Abstract

To evaluate the effectiveness of a digital medication system in improving adherence among patients with serious mental disorders (SMD), we conducted a cluster-randomized controlled trial across 30 communities in Beijing. Participants, aged 18–65 years, were diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and either received intermittent medication or refused treatment. Recruitment occurred from September 2, 2022, to January 12, 2023. The intervention group received a digital medication system. The control group used an online medication diary. The primary outcome was poor adherence, defined as missing 20% or more of prescribed doses at 12 months. Among 216 recruited patients, 206 completed the study. The intervention group showed significantly higher adherence (84/108 vs. 23/108), with an adjusted risk difference of 52.34% (95% CI: 34.65%–70.03%; P < 0.0001). This trial provides the first robust evidence that the digital medication system can significantly improve medication adherence in patients with SMD. Trial Registration: The trial was registered on the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (chictr.org.cn) on May 29, 2022 (ChiCTR-ICR-2200060359).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) defines severe mental disorders (SMD) as a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities1. These disorders primarily include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder2, and in some studies, major depressive disorder is also included3. SMD contributes to considerable suffering, disability, and premature mortality, resulting in substantial societal costs4. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that schizophrenia affects approximately 24 million people globally5, with nearly 50% of mental hospital patients—those receiving specialized inpatient care and long-term residential services due to mental disorders—diagnosed with this condition6. Bipolar disorder affects over 45 million people worldwide7, with a lifetime prevalence of 2.5% in men and 2.3% in women8. SMDs are characterized by high relapse rates and persistent disability9, with long-term antipsychotic therapy essential for managing these conditions7,10. A meta-analysis of 35 observational studies revealed that 56% of patients with schizophrenia and 44% of those with bipolar disorder exhibited non-adherence to their psychotropic medications11. The studies included in the analysis assessed medication non-adherence using various scales and terminology, such as noncompliance, non-persistence, dropout, and discontinuation11. In China, the National Continuing Management and Intervention Program for Psychoses (known as the 686 Program) was launched in 2004 to provide free medication and integrate mental health services into the national public health system12,13. Despite the program’s efforts, about 50% of patients fail to regularly take their medications14. Non-adherence is the leading cause of poor treatment outcomes15, including higher relapse rates, increased hospital admissions, suicide attempts, and increased mortality16. These issues put significant strain on healthcare systems17.

Managing medication adherence in the maintenance phase of SMD treatment remains a major clinical challenge. There is currently no gold standard for measuring adherence, since no measure can directly confirm medication ingestion. One possible control method could have been therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of the antipsychotic at follow-up visits. However, this approach remains biased by both the white coat effect and the Hawthorne effect18. Traditional methods, such as blood concentration tests, medication diaries, and self-reports, are often inconvenient, costly, and lack real-time accuracy19,20. The most common reason for non-adherence among patients with SMD was forgetting to take their medication21. Additionally, caregivers face substantial burdens, with an average of 32 h per week spent on patient care22, often without effective supervision of medication adherence. Given the widespread use of smartphones, they offer a practical, accessible platform for interventions that can be delivered anytime and anywhere23. Research indicates that individuals with psychiatric disorders use smartphones similarly to the general population, highlighting the potential for mobile devices to enhance mental health services24.

Recent innovations in digital tools, such as electronic diaries25, mobile apps26,27,28,29, and digital medication monitors (which typically refer to a smart pill container capable of cueing the taking of medication, record the instances of medication intake, and promptly alert caregivers or healthcare workers of failures to take medication as prescribed)30,31, have been explored to improve adherence. However, systematic reviews have reported mixed results20,32. For example, Dameery et al. demonstrated that a medication reminder app significantly improved medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia26. Additionally, an app-based digital intervention offering adherence incentives showed positive outcomes for medication compliance in patients with SMD29. However, both studies had small sample sizes and employed single-arm designs, limiting the generalizability of their findings. A study conducted in the USA involving 142 patients with SMD at a community mental health center found that digital medication monitors significantly improved adherence compared to usual care30. In contrast, a one-month pilot study in France, involving 33 outpatients at high risk for relapse, using digital medication monitors, showed no improvement in adherence among patients with schizophrenia33. Despite these efforts, there remains a gap in validation studies examining the integration of apps and electronic monitors to improve adherence.

To address these issues, we developed a digital medication system to improve adherence among patients with SMD. The system includes a digital medication monitor that provides audio reminders, records medication doses in real-time, and uploads data to a mobile app accessible by caregivers and healthcare workers. This technology aims to engage patients, caregivers, and the community, offering a scalable solution to enhance medication adherence. A cluster-randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Beijing, China, was conducted to evaluate its effectiveness, hypothesizing that the combination of this system with usual treatment would lead to greater improvements in adherence compared to an online medication diary over 12 months. This is the first RCT to evaluate the impact of a digital medication monitoring system, integrating both a medication monitor and mobile app, on medication adherence in community-dwelling patients with SMD.

