribution data, are fed into a 3D U-Net model. The U-Net’s encoder path (blue blocks) performs sequential 3D convolution and max pooling for hierarchical feature extraction and down-sampling, while the decoder path (green blocks) utilizes 3D up-convolution for feature reconstruction and up-sampling. Skip connections (dashed lines) bridge corresponding resolution levels between the encoder and decoder paths, integrating high-resolution spatial information. The primary function of this model here is denoising these 3D volumetric data, yielding a high-quality denoised 3D PET/CT image to enable more accurate quantification of ADC distribution and identification of potential off-target accumulation.

Multimodal AI models for toxicity prediction

Predicting toxicity remains a major bottleneck in ADC development, especially with class-specific on-target, off-tumor effects and payload-driven off-target adverse events. Dose-limiting toxicities such as keratopathy (ocular toxicity), interstitial lung disease (ILD), and myelosuppression are now recognized as hallmark adverse events for specific ADC classes, frequently leading to clinical trial failures or restricted therapeutic windows. These adverse events often result from a combination of factors, including off-target payload release (due to linker instability or non-specific cleavage), uptake of the ADC by Fc receptor-bearing immune cells in healthy tissues, or unanticipated tissue accumulation of the payload or its metabolites. Traditional toxicity models that rely heavily on animal data often fail to accurately predict human-specific toxicities, necessitating more sophisticated approaches.

To address this gap, AI researchers have been exploring multimodal deep learning frameworks that integrate diverse data sources across biological scales97,98. For instance, a study by Abdul Karim et al. introduced a multimodal deep learning method for toxicity prediction, utilizing various neural network architectures and data representations, including chemical structures and numerical features. This approach achieved improved accuracy levels over traditional methods, demonstrating the potential of integrating multiple data modalities for toxicity assessment99. Similarly, a multi-task deep neural network was developed to simultaneously predicting in vitro, in vivo, and clinical toxicity by incorporating both Morgan fingerprints and pre-trained SMILES embeddings as input, achieving an AUC-ROC of 0.991 for clinical toxicity on the ClinTox dataset97. Importantly, they applied a contrastive explanation method to identify substructural motifs responsible for toxic or non-toxic classifications, providing not only accurate predictions but also interpretable molecular rationales that could guide ADC payload design.

NLP methods have also made significant contributions, particularly in the realm of post-market safety surveillance and learning from existing clinical data. Using advanced NLP tools such as BioBERT100 and ClinicalBERT101, researchers have successfully mined large databases of EHRs and adverse event reporting systems (e.g., FDA Adverse Event Reporting System—FAERS) to identify rare or emerging ADC-associated adverse events that may not have been apparent during clinical trials. For example, Zitu et al. evaluated the generalizability of various machine learning and deep learning models, including SVM, BiLSTM, CNN, BERT, and ClinicalBERT across two independently annotated EHR corpora for adverse drug event (ADE) detection. Among all models tested, ClinicalBERT consistently achieved the highest F1-scores (0.78–0.87) in both intra- and inter-dataset settings, indicating strong cross-domain robustness for mining ADE-drug relations directly from unstructured clinical notes102. Their work demonstrates that domain-adapted language models can serve as accurate and scalable tools for pharmacovigilance. For ADCs, such tools could be deployed for post-market monitoring to detect early safety signals for rare but serious events like ILD, or to analyze prescribing patterns and outcomes in real-world patient populations who may not have met the strict eligibility criteria of pivotal clinical trials.

Enhancing interpretability and generalizability with GNNs and transformers

One of the persistent challenges in applying AI to biotherapeutic ADMET modeling, especially in regulatory contexts were understanding the “why” behind a prediction is crucial, is model interpretability. While complex models like deep neural networks can achieve high predictive accuracy, their “black-box” nature can hinder trust and adoption. GNNs and transformer architectures have emerged as powerful solutions that can offer improved interpretability alongside strong predictive performance, particularly for modular molecules like ADCs.

