Abstract

In acute ischemic stroke due to large-vessel occlusion (AIS-LVO), late-window endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) decisions depend on penumbra-to-core (P:C) mismatch from computed tomographic perfusion (CTP). We developed multiple machine learning (ML) models to predict P:C ratios from a retrospectively-identified cohort of AIS-LVO patients who underwent CTP within 30 min of initial neuroimaging, using non-imaging electronic health record (EHR) data available prior to CTP evaluation. We extracted structured data and free-text clinical notes from the EHR, generating document embeddings as sums of BioWordVec vectors weighted by term-frequency-inverse-document-frequency scores. We identified 120 patients; an extreme-gradient-boosting model classified P:C ratios as ≥ or <1.8, achieving an AUROC of 0.80 (95% CI 0.57–0.92) with optimal performance using text limited to 500 characters. Sensitivity was 0.80, specificity 0.66, and F1 score 0.86. Our findings suggest that ML models leveraging real-world non-imaging data can potentially aid LVO-AIS triage, though further validation is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) is the standard of care for treating acute ischemic stroke (AIS) from proximal large-vessel occlusion (LVO) in the anterior circulation and is rapidly becoming standard treatment for LVO in the posterior circulation1. In this context, current guidelines recommend the use of CT perfusion (CTP) imaging, which can estimate and distinguish volumes of salvageable penumbra from ischemic core, to aid in selecting patients for EVT in the 6–24 h window. More specifically, multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have previously used a penumbra-to-core (P:C) volume ratio greater than or equal to 1.8 to select patients for EVT in both early and late treatment windows2,3.

Recent evidence suggests that CTP has utility in selecting patients for EVT in the setting of AIS due to LVO. In two recent RCTs, specific core volume thresholds were associated with attenuation of EVT’s beneficial effects on functional outcomes in patients with AIS due to LVO, and the presence of clinical-core mismatch as measured by perfusion imaging was associated with functional outcome following EVT4,5. Additionally, a recent retrospective single-center study suggests that patient selection based on a P:C ratio below 1.8 in the early treatment window was independently associated with poor functional outcome at 90 days6. Finally, a recent worldwide survey of stroke providers suggests that most use advanced imaging such as CTP to select patients with LVO-AIS for EVT in the late treatment window7.

While CTP may remain useful for patient selection, this imaging modality presents numerous disadvantages. CTP postprocessing, which generates human-interpretable volume maps for clinical decision-making, inherently requires additional time beyond initial stroke imaging tests such as non-contrast CT head (CTH) and CT angiography (CTA) imaging8. CTP has been shown to add a mean of approximately 20 min to AIS care workflows9. CTP also demonstrates suboptimal contrast-to-noise ratio and susceptibility to motion and contrast-related artifacts, especially in patients with congestive heart failure or carotid occlusion10. Moreover, accessibility to CTP is limited, particularly in low to middle income countries and certain regions of the United States11,12. Debates also exist regarding the consistency of perfusion maps generated by different software platforms and the reliability of CTP in accurately predicting tissue status and clinical outcomes13,14. Due to the time sensitivity of AIS, these factors all contribute to treatment delays that can lead to patient harm.

There is growing interest in developing tools for identifying patients for EVT that do not rely on CTP. Recent work supports the use of simple CTH imaging as patient selection method in the late window, potentially obviating the need for CTP altogether15,16, whereas other groups have sought to apply machine learning (ML) to identify core and penumbra volumes from CTH17. However, these approaches remain reliant on neuroimaging, underlining an emerging need to correctly quantify core and penumbra volumes using only non-imaging data that are available well before neuroimaging is obtained. These data include text from clinical notes, sociodemographic information, and medical history stored as free text data in the electronic health record (EHR). In this study, we sought to develop a ML model based on natural language processing (NLP) techniques to predict P:C ratio in patients presenting with AIS due to LVO.

