Abstract

Efficient hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) detection is crucial for electrochemical and colorimetric sensors, making the hydrogen peroxide reduction reaction (HPRR) a key area of catalysis. In this context, molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) has emerged as a valuable HPRR catalyst. Here, we report the first experimental investigation comparing the electrocatalytic properties of MoS2 enriched with different phases (2H and 1T) and showcasing diverse morphologies toward HPRR. We provide unprecedented parameters (Tafel slope, constant, and exchange current density) describing the materials’ HPRR performance through state-of-the-art electrochemical techniques, including Tafel plots and EIS. Our findings reveal that 1T-enriched MoS2 outcompetes 2H-MoS2. Moreover, we show that the distinct morphologies of 1T-MoS2, such as exfoliated nanosheets and hydrothermally synthesized nanoflowers, strongly influence the kinetics of the catalytic reaction. This study bridges the gap between MoS2 structural properties and its electrocatalytic activity for HPRR, facilitating the selection of optimal MoS2 materials for high-sensitivity hydrogen peroxide sensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a critical redox metabolite in the human body, vital for physiological processes like redox regulation, signaling, and sensing1,2. Imbalances in H2O2 concentration have been associated with the progression of various health issues, including tumor metastasis3, neurodegenerative diseases4,5,6, and dermatologic issues7,8. Beyond its endogenous roles, H2O2 is also a byproduct of oxidoreductases, such as lactate oxidase and glucose oxidase1,9,10, which can be used to develop highly selective enzymatic biosensors11. Due to its significant involvement in various physiological and pathological processes, developing sensing devices for H2O2 remains a very active and important area of research12,13,14.

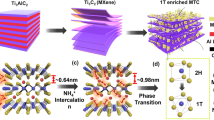

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) are a vast family of layered materials whose physical-chemical properties strongly depend on their crystalline phase15,16 and the number of layers17. 2D-MoS2 is a widely investigated TMDC that exists mainly in two distinct phases. The metastable 1T phase has an octahedral structure and metallic properties. The thermodynamically stable 2H phase possesses a hexagonal lattice and operates as a semiconductor with a direct band gap of 1.8 eV18,19. Due to the tunability of its chemical, physical, and electronic properties, MoS2 is a valid alternative to noble metals in electrocatalysis. Indeed, this material has been investigated for the electrocatalytic synthesis of green hydrogen (HER)20,21, and the nitrogen and oxygen reduction reaction (NRR and ORR)22,23.

MoS2 also exhibits peroxidase-like activity, making it a viable alternative to traditional H2O2 detection materials like platinum (Pt) and Prussian blue. It offers significant benefits, being more affordable than Pt and demonstrating greater stability at neutral and basic pH compared to Prussian blue. This combination of factors positions MoS2 as a promising, cost-effective, and robust material for developing advanced H2O2 sensing devices. Beyond MoS2, other TMDs exhibit notable electrocatalytic properties towards H2O2 reduction. For instance, Luo et al. reported that plasma-functionalized MoSe2 shows excellent electrocatalytic performance for the non-enzymatic detection of H2O2 across a wide pH range24. Similarly, Haritha et al. demonstrated that WS2 nanosheets function as an effective non-enzymatic electrocatalyst for H2O2 detection25.

In 2013, Wang et al. were the first to report the catalytic activity of ultrasmall nanoparticles of MoS2 toward HPRR26. The authors demonstrated that the exfoliated MoS2 nanoparticles immobilized on a glassy carbon electrode (GCE), allow the reduction of H2O2 at a potential of -0.5 V, with a size-dependent response. The following year, Lin et al. further studied the catalytic activity of colloidal MoS2 for the colorimetric detection of H2O2 based on 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB)27. In their study, they demonstrated that the catalyzed reaction follows a Michaelis-Menten kinetic and developed an enzymatic assay for glucose. A similar result was obtained in 2015 by Guo et al., who obtained a layered MoS2 by a bottom-up hydrothermal synthesis28. More recently, Haritha et al. described the synthesis and application of MoS2 microspheres for the precise electrochemical detection of H2O229. Using a hydrothermal approach, the authors fabricated a sensor operating in the micromolar range with good stability and reproducibility. MoS2-based materials have also been used to develop flexible electrodes applied in H2O2 detection in living cells30.

A common shortcoming in prior research is the insufficient consideration of MoS2 crystalline phase, a characteristic known to significantly impact its electrocatalytic activity, as evidenced in reactions like HER31,32,33. Conversely, data regarding its influence on HPRR are scarce (Table S1). Notably, Shu et al. are the sole researchers, to our knowledge, to explicitly mention the crystalline phase of MoS2 used in the sensor development (Table S1)34, stating that the 1T phase of interlayer-expanded MoS2 enhances the kinetics of H2O2 reduction, when compared to non-expanded MoS2.

Beyond Shu et al.‘s work, the current understanding of 1T and 2H MoS2 electrocatalytic mechanism for HPRR is primarily theoretical, derived from density functional theory (DFT) calculations. For instance, Gupta et al.35 used DFT to model MoS2-H2O2 interaction, revealing that the material’s catalytic activity originates from a distinct change in the electronic density of states of molybdenum atoms located at the edges. This altered electronic structure facilitates the preferred adsorption of H2O2 on the Mo atoms on the edges, leading to dissociation into 2 hydroxyl radicals (⋅OH). Later, Li et al.‘s DFT calculations suggested that 1T-MoS2, due to its unique electron-rich metallic phase, can lower the free energy barriers for the stepwise catalytic decomposition of H2O2, favoring ⋅OH production and enabling more energetically favorable pathways than its semiconducting 2H counterpart36.

