Abstract

The classification of breast cancer (BC) based on HER2 expression is undergoing significant changes. While traditional approaches have focused on HER2-positive and HER2-negative categories, emerging evidence highlights varied therapeutic responses depending on the level of HER2 protein expression. Breast cancers are now immunohistochemically (IHC) scored into five subgroups, which define two primary therapeutic groups: HER2-positive (IHC 2+ amplified and 3 + ) and HER2-negative (IHC 0, 1 + , and 2+ non-amplified). Recent advances, particularly in antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), have led to further subclassification of HER2-negative BC into HER2-Low and HER2-null (IHC 0). Also, for HER-positive subgroups, a differential response to HER2-targeted therapies is seen. This evolving landscape challenges the traditional use of HER2 as a diagnostic marker and underscores the need for a deeper understanding of HER2 biology. This review addresses these complexities, focusing on the emerging HER2-Low and Ultralow subtypes, and evaluates the distinct therapeutic responses across the spectrum of HER2 expression in different BC subtypes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

HER2 protein is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) of the tyrosine kinase family and forms heterodimers with other ligand-bound EGFR family members such as HER3 and HER4, which activates downstream signalling pathways to promote cell proliferation, cell invasion, angiogenesis and to protect cells against apoptosis (Fig. 1)1,2,3. Normal tissues have a low complement of HER2 membrane protein. Breast cancer (BC) tissue may have up to 25–50 copies of the HER2 gene and up to 40–100 fold increase in HER2 protein resulting in up to 2 million receptors expressed at the tumour cell surface4. Although HER2 overexpression confers a poor prognosis (due to the effect on cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and survival, all hallmarks of cancer), it offers a unique opportunity to utilise oncogenic therapies that target HER2, improving BC patient outcome5.

Created with BioRender.com.

In diagnostic pathology, the HER2 status of a breast tumour is assessed using a combination of immunohistochemistry (IHC) to evaluate HER2 protein expression levels, and/or in situ hybridisation (ISH) to assess HER2 gene status, the only two techniques currently validated for clinical use6,7. HER2 positivity in BC is defined as protein overexpression (IHC score 3 + ) or HER2 equivocal protein expression (IHC score of 2 + ) with evidence of HER2 gene amplification on ISH reflex testing6. This scoring system was developed to predict response to anti-HER2 therapies such as trastuzumab8 that showed efficacy limited to patients with HER2-positive BC. According to this definition, tumours with equivocal HER2 expression without evidence of HER2 gene amplification and tumours with low or undetectable levels of HER2 protein (IHC score 1+ or 0, respectively) are defined as HER2 negative to reflect the lack of response to anti-HER2 targeted therapies including trastuzumab and the antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1)9. Recently, the historical HER2 negative group has been sub-classified into 2 subgroups; HER2-Low (IHC score 1 + , and 2 + /ISH-negative) and HER2 0 (IHC score 0) to reflect the difference in potential response to the novel HER2-based ADC therapy (trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd)).

T-DXd, which delivers potent cytotoxic agents to cells with low HER2 levels, has opened a new therapeutic option for this BC patient population and has led to recognition of the concept of HER2-Low BC9,10,11. Fig. 2 provides a chronological outline of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals of ADCs for the treatment of BC.

The spectrum of HER2 expression in BC is evolving. The introduction of the HER2-Low category and the HER2-Ultralow categories has created challenges regarding the significance of the various HER2 categories with regard to potential benefit from adjuvant/neoadjuvant treatment. Furthermore, national guideline recommendations currently vary in their approach to the definition and classification of such new entities12,13.

Regarding the other end of HER2 expression spectrum, there is also increasing evidence that HER2-positive BCs show differential response rates to anti-HER2 targeted therapies due to various factors, including the level of HER2 protein expression (overexpression (3 + ) versus equivocal protein expression (2 + ) with HER2 gene amplification14, in addition to the effect of concomitant ER expression. This has raised the question as to whether treatment regimes that target HER2 oncogenic activity or ADC-based regimes are more appropriate for patients with HER2 2 + /ISH-positive BC.

These complexities highlight the need for further understanding of the complexities of HER2 biology in BC and the consequent implications for treatment. This review examines the evidence gaps and focuses on HER2-Low and Ultralow tumours and evaluates the different therapeutic responses across the spectrum of HER2 expression in different BC subgroups.

HER2-low BC

Based on the results of the DESTINY-Breast04 trial15, The FDA approved the use of the HER2-based ADC, T-DXd, for the treatment of HER2-Low BC. T-DXd showed significant benefit to patients with metastatic HER2-Low BC (mBC), using the current HER2 scoring system (IHC 1+ or 2 + /ISH-negative. Although the HER2-Low BC class has attracted considerable attention in the BC community as a novel therapeutic group of BC, concerns have been raised regarding the validity of the current HER2 companion diagnostic in the identification of these tumours. According to current criteria, approximately 15–20% of BCs are HER2-positive16,17,18,19,20, 40–60% show lower levels of HER2 protein (HER2-Low) and the remaining BCs (20–45%) lack HER2 expression (IHC score 0), with variation in reported rates in different studies. The HER2-Low category, therefore, comprises a large group of BC patients, approximately 60% of whom have hormone receptor (HR) positive tumours and 40% are HR-negative21.

Studies aimed at deciphering the biological and clinical significance of HER2-Low BC were carried out to characterise these tumours further5,22,23,24,25,26,27, and most of these concluded that HER2-Low BC appears to be a heterogeneous disease5,28 With regard to its clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular characteristics23,29,30,31,32. Whether HER2-Low BC constitutes a distinct biological entity with specific prognostic and therapeutic implications, possibly influenced by HR status, remains controversial33,34,35.

In a previous study, our group concluded that HER2-Low tumours are predominantly of luminal subtype when HR-positive, while if HR-negative, these tumours have a different immunophenotype and are predominantly of luminal ‘androgen-like’ molecular subtype. In HR-negative BC, HER2-Low BC patients appear to have improved outcomes and are less responsive to neoadjuvant chemotherapy36.

Irrespective of the ongoing debate regarding the biological significance of HER2-Low phenotype, the clinical relevance of these tumours stems from the presence of HER2 protein on the cell surface of BC cells rather than from the oncogenic activity of the protein. In these tumours, T-DXd15,37 utilises HER2 as a surface protein to deliver the cytotoxic payload rather than targeting the HER2 oncogene pathway, the mechanism utilised by trastuzumab and related agents36.

The dilemma of HER2-Ultralow

The response of BC patients with low levels of HER2 protein (including the 1+ category) to T-DXd has led some to expand the definition of BC expressing very low levels of HER2 protein not meeting the IHC 1+ threshold, to a new category called HER2-Ultralow38. The oncology and research communities argued that any level of HER2 expression, regardless of its detection using IHC, may be sufficient to elicit an anti-tumour response by T-DXd. One of the major current concerns is the definition of the lowest level of HER2 expression in BC at which T-DXd is effective. In the DESTINY-Breast06 trial, T-DXd was compared with the investigator’s choice of chemotherapy in patients with HR-positive mBC, including those with HER2-Ultralow BC (n = 153) (defined as HER2 IHC membrane staining but less than score 1 + ) and those with HER2-Low BC (n = 713)37. The study demonstrated that T-DXd significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared to the investigator’s choice of chemotherapy in patients with HER2-Low disease (median PFS was 13.2 months for T-DXd (n = 359) compared to 8.1 months in the chemotherapy group (n = 354; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.51–0.74; P < 0.0001). In the intention-to-treat population, which included patients with both HER2-Low and HER2-Ultralow disease, the median PFS was consistent across both treatment arms (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.53–0.75; P < 0.0001)37. However, the difference in the PFS in the HER2-Ultralow group appeared to be statistically not significant between T-DXd (n = 76 patients) and chemotherapy (n = 76 patients) (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.50–1.21).

While we appreciate the need to broaden the group of mBC patients who may benefit from T-DXd, and the enthusiasm surrounding the exploration of tumours expressing very low levels of HER2 protein, termed HER2-Ultralow, it is important to recognise the potential disadvantages of this approach. Introducing a new HER2 category at this point may add unnecessary complexity to the identification of such tumours in routine practice. The introduction of a new category to classify HER2-Low/Ultralow tumours, based on any degree of membrane staining, whether complete or incomplete, and present in as few as a single cell up to 9% of tumour cells, may reduce reproducibility and increase interobserver variability. It also raises the question of how many tumour tissue blocks should be examined to confidently determine that a tumour is truly HER2-null. Furthermore, distinguishing between true HER2 staining and technical or staining artefacts presents a significant challenge for pathologists.

