Abstract

Borophene, a single-atom-thick boron sheet, exhibits rich polymorphism that could enable control of its physical properties, though growing pre-designed polymorphs remains challenging due to complex interaction with metal substrates. Here, we investigate in detail the complex interfacial interactions between a layer of a single χ6 borophene polymorph and the Ir(111) surface through a combined experimental and computational approach using scanning tunnelling microscopy/spectroscopy (STM/STS) and density functional theory (DFT). The emergence of a hybrid interface state (IFS) and novel hybrid and resonant image potential states (IPSs), which are anisotropically modulated along the borophene unit cell, is revealed. These findings provide comprehensive insight into the electronic properties of an intriguing borophene—substrate interface and deepen the understanding of interfacial physical phenomena occurring in substrate-supported two-dimensional (2D) materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

First predicted computationally1,2,3 and later realized experimentally4,5, borophene, a single-atom-thick boron layer, has emerged as a particularly intriguing synthetic 2D material6,7 because of its anticipated anisotropic metallic8, optoelectronic9 and mechanical properties10,11. The electron deficiency of boron (B), compared to carbon, limits the ability to form stable, planar sp2 lattices, which can only be attained if additional electrons are provided. A surprising but simple mechanism for achieving this consists in incorporating additional B atoms into the honeycomb sp2 lattice, filling some of the hollow hexagons. These act as net electron donors without introducing additional empty bonding states, a process named ‘self-doping’ mechanism, enabled by the capability of B to form multi-centre bonds12. Consequently, a multitude of diverse, energetically similar polymorphs emerges, characterized by the density and periodic distribution of voids, i.e. missing atoms in the atomic structure of a regular honeycomb sp2 lattice of B atoms13. This rich polymorphism is envisioned to enable deterministic control over properties and functionalities through the growth of borophene with specific atomistic structure14,15,16.

However, achieving an ‘on-demand’ selection of a polymorph remains a great challenge today due to the complex interfacial interplay between borophene and the supporting metal substrate. These substrates do not only serve as an external charge supply for the electron-deficient lattice but can also influence the polymorph formation through additional factors such as atomic registry and interfacial chemical hybridization4. The intricate balance between these factors is evidenced by the distinct borophene polymorphs formed on different substrates, e.g. Ag(111)17,18, Au(111)19, and Cu(111)20,21, in which multiple polymorphs or surface alloys can even coexist on the same substrate. In contrast, substrates like Al(111) or Ir(111) promote the formation of a single polymorph across a wide range of growth parameters, regardless of the growth method, e.g. chemical vapor deposition (CVD)22,23 or molecular beam epitaxy for the case of Ir(111)24. However, on Al(111), borophene forms a B–Al surface alloy rather than a quasi-freestanding layer25. The Ir(111) surface, on the other hand, provides an optimal degree of interaction; strong enough to stabilize a single polymorph (referred to as χ6 borophene) yet weak enough to preserve the monolayer’s structural integrity separately from the substrate. This quality was demonstrated by gold intercalation24, and more recently, exploited for transferring borophene to a technologically relevant substrate26. Providing a comprehensive understanding of the complex interfacial interaction occurring in the special case of borophene on Ir(111) is therefore important for the goal of achieving deterministic control over polymorphs. In this regard, the investigation of various unoccupied electronic states at surfaces has provided valuable information about the physicochemical properties of materials27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Particularly interesting are bulk-like states (BS), primarily localized within the bulk; surface states, confined to the surface and decaying exponentially into the vacuum; and IPSs, which extend further into the vacuum beyond the surface. In addition, interfacial states (IFS) become particularly significant29 at the boundary between two materials, i.e. 2D layer and substrate, and are directly tied to the characteristics of the interfacial interactions. The importance of these states lies also in their role as an indirect probe of the borophene structure, especially when a de-convolution of electronic effects is not straightforward due to the interaction with the substrate and geometric features. This has been exemplarily shown in a recent report in which the copper boride nature of atomically thin boron phases grown on Cu(111) was elucidated21.

In this work, we present an atomistic study of the interfacial electronic structure of the χ6 borophene polymorph on Ir(111). By combining STM and STS experiments with DFT characterization of the electronic structure of borophene models, we unveil the emergence of a hybrid IFS, visible as a low-energy resonance in STS and characterized by contributions from both borophene and Ir surface atoms. Additionally, we identify hybrid and resonant IPSs, which arise from the linear combination of borophene IPSs with Ir(111) surface states, constituting a phenomenon never observed to date. We compare the simulated properties of different arrangements of B atoms within borophene layers, which allows us to relate the experimentally observed properties to the strength of B-Ir interaction and to discuss the driving force behind the stabilization of the χ6 polymorph. The understanding of interfacial physics, provided here for the exemplary case of borophene on Ir(111), is highly relevant for engineering substrate-stabilized borophenes, where complex substrate effects must be accounted for to move beyond the limitations of the self-doping mechanism.

