Abstract

Decentralized clinical trials (DCTs) have gained long-standing interest, yet their adoption as a new paradigm remains uncertain even with broader acceptance from regulatory and industry. This study aims to unveil its evolutional trend, which helps answer what the current development stage DCT is located at as well as the underlying reasons. While DCTs’ prime time has not arrived, we propose solutions to advance their sustainable implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

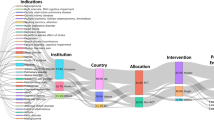

Decentralized clinical trials (DCTs) are defined as studies executed through processes and technologies that differ from the traditional clinical trial model, according to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Fig. 1). The collection of strategies conducted in DCTs, either in whole or in part, include but are not limited to, electronic consent, digital health technologies, telemedicine visits, home visits by nurses, and laboratory tests done in dispersed labs. The application of tools mentioned above was early in trials at the beginning of 2000s.The first fully virtual study should date back to Pfizer’s Research on Electronic Monitoring of Overactive Bladder Treatment (REMOTE) conducted in 20111.

Despite the promise of DCTs, the pharmaceutical industry was somewhat slow to adopt the technologies. Unexpectedly, the COVID-19 pandemic, rather than the advancement of either remote technologies or government regulation, finally catalyzed the expansion, bringing DCT into the clinical trial mainstream. The utilization of remote visit, drug delivery, and monitoring significantly increased amongst the DCT solutions to conquer constraints on traffic and accessibility without disruption of clinical trials. DCTs are highly praised as patient-centric in bringing in the convenience-quotient for the patients to make trials as accessible as possible and to give them the opportunity to participate from anywhere. In the interest of sponsors, DCTs present apparent advantages over traditional clinical trials in saving labors, time and cost2. Digital tools were believed to enable smaller sample size by precise assessment of clinical outcomes, as well as subsequent lower cost and less variability and inconsistence between sites3. Fully or partial virtual trials save employee training and expenses for sponsors. Patients may show improved compliance and willingness to participate in DCTs, which may achieve effects closer to real world4. The conveniences may transfer to expanded access to more representative patient populations and improved trial efficiencies. With supportive regulatory policies and wide acceptance by the industry, DCT has been transforming the digitalized clinical trials and claimed as the “new paradigm” of human clinical research directing into the future5.

However, a question is inevitably raised to reassess the merits of DCT strategies and their associated challenges in the post-epidemic era - how much has this supposedly “new” method of conducting clinical trials benefited the clinic and industry since its official emergence more than a decade ago? Despite of advantages above, challenges may also arise from drug shipment, requiring drug stability, security, and coordination between relevant state-specific laws or regulations. The accuracy and reliability of digital tools also need further validation, such as the wearable biometric devices. Data integrity, privacy, and currency are also sensitive concerns.

Herein we propose a hypothesis that DCTs have NOT stood to change the clinical trials in drug and therapeutic development as expected. A systemic analysis on DCTs was conducted to unveil the genuine tendency of technology penetration from the dimension of implementary mode, technology application level, and international comparison. We further tried to explain why it has not fully reformed clinical trials as expected reflecting on sophisticated factors impeding its development, including immature regulation, technological bottlenecks, and localization system limitations.

Landscape of DCTs during the last decade

A heuristic lookback of DCTs conducted during the last decade unveil the evolutional trend of its development. A total of 2830 trials were identified with decentralized attributes according to Citeline database by matching index of DCT elements in the study, including Electronic Consent, Home Visits, Personal Devices/Apps, Telemedicine/Telehealth, Unspecified Decentralized (DCT) Attribute, Wearables/Sensors, starting from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2023. The database (https://www.citeline.com) includes more than 70 country registries and over 90 other trial listings sources, as well as health authority websites and regulatory databases. After excluding items that not interferential, incomplete, not using drugs, and not involving key techniques, 1097 trials remained for final analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Of these, 741 (67.5%) were industry-initiated and 356 (32.5%) were academic-initiated. More than 70% were conducted at a single center (n = 796). Decentralized techniques served for primary endpoint estimation in 46.5% studies (n = 510), for secondary endpoint in 34.4% (n = 377), and for exploratory endpoint in 2.0% (n = 22). The academia favored to utilize new DCT technology in Phase IV studies (41.3%), while companies preferred to integrate in Phase III studies (40.4%). 72.5% of DCT trials were conducted post-market, emphasizing its limited role in pivotal studies and regulatory approval.

