Abstract

Atomic-scale intrinsic defects play a key role in controlling functional electronic properties of two-dimensional (2D) materials. Here, we present a low-temperature scanning–tunneling microscopy and spectroscopy investigation of a common point-defect in monolayer molybdenum disulfide (MoS2). We employ a sample preparation method in which the film surface is never exposed to air so that the native dangling bonds surrounding the defects in the film are preserved. Molybdenum vacancies are identified by their three characteristic in-gap resonances by combining scanning–tunneling measurements with parallel Green’s function-based theoretical modeling. The relative energy shifts between the various in-gap states allow us to identify a relative charge difference between two of the observed vacancies. The role of the substrate on the band structure of the defective MoS2 monolayer is unveiled. Our study highlights the effects of the substrate on the in-gap states of common defects found in MoS2 providing a pathway in designing and optimizing 2D materials for electronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electronic properties of 2D materials, such as graphene and monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), are more sensitive to structural defects than their bulk counterparts due to their atomically thin nature. This sensitivity presents an opportunity to functionalize 2D materials through defect engineering, much like what has been done in the silicon industry1. For example, defects have been intentionally introduced in semiconducting MoS2 to improve its optical response2, induce magnetism3 or enhance catalytic activity4,5. Similarly, defects in other TMDs have been shown to funnel excitons to act as single-photon emitters—a critical component of the quantum-information processing ecosystem6,7,8,9. The reduced electron screening that makes defect engineering a powerful tool in 2D materials can also yield undesirable consequences. As an example, MoS2 monolayer films exhibit carrier mobilities well below the theoretical limit due to the effects of disorder, defects, and impurities10,11,12,13. Studies show that charged defects such as sulfur and molybdenum vacancies act as electron acceptors to produce deep in-gap states14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, which drive desirable optical properties that can be leveraged for nanophotonic applications6. Despite the extensive literature on the topic, the correlation between point defects and their in-gap states has experimentally remained elusive. This is primarily due to the fact that the dangling bonds at the defect sites are rapidly quenched by the contaminants in the air due to their high reactivity, which makes it challenging to experimentally access these pristine defect states.

In this work, we overcome this obstacle by utilizing a sample fabrication method in which the surface of a monolayer MoS2 film is never exposed to air, so that the native electronic properties of the point defects are properly preserved. We employ low-temperature scanning–tunneling microscopy/spectroscopy (LT-STM/STS) and conductance-imaging-tunneling spectroscopy (CITS) to identify molybdenum vacancies in two distinct charge states. Parallel theoretical modeling is carried out to interpret and analyze the results. We map the in-gap resonances as a function of both position and energy and show that their experimentally observed spatial distribution is in reasonable accord with the corresponding (real-space) density of states calculations. Our study provides insight into the atomic-scale electronic properties of the defective landscape of MoS2 monolayers.

Results and discussion

Identification of point defects

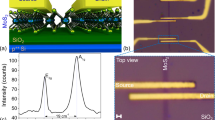

Monolayer MoS2/Pb samples were produced using the “flip-chip” technique25. In this method, the MoS2 is first deposited onto a sapphire substrate via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and a 100 nm Pb film is later evaporated on top. The Pb side of the sample is then glued to an STM sample holder and the sapphire side is glued to a cleaving post which is used to cleave the sapphire away from the MoS2 in ultra-high vacuum (UHV). Details of the fabrication method are reported elsewhere26. This procedure is naturally beneficial for the study of native defects compared to conventional preparation methods primarily because the measured monolayer film is sandwiched between the Pb and the sapphire substrate during preparation. As a result, it is protected from undesirable oxidation of dangling bonds arising from structural defects which are known to alter the density of states27. This method thus provides a platform for measuring the electronic structure of the pristine defect site. Another advantage is that it circumvents the need for UHV heating which is conventionally used to remove water and other contaminants from the film surface prior to STM characterization, but this process creates additional defects in the film28.

