Abstract

We use time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TR-ARPES) combined with density functional theory to investigate ultrafast carrier dynamics in low-symmetry layered semiconducting PdSe2. The indirect bandgap is determined to be 0.55 eV. Following photoexcitation above this gap, we resolve a valence band shift and broadening, both lasting less than a picosecond, consistent with bandgap renormalization and carrier scattering, indicative of strong many-body interactions. Subsequently, hot carriers populate the conduction band minimum and are captured by defect states. A surface photovoltage (SPV) of ~67 meV emerges, persisting for over 50 ps, driven by defect-assisted charge separation. The formation of native vacancies, promoted by the low-symmetry lattice, likely gives rise to the mid-gap states responsible for this long-lived SPV response. Detailed analysis of TR-ARPES spectra disentangles the contributions of bandgap renormalization, carrier scattering, defect states, and SPV. These findings establish PdSe2 as a prototypical layered quantum material exhibiting exotic photoresponses on ultrafast timescales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum materials composed of stacked van der Waals layers have attracted tremendous attention in scientific research and advanced technology owing to their distinctive quantum effects and remarkable physical properties1,2,3,4,5. Among these is the noble transition metal dichalcogenide (TMDC) PdSe2. Distinct from the widely studied TMDCs such as MoS2, WS2, and WSe2, PdSe2 features a unique puckered layered structure comparable to that of black phosphorus (BP)6,7,8,9, and has recently been shown to induce anisotropic, gate-tunable spin-orbit coupling in two-dimensional heterostructures10. Its corrugated morphology yields a low symmetry, giving rise to exotic properties such as strong in-plane anisotropy7. Moreover, PdSe2 exhibits high chemical stability compared to BP, which suffers from degradation under ambient conditions, thereby limiting its applications8,11,12,13,14. Its crystallographic direction-dependent physical properties, high electron field-effect mobility, and exceptional photodetection performance, with a high quantum efficiency across the visible to mid-infrared range, make it a promising candidate for next-generation electronics, optoelectronics, spintronics, and valleytronics7,15,16,17,18,19,20. Despite recent progress in uncovering various properties of PdSe2, including anisotropic phonon response21,22, oxygen substitution effects23, linear dichroism24, strong anisotropic magnetoresistance25, and pressure-induced superconductivity26,27, its intrinsic electronic band structure and photoexcited carrier dynamics remain relatively unexplored.

The features of the electronic band structure of PdSe2 are still under debate, with studies reporting widely varying band gap values. For the bulk, estimates range from 0 to 0.52 eV7,28,29,30,31, while for the monolayer, values between 1.32 and 1.43 eV have been reported30,32,33,34. These discrepancies are largely attributed to the choice of theoretical models and experimental techniques. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) has recently been applied to investigate the band structure of bulk PdSe235,36,37. Initial ARPES studies identified the valence band (VB) maximum (VBM) at the Brillouin zone (BZ) center. The absence of conduction band (CB) states at or below the Fermi level confirmed the semiconducting character35, in contrast to earlier predictions suggesting a semimetallic nature7. Additional ARPES investigations revealed a highly dispersive electronic band along the interlayer direction, indicative of strong interlayer coupling38. Under in situ electron doping via alkali metal deposition, the CB minimum (CBM) became observable in ARPES measurements, and the indirect band gap was estimated to be approximately 0.36 eV36. However, such doping techniques may alter the intrinsic electronic structure, an effect that has also been observed in other materials, such as in BP, where band modulation and Stark effects have been reported39. More recently, dark states in the VB of PdSe2 were discovered as a result of sublattice interference, rendering certain bands invisible to ARPES across the BZs37. These interference effects stem from multiple glide-mirror symmetries associated with the PdSe2 complex sublattice structure and may be relevant to other quantum materials. Additionally, temperature- and photon energy-dependent valence band asymmetries have been observed40, adding further complexity to the interpretation of static ARPES results.

Although these ARPES-based studies offer valuable insights into the electronic properties of PdSe2, a more direct method to access the unoccupied states, and the bandgap is time-resolved ARPES (TR-ARPES), which in addition enables a study of nonequilibrium carrier dynamics41,42,43. This technique, widely employed in the study of quantum materials, enables simultaneous energy- and momentum-resolved tracking of electronic states in the time-domain following optical excitation with an ultrashort laser pulse. It also allows the investigation of transient processes such as band structure renormalization, carrier relaxation, and coherent phonon coupling, key to the understanding light-matter interactions. In PdSe2, investigations into these ultrafast processes have so far been limited, focusing primarily on its optical response. These studies, mainly using pump-probe THz spectroscopy, revealed a 4.3 THz coherent phonon mode coupled to interlayer charge carriers34. TR-ARPES has emerged as an effective tool in revealing the detailed electronic response in analogous layered materials such as BP, where it has uncovered phenomena such as photoinduced band gap renormalization (BGR), broadening, and Stark effects44,45,46,47. Moreover, TR-ARPES has enabled the exploration of the influence of defect states on carrier dynamics48,49,50, as well as surface photovoltage (SPV) effects and band bending dynamics under photoexcitation51,52,53,54.