Results and discussion

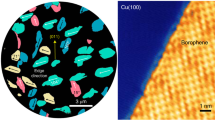

Polymorph identification

Borophene was grown on an atomically clean and flat Ir(111) surface, as schematically shown in Fig. 1a, following the ultra-high vacuum CVD method introduced previously by some of the authors22. Fig. 1b shows an STM image of atomically thin single-crystalline borophene monolayer domains that partially cover the underlying surface, revealing three equivalent rotational domains with identical stripy appearance. These form atomically precise interfaces with Ir(111) that result in a characteristic appearance consisting of parallel stripes with a longitudinal periodic ‘wavy’ modulation (Fig. 1c). This appearance was earlier attributed to a 2 × 6 commensurate stacking between a χ6-like borophene polymorph and Ir(111)24, where χ refers to a varying coordination number (4-5) and ‘6’ to the areal density of hexagonal voids (η = 1/6), following the notation introduced by Tang et al.2 and later extended by Wu et al.16. We performed STM imaging of this polymorph on Ir(111) to extract its structural parameters. Fig. 1d shows for the first time such a real-space visualization of the atomistic structure with intra-cell resolution. The superimposed atomistic structure of the most stable χ6 polymorph proposed in literature (ref. 24) reveals additional details. Five B atoms in the unit cell have a coordination number of four and twenty B atoms have a coordination number of five. Furthermore, five out of the thirty sites in a hypothetical trigonal matrix remain vacant (i.e., η = 1/6). The experimental observations are thus consistent with this atomistic model currently accepted for this widely studied borophene polymorph22,23,24,26,34,35,36,37.

a Schematic side-view of borophene monolayer domains (MLs) forming atomically sharp interfaces with the Ir(111) substrate. b Overview STM image of borophene MLs, showing different domains oriented in a three-fold degenerate configuration (scale bar 10 nm). Note that the small point-like bright protrusions present on borophene and on bare Ir(111) regions correspond to adsorbates, as shown in Fig. S17. c STM image of a single crystalline domain featuring the characteristic stripy appearance and periodic ‘wavy’ pattern described in the text (highlighted by red lines, scale bar 2 nm). d High resolution STM image with superimposed atomistic model of the χ6 polymorph (lattice parameters: 16.27 Å and 5.42 Å, with the unit cell in blue and B atoms depicted as red spheres). STM parameters b: 3.30 V and 0.30 nA, c: 0.60 V and 0.30 nA, d 0.01 V and 1.20 nA.

The comparison between the experimental STM images with those obtained through DFT calculations shows an agreement of the structural features (Fig. S1), even though the contrast of the simulated images needs to be inverted (regardless of the density functional (HSE06-D3 or PBE-D3) and the type of pseudopotentials used (Fig. S2)). To emphasize the broader relevance of our numerical findings and the value of the applied model, we also examine the second most stable structure in ref. 24, labelled as i4 (see Fig. S3). For clarity and conciseness, we focus in the following on the results of the simulations performed for the originally proposed χ6 model, while additional information on the i4 structure is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Work function

The fact that a unique borophene χ6 polymorph forms on the Ir(111) substrate, under a wide range of growth parameters and methods (molecular beam epitaxy (MBE)24 or CVD22,23), highlights the dominant role this substrate plays in stabilizing this synthetic 2D material. To shed light on the interfacial interactions underlaying the stabilization of the polymorph, we conducted an STS study of the local electronic structure of borophene on Ir(111) with sub-nanometre precision. The STM tip is positioned on the spot of interest and the dI/dV signal is acquired while a positive bias voltage is swept up to 10 V with the feedback loop active to keep the tunnelling current constant (see “Methods”). At energies beyond the work function of a surface, field emission resonances (FERs), also known as Gundlach oscillations38, are expected, corresponding to Stark-shifted IPSs confined between the sample surface and the STM tip39. The energy positions of these resonances follow a Rydberg-like progression, which is clearly visible in the purple and red spectra in Fig. 2a measured on the bare Ir(111) and borophene regions of Fig. 2b, respectively. Probing these states at the local scale allows to access information on the interfacial coupling, lifetimes, and local work function with sub-monolayer resolution21,40,41,42. The position of the first intense FER (i.e., first IPS), appearing at 5.7 V for Ir(111) and 5.2 V for borophene, provides a first approximation of the local work function43, revealing a reduction at the borophene-covered areas. This is in fairly good agreement with work function values obtained using alternative experimental methods (5.8 eV for Ir(111)44, 4.737–5.3 eV35 for borophene/Ir(111)). Differential conductance maps taken at 5.2 V and 5.8 V evidence the spatial localization of the interfacial electronic structure, with an inverted contrast between bare Ir and borophene-covered Ir areas for the two voltages (Fig. 2d, e), further supporting the work function reduction induced by borophene.

a Constant-current dI/dV intensity plot measured along the dashed line (composed by spectra taken every 8 Å) in the STM topographic image in (b) (0.60 V and 0.3 nA). Spectra measured on the Ir(111) and borophene spots, marked respectively by purple and red crosses in (b), are displayed individually. Their baselines, corresponding to dI/dV = 0, are marked by horizontal purple and red lines, respectively. Constant-current dI/dV maps measured at bias voltages corresponding to the IFS (c), the IPSn=1 of borophene (d) and Ir(111) (e). Stabilization parameters 0.60 V and 0.3 nA. f Series of constant-current dI/dV spectra taken on borophene at increasing tip-sample electric field. This is achieved by increasing the stabilization tunnelling current (from 0.25 to 9.25 nA, steps of 0.25 nA) while keeping the bias voltage unchanged between spectra (0.30 V), that is decreasing tip-sample distance43. Curves have been vertically offset for clarity of visualization. Lock-in modulation of all spectra in the figure: 50 mV (peak-to-peak).

