Abstract

This paper aims to build a model that can Segment Anything in 3D medical images, driven by medical terminologies as Text prompts, termed as SAT. Our main contributions are three-fold: (i) We construct the first multimodal knowledge tree on human anatomy, including 6502 anatomical terminologies; Then, we build the largest and most comprehensive segmentation dataset for training, collecting over 22K 3D scans from 72 datasets, across 497 classes, with careful standardization on both image and label space; (ii) We propose to inject medical knowledge into a text encoder via contrastive learning and formulate a large-vocabulary segmentation model that can be prompted by medical terminologies in text form. (iii) We train SAT-Nano (110M parameters) and SAT-Pro (447M parameters). SAT-Pro achieves comparable performance to 72 nnU-Nets—the strongest specialist models trained on each dataset (over 2.2B parameters combined)—over 497 categories. Compared with the interactive approach MedSAM, SAT-Pro consistently outperforms across all 7 human body regions with +7.1% average Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) improvement, while showing enhanced scalability and robustness. On 2 external (cross-center) datasets, SAT-Pro achieves higher performance than all baselines (+3.7% average DSC), demonstrating superior generalization ability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medical image segmentation aims to identify and delineate regions of interest (ROIs) like organs, lesions, and tissues in diverse medical images, which plays a crucial role in numerous clinical applications, such as disease diagnosis, treatment planning, and disease progression tracking1,2,3,4,5, as well as in medical research6,7. Traditionally, radiologists perform manual segmentation to measure volume, shape, and location in a slice-wise manner, which is both time-consuming and challenging to scale with the growing volume of medical data. Consequently, there is a pressing need for automated and robust medical image segmentation methods in clinical settings, to enhance efficiency and scalability.

Recent advancements in medical image analysis have been marked by a surge in deep learning. These developments have yielded a spectrum of segmentation models, each trained for specific tasks3,8,9,10,11,12,13, often referred to as ‘specialist’ models. While these models demonstrate impressive segmentation capabilities, their major drawback lies in their narrow specialization. Designed and optimized for distinct ROIs and imaging modalities, these models14,15,16,17,18,19 require distinct preprocessing methods for each dataset. As a result, they often fall short in diverse and dynamic clinical environments, where adaptability to new conditions and imaging techniques is essential.

There is a growing interest in developing foundation models for medical image segmentation20,21, by adapting the pre-trained segment anything model (SAM)22 models from the computer vision community. However, while transferring to medical scenarios, these models trained on natural images suffer from fundamental limitations: (i) models typically perform 2D slice segmentation, which is later fused into 3D volumes through post-processing. This approach overlooks the crucial contextual information in 3D radiological imaging; (ii) models often require point or box inputs as prompts, thus are interactive segmentation models, requiring considerable manual effort for use in practice; (iii) models suffer from significant domain gaps, from image statistics to domain-specific medical knowledge.

In this paper, we present the first knowledge-enhanced foundation model for 3D medical volume segmentation, with medical terminology as text prompt, termed as SAT. In practice, our model can effectively take 3D volumes as visual inputs along with text prompts to seamlessly tackle various medical image segmentation tasks, across modalities, anatomies, and body regions. As illustrated in Fig. 1, our proposed method distinguishes itself from previous medical segmentation paradigms, that can be seamlessly applied to clinical practice or integrated with any large language model. Specifically, we make the following contributions in Fig. 2:

In contrast to conventional specialist models (a) that develop specialized solutions for each task, or recently proposed interactive segmentation foundation models (b) relying on real-time human interventions, segment anything by text (SAT) directly takes 3D volumes as inputs, and uses text as prompts to perform a wide array of medical image segmentation tasks across different modalities, anatomies, and body regions (c). It can be easily applied to clinics or seamlessly integrated with any agent-based large language model.

On dataset construction, we construct a knowledge tree on anatomy concepts and definitions throughout the human body. On the visual side, we curate over 22K 3D medical image scans with 302K anatomical segmentation annotations, covering 497 categories from 72 publicly available medical segmentation datasets, termed as SAT-DS (Fig. 2). To the best of our knowledge, SAT-DS represents the largest and most comprehensive collection of public 3D medical segmentation datasets. To achieve this goal, we have invested significant effort in standardizing datasets and unifying annotation labels, paving the way for training a large-vocabulary segmentation foundation model.

On architecture design and training strategy, we build a large-vocabulary segmentation foundation model that enables flexible segmentation across a spectrum of medical imaging modalities and anatomies, with text prompts. Specifically, we adopt knowledge-enhanced representation learning, leveraging textual anatomical knowledge and atlas segmentation of specific anatomical structures to train the visual-language encoders. Through this training process, the visual features of these anatomical structures are aligned with their corresponding text descriptions in the latent space, which is validated to boost the segmentation performance, especially in a long-tail distribution. Subsequently, the text embeddings of anatomy/abnormality are treated as queries in a Transformer-based architecture, iteratively attending to the visual features to update queries for precise segmentation of the queried target. To meet requirements from different computational resources, we train two models of varying sizes, namely, SAT-Nano and SAT-Pro, and validate the effectiveness of scaling model sizes.

On experiment evaluation, we devise comprehensive metrics for large-vocabulary medical segmentation across various aspects, including region-wise average, organ-wise average, and dataset-wise average. Through extensive internal and external experiments, we demonstrate that:

-

Building on the unprecedented dataset collection, SAT is able to handle a wide range of downstream segmentation tasks with medical terminologies as text prompts, simplifying the training and deployment procedure for conventional specialist models. On internal evaluation, SAT-Pro shows comparable overall performance to 72 nnU-Net models—the strongest specialist models that are specialized and trained individually on each dataset—over 497 categories, while using only 20% of their combined model parameters (447M vs. 2.2B+).

-

Driven by text prompts, SAT outlines a novel paradigm for segmentation foundation model, as opposed to previous interactive approaches that rely on spatial prompts. This could save tremendous manual efforts from prompting in clinical applications. On performance, SAT-Pro consistently outperforms the state-of-the-art interactive model MedSAM across 7 human body regions, while being robust to targets with ambiguous spatial relationships.

-

Compared to BiomedParse23, a concurrent model on text-prompted biomedical image segmentation, SAT-Pro not only exhibits superior performance on 29 out of 30 categories, but also showcases a significantly broader capability on radiology images.

-

On external evaluation, SAT-Pro delivers the best results across both external validation datasets, and surpasses all baselines including specialist and generalist models, highlighting its strong generalization capabilities as a foundation model.

-

The text-prompted feature and large vocabulary of SAT make it a powerful out-of-the-box agent for language model. We show SAT can be seamlessly integrated with any large language models, such as GPT-424, automatically providing grounding ability in diverse clinical scenarios. This potentially extends the application diagram of medical segmentation models, and advance generalist medical artificial intelligence.

Results

We propose Segment Anything with Text (SAT), a large-vocabulary segmentation foundation model for 3D medical images. The objective is to handle a wide range of heterogeneous tasks using text prompts. It includes 497 anatomical targets across 8 regions and various lesions of the human body, assembled from 72 distinct datasets. To balance the computational cost and performance, we train and evaluate two variants SAT-Pro and SAT-Nano.

In this section, we detail the experiment results, where SAT is comprehensively evaluated against three categories of methods: (i) specialist models, which are optimized and trained individually for each dataset, following the conventional mainstream practice in medical image segmentation. We choose nnU-Nets16, SwinUNETR19, and U-Mamba14 for comparison, as they are widely adopted representatives for CNN-based, Transformer-based, and Mamba-based architecture, respectively; (ii) interactive segmentation models, which have been recently investigated to provide semi-automatic segmentation with spatial prompts. We choose MedSAM20 as a typical and state-of-the-art baseline; (iii) text-prompted segmentation models, which represent a paradigm shift from the previous two, capable of performing automatic segmentation across a wide range of tasks with text prompts. BiomedParse23 is a concurrent work to ours and compared in this study.