Recent theoretical studies have shown that intrinsic point defects in PdSe2, particularly Se vacancies and Pd+Se vacancy complexes, can introduce localized in-gap states and magnetic moments. Owing to the PdSe2 characteristic five-fold morphology, Se vacancies are energetically favorable and highly mobile in both lateral and vertical directions, while Pd vacancies exhibit significantly higher diffusion barriers and remain largely immobile. This anisotropic defect behavior supports the formation of weakly dispersive, real-space localized states that enable charge trapping and internal field modulation in PdSe255,56,57.

In this work, we combine TR-ARPES with density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate the ultrafast carrier dynamics in pristine bulk PdSe2. This approach allows direct population of the conduction band and a precise determination of the indirect band gap. Moreover, we resolve the energy- and momentum-dependent relaxation pathways of photoexcited carriers, enabling us to disentangle transient valence band renormalization from the emergence of a pronounced surface photovoltage (SPV) induced by optical excitation.

Results

Electronic structure and sample characterization

The crystallographic structure of PdSe2 is shown in Fig. 1a. In its most stable configuration, PdSe2 adopts an orthorhombic crystal structure, classified under the Pbca space group (No. 61), with lattice parameters: a = 5.741 Å, b = 5.806 Å, and c = 7.691 Å, determined via X-ray diffraction58. The bulk unit cell consists of two PdSe2 layers separated by a van der Waals gap, while each monolayer has a thickness of 5.2 Å7,59. In the top-view projection, the monolayer forms a puckered network of non-hexagonal rings similar to the corrugated layered structure of BP6, as depicted in Fig. 1a. Structurally, it comprises three atomic subplanes, with Pd atoms centrally positioned and covalently bonded to four Se atoms in the upper and lower subplanes7.

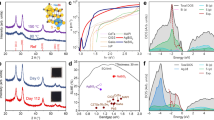

a Top and side views of the PdSe2 crystal structure (upper part), along with a 3D representation of the Brillouin zone showing high-symmetry points. The lower-right part illustrates the corrugated layer structure of PdSe2. b k-resolved density of states (DOS) calculated using density functional theory (DFT) along high-symmetry paths in reciprocal space. Red squares and dots highlight the upper valence band and lower conduction band positions. c Raman spectrum of bulk PdSe2 measured at room temperature using 532 nm excitation, with the polarization of the incident light parallel to the a-axis (lower panel) and to the b-axis (upper panel).

Based on theoretical calculations, we focus on the Γ-S direction, where the band dispersion is maximal. This direction enables us to probe the VBM and CBM (red dots in Fig. 1b), consistent with other first-principles DFT calculations and prior experimental results35,36.

The samples were initially characterized by Raman spectroscopy using 532 nm excitation. To prevent potential sample damage, the laser power was maintained below 200 μW, with a spot size of 20 μm. To eliminate surface oxidation, samples were cleaved via micromechanical cleavage using adhesive tape prior to measurement. Raman experiments were performed in a parallel geometry with the incident and scattered lights polarized along both the a-axis or the b-axis, as shown in the lower and upper panels of Fig. 1c, respectively. The Raman spectra of PdSe2, shown in Fig. 1c, reveal six major peaks corresponding to in-plane and out-of-plane Ag and B1g vibrational modes. Specifically, the Ag-symmetry modes are observed at 147.7, 209.4, and 260.6 cm−1, while the B1g-symmetry modes are found at 149.5, 225.9, and 271.5 cm−1. Based on the strong in-plane anisotropy, the sample crystal was aligned along either the a-axis or b-axis, as shown in Fig. 1c. The observed Raman modes and their relative intensities are consistent with those reported for bulk PdSe2 in the literature7,22.

Determination of the indirect bandgap

For TR-ARPES measurements on PdSe2, the sample was oriented along the Γ − S high-symmetry direction (see Fig. 1b) to enable simultaneous detection of the VBM and CBM within a single acquisition. Figure 2a presents a TR-ARPES map of bulk PdSe2, as acquired along the Γ − S direction with 10.8 eV probe photon energy, following excitation by a pump pulse of 1.2 eV photon energy with a duration of 300 fs. This map was obtained by subtracting the photoemission spectrum recorded before pump arrival from the spectrum at a 1 ps pump-probe delay. Dark brown regions represent photo-induced increase in spectral weight, while dark turquoise indicates spectral weight depletion.

a Differential ARPES map of PdSe2 along the \({\Gamma }^{{\prime} }\)-S\({}^{{\prime} }\) direction at a pump-probe delay of 1 ps, showing conduction band (CB) population. Dark brown indicates enhancement, while dark turquoise represents depletion. The CBM and VBM are observed simultaneously, and the black dashed lines serve as guides to the eye for the band dispersions. Vertical red and blue dashed lines mark the energy cuts at the VB and CB, respectively. b DFT calculations for the highest VB and lowest CB along the Γ-S axis at kz = 0 (brown bands) and along \({\Gamma }^{{\prime} }\)-S\({}^{{\prime} }\) at kz = 0.165 plane (green bands) across the BZ (for details see the text). This figure demonstrates the strong kz dependence as the band gap changes from 0.45 eV up to 0.66 eV for kz = 0 and kz = 0.165, respectively. The grey shaded region indicates the energy range of defect-induced states obtained from DFT calculations (see Supplementary Information). c EDCs of the VB (red) and CB (blue), extracted along the corresponding dashed lines in (a) with an integration width of 0.04 Å−1 from the absolute intensity of the TR-ARPES signal. The EDC intensity corresponding to the CB has been multiplied by a factor of 15. The bandgap at this kz point is approximately 0.80 eV (from the VB peak to the CB peak), whereas the indirect band gap of PdSe2 is calculated to be 0.55 eV; for details, see the main text.

