Abstract

The ICH E9(R1) Addendum on Estimands and Sensitivity Analysis provides a framework for defining the treatment effect a trial intends to estimate—the estimand. The addendum is widely adopted in pharmaceutical research. However, it remains underutilized in trials investigating internet-based interventions (IBIs). This manuscript introduces the addendum to IBI researchers. It concludes that estimands are essential to improve the interpretability, relevance, and validity of effect estimates derived in IBI trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To ensure that randomized controlled trials of (non-) digital (mental) health interventions yield informative results, researchers need to define the intended substantive meaning of the treatment effect they intend to estimate: the estimand1,2,3,4. An estimand forms the basis for designing trials that allow collecting data needed to answer the clinical question. An estimator (i.e., a statistical procedure) that is aligned with the estimand is used to summarize the data and derive an estimate that accurately quantifies the estimand1,3,4.

The ICH E9(R1) Addendum on Estimands and Sensitivity Analyses, developed by regulatory authorities in the pharmaceutical industry, was published to facilitate the process of defining estimands1. Essentially, it recommends three steps1,3:

-

1.

Define the estimand attributes: population, endpoint, treatment, and statistical summary measure1.

-

2.

Identify possible intercurrent events (ICEs): events that occur after treatment initiation and affect either the interpretation or availability of measurements relevant to answering the clinical question (e.g., treatment discontinuation)1.

-

3.

Choose strategies for dealing with ICEs that ensure that the estimate remains aligned with the estimand1.

Pharmacology researchers have adopted the addendum; numerous publications explained, refined, and illustrated its application3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. However, the addendum is underutilized in Internet-based interventions (IBIs: interventions that provide individuals access to evidence-based psychotherapeutic techniques in a digital format) research, despite its potential to (1) enhance the interpretability of IBI studies4,20 and (2) its recognition in the European Medicines Agency (EMA) guidelines on depression trials21 and the updated CONSORT guidelines22. This manuscript provides an overview of the estimand framework for IBI researchers, particularly clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, and non-statistical professionals who play a key role in trial design and implementation. We outline key assumptions and provide resources for statistical details.

Motivating example

Two trials evaluate the same IBI for depression. They use the same inclusion criteria, recruit from routine care, employ a waitlist control, and use self-reported depressive symptoms 8 weeks after randomization as the endpoint.

Trial A assessed depressive symptoms weekly, but only while patients used the IBI. Thus, the endpoint is missing for individuals who discontinued treatment. Trial A replaces missing endpoints using multiple imputations with depression scores collected while individuals used the IBI as auxiliary information. Trial B collects the endpoint from all patients, even if they discontinued the IBI. Thus, Trial B has no missing values.

Since neither study defines what treatment effect they intend to estimate or describes the assumptions underlying their approaches, the reader must infer the meaning of the estimated treatment effect from how the data were collected and analyzed4. It becomes evident that the two trials answer different clinical questions.

Since the imputation model in Trial A only knows how the symptoms develop while individuals are on treatment, it imputes the missing values of discontinuers as if they continued the treatment23,24. Trial A estimates a treatment effect for a hypothetical scenario in which one has found a “magical” measure to get all non-adherers to adhere24,25. However, the assumption that individuals who discontinued IBI have similar symptom trajectories to those who completed it, especially if discontinuation is related to the intervention, worsening of symptoms, or other characteristics that distinguish discontinuers from those who adhere, is unrealistic. Trial A appears to be valid. However, not collecting endpoints from discontinuers can be a trial-related flaw that may lead to overestimated treatment effects that do not generalize to clinically relevant contexts.

Trial B collects the endpoint from all patients, regardless of adherence. It targets the symptom change in a real-world scenario in which treatment discontinuation occurs.

The estimand, its attributes, and intercurrent events

The estimand is the central concept of the ICH E9(R1) addendum. An estimand is a systematic description of the effect researchers want to quantify1,3. The addendum recommends defining the estimand along five attributes1,3.

-

Treatment: A complete description of the treatment regimen for all study arms is required, including all digital (e.g., number of modules, intended dosage) and non-digital components (e.g., whether concurrent antidepressant use is permitted, emergency procedures). It is incorrect to equate the treatment with the IBI; the IBI is typically just the major ingredient of a comprehensive treatment regimen.