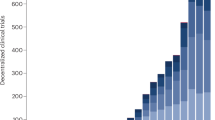

Studies with DCT attributes are on a decline

A slow but steady increasing trend of DCTs was witnessed from 2014 to 2019 (Fig. 2). Apparently, a significant burst was between 2019 and 2021 with around 50% increase in the decentralized initiations, during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a sharp decrease happened in 2022 both for the total number of DCT studies and its weight among the overall studies, almost dropped back to the DCT numbers prior to the pandemic. The miracle didn’t happen in 2023 either, when the number of DCTs further declined even back to seven years ago. According to declaration of World Health Organization, the pandemic started on March 11, 2020 and ended on May 5, 20236. Considering the lagging and conservative nature of declaration, we moved the end up to Jan 1, 2023. The application of decentralized attributes in clinical trials was significantly different during COVID-19, both compared with pre- pandemic (X2 = 40.73, p-value = 1.75 × 10−10), and post- pandemic (X2 = 19.46, p-value = 1.03 × 10−5), but not the case between pre- and post- pandemic (X2 = 1.01, p-value = 0.32), indicating that the pandemic had a significant impact on the development of decentralization.

The number of DCTs has shown a marked decline since 2021, a trend that remains significant after accounting for the general downturn in overall clinical trials. Dark red line: the number of DCTs. Bright red line: the number of DCTs among one thousand clinical trials of all kinds initiated in each year.

Nearly all (97.6%) studies were conducted in a hybrid model, where digital techniques were partially used in one or more segments through the trial. By contrast, full decentralized trials were conducted occasionally after 2019, when Roche initiated the model in a phase IV trial for influenza7. In such fully remote clinical trial, the patients do not need to travel to the study center at all. Notably, 4/8 of the full decentralized trials after that were for COVID-19, while the others were for psychiatric and heart diseases. The third DCT model is parallel, in which one group of patients in the clinical trial is conducted remotely, and one group is conducted in a traditional mode. 14 of the 17 parallel decentralized trials were conducted after the marketing of investigated products, and mainly of exploration on application of digital health technologies. The overall superficial application of DCT tools may fail to fundamentally change the course of a trial and can hardly measurably enhance the efficiency or quality of clinical trials.

DCT element incorporation is limited

To understand the implementation modes and DCT attributes utilized in the studies, five key elemental techniques were identified: (a) Remote patient recruitment (eRrecruitment) including remote screening and eQualification; (b) Electronic consent; (c) Direct-to-patient (DTP) drug delivery; (d) Remote data collection including patient experiential data collection, patient/clinical report outcomes (PRO/CRO), wearables, and remote monitoring; (e) Remote home visits including patient reminder and support (Supplementary Table 1). Remote data collection was applied in 1008 clinical trials (91.9%), followed by remote/residential visits (279, 25.4%); remote recruitment and direct-to-patient drug delivery were the least applied, with 45 (4.1%) and 78 (7.1%) respectively. All of the five elements but remote data acquisition peaked at 2020 and declined quickly afterwards, forecasting a decay of the overall DCTs from 2021 (Supplementary Fig. 2). We also examined the frequency of DCT element utilization in each trial, finding that 78.2% of the DCTs implemented only one element (n = 858).

As COVID-19 was one of the most critical events for the development of DCT, utilization of the five key elemental techniques exhibited slight differences along time periods (Fig. 3). The impact of COVID-19 is more obvious to industry, where implementation of eConsent, drug management, and remote visit were all significantly more engaged. For academic-initiated DCTs, only eConsent was more frequently used during the pandemic. Intriguingly, all decentralized key techniques but remote data acquisition were apparently less engaged after the pandemic in academic-initiated studies, but the trend was not seen in industry-initiated trials.

