Abstract

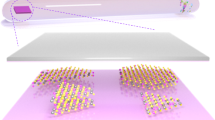

Layered metal-rich chalcogenides are a new class of two-dimensional (2D) materials consisting of densely packed metal layer units separated by van der Waals (vdW) gaps, yet their physical properties remain unexplored, particularly on phonon vibrational modes. Here, we report the phonon vibrational characteristics of 2D metal-rich Ta2Se chalcogenide through Raman spectroscopy and density functional perturbation theory (DFPT) calculations. Highly c-axis-oriented single crystalline Ta2Se flakes were grown using the arc-melting process. Temperature-dependent electrical resistivity and Hall-effect measurements on Ta2Se reveal a metallic electrical ground state with a high hole carrier concentration (~2 × 1021 cm−3). Raman spectroscopy identifies two distinct peaks at 184 cm−1 and 213 cm−1, which remain invariant in both thick (145 nm) and thin (11.68 nm) samples, indicating robust phonon vibrations down to 12 layers. Based on DFPT calculations and polarized Raman experiments, we confirm that both peaks correspond to A1g Raman-active modes oscillating along the c-axis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) are among the most extensively studied materials in the 2D materials family1,2,3,4. Anisotropic and weak van der Waals (vdW) interlayer interactions enable easy exfoliation into atomically thin layers, which derives unexpected physicochemical properties from quantum confinement effects5,6,7,8. Additionally, the combinations of transition metals and chalcogen elements allow the formation of various types of TMDs with versatile physical properties, such as Weyl semi-metallic state or topological phases, thereby expanding recent studies from their intrinsic properties to the applicability of the materials9,10. However, most TMDs are limited to MX2 compositions with hexagonal or trigonal symmetry, where M denotes a transition metal and X represents a chalcogen element11,12,13. To explore new physical phenomena and broaden potential applications, it is essential to investigate alternative 2D TMDs with diverse compositions and symmetries. In this context, transition metal-rich chalcogenides (TMRCs) are worth drawing attention due to their unique compositions and different symmetries14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Their densely packed transition metal-rich layers between chalcogen layers can lead to intriguing physical properties, such as mimicking high-pressure behavior at ambient pressure or even turning into an electride form21,22.

Among the 2D TMRCs, Ta2Se exhibits a distinct structure and symmetry, setting it apart from traditional MX2 TMDs. Harbrecht et al. first reported the synthesis of Ta2Se, which features densely packed four-layer Ta units between Se layers with tetragonal symmetry, based on X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies23. Recently, the emergence of superconductivity in Ta2Se polycrystals has also been reported at approximately 3.8 K, suggesting that van Hove singularities in the d-band, associated with high density-of-states, may contribute to the superconducting behavior24. Despite these findings, fundamental research on Ta2Se, including its phonon vibrational modes, remains limited, hindering a complete understanding of its optical properties mainly owing to the lack of a high quality single crystal sample enabling layered exfoliation.

In this paper, we identified the phonon vibrational modes of 2D metal-rich Ta2Se chalcogenide through Raman spectroscopy and density functional perturbation theory (DFPT) calculations. Single-crystalline Ta2Se flakes oriented along the ab-plane were successfully grown via the arc-melting process. Temperature (T)-dependent electrical resistivity (ρ) and Hall-effect measurements confirm that the Ta2Se crystal has a metallic electrical ground state with a high hole carrier concentration near 2 × 1021 cm−3. Raman spectroscopy in backscattering geometry revealed two distinct, invariant peaks at 184 cm−1 and 213 cm−1 in both thick (145 nm) and thin (11.68 nm) samples, indicating stable vibrational modes that remain unchanged down to 12 layers. DFPT calculations and polarized Raman experiments confirmed that both peaks originate from A1g Raman-active modes oscillating along the c-axis.

