Abstract

The growing burden of insomnia underscores the necessity for accessible and effective treatments, with digital therapeutics offering a promising solution. A systematic search was conducted across seven databases (PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, MEDLINE, ProQuest, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library) covering the period from the inception of each database until October 2024. A total of 28 systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating digital therapeutics with reported insomnia-related outcomes were included, encompassing 118,970 participants. The primary outcome, Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), indicated that digital therapeutics significantly improved insomnia (SMD = −0.42, p < 0.01), with better results observed during follow-up (SMD = −0.69, p < 0.01). Under the guidance of therapists, digital therapeutics exerted a more positive effect (SMD = −1.05, p < 0.01). The secondary outcomes also showed consistent results, with no significant differences observed in Total Sleep Time (TST) between the post-intervention and follow-up periods. Based on the assessment results, there is sufficient evidence to recommend the use of digital therapeutics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insomnia is a prevalent sleep disorder characterized by difficulties in falling asleep, maintaining sleep, or early awakening, which significantly impair both the physical and mental health of affected individuals, as well as their overall quality of life1. Insomnia not only causes fatigue, concentration difficulties, and mood disturbances, but is also closely related to depression, anxiety, and increased risk of suicide2. Moreover, the productivity loss and increased healthcare costs associated with insomnia impose a significant socio-economic burden on society3. The global prevalence of insomnia has been steadily rising4,5, with the quality of sleep further deteriorating during the COVID-19 pandemic6,7. As a potential risk factor for both morbidity and mortality, insomnia has emerged as a critical public health issue8.

Currently, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is widely considered to be the first-line treatment for insomnia9,10,11,12. CBT-I improves patients’ sleep quality and reduces the risk of long-term dependence on medication by adjusting sleep-related cognitions and behaviors. However, although the effectiveness of CBT-I has been confirmed by a large number of studies, its implementation in clinical practice is still insufficient, mainly due to factors such as limited resources for professional therapists, inconvenience for patients to visit the doctor, and high treatment costs13,14. This lack of implementation has led to the development of digital cognitive behavioral therapy (dCBT-I) to improve the accessibility of traditional treatments and benefit more patients with insomnia.

The rapid development of digital technology in recent years has led to the emergence of digital therapeutics for insomnia delivered through platforms such as the Internet, mobile applications, and virtual reality15,16,17. Common digital therapies for insomnia (DTI) include digital cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (dCBT-I), digital brief behavioral therapy for insomnia (dBBT-I), digital mindfulness-based therapy for insomnia (dMBTI), and tele-neurofeedback (tNFB). Leveraging digital scales, sleep diaries, wearable devices, and other technological tools18,19, DTI can capture data pertaining to the patient’s actual sleep-wake times and intrinsic circadian rhythms20. This enables the provision of instant feedback to assist patients in monitoring and modifying their sleep habits and developing tailored treatment plans.

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that digital therapeutics can significantly improve sleep quality in patients with insomnia21,22. However, other studies have highlighted that the efficacy of digital therapeutics may be constrained by individual differences, the diversity of treatment options, and the acceptability of technology23,24. Furthermore, the effectiveness evaluation of digital therapeutics is complicated by the differences in intervention methods, efficacy evaluation criteria, and follow-up periods observed in existing literature25,26. There are considerable variations among studies in terms of intervention protocols, sample selection, and assessment criteria. These make it challenging to achieve a comprehensive and systematic understanding of the actual effects of digital therapies across various populations, time periods, and intervention modalities. In addition, concerns regarding digital therapeutics cannot be overlooked, and the adaptability of digital therapies in actual clinical applications warrants further investigation. Collectively, these factors add another layer of complexity to the discussion on the effectiveness of digital therapeutics.

To account for the above, this study integrates and interprets existing systematic review and meta-analysis studies from the perspective of umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis. Unlike traditional meta-analysis, meta-meta-analysis, as a higher-order systematic evaluation method, can integrate the results of multiple related meta-analyses to assess the consistency of effects across different studies27,28. It can reveal more nuanced study heterogeneity and analyze the differences in the effects of various therapeutic regimens across different time frames and intervention modalities. In particular, it can shed light on the specific effects of digital therapies in a more comprehensive population. Through this more comprehensive and systematic analysis, we can explore potential factors influencing treatment efficacy, thereby providing a more systematic and in-depth theoretical basis and practical guidance for future research. Based on the points, the present umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic evaluation of digital therapeutics for insomnia. Specifically, it focuses on assessing their impact on improving sleep quality, shortening sleep latency, and prolonging sleep duration. Moreover, subgroup analyses are conducted to explore how different outcome measures, intervention modes, and follow-up durations influence the effectiveness of digital therapeutics.