Results

Study Cohort and Included Note Characteristics

Over the 25-month study period, we identified 688 patients who underwent a CTP within 30 min of either CTA or CTH for evaluation of suspected LVO-AIS, of whom we excluded 568 (82.6%), most frequently due to lack of interpretable diagnostic CTP images or apparent penumbra (N = 148), lack of LVO on CTA (N = 141), and the presence of high-grade/critical stenoses attributable to the presenting symptoms (N = 58). We excluded an additional 9 patients who met all other criteria, but lacked any notes written within the time window of interest. The final cohort was comprised of 120 patients, of whom 52 (43.3%) were female, the median age was 70.4 (SD 13.7), 106 (88.3%) had a P:C ratio greater or equal to 1.8, and 109 (90.8%) had anterior circulation occlusions. The median CTP penumbra and core volumes were 91.5 cc (IQR: 40.8–164.5) and 7.4 cc (IQR: 0.0–30.3), respectively. The median time between initial neuroimaging and CTP was 22.7 min (IQR: 16.8–29.9), with CTP being obtained at a median of 13.7 h (IQR: 8.9–23.2) after last known well (Table 1).

The median length of each patient’s notes was 3187.5 (IQR 357.0–18,929.7) characters in the overall corpus, and 283.0 (IQR: 144.7–1950.5) characters for notes written closest to the CTP scan. To include both median values as well as provide an intermediate threshold between both median values, we chose minimum character thresholds of 500, 1,000, and 5,000 characters. At the lowest minimum character threshold (500), notes included in the model were written at a median of 29.8 min (IQR 15.6–92.9) before CTP time. This time increased along with the character threshold value (Table 2).

Optimal Model Performance and Classification Metrics

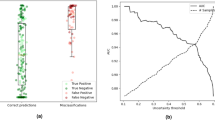

Our best performing full (i.e., combined structured and unstructured text data) model used an extreme-gradient boosting (XGBoost)18 architecture and a note threshold of 500 characters, resulting in an AUROC of 0.80 (95% CI 0.57–0.92) (Fig. 1a). This model also outperformed the best-performing models (including XGBoost) with minimum character thresholds of 1000 (all-text; AUROC 0.73, 95% CI 0.49–0.91) (Fig. 1b), and 5000 (all-text; AUROC 0.62, 95% CI 0.38–0.83) respectively (Fig. 1c). Interestingly, the performance of the text-only XGBoost model with a 500-character threshold was only marginally lower than the full model’s (AUROC 0.79, 95% CI 0.57–0.91) (Fig. 1a). The performance of the structured-only XGBoost model was inferior to chance (AUROC 0.41, 95% CI 0.14–0.70).

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves for models trained using structured features only (red), document embeddings only (green), and both structured features and document embeddings (blue). Panels (a), (b), and (c) correspond to models trained with text data generated with cutoffs of 500, 1000, and 5000 characters, respectively. The dashed line represents the performance of a random classifier (AUROC = 0.5).

Average confusion matrices for each full model at the decision threshold that maximized Youden’s Index across all bootstraps are shown in Fig. 2. Since classifier performance metrics depend on the chosen decision threshold, we report performance metrics for the best-performing model at thresholds optimized for various sensitivity targets (Table 3). At a threshold selected to balance sensitivity and specificity, the best-performing full model achieved sensitivity 0.80 (95% CI:0.50–0.94), specificity 0.66 (95% CI:0.50–1.00), precision 0.95 (95% CI:0.91–1.00), and F1 score 0.86 (95% CI:0.65–0.95) (Table 3).

Confusion matrices for the full model are presented for three different text-cutoff thresholds (500, 1000, and 5000 characters) in panels (a), (b), and (c), respectively. For each cutoff, the optimal classification threshold was determined by maximizing Youden’s index (i.e., maximizing the sum of sensitivity and specificity, which corresponds to the sum of the row-normalized diagonal elements). Each cell in the matrices represents the proportion of cases for the true class (expressed as a percentage), with the axes labeled “P:C < 1.8” and “P:C ≥ 1.8” indicating the binary classification outcome for the penumbra-to-core ratio.

