Abstract

Deep learning techniques have significantly enhanced the convenience and precision of ultrasound image diagnosis, particularly in the crucial step of lesion segmentation. However, recent studies reveal that both train-from-scratch models and pre-trained models often exhibit performance disparities across sex and age attributes, leading to biased diagnoses for different subgroups. In this paper, we propose APPLE, a novel approach designed to mitigate unfairness without altering the parameters of the base model. APPLE achieves this by learning fair perturbations in the latent space through a generative adversarial network. Extensive experiments on both a publicly available dataset and an in-house ultrasound image dataset demonstrate that our method improves segmentation and diagnostic fairness across all sensitive attributes and various backbone architectures compared to the base models. Through this study, we aim to highlight the critical importance of fairness in medical segmentation and contribute to the development of a more equitable healthcare system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, deep learning (DL)-based algorithms have demonstrated exceptional performance across various medical applications, including classification, segmentation, and detection1. These advancements in digital healthcare technologies hold significant potential for promoting health equity, particularly in low-income countries or resource-limited regions. By leveraging high-quality pre-trained model weights optimized with extensive medical data from diverse organizations and sites, DL-based solutions can provide accessible and efficient diagnostic tools to underserved populations.

Ultrasound imaging is a widely used medical imaging modality that utilizes high-frequency sound waves to generate real-time images of internal organs, tissues, and blood flow2. Its non-invasive nature, portability, and cost-effectiveness make it an especially convenient diagnostic tool, particularly for point-of-care and bedside applications. The general workflow for ultrasound diagnosis is illustrated in Fig. 1. After acquiring ultrasound images, physicians typically identify and annotate the lesion area, calculate radiologic characteristics such as lesion area and length, and then provide a final diagnosis. In this process, DL models play a critical role in automating lesion segmentation. This automation is often achieved through models pre-trained on large-scale ultrasound imaging datasets3.

Although numerous studies have demonstrated that the use of pre-trained weights can significantly enhance the utility of deep learning (DL) models for ultrasound image diagnosis, recent research has revealed that these pre-trained models often inherit biases from their training datasets, leading to unfair performance in downstream tasks4. This presents significant challenges to achieving health equity. For instance, Jin et al.5 observed that their pre-trained MedicalMAE model exhibited substantial utility disparities between male and female groups in pleural effusion diagnosis using chest X-ray images.

This is a critical issue that demands attention, as model unfairness undermines patients’ rights to equitable treatment, diminishes the reliability and trustworthiness of DL models, and poses severe risks to privacy preservation and health equity6,7. In essence, algorithmic fairness is the principle that DL models should deliver comparable outcomes across diverse patient demographics, particularly those involving sensitive attributes such as age, sex, and race.

Currently, researchers aim to mitigate unfairness in DL-based healthcare applications through three primary approaches: 1) Pre-processing, which involves modifying the input data distribution using sampling strategies8 or generative adversarial networks (GANs)9; 2) In-processing, which incorporates fairness constraints10 or employs adversarial network architectures11; and 3) Post-processing, which adjusts the output logits for different subgroups10 or prunes model parameters12. However, these methods often require re-training or fine-tuning model weights, which is both resource-intensive and time-consuming—particularly when addressing unfairness in large foundation models.

In this paper, we address the challenge of improving fairness in ultrasound image diagnosis, focusing specifically on lesion segmentation, under a stricter scenario where the pre-trained model weights remain fixed due to limited computational resources. Inspired by ref.13, which generates perturbations using GANs, we propose a novel approach called APPLE. APPLE achieves fairness by manipulating the latent embedding with protected-attribute-aware perturbations. Unlike methods that perturb the input image directly14, perturbing the latent space is more effective, as features in deeper layers carry higher-level semantic information and are more separable.

Specifically, APPLE comprises a generator that perturbs the latent embedding of the fixed segmentation encoder to obscure the sensitive attribute of the input image and a discriminator that attempts to identify the sensitive attribute from the perturbed latent embedding. This adversarial setup ensures that the learned perturbations enhance fairness without modifying the pre-trained model weights.

Results

Unfairness exists in ultrasound image segmentation

Accurate segmentation of lesion regions in ultrasound images is a critical first step in ultrasound image diagnosis, as it forms the foundation for subsequent analysis. A precise lesion mask provides abundant information, including the lesion’s surface area, aspect ratio, and sphericity. Conversely, biased segmentation directly impacts the computation of these variables, potentially leading to inaccuracies in diagnosis.