STM topographic images show that the surface of our films exhibits two distinct domains: one where the MoS2 is well adhered to the Pb substrate, displaying proximity-induced superconductivity26, and another region that exhibits semiconducting properties, where there is less interaction between MoS2 and Pb (see Supplementary Fig. 1). A typical large-area STM topographic map of the semiconducting MoS2 monolayer surface is shown in Fig. 1a. The step-like features on the surface do not come from multiple layers of MoS2 but result from the impression of the terraced surface of the c-axis cut sapphire substrate on which the film was originally grown29. The high-resolution STM topographies in Figs. 1b and c reveal two common defects both of which appear as depressions in the images obtained by scanning with positive bias. When the defect in Fig. 1c is imaged with negative polarity, however, it appears as a three-lobed protrusion (Fig. 1d). While the chemical structure of these defects cannot be determined using STM alone, it can be inferred from their density, lattice site, and influence over the local electronic density of states. For example, the defect in Fig. 1b is likely to be a sulfur vacancy (VS) as it is the most common defect found in this sample with a density of 2.9 × 1012 cm−2, it forms at a sulfur lattice site and it appears as a depression independent of the scanning bias (see Supplementary Fig. 2). VS is expected to be the most abundant defect due to its low formation energy; its density here is in good agreement with the values reported for other CVD-grown MoS2 films in the literature15,16,21. We further corroborate our inference by performing an STM simulation of the VS in constant current mode (Fig. 1e). The simulated image reasonably captures the feature from Fig. 1b depicting a depression at the VS site surrounded by an immediate protrusion. Similarly, we infer that the defect in Fig. 1c and d is a molybdenum vacancy (VMo) based on its density and influence over the local electronic density of states. Specifically, it is found to have a density of 3.4 × 1011 cm2, which is an order of magnitude smaller than for the VS and consistent with the reported values of the density of the VMo in CVD-grown MoS2 films21. In addition, our STM simulations for a VMo imaged with positive (Fig. 1f) and negative polarity (Fig. 1g) correctly capture the depression and three-lobed protrusions in Fig. 1c and d, respectively.

a Large-area STM topography showing the native defects on a semiconducting region of MoS2 (Vset = 1.0 V, Iset = 30 pA). Scale bar represents 50 nm. b Atomic resolution STM topography acquired over a sulfur vacancy (Vset = 100 mV, Iset = 100 pA). c, d Atomic resolution of a molybdenum vacancy acquired in the empty (Vset = 1.0 V) and filled (Vset = −2.0 V) state, respectively (Iset = 100 pA). e–g Constant current STM topography simulations of the defects in panels b–d with bias set to V = 100 mV, 1.0 V and −1.0 V, respectively. Scale bars for panels b–g represent 0.5 nm.

Electronic characterization of VMo

To further investigate the influence of the VMo over the local electronic density of states we acquire tunneling spectra (dI/dV curves) at the defect locations (Fig. 2a, b). Both spectra exhibit three resonances located between the Fermi level (EF) and the valence band maximum (VBM). Although these three in-gap states exist in both spectra, they are shifted in energy by ~100 meV, appearing at 0.4 (0.3), 0.9 (0.8), and 1.8 eV (1.7 eV) below the EF for the defect circled in red (blue). A similar energy offset has been predicted in the first-principles calculations of Noh et al.16, where the three in-gap states of a charged VMo are found to exhibit a relative shift in energy with respect to its neutral counterpart. Moreover, Noh et al. predict that the charged VMo is stable in n-doped MoS2 where the conduction band minimum (CBM) is close to the EF16.

a STM topography zoomed in on the two primary defects shown in Fig.1b (Vset = 1.0 V, Iset = 100 pA). The inset shows the same area acquired with V = −2.0 V. Scale bar represents 1 nm. b STS acquired on top of the two defects in (a) where the red (blue) curve is acquired over the defect outlined with the red (blue) dashed circle (Vset = 1.0 V, Iset = 100 pA) in (a). The gray curve is a spatially averaged dI/dV spectra acquired far from the defects on pristine MoS2. c The transmission coefficient t between the bottom Pb layer and the orbitals of S on a pristine overlayer (blue solid curve) and in the presence of a Mo defect (magenta solid curve). As a comparison, the corresponding PDOS spectra projected to the top sulfur layer are presented (black and red dashed lines for the pristine and defected case, respectively).