This effect is also captured by DFT calculations, which yield work functions values of 4.4 eV for borophene on Ir(111) and 5.5 eV for bare Ir(111), the latter being in good in agreement with previous calculations (5.5 eV)45. Such a reduction can be explained by the charge transfer of 0.008/0.003 e−/Å2 from borophene to Ir, calculated through Bader46,47/DDEC648,49,50 analysis and comparable with the 0.08 e−/B atom (0.02 e−/Å2) previously reported24. Such inward charge transfer is expected to induce a reduction of the work function due to the formation of an outward dipole at the interface. As it will be discussed in detail below, this interpretation is further supported by the additional decrease of the local work function above those atoms of the borophene unit cell that lay closer to Ir(111), featuring an increased interfacial charge transfer. Interestingly, Liu and co-workers observed an opposite, but consistent, trend on the Ag(111) surface, i.e., a work function increase of Ag(111) when covered by borophene with a net charge transfer from the metal support to borophene.

Hybrid borophene—Ir(111) IFS

In the STS spectrum of Fig. 2a, one observes an additional, broad feature at ~3.4 V whose spectral weight extends only over borophene areas (Fig. 2c). Such a low energy resonance cannot be assigned to an IPS, for the following reasons: (i) it is located at an energy well below the expected work function, (ii) it does not follow the Gundlach relation38 defined by the high energy IPSs peaks (n > 2, Fig. S4) and (iii) it does not exhibit a detectable Stark shift upon variation of the tip-sample electric field. The last point is shown in Fig. 2f, which presents a series of STS spectra measured consecutively at decreasing tip-sample distance, i.e. increasing electric field. The positions of the n ≥ 1 resonances shift to higher voltages with increasing electric field (i.e., decreasing tip-sample distance), as expected for IPSs due to their extended spatial localization in the vacuum that makes them especially sensitive to external fields. This trend, however, is not observed for the low-energy resonance at ~3.4 V. Accordingly, it is tentatively attributed to an IFS (see below). Similar IFSs have been previously reported for borophene on Ag(111)42 and on Cu(111)21, as well as for other metal-supported 2D materials40,51,52,53. It is worth noting that in borophene on Ag(111) and on Ir(111), the IFS arises from interface hybridization but differs in character: Ag(111) shows a weaker, charge-transfer-driven IFS, while Ir(111) exhibits a more strongly hybridized, spatially modulated state due to robust local registry. In contrast, the IFS in the B-Cu surface alloy results from stronger covalent Cu–B interaction and charge transfer, producing a more mixed, less isolated interface resonance21. This scenario is compatible with the insight about interfacial chemical bonding provided by high-resolution XPS available in the literature. In the weaker interacting systems of borophene on Ag(111)54 and Ir(111)22,35 (where borophene can preserve its monolayer integrity independently of the substrate), well-defined B 1 s peaks reflect intrinsic polymorph coordination rather than strong B-metal alloying, as observed in the case of Al(111)25.

To unveil the IFS origin of the low-energy resonance and provide atomistic foundations to the experimental insight described in the previous section, we disentangle several different physical contributions through numerical simulations. First, we investigated the density of states (DOS), projected on the atomic orbitals of the Ir atoms at the topmost layer of the substrate and on those of the B atoms, reported in Fig. S5. Indeed, such a comparison provides an initial assessment of the strong overlap of the contributions of the two atomic species. Yet, we find it more informative to analyse the band structure of borophene on Ir(111) including the projection of the wavefunctions on the atomic orbitals of Ir and B atoms (Fig. 3a, c). In an energy window of ± 1 eV around the Fermi level (EF), electronic states are mostly contributed by Ir(111); for energies below EF − 1 eV, states are equally contributed by borophene and Ir(111), resulting in an overlap between borophene and Ir(111) states that suggests a strong interaction between the borophene monolayer and Ir(111). For energies above EF + 1 eV, the electronic states are mostly contributed by borophene. In this region, a few bands localized also on Ir atoms can be clearly observed, for which, however, the overlap with B contributions is less evident. The nature of such states can be clarified by evaluating whether they exhibit the characteristics of the clean metallic surface. Fig. 3b, d compares the band structure of borophene on Ir(111), projected onto Ir and B atoms, respectively, unfolded onto the Brillouin zone of bare Ir(111). The unexpectedly strong resemblance of B-projected states with the bands of the Ir(111) surface allows to identify hybrid borophene—Ir(111) surface states (i.e., states made of a linear combination of B atomic orbitals and Ir surface state)45,55. The intense green traces around the M point at energies around EF + 1 eV and, additionally, the B states around the K and M points, at energies between 4 and 6 eV above EF, display a pronounced hybrid character as they clearly overlap with those of pristine Ir(111). Among them, several surface states can be found (see Fig. S6). Given their energy and surface-localized character52, they are good candidates to cause the low-energy resonance observed by STS (Fig. 2a), with the projected band structures providing clear evidence of hybridization of Ir with B states. In the case of the alternative borophene on Ir(111) model i4, we found similar electronic properties. In the corresponding band structure reported in Fig. S7, the atomic orbital decomposition of the band structure shows an overlap of contributions from B and Ir atoms. This result suggests that the strength of the interaction between borophene and the Ir(111) surface is not dependent on the actual arrangement of the B atoms considered.

a, b Band structure projected at the Brillouin zone of χ6 borophene 2 × 6 supercell on Ir(111). c, d Unfolded band structure on the Brillouin zone of Ir(111) together with pristine Ir(111) band structure (black lines). Blueand green dots correspond to the projection of bands onto Ir and B atoms, respectively. Solid and dashed horizontal black lineshighlight the vacuum level and E, respectively. In (a, b), the orange areas highlight those states which are good IPS candidates forfurther analysis. Bpn refers to borophene.

