Abstract

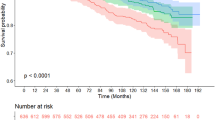

Premature frailty is a critical challenge for young breast cancer survivors (YBCSs), impacting their health and perpetuating gender inequality through heightened vulnerability and marginalization. While digital health shows promise in frailty screening, its effectiveness for comprehensively managing frailty remains inconclusive. This randomized controlled trial, registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2200058823), tests the “AI-TA” program’s efficacy on premature frailty and quality of life in YBCSs. The intervention group received a gender- and generation-sensitive program combining artificial intelligence interactions and humanities skills. The control group received 12 weeks of online information support. Both groups improved in frailty dimensions (P < 0.05); the intervention group showed notable enhancements in psychological (P = 0.013) and social frailty (P < 0.001). Quality of life also improved more in the intervention group from T1 to T2 (β = 15.384, 95% CI:13.028–17.740, P < 0.001). Results show a gender- and generation-sensitive digital humanistic program can optimize frailty management, promoting survivorship and gender equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide1. A staggering 50.5% of breast cancer survivors (BCSs) report experiencing pre-frailty or frailty2. Young BCSs (YBCSs), particularly those with lower income and social status, experience a faster decline in physical, psychological, and social functioning compared to the general population and older survivors. This decline leads to decreased resilience, diminished adaptive capacity, and increased vulnerability to stressors3,4,5. We describe this accelerated progression of frailty status as “premature frailty”. Notably, cohort studies indicate that young female survivors have a significantly greater risk of frailty and comorbidities than their male counterparts (44.6% vs. 15.6%; 59% vs. 37%)6,7. Thus, premature frailty is a critical gender- and age-specific health issue that demands urgent attention.

One significant contributing factor is that young females often undergo combination treatments which expedite aging process and exacerbate frailty. Treatments involving radiation, genotoxic therapies, and chemotherapy can accelerate frailty by causing cardiovascular issues, muscle loss, neuropathy, and cognitive decline8,9. Estrogen treatments may increase skeletal complications, such as sarcopenia, and reduce physical activity10. These treatments also lead to social resource loss and dysfunction in social roles, further exacerbating YBCSs’ vulnerability and marginalization within their communities11,12,13. Particularly for Chinese women, who bear primary responsibilities for caring for children and elderly relatives, frailty intensifies their caregiving burden14. This often forces them to withdraw from the labor market, exacerbating the “She-Cession”15. Consequently, they experience a loss of traditional gender roles, resulting in guilt, powerlessness, and other negative emotion. This impact is especially pronounced among Chinese YBCSs, who face specific societal role expectations around maternity and work responsibilities16. In conclusion, breast cancer and its treatment profoundly impact the physical, physiological, and social frailty of YBCSs. Furthermore, the cumulative deficit resulting from multiple side effects of cancer significantly heightens the risk of premature frailty and related mortality among those diagnosed at a younger age17. As these survivors navigate a longer duration of vulnerability, the accumulation of challenges exacerbates their frailty, underscoring that premature frailty is a dynamic and preventable syndrome prevalent among YBCSs3,4,18,19.

Despite increasing attention to the gender disparities that contribute to adverse health outcomes among YBCSs—including higher risks of multi-morbidity, mortality, social discrimination, isolation, and poor quality of life2,20, the comprehensive spectrum of frailty status among YBCSs remains limited. Within frailty management, studies have focused on screening for physical frailty. Fatigue and physical function are identified as frequent criteria7,20. However, few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have addressed physical, psychological, and social frailty among YBCSs. Frailty management encounters several barriers. Firstly, providing precise support tailored to the dynamic characteristics of premature frailty proves challenging19,21. Then, implementing clinical-based premature frailty interventions at scale and over the long-term pose difficulties, as clinical health workers often lack the time and skills necessary to deliver such support22. These challenges underscore the need for innovative approaches and comprehensive interventions that address the multi-faceted nature of frailty among YBCSs, thereby improving their overall well-being.

Digital health provides a flexible and innovative approach to frailty management, offering systems, sensors, and software that enable continuous monitoring of frailty and quality of life for BCSs. This technology has significant potential to deliver readily accessible support to the substantial population of YBCSs during their cancer survivorship trajectory23. Researchers have developed platforms integrating self-administered questionnaires, wearable accelerometers, and electronic health records to collect diverse, real-world data encompassing functional status, cognitive function, social support, emotional well-being, and nutritional status, providing a comprehensive understanding of cancer survivors’ frailty24,25,26,27. Although there are increased digital systems for frailty monitoring, existing systems predominantly focus on elder cancer survivors’ psychical frailty24,25,26,27. Only one study, to date, has examined frailty status among young adult cancer survivors using remote assessment methods, and no reported systems that integrate both monitoring and intervention components for comprehensive psychical, psychological, and social frailty7. Moreover, many digital health systems with intervention function were developed for BCSs in general without considering the age differences. These systems focus on the passive dissemination of information and lack humanistic values, diminishing their efficiency, adherence, and potentially continuing inequities, especially for disadvantaged women28,29,30.

The field of digital humanities has emerged to address these gaps, aiming to leverage information technology to resolve critical issues with a human-centered focus31. Humanism emphasizes the specific circumstances that shape individuals, and the data collected also reflect those unique contexts32. Therefore, it is essential to understand YBCSs within their environments and to consolidate available resources. The ‘mixed methods’ approach is a useful template in developing the digital humanities. Advocates for intersectional methodologies, such as Figueroa, emphasize the importance of considering various social identities, such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and culture, to address gender inequities in digital health30. In response to the distinct needs of YBCSs, a gender- and generation-sensitive (G2G) digital health system named “AI-TA” has been developed.

The “AI-TA” WeChat Mini Program is grounded in the “Digital for Humanistic” philosophy, reflecting dual meanings. “AI” signifies “love” (爱) in Chinese, while “TA” refers to “her” (她), embodying an ethos of care directed at women. Furthermore, the name signifies the program’s use of AI algorithms to deliver personalized health information tailored to YBCSs. By integrating a humanistic approach with advanced AI technology, “AI-TA” addresses the specific needs of YBCSs through a robust system that monitors frailty and provided targeted intervention. Using a humanism framework, the system considers the socio-ecological environment of YBCSs, spanning individual, interpersonal, community and social environment, to inform G2G information setting33. Both quantitative and qualitative data collection were utilized, with a particular emphasis on social identities, to deliver tailored support. This initiative represents an innovative advancement toward promoting health equity and supporting vulnerable populations in a more personalized and comprehensive way.