Results

Descriptive statistics

This study included 30 communities from four districts in Beijing, which were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (15 communities, 108 patients) or the control group (15 communities, 108 patients). A total of 216 patients with SMD were recruited between September 2, 2022, and January 12, 2023, from the districts of Haidian, Xicheng, Tongzhou, and Pinggu. Following randomization, six participants from the intervention group and four from the control group did not complete the study (Fig. 1).

Flowchart depicting the progression of study participants through the trial, from recruitment and randomization to outcome measurement and analysis. This study was conducted across 30 communities in four districts of Beijing: Xicheng (urban core), Haidian (urban-rural fringe and high-tech development zone), Tongzhou (suburban), and Pinggu (rural, primarily agricultural, with a low population density). Recruitment dates were as follows: Haidian from September 5 to October 13, 2022; Xicheng from September 2 to October 19, 2022; Tongzhou from September 14 to October 25, 2022; and Pinggu from September 9, 2022, to January 12, 2023. Among the 216 patients included in this study, there was indeed one case of hospitalization. This case is in the control group, where the participant is noted as being unwilling to continue participating in the study.

As summarized in Table 1, the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants were similar across both groups, with the exception of age. More than half of the participants were female (58.33%). The median age was 52.25 years (IQR: 42.61–58.74), and 60.65% (131/216) had at least a junior high school education. The median age of onset was 24 years (IQR: 20–33). Of the participants, 69 (31.94%) were experiencing their first episode, and 183 (84.72%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Throughout the study, atypical antipsychotics were the most frequently prescribed, with risperidone, clozapine, and aripiprazole being the most commonly used (Supplementary Table 1).

Effect of digital medication system on primary outcome measures

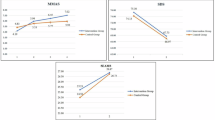

For the primary outcome, medication adherence was significantly higher in the intervention group at 12 months (84/108 vs. 23/108). The adjusted risk difference was 52.34 percentage points (95% CI: 34.65–70.03; P < 0.0001), and the adjusted risk ratio was 2.76 (95% CI: 1.52–5.03; P = 0.0009). Similar results were observed at other time points (Fig. 2a). The crude risk difference was comparable to the adjusted risk difference (Supplementary Table 2). Intervention Effects on Primary Outcome Across Visits Stratified by Polytherapy vs. Monotherapy support the effectiveness of the intervention regardless of the patients’ treatment regimen (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Sensitivity analyses using the per-protocol dataset showed minimal variation from the complete case analysis (Supplementary Table 5).

This figure compares primary and secondary outcomes between the intervention and control groups across five visits: baseline, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. a The primary outcome, self-reported medication adherence, is presented for each visit, with the intervention group represented by red bars and the control group by blue bars. b compares adherence rates between the groups based on the digital medication monitor. c and d show changes in the Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) and Fatigue and Behavioral Symptoms (FBS) scores, respectively, over the 12-month period. The red dashed line represents the intervention group, while the blue solid line represents the control group. Significant differences between groups are indicated by asterisks (*). Error bars in (b), (c) and (d) indicate the standard error. MARS Medication Adherence Rating Scale, FBS Fatigue and Behavioral Symptoms.

Effect of digital medication system on secondary outcome measures

For the secondary outcome, the system-monitored medication adherence ratio was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group across multiple visits (F = 4.08, P = 0.0026) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 6). At 12 months, the intervention group exhibited a significantly higher medication adherence rate (39.11% vs. 5.52%), with a least-squares mean difference of 33.60% (95% CI: 24.68–42.51; P < 0.001).

The improvement in MARS scores over the visits was significantly greater in the intervention group (F = 44.69, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 7). At month 12, the least-squares mean MARS score for the intervention group was 7.68 (se = 0.23), significantly higher than the control group’s score of 4.47 (se = 0.20). The between-group difference was 3.11 (se = 0.27), with a 95% CI of 2.59–3.64 (P < 0.001). Similarly, FBS scores in the intervention group were significantly lower than those in the control group at all visits (F = 20.29, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 8). At month 12, the least-squares mean FBS score for the intervention group was 13.25 (se = 0.73), significantly lower than the control group’s score of 19.26 (se = 0.85). The between-group difference was −6.01 (se = 1.00), with a 95% CI of −7.98 to −4.03 (P < 0.001).