Results

Research characteristics

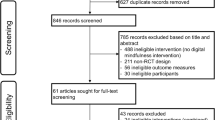

The literature search identified 3793 articles, and 2969 articles remained after removing duplicates. There were 2728 articles removed due to title and abstract ineligibility. Following title and abstract screening, and full-text reviews, 28 systematic reviews were eligible, of which 22 meta-analyses were included in the meta-meta-analysis. Further details of excluded articles with reasons were shown in Fig. 1. The consistency for title and abstract screening in the first round was 92.39%, while the consistency for full-text screening in the second round was 95.44%. Table 1 provides the characteristics of the systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in the umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis. These articles were published between 2012 and 2024, with the majority published since 2021 (n = 18). The number of studies in each systematic review ranged from 3 to 54 articles (Median 16, IQR 9–21), and the number of participants ranged from 239 to 13,227 (Median 3970, IQR 1604–10,139).

Risk-of-bias results

Methodological strengths across the included reviews included providing information on the characteristics of the included studies (100%), conflict of interest declarations (78.57%), performing study selection (78.57%) and data extraction (75%) in duplicate, and reporting study heterogeneity in meta-meta-analysis (75%). Common methodological weaknesses were failure to extract data on funding sources (0%), failure to provide a complete list of excluded studies (14.29%), and failure to explain the risk of bias in meta-meta-analysis (21.43%). One systematic review was rated as high confidence29, 6 were rated as moderate confidence23,30,31,32,33,34, 13 were rated as low confidence16,21,26,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44, and the remaining 8 were rated as critically low confidence17,22,45,46,47,48,49,50. The detailed quality assessment table is provided in Supplementary Table 8.

Study overlap results

The 28 included systematic evaluations reported a total of 518 component studies, leaving 253 unique component studies after removing duplicates. The CCA was 3.88, indicating only slight overlap.

Effect of digital therapeutics on sleep outcomes

Sleep outcome measures varied between studies and included the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), etc. Where available, the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), the most commonly used measure, was selected as the primary sleep outcome. Moreover, sleep efficiency (SE), sleep quality (SQ), sleep onset latency (SOL), wake after sleep onset (WASO), number of awakenings (NWAK), and total sleep time (TST) were served as secondary outcomes. Digital therapeutics had a significant improvement effect on ISI (SMD = −0.42, 95% CI: −0.67 to −0.17, p < 0.01, k = 21) (shown in Fig. 2), and the statistical heterogeneity of effect size between studies is high (I2 = 96%, p < 0.01) (shown in Fig. 2). For secondary outcomes, the effects were equally significant. The improvement in sleep quality (SQ) showed the strongest effect (SMD = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.42 to 0.6, p < 0.01, I2 = 0%, k = 9, Supplementary Fig. 2). Positive effects were also found for sleep efficiency (SE) (SMD = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.28 to 0.46, p < 0.01, I² = 69%, k = 22, Supplementary Fig. 1), sleep onset latency (SOL) (SMD = −0.33, 95% CI: −0.44 to −0.22, p < 0.01, I² = 82%, k = 21, Supplementary Fig. 3), wake after sleep onset (WASO) (SMD = −0.34, 95% CI: −0.48 to −0.2, p < 0.01, I² = 83%, k = 19, Supplementary Fig. 4), and number of wake episodes (NWAK) (SMD = −0.26, 95% CI: −0.32 to −0.2, p < 0.01, I² = 21%, k = 8, Supplementary Fig. 5), whereas the effect size for total sleep time (TST) was smaller (SMD = 0.19, 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.29, p < 0.01, I² = 91%, k = 22, Supplementary Fig. 6). Forest plots for the secondary outcomes are detailed in Supplementary Figs. 1–6.

Sensitivity analysis

In the light of the heterogeneity among studies, the study used leave-one-out method to conduct sensitivity analysis for those cases with high heterogeneity, and the results are reported in Supplementary Fig. 7 to Supplementary Fig. 11. It can be seen that the heterogeneity decreased after excluding certain outliers, and the treatment effect of digital therapeutics on insomnia was still robust. The results for the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (SMD = −0.36, 95% CI: −0.5 to −0.21, p < 0.01, I² = 95%, k = 20, Supplementary Fig. 7), sleep efficiency (SE) (SMD = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.32 to 0.46, p < 0.01, I² = 63%, k = 21, Supplementary Fig. 8), sleep onset latency (SOL) (SMD = −0.35, 95% CI: −0.42 to −0.27, p < 0.01, I² = 78%, k = 20, Supplementary Fig. 9), wake after sleep onset (WASO) (SMD = −0.37, 95% CI: −0.48 to −0.26, p < 0.01, I² = 80%, k = 18, Supplementary Fig. 10), and total sleep time (TST) (SMD = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.11 to 0.23, p < 0.01, I² = 62%, k = 21, Supplementary Fig. 11) remained consistent.