To evaluate segmentation precision, we utilize the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC)15, a widely used metric that quantifies the overlap between the ground truth mask and the predicted mask. The group-wise DSC results on two ultrasound datasets are shown in Fig. 2. The results reveal a consistent pattern: across all four deep learning models, the DSC scores for the Female group are higher than those for the Male group in both datasets. For the TUSC dataset, the Young group achieves slightly higher DSC scores than the Old group, whereas this trend reverses in the QDUS dataset.

All the results are evaluated on the respective test set. The U-Net and TransUnet are trained on the TUSC / QDUS training set. SAM and MedSAM are used as zero-shot segmentators with the ground truth bounding box as the prompt. a Result on TUSC-Sex; b Result on TUSC-Age; c Result on QDUS-Sex; d Result on QDUS-Age.

Interestingly, U-Net and TransUnet are trained on stratified-sampled training sets, while SAM and MedSAM operate as zero-shot segmentators. While SAM-based models exhibit less bias and significantly higher overall utility compared to train-from-scratch models (e.g., U-Net and TransUnet), the bias direction remains consistent, with DSCFemale > DSCMale and DSCYoung > DSCOld (on TUSC dataset, while DSCYoung < DSCOld on QDUS dataset). This may stem from SAM-based models using the ground truth bounding box of the lesion as a prompt, providing additional information that benefits segmentation.

These results highlight the persistent presence of unfairness in ultrasound image segmentation tasks, emphasizing the need to address this issue to ensure fair and reliable downstream diagnosis.

Downstream diagnosis inherit unfairness from predicted masks

In the general pipeline of ultrasound diagnosis, several radiomics parameters are extracted from both the ultrasound images and their corresponding predicted masks. These parameters are crucial for clinicians in determining whether a lesion is benign or malignant. However, disparities in lesion mask predictions between subgroups can propagate through to the computation of these parameters, leading to biased or unfair diagnoses.

To investigate this issue, we selected three commonly used parameters in ultrasound diagnosis—surface area, energy, and perimeter—and computed the absolute differences between values derived from the ground truth mask and those derived from the predicted mask using PyRadiomics16. The subgroup distributions for these parameters are visualized in the first row of Figs. 3 and 4.

All results are computed on the TUSC dataset. JS denotes Jensen-Shannon divergence and a lower JS means the two distributions are closer to each other. a–c Subgroup disparity of surface area, perimeter, and energy of the original TransUnet; d–f Subgroup disparity of surface area, perimeter, and energy of the TransUnet+APPLE.

As illustrated in the figures, all three parameters show significant disparities between subgroups. Specifically, the absolute differences are consistently higher in the Male group compared to the Female group. Similarly, with respect to age, the Old group exhibits a greater absolute difference than the Young group. These results are consistent with the observed segmentation accuracy patterns, emphasizing that unfairness in the segmentation process can propagate into downstream diagnostic tasks. This further underscores the importance of addressing bias in lesion segmentation to ensure fair and equitable diagnoses.

Unfairness mitigation via APPLE

To address the issues outlined in ultrasound diagnosis, we focus on the lesion segmentation step and propose using adversarial protected-attribute-aware perturbations within the latent embedding space. The results of our approach are presented in Table 1. For each backbone, we inspect APPLE and other two state-of-the-art unfairness mitigation methods including FEBS17 and InD18. The FEBS adds a new loss term to the origin loss function, i.e., DiceCE loss. The InD finetunes the base model using subgroup-only data, resulting in a subgroup-specific model for each group.

Our proposed APPLE framework effectively reduces unfairness while preserving comparable overall segmentation performance across the two datasets, as compared to baseline models and other unfairness mitigation methods. Notably, TransUnet+APPLE achieves both a higher average DSC (\(\overline{\,\text{DSC}}\)) and a lower disparity (DSCΔ) for the sex attribute on the QDUS dataset, underscoring its capability to enhance fairness without compromising segmentation accuracy.