If the concept of HER2-Ultralow BC is to be introduced into clinical practice, more evidence from randomised clinical trials is required to confirm that these tumours respond to T-DXd more effectively than completely HER2 IHC 0 tumours (HER2 null). Should data indicate a response of HER2 null tumours to ADC therapy, all patients will be eligible for such treatment without the need for HER2 scoring for selection for this form of treatment.

Another key question is whether HER2 IHC 0 tumours fall within the scope of the T-DXd treatment paradigm. As emerging data begin to shed light on the response of HER2 score 0 BCs, conclusive evidence is still needed to support a meaningful distinction between IHC 1+ and IHC 0 tumours. Such evidence would be essential to justify any revisions to current guideline recommendations12.

Current challenges in clinical practice

One of the significant challenges that emerged after the results of DESTINY-Breast04 trial is distinguishing HER2 score 0 tumours from those with score 1 + , as the existing American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) system categorises both as negative, and the scoring system was developed to identify HER2-positive tumours and to identify tumours requiring ISH reflex testing rather than to identify HER2-Low tumours. This makes us question the results of the ongoing clinical trials. In line with this, the DAISY II trial reported a modest level of activity of T-DXd in non-HER2 expressing tumours38. However, in the same trial, 48% of the tumours that were HER2 IHC 0 had detectable HER2 expression and were classified as 1+ on external pathology review38.

The inter-observer agreement among pathologists when distinguishing between HER2 0 and 1+ is relatively poor39,40,41. Also, spatial and temporal heterogeneity in HER2 expression42 creates challenges in consistently identifying tumours that completely lack membrane staining, increasing the likelihood of false negative results. Furthermore, the sensitivity of current detection kits varies, especially at these very low levels of expression, and significant variation is expected to exist between laboratories using different detection systems. While concordance for HER2-positive and HER2 IHC 0 cases is generally high between central and peripheral laboratories, agreement drops significantly when distinguishing HER2-Low tumours from true negatives. This is mainly due to the subtle and subjective nature of faint or incomplete membrane staining, as well as technical and interpretive variability between laboratories. Central laboratories, which typically follow more rigorous quality assurance protocols and have greater experience, tend to provide more consistent and reproducible HER2-Low scoring compared to local or peripheral centres13,43,44.

HER2 status is also dynamic in patients with BC, not only in primary versus metastatic sites, but also in repeat biopsies following neoadjuvant therapy45,46. These findings will inform our approach to HER2 testing, underscoring the importance of repeat tumour biomarker testing in patients to identify patients who may benefit from ADC treatment.

New testing assay for HER2-Low or refining of the current definition?

The established IHC testing methods (e.g. VENTANA HER2/neu (4B5) assay) are currently used to identify patients with HER2-Low disease in accordance with guideline recommendations6,15 in many laboratories and are used in the approved and ongoing clinical trials (Tables 1 and 2). The emergence of the HER2-Low and HER2 Ultralow categories highlights the importance of not only adherence to guidelines, but also refining the guideline to improve reproducibility of scoring at the lower end of the spectrum of HER2 expression and the need for further training to ensure accurate recognition of these HER2 BC groups15. The United Kingdom updated HER2 guidelines introduced the term HER2-Low and attempted to refine its definition to assist pathologists in identifying these tumours in the clinical setting13

While new quantitative assays, such as the HERmark BC assay47,48, immunofluorescence-based automated quantitative analysis40,49, quantitative IHC50, and assessment of HER2 mRNA expression levels51 are being evaluated, any new assay or kit designed for the detection of HER2-Low tumours must undergo rigorous validation through clinical trials before being integrated into clinical practice. Moreover, it is essential that these assays demonstrate superiority over existing methods to be deemed clinically relevant. In our view, the most immediate and impactful progress can be achieved by prioritising the standardisation of existing HER2 testing assays. This involves harmonising laboratory protocols to reduce inter-laboratory variability and enhance diagnostic accuracy. Strict adherence to established guidelines, particularly those addressing pre-analytical and analytical variables such as tissue fixation, processing, staining techniques, and scoring criteria, is critical for ensuring consistent and reliable HER2 assessment6,20,39,44,52,53, Equally important, is the need to improve concordance among pathologists in the interpretation and categorisation of HER2 status, especially as the distinction between HER2-Low, Ultralow, and null becomes increasingly clinically relevant. Targeted training programmes and continuing education are essential to enhance diagnostic precision, support consistent application of scoring systems, and minimise subjectivity in borderline cases43,54. With the revolution of digital pathology and artificial intelligence (AI), studies have explored the use of AI and digital image analysis to improve concordance among pathologists in scoring HER2-Low BCs. AI algorithms and deep learning models have demonstrated high accuracy in distinguishing between HER2 IHC scores, particularly in the critical differentiation of 0, 1 + , and 2+ categories55. This could provide quantitative and reproducible assessments, reducing subjectivity and inter-observer variability, especially in heterogeneous or borderline cases9,56. While these technologies are not yet universally adopted, they represent promising tools for standardising HER2-Low assessment and supporting more consistent clinical decision-making.

The correlation between target antigen expression and ADC efficacy

With the increasingly promising and unexpected efficacy of ADCs in tumours expressing very low levels of the target protein, it is worth briefly exploring their mechanism of action in an effort to understand their therapeutic role better.

ADCs consist of a humanised monoclonal antibody (mAb) linked to a cytotoxic agent, known as the payload, via a molecular linker. Typically, the antibody component recognises and binds to its target antigen on the cell surface, triggering internalisation of the entire ADC complex via endocytosis. This process delivers the payload directly inside cancer cells, reducing systemic exposure to the cytotoxic agent. It is also proposed that bystander killing of the tumour cells may occur if the payload is released into the extracellular space, where it can be taken up by neighbouring HER2-negative tumour cells, leading to their death5,57 (Fig. 3).

Selecting a suitable target antigen is crucial for modulating the specificity and effectiveness of an ADC. Ideally, the target should be exclusively or predominantly expressed at high levels on tumour cells and minimally on normal cells. HER2 and trophoblast cell surface antigen 2 (TROP2) are examples of such targets currently being utilised in ADC development for the treatment of BC58,59. In general, the efficacy of ADCs appears to be closely linked to the level of target antigen expression on tumour cells. For instance, a study using HER2-targeted liposomal doxorubicin demonstrated that nuclear delivery of doxorubicin increased progressively with higher HER2 expression levels, with a threshold effect observed at approximately 200,000 HER2 receptors per cell60. This threshold supports previous findings that human cardiomyocytes, which express normal levels of HER2 below this threshold, show little to no uptake of the drug. HER2 receptor density on BC cells ranges from 100,000 to 500,000 molecules per cell in HER2 IHC score 1+ and 2+ tumours, compared to over two million in HER2 IHC score 3+ cells61.

Disitamab vedotin (RC48-ADC) is another ADC composed of a novel anti-HER2 humanised antibody, hertuzumab, conjugated to a microtubule inhibitor monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) payload through a cleavable linker. This compound showed effective therapeutic activity in a cohort of 48 patients with HER2-Low mBC, reporting an overall response rate (ORR) of 40% and a median PFS of 5.7 months. However, the response was higher in the HER2 IHC score 2 + /ISH-negative subgroup compared with that in patients with HER2 IHC 1+ tumours62. Furthermore, results from the phase II DAISY trial, that reported a longer PFS in the HER2 overexpressing cohort and a shorter PFS in the HER2 non-expressing cohort (adjusted HR: 1.96, 95% CI 1.21–3.15, P = 0.006) compared to the HER2-Low cohort, in patients receiving T-DXd therapy for mBC38, supports a positive correlation between HER2 antigen levels and the efficacy of HER2-targeting ADC agents.

In the pre-clinical setting, a study which assessed the in vitro potency of anti-HER2 ADC in a panel of cancer cell lines with various degrees of HER2 protein expression also demonstrated that the extent of internalisation was largely influenced by the cell surface HER2 level on the cell surface, which reduced as the HER2 receptor density decreased63.

Bystander killing effect in non-target expressing tumours

The degree to which an ADC mediates bystander killing depends on various factors, including the extent of ADC internalisation after binding to the target antigen, the presence of a non-cleavable or cleavable linker, and the hydrophobicity of the attached cytotoxic payload. Non-cleavable linker ADCs, e.g. T-DM1, are primarily effective against the target antigen-expressing cell after internalisation and are most effective in the treatment of cancers that have high and homogenous expression of the target antigen64,65,66. T-DXd incorporates a cleavable linker, which can be cleaved at a defined pH range or by specific proteases to release the cytotoxic agent. This may result in direct target cell death but may also lead to bystander killing depending on the physicochemical properties of the cytotoxic agent64,67,68. Consequently, these ADCs are useful for treating tumours with heterogeneous antigen expression64,69,70.