Results

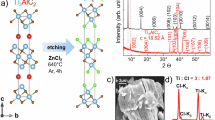

Figure 1a illustrates the crystal structure of Ta2Se, which has a layered tetragonal structure with point group D4h and space group P4/nmm. The tantalum (Ta) atoms are arranged in two body-centered cubic structures between the selenium (Se) layers, separated by vdW gaps23,24. The thickness of the Se-Ta2-Ta1-Ta1-Ta2-Se layer unit is 7.207 Å, while the vdW gap distance is 2.625 Å22,23, which is slightly shorter than in other TMDs, suggesting a relatively strong interlayer interaction between layer units. Our Ta2Se crystal grows as large as ~0.5 × 1 mm2 in a bulk flake form, as shown in Fig. S1. Because of the weak vdW bonding, the Ta2Se crystal can be easily exfoliated along the ab-plane direction using 3 M Scotch tape. Figure 1b shows the clean cleaved surface of the crystal before and after the exfoliation process. As shown in Fig. 1c, the measured XRD pattern exhibits only (00l) peaks (l = integer), confirming that the Ta2Se crystal is well-oriented along the ab-plane without impurities. Figure 1d shows the energy dispersive X-ray spectrum (EDS) results, verifying that the chemical stoichiometry is Ta:Se = 2:1.

a Crystal structure showing a layered tetragonal arrangement of Ta1, Ta2, and Se atoms. b Optical microscopy images of the Ta2Se single crystal surface before and after exfoliation. c XRD pattern of the Ta2Se single crystal exhibiting only (00l) plane peaks. d EDS spectrum confirming the atomic ratio of Ta:Se = 2:1.

To evaluate the electrical properties, the clean surface of Ta2Se was attached to the patterned electrodes with a van der Pauw (vdP) configuration using a stamping method25. Figure 2a illustrates a schematic of the stamping process for connecting the patterned vdP electrode to the Ta2Se single crystal. This method enables Hall-effect measurement on Ta2Se from 4 to 300 K. As shown in Fig. 2b, the ρ decreases with decreasing T, yielding a residual resistivity ratio (RRR) of 5.77. The RRR is defined as the ratio of the ρ at room T (300 K) to that at a low T (4 K). This value indicates a higher sample purity compared to polycrystalline samples containing impurities (~3)24. The positive Hall voltage confirms that the majority carrier in Ta2Se is a hole. The hole concentration (nh) is estimated to be 2.37 × 1021 cm−3 at 300 K and 2.21 × 1021 cm−3 at 4 K (Fig. 2c), demonstrating T-independent behavior. Accompanied with the temperature-dependent ρ, this strongly supports the metallic ground state nature of Ta2Se. In Fig. 2d, the carrier mobility increases as the T decreases, indicating that electron–phonon interactions dominate the carrier transport26.

a Schematic of the sample preparation process for measuring electrical transport. Patterned Ti (10 nm)/Au (50 nm) electrodes were deposited on Si/SiO2 substrates. A freshly exfoliated Ta2Se single crystal with a clean surface was attached to 3 M tape and then transferred onto the designated patterned electrode. b–d T-dependent ρ, nh, and μH properties of single-crystalline Ta2Se.

Figure 3a–f shows the characterization of thin and thick-layered Ta2Se samples prepared on 300 nm SiO2 substrates using Nitto tape. The sample thickness was first estimated based on optical contrast observed in microscopy images (Fig. 3a, b), where the thinner sample appears more transparent, whereas the thicker sample appears darker with a metallic sheen. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements confirmed the thickness of the thin and thick samples as 11.68 nm and 145 nm, respectively (Fig. 3c, d). Given the unit thickness of two Se and four Ta layers (7.207 Å) and the vdW gap distance (2.625 Å), these values correspond to 12 and 147 layers, respectively23. Raman spectroscopy was performed immediately after exfoliation to minimize exposure to ambient conditions. The thin (12-layer) sample exhibits Raman peaks at 184.2 cm−1 and 213.4 cm−1 with an intensity ratio of 0.554 (Fig. 3e), while the thick (147-layer) sample shows peaks at 184.2 cm−1 and 212.2 cm−1 with an intensity ratio of 0.593 (Fig. 3f). The near-invariance of the Raman frequency and intensity ratio suggests a weakly sensitive feature to interlayer coupling in Ta2Se. Although our results show no significant Raman frequency change across the 10–200 nm thickness range, systematic investigations on monolayer and few-layer Ta2Se are still necessary to reveal possible thickness-dependent behavior in the ultrathin limit, while a few-layer level exfoliation is challenging owing to a strong interlayer interaction. To prevent sample damage, the Raman spectra of the thin (12-layer) sample were acquired using a lower laser power (~0.5 mW), while the thick (147-layer) sample was measured at ~8 mW. When the laser power exceeded ~0.95 mW for the thin sample and ~10 mW for the thick sample, oxidation occurred, leading to the appearance of a broad Ta2O5-related peak around 240 cm−1 (Fig. S2a–d). Furthermore, temperature-dependent Raman measurements showed that both Ta₂Se modes shift uniformly with the Si substrate peak. This indicates that the observed shifts mainly originate from thermal strain, rather than from intrinsic anharmonic or electron–phonon coupling effects (Fig. S3).