Figure 2b also presents a spectrum acquired far from the defect sites (gray curve) to show the reference energies of the VBM and CBM where the latter is notably closer to the EF. Compared to the dI/dV spectra taken from MoS2 films on graphite30, the CBM here is closer to the EF, which is likely due to the interaction with the Pb substrate. This interaction is not strong enough to induce metallicity in MoS2 but it produces an intermediate semiconducting state with an altered band gap. The observed in-gap states in Fig. 2b have been labeled in keeping with the notation used in the computations of ref. 16, which also show the presence of a fourth defect state within the valence band. Since the defect creates a local perturbation of Cv3 symmetry, so that the associated wavefunctions belong to the irreducible representations A1 and E. The two in-gap states with the highest energy have wavefunctions that involve hybridization between the p-orbitals of S and d-orbitals of the neighboring Mo atoms, and accordingly these states are labeled as a1-pd and e-pd, the latter being a doublet. The lower energy defect states have wavefunctions that involve only on the p-orbitals of S atoms, and hence the notation e-p, which is a doublet, and a1-p, which is a singlet state that lies deeper in the valence bands.

Unlike the theoretical density of states of the VMo, our tunneling spectra also show the presence of states between the three in-gap resonances (compare Fig. 2b, c). This is a well-known consequence of tunneling from the filled states of the sample into the empty states of a metallic tip31,32. Note that the states at EF have the highest probability of tunneling into the tip and this probability reduces exponentially as a function of energy. Therefore, when the tunneling bias falls between two filled-state resonances, there is a probability of tunneling from electrons in states closer to EF31,32. As a result, the features that arise from the in-gap resonances appear as steps in the tunneling spectra moving away from the EF. The agreement between theory and experiment with regard to the energies of the defect states indicates that the dangling bonds associated with these defects remain free of contamination in our samples.

Tight-binding model

In order to model the effects of substrate–film interaction on the density of states, we use the following material-specific tight-binding Hamiltonian

where we modified the parameters slightly from the values we used previously in ref. 26 to model MoS2 on Pb, see “Methods” for details. We emphasize that the energy, symmetry, and orbital character of the theoretically found in-gap defect states provide important fingerprints for identifying these defects in the experimental spectra. Spectral weights in the dI/dV spectra and the topographic patterns in the STM images associated with various defects, however, depend on the details of the tunneling matrix element and the related tunneling pathways between the tip and surface orbitals, which in turn depend not only on the overlayer-substrate interaction but also on how the overlayer orbitals are hybridized.

Our tight-binding parametrization of pristine MoS2 only captures the a1-pd and e-pd states within the gap and not the states that lie deeper in the valence band since this model does not account for defect-induced charge transfer. However, a 2 eV shift of the onsite energies of the p-orbitals of the sulfur atoms next to the defect shifts the two aforementioned pd states only slightly upwards but it makes the third defect state (e-p) to emerge slightly above the VBM; the fourth defect state also appears in the valence bands, but in our calculations, it is more hybridized with the valence bands than the a1-pd state in ref. 16. The a1-pd and e-pd states possess a mixed character and involve both the p-orbitals of S and the d-orbitals of Mo. The two lower energy defect states (a1-p and e-p) are dominated by the p-orbitals of sulfur.

In order to gain further insight into the experimental dI/dV spectra, we consider the effect of the Pb substrate by evaluating the transmission coefficient from the bottom Pb layer through the surface S layer and compare it with the partial density of states (PDOS) projections onto the sulfur orbitals of the surface layer. In Fig. 2c, the dashed lines show the PDOS projected on the orbital of a top-layer S atom for the pristine case (black) and of an S atom in the vicinity of the defect using half interaction with the substrate (red). (see “Methods” and the Supplementary Note 1 for a discussion of the half-interaction and full-interaction computations for modeling substrate effects.) Solid lines show the transmission coefficient (τ) between the bottom layer of the Pb substrate and the orbitals of an S atom in the pristine case (blue) and near the defect (magenta). While the transmission from the substrate to the defect states is seen to merely broaden the lower defect peak, more dramatic is the difference in the overall spectrum. The substrate appears to be strongly connected to the overlayer states at energies close to the valence band, especially in the presence of a defect, suggesting that the substrate provides a significant contribution to the strong background towards negative energies seen in the experimental dI/dV spectra (Fig. 2b).