Furthermore, using TransUnet and the TUSC dataset as an example, we present the absolute difference distributions of both the baseline model and our proposed model for the sex and age attributes in Figs. 3 and 4. Compared to the baseline model, the proposed model shows a more similar overall distribution shape, and the JS-divergence19 between subgroups is lower, indicating a greater similarity between the subgroups.

Integrating APPLE with segmentation foundation models

We also apply APPLE to segmentation foundation models, including SAM and MedSAM, to evaluate its potential in addressing fairness in larger, prompt-based models, which have demonstrated strong performance in medical segmentation tasks. The results are shown in Table 2. By integrating APPLE, the fairness of MedSAM improves slightly, while the DSCΔ for SAM increases by ~0.2%, demonstrating the potential for mitigating unfairness in foundation models with a large number of parameters.

Confounder removal in latent space

To verify that unfairness mitigation is achieved through perturbation of the latent space, we use t-SNE20 to visualize the latent feature space of both the baseline model and the perturbed model. Additionally, we employ the Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI)21 and Silhouette Score (SS)22 to assess clustering quality. A lower Davies-Bouldin score and a higher Silhouette Score indicate better clustering quality. Intuitively, the perturbed model should exhibit more challenging clustering due to the attribute-aware perturbations. The results, shown in Fig. 5, demonstrate that compared to the pre-trained model, the mitigation model exhibits higher DBI and lower SS, indicating a decrease in clustering quality.

a t-SNE of the TUSC dataset regarding sex, red: male, green: female; b t-SNE of the TUSC dataset regarding age, red: young, green: old. Compared to the pre-trained model, the mitigation model has a higher Davies-Bouldin index (DBI) and lower silhouette score (SS), denoting a worse clustering quality.

Achieving controllable fairness constraining

In APPLE, a weighted factor, β, is used to adjust the degree of constraint on the target task and fairness. Experiments are conducted on the TUSC dataset focusing on age attribute, where we modified β from 0.01 to 10.0 to see if it can control the constraint on fairness successfully. The result is shown in Fig. 6. With the increase of β, both the \(\overline{\,\text{DSC}}\) and DSCΔ show a descending trend, illustrating a drop in overall utility and an improvement in fairness metrics. This phenomenon is consistent with the original assumption, i.e., the controllable fairness constraint can be achieved by adjusting β.

Discussion

In this paper, we address unfairness mitigation in deep learning-based ultrasound image diagnosis under a more stringent constraint, where the weights of pre-trained models are frozen and cannot be modified. This is achieved by manipulating latent embeddings using protected-attribute-aware perturbations. The following key observations are highlighted for further discussion.

Firstly, unfairness is prevalent across the two ultrasound datasets with respect to both sex and age attributes, regardless of the segmentation backbone (i.e., CNN-based, Transformer-based, or SAM-based models). As shown in Fig. 2, this biased trend persists across each dataset, although different architectures exhibit varying degrees of unfairness. This indicates that unfairness arises from both data and model factors, which aligns with findings in ref.6, disparities in subgroup performances remain, which are even more pronounced compared to the zero-shot SAM and MedSAM models. In terms of overall performance, SAM-based models demonstrate higher zero-shot performance on the TUSC dataset, possibly due to the inclusion of bounding-box prompts. However, SAM’s overall performance drops significantly on the QDUS dataset.

Secondly, unfairness in lesion mask predictions propagates to downstream diagnosis. By comparing the errors in radiomics parameters such as surface area, perimeter, and energy between the predicted and ground truth masks, we observe that the Male group tends to have higher errors compared to the Female group on the TUSC dataset, and the Old group tends to show higher errors than the Young group. These discrepancies in error directly impact the clinicians’ diagnostic process and may lead to unfair treatment.

Thirdly, extensive experiments across two ultrasound image datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method in improving fairness across different backbones and attributes. These improvements are reflected in both numeric fairness metrics (shown in Table 1) and error distribution similarities (depicted in Figs. 3 and 4). Unlike previous fairness mitigation approaches that modify training data through sampling or data synthesis, or alter network architectures with adversarial branches or pruning biased neurons, our method introduces protected-attribute-aware perturbations directly into the latent feature embeddings, preserving both the original network architecture and weights. The strong performance of our method across various experimental settings highlights its generalizability.