To further understand these Raman modes, the phonon branches of Ta2Se are determined by the point group symmetry and Wyckoff positions of atoms27,28. Wyckoff positions define the coordinates within the unit cell that remain invariant under symmetry operations. In Ta2Se, the two types of Ta1 and Ta2, occupy the 2c Wyckoff position at (0.25, 0.25, 0.7553) and (0.25, 0.25, 0.0776), respectively, as shown in Fig. S423. The Se atom also resides at the 2c Wyckoff position with coordinates (0.25, 0.25, 0.3665), as depicted in the same figures23. The designation ‘2c’ indicates that these positions have a multiplicity of two within the primitive unit cell. Consequently, with three such positions occupied (Ta1, Ta2, and Se), there are six atoms in the unit cell, leading to a total of 18 phonon modes. Furthermore, the D4h point group, with symmetric elements C4, C2, C2′, σh, σv, σd, i, S4, and E (Fig. S4c), determines the phonon branches at the Γ point27,28. Based on the Wyckoff positions of these three atoms and the D4h point group, the irreducible representation is expressed as28

This decomposition accounts for 15 optical and 3 acoustic phonon branches at the Γ point, exhibiting doubly degenerated Eg and Eu phonon branches. Among the optical phonon branches, the 3A1g and 3Eg modes are Raman active modes, whereas the 2A2u and 2Eu modes are infrared (IR)-active27. Phonon calculation at the Γ point of the Brillouin zone was performed using DFPT calculations to identify the vibrational Raman modes corresponding to each peak, as shown in Fig. 4. Our calculations confirmed the presence of six Raman-active modes: three A1g modes located at 92.3, 183.5, and 213.2 cm−1, and three Eg modes at 41.3, 146.9, and 190.2 cm−1. Additionally, we identified four IR-active modes, consisting of two Eu modes at 66.6 cm−1 and 163.6 cm−1, and two Au modes at 156.5 cm−1 and 179.9 cm−1. The analysis also revealed two acoustic phonon modes, classified as A2u and Eu modes (Fig. S5a). Based on our theoretical calculations, the measured Raman modes at 184.2 cm−1 and 212.2 cm−1 originated from A1g modes. DFPT-calculated Raman tensors (Table S1) reveal that these A1g modes exhibit characteristic tensor patterns with αxx ≈ αyy and negligible off-diagonal elements, consistent with tetragonal symmetry and pure A1g character. The calculated depolarization ratios of 0.110 and 0.087 for the 183.5 cm−1 and 213.2 cm−1 modes, respectively, confirm their highly polarized natures. The A1g mode at 183.5 cm−1 involves Ta1 and Se atoms vibrating in the same out-of-plane direction, while Ta2 atoms vibrate in the opposite direction. In contrast, the A1g mode at 213.2 cm−1 shows Ta2 and Se atoms vibrating in the same out-of-plane direction, while Ta1 atoms vibrate in the opposite direction. Because Ta1, Ta2, and Se all occupy 2c Wyckoff positions with 4mm site symmetry in P4/nmm, the Γ-point vibrational modes separate by symmetry into purely in-plane Eg and purely out-of-plane A1g characters. DFPT calculations confirm that all A1g modes (92.3, 183.5, 213.2 cm⁻¹) have only c-axis displacement components, whereas all Eg modes are purely in-plane, as visualized in Fig. 4. For the other Raman-active modes, although they appear in the calculated Raman spectrum (S5b), they are not observed experimentally. The calculated Raman tensors (Table S1) explain this observation: all Eg modes exhibit depolarization ratios of exactly 0.75 and dominant off-diagonal tensor elements (|αxz|, |αyz| ≫ |αxx|, |αyy|), making them effectively forbidden in backscattering geometry where only in-plane polarization components are accessible.