Hybrid borophene—Ir(111) IPSs

To provide further insights into the IPSs resolved in the STS measurements, a detailed analysis of the electronic states calculated through DFT was performed. As presented in Fig. 3 (highlighted by orange in panels a and b), above EF + 4 eV, several bands fulfilling three expected characteristics of IPSs can be observed: (i) parabolic dispersion, (ii) negligible weight on atomic orbitals and (ii) bound-state nature. Even though a direct correspondence with the position of the measured FERs is not possible due to the Stark effect induced by the local electric field at the biased tip-sample gap and tip condition43, these bands could be assigned to the experimentally observed series of IPSs for borophene on Ir(111). We will provide further evidence and support of this in the following through the analysis of the slow decay of these states into the vacuum, typical of IPSs, in contrast to the faster exponential decay characteristic of surface and bulk states. This is performed in the idealized case where no local electric field is applied. For the specific case where an electric field is applied, the reader is referred to Fig. S13.

Starting with the case of bare Ir(111), surface states and IPSs can be distinguished through the position of |Ψ|2(z) maxima, moving along the surface normal towards the vacuum. IPSs are characterized by their spectral weight beyond the outer Ir layer (e.g., IPSn=1 presents a single maximum at around ~ 5 Å, IPSn=2 has two maxima at ~ 5 Å and ~ 20 Å, while the surface state presents a maximum at ~ 2 Å above the outer Ir layer (Fig. S8)). In the case of free-standing borophene, in the frozen geometry of the interfacial layer, several IPS-like wavefunctions can be identified in Fig. S6 as one or more peaks far from the surface. Among them, there are two states with symmetric |Ψ|2 (with respect to the borophene layer, shown by green and mustard-coloured lines in Fig. S9). These have maxima at around ± 3 Å or ± 10 Å, respectively, from the B atomic plane, and are separated in energy by ~ 0.2 eV. Such states are analogous to the linear combinations of the first IPSs (i.e., IPSn=1+,1-) on the two sides of monolayer graphene55,56.

In the case of borophene on Ir(111), a comparison of the characteristic behaviour of several prototypical wavefunctions at the Γ point is shown in Fig. 4. A few states appear between ~ EF + 3 eV and + 4 eV that closely reproduce the |Ψ|2(z) shape of the Ir (111) surface states at Γ (Fig. 4g), hence suggesting that they have a surface state character. Similar observations are noted for wavefunctions calculated at M and K points, as shown in Figs. S10 and S11. In addition, close to the vacuum level at around 4.0 to 4.5 eV above EF, we observe a set of states with |Ψ|2 extending even more into vacuum than surface states (for reference, the plots of all the wavefunctions at the Γ point are collected in Fig. S12). These states are identified as IPSs because of their increasing number of |Ψ|2 maxima with the energy level, following a Rydberg-like series with n and having bands (Fig. 3) with an almost-free electron character. Note that pairs of linearly combined states are observed for the IPSn=1 and IPSn=2, similarly to the case of free-standing borophene above. However, here they have lost their symmetry with respect to the layer due to the presence of Ir (111), as evidenced by |Ψ|2(y,z) plots in Fig. 4g for (IPSn=1 /IPSn=2) and also in Fig. S12 (second and forth panel in the bottom row). Similar observations were reported for graphene on Ir(111)35. We also notice that for both IPSn=1,2 pairs, especially evident for the anti-symmetric IPSn=1-, the final state shows several protrusions along the y direction on the borophene unit cell, within 3 Å from the surface, which resemble those of surface states. This feature is interesting, as it suggests hybridization between borophene IPSs and Ir(111) bulk or surface states, as already reported for graphene on Cu(111)57. Indeed, the corresponding planar averages of |Ψ|2, reported in Fig. 4, show a resonant behaviour, i.e., the residual weight on deep Ir atoms in the slab is non-negligible, in contrast with pure bulk states localized only on Ir atoms (grey area in Fig. 4g). The binding energy of the IPSn=1+,1- pair is ~ 0.4 eV, while that of IPSn=2+/2- is ~ 0.3 eV. These values are similar to those measured for borophene on Ag(111)42, while smaller than the average of those measured for graphene on metallic surfaces30,31. The formation of symmetric/anti-symmetric pairs has a strong analogy to the formation of bonding/anti-bonding pairs, using a chemical notation, therefore supporting the formation of hybrid image potential—surface states.

a–f Comparison of the vacuum decay of the most representative states at the G point: colour representation of |Ψ|^2 within the y-z plane. b Alternative representation of the wavefunction in the vacuum, after averaging it in the x-y plane. One BS is reported as a reference. SS and BS refer to surface and bulk states, respectively. The energies reported in the panels are referred to the Fermi level.

As reported in Fig. S14, the wavefunctions calculated for the alternative i4 borophene model show a character similar to that discussed for the χ6 structure, supporting our hypothesis that the features observed experimentally are indeed originated by the strength of the interaction of borophene with the Ir(111) surface, independent of the actual arrangement of the B atoms.