Compared to other unfairness mitigation methods, APPLE achieves the best or second-best in each group under most experiment settings. Although InD has the best fairness scores and utilities in TUSC-Sex, we need to emphasize that it requires sensitive attributes in the inference stage, which means additional information requirements compared to APPLE and FEBS, and may bring difficulties in real-world applications. On the other hand, while FEBS demonstrates better utility preservation compared to APPLE, it outperforms APPLE solely in terms of fairness metrics within the TUSC-Sex dataset when utilizing U-Net as the backbone architecture.

Fourthly, given the increasing use of large-scale foundation models for image segmentation, such as SAM and MedSAM, we also integrate our proposed APPLE into these pre-trained models. As shown in Table 2, APPLE effectively improves fairness in these foundation models, which is often challenging, as noted by Jin et al.23, who found that fairness mitigation methods for smaller models might not always be effective for foundation models. In contrast, our approach preserves the pre-trained model weights while applying perturbations to the latent space, thereby leveraging large pre-training datasets more effectively.

Moreover, we observed that the integration of APPLE with the two SAM-family models effectively preserved overall model utility while simultaneously mitigating bias. This finding is particularly significant, as most existing bias mitigation approaches typically compromise model performance to achieve fairness, thereby diminishing the inherent advantages of large-scale models trained on extensive datasets.

Moreover, by visualizing the latent feature space of the pre-trained models, we observe group-wise aggregations based on both sex and age attributes. This supports the hypothesis proposed in ref.24 that the encoding of sensitive attribute information by deep learning models may contribute to unfair outcomes. Upon comparing the latent spaces of the pre-trained model and the mitigation model, we find that group-wise clustering is reduced, leading to improvements in the corresponding fairness metrics. This relationship provides valuable insights for the development of more effective unfairness mitigation algorithms in future studies.

Lastly, while both model utility and fairness are crucial in real-world applications, there are scenarios where the utility is too low for fairness analysis to be meaningful. For example, if the overall DSC is around 40%, the focus on fairness becomes less relevant. Conversely, when utility is sufficiently high for diagnosis, ensuring fairness across different demographics becomes more critical. To address these varying scenarios, a manually adjustable weighting factor is necessary to balance the trade-off between utility and fairness. Through ablation of the hyperparameter β (ranging from 0.01 to 10.0), we observe that adjusting β allows fine-tuning of the balance between utility and fairness, offering flexibility for deployers to meet specific fairness requirements based on the application context.

Our study does have limitations. We focus solely on unfairness mitigation in segmentation tasks, leaving other important tasks in medical image analysis, such as classification, detection, and low-level tasks, unevaluated. While the characteristics of our method suggest potential applicability to these tasks (e.g., the latent space between the feature extractor and the multilayer perceptron (MLP) head for classification, before ROI pooling layers for object detection, and between encoder and decoder for low-level tasks), further experiments are needed to verify its effectiveness. Additionally, current fairness measurements for segmentation tasks treat all pixels equally, which may not be ideal. Pixels at the center of the ground truth mask and those at the boundary likely carry different significance. Therefore, fairness metrics that account for pixel importance should be developed to provide a more accurate evaluation of fairness in medical segmentation tasks.

In summary, we propose an algorithm, APPLE, designed to improve model fairness in ultrasound segmentation and diagnosis tasks without altering the architecture or parameters of pre-trained base models. APPLE achieves this by perturbing the latent embeddings of the base model using a GAN, ensuring that sensitive information is not transmitted to the decoder of the segmentor. Extensive experiments on a public and a private ultrasound dataset demonstrate APPLE’s effectiveness across different base segmentors. We hope this research emphasizes the importance of fairness in AI models, draws attention to fairness in medical segmentation, and provides insights for mitigating unfairness in other tasks and foundation models, ultimately contributing to the development of a more equitable healthcare system and health equity for all.

Methods

Datasets

Two ultrasound image datasets are involved in this study, including a publicly available Thyroid UltraSound Cine-clip dataset25 (TUSC) and a private Thyroid Ultrasound dataset (QDUS)26. The TUSC dataset comprises ultrasound cine-clip images from 167 patients gathered at Stanford University Medical Center. Due to slight differences in the images extracted from the ultrasound video, we resampled the dataset at a ratio of 5, resulting in a dataset of 860 images. The download link for the TUSC dataset can be found in the Supplementary Materials. The QDUS dataset is collected from the Ultrasound Department of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, consisting of 1942 images from 192 cases, annotated by three experienced radiologists. We categorized the samples into the Male and the Female group regarding sex, and split the samples into the Young group and the Old group with a threshold of 50 years old. The data distributions of the two datasets are presented in Table 3. For both datasets, we partition them into training and testing sets with a ratio of 7:3 using a stratified sampling strategy to ensure equal representation of each subgroup.