Given the diverse synthetic approaches, morphologies, and crystalline structures of MoS2 (Table S1), a comparative study of its catalytic and electrocatalytic activity for HPRR is crucial for advancing its application in sensing. To address this gap, we present the first experimental comparison of MoS2’s electrocatalytic properties across different phases and morphologies for HPRR. We synthesized 1T-enriched MoS2 via both top-down (chemical exfoliation) and bottom-up (hydrothermal) methods, comparing their HPRR activity with 2H-MoS2. We also investigated the peroxidase-mimic activity of these 2D MoS2 materials using a TMB-based colorimetric assay. Crucially, for the first time, we employed state-of-the-art techniques, including Tafel plots and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), to quantitatively assess their HPRR catalytic performance, providing unprecedented parameters (Table S1). Our results reveal a dramatic influence of both crystalline phase and synthetic approach on MoS2 activity. Different synthesis methods yield 1T-MoS2 flakes with varying morphologies, leading to significant differences in catalytic activity and overall material applicability.

Results

Characterization of the different crystalline structures and morphologies of MoS2

To ensure the broadest significance and applicability of our findings, the 1T and 2H MoS2 used in this comparative study were synthesized using well-established and widely adopted procedures. 2H-MoS2 nanosheets were obtained by liquid-phase physical exfoliation of bulk MoS237. This procedure involves the ultrasonication of MoS2 in N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) and the subsequent isolation by centrifugation and resuspension in aqueous solution. Both top-down and bottom-up approaches were used to obtain 1T-enriched MoS2 with different morphologies. The top-down approach consisted of a chemical exfoliation involving the intercalation of Lithium ions and reduction of the bulk phase under an inert atmosphere, followed by ultrasonic exfoliation (E1T-MoS2)38. The bottom-up consisted of a hydrothermal synthesis (200 °C for 16 h) using MoO3 and C2H5NS as precursors (H1T-MoS2)39. In both cases, centrifugation and filtration of PTFE filters were used for the purification and isolation of final materials, with defined morphological features.

The MoS2 phases were confirmed by employing UV-Vis and Raman spectroscopies (Fig. 1a, b). Indeed, both the E1T and H1T-MoS2 show the characteristic absorption peaks of the 1T phase at 255 nm and 305 nm in the UV-Vis spectra40, and typical Raman modes J1 (154.6 and 151.2 cm−1), J2 (229.7 and 225.3 cm−1) and J3 (327.8 and 324.6 cm−1)41. Instead, the 2H MoS2 shows two distinctive bands at ca. 630 nm and 690 nm in the UV-Vis spectrum42, and the Raman peaks correlated to the modes E2g (in-plane vibration, at 377.4 cm−1) and A1g (out of plane vibration, at 404.2 cm−1)43. One more band at 180 cm−1 can be observed in the spectrum of H1T-MoS2, distinguishing it from E1T-MoS2. This band is associated with the vibration of LA(M) type phononic defects44, highlighting a more defective nature of H1T-MoS2 compared with E1T-MoS2, related to the nanoflower morphology. Finally, all the samples present a peak at 634 cm−1 in the Raman spectra that can be attributed to O-Mo-O vibrational modes of molybdenum oxides45,46.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of the Mo 3d core levels provided a quantitative assessment of the 1T and 2H phases in each MoS2 sample (Fig. S1). As expected from the literature37, for the ultrasonically exfoliated MoS2, the spectrum presents two main components at 229.5 eV and 232.6 eV, which are associated with the 2H crystalline phase, with no observable traces of the 1T phase. The chemically exfoliated MoS2 exhibited an enrichment in the metallic 1T phase (68.0%), as demonstrated by the appearance of two components at 227.8 eV and 231.0 eV, alongside a small percentage of 2H phase (20.9%). Similarly, hydrothermally synthesized MoS2 presented a mixed phase composition, enriched with 1T phase (1T = 60.1%, 2H = 31.1%). All prepared samples showed a minor percentage of molybdenum oxide (MoOx), ranging between 6% and 11%. (Table S2).

TEM micrographs highlight the different morphologies of the materials. 2H-MoS2 and E1T-MoS2 present large 2D flakes with respective average lateral size of 616 ± 285 nm and 874 ± 121 nm (Fig. 1c, d, Fig. S2a, b). The average thickness of the materials was determined by AFM and resulted in 1.31 ± 0.31 nm for 2H-MoS2 and 1.34 ± 0.28 nm for E1T-MoS2 (Fig. S3a, b, d, e). These values are consistent with a double layer of MoS247.

Instead, H1T-MoS2 (Fig. 1e) is characterized by a nanoflower structure with several jagged edges, characteristic of this synthesis34. The average size of the nanoflowers was determined to be 235 ± 53 nm (Fig. S2c). AFM micrographs revealed an elevated surface roughness, with height maxima of 5 nm (Fig. S3c, f).

MoS2 phase and morphology influence the self-generation of hydroxyl radicals

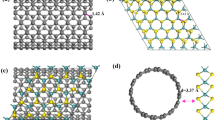

Our initial investigation focused on the catalytic activity of the synthesized MoS2 materials in solution and their ability to generate ⋅OH. Indeed, Li et al. demonstrated that the interaction between multi-layered flower-like MoS2 nanosheets and H2O2 induces the self-generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in solution36. Notably, these authors confirmed the formation of ⋅OH using electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy. The generation of this radical intermediate is crucial as it can play a fundamental role in the electrochemical reduction of H2O2 on a MoS2 surface, acting as a reactive intermediate of the reaction.

We compared the ability of the three MoS2 samples to produce ⋅OH radicals using a colorimetric 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) based assay. This method is a well-established technique for evaluating the peroxide-like activity of various nanomaterials, including platinum nanoparticles, which involves the generation of hydroxyl radicals. In this assay, the chromogenic substrate (TMB) reacts with the formed ⋅OH, producing a blue species that exhibits strong absorption at 652 nm48,49,50,51,52.