Polarized Raman experiments were conducted on the surface of our Ta2Se crystal to further confirm the identification of Raman active modes. The Raman selection rules allow us to derive the Raman intensity as \(I\propto {|{\sum }_{j}{e}_{s}\cdot {R}_{j}\cdot {e}_{i}|}^{2}\), where \({R}_{j}\) is the Raman tensor, and \({e}_{i}\) (\({e}_{s}\)) is the polarization unit vectors of the incident (scattered) laser beams27,29. The symmetry of the crystal structure determines the Rj, and the component of the Rj can be derived from the change in the polarizability of the crystal as the atoms vibrate. The Rj’s of the D4h point group are listed in Table 1. Each Raman vibration mode can be categorized according to its symmetry properties of Ta2Se. The coordinate system is fixed as the laboratory coordinate system (x, y, z) to unify the sample (a, b, c) and the coordinate system (x, y, z). The experimental setup used backscattering geometry, with the incident laser propagating along the –z direction and the scattered laser propagating toward the +z direction (see Figs. 5a and 6a). The unit vector describes the polarization of the incident light propagating along the –z direction given by \({e}_{i}={\left(\cos \theta \,\sin \,\theta \,0\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\), where \(\theta\) is the incident polarization angle. In this setup, the polarizer is aligned along the y-axis, setting \(\theta\) to 90°. An analyzer is placed between the half-wave plate and the spectrometer to filter the scattered light by its polarization component. The parallel (∥) polarization analyzer is set as \({e}_{s}^{\parallel }\) = (0 1 0) by polarizing along the y-axis. The perpendicular (⊥) analyzer is polarized along the x-axis and represented as \({e}_{s}^{\perp }\) = (1 0 0) with the analyzer’s angle set to 0°. The parallel (∥) and perpendicular (⊥) polarization configurations are represented by Porto’s notation as \(\bar{Z}\left({YY}\right)Z\) and \(\bar{Z}\left({YX}\right)Z\), respectively. These notations align the laboratory coordinate system (x, y, z) with the crystallographic axes (a, b, c).

a Schematic of the polarized Raman spectroscopy configuration, which includes the half-wave plate located in front of the analyzer. b Incident and c scattered polarization direction configurations for perpendicular and parallel analyzer polarizations, respectively. The black lines indicate the x and y axes, while the red and blue lines represent the incident and scattered polarization directions, respectively. Color and polar plots of the polarized Raman intensities for the configurations in d perpendicular and e parallel orientations, following method 1. Theoretical fitting curves are marked as red ones in polar plots.

a Schematic of the polarized Raman spectroscopy configuration, which includes the half-wave plate located between the filter and microscope. b Incident and c scattered polarization directions on the Ta2Se microscopy image, corresponding to perpendicular and parallel analyzer polarizations, respectively. The black lines indicate the x and y axes, while the red and blue lines represent the incident and scattered polarization directions, respectively. Color and polar plots of the polarized Raman intensities for the configurations in d perpendicular and e parallel orientations, following method 2. Theoretical fitting curves are marked as red ones in polar plots.