Image pre-processing and model pre-training

Before passing the image into deep learning models, all the images were resized to 256 × 256 and normalized with a mean of (0.485, 0.456, 0.406) and standard deviation of (0.229, 0.224, 0.225). Random rotation and random flipping were applied for data augmentation.

One CNN-based segmentator, i.e., U-Net27, and one Transformer-based segmentator, i.e., TransUnet28, are used to segment the lesion part from the ultrasound images. The two models are trained from scratch following the general pipeline in ref.29. Besides, we also include two Segment Anything Models (SAM30, MedSAM31) which have been pre-trained on largescale image datasets and inspect their zero-shot performances.

The implementation details and hyperparameters can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Adversarial protected-attribute-aware perturbation on latent embeddings

The key idea of APPLE comes from the conclusion discovered in ref.24, i.e., the prediction of a model was fairer if less sensitive attribute-related information was encoded into the latent feature embeddings. This mainly resulted from the less usage of spurious relationships between the confounding attributes and the target task.

The commonly used segmentators including U-Net, TransUnet, SAM, and MedSAM can be regarded as an encoder Es and a decoder Ds.

Generally, the input image x passes the encoder and decoder sequentially and generates the predicted mask \(\hat{y}\). In our paper, the latent embedding denotes the feature vector fo extracted by the encoder Es. The subscript s denotes segmentation, while o denotes the original network. Thus, the pipeline is given by the following equation:

Based on the above motivation, we tried to mitigate unfairness by manipulating the latent Embedding, fo, which decorated the fo such that the sensitive attributes cannot be recognized from the perturbed Embedding using generative adversarial networks.

Our APPLE contains two networks, the adversarial perturbation generator Gp, and the sensitive attribute discriminator Dp. The Gp takes the original latent embedding fo as the input and generates a perturbation δ with the same shape of fo. Then, the original embedding fo and the perturbation δ are added together to get the perturbed latent embedding fp = fo + δ. Finally, the perturbed fp is passed to the decoder Ds to predict the segmentation mask. The pipeline is shown in Eq. (2).

On the other hand, the sensitive attribute discriminator Dp tried to distinguish the sensitive attribute from the perturbed latent embedding fp, which can be optimized by Equ. (3).

where a is a binary variable denoting the sensitive attributes of the sample. a = 0 denotes the male/young group, while a = 1 denotes the female/old group.

The loss function of the perturbation generator Gp consisted of two parts: the segmentation utility preserving part \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{G}^{seg}\) and the fairness constraining part \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{G}^{fair}\). \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{G}^{seg}\) was defined as the Dice-CE Loss between the predicted mask and the ground truth mask as shown in Eq. (4):

The fairness constraints part aimed to generate perturbations that confuse the distinction of the sensitive attribute, which was controlled by the negative cross-entropy loss of sensitive attribute prediction. Besides, a regularization \({\mathcal{H}}\) termed on the entropy of Dp(fp) was added to avoid space collapse. Therefore, \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{G}^{fair}\) was given by Eq. (5):

where \({\mathcal{H}}\) is the entropy. Therefore, the overall loss of Gp was defined as Equ. (6):

Where β is the weighted factor that balances the requirements for fairness and utility, a higher β means that the model requires more utility than fairness.

Specifically, The Gp consisted of a 3-layer encoder with channels of (32, 64, 128), a 4-layer ResBlock-based bottleneck, and a 3-layer decoder with channels of (64, 32, Nec), where Nec is the number of embedding channels. The Dp is composed of 3 Linear-BatchNorm blocks, and the output dim is set to the number of classes of sensitive attributes. The detailed architectures of Gp and Dp are shown in Fig. 7.

a Pipeline of the proposed method. x: input image; y: ground truth segmentation mask; \(\hat{y}\): predicted segmentation mask; Es: segmentation encoder; Ds: segmentation decoder; Gp: perturbation generator; Dp: perturbation discriminator; fo: origin feature vector; fp: perturbed feature vector; pa: predicted attribute; a: sensitive attribute; \({\mathcal{H}}\): entropy; α, β: weighted factor. b Detailed scheme of Gp; (c) Detailed scheme of Dp. Note that the parameters of Es and Ds were pre-trained and frozen, only the parameters of Gp and Dp were trainable.