-

Population: The eligibility criteria define the target population1. Baseline characteristics inform how well the sample represents it. The addendum highlights the possibility of focusing on principal strata (see section on principal strata)1,3.

-

Endpoint: The endpoint is the variable collected to quantify the treatment effect, including the assessment time and modality1. Endpoints may be questionnaire scores, diagnostic classifications, or composite variables1.

-

Population-level summary: The population-level summary is a statistical measure calculated to quantify the treatment effect1,3. IBI trials are typically interested in differences in mean symptom scores or responder rates.

Table 1 summarizes some considerations for defining these attributes in IBI trials. These aspects are not IBI-specific, but important due to the nature of IBIs.

The first four attributes help to identify relevant intercurrent events (ICEs), defined as “events occurring after treatment initiation that affect either [1] the interpretation or [2] the existence of the measurements associated with the clinical question of interest”1. Researchers should anticipate ICEs and discuss how they relate to the four attributes1,3. ICEs that result in measurements that misalign with one of the attributes are relevant.

Consider a trial that intends to estimate the effect of a scenario in which all individuals use IBI as intended versus no treatment (treatment) among adults with depression (population) in terms of mean differences (population level summary) in PHQ-9 scores 8 weeks after randomization (endpoint). Some patients are expected to discontinue the treatment (ICE). Treatment discontinuation fulfills both criteria of an ICE. First, it affects the interpretation of measurements collected after discontinuation. These measurements reflect the effects of the IBI and everything that happened after discontinuation. Second, measurements necessary to answer the clinical question do not exist for individuals who discontinued the treatment because they did not complete it. To keep the estimate aligned with the estimand, measurements affected by the ICE must be handled properly. This leads to the fifth attribute: the strategies for handling ICE.

-

Handling ICEs: Researchers should handle ICEs in a manner that keeps the estimate aligned with the estimand1,3. The addendum outlines five strategies, which can be combined: (1) treatment policy strategy, (2) hypothetical strategy, (3) while-on-treatment strategy, (4) composite strategy, and (5) principal strata strategy1,3.

The addendum highlights the difference between data affected by an ICE and missing data1,3. Missing data refers to information that was available but has not been collected. In our example, missing data results when individuals who complete the treatment are not assessed. This is different from data affected by an ICE. In our discontinuation example, the data cannot be collected because the individuals have not completed the IBI.

Strategies to treat intercurrent events

The addendum introduces a fundamental principle: whenever an ICE occurs, the post-ICE data, whether observed or missing, must be handled in a way that aligns with the estimand1. This section provides a conceptual overview of the five strategies for handling ICEs suggested in the addendum. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. Each strategy entails trade-offs. The appropriate (combined) strategy depends on the clinical question3,8. How to handle ICEs should be decided in a comprehensive discussion among all stakeholders1. All strategies and statistical methods employed to implement the strategies rely on assumptions. These assumptions should be stated4,7. Sensitivity analyses are necessary to assess the robustness of conclusions against violations of these assumptions1,3.

We focus on treatment discontinuation (ICE) in a simplified treatment regimen that comprises an IBI as the main treatment ingredient. Participants work with eight modules (one per week) in sequential order. We consider the treatment “discontinued” if the person no longer logs in in spite of not yet having completed all available treatment modules. We use this simplified example to illustrate how different strategies alter the interpretation of the treatment effects. Table 2 illustrates the application of the strategies to other ICEs. Table 3 relates the strategies to concepts widely used in IBI research: (a) the intention-to-treat principle, (b) per-protocol analysis, and (c) efficacy vs. effectiveness trials.

Treatment policy strategy

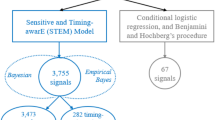

The treatment policy strategy considers the ICE part of the treatment1,3. Measurements remain informative even after an ICE has occurred, making it essential to collect post-ICE measurements1,3. Figure 1A illustrates the treatment policy strategy.