The translational analysis performed in the DAISY trial demonstrated that the therapeutic impact of cytotoxic agents on HER2-expressing tumour cells may be diminished by the presence of surrounding target-negative tumour cells71 (Fig. 4). DAISYII trial also explored T-DXd distribution during treatment through IHC staining using an Ac anti-DXd H score, and demonstrated that tumour cells with a high level of HER2 expression presented strong T-DXd levels or staining.

However, two of three patients with BC classified as HER2 IHC 0 who had no or low levels of T-DXd had a confirmed partial response38. These data, together with the results of T-DXd in HER2-Ultralow tumours as proven in the DESTINY-Breast-06 trial37,38, suggests that the effect of T-DXd may be partly mediated by HER2-independent mechanisms and question the need to identify very low levels of HER2 expression as there is no evidence so far to confirm the lack of a similar effect in HER2 null BC.

Mechanisms of resistance to ADC therapy

Understanding the mechanisms behind resistance to ADCs remains a significant challenge. A multicentre study found that cross-resistance may depend on both the antibody target and the cytotoxic payload used in subsequent treatments. Tumour sequencing identified mutations in topoisomerase-related pathways that may contribute to resistance, highlighting the importance of personalised genomic profiling and further research to optimise ADC sequencing for improved patient outcomes72,73,74.

A common mechanism of resistance is reduced target antigen expression, which hinders effective antigen–antibody binding75. In triple-negative BC (TNBC), clinical resistance to IMMU-132 was observed following the loss of TROP2 expression76,77. Similar findings have been reported in other malignancies: CD30 downregulation led to brentuximab vedotin resistance in Hodgkin lymphoma43,78, and reduced CD33 expression was associated with poorer outcomes in acute myeloid leukaemia treated with gemtuzumab ozogamicin79. This phenomenon has also been observed with HER2-targeting ADCs such as T-DM1. A phase II trial showed that higher HER2 expression correlated with greater T-DM1 efficacy80, while separate studies found reduced HER2 levels and binding in resistant cell lines81,82.

The tumour microenvironment (TME) also contributes to resistance. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) can create physical barriers to ADC penetration, and tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) may clear ADCs via Fcγ receptor-mediated uptake83,84,85. Additional mechanisms include altered intracellular trafficking, impaired internalisation or recycling of the ADC, and tumour heterogeneity, which allows subclones with low or absent antigen expression to evade targeting85,86.

Resistance related to the payload itself involves drug efflux pumps such as MDR1, mutations in payload targets (e.g., tubulin or topoisomerase), and dysfunctional lysosomal processing, which limits effective payload release75,84,86.

HER2-positive BC and response to therapy: protein overexpression or gene amplification?

In HER2 overexpressing BC, the growth of tumour cells and hence the response to HER2 pathway targeting therapy is mainly driven by the oncogenic activity of the HER2 signalling pathways. To date, patients with BC featuring either HER2 protein overexpression (IHC 3 + ) or equivocal protein expression (IHC 2 + ) with evidence of HER2 gene amplification on ISH studies are considered candidates for anti-HER2 targeted therapies6. However, the response rate in patients with HER2-positive BC is not uniform. The magnitude of response, measured by the rate of pathologic complete response (pCR), of HER2 IHC score 3+ tumours ranges from 55 to 70% compared to 17–20% in HER2 2 + /ISH-positive14,87,88,89,90,91, raising the possibility that HER2 protein overexpression rather than HER2 gene amplification is the key driver of response (Table 3). Despite the previous data that showed a strong correlation between HER2 gene amplification and response to treatment, most BCs with high-level amplifications also showed IHC 3+ expression, which may have biased the results. Detailed analysis of IHC 2 + /ISH positive BC response to anti-HER2 therapy in the adjuvant setting was based on subgroup analysis with demonstration of some response in patients with HER2 amplified compared to those with non-amplified BC based on the definition of gene amplification rather than selecting a cutoffs that defined a significant difference in response.

The fact that most anti-HER2 targeted therapies exert their action on the HER2 protein and the excellent correlation between HER2 IHC 3+ and high HER2 gene amplification levels17,92 may explain why most BCs with high amplification levels respond well to anti-HER2 therapy. Variation in response to treatment is more often seen in HER2 IHC 2+ tumours which frequently show borderline gene amplification88,93,94. These observations together with the finding that 4% of BCs with HER2 IHC scores 0 and 1+ show evidence of gene amplification93, argue against using ISH alone as a predictor of response to anti-HER2 therapy. The HERA and N9831 trials concluded that HER2/CEP17 ratio and HER2 gene copy number were not associated with patient outcome95,96,97, consistent with the results of several previous studies, which demonstrated that HER2 protein overexpression is the strong predictor of response to anti-HER2 therapy88,96,98,99,100,101,102,103,104. Other studies have also indicated that the rate of pCR in the subset of patients with evidence of HER2 gene amplification, in the absence of HER2 protein overexpression, was significantly lower (17% vs 66%)88,100.

Some studies have suggested a correlation between HER2 gene amplification levels and the therapeutic response to anti-HER2 therapy105,106,107,108. However, research by Gianni et al.109, Xu et al.110, Guiu et al108. and Perez et al.96,108,109,110 found no link between HER2 gene copy number and survival. While some authors, including Zabaglo et al.111, argued that HER2 protein expression levels do not influence clinical management with anti-HER2 therapy, their study assessed a spectrum of HER2 staining rather than applying a dichotomised classification (IHC 3+ versus 2 + ). Other reports have suggested that the optimum strategy for selecting patients for anti-HER2 therapy is to measure HER2 gene amplification by ISH testing112,113. This was based on studies that included tumours with IHC scores of 3+ and 2+ and the ISH negative group included only IHC 2+ tumours, resulting in an over-emphasis of the value of ISH testing112,113. A recent study recommended performing FISH testing in HER2 IHC-negative cases (scores of 0 and 1 + ), as some of these tumours were found to be FISH positive albeit near the HER2/CEP17 ratio and HER2 gene copy number cut-offs114. We argue that their conclusion is debatable, as it was not supported by evidence of therapeutic response. Additionally, in light of the promising outcomes of ADC in HER2-Low cases, cost-effective analysis of conducting FISH testing for every HER2-negative patient to qualify for anti-HER2 therapy, as opposed to directly administering ADC is a consideration.

The phenomenon of oncogenic addiction of cancer cells to HER2 for the maintenance of their malignant phenotype is one of the main determining factors of response to anti-HER2 therapies115,116. High HER2 protein expression, HER2 mRNA level, high and homogenous pattern of HER2 gene amplification, and HER2 downstream signalling are necessary for true HER2 addiction, and identification of HER2-addicted tumours is essential to reap the complete therapeutic benefit of HER2-targeted drugs117,118. Furthermore, the HER2-enriched (HER2-E) molecular subtype identifies patients with increased likelihood of achieving a pCR following neoadjuvant anti-HER2-based therapy119,120,121,122,123. Furthermore, the PAMELA phase 2 trial concluded that the HER2-E subtype is the key predictor of pCR following trastuzumab and lapatinib without chemotherapy in early-stage HER2-positive BC124.

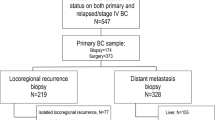

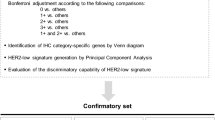

In an effort to further investigate the differential response of both HER2-positive BC classes to HER2 targeted therapy, our group investigated the pCR rates, patient outcome and the differential expression of HER2 oncogenic signalling genes in a large series of patients (n = 7390) with BC, classified as HER2-positive due to HER2 protein overexpression or borderline expression but with HER2 gene amplification14. The results of our study suggest that BC characterised by HER2 protein overexpression (IHC 3 + ) is likely propelled by the HER2 oncogenic signalling pathway, alongside increased expression of several receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) e.g. FGFR4, EGFR, and HER2 itself. Additionally, these tumours exhibit elevated expression of genes within the HER2 amplified region on Chr17q12-q21, including GRB7, which may account for their heightened sensitivity to anti-HER2 therapy. Conversely, patients with borderline HER2 protein expression show limited response to anti-HER2 therapy, irrespective of HER2 gene amplification levels, particularly those with oestrogen receptor-positive (ER-positive) tumours. Such low response rates of BC with borderline HER2 protein expression, which appear not to differ from the response rates of HER2-negative BC to chemotherapy (15–25%)125, may support the need for further comparative studies between conventional anti-HER2 therapy and HER2 directed ADCs in patients with these tumours.

