Abstract

Realizing the potential for 2D SnSe optoelectronics requires understanding the thickness dependence of structure, defects, and optical properties. We investigate the thickness-dependent crystal structure, band gap, and carrier lifetime of SnSe films deposited by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) on (100) MgO. MBE enables stoichiometric (2h00)-oriented SnSe films with tunable thicknesses from 80 nm down to 4 nm. As thickness decreases, out-of-plane covalent bonds contract, while in-plane bonding and the van der Waals gap expand with a concurrent increase in stacking fault density, consistent with theoretical predictions of reduced stacking fault energies. Below 8 nm, the band gap transitions from indirect to direct, increasing from 1.4 eV to 1.8 eV, primarily driven by a combination of structural changes and confinement effects. Our results demonstrate how the thickness and structural distortion of 2D materials can be used to modulate the optical properties relevant to optoelectronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Downscaling 2D materials offers more than just a route to thinner devices; it also provides a knob for tuning performance and enabling new functionalities through confinement, changes in local bonding environments, and symmetry breaking—giving distinctive electrical, optical, and mechanical characteristics compared to bulk1,2. Understanding how to modify the thickness of 2D materials to target a specific response is critical for the development of 2D devices. For example, 2D group IV monochalcogenides in the Pnma phase have the potential to develop ferroelectricity3, photostriction4, and piezoelectricity5 as they approach the monolayer limit. Additionally, these materials are emerging as 2D photodetector-6, thermoelectric-7, and transistor materials6, where tailoring the electrical and optoelectronic response is needed to improve efficiency. Therefore, there is an urgent need to elucidate how the crystal structure and optical properties of this class of materials evolve with thickness6,7.

SnSe is of particular interest within the group IV monochalcogenides due to its large predicted d11 piezoelectric coefficient (250.58 pm/V)5, tunable band gap8, and thermoelectric performance (ZT = 2.6)9. While both the crystal structure and optical properties are predicted to be dependent on the number of SnSe layers, experimental results remain limited10,11. An increased band gap has been observed in SnSe nanosheets and in SnSe films thicker than 50 nm, indicating that material properties evolve with thickness8,12. However, the thickness-dependent relationship between crystal structure and band gap has not been measured in deposited films thinner than 50 nm, despite the predictions that these changes become particularly pronounced at thicknesses below 10 nm8,13.

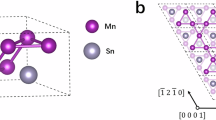

The strong interlayer binding energy (32 meV/Å2) relative to other 2D materials makes SnSe likely to exhibit such distinctive layer-dependent properties14, but also makes controlled exfoliation difficult. While exfoliation can realize SnSe films thicker than 10 nm, continuous lateral coverage of thinner layers requires direct synthesis from a high-purity source material15,16. Beyond thickness control, direct deposition also has additional advantages of controlled orientation, lower defect density, and scalability compared to exfoliation17. Molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), for example, has been used to deposit 2D (2h00) oriented SnSe films on (100) MgO substrates with minimal defects (e.g., SnSe2 inclusions, misoriented grains) due to its precise control over the chemistry during deposition17,18. Therefore, SnSe films deposited by MBE provide a platform to study the thickness-dependent structure and optical properties in monochalcogenides with controlled layering.

In this work, SnSe films with thickness ranging from 80 nm down to 4 nm were deposited on (100) MgO substrates via MBE to determine the thickness-dependent changes in structure and optical properties relevant to optoelectronics, particularly as thickness is reduced below 10 nm. As thickness decreases, the in-plane bond length and van der Waals separation are both observed to increase with a concurrent decrease in the out-of-plane covalent bond length. This, in turn, reduces the interaction between layers of SnSe, increasing the propensity for stacking faults as thickness is reduced. Due to these thickness-dependent structural changes and quantum confinement, the direct band gap increases from 1.3 eV for a bulk single crystal up to 1.8 eV for a 4 nm thick film, along with an increase in carrier lifetime. This work not only provides essential information on how scaling impacts key parameters in SnSe, but also the mechanisms of change, which can be applied to the deposition and device design for a wide range of 2D chalcogenides.

Results and discussion

Film deposition, composition and crystal structure

The first step towards understanding the impact of thickness on the crystal structure and optical response of SnSe is to deposit films spanning a range of thicknesses. By varying the deposition time, SnSe films targeting thicknesses of 4 nm, 8 nm, and 80 nm were prepared. X-ray reflectivity (XRR) corroborates the thickness estimated from the deposition time and provides information on the surface roughness and density19. Representative XRR data for each thickness are shown in Fig. S1, and the associated fitting parameters are given in Table S1. The measured film thicknesses are within 5% of the expected thicknesses based on the deposition time. Thus, each film set is hereafter referred to by the target thickness (80 nm, 8 nm, or 4 nm). Across all deposition conditions, the density for the films is consistent with the theoretical density of 6.1 g/cm3 for SnSe20. Accurately fitting the 8 nm and 80 nm films requires an additional SnO2 layer that is approximately 1.4 nm and 3.9 nm, respectively. However, an SnO2 layer is not necessary to accurately fit the XRR data of the 4 nm film. We have previously shown a self-limiting surface SnO2 layer on SnSe when exposed to air, which does not affect the long-term material stability21. Since the band gap of SnO2 is ~3.6 eV at room temperature, presence of a SnO2 layer is not anticipated to impact the absorptive features of SnSe22, which has a smaller band gap.

In addition to thickness measurements, XRR also provides a metric of surface roughness. The 4 nm films exhibit a predominantly flat morphology, indicated by the low average roughness (Ra) of 1.5 nm. The surface roughness measurements are further corroborated by atomic force microscopy (AFM) images, shown for each film type in Fig. S2. The morphology of the film deposited by MBE shows mixed island and layer growth. The relatively low surface roughness and limited out-of-plane grain growth seen in the thinner films are desirable for electrical and optoelectronic applications that require continuous surface coverage and crystallographic alignment. As the thickness increases up to 80 nm, the surface roughness increases to 2.8 nm as the growth mode transitions towards islanded growth. The measured step height of the layers of the 4 nm and 8 nm films range from 0.6 to 0.7 nm, which closely matches a monolayer (half unit cell) of SnSe. The islands observed in the 80 nm films are relatively flat (Ra = 1.63 nm), with a height of 12–17 nm between the peak of the grain and the bottom of the grain boundary. The XRR and AFM corroborate the low surface roughness of the thinner (<10 nm) films deposited by MBE.