Feasibility of a digital medication system

Feasibility scores across different dimensions and roles showed a consistent upward trend over time. At month 3, the average score was approximately 6, with healthcare workers rating acceptability, likelihood of recommendation, and satisfaction at 6.73, 6.43, and 6.61, respectively (Fig. 3a). By month 6, average scores had increased, with acceptability, likelihood of recommendation, and satisfaction for caregivers reaching 7.12, 6.61, and 7.18, respectively (Fig. 3b). At month 12, scores continued to rise, exceeding 7 and approaching 8, with patients reporting acceptability, likelihood of recommendation, and satisfaction at 7.67, 7.12, and 7.71, respectively (Fig. 3c). No serious adverse events were reported during the trial. However, the control group experienced one suicide attempt.

This figure presents the feasibility scores of the digital medication system, as reported by health workers (a), caregivers (b), and patients (c) in the intervention group, measured at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. Each evaluation criterion is represented by a distinct color: blue for acceptability of the intervention, red for the likelihood of recommending the intervention, and green for satisfaction with the intervention’s performance. Data for each visit are represented by bars, with the y-axis indicating the feasibility score (range: 0–10).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first RCT evaluating a digital medication system that combines a medication monitor and a mobile app to improve adherence among community-dwelling patients with SMD. The system includes medication storage and voice reminders, and through the integrated app, provides real-time notifications to caregivers and healthcare workers. The study followed the Medical Research Council’s guidelines for evaluating complex interventions34. Feasibility assessments, including acceptability, likelihood of recommendation, and overall satisfaction, were collected from multiple stakeholders. A combination of objective data from the digital medication monitors and patient-reported data was used to evaluate medication adherence. A pragmatic approach was employed, testing both the intervention and its implementation strategy. The study ensured feasibility by integrating the intervention into the established roles of existing healthcare providers. The study settings and patient populations were highly representative. The four districts of Beijing, each representing different levels of economic development, contributed to the broader applicability and generalizability of our findings. Additionally, the participants had diverse demographic and clinical characteristics, including varying levels of education, employment status, marital status, illness episodes, and duration, further enhancing the generalizability of the results. The need for patient-centered digital adherence technologies is particularly urgent in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where non-specialist healthcare workers can benefit from cost-effective solutions. The findings of this trial may provide valuable insights for LMICs facing similar resource constraints. The results demonstrated that the digital medication system significantly improved adherence across multiple measures and reduced family burden. Additionally, the system was well-received by users, with satisfaction steadily increasing over time. Overall, these findings suggest substantial benefits for both patient care and public health.

Our findings align with previous studies that have utilized digital technologies to improve medication adherence in patients with SMD. For example, SMS-based interventions have been employed in six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to enhance medication adherence in this population13,33,35,36,37,38,39,40. A stepped-wedge design trial conducted across nine rural townships in Hunan Province, China, involving 277 community-dwelling schizophrenia patients, showed improved adherence over a six-month follow-up period39,40. In addition to SMS-based interventions, several studies have explored the use of mobile apps to improve medication adherence, though many have been limited to single-group designs or small pilot RCTs20. Four single-arm trials have demonstrated that mobile apps can effectively enhance adherence in patients with SMD26,29,41,42. For example, a time series study conducted in Oman recruited 51 patients with schizophrenia and/or schizoaffective disorder from tertiary hospitals. The participants used a mobile phone app and were followed for 3 months, during which medication adherence significantly improved26. In addition, a study enrolled 33 patients with schizophrenia who used a smartphone intervention for 1 month to receive automated, real-time illness management support. This study demonstrated the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the intervention41. Furthermore, an RCT conducted in China involving 84 discharged patients with schizophrenia used WeChat reminders over a six-month follow-up period to improve antipsychotic adherence. The study reported significant improvements in medication adherence among participants27.

Additionally, three previous studies utilized digital medication monitors to measure or improve medication adherence in patients with SMD30,31,43. One RCT compared in-person and electronic monitoring to enhance adherence to oral medications in schizophrenia. In this study, 142 patients receiving medication maintenance at a community mental health center in Texas were randomized into one of three treatment groups for 9 months: (1) the PharmCAT group, which involved weekly home visits from a therapist; (2) the Med-eMonitor group, where an electronic medication monitor promoted medication use, recorded complaints, and provided feedback on adherence; and (3) Treatment as usual. While all patients received the Med-eMonitor device to track medication adherence, the device was only programmed for intervention in the Med-eMonitor group. The results indicated that the electronic monitor significantly improved medication adherence30. In two additional studies, an electronic monitor was used primarily as an objective measure of medication adherence to assess the effectiveness of the intervention, rather than as the intervention itself. For instance, one study examined the impact of providing electronically monitored antipsychotic medication adherence data to prescribers for 23 outpatients with schizophrenia43. Another pilot randomized trial evaluated a brief motivational intervention designed to improve medication adherence in 43 adolescents with bipolar disorder, where the electronic monitor was used to measure adherence and assess the intervention’s effectiveness31. These studies, primarily based on clinic-based populations, underscored the need for further research and the dissemination of evidence-based strategies for medication adherence assessment and intervention.