There was a significant difference between sponsors in selection of DCT elements. The industry mainly focused on remote data collection (692, 93.3%), followed by remote or residential visits (137, 18.5%), while remote recruitment, drug management, and eConsent accounted for only 2.4% (n = 18), 6.2% (n = 46) and 5.9% (n = 44), respectively. Academic-initiated DCTs, although with fewer number of trials, had more attempts especially at remote or residential visits (39.9% versus 18.4%), as well as eConsent (11.0% versus 6.2%), direct-to-patient (9.6% versus 5.9%), and remote recruitment (7.6% versus 2.4%, Supplementary Fig. 3). Overall, the academic community predominantly explored the elements in Phase IV clinical trials, whereas enterprises show a greater inclination towards utilizing them in Phase III studies. During the pandemic, the proportion of applying these elements in early-stage trials increased in the academic-initiated ones. This trend, conversely, manifested in industry-sponsored studies post-pandemic (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The utilization of decentralized elements has not demonstrated positive impacts on outcomes of DCTs. The study outcomes of 869 DCTs and 144,196 trials without decentralized attributes were available. Chi-square test showed that there is no significant difference between completion rate of trials using decentralized elements or not (X2 = 0.40, p-value = 0.53). The rate of trial completion was not higher in DCTs (82.4% vs. 83.3%), and proportions of trials terminated due to lack of funding or poor enrollment was not lower in DCTs (5.8% vs. 5.3%), indicating that the aim of cost reduction and efficacy improvement by means of decentralized element utilization was not realized (Fig. 4). It is important to emphasize that this constitutes an exploratory analysis derived from the database, necessitating a particularly cautious approach when interpreting the findings.

Unbalanced development among regions and therapeutic areas

Decentralized clinical trials were conducted in 108 countries on 5 continents, but only 27.4% of DCTs were multiregional clinical trials (MRCTs). The majority of studies were in Americas (n = 741, 67.5%), followed by Europe (n = 457, 41.7%). Since 2019, Europe has been decreasingly involved in DCTs, and its participation in DCTs decreased further in 2023, equaling Asia, which has seen a significant increase in that year (Supplementary Fig. 5). Africa had the fewest projects (n = 100, 9.1%) with a further declining trend. At the country level, the United States accounted for the majority (n = 673, 61.3%) of decentralized trials, followed by the United Kingdom (n = 238, 21.7%) and Canada (n = 216, 19.7%).

The distribution of DCT attributes also varied by therapeutic areas, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. Respiratory diseases were the most common type of indication, with 149 clinical studies (13.6%), followed by neurological diseases (n = 146, 13.3%), COVID-19 (n = 134, 12.2%), and psychiatric disorders (n = 92, 8.4%). Other top listed therapeutic areas include endocrine or metabolic diseases, infectious diseases, neoplasms, and circulatory disorders. We further examined the proportion of utilization of decentralized elements among the overall studies, finding that, as the largest indication of clinical trials, only 0.18% of oncology studies were decentralized, compared with 2.3% in COVID-19 and 0.63% in neurological diseases.

Risk-cost-benefit evaluation in decision-making on DCT utilization

To sum up, through a comprehensive analysis of decentralized element utilization in clinical trials, we found a less prospective and developed picture of DCTs as expected, with underutilization of decentralized elements, immature and unbalanced industrial acceptance, and shrinking development trend. The Prime time may have not arrived for this highly anticipated clinical research mode. We attribute underlying reasons for the unsustained growth of DCTs to two major aspects. First, subsequent to the pandemic, the impediments to traditional clinical trials no longer existed. The accessibility of medical services for patients has ceased to be a concern. Sponsors are no longer compelled to assume diverse risks in attempting approaches that have not been fully acknowledged. Secondly and more crucially, these approaches have not genuinely realized the objective of reduction and efficiency enhancement. On the contrary, they may increase the expenditures of certain remote systems and bring regulatory risks.

Declining demands post COVID-19 and limited application scenarios

Based on our analysis, a sharply decreasing trend was witnessed since 2021 of application of decentralized elements in clinical trials. We noted that 67.5% of DCTs are actually initiated by academics, where face-to-face communication and examination are clinical routine. The accessibility of traditional clinical trials, usually with intense on-site visit, made the adoption of DCTs significantly less necessary after the epidemic.