Subgroup analysis

Post-treatment and follow-up effects of digital therapeutics

Ten of the included papers discussed the short- and long-term effects of digital therapeutics. Subject to the amount of data available, the study conducted subgroup analysis for post-treatment and follow-up effects. The results indicated that digital therapeutics had better follow-up effects on the Insomnia Severity Index, shown in Fig. 3. Further subdivision of the follow-up time subgroup yielded consistent findings, and digital therapeutics played a better role after 3 months, with the effect size increasing to −0.69 shown in Fig. 4.

Secondary outcomes such as sleep efficiency (SE), sleep quality (SQ), sleep onset latency (SOL), and wake after sleep onset (WASO) exhibited similar results (shown in Supplementary Fig. 12 to Supplementary Fig. 15), which further supporting the robustness of the present meta-meta-analysis. However, the post-treatment and follow-up effects on total sleep time (TST) were comparable, with no significant difference in the improvement of TST between post-intervention and follow-up period (shown in Supplementary Fig. 16).

Effect of digital therapeutics with therapist guidance

The presence or absence of therapist guidance in the intervention may lead to differences in patient experience and the effectiveness of digital therapeutics. Five studies reported the impact of therapist-guided digital therapeutics on the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), as shown in Fig. 5. Therapist-guided digital therapeutics (SMD = −1.05, 95% CI: −1.2 to −0.9, p < 0.01, I² = 45.3%, k = 3) were found to be more effective than non-therapist-guided digital therapeutics (SMD = −0.84, 95% CI: −0.97 to −0.71, p < 0.01, I² = 0%, k = 2). Moreover, seven studies reported changes in the effects of digital therapeutics on sleep efficiency (SE) and sleep onset latency (SOL) with and without therapist involvement. The results were consistent, indicating that therapist-guided digital therapeutics were more effective in improving treatment outcomes (shown in Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18).

Effect of digital therapeutics by control group type

To address potential heterogeneity arising from different control group types, this study conducted subgroup analyses on the effectiveness of digital therapeutics for insomnia across different comparator groups. Control conditions were classified into three groups: (1) Passive Control, including waitlist or treatment as usual (TAU), where no active intervention was provided; (2) Face-to-Face Control, referring to comparisons with traditional in-person cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) or other face-to-face interventions;(3) Mixed Control, encompassing controls that involve both passive elements and a certain degree of active intervention (e.g., receiving educational components without full CBT-I strategies).

The Results revealed significant differential effects on Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) scores across control types, as shown in Fig. 6. The largest effect size was observed against passive controls (SMD = −0.78, 95% CI: −1.00, −0.57). In contrast, digital therapeutics demonstrated significantly less pronounced effects when compared to face-to-face interventions (SMD = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.45). These findings suggest that digital therapeutics exhibit superior efficacy relative to passive controls but attenuated effectiveness versus face-to-face controls.

Qualitative synthesis

Among the 28 included systematic reviews, 16 studies examined the effectiveness of digital therapeutics for adult insomnia, 5 focused on adolescents, only 1 addressed the elderly, and 6 did not impose age restrictions on the study population. For adult insomnia interventions, digital therapeutics primarily involved digital cognitive behavioral therapy (dCBT), delivered through mobile applications, smartphones, and online platforms. Additionally, other digital sleep interventions, such as eHealth-based psychosocial interventions and prescription digital therapeutics, were explored, highlighting a diverse range of intervention approaches. Among the studies on adolescent insomnia, 3 were qualitative studies of systematic reviews, while 2 were quantitative studies of meta-analysis. The results of quantitative studies reported effect sizes for dCBT in improving adolescent insomnia ranging from −0.58 to −0.8031,32. Although face-to-face CBT-I was slightly superior to dCBT in statistics, the difference was small, suggesting that dCBT remains a viable alternative for clinical intervention. The only systematic review on insomnia in the elderly categorized digital therapeutic interventions into Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy (CBTi), virtual coaches, and sleep technologies49. This study revealed the potential of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in enhancing insomnia care for older adults, offering a novel digital intervention perspective for insomnia management in the elderly.