Unlike these prior studies, our trial incorporated a comprehensive system that combined a digital medication monitor with a supporting mobile application and evaluated adherence through multiple methods. Regarding the mechanisms of action, forgetting to take medication is the most common reason for non-adherence among patients with SMD21. The digital medication system likely improves adherence by providing timely reminders to patients. Equally important, we suspect that the system’s real-time feedback to caregivers about patients’ medication status played a critical role in its relative superiority during long-term implementation. By equipping families with timely information and actionable cues, the system enabled more proactive and effective supervision of medication adherence, thereby enhancing overall treatment adherence. Another important consideration in this study is the difference in user experience between the apps used by the intervention and control groups. Previous research indicated that patient engagement with mobile health apps can be influenced by their usability and visualizations44. In this study, although both groups used the same app, the enhanced user interface in the intervention app could have facilitated a more positive user experience, leading to better understanding, greater comfort, and ultimately higher adherence. It is also important to note that, at the final follow-up, we observed a decline in system-monitored adherence, which could be attributed to several factors, including the six-month gap between follow-ups13,40, disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. A more significant factor may be the stable adherence rates reported by healthcare workers and the MARS scores. These findings suggest that, over time, some patients may have developed stable adherence habits, reducing their reliance on the digital system for medication management. In the context of community-based management, patients with SMD can generally maintain a stable condition with consistent medication adherence. However, it is acknowledged that some patients may experience symptom fluctuations or relapse, often triggered by life events or irregular medication intake. For these patients, the majority are able to continue treatment at home through community-based care, with only a small proportion requiring hospitalization. Among the patients included in this study, there was one case of hospitalization, after which the participant withdrew from the study. This situation helps prevent potential bias in adherence measurement that could arise due to hospitalization.

Several limitations must be acknowledged in this trial. First, blinding of patients and healthcare workers was not feasible due to the study’s operational design, although the statistician remained blinded to group allocation. This may have introduced potential bias. Second, the digital medication system served as a proxy measure for medication adherence and did not directly confirm medication ingestion. Although video documentation could have provided an objective means of verification, its use was impractical due to the cognitive and functional challenges faced by patients with SMD. Additionally, the primary outcomes relied on self-reported data, which are inherently susceptible to biases and may affect the objectivity of the results. Further research is necessary to develop more objective and feasible methods for assessing medication adherence in this patient population. Moreover, the assessment of symptom severity was not included throughout the study. This study was conducted within a community-based care and management framework, and we enrolled patients who were in the stable phase of their condition at the time of inclusion. Although symptom severity assessment using structured rating scales was not the focus of this research, it can indeed enhance the precision of symptom evaluation and add clarity to the study. In addition, medication adherence at the time of initial diagnosis plays a critical role in determining prognosis. Therefore, future studies are warranted to assess adherence and the impact of interventions on symptom severity in patients with first-onset schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, in order to generate more comprehensive evidence. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings.

This trial shows that the digital medication system can significantly improve adherence among community patients with SMD. Based on these findings, we aim to engage policymakers to integrate the system into the 686 Program. In regions with mobile connectivity, adapting this system can play a crucial role in achieving the WHO’s vision of integrated mental health and social care services, as outlined in the Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a community-based, parallel-arm, cluster-randomized controlled trial in Beijing, spanning 30 communities, with recruitment taking place at six community healthcare centers. Participants were recruited between September 2, 2022, and January 12, 2023. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anding Hospital, affiliated with Capital Medical University (reference number 202261FS-2), and all participants and their guardians provided written informed consent. The trial was registered on the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry(chictr.org.cn) on May 29, 2022 (ChiCTR-ICR-2200060359) and followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan (Supplementary materials) are provided. The intervention was developed based on implementation science principles45 and eHealth behavioral theory46, with a particular emphasis on the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology.

Participants

The key inclusion criteria were as follows: patients aged 18–65 years, of any gender, who were in the stable phase of their condition, diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in accordance with ICD-10 criteria, and receiving community-based care. Participants were required to be either on intermittent medication or have refused treatment. Additionally, patients and their family members should possess a smartphone and demonstrate proficiency in its use. Exclusion criteria included individuals with a history of substance dependence or acute intoxication, as well as those assessed by the researcher to have a high risk of suicide. Psychiatrists at the community healthcare centers were responsible for patient recruitment.