Following adversarial training, our proposed APPLE was optimized by the min-max game, and the pseudocode of our algorithm was presented in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1

Pseudo code of APPLE

Input: Encoder Es, Decoder Ds, input image x, segmentation mask y, sensitive attribute a, weighted factor α, β, number of epoch Nepoch

for i = 1: Nepoch do

Get the original latent embedding: fo ← Es(x).

Get the perturbed latent embedding: fp ← fo + Gp(fo).

Get the predicted segmentation mask: \(\hat{y}\leftarrow {D}_{s}({f}_{p})\).

Compute Loss of Dp: \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{D}={{\mathcal{L}}}_{CE}({D}_{p}({f}_{p}),a)\).

Optimize Dp using \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{D}\).

Compute Fairness Loss of Gp: \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{G}^{fair}=-{{\mathcal{L}}}_{CE}({D}_{p}({f}_{p}),a)-\alpha {\mathcal{H}}({D}_{p}({f}_{p}))\).

Compute Segmentation Loss of Gp: \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{G}^{seg}=\frac{1}{2}({{\mathcal{L}}}_{CE}(y,\hat{y})+{{\mathcal{L}}}_{Dice}(y,\hat{y}))\).

Optimize Gp using \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{G}=\beta {{\mathcal{L}}}_{G}^{seg}+{{\mathcal{L}}}_{G}^{fair}\).

end for

Output: Perturbation Generator Gp and Discriminator Dp

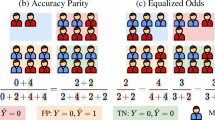

Fairness criteria for segmentation and downstream diagnosis

Metrics evaluating segmentation utility, diagnosis parameters, and fairness are used to validate the effectiveness of our proposed method.

Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) is used to measure the precision of the predicted segmentation mask, which is given by (7).

where y and \(\hat{y}\) denoted the ground truth mask and predicted mask, respectively.

For radiomics parameters, three metrics, including the surface area, perimeter, and the energy of the lesion part are selected and calculated using PyRadiomics16 for diagnosis.

As for fairness criteria, following previous work23, we use the subgroup disparity (DSCΔ), standard deviation (DSCSTD), and skewness (DSCSKEW), which are given by Eqs. (8),(9), and (10).

where \(\overline{\,\text{DSC}}=\frac{1}{K}\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{k = 1}^{K}{\text{DSC}}^{k}\), and DSCk is the utility on the k-th subgroup.

Data availability

The TUSC dataset used in this study is available on the original website.https://stanfordaimi.azurewebsites.net/datasets/a72f2b02-7b53-4c5d-963c-d7253220bfd5The QDUS dataset is not publicly available due to the policy of the hospital, but is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. https://github.com/XuZikang/APPLE.

Code availability

All the code used in this study can be found in https://github.com/XuZikang/APPLE.

References

Zhou, S.K. et al. A review of deep learning in medical imaging: Imaging traits, technology trends, case studies with progress highlights, and future promises. In: Proc. of the IEEE (2021).

Van Sloun, R. J., Cohen, R. & Eldar, Y. C. Deep learning in ultrasound imaging. Proc. IEEE 108, 11–29 (2019).

Jiao, J. et al. USFM: a universal ultrasound foundation model generalized to tasks and organs towards label efficient image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 96, 103202 (2024).

Booth, B. M. et al. Bias and fairness in multimodal machine learning: a case study of automated video interviews. In: Proc. 2021 Int. Conf. Multimodal Interact. (ICMI 2021), 268–277 (2021).

Jin, R., Deng, W., Chen, M. & Li, X. Debiased noise editing on foundation models for fair medical image classification. Int. Conf. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assist. Interv. (MICCAI 2024), 164–174 (Springer, 2024).

Xu, Z. et al. Addressing fairness issues in deep learning-based medical image analysis: a systematic review. npj Digit. Med. 7, 286 (2024).