Spatial perturbation of the density of states

In addition to the three characteristic in-gap states present around both the defects, we observe an upward band bending of the CBM. Figure 3a and b shows the measured spectra directly above VMo #1 and #2, respectively, over an energy range that extends well into the conduction band. For reference, a spectrum acquired on the pristine film, far from these defects, is shown (gray color) in both plots. Figure 3c and d presents line-cuts through the spectra acquired over a distance of 4.75 nm centered over VMo #1 and #2, respectively, and show that the e-pd and a-pd states are localized in a region within +/− 1 nm of the VMo site. In contrast, the local bending of the CBM away from the EF extends to +/− 2 nm of the VMo site. The CBM shift is evidence for the presence of a local potential induced by a localized charge, which pushes the CBM away from the EF. Details of the band-bending effect depend on those of the electrostatic potential and how it is screened in the system involving the MoS2 film, Pb substrate, and the tip33. The observed shift in the in-gap states and the conduction band edge between VMo #1 and #2 indicates that there is a relative charge difference between the two vacancies, with VMo #2 being more negative.

a, b STS acquired on top of the charged defect #1 (red) and #2 (blue), respectively, with the spectrum acquired on the pristine MoS2 film (gray) plotted for comparison (Vset = 1.0 V, Iset = 100 pA). The black dashed lines represent the energies of the a1-pd and e-pd states. c, d STS line profiles of length 4.75 nm centered over the defects in (a, b), respectively. The white dashed arrows represent the a1-pd and e-pd states while the white dashed line labeled CBM represents the energy of the conduction band minima of the pristine MoS2 film.

The energy offset between the two VMo defects is further demonstrated by the conductance maps in Fig. 4a–d acquired over the same area as Fig. 2a. The localized a1-pd and e-pd states from the VMo #2 (outlined in blue in Fig. 2a) systematically emerge in the map at a lower energy than those originating from its neighboring VMo #1 (outlined in red in Fig. 2a). Qualitative similarities are present between the spatial distribution of the VMo #2 conductance at −0.33 eV (Fig. 4e) and the real-space projection of the a1-pd (Fig. 4f). In particular, the dominant intensity protrudes from the center of the vacancy to the three neighboring sulfur atoms (dashed ovals in Fig. 4e and f). This contrasts with the spatial distribution of the VMo #2 conductance at −0.84 eV (Fig. 4g) where the primary intensity is more evenly dispersed around the perimeter of the defect. Thus, we find a defective state at −0.84 eV that is spatially more rounded than the state at −0.33 eV, in agreement with the real-space projection of the e-pd state (Fig. 4h). The patterns of the real-space projections are in reasonable accordance with the constant density contours shown in ref. 16, and the symmetry of the representations of the Cv3 group is clearly seen. In addition, the p-d hybridized nature of the a1-pd and e-pd defect states is obvious compared to the p (sulfur)-character of the e-p state. However, it should be noted that the calculated images here are PDOS maps projected on a plane at a given height. Direct comparisons between the PDOS and STM conductance images are not straightforward because different defect states can have very different transmission channels to the conducting substrate. Figure 2c shows an example where there is a relatively low transmission coefficient between a1-pd and e-pd states and the substrate. The patterns of especially the pd states are not sensitive to substrate-overlayer interaction, although the background emerging from the valence band is affected by this interaction.

a–d A series of four CITS maps acquired over the same location shown in Fig. 2a with the energy of each map shown in the upper right corner of their respective panels. Scale bars represent 1 nm. e The map acquired at −0.33 eV magnifying the defect outlined in the white dashed box in (a). f The real-space projection of the density of states at the energy of the a1-pd defect state at a level of 0.1 Å above the upper Sulfur layer. g The map acquired at −0.84 eV magnifying the defect outlined in the white dashed box in (c). h The real-space projection of the density of states at the energy of the e-pd defect state at a level of 0.1 Å above the upper Sulfur layer. Scale bars for (e–h) represent 0.5 nm. The grid of white lines in (f, h) represents the horizontal primitive cells of the MoS2 where the purple and yellow spheres in the upper left-hand corner indicate the positions of the molybdenum and sulfur atoms, respectively.

Effect of the Pb substrate

The strongly energy-dependent transmission probability affects the contrast of the defects in the topographic images and conductance maps. For example, the PDOS at the defect states of pd character is quite high (Fig. 2c), but the spectral intensity of these states will be reduced by the relatively low value of the associated tunneling matrix element. The increasing transmission probability as we go towards the valence band energies would increase the contrast of the defect image.