Publication bias results

Funnel plots were visually inspected to estimate publication bias, and the asymmetry of distribution was further confirmed using Egger test. The relevant funnel plots can be found in Supplementary Fig. 19 to Supplementary Fig. 25. Egger’s test showed no significant bias for the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (t = −1.01, p = 0.32), sleep efficiency (SE) (t = 0.22, p = 0.83), sleep quality (SQ) (t = 1.34, p = 0.22), sleep onset latency (SOL) (t = 0.09, p = 0.93), wake after sleep onset (WASO) (t = −0.64, p = 0.53), number of wake episodes (NWAK) (t = −0.33, p = 0.75), and total sleep time (TST) (t = −1.59, p = 0.13), indicating the absence of publication bias.

Discussion

In this paper, we conducted an umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of digital therapeutics in the treatment of insomnia. A total of 28 systematic reviews were included in the umbrella review, of which 22 meta-analyses were included in the meta-meta-analysis. The results indicated that digital therapeutics, as a viable treatment method, significantly improved insomnia symptoms. It showed substantial positive effects across various dimensions, including ISI, SE, SQ, SOL, WASO, NWAK, and TST, highlighting its great potential. The prospect of digital therapeutics compared with traditional treatments lies in their relatively low cost and high time efficiency, high scalability, and wide accessibility51. To benefit from lower cost and higher efficiency, patients are able to receive digital therapeutics interventions to improve sleep quality at any time and place52.

Subgroup analysis of post-treatment and follow-up effects investigated the long-term impact of digital therapeutics and observed the continuity of outcomes over time. It was found that, in addition to yielding favorable short-term effects, digital therapeutics also led to significant improvements during follow-up period, with three months being an optimal time frame for the better effects to be realized. While traditional pharmacological treatments are effective quickly, long-term use may lead to dependency and side effects53,54. In contrast, digital therapeutics have demonstrated positive effects in both the short and long term, and are thus more appropriate for the long-term rehabilitation of insomnia patients.

In addition, subgroup analyses also revealed that therapist-guided digital therapeutics demonstrated better effectiveness. Digital therapeutics can facilitate real-time communication and feedback between patients and therapists through digital platforms49. Thus, interaction plays a crucial role in the function of digital therapeutics. Moreover, the result further suggests that interaction between therapists and patients enhances treatment effectiveness, which may be related to higher treatment adherence as therapist guidance played a supervisory role to some extent30,55. Nevertheless, digital therapeutics guided by therapists always require specific therapist training and labor costs to implement, which may also limit its scalability50.

Subgroup analysis of control group type indicated that digital therapeutics demonstrated a greater treatment effect compared to passive control groups, while its effect may be weaker or comparable to traditional face-to-face interventions. This finding likely reflects the clinical advantages of face-to-face interventions while also underscoring the value of digital therapeutics in delivering effective treatment without the need for in-person contact. Future research should further investigate hybrid models that integrate digital therapeutics with face-to-face interventions to enhance treatment efficacy, particularly in settings with limited medical resources or where patients face barriers to accessing in-person care, so as to enhance the clinical accessibility and broader applicability of digital therapeutics.

The qualitative analysis of the systematic reviews included in this study revealed variations in the effectiveness of digital therapeutics for insomnia across different age groups. For adults, digital therapeutics primarily consist of digital cognitive behavioral therapy (dCBT) and are delivered through a diverse range of modalities. Meta-analyses of adolescent populations indicated that dCBT had a moderate effect size (−0.58 to −0.80) in improving insomnia. While slightly less effective than face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy, it still holds clinical utility. Research on digital therapeutics for elderly individuals remains limited, though existing reviews highlight the potential of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in managing insomnia in this population. Overall, digital therapeutics represents a promising intervention for insomnia management, yet further research is needed to optimize its applicability across different demographic groups.

Compared with previous studies, this research included a large sample size covering 118,970 participants and employed a rigorous methodology. While previous reviews usually overlook the consideration of study overlap, this study first addresses the issue of overlap. After calculating and confirming minimal overlap, we proceeded with the meta-meta-analysis. Additionally, due to the high heterogeneity across studies, we conducted sensitivity analyses and subgroup analyses to explore the effects of follow-up time, intervention type, and other factors on treatment outcomes. Last but not least, quality assessment was performed to evaluate the risk of bias. The results of reviews with different risk of bias ratings were found to be consistent, which indicated the robustness of the findings27,56. These results provided more substantial, rigorous and credible support for the effects of digital therapeutics on multiple dimensions of insomnia.