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a G2G digital support to monitor and alleviate the physical, psychological, and social premature frailty, consequently enhancing the quality of life for YBCSs. The primary endpoint was to examine the differences in premature frailty in two groups: YBCSs received G2G digital support, and YBCSs received general information support.

Results

Participants’ flow

The inclusion criteria for participant selection, outlined in the Methods section, targeted young Chinese females aged 18–45 diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer. This age range aligns with the WHO’s definition of youth (18–44), marks the pre-menopausal stage, and precedes the first peak incidence of breast cancer (ages 45–55) in Chinese women, reflecting its relevance to life course and cultural roles34. Data were gathered via surveys at three time points: the start (T0), after 4 weeks (T1), and after 12 weeks (T2). Initially, 124 individuals were enrolled in the study. However, 9 individuals (3.2% of the intervention group, totaling 2 out of 62, and 11.3% of the control group, totaling 7 out of 62) did not complete the initial survey even after receiving reminders. Consequently, the final data analysis included 115 YBCSs, with 60 in the intervention group and 55 in the control group. The attrition rate at both T1 and T2 was 1.7% (2 out of 115). A diagram depicting the progression of participants through the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Participants’ characteristics

Table 1 provides an overview of the sociodemographic and health characteristics of YBSCs at baseline (T0). Single-factor analysis of the scores of physical frailty, psychological frailty, and social frailty can be found in Supplementary Table 1. In this study, the participants had an average age of 40.21 (SD 4.24) years. The average time since diagnosis was 1.04 (SD 0.58) years. Approximately 90% of YBCSs were living in urban areas and were married. Nearly 95% of YBCSs had invasive breast cancer, and approximately 65% were diagnosed with stage II or stage III breast cancer. Treatments received were surgery (91.3%;105/115), chemotherapy (84.3%; 97/115), radiotherapy (38.3%; 44/115), endocrine therapy (38.3%; 44/115), and targeted therapy (42.6%; 49/115). A total of 46.1% (53/115) had both surgical and adjuvant treatment. Additionally, Traditional Chinese Medicine was employed by 29.6% (34/115). No significant differences were observed in the demographic characteristics between the intervention and control groups.

The effects on reduction of premature frailty (primary outcomes)

The study primarily focused on assessing premature frailty across multiple dimensions, including physical, psychological, and social aspects.

Physical premature frailty

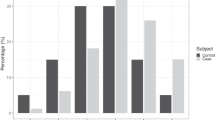

The most common criteria for physical premature frailty in YBCSs are fatigue, physical symptoms (PHYS), and PA, which indicate exhaustion, weakness, and low energy expenditures. These indicators were assessed to capture the changes in frailty, as shown in Table 2. At baseline, most participants (100/115, 87.0%) experienced a fatigue issue, with 57.4% reporting mild fatigue and 29.6% reporting moderate fatigue. Similarly, most participants reported low or moderate levels of physical activity (100/115, 87.0%) and physical symptoms (111/115, 96.6%). Within the generalized estimating equations model, the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) and PHYS scores showed significant group and time effects (P < 0.001) (see Figs. 2 and 3). The differences between the intention-to-treat (ITT) group and control group were statistically significant for BFI (β = 0.685, 95% CI, 0.448–0.922, P < 0.001) and PHYS (β = 0.207, 95% CI, 0.105–0.310, P < 0.001). The ITT group had significant decreases in the BFI scores from the T0 to T1. However, PA based on metabolic equivalents (METs) showed a significant group effect only (β = −378.710, 95% CI, −705.240 to −52.180, P = 0.023). All participants’ PA levels increased with no statically significant and were maintained at moderate over time (see Fig. 4).

a Box plots offer a visual method for examining the distribution of fatigue changes across different groups. Each plot displays the median, quartiles, along with the maximum and minimum values at each time point. b The mean change in the fatigue over time is presented along with standard error bars. P values are indicated by stars, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

a Box plots offer a visual method for examining the distribution of PHYS changes across different groups. Each plot displays the median, quartiles, along with the maximum and minimum values at each time point. b The mean change in the PHYS over time is presented along with standard error bars. P values are indicated by stars, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

a Box plots offer a visual method for examining the distribution of PA changes across different groups. Each plot displays the median, quartiles, along with the maximum and minimum values at each time point. b The mean change in the PA over time is presented along with standard error bars. P values are indicated by stars, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Psychological premature frailty

Psychological frailty was predominantly at low or moderate levels for most of the participants (92/115, 80.0%). Significant time, group, and time × group interaction effects were found for psychological symptoms (PSYCH), with the ITT group showing a greater decrease than the control group from T1 to T2 (β = −0.394, 95% CI, −0.469 to −0.320, P < 0.001) (see Fig. 5).

a Box plots offer a visual method for examining the distribution of PSYCH changes across different groups. Each plot displays the median, quartiles, along with the maximum and minimum values at each time point. b The mean change in the PSYCH over time is presented along with standard error bars. P values are indicated by stars, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Social premature frailty

In terms of social frailty, almost all participants had moderate or adequate support (112/115, 97.4%), with a mean score of 37.87 ± 7.76 on the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS). The SSRs scores showed significant time and time × group interaction effects. Both groups had significant increases in social support over time, with the ITT group showing a greater increase than the control group from T1 to T2 (β = 7.145, 95% CI, 6.053–8.237, P < 0.001) (see Fig. 6).

a Box plots offer a visual method for examining the distribution of social support changes across different groups. Each plot displays the median, quartiles, along with the maximum and minimum values at each time point. b The mean change in the social support over time is presented along with standard error bars. P values are indicated by stars, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The effects on improvement of quality of life (secondary outcomes)

Quality of Life (QoL)

Significant time, group, and time × group interaction effects were found for QoL. Both groups had significant improvements in the QoL scores over time, with the ITT group showing greater improvements than the control group from T1 to T2 (β = 15.384, 95% CI, 13.028–17.740, P < 0.001) (see Fig. 7).

a Box plots offer a visual method for examining the distribution of quality-of-life changes across different groups. Each plot displays the median, quartiles, along with the maximum and minimum values at each time point. b The mean change in the quality of life over time is presented along with standard error bars. P values are indicated by stars, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Harms

Over time, most participants experienced improvements in frailty across physical, psychological, and social aspects after using the mini-program. Only one participant (1/115, 0.9%) transitioned from a low to a moderate level in physical symptoms, and only two participants (2/115, 1.7%) moved from a low to a moderate level in psychological symptoms. Only one participant’s (1/115, 0.9%) quality of life declined compared to the baseline. All functions were made available to participants after completion of the project.