In this study, 359 patients receiving oral antipsychotic treatment, either on intermittent medication or refusing treatment, were approached and screened. Of these, 137 patients declined to participate. An additional 6 patients were excluded for the following reasons: 5 were unable to use smartphones proficiently, and 1 was over 65 years old. As a result, 216 patients were successfully enrolled, yielding a response rate of 60.17%.

Randomization and masking

Randomization was performed using the PLAN procedure in SAS 9.4 by a statistician who was not involved in the trial. The randomization schedule employed randomly permuted blocks to assign communities to either the intervention or control group in a 1:1 ratio. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of patients, caregivers, and healthcare workers to treatment allocation was not feasible. However, a secondary unblinding was conducted for the statistician performing the analysis.

Interventions

Patients enrolled in the 686 Program are required to visit community healthcare centers monthly to collect free antipsychotic medications, with support from healthcare workers who serve as treatment supervisors. In this trial, patients in the intervention group received a digital medication system combining a digital medication monitor and a companion mobile app. The monitor stored medications and issued preset voice alerts to remind patients to take their medication. It recorded each instance of opening, transmitted this data to a cloud server for remote monitoring by healthcare workers and caregivers. If a patient missed a scheduled dose, the system sent reminders to both the caregiver and healthcare worker via the app (Fig. 4). Patients in the control group received standard care with the same app for adherence tracking via an online medication diary, but without the digital medication monitor or caregiver support.

This figure illustrates the workflow of a digital medication system designed for patients with severe mental disorders. The system consists of a medication monitor and a mobile application, operating based on a predetermined schedule for medication administration. Icons in this figure were generated from the open-access web-based software (ICONFONT, https://www.iconfont.cn).

For patients in the experimental group, the app provides several key features. The medication reminder module allows patients to view details of the medications they need to take, including types, dosages, frequencies, and times. The medication record module enables patients to track their medication adherence history. In the function square module, patients can complete scales pushed by healthcare workers, and view medication reminder messages from both healthcare workers and caregivers. The personal center module allows them to adjust the app’s notification settings (e.g., the sound, display style), submit feedback, and update the app. The patients in the control group had access only to the online medication diary module, where they provided feedback on their medication adherence and completed scale assessments.

For caregivers, the app offers three primary functionalities: (1) viewing the patient’s medication information, including types, dosages, frequencies, times, and real-time medication adherence; (2) accessing the patient’s overall medication history; (3) viewing assessment scales and messages sent by health workers.

For health workers, the app includes several administrative functions. The patient management module allows doctors to manage their patient list, search for patients, add new patients, and view and modify patient information. The medication management module enables doctors to set and review medication requirements for each patient, including types, dosages, frequencies, and times, and to monitor the patient’s medication history. The scale management module allows doctors to send assessment scales to patients and caregivers and review the completed results. The message management module enables doctors to send reminders or follow-up messages to patients, ensuring adherence to the prescribed medication regimen.

These tailored functions ensure that each user type has access to the relevant tools and information necessary for efficient management of medication adherence and overall treatment.

Prior to the trial, healthcare workers were trained on using the monitor and app, followed by training for patients and caregivers. Participants registered their information and logged into the app using passwords. Both groups were assessed for adherence at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. At 3, 6, and 12 months, acceptability evaluations were conducted for the intervention group.

Before the main study, a pilot trial was conducted. We recruited five patients with poor medication adherence (three diagnosed with schizophrenia and two with bipolar disorder) through convenience sampling from the Qinglongqiao Community in Haidian District. The pilot trial took place from June 27, 2022, to July 27, 2022, with recruitment occurring on June 27, 2022. Participants were followed for one month to identify and address any barriers to patient and family cooperation. Based on feedback from doctors, healthcare workers, patients, and family members, several modifications were made, including improvements to data storage, updates to the app interface, and optimization of reminders.

Assessments and outcomes

The primary outcome was a binary variable indicating whether poor adherence to antipsychotic treatment occurred at the 12-month visit. Poor adherence was defined as missing more than 20% of the prescribed doses in the past month (i.e., six or more daily doses in a month). Medication adherence was primarily assessed through patient self-report.

Several secondary outcomes were also recorded. First, data from the digital medication monitor was collected. For the intervention group, adherence was calculated as the ratio of actual medication retrievals from the monitor to the planned schedule, using data from the cloud-based server. For the control group, adherence was calculated as the ratio of medication doses recorded by the online medication diary to the planned doses. Second, medication adherence behaviors and attitudes were assessed at different visits using the Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS), with higher scores indicating better adherence47. Third, family burden was measured using the Family Burden Scale (FBS), with higher scores indicating a greater burden on the family48.