Impact of Note Author Type on Model Performance

This best performing model was built using text from 188 unique notes which were written by 147 unique authors. The latest note included for each sample in this model was authored at a median of 5.2 min prior to (IQR: 23.1 min prior to, 5.6 min after) the earliest neuroimaging (either CTA or CTH). Of the 188 notes included in this model, 104 (55.3%) were written by registered nurses, 35 (18.6%) were written by Resident Physicians, and 25 (13.3%) were written by Attending Physicians. 142 (75.5%) of the notes were written by authors from the Emergency Medicine service. A Kruskal-Wallis test indicated that there was no significant differences in samples’ combined rank score based on the author types of notes included in that sample (p = 0.20). We also used the combined ranking to identify samples that were most often misclassified by the model, and the 5 lowest scoring samples were analyzed manually. Upon reviewing these poorly classified samples, we observed that there is often dilution of the note content by irrelevant notes or extensive focus on procedural or logistical details. Examples of note text for two of those samples are included in Supplementary Figure 1.

Discussion

In this retrospective study of patients presenting with AIS due to LVO, we successfully developed a predictive ML model based on clinical note text and structured data to classify a binary P:C ratio of 1.8, as measured by post-processed CTP imaging. We used a novel computational approach to pre-process clinical note text data, by first extracting meanings by way of a validated biomedical word embedding library and then applying TF-IDF weighting. We furthermore applied a second level of pre-processing to minimize signal-to-noise ratios in the clinical text by limiting the size of the included text to pre-determined character thresholds. Our model demonstrated good discriminatory performance using a patient-level corpus character threshold of 500, which generated predictions at a median lead time of approximately 30 min ahead of CTP scan times and 5 min ahead of initial neuroimaging.

To contextualize our results, Sheth and colleagues previously developed a deep learning model to classify the presence of CTP ischemic core volume greater than 30 cc from CTA images, which demonstrated an AUROC of 0.8819. Our approach fundamentally differs in multiple ways, namely that (a) we used exclusively non-imaging data as predictor data and (b) we predicted an outcome reflective of both core and penumbra volumes. Our findings suggest that critical information about perfusion imaging findings that can inform treatment candidacy determinations may be quickly derivable from patient data that is recorded in the EHR shortly after presentation with stroke symptoms. While we are encouraged by recent advances in image-based models for predicting P:C ratios and other CTP outcomes from CTA, as investigated by other authors, we view our text-based approach as orthogonal to these imaging-based efforts, offering an additional layer of data that could ultimately improve multimodal model performance. While these results are preliminary and based on a small sample, if replicated in larger studies and evaluated in a comparative effectiveness study to standard stroke imaging-based selection, this approach could be used to assist identification of actionable AIS with LVO, particularly in settings where access to neuroimaging or neurological expertise is limited– thereby allowing earlier escalation to thrombectomy capable centers.

The findings from our ablative analyses suggest that the pre-processed clinical note text contained the most salient signal for our chosen outcome, while demographic and comorbidity data were much less predictive. Clinical notes capture concepts that are more closely related to stroke presentation, such as symptomatology, size, severity, as well as pertinent medical history and physical examination, than comorbidities and demographics.

Our analysis suggests that signal-to-noise ratios in unstructured text data were inversely related to prediction lead time before CTP. Compared to high character thresholds, lower character thresholds tended to generate model predictions that were closer to the CTP time but also later in the stroke care pathway. Although increasing amounts of clinical text data generally translated to worse performance due to worse signal-to-noise ratios than at lower character thresholds, our best-performing model achieved moderate to good discriminatory performance while generating predictions approximately 30 min prior to CTP scan time.

Although our use of word embedding to pre-process the clinical note text data demonstrated effectiveness in differentiating relevant signals within a reasonable timeframe before the CTP scan, we expect further studies using a larger patient population will identify an optimal threshold that balances prediction accuracy and speed. This suggests a promising direction for future studies.

This study has several strengths. Most importantly, it constitutes a proof of concept for encoding semantic meaning from unstructured biomedical text data by scaling weighted sums of word embeddings by TF-IDF scores. Furthermore, our results suggest that it is possible to use ML to capture clinically relevant signals that can inform decision-making prior to neuroimaging being obtained. Our analysis also supports the notion that the model’s performance was not biased toward specific disciplines or author types and therefore did not rely too heavily on expertise of individual note writers. Given the wide range of author types and note types included, our model incorporated a heterogeneous mixture of standardized and non-standardized notes. This heterogeneity may further highlight the model’s capacity to extract meaningful features from diverse text sources.