In Fig. 5a, the experimental setup (method 1) for polarized Raman spectroscopy places the half-wave plate in front of the analyzer. The laser passes sequentially through the polarizer, sample, half-wave plate, and analyzer. The incident beam is polarized along the y-axis by fixing the angle θ at 90° and propagates to the sample. The scattered beam passes through the half-wave plate, and its polarization state is transformed to an angle α relative to the y-axis, with the fast axis of the half-wave plate rotated by α/2. The Jones matrix for the half-wave plate is given as30

Then, the Raman intensity of method 1 is given as

where \({R}_{j}\) are the Raman tensors associated with the Raman-active modes of the D4h point group, as given in Table 1. Figures 5b and 5c show the polarization directions for the parallel (∥) and perpendicular (⊥) analyzer configurations of method 1, respectively. For both configurations, the incident beam polarization vector is \({e}_{i}={\left(010\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\), corresponding to y-axis polarization. The parallel (∥) analyzer is represented as \({e}_{s}^{\parallel }=(0\,1\,0)\), while the perpendicular (⊥) analyzer is represented as \({e}_{s}^{\perp }=(1\,0\,0)\). Both configurations of scattered beam polarization are affected by the half-wave plate, which is rotated according to each analyzer’s polarization axis. Using this Raman intensity equation, we calculated the Raman intensities for the different Raman-active modes in Table 2.

Figure 5d shows the polarized Raman intensities at 183 cm−1 and 212 cm−1, following the perpendicular (⊥) polarization configuration in Fig. 5b. The intensities exhibit two-fold symmetry in both the color and polar plots, reaching maximum intensity at 104° and 284° relative to the x-axis polarization, with a 180° periodicity. As shown in Fig. 5d, the polar plots for 183 cm−1 and 212 cm−1 align well with the calculated Raman intensities for the A1g and B1g modes listed in Table 2. The color plot in Fig. 5e, following the parallel (∥) configuration, shows maximum intensities with a 180° periodicity along the y-axis polarization. The polar plots in Fig. 5e show maximum intensities at 14° and 194°, which also align with the calculated intensities for A1g and B1g modes in Table 2, similar to the perpendicular analyzer results. The observed two-fold symmetry and 180° periodicity in the polar plots correspond to the symmetry properties of the A1g and B1g modes under the D₄h point group, as described by the Raman selection rules. Both the perpendicular (⊥) and parallel (∥) results exhibit a 14° tilt relative to the calculated intensities. This deviation may be attributed to a slight misalignment of polarization direction relative to the crystal orientation of the sample. Based on this polarized Raman spectroscopy configuration, the peaks at 183 cm−1 and 212 cm−1 can be predicted as A1g or B1g Raman-active modes.

In the same manner, Fig. 6a illustrates the experimental setup for method 2, where the beam sequentially passes through the polarizer, half-wave plate, sample, second half-wave plate, and analyzer. Following this configuration, Figs. 6b and 6c show the incident and scattered polarizations, which are varied by the polarizer, half-wave plate, and analyzer. For both perpendicular and parallel beam polarization directions, as shown in Figs. 6b and 6c, the incident and scattered beam polarization angles differ from 90° and 0°, respectively. The incident beam polarization is adjusted to an angle β based on the y-axis, causing the fast axis of the half-wave plate to rotate by β/2. The scattered beam polarization is determined by the analyzer and the half-wave plate, which are rotated by an angle β based on the x- (⊥) and y-axis (∥). The incident beam polarization vector is \({e}_{i}={\left(0\,1\,0\right)}^{{\rm{T}}}\), corresponding to y-axis polarization. The parallel (∥) analyzer is represented by \({e}_{s}^{\parallel }=(0\,1\,0)\) while the perpendicular (⊥) analyzer is represented by \({e}_{s}^{\perp }=(100)\). Using both the incident and scattered unit polarization vectors, the Raman intensities are calculated according to the following relation:

The calculated Raman intensities of method 2 are listed in Table 3. Figures 6d and 6e show the normalized Raman intensities at 183 cm−1 and 212 cm−1 measured from configuration 2, depending on different polarized angles. As shown in Fig. 6d, the color and polar plots for perpendicular (⊥) polarization in configuration 2 show no Raman intensity in the measured frequency range. In contrast, the color and polar plots for parallel (∥) polarization (Fig. 6e) show Raman intensities in the measured frequency range, consistent with the Raman tensor calculations in Table 3. These results confirm that the Raman peaks at 183 and 212 cm⁻¹ correspond to two distinct A1g Raman-active modes, as predicted by the symmetry and selection rules of the D₄h point group. The well-agreement between experimental polarization behavior and DFPT-calculated tensor elements (Table S1) validates the mode assignments, with both modes showing the characteristic A1g tensor pattern of dominant diagonal elements and negligible off-diagonal coupling. In addition, we also note that B1g mode is intrinsically forbidden in 4mm site symmetry exhibiting C4 rotational and σv mirror symmetry where x2-y2 becomes variant as shown like Fig. S4 and Table S2. As a result, the good agreement between the experimental results in Figs. 6d and 6e and the calculated Raman intensities in Table 3 finally confirms that the Raman peaks at 183 cm−1 and 212 cm−1 are assigned to the A1g Raman-active modes.

In summary, we successfully synthesized the single crystalline Ta2Se flakes and characterized the phonon vibration modes of 2D metal-rich Ta2Se chalcogenide using polarized Raman spectroscopy and DFPT calculations. The metallic ground state, with a high hole concentration of about 2 × 1021 cm−3, was confirmed by T-dependent ρ and Hall-effect measurements. Raman spectroscopy revealed two distinct peaks around 184 cm−1 and 213 cm−1 in both thick (145 nm, 147-layer) and thin (11.68 nm, 12-layer) Ta2Se samples. The invariance of Raman frequency and peak ratio down to 12 layers is attributed to the strong interlayer coupling and robust lattice configuration of 2D Ta₂Se, which maintains the phonon vibration modes along the out-of-plane direction. Based on DFPT calculations and polarized Raman experiments, we finally confirmed that both peaks correspond to distinct A1g Raman-active modes oscillating along the c-axis. We anticipate that these results will provide a fundamental understanding of the optical dynamics in the 2D metal-rich chalcogenide family, as well as it initiates other impactful studies from the fundamental low dimensional physics to the various practical applications.

Methods

Single crystal growth

The Ta2Se single crystals were synthesized using a two-step process combining the melt solidification method and arc-melting methods. Initially, Ta powder (Alfa Aesar 99.99%) and Se powder (Alfa Aesar 99.99%) were mixed in a 2.1:1 stoichiometry ratio and pelletized in an evacuated silica tube. The pelletized sample was then heated at 400 °C for 48 h. After the first annealing, the sample was reground in a glove box and re-pelletized in a vacuum-sealed silica tube before being annealed at 900 °C for 24 h. The annealed sample was subsequently melted in an arc-melting process under an Ar atmosphere, reaching a high temperature of approximately 1500 °C. Single crystals were obtained by rapidly stirring the arc-melting tip while maintaining a current of 35 A for 1 min, followed by a gradual current reduction over 30 s. This arc-melting cycle was repeated three times by flipping the sample, resulting in single crystals with sizes ranging from μm to mm.

Single crystal characterization

The crystal structure was characterized by XRD measurement (MiniFlex 600, Rigaku), and the chemical composition was analyzed using SEM-EDS (SU8220, Hitachi). The thickness of the Ta2Se samples were measured by AFM (NX10, Park Systems). For Raman spectroscopy, the samples were transferred onto Si/SiO2 (300 nm) substrates using Nitto tape. Raman spectra were collected using a confocal Raman system (XperRAM-S, Nanobase) with a 532 nm excitation laser in backscattering geometry. A 100× objective lens focused the laser to a spot size of <1 μm. Measurements were taken with an 1800 gr/mm grating for 60 s (8 mW) for the thick sample and 20 s (0.5 mW) for the thin sample.