The evaluations are conducted on both internal and external datasets. Specifically, we split each dataset in SAT-DS into train and test splits in 8:2 ratio, a combination of these test splits is used for internal evaluation, i.e., in-domain data. When comparing to off-the-shelf models, we tailor the scope of datasets to accommodate their varying capabilities, to avoid overlapping the train and test data. The external evaluation is conducted on two very recently published datasets, namely, AbdomenAtlas 1.125 and LiQA26, as they are excluded from SAT-DS and not used in training any of these methods. This simulates the scenario where the models are tested on multi-center images. Note that this does not involve new classes, as the segmentation targets in the human body are relatively limited and fixed.

We present evaluation results from various aspects, including region-wise, class-wise, and dataset-wise, to give a deep understanding of the models’ performance on large-scale segmentation. Note that class-wise and region-wise evaluations are computed by averaging the results from different datasets. For instance, the performance metrics for the “brainstem” in CT images represent the macro average from models trained on datasets, like “HAN Seg”, “PDDCA”, and “SegRap2023 Task 1”, that all include annotations for this anatomical class. Detailed experiment settings can be found in Section “Evaluation protocols”.

The following sections start with experiments on internal datasets in Sections ”Comparison with specialist models on automatic segmentation”, “Comparison with interactive segmentation foundation model”, and “Compare with text-prompted segmentation foundation model”, with more detailed results available in the “Detailed internal evaluation results” Section in the Supplementary. Then, we present the results of different methods on external datasets in Section “Evaluation on external datasets”, with more detailed results available in the “Detailed external evaluation results” Section in the Supplementary. Finally, we demonstrate the impact of knowledge injection in Section “Ablation study on text encoder”, and SAT’s potential application scenarios in Section “Qualitative results—SAT as an interface between language and segmentation”. Additional ablation experiments are provided in the “Extended ablation studies” Section in the Supplementary; Model calibration analysis is presented in the “Calibration analysis” Section in the Supplementary.

Comparison with specialist models on automatic segmentation

In this experiment setting, we compare with specialist models (nnU-Nets, U-Mamba, SwinUNETR) on all 72 datasets in SAT-DS as internal evaluation. All specialist models are trained with optimized configuration on each dataset with official codes. While both SAT-Pro and SAT-Nano are trained and evaluated on all datasets as one model. Note that, unless otherwise stated, SAT-Pro and SAT-Nano are trained on all 72 datasets of SAT-DS throughout the following text.

Figure 3a and Supplementary Table 3 shows the region-wise results on 8 regions of human body, including “Brain”, “Head and Neck”, “Thorax”, “Abdomen”, “Pelvis”, “Spine”, “Upper Limb”, and “Lower Limb”, as well as “Lesion”, in terms of dice similarity coefficient (DSC) and normalized surface distance (NSD), respectively. Classes existing in multiple regions are specifically grouped as “whole body”.

Results are merged by different human body regions and lesions. a Box plots on DSC and NSD results. The center line within each box indicates the median value; the bottom and top bounds indicate the 25th percentiles and 75th percentiles, respectively. The mean value is marked with a plus sign. The whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range. Outlier classes are plotted as individual dots. b Comparison between SAT-Pro and the most competitive specialist models nnU-Nets on performance. c Comparison between SAT and specialist models on model size and capability range. SAT has a much smaller model size compared to the ensemble of specialist models, while capable of segmenting 497 targets in one model. By comparison, each specialist model can only segment 12 targets on average.

Despite having been proposed for a few years, nnU-Nets remains the best-performing specialist model overall. As a generalist model, SAT-Pro consistently outperforms the most competitive baseline nnU-Nets in four regions: head and neck, thorax, upper limb, and lower limb. On average, DSC of all 497 categories, SAT-Pro shows comparable performance to nnU-Nets (paired t-test p > 0.09) and U-Mamba (p > 0.13), while surpassing SwinUNETR significantly (p < 2 × 10−5).

Figure 3b, c provide another view on the above results, where it can be seen that SAT-Pro shows comparable segmentation performance to the 72 nnU-Nets, while being significantly smaller in size and more capable; for example, SAT-Pro is approximately 1/5 of the ensemble of nnU-Nets, and is able to handle 497 classes, in contrast to each specialist model handling an average of only 12 classes.

We further finetune SAT-Pro on each dataset, and report the region-wise results in Supplementary Table 3, denoted as SAT-Ft. SAT-Ft shows notable improvement over SAT-Pro on all the regions and lesions. On average performance over all categories, it outperforms U-Mamba on both DSC (p < 2 × 10−9) and NSD (p < 0.01), and nnU-Nets on NSD (p < 6 × 10−9). This indicates that SAT can serve as a strong pre-trained model for further adaptation.

We present dataset-wise results in Supplementary Tables 5, 6, 7, and 8, and more detailed class-wise results in Supplementary Tables 9, 10, 11, and 12;

Comparison with interactive segmentation foundation model

In this section, we compare with MedSAM, an out-of-the-box interactive segmentation method trained on large-scale data. Due to inconsistent training data, we focus the internal evaluation on all the 32 datasets (out of 72) that were involved in training MedSAM for fair comparison. Note that even though these datasets are included in MedSAM’s training, we are unable to align the train-test splits. This means our test set might have been leaked in MedSAM’s training. We report three results: (i) simulate box prompts based on ground truth segmentation, using the minimum rectangle covering the ground truth (denoted as Tight), i.e., the most accurate prompts; (ii) randomly shift each box corner by up to 8% of the image resolution (denoted as Loose), i.e., allowing errors to some extent; (iii) directly use the tight box prompts as prediction (denoted as Oracle Box), i.e., the input baseline for MedSAM.

Figure 4a and Supplementary Table 4 show the region-wise results for all methods. Notably, SAT-Pro consistently outperforms MedSAM across all human body regions, even when MedSAM is prompted with the most accurate box (Tight), and achieves significantly superior average performance over all categories (paired t-test p < 2 × 10−9). For lesion segmentation, SAT-Pro underperforms MedSAM (Tight) due to the small lesion size, where the box prompts provide very strong priors to MedSAM, as evidenced by the oracle box even outperforming MedSAM’s output on DSC score. When perturbing the box prompts, MedSAM (Loose) shows significant performance drops across all regions and metrics.

Results are merged by different human body regions and lesions. a Histograms on DSC and NSD results. b Scatter plots comparing the performance improvement of SAT-Pro over MedSAM on different segmentation targets (DSC score), with two irregularity metrics: convex ratio and oracle box DSC. Each point represents an anatomical structure or lesion, with a fitted line illustrating the trend. c Average prompt numbers required by MedSAM to segment a target in 3D radiology scan, averaged over different human body regions. d Quantitative results of MedSAM and SAT-Pro on myocardium (upper row) and colon cancer (lower row). The ground truth and segmentation masks are painted in red, while the box prompts of MedSAM are plotted in black. The DSC score is calculated in a slice-wise manner. H& N head and neck.

On class-wise results, in Fig. 4b, we present the performance difference between SAT-Pro and MedSAM on each category, with respect to the spatial irregularity of regions. Inspired by BiomedParse23, we define spatial irregularity with two factors: the ratio of ground truth to the tightest convex, denoted as “Convex Ratio”; the DSC score between oracle box prompt and ground truth, denoted as “Oracle Box DSC”. We observe that SAT-Pro achieves greater improvement on targets with more irregular shapes, while MedSAM outperforms on some relatively regular-shaped targets.

We further present qualitative results from two representative examples in Fig. 4d. The upper row shows segmentation of myocardium with a relatively irregular shape. MedSAM incorrectly includes the left heart ventricle surrounded by the myocardium. By comparison, SAT-Pro generates accurate predictions when simply prompted with the word “myocardium”. The lower row demonstrates colon cancer segmentation on a CT image. The tight box prompt to MedSAM can be viewed as an acceptable segmentation, despite its limitation as a rectangle, while MedSAM’s prediction is worse. In addition, in both cases, we observe noticeable performance drops when the box prompt contains certain deviations, i.e., MedSAM (Loose).

In Fig. 4c, we show the average number of prompts required by MedSAM to segment a target in a 3D image scan. As it only allows slice-wise segmentation and the morphology of segmentation targets varies across different body regions, the number ranges from 10+ to 60+. By contrast, as a fully automatic segmentation model for 3D radiology images, SAT requires only a single text prompt to segment the entire 3D scan. This simplicity and scalability advantage become more pronounced for multiple target segmentation.

We present dataset-wise results in Supplementary Tables 5, 6, 7, and 8, and more detailed class-wise results in Supplementary Table 13.