To evaluate their catalytic activity, the three MoS2 samples were incubated with varying H2O2 concentrations while maintaining a constant TMB concentration (1 mmol L−1). The resulting absorption was monitored over time (Figs. 2a–c, S4). The colorimetric assay revealed that both E1T-MoS2 and H1T-MoS2 effectively catalyze the formation of ⋅OH radicals, exhibiting fast reaction kinetics. In contrast, 2H-MoS2 showed negligible catalytic activity, failing to produce the chromogenic substrate (Figs. 2d, S5). These experimental findings are consistent with previous DFT calculations by Li et al.36, which predicted that the 1T phase significantly lowers the free energy barriers for the stepwise catalytic decomposition of H2O2 into reactive oxygen species (ROS) compared to the 2H phase.

All experiments were performed by incubating MoS2 samples ([MoS2] = 0.01 mmol L−1) and blank sample (ultrapure water) with 1 mmol L−1 of TMB and various concentrations of H2O2 in an acetate buffer 0.1 mol L−1. UV-Vis spectra of TMB registered over 45 min in the presence of 50 mmol L−1 H2O2, with 2H-MoS2 (a), H1T-MoS2 (b), E1T-MoS2 (c). d Photograph of the colorimetric assays in the presence of 50 mmol L−1 H2O2 after 30 min of incubation. e Reaction rates measured by UV-visible spectroscopy, in the first 300 s for all materials in the presence of different concentrations of H2O2; f) magnification of graph (e) in the region at lower H2O2 concentration.

Further analysis of the reaction kinetics showed that at low H2O2 concentrations, the absorbance profiles of E1T-MoS2 and H1T-MoS2 were not significantly different. However, at concentrations exceeding 10 mmol L−1, the reaction rate for E1T-MoS2 ceased to increase significantly, indicating saturation of the catalyst’s active sites (Fig. 2e, f). Notably, H1T-MoS2 did not reach saturation within the concentration range studied. Our experimental data align with DFT calculations by Gupta et al.35, which proposed that hydroxyl radical formation is favored at the Mo atoms on the edges of MoS2 where H2O2 molecules are adsorbed, and the O-O bond undergoes homolytic cleavage. The superior catalytic activity of H1T-MoS2 compared to E1T-MoS2 can thus be attributed to its flower-like, edge-rich structure, which provides a higher density of catalytic sites.

Evaluation of the electrocatalytic activity and dose-dependent response in chronoamperometry

The electrocatalytic activity of the materials toward the H2O2 reduction was assessed in the first instance by cyclic voltammetry (CV). For each sample, we deposited an optimal mass of material (5 µg) on a GCE electrode. This was achieved using the highest concentration at which the three materials are colloidally stable (0.5 mg mL−1) and the maximum volume that could be deposited on the GCE in a single drop cast (10 µL). Indeed, in our experience, depositing more layers of materials leads to poor homogeneity and reproducibility in the deposition. The electrochemical surface area (ECSA) was estimated by electrochemical capacitance measurements53. Analyzing the values reported in Table S3, it is possible to notice that all modified electrodes exhibited a significantly increased ECSA compared to the bare electrode, indicating that the modifications enhanced the electroactive surface. Furthermore, the H1T-MoS2 sample shows an ECSA approximately 2.5 times larger than its exfoliated counterpart (E1T-MoS2), which is consistent with its distinct flower-like morphology.

CVs were registered in the absence and the presence of 8 mmol L−1 of H2O2, scanning the potential between −0.8 and 0.2 V in 0.1 mol L−1 PBS and 0.1 mol L−1 KCl solutions purged from oxygen. Both H1T-MoS2 and E1T-MoS2 exhibit outstanding electrocatalytic performance with evident anticipation of the H2O2 reduction peak (maxima −0.298 V for E1T-MoS2 and −0.276 V for H1T-MoS2) (Fig. 3a). The comparison with the recorded voltammogram for 2H-MoS2 demonstrates the dramatic impact of the MoS2 crystalline phase on the catalytic properties of the material. Notably, the H2O2 reduction potentials registered with 1T-enriched MoS2 samples are close to those registered with a bulk platinum electrode under the same conditions (Fig. S6), making this material a cost-effective alternative to the state-of-the-art catalyst for this reaction. When the currents measured for both H1T-MoS2 and E1T-MoS2 are normalized by their respective ECSA (Fig. S6), the exfoliated material demonstrates a higher current density, highlighting its superior electrocatalytic activity. However, the current density of Pt remains higher than that of both MoS2 samples. (−215 mV and −0.964 mA cm−2; Fig. S6), This is probably due to the higher conductivity of the material and to the fact that all the Pt atoms participate in the reaction, providing more catalytically active sites compared to MoS2.

To evaluate the MoS2 applicability in electrochemical sensing, the dose-dependent response of the three materials was assessed by recording chronoamperometries in the presence of different concentrations of H2O2 (Figs. 3b, S7). The calibration lines obtained from E1T-MoS2 and H1T-MoS2 show a linear range between 0.5–8 mmol L−1 and sensitivities 54 times higher than 2H-MoS2. Using the E1T-MoS2 allowed us to achieve detection limits of 40 µM: 14 times lower than the 2H phase. The calibration lines were performed in triplicate, polishing the GCE and depositing a fresh sample of MoS2 on the electrode. We registered a small percentage relative standard deviation on the sensitivity (8.7%), demonstrating good reproducibility. The concentrations were tested in random order, and no memory effect was observed, demonstrating the stability of the material through the analysis.