Discussion

The study confirmed the presence of premature frailty among YBCSs, highlighting a critical gender-specific health issue. Within the “AI-TA” system, the frailty status of each YBCS is assessed and stored as an individual profile. Fatigue emerged as the most frequent criterion of physical frailty, with an alarming 87.0% prevalence among YBCSs7, significantly exceeding that 33.9% observed in healthy women over 4535. YBCSs also reported distressing symptoms similar to those experienced by older BCSs36,37. In addition, the average SSRSs scores among YBCSs were lower than the norms of the Chinese general population (37.87 ± 7.76 versus 44.38 ± 8.38, P < 0.01)38. These findings highlight their premature frailty, a specific challenge faced by YBCSs. Since breast cancer is a major health issue threatening young women’s health and lives, addressing premature frailty is essential to enhance health outcomes for female YBCSs, and promote their well-being and equality.

Most importantly, the study highlighted that “AI-TA” serves as an effective digital tool in reducing premature frailty and consequently enhancing the quality of life from baseline to post 4 weeks and post 12 weeks. Although the intervention group displayed more favorable changes in certain outcomes, both groups exhibited positive shifts in premature frailty status. The findings confirm that digital information support could reduce multiple physical symptoms, not only pain, nausea, but also frailty side effects including fatigue, anxiety, and depression among BCSs39,40,41. Literature consistently underscores the necessity and feasibility of digital health for YBCSs, offering easy access and reduced stress, which is particularly valuable for those facing stigma, isolation, and other underserved conditions, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic42,43. Therefore, simple digital information support could effectively help manage premature frailty among young survivors from diverse backgrounds, particularly Chinese women who prioritize family care over their own health.

Though the group x time interaction for physical frailty was not statistically significant, this study revealed that the intervention group had a larger decrease in fatigue, physical, and psychological symptoms from baseline to 4 weeks and 12 weeks; Also, participants in the intervention group had a significant increase in physical activities and social support scores at T2. Furthermore, the intervention group had a greater increase in quality of life from baseline to T1 and T2.

These findings suggest several benefits arising from the combined design of AI and humanistic approaches. First, both an intelligent recommendation system and individual follow-up provided precise and personalized tailoring for women. YBCSs exhibit varying degrees of premature frailty due to individual treatment impacts during different stages of survivorship41. AI could automatically deliver the most relevant information with machine-readable labels based on self-reported frailty from YBCSs, focusing on gender-specific concerns like fertility, body image, and returning to work44. Furthermore, health workers could offer personalized self-care advice based on survivors’ reports and online interviews. Combining quantitative data with qualitative insights from personal experience can be particularly effective in understanding gender-specific needs of YBCSs31,45, offering targeted support that address women’s specific needs.

Second, an online social-ecologic environment with humanistic characteristics was reshaped by the “G2G” principle33. A gender focus consideration on special life course emphasizes a holistic approach to better understand the context of health and relationships46,47. Hence, the social-ecologic environment, especially the typical family interaction is informed by a feminist conceptualization45. Information modules and peer forums encompass topics related to their gender, age, and culture, such as body image, sexuality, fertility, returning to work, adjustment of parenthood, traditional exercise (e.g., Taiji, Baduanjin), and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)45. Considering that women are more inclined to build communities and are more willing to communicate and share, peer forum provided a preferred platform for young survivors to discuss gender and age considerations, validate their experiences, empower them through shared narratives, and foster family resilience and social adaptation48,49.

Narrative stories were incorporated to foster emotional resilience, and various social resources were provided to develop social networks. The program interface applies emotional design principles, using visual elements such as color, font, layout, and overall esthetics to evoke positive emotional responses. It also integrates persuasive design strategies to promote engagement and interaction, addressing the cognitive frailty of YBCSs and enhancing overall usability50,51,52. Therefore, “AI-TA” serves as a partner to YBCSs, facilitating effective social interaction to promptly capture their thoughts, feelings, and actions, thus addressing their most critical needs in a timely manner44. Overall, “AI-TA” integrates AI and humanistic elements to monitor and address premature frailty issues in women’s health with a G2G perspective. It underscores a holistic approach to health, blending technology with empathetic care to ensure that users receive not only practical interventions but also emotional and psychological support. This seamless integration of AI with person-centered care facilitates personalized, meaningful engagement for young women navigating survivorship challenges.

The findings that the effects on the scores of physical activities and social support were not statistically significant at post 4 weeks could be attributed to several factors. PA and social support are associated with lifestyle, which may not be easily modified within a short intervention period. Premature frailty and other related treatment side effects are obstacles to an active lifestyle, especially for increased PA. Lifestyle changes evolve gradually, influenced by factors like family dynamics and the broader eco-environment53,54. In our study, focusing on YBCSs from China, with an average age of around 40 years, further nuances are evident. Previous research indicates that younger BCSs, burdened with work and household responsibilities and potentially lacking in health knowledge and motivation compared to older counterparts, may struggle to adopt healthier lifestyles55. From the perspective of TCM, the concept of wellness (Yang sheng, 养生) emphasizes appropriateness and balance. For instance, walking emerges as the most prevalent form of physical activity among YBCSs, while leisure activities like Mahjong may contribute to lower physical activity levels56. High-intensity physical activities such as running or strength exercises, along with the associated financial costs, might be deemed inappropriate and unnecessary for cancer survivors within this cultural context. Furthermore, cultural norms in China, such as minimizing disturbance to others including family members, friends, and healthcare works, could pose barriers to obtaining social support and maintaining psychological well-being for Chinese YBCSs, particularly those grappling with high self-stigma and low emotional expression57,58. These cultural intricacies underscore the importance of tailoring interventions to the specific needs and contexts of the women under study.