The following limitations need to be considered when interpreting the results of the current meta-meta-analysis. Firstly, although the random-effects model was designed to statistically account for heterogeneity across studies, variability in participant and study characteristics (such as insomnia diagnostic criteria, treatment duration, and sample size) may reduce the internal validity of the current meta-meta-analysis. Second, due to the limited number of studies focusing on examining intervention duration, we were unable to perform a combined analysis of these effect sizes, which warrants further investigation in the future. Third, most of the studies included in this umbrella review relied on subjective measures, such as questionnaires and scales, to assess insomnia-related outcomes, with relatively few objective measurements (e.g., actigraphy data)57. Future research could explore the differences introduced by varying measurement methods. Finally, the effects of digital therapeutics for insomnia may vary across various populations31. While most of the studies included in this umbrella review focused on adult populations, data from other age groups were sufficient to conduct subgroup analyses. Future studies can consider a broader range of demographic characteristics.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-meta-analysis (umbrella review) was conducted according to the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (version 5.1) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines58. The review protocol was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42024621910). The PRISMA 2020 checklist was provided in Supplementary Table 9.

Data source and search strategy

This umbrella review searched seven databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, MEDLINE, ProQuest, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library to identify English-language peer-reviewed articles published from the inception of each database up to October 2024. Following the PICOS principles, search strings related to digital therapeutics, insomnia, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were developed and designed to identify studies focusing on digital therapeutics for patients with insomnia. Search strategies were detailed in Supplementary Table 1 to Supplementary Table 7. Manual searches were also conducted by reviewing the reference lists of included studies to identify additional relevant articles. This iterative process was repeated until no further new studies were found.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were structured following the PICOS framework as follows59. Population: covering participants of any nationality and age group, who met at least one of the following conditions: (1) have been diagnosed with insomnia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD), International Classification of Diseases (ICD), or a validated insomnia questionnaire. (2) have self-reported insomnia symptoms. Intervention: delivered via the internet, mobile applications, and wearable devices, such as digital cognitive behavioral therapy (dCBT), virtual reality therapy (VR), remote neurofeedback (NFB), and self-management tools. These interventions typically facilitate improvements in sleep quality and modifications to sleep behaviors involving interactive content, sleep diaries, push notifications, or real-time physiological monitoring. Furthermore, digital therapeutics also include online sleep education, health advice, and video consultations to enhance patient adherence to treatment and provide personalized sleep management plans. Comparison: participants in the control group received usual care or were assigned to wait-list control, active control, or other conditions. Outcome: the outcomes of interest included one or more sleep-related measures. The primary outcome was insomnia severity index (ISI), while secondary outcomes included sleep onset latency (SOL), wake after sleep onset (WASO), number of awakenings (NWAK), total sleep time (TST), sleep quality (SQ), and sleep efficiency (SE). Sleep-related outcomes were assessed using subjective methods, such as self-reported sleep diaries and sleep scales, such as the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). Additionally, studies employing objective measurement methods such as wearable devices, polysomnography, and actigraphy were also included. Study design: systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Studies were excluded if they had the following characteristics: (1) participants with shift work that disrupted the establishment of regular sleep patterns, those with acute psychiatric disorders, or those diagnosed with cancer; (2) digital therapeutics were not the key intervention of interest; (3) sleep-related outcomes were not reported; (4) inappropriate study design, such as a scoping review, literature review, or original study (e.g., randomized controlled trial); (5) were not published in a peer-reviewed journal or database; or were conference abstracts (except for full conference articles); and (6) the full text was not accessible.

Study selection and data extraction

Database search results were imported into Zotero, and duplicates were removed. Based on the inclusion criteria, two rounds of literature screening were conducted by three independent reviewers. In the first round, two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, and any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by all three reviewers. In the second round, full-text screening was again performed independently by two reviewers, and any disagreements were resolved by discussion among the three reviewers. The reliability of both rounds of screening was calculated through consistency checks.

Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers to ensure accuracy and consistency. During the data extraction process, all relevant information was extracted from the included studies and recorded in a standardized data table. The main data extracted included the following: first author, year of publication, number of original studies in the review, sample size and characteristics (e.g., age and population type), type of intervention and control groups, measured outcomes, subgroup details, model type (random effect or fixed effect), standard deviation type, confidence interval (CI), p value, I² statistic, and heterogeneity p value. The data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers, and any discrepancies were resolved through comparison of results. In case of persistent disagreement, a third reviewer served as an arbitrator.