Spatial modulation of IFS and IPSs

The proposed scenario can also be applied to rationalize local variations of the IFS and IPSs within the χ6 borophene unit cell, which lead to a global modulation of the interface electronic structure in the extended borophene domains. This modulation is reflected in small but clear signatures that can be measured by dI/dV spectroscopy and can be correlated with the occurrence of bright stripes in the STM images. STS and STM data presented in Fig. 5a allow to evaluate such correlations. The figure displays the spatial modulation of dI/dV signals of IFS and IPS, superimposed on an STM image of borophene showing the characteristic stripes.

a Topography and dI/dV profiles superimposed on an STM image of borophene on Ir(111), DFT calculated charge density Δρ and local work function ΔΦ (calculated within the 2 × 6 unit cell depicted by a black rhomboid). Scanning parameters 0.2 V, 0.4 nA. In grey, topographic profile taken along the dashed black line. In pink, blue and green, constant-voltage profiles taken along dashed horizontal lines in (b and d), evidencing the spectral broadening of IPSn=1, IFS and Ir(111) surface state, respectively. Profiles are vertically offset for a better visualization. The three pannels at the background show: STM topography image of borophene on Ir(111) (top pannel), differences in charge density Δρ (middle pannel) and local work function ΔΦ (bottom pannel) calculated by DFT for the 2 × 6 borophene/Ir(111) unit cell (depicted by a black rhomboid). The results obtained for the simulation cell (depicted by the black rhomboid) are replicated across the surface. b Constant-current dI/dV intensity plot taken along the topography profile marked as a dashed black line on the STM image in (e). Stabilization parameters 0.60 V, 0.3 nA, lock-in modulation 50 mV (peak-to-peak), intensity plot is composed by individual spectra taken every 3.5 Å. c Constant-current dI/dV spectra taken from black and red dashed lines in (b), corresponding to a stripe region and an in-between stripe region, respectively in (e). d Constant-height dI/dV intensity plot taken along the same topography profile as in (b). Stabilization parameters 2.30 V, 0.3 nA, lock-in modulation 50 mV (peak-to-peak), intensity plot is composed by 17 individual spectra taken every 2.5 Å. e Constant-height dI/dV spectra taken from black (stripe) and red (in-between stripe) dashed lines in (d). Reference spectrum taken on bare Ir(111) is plotted in purple.

Focusing on the IFS peak, constant-current dI/dV spectra, measured in-between stripes of the borophene monolayer (i.e., parallel dark regions in STM) reveal an energy broadening of the IFS (at 3.4 V) with respect to that measured on stripes (red and black spectrum in Fig. 5c, respectively). This is further visualized in the dI/dV intensity plot in Fig. 5b measured across stripes (i.e., along the black dashed line marked in Fig. 5a), by the oscillating behaviour of the spectral width of the IFS peak (evident at the energy marked by the blue dashed line). In parallel, constant-height dI/dV spectra also measured across stripes present an intensity onset at ~ −0.3 V (Fig. 5e), which is highest on stripe regions (Fig. 5d). This feature (appearing in between −0.3 and −0.4 V when measured on bare Ir(111), Fig. 5e) has been consistently observed before22,23,35 and suggested to be related to the Ir(111) surface state being spatially modulated across borophene stripes35. Similar effects have been observed earlier in other Ir(111)-supported 2D material systems58. When superimposing these data on the STM image of Fig. 5a, it is clear that the states causing the IFS peak present higher spectral weight at the darker regions, in-between the stripes. The periodic increase of IFS width directly anti-correlates with the quenching of the surface state beneath borophene (green line in Fig. 5a), the former of which can be interpreted as a signature of increased hybridization. This interpretation is corroborated by the map of the re-arrangement of the DFT calculated electronic density (Δρ = ρborophene/Ir(111) − ρfree-standing borophene − ρIr(111)), which shows that the areas in-between stripes correspond to areas with stronger charge redistribution (Fig. 5a). The fact that the IFS hybridizes at the expense of the Ir surface state aligns with and further supports the hybrid B-Ir nature of the IFS proposed in this study.

The spectral appearance of the IPSn=1 peak also presents a spatial modulation across borophene stripes, as shown in the dI/dV plot in Fig. 5b. It consists of an apparent, periodic widening of the dI/dV signal, based on a varying peak substructure, that becomes maximal (minimal) at each stripe (in-between stripes). This is exemplarily represented by the constant-bias profile selected in Fig. 5b and superimposed on the STM image in Fig. 5a. We hypothesize that this phenomenon results from a variation of the local work function at stripe regions, which would yield two peaks at slightly different voltages. These may appear convoluted to the non-shifted peak due to the large STS probing area (radius of 10—15 Å2) at the elevated bias voltage and tip-sample distance that includes contributions from both stripe and in-between stripe regions. Such an averaging effect has been observed in similar metal-supported 2D material systems40,41,59. Indeed, local work function estimations along the same profile present a spatial modulation that reaches minimum values in between stripes, and maximum values on the stripes (Fig. S15). These were extracted by fitting the energy positions of IPSn>1 peaks, of spectra presented in Fig. 5b, to the Gundlach relation38,60. This behavior is consistent with calculated local work function variations ΔΦ, reported in Fig. 5a, which also present a periodic reduction (up to 0.5 eV) in-between stripes. Note that the reduction of the work function is more pronounced at the regions of smallest apparent borophene—Ir(111) distance (i.e., in-between stripes), consistent with the overall trend that the Ir(111) work function reduces upon positioning a borophene layer in its proximity (Fig. 2a).