In addition, the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF), a self-report measure used in our study, may underestimate physical activity levels among BCSs. Research indicates that the MET score derived from IPAQ-SF tends to be lower than the data collected via methods such as accelerometer monitoring and 24-h activity recording over seven consecutive days, especially concerning moderate physical activity and brisk walking59. Therefore, employing wearable sensors or smartphone apps is recommended to gather reliable and valuable data, given that moderate PA is suitable for BCSs60. While digital support can offer anonymity for YBCSs with cancer stigma37, it may also result in reduced interaction with others and increased detachment from the physical world. However, previous studies reported that, compared to elder survivors, YBCSs maintain hope in returning to their pre-cancer normal life, and they may be discouraged by reminders of their diseases33. Consequently, some participants may not initially engage actively with the intervention. Nonetheless, the intervention group benefited significantly from increased interaction and support through digital channels, including peers, family, and healthcare professionals. Therefore, as participants become more accustomed to and derive greater benefits from digital support, the intervention may yield delayed effects in terms of social support and a sense of belonging61.

The primary shortcoming of this study is the absence of tools like accelerometers and hand dynamometers, as suggested by the Fried frailty criteria62, limits the collection of objective data on physical activity and grip strength. In addition, participants’ recruitment from Shanghai, China, may introduce selection biases, limiting generalizability. The lack of long-term follow-up also prevents assessment of sustained effects. Finally, the inclusion of participants at various stages of survivorship may have impacted the intervention’s efficacy. Future research could explore the interaction between gender, age, self-management ability, socioeconomic status, and treatment stage to enhance the equity and efficacy of “AI-TA”.

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of a three-month digital-humanistic intervention for YBCSs, which improved both frailty and quality of life. with high adherence (96.77%). The intervention aligns with Sustainable Development Goals, promoting health and gender equality through digital health30,31 These findings suggest it as a scalable model with potential to address broader women’s health issues and advance global healthcare equity.

Methods

Recruitment and enrollment

This RCT was conducted at hospitals affiliated with a single university, utilizing “AI-TA”, a digital mini-program designed for YBCSs. Building on the original study on psychological and related symptoms63, a more comprehensive exploration of premature frailty was conducted. In this study, two parts of “AI-TA” were included. Firstly, a personal profile with medical records and self-assessment questionnaires to monitor the premature frailty of participants were created, the contents of premature frailty assessment is based on Gobbens’ integral concept model of frailty (physical, psychological, and social frailty) (see Fig. 8)64. The second part is the individual and interactive support according to assessment is provided to reduce the frailty and enhance the quality of life for YBCSs.

The “AI-TA” WeChat Mini Program integrates AI technology with humanistic care, addressing gender- and generation-sensitive (G2G) frailty among YBCSs. It offers digital and humanistic support through a combination of digital tools and personal interactions. On one hand, the platform provides YBCSs with health information, spiritual guidance, and social support modules, while its recommendation system analyzes user behavior and questionnaire data to deliver personalized content. It also tracks user interactions to monitor progress and update content. On the other hand, the program fosters a sense of community through a peer-to-peer forum and fortnightly follow-ups. The forum serves as a private, safe space for YBCSs to share experiences, seek emotional support, and access expert advice, with curated weekly discussions enhancing engagement. Meanwhile, the fortnightly follow-ups offer personalized, compassionate care, co-creating individualized health plans based on survivor feedback. This innovative program marks a significant advancement in digital healthcare and gender equity, tailored specifically to the needs of YBCSs.

As part of a larger study examining the effectiveness of digital intervention on quality of life for YBCSs, the original study was registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry on April 17, 2022 (ChiCTR2200058823). The study adhered to CONSORT guidelines throughout its design and execution. This study was approved by the ethical committee of Public Health and Nursing Research, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTUPN-201803) prior to any participant engagement.

Participants were recruited by two trained clinical nurse specialists according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were: (a) Chinese females; (b) aged 18–45 years old; (c) diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer; (d) able to access the internet using computer or mobile devices; (e) able to read and write in Chinese (traditional or simplified); and (f) provided informed consent. Participants were excluded if they: (a) had severe physical or psychological barriers that significantly impair daily functioning or require intensive medical care and supervision; (b) had recurrent or metastatic breast cancer; and (c) concurrent involvement in other studies.

Once potential participants scanned a QR code provided by the recruiters, they were directed to the “AI-TA” WeChat Mini Program, where they reviewed and provided electronic informed consent. After consent, participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group in a 1:1 ratio using Python’s randomization function. Blinding of the research assistants and participants was not feasible due to the nature of the intervention. Participants completed initial questionnaires, with follow-up surveys at 4 and 12 weeks. Both groups used the WeChat Mini Program for 12 weeks. Data collection and analysis were carried out by research assistants and statistical experts, with accuracy ensured through double-checking.

The construction of “AI-TA” WeChat Mini Program

The “AI-TA” WeChat Mini Program is designed around a “person-centered” approach65, emphasizing digital services with a focus on humanistic care. The program addresses the unique needs of these individuals by focusing on humanistic care, gender, and generation-specific issues45,66, as well as helping them manage the challenges of survivorship and reduce premature frailty. The program leverages digital technology to create a personalized and holistic well-being experience for YBCSs.

Our research team included a Principal Investigator (PI), nurse researchers, breast cancer clinical experts, graduate students, and senior engineers. During the early preparation phase, multiple investigations were conducted to refine the contents and forms of design and intervention strategy, ensuring they were tailored to young women with breast cancer. From content perspectives, we conducted several qualitative studies to explore the socio-ecological environmental characteristics of YBCSs, and further analyzed their role functions as younger generations and women in the family33,45,67. The findings highlight that the unique culture of Chinese society significantly influences the socio-ecological environment of YBCSs. For instance, YBCSs often experience the stresses of fulfilling multiple roles, including daughter, mother, wife, and employee. Many young women struggle to constantly balance family responsibilities and work or study, navigating challenges in career development, child and elder care, fertility, and marriage. A cancer diagnosis can leave them feeling powerless in managing these various roles. The impact of family relationships on Chinese women’s breast cancer survivorship were explored, leading to a better understanding of gender and intergenerational differences with Chinese society. Besides, we used multiple measurement instruments to construct user profiles of YBCSs which includes their natural attributes, social characteristics, and online behaviors in order to better understand their comprehensive needs and influencing factors66. These insights provide a foundation for developing tailored support systems that not only address breast cancer-related challenges but also alleviate the burdens imposed by socially expected roles, offering more holistic care for young survivors.