Given the volatility of selenium and the multiple oxidation states that tin can adopt, it is vital to verify the stoichiometry of the MBE-deposited SnSe films. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provides information on film composition as well as insight into the bonding configuration. Figure S3a and S3b show the Se 2 d and Sn 2 d binding energies for an 8 nm thick film. At the film surface, a significant portion of tin is bonded to oxygen23, corroborating the XRR results that pointed to the presence of a surface SnO2 layer. Additional selenium peaks are also measured at the surface, which have previously been attributed to either segregated selenium or SeOH24,25. Next, argon ion etching is used to remove the surface contaminants to determine the bulk film composition. After etching, the Sn-O and excess Se peaks were no longer observed (Fig. S3c and S3d), confirming that the oxidation was limited to the surface, as has previously been reported21. The relative elemental percentages of tin and selenium in the bulk were 51.3% Se and 48.7% Sn, which is within the measurement error of the system for the expected 1:1 Sn:Se ratio. The compositions determined from XPS before and after etching are given in Table S2. Due to the limited measurement depth of XPS, electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) was used to corroborate the composition of SnSe films deposited by MBE, shown in Fig. S4a–c. The composition of a 16 nm thick SnSe film deposited under the same conditions was found to be 54.7% Se and 45.3% Sn through the thickness of the film. The top SnO2 layer was not included in the quantification. The composition is consistent through the thickness of the film, although there are some deviations because of the atomic resolution of the measurement. Overall, the XRR, AFM, XPS, and EELS show that MBE enables the deposition of SnSe with precise layer control down to 4 nm.

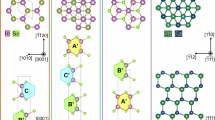

XRD affords insight into the crystal phases, crystallographic orientation, lattice parameters, strain, and defects in the samples. The thickness-dependent XRD results, shown in Fig. 1a, are consistent with the Pnma phase of SnSe (PDF card #00-048-1224)20 with an out-of-plane (2h00) orientation. The single crystal standard is also included as a point of comparison for the bulk lattice parameters. The out-of-plane (2h00) orientation indicates that the van der Waals bonds are perpendicular to the substrate, meaning that the basal plane is oriented parallel to the substrate, as is expected for a 2D material. No other phases or crystallographic orientations are observed by XRD. As the SnSe film thickness decreases, the peak width broadens as the thickness limits the crystallite size, inducing Scherrer broadening. Stacking faults between 2D layers, which have a propensity to form in SnSe films26, can also contribute to the peak broadening. In addition to the peak broadening, there is an increase in the out-of-plane lattice spacing of the SnSe layers with decreasing thickness, as evidenced by the shift to lower 2θ values. Using the 2θ position of the (400) peak to calculate the percent increase in out-of-plane lattice parameter, this translates to a 0.25% and a 1.5% expansion, respectively, in the 8 nm and 4 nm films, when compared to the 80 nm thick film. The expansion could stem from an increased impact of the epitaxial strain imparted from the substrate or an intrinsic change in crystal structure with decreasing thickness10,11.

a Thickness-dependent XRD 2θ scan of SnSe thin films. Peaks denoted by * are from the MgO substrate. Peaks denoted by X are from Cu kβ and W Lα X-rays. All other peaks originate from the SnSe. b Thickness-dependent Raman spectra of SnSe films measured with a 532 nm laser. Dashed vertical lines in a, b indicate the peak positions of the single crystal. All peaks are attributed to SnSe. c Exaggerated schematic of the change in crystal structure with reducing thickness. d The calculated change in the van der Waals (dvdW), covalent out-of-plane (d1), and covalent in-plane (d2) bond lengths as a function of the number of layers.

In addition to the change in out-of-plane spacing, there is anisotropic peak broadening and shifting between the (2h00) order of peaks. Table S3 gives the a-lattice parameters and full width-half maximum (FWHM) values calculated from the (2h00) peak for each film thickness. For the 80 nm films, all peaks produce an out-of-plane lattice parameter \((\left|\bar{a}\right|)\) of 11.515 ± 0.001 Å, consistent with prior report of 11.50 Å. When the film thickness is reduced to 4 nm, there is a larger disparity in the a-lattice parameter calculated from each peak (\(\left|\bar{a}\right|\) = 12.282 Å when using the (200) peak, \(\left|\bar{a}\right|\) = 11.732 Å when using the (400) peak). Ideally, the lattice parameter should be consistent regardless of the exact peak in a given family of equivalent planes. Disparities like those observed here indicate likely structural variations through the thickness of the films that become more pronounced as the film thickness decreases. In other 2D materials, diffraction anisotropy has been attributed to either stacking faults, dislocations, or disorder26,27,28,29,30,31, but anisotropic diffraction has not previously been reported in SnSe films. Overall, the XRD results show that the magnitude of the out-of-plane lattice parameter \((\left|\bar{a}\right|)\) and the degree of disorder increase with reduced film thickness.

Raman spectroscopy corroborates the phase assignment and thickness-dependent bond lengths observed by XRD. As shown in Fig. 1b, mode energies and intensity ratios of the Raman spectra confirmed the presence of the Pnma phase of SnSe with no other phases detected in the thin films, even as a secondary SnSe2 phase is apparent at some locations on the single crystal17. Although an SnO2 layer was observed for the thicker films by XRR and XPS, it is below the detection limit for both XRD and Raman spectroscopy.

Peak shifts in the Raman spectra provide insight into changes in bond length, with peaks shifting to higher wavenumbers indicating shorter bond lengths32. Monitoring the positions of the Raman modes provides an assessment for how the bonding changes with thickness11. A schematic showing the vibrations associated with each Raman mode of Pnma SnSe is shown in Fig. S5. The \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{2}\) and \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{4}\) peaks correspond to predominantly out-of-plane atomic motion vibrational modes, while the \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{1}{,{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{3}\), and \({{\rm{B}}}_{3g}^{1}\) modes correspond to in-plane motion33. As the films become thinner, the \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{1}\), \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{2}\), \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{3}\), and \({{\rm{B}}}_{3g}^{1}\) modes shift to lower wavenumbers, while the \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{4}\) mode shifts to higher wavenumbers. The red shift of the in-plane modes (\({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{1},{{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{3}\), and \({{\rm{B}}}_{3g}^{1}\)) indicates that the in-plane bonds expand as the thickness decreases. The red shift of the \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{2}\) mode indicates that the van der Waals separation also expands with decreasing thickness. In contrast, the blueshift of the \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{4}\) mode suggests that the length of the out-of-plane covalent bonds becomes shorter with reduced thickness. Similar peak shifts were observed using both 532 nm and 785 nm excitation wavelengths (Fig. S6a), verifying that the shift is not caused by resonant Raman effects and can be unequivocally assigned to changes in bond length.