Several limitations warrant consideration, however. First, this was a retrospective model derivation study based on a patient cohort drawn from a separate research study rather than all patients who had CT perfusion imaging for evaluation of suspected AIS. Second, there was a relatively large class imbalance in the dataset, with most patients having a P:C ratio >= 1.8. Third, while our document embedding approach using BioWordVec and TF-IDF is innovative, it is limited in that it produces non-human interpretable text representations, creating challenges for model operationalization. This was observed most saliently in our manual review of samples which were most often misclassified by the model. Currently, the model does not account for note quality or prioritize more informative sections of the text. These could be avenues for future exploration to refine this approach. Fourth, our algorithm predicted binary P:C ratios only rather than point estimates of penumbra or core values, which could provide a more precise and nuanced assessment of patient candidacy for thrombectomy. Fifth, we used a semi-empiric approach to select note character thresholds to minimize text-related noise, although this limitation could be addressed in the future by ML algorithms that could determine optimal character cutoffs.

Finally, this study was conducted at a single center, limiting its generalizability to other institutions with different documentation practices, patient populations, and clinical workflows. While our model incorporated notes from a diverse set of providers across multiple services multi-center validation will be essential to assess model performance across diverse settings and ensure robustness in broader clinical applications. As such we urge caution in interpreting these results until further validation studies are performed.

Our study lays the foundation for an NLP-based approach at leveraging clinical notes for prediction of key CTP findings in AIS due to LVO prior to advanced neuroimaging. Studies conducted in larger, more representative populations and attempting to predict continuous penumbra and core volumes should attempt to replicate our findings and address outlined limitations.

Methods

Study Design & Patient Population

This was a retrospective model derivation study using patient data from the Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS), a multi-site, tertiary-care hospital network in New York City comprising 2 academic medical centers and 5 community hospitals. The Institutional Review Board of Mount Sinai approved the use of patient data for this research under IRB # 19–00738. The MSHS is one of the highest volume academically-affiliated stroke centers in the New York metropolitan area, with approximately 2400 admissions for acute stroke and 240 EVT procedures annually. The patient population in this derivation study was drawn from a separate, unpublished experiment in which a convolutional neural network (deep learning) model was developed to estimate CTP core and penumbra volumes directly from CTH images. The population from this separate analysis was comprised of patients who underwent acute CTP imaging within 30 min of hyperacute CTH or CTA imaging for suspected acute stroke between May 14th, 2019, and June 15th, 2021. The start date of this period coincided with the release of a commercial CTP post-processing algorithm (VIZ.ai, San Francisco, CA) across MSHS on May 14th, 2019.

We excluded patients who were not evaluated for suspected stroke or had any primary intracranial (intraparenchymal, subarachnoid, or subdural) hemorrhage. We also excluded patients who lacked interpretable diagnostic CTP images, arterial occlusions, or appreciable penumbra as measured by volume of time-to-maximum attenuation (Tmax) greater than 6 s. We also excluded patients whose presenting symptoms could not be attributed to an LVO and patients who had known chronic infarcts in the culprit arterial territory.

Measurements

Using our institutional radiology picture and archive communication (PACS) web viewer, we manually extracted the VIZ.ai – generated CTP penumbra and core volumes for each patient and computed the P:C ratio20. Based on prior published work, we defined “penumbra” as an area on CTP with Tmax>6 s compared to the contralateral cerebral hemisphere, and “core” as relative CBF below 30% of the contralateral hemisphere21. We trained an ML model using structured and free-text data to classify the P:C ratio into one of two binary categories (>=1.8 or <1.8).

Predictor Variables – Structured Data

From our institutional data warehouse, we collected clinical and sociodemographic variables at the time of evaluation, including sex, race, preferred language, medical comorbidities, presenting NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, time from last known well to CTP, time from CTH to CTP (including both image acquisition and postprocessing), and location of arterial occlusion. Using each patient’s medical history, which was encoded in a series of International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes immediately prior to their scan time, we calculated an Elixhauser comorbidity index for each patient. Categorical variables were encoded using one-hot vectors.