Role of ER expression in theresponse of HER2-positive BC classes to therapy

The interaction between HER2 and ER signalling pathways plays an important role in driving BC proliferation, involving intricate molecular processes126. It has been reported that HER2 overexpression may reduce the effectiveness of anti-endocrine therapy (tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (AI)) and ovarian suppression in pre-menopausal women127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134. Regarding resistance to anti-HER2 therapy, in the pre-clinical setting, it has been shown that the expression of ER and its downstream targets is increased in cells with acquired resistance to anti-HER2 therapy130,135. Reactivation of ER expression and signalling, including a switch from ER-negative to ER-positive status, has been observed in HER2-positive tumours following neoadjuvant lapatinib treatment130.

The interplay between ER and HER2 levels in predicting response to adjuvant trastuzumab within HER2-positive classes was considered in the secondary analyses of HERA and NeoALTTO pivotal trials. Notably, patients with ER-positive and HER2-positive status, but with low HER2 gene copy number, derived diminished benefit from adjuvant trastuzumab despite receiving concomitant endocrine therapy136. Additionally, investigations into gene expression levels of ESR1 and HER2 revealed that higher HER2 and lower ESR1 levels correlated with increased pCR rates for HER2-targeted therapy137

Despite extensive research, the response variability to anti-HER2 therapy among HER2-positive BC classes remains complex across distinct ER expression groups, necessitating further investigation. In an earlier study, we investigated the role of ER positivity among HER2-positive categories of BC and its role in response to anti-HER2 therapy. We concluded that ER positivity was a significant predictor of poor response to anti-HER2 therapy in the overall cohort and tumours with borderline protein expression but not in patients with HER2 IHC 3 + BC, observed in both neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment settings14. These findings resonate with those of Harbeck, Gluz138 who reported comparable pCR rates in HR-positive and HR-negative patients with HER2 protein overexpression. This is likely because tumours with HER2 protein overexpression are primarily HER2-E, dominantly driven by the HER2 signalling pathway regardless of ER level, with blockade of HER2 signalling leading to apoptosis and tumour cell death. In contrast, HER2-positive tumours with borderline HER2 protein expression are more frequently ER-positive, enriched with ER signalling pathways and associated genes, e.g. ESR1 and BCL2, dependent on the alternative ER signalling to survive, and less likely to include tumours with the HER2-E molecular subtype14.

Optimal ADC sequence and patient selection

Considering the expansion of the therapeutic armamentarium for BC patients, with several ADCs approaching the clinic, further research is needed to master treatment sequencing in mBC. In post hoc analyses of the phase III TROPiCS-02 and the ASCENT trials139,140, the anti-TROP2 ADC, Sacituzumab govitecan (SG) demonstrated efficacy in HER2-Low mBC, both HR-positive and HR-negative tumours. SG has been approved after disease progression on ET and ⩾2 additional systemic therapies for mBC139,140. Another TROP2-directed ADC, Dato-DXd, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, has shown efficacy following prior ET and 1–2 lines of chemotherapy in the TROPION-Breast01 trial141. In this study, median mPFS increased from 4.9 months with the treatment of the physician’s choice to 6.9 months with Dato-DXd (HR, 0.63 [95% CI, 0.52 to 0.76]141 An overview of the clinical trials on ADC in HER2-Low BC is summarised in Table 2.

HR-positive/HER2-Low

For patients with HR-positive/HER2-Low mBC, the standard first-line therapy remains a combination of ET and CDK4/6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) (abemaciclib, palbociclib, or ribociclib), provided there is no visceral crisis142,143 (Fig. 5).

BC breast cancer, ChT chemotherapy, ER oestrogen receptor, ET Endocrine therapy, ISH in situ hybridisation, HER2 human epidermal growth factor 2, HR hormone receptor, IHC immunohistochemistry, mBC metastatic breast cancer, T-DM1 trastuzumab emtansine, T-DXd trastuzumab deruxtecan, THP taxanes, trastuzumab, pertuzumab. Created with biorender.com.

For subsequent lines of therapy, additional ETs, possibly combined with mTOR or PI3K inhibitors, can be considered144. After ET regimes are exhausted, single-agent chemotherapy is recommended142,143. However, with the accumulating evidence of favourable results with T-DXd over chemotherapy in patients who received ⩾2 ET in the DESTINY-Breast06 trial37 and following prior ET and up to two lines of chemotherapy in the DESTINY-Breast04 trial15, we believe that it may be superior to standard chemotherapy, potentially positioning T-DXd as the first non-ET for this population. Considering SG, although it showed significant improvements in PFS (5.5 vs. 4.0 months; HR: 0.66) and overall survival (14.4 vs. 11.2 months; HR: 0.79) compared to chemotherapy, patients in the TROPiCS-02 trial received considerably more prior treatment (ET, CDK4/6 inhibitors, and 2–4 lines of chemotherapy) than those in the DESTINY-Breast04 trial, rendering it more suitable as a later treatment option, following T-DXd.

HR-negative/HER2-Low

The DESTINY-Breast04 trial positions T-DXd as a second-line treatment after chemotherapy, or as a frontline option for patients experiencing early recurrence after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Although the trial was not specifically powered to evaluate TNBC, T-DXd showed a clear benefit in the small TNBC subgroup, suggesting its use in patients with TNBC with low HER2 expression15. SG is also approved for patients with TNBC who have received at least two prior systemic therapies based on the ASCENT trial139, which demonstrated a significant PFS and overall survival benefit over chemotherapy.

For patients eligible to receive both TROP-2- and HER2-targeted ADCs, it is still uncertain which agent should be used first and whether administering them in sequence provides added clinical benefit. In a real-world cohort of heavily pretreated patients with HER2-Low disease, SG retains its clinical activity. T-DXd continues to demonstrate promising clinical activity after SG, supporting the use of sequential ADC in this population43,145. In a multicentre analysis72,73,74, researchers investigated the use of sequential ADCs in patients with HR + /HER2-Low and HR-/HER2-Low mBC. Across all subgroups, the overall response rate (ORR) and time to next treatment (TTNT) were higher following the first ADC than for the second, regardless of HR status or the order of ADC administration. Additionally, in this heavily pre-treated population, PFS was shorter with the second ADC, highlighting a potential limitation of sequential ADC use.

According to DESTINY-Breast 04 trial, patients were enroled in the T-DXd arm after receiving one to two lines of chemotherapy, while in the SG based trials, patients received two to four lines of chemotherapy prior to enrolment in the SG arm. Regarding HR-status, both T-DXd and SG showed promising results in HR-positive and HR-negative BC patients, although the DESTINY-Breast 04 included only 63 patients with HR-negative, HER2-Low disease.

Until there is a randomised-controlled clinical trial that elucidates the comparative efficacy of these agents, current evidence supports the use of T-DXd over SG in the management of HER2-Low BC patients who meet the eligibility criteria in view of the higher level of evidence in the HER2-Low population (Phase III versus post hoc analyses for SG), in addition to the lower number of prior lines of chemotherapy received by patients in DESTINY-Breast04.

Identifying patients most likely to benefit from these therapies may require more detailed tumour biomarker assessment, along with consideration of individual risk profiles for treatment-related toxicity. As part of the selection process, it is important to evaluate tolerance to potential side effects. Common adverse events include neutropenia, anaemia, fatigue, nausea, and diarrhoea. More serious, though less frequent, toxicities such as interstitial lung disease (particularly with T-DXd), cardiac dysfunction, and ocular complications should also be taken into account42,146,147,148,149.

Potential value of ADCs in HER2 IHC 2+ and ISH-positive BC

The Phase III KATHERINE trial, comparing adjuvant T-DM1 versus trastuzumab for residual invasive disease following neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive BC, reported that treatment benefit was less pronounced in patients with HER2 IHC 2 + /ISH-positive compared to that observed in patients with IHC 3+ tumours in the trastuzumab arm. However, in the T-DM1 arm, the 3-year invasive disease-free survival (IDFS) rate did not differ significantly between the two HER2-positive groups (89% in IHC 3+ and 85% in IHC 2 + /ISH-positive). Further analysis revealed that patients with heterogeneous HER2 expression, predominantly observed in HER2 IHC 2 + /ISH-positive tumours, had comparable IDFS rates to those with homogeneous expression, mainly observed in HER2 IHC 3 + , in the T-DM1 arm (89% and 88%, respectively). In contrast, less benefit was observed in tumours with heterogeneous HER2 expression in the Trastuzumab arm150.