To further validate the hypothesis of a work function driven origin of the IPS’s spatial modulation, our results are compared with the prototypical example of graphene on metals. Three effects have been previously observed that could justify a spatial modulation IPSs’ spectral weight observed by STS: (i) splitting of IPSs, (ii) quantum confinement effects or (iii) local modulation of the work function. Effect (i) was interpreted as the fingerprint of graphene retaining its free-standing properties56. However, this is not compatible with the present case, as the wavefunctions of the anti-symmetric IPSs present a peak extending further into vacuum than the symmetric ones at higher energies. Lateral confinement effects due to reduced extension of borophene domains61 (ii) can also be ruled out. The IPS’s modulation is present in extended borophene domains, and no alterations were observed even for domains with widths as narrow as two stripes. Therefore, modulation of the electronic properties (iii) beyond the IPSs shall be investigated, as the calculated IPSs’ wavefunctions do not show any spatial localization that seems correlated with the bright stripes in the STM. In the case of graphene, variations of the local work function have been shown to be driven by a non-commensurate registry between graphene and substrate, giving rise to varying STM appearances observable as moiré patterns53.

For borophene on Ir(111), different positions of B atoms with respect to atoms of the Ir layers lead to a modulation of the interaction registry, as shown in Fig. 5a, with closer atoms interacting more strongly. This is expressed through a stronger modification of the charge density (Figs. S16 vs Fig. 5a) compared to free-standing borophene and bare Ir(111). A local variation of charge transfer with respect to the average value is expected at those sites with stronger B-Ir bonds, which in turns generate a local modification of the work function (Fig. 5a), which modulates the localization of the IPSs.

Hence, the matching spatial variations of interfacial charge transfer and local work function are fingerprints of a different interaction strength between Ir and B atoms that depend on their registry. This position-dependence also causes the spatial modulation of the hybrid interfacial states, the superposition of which leads to the IFS spectral feature detected on borophene.

Finally, we discuss the connection between the observed IPS/IFS states and the presence of a single borophene polymorph. Because of the similarity between the characteristic features calculated for two different arrangements of B atoms, both identifiable as χ6 polymorph, we argue that the formation of the peculiar hybrid and interfacial states stems from the interaction strength between Ir and B atoms. Therefore, we infer that any borophene polymorph would be similarly characterized, ruling out any major electronic driving forces behind the stabilization of a single borophene polymorph. As a consequence, the epitaxial growth of χ6 borophene alone should be explained by the role of the geometrical registry, e.g. a more effective reduction of strain for the χ6 polymorph or a better matching with the symmetry of the substrate.

Conclusion

In summary, the complex interfacial interactions characterizing the formation of a single borophene polymorph on Ir(111) have been unveiled through a combined experimental and computational study. We report the emergence of an IFS with hybrid borophene—Ir character, visible as a low-energy resonance in STM spectroscopic measurements and rationalized as an energy-localized state of B and Ir atoms origin by DFT calculations. We also disclose the presence of hybrid and resonant IPSs, representing a linear combination of borophene IPSs with Ir(111) surface states, never observed to date. Such a scenario in which the interfacial interactions are largely dominated by hybrid states is also shown to be present in χ6 polymorphs with alternative arrangement of B atoms, which suggest that their origin resides in the strong interaction between Ir and borophene rather than in their particular stacking geometry. This work thus contributes to the ongoing efforts to understand and harness borophene, as well as, more broadly, other substrate-stabilized atomically thin 2D materials.

Methods

Borophene with sub-monolayer coverage (θ < 1) was grown on Ir(111) by ultra-high vacuum CVD, typically dosing 0.08 L of diborane onto the substrate kept at temperatures between 1073 K and 1213 K. Additional information on the CVD method followed here can be found elsewhere22. The Ir(111) substrate consisted of a single-crystal that was prepared by repeated cycles of sputtering by 1 keV Ar+ ions and resistive annealing at 1233 K.

STM and STS experiments were carried out in situ in a CreaTec STM held at 6 K and a pressure < 1 × 10−10 mbar, using an electrochemically etched tungsten tip. STM images were acquired using constant current mode, at the setpoints and sample bias voltages stated in the figure captions. Atomically-resolved STM images of the clean Ir(111) surface were used for calibration. dI/dV spectra and maps were acquired in constant current mode at the setpoint and bias voltage V stated in the figure captions, using a lock-in amplifying technique, operating at f = 1315 Hz and Vp-p = 50 mV. Images were processed using the WsXM software62 and spectra were processed by custom-made IGOR Pro procedures.

The ab-initio calculations were carried out through the Quantum ESPRESSO suite63,64, using the PBE exchange-correlation functional and ultrasoft pseudopotentials with a 43/325 Ry cutoff for the plane-waves basis set for the wavefunction and the charge density, respectively. The dispersion interactions were included through the Grimme-D3 pairwise correction65.

We assumed the borophene on Ir(111) geometries as the two most stable ones proposed by Vinogradov et al.,24; however, the atomic coordinates were rescaled in order to respect the equilibrium lattice constant of Ir atoms with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional and we extended the Ir(111) slab in order to include up to six layers. The reciprocal space of such a supercell was mapped with a 2×6×1 Monkhorst-Pack set of k-points. In order to correctly decouple the wavefunctions of the two sides of the slab, an enlarged vacuum region of at least 50 Å was inserted. The STM images were simulated through the Tersoff-Hamann approach66.

In order to facilitate the comparison of the band structure of borophene on Ir(111) with that of the pristine Ir(111), keeping track of the surface states, we performed the unfolding67,68 of the eigenstates from the Brillouin zone of the larger cell of borophene free-standing or borophene on Ir(111) into that of the unit cell of the pristine Ir(111) surface, using the unfold code69.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Boustani, I. New quasi-planar surfaces of bare boron. Surf. Sci. 370, 355–363 (1997).