For comparison, Fig. 2b schematically shows where the CBM is estimated to be near the Brillouin zone corner. The band dispersion, shown in Fig. 2a, simultaneously reveals the VBM and CBM, directly confirming the indirect band gap of bulk PdSe2. At 1 ps, the TR-ARPES spectrum exhibits clear optical excitation across the band gap, leading to electron population in the CB. The VBM is located at the Γ-point. The VB exhibits a pronounced response at 1 ps, with intensity depletion below and enhancement above the VBM, which will be discussed later. The CBM is observed 0.54 eV above the Fermi level in the corresponding constant energy map, slightly away from the Brillouin zone corners, in good agreement with our DFT results shown in Fig. 1b.

The energy distribution curves (EDCs) of the VB and CB were extracted from the corresponding red and blue dashed lines at the Γ-point and at 0.65 Å−1, with an integration width of 0.04 Å−1, shown in Fig. 2c. We used a fitting method combining a Shirley-Sherwood, slope and baseline components to subtract the inelastic background. The resulting spectra enabled accurate extraction of the valence band peak and energy gap (see Supplementary Information for further details). The VBM is located at − 0.26 eV below the Fermi level at the Γ-point. We note that the probe photon energy in our photoemission experiment does not access the Γ-S plane at kz = 0, where the indirect band gap reaches its minimum, but instead probes finite out-of-plane momenta corresponding to the \({\Gamma }^{{\prime} }\)-S\({}^{{\prime} }\) plane (see Fig. 2a). To determine the indirect band gap of PdSe2, we combine TR-ARPES measurements with the relative kz-dependent dispersion trends from DFT. Our TR-ARPES experiment utilized a probe photon energy of 10.80 eV. Based on the known periodicity of Γ → Z → Γ features observed in photon-energy-dependent ARPES36, the chosen probe photon energy of TRARPES selects an out-of-plane momentum estimated as kz = 0.162 on a normalized scale where kz = 0 represents the Γ point and kz = 0.5 represents the Z point. We measured the band gap experimentally at this kz value as 0.80 eV (i.e., between \({\Gamma }^{{\prime} }\) and S\({}^{{\prime} }\), corresponding to the symmetry points at kz = 0.162 plane). While DFT may not yield the precise absolute band gap, it accurately models the relative variation of the gap along kz. Therefore, we used the DFT-calculated dispersion trend to extrapolate our experimental value from kz = 0.162 back to the Γ point (kz = 0). This procedure yields an estimated indirect band gap at Γ of 0.55 eV. This value is grounded in the experimental measurement and relies only on the relative kz dispersion predicted by DFT (see Supplementary Information for details).

Photoinduced band dynamics

Figure 3 a displays the differential photoemission intensity near the \({\Gamma }^{{\prime} }\) point, obtained by subtracting spectra measured before pump excitation (τ < 0 ps) from those measured after (τ > 0 ps). This map reveals transient changes, including intensity increases and decreases, around the VBM. Several processes can influence the VB lineshape after excitation, such as BGR and SPV (affecting energy position), spectral depletion (reducing intensity), and increased carrier scattering (causing band broadening). To quantify these transient modifications, we analyze the photoemission intensity dynamics at different energies. We assume that these processes modify the measured lineshape of the VB EDC. Each process evolves with a characteristic timescale and influences the VB dynamics, but can affect distinct energy regions of the VB differently, leading to varying increases or decreases in the photoemission intensity across the spectrum. To disentangle these contributions and track the VB dynamics, the differential signal (Fig. 3a) is integrated over three representative energy regions below EF (dotted boxes, ~30 meV width). This procedure yields the temporal traces shown in Fig. 3b. To model these temporal traces, we employ a function incorporating three contributions characterized by distinct timescales, attributed to BGR, Depletion (Dep), and SPV processes. Using this simple set of assumptions, we are able to successfully reproduce the spectral weight dynamics of the VB. The time-dependent photoemission intensity PI(n)(t) in the nth energy region is given by:

where A(n) denotes the amplitude of each component in the nth energy region, and τr, τd represent the rise and decay time constants, respectively. The function \({\mathcal{H}}(t)\) is the Heaviside step function, and \({\mathcal{R}}(t)\) accounts for the Gaussian instrument response. A key assumption is that all regions share the same time constants (τr, τd) for each process, while the amplitudes (A(n)) vary with energy. The extracted timescale values from fitting are summarized in Fig. 3c: BGR rise time \({\tau }_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{BGR}}}\) is limited by time resolution; decay time \({\tau }_{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{BGR}}}=0.68\pm 0.35\) ps; depletion rise \({\tau }_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{Dep}}}=0.62\pm 0.41\) ps; depletion decay \({\tau }_{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{Dep}}}=2.76\pm 0.77\) ps; and a long-lived SPV decay \({\tau }_{{\rm{d}}}^{{\rm{SPV}}}=59.75\pm 12.73\) ps (additional discussion is provided in the Supplementary Information).