In vitro studies that compared trastuzumab and T-DM1 in HER2-positive cell lines revealed that T-DM1 was more efficacious in trastuzumab-sensitive and in trastuzumab-insensitive HER2-positive cell lines. Using a trastuzumab-resistant xenograft tumour model, it was also demonstrated that T-DM1 can induce both apoptosis and mitosis in vivo151,152. Additionally, comparative trials are required to explore the potential value of T-DXd therapy versus trastuzumab in tumours with borderline HER2 expression, particularly in view of the effectiveness of this form of treatment in both IHC HER2-positive and HER2-Low BC (Fig. 5).

Novel targets in the management of HER2-positive/ER-positive BC

Approximately 50% of HER2-positive tumours will co-express hormone receptors, which results in substantial clinical heterogeneity in the behaviour of HER2-positive BC153. Treating HER2-positive/ER-positive BC is complex. While identification of the biological driver (i.e., whether ER or HER2 signalling is dominant) may assist decision making regarding the choice of therapy, pathway interaction and crosstalk may modify and alter the disease course during treatment. Combining hormone therapy with anti-HER2 agents has proven beneficial in some HER2-positive patients153,154, particularly those who have tumours with high ER expression. Some ER-positive/HER2-positive tumours pursue a clinical course similar to luminal A tumours (i.e., ER-driven cancer), others behave as HER2-E tumours (HER2-driven cancer), and some show overlapping clinical features that require combined targeted blockade of both ER and HER2 pathways. Patients with luminal HER2-positive disease may benefit from the addition of ET to their neoadjuvant treatment to improve pCR rates (Table 4).

CDK4/6 inhibitors

The cyclin D1-CDK4/6 pathway has been shown to mediate treatment resistance in HER2-positive BC155,156,157,158. Several clinical trials are evaluating the utility of CDK4/6 inhibitors in addition to ET in HER2-positive BC and the potential scope for a non-chemotherapy approach (PATINA NCT02947685; PATRICIA NCT02448420; MonarcHER NCT02675231; PALTAN NCT02907918). The phase II MonarcHER trial was the first randomised study utising a CDK4/6 inhibitor to report results in combination with ET and anti-HER2 treatment159. This study randomly assigned 237 patients with HER2-positive and HR-positive advanced BC who had been previously treated with at least two prior HER2 targeted therapies to abemaciclib, trastuzumab and Fulvestrant (arm A), abemaciclib with trastuzumab (arm b) or chemotherapy plus trastuzumab (arm c). The triple combination was superior to chemotherapy and trastuzumab (8.3 months v 5.7; HRa, 0.67; P = 0.051). No difference was observed between abemaciclib and trastuzumab versus chemotherapy and trastuzumab (HRa, 0.94; P = 0.77). Further studies are warranted to delineate the role of CDK4/6 inhibitors in HER2-positive and HR-positive BC. In this direction, the PATRICIA phase II trial enroled 71 patients with HER2-positive disease who had received 2–4 prior lines of anti-HER2–based regimens to receive palbociclib plus trastuzumab with or without letrozole (if HR-positive)160. The study concluded that the benefit of palbociclib and trastuzumab was mostly restricted to patients with HR-positive disease. More importantly, the luminal subtype, defined by PAM50, was independently associated with improved PFS compared with the non-luminal subtypes (10.6 months vs 4.2 months; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.40; P = 0.003)160. Based on these results, the PATRICIA-II phase II trial (NCT02448420) is currently comparing palbociclib, trastuzumab, and endocrine therapy versus chemotherapy and trastuzumab in patients with PAM50 luminal disease. PATINA phase III trial showed that the addition of the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib was of benefit as first-line maintenance therapy in HR-positive, HER2-positive metastatic BC in combination with anti-HER2 and endocrine therapy161.

Alpha-specific PI3K inhibitors

PIK3CA somatic mutations in HER2-positive disease are frequent and represent approximately 30% of all HER2-positive and HR-positive tumours162. Thus, based on the clinical efficacy of alpelisib, an alpha-specific inhibitor, in HER2-negative and HR-positive disease, together with pre-clinical data suggesting a role for PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway alterations in anti-HER2 treatment resistance, there is a strong rationale for evaluating the combination of alpelisib with anti-HER2 treatment in patients with HER2-positive and HR-positive PIK3CA-mutated BC. A phase I clinical trial of alpelisib and T-DM1 in HER2-positive mBC after taxane-trastuzumab showed that the combination was tolerable and demonstrated activity with an ORR of 43%. Furthermore, activity was also observed in T-DM1–resistant disease (n 510) with an ORR of 30%163. These data support the view that PI3K inhibition targets a resistance pathway to anti-HER2 therapy, providing rationale for continued evaluation the role of PI3K inhibition in refractory HER2-positive mBC. Several trials combining anti-HER2 therapy with PI3K pathway inhibition are ongoing, such as the phase I trial IPATHER (NCT04253561) with ipatasertib, the phase I trial B-PRECISE-01 (NCT03767335) with the PI3K inhibitor MEN1611 and the phase III trial EPIK-B2 (NCT04208178) with alpelisib as maintenance therapy.

Conclusion

HER2-Low BC is emerging as a promising targetable clinical entity for ADC therapy with efficacy linked to the level of HER2 expression. The clinical benefit of T-DXd in HER2 IHC 0 tumours is questionable, and whether this BC subset represents a target for T-DXd remains to be defined particularly with initial data showing some response in the HER2-Ultralow category. Standardisation of the current HER2 detection assays, with refinement and adherence to the guideline recommendations regarding pre-analytical and analytical variables for HER2 testing, including scoring criteria, and ongoing pathologist and medical scientist training are important to enhance reproducibility and to improve concordance in categorisation, particularly at the lower end of the HER2 expression spectrum. At the present time, HER2-Low relapsed/mBC is sufficient to warrant consideration of T-DXd treatment for affected patients with an emphasis on optimising therapy sequencing. Further studies comparing conventional anti-HER2 therapy and HER2-directed ADCs in HER2 IHC 2 + /ISH-positive tumours are also warranted to inform clinical practice and improve patient outcome.

References

Harbeck, N. & Gnant, M. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet 389, 1134–1150 (2017).

Appert-Collin, A. et al. Role of ErbB receptors in cancer cell migration and invasion. Front. Pharmacol. 6, 283 (2015). p.

Ali, R. & Wendt, M. K. The paradoxical functions of EGFR during breast cancer progression. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2, 1–7 (2017). p.

Kallioniemi, O. P. et al. ERBB2 amplification in breast cancer analyzed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 5321–5325 (1992). p.

Marchiò, C. et al. Evolving concepts in HER2 evaluation in breast cancer: heterogeneity, HER2-low carcinomas and beyond. Semin. Cancer Biol. 72, 123–135 (2021).

Wolff, A. C. et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline focused update. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 142, 1364–1382 (2018).

Annaratone, L., Sarotto, I. & Marchiò, C. HER2 in breast cancer, 1–11 (Encyclopedia of Pathology, Springer, 2019).

Bradley, R. et al. Trastuzumab for early-stage, HER2-positive breast cancer: a meta-analysis of 13 864 women in seven randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 22, 1139–1150 (2021).

Sajjadi, E. et al. Pathological identification of HER2-low breast cancer: tips, tricks, and troubleshooting for the optimal test. Front. Mol. Biosci. 10, 1176309 (2023).

Rinnerthaler, G., Gampenrieder, S. P. & Greil, R. HER2 directed antibody-drug-conjugates beyond T-DM1 in breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1115 (2019).

Tarantino, P. et al. HER2-low breast cancer: pathological and clinical landscape. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 1951–1962 (2020).

Wolff, A. C. et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: ASCO-College of American Pathologists Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 3867–3872 (2023).

Rakha, E. A. et al. UK recommendations for HER2 assessment in breast cancer: an update. J. Clin. Pathol. 76, 217–227 (2023).

Atallah, N. M. et al. Differential response of HER2-positive breast cancer to anti-HER2 therapy based on HER2 protein expression level. Br. J. Cancer 129, 1692–1705 (2023).

Modi, S. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 9–20 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Accuracy of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 status between core needle and open excision biopsy in breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 134, 957–967 (2012).

Middleton, L. P. et al. Implementation of American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists HER2 Guideline Recommendations in a tertiary care facility increases HER2 immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization concordance and decreases the number of inconclusive cases. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 133, 775–780 (2009).

Perez, E. A. et al. HER2 testing by local, central, and reference laboratories in specimens from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 intergroup adjuvant trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 3032–3038 (2006).