From form perspectives, we achieve a comprehensive understanding of YBCSs’ preferences for digital health system interface design through the analysis of mainstream medical apps, stakeholder interviews with YBCSs and healthcare professionals, and usability testing50,51. This multi-faceted approach allows us to identify key trends, user needs, and pain points, ultimately guiding the development of more young-friendly digital health interfaces. For example, the program incorporates simple, esthetically pleasing icons and a color scheme that conveys safety and trust. Text is minimized, and images are used to improve readability and engagement. Additionally, content is presented in short, digestible formats (e.g., 10-second videos) to avoid overwhelming users with excessive information. Followed by these fitting design considerations, the “AI-TA” WeChat Mini Program can be made more understandable, engaging, and ultimately more effective in supporting the health and well-being of YBCSs.

Building on previous researches, our team collaborated with a technology company to develop a digital platform prototype. After thorough discussions, the prototype underwent reviews and modifications until a consensus was reached. The “AI-TA” platform utilized a decoupled frontend and backend architecture. The front end is responsible for displaying personalized health information, while the backend processes user data and employs AI-driven algorithms to recommend relevant content. The AI-driven algorithms are built on a hybrid recommendation system that integrates keyword-based analysis and collaborative filtering. The keyword-based analysis identifies key areas of concern from user-provided survey responses, focusing on low-scoring aspects such as psychological stress, and matches them with curated resources like articles or videos that address these specific needs. At the same time, collaborative filtering analyzes the preferences and behaviors of users with similar profiles, recommending health information that has been positively received by similar users. This combination allows the system to provide highly personalized suggestions while enhancing the diversity and relevance of recommendations. By continuously learning from user interactions and feedback, the system ensures that the recommendations remain accurate and adaptive to individual needs over time. Built on the Django web framework, the backend handles user data management, dynamic content delivery, and integration with machine learning algorithms. Django’s Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) streamlines database interactions, allowing developers to define and manage database models directly in a high-level programming language. This approach enhances development efficiency, minimize database errors, and enables seamless integration of diverse data for a comprehensive view of YBCSs’ care. Django ORM’s robust querying capabilities enable timely identification of YBCSs’ specific needs, supporting dynamic and personalized care delivery to address their unique health challenges. Iterative testing and user feedback led to refinements in the interface and functionality, resulting in a tailored, user-friendly experience for YBCSs, as reported in our pilot study61.

Intervention

The “AI-TA” WeChat Mini Program featured several modules specially designed to address the needs of YBCSs in managing premature frailty including physical, psychological, and social domains, and improving their quality of life during survivorship (see Figs. 8 and 9).

User interface is divided into six main sections: social support, health information, spiritual home, forum, recommended information, and consultation appointments. Users can browse and save resources and information in the first four sections. In the forum, they can interact with others by posting, liking, and commenting. Additionally, users can click on the consultation option on the homepage to schedule appointments and communicate with healthcare professionals online.

This platform showed digital support for participants. First, it provided access to reliable resources covering health information, spiritual home, and social support modules, such as advanced treatments, returning to work, adjustment of parenthood, survivor’s self-narrative letter, and inspirational stories of young women, etc. in text, image, or animation formats. The selection of these young-female-focused contents was based on the demand characteristics of this population in preliminary studies and was reviewed and approved by clinical experts. In addition, researchers would invite breast clinical experts to hold lectures from time to time, focusing on common problems in cancer treatments involving diet guidance, functional exercise, tube maintenance, and so on. Q&A sessions were incorporated, with recorded videos made available for review in modules.

Second, the recommended information was central to our digital support, driven by an automatic intelligent system that employed text extraction techniques and behavioral data analysis to deliver personalized content. This innovative approach significantly enhanced user engagement and retention by tailoring information to individual preferences and interests. On one hand, the system analyzed questionnaire results to identify priority issues and push relevant content. For instance, if a user reports high levels of stress and difficulty managing emotions, keywords like “stress management,” “mindfulness,” “emotional well-being,” and “relaxation” would be employed to recommend pertinent resources such as guided meditation videos or articles on coping strategies. On the other hand, the system performed data tracking and management, synchronously storing user interactions in the server backend of platform such as logins, comments, likes, history, and duration. These enabled algorithms to calculate and monitor assessment progress regularly. By tracking survivors’ symptoms, researchers could update and customize content based on users’ browsing behaviors, enhancing the relevance and effectiveness of the information provided. Plus, adhering to data regulations, the system employed encryption measures to guarantee the highest levels of privacy and security for user data. This dynamic interactive approach enhanced the user experience through real-time feedback and collaborative dialog, participants can feel more engaged and supported for their journey toward recovery.

Furthermore, the program also incorporated humanistic support through peer-to-peer forums and fortnightly online follow-ups. The forum served as a safe, web-based private space where YBCSs could share their experiences, offer emotional support to one another, resonate with each other, and seek guidance when needed. It fostered a sense of community, allowing users to ask questions, engage in real-time discussions, and access expert advice. Additionally, the forum proposed weekly discussion topics, curated by researchers and specialists, encouraging meaningful conversations and empowering YBCSs to actively participate in their own care and psychological well-being management. These could significantly facilitate social support networks or groups, connecting individuals with similar interests or experiences to enhance communication and collaboration.