GNNs, by their very nature, model ADCs as graphs composed of interconnected antibody, linker, and payload units. This graphical representation allows for the attribution of predicted toxicity or CL characteristics back to specific components or substructures within the ADC. Using techniques like integrated gradients or attention mechanisms within the GNN, it has been shown, for example, that linker hydrophobicity and the flexibility of the conjugation site are dominant contributors to the hepatic accumulation of certain ADCs.

Similarly, transformer models, such as MoLFormer103 or BioTransformer104, represent ADCs as sequences of functional units (e.g., antibody domains, linker moieties, payload pharmacophores) and generate contextual embeddings for each module. The attention maps generated by these models could pinpoint key molecular features or properties contributing to this risk, such as the payload’s efflux potential or interactions with specific Fc receptors. Crucially, transformer-based systems excel at in silico “what-if” scenarios (counterfactual analysis). They allow researchers to ask specific design questions, such as “What would be the predicted change in toxicity if we replace this payload but keep the linker and antibody constant?” and receive quantitative predictions. This ability to computationally assess the ADMET consequences of specific structural modifications is invaluable for rational and iterative ADC design. Furthermore, it improves the defensibility of candidate molecules in regulatory submissions by providing a clearer rationale for design choices and predicted safety profiles.

In conclusion, AI is significantly transforming ADMET modeling for ADCs by enabling more accurate, scalable, and mechanistically informed predictions across a range of PK and toxicological endpoints. Deep learning, graph-based modeling, and multimodal frameworks are particularly well-suited to handle the modular complexity and heterogeneous nature of ADCs, while advanced architectures like transformers offer a promising path towards enhanced interpretability and flexible design exploration. As curated, ADC-specific ADMET datasets continue to expand and as community-driven benchmarking initiatives emerge, these AI-driven models will become increasingly central to the preclinical assessment, candidate prioritization, and ultimately, the successful clinical translation of next-generation ADCs.

AI in preclinical and clinical development of ADCs

While ADCs are advancing rapidly, translating their preclinical promise into clinical benefit remains a formidable challenge, hampered by narrow therapeutic indices and complex, often unpredictable pharmacology. Consequently, the application of AI in the clinical development of ADCs is considerably more nascent compared to its use in small molecules or checkpoint inhibitors. The unique failure modes of ADCs, including bystander toxicity, off-target payload release, and complex resistance mechanisms, necessitate bespoke AI models that are not yet mature. Nonetheless, early yet compelling studies in patient stratification and response prediction are demonstrating AI’s potential to navigate this complexity, offering a glimpse into a future of more personalized and efficient ADC clinical trials (Table 3)105,106.

AI for biomarker discovery and patient stratification

A cornerstone of precision oncology is matching the right patient to the right treatment107. For ADCs, this extends beyond single-gene biomarkers to complex signatures reflecting target accessibility, internalization capacity, and tumor microenvironment factors. ADC-specific AI applications are emerging, primarily in the analysis of digital pathology and multi-omics data. For example, a quantitative continuous scoring (QCS) model trained on TROP2 IHC-stained whole-slide images from NSCLC biopsies successfully stratified patients for datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) treatment. Crucially, the model went beyond simple TROP2 expression levels, identifying membrane-to-cytoplasm expression patterns as a key predictive feature for clinical response108. Similarly, a random forest model trained on data from 998 HER2-low breast cancer patients identified a multi-feature signature, including PR status and Ki67 levels, alongside HER2 expression, that could help refine patient selection for T-DXd therapy beyond the current IHC-based criteria109. These examples highlight AI’s strength in uncovering complex, multi-modal biomarkers that traditional, single-analyte approaches might miss.

It is important, however, to distinguish these data-driven AI approaches from mechanistic models like quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP). QSP models simulate the biological interactions of a drug based on physiological principles110. While not AI themselves, they can be powerfully combined with machine learning to create hybrid models111. For instance, a QSP model could simulate ADC distribution and payload release, with its outputs then used as features in a machine learning model to predict individual patient outcomes. This synergy between mechanistic simulation and data-driven pattern recognition represents a powerful future direction for personalizing ADC therapy.