Wolff, A. et al. College of American Pathologists Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 3997–4013 (2013).

Wolff, A. C. et al. College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J. Clin. oncol. 25, 118–145 (2007).

Venetis, K. et al. HER2 low, ultra-low, and novel complementary biomarkers: expanding the spectrum of HER2 positivity in breast cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 834651 (2022).

Miglietta, F. et al. Evolution of HER2-low expression from primary to recurrent breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 7, 137 (2021).

de Moura Leite, L. et al. HER2-low status and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in HER2 negative early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 190, 155–163 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. HER2-low breast cancers: incidence, HER2 staining patterns, clinicopathologic features, MammaPrint and BluePrint genomic profiles. Mod. Pathol. 35, 1075–1082 (2022).

van den Ende, N. S. et al. HER2-low breast cancer shows a lower immune response compared to HER2-negative cases. Sci. Rep. 12, 12974 (2022).

Denkert, C. et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of HER2-low-positive breast cancer: pooled analysis of individual patient data from four prospective, neoadjuvant clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 22, 1151–1161 (2021).

Molinelli, C. et al. Prognostic value of HER2-low status in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ESMO Open 8, 101592 (2023).

Buckley, N. E. et al. Quantification of HER2 heterogeneity in breast cancer-implications for identification of sub-dominant clones for personalised treatment. Sci. Rep. 6, 23383 (2016).

Agostinetto, E. et al. HER2-low breast cancer: molecular characteristics and prognosis. Cancers 13, 2824 (2021).

Horisawa, N. et al. The frequency of low HER2 expression in breast cancer and a comparison of prognosis between patients with HER2-low and HER2-negative breast cancer by HR status. Breast Cancer 29, 234−241 (2022).

Jacot, W. et al. Prognostic value of HER2-low expression in non-metastatic triple-negative breast cancer and correlation with other biomarkers. Cancers 13, 6059 (2021).

Schettini, F. et al. Clinical, pathological, and PAM50 gene expression features of HER2-low breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 7, 1 (2021).

Lai, H.-Z. et al. Targeted approaches to HER2-low breast cancer: current practice and future directions. Cancers 14, 3774 (2022).

Molinelli, C. et al. HER2-low breast cancer: where are we?. Breast Care 17, 533–545 (2022).

Nicolò, E., Tarantino, P. & Curigliano, G. Biology and treatment of HER2-low breast cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. 37, 117–132 (2023).

Atallah, N. M. et al. Characterisation of luminal and triple-negative breast cancer with HER2 Low protein expression. Eur. J. Cancer 195, 113371 (2023). p.

Bardia, A. et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan after endocrine therapy in metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 391, 2110−2122 (2024).

Mosele, F. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in metastatic breast cancer with variable HER2 expression: the phase 2 DAISY trial. Nat. Med. 29, 2110–2120 (2023).

Fernandez, A. I. et al. Examination of low ERBB2 protein expression in breast cancer tissue. JAMA Oncol. 8, 607–610 (2022).

Moutafi, M. et al. Quantitative measurement of HER2 expression to subclassify ERBB2 unamplified breast cancer. Lab. Investig. 102, 1101–1108 (2022).

Pauzi, S. H. M. et al. HER2 testing by immunohistochemistry in breast cancer: a multicenter proficiency ring study. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 64, 677–682 (2021).

Nicolò, E. et al. The HER2-low revolution in breast oncology: steps forward and emerging challenges. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 15, 17588359231152842 (2023).

Atallah, N. M. et al. Refining the definition of HER2-low class in invasive breast cancer. Histopathology 81, 770–785 (2022).

Rakha, E. A. et al. Updated UK Recommendations for HER2 assessment in breast cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 68, 93–99 (2015).

Bar, Y. et al. Dynamic HER2-low status among patients with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC): the impact of repeat biopsies. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 1005–1005 (2023).

Denkert, C. et al. editors. Outcome analysis of HER2-zero or HER2-low hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancer patients-characterization of the molecular phenotype in combination with molecular subtyping. Proceedings of the 2022 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (pp. 6–10) (2022).

Larson, J. S. et al. Analytical validation of a highly quantitative, sensitive, accurate, and reproducible assay (HERmark®) for the measurement of HER2 total protein and HER2 homodimers in FFPE breast cancer tumor specimens. Pathol. Res. Int. 2010, 814176 (2010)

Yardley, D. A. et al. Quantitative measurement of HER2 expression in breast cancers: comparison with ‘real-world’routine HER2 testing in a multicenter Collaborative Biomarker Study and correlation with overall survival. Breast Cancer Res. 17, 1–13 (2015).

Harigopal, M. et al. Multiplexed assessment of the Southwest oncology group-directed intergroup breast cancer trial S9313 by AQUA shows that both high and low levels of HER2 are associated with poor outcome. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 1639–1647 (2010).

Jensen, K. et al. A novel quantitative immunohistochemistry method for precise protein measurements directly in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens: analytical performance measuring HER2. Mod. Pathol. 30, 180–193 (2017).

Griguolo, G. et al. ERBB2 mRNA expression and response to ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancers 12, 1902 (2020).

Tarantino, P., Curigliano, G. & Tolaney, S. M. Navigating the HER2-low paradigm in breast oncology: new standards, future horizons. Cancer Discov. 12, 2026–2030 (2022). p.

Wolff, A. C. et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 3997–4013 (2013).

Zaakouk, M. et al. Concordance of HER2-low scoring in breast carcinoma among expert pathologists in the United Kingdom and the republic of Ireland –on behalf of the UK national coordinating committee for breast pathology. Breast 70, 82–91 (2023).

Albuquerque, D. A. N., Vianna M. T., Vasiliu, A. & Neves Filho, E. C. 6P Diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence in classifying HER2 statusin breast cancer immunohistochemistry slides: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ESMO Open 9 (2024).

Sode, M. et al. Digital image analysis and assisted reading of the HER2 score display reduced concordance: pitfalls in the categorisation of HER2-low breast cancer. Histopathology 82, 912–924 (2023).

De Cecco, M., Galbraith, D. N. & McDermott, L. L. What makes a good antibody–drug conjugate?. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 21, 841–847 (2021).

Pegram, M. D., Konecny, G. & Slamon, D. J. The molecular and cellular biology of HER2/neu gene amplification/overexpression and the clinical development of herceptin (trastuzumab) therapy for breast cancer. Adv. Breast Cancer Manag. 103, 57–75 (2000).

Shvartsur, A. & Bonavida, B. Trop2 and its overexpression in cancers: regulation and clinical/therapeutic implications. Genes Cancer 6, 84 (2015).

Hendriks, B. S. et al. Impact of tumor HER2/ERBB2 expression level on HER2-targeted liposomal doxorubicin-mediated drug delivery: multiple low-affinity interactions lead to a threshold effect. Mol. Cancer Ther. 12, 1816–1828 (2013).

Onsum, M. D. et al. Single-cell quantitative HER2 measurement identifies heterogeneity and distinct subgroups within traditionally defined HER2-positive patients. Am. J. Pathol. 183, 1446–1460 (2013).

Wang, J. et al. RC48-ADC, a HER2-targeting antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with HER2-positive and HER2-low expressing advanced or metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of two studies. Wolters Kluwer Health. (2021)

Li, J. Y. et al. A biparatopic HER2-targeting antibody-drug conjugate induces tumor regression in primary models refractory to or ineligible for HER2-targeted therapy. Cancer Cell 29, 117–129 (2016).

Kovtun, Y. V. et al. Antibody-drug conjugates designed to eradicate tumors with homogeneous and heterogeneous expression of the target antigen. Cancer Res. 66, 3214–3221 (2006).

Filho, O. M. et al. Impact of HER2 heterogeneity on treatment response of early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer: phase II neoadjuvant clinical trial of T-DM1 combined with pertuzumab. Cancer Discov. 11, 2474–2487 (2021).

Ogitani, Y. et al. Bystander killing effect of DS-8201a, a novel anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 antibody–drug conjugate, in tumors with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterogeneity. Cancer Sci.107, 1039–1046 (2016).

Li, F. et al. Intracellular released payload influences potency and bystander-killing effects of antibody-drug conjugates in preclinical models. Cancer Res. 76, 2710–2719 (2016).

Singh, A. P., Sharma, S. & Shah, D. K. Quantitative characterization of in vitro bystander effect of antibody-drug conjugates. J. pharmacokinetics pharmacodynamics 43, 567–582 (2016).

Golfier, S. et al. Anetumab ravtansine: a novel mesothelin-targeting antibody–drug conjugate cures tumors with heterogeneous target expression favored by bystander effect. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13, 1537–1548 (2014).