Compare with text-prompted segmentation foundation model

In this section, we compare with BiomedParse23, a concurrent work that proposed a segmentation tool for general 2D biomedical images prompted by text. Due to inconsistent training data, we focus the internal evaluation on all the 11 datasets (out of 72) that were involved in training BiomedParse for fair comparison. We report two results for BiomedParse: (i) Based on the ground truth, we only prompt targets present in the current slice, which follows its official evaluation setting. Similar to MedSAM, this approach avoids potential false positives on unannotated slices and thus represents performance under ideal conditions. We denote these results as BiomedParse (Oracle); (ii) Consistent with SAT, we prompt all targets available in the dataset and filter out potential false positive predictions by p-values, as suggested by the official implementation.

Figure 5a and Supplementary Table 14 present the class-wise performance of SAT and BiomedParse. Across all categories, BiomedParse (Oracle) consistently achieves higher DSC and NSD scores compared to BiomedParse. This highlights that BiomedParse is prone to generating false positive predictions when prompted with non-existing targets, likely because BiomedParse is a 2D slice segmentation model that overlooks critical information from adjacent slices. SAT-Pro consistently outperforms BiomedParse in all 30 categories except myocardium. Even compared to BiomedParse (Oracle), SAT-Pro demonstrates superior performance on 23 out of 30 categories and notably excels in overall performance. On average across all categories, both SAT-Pro and SAT-Nano significantly outperforms BiomedParse (Oracle) (paired t-test p < 7 × 10−3 for DSC and p < 2 × 10−6 for NSD).

a DSC and NSD scores. Results are merged and presented in a class-wise manner. b The number of anatomical structures and lesions SAT and BiomedParse can segment on different human body regions in radiology images, and on different imaging modalities. “Others” denotes non-radiology modalities. AG adrenal gland, HV heart ventricle, IVC inferior vena cava, LHA left heart atrium, UB urinary bladder.

Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 5b, BiomedParse is primarily designed as a segmentation tool for 2D biomedical images. In contrast, SAT, developed as a large-vocabulary segmentation model specifically for 3D radiology images, demonstrates significantly broader applicability and superior performance on 3D radiology images.

Evaluation on external datasets

Here, we aim to evaluate the generalization performance of segmentation models on images from different medical centers. As generalist models, SAT, MedSAM, and BiomedParse are directly evaluated on two unseen datasets. For specialist models, considering their customized configurations on each dataset, we systematically evaluate 21 out of 72 specialist models on target datasets for shared categories. For example, to evaluate the generalization performance on ‘lung’ in AbdomenAtlas, we use specialist models trained on CT-ORG and LUNA16, as they all involve this class, and then average the results. The details of the overlapped label spaces are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. To maintain performance for specialist models, the pre-processing of target datasets is kept the same as the source dataset in evaluation.

We report DSC and NSD results in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 15, with the following observations: (i) For specialist models, U-Mamba achieves more competitive results than nnU-Nets on both DSC and NSD scores, while SwinUNETR remains the worst; (ii) For generalist models for 2D images, MedSAM (Tight) consistently outperforms BiomedParse (Oracle) on all categories, implying that accurate box prompts provide strong priors when extending to out-of-domain images; (iii) SAT-Pro achieves the best performance on average over all categories, exceeding the second-best candidate MedSAM by 2.9 on DSC (paired t-test p < 7 × 10−4) and 5.52 on NSD (p < 9 × 10−6). Meanwhile, SAT-Pro consistently outperforms the specialist models on all categories in terms of NSD score and on 17 out of 19 categories in terms of DSC score.

Ablation study on text encoder

As will be illustrated in Section “Multimodal knowledge injection”, to build a large-vocabulary segmentation model driven by text prompts, we inject domain knowledge into the text encoder to provide precise prompts for the target of interest, i.e., the encoding of terminology. In this section, we conduct experiments and discuss the effect of domain knowledge. To save computational cost, the experiment have been conducted on SAT-DS-Nano dataset.

Specifically, we train four SAT-Nano variants with different text encoders: (i) BERT-Base, a prevalent text encoder in natural language processing, but not specifically fine-tuned on medical corpora; (ii) the text encoder of CLIP, a state-of-the-art model pretrained on 400M image-text pairs and widely used in vision-language tasks; (iii) the state-of-the-art text encoder for medical retrieval tasks, e.g., MedCPT; (iv) the text encoder pre-trained on our multimodal medical knowledge graph, as illustrated in Section “Multimodal knowledge injection”. For all variants, we use U-Net as the visual backbone and denote them as U-Net-BB, U-Net-CLIP, U-Net-CPT, and U-Net-Ours.

As shown in Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 17, the performance of U-Net-BB, U-Net-CLIP, and U-Net-CPT is close. Overall, U-Net-BB performs the worst, while U-Net-CPT slightly exceeds others on DSC (+0.1) and U-Net-CLIP slightly exceeds others on NSD (+0.29) scores averaged over all classes. By contrast, U-Net-Ours surpasses all other variants consistently across all regions, with notable margins on both DSC (+1.54) and NSD (+2.36) scores on average over all classes. This demonstrates the effectiveness of our proposed multimodal knowledge injection.

We further investigate the effect on different classes. As illustrated in Fig. 8a, b, the 429 classes in SAT-DS-Nano typically follow a long-tail distribution. The 10 “head” classes account for 12.75% of the annotations in SAT-DS-Nano. In contrast, the 150 classes with minimum annotations account for only 3.25%, even though they comprise 34.97% of the 429 classes. We compare U-Net-Ours, U-Net-CPT, U-Net-CLIP, and U-Net-BB on the “head” classes, “tail” classes, and the rest (denoted as “middle” classes). In Fig. 8c, the performance of the model variants drops from head to tail classes, showing that the long-tailed distribution poses a significant challenge for medical segmentation. Using our proposed knowledge-enhanced text encoder, U-Net-Ours achieves the best performance across all three scenarios. On “head” classes, it outperforms the second-best variant by 0.71 on DSC and 2.44 on NSD. On “tail” classes, the improvement is even more pronounced. For more detailed results on each class and dataset, we refer the reader to Supplementary Tables 22, 23, 24, and 25.

In addition to segmentation performance, we evaluate the text encoders on “concept-to-definition” retrieval using human anatomy knowledge. In total, we collect 6502 anatomy concept-definition pairs. We find that the Recall@1 (R1) for BERT-Base is only 0.08%, suggesting it can hardly understand these anatomy concepts and possesses almost no domain knowledge. The R1 is 4.13% for CLIP and 11.19% for MedCPT. Though this is a significant improvement over BERT-Base, they still struggle to distinguish these concepts. By contrast, our proposed text encoder achieves 99.18% R1, indicating that the knowledge is successfully injected into the text embedding for each anatomy concept.

Qualitative results—SAT as an interface between language and segmentation

Thanks to the text-driven features of SAT, it can be seamlessly applied as an interface between natural language and segmentation, i.e., acting as a high-performance and efficient agent for language models. Here, we demonstrate three potential applications in Fig. 9: (i) We demonstrate a scenario where GPT-424 analyzes and extracts the anatomical targets of interest from a real clinical report and prompts SAT to segment them on the clinical image. As can be seen in the upper row, the targets in reports can be well detected by the language model (GPT-4) and commendably segmented by SAT-Pro, which provides visual cues for the clinical report and enhances its interpretability; (ii) We show that SAT can help LLMs handle segmentation requests in free-form conversations with any users. The LLM can easily recognize these requests and leverage SAT to deliver precise segmentation results, which greatly extends the conversational interface. (iii) We explore more complicated situations, where SAT can ground the lesions based on comprehensive analysis of radiology images as well as contextual EHR data such as patient complaints, establishing a complete automated pipeline from diagnosis to segmentation.

Combining SAT-Pro and GPT4, we demonstrate three potential applications: providing visual clues for clinic reports, handling segmentation requests in free-form conversation, and an automated pipeline from diagnosis to segmentation. For each application, the specific prompt template in use is shown. The [TERMINOLOGY LIST] contains anatomical structures that SAT can segment, which can be customized based on different clinicians' requirements (e.g., in demo 3, we only provide lesion categories). While the other bolded components in the templates (e.g., [MODALITY]) are variable placeholders that need to be filled with case-specific information. We show one example case for each application in the leftmost column. Target names are extracted from GPT's text output by string parsing, and serve as the exact text prompts for SAT. We extract representative slices from the image volume for demonstration.