The black solid lines indicate behavior until the ICE occurs or until the assessment of the endpoint. A Treatment policy strategy: Case 1 (C1) completed treatment and the assessment of the endpoint. C2 and C4 discontinued treatment but completed the endpoint assessment; their measurements are retained because discontinuation is considered part of the treatment regimen. C3 and C5 did not complete the endpoint assessment; therefore, endpoints must be modeled. The model must account for the fact that C3 and C5 discontinued the treatment and that C5 started antidepressants after discontinuation. B Hypothetical strategy: C1 completed the treatment and the endpoint assessment. C2 and C3 discontinued the treatment, with C3 completing the endpoint assessment. Given that the trial’s interest in a scenario where discontinuation did not occur, this assessment is non-informative and must be discarded. For both cases, the missing outcomes are modeled to mimic a scenario in which they completed treatment (indicated by gray dashed line). C4 completed treatment but not the assessment. This is “pure” missing data, as it is unrelated to an intercurrent-event (ICE), but still requires modeling. C While-on-treatment strategy: C1 completed treatment; therefore, the endpoint assessment is used. C2 and C3 discontinued treatment; thus, only measurements collected before discontinuation are used for analysis. D Composite strategy: treatment failure is defined as (A) treatment discontinuation or (B) less than 50% symptom improvement (composite measure). C1 completed treatment and endpoint assessments; coded as treatment failure if symptom improvement is under 50%. C2 and C3 discontinued treatment. Hence, they are coded as treatment failures. E Principal stratum strategy: this analysis focuses on the principal stratum of individuals who would complete both treatments, regardless of assignment (TX1: an IBI focusing on cognitive restructuring; TX2: an IBI focusing on behavioral activation). Solid black lines represent behavior under the assigned treatment; dotted black lines represent non-observable behavior under the non-assigned treatment. C1 completed TX1, but would have discontinued TX2. C2 discontinued TX1, but would have completed TX2. In both C1 and C2, the ICE depends on the assigned treatment. C3 would complete both treatments and is thus part of the target stratum. Since statum membership is not observable, it must be estimated.

By including all endpoints, even those affected by an ICE, in the analysis, the interpretation shifts toward the effect of providing access to the IBI, rather than the IBI itself. It quantifies the treatment effect under imperfect adherence.

The EMA recommends this strategy for handling treatment discontinuation in pharmacological trials21. This likely extends to IBI trials. Typically, IBI participants decide for themselves how and with what dose they use the treatment material. Therefore, collecting all endpoints at a pre-defined time point, irrespective of the level of engagement, seems to be the natural approach to consider the self-selected heterogeneity in dosage. This strategy bears challenges. Consider a trial that employs this strategy for parallel treatments. Group differences in the endpoint could emerge (or vanish) because the groups initiate parallel treatments with different likelihoods. However, one must assume that the estimate remains informative. High rates of parallel treatments can mask the ineffectiveness of the main treatment component.

The treatment policy strategy aims to minimize the need for assumptions by collecting data from all participants. Participants in IBI trials typically do not attend study centers. This increases the risk of missing endpoints after treatment discontinuation, especially if completing an assessment is tied to the use of the IBI. Without personal contact, individuals may feel less obligated to complete the online assessments. If measurements affected by an ICE are missing, the missing endpoints must be modeled in a way that accounts for the fact that the ICE has occurred25,26. Without any information about the post-ICE symptom course, researchers must rely solely on assumptions, such as that the post-discontinuation symptom course parallels that of patients in the control group17,23,24,27,28. These assumptions can typically not be verified. Researchers should therefore collect data that is as complete as possible. Thus, strategies to reduce missing values are needed29,30. Resources on the treatment policy strategy are available3,18,23,24,27,31,32.

Hypothetical strategy

The hypothetical strategy estimates the treatment effect for a well-defined what-if scenario, assuming that the ICE did (or did not) occur1,3. Thus, it is impossible to derive a meaningful estimate using observed measurements affected by an ICE. Instead, the endpoints affected by an ICE are modeled in a manner that attempts to mimic the endpoints that would have occurred in the hypothetical scenario1,3,33.

Figure 1B illustrates this strategy. The hypothetical strategy shifts the interpretation of the estimate towards an effect that would have been observed if discontinuation had not occurred. The strategy relies on two key assumptions: First, the hypothetical scenario is clinically meaningful1,3. Second, given all available data, the symptom course in the hypothetical scenario can be predicted1,3. Both are often questionable, especially when the rates with which ICEs occur are large (e.g., discontinuation in IBI trials); therefore, caution is needed. If used, the underlying assumptions must be reported1,21.