Figure 1c shows a schematic of the collective change in bond length and layer spacing determined from the Raman spectroscopy and XRD (structure exaggerated for clarity). Taken together, the Raman and XRD results support the deduction of a decrease in the out-of-plane covalent bond lengths (d1) and an increase in the van der Waals spacing and in-plane bond length (d2) with decreasing film thickness. If the change in in-plane bonding was due to epitaxial strain imparted from MgO, a blueshift of the \({{\rm{A}}}_{g}^{1}\) and \({{\rm{B}}}_{3g}^{1}\) would be expected because the lattice mismatch between SnSe and MgO is tensile (1.42%) along the b axis, while the lattice mismatch along the c axis is compressive (−5.51%). To provide further evidence that the change in structure is not caused by the substrate and to compare Raman shifts, an 8 nm film was deposited on muscovite mica: a 2D substrate with high lattice mismatch (>14%) and low propensity for epitaxy. The films deposited on muscovite mica and MgO show similar shifts in Raman modes with decreasing thickness (Fig. S6b), indicating that the structural changes are indeed not due to epitaxy from the substrate. Thus, it is evident that the structural changes are intrinsic to the material and not imparted by external factors. This characteristic will enable identification of SnSe film thickness using Raman shifts for SnSe films, similar to approaches used for graphene and MoS210,34. In addition to the Raman shift, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the Raman peaks also increases with decreasing thickness, indicating that disorder increases with decreasing thickness, which corroborates the finding of increasing stacking faults and dislocations by XRD.

To better understand how the bonding changes with thickness, the crystal structure and bond length of SnSe are calculated using density functional theory (DFT) with varying layer thicknesses. No substrate-film interactions are included in the calculations; therefore, any change in structure with decreasing thickness must be intrinsic and not due to strain imparted from the substrate. The trends from the DFT calculations corroborate the changes in bonding observed by Raman and XRD. The out-of-plane van der Waals bond length (labeled here with dvdW) and in-plane bond lengths (d2) increase, while the out-of-plane covalent bond length (d1) decreases with decreasing film thickness, presented in Fig. 1d. While the out-of-plane bonds (both van der Waals and covalent bonds) are predicted to shift in opposite directions, an overall increase in the \(\left|\bar{a}\right|\) lattice parameter is predicted (Figure S7), in agreement with the shift observed in XRD. However, the calculated change in lattice parameter is less than that observed by XRD. The discrepancy between theory and experiment can be attributed to the presence of stacking faults and dislocations, which produce peak shifts in bulk measurements such as XRD, but are not captured in DFT-calculated lattice parameters.

To assess the likelihood for increased stacking faults in thinner layers, we calculate the relative energy of stacking faults as a function of film thickness to compare the relative stability of different 2D stacking configurations. Figure 2a gives the relative energies for various stacking faults shifted along the [001] or [010] directions or both, as illustrated in Fig. S8a and S8b. As film thickness decreases, the relative energy of different stacking faults (e.g., AC, AA) compared to the AB ground state becomes progressively smaller. The lowest energy stacking fault is the AC polar configuration, which lies above the AB stacking energy by 37 meV per layer in the bulk and by only 15 meV per layer in a bilayer. The decrease in relative stacking fault energy with reducing thickness is understandable, given the increased van der Waals bond length, which points to decreased interactions between layers. The calculated decrease in stacking fault energy agrees with the increased anisotropy in XRD (2h00) peaks as the film thickness is reduced. The higher propensity for stacking faults with reduced film thickness has been proposed to cause a net polarization in SnSe films deposited by chemical vapor deposition due to symmetry breaking26. The net polarization induced by stacking faults in SnSe enables novel functionalities such as ferroelectric and nonlinear optical applications26. Stacking faults have also been predicted to lead to a direct band gap in SnSe. Thus, understanding the propensity for stacking faults with thickness is critical for optoelectronic applications35.

a. Relative energy of different stacking faults in SnSe compared to the expected AB antipolar stacking. Dashed lines indicate the bulk values in SnSe. Representative STEM images of a 4 nm (b) and 16 nm (c) thick SnSe film on MgO substrate. The image of the 4 nm film shows a basal dislocation (marked by “T”), a stacking fault (plane indicated by line labeled “SF”), and small grains with orthogonal orientations (zone axis markers). By contrast, the 16 nm thick film contains large regions free of these types of defects.

To directly visualize how the film structure varies with thickness, high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) was performed on 4 nm and 16 nm thick SnSe samples. To enable a direct comparison between experiment and theory, a 16 nm SnSe film was deposited, corresponding to the maximum number of layers considered in our calculations and representing the thickness regime where stacking fault density and bond lengths approach bulk-like values. Representative images of the 4 nm and 16 nm samples are presented in Fig. 2b, c, respectively. The 16 nm films have a defect-free SnSe structure maintained throughout the full thickness, extending laterally over more than 50 nm. Owing to the cubic symmetry of the MgO substrate, grains oriented along both the [010] and [001] zone axes are present across the entire sample (not shown here). This is expected due to the symmetry of the underlying substrate (4-fold) compared to the symmetry of the film (2-fold) about the out-of-plane axes. The 4 nm film exhibits a more disordered crystal structure, with small grains and numerous defects, including stacking faults, basal dislocations (extra ½ plane of a complete 2D material unit cell), and orthorhombic orientation changes throughout its thickness. Additional representative images showing the increased propensity for stacking faults and disorder in the thinner films are shown in Fig. S9. The longer deposition time for the thicker films likely provides additional annealing to promote the equilibrium layering structure in the thicker films. Further in-situ analysis is needed to assess how the film structure changes with time. The results from the STEM are consistent with the reduced barrier for stacking faults predicted in Fig. 2a. Furthermore, these defects in the 4 nm film contribute to the variations in the XRD peak positions and the increased FWHM of the XRD and Raman peaks as a function of thickness seen in Fig. 1a, b.