Discussion

Developing specialist models on individual tasks has been the dominant solution for medical image segmentation for years15,16,19,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. In this paper, we aim to build a large-vocabulary, effective, and flexible medical segmentation foundation model by training on an unprecedented dataset collection and driven by knowledge-enhanced text prompts. The significance of the proposed SAT is demonstrated through multiple dimensions.

First, our work represents an important step towards a universal segmentation model in medical scenarios. Despite the diverse images and segmentation targets from different clinical scenarios, SAT can flexibly handle them within a single generalist model, effectively replacing the need for dozens of specialist models. Through comprehensive internal evaluation, SAT-Pro has demonstrated competitive results against the ensemble of 72 specialist models, achieving comparable performance to nnU-Net and U-Mamba, and superior performance to SwinUNETR. Remarkably, SAT-Pro achieves this with a model size reduced to 20% or less of the ensemble, greatly improving efficiency. When evaluating on external multi-center datasets, SAT-Pro exhibits advanced generalization ability compared to all specialist models, highlighting its excellent cross-center transferability. With dataset-specific fine-tuning, SAT-Ft can further improve the performance, thus balancing the clinical requirements between generalist solutions and specialist models.

Second, as an automatic method prompted by text, SAT offers an alternative approach to recent works, such as interactive segmentation foundation models20,38. Through both qualitative and quantitative comparisons, SAT demonstrates enhanced segmentation accuracy and robustness, particularly on targets with irregular shapes. Unlike interactive methods that rely on spatial prompts and may suffer from inaccurate prompts, leading to performance fluctuations, SAT can effectively automate segmentation on 3D images with text prompts, significantly reducing user inference time and associated costs. In addition, compared to our concurrent work on text-prompted 2D segmentation foundation model, namely BiomedParse23, SAT demonstrates significantly broader applicability in 3D radiology images and consistently outperforms it in both in-domain and out-of-domain scenarios.

Third, our work implies that scaling laws—observed in large language models—also apply to large-vocabulary medical segmentation. In this work, we build SAT-Nano (110M) and SAT-Pro (447M). In both region-wise and class-wise evaluations, SAT-Pro shows a clear performance boost over SAT-Nano, outperforming the latter on most regions and classes. These findings indicate a promising way to continuously improve the performance of segmentation foundation models.

Fourth, we construct the first multimodal knowledge graph on human anatomy and demonstrate that knowledge injection can significantly improve segmentation performance, particularly for ‘tail’ classes. As the scope of medical segmentation expands to include an increasing number of targets, the long-tail problem will become more pronounced, underscoring the critical importance of knowledge enhancement in addressing this challenge.

Lastly, SAT can be used as an agent to bridge language and segmentation. In Section “Qualitative results—SAT as an interface between language and segmentation”, we show that SAT can be applied to segment targets based on the output from language models and support visual grounding across various clinical scenarios. This highlights the potential of SAT as a high-performance, efficient, and out-of-the-box tool agent, seamlessly collaborating with ever-evolving large language models. In addition, SAT has recently been applied to provide comprehensive grounding annotations for medical visual-language datasets in a scalable manner39,40.

As one of the first exploratory works in this field, several limitations remain to be addressed in our work, and we propose the following future works: (i) The performance of SAT-Pro still lags behind some specialist models, e.g., nnU-Nets, in some region. Further scaling up the model can be a promising direction; (ii) Although SAT is capable of segmenting 497 types of targets on medical images, its generalization ability to unseen categories (including unseen lesions/pathologies) remains limited. Inspired by recent advances in language-grounded segmentation for natural images and videos41,42,43,44, exploring open vocabulary segmentation in medical imaging represents a promising direction for future work; (iii) For practical deployment, while our current inference speed is suitable for clinical use (as shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), further optimization for standard clinical hardware remains important; We will explore approaches for more efficient deployment, such as our subsequent work on knowledge distillation45; (iv) Although SAT-DS includes datasets from multiple countries/regions (United States, Europe, China, Africa, etc.), distribution biases still persist. Many regions remain uncovered, and the dataset is heavily skewed toward adult populations with limited pediatric/fetal data (e.g., FETA2022). These demographic imbalances may affect model generalization across different populations and age groups, necessitating bias mitigation strategies in future work.

Methods

In this section, we first describe the two types of data collected to build SAT: multimodal domain knowledge (Section “Domain knowledge”) and medical segmentation data (Section “Segmentation dataset”). Based on them, we detail the development of SAT, starting with the task formulation (Section “Large-vocabulary segmentation prompted by text”), then the multimodal knowledge injection (Section “Multimodal knowledge injection”) and segmentation training (Section “Segmentation training”). Finally, we present the evaluation settings, including the datasets (Section “Evaluation datasets”), baselines (Section “Baselines”), protocols (Section “Evaluation protocols”), and metrics (Section “Evaluation metrics”).

Domain knowledge

To acquire textual knowledge, we mainly exploit two sources of domain knowledge: the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS)46, a comprehensive medical knowledge graph consisting of concept definitions and their interrelations; search engines, which are prompted to organize knowledge into a graph of the same format, specifically refined for the human anatomy corpus. Regarding visual knowledge, we have compiled 72 medical segmentation datasets, creating an atlas that covers over 497 anatomical structures of the human body. Examples from these sources are illustrated in Fig. 10a, b. In the following, we detail each knowledge source in sequence.

a Segmentation datasets provide an atlas for extensive anatomy concepts. In this example, atlas segmentation is marked with different colors. b Knowledge generated from UMLS and search engines encompasses a broad array of concept-definition pairs and extensive relationships. c By integrating all collected knowledge sources, a medical knowledge tree is constructed. All definitions are partially displayed for conciseness. Definition and relation denoted with * are derived from the search engine, otherwise from UMLS.

Unified Medical Language System (UMLS)46 is a knowledge source of biomedical vocabulary developed by the US National Library of Medicine47. It integrates a wide range of concepts from more than 60 families of biomedical vocabularies, each equipped with a concept unique identifier and definition. It also contains the relations among these concepts. Following48, we extract 229,435 biomedical terminologies and definitions, as well as 1,048,575 relationship triplets, composing a knowledge graph of these terminologies.

Although UMLS is widely acknowledged and adopted as a general medical knowledge corpus48,49,50,51, it lacks a fine-grained description of anatomy concepts critical for segmentation tasks. For example, for “liver”, the definition is “A large lobed glandular organ in the abdomen of vertebrates that is responsible for detoxification, metabolism, synthesis, and storage of various substances”, which erases the morphological features and focuses on functionality. Meanwhile, more comprehensive knowledge on human anatomy may be scattered across various authoritative websites online, e.g., Wikipedia, ScienceDirect, etc. To harvest such knowledge, we select 6502 anatomy concepts and prompt a search engine to retrieve and summarize definitions for them. We use the following prompt template:

Definition of xxx. Include the location, shape, appearance, structure, and spatial relations to other anatomical structures. No need to include functionality. End with ‘END’.

For illustration, the search engine referred to authority websites including Columbia Surgery, Hopkins Medicine, and summarized the definition for “liver” as: “A large organ found in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen, it stands as the largest gland within the human body, with a weight of about 1.5 kilograms. This structure exhibits a reddish-brown hue and is cone or wedge-shaped … …”. While constructing the knowledge graph, we also adopt GPT424 to extract 38,344 relations between anatomical structures in the generated information-dense definitions with the following prompt:

This is the description of xxx. Please help me find its relations with other anatomical structures in radiological images. Summarize them with the template: Relation: xxx (relational preposition), Anatomical structure: xxx (name of another anatomical structure). For example, “Relation: situated below, Anatomical structure: xxx”, “Relation: connected to (via xxx), Anatomical structure: xxx” … …

Segmentation datasets naturally provide visual features for anatomy concepts corresponding to or complementary to the textual description, such as the texture, spatial location, shape, and so on. Details on our collected segmentation datasets are described in Section “Segmentation dataset”. Here, we use them as a large-scale and diverse visual atlas library, and link the visual regions to corresponding concepts in the textual knowledge graph, bridging the knowledge between visual and language modality.