Risk of bias

To assess the quality and risk of bias of the included studies, this umbrella review used the AMSTAR 2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2) tool60,61. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included systematic reviews and meta-analyses. AMSTAR 2 is a widely used tool specifically designed to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. It consists of 16 items, divided into 7 key items and 9 non-key items, covering various aspects such as study design, data analysis, and publication bias. Each item was rated as “yes”, “partially yes”, “no”, or “not applicable”. Reviews were categorized as high confidence (0 key weaknesses and < 3 non-key weaknesses), moderate confidence (1 key weakness and ≤3 non-key weaknesses), low confidence (>1 key weakness and ≤3 non-key weaknesses), or very low confidence (>1 key weakness and >3 non-key weaknesses).

Data synthesis and analysis

All analyses were carried out using Stata version 17.0 and R version 4.3.1 with the ‘meta’ and ‘forestploter’ packages, applying appropriate statistical methods to address heterogeneity, bias, and effect estimation. To synthesize the results of various studies, the Umbrella Review and Meta-Meta-Analysis used standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) to express the overall effect size. The effect size was classified as large (SMD > 0.8), medium (SMD 0.5–0.8), or small (SMD 0.2–0.5)62. Common methods for calculating SMD include Cohen’s d, Hedges’ g, and Glass’ s D. Given that the calculation characteristics of Hedges’ g may cause variations in effect direction due to the comparison order of the treatment group and the control group, potentially leading to inconsistencies in effect direction, this study aligned the effect direction across studies by reversing values and employed Hedges’ g for SMD calculation.

The study applied the I² index to assess heterogeneity. If I² was greater than 75% and p was less than 0.05, it indicated significant heterogeneity, and using a random effects model was appropriate. Otherwise, a fixed effects model would be adopted. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the impact of individual studies on the overall effect size and heterogeneity, helping to identify studies that may have a disproportionate influence on the results, and thereby enhancing our understanding of the sources of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were explored using leave-one-out method and assessed the impact of studies on the pooled effect size based on two criteria: either the effect estimate fell outside the 95% confidence interval of the overall pooled effect after removing a study, or the pooled effect estimate significantly deviated from the overall estimate after removal. If the results remained consistent after excluding certain studies, it indicated that the research results would be robust and reliable. In addition, this study also conducted multiple subgroup analyses to further explore factors that may affect the effectiveness of digital therapeutics on insomnia. Subgroup analyses were of great value in identifying potential sources of heterogeneity in treatment effects and understanding how different intervention strategies, patient characteristics, and study designs regulate treatment outcomes. Specifically, subgroup analyses included different sleep outcomes, follow-up duration, control group type, and presence or absence of therapist guidance.

Study overlap and publication bias

In this study, we investigated the degree of overlap between the original studies (e.g., original randomized controlled trials) included in the systematic reviews and meta-analyses covered by the umbrella review. To measure this overlap, we employed the Corrected Coverage Area (CCA) method. Specifically, when the CCA value reached 100%, it indicated that every systematic review and meta-analysis identified in this umbrella review contained the exact same original studies. In contrast, the CCA value of 0% would suggest that the original studies included in each systematic review and meta-analysis within this umbrella review were entirely independent and unique. Based on predefined criteria, the CCA value between 0–5% was considered to reflect minimal overlap, 6–10% was categorized as moderate overlap, 11–15% as high overlap, and values exceeding 15% were regarded as very high overlap63.

Publication bias was inspected with funnel plots and tested with Egger’s test64,65. Funnel plots provided a visual representation of the relationship between effect sizes and sample sizes, where symmetry suggests minimal publication bias, and asymmetry may indicate its presence. To eliminate potential subjective interpretation and further confirm any asymmetry in the distribution, Egger’s test was applied to quantitatively assess the extent of publication bias

Data availability

Data are publicly available. The data that support the findings of this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Ford, D. E. & Kamerow, D. B. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders: an opportunity for prevention?. JAMA 262, 1479–1484 (1989).

Riemann, D. et al. Insomnia disorder: State of the science and challenges for the future. J. Sleep. Res. 31, e13604 (2022).

Daley, M., Morin, C. M., LeBlanc, M., Grégoire, J.-P. & Savard, J. The economic burden of insomnia: direct and indirect costs for individuals with insomnia syndrome, insomnia symptoms, and good sleepers. Sleep 32, 55–64 (2009).

Ohayon, M. M. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep. Med. Rev. 6, 97–111 (2002).

Benjafield, A. V. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of insomnia: a systematic literature review-based analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev. 82, 102121 (2025).

Lin, Y.-H., Chiang, T.-W. & Lin, Y.-L. Increased Internet Searches for Insomnia as an Indicator of Global Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Multinational Longitudinal Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e22181 (2020).

