Abstract

Polysomnography, the gold standard diagnostic tool in sleep medicine, is performed in an artificial environment. This might alter sleep and may not accurately reflect typical sleep patterns. While macro-structures are sensitive to environmental effects, micro-structures remain more stable. In this study we applied semi-automated algorithms to capture REM sleep without atonia (RSWA) and sleep spindles, comparing lab and home measurements. We analyzed 107 full-night recordings from 55 subjects: 24 healthy adults, 28 Parkinson’s disease patients (15 RBD), and three with isolated Rem sleep behavior disorder (RBD). Sessions were manually scored. An automatic algorithm for quantifying RSWA was developed and tested against manual scoring. RSWAi showed a 60% correlation between home and lab. RBD detection achieved 83% sensitivity, 79% specificity, and 81% balanced accuracy. The algorithm accurately quantified RSWA, enabling the detection of RBD patients. These findings could facilitate more accessible sleep testing, and provide a possible alternative for screening RBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A Polysomnography (PSG) lab study is the gold standard in sleep medicine for diagnosing sleep-related disorders. PSG captures sleep data such as brain waves using electroencephalogram (EEG), eye movements using electrooculogram (EOG), and muscle tone using electromyography (EMG), in addition to heart rate, breathing patterns, and video recording. Electrophysiological PSG data (i.e. EEG, EOG, EMG) are used to score sleep stages according to international guidelines1. Sleep stages include rapid eye movement (REM), and non-REM stages: N1 and N2 representing light sleep and N3 representing deep sleep. Sleep macro-structure measures such as sleep efficiency, wake after sleep onset (WASO), and proportion of each sleep stage are extracted and routinely used in clinical evaluation. The PSG lab is an unfamiliar environment for participants. They are connected to multiple monitoring devices, including electrodes on the head and body, a chest and abdomen belt, and a cannula to monitor nasal airflow. These conditions can affect habitual sleep patterns, leading to less reliable results. The first-night and the reverse first-night effects, where individuals experience disrupted sleep due to a new environment, or improved sleep due to adaptation, respectively, are known to impact sleep2,3,4,5. Previous studies have indicated the impact of lab conditions on measurements of sleep macro-structures such as reduced sleep efficiency, more wake-after-sleep onset (WASO), and reduced number of REM cycles.6,7. When assessing sleep based on a single night in a laboratory setting, environmental factors can significantly influence the measurement. For example, some individuals may not experience REM sleep at all, preventing the quantification of RSWA. REM stage may occur later in the night due to changes in bedtime, affecting RSWA manifestation. Additionally, individuals might inadvertently opt to sleep on their back due to discomfort from electrode connections, which could impact the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI). In extreme cases, individuals may experience such discomfort that their WASO is so high that it distorts the hypnogram. For these cases, habitual sleep in the home environment can better reflect their regular sleep patterns with the additional advantage of being monitored over multiple nights and with greater comfort.

Of the many sleep disorders that can benefit from home-based sleep testing, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) presents significant opportunities and challenges. RBD is characterized by abnormal muscular tone during REM sleep (i.e., REM sleep without atonia, RSWA) and dream enactment. RBD can manifest as isolated (when occurring in the absence of overt neurological conditions), as secondary to the use of certain medications such as several antidepressants, or owing to the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD). According to the international classification of sleep disorders (ICSD-3 TR)8 and the recent guidelines of the International RBD Study Group9, RBD diagnosis requires demonstration of RSWA, quantified by monitoring muscle activity in the chin and upper limbs during REM sleep, and visual verification of dream enactment or reported history of dream enactment.

RBD has an important predictive value for alpha-synuclein neurodegeneration10. Specifically, RBD prevalence in the PD population varies between 19 and 70%11. An estimated risk for the development of neurodegenerative disorders in patients with idiopathic RBD rises up to 92% in 14 years.12 Unlike the case of macro-structures and sleep spindles, earlier studies did not adequately examine the impact of laboratory conditions on test results of RSWA and RBD. Previous work has suggested that micro-structures (such as RSWA) are relatively stable under environmental changes and night-to-night variability13,14,15,16 but to the best of our knowledge home RBD detection, based on RSWA was not previously reported.

Considering the nocturnal movements associated with high RSWA, detecting RSWA at home involves several challenges: First, it requires a home-based system capable of capturing electrophysiological data at very high stability and fidelity. Second, manual scoring of RSWA is labor-intensive, and scorers often lack confidence, complicating RBD detection. Unlike the numerous automated sleep staging and spindle detection algorithms that have been proposed in recent years17,18,19,20,21, algorithms for automated RSWA quantification16,22,23,24 are scarce and more challenging, typically involving manual supervision for mechanical artifacts.

To resolve the challenge of RSWA quantification under natural sleep conditions, we introduce in this study a semi-automated algorithm applied to data collected with a novel soft-printed electrode array optimized for home-based sleep monitoring7,25,26. In a previous report we demonstrated the validation of the wearable system for sleep macro-structures detection against PSG, introducing sensitivities of 0.908, 0.158, 0.841, 0.684, and 0.768 and specificities of 0.944, 0.986, 0.800, 0.965 and 0.981 for wake, N1, N2, N3, and REM, for adults with and without neurodegenerative conditions, respectively.