Study of electrocatalytic activity and charge-transfer efficiency through Tafel analysis and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

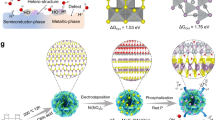

To investigate the origins of the observed electrocatalytic properties and to better understand the differing performance between H1T-MoS2 and E1T-MoS2, we conducted linear polarization experiments. The resulting Tafel plots are displayed in Fig. 4a, b for each modified electrode.

Polarization curves (a) and Tafel plots (b) were obtained from linear sweep voltammetry (recorded in PBS 0.1 mol L−1, KCl 0.1 mol L−1at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1) in the presence of H2O2 5 mmol L−1. c Radar chart resuming the values of electrocatalytic descriptors (Tafel slope, Tafel constant, exchange current density, and onset potential) for the three materials. d Nyquist plot of impedance spectra recorded in 5 mmol L−1 solution of [FeCN6]3-/[FeCN6]4- on the bare and modified GCE; Nyquist plot of impedance spectra recorded in 5 mmol L−1 solution of H2O2 on the GCE modified with E1T-MoS2 and H1T-MoS2, at OCP (e) and −0.3 V (f).

In agreement with what was observed in CV, the samples of MoS2 enriched with 1T phase are catalytically more active than the 2H phase, as the onset potentials for E1T-MoS2 and H1T-MoS2 (0.185 V and 0.113 V, respectively) are less negative compared with the 2H-MoS2 onset potential (−0.232 V) (Fig. 4a).

The Tafel plots for the reduction process were obtained by plotting the overpotential (η) versus the decimal logarithm of the registered current, in the linear region of the cathodic branch of the polarization curves (Fig. 4b). Tafel Eq. (1) expresses the correlation between the logarithm of the current and η:

Where b is the Tafel slope, j is the current density (calculated on the geometric surface area of the electrode), and c is a constant directly proportional to the logarithm of the exchange current density (\(c=b\,{\log }_{10}({j}_{0})\))54,55. From Eq. (1) it is possible to extract three important parameters to evaluate the catalytic efficiency of a material (Fig. S8, Table S4). The first one is the Tafel slope: a lower value of |b| is typically associated with better electrocatalytic performance, as lower overpotentials are required to perform the reaction55. The second is the Tafel constant, which coincides with the value of η when j = 1, \({\eta }_{j=1}=-b\,{\log }_{10}({j}_{0})\). This parameter represents the overpotential that must be applied to deliver one unit of current density: lower values of ηj=1 indicate better catalytic efficiency56. Finally, the exchange current density (j0), is a kinetic parameter quantifying the electrode’s readiness to proceed with the electrochemical reaction. The higher the exchange current, the faster the kinetics of the catalytic reaction57.

Figure 4c reports a radar chart comparing the Tafel slope, Tafel constant, exchange current density, and onset potential for the three materials and the bare GCE. E1T-MoS2 stands out as the most efficient electrocatalyst, as it presents the lowest values of Tafel slope (−226 mV dec−1) and Tafel constant (−1.258 V), and a more positive onset potential (0.185 V). H1T-MoS2 has a similar onset potential (0.113 V), but a higher Tafel slope (−303 mV dec−1) and Tafel constant (−1.457 V). On the other hand, the values of the Tafel slope (−378 mV dec−1) and Tafel constant (−1.927 V) for 2H-MoS2 point to moderate electrocatalytic activity.

Further insights can be obtained if we compare the exchange current densities (j0) of E1T-MoS2 and H1T-MoS2. Interestingly, H1T-MoS2 presents a value of exchange current density higher by one order of magnitude when compared with E1T-MoS2. This difference can be attributed to the different morphology of the two 1T-MoS2. Indeed, it has been previously reported that in the case of HER, the exchange current density is linearly proportional to the edge length of MoS2, suggesting that the edge sites of MoS2 are more active for HER electrocatalysis58. The elevated j0 and the fast generation rate of ⋅OH radicals (Fig. 2e) registered for H1T-MoS2 nanoflowers, point to a similar behavior for HPRR. Once again, the experimental evidence supports the DFT calculation form by Gupta et al.35, which predicts that the preferred O-O Cleavage active sites are the Mo atoms at the edges of MoS2.

Two further parameters fundamental for an effective electrocatalyst are the conductivity and the efficiency of the charge transfer. We investigated these aspects by performing electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in the presence of an electrochemical reversible probe such as [Fe(CN)6]3-/[Fe(CN)6]4- at the open circuit potential (OCP) (Fig. S9–S13). In the first instance, it can be observed how the modification with all the MoS2 samples induces a reduction of the resistance to the charge transfer (RCT) compared to the bare electrode (Fig. 4d, Table S5). As expected, the electrode modified with 1T-MoS2 outperforms the 2H-MoS2-modified electrode, due to the metallic properties of the former. In particular, E1T-MoS2 presents such a low RCT that the mass diffusion (Warburg component) becomes preponderant already at high frequencies. This means that E1T-MoS2 in the presence of [Fe(CN)6]3-/[Fe(CN)6]4- is characterized by fast charge transfer and high conductivity, which can be attributed to its planar and less defective structure.

Subsequently, EIS measurements were carried out in the presence of 5 mmol L-1 solutions of H2O2, at low and high overpotentials, to study the charge transfer during the HPRR (Fig. S14, S15). At low potentials (OCP, 0.15 V), the H1T-MoS2 presents a lower resistance to the charge transfer (RCT = 9.21 kΩ) compared to E1T-MoS2 (RCT = 18.00 kΩ) (Fig. 4e; Table S6). This observation is in accordance with the j0 values extracted from the Tafel plot: at low overpotentials, H1T-MoS2 presents faster reaction kinetics and therefore faster charge transfer.