Except for primary and secondary outcomes, the feasibility of the digital medication system was evaluated. Healthcare workers, patients, and caregivers in the intervention group rated the digital medication system’s feasibility using a visual analog scale (VAS) from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating better feasibility.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was determined based on a cluster-randomized controlled design and the primary outcome. Based on previous studies, after 12 months of intervention, the rate of poor medication adherence would be 60% for patients using medication diary cards and 40% for those using the digital medication system49. The sample size was calculated using PASS 2021, with a two-sided alpha of 0.05, power of 0.80, an intra-cluster correlation coefficient of 0.001, and an attrition rate of 20%. We estimated that 108 patients per group, with an average cluster size of 6 patients across 15 communities, would be needed to detect the expected differences. Therefore, the total sample size required was 216 participants.

Data analysis followed a pre-specified plan in accordance with CONSORT guidelines. Primary analyses were performed on an intent-to-treat basis, including all randomized patients. For the primary outcome, missing data were handled using a worst-case imputation scenario, assuming that all missing visits in the control group had a favorable outcome and those in the intervention group had a poor outcome50,51. Descriptive statistics were reported as medians (interquartile range, IQR) for continuous variables and counts (percentages) for categorical variables.

For binary outcomes, both absolute and relative measures of effect were reported, as per CONSORT guidelines52. The primary outcome was analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) to account for clustering within patients, nested within communities. A binomial distribution with an identity link was used to estimate the risk difference (RD) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values. Log-binomial GEE regression was also employed to calculate relative risk (RR), 95% CIs, and p-values53. The exchangeable covariance structure was used to model the correlation of responses from the same patients, and differences between study groups at each time point were estimated using GEEs.

In adjusted analyses of the primary outcome, we included age, sex, and diagnosis (schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) as covariates. Per-protocol sensitivity analyses were also performed, including data from 102 participants in the intervention group and 104 in the control group who completed all visits.

For secondary outcomes, missing data were not imputed. Longitudinal data for continuous outcomes were analyzed using generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) that accounted for clustering at both the patient and community levels. Standard errors were adjusted empirically, and an autoregressive correlation structure was applied to the repeated measures. These models were used to analyze secondary outcomes, including the medication adherence ratio monitored by the system, MARS scores, and FBS scores. Fixed effects for intervention group, visit, and their interaction (group × visit) were included, with covariates adjusted similarly to the GEEs. Due to significant baseline differences in MARS scores between groups, baseline MARS scores were included as covariates in the GLMM for MARS.

The feasibility of the digital medication system was assessed independently from the secondary outcomes, and descriptive statistics were provided for the feasibility scores, which were not analyzed using GLMMs.

All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (version 4.3.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P-values were two-sided, with significance set at P < 0.05.

Data availability

De-identified participant data on which this manuscript is based will be made available, following publication, upon reasonable request to yanfang2019@ccmu.edu.cn, and after a signed data access agreement with the principal investigator.

Code availability

Data analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (version 4.3.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The coding strategy is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Fang Yan, at yanfang2019@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Mental Health Inf. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness (2024).

Baker, A. L., Forbes, E., Pohlman, S. & McCarter, K. Behavioral interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk among people with severe mental disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 18, 99–124 (2022).

Pisanu, C. et al. Dissecting the genetic overlap between severe mental disorders and markers of cellular aging: identification of pleiotropic genes and druggable targets. Neuropsychopharmacology 49, 1033–1041 (2024).

Victoria Institute of Strategic Economic Studies. The Economic Cost of Serious Mental Illness and Comorbidities in Australia and New Zealand (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; Australian Health Policy Collaboration, Melbourne, 2016).

WHO. Schizophrenia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia#:~:text=Schizophrenia%20affects%20approximately%2024%20million%20people%20or%201,not%20as%20common%20as%20many%20other%20mental%20disorders (World Health Organization, 2024).

WHO. Mental Health Systems in Selected Low- and Middle-Income Countries: a WHO-AIMS Cross-National Analysis. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44151/9789241547741_eng.pdf?sequence=1 (2009).

Roberts, N. L., Mountjoy-Venning, W. C., Anjomshoa, M., Banoub, J. A. M. & Yasin, Y. J. GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study (vol 392, pg 1789, 2018). Lancet 393, E44–E44 (2019).

McGrath, J. J. et al. Age of onset and cumulative risk of mental disorders: a cross-national analysis of population surveys from 29 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 10, 668–681 (2023).