AI-based digital twin systems are being explored to simulate individual patient responses to ADCs by integrating in silico PK/PD models with imaging and molecular data112,113. In one example, a digital twin platform based on a QSP model was used to simulate clinical responses to mosunetuzumab, an anti-CD20/CD3T—cell engaging bispecific antibody, in virtual cohorts of NHL patients, enabling prediction of tumor reduction across dosing regimens and identification of biomarker-defined subgroups110.

In addition to efficacy, AI models are being developed to forecast resistance mechanisms114,115. For instance, an XGBoost model incorporating gene expression features related to the cGAS-STING pathway accurately predicted anti-PD-1/PD-L1 response in hepatocellular carcinoma, achieving AUCs of 0.777 in the training cohort and 0.789 in an independent validation set. SHAP analysis further identified key immune-related pathways contributing to treatment responsiveness, offering interpretable insights into the model’s decision process114.

AI-assisted decision support for ADC trial design

Designing clinical trials for ADCs is notoriously difficult due to their unique dose-toxicity relationship and the challenge of defining an optimal therapeutic window116,117. While still largely conceptual for ADCs, AI offers several potential avenues to improve trial design118,119.

RL frameworks, for example, have been explored in simulations to optimize dose-escalation schemes in Phase I/II trials. An RL agent could potentially learn an adaptive dosing strategy that maximizes efficacy while keeping toxicity below a predefined threshold, navigating the narrow therapeutic window of ADCs more effectively than traditional 3 + 3 designs120,121.

Furthermore, AI tools have been developed to predict the probability of technical s and regulatory success (PTRS) of a clinical trial by integrating preclinical data, biomarker prevalence, and competitive landscape information122,123,124. For instance, Insilico Medicine developed a deep learning pipeline that predicted phase I/II trial outcomes by modeling drug-induced side effects and pathway activation to train a clinical success classifier122. For an ADC, such a model would need to be trained on ADC-specific features, such as linker stability data and payload-related toxicity profiles, to provide meaningful predictions.

Finally, AI-powered analysis of real-world evidence (RWE) holds promise for optimizing trial design, for instance by using NLP to mine EHRs to identify patient populations with high unmet need or to model disease progression in the absence of treatment125,126. This could inform inclusion/exclusion criteria or help justify the use of external control arms in future ADC trials.

Transferable lessons from AI in other oncology trials

Although large-scale AI applications in ADC clinical trials are still at an early stage, important insights can be drawn from the more established use of AI in small-molecule drugs and other biologics. These cases provide methodological frameworks that can be adapted to address the unique challenges of ADC development.

One promising strategy is model-informed precision dosing (MIPD). As emphasized by the FDA’s Project Optimus, MIPD shifts dosing away from traditional body-surface-area-based approaches toward model-guided personalization. While first applied to small molecules such as the RET inhibitor selpercatinib, the MIPD framework is highly relevant to ADCs. An AI-enhanced MIPD system could integrate patient-specific factors data (e.g., renal function, tumor burden, target expression level) to recommend a personalized dose aimed at optimizing the therapeutic window75,127,128,129.

Another transferable methodology is the use of AI-guided synthetic control arms (SCAs). SCAs, constructed from matched historical or real-world patient cohorts, have been successfully used in small-molecule trials to supplement or replace traditional control arms, accelerating drug development particularly in rare diseases130. For ADCs targeting niche indications with limited patient pools, this AI-driven approach could be a pivotal strategy to improve trial feasibility and efficiency.

These examples demonstrate that while the biological inputs for ADC models will be unique (e.g., payload metabolism, bystander effect variables), the AI-driven strategies for personalizing dose and optimizing trial design are highly transferable. Adopting these proven methodologies will be crucial for accelerating the clinical translation of next-generation ADCs.

In summary, AI has begun to play a supportive and increasingly central role in the clinical development of ADCs. From response prediction and patient stratification to dose optimization and trial simulation, AI tools have demonstrated utility in improving decision-making efficiency, personalizing treatment, and potentially reducing development costs. While challenges remain, particularly regarding data standardization, regulatory validation, and mechanistic transparency, early applications suggest that lessons learned from small-molecule programs can be transferred to ADCs with careful adaptation48. Continued progress in digital twins, biomarker discovery, and RWD integration will further enhance AI’s contribution to ADC clinical translation131,132,133,134.