The following example illustrates possible challenges. A study aims to estimate the effect of a scenario in which all participants complete the IBI (i.e., work with all modules in the intended timeframe). To achieve this goal, one must assume that data from individuals who completed IBI is sufficient to estimate the symptom trajectories of those who discontinued treatment as if they had continued treatment (i.e., the missing-at-random assumption, MAR). However, individuals may discontinue the IBI due to dissatisfaction or deteriorating symptoms, and may differ in other characteristics from completers. Therefore, the available information might be insufficient (i.e., we did not collect all relevant covariates) to recover symptom trajectories with continued treatment. The MAR estimates will be biased and may not generalize to real-world settings, particularly when attrition rates are high.

The hypothetical strategy typically relies on some variant of multiple imputations; however, other approaches exist. Several resources are available3,7,18,31,33.

While-on-treatment strategy

The while-on-treatment strategy assumes that measurements collected before the ICE occurred contain all relevant information. Measurements after the ICE are irrelevant1,3.

Figure 1C illustrates this strategy. The strategy yields an estimate that reflects the treatment effects up to the point at which an ICE occurs.

It is typically less relevant for evaluating the effects of IBI treatment. However, it can be used to assess safety-related aspects, such as the rate of suicides, while following the assigned treatment. However, some aspects warrant attention. First, the strategy may provide an incomplete picture of all adverse events that occur in the context of the treatment3,34. In particular, the strategy fails to detect adverse events occurring immediately after discontinuation, such as hospitalization or suicide, which could be a consequence of an ineffective treatment. Second, if people in one treatment arm tend to discontinue the treatment earlier, and the risk of adverse events increases over time, event rates may appear lower due to the lower time on treatment. The interpretability of the between-group differences in rates of adverse events becomes misleading. Therefore, a safety assessment of an IBI should combine the while-on-treatment strategy with assessments collected after discontinuation34. Interested readers will find more information elsewhere3,18,35.

Composite strategy

A composite measure is a single outcome variable that combines two or more endpoints1,3. The composite strategy considers the ICE part of the endpoint.

Figure 1D illustrates the strategy. The composite strategy shifts the interpretation towards an effect that is a mixture of different components. Consequently, the strategy assumes that the composite measure offers a meaningful interpretation. In particular, it assumes that the components have similar clinical relevance (a limitation that applies to all composite endpoints)3,36.

The following example illustrates the interpretative challenges that can emerge when this assumption is violated. Consider two trials that classify a treatment as a failure if (a) there was no reduction in suicidal ideation or (b) hospitalization was required due to suicidal ideation (e.g., rate of treatment failures is the endpoint). Both studies report treatment failure rates of 15%. In study A, 95% of failures were due to no reduction in suicidal ideation, and 5% were due to hospitalization. Study B reports reversed rates. Claiming that both IBIs are equally effective is misleading. Thus, it is essential to report the rate of individual components or to apply appropriate weighting36,37. Further problems arise when the likelihood of certain components differs across treatment arms. Consider a trial that compares antidepressants against an IBI. In the antidepressant arm, treatment discontinuation may result from physiological adverse events that can’t occur in IBIs. Thus, the reasons why the ICE occurred must be considered. Composite strategies may fall short of meeting regulatory expectations. Therefore, even when employing a composite strategy, collecting post-ICE data is advisable. More information is provided elsewhere3,18,36,37.

Principal stratum strategy

The principal stratum strategy aims to quantify the treatment effect within the latent stratum of individuals who would (or would not) experience an ICE, regardless of the assigned treatment1,3. For instance, in a two-arm trial, one could be interested in the effect among individuals who would complete both treatments, irrespective of which treatment arm they are assigned (see ref. 38 for further examples)38,39. Alternatively, one may focus on individuals who would complete the IBI if assigned to the IBI. Thus, the stratum is defined based on how individuals would behave under different treatments38,39.

Figure 1E illustrates the strategy. This interpretation of the treatment effects shifts towards the latent population of individuals defined by the (non-)occurrence of the ICE. The estimate no longer quantifies the effect among all randomized individuals1,5.

In theory, this strategy can address clinically relevant questions, such as which treatment yields longer-lasting effects among individuals who would complete both treatments. Beyond the fact that it can be challenging to define what completion means in IBI trials (see Table 1), it is impossible to observe if an individual will experience the ICE under both treatments. Untestable assumptions are necessary when determining whether an individual belongs to the stratum of interest3,38,39. One may attempt to model stratum membership using baseline variables39. However, it is impossible to identify stratum membership without error; the statistical analysis must take this into account3,38,39.