The fortnightly online follow-up, conducted through private messages or calls fostered a collaborative partnership with YBCSs, emphasizing person-centered care. This approach allowed for individualized attention, as healthcare professionals engaged with survivors in a compassionate, non-judgmental manner, ensuring that each interaction was not just transactional but deeply relational. In the initial conversations, researchers prioritized listening to survivors’ narratives about their daily life events and customs (e.g., diet, exercise, stress, hobbies, and relationships). This approach fostered trust and open communication. The next phase involved anticipating and co-creating a personalized health plan based on the survivors’ feedback, integrating both quantitative assessments and qualitative interviews to clarify their true goals, available resources, and needs. Key points from each conversation would become focal topics for subsequent discussions such as what participants shared, how they felt, their aspirations, and what they aimed to achieve. Throughout the three-month intervention, participants were encouraged to have consultation appointments with researchers at any time, ensuring ongoing support and guidance. Each follow-up was recorded and uploaded to the platform, creating a comprehensive record that enhanced continuity of care and reinforced the essential human connection for effective support. These two modules provided not only medical guidance but also emotional and psychological reassurance, reflecting a profound commitment to holistic, humanistic care.

Control

Control group participants were provided with access to general modules (health information, spiritual home, and social support) about “AI-TA”, excluding the forum, online follow-up, and recommended information. This meant that they were unable to participate in forum discussions or receive recommendations provided by our automatic intelligence system based on each assessment. Additionally, YBCSs in the control group did not have the opportunity for follow-up conversations.

Sociodemographic

A comprehensive set of questions was utilized to assess the sociodemographic and health profiles of YBCSs. These inquiries covered various aspects including age, height, weight, habitation, education, marital status, employment, financial income, family composition, cancer stage (Stage I to Stage III), type of cancer, duration of the cancer diagnosis, and the medical treatments received.

Primary outcomes: physical frailty, psychological frailty, social frailty

BFI is a reliable instrument for quickly gauging the fatigue levels of cancer patients68. This assessment scale includes nine items to evaluate the degree of current fatigue and the extent to which fatigue has interfered with different aspects of life in the past 24 h. The overall score is derived from the mean of all nine items. According to the total score, fatigue is classified as mild (1–3 points), moderate (4–6 points), and severe (7–10 points). The scale’s Cronbach’s α was 0.868 in this study.

IPAQ-SF is used to assess an individual’s physical activity level69. This tool examines the frequency and duration of vigorous, moderate, and walking activities, as well as the time spent sitting, over the course of a week. The overall score is calculated by summing the measures of light, moderate, and vigorous activities, and the results are expressed in MET units. Physical activity levels are classified into three categories: low (<600 MET-min/week), moderate (600–1500 MET-min/week), and high (>1500 MET-min/week). The scale’s Cronbach’s α was 0.839 in this study.

PHYS is assessed using The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Short Form (MSAS-SF)70. It evaluates twelve common physical symptoms, including lack of energy, pain, reduced appetite, drowsiness, constipation, dry mouth, nausea, vomiting, altered taste perception, weight loss, bloating, and dizziness. Each symptom’s distress level is rated on a 5-point Likert scale: 0 for “not at all,” 1 for “a little bit,” 2 for “somewhat,” 3 for “quite a bit,” and 4 for “very much.” The Cronbach’s α of the PHYS was 0.82.

PSYCH is also assessed by MSAS-SF, which covers six prevalent psychological symptoms: worrying, sadness, nervousness, sleep difficulties, irritability, and concentration issues70. Similar to PHYS, the distress level of each psychological symptom is rated on the same 5-point Likert scale. The Cronbach’s α of the PSYCH was 0.78.

SSRS is a 10-item questionnaire developed to measure social support, encompassing subjective support, objective support, and the utilization of social support71. A higher score indicates greater social support. A total score of ≤22 is considered indicative of poor social support, a score between 23 and 44 signifies moderate social support, and a score between 45 and 66 indicates adequate social support. The Cronbach’s α of each entry is 0.89–0.94.

Secondary outcomes: quality of life

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) was employed to assess the quality of life of breast cancer patients72. This tool evaluates five dimensions: physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being, and additional concerns related to breast cancer. The assessment comprises 36 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. Higher scores on this scale indicate a better quality of life. The Cronbach’s α of each dimension is 0.61–0.84.

Sample size

The study employed G*Power 3.1 software to determine the required sample size. Based on previous research and our prior pilot investigations, using the statistical effect size estimates for fatigue (d = 0.66)73, physical activity (d = 0.55)74, physical symptoms (d = 0.67)61, psychological symptoms (d = 0.77)39, and social support (d = 0.87)61, a sample of 86 participants was needed to detect significant between-group differences and demonstrate a mean effect size (d = 0.70) in the primary outcomes following the intervention. This calculation was based on an alpha level of .05 for a two-sided test, 80% statistical power, a 1:1 allocation ratio, and accounting for a 20% attrition rate. To ensure robustness, the target enrollment was increased to 124 participants.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted utilizing SPSS Statistics (version 26.0; IBM Corp). The study groups were delineated using descriptive and comparative statistical methods (e.g., percentages, means, and standard deviations). Demographic disparities between the intervention and control groups were evaluated using two-sample t tests, chi-square tests, or Fisher’s exact tests, depending on the context. Paired t tests were employed to scrutinize the dependent variables, while the two-sample t tests were applied to identify variations between the intervention and control groups at various time points. Except for PHYS (F = 5.54, P < 0.05) and SSRS (F = 6.04, P < 0.05), there were no significant differences between the two groups at T0. The changes in key variables over time were verified using generalized estimating equations. During the data analysis, PHYS and SSRS, which exhibited differences in the homogeneity tests, were incorporated as covariates and adjusted for in subsequent analyses. The treatment effects were measured by calculating the mean differences from T1 to T2. The shifts in the average scores of individual outcome measures from T0 to T1 and T2 were determined for both the intervention and control groups.

In this study, ITT analyses were performed, encompassing participants who completed the initial assessments, with missing data imputed using the Expectation Maximization (EM) Algorithm. The primary endpoints for evaluating the efficacy of “AI-TA” were BFI, IPAQ-SF, MSAS-SF and SSRS to assess premature frailty. The secondary endpoint was FACT-B, measures of quality of life.

Data availability

The study report, study protocol, and datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Analysis to process and analyze data was generated with SPSS 26.0.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Yan, C. H. et al. Associations between frailty and cancer-specific mortality among older women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 189, 769–779 (2021).

Wennberg, A. M. et al. Frailty among breast cancer survivors: evidence from Swedish Population Data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 192, 1128–1136 (2023).

Cespedes Feliciano, E. M. et al. Association of prediagnostic frailty, change in frailty status, and mortality after cancer diagnosis in the women’s health initiative. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2016747 (2020).