In summary, by mixing these data, we construct a multimodal medical knowledge tree. As demonstrated in Fig. 10c, the concepts (including both anatomical structures and lesions) are linked via the relations and further extended with their definitions, containing their characteristics. Additionally, some are further mapped to the visual atlas, demonstrating their visual features that may hardly be described purely by text. More examples on the curated knowledge dataset are shown in Supplementary Tables 34, 35, and 36.

Segmentation dataset

To train our segmentation model with the ability to handle segmentation tasks of different targets, across various modalities and anatomical regions, we collect and integrate 72 diverse publicly available medical segmentation datasets, totaling 22,186 scans including CT, MRI, and PET, and 302,033 segmentation annotations spanning 8 different regions of the human body: brain, head and neck, upper limb, thorax, abdomen, pelvis, and lower limb. The dataset is termed as SAT-DS. More details are present in Supplementary Tables 26 and 27. Note that, some public datasets are not mutually exclusive, e.g., KiTS23 and KiTS2112, we thus only collect the latest version, to avoid redundancy and potential data leakage in the train-test split.

Before mixing these datasets for training, two challenges remain: (i) the anatomical targets from each dataset must be integrated into a unified annotation system. The clinic demands beneath each dataset collection might be different, resulting in different annotation standards and granularity. Meanwhile, since most datasets are annotated for training specialist models like nnU-Net16, precise and consistent terminology or expression for anatomical targets is often ignored. Therefore, a unified label system is demanded to avoid potential contradictions when training on mixed datasets. (ii) Some critical image statistics, such as intensity distribution and voxel spacing vary from dataset to dataset, hindering the model from learning consistent image representations across datasets. In the following, we present details for dataset integration and pre-processing, and how we address the abovementioned challenges.

To ensure a unified annotation system, we take three procedures while integrating different datasets: (i) we manually check each anatomical target in each dataset and assign a medical term to it, which is guaranteed to be precise and unambiguous across datasets. For instance, the targets that require distinction between orientations, such as the left lung and right lung, are always identified according to the left and right of the human body. And the same anatomical targets from different datasets are named consistently. For example, the i-th lumbar vertebrae in both TotalSegmentator52 and MRSpineSeg11 are named with the format “lumbar vertebrae i (Li)”; (ii) we adjust the annotations to minimize contradictions between overlapped classes. For example, considering that many organ segmentation datasets do not exclude lesions within organs, e.g., AbdomenCT-1K and CT-ORG, we merged the lesion annotations with the corresponding infected organ annotations in other datasets to maintain consistency. (iii) the same anatomy may have been annotated with different hierarchies in different datasets. In such cases, we manually merge the fine-grained classes to generate additional classes as a complement to close the gap between datasets. For example, sub-regions of the liver in Couinaud Liver53 are merged and added as a new class “liver”. As we will keep collecting datasets to scale up SAT-DS, such a label system will be maintained and updated continuously.

As properties of each dataset may greatly impact the training of the segmentation network16, such as intensity distribution and voxel spacing, we deliberately apply some normalization procedures to all the datasets to ensure uniformity and compatibility between them. Firstly, all the images are reoriented to specific axcodes, respaced to a voxel size of 1 × 1 × 3 mm2 and cropped to the non-zero region. Secondly, we apply different intensity normalization strategies to CT, MRI, and PET images. Specifically, for CT images, intensity values are truncated to [−500, 1000] and applied z-score normalization. For MRI and PET images, intensity values are clipped by 0.5% and 99.5% of the image, and then z-score normalized. During training, we randomly crop the image patch with a fixed size of 288 × 288 × 96. Random zoom-in, zoom-out, and intensity scaling are applied for data augmentation.

After integrating datasets, we derive a segmentation data collection that covers 497 segmentation classes, far outpacing each single dataset in both diversity and scale. Specifically, the data collection is more than fourth times the size of the largest dataset (BraTS2023-GLI) in terms of volume number, and nearly triple the most comprehensive dataset (DAP Atlas) in terms of the class number. We divide the human body into eight regions and classify each class into them manually. Figure 11b, c shows the distribution of classes and annotations across different human body regions. We further show the distribution of some example classes in each region in Fig. 11a. The extensive range of categories and regions lays the foundation for the SAT’s wide application scenarios.

a Annotation num of some representative classes in each anatomical region; b Number of classes in each anatomical region; c Number of annotations in each anatomical region. LC/HC laryngeal/hypopharyngeal cancer, WHM white matter hyperintensities, PV & SV portal vein and splenic vein, IVC inferior vena cava, Thoracic V thoracic vertebrae, Cervical V cervical vertebrae, Lumbar V lumbar vertebrae.

In the process of building SAT-DS, we merge a wide range of segmentation tasks and establish a unified label system by using natural language/text. Generally speaking, there are three advantages to doing this: (i) natural language is powerful and discriminative, which enables better differentiation of the medical terminologies in the language embedding space; (ii) as shown in previous work48,49,50,51, knowledge-enhanced representation learning for the text encoder demonstrates promising performance, allowing to learn the implicit or explicit relationships between these segmentation targets. For example, segmenting a specific lobe of the liver requires the exact segmentation of the liver as an organ in the abdominal cavity, and shall be facilitated by referring to other parts of the liver. Therefore, establishing such connections via systematic medical knowledge shall be beneficial. (iii) Text prompts can be given automatically without any human intervention, for instance, from large language models. This would pave the way for building a segmentation model that can be flexibly integrated into foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence, as a powerful grounding tool.

Large-vocabulary segmentation prompted by text

Assuming we have a segmentation dataset collection, i.e., \({\mathcal{D}}=\{({x}_{1},{y}_{1};{T}_{1}),\ldots ,({x}_{K},{y}_{K};{T}_{K})\}\), where \({x}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{H\times W\times D\times C}\) denotes the image scan, \({y}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{H\times W\times D\times M}\) is the binary segmentation annotations of the anatomical targets in the image and Ti = {t1, t2, …, tM} denotes the corresponding medical terminology set, the segmentation task can be formulated as:

where Φvisual is a visual encoder, Φtext is a text encoder, ΦSAT is a large-vocabulary segmentation foundation model. Ideally, xi can be an image scan from any modality and anatomical region, and Ti can contain an arbitrary number of text-based medical terminologies of interest.

To build such a model, we consider two main stages, namely, multimodal knowledge injection and segmentation training. In the following, we firstly show how to structure multimodal medical knowledge and inject it into a text encoder (Section “Multimodal knowledge injection”). Then, we employ the text encoder to guide our segmentation model training on SAT-DS dataset (Section “Segmentation training”). In addition, we provide more details about the model architecture and training strategies in the “Technical details” Section in the Supplementary.

Multimodal knowledge injection

Here, we aim to inject rich multimodal medical knowledge into the visual and text encoders. The section starts from the procedure for structuring the multimodal medical knowledge data and further presents details to use them for visual-language pre-training.

As shown in Fig. 12a, the data from UMLS, search engine, and segmentation datasets can be aggregated into two formats:

-

Textual medical concept pair. For text-only knowledge, each concept ti is associated with a definition pi, constructing pairs of text (ti; pi). We also derive a knowledge graph that connects the medical concepts through abundant triplet relationships (ti, rij, tj). This graph can be alternatively seen as a specialized text pair, (ti + rij; tj) or (ti; rij + tj), where “+” refers to string concatenation. In this way, we can thus unify the two kinds of textual knowledge.

-

Visual medical concept pair. To align with the segmentation task, we gather pairs consisting of a concept (can be either an anatomical structure or lesion) and its image atlas. Note that, multiple pairs could be extracted from a single image. These pairs share a similar format to the segmentation data, denoted as (xi, yi; ti), where xi and ti are consistent with their definition in Section 4.3 and \({y}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{H\times W\times D\times 1}\) is a binary segmentation mask for ti.

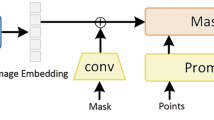

a We inject multimodal medical knowledge into knowledge encoders via contrastive learning. The knowledge is in different formats: atlas segmentation, concepts(terminologies), definitions, and relationships between concepts. We devise visual and text encoders to embed them; b We train a segmentation network based on the text prompts from the pre-trained text encoder. It is capable of segmenting a wide range of targets for image scans from different modalities and anatomical regions.