Electrical transport properties

T-dependent electrical properties of the single crystalline Ta2Se were measured using a vdP configuration with the stamping method. Hall-effect measurements were conducted over a T range from 4 K to 300 K. The measurement system included a current source (6220, Kithely), a nanovoltmeter (2182 A, Kithely), a helium compressor (CNA-11, Sumitomo), a closed-cycle cryostat, and a 1.2 T electromagnet (co-designed by I.V SOLUTION and Sungwoo Instruments).

Phonon modes calculations

The phonon modes were calculated by the Bilbao Crystallographic Server28, with input parameters including the P4/nmm space group and Wyckoff positions of irreducible atoms.

DFPT calculations

Quantum mechanical simulations were performed using the plane-wave basis sets of CASTEP code as implemented in the BIOVIA Materials Studio platform31. The bulk Ta2Se crystal was modeled and geometry optimized with a local density approximation (LDA) functional. To fully optimize the structure, the self-consistent function of 1.0 × 10−10 eV/atom and convergence tolerance of the force criteria of 0.01 eV/Å were employed. The k-point sampling was set by using an actual spacing of 0.02 Å−1, and the energy cut-off was 440 eV. The norm-conserving pseudopotential with Koelling-Harmon relativistic treatment was used for the entire calculation process. The proposed optimized bulk Ta2Se crystal has accordance with previous report (our result: a = b = 3.30 Å, c = 9.59 Å, \(\alpha\) = \(\beta\) = \(\gamma\) = 90°; reference: a = b = 3.37 Å, c = 9.82 Å, \(\alpha\) = \(\beta\) = \(\gamma\) = 90°)32. After geometry optimization, we calculated the phonon and Raman tensor using the linear response theory. The electric eigenvalue and phonon convergence tolerance were set as 1.0\(\,\times\) 10−10 eV/atom and 1.0 × 10−5 Å−3, respectively. To compare with experimental results effectively, we red-shifted our theoretical vibrational modes by 10 cm−1.

Polarized Raman measurement

Polarized Raman spectroscopy was performed using the same laser, grating, and objective lens as in the Raman measurements. Prior to the measurements, the a- and b-axes of the samples were aligned with the x- and y-axes of the laboratory coordinate system to prevent misalignment between the laser polarization and the sample. Both configurations (method 1 and method 2) used Porto’s notation as \(\bar{Z}\left({YY}\right)Z\) for parallel and \(\bar{Z}\left({YX}\right)Z\) for perpendicular polarization. The polarizer was set along the y-axis (90°), and the analyzer was positioned to detect the polarization of the scattered beam at 0° and 90° for the perpendicular and parallel configurations, respectively. The polarization angles (α, β) were adjusted by rotating the half-wave plate to α/2 and β/2, respectively. In method 1, only the scattered beam passes through the half-wave plate, while in method 2, both incident and scattered beams pass through the half-wave plate.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the finding are available within the paper and its supplementary information. The corresponding authors can also provide data upon reasonable request.

References

Ross, J. S. et al. Electrically tunable excitonic light-emitting diodes based on monolayer WSe2 p-n junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 268–272 (2014).

Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497–501 (2013).

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Lin, Y. C. et al. Single-layer ReS2: two-dimensional semiconductor with tunable in-plane anisotropy. ACS Nano 9, 11249–11257 (2015).

Ali, M. N. et al. Non-saturating magnetoresistance in WTe2. Nature 514, 205–208 (2014).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Two-dimensional atomic crystals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 10451–10453 (2005).

Shaukat, R. A., Tamim, A. M., Hwang, G. T. & Jeong, C. K. Humidity sensors using 2D and 3D nanomaterials: from materials selection to technological aspects. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 25, 123–140 (2024).

Qi, Y. et al. Superconductivity in Weyl semimetal candidate MoTe2. Nat. Commun. 7, 11038 (2016).

Li, P. et al. Evidence for topological type-II Weyl semimetal WTe2. Nat. Commun. 8, 2157 (2017).

Mattheiss, L. F. Band structures of transition-metal-dichalcogenide layer compounds. Phys. Rev. B 8, 3719–3740 (1973).

Wakabayashi, N., Smith, H. G. & Nicklow, R. M. Lattice dynamics of hexagonal MoS2 studied by neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. B 12, 659–663 (1975).