Tang, H. & Ismail-Beigi, S. Novel precursors for boron nanotubes: the competition of two-center and three-center bonding in boron sheets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 115501 (2007).

Gonzalez Szwacki, N., Sadrzadeh, A. & Yakobson, B. I. B80 fullerene: an ab initio prediction of geometry, stability, and electronic structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 166804 (2007).

Zhang, Z., Yang, Y., Gao, G. & Yakobson, B. I. Two-dimensional boron monolayers mediated by metal substrates. Angew. Chem. 127, 13214–13218 (2015).

Feng, B. et al. Experimental realization of two-dimensional boron sheets. Nat. Chem. 8, 563–568 (2016).

Mannix, A. J., Zhang, Z., Guisinger, N. P., Yakobson, B. I. & Hersam, M. C. Borophene as a prototype for synthetic 2d materials development. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 444–450 (2018).

Xenes: 2D Synthetic Materials Beyond Graphene; Molle, A., Grazianetti, C., Eds., https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823824-0.00020-4. (Woodhead Publishing, 2022).

Feng, B. et al. Discovery of 2D anisotropic dirac cones. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704025 (2018).

Lian, C. et al. Integrated plasmonics: broadband dirac plasmons in borophene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 116802 (2020).

Mortazavi, B., Rahaman, O., Dianat, A. & Rabczuk, T. Mechanical responses of borophene sheets: a first-principles study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 27405–27413 (2016).

Zhang, Z., Yang, Y., Penev, E. S. & Yakobson, B. I. Elasticity, flexibility, and ideal strength of borophenes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1605059 (2017).

Tang, H. & Ismail-Beigi, S. Self-doping in boron sheets from first principles: a route to structural design of metal boride nanostructures. Phys. Rev. B 80, 134113 (2009).

Penev, E. S., Bhowmick, S., Sadrzadeh, A. & Yakobson, B. I. Polymorphism of two-dimensional boron. Nano Lett. 12, 2441–2445 (2012).

Tsafack, T. & Yakobson, B. I. Thermomechanical analysis of two-dimensional boron monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 93, 165434 (2016).

Zhao, Y., Zeng, S. & Ni, J. Superconductivity in two-dimensional boron allotropes. Phys. Rev. B 93, 014502 (2016).

Wu, X. et al. Two-dimensional boron monolayer sheets. ACS Nano 6, 7443–7453 (2012).

Liu, X. et al. Geometric imaging of borophene polymorphs with functionalized probes. Nat. Commun. 10, 1642 (2019).

Kong, L. et al. One-dimensional nearly free electron states in borophene. Nanoscale 11, 15605–15611 (2019).

Kiraly, B. et al. Borophene synthesis on Au(111). ACS Nano 13, 3816–3822 (2019).

Wu, R. et al. Large-area single-crystal sheets of borophene on Cu(111) surfaces. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 44–49 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Atomic-resolution structural and spectroscopic evidence for the synthetic realization of two-dimensional copper boride. Sci. Adv. 11, eadv8385 (2025).

Cuxart, M. G. et al. Borophenes made easy. Sci. Adv. 7, eabk1490 (2021).

Omambac, K. M. et al. Segregation-enhanced epitaxy of borophene on Ir(111) by thermal decomposition of borazine. ACS Nano 15, 7421–7429 (2021).

Vinogradov, N. A., Lyalin, A., Taketsugu, T., Vinogradov, A. S. & Preobrajenski, A. Single-phase borophene on Ir(111): formation, structure, and decoupling from the support. ACS Nano 13, 14511–14518 (2019).

Preobrajenski, A. B., Lyalin, A., Taketsugu, T., Vinogradov, N. A. & Vinogradov, A. S. Honeycomb boron on Al(111): from the concept of borophene to the two-dimensional boride. ACS Nano 15, 15153–15165 (2021).

Radatović, B. et al. Macroscopic single-phase monolayer borophene on arbitrary substrates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 21727–21737 (2022).

Tognolini, S. et al. Rashba spin-orbit coupling in image potential states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 046801 (2015).

Tognolini, S. et al. On- and off-resonance measurement of the image state lifetime at the graphene/Ir(111) interface - astrophysics data system. Surf. Sci. 679, 11–16 (2019).

Pagliara, S. et al. Nature of the surface states at the single-layer graphene/Cu(111) and graphene/polycrystalline-Cu interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 91, 195440. (2015).

Lin, Y. et al. Excitation and characterization of image potential state electrons on quasi-free-standing graphene. Phys. Rev. B 97, 165413 (2018).

Armbrust, N., Güdde, J. & Höfer, U. Formation of image-potential states at the graphene/metal interface. N. J. Phys. 17, 103043 (2015).

Tognolini, S. et al. Surface states resonances at the single-layer graphene/Cu(111) interface. Surf. Sci. 643, 210–213 (2016).

Järvinen, P. et al. Field-emission resonances on graphene on insulators. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 23951–23954 (2015).

Jugovac, M. et al. Coupling borophene to graphene in air-stable heterostructures. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2300136 (2023).

Kamal, S. et al. Unidirectional nano-modulated binding and electron scattering in epitaxial borophene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 57890–57900 (2023).

Omambac, K. M. et al. Interplay of kinetic limitations and disintegration: selective growth of hexagonal boron nitride and borophene monolayers on metal substrates. ACS Nano https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c04038. (2023).

Hinaut, A. et al. Superlubricity of borophene: tribological properties in comparison to hBN. ACS Nano https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5c11587 (2025).