Kahan et al. discuss rare instances in which strata appear naturally40. Consider a study comparing guided versus unguided IBI. Some individuals discontinue the treatment before learning their assigned trial arm. Since discontinuation is unrelated to the treatment, excluding them from the analysis won’t introduce bias40. The interpretation shifts toward the subset of individuals who would always start the assigned treatment (=the principal stratum)40. Guidance on appropriate statistical approaches is provided elsewhere3,7,18,38,39.

Two examples

Several applications of the framework to pharmacological treatments have been published11,12,13,14,41,42,43,44. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 present two fictitious examples of IBI trials. They are not intended as best-practice examples, but rather to illustrate the principles of the addendum. The example follows the template to describe trials provided by Ratitch et al.8,9.

Discussion

This manuscript introduced the ICH E9(R1) addendum to IBI researchers. The addendum prompts prioritizing the collection of measurements vital for answering the clinical question and anticipating how ICEs impair the availability of needed measurements1. When ICEs are anticipated, trial design and statistical approach can be aligned to derive informative estimates. Trial protocols should report the targeted estimand1,22,45. Reports of completed trials should provide sufficient detail to derive the estimand20,46. This includes describing estimated effects with precise language. Instead of claiming that the “IBI was effective,” one might report that “group differences reflect the effect that could be achieved if all individuals would be compliant” when the hypothetical strategy was employed18.

Standardized reporting of estimands will facilitate the synthesis of findings in meta-analyses6. Currently, the lack of clarity in reporting estimands hampers systematic evaluations of how estimands explain between-study heterogeneity20,46. To increase understanding of estimands, helpful teaching materials have been published16,26,47.

While this manuscript focuses on parallel group trials, the framework extends to factorial designs48, cluster randomized trials49, and non-inferiority and equivalence trials42,50,51,52. It should also be considered in face-to-face psychotherapy trials.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

ICH. ICH harmonized guideline: Addendum on estimands and sensitivity analysis in clinical trials to the guideline on statistical principles for clinical trials E9(R1). (2019).

Lundberg, I., Johnson, R. & Stewart, B. M. What is your estimand? Defining the target quantity connects statistical evidence to theory. Am. Sociol. Rev. 86, 532–565 (2021).

Mallinckrodt, C. H., Molenberghs, G., Lipkovich, I. & Ratitch, B. Estimands, Estimators and Sensitivity Analysis in Clinical Trials. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, 2020.

Kahan, B. C., Cro, S., Li, F. & Harhay, M. O. Eliminating ambiguous treatment effects using estimands. Am. J. Epidemiol. 192, 987–994 (2023).

Kahan, B. C., Hindley, J., Edwards, M., Cro, S. & Morris, T. P. The estimands framework: a primer on the ICH E9(R1) addendum. BMJ e076316 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-076316 (2024).

Pohl, M. et al. Estimands—a basic element for clinical trials. Part 29 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0373 (2021).

Mallinckrodt, C. H. et al. Aligning estimators with estimands in clinical trials: putting the ICH E9(R1) guidelines into practice. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 54, 353–364 (2020).

Ratitch, B. et al. Choosing estimands in clinical trials: putting the ICH E9(R1) into practice. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 54, 324–341 (2020).

Ratitch, B. et al. Defining efficacy estimands in clinical trials: examples illustrating ICH E9(R1) guidelines. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 54, 370–384 (2020).

Akacha, M. et al. Estimands—What they are and why they are important for pharmacometricians. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 10, 279–282 (2021).

Fu, R., Li, H., Wang, X., Shou, Q. & Wang, W. W. B. Application of estimand framework in ICH E9 (R1) to vaccine trials. J. Biopharm. Stat. 33, 502–513 (2023).

De Silva, A. P., Leslie, K., Braat, S. & Grobler, A. C. Application of the estimand framework to anesthesia trials. Anesthesiology 141, 13–23 (2024).

Yassi, N., Hayward, K. S., Campbell, B. C. V. & Churilov, L. Use of the estimand framework to manage the disruptive effects of COVID-19 on stroke clinical trials. Stroke 52, 3739–3747 (2021).