On the other hand, E1T-MoS2 shows a marked dependence on the applied overpotential: the RCT values for this material decrease more rapidly when higher overpotentials are applied. Indeed, at the maximum reaction rate potential (−0.3 V) the behavior is reverted, and E1T-MoS2 shows a lower value of RCT (1.31 kΩ) than H1T-MoS2 (4.27 kΩ) (Fig. 4f; Table S6).

The value of Rct at low overpotential can be correlated to j0 by Eq. (2)59:

Where R is the ideal gas constant (8.31 J mol−1 K−1), T is the temperature (298 K), n is the number of electrons involved in the reaction, F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C mol−1), A is the surface of the electrode (0.19635 cm2).

The values of j derived from Eq. 2 for n = 1 are comparable with the values of j0 obtained from Tafel analysis (7.26 × 10−6 A cm−2 for E1T-MoS2 and 1.4 × 10-5 for A cm−2 H1T-MoS2).

This equality suggests that the reduction process proceeds through the one-electron transfer from the MoS2 to the ⋅OH, which is spontaneously generated from the interaction between the MoS2 and H2O2.

Discussion

All the experimental evidence reported in this work supports the previously published DFT simulation35,36, pointing out that the mechanism of HPRR on MoS2 is analogous to the one on a Pt surface60. In the initial step, H2O2 is adsorbed onto the Mo atoms of the MoS2 edges. The O–O bond of the adsorbed H2O2 is then spontaneously cleaved, which generates two ⋅OH. These radicals are subsequently reduced via charge transfer from the modified electrode. Therefore, ⋅OH radicals are a key intermediate in the H2O2 reduction reaction. Their formation is favored on 1T-MoS2, providing a reaction pathway that lowers the onset potential and reduces the Tafel slope, thereby enhancing the overall reaction kinetics.

Within this mechanism, the phase of MoS2 plays a fundamental role. The 1T phase significantly improves the kinetics of the spontaneous catalytic decomposition of H2O2 into ⋅OH compared to the 2H phase. Furthermore, the higher conductivity of the 1T phase facilitates the electron transfer process involving the ⋅OH reduction at the interface of the electrode. Also, MoS2 morphology is a key feature as the catalytically active sites are located at the edges of the 2D material. Once again, we would like to point out that, even if 1T enriched MoS2 represents a cost-effective alternative to Pt, this precious metal still represents an unmatched standard for H2O2 reduction reaction, providing a lower Tafel slope and Tafel constants, and higher exchange current densities (Table S1; Fig. S16).

This work aims to bridge the gap between MoS2 structural properties and its electrocatalytic activity for HPRR. By applying EIS and Tafel plots analysis, we provided data never reported in previous electrochemical investigations (Table S1). The collected data agree with previously published DFT calculations, demonstrating how the crystalline phase and the morphology of MoS2 are fundamental parameters to consider when using this material as an electrocatalyst for HPRR. Both electrochemical and colorimetric measurements demonstrate that 1T-MoS2 presents outstanding catalytic and electrocatalytic properties. When comparing 1T-MoS2 obtained by different synthetic approaches, further differences arise. E1T-MoS2 is characterized by a planar morphology with a less defective structure. For this reason, this material presents elevated conductivity, but few active sites that are rapidly saturated at low overpotentials. On the other hand, H1T-MoS2 is characterized by several defects and numerous jagged edges, which work as catalytic sites but affect the material’s conductivity. Based on these observations, we can conclude that the use of E1T-MoS2 can be suggested for electrocatalytic applications and electrochemical sensors, where high overpotentials are applied, while H1T-MoS2 is preferable for heterogeneous catalysis and colorimetric sensors.

Methods

Synthesis and characterization

Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) was exfoliated in its 2H phase (2H-MoS2) by ultrasonication of bulk MoS2 in N-methylpyrrolidone. 150 mg of bulk MoS2 was suspended in 150 mL of NMP (1 mg/mL), and subsequently sonicated in a sonicator bath for 4 h, at 0 °C. The suspension was centrifuged, and the supernatant was filtered on a PTFE membrane with 0.45 μM of pore size. The material was washed with 1 L of Milli-Q water and resuspended in 100 mL of Milli-Q water37.

The chemically exfoliated MoS2 (E1T-MoS2) was obtained by butyllithium (BuLi) intercalation and exfoliation. 250 mg of MoS2 were dried at 100 °C in a Schlenck tube (with a capacity of 50 mL) for 16 h and then heated with a heat gun under vacuum to eliminate any trace of water. Under an inert atmosphere (Ar), 15 mL of dry hexane and 4 mL of BuLi (2.5 M in hexane) were added, and the mixture was heated at 70 °C for 24 h. The mixture was then cooled with an ice bath, and BuLi was quenched by adding water drop by drop until the disappearance of bubbling. The crude was sonicated to disperse the material, then the material was extracted from the organic phase with Milli-Q water using a separating funnel. The aqueous phase was washed twice with hexane, sonicated for 1 h, and subsequently centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 1.5 h at 5 °C. The supernatant was filtered on PTFE filters and washed with Milli-Q water to recover the material, which was finally resuspended in Milli-Q water38.

The hydrothermally synthesized MoS2 (H1T-MoS2) was obtained by hydrothermal reaction of molybdenum oxide with urea and thioacetamide. 36 mg of MoO3, 360 mg of urea, and 42 mg of thioacetamide were dissolved in H2O, introduced in an autoclave, and stirred for 4 h at 35 °C. The solutions were then heated at 200 °C for 16 h. After rapid cooling, the material was recovered by filtration on PTFE filter and washed with 1 L of Milli-Q water. After resuspending the material in 10 mL of Milli-Q water by sonication for 1 h, the suspensions were centrifuged at 750 rpm for 30 min at 10 °C, and the supernatant was recovered39.