a Differential ARPES map at the \({\Gamma }^{{\prime} }\) point shows transient VB evolution after photoexcitation. b Pump-probe traces or the difference in photoemission (PE) intensity at selected energy regions (1-3), each integrated over a 30 meV window, highlight distinct dynamical behaviors. The error bars scale with the fitting uncertainty. c Multi-exponential fit reveals components attributed to band gap renormalization, depletion (Dep), and SPV, with shared time constants. d Differential ARPES at ~0.65 Å−1 shows CB electron population and below-EF depletion. e The dynamics of the conduction band minimum (region 4) and the depletion region (region 5), integrated over energy widths of 300 and 130 meV, respectively, exhibit asymmetric behavior and delayed hole trapping. f Comparative rise times indicate ultrafast VB broadening, CB rise ~0.3 ps, and delayed hole depletion (~1 ps), represented by the black and brown arrows, respectively.

Figure 3d presents the temporal evolution of the ARPES intensity at 0.65 Å−1, corresponding to the momentum of the CBM (blue dashed line in Fig. 2a). The differential map reveals an increase in spectral intensity following optical excitation, indicating the accumulation of electrons at the CBM. Interestingly, a reduction in photoemission intensity is seen below EF, yet both static ARPES measurements and DFT calculations do not predict any states at this energy and momentum. Figure 3e shows the dynamics of the energy regions above and below EF, corresponding to dashed boxes 4 and 5 in Fig. 3d. After an initial fast decay of approximately 0.8 ps, attributed to intraband thermalization and scattering processes, the CBM exhibits negligible further dynamics and remains populated over long timescales. In contrast, the depletion observed in region 5 follows a distinct dynamical behavior compared to the VBM at the \({\Gamma }^{{\prime} }\)-S\({}^{{\prime} }\) point as it exhibits a delayed rise and a significantly slower recovery, persisting for more than 6 ps. This indicates that region 5 is not associated with the intrinsic valence band dynamics but rather reflects a separate relaxation channel. This behavior is inconsistent with strong secondary electron contributions, which are generated almost instantaneously through inelastic scattering and lack both temporal structure and energy selectivity. The distinct delay in the signal onset (see the arrow in Fig. 3f), its localized energy character (region 5), and its picosecond dynamics collectively support an interpretation based on hole trapping into mid-gap states introduced by intrinsic defects.

Figure 3 f compares the rise times of BGR (\({\tau }_{{\rm{r}}}^{{\rm{BGR}}}\)) with those of the CB and the depletion in region 5. The ~ 0.3 ps delay in CB rise reflects intraband and interband scattering processes, whereas the depletion emerges only after ~1 ps, supporting a scenario of defect-assisted carrier trapping. Our DFT calculations, together with the observed violation of the selection rules in Raman spectra, support the presence of such defect states (for details, see Supplementary Information). The role of these mid-gap states in generating a long-lived SPV is further discussed in the next section. Such defect-induced states, most likely native Se or Pd vacancy states that lie within the band gap, are generally weakly dispersive and localized in real space. They may not be detectable using static ARPES due to their low cross-section and occupation. However, following photoexcitation, hole redistribution, matrix element changes, or enhanced spectral weight due to altered band renormalization can reveal their presence. This differential analysis, comparing pumped and unpumped spectra, isolates the transient pump-induced dynamics by suppressing the static background, thereby enhancing their detectability. The timescales of trapping dynamics are in line with observations across various 2D TMDCs (e.g., MoS2, WS2), where this phenomenon is attributed to phonon-assisted trapping or defect capture of the Auger type60.

Surface photovoltage and transient band Renormalization

Figure 4 reveals the emergence and evolution of SPV in PdSe2, in agreement with previous studies on other materials44,45,51,52,53,54. Figure 4a shows the VB dispersion for three pump fluences measured 1 ps before the pump pulse arrival (τ0). As the pump fluence increases, the entire VB shifts rigidly toward higher binding energies. This systematic shift is a hallmark of SPV formation: photoexcited electron-hole pairs screen the equilibrium surface band bending by partially neutralizing the space-charge field, thereby raising the local vacuum level and shifting the entire band structure to higher binding energy in the photoemission spectrum44,45. Figure 4b presents the corresponding EDCs of the VB, showing a rigid shift without significant broadening upon increasing pump fluence. This confirms that the shift is electrostatic in origin and not due to heating or lifetime effects. The fluence-dependent energy shift directly reflects the transient flattening of the band bending potential via SPV. Figure 4c sketches the band alignment before and after pump excitation. In equilibrium, intrinsic defects generate upward band bending at the surface. The arrival of the pump pulse creates a population of carriers in the near-surface region, which screen the built-in field and reduce the band bending by an amount ΦSPV; this manifests as a transient, rigid shift of both the VB and core levels toward higher binding energy51,52.