Challenges and future perspectives

The integration of AI into the ADC development pipeline is highly promising but not without limitations. Unlocking its full potential requires addressing challenges that range from data quality and algorithmic constraints to the complexities of clinical application and regulatory approval. Below, we highlight these key hurdles and outline a roadmap toward a more mature, AI-driven framework for ADC innovation.

Foundational challenges: data, algorithms, and validation

The primary barriers to progress are foundational, concerning the quality of inputs and the reliability of models.

First, the field is hampered by ADC-specific data scarcity. Unlike small molecules, for which vast public databases like ChEMBL69 exist, ADC data are fragmented, often proprietary, and lack standardized annotation. A robust dataset would need to capture the full multipartite structure (antibody sequence, linker chemistry, payload mechanism, conjugation site, and DAR), along with corresponding ADMET and clinical outcomes135,136,137. This scarcity is exacerbated by survivorship bias, as failed ADC candidates are rarely reported. Recognizing this critical gap, the recent development of ADCdb represents a landmark first step in centralizing ADC information138. By systematically curating data on over 6500 ADCs, including their structural components and thousands of reported biological activities, ADCdb provides the community with its first dedicated, large-scale resource for computational modeling. However, it also highlights the ongoing challenge: much of the deeply detailed preclinical (e.g., full PK profiles) and clinical trial data remains outside the public domain.

Second, this data limitation directly impacts model generalizability and interpretability. Models trained on narrow datasets struggle to extrapolate across the vast chemical and biological space of potential ADCs and often function as “black boxes”139. While tools like SHAP and attention mechanisms offer glimpses into a model’s decision-making, their outputs are not always mechanistically actionable for an ADC chemist or biologist137,140. For high-stakes decisions, particularly concerning toxicities like keratopathy or ILD, a prediction without a clear, verifiable biological rationale is of limited translational value141,142.

Third, a lack of standardized validation frameworks and benchmarks hinders progress. How should an AI model for ADC design be rigorously evaluated? Prospective experimental validation is the gold standard, but is slow and expensive. There is a pressing need for community-accepted benchmark datasets and retrospective validation studies to objectively compare different models and build confidence in their predictive power.

Translational challenges: clinical and regulatory acceptance

Beyond foundational issues, translating AI-driven insights into clinical practice faces significant hurdles. Clinician and stakeholder trust is paramount. A physician is unlikely to enroll a patient in a trial based on an opaque algorithmic recommendation. Therefore, developing human-understandable, explainable AI (XAI) interfaces that can present predictions alongside supporting evidence is crucial for clinical adoption.

Furthermore, the regulatory landscape for AI in drug development is still evolving. While agencies like the FDA have issued guidance for AI/ML-based software as a medical device, clear frameworks for evaluating AI-generated molecules or AI-guided clinical trial designs are still being established143,144,145. Demonstrating the robustness, fairness, and causality of AI models to regulators will be a key step in moving from in silico promise to approved medicines.

Future perspective: building an ADC intelligent discovery ecosystem

Overcoming these challenges requires a concerted effort to build an integrated ecosystem for AI-driven ADC discovery. This ecosystem will rest on three strategic pillars:

The first pillar is a robust, open data foundation. The launch of resources like ADCdb provides the foundational layer, but the ultimate vision is a global “ADC Commons”138,146. Governed by FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable), this initiative would aim to consolidate multi-modal data, from molecular structures and preclinical results to anonymized clinical outcomes, from both successful and failed ADC programs, perhaps through industry-academia consortia147. Such a resource would not only open for training data but also serve as a gold standard for model benchmarking.

The second pillar is the development of purpose-built, multimodal AI architectures. Instead of adapting models from other fields, the future lies in creating hybrid models, such as graph-transformer networks, specifically designed to understand the tripartite nature of ADCs148. These models must be capable of integrating diverse data types, from AlphaFold-predicted structures and spatial transcriptomics to clinical imaging data, to build a holistic, systems-level understanding of ADC behavior149.