Yee, C. S., Hawken, E. R., Baldessarini, R. J. & Vázquez, G. H. Maintenance pharmacological treatment of juvenile bipolar disorder: review and meta-analyses. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 22, 531–540 (2019).

De Las Cuevas, C. et al. Poor adherence to oral psychiatric medication in adults with schizophrenia may be influenced by pharmacophobia, high internal health locus of control and treatment duration. Neuropsychopharmacol. Hung. 23, 388–404 (2021).

Semahegn, A. et al. Psychotropic medication non-adherence and its associated factors among patients with major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-1274-3 (2020).

Good, B. J. & Good, M. J. Significance of the 686 Program for China and for global mental health. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 24, 175–177 (2012).

Cai, Y. et al. Residual effect of texting to promote medication adherence for villagers with schizophrenia in China: 18-month follow-up survey after the randomized controlled trial discontinuation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 10, e33628 (2022).

Zhao, M. et al. Community-based management and treatment services for psychosis - China, 2019. China CDC Wkly 2, 791–796 (2020).

Samalin, L. & Belzeaux, R. Why does non-adherence to treatment remain a leading cause of relapse in patients with bipolar disorder?. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 73, 16–18 (2023).

Warriach, Z. I., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M. A. & Ferrer, G. F. Suicidal behavior and medication adherence in schizophrenic patients. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.12473 (2021).

De Las Cuevas, C. et al. Poor adherence to oral psychiatric medication in adults with bipolar disorder: the psychiatrist may have more influence than in other severe mental illnesses. Neuropsychopharmacol. Hung. 23, 347–362 (2021).

Acosta, F. J. et al. Antipsychotic treatment dosing profile in patients with schizophrenia evaluated with electronic monitoring (MEMS®). Schizophr. Res. 146, 196–200 (2013).

Fowler, J. C. et al. Hummingbird study: results from an exploratory trial assessing the performance and acceptance of a digital medicine system in adults with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or first-episode psychosis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 17, 483–492 (2021).

Wu, T. et al. Digital health interventions to improve adherence to oral antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia: a scoping review. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-071984 (2023).

Stentzel, U. et al. Predictors of medication adherence among patients with severe psychiatric disorders: findings from the baseline assessment of a randomized controlled trial (Tecla). BMC Psychiatry 18, 155 (2018).

Forma, F., Chiu, K., Shafrin, J., Boskovic, D. H. & Veeranki, S. P. Are caregivers ready for digital? Caregiver preferences for health technology tools to monitor medication adherence among patients with serious mental illness. Digital Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221084472 (2022).

Pennou, A., Lecomte, T., Potvin, S. & Khazaal, Y. Mobile intervention for individuals with psychosis, dual disorders, and their common comorbidities: a literature review. Front. Psychiatry 10, 302 (2019).

Ben-Zeev, D., Davis, K. E., Kaiser, S., Krzsos, I. & Drake, R. E. Mobile technologies among people with serious mental illness: opportunities for future services. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 40, 340–343 (2013).

Mutschler, J., von Zitzewitz, F., Rössler, W. & Grosshans, M. Application of electronic diaries in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. Psychiatr. Danub 24, 206–210 (2012).

Al Dameery, K. et al. Enhancing medication adherence among patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: mobile app intervention study. SAGE Open Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608231197269 (2023).

Zhu, X. et al. A mobile health application-based strategy for enhancing adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 34, 472–480 (2020).

Kidd, S. A. et al. Feasibility and outcomes of a multi-function mobile health approach for the schizophrenia spectrum: App4Independence (A4i). PLoS ONE 14, e0219491 (2019).

Guinart, D., Sobolev, M., Patil, B., Walsh, M. & Kane, J. M. A Digital intervention using daily financial incentives to increase medication adherence in severe mental illness: single-arm longitudinal pilot study. JMIR Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.2196/37184 (2022).

Velligan, D. et al. A randomized trial comparing in person and electronic interventions for improving adherence to oral medications in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 39, 999–1007 (2012).

Goldstein, T. R. et al. A brief motivational intervention for enhancing medication adherence for adolescents with bipolar disorder: a pilot randomized trial. J. Affect. Disord. 265, 1–9 (2020).

Basit, S. A., Mathews, N. & Kunik, M. E. Telemedicine interventions for medication adherence in mental illness: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 62, 28–36 (2020).

Tessier, A. et al. Brief interventions for improving adherence in schizophrenia: A pilot study using electronic medication event monitoring. Psychiatry Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112780 (2020).

Skivington, K. et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 374, n2061 (2021).

Cullen, B. A. et al. Clinical outcomes from the texting for relapse prevention (T4RP) in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder study. Psychiatry Res. 292, 113346 (2020).