In summary, all the knowledge can either be represented as pure text description, e.g., ti, pi, ti + rij, rij + tj, or atlas segmentation (xi, yi), and paired further.

As shown in Fig. 12a, for pure text description, we encode them with a BERT54 pre-trained on PubMed abstracts55:

where d refers to the feature dimension. For visual concepts, we adopt the visual encoder Φvisual. Given the excellent robustness and performance of U-Net16,18, we apply a standard 3D U-Net encoder to extract multi-scale image embeddings:

where Vi is the multi-scale feature maps from U-Net encoder layers, and Hs, Ws, Ds, ds are the spatial resolutions and channel width at different layers. We further average ROI pooling on these feature maps, respectively, based on the down-sampled segmentation mask fitting resolutions at different layers. The concatenated pooled features can thus be treated as a representation of the anatomical target on this image, containing multi-scale visual clues for it.

We train the visual encoder and text encoder by maximizing the similarities between all positive knowledge pairs, linked by text prompts (medical terminology names), as shown in Fig. 12a. Specifically, given (xi, yi; ti), (ti; pi), (ti + rij; tj), (ti; rij + tj), for simplicity, we denote all the encoded features as z, regardless of their modality format. For a batch of N pairs \(\{({z}_{1},z^{\prime} ),\ldots ({z}_{N},z^{\prime} )\}\), we have:

with τ = 0.07 as temperature.

On formulation, this procedure resembles a typical contrastive learning pipeline56,57,58. However, different from previous work that directly contrasts the paired visual-language data, we aim for knowledge-enhanced representation learning. By maximizing the similarities between the constructed positive textual and visual feature pairs, we force the text encoders to construct neural representations for medical concepts based on domain knowledge from two aspects: (i) through the well-established knowledge graph in text form, the text encoder enables encoding relationships between concepts in the latent space; (ii) the model captures the characteristics of anatomical structures and lesions via both visual atlas segmentations and detailed definitions. Therefore, in contrast to the one-hot labeling that treats each anatomical target as being independent, such continuous neural representation shall provide more helpful guidance for the segmentation task.

Segmentation Training

With the pre-trained visual and text encoder, we now continue the procedure for building the segmentation model with text as prompts. Figure 12b demonstrates the overall framework. Specifically, apart from the pre-trained visual and text encoders, the segmentation model consists of three more components: a visual decoder Φdec, a query decoder Φquery, and a mask generator. Although a sample in the segmentation dataset collection (xi, yi; Ti) may contain multiple annotations, i.e., Ti = {t1, t2, …, tM}, for simplicity, we first describe the segmentation procedure for one target ti in the following.

Given an anatomical terminology ti, we employ the pre-trained text encoder to generate its neural embedding, which serves as the text prompt for segmentation:

Note that, after pre-training the text encoder with domain knowledge injection, zi should contain both the textual background information and visual information from atlas samples.

For image scan yi, we first adopt the pre-trained visual encoder to derive the multi-scale image embeddings Vi, as explained in Equa. (3), and continue training it. Then, in the visual decoder, the feature maps from the encoder are gradually upsampled with skip connections, effectively following the U-Net architecture16,18, ending up with per-pixel dense features:

where \(d^{\prime}\) is the dimension for the per-pixel dense feature after recovering to the original resolution.

Although a general representation of the anatomical target is derived from the pre-trained text encoder with a text prompt, visual variations may still exist from patient to patient, we thus insert a transformer-based query decoder to further enhance the text prompts with visual clues. In practice, it consists of 6 standard transformer decoders59 that treat text embedding as query, and the pooled multi-scale visual features from the U-Net encoder as key, values, formulated as:

Where zi is consistent with z in Eq. (4). Therefore qi can be seen as an adapted representation of the anatomical target in a specific image scan xi.

Finally, by conducting a pixel-wise dot product between the representation of the anatomical target and the fine-grained per-pixel embedding, we can acquire a per-pixel prediction:

where g( ⋅ ) is a feed-forward layer projecting qi to a consistent dimension with the dense feature map ui, and σ( ⋅ ) denotes the sigmoid function. Note that the whole forward procedure does not involve any operation between different text prompts. Therefore, for input with multiple text prompts or segmentation targets, i.e., Ti = {t1, t2, …, tM}, the processes described in Eqs. (6), (8), and (9) will be executed for each target in parallel, and we could derive \({\hat{y}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{H\times W\times D\times M}\).

Following16, we adopt a loss function as the sum of binary cross-entropy loss and dice loss. For a sample with M classes and C voxels, we denote pc,m and sc,m as the prediction and ground truth for c-th pixel, respectively, on class m, the loss is:

Evaluation datasets

To strike a balance between extensive experiments and computational costs, we utilize two collections of datasets in evaluation:

-

SAT-DS. As described in Section “Segmentation dataset”, this contains all the 72 datasets, 497 classes from all human body regions, 22,186 image scans, and 302,033 segmentation annotations.

-

SAT-DS-Nano. A subset of SAT-DS, including only 49 datasets, 13,303 images, and 151,461 annotations. Note that SAT-DS-Nano also covers 429 classes from all human body regions, adequate to evaluate the large-vocabulary segmentation task.

The detailed composition of SAT-DS and SAT-DS-Nano can be found in Supplementary Tables 32 and 33. As there is no existing benchmark for evaluating the large-vocabulary segmentation foundation model, we randomly split each dataset into 80% for training and 20% for testing: (i) datasets may share the same images but with different classes. For example, Couinaud Liver provides fine-grained liver segmentation on a subset of MSD Hepatic Vessel. We carefully split the Couinaud Liver to make sure the test set will not be leaked in the train set of MSD Hepatic Vessel; (ii) scans of the same patient but different modalities are treated as different samples during training and evaluation. For example, MSD Prostate contains T2 and ADC scans of each patient. However, they share the same structure on the image. To avoid potential data leaking, we carefully split such datasets by patient ID. Note that when involving segmentation datasets in the visual-language pretraining, we only use the training data to avoid potential data leaking. For datasets involved in SAT-DS-Nano, we keep their splits the same as in SAT-DS. The download link for each dataset can be found in Section 6, and we have released our dataset processing code and train-test splits to the research community for reproduction and benchmarking.

Baselines

We take nnU-Net16, U-Mamba14, and SwinUNETR19 as representative types of specialist model and strong baselines for comparison. For a comprehensive evaluation, we train one specialist model on each of the datasets. Note that, following52, we split Totalsegmentator into 6 subsets and treat them as different datasets. Similarly, datasets such as CHAOS with both MRI and CT images are treated as two different datasets. When training specialist models on each dataset, we adopt a multi-class segmentation setting and deliver the masks of all categories in this dataset at once. We derive the optimal network architecture and pre-processing pipeline with the default setting of each specialist model. We present the detailed network design of nnU-Nets in Supplementary Table 26 and Table 27 for a straightforward comparison. In summary, we train an ensemble of 72 models for each type of specialist model, that are customized on each dataset. We adopt the latest official implementation of nnU-Net v2 and U-Mamba in practice. The SwinUNETR is adopted to the same auto-configuration framework as U-Mamba.

We take MedSAM20 as a representative interactive segmentation model and competitive baseline. MedSAM finetunes SAM22 on 86 segmentation datasets, and supports 2D medical image segmentation with box prompts. We follow the official implementation to process and infer image slice by slice, and calculate the metrics on the finally stacked 3D prediction. For each single target on a slice, to simulate box prompts towards it, we both take the minimum rectangle containing the ground truth segmentation (Tight), and follow the official data augmentation procedure, randomly shift each corner up to 8% of the whole image resolution (Loose). In addition, we consider directly using the tight box prompts as predictions (Oracle Box).

We take BiomedParse23, a concurrent text-prompted segmentation model for 2D biomedical images, as a baseline. We follow the official implementation for data processing, inference, and post-filtering. Similar to MedSAM, we process and infer image slice by slice, and calculate the metrics on the finally stacked 3D prediction. As BiomedParse may fail to detect the target on the slice, we evaluate it under two settings: only prompt target present in the current slice (Oracle) and prompt all the targets available in the dataset and post-filter out potential false positive predictions by p-values.