Predictor Variables – Unstructured Text

We extracted the free-text data of all notes written within one week prior to each patient’s CTP scan time. To reduce non-contributory text (or “noise”), we limited the included text by a pre-specified character threshold. Because notes written closer to the time of neuroimaging were more likely to contain clinically relevant information predictive of the outcome, we constructed a “patient-level corpus” by sequentially adding entire clinical notes in reverse chronological order, starting from the CTP scan, until the character threshold was reached. Here, the term “corpus” refers to a large collection of text or speech data used for NLP tasks22,23.

This process resulted in a character-limited subset of text for each patient. Full notes were included without cropping, and if the note closest to the CTP scan exceeded the character threshold, only that note was incorporated into the model (Fig. 3). We selected conservative character thresholds that captured the median note length both for the overall corpus and for notes written closest to the CTP scan.

Flowchart illustrating the five-step pipeline for constructing document embeddings. The process begins with selecting clinical notes based on a predefined character cutoff threshold, followed by text preprocessing. Next, term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) weighting is applied to each participant’s text corpus (“patient-level corpora”). Preprocessed text is then mapped to word embeddings using BioWord2Vec, and a final document-level embedding is obtained by matrix-multiplying the TF-IDF matrix with the word embedding matrix.

All patient-level corpora also underwent a series of routine free-text preprocessing steps, which included converting all characters to lowercase, removing stop words, removing punctuation marks, and applying stemming and lemmatization to simplify words to their basic forms. To maximize model generalizability and ensure the algorithm did not learn patient-specific data (e.g., unique names, addresses, etc.), we excluded any words that were unique to a single patient.

To transform the free-text patient-level corpora into a format our model could ingest, we employed a combination of two NLP techniques: term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) and word embedding. TF-IDF is a mathematical method that outputs a score indicating the frequency of any given word within a particular patient’s text corpus compared to the clinical notes of all other patients24,25. By contrast, word embedding encodes each word in a text document as a vector, or a string of numbers, in a high-dimensional space. This process ensures that words with similar meanings or usage contexts are positioned close to each other in this space. An effective analogy is the postal system: each word is assigned an “address”, such that words with related meanings or frequent co-occurrences receive “addresses” that are mathematically close to each other in semantic space. This allows us to capture semantic relationships between words in a quantifiable manner and is commonly used in NLP work26,27,28.

Because patient notes varied widely in formatting, author types, abbreviations, and word counts, we employed a specific combination of approaches to represent clinical text from patient notes in a consistent and low-dimensional form. We sought to combine signals implicit to individual word meanings with signals in how those words were relatively distributed across all patients’ notes (Fig. 3). To accomplish this, we first converted each word in each patient-level corpus into vectors using an open-source set of 200-dimensional biomedical word embeddings that were pre-trained on a large corpus of clinical notes and medical texts (BioWordVec)29.

We then generated document-level vectors by summing and weighting patient-level vectors by respective TF-IDF scores. We then concatenated structured data and weighted document vectors and scaled all features using a linear transform. Missing values were estimated using a 5-nearest neighbor imputation approach.

Model Development & Performance Measurement

We trained ten different model architectures, including k-nearest neighbors, support vector classifier, decision tree, random forest, adaptive boosting, gradient boosting, Gaussian naïve Bayes, linear discriminant analysis, quadratic discriminant analysis, and extreme-gradient boosting (XGBoost) models on these features to classify P:C > = 1.8 as a binary outcome18,30,31,32,33. We also determined sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1 score for each model, as well as area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUROC). We defined the best-performing model as the combination of model architecture and character threshold which maximized the AUROC. We used a bootstrapping approach in which 1000 random, stratified 70/30 train-test splits were used to generate distributions for each of the performance measures we assessed.

We also evaluated model performance using an iterative approach to identify the decision threshold that maximized Youden’s Index (a measure of diagnostic test accuracy, calculated as sensitivity + specificity - 1) and reporting the confusion matrix for the models average performance at that threshold across all bootstraps.