We focused on home-based quantification of RSWA, placing special emphasis on RBD detection. We set out to systematically test a semi-automatic RSWA quantification of electrophysiological data derived from the wearable system, automating also the removal of mechanical artifacts. We also aimed to explore the lab-to-home stability of RSWA and compare it to that of other sleep parameters (e.g., WASO, SE, and sleep spindles) of adults. We hypothesized that while sleep macro-structures would be affected by the environment, micro-structures such as the RSWA index and sleep spindles would be more stable. Despite the expected relative stability of micro-structures, the value of home-based recording lies in the potential ability to record them over multiple nights to reveal unique fingerprints of various medical conditions. It is nearly impractical to perform such on-going testing in the lab due to its high cost, limited availability, and inconvenience. Specifically, while RSWA has been demonstrated before in two consecutive in-lab nights16, for the first time, we aim to characterize it in the home environment. Finally, we investigated whether a semi-automatic RSWA index derived from chin EMG can achieve accurate RBD detection from home and in-clinic recordings.

Results

The wearable system used in this investigation and the data analysis process flow are shown in Fig. 1. Fifty-five participants completed a full night at the lab. 52 completed an additional night at home. Two home sessions were excluded from the RSWA analysis due to the absence of the REM stage, resulting in a total of 50 subjects. For the automated sleep spindles analysis, one home session was excluded due to artifacts, leading to a total of 51 subjects. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 5.

Sleep macro structures

Figure 2 a presents an example of a hypnogram, the graphical representation of sleep stages obtained by manual scoring of the wearable system data. Data in Fig. 2a were recorded in the lab (a 67-year-old PD female). A consecutive full-night hypnogram recorded at the home, also obtained from the wearable system, of that same patient, is presented in Fig. 2b. The differences are readily apparent: While the lab session started at 9 PM and the staging frequently varied from wake to sleep (encompassing disrupted sleep with frequent wake time during the night) and reduced REM time, the home session started only at midnight and was characterized by reduced sleep latency, less wake time (highlighted in grey) and more REM time (marked in blue). Sleep efficiency, WASO, REM, and N3 proportion for all subjects were calculated for the home and the lab sessions based on manual scoring and are presented in Fig. 2c–f. As can be readily observed in Fig. 2c–f, a poor correlation was observed between the lab and the home, ranging between 0.24 (WASO) and 0.37 (N3 %). In all cases, P-values indicate significant differences between the home and the lab. The most substantial discrepancies between lab and home were observed in WASO (see Table 1). None of the parameters exhibit a significant difference between males and females (p > 0.05). Furthermore, no significant correlations were found with age: WASO, SE, REM%, N3%, correlate at 0.275, −0.33, −0.097, and 0.146 respectively. Similarly, the correlations with AHI are −0.005, −0.013, −0.152 and −0.111 respectively.

a Hypnogram captured at the lab of PD patient with RBD (female, 67 years old). b Hypnogram captured at home from the same subject. REM and wake stages are marked in blue and grey, correspondingly. c–f Correlation plots comparing hypnogram parameters between home and lab (N = 52). The Grey dashed line represents y = x.

Sleep spindles

In Fig. 3a. we show an example of an 8 s epoch recorded simultaneously by the PSG and the wearable systems. Also shown in blue are two automatically detected spindles. In Fig. 3b we show the spindle density detected in the PSG versus the spindle density from the wearable system (N = 55). Pearson’s correlation of 0.86 was obtained. Median frequencies of spindles detected in the PSG versus the wearable system are shown in Fig. 3c, characterized by Pearson’s correlation of 0.48. A comparison between spindle density as captured by the wearable system and automatically detected at the lab and home is shown in 3d. Spindle density is characterized by Pearson’s correlation of 0.88. Median frequencies of spindles detected at the lab versus at home are shown in Fig. 3e, characterized by Pearson’s correlation of 0.90. Although there was a slight trend towards higher spindle density in the lab environment, for all parameters, P- values were non-significant. Overall, spindle density was similar across systems and different environments, while spindle median frequency differed between systems and between different electrode locations it did not change much across different environments (see Tables 2 and 3). Spindle density and spindle median frequency do not exhibit a significant difference between males and females (p > 0.05). Furthermore, no significant correlations were found with age or AHI: Spindle density and spindle frequency correlate at −0.204 and 0.001, and at 0.005 and −0.132, respectively.

a 8 s recorded simultaneously from 60-year-old PD female H%Y = 1 with both systems showing two spindles captured (light blue) in the electroencephalogram (EEG) signals. b PSG sleep spindle density versus data collected using the wearable system, with Pearson’s correlation of 0.86. c PSG spindle median frequency versus wearable, with Pearson’s correlation of 0.48. d Home versus lab wearable-based spindle density, with Pearson’s correlation of 0.88. e Home versus lab wearable-based spindle median frequency, with Pearson’s correlation of 0.90. The Grey dashed line represents y = x.

REM sleep without atonia

RSWA derived from the vPSG and wearable system data were manually and automatically assessed. A typical muscular activity is depicted in Fig. 4a. The same event was captured both in the PSG (up) and the wearable (bottom) system. We marked in green and blue shades the automated and manual scored segments, respectively (see Methods section). The specific event in Fig. 4a was scored as “any" (see Methods section). First, for the purpose of the algorithm validation, data from a subgroup of 18 subjects (18 PSG sessions and their corresponding lab wearable sessions) were manually annotated to establish the validity of the RSWA algorithm. Importantly, of these 18 subjects, 6 had RBD (5 PD, 1 iRBD). In Fig. 4b we compared the RSWAi of these subjects which was derived from the wearable system versus the RSWAi quantified from the PSG data (both using manual RSWA scoring). The RSWAi values for the wearable device and PSG were 3.3 ± 4.7 and 4.5 ± 6.1, respectively. Pearson’s correlation was 0.83 and Spearman’s correlation 0.73.