Quantitative image analysis is performed on areas without observed defects in both 4 nm and 16 nm films to understand the intrinsic structural changes as a function of film thickness. Details of the image processing and analysis are listed in the methods section. Figures 3a, b show representative measurements of atomic column positions in both films, with the atom positions overlayed on the micrograph. The measured Sn positions were used to quantify the distributions of four structural parameters: the \(\left|\bar{a}\right|\) (out-of-plane) and \(\left|\bar{c}\right|\) (in-plane) lattice parameters, 2D layer thickness (Sn-Sn distance), and van der Waals gap width. For each parameter, Sn-Sn distances were calculated for all measured atomic columns and projected along the appropriate in- or out-of-plane lattice vector. The first SnSe layer in each sample was excluded from the analysis, as it is distorted relative to the bulk structure, and in the case of a 4 nm film, is oriented orthogonally to the overlying layers. Figure 3c–f summarize the structural analysis. In agreement with the bulk measurements and theory results, the average spacing of the van der Waals gap increases with decreasing thickness (Fig. 3c) while the average layer thickness decreases slightly (Fig. 3d). The average \(\left|\bar{a}\right|\) increases approximately 2 pm in the 4 nm film compared to the 16 nm film. The \(\left|\bar{c}\right|\) increases only slightly, below the resolution limit of STEM. Furthermore, the broader distribution in the layer thickness and van der Waals gap as thickness is reduced matches the increased FWHM of the peaks in XRD in Fig. 1a. The trends observed in the change in atomic spacing match the XRD, Raman, and DFT results. Collectively, the HAADF STEM, XRD, Raman, and DFT point to thickness-dependent bonding and crystal structure variations of SnSe, which, as we will demonstrate in the next section, is critical for understanding optical properties of SnSe.

a HAADF-STEM image analysis showing the measured Sn and Se atomic column positions of the 4 nm and b 16 nm films. The density distribution of c the van der Waals gap width, d 2D covalent bonded layer thickness, and the e \(\left|\bar{a}\right|\) and f \(\left|\bar{c}\right|\) lattice parameters. The histograms use 1 pm bins, and the lines show the kernel density estimate of the measurements.

Thickness dependent optical properties

Decreasing the layer thickness in other 2D materials has been shown to induce changes in the optical properties due to both quantum confinement and changes in bonding14,35. However, for SnSe, the impact of the structural changes on its optical response remains unclear. To address this knowledge gap, UV-Vis spectroscopy was used to track the evolution of SnSe band gap with decreasing thickness, as shown in Fig. 4a. Measurements of SnSe single crystals are also included to provide a point of reference for the thin films. The Tauc plot for the SnSe thin films fit to a power coefficient of ½, indicating that these samples exhibit a direct band gap. The direct band gap of the SnSe single crystal is 1.29 eV, which matches the predicted bulk direct band gap of SnSe (1.3 eV)36. The direct band gap of SnSe films increases with decreasing thickness, from 1.4 eV at 80 nm, to 1.5 eV in the 8 nm films, and finally to 1.8 eV in the 4 nm samples. In addition to the observed direct band gap, the 80 nm films also have an indirect transition at 1.3 eV, highlighted in the Tauc plot in Fig. S10. While indirect transitions were not observed by UV-Vis for the thinner films, the increase in defects could mask a lower-energy indirect transition. In other 2D monochalcogenides and dichalcogenides, such as MoS2 and GaSe, a thickness dependence on the nature (direct, indirect) of the band gap has been attributed to quantum confinement37,38,39,40. The direct band gap observed in the thinner SnSe films increases the thickness-normalized light absorption compared to an indirect band gap, which is critical in 2D optoelectronics due to the reduced amount of material to absorb light. The tunable band gap of the SnSe films, spanning from the near-infrared to visible range, is beneficial for photodetectors and photovoltaics, where the wavelength of light absorption is critical to device performance. The Urbach tail—the region of sub-band gap absorption—increases with decreasing thickness consistent with the increase in structural disorder observed by XRD, Raman, and STEM data.

a Tauc plot from UV-Vis spectra of a SnSe single crystal and 80 nm, 8 nm, and 4 nm thick SnSe films on MgO. Measured data and fits are offset along the y-axis for clarity. b A comparison of the measured and calculated direct band gaps from this study. Trendlines of calculated results are calculated with a 1/d relationship. c Time-resolved photoluminescence spectra of the SnSe films on MgO.

DFT calculations of the direct electronic band gap in Fig. 4b qualitatively support the increasing trend in band gap with decreasing SnSe thickness observed experimentally. We note that despite the scissor shift correction applied, our DFT results still underestimate the band gap for <10 nm thicknesses but correctly predict the band gap of the thicker film limit. We find that the calculated indirect band gap also increases with decreasing thickness (see Fig. S11), with the indirect transition predicted to be a lower energy transition for all thicknesses. The increased defect concentration observed in the thinner samples could increase the sub-band gap absorption and mask lower energy indirect band gaps in the thinner films. Prior theoretical work on SnSe shows that stacking faults can drive an indirect-to-direct band gap transition and increase the band gap energy due to a shift in the conduction-band minimum caused by the change in interlayer interactions with different stacking configurations35. Stacking faults were not included in the DFT-calculated band gaps, which could cause the discrepancy between calculated and measured band gaps. The increased propensity for stacking faults and dislocations reduces the likelihood of phonon-mediated electronic transitions (i.e., indirect band gaps) due to phonon-stacking fault and phonon-dislocation interactions, making the direct transition more pronounced even if the indirect transition is lower in energy41,42. Therefore, the increased stacking fault density contributes to the increase in band gap and indirect-to-direct transition as the thickness is reduced from 80 nm to 8 nm—which is corroborated by the XRD, STEM, and computational results that show an increase in stacking faults at lower thicknesses.

Arguably, both quantum confinement and the thickness-dependent crystal structure could contribute to the observed and calculated band gap increase with decreasing thickness14,35. To investigate the origin for the discrepancy between theory and experiment, we performed two additional sets of calculations: (1) the band gap of SnSe films was calculated constraining the in-plane lattice parameters, van der Waals layer spacing, and atomic positions to those of the bulk (see blue curve in Fig. 4b); (2) in-plane lattice constants of the film were fixed to the bulk values, while atomic position and van der Waals distances were allowed to relax (black curve in Fig. 4b). In both cases, across all thicknesses we observe that the band gap at fixed in-plane lattice constants is rigidly shifted upward by about 0.1–0.15 eV compared to the case when both lattice constants and atomic positions are allowed to relax. These results point to the band gap increase at low thicknesses originating from primarily from the stacking faults or a confinement effect rather than the change in bond lengths, as has been previously reported for MoS243.