Okeley, N. M. et al. Intracellular activation of SGN-35, a potent anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 888–897 (2010). p.

Mosele, M. et al. LBA1 Unraveling the mechanism of action and resistance to trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd): Biomarker analyses from patients from DAISY trial. Ann. Oncol. 33, S123 (2022).

Abelman, R. O. et al. Abstract PS08-03: sequencing antibody-drug conjugate after antibody-drug conjugate in metastatic breast cancer (A3 study): multi-institution experience and biomarker analysis. Cancer Res. 84, PS08-03–PS08-03 (2024).

Huppert, L. A. et al. Multicenter retrospective cohort study of the sequential use of the antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) and sacituzumab govitecan (SG) in patients with HER2-low metastatic breast cancer (MBC): Updated data and subgroup analyses by age, sites of disease, and use of intervening therapies. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 1083–1083 (2024).

Poumeaud, F. et al. Abstract PS08-02: efficacy of Sacituzumab-Govitecan (SG) post Trastuzumab-deruxtecan (T-DXd) and vice versa for HER2low advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC): a French multicentre retrospective study. Cancer Res. 84, PS08-02 (2024).

Chen, Y. F. et al. Resistance to antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: mechanisms and solutions. Cancer Commun. 43, 297–337 (2023).

Jirapongwattana, N., Thongchot, S. & Thuwajit, C. The overexpressed antigens in triple negative breast cancer and the application in immunotherapy. Genom. Genet. 13, 19–32 (2020).

Coates, J. T. et al. Parallel genomic alterations of antigen and payload targets mediate polyclonal acquired clinical resistance to sacituzumab govitecan in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 11, 2436–2445 (2021).

Chen, R. et al. CD30 downregulation, MMAE resistance, and MDR1 upregulation are all associated with resistance to brentuximab vedotin. Mol. Cancer Ther. 14, 1376–1384 (2015).

Fenwarth, L. et al. Biomarkers of gemtuzumab ozogamicin response for acute myeloid leukemia treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 5626 (2020).

Burris, H. A. et al. Phase II study of the antibody drug conjugate trastuzumab-DM1 for the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer after prior HER2-directed therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 398–405 (2011).

Li, G. et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to trastuzumab emtansine in breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 17, 1441–1453 (2018). p.

Loganzo, F. et al. Tumor cells chronically treated with a trastuzumab–maytansinoid antibody–drug conjugate develop varied resistance mechanisms but respond to alternate treatments. Mol. Cancer Ther. 14, 952–963 (2015).

Chang, H. L. et al. Antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: overcoming resistance and boosting immune response. J. Clin. Investig. 133, (2023).

Larose, É et al. Antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer treatment: resistance mechanisms and the role of therapeutic sequencing. Cancer Drug Resist. 8, 11 (2025). p.

Li, S. et al. Resistance to antibody–drug conjugates: A review. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 15, 737–756 (2025).

Saleh, K. et al. Mechanisms of action and resistance to anti-HER2 antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 7, 22 (2024).

Katayama, A. et al. Predictors of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant treatment and changes to post-neoadjuvant HER2 status in HER2-positive invasive breast cancer. Mod. Pathol. 34, 1271–1281 (2021).

Krystel-Whittemore, M. et al. Pathologic complete response rate according to HER2 detection methods in HER2-positive breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant systemic therapy. Breast cancer Res. Treat. 177, 61–66 (2019).

Chen, W. et al. Differences between the efficacy of HER2(2+)/FISH-positive and HER2(3+) in breast cancer during dual-target neoadjuvant therapy. Breast 71, 69–73 (2023).

Jiao, D. et al. Comparison of the response to neoadjuvant therapy between immunohistochemistry HER2 (3+) and HER2 (2+)/ISH+ early-stage breast cancer: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Oncologist 29, e877−e886 (2024).

Winer, L. et al. Immunohistochemical status predicts pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant therapy in HER2-overexpressing breast cancers. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 32, 931−943 (2024).

Sui, W. et al. Comparison of immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assessment for Her-2 status in breast cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 7, 83 (2009).

Dybdal, N. et al. Determination of HER2 gene amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization and concordance with the clinical trials immunohistochemical assay in women with metastatic breast cancer evaluated for treatment with trastuzumab. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 93, 3–11 (2005).

Dodson, A. et al. Breast cancer biomarkers in clinical testing: analysis of a UK national external quality assessment scheme for immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridisation database containing results from 199 300 patients. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 4, 262–273 (2018).

Dowsett, M. et al. Disease-free survival according to degree of HER2 amplification for patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy with or without 1 year of trastuzumab: the HERA Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 2962 (2009).

Perez, E. A. et al. HER2 and chromosome 17 effect on patient outcome in the N9831 adjuvant trastuzumab trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4307 (2010).

Gullo, G. et al. Level of HER2/neu gene amplification as a predictive factor of response to trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Investig. N. Drugs 27, 179–183 (2009).

Chen, H. -l, Chen, Q. & Deng, Y. -c Pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy is associated with HER2 immunohistochemistry score in HER2-positive early breast cancer. Medicine 100, e27632 (2021).

Rakha, E. A. et al. Retrospective observational study of HER2 immunohistochemistry in borderline breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy, with an emphasis on Group 2 (HER2/CEP17 ratio≥ 2.0, HER2 copy number< 4.0 signals/cell) cases. Br. J. Cancer 124, 1836–1842 (2021).

Xu, B. et al. HER2 protein expression level is positively associated with the efficacy of neoadjuvant systemic therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. Pathol.Res. Pract. 234, 153900 (2022).

Yan, H. et al. Association between the HER2 protein expression level and the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 12715 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. HER2 immunohistochemistry staining positivity is strongly predictive of tumor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in HER2 positive breast cancer. Pathol.Res. Pract. 216, 153155 (2020).

Slamon, D. J. et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 783–792 (2001).

Swain, S. M. et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA): end-of-study results from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 519–530 (2020).

Kim, J.-W. et al. HER2/CEP17 ratio and HER2 immunohistochemistry predict clinical outcome after first-line trastuzumab plus taxane chemotherapy in patients with HER2 fluorescence in situ hybridization-positive metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 72, 109–115 (2013).

Li, F. et al. Association of HER-2/CEP17 Ratio and HER-2 copy number with pCR Rate in HER-2-positive breast cancer after dual-target neoadjuvant therapy with Trastuzumab and Pertuzumab. Front. Oncol. 12, 819818 (2022).

Singer, C. F. et al. Pathological complete response to neoadjuvant trastuzumab is dependent on HER2/CEP17 ratio in HER2-amplified early breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 3676–3683 (2017).

Guiu, S. et al. Pathological complete response and survival according to the level of HER-2 amplification after trastuzumab-based neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 103, 1335–1342 (2010).

Gianni, L. et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 13, 25–32 (2012).

Xu, Q. Q. et al. HER2 amplification level is not a prognostic factor for HER2-positive breast cancer with trastuzumab-based adjuvant treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 7, 63571–63582 (2016).

Zabaglo, L. et al. HER2 staining intensity in HER2-positive disease: relationship with FISH amplification and clinical outcome in the HERA trial of adjuvant trastuzumab. Ann. Oncol. 24, 2761–2766 (2013).

Mass, R. D. et al. Evaluation of clinical outcomes according to HER2 detection by fluorescence in situ hybridization in women with metastatic breast cancer treated with trastuzumab. Clin. Breast Cancer 6, 240–246 (2005).

Press, M. F. et al. HER2 gene amplification testing by Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH): comparison of the ASCO-College of American Pathologists Guidelines With FISH Scores Used for Enrollment in Breast Cancer International Research Group Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 3518–3528 (2016).

Suydam, C. et al. Are there more HER2 FISH in the Sea? An Institution’s experience in identifying HER2 positivity using fluorescent in situ hybridization in patients with HER2 negative immunohistochemistry. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 31, 376–381 (2024).

Veeraraghavan, J. et al. De-escalation of treatment in HER2-positive breast cancer: determinants of response and mechanisms of resistance. Breast 34, S19–S26 (2017).

Weinstein, I. B. Addiction to oncogenes-the Achilles heal of cancer. Science 297, 63–64 (2002).

Carey, L. A. et al. Molecular heterogeneity and response to neoadjuvant human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 targeting in CALGB 40601, a randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus trastuzumab with or without lapatinib. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 542 (2016).

Ng, C. K. et al. Intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity and alternative driver genetic alterations in breast cancers with heterogeneous HER2 gene amplification. Genome Biol. 16, 1–21 (2015).