Zitting, K.-M. et al. Google Trends reveals increases in internet searches for insomnia during the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) global pandemic. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 17, 177–184 (2021).

van Straten, A. & Lancee, J. Digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: the answer to a major public health issue?. Lancet Digit. Health 2, e381–e382 (2020).

Morin, C. M., Inoue, Y., Kushida, C., Poyares, D. & Winkelman, J. Endorsement of European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia by the World Sleep Society. Sleep. Med. 81, 124–126 (2021).

Edinger, J. D. et al. Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 17, 255–262 (2021).

Riemann, D. et al. The European Insomnia Guideline: An update on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia 2023. J. Sleep. Res. 32, e14035 (2023).

Ree, M., Junge, M. & Cunnington, D. Australasian Sleep Association position statement regarding the use of psychological/behavioral treatments in the management of insomnia in adults. Sleep. Med. 36, S43–S47 (2017).

Shaffer, K. M. et al. Effects of an Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia program on work productivity: a secondary analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 55, 592–599 (2021).

Savard, J., Ivers, H., Morin, C. M. & Lacroix, G. Video cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in cancer patients: A cost-effective alternative. Psycho-Oncol. 30, 44–51 (2021).

Simon, L. et al. Help for insomnia from the app store? A standardized rating of mobile health applications claiming to target insomnia. J. Sleep. Res. 32, e13642 (2023).

Chiu, Y.-H., Lee, Y.-F., Lin, H.-L. & Cheng, L.-C. Exploring the role of mobile apps for insomnia in depression: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e51110 (2024).

Arroyo, A. C. & Zawadzki, M. J. The Implementation of behavior change techniques in mhealth apps for sleep: systematic review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 10, e33527 (2022).

Cajita, M. I., Kline, C. E., Burke, L. E., Bigini, E. G. & Imes, C. C. Feasible but not yet efficacious: a scoping review of wearable activity monitors in interventions targeting physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 7, 25–38 (2020).

Spina, M.-A. et al. Does providing feedback and guidance on sleep perceptions using sleep wearables improve insomnia? Findings from “Novel Insomnia Treatment Experiment”: a randomized controlled trial. SLEEP 46, zsad167 (2023).

Takeuchi, H. et al. The effects of objective push-type sleep feedback on habitual sleep behavior and momentary symptoms in daily life: mhealth intervention trial using a health care internet of things system. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 10, e39150 (2022).

Lee, S., Oh, J. W., Park, K. M., Lee, S. & Lee, E. Digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. npj Digit. Med. 6, 52 (2023).

Shin, J. C., Kim, J. & Grigsby-Toussaint, D. Mobile phone interventions for sleep disorders and sleep quality: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 5, e131 (2017).

Werner-Seidler, A., Johnston, L. & Christensen, H. Digitally-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy for youth insomnia: A systematic review. Internet Interven.11, 71–78 (2018).

de Zambotti, M., Goldstone, A., Colrain, I. M. & Baker, F. C. Insomnia disorder in adolescence: Diagnosis, impact, and treatment. Sleep Medicine Reviews 39, 12–24 (2018).

Vedaa, Ø. et al. Effects of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia on insomnia severity: a large-scale randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digital Health 2, e397–e406 (2020).

Bai, N., Cao, J., Zhang, H., Liu, X. & Yin, M. Digital cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with insomnia and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 31, 654–667 (2024).

Ferguson, T. et al. Effectiveness of wearable activity trackers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Digit. Health 4, e615–e626 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Effectiveness of telemedicine on common mental disorders: An umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 159, 108325 (2024).

Hasan, F. et al. Comparative efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. Rev. 61, 101567 (2022).

Simon, L. et al. Comparative efficacy of onsite, digital, and other settings for cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 13, 1929 (2023).

Tsai, H.-J. et al. Effectiveness of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Young People: Preliminary Findings from Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JPM 12, 481 (2022).

Knutzen, S. M. et al. Efficacy of eHealth versus in-person cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: systematic review and meta-analysis of equivalence. JMIR Ment. Health 11, e58217 (2024).

Seyffert, M. et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy to treat insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 11, e0149139 (2016).

Lin, W., Li, N., Yang, L. & Zhang, Y. The efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PeerJ 11, e16137 (2023).

Cheng, S. K. & Dizon, J. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother. Psychosom. 81, 206–216 (2012).

Jung, S., Takeuchi, T., Kitahara, M., Tsutsumi, A. & Nomura, K. Effectiveness of mobile applications in improving insomnia symptoms among adults from multi-community: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine 119, 357–364 (2024).