The final and most crucial pillar is closing the loop between prediction and experimentation. The ultimate goal is to create automated “self-driving” laboratories where AI models propose novel ADC candidates, which are then synthesized and tested by high-throughput robotics and organ-on-a-chip platforms. The experimental results are fed back in real-time to refine the AI models, creating a virtuous cycle of DBTL that can dramatically accelerate the discovery of next-generation ADC therapies150.

In conclusion, while significant hurdles remain, the path forward is clear. By systematically building a foundation of open data, developing purpose-built AI, and integrating it into closed-loop experimental systems, the field can move beyond using AI as a optimization tool. The ultimate vision is a fully integrated, intelligent discovery ecosystem that will enable the rational, scalable, and personalized development of safer and more effective ADC therapies for patients in need.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are available within the article.

References

Dumontet, C., Reichert, J. M., Senter, P. D., Lambert, J. M. & Beck, A. Antibody–drug conjugates come of age in oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 641–661 (2023).

Tsuchikama, K., Anami, Y., Ha, S. Y. Y. & Yamazaki, C. M. Exploring the next generation of antibody–drug conjugates. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 21, 203–223 (2024).

Liu, K. et al. A review of the clinical efficacy of FDA-approved antibody‒drug conjugates in human cancers. Mol. Cancer 23, 62 (2024).

Colombo, R., Tarantino, P., Rich, J. R., Lorusso, P. M. & de Vries, E. G. E. The journey of antibody–drug conjugates: lessons learned from 40 years of development. Cancer Discov. 14, 2089–2108 (2024).

Li, B. T. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in HER2 -mutant non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 241–251 (2022).

Shitara, K. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive gastric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 2419–2430 (2020).

Modi, S. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 9–20 (2022).

Geyer, C. E. et al. Survival with trastuzumab emtansine in residual HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 249–257 (2025).

Lee, H. J. et al. Brentuximab vedotin, nivolumab, doxorubicin, and dacarbazine for advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 145, 290–299 (2025).

Ceci, C., Lacal, P. M. & Graziani, G. Antibody-drug conjugates: resurgent anticancer agents with multi-targeted therapeutic potential. Pharmacol. Ther. 236, 108106 (2022).

Drago, J. Z., Modi, S. & Chandarlapaty, S. Unlocking the potential of antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 327–344 (2021).

Jiang, M., Li, Q. & Xu, B. Spotlight on ideal target antigens and resistance in antibody-drug conjugates: strategies for competitive advancement. Drug Resist. Updat. 75, 101086 (2024).

Su, Z. et al. Antibody–drug conjugates: recent advances in linker chemistry. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11, 3889–3907 (2021).

Conilh, L., Sadilkova, L., Viricel, W. & Dumontet, C. Payload diversification: a key step in the development of antibody–drug conjugates. J. Hematol. Oncol. 16, 3 (2023).

Wang, Z., Li, H., Gou, L., Li, W. & Wang, Y. Antibody–drug conjugates: recent advances in payloads. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 13, 4025–4059 (2023).

Izzo, D. et al. Innovative payloads for ADCs in cancer treatment: moving beyond the selective delivery of chemotherapy. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 17, 17588359241309461 (2025).

Li, S. et al. Resistance to antibody–drug conjugates: a review. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 15, 737–756 (2025).

Paul, D. et al. Artificial intelligence in drug discovery and development. Drug Discov. Today 26, 80–93 (2021).

Mullowney, M. W. et al. Artificial intelligence for natural product drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 895–916 (2023).

Jayatunga, M. K. P., Xie, W., Ruder, L., Schulze, U. & Meier, C. AI in small-molecule drug discovery: a coming wave? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 175–176 (2022).

Chan, H. C. S., Shan, H., Dahoun, T., Vogel, H. & Yuan, S. Advancing drug discovery via artificial intelligence. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 40, 592–604 (2019).

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29, 1930–1940 (2023).

Zhang, K. et al. Artificial intelligence in drug development. Nat. Med. 31, 45–59 (2025).