Aroda, V. R. et al. Incorporating and interpreting regulatory guidance on estimands in diabetes clinical trials: the PIONEER 1 randomized clinical trial as an example. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 21, 2203–2210 (2019).

Jin, M. & Liu, G. Estimand framework: delineating what to be estimated with clinical questions of interest in clinical trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials 96, 106093 (2020).

Cro, S. et al. Starting a conversation about estimands with public partners involved in clinical trials: a co-developed tool. Trials 24, 443 (2023).

Keene, O. N., Wright, D., Phillips, A. & Wright, M. Why ITT analysis is not always the answer for estimating treatment effects in clinical trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials 108, 106494 (2021).

Han, S. & Zhou, X. Defining estimands in clinical trials: a unified procedure. Stat. Med. 42, 1869–1887 (2023).

Fiero, M. H. et al. Demystifying the estimand framework: a case study using patient-reported outcomes in oncology. Lancet Oncol. 21, e488–e494 (2020).

Cro, S. et al. Evaluating how clear the questions being investigated in randomised trials are: systematic review of estimands. 378, e070146 (2022).

EMA/CHMP/185423/2010. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products in the treatment of depression.

Hopewell, S. et al. CONSORT 2025 explanation and elaboration: updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 389, e081124 (2025) .

Drury, T., Abellan, J. J., Best, N. & White, I. R. Estimation of treatment policy estimands for continuous outcomes using off-treatment sequential multiple imputation. Pharm. Stat. 23, 1144–1155 (2024).

Bell, J. et al. Estimation methods for estimands using the treatment policy strategy; a simulation study based on the PIONEER 1 trial. Pharm. Stat. 24, e2472 (2025).

Wang, S. & Hu, H. Impute the missing data using retrieved dropouts. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 22, 82 (2022).

Fletcher, C. et al. Marking 2-years of new thinking in clinical trials: the estimand journey. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 56, 637–650 (2022).

Mallinckrod, C. & Lipkovich, I. Analyzing Longitudinal Clinical Trial Data: A Practical Guide (CRC PRESS, 2020).

Carpenter, J. R., Roger, J. H. & Kenward, M. G. Analysis of longitudinal trials with protocol deviation: a framework for relevant, accessible assumptions, and inference via multiple imputation. J. Biopharm. Stat. 23, 1352–1371 (2013).

Mallinckrodt, C. H. Preventing and Treating Missing Data in Longitudinal Clinical Trials: A Practical Guide (Cambridge University Press, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139381666.

Little, R. J. et al. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1355–1360 (2012).

Carpenter, J. R. Multiple Imputation and Its Application (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Statistical methods for handling missing data to align with treatment policy strategy. Pharm. Stat. 22, 650–670 (2023).

Olarte Parra, C., Daniel, R. M. & Bartlett, J. W. Hypothetical estimands in clinical trials: a unification of causal inference and missing data methods. Stat. Biopharm. Res. 15, 421–432 (2023).

Yang, F., Wittes, J. & Pitt, B. Beware of on-treatment safety analyses. Clin. Trials 16, 63–70 (2019).

Ting, N., Huang, L., Deng, Q. & Cappelleri, J. C. Average response over time as estimand: an alternative implementation of the while on treatment strategy. Stat. Biosci. 13, 479–494 (2021).

Rauch, G., Schüler, S. & Kieser, M. Planning and Analyzing Clinical Trials with Composite Endpoints (Springer Nature, 2018).

Hara, H. et al. Statistical methods for composite endpoints. EuroIntervention 16, e1484–e1495 (2021).

Bornkamp, B. et al. Principal stratum strategy: potential role in drug development. Pharm. Stat. 20, 737–751 (2021).

Lipkovich, I. et al. Using principal stratification in analysis of clinical trials. Stat. Med. 41, 3837–3877 (2022).

Kahan, B. C., White, I. R., Edwards, M. & Harhay, M. O. Using modified intention-to-treat as a principal stratum estimator for failure to initiate treatment. Clin. Trials 20, 269–275 (2023).

Leuchs, A.-K., Zinserling, J., Brandt, A., Wirtz, D. & Benda, N. Choosing appropriate estimands in clinical trials. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 49, 584–592 (2015).