Griffith, L. E. et al. Frailty differences across population characteristics associated with health inequality: a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). BMJ Open 11, e047945 (2021).

Ness, K. K. et al. Physiologic frailty as a sign of accelerated aging among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St Jude Lifetime cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 4496–4503 (2013).

Coffman, E. M. et al. Frailty and comorbidities among young adult cancer survivors enrolled in an mHealth physical activity intervention trial. J. Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01448-4 (2023).

Gilmore, N. et al. The longitudinal relationship between immune cell profiles and frailty in patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. 23, 19 (2021).

Ahles, T. A. et al. Relationship between cognitive functioning and frailty in older breast cancer survivors. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 13, 27–32 (2022).

Ballinger, T. J., Thompson, W. R. & Guise, T. A. The bone-muscle connection in breast cancer: implications and therapeutic strategies to preserve musculoskeletal health. Breast Cancer Res. 24, 84 (2022).

Goel, N. et al. Neighborhood disadvantage and breast cancer-specific survival. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e238908 (2023).

Williams, G. R. et al. Frailty and health-related quality of life in older women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 27, 2693–2698 (2019).

He, C. Y. et al. Characteristics and influencing factors of social isolation in patients with breast cancer: a latent profile analysis. Support Care Cancer 31, 363 (2023).

International Labour Organization. ILO Modelled Estimates (ILOEST database). http://ilostat.ilo.org/methods/concepts-and-definitions/ilo-modelled-estimates/ (2024).

Kim, A. T., Erickson, M., Zhang, Y. & Kim, C. Who is the “she” in the pandemic “she-cession”? Variation in COVID-19 labor market outcomes by gender and family status. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 41, 1325–1358 (2022).

Li, C. X. et al. Listening to voices from multiple sources: a qualitative text analysis of the emotional experiences of women living with breast cancer in China. Front. Public Health 3, 11:1114139 (2023).

Guida, J. L. et al. Associations of seven measures of biological age acceleration with frailty and all-cause mortality among adult survivors of childhood cancer in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Nat. Cancer 5, 731–741 (2024).

Hoogendijk, E. O. et al. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet 394, 1365–1375 (2019).

Fielder, E. et al. Sublethal whole-body irradiation causes progressive premature frailty in mice. Mech. Ageing Dev. 180, 63–69 (2019).

Pranikoff, S. et al. Frail young adult cancer survivors experience poor health-related quality of life. Cancer 128, 2375–2383 (2022).

Tsai, H. H. et al. The impact of frailty on breast cancer outcomes: evidence from analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2005-2018. Am. J. Cancer Res. 12, 5589–5598 (2022).

Bradbury, K. et al. Developing a digital intervention for cancer survivors: an evidence-, theory- and person-based approach. NPJ Digit. Med. 2, 85 (2019).

Corbett, T. et al. Understanding acceptability of and engagement with Web-based interventions aiming to improve quality of life in cancer survivors: A synthesis of current research. Psychooncology 27, 22–33 (2018).

Shahrokni, A. et al. Electronic rapid fitness assessment: a novel tool for preoperative evaluation of the geriatric oncology patient. J. Natl Compr. Cancer Netw. 15, 172–179 (2017).

Cuadra, A. et al. The association between perioperative frailty and ability to complete a web-based geriatric assessment among older adults with cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 49, 662–666 (2023).

Mir, N., Curry, G., Lee, N. K., Szmulewitz, R. Z. & Huisingh-Scheetz, M. A usability and participatory design study for GeRI, an open-source, remote cancer treatment toxicity and frailty monitoring platform for older adults. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 15, 101595 (2024).

Papachristou, N. et al. A smart digital health platform to enable monitoring of quality of life and frailty in older patients with cancer: a mixed-methods, feasibility study protocol. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 39, 151437 (2023).

Howell, D. et al. A web-based cancer self-management program (I-can manage) targeting treatment toxicities and health behaviors: human-centered co-design approach and cognitive think-aloud usability testing. JMIR Cancer 9, e44914 (2023).

Seroussi, B. & Zablit, I. Implementation of digital health ethics: a first step with the adoption of 16 European ethical principles for digital health. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 310, 1588–1592 (2024).

Figueroa, C. A., Luo, T., Aguilera, A. & Lyles, C. R. The need for feminist intersectionality in digital health. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e526–e533 (2021).

Prescott, A. In Mixed Methods and the Digital Humanities (eds Schneider, B. et al.) 27–42 (Bielefeld University Press, 2023).

Porter, T. M. Digital humanism. Hist. Psychol. 21, 369–373 (2018).

Hu, Y. et al. Socio-ecological environmental characteristics of young Chinese breast cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 48, 481–490 (2021).

Li, J. et al. A nation-wide multicenter 10-year (1999-2008) retrospective clinical epidemiological study of female breast cancer in China. BMC Cancer 11, 364 (2011).

Jing, M. J., Wang, J. J., Lin, W. Q., Lei, Y. X. & Wang, P. X. A community-based cross-sectional study of fatigue in middle-aged and elderly women. J. Psychosom. Res. 79, 288–294 (2015).

Park, J. H., Jung, Y. S., Kim, J. Y. & Bae, S. H. Determinants of quality of life in women immediately following the completion of primary treatment of breast cancer: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 16, e0258447 (2021).

Im, E. O. et al. A randomized controlled trial testing a virtual program for Asian American women breast cancer survivors. Nat. Commun. 14, 6475 (2023).

Zhang, M. Y. In Psychiatric Rating Scale Manual, 2nd edn. 35–42 (Hunan Science and Technology Press, 1993).

Im, E. O., Kim, S., Yang, Y. L. & Chee, W. The efficacy of a technology-based information and coaching/support program on pain and symptoms in Asian American survivors of breast cancer. Cancer 126, 670–680 (2020).

Masiero, M. et al. Support for Chronic pain management for breast cancer survivors through novel digital health ecosystems: Pilot Usability Study of the PainRELife Mobile App. JMIR Form. Res. 8, e51021 (2024).

Fjell, M., Langius-Eklöf, A., Nilsson, M., Wengström, Y. & Sundberg, K. Reduced symptom burden with the support of an interactive app during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer—a randomized controlled trial. Breast 51, 85–93 (2020).