Li, Y., Wang, H. & Luo, Y. Improving fairness in the prediction of heart failure length of stay and mortality by integrating social determinants of health. Circ. Heart Fail. 15, e009473 (2022).

Puyol-Antón, E. et al. Fairness in cardiac MR image analysis: an investigation of bias due to data imbalance in deep learning based segmentation. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. MICCAI 2021: 24th Int. Conf., Strasbourg, France, Sept. 27-Oct. 1, 2021, Proc., Part III, 413–423 (Springer, 2021).

Pombo, G. et al. Equitable modelling of brain imaging by counterfactual augmentation with morphologically constrained 3d deep generative models. Med. Image Anal. 84, 102723 (2023).

Oguguo, T. et al. A comparative study of fairness in medical machine learning. 2023 IEEE 20th Int. Symp. Biomed. Imaging (ISBI 2023), 1–5 (IEEE, 2023).

Stanley, E. A., Wilms, M. & Forkert, N. D. Disproportionate subgroup impacts and other challenges of fairness in artificial intelligence for medical image analysis. Workshop on the Ethical and Philosophical Issues in Medical Imaging 14–25 (Springer, 2022).

Wu, Y., Zeng, D., Xu, X., Shi, Y. & Hu, J. Fairprune: achieving fairness through pruning for dermatological disease diagnosis. Intenational Conference Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention. (MICCAI 2022), 743–753 (Springer, 2022).

Xiao, C. et al. Generating Adversarial Examples with Adversarial Networks. In: Proc. of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence Main Track. (IJCAI-18), 3905–3911 (International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Fairness-aware adversarial perturbation towards bias mitigation for deployed deep models. In: Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. (CVPR 2022), 10379–10388 (2022).

Dice, L. R. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology 26, 297–302 (1945).

Van Griethuysen, J. J. et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 77, e104–e107 (2017).

Tian, Y. et al. Fairseg: A large-scale medical image segmentation dataset for fairness learning using segment anything model with fair error-bound scaling. The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Towards fairness in visual recognition: effective strategies for bias mitigation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR 2020), 8919–8928 (2020).

Manning, C. & Schutze, H. Foundations of statistical natural language processing (MIT Press, 1999).

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

Davies, D. L. & Bouldin, D. W. A cluster separation measure. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 224–227 (1979).

Rousseeuw, P. J. Silhouettes: a graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 20, 53–65 (1987).

Jin, R. et al. Fairmedfm: fairness benchmarking for medical imaging foundation models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 37, 111318–111357 (2024).

Kim, B., Kim, H., Kim, K., Kim, S. & Kim, J. Learning not to learn: training deep neural networks with biased data. In: Proc. of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2019), 9012–9020 (2019).

shared datasets, S. A. Thyroid ultrasound cine-clip https://doi.org/10.71718/7m5n-rh16. Data set (2021).

Ning, C.-p et al. Distribution patterns of microcalcifications in suspected thyroid carcinoma: a classification method helpful for diagnosis. Eur. Radiol. 28, 2612–2619 (2018).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. MICCAI 2015: 18th Int. Conf., Munich, Germany, Oct. 5-9, 2015, Proc., Part III, 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Chen, J. et al. Transunet: rethinking the U-Net architecture design for medical image segmentation through the lens of transformers. Med. Image Anal. 97, 103280 (2024).

Tang, F., Wang, L., Ning, C., Xian, M. & Ding, J. Cmu-net: a strong convmixer-based medical ultrasound image segmentation network. 2023 IEEE 20th Int. Symp. Biomed. Imaging (ISBI 2023), 1–5 (IEEE, 2023).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. In Proc. 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 4015–4026 (2023).

Ma, J. et al. Segment anything in medical images. Nat. Comm. 15, 654 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62271465 and U22A2033, Suzhou Basic Research Program under Grant SYG202338, Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (No ZR2020MH290), and Open Fund Project of Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences, China (No YKY-KF202206).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.X., F.T., Q.Q., and S.K.Z. designed the study. J.D. and C.N. collected and cleansed the data. Z.X., F.T., Q.Q., and Q.K. developed the experiments. Z.X., Q.Q., and Q.Y. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Z., Tang, F., Quan, Q. et al. Fair ultrasound diagnosis via adversarial protected attribute aware perturbations on latent embeddings. npj Digit. Med. 8, 291 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01641-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01641-y