Except for COVID-19, decentralized elements are mainly applied to therapeutic areas including respiratory, neurological, psychiatric, and endocrine or metabolic disorders. These diseases usually require long-term follow-up and continuous monitoring, where digital health technologies (DHTs), such as continuous glucose monitoring, body movement recorders, and cough monitors, have already been maturely integrated into clinical research. However, other major therapeutic scenarios, such oncology, have seen scarce application of decentralized elements. Although stakeholders tend to believe that the emergence of DCTs is expected to simplify the trial process and significantly improve access to cancer treatment, there still exists a huge gap that how to make DCT technologies cost-controllable and practical, rather than icing on the cake.

Unrealized promised benefits in cost reduction and efficiency improvement

According to our analysis, the current DCT mode heavily relies on mixed utilization of traditional and decentralized elements, and 78.3% of DCTs used only single decentralized attribute in the trial. In such circumstances, cost reduction and efficiency gains can hardly be achieved. Although DCT can facilitate patients in aspects such as on-site visits, for enterprises, cost reduction and efficiency should be the main motivation for them to adopt DCT, which might also explain our observation that the academic is more favorable to decentralized attributes than the industry.

DCTs are supposed to bring advantages over traditional clinical trials based on the fact that the mean direct cost to conduct a clinical trial per day is approximately $40,0008. Therefore, faster patient enrollment and reduced trial delays will promisingly lead to enhanced risk assessments and lower capital investments. An academically economic model was established indicating that applying DCT methods results in nearly a five-fold return on investment (ROI) in phase II clinical trials, and a 13-fold ROI in phase III trials9. Additionally, a report published by service provider claimed significant reduction in timeline and patient screen failure rate10. However, the reduction in cost and increase in drug values seem retained on the model level and non-peer-reviewed report, without conceiving real-world evidence. On the opposite side, remote technologies themselves require start-up cost and time, which raises the bar for DCT application and may to some extent offset its potential benefits.

Potential solutions

For sponsors, we suggest to choose the appropriate indication to apply DCTs where decentralization could maximize its advantages. Besides chronic diseases, cancers and rare diseases are regarded as potential candidates. Treatment of tumors is often a long-term process, both for malignant tumors that require ongoing medication and for benign tumors that require long-term monitoring. While oncology clinical trials rely heavily on face-to-face communication and assessment for enrollment and evaluation, DCT holds the promise of helping to reduce manpower, lower lost time rates, and bring convenience to patients during the follow-up phase. Moreover, with the youthful onset of tumors and the prevalence of remote tools, this heavyweight area is likely to bring about significant changes in the DCT market. Since 2000, the percentage of approvals targeting rare and orphan diseases has grown from 11% to 58%11. The low incidence rate presents stages for implementation of DCT strategies such as remote recruitment, drug delivery, and data collection. The reformation will bring decreased costs to both patient and sponsor in saving travel burden and improving patient retention.

For service providers, technologies supporting decentralization needs to be improved to manage risk to fit in with regulatory requirements, so that full-mode DCT could be moved forward. The feasibility and practicability of DHTs should be ensured for consideration by both sponsors and clinicians. The key decentralization elements including remote consent, recruitment, and drug delivery are seldom applied, reflecting immature and unreliable technology for these elements to be included to support results of the clinical trials. Adequate site level training and resources should be provided to save time and avoid operational errors, even if longer start-up timelines. Insufficient staffing and additional workload is another tangible problems, greatly hindering the popularity of DCT in clinical trial sites. Although DCT has broadened options and improved the experience for patients, only the DCT tools appropriately implemented would DCT achieve sustainable development.

Practical and regulatory challenges

The potential possibility to get approval based on decentralized clinical trials is a major concern for enterprises. To our knowledge, there are currently no cases where data based on full-mode DCTs have received regulatory approval. In terms of implementation, our study indicated that over 70% of DCTs are single-center, which is contradictory to the tendency of growth in multiregional clinical trials (MRCTs), indicating that these attributes may not provide adequate values for dispersed multicenter studies as previously thought12.