Schettini, F. et al. HER2-enriched subtype and pathological complete response in HER2-positive breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 84, 101965 (2020).

Davey, M. G. et al. Clinicopathological response to neoadjuvant therapies and pathological complete response as a biomarker of survival in human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 enriched breast cancer–a retrospective cohort study. Breast 59, 67–75 (2021).

Shen, G. et al. Meta-analysis of HER2-enriched subtype predicting the pathological complete response within HER2-positive breast cancer in patients who received neoadjuvant treatment. Front. Oncol. 11, 632357 (2021)

Prat, A. et al. HER2-Enriched Subtype and ERBB2 Expression in HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Treated with Dual HER2 Blockade. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 112, 46–54 (2020). p.

Lesurf, R. et al. Genomic characterization of HER2-positive breast cancer and response to neoadjuvant trastuzumab and chemotherapy-results from the ACOSOG Z1041 (Alliance) trial. Ann. Oncol. 28, 1070–1077 (2017).

Llombart-Cussac, A. et al. HER2-enriched subtype as a predictor of pathological complete response following trastuzumab and lapatinib without chemotherapy in early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer (PAMELA): an open-label, single-group, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 545–554 (2017).

Rakha, E. A. et al. Assessment of predictive biomarkers in breast cancer: challenges and updates. Pathobiology 89, 263–277 (2022).

Giuliano, M., Trivedi, M. V. & Schiff, R. Bidirectional crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 signaling pathways in breast cancer: molecular basis and clinical implications. Breast Care 8, 256–262 (2013).

Lee, A. V., Cui, X. & Oesterreich, S. Cross-talk among estrogen receptor, epidermal growth factor, and insulin-like growth factor signaling in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 4429s–4435s (2001).

Osborne, C. K. & Schiff, R. Estrogen-receptor biology: continuing progress and therapeutic implications. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 1616–1622 (2005).

Schiff, R. et al. Cross-talk between estrogen receptor and growth factor pathways as a molecular target for overcoming endocrine resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 331s–336s (2004).

Vaz-Luis, I., Winer, E. P. & Lin, N. U. Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-positive breast cancer: does estrogen receptor status define two distinct subtypes?. Ann. Oncol. 24, 283–291 (2013).

Zhang, H. et al. ErbB receptors: from oncogenes to targeted cancer therapies. J. Clin. Investig. 117, 2051–2058 (2007).

Martin, L.-A. et al. Enhanced estrogen receptor (ER) α, ERBB2, and MAPK signal transduction pathways operate during the adaptation of MCF-7 cells to long term estrogen deprivation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 30458–30468 (2003).

Shou, J. et al. Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance: increased estrogen receptor-HER2/neu cross-talk in ER/HER2–positive breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 96, 926–935 (2004).

Rimawi, M. F. et al. Multicenter phase II study of neoadjuvant lapatinib and trastuzumab with hormonal therapy and without chemotherapy in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing breast cancer: TBCRC 006. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 1726–1731 (2013). p.

Wang, Y.-C. et al. Different mechanisms for resistance to trastuzumab versus lapatinib in HER2- positive breast cancers - role of estrogen receptor and HER2 reactivation. Breast Cancer Res. 13, R121 (2011).

Loi, S. et al. Effects of estrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 levels on the efficacy of Trastuzumab: a secondary analysis of the HERA trial. JAMA Oncol. 2, 1040–1047 (2016).

Fumagalli, D. et al. RNA sequencing to predict response to neoadjuvant anti-HER2 therapy: a secondary analysis of the NeoALTTO randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 3, 227–234 (2017).

Harbeck, N. et al. De-Escalation Strategies in Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2)–Positive Early Breast Cancer (BC): Final Analysis of the West German Study Group Adjuvant Dynamic Marker-Adjusted Personalized Therapy Trial Optimizing Risk Assessment and Therapy Response Prediction in Early BC HER2- and Hormone Receptor–Positive Phase II Randomized Trial—Efficacy, Safety, and Predictive Markers for 12 Weeks of Neoadjuvant Trastuzumab Emtansine With or Without Endocrine Therapy (ET) Versus Trastuzumab Plus ET. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 3046–3054 (2017).

Bardia, A. et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1529–1541 (2021)

Rugo, H. S. et al. Overall survival with sacituzumab govitecan in hormone receptor-positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer (TROPiCS-02): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet 402, 1423–1433 (2023).

Bardia, A. et al. TROPION-Breast01: Datopotamab deruxtecan vs chemotherapy in pre-treated inoperable or metastatic HR+/HER2- breast cancer. Future Oncol. 20, 423–436 (2024). p.

Gennari, A. et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1475–1495 (2021).

Loibl, S. et al. Breast cancer. Lancet 397, 1750–1769 (2021).

Corti, C. et al. Systemic therapy in breast cancer. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 44, e432442 (2024).

Alaklabi, S. et al. Real-world clinical outcomes with sacituzumab govitecan in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 21, 620–628 (2025).

Belloni, S. et al. Prevalence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) with antibody-drug conjugates in metastatic breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 204, 104527 (2024).

D’Arienzo, A. et al. Toxicity profile of antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: practical considerations. eClinicalMedicine 62 (2023).

Guo, Z. et al. Safety of trastuzumab deruxtecan: a meta-analysis and pharmacovigilance study. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 47, 1837–1844 (2022).

Kang, S. & Kim, S. B. Toxicities and management strategies of emerging antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 17, 17588359251324889 (2025).

Denkert, C. et al., Biomarker Data From the Phase III KATHERINE Study of Adjuvant T-DM1 Versus Trastuzumab for residual invasive disease after Neoadjuvant Therapy for HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. (2023).

Barok, M. et al. Trastuzumab-DM1 causes tumour growth inhibition by mitotic catastrophe in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells in vivo. Breast Cancer Res. 13, R46 (2011).

Lewis Phillips, G. D. et al. Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer with trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody–cytotoxic drug conjugate. Cancer Res. 68, 9280–9290 (2008).

Montemurro, F., Di Cosimo, S. & Arpino, G. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive and hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: new insights into molecular interactions and clinical implications. Ann. Oncol. 24, 2715–2724 (2013).

Lønning, P. E. Poor-prognosis estrogen receptor- positive disease: present and future clinical solutions. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 4, 127–137 (2012).

Finn, R. S. et al. PD 0332991, a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor, preferentially inhibits proliferation of luminal estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Breast Cancer Res. 11, 1–13 (2009).

Goel, S. et al. Overcoming therapeutic resistance in HER2-positive breast cancers with CDK4/6 inhibitors. Cancer Cell 29, 255–269 (2016).

Turner, N. C. et al. Overall survival with palbociclib and fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1926–1936 (2018).

Im, S.-A. et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus endocrine therapy in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 307–316 (2019).

Tolaney, S. M. et al. Abemaciclib plus trastuzumab with or without fulvestrant versus trastuzumab plus standard-of-care chemotherapy in women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (monarcHER): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 21, 763–775 (2020).

Ciruelos, E. et al. Palbociclib and trastuzumab in HER2-positive advanced breast cancer: results from the phase II SOLTI-1303 PATRICIA trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 5820–5829 (2020).

Metzger, O. et al. AFT-38 PATINA: a randomized, open label, phase III trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of palbociclib + anti-HER2 therapy + endocrine therapy vs anti-HER2 therapy + endocrine therapy after induction treatment for hormone receptor-positive/HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer., In San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. San Antonio, TX. (2024).

Martínez-Sáez, O. et al. Frequency and spectrum of PIK3CA somatic mutations in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 22, 1–9 (2020).

Jain, S. et al. Phase I study of alpelisib (BYL-719) and trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC) after trastuzumab and taxane therapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 171, 371–381 (2018).

Bardia, A. et al. Abstract OT-03-09: Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd; DS-8201) vs investigator’s choice of chemotherapy in patients with hormone receptor-positive (HR + ), HER2 low metastatic breast cancer whose disease has progressed on endocrine therapy in the metastatic setting: A randomized, global phase 3 trial (DESTINY-Breast06). Cancer Res. 81, OT-03-09–OT-03-09 (2021).

Pérez-García, J. M. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with central nervous system involvement from HER2-positive breast cancer: the DEBBRAH trial. Neuro-oncology 25, 157−166 (2023).

Véronique Diéras, E., Amélie, L. & Barbara, P. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) for advanced breast cancer patients (ABC), regardless HER2 status: a phase II study with biomarkers analysis (DAISY). in Proceedings of the 2021 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium AACR. Cancer Res. (2022).