The band gap of the samples deposited both in this study and in previous reports is compared in Table 1. The band gaps of the SnSe films deposited by MBE in this work fall within the range of SnSe produced by other thin film methods. The 1.3 eV indirect band gap measured for the 80 nm films matches the expected indirect transition for SnSe, while the direct band gap measured for thinner films is similar to what has been observed for other thin films, shown in Table 1. The likelihood of forming stacking faults strongly depend on the deposition or growth method used, which, as discussed earlier, can affect both the energy and nature (indirect, direct, etc.) of the optical band gap of SnSe35. For example, in liquid phase exfoliation (LPE), stacking faults are less likely to form because samples are synthesized from bulk SnSe, which has a higher activation energy for stacking faults (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, LPE is typically performed at room temperature, whereas the higher deposition temperatures in MBE would make it easier to overcome the smaller barrier to stacking fault formation in thin films. Therefore, the direct band gaps measured in the directly deposited films are likely a function of stacking faults. An indirect band gap of single crystal SnSe has previously been reported at 0.91 eV8. However, this feature could not be assessed because it lies below the detection limit of the spectrophotometer used (Jasco V-630 spectrometer, energy limit of 1.13 eV)8.

Due to quantum confinement, as well as the changes in band gap and crystal structure, the carrier lifetime in SnSe likely changes with thickness44. Understanding how the carrier lifetime changes with thickness is critical to understand the device applications for 2D SnSe. For this reason, the thickness-dependent carrier lifetime of SnSe was probed via time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL), shown in Fig. 4c (the corresponding TRPL fittings are shown in Fig. S12). The carrier lifetimes decrease as thickness is increased, from 1.4 ns for the 4 nm film, to 0.34 ns for the 8 nm film, and to 0.29 ns for the 80 nm film45. The increase in carrier lifetime observed with decreasing thickness will facilitate charge extraction in an optoelectronic device. A similar change in carrier lifetime with decreasing thickness was observed in thin films of the isostructural compound SnS, attributed to changes in the energy level alignment due to quantum confinement44. The increased defect density with reduced thickness could also lead to trap states, which have been shown to increase carrier lifetime46. Therefore, confinement and defect traps are anticipated as the cause of the thickness-tunable carrier lifetime in SnSe, especially considering the increased level of disorder within the thinner layers as evidenced by the broadening of the Raman and XRD spectra.

In summary, we find that both the crystal structure and the band gap are dependent on the layer thickness in SnSe. (2h00) oriented SnSe films with controllable thickness and no detected secondary orientations or phases were deposited by MBE. Structural changes occur with decreasing thickness, where covalently bonded layers of SnSe are compressed out-of-plane, and the van der Waals bonds and in-plane bonds are stretched. Furthermore, XRD, DFT, and STEM results show that there is an increased propensity for stacking faults as thickness is reduced, which enables a direct band gap in films below 10 nm. Between the 80 nm and 8 nm films, the direct band gap remains fairly consistent, but as the film thickness is reduced to 4 nm, we observe a 0.4 eV increase in the direct band gap of SnSe (1.8 eV). The carrier lifetime of the films also increases with decreasing thickness, indicating that there is quantum confinement in thinner films. In addition to confinement, thickness-dependent changes in bonding contribute to the observed band gap evolution. Our ab-initio calculations support these interpretations and further show that the optical properties of ultra-thin (<20 layers) SnSe are driven primarily by quantum confinement effects rather than mechanical strain. The insights into the thickness-dependent properties of SnSe will enable development of SnSe optoelectronic and ferroelectric devices and pave the way for future research into similar 2D materials.

Methods

Thin film synthesis

SnSe thin films were deposited by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE, DCA Instruments, model R450) on (100) MgO substrates (MTI Corp.). MgO was selected as the substrate as it has been shown to promote the (2h00)-orientation of the Pnma phase SnSe17. Additionally, the wide band gap (Eg > 5 eV) of MgO ensures that the optical response can be differentiated from SnSe47. The background pressure was held below 2.5 × 10−9 Torr with no background selenium pressure. Prior to deposition, the MgO substrates were cleaved and subsequently annealed in vacuum at 900 °C for 10 min to remove surface contamination. Then, the substrates were cooled to the deposition temperature of 290 ± 5−°C and held there for 10 min before initiating the deposition. The cooling rate after deposition is approximately 10 °C/min and was held consistent between samples. The Sn:Se flux ratio was controlled through two independent Sn and Se effusion cells set to a ratio of 1:1.39 ± 0.3, as calibrated by a quartz crystal microbalance. A 1:1.4 flux ratio is used in this study (compared to higher flux ratios that have been used in previous work17) because it was found to improve crystallinity and morphology in SnSe films thinner than 10 nm.” The deposition rate was maintained between 0.08–0.16 Å s−1. The deposition timing was adjusted to target films with thicknesses of 80 nm (83 min), 16 nm (30 min), 8 nm (30 min), and 4 nm (7 min). 8 nm thick SnSe samples were also deposited on uncleaved muscovite mica substrates (MTI Corp.) under the same conditions to provide a reference material on a layered substrate. SnSe single crystals (2d Semiconductors) were used as a standard for comparison.

Compositional and structural characterization

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were taken with a Thermo K-Alpha X-ray photoelectron spectrometer with a monochromatic aluminum source (1.486 keV) and 180° double-focusing hemispherical analyzer. An electron flood gun was used to reduce charging effects. Any residual charging was corrected by shifting the adventitious C 1 s peak to 284.8 eV, as described in ref. 48. The crystal structure of the SnSe thin films was characterized by X-ray diffraction using a Rigaku Smartlab XE diffractometer equipped with a copper Kα1 source, an incident Ge (220) two-bounce monochromator, and a high-resolution θ–θ closed‑loop goniometer. 2θ scans were measured from 10 to 50° with a 0.02° step at a scan rate of 4°/min. The 2θ positions for all scans were corrected using the MgO (200) peak at 2θ = 42.90° to account for any angular offset (PDF card #01-071-1176)49. The 2θ measurement of the single crystal was performed with a Rigaku Miniflex with a copper Kα source from 10 to 50° with a step of 0.04° and a scan rate of 10°/min. Film thicknesses were determined by X-ray reflectivity (XRR), also using the Rigaku Smartlab XE, performed with a 1°/min scan rate and a 0.02° step size. The XRR data were fit with the SmartLab Studio software (Rigaku). R-factor values for the goodness of fit were below 2% for all samples. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images were collected with a Bruker Icon AFM using Scanasyst Air tips (Si tip on nitride lever, k = 0.4 N/m, tip radius = 2 nm) using the quantitative nanomechanical mapping measurement mode. The images were collected with 512 samples/line and a scan rate of <0.6 Hz.