Inter-regional discoordination influencing sponsors’ decision on whether decentralization should be applied may lie in multiple considerations. Firstly, regulatory policies vary between regions. National authorities in different countries realized the importance of data privacy, issuing policies either encouraging or impeding the cross-border data collection and sharing. For example, “Executive Order on Preventing Access to Americans’ Bulk Sensitive Personal Data and United States Government-Related Data by Countries of Concern” was issued by White House on February 28th13. Restricting data flow will bring obstacles to date integrity across nations and has become a major outstanding issue in the development of DCTs.

Secondly, with the shift in acceptance of decentralization and supportive policies during the pandemic, the industry providing DCT service portfolio was emerging with fast pace of innovation to meet the demands from enthusiastically ongoing studies. However, regulatory preferences are changing from time to time. In the aftermath of the epidemic, traditional clinical study execution is no longer impeded, and government regulators are taking a more cautious approach to normalizing the use of new technologies in DCTs. The service providers are required to present evidence supported by rigorous study designs and validity data, to get recognition from the regulators so that the new technologies could be further applied in clinical trials. Thus, quite a number of DCT technologies and trial designs are still in the development and validation phase, requiring time and cost to explore the most appropriate scenarios for their application.

Thirdly, investigators and clinical institutes may have different normal practices and trial-related management disciplines. For example, principal investigators should be majorly responsible for clinical trials in the United States and may directly benefit from the advantages brought by DHTs14. They become the main consideration for whether or not to adopt decentralization as executing end, to some extent, independent of hospitals. Instead, clinical trials in China are usually managed by a specific department affiliated with the hospital. The hospitals tend to be more hesitate in utilization of decentralized elements with increased management costs and difficulties but scarce real benefits. Moreover, heavy disease burden, narrow access to virtual tools such as smart mobile phones, as well as elderly society, may also influence the estimated efficiency of decentralized attributes in various regions.

Potential solutions

For DCT to become the new paradigm, its application to MRCT is a necessity. Tackling inter-regional varieties is a challenge for all stakeholders. For regulatory authorities, a fit-for-purpose and risk-based regulation pathway might help. We reviewed the regulatory paths for DHT among various regions (Supplementary Table 2). The functional design, data authenticity and validity, and participant privacy protection of DHTs are common major concerns. All the guiding principles unanimously focus on the verification and evaluation of DHT devices, especially on whether technical characteristics, design, and operation are fit-for-purpose. However, the description of regulatory processes is often neglected. Given that DHT is utilized in the trial process, in most regions, it remains ambiguous whether a distinct application for the technique must be filed or if it should be regulated in tandem with the drug clinical trial application. Thus, expediting the DHT’s regulatory categorization is of paramount urgency.

Presently, only the regulatory authorities of the United States and Malaysia have outlined the regulatory trajectories for DHT. Compared with Malaysia, where the decision on whether to conduct device-related research is entirely made by the regulatory authorities, the United States directly delegates the power to ethics committee for DHT with low risks, which not only substantially lightens the regulatory approval load but also empowers sponsors with the freedom to explore innovative tools. Moreover, to better accommodate the demands of new technologies, the United States has initiated the Drug Development Tool (DDT) Qualification Programs and the Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs (ISTAND) Pilot Program.

We suggest a risk-based evaluation system for the application and approval for DHT tools based on nature of the tools and technology parameters, as well as the existing regulatory system for device and technologies. A clearer regulation pathway will motivate the enthusiasm of sponsors and technology developers and promote acceptance of DHT data by regulatory agencies and the approval pathway. The regulatory authorities have made efforts on instructing data transmission and management in decentralized trials, including ICH E6 (R3) and guideline issued by FDA in September 202415,16. Data management primarily imposes objective requirements on DHT, requiring compliance with regulations and ordinances in each region for storing, analyzing, and sharing data. This should be established based on a clear understanding of latest regulations, and decisions can be made about where privacy protections should be in place, and what types of data can be shared without disrupting the normal course of a clinical trial, and even improving efficiencies.