Figure 5a shows the simulation supercell we used for modeling the defect states. It consists of a 4 × 4 horizontal supercell for MoS2 on a 3 × 3 Pb substrate26. Figure 5b presents the PDOS projection of the orbitals of the MoS2 layer for different substrate-overlayer interaction strengths. In the case of no interaction (black curve), there are three peaks in the gap. Comparing the no interaction and half-interaction (red curve) cases, the two mid-gap spectral peaks are seen to remain essentially intact. When the full-interaction strength (blue curve) is turned on, the presence of the Pb-induced states becomes clearer within the gap. The evolution of the PDOS at different substrate-overlayer interaction strengths indicates that the a1-pd state hybridizes with the Pb states, since the corresponding PDOS peak broadens with increasing interaction. However, the unfolded band structures of Fig. 5c–e (see “Methods” for details) show that the in-gap states with pd character are not sensitive to the substrate. A comparison of Fig. 5c and d shows (half-interaction case) that the a1-pd state is close to the K-point, while the e-pd state spans momenta over the K- M symmetry line in the momentum space. The a1-pd and e-pd states are seen to be intact at all three interaction strengths considered in Fig. 5. The third state (e-p) lies over a wide range of momenta and appears to be coupled to the substrate in a more complicated way compared to the two other in-gap states.

a The simulation cell used in calculations. b PDOS projected to the MoS2 overlayer at three different interaction strengths, no interaction (black), half interaction (red) and full interaction (blue). c The band structure of MoS2 in the case of half interaction with the substrate with a defect with bands unfolded to the BZ of a primitive cell of MoS2. d, e The same as Fig. 4c but with no interaction and full interaction with the substrate, respectively. f The same as in Fig. 4c, i.e., with half interaction but without any defect.

In summary, our study demonstrates that the “flip-chip” sample preparation method can preserve dangling bonds at defect sites and that the associated in-gap resonances can be identified in their tunneling spectrum. For this purpose, we focus on molybdenum vacancies, a common defect observed on semiconducting MoS2 monolayers with a density of 3.4 × 1011 cm−2. These defects exhibit localized in-gap states whose measured spatial distributions are reasonably described by our computed real-space projections of the a1-pd and e-pd states. The three in-gap states related to the Mo vacancy (VMo) are found to be shifted in energy suggesting that they exist in two distinct charged states. We interpret and analyze our experimental results by varying the strength of the substrate–film interaction in our modeling and show that states with pd character are insensitive to the substrate while the e-p defect state exhibits a complex coupling with the substrate. While the vacancy defects we have identified, which are electron acceptors, cannot account for the intrinsic n-type doping of the investigated films, these defects nevertheless substantially alter the local electronic density of states of the MoS2 monolayer. Our study provides insight into the atomic-scale electronic properties of the defective landscape of MoS2 monolayers for next generation defect engineering of 2D materials.

Methods

STM/STS

Scanning–tunneling microscopy and spectroscopy measurements were carried out using a Unisoku STM with PtIr tip in ultra-high vacuum (<10−11 Torr) at T = 1.5 K. The sapphire was cleaved from the MoS2/Pb in UHV and the sample was immediately transferred to the STM without breaking vacuum. The PtIr tip used in this experiment was previously prepared on a Au single crystal. The STM images were recorded in constant current mode and the dI/dV spectra were recorded using a lock-in technique with a modulation amplitude and frequency of 20 mV and 373.1 Hz, respectively.

Tight-binding Hamiltonian and Green’s function

In Eq. (1), \({{{c}}}_{{{\upalpha }}{{\upsigma }}}^{{{\dagger }}}\) (\({{{c}}}_{{{\upalpha }}{{\upsigma }}}\)) is the real-space creation (annihilation) operator, the composite indices α and β encode both the site and orbital information, and σ is the spin index. Other terms are the onsite orbital energy εα and the off-diagonal matrix elements Vαβ between the α and β orbitals based on Slater–Koster hopping integrals34 and the tables of Harrison35. The overlap integrals between the atomic orbitals of two atoms can be separated into two parts: an angular part, which depends on the orientation of the two orbitals, and an amplitude part that depends on the type of bonding between the two orbitals (sigma, pi, or delta), see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for details. The main difference in our parameterization compared to that of ref. 26 is that we consider three different values for the interfacial S–Pb matrix elements in order to simulate different strengths of overlayer-substrate interaction: no interaction, half interaction, and full interaction, see Supplementary Note for details. Our basic simulation cell consists of a 1 ML MoS2 overlayer with a 4 × 4 supercell structure on a three-layer Pb slab with 6 × 6 atoms in the horizontal direction, see Fig. 4a. For the defect, one Mo atom from the overlayer is removed without any relaxation, since previous computational studies16 indicate a relatively small relaxation.