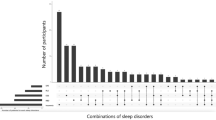

a An example of a 30 s REM epoch featuring differential EMG chin data from PSG (top) and wearable device (bottom) with automated EMG detection (green) and manual annotation (blue). b manual scoring of RSWAi derived from PSG data versus manual scoring of RSWAi derived from the wearable data. c Automated RSWAi derived from the wearable data versus RSWAi derived manually from the PSG data. d RSWAi value distribution of different subject groups at home versus in the lab (semi-automatic detection using data from the wearable system). e ROC curve analysis for binary classification including the identification of the optimal threshold of 6.269 (black dot), and AUC of 0.801 (light grey area) based on the train set. f Confusion matrix achieved from testing set data (N = 40) for binary classification of RBD versus Non-RBD.

Following this, based on the same subgroup, RSWA indices were automatically calculated using the wearable device data and compared to manually labeled scores derived from the PSG data (see Fig. 4c). RSWAi values resulting from the automated computations were 6.0 ± 4.7. Pearson and Spearman’s correlation between the automated and the manual RSWAi was 0.72 and 0.64, respectively. To further clarify our findings, a Bland-Altman representation of the data can be found in the supplementary (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, we conducted Pearson’s correlation analysis specifically for the RBD patient subgroup. The analysis yielded correlation coefficients of 0.68 (comparing manual scoring of PSG versus manual scoring of wearable data), and 0.60 (manual PSG scoring versus automated scoring of wearable data). For this sub-population, RSWA values are distributed across a relatively wide range. Excluding non-RBD subjects helps remove the floor effect, which otherwise influences the analysis. We further investigated the differences in RSWAi measurements taken in the lab compared to those taken at home. Using only automatic scoring, we analyzed a subset of 50 subjects, which included 100 sessions conducted both at home and in the lab. As described in Table 5, Among these subjects, 16 were diagnosed with RBD (13 PD, 3 iRBD). This comparison of RSWAi values quantified from home and lab sessions is shown in Fig. 4d. Spearman’s correlation between the home and the lab sessions was 0.61 and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test obtained was 0.60. RBD-diagnosed patients show the highest RSWA indices (dark grey-filled circles in Fig. 4d). Patients with mild or obstructive apnea (light grey in Fig. 4d) rise above the average of healthy controls (white) (see Table 4). RSWA index shows no significant difference between males and females (p > 0.05). Additionally, no significant correlations were found with age or AHI: the correlation with age is 0.261 and with AHI is 0.109. For the RBD classification, the same dataset was used, comprising 50 subjects and resulting in 100 sessions from both home and lab environments. When splitting the data into training and testing sets, we ensured that the same subject did not appear in both sets. RSWAi was calculated for both RBD and non-RBD. The training set consisted of 60 sessions, and the testing set contained 40 sessions. RBD-diagnosed patients were evenly distributed between both train and test sets, comprising 32% of the subjects in each subset. Figure 4e shows the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the training set, with an AUC value of 0.801. Presented in Fig. 4f is the confusion matrix achieved from the test set based on the selected optimal threshold (6.269). The chosen threshold criteria achieved a sensitivity of 83% in detecting RBD patients, 79% specificity, and 81% balanced accuracy.

Discussion

In this investigation, we utilized a semi-automatic algorithm for the quantification of RSWA and the detection of RBD in the home environment, in adults, PD, and individuals with iRBD. We further explored the lab to home variability of macro and micro-structures, highlighting the differences in their stability.

The main focus of the work reported here was RSWA quantification and RBD detection at home. The standard medical diagnosis of RBD demands RSWA quantification and vPSG (video evidence is needed to substantiate dream enactment events). Conventionally, EMG data are used to capture and quantify excessive RSWA. A reliable home-based sleep test that captures electrophysiological markers akin to those in standard PSG is therefore critical to advance RBD screening27. Several factors complicate such measurements. Monitoring RBD patients at home is complicated by their excessive movements, necessitating innovative solutions for electrode stability28. PSG requires overnight supervision by a sleep technician to manage signal quality and electrode disconnections. In this investigation, a novel system customized specifically for home sleep testing was used7. The adhesive patches contribute to overnight stability.

Another significant challenge in RSWA quantification involves labor-intensive processes, resulting in substantial variability among scorers24,29. Even with expert scorers, consensus among different raters is seldom achieved. Accordingly, a second critical element introduced in this study is the semi-automated RSWA quantification, which we implemented to avoid time-consuming and low confidence manual scoring30, including automated removal of mechanical artifacts. Frauscher et al.23 reported a Spearman’s correlation (algorithm to scorer) of 0.89 (HC=60, RBD=20). Röthenbacher et al.31 reported on a Spearman’s correlation of 0.87 (HC=10, RBD=10). Our results are comparable to those reported in previous studies when accounting for differences in patient demographics. Due to the major differences in RSWA of healthy controls and RBD patients, subject demographics affect overall correlation values.

To the best of our knowledge, RSWA quantification at home has not been reported so far, and here we were able to demonstrate, for the first time, a comparison between RSWA in the lab and at home. It is interesting to compare these results with night-to-night RSWA and RBD variability which were previously described. It has been observed that the night-to-night fluctuations in the chin RSWA index, tend to be stable, although higher night-to-night variability in RBD patients compared to healthy controls was reported15. Cygan et al.,16 reported on Spearman’s correlation of 0.55 for tonic and 0.47 for phasic activation. Our results are consistent with Spearman’s correlation of 0.6 for tonic and phasic events combined. Echoing this finding, our study reveals that the discrepancies between home and lab recordings were more pronounced for RBD than for non-RBD patients. The relative stability of RSWA is intriguing given the well-known variability in dream enactment events characteristic of RBD, which can fluctuate significantly from night to night16.