UV-Vis spectra were collected with an Agilent Cary 5000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer, at room temperature with quartz cuvettes, in a wavelength range between 200 nm and 800 nm.

Raman spectra were recorded using a Renishaw inVia Raman microscope. A laser excitation wavelength of 633 nm, lens-based spectrometer with 1800 gr mm−1 gratings, Peltier-cooled front-illuminated CCD camera (1024 × 532 px), and a 100× objective were employed. Samples were prepared by drop-casting MoS2 solution on a silicon oxide slide and drying it under ambient conditions. Each spectrum is derived from the average of at least 100 spectra recorded in different sample spots for 5 seconds with a laser power of 1.29 mW. Data were processed using Renishaw WiRE 4 software.

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) spectra were registered with an XPS/UPS – SPECS SAGE HR-100 equipped with a 100 mm radius PHOIBOS analyser, where 421 Mg Kα X-ray source was used. The samples were prepared by depositing 0.5 mg on copper tape. The spectra were fitted using CasaXPS, and calibration was performed using the major component of the C high-resolution spectrum as a reference at 284.8 eV, which is the value reported for adventitious and sp3 C-C carbon.

AFM images were obtained with a Nanoscope IIIa, VEECO Instruments. As a general procedure, AFM analyses were performed using tapping mode with an HQ:NSC19/ALBS probe (80 kHz; 0.6 N/m) (MikroMasch). Samples were prepared by drop casting of the aqueous suspension (5 μg/mL) on exfoliated mica substrates. The obtained AFM images were analyzed on the software Nanoscope and Gwyddion 2.58. AFM micrographs were collected in tapping mode, with a scan frequency of 0.5 Hz, collecting 756 sampled points per 756 sampling line.

TEM images were recorded with a Phillips CM200 transmission electron microscope equipped with a Quemesa camera (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions) and RADIUS software for image acquisition. Samples were prepared by dropcasting the aqueous suspensions (concentration 0.5 mg/mL) on Lacey Carbon 300 mesh copper grids (approx. grid hole size: 63 µm), purchased from TED PELLA Inc.

Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical measurements were performed using an electrochemical workstation Autolab MSTAT204 potentiostat/galvanostat (Metrohm Autolab) interfaced to a PC with Nova 2.1.7 software, at laboratory room temperature (25 °C). A glassy carbon electrode (GCE, diameter = 0.5 cm) was used to perform the experiments with MoS2. A commercial platinum electrode (diameter = 0.2 cm) was used as a standard to compare the performance of the modified GCE. Before each experiment, the GCE was polished on alumina 0.2 μm and sonicated in Milli-Q water, and was then modified by drop casting 10 μL of 0.5 mg/mL suspensions of the materials. For CA measurements, upon drying of the MoS2 suspension, 5 μL of 1% Nafion solution was dropcasted on the modified electrode to immobilize the catalyst. Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) and a platinum wire were used, respectively as reference and counter electrodes. The ECSA was estimated by electrochemical capacitance measurements53.

Before each measurement, solutions were degassed by bubbling N2 in the solution for ten minutes. CV was performed by scanning the applied potential from 0.2 V to −0.8 V, with a scan rate of 10 mV/s. Data were graphed without ulterior manipulation, with Origin software.

CA was carried out at a constant potential of −0.3 V, over 50 s and the signal was sampled at 15 s. The measurements were conducted with 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6 and 8 mmol L−1 solutions of H2O2 in PBS 0.1 mol L−1, KCl 0.1 mol L−1. Data were graphed, analyzed, and fitted with Origin software.

For Tafel analysis, open-circuit potentials were determined to identify the equilibrium potential for the reaction. Subsequently, the potential range was selected accordingly, and the potential was scanned with a scan rate of 10 mV/s in linear sweep voltammetry. By plotting the logarithm of the current against the applied potential, the polarization curve was obtained, which was then centered on the minimum individuating the onset potential of the reaction and reported against the overpotential applied over the onset potential (Figure S4a). From the linear fitting of the two branches of the obtained polarization curve, the exchange current density was determined as the intersection between the fitted lines. The same curve was then plotted as overpotential versus logarithm of the current, and the cathodic branch was isolated and linearly fitted (Fig. S4b). From this linear fitting, the Tafel slope and the Tafel constant were determined as the slope and the intercept of the fitted line, respectively. Data were analyzed and fitted using Origin software.

Finally, EIS measurements were conducted at low overpotential (0.15 V) and high overpotential (−0.3 V), with a potential amplitude of 0.01 V, scanning frequencies from 0.1 Hz to 105 Hz, and 10 frequencies per decade. Data were fitted using NOVA 2.1.6 software from Metrohm and subsequently graphed with Origin software.

Colorimetric assay

All colorimetric tests were performed in acetate buffer 0.1 M, at pH 3.5. UV-Vis spectra were collected with an Agilent Cary 5000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer, at room temperature with plastic cuvettes, in a wavelength range between 300 nm and 800 nm. In each cuvette, 100 μL of MoS2 suspension (0.1 mmol L−1) were incubated with 100 μL of TMB solution (10 mmol L−1, in acetate buffer 0.1 mol L−1) and 50 μL of H2O2 (1 mol L−1) in 750 μL of acetate buffer 0.1 mol L−1, for a total volume of 1 mL.

The UV-Vis kinetics were registered at 652 nm with a TECAN Infinite M1000 Pro multiwell plate reader, with plastic flat base 96 multiwell plates purchased from Sarstedt. In each well, 20 μL of MoS2 suspension (0.1 mmol L−1) were incubated with 20 μL of TMB solution (10 mmol L−1, in acetate buffer 0.1 mol L−1) and different concentrations of H2O2 (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 50, and 200 mmol L−1), in acetate buffer 0.1 mol L−1 (total volume of 200 μL). Data from kinetic were subsequently analyzed by Origin and Excel software.