Gundlach, K. H. Theory of metal-insulator-metal tunneling for a simple two-band model. J. Appl. Phys. 44, 5005–5010 (1973).

Echenique, P. M. & Uranga, M. E. Image potential states at surfaces. Surf. Sci. 247, 125–132 (1991).

Borca, B. et al. Potential energy landscape for hot electrons in periodically nanostructured graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 036804 (2010).

Schulz, F. et al. Epitaxial hexagonal boron nitride on Ir(111): a work function template. Phys. Rev. B 89, 235429 (2014).

Liu, X., Wang, L., Yakobson, B. I. & Hersam, M. C. Nanoscale probing of image-potential states and electron transfer doping in borophene polymorphs. Nano Lett. 21, 1169–1174 (2021).

Dougherty, D. B. et al. Tunneling spectroscopy of Stark-shifted image potential states on Cu and Au surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 76, 125428 (2007).

Derry, G. N., Kern, M. E. & Worth, E. H. Recommended values of clean metal surface work functions. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 33, 060801 (2015).

Dal Corso, A. Clean Ir(111) and Pt(111) electronic surface states: a first-principle fully relativistic investigation. Surf. Sci. 637, 106–115 (2015).

Henkelman, G., Arnaldsson, A. & Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 354–360 (2006).

theory.cm.utexas.edu/henkelman/code/bader/. https://theory.cm.utexas.edu/henkelman/code/bader/ (accessed 2025-07-25).

Manz, T. A. & Limas, N. G. Introducing DDEC6 atomic population analysis: part 1. Charge partitioning theory and methodology. RSC Adv. 6, 47771–47801 (2016).

Limas, N. G. & Manz, T. A. Introducing DDEC6 atomic population analysis: part 2. Computed results for a wide range of periodic and nonperiodic materials. RSC Adv. 6, 45727–45747 (2016).

Program Computing DDEC Atomic Charges. SourceForge. https://sourceforge.net/projects/ddec/ (accessed 2025-07-25).

Zhang, H. G. et al. Graphene based quantum dots. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 302001 (2010).

Garcia-Lekue, A. et al. Spin-dependent electron scattering at graphene edges on Ni(111). Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 066802 (2014).

Wang, B., Caffio, M., Bromley, C., Früchtl, H. & Schaub, R. Coupling epitaxy, chemical bonding, and work function at the local scale in transition metal-supported graphene. ACS Nano 4, 5773–5782 (2010).

Bignardi, L. et al. Determining the atomic coordination number in the structure of Β12 borophene on Ag(111) via X-ray photoelectron diffraction analysis. Surf. Interfaces 51, 104791 (2024).

Varykhalov, A. et al. Ir(111) surface state with giant Rashba splitting persists under graphene in air. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 066804 (2012).

Bose, S. et al. Image potential states as a quantum probe of graphene interfaces. N. J. Phys. 12, 023028 (2010).

Pagliara, S. et al. Nature of the surface states at the single-layer graphene/Cu(111) and graphene/polycrystalline-Cu interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 91, 195440 (2015).

Cuxart, M. G. et al. Spatial segregation of substitutional B atoms in graphene patterned by the Moiré Superlattice on Ir(111). Carbon 201, 881–890 (2023).

Rienks, E. D. L. Surface potential of a polar oxide film: FeO on Pt(111). Phys. Rev. B 71, 241404 (2005).

Gundlach, K. H. Zur Berechnung Des Tunnelstroms Durch Eine Trapezförmige Potentialstufe. Solid-State Electron 9, 949 (1996).

Craes, F. et al. Mapping image potential states on graphene quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 056804 (2013).

Horcas, I. et al. WSXM: a software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 78, 013705 (2007).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Quantum espresso: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Tersoff, J. & Hamann, D. R. Theory of the scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. B 31, 805–813 (1985).

Popescu, V. & Zunger, A. Extracting E versus k Effective Band Structure from Supercell Calculations on Alloys and Impurities. Phys. Rev. B 85, 085201 (2012).

Medeiros, P. V. C., Stafström, S. & Björk, J. Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic perturbations on the electronic structure of graphene: retaining an effective primitive cell band structure by band unfolding. Phys. Rev. B 89, 041407 (2014).

Bonfà, P. Unfold-x, https://bitbucket.org/bonfus/unfold-x/src/master/.

Acknowledgements

A.U. thanks Dr. P. Bonfà (University of Parma), for the fruitful discussion on the band unfolding software. D.P. and C.D.V. acknowledge funding from the European Union—NextGenerationEU through the Italian Ministry of University and Research under PNRR—M4C2I1.4 ICSC—Centro Nazionale di Ricerca in High Performance Computing, Big Data and Quantum Computing (Grant No. CN00000013). M. G. C. acknowledges funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 892725 (WHITEMAG project), and financial support of MCIN with funding from European Union NextGenerationEU (PRTR-C17.I1) and Generalitat de Catalunya. The ICN2 is funded by the CERCA programme and Generalitat de Catalunya.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G.C. and W.A. conceived the study. M.G.C. carried out the experiments and analyzed the experimental data. A.U. conducted the calculations with support from D.P. W.A. and C.D.V. developed the infrastructure. M.G.C. and A.U. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ugolotti, A., G. Cuxart, M., Perilli, D. et al. Hybrid and resonant states originated by the stabilization of borophene’s single χ6 polymorph on Ir(111). npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 112 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00631-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00631-8