a ARPES maps at three different pump fluences and a negative pump-probe delay ~−1 ps, along with a differential ARPES map at high pump fluence, highlighting the negative shift of the top of the VB. b EDCs (bullets) and their fits (solid lines) near the top of the valence band, integrated around ~0.1 Å−1, for five different excitation powers, showing a clear band shift with increasing intensity. The shift of the spectra is the result of SPV. Interpretation of the positive- and negative-delay dynamics in VB. c The upper inset illustrates the valence and Fermi bands of the bulk and at the surface. The dashed red line represents the band bending potential, ΦSPV (surface photo-voltage). The lower inset in this panel sketches the expected ARPES spectrum. d A comparison of the event sequences. The black lines perpendicular to the sample surface represent the SPV-induced electric field. e SPV versus pump fluence. Experimental data (black marks) were fitted by the test function Eq.(2) (solid red line).

Figure 4 d illustrates the event sequence from negative to positive delay configurations. For positive delays, the pump pulse initially induces the SPV and the corresponding electric field. This field influences the propagating photoelectrons, as shown in the green shaded region. The electric field decays exponentially, after which the electrons are no longer affected by the SPV. The sketch explains why a SPV effect is also observed at negative delays. The probe pulse arrives before the pump, ejecting electrons in the unperturbed band structure. For negative delays (τ < 0 ps), the electron is photoemitted before the pump pulse reaches the sample. However, while the electron propagates away from the surface, the pump pulse arrives and generates a transient SPV by spatially separating photocarriers within the near-surface depletion region. This separation creates a macroscopic dipole layer whose associated electric field extends into the vacuum. As the emitted electron continues its flight, it enters this evolving field and experiences an acceleration, gaining additional kinetic energy. The energy gain ΔEkin(d) depends on the local dipole potential at the electron’s distance Ze = ve∣τ∣ from the surface, ΔEkin(d) = eϕ(d) where ϕ(d) is the potential created by the dipole field. To model this, prior works51,52,54 use a disk-shaped dipole layer of radius R, representing the illuminated pump region. The potential at a point along the axis perpendicular to the disk (i.e., along the photoelectron path) is given by, \(\phi (d)={\phi }_{0}\left(1-\frac{d}{\sqrt{{d}^{2}+{R}^{2}}}\right)\). At long negative delays, this effect disappears, as we measure no difference between the unpumped spectrum and the spectrum at delay − 200 ps, consistent with the absence of a SPV. Figure 4e shows the extracted SPV potential ΦSPV as a function of pump fluence. The maximum SPV shift is approximately 67 meV, yielding a surface defect density on the order of 1012-1013 cm−2 (see Supplementary Information for estimation details). The data follow a phenomenological logarithmic saturation trend, described by:

where α = 20.8 meV and ρ0 = 63.38 × 10−3 cm2/mJ are the fitting parameters. This trend indicates that SPV generation saturates at higher fluences, consistent with carrier screening and depletion-layer filling effects in semiconductors44,53. Therefore, our results confirm that PdSe2 exhibits a robust SPV response under ultrafast photoexcitation. This effect is attributed to intrinsic defect states near the surface, facilitating long-lived charge separation. Our DFT calculations (see Supplementary Information) align with theoretical studies indicate that selenium vacancies in PdSe2 are mobile and can migrate towards the surface, forming localized in-gap states56. Given their propensity to be negatively charged, these surface vacancies are expected to create an initial upward band bending. Therefore, the most plausible mechanism consistent with our observations is that upon photoexcitation, the trapping of photogenerated holes by these states partially neutralizes the surface charge. This leads to a flattening of the band bending, which manifests as the observed SPV.

We finally focus on the analysis of the transient spectral lineshapes to derive the potential VB energy shift and broadening after photoexcitation. In Fig. 5a, the solid lines depict Gaussian fits to the background-subtracted EDCs at delays of − 1 ps and 0.5 ps, allowing for accurate determination of variations in linewidth and central energy (see SI for more information). Therefore, one can determine the photo-driven VB dynamics, showing modest VB broadening of 22 meV and an energy shift of approximately 15 meV, which we attribute to BGR and increased carrier scattering.

a VB energy distribution curves at −1 ps and 0.5 ps delays (black and red dots). The solid lines show background-subtracted spectra fitted with Gaussian profiles, revealing a valence band shift and broadening indication of band gap renormalization. b Schematic of carrier redistribution after photoexcitation with a 1.2 eV pump: the top VB is directly excited, and electrons reach the CBM in about 300 fs. Holes are transferred to localized surface defect states, triggering the SPV process.

Discussion

Figure 5b schematically illustrates the underlying mechanism: upon 1.2 eV excitation, electrons are promoted from the VB to the CBs, where they thermalize to the CBM within ~300 fs. The photogenerated holes are trapped in localized surface defect states, resulting in spatial charge separation, flattening of the band bending and the formation of a transient electric field responsible for the SPV. This separation generates a macroscopic dipole layer, which modifies the kinetic energy of photoelectrons depending on the pump-probe delay. These findings confirm that photoexcitation of carriers results in ultrafast BGR and broadening. Further studies may help clarify whether the observed effects are related to the Stark effect reported in BP46.