Sepin, J. et al. Applying the principal stratum strategy in equivalence trials: a case study. Pharm. Stat. 24, e70008 (2025).

Mitroiu, M., Teerenstra, S., Oude Rengerink, K., Pétavy, F. & Roes, K. C. B. Estimation of treatment effects in short-term depression studies. An evaluation based on the ICH E9 (R1) estimands framework. Pharm. Stat. 21, 1037–1057 (2022).

Lynggaard, H. et al. Applying the estimand framework to clinical pharmacology trials with a case study in bioequivalence. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 91, 310–324 (2025).

Lynggaard, H. et al. Principles and recommendations for incorporating estimands into clinical study protocol templates. Trials 23, 685 (2022).

Kahan, B. C., Morris, T. P., White, I. R., Carpenter, J. & Cro, S. Estimands in published protocols of randomised trials: urgent improvement needed. Trials 22, 686 (2021).

ICH E9(R1) Expert Working Group. ICH E9(R1) Estimands and Sensitivity Analysis in Clinical Trials Training Module 1: Summary. Addendum to ICH E9 – Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials. (2021).

Kahan, B. C., Morris, T. P., Goulão, B. & Carpenter, J. Estimands for factorial trials. Stat. Med. 41, 4299–4310 (2022).

Kahan, B. C., Li, F., Copas, A. J. & Harhay, M. O. Estimands in cluster-randomized trials: choosing analyses that answer the right question. Int. J. Epidemiol. 52, 107–118 (2023).

Rehal, S., Cro, S., Phillips, P. P., Fielding, K. & Carpenter, J. R. Handling intercurrent events and missing data in non-inferiority trials using the estimand framework: a tuberculosis case study. Clin. Trials 20, 497–506 (2023).

Lynggaard, H., Keene, O. N., Mütze, T. & Rehal, S. Applying the estimand framework to non-inferiority trials. Pharm. Stat. 23, 1156–1165 (2024).

Morgan, K. E., White, I. R., Leyrat, C., Stanworth, S. & Kahan, B. C. Applying the estimands framework to non-inferiority trials: guidance on choice of hypothetical estimands for non-adherence and comparison of estimation methods. Stat. Med. 44, e10348 (2025).

Montedori, A. et al. Modified versus standard intention-to-treat reporting: Are there differences in methodological quality, sponsorship, and findings in randomized trials? A cross-sectional study. Trials 12, 58 (2011).

Hernán, M. A. & Hernández-Díaz, S. Beyond the intention-to-treat in comparative effectiveness research. Clin. Trials 9, 48–55 (2012).

Apter, A. et al. Irregular assessment times in pragmatic randomized clinical trials. Trials 25, 841 (2024).

Pullenayegum, E. M. & Scharfstein, D. O. Randomized trials with repeatedly measured outcomes: handling irregular and potentially informative assessment times. Epidemiol. Rev. 44, 121–137 (2022).

Luo, Y. et al. Large variation existed in standardized mean difference estimates using different calculation methods in clinical trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 149, 89–97 (2022).

Cumming, G. Cohen’s d needs to be readily interpretable: comment on Shieh (2013). Behav. Res. Methods 45, 968–971 (2013).

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Wiley, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604.

Leuchs, A., Brandt, A., Zinserling, J. & Benda, N. Disentangling estimands and the intention-to-treat principle. Pharm. Stat. 16, 12–19 (2017).

Keene, O. Adherence, per-protocol effects, and the estimands framework. Pharm. Stat. 22, 1141–1144 (2023).

Hernán, M. A. & Robins, J. M. Per-protocol analyses of pragmatic trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1391–1398 (2017).

Wirtz, M. Effectiveness im Dorsch Lexikon der Psychologie. (Hogrefe, 2021).

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Freie Universität Berlin.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H. and L.S. drafted the manuscript text and prepared the figures and examples. P.Z., J.B. and C.K. reviewed and revised the initial draft. All authors reviewed the submitted version of the manuscript. Once the manuscript was drafted, we used ChatGPT, Deepl, and Grammarly to improve the quality and conciseness of the language.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heinrich, M., Zagorscak, P., Bohn, J. et al. Using the ICH estimand framework to improve the interpretation of treatment effects in internet interventions. npj Digit. Med. 8, 535 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01936-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01936-0