SnSe film cross sections were prepared by the focused ion beam (FIB) liftout method using a ThermoFisher Helios dual-beam FIB with Ga source. All lamellae were cut on the MgO [100] zone axis and thinned by the ion beam down to a final voltage of 2 kV to minimize amorphous damage and Ga implantation. To minimize atmosphere exposure and degradation of the FIB samples after liftout, all samples were stored in an Ar-filled glove box and sealed in Ar-filled bags for transportation to the microscope. Thickness of crystalline TEM samples can be estimated by analyzing the intensity variations in the position averaged convergent beam electron diffraction (PACBED)50. The FIB lamella we presented in this study is estimated by position averaged convergent beam electron diffraction to be, at most, 20–30 nm thick in the analyzed regions.

Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) imaging was done using a Thermo-Fisher Titan STEM at 300 kV with a convergence angle of 30 mrad and a beam current of approximately 50 pA. Images were acquired with dwell times of 3 or 5 µs per pixel, and STEM pixel sizes of 9.0 or 12.9 pm for the 16 nm and 4 nm film samples, respectively. For quantitative structural analysis, HAADF STEM image pairs were acquired at orthogonal scan directions. The images were drift corrected using a non-linear drift correction code51. Instrumental scan distortion was also measured and corrected with a custom script using images from the cubic MgO substrate. Atomic scale structural measurements of the films were performed on the fully corrected images using the Python package SingleOrigin52. This software isolates intensity peaks in the image using the watershed algorithm. Isolated peaks are matched to a projected reference lattice generated from an appropriate crystallographic information file to ensure all atom columns are found, and spurious peaks are ignored. 2D Gaussians are then fit to each atomic column peak to measure the positions. For closely-spaced atom columns, groups of close columns are automatically grouped together and simultaneously fit with multiple 2D gaussians (one per atom column in the group) to account for overlapping intensity. In the current data, this meant that Sn-Se dumbbells in the [010] zone axis of SnSe were paired together, and the pair fit with two Gaussians. Pixel sizes were calibrated on images of [110] zone axis silicon using 5.43102 as the lattice parameter53. The accuracy of the atom position and distance measurements is assessed from the MgO substrate. The 2D pair correlation function of the measured atom positions in an image of the MgO substrate was calculated, showing peaks with standard deviations (σ) between 4.9 and 5.8 pm at correlation lengths of up to 1 nm (approximately the longest distances measured from the SnSe films). Thus, the distance measurement error is conservatively estimated as ±5.8 pm, and the fitting error for individual atom columns is inferred to be σ = 4.1 pm (sub-pixel precision). Using this measurement variance, the range of estimated standard errors on the mean for the SnSe distance measurements in Fig. 3 is: ±0.28 to 0.45 pm for the 4 nm film and ±0.10 to 0.14 pm for the 16 nm film. These ranges reflect the different number of measurements made for each distance parameter and sample based on the number of available atom columns in the images. We note that the standard error in all cases is well under 1 pm.

Electron energy loss spectrum images were acquired on the same instrument using a Gatan GIF Tridiem spectrometer equipped with a K2 Summit direct electron detector. The data was collected at 300 kV beam energy, a convergence angle of 21.4 mrad, EELS collection angle of 42.4 mrad, pixel size of 0.5 A, and dwell time 2.5 ms. The detector was operated in electron counting mode to reduce noise in the data. To quantify the elemental composition, Sn-M and Se-L edge models were calculated using the eXSpy python module (with the DFT-calculated general oscillator strengths)54. Power law background and model fitting to the experimental spectra were performed using a custom script.

Optical characterization

The UV-Vis spectra were collected with a Jasco V-630 spectrometer from 1100 nm to 280 nm at a speed of 500 nm/min. A blank MgO substrate was used as a reference for background subtraction. The band gap was estimated from the linear extrapolation to the energy axis in the Tauc plot. Tauc’s method was used to analyze the band gap and to determine if the band gap is direct or indirect. The absorption coefficient (α) is calculated from:

where t is film thickness, and T is the transmittance55. The relationship between the absorption coefficient and electron energy was then determined by Tauc’s relationship, shown below:

where B is an energy dependent constant, Eph is the photon energy (hν), Eg is the band gap, and n is the power factor55. The power factor is 1/2 for an allowed direct transition and 2 for an allowed indirect transition. A linear fit is applied to the data in the Tauc plot over a minimum range of 0.5 eV, ensuring that the coefficient of determination (R2) is greater than 0.99. The band gap was then extracted from the x-intercept of the line-of-fit.

Raman spectroscopy was used for further confirmation of the crystal structure and to assess any changes in vibrational modes associated with variations in bonding that occur as the thickness is reduced. Raman spectra were collected with two different energy lasers, in two distinct systems, to confirm peak shifts. The Raman spectra were collected in air utilizing a Witec Alpha300R confocal microscope with 0.25 mW focused to a diffraction limited spot size of ~600 nm with a wavelength of 532 nm (2.33 eV). Collected light was dispersed off a 1800 lines/mm grating within a 600 mm Czerny-Turner style spectrometer, resulting in a spectral resolution of <0.5 cm−1. Accompanying time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) was collected with the same instrument that was utilized for the 532 nm Raman spectroscopy measurements. For TRPL a 405 nm (3.06 eV) laser having a nominal pulse width of 50–100 ps was used for excitation, with the resulting luminescence monitored with an avalanche photodiode photon counter to determine the dependence of carrier lifetime on thickness. Lifetime, τ, was extracted by fitting an exponential decay function to the collected photoluminescence intensity profile via:

where I is the intensity of photons counted, \({I}_{o}\) is the baseline count, A is the amplitude of the peak, and \({t}_{0}\) is the time of initial excitation. The Raman spectra were further corroborated by taking measurements at a wavelength of 785 nm (1.58 eV) with an Invia Qontor Renishaw Raman with a 2400 lines/mm grating and a resolution <0.5 cm−1.