Cai, Y. et al. Artificial intelligence applied in neoantigen identification facilitates personalized cancer immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 12, 1054231 (2023).

Notin, P., Rollins, N., Gal, Y., Sander, C. & Marks, D. Machine learning for functional protein design. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 216–228 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. ADCNet: a unified framework for predicting the activity of antibody-drug conjugates. Brief. Bioinform. 26, bbaf228 (2025).

Bhinder, B., Gilvary, C., Madhukar, N. S. & Elemento, O. Artificial intelligence in cancer research and precision medicine. Cancer Discov. 11, 900–915 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. The Icarian flight of antibody-drug conjugates: target selection amidst complexity and tackling adverse impacts. Protein Cell 16, 532–556 (2025).

Razzaghdoust, A. et al. Data-driven discovery of molecular targets for antibody-drug conjugates in cancer treatment. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2670573 (2021).

Fang, J. et al. The target atlas for antibody-drug conjugates across solid cancers. Cancer Gene Ther. 31, 273–284 (2024).

Kathad, U. et al. Expanding the repertoire of Antibody Drug Conjugate (ADC) targets with improved tumor selectivity and range of potent payloads through in-silico analysis. PLoS ONE 19, e0308604 (2024).

Kamya, P. et al. PandaOmics: an AI-driven platform for therapeutic target and biomarker discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 64, 3961–3969 (2024).

Boxer, E. et al. Emerging clinical applications of single-cell RNA sequencing in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-025-01003-3 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Advances and applications in single-cell and spatial genomics. Sci. China. Life Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-024-2770-x (2024).

Xiang, Y., Jin, Y., Liu, K. & Wei, B. Mapping the patent landscape of TROP2-targeted biologics through deep learning: patents. Nat. Biotechnol. 43, 491–500 (2025).

Jin, W., Chen, J., Li, Z., Yubiao, Z. & Peng, H. Bayesian-optimized deep learning for identifying essential genes of mitophagy and fostering therapies to combat drug resistance in human cancers. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 29, e18254 (2025).

Shi, X. et al. Integrative molecular analyses define correlates of high B7-H3 expression in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. npj Precis. Oncol. 6, 80 (2022).

Bai, G. et al. Accelerating antibody discovery and design with artificial intelligence: recent advances and prospects. Semin. Cancer Biol. 95, 13–24 (2023).

Yu, S. et al. Integrating inflammatory biomarker analysis and artificial-intelligence-enabled image-based profiling to identify drug targets for intestinal fibrosis. Cell Chem. Biol. 30, 1169–1182.e8 (2023).

Tran, T. A. et al. Combining machine learning with high-content imaging to infer ciprofloxacin susceptibility in isolates of Salmonella Typhimurium. Nat. Commun. 15, 5074 (2024).

Ha, K. D., Bidlingmaier, S. M., Zhang, Y., Su, Y. & Liu, B. High-content analysis of antibody phage-display library selection outputs identifies tumor selective macropinocytosis-dependent rapidly internalizing antibodies. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 13, 3320–3331 (2014).

Luo, R. et al. BioGPT: generative pre-trained transformer for biomedical text generation and mining. Brief. Bioinform. 23, bbac409 (2022).

Gu, Y. et al. Domain-specific language model pretraining for biomedical natural language processing. ACM Trans. Comput. Healthc. 3, 1–23 (2022).

Zeng, L. et al. Tuning immune-cold tumor by suppressing USP10/B7-H4 proteolytic axis reinvigorates therapeutic efficacy of ADCs. Adv. Sci. 11, e2400757 (2024).

Beck, A., Goetsch, L., Dumontet, C. & Corvaïa, N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 315–337 (2017).

Joubbi, S. et al. Antibody design using deep learning: from sequence and structure design to affinity maturation. Brief. Bioinform. 25, bbae307 (2024).

Graves, J. et al. A review of deep learning methods for antibodies. Antibodies 9, 12 (2020).

Sobhani, N., D’Angelo, A., Pittacolo, M., Mondani, G. & Generali, D. Future AI will most likely predict antibody-drug conjugate response in oncology: a review and expert opinion. Cancers 16, 3089 (2024).