Rohricht, F., Padmanabhan, R., Binfield, P., Mavji, D. & Barlow, S. Simple mobile technology health management tool for people with severe mental illness: a randomised controlled feasibility trial. BMC Psychiatry 21, 357 (2021).

Valimaki, M., Kannisto, K. A., Vahlberg, T., Hatonen, H. & Adams, C. E. Short text messages to encourage adherence to medication and follow-up for people with psychosis (Mobile.Net): randomized controlled trial in Finland. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e245 (2017).

Sibeko, G. et al. Improving adherence in mental health service users with severe mental illness in South Africa: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a treatment partner and text message intervention vs. treatment as usual. BMC Res. Notes 10, 584 (2017).

Cai, Y. et al. Mobile texting and lay health supporters to improve schizophrenia care in a resource-poor community in rural China (LEAN Trial): randomized controlled trial extended implementation. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e22631 (2020).

Xu, D. R. et al. Lay health supporters aided by mobile text messaging to improve adherence, symptoms, and functioning among people with schizophrenia in a resource-poor community in rural China (LEAN): a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 16, e1002785 (2019).

Ben-Zeev, D. et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a smartphone intervention for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 1244–1253 (2014).

Moitra, E., Park, H. S. & Gaudiano, B. A. Development and initial testing of an mhealth transitions of care intervention for adults with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders immediately following a psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatr. Q. 92, 259–272 (2021).

Nakonezny, P. A., Byerly, M. J. & Pradhan, A. The effect of providing patient-specific electronically monitored antipsychotic medication adherence results on the treatment planning of prescribers of outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 208, 9–14 (2013).

Grundy, Q. A review of the quality and impact of mobile health apps. Annu. Rev. Public Health 43, 117–134 (2022).

Bauer, M. S. & Kirchner, J. Implementation science: what is it and why should I care?. Psychiatry Res. 283, 112376 (2020).

Klonoff, D. C. Behavioral theory: the missing ingredient for digital health tools to change behavior and increase adherence. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 13, 276–281 (2019).

Thompson, K., Kulkarni, J. & Sergejew, A. A. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr. Res. 42, 241–247 (2000).

Pai, S. & Kapur, R. L. The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: development of an interview schedule. Br. J. Psychiatry 138, 332–335 (1981).

Patel, V. et al. Lay health supporters aided by mobile text messaging to improve adherence, symptoms, and functioning among people with schizophrenia in a resource-poor community in rural China (LEAN): a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002785 (2019).

Rombach, I., Knight, R., Peckham, N., Stokes, J. R. & Cook, J. A. Current practice in analysing and reporting binary outcome data-a review of randomised controlled trial reports. BMC Med. 18, 147 (2020).

Cebula, M. et al. Resin infiltration of non-cavitated proximal caries lesions in primary and permanent teeth: a systematic review and scenario analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020727 (2023).

Pereira Macedo, J. A., Giraudeau, B. & Escient, C. Estimating an adjusted risk difference in a cluster randomized trial with individual-level analyses. Stat. Methods Med. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/09622802241293783 (2024).

Naimi, A. I. & Whitcomb, B. W. Estimating risk ratios and risk differences using regression. Am. J. Epidemiol. 189, 508–510 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (BMSTC; Grant No. Z211100002921038) and the Beijing Municipal Health Commission (BMHC; High-Level Public Health Technical Talent Training Program—Discipline Leader-01-30). The authors express their gratitude to the patients and their caregivers for their participation and consent. We also thank the healthcare workers at Beijing Haidian Psychological Rehabilitation Hospital, Xicheng District Pingan Hospital, Beijing Tongzhou District Psychiatric Hospital, and Beijing Pinggu District Psychiatric Hospital for their invaluable support in conducting the study and collecting data. During the preparation of this work, we used ChatGPT to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool, we reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. led statistical planning, formal analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. Q.Z. supervised study conduct, data collection, coordination, acquisition, and interpretation. H.Q. contributed to protocol development and data management. C.D., Z.Y., W.L., C.X., X.J., and J.S. supported the field implementation of the trial. L.F. contributed to protocol development and delivered intervention training. H.W. contributed to protocol development and offered guidance on data analysis. F.Y. secured funding, conceptualized and designed the study, and critically revised the manuscript. G.W. contributed to study design, conceptualization, and manuscript review. Y.F. conceptualized and designed the study, participated in study conduct, data coordination, and manuscript review. All authors had full access to the study data, reviewed the draft, approved the final version, and accepted final responsibility for submitting the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, J., Zhai, Q., Qi, H. et al. Randomized clinical trial of a digital medication system to enhance adherence in patients with severe mental disorders. npj Digit. Med. 8, 333 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01748-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01748-2