Our study unveils the ultrafast photoinduced charge dynamics in semiconducting PdSe2, revealing a rich interplay between transient band dynamics and SPV formation. Time-resolved ARPES measurements directly capture the population of conduction band states and renormalization of the valence band within sub-picosecond timescales. These effects are accompanied by a pronounced, long-lived surface photovoltage, driven by defect-assisted hole trapping and macroscopic dipole layer formation. The indirect band gap is determined to be 0.55 eV. From a detailed investigation of the TR-ARPES results, we disentangle the contributions of BGR and band broadening. The SPV shift in PdSe2 exceeds 67 meV. The combination of air-stable low-symmetry structure, strong many-body effects, and defect-mediated surface fields positions PdSe2 as a compelling platform for light-tunable carrier separation and ultrafast surface potential engineering. These features may open pathways for developing high-speed optoelectronic switches and photogated transistors leveraging surface charge dynamics. Crucially, the demonstrated influence of native vacancies in shaping mid-gap state dynamics and enabling long-lived SPV underscores the pivotal role of intrinsic defect landscapes in governing the nonequilibrium electronic responses of quantum materials.

Methods

Time-resolved and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy

Bulk PdSe2 samples were obtained from HQ Graphene61. Prior to TR-ARPES measurements, the samples were cleaved in situ at room temperature in ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) conditions, with a pressure better than ~ 2× 10−10 mbar. The orientation of the sample was determined by low-energy electron diffraction (LEED). TR-ARPES measurements were conducted at the T-ReX laboratory operated by the Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste, S.C.p.A., using the setup described in ref. 62, based on a 200 kHz Coherent Monaco laser system. The output centered at 1.2 eV was used as the pump. The ninth harmonics (10.8 eV) of the laser were used as the pobe and were p-polarized. The pump fluence was tunable, and a variable delay (τ) was applied to the sample relative to the probe pulse. The pump and probe beams were focused to spot sizes of approximately 300 μm and 200 μ,m respectively, and impinged on the sample surface at a 30-degree angle. The experimental time, energy, and angular resolutions were better than 800 fs, 50 meV, and 0.1 degrees, respectively.

The sample temperature was maintained at ~100 K during the measurements. The photoemitted electrons were detected by a hemispherical analyzer, with an acceptance angle of ±15°.

Density Functional Theory

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the band structure were carried out using the plane wave DFT code Quantum Espresso63,64. In the DFT calculations presented in Fig. 1b, ultrasoft pseudopotentials with the PBE exchange-correlation functional65 were used with a kinetic energy cutoff of 680 eV and a Monkhorst-Pack66k-point density of 8 × 8 × 6 for the primitive unit cell. The structures were relaxed to achieve forces of order 10−3 eV Å−1 and pressures less than ±0.2 kbar. Results were compared to (i) calculations using the regularized SCAN meta-GGA exchange-correlation functional67 along with the rVV10 kernel for the inclusion of van der Waals forces between layers68 and to (ii) Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof hybrid functional69 calculations with the use of Wannier9070 for interpolation. The trends of the band edge positions at the \({\Gamma }^{{\prime} }\) and S\({}^{{\prime} }\) points as a function of kz were found to be similar across all levels of theory.

Data availability

The TR-ARPES data that support the findings of this study are openly available in https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17542171. The DFT calculations were performed using the open-source Quantum Espresso package. No custom code was developed for this work.

References

Manzeli, S., Ovchinnikov, D., Pasquier, D., Yazyev, O. V. & Kis, A. 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 1–15 (2017).

Kumar, V. P., Raut, P., Panda, D. K. & Rashed, A. N. Z. Exploring next-generation tmdc materials: A comprehensive review of their classifications, properties, and applications. Silicon 1–23 (2025).

Setayeshmehr, K., Hashemi, M. & Ansari, N. Photoconversion efficiency in atomically thin tmdc-based heterostructures. Opt. Express 29, 32910–32921 (2021).

Schneider, C., Glazov, M. M., Korn, T., Höfling, S. & Urbaszek, B. Two-dimensional semiconductors in the regime of strong light-matter coupling. Nat. Commun. 9, 2695 (2018).

Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Photonics and optoelectronics of 2D semiconductor transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Photonics 10, 216–226 (2016).

Samy, O., Zeng, S., Birowosuto, M. D. & El Moutaouakil, A. A review on MoS2 properties, synthesis, sensing applications and challenges. Crystals 11, 355 (2021).

Oyedele, A. D. et al. PdSe2: pentagonal two-dimensional layers with high air stability for electronics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 14090–14097 (2017).

Xia, F., Wang, H. & Jia, Y. Rediscovering black phosphorus as an anisotropic layered material for optoelectronics and electronics. Nat. Commun. 5, 4458 (2014).

Morita, A. Semiconducting black phosphorus. Appl. Phys. A 39, 227–242 (1986).

Sierra, J. F. et al. Room-temperature anisotropic in-plane spin dynamics in graphene induced by PdSe2 proximity. Nature Materials 1–7 (2025).