Theory

Density Functional Theory calculations were preformed using the Vienna Ab initio Software Package56,57,58. Various SnSe thicknesses were modeled, ranging from the monolayer limit up to 30 layers (which is equivalent to a film thickness of 17 nm). A vacuum region of 30 Å was used to limit interactions between periodic images. The SCAN exchange-correlation functional59 was selected with the added rvv10 correction60 to model the Van der Waals interactions between layers. The electronic density was converged (with changes in energy smaller than 10-8 eV between self-consistent field iterations), and the in-plane lattice constants and atomic positions were relaxed (with forces smaller than 1 meV/Å, except for 20 and 30 layers, for which forces were converged below 5 meV/Å) using a Brillouin zone sampling of 15 × 15 × 1. The single particle Kohn-Sham eigenvalues and the optical dielectric constants were subsequently computed with the fixed converged electronic density on a denser 24 × 24 × 1 grid in the Brillouin zone. The direct and indirect electronic band gaps were computed using the obtained Kohn-Sham eigenvalues from this latter calculation. Note also that we employed the HSE06 hybrid exchange-correlation functional on the monolayer, bi-layer, and bulk structures relaxed within the SCAN+rvv10 approximation. In all three cases, we found that the electronic band gap increased by about 0.5 eV. Therefore, we present our results with an added scissor shift correction of the band gap of 0.5 eV, which matches closely the experimentally measured band gap for SnSe in the bulk limit. A 500 eV kinetic energy cut-off for the plane wave basis was employed across all calculations.

Data availability

The data that support the plots and findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lin, Y.-C. et al. Recent advances in 2D material theory, synthesis, properties, and applications. ACS Nano 17, 9694–9747 (2023).

Cui, C., Xue, F., Hu, W.-J. & Li, L.-J. Two-dimensional materials with piezoelectric and ferroelectric functionalities. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 18 (2018).

Fei, R., Kang, W. & Yang, L. Ferroelectricity and phase transitions in monolayer group-IV monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 097601 (2016).

Haleoot, R. et al. Photostrictive two-dimensional materials in the monochalcogenide family. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 227401 (2017).

Fei, R., Li, W., Li, J. & Yang, L. Giant piezoelectricity of monolayer group IV monochalcogenides: SnSe, SnS, GeSe, and GeS. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 173104 (2015).

Hu, Z. et al. Recent progress in 2D group IV–IV monochalcogenides: synthesis, properties, and applications. Nanotechnology 30, 252001 (2019).

Qin, B. et al. High thermoelectric efficiency realized in SnSe crystals via structural modulation. Nat. Commun. 14, 1366 (2023).

Huang, Y., Li, L., Lin, Y.-H. & Nan, C.-W. Liquid exfoliation few-layer SnSe nanosheets with tunable band gap. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 17530–17537 (2017).

Zhao, L.-D. et al. Ultralow thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric figure of merit in SnSe crystals. Nature 508, 373–377 (2014).

Li, H. et al. From bulk to monolayer MoS2: evolution of Raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 1385–1390 (2012).

Park, M., Choi, J. S., Yang, L. & Lee, H. Raman spectra shift of few-layer IV-VI 2D materials. Sci. Rep. 9, 19826 (2019).

Inoue, T., Hiramatsu, H., Hosono, H. & Kamiya, T. Heteroepitaxial growth of SnSe films by pulsed laser deposition using Se-rich targets. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 205302 (2015).

Li, Z. et al. Effect of film thickness and evaporation rate on co-evaporated SnSe thin films for photovoltaic applications. RSC Adv. 10, 16749–16755 (2020).

Ronneberger, I., Zanolli, Z., Wuttig, M. & Mazzarello, R. Changes of structure and bonding with thickness in chalcogenide thin films. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001033 (2020).

Zhang, L.-C. et al. Tinselenidene: a two-dimensional auxetic material with ultralow lattice thermal conductivity and ultrahigh hole mobility. Sci. Rep. 6, 19830 (2016).

Hlushchenko, D. et al. Stability of mechanically exfoliated layered monochalcogenides under ambient conditions. Sci. Rep. 13, 19114 (2023).

Chin, J. R. et al. Self-limiting stoichiometry in SnSe thin films. Nanoscale 15, 9973–9984 (2023).

Mortelmans, W. et al. Measuring and then eliminating twin domains in SnSe thin films using fast optical metrology and molecular beam epitaxy. ACS Nano 16, 9472–9478 (2022).

Miller, A. M. et al. Extracting information from X-ray diffraction patterns containing Laue oscillations. Z. Für Naturforschung B 77, 313–322 (2022).

Grier, D. & McCarthy, G. North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota, USA, ICDD Grant-in-Aid 1991. Powder Diffr. File Int. Cent. Diffr. Data (1994).

Chin, J. R. et al. Determining the oxidation stability of SnSe under atmospheric exposure. MRS Commun. https://doi.org/10.1557/s43579-024-00630-8 (2024).

Zhou, W., Liu, Y., Yang, Y. & Wu, P. Band gap engineering of SnO2 by epitaxial strain: experimental and theoretical investigations. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 6448–6453 (2014).

Badrinarayanan, S., Mandale, A. B., Gunjikar, V. G. & Sinha, A. P. B. Mechanism of high-temperature oxidation of tin selenide. J. Mater. Sci. 21, 3333–3338 (1986).

Hellgren, N. et al. Effect of etching on the oxidation of zinc selenide surfaces characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 528, 146604 (2020).

Canava, B., Vigneron, J., Etcheberry, A., Guillemoles, J. F. & Lincot, D. High resolution XPS studies of Se chemistry of a Cu(In, Ga)Se2 surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 202, 8–14 (2002).

Chiu, M.-H. et al. Growth of large-sized 2D ultrathin SnSe crystals with in-plane ferroelectricity. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2201031 (2023).

Sun, F. et al. Effects of biaxial strain and local constant potential on electronic structure of monolayer SnSe. Phys. B Condens. Matter 618, 413177 (2021).

Paterson, M. S. X-ray diffraction by face-centered cubic crystals with deformation faults. J. Appl. Phys. 23, 805–811 (1952).

Warren, B. E. X-ray studies of deformed metals. Prog. Met. Phys. 8, 147–202 (1959).

Ungár, T. Dislocation densities, arrangements and character from X-ray diffraction experiments. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 309–310, 14–22 (2001).