The Green’s function related to the Hamiltonian above:

is used to calculate the unfolded band structures, partial densities of states (PDOSs), and the transmission through the Pb substrate and the MoS2 overlayer. While the substrate is modeled as a finite slab instead of a recursively created semi-infinite slab, a self-energy term is added to the bottom layer of the Pb slab for transmission calculations with features of a conducting lead with constant density of states and a homogenous interaction with the bottom Pb layer. The principal quantity obtained from the Green’s function matrix of Eq. (2) is the density matrix:

The matrix elements \({\rho }_{{\upalpha }{\sigma }{\beta }{{\sigma }}^{{\prime} }}\left(E,{\boldsymbol{k}}\right)\) of the density matrix are used for computing the orbital projections of states. For projecting the electron density into real space, we use Slater-orbitals φα(r-Ri)

While \({\rho }_{{\upalpha }{\upsigma }{\upbeta }{{\upsigma }}^{{\prime} }}\left(E,{\boldsymbol{k}}\right)\) is used to analyze the experimental dI/dV spectra in the Tersoff–Hamann approach36, we also obtain transmission from the bottom of the substrate using the function

where subscripts b and t denote the bottom layer of the substrate and the chosen orbitals of the overlayer. For simplicity, Γb/t is taken to be a constant.

Unfolding the bands

In order to unfold the bands, the matrix elements of the Green’s function can be augmented with a phase factor with respect to the coordinates of atoms within a chosen primitive cell:

where μ0 is orbital μ in the central primitive cell within the supercell and μn is orbital μ in the nth cell. rμ,n is the position of orbital μ in cell n. The Green’s function \({G}_{{\upmu }0,{\upmu }0}^{{\rm{uf}}}\left({\boldsymbol{k}},E\right)\,\) is then used to derive the corresponding density matrix:

The appropriate elements of the density matrix is plotted as a function of k and E in order to obtain the unfolded dispersion.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study are not available in the public domain. However, the authors will be happy to discuss an appropriate accommodation for reasonable requests.

References

Lin, Z. et al. Defect engineering of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. 2D Mater. 3, 022002 (2016).

Wu, K. et al. Controllable defects implantation in MoS2 grown by chemical vapor deposition for photoluminescence enhancement. Nano Res. 11, 4123–4132 (2018).

Han, S. W. et al. Controlling ferromagnetic easy axis in a layered MoS2 single crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 247201 (2013).

He, Z. et al. Defect engineering in single-layer MoS2 using heavy ion irradiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 42524–42533 (2018).

Zhang, H. & Lv, R. Defect engineering of two-dimensional materials for efficient electrocatalysis. J. Materiomics 4, 95–107 (2018).

Liu, X. & Hersam, M. C. 2D materials for quantum information science. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 669–684 (2019).

Koperski, M. et al. Single photon emitters in exfoliated WSe2 structures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 503–506 (2015).

Srivastava, A. et al. Optically active quantum dots in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 491–496 (2015).

He, Y.-M. et al. Single quantum emitters in monolayer semiconductors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 497–502 (2015).

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Qiu, H. et al. Hopping transport through defect-induced localized states in molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 4, 2642 (2013).

Ghatak, S., Pal, A. N. & Ghosh, A. Nature of electronic states in atomically thin MoS2 field-effect transistors. ACS Nano 5, 7707–7712 (2011).

Chhowalla, M., Jena, D. & Zhang, H. Two-dimensional semiconductors for transistors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16052 (2016).

Kunstmann, J., Wendumu, T. B. & Seifert, G. Localized defect states in MoS2 monolayers: electronic and optical properties. Phys. Status Solidi B Basic Res. 254, 1600645 (2017).

Komsa, H.-P. & Krasheninnikov, A. V. Native defects in bulk and monolayer MoS2 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 91, 125304 (2015).

Noh, J.-Y., Kim, H. & Kim, Y.-S. Stability and electronic structures of native defects in single-layer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 89, 205417 (2014).