Based on our analysis, the maturation and development of decentralized elements are unbalanced between regions. More than 70% of service providers are headquartered, and more than half of DCTs were conducted in North America. For decentralization to be truly comprehensive, development on decentralized elements should match the distribution of the overall number of clinical trials. Such mismatch is evident in Asia, especially in China, where research and development of decentralized element utilization should be encouraged.

We admit the limitations of this study. First, although results and protocols were read manually to compensate for incomplete information recorded in the database, no decentralized elements were reported in the protocols does not mean that new technology was not used in the actual implementation. Secondly, other digital health technologies, such as reimbursement, were not included in identification of DCT attributes in the database. Thirdly, there is no comparison between the clinical studies in which DCTs were conducted and traditional clinical research in general. This may provide a better understanding of the status of DCT implementation at a macro level. Finally, a quantitative analysis investigating the actual impact of DCT on subject retention, recruitment, and protocol bias needs to be further explored, limited by the accessible information.

Conclusion

Currently, DCT is mainly based on application of individual elements and mixed modes, exhibiting unbalanced development and declining trend. DCT may NOT have really empowered drug R&D as it was expected. Regulators, service providers, sponsors, and the clinical side need to work together to solve the pain points, improve and promote technical solutions, and map out the applicable scenarios of full-mode DCT in order to genuinely bring practical benefits and impetus to drug discovery and development.

Data availability

Data are available on reasonable request.

References

Orri, M., Lipset, C. H., Jacobs, B. P., Costello, A. J. & Cummings, S. R. Web-based trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tolterodine ER 4 mg in participants with overactive bladder: REMOTE trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 38, 190–197 (2014).

De Brouwer, W., Patel, C. J., Manrai, A. K., Rodriguez-Chavez, I. R. & Shah, N. R. Empowering clinical research in a decentralized world. NPJ Digit. Med. 4, 102 (2021).

Tanner, C. M. et al. The TOPAZ study: a home-based trial of zoledronic acid to prevent fractures in neurodegenerative Parkinsonism. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 7, 16 (2021).

Izem, R. et al. Decentralized clinical trials: scientific considerations through the lens of the estimand framework. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 58, 495–504 (2024).

Underhill, C. et al. Decentralized clinical trials as a new paradigm of trial delivery to improve equity of access. JAMA Oncol. 10, 526–530 (2024).

Sarker, R. et al. The WHO has declared the end of pandemic phase of COVID-19: way to come back in the normal life. Health Sci. Rep. 6, e1544 (2023).

Heimonen, J. et al. A remote household-based approach to influenza self-testing and antiviral treatment. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 15, 469–477 (2021).

Ken Getz, M. B. A. How much does a day of delay in a clinical trial really cost? Appl. Clin. Trials 33 (2024).

DiMasi, J. A. et al. Assessing the financial value of decentralized clinical trials. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 57, 209–219 (2023).

Patil, B. DCTs deliver big ROI. (IQVIA, 2022).

Wang, S. et al. An overview of cancer drugs approved through expedited approval programs and orphan medicine designation globally between 2011 and 2020. Drug Discov. Today 27, 1236–1250 (2022).

Shenoy, P. Multi-regional clinical trials and global drug development. Perspect. Clin. Res. 7, 62–67 (2016).

House, T. W. Executive order on preventing access to Americans’ bulk sensitive personal data and united states government-related data by countries of concern. (2024).

Feehan, A. K. & Garcia-Diaz, J. Investigator responsibilities in clinical research. Ochsner J. 20, 44–49 (2020).

FDA. Conducting Clinical Trials With Decentralized Elements. (2024).

ICH. International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R3) Draft Version. (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H. and N.L. contributed to conception and manuscript design. Y.J. and Y.L. drafted the manuscript and prepared the figures. Q.W., Y.H., and X.D. contributed to related analysis. C.Z., D.W., H.F., and Y.T. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Y., Leng, Y., Wu, Q. et al. Understanding the gap between expectations and reality in decentralized clinical trials. npj Digit. Med. 8, 408 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01811-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01811-y