Toyoki, K., Kitaguchi, D., Shiratsuchi, Y. & Nakatani, R. Influence of long- and short-range chemical order on spontaneous magnetization in single-crystalline Fe0.6Al0.4 compound thin films. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 36, 135805 (2023).

Pan, W. et al. Biaxial compressive strain engineering in graphene/boron nitride heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 2, 893 (2012).

Xu, X. et al. In-plane anisotropies of polarized raman response and electrical conductivity in layered tin selenide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 12601–12607 (2017).

Ferrari, A. C. et al. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 187401 (2006).

Yang, J.-H. & Gong, X.-G. Stacking induced indirect-to-direct bandgap transition in layered group-IV monochalcogenides for ideal optoelectronics. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 11858–11867 (2019).

Lefebvre, I., Szymanski, M. A., Olivier-Fourcade, J. & Jumas, J. C. Electronic structure of tin monochalcogenides from SnO to SnTe. Phys. Rev. B 58, 1896–1906 (1998).

Mak, K. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Ben Aziza, Z. Valence band inversion and spin-orbit effects in the electronic structure of monolayer GaSe. Phys. Rev. B 98, 115405 (2018).

Jo, M. et al. Indirect-to-direct bandgap crossover and room-temperature valley polarization of multilayer MoS2 achieved by electrochemical intercalation. Adv. Mater. 36, 2407997 (2024).

Ben Aziza, Z. et al. Tunable quasiparticle band gap in few-layer GaSe/graphene van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 96, 035407 (2017).

Singh, B. K., Menon, V. J. & Sood, K. C. Phonon conductivity of plastically deformed crystals: role of stacking faults and dislocations. Phys. Rev. B 74, 184302 (2006).

Li, J. et al. Stacking fault-induced minimized lattice thermal conductivity in the high-performance gete-based thermoelectric materials upon Bi2 Te3 alloying. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 20064–20072 (2019).

Manzeli, S., Allain, A., Ghadimi, A. & Kis, A. Piezoresistivity and strain-induced band gap tuning in atomically thin MoS2. Nano Lett. 15, 5330–5335 (2015).

Zhang, F. et al. Quantum confinement-induced enhanced nonlinearity and carrier lifetime modulation in two-dimensional tin sulfide. Nanophotonics 9, 1963–1972 (2020).

Péan, E. V., Dimitrov, S., De Castro, C. S. & Davies, M. L. Interpreting time-resolved photoluminescence of perovskite materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 28345–28358 (2020).

Yang, Y. & Lin, Q. Chalcogenide semiconductors: charge carrier dynamics and optoelectronic applications. Chem. Commun. 61, 11732–11745 (2025).

Mangaiyarkkarasi, J., Sasikumar, S., Meenakumari, V. & Revathy, J. S. A multidimensional approach to understanding wide band gap MgO: structural, morphological, optical, and electron density insights. MRS Adv. 9, 870–875 (2024).

Grey, L. H., Nie, H.-Y. & Biesinger, M. C. Defining the nature of adventitious carbon and improving its merit as a charge correction reference for XPS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 653, 159319 (2024).

Sasaki, S., Fujino, K. & Takéuchi, Y. X-ray determination of electron-density distributions in oxides, MgO, MnO, CoO, and NiO, and atomic scattering factors of their constituent atoms. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 55, 43–48 (1979).

LeBeau, J. M., Findlay, S. D., Allen, L. J. & Stemmer, S. Position averaged convergent beam electron diffraction: theory and applications. Ultramicroscopy 110, 118–125 (2010).

Ophus, C., Ciston, J. & Nelson, C. T. Correcting nonlinear drift distortion of scanning probe and scanning transmission electron microscopies from image pairs with orthogonal scan directions. Ultramicroscopy 162, 1–9 (2016).

Funni, S. D. et al. Theory and application of the vector pair correlation function for real-space crystallographic analysis of order/disorder correlations from STEM images. APL Mater 9, 091110 (2021).

Windisch, D. & Becker, P. Silicon lattice parameters as an absolute scale of length for high precision measurements of fundamental constants. Phys. Status Solidi A 118, 379–388 (1990).

Peña, F. de la et al. hyperspy/exspy: v0.3.2. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14957070 (2025).

Amorphous and Liquid Semiconductors https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-8705-7 (Springer, 1974).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. P. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036402 (2015).

Sabatini, R., Gorni, T. & de Gironcoli, S. Nonlocal van der Waals density functional made simple and efficient. Phys. Rev. B 87, 041108 (2013).

Barrios-Salgado, E., Nair, M. T. S. & Nair, P. K. Chemically deposited snse thin films: thermal stability and solar cell application. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 3, Q169 (2014).

Franzman, M. A., Schlenker, C. W., Thompson, M. E. & Brutchey, R. L. Solution-phase synthesis of snse nanocrystals for use in solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4060–4061 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award no. FA9550-24-1-0263. L.M.G. acknowledges the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) Young Investigator Award under Grant No. FA9550-22-1-0237. This work was performed in part at the Georgia Tech Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology (IEN) under the SEED Grant support. The IEN is a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant ECCS-1542174). J.R.C. acknowledges the support of the National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-2039655. The STEM characterization by J.J.C. and S.D.F. was supported by the Department of Energy (DOE) Basic Energy Sciences (BES) DE-SC0023905. The work presented has been facilitated by the Materials Innovation Platform of The Pennsylvania State University, the Two-Dimensional Crystal Consortium (2DCC-MIP), supported by NSF through cooperative agreements no. DMR-1539916 and DMR-2039351. C.P. acknowledges support from the Arkansas High Performance Computing Center, which is funded through multiple National Science Foundation grants and the Arkansas Economic Development Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B.F., L.M.G., and A.M.O. wrote the main manuscript text. M.B.F. prepared the figures and led the analysis and characterization. M.B.F. and A.G. led the characterization, analysis, and discussion of the optical properties, and M.B.F., J.R.C., and J.W. led the deposition of the films used in this study. S.D.F. prepared cross-sectional STEM samples using focused ion beam milling and characterized the atomic structures using STEM under the supervision of J.J.C. W.J.S. measured the Raman spectra and time-resolved photoluminescence under the supervision of T.B. L.M.G. developed the idea and led the study. C.P. performed all computational results in this study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frye, M.B., Chin, J.R., Smith, W.J. et al. Thickness-modulated crystal structure and band gap of 2D SnSe deposited by molecular beam epitaxy. npj 2D Mater Appl 10, 18 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00655-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00655-0