In this investigation, we accurately detected patients with RBD through RSWA quantification using a home-compatible system. We achieved specificity and sensitivity for the test set of 79% and 83%, respectively (see Fig. 4f). As was highlighted in previous reports, it is important to acknowledge the role of artifact removal in the overall RSWA quantification using semi-automatic algorithms. Cesari et al. 24 reported a sensitivity of 72% at specificity of 100% upon removal of specific artifacts such as arousal, snoring, and technical artifacts. Notably, when only arousal removal was considered, the sensitivity decreased to 41%. Frauscher et al.23 demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 45%, respectively. With additional manual artifact correction, the specificity improved to 67%. We integrated an EMG validation process into the RSWA quantification to automatically remove artifacts. This step improved the efficiency of the overall process, reduced manual work, and improved the RBD detection accuracy.

Recent studies have explored alternative methods for detecting RBD outside of traditional lab settings, such as utilizing actigraphy data in conjunction with machine learning algorithms32,33. For instance, Brink-Kjaer et al.34 reported successful ambulatory detection of isolated RBD, achieving a sensitivity of 95.2% and a precision of 90.9%. Despite these promising results, these studies used small homogeneous groups of participants with overt iRBD. These systems lack electrophysiological insights and as such may be less accurate in subtle cases (i.e., phasic muscle twitches) or screening for iRBD in the general population. Further research is needed to gain widespread acceptance within the medical community. Nonetheless, the various studies using wearable devices at home, all contribute to the surmounting evidence in favor of transitioning from lab-based PSG clinics.

In this study, we further investigated the variability of macro structures between lab and home settings, highlighting the instability that can occur across these environments. Differences in sleep macro-structures between home-based and lab-based studies are widely acknowledged3,35. These differences can be observed in questionnaires, sleep-tracking apps, actigraphy, ECG-based devices, and a multitude of other sleep-monitoring devices35. Using electrophysiological data, we observed this effect in four sleep macro-structures. We found significant differences and poor correlations between the home and lab sessions. As in previous reports4,6,7,35,36, lab sessions were characterized by higher WASO, lower sleep efficiency, and less REM. We also observed a significantly lower N3 stage percentage at home. It should be noted that the analysis we reported here is built on aggregated data from different subject groups (HC, PD, and RBD). Figure 3b, illustrates an extreme case recorded in this study of a PD patient with RBD. Given that the home recording is a better representation of the patient’s sleep routine, it is evident the lab recording started too early, likely during the patient’s wake-maintenance zone when falling asleep is challenging. The lab recording shows a forced advancement of sleep by three hours. As sleep routines vary between people and countries, a standardized bedtime can not be universally applied37. This example emphasizes how lab settings can potentially influence individual sleep patterns and outcomes. These results can be compared with previous reports of insomnia patients35. It is interesting that despite decades of research, the extent to which lab setting affects the sleep of different patient populations is still poorly characterized35,38 and further investigations can better illuminate differences in macro-structures at home.

Unlike the high night-to-night variability of sleep macro-structures, micro-structures, such as sleep spindles and RSWA, are considered more stable13. Levendowski et al.14 examined sleep spindle characteristics in two consecutive home sessions in patients diagnosed with insomnia, depression, and obstructive sleep apnea. Employing automated detection of sleep spindles, they demonstrated high stability in spindles features such as duration and slow spindle proportion, demonstrating night-to-night stability of spindles. Here we established a very similar phenomenon for the home environment, for healthy and RBD subjects.

We also note that although spindle detection was very accurate, a comparison of sleep spindle detection with PSG and the wearable systems, showed a substantial Pearson’s correlation of 0.86. This indicates that although the pre-frontal location of the wearable electrodes does not affect the ability to capture the spindle-associated brain activity originating from deep brain regions, the relatively low correlation in spindle frequency (0.48), implies that the location may affect the temporal frequency of captured sleep spindle features. Since sleep spindles may be described as a propagating wave with frequency modulation39,40,41, different locations of electrodes may capture different aspects of the sleep spindle. In other words, owing to differences in sleep spindle topographical distributions across the skull, their features may be captured differently from different locations. Importantly, when comparing the sleep spindle frequency of the same subject at home and the lab, almost a perfect agreement is achieved (0.90). The latter arises from the use of similar recording devices (i.e., wearable) and a similar recording location.

This study has several limitations. First, our sample size was rather small. While RBD is prevalent in our dataset, the representation of RBD without PD is limited. Despite significant differences in demographics between groups, we observe no significant correlations between macrostructures, spindles, or RSWA (our primary interests) and age, gender, or AHI. Second, body movements in some cases led to signal artifacts and system disconnections (as in PSG). Third, the described algorithms are only semi-automated. Sleep scoring was performed manually, and served as a base for the automated micro-structures analysis. We have previously shown that automated scoring for challenging cases is insufficient, without additional training. More data in the future may facilitate the implementation of a fully automated approach. Moreover, after a sleep expert diagnosed RBD using RSWAi from vPSG data, we aimed to compare the RSWAi from vPSG with that derived from the wearable device. Manual scoring of RSWA is time-consuming, resource-intensive, and results obtained with a subset of 18 subjects appeared to converge. Moreover, while the main advantage of the wearable system is the ability to measure an individual’s sleep for multiple nights, in this investigation, participants had only one night at the lab and one at home. Future studies will investigate the night-to-night variation, potentially yielding more accurate results by integrating patterns observed across consecutive nights.