Evaluation protocols

Given our goal is to develop a large-vocabulary medical segmentation foundation model, this provides opportunities to evaluate novel perspectives in addition to the traditional evaluation per dataset. Specifically, we conduct the internal evaluations from three dimensions:

-

Class-wise evaluation. As SAT is capable of segmenting a wide range of anatomical targets across the human body, we merge the results from the same classes across datasets to indicate the performance on each anatomical target. Specifically, we follow macro-average method: for a class annotated in multiple datasets, we first calculate its average scores within each dataset, and then average them over all datasets. Note that the same anatomical structures or lesions from different modalities are treated as different classes in this work, e.g., liver in both CT and MRI images.

-

Region-wise evaluation. In general, anatomical structures from the same human body region are closely connected and more likely to be involved in diagnosis within the same hospital department. Here, we consider the region-wise evaluation: based on class-wise evaluation, we merge results from all classes in the same body region, as to indicate the general performance in this region. For classes existing in multiple regions, we classify them into “Whole Body” category. In addition, we report results for lesions classes independently as a category “lesion”, instead of merging them into specific regions.

-

Dataset-wise evaluation. Results of the classes within the same dataset are averaged to indicate the performance on this dataset. This is the same as the conventional evaluation protocol of specialist segmentation models trained on a single dataset.

Evaluation metrics

We quantitatively evaluate the segmentation performance from the perspective of region and boundary metrics60, e.g., DSC and NSD, respectively.

DSC is a standard region-based metric for medical image segmentation evaluation. It measures the overlap between the model’s prediction P and ground truth G, formally defined as:

NSD61 is a boundary-based metric that measures the consistency at the boundary area of the model’s prediction P and ground truth G, which is defined as:

where \({B}_{\partial P}=\{x\in {{\bf{R}}}^{3}| \exists \hat{x}\in \partial P,| | x-\hat{x}| | \le \tau \}\) and \({B}_{\partial G}=\{x\in {{\bf{R}}}^{3}| \exists \hat{x}\in \partial G,| | x-\hat{x}| | \le \tau \}\) are the boundary areas of the model’s prediction and ground truth at a tolerance τ, respectively. We set τ as 1 in the experiments.

Data availability

The access to each dataset can be found in Table 1. The data process code to buildSAT-DS and our train-test splits for reproducibility and benchmarking are available at https://github.com/zhaoziheng/SAT-DS.

Code availability

The code is available at https://github.com/zhaoziheng/SAT.

References

Wang, Y., Zhao, L., Wang, M. & Song, Z. Organ at risk segmentation in head and neck CT images using a two-stage segmentation framework based on 3d U-Net. IEEE Access 7, 144591–144602 (2019).

Yan, K., Wang, X., Lu, L. & Summers, R. M. Deeplesion: automated mining of large-scale lesion annotations and universal lesion detection with deep learning. J. Med. Imaging 5, 036501–036501 (2018).

Baid, U. et al. The RSNA-ASNR-MICCAI Brats 2021 benchmark on brain tumor segmentation and radiogenomic classification. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2107.02314 (2021).

Nouranian, S. et al. Learning-based multi-label segmentation of transrectal ultrasound images for prostate brachytherapy. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 35, 921–932 (2015).

Jaffray, D. A., Knaul, F., Baumann, M. & Gospodarowicz, M. Harnessing progress in radiotherapy for global cancer control. Nat. Cancer 4, 1228–1238 (2023).

Nauffal, V. et al. Noninvasive assessment of organ-specific and shared pathways in multi-organ fibrosis using T1 mapping. Nat. Med. 30, 1749–1760 (2024).

Bai, W. et al. A population-based phenome-wide association study of cardiac and aortic structure and function. Nat. Med. 26, 1654–1662 (2020).

Ma, J. et al. Abdomenct-1k: is abdominal organ segmentation a solved problem? IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Machine Intell. 44, 6695–6714 (2021).

Ma, J. et al. Unleashing the strengths of unlabelled data in deep learning-assisted pan-cancer abdominal organ quantification: the flare22 challenge. Lancet Digit. Health 6, e815–e826 (2024).

Antonelli, M. et al. The medical segmentation decathlon. Nat. Commun. 13, 4128 (2022).

Pang, S. et al. Spineparsenet: spine parsing for volumetric MR image by a two-stage segmentation framework with semantic image representation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 40, 262–273 (2020).

Heller, N. et al. The kits21 challenge: automatic segmentation of kidneys, renal tumors, and renal cysts in corticomedullary-phase CT. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.01984 (2023).

Ma, J. et al. Toward data-efficient learning: a benchmark for COVID-19 CT lung and infection segmentation. Med. Phys. 48, 1197–1210 (2021).

Ma, J., Li, F. & Wang, B. U-mamba: enhancing long-range dependency for biomedical image segmentation. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.04722 (2024).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. UNETR: transformers for 3D medical image segmentation. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision 574–584 (IEEE, 2022).

Isensee, F., Jaeger, P. F., Kohl, S. A., Petersen, J. & Maier-Hein, K. H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 18, 203–211 (2021).

Milletari, F., Navab, N. & Ahmadi, S.-A. V-net: fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV) 565–571 (IEEE, 2016).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. Swin UNETR: swin transformers for semantic segmentation of brain tumors in MRI images. In International MICCAI Brainlesion Workshop, 272–284 (Springer, 2021).

Ma, J. et al. Segment anything in medical images. Nat. Commun. 15, 654 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Segment anything model for medical images? Med. Image Anal. 92, 103061 (2024).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 4015–4026 (IEEE, 2023).

Zhao, T. et al. A foundation model for joint segmentation, detection and recognition of biomedical objects across nine modalities. Nat. Methods 22, 166–176 (2024).

Achiam, J. et al. GPT-4 Technical Report. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774 (2023).

Qu, C. et al. Abdomenatlas-8k: annotating 8,000 CT volumes for multi-organ segmentation in three weeks. In Proc. 37th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2023) Track on Datasets and Benchmarks (NIPS, 2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Merit: multi-view evidential learning for reliable and interpretable liver fibrosis staging. Med. Image Anal. 102, 103507 (2024).

Dou, Q. et al. 3D deeply supervised network for automated segmentation of volumetric medical images. Med. Image Anal. 41, 40–54 (2017).

Li, X. et al. H-denseunet: hybrid densely connected UNET for liver and tumor segmentation from CT volumes. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 37, 2663–2674 (2018).

Yu, Q. et al. Recurrent saliency transformation network: incorporating multi-stage visual cues for small organ segmentation. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 8280–8289 (IEEE, 2018).

Zhou, Z., Siddiquee, M. M. R., Tajbakhsh, N. & Liang, J. UNet++: redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 1856–1867 (2019).

Schlemper, J. et al. Attention gated networks: learning to leverage salient regions in medical images. Med. Image Anal. 53, 197–207 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Decoupled pyramid correlation network for liver tumor segmentation from CT images. Med. Phys. 49, 7207–7221 (2022).

Cao, H. et al. Swin-Unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In European Conference on Computer Vision 205–218 (Springer, 2022).

Xie, Y., Zhang, J., Shen, C. & Xia, Y. CoTr: efficiently bridging CNN and transformer for 3D medical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) 171–180 (Springer, 2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. mmformer: Multimodal medical transformer for incomplete multimodal learning of brain tumor segmentation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) 107–117 (Springer, 2022).

Chen, J. et al. TransUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture design for medical image segmentation through the lens of transformers. Med. Image Anal. 97, 103280 (2024).

Zhou, H.-Y. et al. nnformer: volumetric medical image segmentation via a 3d transformer. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing (IEEE, 2023).

Wang, H. et al. Sam-med3d: Towards general-purpose segmentation models for volumetric medical images. In European Conference on Computer Vision 51–67 (Springer, 2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Radgenome-chest CT: a grounded vision-language dataset for chest CT analysis. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.16754 (2024).

Xie, Y. et al. MedTrinity-25M: A large-scale multimodal dataset with multigranular annotations for medicine. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2025).

Xu, J. et al. Learning open-vocabulary semantic segmentation models from natural language supervision. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2935–2944 (IEEE, 2023).