Yu, Y. et al. High phase-purity 1T′-MoS2- and 1T′-MoSe2-layered crystals. Nat. Chem. 10, 638–643 (2018).

Herle, P. S. & Corbett, J. D. The first metal-rich binary chalcogenides of the lanthanides: Dy2Te and Gd2Te. Inorg. Chem. 40, 1858–1864 (2001).

Weirich, T. E., Pöttgen, R. & Simon, A. Crystal structure of octatitanium triselenide, Ti8Se3. Z. Kristallogr. 211, 929–930 (1996).

Maggard, P. A. & Corbett, J. D. Sc5Ni2Te2: synthesis, structure, and bonding of a metal-metal-bonded chain phase, a relative of Gd3MnI3. Inorg. Chem. 38, 1945–1950 (1999).

Chen, L. & Corbett, J. D. Remarkable metal-rich ternary chalcogenides Sc14M3Te8 (M = Ru, Os). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 1170–1171 (2003).

Maggard, P. A. & Corbett, J. D. Sc9Te2: a two-dimensional distortion wave in the scandium-richest telluride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 838–843 (2000).

Hughbanks, T. Exploring the metal-rich chemistry of the early transition elements. J. Alloy. Compd. 229, 1–10 (1995).

Örlygsson, G. Synthesis and crystal structure of Zr2Te. Distinctions in bonding to isotypic Sc2Te and the relationship to the structures of congeneric Hf2Te and Zr2Se. Inorg. Chem. 38, 3377–3383 (1999).

Kang, S. H. et al. Water- and acid-stable self-passivated dihafnium sulfide electride and its persistent electrocatalytic reaction. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaba7416 (2020).

Yu, H. S. et al. Quasi-high-pressure effects in transition-metal-rich dichalcogenide, Hf3Te2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 25541–25546 (2017).

Harbrecht, B. Ta2Se: a tantalum-rich selenide with a new layer structure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 28, 1660–1662 (1989).

Gui, X. et al. Superconductivity in metal-rich chalcogenide Ta2Se. Inorg. Chem. 59, 5798–5802 (2020).

Lee, K., Kim, S. W., Toda, Y., Matsuishi, S. & Hosono, H. Dicalcium nitride as a two-dimensional electride with an anionic electron layer. Nature 494, 336–340 (2013).

Kittel, C. Introduction to Solid State Physics, 8th ed. (Wiley, 2005).

Dresselhaus, M. S. & Jorio, A. Group Theory: Application to the Physics of Condensed Matter (Springer, 2008).

Kroumova, E. et al. Bilbao crystallographic server: useful databases and tools for phase-transition studies. Phase Transit. 76, 155–170 (2003).

Hayes, W. & Loudon, R. Scattering of Light by Crystals 017 (Dover Publications, 2004).

Hecht, E. Optics, 5th edn (Pearson, 2017).

Clark, S. J. et al. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. Cryst. Mater. 220, 567–570. www.accelrys.com/references/castep/ (2005).

Nanjundaswamy, K. S. & Hughbanks, T. Subtleties of structure and bonding in Ta-S-Se and Ta-Nb-S solid solutions. J. Solid State Chem. 98, 330–343 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00401881, RS-2023-00214318, and RS-2023-00283500), and the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science (KRISS-GP2025-0005-02). It was also supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2024-00463479).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L. and H.M.O. conceived the study and designed the experiments. J.L. synthesized the samples and performed and analyzed the XRD, electrical, and optical measurements. J.L., H.B., and S.I. conducted the AFM measurements. J.L. and H.K. designed the polarized Raman spectroscopy, and J.L. carried out the measurements. J.Y. and S.M.L. performed and analyzed the DFPT calculations. B.L. performed the temperature-dependent Raman measurement. J.L., H.K., J.Y., H.M.O., and K.L. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Kim, H., Yoo, J. et al. Identification of phonon vibrational modes for the layered Ta2Se metal-rich chalcogenide. npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 117 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00632-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00632-7