Long, M. et al. Palladium diselenide long-wavelength infrared photodetector with high sensitivity and stability. ACS Nano 13, 2511–2519 (2019).

Pi, L. et al. Recent progress on 2D noble-transition-metal dichalcogenides. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1904932 (2019).

Hassan, A., Guo, Y. & Wang, Q. Performance of the pentagonal PdSe2 sheet as a channel material in contact with metal surfaces and graphene. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2, 2535–2542 (2020).

Wu, D. et al. Highly polarization-sensitive, broadband, self-powered photodetector based on graphene PdSe2 germanium heterojunction. ACS Nano 13, 9907–9917 (2019).

Lan, Y.-S., Chen, X.-R., Hu, C.-E., Cheng, Y. & Chen, Q.-F. Penta-PdX2 (X=S, Se, Te) monolayers: promising anisotropic thermoelectric materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 11134–11142 (2019).

Zeng, L.-H. et al. Controlled synthesis of 2D palladium diselenide for sensitive photodetector applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806878 (2019).

Deng, S., Li, L. & Zhang, Y. Strain modulated electronic, mechanical, and optical properties of the monolayer PdS2, PdSe2, and PtSe2 for tunable devices. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 1, 1932–1939 (2018).

Gu, Y. et al. Two-dimensional palladium diselenide with strong in-plane optical anisotropy and high mobility grown by chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906238 (2020).

Liang, Q. et al. High-performance, room temperature, ultra-broadband photodetectors based on air-stable PdSe2. Adv. Mater. 31, 1807609 (2019).

Liu, M. et al. Uncooled near-to long-wave-infrared polarization-sensitive photodetectors based on MoSe2/PdSe2 van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 16, 2774 (2025).

Luo, W. et al. Anisotropic phonon response of few-layer PdSe2 under uniaxial strain. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2003215 (2020).

Abdul-Aziz, O. et al. Resonance-induced anomalies in temperature-dependent Raman scattering of PdSe2. J. Mater. Chem. C. 12, 11402–11411 (2024).

Liang, Q. et al. Performance improvement by ozone treatment of 2D PdSe2. ACS nano 14, 5668–5677 (2020).

Yu, J. et al. Direct observation of the linear dichroism transition in two-dimensional palladium diselenide. Nano Lett. 20, 1172–1182 (2020).

Zhu, R. et al. Observation of anisotropic magnetoresistance in layered nonmagnetic semiconducting PdSe2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 37527–37534 (2021).

Soulard, C. et al. Experimental and theoretical investigation on the relative stability of the PdS2-and pyrite-type structures of PdSe2. Inorg. Chem. 43, 1943–1949 (2004).

ElGhazali, M. A. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity up to 13.1 k in the pyrite phase of palladium diselenide PdSe2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 060509 (2017).

Nishiyama, W. et al. Is the bandgap of bulk PdSe2 located truly in the far-infrared region? determination by fourier-transform photocurrent spectroscopy. Adv. Photonics Res. 3, 2200231 (2022).

Nishiyama, W. et al. Quantitative determination of contradictory bandgap values of bulk PdSe2 from electrical transport properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2108061 (2022).

Sun, J., Shi, H., Siegrist, T. & Singh, D. J. Electronic, transport, and optical properties of bulk and mono-layer PdSe2. Appl. Phys. Lett.107 (2015).

Wei, M. et al. Layer-dependent optical and dielectric properties of centimeter-scale PdSe2 films grown by chemical vapor deposition. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 6, 1 (2022).

Zhao, X. et al. Electronic and optical properties of PdSe2 from monolayer to trilayer. Superlatt. Microstruct. 142, 106514 (2020).

Kuklin, A. V. & Ågren, H. Quasiparticle electronic structure and optical spectra of single-layer and bilayer PdSe2: Proximity and defect-induced band gap renormalization. Phys. Rev. B 99, 245114 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Phonon-assisted electronic states modulation of few-layer PdSe2 at terahertz frequencies. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 5, 87 (2021).

Cattelan, M., Sayers, C., Wolverson, D. & Carpene, E. Site-specific symmetry sensitivity of angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy in layered palladium diselenide. 2D Mater. 8, 045036 (2021).

Gu, C. et al. Low-lying electronic states with a giant linear dichroic ratio observed in PdSe2. Phys. Rev. B 106, L121110 (2022).

Chung, Y. et al. Dark states of electrons in a quantum system with two pairs of sublattices. Nat. Phys. 20, 1582–1588 (2024).

Ryu, J. H. et al. Direct observation of orbital driven strong interlayer coupling in puckered two-dimensional PdSe2. Small 18, 2106053 (2022).

Kim, J. et al. Observation of tunable band gap and anisotropic Dirac semimetal state in black phosphorus. Science 349, 723–726 (2015).

Shan, S. et al. Matrix element effect in layered PdSe2. J, Phys, Chem, C (2025).

Boschini, F., Zonno, M. & Damascelli, A. Time-resolved ARPES studies of quantum materials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 015003 (2024).

Aeschlimann, M. et al. Time-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy at surfaces. Surf. Sci. 753, 122631 (2025).