This investigation underscores the advantages of home-based sleep studies. By overcoming the “first-night effect” observed in the lab setting and revealing home-based sleep micro-structures in a natural environment, sleep evaluation can be significantly enhanced. This report highlights the utilization of a semi-automated algorithm designed for a novel wearable system to assess sleep micro-structures in adults and those who are diagnosed with PD. Specifically, a semi-automatic detection method of RSWA for accurate RBD detection showed high accuracy. The better stability of micro-structures, such as sleep spindles and RSWA, across nights, is in stark contrast with the significant differences in sleep efficiency, WASO, and N3 and REM stage percentages.

Methods

The study cohort included both healthy controls (HC; n = 24), patients with PD (n = 28), and individuals diagnosed with isolated RBD (iRBD; n = 3) as presented in Table 5. PD patients were included due to their high RBD prevalence. Specifically, in this study, 54% of PD patients were diagnosed with RBD. Participants underwent one night of sleep assessment in a clinical sleep laboratory while using both PSG and the wearable system. They were also asked to use the wearable system for an additional night at home.

Participants

Healthy participants were included if they were between 40 and 80 years old and had no diagnosed neurological or psychiatric disorders (according to DSM-IV). Patients with PD were included if they were diagnosed based on the MDS criteria42, in Hoehn and Yahr stage I-III43 with no additional neurological or psychiatric disorders. RBD was diagnosed by a sleep-specialized neurologist based on full PSG. None of the participants were using psychiatric or sleep medication at the time of assessment. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee Review Board at Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (TASMC) in accordance with the Helsinki guidelines and regulations for human research. All participants signed an informed written consent before participation. Demographic data included age, gender, disease duration, Hoehn and Yahr stage, and Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI).

Procedures

All participants were invited to a full night video PSG (vPSG) test. Male participants were asked to shave before arrival. Participants were fitted with the wearable system in conjunction with the vPSG system. At the beginning of each session, a calibration stage with both systems was conducted according to the AASM manual1. For home experiments, data were collected only with the wearable system, which was operated by a trained technician. The system was detached manually by the user in the morning and the recording unit was returned. The data was uploaded to a cloud server for further analysis.

Wearable system

The electrode arrays have been previously described7,25,44,45. Briefly, carbon electrodes and silver traces are screen-printed on a thin, flexible film. A second double-sided adhesive film is utilized to adhere the electrode array to the skin and to insulate the silver traces. The electrode arrays incorporate three (four in an older version25) EEG electrodes (positioned on the forehead), two EOG electrodes (on the right side of the eye), and two EMG electrodes located on the chin mentalis muscle. A miniature proprietary data acquisition unit (DAU, by X-trodes Ltd.; dimensions: 42 × 42 x 14.8 mm, weight: 20 gr) is mounted on the head using a headband. The DAU supports unipolar channels (2 μV noise RMS, for the 0.5 and 700 Hz frequency range) with a sampling rate of 4000 S/s, 16-bit resolution, and an input range of ± 12.5 mV. A 620 mAh battery supports DAU operation for a duration of up to 16 hr. Continuous data transfer facilitated through Bluetooth (BT) module. An Android application enables the operator to define session settings, perform calibration, and observe the data in real-time. The data is stored on a built-in SD card and later transferred to the cloud for offline analysis. An internal (or gel in early experiments; Natus) ground electrode was placed on the right mastoid region. Previous report7 demonstrated the ability of the wearable system to collect data suitable for manual sleep scoring. The DAU and the electrode array are shown in Fig. 1.

Video Polysomnography (vPSG)

vPSG data were collected at the Institute for Sleep Medicine at TASMC. The vPSG tests were conducted with the Natus (NDx) system using the RemLogic software (Version 4.0.1, Embla) and standard electrodes placement (gold cup, Natus); six EEG electrodes (C3, C4, F3, F4, O1, O2), two EOG (left and right), three EMG electrodes located in the submental area (Chin1,chin2, ChinZ), and both anterior tibialis and flexor digitorum superficialis muscles (250 S/s). In addition, oronasal airflow, and a microphone were used. Thoracic and abdominal respiratory effort, position sensor, oxygen saturation, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were collected.

Data pre-processing

PSG and wearable system data were pre-processed using RemLogic software (Version 4.0.1, Embla) and Python (version 3.9), respectively. Both PSG and the wearable system data were filtered following AASM guidelines1: EEG and EOG signals were filtered using a 4th-order Butterworth bandpass filter with a frequency cutoff of 0.3-35 Hz. EMG signals were filtered using a 4th-order Butterworth bandpass filter with a frequency cutoff of 10−100 Hz. All signals were additionally filtered with a notch filter with a center frequency of 50 Hz and a Q factor of 20. For the PSG data, the following differential channels were defined: F4-M1, F3-M2, C4-M1, C3-M2, O1-M2, O2-M1, E2-M2, E1-M2, Chin1-Chinz, Chin2-Chinz. All channels of the wearable system were measured against its ground electrode (M2). Lights off and lights on times were defined manually by a sleep technician and the wearable system signals were confirmed respectively. Home test time boundaries were set according to subjects’ reports. Data were exported as European Data Format (EDF) files.