Zhou, W. et al. Intrinsic structural defects in monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett. 13, 2615–2622 (2013).

Yang, J., Kawai, H., Wong, C. P. Y. & Goh, K. E. J. Electrical doping effect of vacancies on monolayer MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 2933–2939 (2019).

Vancsó, P. et al. The intrinsic defect structure of exfoliated MoS2 single layers revealed by scanning tunneling microscopy. Sci. Rep. 6, 29726 (2016).

Saha, A. K. & Yoshiya, M. Native point defects in MoS2 and their influences on optical properties by first principles calculations. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 532, 184–194 (2018).

Hong, J. et al. Exploring atomic defects in molybdenum disulphide monolayers. Nat. Commun. 6, 6293 (2015).

Enyashin, A. N., Bar-Sadan, M., Houben, L. & Seifert, G. Line defects in molybdenum disulfide layers. J. Phys. Chem. C. 117, 10842–10848 (2013).

Klein, J. et al. Site-selectively generated photon emitters in monolayer MoS2 via local helium ion irradiation. Nat. Commun. 10, 2755 (2019).

Lu, C.-P., Li, G., Mao, J., Wang, L.-M. & Andrei, E. Y. Bandgap, mid-gap states, and gating effects in MoS2. Nano Lett. 14, 4628–4633 (2014).

Flötotto, D. et al. Superconducting pairing of topological surface states in bismuth selenide films on niobium. Sci. Adv. 4, 7214 (2018).

Trainer, D. J. et al. Proximity-induced superconductivity in monolayer MoS2. ACS Nano 14, 2718–2728 (2020).

Barja, S. et al. Identifying substitutional oxygen as a prolific point defect in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 10, 3382 (2019).

Precner, M. et al. Evolution of metastable defects and its effect on the electronic properties of MoS2 films. Sci. Rep. 8, 6724 (2018).

Wang, R., Guo, D., Xie, G. & Pan, G. Atomic step formation on sapphire surface in ultra-precision manufacturing. Sci. Rep. 6, 29964 (2016).

Trainer, D. J. et al. Moiré superlattices and 2D electronic properties of graphite/MoS2 heterostructures. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 128, 325–330 (2019).

Sutter, P., Zahl, P., Sutter, E. & Bernard, J. E. Energy-filtered scanning tunneling microscopy using a semiconductor tip. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 166101 (2003).

Sutter, P. Scanning Tunneling Microscopy in Surface Science, Chapter 27 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Le Quang, T. et al. Band-bending induced by charged defects and edges of atomically thin transition metal dichalcogenide films. 2D Mater. 5, 035034 (2018).

Slater, J. C. & Koster, G. F. Simplified LCAO method for the periodic potential problem. Phys. Rev. 94, 1498–1524 (1954).

Harrison, W. A. Electronic Structure and the Properties of Solids—The Physics of the Chemical Bond. (Dover, 1989).

Tersoff, J. & Hamann, D. R. Theory of the scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. B 31, 805–813 (1985).

Acknowledgements

The work at Temple University was supported by the Center for Complex Materials from First-Principles (CCM), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences under Award No. DE-SC0012575. The work at Northeastern University was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences Grant No. DE-SC0019275 and benefited from Northeastern University’s Advanced Scientific Computation Center and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center through DOE Grant No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. J.N. benefited from the resources of the Tampere Center for Scientific Computing, TCSC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.J.T. and F.B. performed low-temperature STM/STS measurements under the guidance of M.I. at Temple University. D.J.T. fabricated MoS2 films under the guidance of X.X.X. J.N., B.W., and A.B. carried out the theoretical computations and analysis. All authors participated in the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Trainer, D.J., Nieminen, J., Bobba, F. et al. Visualization of defect induced in-gap states in monolayer MoS2. npj 2D Mater Appl 6, 13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-022-00286-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-022-00286-9

This article is cited by

-

Gating monolayer and bilayer graphene with a two-dimensional semiconductor

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2025)

-

The rise of semi-metal electronics

Nature Reviews Electrical Engineering (2024)

-

200-mm-wafer-scale integration of polycrystalline molybdenum disulfide transistors

Nature Electronics (2024)

-

Advanced 2D molybdenum disulfide for green hydrogen production: Recent progress and future perspectives

Frontiers in Energy (2024)