Zhang, H., Yang, Y., Hao, X., Qin, Y. & Li, K. Effects of digital sleep interventions on sleep and psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. 110, 190–200 (2023).

Soh, H. L., Ho, R. C., Ho, C. S. & Tam, W. W. Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep. Med. 75, 315–325 (2020).

Zachariae, R., Lyby, M. S., Ritterband, L. M. & O’Toole, M. S. Efficacy of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia – A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep. Med. Rev. 30, 1–10 (2016).

Yu, H., Zhang, Y., Liu, Q. & Yan, R. Efficacy of online and face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of neurological insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med 10, 10684–10696 (2021).

Xu, D., Li, Z., Leitner, U. & Sun, J. Efficacy of remote cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia in improving health status of patients with insomnia symptoms: a meta-analysis. Cogn. Ther. Res 48, 177–211 (2024).

Deng, W. et al. eHealth-Based Psychosocial Interventions for Adults With Insomnia: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e39250 (2023).

Scott, A. M. et al. Telehealth versus face-to-face delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Telemed Telecare 1357633X231204071 https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X231204071 (2023).

Linardon, J., Anderson, C., McClure, Z., Liu, C. & Messer, M. The effectiveness of smartphone app-based interventions for insomnia and sleep disturbances: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep. Med. 122, 237–244 (2024).

Amani, O., Mazaheri, M. A., Malekzadeh Moghani, M. & Zarani, F. Effectiveness of internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Rhythm Res. 54, 647–663 (2023).

Ye, Y. et al. Internet-based cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i): a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 6, e010707 (2016).

Forma, F. et al. Network meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of a prescription digital therapeutic for chronic insomnia to medications and face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy in adults. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 38, 1727–1738 (2022).

Sharafkhaneh, A. et al. Telemedicine and insomnia: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Med. 90, 117–130 (2022).

Salvemini, A. et al. Insomnia and Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in Elderly People: A Systematic Review. Med. Sci. 7, 70 (2019).

McLay, L., Sutherland, D., Machalicek, W. & Sigafoos, J. Systematic Review of Telehealth Interventions for the Treatment of Sleep Problems in Children and Adolescents. J Behavioral Education 29, 222–245 (2020).

Crane, S. J., Ganesh, R., Post, J. A. & Jacobson, N. A. Telemedicine consultations and follow-up of patients with COVID-19. Mayo Clin. Proc. 95, S33–S34 (2020).

Hsieh, C., Rezayat, T. & Zeidler, M. R. Telemedicine and the management of insomnia. Sleep. Med. Clin. 15, 383–390 (2020).

Edemann-Callesen, H. et al. Use of melatonin in children and adolescents with idiopathic chronic insomnia: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and clinical recommendation. eClinicalMedicine 61, 102048 (2023).

Do, D. Trends in the use of medications with insomnia side effects and the implications for insomnia among US adults. J. Sleep. Res. 29, e13075 (2020).

Nam, H. et al. Predictors of dropout in university students participating in an 8-week e-mail-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia intervention. Sleep. Breath. 27, 345–353 (2023).

Storman, M., Storman, D., Jasinska, K. W., Swierz, M. J. & Bala, M. M. The quality of systematic reviews/meta-analyses published in the field of bariatrics: A cross-sectional systematic survey using AMSTAR 2 and ROBIS. Obes. Rev. 21, e12994 (2020).

Jackson, C. L., Patel, S. R., Jackson, W. B., Lutsey, P. L. & Redline, S. Agreement between self-reported and objectively measured sleep duration among white, black, Hispanic, and Chinese adults in the United States: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Sleep 41, zsy057 (2018).

Liberati, A. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62, e1–e34 (2009).

Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J. & Hayward, R. S. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J. Club 123, A12–A13 (1995).

Shea, B. J. et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 7, 10 (2007).

Shea, B. J. et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62, 1013–1020 (2009).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd Ed. (Routledge, 1988).

Pieper, D., Antoine, S.-L., Mathes, T., Neugebauer, E. A. M. & Eikermann, M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 368–375 (2014).

Ioannidis, J. P. A. & Trikalinos, T. A. The appropriateness of asymmetry tests for publication bias in meta-analyses: a large survey. CMAJ 176, 1091–1096 (2007).

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72371111, 72001087).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Can Li: Writing (original draft), Methodology, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Qiyun Luo: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Hong Wu: Writing (review & editing), Supervision, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Luo, Q. & Wu, H. Digital therapeutics for insomnia: an umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis. npj Digit. Med. 8, 554 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01946-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01946-y