Sleep scoring

Sleep stages for both PSG and the wearable system recordings were classified manually by sleep specialists certified by the European Sleep Research Society. Analysis was performed using RemLogic software (Version 4.0.1, Embla) and Alice Sleepware software (version 2.7.43, Respironics), respectively.

Sleep macrostructure parameters

Various sleep macrostructures were extracted. In particular, we examined sleep efficiency, WASO, REM, and N3 proportions, owing to their widespread use. Values were calculated as follows based on manual sleep scoring:

*Sleep onset is defined as the start of the first epoch scored as any stage other than stage W.

Finally, the effects of sex, age, and AHI on sleep macro-structures were examined using paired t-test and Person correlation.

Automated spindle detection

Sleep spindles were automatically detected from both PSG and wearable data, using the YASA algorithm46, an open-source adaption of the A7 algorithm18 which was validated against human scoring, with performances equivalent to a human expert. YASA uses 3 different thresholds (relative sigma power, root mean square, and correlation). The A7 algorithm uses four thresholds (absolute and relative power, covariance, and correlation). The YASA algorithm determines the spindle start and end points by locating the onset of characteristic spindle activity, e.g., finding where two out of the three thresholds were crossed. EEG channels were down-sampled to 250 Hz and filtered according to the AASM guidelines1. Spindles were detected using YASA during the non-REM N2 stage as scored manually earlier. Spindles parameter definitions included a frequency band of 11−16 Hz, duration of 0.5−2 s1, and minimum distance of 0.5 s between two separate spindles. Spindles were detected in all EEG channels simultaneously. Spindles captured from different channels were considered the same if their start/end time fell within the same second. Detected sleep spindles with amplitude less than 20 uV or more than 80uV were excluded from the analysis. For each spindle detection, the median frequency derived from a Hilbert transform of the band-pass 1−30 Hz filtered signal was calculated. Spindle density was calculated as the number of spindles detected divided by N2 stage duration (min). The results were compared between PSG and wearable to establish the validity of the YASA algorithm to detect sleep spindles captured by the wearable system in both HC and PD/RBD, and between home and lab to explore lab-to-home variability. The effects of sex, age, and AHI on sleep spindles were examined using paired t-test and Pearson’s correlation.

Manual RSWA quantification

RSWA for both vPSG and wearable system recordings was quantified by sleep specialists certified by the European Sleep Research Society. Manual scoring of RSWA was performed according to the AASM1 and SINBAR47 criteria, by identifying “any" (i.e. phasic and/or tonic) muscular activity in the chin channel. RSWA index (RSWAi) was quantified using the ratio of REM sleep duration with “any" chin muscular activity to total REM sleep duration.

Automatic RSWA quantification

Chin EMG data from a subgroup of 18 subjects (HC=9; PD non-RBD=3; PD RBD=5; and iRBD=1) were used for the development and validation of the RSWA quantification algorithm. We compared RSWA prevalence identified by manual scoring of vPSG data to that of wearable data, as well as to the automatically quantified RSWA prevalence. RSWA was automatically detected from both PSG and wearable data. First, Chin EMG channels were down-sampled to 500 Hz and filtered using a 4th-order Butterworth high-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 30 Hz, and a 4th-order notch filter (Q factor=30) centered at 50 Hz to reduce power-line interference. Manual sleep scoring was utilized to identify REM periods, with the analysis focused solely on these specific times. The algorithm includes two main steps and was conducted for each 30 s REM epoch independently: First, mean absolute amplitude values (MAAV)48 were calculated, along with its preceding 10 s and following 10 s. The MAAV computation was performed on time windows of 0.1 s with 50% overlap as follows:

where N represents the number of samples within each window, and xi denotes the amplitude of the i-th EMG sample. Shapiro-Wilk normality test was conducted twice: first on the filtered EMG signal, and second on its derived MAAV vector. If both Shapiro test statistics crossed specific thresholds (0.95 and 0.9 respectively) the REM epoch was considered as not having any EMG activation and was not proceeded to further analysis. The second step utilized an adaptive threshold for each epoch, set at the 55th percentile of the MAAV vector. This threshold determined the segmentation of EMG muscle activity, where EMG segments were defined when the MAAV vector exceeded this threshold. For each EMG segment the following features were calculated: (a) Median frequency (b) Root mean square (c) Zero-crossing rate: Crossing points with variation smaller than the MAAV-derived threshold removed. (d) FFT peaks Segments considered as having an EMG activation if all of the following criteria were met:

-

Median frequency < 115 Hz

-

Root mean square > 2 × predefined MAAV derived threshold

-

Zero-crossing rate > 140

-

FFT peaks were not found to be power line interference harmonics

Finally, RSWAi was calculated by dividing the duration of EMG activity detected events by the total REM sleep time. To validate the algorithm, automatic detections derived from wearable data were compared with manual PSG detection and with wearable manual detection. Home-based results were compared to the lab to explore stability. The comparisons involved Pearson and Spearman correlations for both algorithm-manual and home-lab results. As mild or obstructive apnea can affect muscle tone, potentially causing patients’ RSWAi to rise, statistical analysis was performed separately for RBD patients, non-RBD subjects with AHI greater than 15, and non-RBD subjects with AHI smaller than 15. These analyses included Pearson and Spearman correlation, Wilcoxon signed-rank, and paired t-tests. The effects of sex, age, and AHI on RSWA were examined using paired t-test and Pearson’s correlation.