Data availability

Data for this article are available at the Datarepository Unive (https://datarepository.unive.it/) at https://doi.org/10.71731/DATA_UNIVE/AN6VHV.

References

Sies, H. Hydrogen peroxide as a central redox signaling molecule in physiological oxidative stress: Oxidative eustress. Redox Biol. 11, 613–619 (2017).

Forman, H. J., Bernardo, A. & Davies, K. J. A. What is the concentration of hydrogen peroxide in blood and plasma? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 603, 48–53 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Specific and long-term luminescent monitoring of hydrogen peroxide in tumor metastasis. Adv. Mater. 35, 2210948 (2023).

Milton, N. G. N. Role of Hydrogen peroxide in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 21, 81–100 (2004).

Chang, K.-H. & Chen, C.-M. The role of oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxidants 9, 597 (2020).

Percário, S. et al. Oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease: potential benefits of antioxidant supplementation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2360872 (2020).

Minzaghi, D. et al. Excessive production of hydrogen peroxide in mitochondria contributes to atopic dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 143, 1906–1918.e8 (2023).

Bertino, L. et al. Oxidative stress and atopic Dermatitis. Antioxidants 9, 196 (2020).

Lipińska, W., Siuzdak, K., Karczewski, J., Dołęga, A. & Grochowska, K. Electrochemical glucose sensor based on the glucose oxidase entrapped in chitosan immobilized onto laser-processed Au-Ti electrode. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 330, 129409 (2021).

Kang, X. et al. Glucose Oxidase–graphene–chitosan modified electrode for direct electrochemistry and glucose sensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 25, 901–905 (2009).

Silvestri, A. et al. Bioresponsive, electroactive, and inkjet-printable graphene-based inks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2105028 (2022).

Trujillo, R. M., Barraza, D. E., Zamora, M. L., Cattani-Scholz, A. & Madrid, R. E. Nanostructures in hydrogen peroxide sensing. Sensors 21, 2204 (2021).

Giaretta, J. E. et al. Flexible sensors for hydrogen peroxide detection: a critical review. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 20491–20505 (2022).

Riaz, M. A. & Chen, Y. Electrodes and electrocatalysts for electrochemical hydrogen peroxide sensors: a review of design strategies. Nanoscale Horiz. 7, 463–479 (2022).

Acerce, M., Akdoğan, E. K. & Chhowalla, M. Metallic molybdenum disulfide nanosheet-based electrochemical actuators. Nature 549, 370–373 (2017).

Voiry, D., Mohite, A. & Chhowalla, M. Phase engineering of transition metal dichalcogenides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2702–2712 (2015).

Nicolosi, V., Chhowalla, M., Kanatzidis, M. G., Strano, M. S. & Coleman, J. N. Liquid exfoliation of layered materials. Science 340, 1226419 (2013).

Xu, M., Liang, T., Shi, M. & Chen, H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem. Rev. 113, 3766–3798 (2013).

Yin, X. et al. Recent developments in 2D transition metal dichalcogenides: phase transition and applications of the (quasi-)metallic phases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 10087–10115 (2021).

Escalera-López, D. et al. Allotrope-dependent activity-stability relationships of molybdenum sulfide hydrogen evolution electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 15, 3601 (2024).

Manyepedza, T., Courtney, J. M., Snowden, A., Jones, C. R. & Rees, N. V. Impact electrochemistry of MoS2: Electrocatalysis And Hydrogen Generation At Low Overpotentials. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 17942–17951 (2022).

Tian, L. et al. MoS2-Based Catalysts for N2 electroreduction to NH3 – an overview of MoS2 optimization strategies. ChemistryOpen 10, 1041–1054 (2021).

He, C. et al. Oxygen reduction reaction promoted by the strong coupling of MoS2 and SnS. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 4, 9498–9506 (2021).

Luo, Y. et al. Plasma functionalized MoSe2 for efficient nonenzymatic sensing of hydrogen peroxide in ultra-wide pH range. SmartMat 3, 491–502 (2022).

Haritha, V. S., Sarath Kumar, S. R. & Rakhi, R. B. Non-enzymatic electrocatalytic detection of hydrogen peroxide using Tungsten disulphide nanosheets modified electrodes. Mater. Sci. Eng.: B 285, 115932 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Biosensor based on ultrasmall MoS2 nanoparticles for electrochemical detection of H2O2 released by cells at the nanomolar level. Anal. Chem. 85, 10289–10295 (2013).

Lin, T., Zhong, L., Guo, L., Fu, F. & Chen, G. Seeing diabetes: visual detection of glucose based on the intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of MoS2 nanosheets. Nanoscale 6, 11856–11862 (2014).

Guo, X., Wang, Y., Wu, F., Ni, Y. & Kokot, S. A colorimetric method of analysis for trace amounts of hydrogen peroxide with the use of the nano-properties of molybdenum disulfide. Analyst 140, 1119–1126 (2015).

Haritha, V. S., Vijayan, A., Sarath Kumar, S. R. & Rakhi, R. B. Voltammetric determination of hydrogen peroxide using MoS2 modified glassy carbon electrodes. Mater. Lett. 301, 130258 (2021).

Cao, P., Wang, N., Dai, H., Ma, H. & Lin, M. Molybdenum-containing polypyrrole self-supporting hollow flexible electrode for hydrogen peroxide detection in living cells. Anal. Chim. Acta 1151, 338251 (2021).

Guo, X. et al. Charge self-regulation in 1T”’-MoS2 structure with rich S vacancies for enhanced hydrogen evolution activity. Nat. Commun. 13, 5954 (2022).