Zhou, W., Cho, Y., Shang, S. & Jiang, Y. Use of digital health technology among older adults with cancer in the United States: findings from a National Longitudinal Cohort Study (2015-2021). J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e46721 (2023).

Pekmezi, D. W. et al. Feasibility of using computer-tailored and internet-based interventions to promote physical activity in underserved populations. Telemed. J. E. Health 16, 498–503 (2010).

Bendell, R., Williams, J., Fiore, S. M. & Jentsch, F. Individual and team profiling to support theory of mind in artificial social intelligence. Sci. Rep. 14, 12635 (2024).

Xu, J., Wang, X., Chen, M., Shi, Y. & Hu, Y. Family interaction among young Chinese breast cancer survivors. BMC Fam. Pract. 22, 122 (2021).

Cáceres Rivera, D. I. et al. Parameters for delivering ethnically and gender-sensitive primary care in cardiovascular health through telehealth. Systematic review. Public Health 235, 134–151 (2024).

Miers, M. Developing an understanding of gender sensitive care: exploring concepts and knowledge. J. Adv. Nurs. 40, 69–77 (2002).

Santhosh, L. et al. Strategies for forming effective women’s groups. Clin. Teach. 18, 126–130 (2021).

Lazard, A. J. et al. Using social media for peer-to-peer cancer support: interviews with young adults with cancer. JMIR Cancer 7, e28234 (2021).

Xie, Y. D. et al. A comparative study of medical APP interface design based on emotional design principles. J. Med. Inform. 35, 27–30 (2022).

Jiang, L. L. et al. Cognitive frailty for young breast cancer survivors after chemotherapy: Implication for the design of health education materials. Cancer Care Res. Online.

Fogg, B. J. A behavior model for persuasive design[C]. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology. 1-7 (ACM, New York, NY, USA, 2009).

Chatterjee, A., Prinz, A., Gerdes, M. & Martinez, S. Digital interventions on healthy lifestyle management: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e26931 (2021).

St George, S. M. et al. Development of a multigenerational digital lifestyle intervention for women cancer survivors and their families. Psychooncology 29, 182–194 (2020).

Hsia, H. H., Tien, Y., Lin, Y. C. & Huang, H. P. Factors influencing health promotion lifestyle in female breast cancer survivors: the role of health behavior self-efficacy and associated factors. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 40, 151622 (2024).

Sheng, J. X. et al. Physical activity and breast cancer prevention among Chinese American women: a qualitative descriptive study. Qual. Health Res. 33, 1218–1231 (2023).

Ching, S. S. Y. & Mok, E. S. B. Adoption of healthy lifestyles among Chinese cancer survivors during the first five years after completion of treatment. Ethn. Health 27, 137–156 (2022).

Tsai, W., Wu, I. H. C. & Lu, Q. Acculturation and quality of life among Chinese American breast cancer survivors: the mediating role of self-stigma, ambivalence over emotion expression, and intrusive thoughts. Psychooncology 28, 1063–1070 (2019).

Qu, N. N. & Li, K. J. Study on the reliability and validity of international physical activity questionnaire (Chinese Vision, IPAQ). Chin. J. Epidemiol. 25, 265–268 (2004).

Campbell, K. L. et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 51, 2375–2390 (2019).

Jiang, L. L. et al. Construction of an intelligent interactive nursing information support system and its application in young breast cancer survivors. Chin. J. Nurs. 58, 654–661 (2023).

Goede, V. Frailty and cancer: current perspectives on assessment and monitoring. Clin. Interv. Aging 18, 505–521 (2023).

Jiang, L. L. et al. Effects of the “AI-TA” mobile app with intelligent design on psychological and related symptoms of young survivors of breast cancer: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 12, e50783 (2024).

Gobbens, R. J., Luijkx, K. G., Wijnen-Sponselee, M. T. & Schols, J. M. Towards an integral conceptual model of frailty. J. Nutr. Health Aging 14, 175–181 (2010).

Britten, N. et al. Learning from Gothenburg model of person centred healthcare. BMJ 370, m2738 (2020).

Jiang, L. L., Wang, X. Y. & Hu, Y. Research of comprehensive needs of young breast cancer survivors based on user portrait. Nurs. J. Chin. People Liberation Army 39, 26–30 (2022).

Hu, Y., Cheng, C., Chee, W. & Im, E. O. Issues in Internet-based support for Chinese-American breast cancer survivors. Inform. Health Soc. Care. 45, 204–216 (2020).

Mendoza, T. R. et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: use of the Brief Fatigue Inventory. Cancer 85, 1186–1196 (1999).

Craig, C. L. et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35, 1381–1395 (2003).

Fu, L. et al. Validation of the simplified Chinese version of the memorial symptom assessment scale-short form among cancer patients. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 56, 113–1214 (2018).

Xiao, S. Y. The theoretical underpinnings and research applications of the social support rating scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 4, 98–100 (1994).

Wan, C. H. et al. Introduction on measurement scale of quality of life for patients with breast cancer: Chinese version of FACT-B. China Cancer 11, 318–320 (2002).

Park, S. et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psychological distress, fear of cancer recurrence, fatigue, spiritual well-being, and quality of life in patients with breast cancer-a randomized controlled trial. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 60, 381–389 (2020).

Lynch, B. M. et al. A randomized controlled trial of a wearable technology-based intervention for increasing moderate to vigorous physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior in breast cancer survivors: the ACTIVATE Trial. Cancer 125, 2846–2855 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71804112), and Humanities Youth Talent Cultivation Project, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (2023QN039), and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine: Nursing Development Program (grant number: SJTUHLXK2024). All authors appreciate the efforts made by dozens of research assistants during the process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. and E.O.I. designed the study. Y.H., L.L.J., and J.H.X. conducted the study. J.W. provided statistical advice on data analysis. F.T.Z. developed “AI-TA” WeChat Mini Program. Y.H., R.Y., L.L.J., J.W., X.Y.W., Y.Y.L., A.Z.W., and E.O.I. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Y., Wiley, J., Jiang, L. et al. Digital humanistic program to manage premature frailty in young breast cancer survivors with gender perspective. npj Digit. Med. 8, 35 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01439-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01439-y