RBD classification

An optimization process was employed to determine the optimal threshold for RBD detection based on the novel algorithm outputs, RSWAi. The ideal threshold was explored for its ability to identify subjects with a clinical diagnosis of RBD. Analysis was conducted on both home and lab wearable system sessions. RSWA indices as calculated by the algorithm were split into a randomly balanced 60% training set and a 40% testing set. Training and testing sets consisted of different subjects to avoid data leakage. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to assess the ability to differentiate between RBD and non-RBD subjects. The optimal threshold was selected by maximizing Youden’s Index (sensitivity-specificity). Subsequently. This threshold was applied to the test datasets for the evaluation of the RSWAi. Sensitivity, specificity, and balanced accuracy were calculated to assess the performance of the novel criteria.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Code availability

The code used for data analysis in this study is available upon reasonable request. Interested researchers can contact the corresponding author for access to the code.

References

Berry, R.B., G. C. H. S. L. R. M. C., Brooks, R. & BV, V. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Ter (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, Chichester, 2020), 2.6 edn.

Agnew, H. W., Webb, W. B. & Williams, R. L. The first night effect: An eeg study of sleep. Psychophysiology 2, 263–266 (1966).

Hauri, P. J. & Olmstead, E. M. Reverse first night effect in insomnia. Sleep 12, 97–105 (1989).

Riedel, B. W., Winfield, C. F. & Lichstein, K. L. First night effect and reverse first night effect in older adults with primary insomnia: does anxiety play a role? Sleep. Med. 2, 125–133 (2001).

Ding, L., Chen, B., Dai, Y. & Li, Y. A meta-analysis of the first-night effect in healthy individuals for the full age spectrum. Sleep. Med. 89, 159–165 (2022).

Bruyneel, M. et al. Sleep efficiency during sleep studies: Results of a prospective study comparing home-based and in-hospital polysomnography. J. Sleep. Res. 20, 201–206 (2011).

Oz, S. et al. Monitoring sleep stages with a soft electrode array: Comparison against vpsg and home-based detection of rem sleep without atonia. J. Sleep Res. 32, E13909 (2023).

International Classification of Sleep Disorders (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, Darien, IL, 2023), 3rd edn.

Cesari, M. et al. Video-polysomnography procedures for diagnosis of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) and the identification of its prodromal stages: guidelines from the International RBD Study Group. Sleep 45, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab257. Zsab257, https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-pdf/45/3/zsab257/42853649/zsab257.pdf (2021).

Malhotra, R. & Avidan, A. Y. Neurodegenerative disease and rem behavior disorder. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 14, 474–492 (2012).

Zhang, X., Sun, X., Wang, J., Tang, L. & Xie, A. Prevalence of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (rbd) in Parkinson’s disease: a meta and meta-regression analysis. Neurol. Sci. 38, 163–170 (2017).

Iranzo, A., Santamaria, J. & Tolosa, E. The clinical and pathophysiological relevance of rem sleep behavior disorder in neurodegenerative diseases. Sleep Med Reviews 13, 385–401 (2009).

Azumi, K. & Shirakawa, S. Characteristics of spindle activity and their use in evaluation of hypnotics. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/5/1/95/2750258 (1982).

Levendowski, D. J. et al. The accuracy, night-to-night variability, and stability of frontopolar sleep electroencephalography biomarkers. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 13, 791–803 (2017).

Ferri, R. et al. Night-to-night variability of automatic quantitative parameters of the chin EMG amplitude (atonia index) in REM sleep behavior disorder. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 9, 253–258 (2013).

Cygan, F., Oudiette, D., Leclair-Visonneau, L., Leu-Semenescu, S. & Arnulf, I. Night-to-night variability of muscle tone, movements, and vocalizations in patients with rem sleep behavior disorder. J. Clin Sleep Med. 6, 551–555 (2010).

Tsanas, A. & Clifford, G. D. Stage-independent, single lead eeg sleep spindle detection using the continuous wavelet transform and local weighted smoothing. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 181 (2015).

Lacourse, K., Delfrate, J., Beaudry, J., Peppard, P. & Warby, S. C. A sleep spindle detection algorithm that emulates human expert spindle scoring. J. Neurosci. Methods 316, 3–11 (2019).

Jiang, D., Ma, Y. & Wang, Y. A robust two-stage sleep spindle detection approach using single-channel eeg. J. Neural. Eng. 18, 026026 (2021).

Wei, L. et al. Deep-spindle: An automated sleep spindle detection system for analysis of infant sleep spindles. Comput. Biol. Med. 150, 106096 (2022).

Kaulen, L., Schwabedal, J. T., Schneider, J., Ritter, P. & Bialonski, S. Advanced sleep spindle identification with neural networks. Sci. Rep. 12, 7686 (2022).

Ferri, R., Gagnon, J. F., Postuma, R. B., Rundo, F. & Montplaisir, J. Y. Comparison between an automatic and a visual scoring method of the chin muscle tone during rapid eye movement sleep. Sleep. Med. 15, 661–665 (2014).

Frauscher, B. et al. Validation of an integrated software for the detection of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 37, 1663–1671 (2014).

Cesari, M. et al. Interrater sleep stage scoring reliability between manual scoring from two european sleep centers and automatic scoring performed by the artificial intelligence-based stanford-stages algorithm. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 17, 1237–1247 (2021).

Shustak, S. et al. Home monitoring of sleep with a temporary-tattoo EEG, EOG and EMG electrode array: A feasibility study. J. Neural Eng. 16, 026024 (2019).

Hanein, Y. & Mirelman, A. Monit. sleep. Disord. home: How can. wearable electrode arrays help? Bioelectron. Med. 3, 175–177 (2020).