In addition to training full models on both the structured and text data, we also performed ablative analyses in which we trained two additional versions of the best-performing model using structured-only and text-only data inputs as feature sets. To evaluate whether different minimum character thresholds affected model performance, we also trained 3 different versions of the most performant model corresponding to the 3 different character thresholds.

Analyses of Factors Affecting Model Performance

We conducted a post-hoc analysis to identify which samples the model consistently failed to correctly classify across all bootstraps and to determine whether there were interpretable factors contributing to these misclassifications. To achieve this, we calculated the average probability of each sample being classified into its true class, across all bootstraps. To account for class imbalance, we normalized these probabilities within each class by scaling them relative to the best-performing sample in that class. This normalization ensured that inherent differences in sample distribution did not disproportionately lower minority class probabilities. We then combined these scores into a single “combined rank” score spanning both classes.

Next, to determine whether the model’s performance was influenced by the author type (e.g., registered nurses, resident physicians, attending physicians), we conducted a Kruskal-Wallis to assess whether author type was significantly associated with the combined rank score. Additionally, we used the combined rank score to identify the most consistently misclassified samples and manually reviewed the clinical notes associated with the five lowest scoring cases. This qualitative review aimed to determine whether errors in classification were linked to human-interpretable discrepancies in note quality, such as missing information, ambiguous language, or variations in documentation style.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study constitute protected health information, and therefore are not freely available. Limited data may be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to the approval from the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board.

Code availability

The code for our developed model has been made publicly available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/shaunk24/CTP_NLP).

References

Powers, W. J. et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 50, e344–e418, https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000211 (2019).

Saver, J. L. et al. Solitaire™ with the Intention for Thrombectomy as Primary Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke (SWIFT PRIME) trial: protocol for a randomized, controlled, multicenter study comparing the Solitaire revascularization device with IV tPA with IV tPA alone in acute ischemic stroke. Int J. Stroke 10, 439–448 (2015).

Albers, G. W. et al. Thrombectomy for Stroke at 6 to 16 h with Selection by Perfusion Imaging. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 708–718 (2018).

Huo, X. et al. Trial of endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke with large infarct. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1272–1283 (2023).

Sarraj, A. et al. Trial of endovascular thrombectomy for large ischemic strokes. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1259–1271 (2023).

Schwarz, G. et al. Perfusion imaging mismatch profiles in the early thrombectomy window: a single-center analysis. Stroke 54, 1182–1191, https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.041981 (2023).

Nguyen, T. N. et al. Late window imaging selection for endovascular therapy of large vessel occlusion stroke: An International Survey. Stroke Vasc. Inter. Neurol. 3, e000595. https://doi.org/10.1161/SVIN.122.000595 (2023).

Christensen, S. & Lansberg, M. G. CT perfusion in acute stroke: practical guidance for implementation in clinical practice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 39, 1664–1668, https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678X18805590 (2019).

Goyal, M. et al. Analysis of workflow and time to treatment and the effects on outcome in endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke: results from the SWIFT PRIME Randomized Controlled Trial. Radiology 279, 888–897, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2016160204 (2016).

Katyal, A. & Bhaskar, S. M. M. Value of pre-intervention CT perfusion imaging in acute ischemic stroke prognosis. Diagn. Inter. Radio. 27, 774–785, https://doi.org/10.5152/dir.2021.20805 (2021).

Kim, Y. et al. Utilization and availability of advanced imaging in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Circ. Cardiovasc Qual. Outcomes 14, e006989, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006989 (2021).

Czap, A. et al. E-048 Real world availability and utilization of CT perfusion in acute ischemic stroke. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 11 (2019).

Fahmi, F. et al. Differences in CT perfusion summary maps for patients with acute ischemic stroke generated by 2 software packages. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 33, 2074–2080, https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A3110 (2012).

Bushnaq, S. et al. A Comparison of CT Perfusion Output of RapidAI and Viz.ai Software in the Evaluation of Acute Ischemic Stroke. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 45, 863–870, https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A8196 (2024).

Nguyen, T. N. et al. Noncontrast Computed Tomography vs Computed Tomography Perfusion or Magnetic Resonance Imaging Selection in Late Presentation of Stroke With Large-Vessel Occlusion. JAMA Neurol. 79, 22–31 (2022).