Noriega, H. A. & Wang, X. S. AI-driven innovation in antibody-drug conjugate design. Front. Drug Discov. 5, 1628789 (2025).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Yang, Z., Zeng, X., Zhao, Y. & Chen, R. AlphaFold2 and its applications in the fields of biology and medicine. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 115 (2023).

Baek, M. et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 373, 871–876 (2021).

Ruffolo, J. A., Sulam, J. & Gray, J. J. Antibody structure prediction using interpretable deep learning. Patterns 3, 100406 (2022).

Liao, C. Y. et al. CD3xHER2 bsAb-mediated activation of resting T-cells at HER2 positive tumor clusters is sufficient to trigger bystander eradication of distant HER2 negative clusters through IFNγ and TNFα. Eur. J. Immunol. 55, e202451589 (2025).

Dumet, C., PugniŠre, M., Henriquet, C., Gouilleux-Gruart, V., Poupon, A. & Watier, H. Harnessing Fc/FcRn affinity data from patents with different machine learning methods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 5724 (2023).

Hale, G. Living in LALA land? Forty years of attenuating Fc effector functions. Immunol. Rev. 328, 422–437 (2024).

Rives, A. et al. Biological structure and function emerge from scaling unsupervised learning to 250 million protein sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 118, e2016239118 (2021).

Hao, X. & Fan, L. ProtT5 and random forests-based viscosity prediction method for therapeutic mAbs. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 194, 106705 (2024).

Li, B., Yang, Y. T., Capra, J. A. & Gerstein, M. B. Predicting changes in protein thermodynamic stability upon point mutation with deep 3D convolutional neural networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1008291 (2020).

Hon, J. et al. SoluProt: prediction of soluble protein expression in Escherichia coli. Bioinformatics 37, 23–28 (2021).

Cun, Y. et al. SITA: predicting site-specific immunogenicity for therapeutic antibodies. J. Pharm. Anal. 15, 101316 (2025).

Zhou, C. et al. SEPPA 3.0 - enhanced spatial epitope prediction enabling glycoprotein antigens. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W388–W394 (2019).

Høie, M. H. et al. DiscoTope-3.0: improved B-cell epitope prediction using inverse folding latent representations. Front. Immunol. 15, 1322712 (2024).

Prihoda, D. et al. BioPhi: a platform for antibody design, humanization, and humanness evaluation based on natural antibody repertoires and deep learning. MAbs 14, 2020203 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. SEPPA: a computational server for spatial epitope prediction of protein antigens. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W612–W616 (2019).

Ducry, L. & Stump, B. Antibody-drug conjugates: linking cytotoxic payloads to monoclonal antibodies. Bioconjug. Chem. 21, 5–13 (2010).

Huang, J. et al. Structure-inclusive similarity based directed GNN: a method that can control information flow to predict drug-target binding affinity. Bioinformatics 40, btae563 (2024).

Therrien, F., Sargent, E. H. & Voznyy, O. Using GNN property predictors as molecule generators. Nat. Commun. 16, 4301 (2025).

Gaulton, A. et al. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1100–D1107 (2012).

Irwin, J. J., Sterling, T., Mysinger, M. M., Bolstad, E. S. & Coleman, R. G. ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 1757–1768 (2012).

Bagal, V., Aggarwal, R., Vinod, P. K. & Priyakumar, U. D. MolGPT: molecular generation using a transformer-decoder model. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 2064–2076 (2022).

Chithrananda, S., Grand, G. & Ramsundar, B. ChemBERTa: large-scale self-supervised pretraining for molecular property prediction. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2010.09885 (2020).

Shi, C. et al. Graphaf: a flow-based autoregressive model for molecular graph generation. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2001.09382 (2020).

Gebauer, N. W. A., Gastegger, M., Hessmann, S. S. P., Müller, K. R. & Schütt, K. T. Inverse design of 3d molecular structures with conditional generative neural networks. Nat. Commun. 13, 973 (2022).

Gómez-Bombarelli, R. et al. Automatic chemical design using a data-driven continuous representation of molecules. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 268–276 (2018).