Wang, H. et al. Ov-vis: open-vocabulary video instance segmentation. Int. J. Computer Vis. 132, 5048–5065 (2024).

Lai, X. et al. Lisa: Reasoning segmentation via large language model. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 9579–9589 (IEEE, 2024).

Yan, C. et al. Visa: Reasoning video object segmentation via large language models. In European Conference on Computer Vision 98–115 (Springer, 2024).

Li, H. et al. Lorkd: low-rank knowledge decomposition for medical foundation models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.17184 (2024).

Bodenreider, O. The unified medical language system (UMLS): integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D267–D270 (2004).

National Library of Medicine. National library of medicine—national institutes of health. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/.

Zhang, X., Wu, C., Zhang, Y., Xie, W. & Wang, Y. Knowledge-enhanced visual-language pre-training on chest radiology images. Nat. Commun. 14, 4542 (2023).

Wu, C., Zhang, X., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y. & Xie, W. Medklip: medical knowledge enhanced language-image pre-training for x-ray diagnosis. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 21372–21383 (IEEE, 2023).

Lei, J. et al. Unibrain: universal brain MRI diagnosis with hierarchical knowledge-enhanced pre-training. Computerized Med. Imaging Graph. 102516 (2025). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895611125000254.

Zheng, Q. et al. Large-scale long-tailed disease diagnosis on radiology images. Nat. Commun. 15, 10147 (2024).

Wasserthal, J. et al. Totalsegmentator: robust segmentation of 104 anatomic structures in CT images. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 5, e230024 (2023).

Tian, J., Liu, L., Shi, Z. & Xu, F. Automatic couinaud segmentation from CT volumes on liver using GLC-UNET. In International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging 274–282 (Springer, 2019).

Kenton, J. D. M.-W. C. & Toutanova, L. K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NACCL-HLT) 4171–4186 (2019).

Lee, J. et al. Biobert: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 36, 1234–1240 (2020).

Radford, A. et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International conference on machine learning 8748–8763 (PMLR, 2021).

Lin, W. et al. PMC-CLIP: contrastive language-image pre-training using biomedical documents. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 525–536 (Springer, 2023).

Zhang, S. et al. A multimodal biomedical foundation model trained from fifteen million image–text pairs. NEJM AI 2, AIoa2400640 (2024).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (2017).

Maier-Hein, L. et al. Metrics reloaded: recommendations for image analysis validation. Nat. Methods 21, 195–212 (2024).

Nikolov, S. et al. Clinically applicable segmentation of head and neck anatomy for radiotherapy: deep learning algorithm development and validation study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e26151 (2021).

Bernard, O. et al. Deep learning techniques for automatic MRI cardiac multi-structures segmentation and diagnosis: is the problem solved? IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 37, 2514–2525 (2018).

Ji, Y. et al. Amos: a large-scale abdominal multi-organ benchmark for versatile medical image segmentation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process.Systems 35, 36722–36732 (2022).

Liew, S.-L. et al. A large, curated, open-source stroke neuroimaging dataset to improve lesion segmentation algorithms. Sci. Data 9, 320 (2022).

Quinton, F. et al. A tumour and liver automatic segmentation (atlas) dataset on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for hepatocellular carcinoma. Data 8, 79 (2023).

Gatidis, S. et al. A whole-body FDG-PET/CT dataset with manually annotated tumor lesions. Sci. Data 9, 601 (2022).

Serag, A. et al. Construction of a consistent high-definition spatio-temporal atlas of the developing brain using adaptive kernel regression. Neuroimage 59, 2255–2265 (2012).

Avital, I. et al. Neural segmentation of seeding ROIs (sROIS) for pre-surgical brain tractography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 1655–1667 (2019).

Menze, B. H. et al. The multimodal brain tumor image segmentation benchmark (BraTS). IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 34, 1993–2024 (2014).

LaBella, D. et al. The ASNR-MICCAI brain tumor segmentation (BraTS) challenge 2023: intracranial meningioma. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv:2305.07642 (2023).

Moawad, A. W. et al. The brain tumor segmentation (BraTS-METS) challenge 2023: brain metastasis segmentation on pre-treatment MRI. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.00838 (2023).

Kazerooni, A. F. et al. The brain tumor segmentation (BraTS) challenge 2023: focus on pediatrics (CBTN-CONNECT-DIPGR-ASNR-MICCAI BraTS-PEDs). Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.15009 (2023).

Adewole, M. et al. The brain tumor segmentation (BraTS) challenge 2023: glioma segmentation in sub-Saharan Africa patient population (BraTS-Africa). Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.19369 (2023).

Landman, B. et al. Miccai multi-atlas labeling beyond the cranial vault–workshop and challenge. In Proc. MICCAI Multi-Atlas Labeling Beyond Cranial Vault-Workshop Challenge Vol. 5, 12 (2015).

Kavur, A. E. et al. Chaos challenge-combined (CT-MR) healthy abdominal organ segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 69, 101950 (2021).

Wang, K. et al. Extreme cardiac MRI analysis under respiratory motion: Results of the CMRxMotion Challenge. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.19165 (2025).

Dorent, R. et al. Crossmoda 2021 challenge: benchmark of cross-modality domain adaptation techniques for vestibular schwannoma and cochlea segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 83, 102628 (2023).

Rister, B., Yi, D., Shivakumar, K., Nobashi, T. & Rubin, D. L. CT-org, a new dataset for multiple organ segmentation in computed tomography. Sci. Data 7, 381 (2020).

Liu, P. et al. Deep learning to segment pelvic bones: large-scale CT datasets and baseline models. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 16, 749 (2021).

Jaus, A. et al. Towards unifying anatomy segmentation: Automated generation of a full-body ct dataset. In IEEE International Conference on Image Processing 41–47 (IEEE, 2024).

Payette, K. et al. An automatic multi-tissue human fetal brain segmentation benchmark using the fetal tissue annotation dataset. Sci. Data 8, 167 (2021).

Masoudi, M. et al. A new dataset of computed-tomography angiography images for computer-aided detection of pulmonary embolism. Sci. Data 5, 180180 (2018).

Podobnik, G., Strojan, P., Peterlin, P., Ibragimov, B. & Vrtovec, T. Han-seg: the head and neck organ-at-risk CT and MR segmentation dataset. Med. Phys. 50, 1917–1927 (2023).

Andrearczyk, V., Oreiller, V., Hatt, M. & Depeursinge, A. Overview of the hecktor challenge at MICCAI 2022: Automatic head and neck tumor segmentation and outcome prediction in PET/CT. In Andrearczyk, V., Oreiller, V., Hatt, M. & Depeursinge, A. (eds.) Head and Neck Tumor Segmentation and Outcome Prediction. HECKTOR 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Vol. 13626 (Springer, 2023).

Li, X. et al. The state-of-the-art 3d anisotropic intracranial hemorrhage segmentation on non-contrast head CT: the instance challenge. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.03281 (2023).

Hernandez Petzsche, M. R. et al. Isles 2022: a multi-center magnetic resonance imaging stroke lesion segmentation dataset. Sci. Data 9, 762 (2022).

He, Y. et al. Meta grayscale adaptive network for 3D integrated renal structures segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 71, 102055 (2021).

Li, L., Zimmer, V. A., Schnabel, J. A. & Zhuang, X. Atrialjsqnet: a new framework for joint segmentation and quantification of left atrium and scars incorporating spatial and shape information. Med. Image Anal. 76, 102303 (2022).

Pedrosa, J. et al. Lndb challenge on automatic lung cancer patient management. Med. Image Anal. 70, 102027 (2021).

Setio, A. A. A. et al. Validation, comparison, and combination of algorithms for automatic detection of pulmonary nodules in computed tomography images: the luna16 challenge. Med. Image Anal. 42, 1–13 (2017).

Zhuang, X. & Shen, J. Multi-scale patch and multi-modality atlases for whole heart segmentation of MRI. Med. Image Anal. 31, 77–87 (2016).

Qiu, J. et al. Myops-net: myocardial pathology segmentation with flexible combination of multi-sequence CMR images. Med. Image Anal. 84, 102694 (2023).

Bakr, S. et al. A radiogenomic dataset of non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Data 5, 1–9 (2018).