Hedayat, H. et al. Ultrafast evolution of bulk, surface and surface resonance states in photoexcited Bi2Te3. Sci. Rep. 11, 4924 (2021).

Hedayat, H. et al. Non-equilibrium band broadening, gap renormalization and band inversion in black phosphorus. 2D Mater. 8, 025020 (2021).

Kremer, G. et al. Ultrafast dynamics of the surface photovoltage in potassium-doped black phosphorus. Phys. Rev. B 104, 035125 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Band gap renormalization, carrier multiplication, and Stark broadening in photoexcited black phosphorus. Nano Lett. 19, 488–493 (2018).

Roth, S. et al. Photocarrier-induced band-gap renormalization and ultrafast charge dynamics in black phosphorus. 2D Mater. 6, 031001 (2019).

Gierster, L., Vempati, S. & Stähler, J. Ultrafast generation and decay of a surface metal. Nat. Commun. 12, 978 (2021).

Weinelt, M. et al. Electronic structure and electron dynamics at Si (100). Appl. Phys. A 80, 995–1003 (2005).

Weinelt, M., Kutschera, M., Fauster, T. & Rohlfing, M. Dynamics of exciton formation at the Si (100) c (4×2) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 126801 (2004).

Ciocys, S., Morimoto, T., Moore, J. & Lanzara, A. Tracking surface photovoltage dipole geometry in Bi2Se3 with time-resolved photoemission. J. Stat. Mech.: Theory Exp. 2019, 104008 (2019).

Yang, S.-L., Sobota, J. A., Kirchmann, P. S. & Shen, Z.-X. Electron propagation from a photo-excited surface: implications for time-resolved photoemission. Appl. Phys. A 116, 85–90 (2014).

Ulstrup, S. et al. Ramifications of optical pumping on the interpretation of time-resolved photoemission experiments on graphene. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 200, 340–346 (2015).

Ciocys, S. et al. Manipulating long-lived topological surface photovoltage in bulk-insulating topological insulators =Bi2Se3 and Bi2Te3. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 1–7 (2020).

Kuklin, A. V., Begunovich, L. V., Gao, L., Zhang, H. & Ågren, H. Point and complex defects in monolayer PdSe2: Evolution of electronic structure and emergence of magnetism. Phys. Rev. B 104, 134109 (2021).

Jena, T. et al. Evidence for intrinsic defects and nanopores as hotspots in 2D PdSe2 dendrites for plasmon-free sers substrate with a high enhancement factor. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 7, 8 (2023).

Nguyen, G. D. et al. 3d imaging and manipulation of subsurface selenium vacancies in PdSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 086101 (2018).

Grønvold, F. & Røst, E. The crystal structure of PdSe2 and PdS2. Acta Crystallogr. 10, 329–331 (1957).

Zhang, Y. et al. Quantum octets in high mobility pentagonal two-dimensional PdSe2. Nat. Commun. 15, 761 (2024).

Gao, L., Hu, Z., Lu, J., Liu, H. & Ni, Z. Defect-related dynamics of photoexcited carriers in 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 8222–8235 (2021).

HQ Graphene. Hq graphene official website. https://www.hqgraphene.com/ (2025). Accessed: 2025-03-28.

Peli, S. et al. Time-resolved vuv ARPES at 10.8 ev photon energy and MHz repetition rate. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 243, 146978 (2020).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Quantum espresso: a modular and open-source software project for quantumsimulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys.: Condens. matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

Bartók, A. P. & Yates, J. R. Regularized scan functional. The Journal of chemical physics150 (2019).

Sabatini, R., Gorni, T. & De Gironcoli, S. Nonlocal van der waals density functional made simple and efficient. Phys. Rev. B-Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 87, 041108 (2013).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. An updated version of wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximally-localised wannier functions. Computer Phys. Commun. 185, 2309–2310 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through project No. 277146847 - CRC 1238: Control and Dynamics of quantum Materials. Computational work was performed on the University of Bath’s High Performance Computing Facility and was supported by the EU Horizon 2020 OCRE/GEANT project “Cloud funding for research”. G.C. acknowledges financial support by the European Union’s NextGenerationEU Programme with the I-PHOQS Infrastructure [IR0000016, ID D2B8D520, CUP B53C22001750006] "Integrated infrastructure initiative in Photonic and Quantum Sciences". C.J.S. and G.C. acknowledge support from the Horizon Europe EIC Pathfinder Open program under grant agreement no. 101130384 (QUONDENSATE).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.A.A., M.T., W.B., F.C., C.J.S., E.C., and H.H. performed the experimental measurements. O.A.A. analyzed the data under the supervision of H.H. and P.v.L. D.W. performed the DFT calculations. All authors, O.A.A., M.T., W.B., F.P., F.C., D.W., C.J.S., G.C., C.D., E.C., P.v.L., and H.H. contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the results. The manuscript was written by O.A.A. and H.H. with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdul-Aziz, O., Tuniz, M., Bronsch, W. et al. Photoinduced electronic band dynamics and defect-mediated surface potential evolution in PdSe2. npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 110 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00629-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00629-2