Masoud, H. E. et al. 2022 Brief Practice Update on Intravenous Thrombolysis Before Thrombectomy in Patients With Large Vessel Occlusion Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Statement from Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology Guidelines and Practice Standards (GAPS) Committee. Stroke Vasc. Inter. Neurol. 2, e000276. https://doi.org/10.1161/SVIN.121.000276 (2022).

Lo, C.-M., Hung, P.-H. & Lin, D.-T. Rapid assessment of acute ischemic stroke by computed tomography using deep convolutional neural networks. J. Digit Imaging 34, 637–646, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-021-00457-y (2021).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (Association for Computing Machinery, San Francisco, California, USA, 2016).

Sheth, S. A. et al. Machine learning-enabled automated determination of acute ischemic core from computed tomography angiography. Stroke 50, 3093–3100, https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.119.026189 (2019).

Soun, J. E. et al. Artificial intelligence and acute stroke imaging. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 42. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6883, (2020).

Albers, G. et al. Tenecteplase for stroke at 4.5 to 24 h with perfusion-imaging selection. N. Engl. J. Med. 390, 701–711 (2024).

Pyysalo, S. et al. BioInfer: a corpus for information extraction in the biomedical domain. BMC Bioinform 8, 50, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-8-50 (2007).

Lee, J. et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 36, 1234–1240, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz682 (2019).

Afzal, M., Park, B. J., Hussain, M. & Lee, S. Deep Learning Based Biomedical Literature Classification Using Criteria of Scientific Rigor. Electronics 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9081253 (2020).

Bannach-Brown, A. et al. Machine learning algorithms for systematic review: reducing workload in a preclinical review of animal studies and reducing human screening error. Syst. Rev. 8, 23, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-0942-7 (2019).

Xing, R., Luo, J. & Song, T. BioRel: towards large-scale biomedical relation extraction. BMC Bioinform 21, 543, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-020-03889-5 (2020).

Tao, J., Brayton, K. A. & Broschat, S. L. Automated Confirmation of Protein Annotation Using NLP and the UniProtKB Database. Appl. Sci. 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11010024 (2021)

Najdenkoska, I. et al. 625–635 (Springer International Publishing).

Zhang, Y., Chen, Q., Yang, Z., Lin, H. & Lu, Z. BioWordVec, improving biomedical word embeddings with subword information and MeSH. Sci. Data 6, 52, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0055-0 (2019).

Friedman, J. Stochastic gradient boosting. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 38, 367–378 (2002).

Kourou, K., Exarchos, T. P., Exarchos, K. P., Karamouzis, M. V. & Fotiadis, D. I. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 13, 8–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2014.11.005 (2015).

Chaurasia, V. & Pal, S. Applications of machine learning techniques to predict diagnostic breast cancer. SN Comput. Sci. 1, 270, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-020-00296-8 (2020).

Fernandez-Delgado, M., Cernadas, E., Barro, S. & Amorim, D. Do we need hundreds of classifiers to solve real world classification problems?. J. Mach. Learn Res. 15, 3133–3181 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under R01 grants R01HL155915 and R01HL167050 (G.N.); and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under grant UL1TR004419 (B.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project conceptualization: B.K. Generating/collecting data: S.K., H.C. and B.K. Analysis of data: S.K., P.A., A.E. Interpretation of data: S.K., H.C., A.E., P.A., G.N. and B.K. Manuscript drafting: S.K. Figure preparation: S.K., A.E. Critical review of manuscript for key intellectual content: S.K., H.C., A.E., P.A., G.N. and B.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.N. serves as an Associate Editor of NPJ Digital Medicine. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kohli, S., Agarwal, P., Ho Wing Chan, “. et al. Machine learning to predict penumbra core mismatch in acute ischemic stroke using clinical note data. npj Digit. Med. 8, 340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01703-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01703-1

This article is cited by

-

Magnetic NeuroRing: a portable adaptive brain-computer interface for real-time transcranial magnetic stimulation in post-stroke motor rehabilitation

npj Biomedical Innovations (2026)

-

From retina to brain: how deep learning closes the gap in silent stroke screening

npj Digital Medicine (2025)