Tang, Q. & Jiang, D. Mechanism of hydrogen evolution reaction on 1T-MoS2 from first principles. ACS Catal. 6, 4953–4961 (2016).

Tang, J., Huang, J., Ding, D., Zhang, S. & Deng, X. Research progress of 1T-MoS2 in electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 39771–39795 (2022).

Shu, Y. et al. Expanding the interlayers of molybdenum disulfide toward the highly sensitive sensing of hydrogen peroxide. Nanoscale 11, 6644–6653 (2019).

Gupta, A. et al. Molybdenum disulfide for ultra-low detection of free radicals: electrochemical response and molecular modeling. 2D Mater. 4, 025077 (2017).

Li, Q. et al. Interaction mechanism between multi-layered MoS2 and H2O2 for self-generation of reactive oxygen species. Environ. Res. 191, 110227 (2020).

Coleman, J. N. et al. Two-dimensional nanosheets produced by liquid exfoliation of layered materials. Science 331, 568–571 (2011).

Fan, X. et al. Controlled exfoliation of MoS2 crystals into trilayer nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5143–5149 (2016).

Geng, X. et al. Pure and stable metallic phase molybdenum disulfide nanosheets for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 7, 10672 (2016).

Krajewska, A. M., Paiva, A. E., Morris, M. & McDonald, A. R. Reduction of exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets yields the semi-conducting 2h-polymorph rather than the metallic 1T-polymorph. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 27, e202400292 (2024).

Nayak, A. P. et al. Pressure-dependent optical and vibrational properties of monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett. 15, 346–353 (2015).

Kaur, J. et al. Biological interactions of biocompatible and water-dispersed MoS2 nanosheets with bacteria and human cells. Sci. Rep. 8, 16386 (2018).

Li, H. et al. From bulk to monolayer MoS2: Evolution of Ramanscattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 1385–1390 (2012).

Arellano Arreola, V. M. et al. Direct growth of monolayer 1T–2H MoS2 heterostructures using KCl-assisted CVD process. 2D Mater. 8, 025033 (2021).

Alemán-Vázquez, L. O., Torres-García, E., Villagómez-Ibarra, J. R. & Cano-Domínguez, J. L. Effect of the particle size on the activity of MoOxCycatalysts for the isomerization of heptane. Catal. Lett. 100, 219–226 (2005).

Windom, B. C., Sawyer, W. G. & Hahn, D. W. A Raman spectroscopic study of MoS2 and MoO3: applications to tribological systems. Tribol. Lett. 42, 301–310 (2011).

Zhao, Y. & Ouyang, G. Thickness-dependent photoelectric properties of MoS2/Si heterostructure solar cells. Sci. Rep. 9, 17381 (2019).

Xi, Z. et al. Nickel–Platinum nanoparticles as peroxidase mimics with a record high catalytic efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 2660–2664 (2021).

Pedone, D., Moglianetti, M., Lettieri, M., Marrazza, G. & Pompa, P. P. Platinum Nanozyme-Enabled Colorimetric Determination of Total Antioxidant Level in Saliva. Anal. Chem. 92, 8660–8664 (2020).

Ma, M., Zhang, Y. & Gu, N. Peroxidase-like catalytic activity of cubic Pt nanocrystals. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 373, 6–10 (2011).

Kora, A. J. & Rastogi, L. Peroxidase activity of biogenic platinum nanoparticles: A colorimetric probe towards selective detection of mercuric ions in water samples. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 254, 690–700 (2018).

Wang, Z., Yang, X., Yang, J., Jiang, Y. & He, N. Peroxidase-like activity of mesoporous silica encapsulated Pt nanoparticle and its application in colorimetric immunoassay. Anal. Chim. Acta 862, 53–63 (2015).

Kibsgaard, J. et al. Designing an improved transition metal phosphide catalyst for hydrogen evolution using experimental and theoretical trends. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 3022–3029 (2015).

Wu, W., Lu, Q., Li, G. & Wang, Y. How to extract kinetic information from Tafel analysis in electrocatalysis. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 221501 (2023).

Voiry, D. et al. Best practices for reporting electrocatalytic performance of nanomaterials. ACS Nano 12, 9635–9638 (2018).

Anantharaj, S. & Noda, S. How properly are we interpreting the Tafel lines in energy conversion electrocatalysis? Mater. Today Energy 29, 101123 (2022).

Barbir, F. Chapter Three - Fuel Cell Electrochemistry. in PEM Fuel Cells (Second Edition) (ed. Barbir, F.) 33–72 (Academic Press, Boston, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-387710-9.00003-5.

Sharma, U., Karazhanov, S., Alonso-Vante, N. & Das, S. Metallic-phase of MoS2 as potential electrocatalyst for hydrogen production via water splitting: A brief review. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 35, 101067 (2022).

Swamy, T. & Chiang, Y.-M. Electrochemical charge transfer reaction kinetics at the silicon-liquid electrolyte interface. J. Electrochem. Soc. 162, A7129 (2015).

Biby, A., Crawford, H. & Xia, X. Platinum-group metal nanoparticles as peroxidase mimics: implications for biosensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 17622–17631 (2022).

Acknowledgements

M.P. is the AXA Chair for Bionanotechnology (2016−2026). The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the University of Trieste, Ca’ Foscari University Venice, INSTM, and the Italian Ministry of Education MIUR (cofin Prot. 20228YFRNL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was written through the contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. Specifically, the contribution of each author is listed below: Giuseppe Misia: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft; Maurizio Prato: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; Alessandro Silvestri: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Misia, G., Prato, M. & Silvestri, A. The impact of the crystalline phase and morphology of MoS2 on the electrocatalytic reduction of H2O2. npj 2D Mater Appl 10, 1 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00630-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00630-9