Wood, E., Westphal, J. K. & Lerner, I. Re-evaluating two popular EEG-based mobile sleep-monitoring devices for home use. J. Sleep. Res. 32, 1–11 (2023).

Brigham, D. et al. Comparison of artifacts between paste and collodion method of electrode application in pediatric EEG. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pract. 5, 12–15 (2020).

Frauscher, B. et al. Video analysis of motor events in REM sleep behavior disorder. Mov. Disord. 22, 1464–1470 (2007).

Bliwise, D. L. et al. Inter-rater agreement for visual discrimination of phasic and tonic electromyographic activity in sleep. Sleep 41, 1–6 (2018).

Röthenbacher, A. et al. Rbdtector: an open-source software to detect rem sleep without atonia according to visual scoring criteria. Sci. Rep. 12, 20886 (2022).

Liguori, C. et al. The evolving role of quantitative actigraphy in clinical sleep medicine. Sleep. Med. Rev. 68, 101762 (2023).

Raschellà, F., Scafa, S., Puiatti, A., Moraud, E. M. & Ratti, P. L. Actigraphy enables home screening of rapid eye movement behavior disorder in parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 93, 317–329 (2023).

Brink-Kjaer, A. et al. Ambulatory Detection of Isolated Rapid-Eye-Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder Combining Actigraphy and Questionnaire. Mov. Disord. 38, 82–91 (2023).

Sleep in the laboratory and sleep at home: Comparisons of older insomniacs and normal sleepers. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/20/12/1119/2749958 (1997).

White, P., Gibb, J., Wall, J. M. & Westbrook, P. R. Home monitoring-actimetry assessment of accuracy and analysis time of a novel device to monitor sleep and breathing in the home. https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/18/2/115/2749621 (1995).

Willoughby, A. R., Alikhani, I., Karsikas, M., Chua, X. Y. & Chee, M. W. Country differences in nocturnal sleep variability: Observations from a large-scale, long-term sleep wearable study. Sleep. Med. 110, 155–165 (2023).

Kukwa, W., Migacz, E., Lis, T. & Ishman, S. L. The effect of in-lab polysomnography and home sleep polygraphy on sleep position. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-020-02099-w (2021).

Astori, S., Wimmer, R. D. & Lüthi, A. Manipulating sleep spindles - expanding views on sleep, memory, and disease. Trends neurosciences 36, 738–748 (2013).

Walker, M. P. & Stickgold, R. Sleep, memory, and plasticity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 57, 139–166 (2006).

Schönwald, S. V., Carvalho, D. Z., Dellagustin, G., de Santa-Helena, E. L. & Gerhardt, G. J. Quantifying chirp in sleep spindles. J. Neurosci. Methods 197, 158–164 (2011).

Postuma, R. B. et al. Mds clinical diagnostic criteria for parkinson’s disease. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 30, 1591–1601 (2015).

Hoehn, M. M. & Yahr, M. D. Parkinsonism. Neurology 17, 427–427 (1967).

Inzelberg, L., David-Pur, M., Gur, E. & Hanein, Y. Multi-channel electromyography-based mapping of spontaneous smiles. J. Neural Eng. 17, 026025 (2020).

Inzelberg, L., Rand, D., Steinberg, S., David-Pur, M. & Hanein, Y. A wearable high-resolution facial electromyography for long term recordings in freely behaving humans. Sci. Rep. 8, 2058 (2018).

Vallat, R. & Walker, M. P. An open-source, high-performance tool for automated sleep staging. eLife 10, e70092 (2021).

Frauscher, B. et al. Normative emg values during rem sleep for the diagnosis of rem sleep behavior disorder. Sleep 35, 835–847 (2012).

Cesari, M. et al. Validation of a new data-driven automated algorithm for muscular activity detection in rem sleep behavior disorder. J. Neurosci. Methods 312, 53–64 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the study for their time and effort and thank Shlomit Katzav, Chen Zanzuri and Reut Rital for their assistance with PSG data collection. This project was supported by the NNE program (TEVA pharmaceuticals), The Israel Science Foundation (1355/17), and the USA MED Research Acquisition Activity, Department of Defense awarding office, through the FY19 Award Mechanism: Parkinson’s Research Program-Investigator-Initiated under Award No. W81XWH2010468. The funding agencies were not involved in the design, acquisition, or interpretation of the findings, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.P., S.O., and A.G. developed, and performed, the data analysis. D.P., S.O., and A.G., M.C., and Y.H. steered the analysis process and result presentation. D.W. and R.T. performed the neurological evaluation. D.W. and I.D. performed the manual sleep scoring. A.D. participated in data curation. A.M. and Y.H. acquired funding, conceptualized the study, and supervised the project and the data analysis. Y.H., S.O., D.P., and A.M. wrote the first manuscript draft. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.P., S.O., A.G., and Y.H. declare a financial interest in X-trodes Ltd, which developed the screen-printed electrode technology used in this paper. These authors have no other relevant financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Possti, D., Oz, S., Gerston, A. et al. Semi automatic quantification of REM sleep without atonia in natural sleep environment. npj Digit. Med. 7, 341 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01354-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01354-8

This article is cited by

-

Dry-printed electrodes for transcutaneous electrical stimulation of innervated muscles: Towards wearable and closed-loop stimulation

Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation (2025)

-

Novel technologies for REM sleep behavior disorder detection for home screening in Parkinson’s disease and related alpha-synucleinopathies

npj Parkinson's Disease (2025)

-

Facial muscle mapping and expression prediction using a conformal surface-electromyography platform

npj Flexible Electronics (2025)